Abstract

Purpose of review

This paper reviews recent research related to the revisions of the gambling disorder (GD) criteria, including the elimination of the illegal acts criterion and the lowered diagnostic threshold.

Recent findings

Studies suggest that the removal of the illegal acts criterion has little impact in terms of prevalence or loss of diagnostic status among gamblers, especially when considered in combination with the lowered diagnostic threshold. Overall, prevalence rates will increase modestly with the lowered threshold in community samples of gamblers. However, increases in GD prevalence rates may be more notable in settings that serve individuals at higher risk for gambling problems (e.g., substance abuse treatment clinics and homeless persons).

Summary

Changes to the GD diagnostic criteria may lead to increased recognition of gambling problems, particularly in settings that serve high-risk populations. These changes also may necessitate the training of more clinicians in the delivery of efficacious gambling treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gambling disorder (GD) is characterized as a persistent pattern of gambling resulting in significant impairment or distress [1]. According to the current DSM-5, diagnosis of GD is made when an individual meets four or more of the following criteria within a 12-month period: (a) needs to gamble with increasing amounts of money in order to achieve desired excitement; (b) exhibits restlessness or irritability when trying to decrease gambling activity; (c) experiences loss of control over gambling; (d) is preoccupied with gambling; (e) often gambles in response to distress; (f) chases losses; (g) lies to conceal extent of gambling involvement; (h) jeopardizes relationships, educational, or employment opportunities because of gambling; and (i) relies on others for financial bailouts for gambling-related financial crises.

Several changes related to the diagnosis of gambling problems were introduced in the fifth revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5) [1]. Among these changes, the disorder’s name was changed from pathological gambling to GD, and GD was moved from the Impulse Control Disorders Not Elsewhere Classified chapter to the newly expanded Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders section. This latter modification signals a formal recognition of behavioral addictions, which are addictions characterized by their lack of psychoactive agents. Additional changes to the diagnosis of GD include the elimination of one criterion and the lowering of the diagnostic threshold.

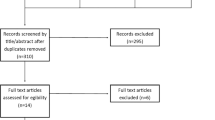

This paper will review briefly the recent research related to these latter two changes. In particular, we will focus on how these DSM-5 changes will impact diagnosis and treatment of individuals with GD and areas in need of additional research.

Elimination of Illegal Acts Criterion

The DSM-IV GD diagnostic set included an item related to engagement in illegal acts to support gambling, and involving acts such as forgery, fraud, theft, or embezzlement [2]. This criterion was removed from the GD diagnostic set for DSM-5, paralleling the deletion of a similar item in the alcohol and drug use disorders diagnostic sets [3]. The decision to remove the illegal acts item from the GD criteria was based on its minimal contribution to diagnostic accuracy [4] and reduced assessment burden [5•]. This conclusion was supported by analyses of DSM-IV gambling criteria using data from several population-based samples in the US [6, 7] and Great Britain [8, 9]. These studies [6–9] suggested that the illegal acts criterion was endorsed at significantly lower rates compared to other diagnostic items and that illegal acts were usually endorsed only by the most severe gamblers. These severe gamblers already endorsed other criteria sufficient to meet diagnosis and thus the illegal acts item was deemed unnecessary for diagnosis.

Others [10, 11] highlight the conceptual role of illegal acts as a diagnostic criterion and whether these behaviors represent a core component of the underlying psychopathology or rather represent a possible consequence of the disorder. Consequences of mental disorders are less likely to be useful diagnostic indicators, especially if they occur further into disease severity or disease progression as appears to be the case for gambling-related illegal acts. For example, in a sample of 2750 gamblers calling a gambling helpline [12•], only 6 and 19 % of those endorsing 1–2 or 3–4 diagnostic symptoms reported gambling-related illegal acts. However, rates among individuals higher on the severity spectrum, those exhibiting 5–6 symptoms and 7–9 symptoms, were much higher with 36 and 75 % reporting illegal acts, respectively. Similar associations between the proportion of gamblers endorsing illegal acts and the disorder severity are evident and perhaps even more pronounced in population-based studies [e.g., 7].

Some researchers and clinicians [e.g., 13–15] have expressed concerns about the removal of the illegal acts criterion, highlighting its clinical utility, loss of heterogeneity with its removal, and the higher frequencies of gamblers reporting illegal acts among gambling subpopulations (i.e., clinical samples, offenders). Clinicians likely do see higher proportions of treatment-seeking gamblers reporting illegal acts (23–41 %) [10, 12•, 16, 17•], especially as compared to population-based samples of gamblers (0.1–0.4 %) [6, 8] and even community samples of those meeting DSM-IV gambling criteria (19 %) [7]. Gamblers seeking treatment tend to be higher on the severity spectrum, and, as noted above, illegal acts are more prevalent among these higher severity gamblers. Nonetheless, its frequency is still low relative to the other diagnostic criteria. For example, in a treatment research sample, 41 % of the sample endorsed illegal acts compared to endorsement rates of 63–96 % of other diagnostic criteria [17•].

With respect to clinical utility, the presence of illegal acts is associated with more severe GD, greater dysfunction in other domains (e.g., unemployment; psychiatric comorbidity, suicide attempts), and more gambling-related debt [10, 12•, 16]. These gamblers benefit from treatment, but do not reach subthreshold diagnostic levels as typical of those without a history of such behavior [16], suggesting that individuals reporting gambling-related illegal acts may need more intensive or longer duration gambling treatments. However, this research question remains unanswered as of yet. Overall, these findings suggest that although illegal acts are not necessarily vital to diagnosis, clinicians may find assessment of illegal acts to be a valuable aspect of good clinical interviewing. This information may be useful as an indicator to more fully assess functioning in other domains, such as patient needs (e.g., debt and legal counseling), and possibly to more intensive treatment options. In addition, this criterion is now subsumed under another related criterion (i.e., lies to others about the extent of gambling), thereby encouraging clinicians to continue inquiring specifically about illegal acts.

Relatively few gamblers with problems will be undiagnosed due to the removal of the illegal acts criterion as a stand-alone criterion [5•, 12•, 17•, 18•, 19], in part because less severe gamblers (i.e., those just meeting the diagnostic threshold) are less likely to endorse illegal acts as noted above. Using a combined eight studies from three countries including both community gamblers (gambled at least once in past year) and treatment samples, Stinchfield et al. [18•] examined the proportions impacted by the elimination of the illegal acts criterion. Endorsement of illegal acts was minimal in the community samples (0–5 %); however, rates of illegal acts ranged from 19 to 67 % among the treatment samples. Despite frequent endorsement of illegal acts in some of the included studies, elimination of the illegal acts criterion (even when it was not subsumed under another criterion) resulted in loss of diagnosis in only 5 of the 3247 (0.15 %) gamblers from the combined sample.

Weinstock et al. [12•] also examined the impact of the illegal acts criterion removal, in relation to the existing DSM-IV diagnostic threshold as well as the lowered DSM-5 threshold. Among callers to a gambling help-line, 864 (31 % of N = 2750) gamblers endorsed gambling-related illegal acts. However, only a small minority (n = 42, 1.5 %) would lose diagnostic status if this criterion was removed and the DSM-IV diagnostic threshold was not lowered (i.e., 5 of 9 criteria). Even fewer (N = 12, 0.4 %) are impacted when the illegal acts criterion is removed and the diagnostic threshold concurrently lowered to 4 of 9 criteria [12•], consistent with the existing DSM-5 GD formulation. The removal of the illegal acts criterion may have more pronounced effects in samples of gamblers from offender populations, where rates of illegal acts are higher. Among gamblers endorsing between 1 and 4 DSM-IV criteria, the rate of illegal acts endorsement was 9.9 %, and among gamblers meeting DSM-IV criteria, the rate of illegal acts was much higher at 44.0 % [15]. Although endorsement of illegal acts is higher among gamblers from offender populations, the illegal acts criterion is still the least endorsed criterion of the GD diagnostic set (44 % compared to rates of 54–88 % for other criteria among gamblers meeting DSM-IV criteria). Its removal resulted in loss of diagnostic status for only 6 individuals (0.9 % of 676 offenders) [15].

As noted in the DSM-5 [1] and described earlier, illegal acts can be considered under the “lying to others” criterion, and this strategy further mitigates the loss of diagnostic status for some individuals. In the same offender sample [15], prevalence before the removal of illegal acts was 10.2 % (using a threshold of 4/10 criteria), and GD prevalence decreased to 9.3 % with the removal of illegal acts (4/9). However, when Turner et al. [15] combined the DSM-5 with illegal acts and lying to others criteria, diagnostic status was retained for some individuals with a prevalence of 9.9 % (4/9 with illegal acts and lying to others criteria combined).

Lowering the Diagnostic Threshold

Related to the discussion of prevalence rates, the diagnostic threshold was reduced from 5 of 10 criteria for DSM-IV to 4 of 9 criteria in DSM-5 [1, 2]. With the reduction in the diagnostic threshold, GD prevalence rates will rise modestly, although some settings that serve those with higher risk for gambling problems may see more gamblers meeting criteria. In Petry et al.’s [5•] analysis of the impact of DSM-5 changes in the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Disorders (NESARC; N = 43,093), prevalence increased from 0.16 to 0.27 % when moving from DSM-IV (5/10 criteria) to DSM-5 (illegal acts removed and threshold lowered: 4/9 criteria). Petry et al. [17•] also evaluated the impact of the threshold changes in a sample of 3710 individuals from five studies that included randomly selected household residents, gambling patrons, individuals in intervention studies, and individuals in community-based gambling treatment. Overall, GD prevalence rates for the full sample were 16.2 % using DSM-IV criteria and 17.9 % using DSM-5 criteria. However, among the subsample from brief intervention studies (N = 375) [20], which included problem gamblers not specifically seeking treatment for gambling, prevalence rates rose more sharply from 46.4 % using DSM-IV criteria to 58.1 % using DSM-5 criteria.

The lowering of the diagnostic threshold in DSM-5 may ease overall access to treatment for these problem gamblers, and some [e.g., 13] called for further lowering of the diagnostic threshold to promote easier access to treatment among a broader swath of problem gamblers. However, such a change would have substantial impacts on the prevalence rates. In Petry et al.’s [5•] study using the NESARC sample, prevalence increased substantially as the threshold was lowered, from 0.27 % using the DSM-5 four criteria cut-off to 0.60 % using a three criteria cut-off, 1.22 % using a two criteria cut-off, and 2.95 % using one criterion as the cut-off. These lower diagnostic thresholds were considered for GD but ultimately were rejected by the DSM-5 Substance Use and Related Disorders Workgroup given the potentially large impact on prevalence, as well as lack of research on clinical significance and the stability of these lower thresholds [3, 4]. Nonetheless, further clinical work and research with sub-diagnostic gamblers is encouraged [4], including investigation of the extent to which these gamblers differ substantially from those with GD and the proportions who meet fewer criteria that go on to develop four or more criteria.

The Substance Use and Related Addictive Disorders Workgroup also explored whether adaptation of the substance use disorder criteria was applicable to GD [3, 4]. In one such exploration, Denis et al. [21] modeled GD criteria based on the DSM-IV substance dependence criteria and assessed diagnostic concordance with alternate classification methods (i.e., DSM-IV, DSM-IV with illegal acts removed, DSM-5). The authors [21] found that the adapted criteria had similar reliability and classification accuracy relative to the alternate diagnostic formulations and similar prevalence rates as compared to existing DSM-5 criteria. These results suggest that GD criteria modeled after substance use disorder criteria may be a viable option for future DSM revisions. However, it is important to note that the Denis et al. [21] study used adapted criteria modeled on DSM-IV substance dependence rather than the current DSM-5 substance diagnostic formations, which combine the DSM-IV abuse and dependence criteria for substance use disorders into a single category. In addition, this study is one of the only investigations adapting the SUD criteria directly to gambling, while there are decades of research supporting the existing criteria.

Clinical implications

The primary clinical implications for the changes to GD in the DSM-5 are that prevalence rates and recognition of the disorder should increase and especially in settings that serve relatively high proportions of persons who gamble problematically but are not seeking services explicitly for gambling. Two such settings are substance abuse treatment clinics and homeless shelters. Meta-analytic estimates [22] suggest that 13.7 % of clients in substance abuse treatment settings meet DSM-IV criteria for pathological gambling and an additional 22.8 % (at least a proportion of whom will meet new DSM-5 criteria) have subthreshold problem gambling. Two studies [21, 23] examined gambling prevalence when moving from DSM-IV to the DSM-5 criteria among individuals with addictions. Denis et al. [21] assessed gambling disorder among new admissions to an addiction treatment center, and GD prevalence rose from 20.5 to 25.5 % moving from DSM-IV to DSM-5 diagnostic systems. Rennert et al. [23] examined DSM-IV and DSM-5 prevalence rates in a sample of 6613 individuals with substance dependence; GD rates increased from 8.5 to 10.3 %. Based on these studies, addictions treatment clinics might expect increases in the magnitude of 20–24 % in individuals meeting criteria for GD.

Among homeless individuals, rates range from 10.0 to 46.2 % for problem gambling [24–27] and 5.5 to 25.0 % for DSM-IV pathological gambling [24–26]. These rates are likely to increase by about 10–20 % if DSM-5 diagnoses are applied based on findings in other high risk subgroups [12•, 17•, 21, 23].

The DSM-5 changes to GD and related prevalence increases may spur changes in clinical practice. Clinicians in addictions and homeless service settings may become more attuned to GD with its alignment with SUDs [28] and, therefore, may be more likely to screen persons for gambling and provide interventions to those who do meet criteria. As more individuals are screened for and referred to gambling treatment, additional staff training in screening and treatment of GD may be necessary. Given strong associations of gambling problems with homelessness, clinicians at homeless shelters should also be trained in screening and referral procedures.

Importantly, we [20] have found that screening and brief interventions can substantially decrease gambling problems, even in non-treatment-seeking gamblers. Petry et al. [20] screened individuals primarily from substance use treatment and medical clinics and randomized those with problem gambling to one of four conditions: an assessment only control, a single 10-min session of brief advice, a single 50-min session of motivational enhancement therapy (MET), or MET plus 3 additional 50-min sessions of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Those randomized to the 10-min brief advice condition significantly reduced their gambling from baseline to the week 6 follow-up relative to those in the control condition. These results are encouraging as these brief interventions, especially the 10-min brief advice format, are likely more amenable to staff training and adoption compared to extensive multi-session formats. For example, in an addictions treatment clinic or homeless shelter, it might be possible to train most if not all clinicians to implement screening and brief advice for gambling problems, while referring more severe cases to specialized gambling treatment [e.g., 29].

Conclusions

The majority of changes to the GD diagnostic criteria for DSM-5 are likely welcome, including the newly lowered threshold. The removal of illegal acts has raised concern among some [e.g., 13–15] but research to date suggests the elimination of illegal acts affects a small number of gamblers in terms of loss of diagnostic status, even among sub-populations of gamblers where illegal acts are more prevalent (i.e., offenders). The re-categorization of GD as a behavioral addiction is perhaps the most controversial issue, and it has spurred much discussion and debate [e.g., 30–34]. Regardless of the conceptual issues surrounding this move, GD’s classification among addictive disorders may bring it more attention from public health officials and clinicians alike. Especially in substance abuse treatment settings and homeless shelters, where rates of gambling problems are much higher, the increased awareness of GD may translate into more systematic screening efforts and referral to gambling treatment. Research on the GD diagnostic criteria should continue in preparation for DSM-6, and it is possible that more substantial changes will be considered if empirical data support them. Until then, the DSM-5 GD diagnostic formulation appears to retain or improve on the functionality of DSM-IV with modest impacts on prevalence rates. However, increased changes in prevalence may have more impact in settings that serve populations with high proportions of persons who gamble regularly and problematically but who are not expressly seeking gambling treatment.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author; 2013.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.-text revision). Washington, DC: Author; 2000.

Hasin DS, O’Brien CP, Auriacombe M, Borges G, Bucholz K, Budney A, et al. DSM-5 criteria for substance use disorders: recommendations and rationale. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:834–51.

Petry NM, Blanco C, Auriacombe M, Borges G, Bucholz K, Crowley TJ, et al. An overview of and rationale for changes proposed for pathological gambling in DSM-5. J Gambl Stud. 2014;30:493–502.

Petry NM, Blanco C, Jin C, Grant BF. Concordance between gambling disorder diagnosis diagnoses in the DSM-IV and DSM-5: results from the National Epidemiological Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions. Psychol Addict Behav. 2014;28:586–91. This article assesses the impact of the DSM-5 changes to gambling disorder criteria in a large nationally representative sample.

Strong DR, Kahler CW. Evaluation of the continuum of gambling problems using the DSM-IV. Addiction. 2007;102:713–21.

Toce-Gerstein M, Gerstein DR, Volberg RA. A hierarchy of gambling disorders in the community. Addiction. 2003;98:1661–72.

McBride O, Adamson G, Shevlin M. A latent class analysis of DSM-IV pathological gambling criteria in a nationally representative British sample. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178:401–7.

Orford J, Sposton K, Erens B. SOGS and DSMIV in the British Gambling Prevalence Survey: reliability and factor structure. Int Gambl Stud. 2001;3:53–65.

Granero R, Penelo E, Stinchfield R, Fernandez-Aranda F, Aymami N, Gomez-Pena M, et al. Contribution of illegal acts to pathological gambling diagnosis: DSM-5 implications. J Addict Dis. 2014;33:41–52.

Grant JE, Potenza MN. Commentary: Illegal behavior and pathological gambling. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35:302–5.

Weinstock J, Rash C, Burton S, Moran S, Biller W, O’Neil K, et al. Examination of proposed DSM-5 changes to pathological gambling in a helpline sample. J Clin Psychol. 2013;69(12):1305–14. Assesses the impact of DSM-5 changes to gambling disorder criteria in a large sample of gamblers calling a state gambling helpline.

Mitzner GB, Whelan JP, Meyers AW. Comments from the trenches: Proposed changes to the DSM-V classification of pathological gambling. J Gambl Stud. 2011;27:517–21.

Shaffer HJ, Martin R. Disordered gambling: etiology, trajectory, and clinical considerations. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2011;7:483–510.

Turner NE, Stinchfield R, McCready J, McAvoy S, Ferentzy P. Endorsement of criminal behavior amongst offenders: implications for DSM-5 gambling disorder. J Gambl Stud. 2015. doi:10.1007/s10899-015-9540-3.

Ledgerwood DM, Weinstock J, Morasco BJ, Petry NM. Clinical features and treatment prognosis of pathological gamblers with and without recent gambling-related illegal behavior. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35:294–301.

Petry NM, Blanco C, Stinchfield R, Volberg R. An empirical evaluation of proposed changes for gambling diagnosis in the DSM-5. Addiction. 2012;108:575–81. Examines the impact of DSM-5 changes to gambling disorder criteria across several different subsamples of gamblers; includes community gamblers, gambling patrons, individuals participating in gambling intervention studies, and gamblers seeking gambling treatment in the community.

Stinchfield R, McCready J, Turner NE, Jimenez-Murcia S, Petry NM, Grant J, et al. Reliability, validity, and classification accuracy of the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for gambling disorder and comparison to DSM-IV. J Gambl Stud. 2015. doi:10.1007/s10899-015-9573-7. This study assesses the impact of DSM-5 changes to gambling disorder criteria across diverse samples; includes data from 8 studies in 3 countries.

Zimmerman M, Chelminski I, Young D. A psychometric evaluation of the DSM-IV pathological gambling diagnostic criteria. J Gambl Stud. 2006;22:329–37.

Petry NM, Weinstock J, Ledgerwood DM, Morasco B. A randomized trial of brief interventions for problem and pathological gamblers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:318–28.

Denis C, Fatséas M, Auriacombe M. Analyses related to the development of DSM-5 criteria for substance use related disorders: An assessment of pathological gambling criteria. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;122:22–7.

Cowlishaw S, Merkouris S, Chapman A, Radermacher H. Pathological and problem gambling in substance use treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Subst Abus Treat. 2014;46:98–105.

Rennert L, Denis C, Peer K, Lynch KG, Gelernter J, Kranzler HR. DSM-5 gambling disorder: prevalence and characteristics in a substance use disorder sample. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;22:50–6.

Matheson FI, Devotta K, Wendaferew A, Pedersen C. Prevalence of gambling problems among the clients of a Toronto homeless shelter. J Gambl Stud. 2014;30:537–46.

Nower L, Eyrich-Garg KM, Pollio DE, North CS. Problem gambling and homelessness: results from an epidemiologic study. J Gambl Stud. 2015;31:533–45.

Shaffer HJ, Freed CR, Healea D. Gambling disorders among homeless persons with substance use disorders seeking treatment at a community center. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:1112–7.

Sharman S, Dreyer J, Aitken M, Clark L, Bowden-Jones H. Rates of problematic gambling in a British homeless sample: a preliminary study. J Gambl Stud. 2015;31:525–32.

Weinstock J, Rash CJ. Clinical and research implications of gambling disorder in DSM-5. Curr Addict Rep. 2014;1:159–65.

Petry NM. Pathological gambling: etiology, comorbidity, and treatment. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2005.

Billieux J, Schimmenti A, Khazaal Y, Maurage P, Heeren. Are we overpathologizing life? A tenable blueprint for behavioral addiction research. J Behav Addict. 2015;4:119–23.

Blaszczynski A. Commentary on: Are we overpathologizing everyday life? A tenable blueprint for behavioral addiction research. J Behav Addict. 2015;4:142–4.

Chamberlain SR, Lochner C, Stein DJ, Goudriaan AE, van Holst RJ, Zohar J, et al. Behavioral Addiction—a rising tide? Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.08.013.

Clark L. Commentary on: Are we overpathologizing everyday life? A tenable blueprint for behavioral addiction research. J Behav Addict. 2015;4:132–4.

Potenza MN. Non-substance addictive behaviors in the context of DSM-5. Addict Behav. 2014;39:1–2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Carla J. Rash reports no conflicts of interest.

Nancy M. Petry has served as an expert witness in legal cases related to gambling and she wrote a review article for the National Gambling Trust. She also served on the Workgroup for Substance Use and Related Disorders for the DSM-5, for which she received no compensation.

Carla J. Rash and Nancy M. Petry report grants from National Institutes of Health R01-DA13444, P50-DA09241, P60-AA03510, R01- AA021446, R01-AA023502, R01-DA021567, and R21-DA031897.

The views and opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any sponsoring organizations, agencies, or governments.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Gambling

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rash, C.J., Petry, N.M. Gambling Disorder in the DSM-5: Opportunities to Improve Diagnosis and Treatment Especially in Substance Use and Homeless Populations. Curr Addict Rep 3, 249–253 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-016-0112-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-016-0112-0