Abstract

It is generally believed that there is an instrumental relationship between problem gambling and crime such that some gamblers resort to illegal activity to recoup financial shortfalls resulting from their gambling. However, a clear understanding of the risk factors for the commission of crimes beyond financial stresses is absent in the literature. The aim of this review was to identify the nature of crimes perpetrated by problem gamblers and the factors that contribute to the commission of gambling-related crimes. A systematic review adhering to guidelines outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement searching eight databases—PsycINFO, Westlaw AU, Heinonline, Legal Source via Ebsco, Legaltrac via Gale, PubMed, Scopus, and Medline—was conducted. A total of 21 papers were included after screening and application of exclusion criteria. All studies examined reported crimes committed by problem gamblers, with a validated assessment tool measuring problem gambling. The review provided evidence that gambling-related crime typically consists of non-violent, income-generating offences. However, it also revealed that problem gamblers may commit violent crimes at a higher than expected rate, which may have been concealed by deliberate and unintentional under-reporting of gambling-related crimes. The causal relationship between problem gambling and violent crime, however, remains uncertain. Based on this review, suggestions are offered for the evaluation of perpetrators of gambling-related crime on a case-by-case basis, to better understand the relationship between gambling and crime and facilitate more frequent application of therapeutic jurisprudence in future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gambling disorders are classified as non-substance behavioural addictions in the Substance Related and Addictive Disorders category of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association 2013). The condition is characterised by repeated patterns of excessive gambling expenditure resulting in significant adverse consequences and impaired personal, familial, financial, and employment/study functioning, and social and legal costs (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Clinical and epidemiological studies have consistently reported elevated rates of affective disorders, suicidality, marital and familial discord, domestic violence, substance use, bankruptcy and the commission of criminal offences among individuals meeting diagnostic criteria or scores on screening instruments (see Hartmann and Blaszczynski 2016). In Australia, over $18 billion are spent annually on gambling (i.e., $1500 per capita). This represents a markedly higher expenditure than other comparable countries such as New Zealand ($495 per capita), Canada ($393 per capita), and the United States ($325 per capita; Delfabbro 2010). The social cost of this gambling—including suicide, depression, breakdown of interpersonal relationships, reduced productivity, unemployment, bankruptcy and crime—totals approximately $4.7 billion per year in Australia (Productivity Commission 2010).

Given the configuration of commercial gambling products conferring a statistical advantage to the operator, individuals are invariably exposed to experiencing persistent losses over progressive sessions of gambling. As a consequence, despite occasional wins, losses tend to accumulate and create escalating levels of debt. Irrespective of an individual’s income or financial position (Sakurai and Smith 2003), motivation to chase losses (Lesieur 1984) results in relative increases in bet sizes and the emergence of severe financial stresses (Turner et al. 2017). Once access to legitimate sources of funds are exhausted and debts exceed their capacity for repayment, a proportion of individuals perceive theft or fraud as the only viable option to maintain their habitual behaviour, and gain a significant win that could extricate them from their financial crisis (Lesieur 1984; Blaszczynski et al. 1989; Sakurai and Smith 2003; Turner et al. 2009).

Criminal Offences and Gambling Disorders

Numerous studies have demonstrated a functional relationship between crime and gambling disorders (Blaszczynski and McConaghy 1994a; Meyer and Stadler 1999; Perrone et al. 2013). Desire to obtain funds to gamble directly motivates a proportion of crimes. Needing to meet shortfalls in available funds due to necessary financial obligations is another motivator of gambling-related crime (Blaszczynski and McConaghy 1994a). In both cases, such actions represent attempts to recoup losses from persistent gambling, and/or avoid detection of debts by significant others (Blaszczynski and McConaghy 1994a).

Perrone et al. (2013) posited that the relationship between gambling disorders and crime could be characterised in one of three ways. The link may be coincidental (i.e., there is no systematic link between gambling and criminal offending), co-symptomatic (i.e., a common underlying factor accounts for both offending and gambling) or instrumental (i.e., there is a causal connection between gambling and crime). The current body of literature investigating this relationship suggests that it is most likely instrumental, even if the exact causal factors and pathways remain uncertain.

Given the motivation, offences are typically non-violent and include but are not limited to fraud, theft, embezzlement, breaking and entering, larceny, and selling drugs (Abbott and McKenna 2005; Abbott et al. 2005; Monash University Centre for Criminology and Criminal Justice 2000; Productivity Commission 1999; Turner et al. 2009). In contrast, violent crimes such as burglary or armed robbery do occur but are generally infrequently reported in the literature (Blaszczynski and McConaghy 1994b; Abbott and Volberg 1999).

Prevalence Rates of Gambling-Related Crimes

The prevalence of gambling-related crimes is difficult to determine with any degree of accuracy. Rates are subject to differences in criteria used to define a crime and the sample investigated; clinical, general population, prison samples, and the data extracted; self-report or police/court records. Reported prevalence rates can be argued to be conservative given the likelihood that many offences fail to be considered as illegal (such as unauthorised withdrawal of funds from joint accounts), remain undetected, are committed against family members reluctant to instigate charges, or against employees electing not to proceed with charges following restitution of losses (Sakurai and Smith 2003). Nevertheless, elevated rates of offences have been consistently reported across clinical and prison populations.

Blaszczynski and McConaghy (1994b) examined the occurrence of criminal offences in pathological gamblers attending hospital-based treatment and Gamblers Anonymous. Across both treatment modes, 59% of subjects reported committing at least one gambling-related offence against property, with 23% reporting a conviction for such an offence. Meyer and Stadler (1999) reported similar rates in gamblers attending inpatient and outpatient treatment facilities. In their study, 89.3% of treatment seekers reported having committed a gambling-related offence in their lifetime, compared to 51.8% of high and low frequency gamblers from the general population and army samples. Folino and Abait (2009) conducted a similar study with callers to gambling helplines in Argentina and found that 32% admitted to engaging in illegal activity due to gambling. This number rose to 76% among anonymous gamblers in the same study (Folino and Abait 2009).

Gambling Disorders in Prison Inmates

If there is a direct or indirect causal relationship between crime and gambling, then it is reasonable to argue that a higher prevalence rate for gambling-related crimes should be evident within a prison population. Survey studies have estimated that the prevalence of problem and pathological gambling is higher by a magnitude of up to 20 times among prison inmates compared to the general population rates of 0.2–2.5% (Perrone et al. 2013; Turner et al. 2017; Productivity Commission 1999). These figures vary considerably depending on methodologies and measurements used. May-Chahal et al. (2017) examined gambling among prisoners in the UK and found a rate of 12.1% meeting criteria for a gambling disorder, a rate significantly greater than that of 0.7% for the general population. A similar rate of 6.4–13% (depending on the scale used) has been found among a sample of 254 Canadian male offenders (Preston et al. 2012).

Templer et al. (1993) study found 23% of 136 consecutively admitted Nevada medium-security prison inmates to be problematic gamblers, and a further 26% to be probable pathological gamblers. Williams et al. (2005) review of gambling in prison populations in Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States similarly found that the prevalence of problem gambling in both male and female inmates ranged from 17 to 60% on average. Turner et al. (2013) found that approximately a quarter of inmates from provincial and federal prisons in Ontario had a moderate or severe problem, with 9% specifically having a severe gambling problem. This is estimated to be approximately 10 times the rate of moderate and severe problem gambling in the general population (Williams et al. 2012).

Crime and Gambling in Prison Populations

Prison inmates meeting criteria for a gambling disorder exhibit comparably higher rates of criminal offences compared to clinical populations, ranging from 37 to 88% (Perrone et al. 2013; Riley and Oakes 2015) with a quarter of those attributing their incarceration to gambling related crimes. Turner et al. (2009) found a much higher rate of 65.2% of severe and 20% of moderate problem gambling Canadian inmates reporting that their criminal offences were a consequence of gambling (e.g., to pay off debts). Abbott and colleagues (Abbott et al. 2005; Abbott and McKenna 2005) investigated the prevalence of problem gambling in men and women’s prisons in New Zealand. Among 357 male prisoners, 21% were lifetime probable pathological gamblers, and 16% were probable ‘current’ (past 6 months from incarceration) pathological gamblers. Of the ‘current’ sample, 51% admitted to previous gambling related offending, and 35% indicated these crimes contributed to their incarceration (Abbott et al. 2005).

Taken together, the extant body of literature suggests that the relationship between problem gambling and crime is unlikely to be coincidental, although the question of causality remains unclear. Absent in the literature is a clear understanding of the factors that represent risk factors for the commission of an offence beyond the presence of financial stresses. To advance knowledge in the field, it is relevant to identify the nature of crimes committed and factors that contribute to the commission of gambling-related crimes.

Current Review

This systematic review follows the checklist and flow diagram outlined in the PRISMA Statement (Moher et al. 2009). This review located and critically assessed studies examining the nature of gambling-related crime and comparing factors leading to commission of crimes by gamblers as opposed to non-gamblers.

Methodology

Initial Search

The original search was conducted from the 26th to the 29th of June 2017; eight databases were searched and yielded papers for review: PsycINFO, Westlaw AU, Heinonline, Legal Source via Ebsco, Legaltrac via Gale, PubMed, Scopus, and Medline. Kluwer Law Journals and Oxford Journals were excluded due to a lack of relevant articles. The search string input into each database was as follows: (gambl*) AND (crime OR offence OR incarcerated OR prison OR forensic OR sentencing OR courts OR judiciary).

For databases that generated a large number of results, not all sources were reviewed. For example, Heinonline yielded 93,112 sources. When results were organized by relevance, only one source was found within the first 300 articles. Within the following 200 sources, none were found. To ensure that the sources had been correctly ordered by relevance, the last 400 studies were reviewed, none of which were found to be relevant. The same procedure was performed for Legaltrac via Gale, where 4296 sources were displayed.

Selection Criteria

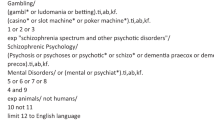

Inclusion criteria: Studies were included if they:

-

1.

Presented data on the type of reported crimes committed by problem gamblers where the gambler’s level of gambling behaviour is measured by a validated assessment tool.

-

2.

Analysed the factors contributing to the commission of non-violent crimes against property by gamblers, as compared to non-gamblers.

-

3.

Evaluated the nature of reported gambling-related crime.

Exclusion criteria: Studies were excluded if they:

-

1.

Were not available in English.

-

2.

Were not available in full text.

-

3.

Were published before 1990.

-

4.

Used data involving juvenile delinquents.

-

5.

Did not report the type or motive of the criminal offence committed.

Results

Study Selection

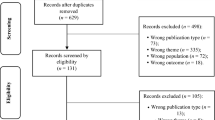

The initial search yielded over 100,000 references; however, only 128 were retained for review, based on their titles and abstracts (see Fig. 1). Of these 128, 31 were duplicates and therefore excluded. Two independent reviewers assessed the remaining 97 papers and applied inclusion and exclusion criteria. A total of 76 papers were subsequently excluded, leaving 21 included articles. Inter-rater reliability between the two reviewers was high, with initial agreement on 91.3% of papers. Information for the 21 reviewed articles is included in Table 1.

Study Characteristics

All studies reviewed examined reported crimes committed by problem gamblers, with a validated assessment tool measuring problem gambling. The analysis samples for these studies ranged from 94 to 18,625 participants. Nine studies examined problem gambling among incarcerated individuals (Abbott et al. 2005; Abbott and McKenna 2005; Tessényi and Kovács 2016; Lloyd et al. 2014; Templer et al. 1993; May-Chahal et al. 2017; Preston et al. 2012; Pastwa-Wojciechowska 2011; Turner et al. 2009) and a further eight sampled from individuals seeking treatment for problem gambling from various sources including Gamblers Anonymous and in- and out-patient facilities (Blaszczynski and McConaghy 1994a, b; Granero et al. 2014, 2015; Meyer and Stadler 1999; Martin et al. 2013; Rudd and Thomas 2016; Ledgerwood et al. 2007). Of the remaining studies, three used retrospective analysis of court files, police files and population surveys and statistics (or some combination; Crofts 2003; Kuoppamäki et al. 2014; Arthur et al. 2014), two sampled gamblers identified in larger cohort studies (Gorsane et al. 2017; Laursen et al. 2016), and one was a review of relevant studies in Spanish and English (Folino and Abait 2009).

Most of the studies (N = 15) assessed whether participants had previously committed a crime (gambling-related or otherwise; Abbott et al. 2005; Abbott and McKenna 2005; Blaszczynski and McConaghy 1994a; Ledgerwood et al. 2007; Granero et al. 2014, 2015; Meyer and Stadler 1999; Laursen et al. 2016; Preston et al. 2012; Rudd and Thomas 2016; Arthur et al. 2014; Martin et al. 2013; Pastwa-Wojciechowska 2011; Turner et al. 2009). Eleven studies collected data on other potential risk factors for crime and gambling such as family dysfunction, substance use and risk-taking behaviours (Abbott et al. 2005; Abbott and McKenna 2005; Tessényi and Kovács 2016; Lloyd et al. 2014; Meyer and Stadler 1999; May-Chahal et al. 2017; Preston et al. 2012; Rudd and Thomas 2016; Arthur et al. 2014; Martin et al. 2013; Pastwa-Wojciechowska 2011). Furthermore, five studies tested their sample for the presence of antisocial personality disorder (Blaszczynski and McConaghy 1994a; Ledgerwood et al. 2007; Meyer and Stadler 1999; Gorsane et al. 2017; Pastwa-Wojciechowska 2011).

General Limitations of the Gambling-Related Crime Literature

The literature on gambling-related crime is predicated upon the reporting of such crimes through self-report or retrospective analysis of recorded crimes. Both of these methodologies, however, bring with them respective advantages and disadvantages. While studies relying on self-disclosure of past illegal acts promote anonymity, there is no assurance that the gamblers disclose all crimes committed, gambling-related or otherwise. Failure to disclose gambling-related crime may occur because of discomfort admitting to offences, fear of being reported to authorities (particularly applicable for incarcerated participants) or failing to perceive their activities as criminal (Lesieur 1984; Bergh and Kühlhorn 1994). Where the focus of interviewing remains on offences motivated by obtaining money, participants might either fail to, or avoid, disclosing violent crimes for similar reasons. Therefore, reviewed studies relying on self-report may disguise a higher occurrence of violent gambling-related offences than the results indicate (Abbott et al. 2005; Abbott and McKenna 2005; Tessényi and Kovács 2016; Lloyd et al. 2014; Templer et al. 1993; May-Chahal et al. 2017; Preston et al. 2012; Pastwa-Wojciechowska 2011; Turner et al. 2009; Blaszczynski and McConaghy 1994a, b; Granero et al. 2014, 2015; Meyer and Stadler 1999; Martin et al. 2013; Rudd and Thomas 2016; Ledgerwood et al. 2007).

Studies have also found that problem gamblers who commit crimes such as embezzlement or theft to fund their gambling over an extended time tend to markedly underestimate the amount of money obtained (Crofts 2003). As such, the magnitude of fiscal crimes constituting the majority of reported crimes may potentially be underestimated in studies reliant on participants’ self-report.

A portion of the reviewed studies examined retrospective case files of gambling-related crime (Crofts 2003; Kuoppamäki et al. 2014; Arthur et al. 2014). A key benefit of this methodology is the ability to establish an objective record of crimes that a gambler has committed. However, as police and court records only consist of crimes that were reported, these cannot identify or account for crimes where the gambler escaped detection or charge. As it is possible for crimes to go unreported, even when detected (e.g., when committed against family members; Sakurai and Smith 2003; Crofts 2003), records do not capture the full scope of a problem gambler’s criminal activity. Further, the authors of these studies (Crofts 2003; Kuoppamäki et al. 2014; Arthur et al. 2014) noted that it could be difficult to delineate whether crimes are gambling-related or not based on case descriptions. The degree of detail in which the crime and its motivation is documented may be highly variable, and those with insufficient detail which cannot unambiguously establish that the crime was gambling-related must be omitted from analysis, even if the authors of these studies suspect crimes to be gambling-related. Conversely, crimes that are not judged as gambling-related based upon case files may in fact have their roots in gambling but are insufficiently described to make this judgment with confidence. In the case of Crofts’ (2003) analysis of NSW court files, some cases also involved defendants who claimed gambling addiction to mitigate their criminal responsibility. While this theoretically may increase the number of allegedly gambling-related crimes, Crofts (2003) posited that this is unlikely to impact the study’s results as in NSW gambling addiction is not currently considered grounds to reduce criminal responsibility and therefore the number of such cases should be minimal.

In contrast to these studies, Rudd and Thomas’ (2016) retrospective analysis of clinical cases at a substance abuse service was able to identify probable problem gamblers and criminal behaviours associated with these individuals. However, this study was unable to distinguish which of these crimes were specifically gambling-related. Furthermore, while Rudd and Thomas (2016) found that potential problem gamblers were more likely to commit offences for financial gain, consistent with the broader gambling literature (e.g., Blaszczynski and McConaghy 1994b), they also found that these individuals were highly prone to violent offending (e.g., robbery) as well as property and drug offences.

The Nature of Gambling-Related Crime

The literature reviewed confirms that gambling-related crimes are typically non-violent, income-producing offences. The magnitude of these crimes can vary greatly; across the reviewed studies, the mean amount of money stolen, embezzled, or obtained by other illegal means ranged from AU$40,000 to AU$78,000, although outliers skewed these means. However, the median value for illegally obtained funds across these studies was AU$3000–AU$13,500, indicating marked variability regardless of how it is indexed.

It would be an oversimplification to state that all studies found gambling-related crime to be income generating and non-violent. For example, Rudd and Thomas (2016) found that potential problem gamblers committed crimes for financial gain at a higher rate than non-problem gamblers; however, they also demonstrated elevated rates of violent crimes such as robbery. Similarly, Laursen et al. (2016) found that problem gamblers were significantly more likely than non-problem gamblers to be charged with both economic and violent crimes, and no more likely to be charged with one type than the other. Notably, in this study, violent crimes were not necessarily income-generating (Laursen et al. 2016). Additionally, Turner et al. (2009) found that severe problem gamblers were significantly more likely to have committed income-producing offences than moderate gamblers but were no more or less likely to have committed violent offences. Therefore, while it appears broadly true that problem gambling typically leads to non-violent offending, there remains a portion of the literature suggesting that more violent offences are possible, and arguably relatively common, among more severe problem gamblers.

Potential Causes of Gambling-Related Crime

The causal relationship between problem gambling and criminal activity remains a subject of debate in the current literature. Some studies (e.g., Martin et al. 2013; Blaszczynski and McConaghy 1994a, b; Pastwa-Wojciechowska 2011) have posited that problem gambling precedes criminality. Martin et al. (2013) found that gamblers in an addiction treatment program predominantly reported that gambling led to the commission of crimes for which they were convicted. However, Martin et al. (2013) were hesitant to draw conclusions about causality despite these self-reports due to the cross-sectional nature of the study. Blaszczynski and McConaghy’s (1994b) interviews with gamblers in hospital treatment and Gambler’s Anonymous revealed that offenders had been gambling longer than non-offenders, and there was a substantial time lag between the commencement of gambling and gambling-related offending, which they interpreted as evidence for a causal influence of gambling upon criminal activity. In contrast, interviews with male and female inmates in New Zealand (Abbott et al. 2005; Abbott and McKenna 2005) found that a sizeable proportion of each sample reported having committed gambling-related crime and having been incarcerated for such offences. However, most inmates interviewed were “criminals first, problem gamblers second”, as only a very small proportion of prisoners questioned reported that their early offending (prior to their current incarceration) was gambling-related.

Blaszczynski and McConaghy (1994a) proposed another pathway for the emergence of illegal behaviour in suggesting that antisocial personality characteristics and criminal behaviour may emerge from the pressure of mounting gambling debts and the need to conceal them. They found what while problem gamblers that met criteria for antisocial personality disorder were at an elevated risk of criminal offending, offending was independent of antisocial personality disorder for most. Similarly, Pastwa-Wojciechowska (2011) concluded that crime emerges from personal and financial problems precipitated by gambling.

Blaszczynski and McConaghy (1994a) and Pastwa-Wojciechowska (2011) assertion that antisocial personality disorder is independent of gambling-related offending is striking as other studies have suggested that antisocial personality and its associated impulsive behaviours may be an underlying contributor to the commission of these crimes (e.g., May-Chahal et al. 2017; Meyer and Stadler 1999). May-Chahal et al. (2017) found a longitudinal link between loss-chasing and high rates of criminal behaviour that is perhaps indicative of underlying difficulties with impulse control. Similarly, Meyer and Stadler (1999) proposed that addictive gambling behaviour and impulsive antisocial personality factors directly influence criminal activity. In contrast, Meyer and Stadler (1999) were tentative to draw firm conclusions and asserted that although the purported influence of gambling upon criminal activity is theoretically sound, the relationship could be accounted for by other factors such as substance use and other mental disorders. Consequently, they suggested that the validity of this relationship could only be confirmed by logical argument. Consideration of the longitudinal progression of gambling and criminal offending as demonstrated by various authors (e.g., Blaszczynski and McConaghy’s 1994b; Abbott and McKenna 2005; Abbott et al. 2005) could be taken as conferring a causal relationship between gambling and crime.

Several studies in the current review echoed Meyer and Stadler’s (1999) contention that a range of other factors may mediate the relationship between gambling and criminal offending. Gorsane et al. (2017) posited that substance use co-occurring with problem gambling might have a disinhibiting effect, thereby leading to illegal activity. Preston et al. (2012) supported Meyer and Stadler’s (1999) suggestion that other co-morbid mental disorders may mediate the gambling-crime relationship. Although their research was correlational and therefore did not draw any causal conclusions, they posited that social anxiety, depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), substance use and impulsiveness may also influence this relationship (Preston et al. 2012). Based upon their analysis of problem gamblers in outpatient treatment who had committed illegal acts, Granero et al. (2015) proposed that there are four clusters of such gamblers. In brief, cluster 1 presented with more psychopathologies and emotional distress, and had the highest proportion of females. Cluster 2 and 4 had heightened novelty-seeking and were at increased risk of gambling disorder, but cluster 4 was distinguished by greater severity of their disorder. Cluster 3 was differentiated by primarily consisting of young people with university education and moderate psychopathologies. Granero et al.’s (2015) research highlights the range of potentially overlapping factors that may influence gambling-related crime, and which are not yet fully understood. As such, the authors’ conclusion that gamblers who commit crime are a heterogeneous population comprised of multiple subtypes, defined by demographic, psychopathological, clinical and personality traits, seems to be an appropriate, albeit broad, explanation of the elusive relationship between problem gambling and crime. That is, based on the extant, sometimes contradictory, literature on gambling-related crime, it is highly plausible that there is no singular causal pathway between problem gambling and illegal activity.

Discussion

The current review provided evidence that crimes committed by problem gamblers are generally non-violent and motivated by the need to obtain gambling funds (Turner et al. 2009; Abbott et al. 2005; Abbott and McKenna 2005; Productivity Commission 1999; Monash University Centre for Criminology and Criminal Justice 2000). It follows that gambling-related crime is likely often a product of gambling itself, intended to accumulate further funds to gamble, recoup financial shortfalls, or conceal the individual’s gambling from others (Blaszczynski and McConaghy 1994a). Although a causal link between gambling and crime is plausible, it appears that the gambling-crime relationship cannot be explained by financial motivations alone.

Additionally, the relatively recent emergence of studies suggesting that the rate of violent gambling-related crime might also be higher than in non-gambling populations (Rudd and Thomas 2016; Laursen et al. 2016; Turner et al. 2009) may be symptomatic of a wider underestimation of the prevalence of violent gambling-related crimes in the literature. While it is probable that many of these violent crimes were financially-motivated, the broad range of offences committed by participants across these studies necessitated the consideration of other influences beyond financial motivations, for example, risk-taking (Rudd and Thomas 2016; Laursen et al. 2016).

Given that violent gambling-related crimes may be under-reported in the extant literature, greater onus on identifying and addressing the presence and causes of gambling-related crime should be a future priority in both research and the judicial system. As gambling-related crimes are typically interpreted to mean income-generating offences, existing research methodologies may easily, if inadvertently, fail to detect gamblers’ violent crimes. Similarly, gamblers and individuals involved in the judicial system alike are prone to neglecting to report or enquire about these crimes in interviews (Perrone et al. 2013). The resulting lack of awareness and consideration of violent gambling-related crimes in the empirical and judicial domains is one of the greatest barriers to assessing the true nature and impacts of gambling-related crime, and the application of more considered sentencing and therapeutic jurisprudence.

Future research would therefore benefit from directly and explicitly questioning gamblers about violent crimes which they have committed, and whether these stem from the interviewee’s gambling. The inclusion of such questions is a simple way of guiding the study of gambling-related crime towards a more accurate estimate of the prevalence (and by extension, financial and social costs) of violent gambling-related crimes. Furthermore, it is crucial that clinical interventions and judicial systems adopt a comprehensive view of the individual and their history when they have committed gambling-related crime. From the moment that offenders are arrested (if possible), there would be significant benefits in establishing the circumstances motivating their crime and clearly documenting when cases are gambling-related. By making it standard practice to better understand and document the nature and causes of gambling-related crime on a case-by-case basis, these offenders can be channelled into the appropriate avenues of the legal system. While it may be necessary to incarcerate perpetrators of repeated or particularly serious offences (e.g., involving significant breaches of trust, strong violence, or excessive amounts of money) for the purpose of general deterrence, emphasising rehabilitation for minor and first-time offenders may reduce recidivism and the social costs of gambling in the long term. Additionally, the mere act of more thorough documentation of the circumstances of gambling-related crime would aid significantly in clarifying the factors which contribute to gambling-related crime and unifying the literature as it expands in future.

Given that the gambling-crime relationship may be mediated by a range of other factors (Granero et al. 2015), it would also be valuable in both legal and empirical investigations to screen perpetrators for demographic, emotional and psychopathological traits that are believed to be associated with gambling-related crime (e.g. education, antisocial personality, drug use). Identification of such factors may have a dual effect, by helping to determine which gamblers may be more receptive to rehabilitative efforts (within the legal system) and contributing to the identification of patterns or typologies (such as the clusters identified by Granero et al. 2015) of individuals who commit gambling-related crimes across the literature at large.

Gambling-related criminal activities are also a concern within the clinical domain. The DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association 2013) notably omitted the “illegal acts” diagnostic criterion for gambling disorder that was present in its fourth edition. Consequently, the commission of crimes such as forgery, fraud, theft or embezzlement to obtain funds to gamble or pay gambling debts is no longer considered a symptom of the disorder. There has been some controversy over this decision. Researchers and clinicians who supported the DSM-IV-TR’s criteria (American Psychiatric Association 2000) have suggested that the illegal acts item had significant clinical utility (Rash and Petry 2016), for example, as an indicator of greater severity of a gambling disorder. In contrast, studies have demonstrated that removal of this criterion resulted in minimal impact upon the actual prevalence rates of problem gambling. For example, Stinchfield et al. (2015) reported that in an analysis of a number of data sets, the criterion’s removal did not alter the GD diagnostic status in four of eight datasets, four sets each showed one or two individual no longer diagnosed with GD. These authors found that only five individuals (out of 3247 within eight datasets) lost their GD status when evaluated with DSM-5 criteria compared to DSM-IV-TR criteria. Furthermore, Ledgerwood et al. (2007) found that endorsement of the illegal offences item was associated with more severe gambling problems. Therefore, while the extant literature suggests that its elimination from the DSM was prudent, attention to the commission of illegal acts by gambler is valuable to clinicians, as a qualifier of gambling severity when evaluating individual problem gambling cases.

It is also noteworthy that the illegal acts item primarily accounts for non-violent offences (e.g., embezzlement, fraud), and not potential violent offending. This oversight underscores the present review’s findings that violent gambling-related crimes are relatively unexamined, and that violent offenders may represent a particularly severe subset of gamblers (e.g., Rudd and Thomas 2016). Further, it reinforces the importance of adopting a person-centred approach when dealing with problem gamblers. While the illegal acts item may not be diagnostic of problem gambling in and of itself, it can therefore also serve as a valuable indicator of a gambler’s need for and prospects of rehabilitation.

Summary

In sum, the current review provides evidence that gambling-related crime typically takes the form of income-generating, non-violent offences. However, recent studies have also indicated that problem gamblers may commit violent crimes at a higher rate than expected, and potentially at a similar rate to non-violent offences, and these prevalence rates may have been disguised by deliberate and inadvertent under-reporting of gambling-related crimes. Although it is possible to speculate on the causes of these offences based on non-violent gambling-related crimes, there is an overall lack of research that specifically investigates this domain. However, the role of factors such as antisocial personality, impulsiveness and drug use that appear to correlate with the commission of violent crimes by gamblers, warrant future investigation. The uncertainty about the causal relationship between problem gambling and violent crime therefore highlights the need to carefully evaluate individuals who commit gambling-related crime on a case-by-case basis, accounting for their unique histories and criminal profiles. Such comprehensive consideration of individual histories will permit appraisal of the likely cause for their criminal activity, and a greater focus on rehabilitation, rather than strict incarceration, of gambling-related offenders.

References

Abbott, M. W., & McKenna, B. G. (2005). Gambling and problem gambling among recently sentenced women in New Zealand prisons. Journal of Gambling Studies, 21(4), 559–581. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-005-5563-5.

Abbott, M. W., McKenna, B. G., & Giles, L. C. (2005). Gambling and problem gambling among recently sentenced male prisoners in four New Zealand prisons. Journal of Gambling Studies, 21(4), 537–558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-005-5562-6.

Abbott, M. W., & Volberg, R. A. (1999). Gambling and problem gambling in the community: An international overview and critique. The New Zealand Gaming Survey. Report No. 1. Wellington: Department of Internal Affairs.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., Text Revision). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Arthur, J. N., Williams, R. J., & Belanger, Y. D. (2014). The relationship between legal gambling and crime in Alberta. Canadian Journal of Criminology & Criminal Justice, 56(1), 49–84. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjccj.2012.E51.

Bergh, C., & Kühlhorn, E. (1994). Social, psychological and physical consequences of pathological gambling in Sweden. Journal of Gambling Studies, 10(3), 275–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02104968.

Blaszczynski, A. P., & McConaghy, N. (1994a). Antisocial personality disorder and pathological gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 10(2), 129–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02109936.

Blaszczynski, A. P., & McConaghy, N. (1994b). Criminal offenses in gamblers anonymous and hospital treated pathological gamblers. Journal of Gambling Studies, 10(2), 99–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02109935.

Blaszczynski, A., McConaghy, N., & Frankova, A. (1989). Crime, anti-social personality and pathological gambling. Journal of Gambling Behavior, 5, 137–152.

Crofts, P. (2003). Problem gambling and property offences: An analysis of court files. International Gambling Studies, 3, 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/1356347032000142289.

Delfabbro, P. H. (2010). Exploring the myths around gambling. Paper presented at Gambling Awareness Week, Melbourne Town Hall, Melbourne.

Folino, J. O., & Abait, P. E. (2009). Pathological gambling and criminality. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 22(5), 477–481. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e32832ed7ed.

Gorsane, M. A., Reynaud, M., Vénisse, J., Legauffre, C., Valleur, M., Magalon, D., et al. (2017). Gambling disorder-related illegal acts: Regression model of associated factors. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(1), 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.003.

Granero, R., Fernández-Aranda, F., Aymamí, N., Gómez-Peña, M., Fagundo, A. B., Sauchelli, S., et al. (2015). Subtypes of pathological gambling with concurrent illegal behaviors. Journal of Gambling Studies, 31(4), 1161–1178. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-014-9499-5.

Granero, R., Penelo, E., Stinchfield, R., Fernández-Aranda, F., Aymamí, N., Gómez-Peña, M., et al. (2014). Contribution of illegal acts to pathological gambling diagnosis: DSM-5 implications. Journal of Addictive Diseases, 33(1), 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/10550887.2014.882730.

Hartmann, M., & Blaszczynski, A. (2016). The longitudinal relationship between psychiatric disorders and gambling disorders. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-016-9705-z.

Kuoppamäki, S., Kääriäinen, J., & Lind, K. (2014). Examining gambling-related crime reports in the national Finnish police register. Journal of Gambling Studies, 30, 967–983. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-013-9393-6.

Lahn, J. (2005). Gambling among offenders: results from an Australian survey. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 49(3), 343–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624x04270790.

Laursen, B., Plauborg, R., Ekholm, O., Larsen, C. V. L., & Juel, K. (2016). Problem gambling associated with violent and criminal behaviour: A Danish population-based survey and register study. Journal of Gambling Studies, 32, 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-015-9536-z.

Ledgerwood, D. M., Weinstock, J., Morasco, B. J., & Petry, N. M. (2007). Clinical features and treatment prognosis of pathological gamblers with and without recent gambling-related illegal behavior. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 35(3), 294–301. Retrieved from http://jaapl.org/content/35/3/294.long.

Lesieur, H. R. (1984). The chase: Career of the compulsive gambler. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman Publishing Co.

Lloyd, C. D., Chadwick, N., & Serin, R. C. (2014). Associations between gambling, substance misuse and recidivism among Canadian offenders: A multifaceted exploration of poor impulse control traits and behaviours. International Gambling Studies, 14(2), 279–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2014.913301.

Martin, G., Macdonald, S., & Ishiguro, S. (2013). The role of psychosocial characteristics in criminal convictions among cocaine and gambling clients in treatment. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 11(2), 162–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-012-9406-1.

May-Chahal, C., Humphreys, L., Clifton, A., Francis, B., & Reith, G. (2017). Gambling harm and crime careers. Journal of Gambling Studies, 33(1), 65–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-016-9612-z.

Meyer, G., & Stadler, M. A. (1999). Criminal behavior associated with pathological gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 15(1), 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023015028901.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.

Monash University Centre for Criminology & Criminal Justice. (2000). The impact of gaming and crime statistics. Report prepared for the Victorian Casino and Gaming Authority: Melbourne.

Pastwa-Wojciechowska, B. (2011). The relationship of pathological gambling to criminality behavior in a sample of Polish male offenders. Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research, 17(11), 669–675. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.882054.

Perrone, S., Jansons, D., & Morrison, L. (2013). Problem gambling and the criminal justice system. Melbourne, Australia: Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation.

Preston, D. L., McAvoy, S., Saunders, C., Gillam, L., Saied, A., & Turner, N. E. (2012). Problem gambling and mental health comorbidity in Canadian federal offenders. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 39(10), 1373–1388. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854812448786.

Productivity Commission. (1999). Australia’s gambling industries, Summary Report No. 10. Canberra: AusInfo.

Productivity Commission. (2010). Gambling. Productivity commission inquiry report. Volume 1. Report no. 50. Canberra: Productivity Commission.

Rash, C. J., & Petry, N. M. (2016). Gambling disorder in the DSM-5: Opportunities to improve diagnosis and treatment especially in substance use and homeless populations. Current Addiction Reports, 3(3), 249–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-016-0112-0.

Riley, B., & Oakes, J. (2015). Problem gambling among a group of male prisoners: Lifetime prevalence and association with incarceration. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 48(1), 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004865814538037.

Rudd, C., & Thomas, S. D. M. (2016). The prevalence, mental health and criminal characteristics of potential problem gamblers in a substance using treatment seeking population. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 14(5), 700–714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-015-9604-8.

Sakurai, Y., & Smith, R. G. (2003). Gambling as a motivation for the commission of financial crime: Report No. 256. Canberra: Australian Institute of Criminology.

Stinchfield, R., McCready, J., Turner, N. E., Jimenez-Murcia, S., Petry, N. M., Grant, J., et al. (2015). Reliability, validity, and classification accuracy of the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for gambling disorder and comparison to DSM-IV. Journal of Gambling Studies, 32(3), 905–922. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-015-9573-7.

Templer, D. I., Kaiser, G., & Siscoe, K. (1993). Correlates of pathological gambling propensity in prison inmates. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 34(5), 347–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-440X(93)90022-V.

Tessényi, J., & Kovács, P. (2016). A study of the connection between gambling and crime in Hungarian prisons. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 47, 176–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2016.04.004.

Turner, N. E., McAvoy, S., Ferentzy, P., Matheson, F. I., Myers, C., Jindani, F., et al. (2017). Addressing the issue of problem gambling in the criminal justice system: A series of case studies. Journal of Gambling Issues, 35, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.v0i35.3973.

Turner, N. E., Preston, D. L., McAvoy, S., & Gillam, L. (2013). Problem gambling inside and out: The assessment of community and institutional problem gambling in the Canadian correctional system. Journal of Gambling Studies, 29(3), 435–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-012-9321-1.

Turner, N. E., Preston, D. L., Saunders, C., McAvoy, S., & Jain, U. (2009). The relationship of problem gambling to criminal behavior in a sample of Canadian male federal offenders. Journal of Gambling Studies, 25, 153–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-009-9124-1.

Williams, R. J., Royston, J., & Hagen, B. F. (2005). Gambling and problem gambling within forensic populations. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 32(6), 665–689. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854805279947.

Williams, R. J., Volberg, R. A., & Stevens, R. M. G. (2012). The population prevalence of problem gambling: Methodological influences, standardized rates, jurisdictional differences, and worldwide trends. Guelph: Ontario Problem Gambling Research Centre.

Funding

This work was supported by funding provided by the School of Psychology, Science Faculty, the University of Sydney. This work was supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Research Award [DE1060100459] awarded to Dr. Sally Gainsbury.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Alex Blaszczynski has received direct and indirect funding over the last 3 years for research projects, consultancy, honoraria, royalties for published books, costs covering travel expenses to attend conferences and government meetings including from La Loterie Romande (Switzerland), Club NSW (Australia), Comelot (UK), La Française des Jeux (France), Loto-Québec (Québec, Canada), National Lottery (Belgium), Aristocrat Leisure Industries, Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, Australian Media and Communication Authority, Responsible Gambling Trust/GambleAware, Manitoba Gambling Research Program, NSW Office of Liquor, Gaming, & Racing, Gambling Research Australia, National Association for Gambling Studies, USA National Council on Problem Gambling, Le Comité d’organisation Congrès international sur les troubles addictifs, Japan Society for the Behavioral Addiction, and funds from Taylor & Francis for acting as Editor-in-Chief of International Gambling Studies. Sally Gainsbury has received direct and indirect funding over the last 3 years for research projects, consultancy, honoraria, costs covering travel expenses to attend conferences and meetings including from from the Australian Research Council, Australian Media and Communication Authority, Commonwealth Bank Australia, University of Sydney, Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, National Association for Gambling Studies, Gambling Research Australia, Echo/Star Entertainment, UK Responsible Gambling Trust/Gamble Aware, KPMG Australia, KPMG Tokyo, Cultural and Indigenous Research Centre Australia, Health Outcomes International, ORC International, Communio, Manitoba Gambling Research Program, GP Consulting, Nova Scotia Provincial Lotteries and Casino Corporation, Gambling Research Exchange Ontario, British Columbia Lottery Corporation, Alberta Gambling Research Institute, Nordic Association for Information on Gambling Addiction, Responsible Gambling Council, National Council on Problem Gambling International Advisory Board (Singapore), Minter Ellison, Victorian Community Clubs.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Adolphe, A., Khatib, L., van Golde, C. et al. Crime and Gambling Disorders: A Systematic Review. J Gambl Stud 35, 395–414 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-018-9794-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-018-9794-7