Abstract

The purpose of this study is to examine the mediating role of collective self-esteem in the relationship between employees’ perceived corporate social responsibility (CSR) and their work engagement. We also explore the moderating role of employees’ concern for face in the linkage between their perceived CSR and collective self-esteem. A two-wave panel data from a final sample of 217 employees in six companies in Wuhan, China, completed the questionnaire survey. Employees’ perceived CSR has a direct and positive effect on their work engagement, which is partially mediated by their collective self-esteem. Furthermore, employees’ concern for face moderates the relationship between their perceived CSR and collective self-esteem. CSR has a stronger effect on collective self-esteem for employees who concern more for face than for those who concern less for face. Understanding the outcomes, the mediating mechanisms, as well as the boundary conditions of perceived CSR on work engagement, help firms to better formulate their CSR strategy. First, we introduce collective self-esteem as an important mediating mechanism in the relationship between CSR and employees’ work engagement. Second, we identify concern for face as an important limiting condition in the linkage between CSR and employees’ collective self-esteem. Finally, previous research investigating employees’ reactions to CSR has predominantly been conducted in the West. We conduct our study in the Chinese or Confucian context to provide some new and complementary insights.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is now a leading topic in business academia across the world. CSR could be defined either narrowly as ‘subset of corporate responsibilities that deals with a company’s voluntary/discretionary relationships with its societal and community stakeholders’ (Waddock, 2004: p. 10), or broadly as having economic, legal, ethical and discretionary/philanthropic components or dimensions (Carroll, 1999). In this research, we followed the mainstream to understand CSR as firm actions that aim to further some social or environmental good beyond its merely economic considerations (Aguilera, Rupp, Williams, & Ganapathi, 2007; Davis, 1973; Eells & Walton, 1974; McWilliams & Siegel, 2001).

Research on CSR has generally found its positive effect on corporate financial performance (see Griffin & Mahon, 1997; Peloza, 2009, for reviews). One of the most important ways that translating CSR into organisational financial performance is through its positive effect on employees’ job performance (Ali, Rehman, Ali, Yousaf, & Zia, 2010; Story & Neves, 2015). Therefore, it is not surprising that to understand the linkage between CSR and employees’ work behaviour has received tremendous attention from both academia and practitioners during the past four decades. Extensive evidence demonstrates a positive effect of CSR, corporate social performance or corporate citizenship on employee-related outcomes such as job satisfaction (Valentine & Fleischman, 2008), organisational commitment (Aguilera, Rupp, Ganapathi, & Williams, 2006), organisational identification (Kim, Lee, Lee, & Kim, 2010) and organisational citizenship behaviour (Abdullah & Rashid, 2012).

Unfortunately, despite the various benefits of CSR, existing literature has seldom investigated why and when CSR may influence employees’ behaviour and performance at work (Aguinis & Glavas, 2012; Jones, Willness, & Madey, 2014). Work engagement is a good indicator of job performance (Bakker, Demerouti, & Verbeke, 2004; Salanova, Agut, & Peiró, 2005; Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Demerouti, & Schaufeli, 2009), or even ‘a better predictor of job performance than are many earlier constructs’ (Bakker, 2011: p. 265). When employees are fully engaged, they are connected with their work roles physically, cognitively and emotionally; they experience positive emotions and good health; they create job resources (Kahn, 1990) and they focus their energy on achieving organisational goals and transferring their engagement to the people around them (Macey, Schneider, Barbera, & Young, 2009). Given the particular role of work engagement in organisational performance, scholars have recently begun to pay more attention to the effect of CSR on employee engagement (Caligiuri, Mencin, & Jiang, 2013; Glavas, 2016; Lin, 2010).

However, despite these endeavours, the calls remain for more understanding about the mechanisms linking CSR to individual-level outcomes including work engagement (Aguinis & Glavas, 2012; Jones et al., 2014). Our current study responds to this call by exploring why and when CSR affects employees’ work engagement. Drawing on social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1985), we first argue that CSR increases employees’ work engagement by promoting their collective self-esteem which is the self-esteem associated with the firm (Dutton & Dukerich, 1991; Tyler & Blader, 2000). In addition, self-esteem in Confucian cultures, such as China, is indistinguishable from the concept of face (Hwang, 2006), which is understood as an individual’s contingent self-esteem (Ng, 2001). Different people within the same culture may have different levels of concern for their self-esteem or face (Bao, Zhou, & Su, 2003; White, Tynan, Galinsky, & Thompson, 2004). Thus, we further argue that the magnitude of the effect of CSR on collective self-esteem is influenced by employees’ concern for face. Employees who concern more for face will benefit more (receive more collective self-esteem) from CSR than those who concern less for face. Putting the mediating effect of collective self-esteem and the moderating effect of concern for face together, we suggest that the indirect effect of CSR on work engagement through collective self-esteem will be moderated by employees’ concern for face.

This study contributes to the CSR literature in the following three aspects. First, although prior studies have suggested that CSR has a positive effect on job performance (Story & Neves, 2015), the underlying mechanisms are still to be revealed. We extend this line of research by considering collective self-esteem as an important mechanism through which employees’ perceived CSR impacts their work engagement. Second, we identify face as an important limiting condition in the linkage between employees’ perceived CSR and their collective self-esteem. People with different levels of concern for face tend to receive different levels of collective self-esteem from their firms’ CSR. Finally, previous research investigating employees’ reactions to CSR has predominantly been conducted in the West (Abdullah & Rashid, 2012; Aguilera et al., 2006; Brammer, Millington, & Rayton, 2007; Kim et al., 2010). We conduct our study in the Chinese or Confucian context to provide some new and complementary insights.

Theory and hypotheses

CSR is widely documented to relate to employees’ attitudinal and behavioural outcomes (e.g. Glavas & Kelley, 2014; Jones, 2010; Rupp, Shao, Thornton, & Skarlicki, 2013). To date, handful studies have linked CSR to employee (work) engagement. For instance, Caligiuri et al. (2013) reported a positive relationship between CSR and employee engagement. Esmaeelinezhad, Boerhannoeddin, and Singaravelloo (2015) identified organisational identification as mediating mechanism in this relationship. Gao’s (2014) China-based study further identified perceived organisational support and Chinese values as mediating mechanisms linking CSR to employee engagement. But the mediating role of perceived organisational support is not supported in the US-based study conducted by Glavas (2016). The author only reported a positive mediating role of authenticity in the relationship between CSR and employee engagement.

In general, prior studies not only demonstrate contradicting findings about the underlying mechanisms linking CSR to employee engagement, but also raise calls for more investigations into the mechanisms linking CSR to individual-level outcomes including work engagement (Aguinis & Glavas, 2012; Jones et al., 2014). In the current study, we extend this line of research to suggest a mediating role of collective self-esteem in the relationship between employees’ perceived CSR and their work engagement. We draw on social identity theory to build our arguments.

Social identity theory suggests that an individual’s self-concept is based on his/her group membership (Turner & Oakes, 1986). The groups or organisations in which an individual holds membership are important sources of self-esteem (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Self-esteem could be distinguished between personal self-esteem and collective self-esteem. Personal self-esteem is a person’s overall evaluation of his/her own worthiness (Olsen, Breckler, & Wiggins, 2008), while collective self-esteem is an individual’s overall evaluation towards the social groups or work organisations (s)he belongs to (Bartel, 2001; Luhtanen & Crocker, 1992). In the context of organisations, personal self-esteem is often mentioned as organisation-based self-esteem (Pierce, Gardner, Cummings, & Dunham, 1989). Theoretically, collective self-esteem and organisation-based self-esteem could be highly interrelated. Organisations letting employees to highly evaluate their own worthiness (organisation-based self-esteem) will receive high evaluation from the employees too (collective self-esteem). However, although interrelated, collective self-esteem and organisation-based self-esteem are different constructs.Footnote 1 In this study, we used collective self-esteem rather than organisation-based self-esteem because CSR is expected to increase a firm’s reputation and status (Gardberg & Fombrun, 2006; Godfrey, 2005) which further affects the employees’ evaluation of the firm.

Perceived CSR and collective self-esteem

We first posit that employees’ perceived CSR increases their collective self-esteem. Collective self-esteem is defined as the degree to which an individual positively evaluates his or her social group or work organisation (Bartel, 2001; Luhtanen & Crocker, 1991, 1992). Such evaluation includes his or her evaluation of the group or organisation as a whole, as well as his or her perceptions of others’ evaluations of the group or organisation (Dutton & Dukerich, 1991; Luhtanen & Crocker, 1991). Social identity theory suggests that employees are self-esteem seekers (Hogg & Turner, 1987), and the organisations they belong to are important sources of their self-esteem (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Employees can maintain or even increase their self-esteem when their firms enjoy a high social status or have a favourable social reputation (Dutton & Dukerich, 1991; Hogg & Abrams, 1988; Luhtanen & Crocker, 1992).

CSR is a firm’s actions aiming to improve social or environmental situations (Aguilera et al., 2007; Davis, 1973). It is widely recognised as an effective instrument for firms to build favourable social reputation (Brammer, Millington, & Pavelin, 2006; Fombrun & Shanley, 1990; Godfrey, 2005), to increase social status and to differentiate themselves from the competitors (Gardberg & Fombrun, 2006; Porter & Kramer, 2002). As a result, CSR will lead employees to evaluate more positively towards, feel more proud of and satisfy more with their firms (Brammer et al., 2007; Valentine & Fleischman, 2008). In addition, social image or reputation is defined by others. A firm’s favourable social image or reputation suggests positive evaluations of the firm from external stakeholders (Fombrun, 1996). Since people tend to evaluate both the organisations and themselves through outsiders’ perceptions of their organisations’ image or reputation (Dutton & Dukerich, 1991), we believe CSR is going to increase employees’ positive evaluation of their firms by positively affecting their perceptions of others’ evaluations of the firms.

To sum up, a firm’s CSR not only leads employees to positively evaluate, and feel proud of, their firm (Brammer et al., 2007; Valentine & Fleischman, 2008), but also lets employees to perceive that external stakeholders will evaluate their firm positively (Brammer et al., 2006; Fombrun, 1996). Both the self-perceived and others-evaluated firm’s favourable image and reputation will help employees build collective self-esteem. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 1: Perceived CSR is positively related to collective self-esteem.

Effect of perceived CSR on work engagement via self-esteem

Work engagement is ‘a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigour, dedication, and absorption’ (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004: 295). Engaged employees are fully connected with their work roles physically, cognitively and emotionally (Kahn, 1990). They are willing to focus their energy on organisational goals (Macey et al., 2009) and are even proud of doing so (Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá, & Bakker, 2002). Engaged employees are willing to persist in the face of difficulties and are reluctant to detach themselves from work (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004).

Both job resources and personal resources are important drivers of work engagement (see Bakker, 2011 for an overview). Job resources are the physical, social or organisational aspects of the job that foster both employees’ personal growth and the willingness to dedicate their effort to work tasks (Bakker, 2011; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004), while personal resources are positive self-evaluations of one’s ability to successfully control or accomplish some type of work (Hobfoll, Johnson, Ennis, & Jackson, 2003). In particular, self-esteem, a person’s subjective emotional evaluation of his or her own worth, should act as an important predictor of work engagement (Bakker, 2011; Xanthopoulou et al., 2009).

The extant literature suggests that self-esteem has a positive effect on work engagement (Albrecht, 2010; Bakker, 2011). Although previous studies have not particularly focused on collective self-esteem, the logic underlying general self-esteem and work engagement can be extended to collective self-esteem. Collective self-esteem, or the act of making employees feel proud of joining and working for their firms (Brown & Dacin, 1997; Turban & Greening, 1997), constitutes an important personal resource which can motivate employees to become more engaged in work tasks (Xanthopoulou et al., 2009). Combining the effect of collective self-esteem on work engagement and our hypothesis 1 which suggests that perceived CSR enhances employees’ collective self-esteem, we therefore argue that CSR increases employees’ work engagement through collective self-esteem. Thus, we propose the following two hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis 2a: Perceived CSR is positively related to employees’ work engagement.

-

Hypothesis 2b: Collective self-esteem mediates the positive relationship between perceived CSR and employees’ work engagement.

The moderating role of concern for face

Although CSR is expected to enhance the collective self-esteem of employees, we further propose that this effect may vary with the employees’ concern for face. For employees who concern more for face, CSR may have a greater effect on their collective self-esteem than for those who concern less for face. In other words, we expect the positive effect of CSR on collective self-esteem to be moderated by employees’ concern for face in such a way that concern for face amplifies the positive effect of CSR on collective self-esteem.

Face, which is based on the need of human beings for social acceptance, is a general social concept existing in almost all cultures (Brown & Levinson, 1987; Hwang, Francesco, & Kessler, 2003). Face is defined as ‘the positive social value a person effectively claims for himself by the line others assume he has taken during a particular contact’ (Goffman, 1967: 5). In Confucian cultures, face is taken as an individual’s contingent self-esteem (Ng, 2001). Although almost everyone concerns for face, significant differences are reported among individuals both across cultures (Hwang et al., 2003; Wong & Ahuvia, 1998) and within the same culture (Bao et al., 2003; White et al., 2004). For employees who concern more for face, they should be more sensitive to and place more value on CSR because it enhances their socially favourable image in the eyes of outsiders (Adler & Snibbe, 2003; Goodman, Adler, Kawachi, Frazier, Huang, & Colditz, 2001; Twenge & Campbell, 2002). As a result, perceived CSR has a greater effect on their collective self-esteem than on those who concern less for face. In contrast, employees who concern less for face should be more likely to discount the effect of CSR on their collective self-esteem or face. We therefore propose the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 3: Perceived CSR has a more positive effect on collective self-esteem for employees who concern more for face than for those who concern less for face.

Combining our hypothesis 2b about the mediating effect of collective self-esteem and hypothesis 3 about the moderating effect of concern for face, we therefore propose a moderated mediation model: the indirect effect of CSR on work engagement through collective self-esteem is moderated by concern for face.

-

Hypothesis 4: The indirect effect of perceived CSR on work engagement through collective self-esteem is greater for employees who concern more for face.

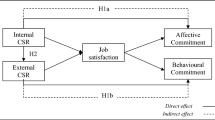

Figure 1 summarises our conceptual model.

Method

Data collection

To test the proposed model, we conducted two waves of questionnaire surveys with 240 employees in six companies in Wuhan, China: four information technology (IT) companies, one construction company and one real estate company.Footnote 2 Because the constructs used in this study were originally developed in English, we invited three independent bilingual translators to first translate English to Chinese and then reverse-translate from Chinese to English to ensure the equivalency and accuracy of meanings (Brislin, 1980).

Data were collected at two points in time with an interval of about two weeks. At time 1, we distributed a questionnaire to evaluate employees’ perceived CSR and their demographic characteristics. About two weeks later, we conducted a second round of survey towards the same respondents to measure their concern for face, collective self-esteem and work engagement. Among the 240 respondents that we sent the questionnaire to at time 1, 217 of them fully completed our second round survey, yielding a response rate of 90.4%. The demographic characteristics of the respondents are reported in Table 1.

Measures

Dependent variable: Work engagement

Work engagement was measured by the 9-item (UWES-9) scale developed by Schaufeli and his colleagues (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2003; Schaufeli, Bakker, & Salanova, 2006). This scale has been widely used in different cultural contexts (Balducci, Fraccaroli, & Schaufeli, 2010) and has high reliability (Cronbach’s α varies between .85 and .92) in ten European countries (Schaufeli et al., 2006). Self-rated responses were on a 7-point scale from 1 (‘Never’) to 7 (‘Always’). Sample questions include ‘At my work, I feel bursting with energy’, ‘I am enthusiastic about my job’, ‘My job inspires’ and ‘I am immersed in my job’. The coefficient alpha of work engagement in our study was .933, and all nine items were loaded into a single factor, which explained 66.266% of the total variance in the items. The smallest loading was .753 (average loading = .813).

Independent variable: Perceived CSR

To date, there is no consistent and reliable instrument to measure CSR due to diverse definitions from different scholars (Akremi, Gond, Swaen, De Roeck, & Igalens, 2016). Some researchers have used the Kinder, Lydenberg, Domini and Co. (KLD) ratings (Barnett & Salomon, 2006; Turban & Greening, 1997), while others developed self-rating scales based on Carroll’s (1979) pyramid (e.g. Maignan & Ferrell, 2000; Zhang, Fan, & Zhu, 2014) or stakeholder view (Turker, 2006), to measure CSR, CSP or ‘corporate citizenship’. In this study, we adopted Rego, Leal, and e Cunha’s (2011) scale because it integrated both Carroll’s (1979) CSR pyramid and the stakeholder view (Freeman, 1984), but we dropped the items addressing the interests of owners to keep in line with the social view of CSR (Aguilera et al., 2007; Davis, 1973; McWilliams & Siegel, 2001).Footnote 3 Although there is inconsistent regarding whether or not abiding laws and addressing the interests of customers should be treated as components of CSR, we followed prior studies (Decker, 2004; Maignan & Ferrell, 2000; Turker, 2009) and kept them in our measure of CSR, given customers’ rights are not protected well and law-breaking behaviours are rampant in transition China where shifting institutions (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012) and tentative legal enforcement (North, 1990) make these easy to happen. Nevertheless, we conducted a post hoc robustness check by excluding these two components from the measure of CSR and found the same results as keeping them. All items were measured on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (‘strongly disagree’) to 5 (‘strongly agree’). The original scale has high reliability (Cronbach’s α for all dimensions of CSR is above .90 except the dimension for owners). In our study, Cronbach’s alpha for the six dimensions of CSR (CSR-customer, CSR-employee, CSR-community, CSR-environment, CSR-legal and CSR-ethic) was .890, .844, .874, .920, .904 and .865, respectively. Validity tests showed that all items for the above six CSR dimensions could load onto a single factor which explained 69.73, 57.101, 61.767, 71.442, 68.38 and 60.509% of the variance, respectively, and correspondingly, the smallest loading was .793 (average loading = .834), .668 (average loading = .754), .725 (average loading = .786), .814 (average loading = .845), .705 (average loading = .825) and .677 (average loading = .776). Further validity tests suggested that the six dimensions of CSR could load onto a higher-order factor (only one eigenvalue is greater than 1.0, which explained 67.823% of variance, and all the loadings are equal to .761 or above). In addition, we conducted exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using the method of principal component analysis (with varimax rotation) to all items consisting of CSR. We found each item loaded on its expected factor with the smallest loading larger than .5 and no cross-loading exceeded .4, suggesting good convergence. We computed the average score of the six dimensions to assess the overall CSR.

Mediator: Collective self-esteem

We adopted a 3-item private collective self-esteem scale of Luhtanen and Crocker (1992) to measure employees’ collective self-esteem.Footnote 4 Sample questions were ‘I feel good about working for [company]’, ‘I often regret that I work for [company] (reverse item)’ and ‘Overall, I often feel that working for [company] is not worthwhile (reverse item)’. All items were measured on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (‘strongly disagree’) to 5 (‘strongly agree’). The original scale has high reliability (Cronbach’s α > .82). In our study, Cronbach’s α was .855. The validity test showed that four items were loaded onto a single factor, which explained 78.092% of the total variance in the items. The smallest loading was .820 (average loading = .883).

Moderator: Concern for face

Concern for face was measured by the original 8-item scale developed by Chan, Wan, and Sin (2009). Although Chan et al. (2009) suggest that only six items could be loaded onto the same single factor (Cronbach’s α is about .90), we still adopted the original 8-item scale because prior studies suggest that the additional two items could be integrated with other six items (Cocroft & Ting-Toomey, 1994; White et al., 2004). Self-rated responses were on a 5-point scale from 1 (‘strongly disagree’) to 5 (‘strongly agree’). Sample questions were ‘I care about praise and criticism from others’, ‘I care about others’ attitudes toward me’ and ‘I hate being taken lightly’. The coefficient alpha was .842. The validity test showed that all eight items loaded onto a single factor, which explained 48.873% of the total variance in the items. The smallest loading was .563 (average loading = .696).

Common method bias issue

In this study, our data came from the same group of respondents. The use of self-report data may be subject to common method bias (CMB) (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, & Podsakoff, 2012). To reduce the possibility of CMB, we had taken several procedural measures. First, we used existing scales and tried to keep the questions simple and specific to avoid ambiguity which is regarded as a main source of CMB (Zhang et al., 2014). Second, we conducted two waves of survey to separate questions concerning the independent variables (i.e. employees’ perceived CSR) from other variables. This design also reduced the possibility that respondents might speculate about the purpose of the survey. Third, the survey was anonymous, encouraging respondents to answer questions honestly. All of these steps help to reduce CMB (Podsakoff et al., 2012). In addition, the analysis involved a complicated regression model with a moderation effect, which is less likely to be affected by CMB (Podsakoff et al., 2012; Siemsen, Roth, & Oliveira, 2010). Finally, we used Harman’s single-factor test to check the CMB problem (Podsakoff et al., 2012). The items loaded onto four factors with the largest factor only explaining less than 41.4% of the variance. The results suggest that CMB is not a serious concern in this study.

Analysis and results

Confirmatory factor analysis

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to confirm the hypothesized four-factor structure of perceived CSR, collective self-esteem, work engagement and concern for face. Considering the constructs in our model contain a great number of indicators that may undermine model fit, we employed a parcelling technique (Little, Cunningham, Shahar, & Widaman, 2002). A parcelling approach is reasonable because our primary interest is the interrelations of our constructs rather than that of items within constructs (Little, Rhemtulla, Gibson, & Schoemann, 2013). We created parcels of two to three items for all scales except perceived CSR. For perceived CSR, parcels were created along with the six dimensions of CSR (six dimensions represent six parcels). For work engagement and concern for face, parcels were created using an item-to-construct balance technique, where the highest loading items were paired with the lowest loading items to create parcels (Little et al., 2002). Model fit was then evaluated on the basis of the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), root mean square residual (RMR), goodness-of-fit index (GFI), normed fit index (NFI) and the comparative fit index (CFI).

The hypothesized four-factor model demonstrated good fit to the data (χ 2 = 142.876, df = 71, p < .001, CFI = .972, GFI = .915, NFI = .946, RMSEA = .068; RMR = .033). This four-factor model fit the data better than a three-factor model grouping perceived CSR and collective self-esteem (χ 2 = 493.254, df = 74, p < .001, CFI = .836, GFI = .731, NFI = .814, RMSEA = .162; RMR = .079), or grouping collective self-esteem and work engagement (χ 2 = 457.615, df = 74, p < .001, CFI = .850, GFI = .763, NFI = .827, RMSEA = .155; RMR = .066). This four-factor model also fit the data better than a two-factor model grouping perceived CSR, collective self-esteem and work engagement (χ 2 = 1018.686, df = 76, p < .001, CFI = .631, GFI = .515, NFI = .615, RMSEA = .240; RMR = .084), and a one-factor model grouping all four constructs (χ 2 = 1222.485, df = 77, p < .001, CFI = .552, GFI = .490, NFI = .538, RMSEA = .262; RMR = .086).

Descriptive statistics and correlations

Table 2 shows the descriptive statistics and correlation matrix of the variables. The results demonstrate that both perceived CSR and collective self-esteem are significantly correlated with work engagement, and perceived CSR is also significantly correlated with collective self-esteem. Perceived CSR and concern for face are significantly related to each other. To minimise the potential multicollinearity issue, we mean-centred the independent variable and the moderator, then created interaction terms by multiplying the two mean-centred variables (Aiken & West, 1991). The variance inflation factors (VIFs) in the following regression analysis show that the largest VIF in all models is 1.322, falling below the threshold of 10, and suggesting that multicollinearity is not a concern in this study.

Testing main and mediation effect

In this study, we used PROCESS for SPSS (17.0 version) developed by Hayes (2013) to test our arguments. We selected 95% confidence for bias-corrected boostrap confidence intervals (CIs) with 5000 bootstrap samples estimate. We first chose model 4 (see the template of PROCESS) to test the direct effect of perceived CSR on work engagement and the mediation effect of collective self-esteem. Then, we chose model 7 to test the moderation effect of concern for face.

The results by using model 4 of PROCESS to test the main and mediation effect are summarised in Table 3. From Table 3, we see that perceived CSR has a positive effect on collective self-esteem, and this effect is significant because 95% CI does not contain zero (0) (β = .563, SE = .092, 95% CI [.382, .745], see model (1) in Table 3). As a result, hypothesis 1 is supported.

In addition, perceived CSR has a positive effect on work engagement, and this effect is significant since 95% CI does not contain zero (0) (β = 1.097, SE = .132, 95% CI [.836, 1.357], see model (2)). Thus, hypothesis 2a is supported.

Finally, from model (3) in Table 3, we also see that collective self-esteem has a significant and positive effect on work engagement (β = .497, SE = .092, 95% CI [.317, .678]). In this model, the effect of perceived CSR on work engagement keeps significant and positive (β = .816, SE = .134, 95% CI [.551, 1.081]). Considering perceived CSR has also a significant and positive effect on collective self-esteem as we reported earlier, we suggest that collective self-esteem partially mediates the relationship between perceived CSR and work engagement. As a result, hypothesis 2b is supported.

Testing moderation effect

To test the moderation effect of concern for face, we used model 7 of PROCESS. The results for the moderation effect of concern for face on the relationship between perceived CSR and collective self-esteem are firstly reported in Table 4. From Table 4, we see clearly that the interaction term between perceived CSR and concern for face is positive and significant as 95% CI does not contain zero (0) (β = .408, SE = .174, 95% CI [.064, .752]). Simple slopes (see the first stage in Table 5), plotted in Fig. 2 suggest that, for employees who concern more for face, CSR is more positively correlated with collective self-esteem (γ = .715, p < .01) than for those who concern less for face (γ = .301, p < .05). The results are consistent with our expectations. Thus, hypothesis 3 is supported.

In addition, the moderating effect of concern for face on the relationship between perceived CSR and work engagement via collective self-esteem is also significant (Index = .203, SE = .094, 95% CI [.064, .434]). Table 5 reports the mediation effect at different levels of concern for face.Footnote 5 For low concern for face (i.e. one standard deviation below the mean, that is, − .508), the first stage of the indirect effect equals .301, the second stage of the indirect effect is .497, and the direct effect is .816, and the indirect effect for low concern for face (equals the product of the first and second stages, or .301 × .497) is .15, and the total effect (equals the sum of the direct and indirect effects, or .816 + .150) is .966. For high concern for face (i.e. one standard deviation above the mean, that is, .508), the first stage of the indirect effect is .715, the second stage is still .497, and the direct effect is still .816. The indirect effect is .356, and the total effect is 1.172.

Differences in the effects for low and high concern for face suggest that the first stage of the indirect effect was stronger for high concern for face (.715 − .301 = .414, p < .01), and this difference contributes to a significantly stronger indirect effect for high concern for face (.356 − .150 = .206, p < .05). In addition, the total effect is also stronger for high concern for face (1.172 − .966 = .206, p < .05).

Post hoc analysis

Scholars have suggested that given its multidimensional nature (Husted, 2000; Wood, 1991), CSR may convey different things to employees. As a result, it would be both interesting and meaningful to look into the different dimensions of CSR and their effects on employees’ attitudes and behaviour. We therefore conducted a post hoc analysis to examine the effect of each of the six dimensions of CSR on work engagement as well as the mediation effect of collective self-esteem and the moderation effect of concern for face.

The results indicate that all six dimensions of CSR, including CSR-customer, CSR-employee, CSR-community, CSR-environment, CSR-legal and CSR-ethic, have a significant direct effect on work engagement. CSR-employee seems to be the most critical dimension of CSR in motivating employees’ work engagement, followed by CSR-ethic and CSR-environment. The mediating effect of collective self-esteem is also supported for all CSR dimensions. Concern for face positively moderates the relationship between collective self-esteem and four CSR dimensions: CSR-employee, CSR-community, CSR-environment and CSR-ethic. It does not influence the relationship between collective self-esteem and the other two CSR dimensions: CSR-customer and CSR-legal.

Discussion

In this study, we explored the relationship between employees’ perceived CSR and their work engagement, as well as the mediating role of collective self-esteem and the moderating effect of concern for face. We found a positive relationship between perceived CSR and work engagement which is partially mediated by collective self-esteem. In addition, we found that employees who concern more for face seem to benefit more from CSR by increasing their collective self-esteem and work engagement more significantly. This study has critical theoretical and practical implications.

Theoretical implications

This study contributes to the CSR, self-esteem and work engagement literature in the following three respects.

First, previous studies have examined the effect of CSR on some employees’ attitudes and behaviours towards their firms, such as organisational commitment, organisational identification and citizenship behaviour (Abdullah & Rashid, 2012; Aguilera et al., 2006; Brammer et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2010; Lin, Lyau, Tsai, Chen, & Chiu, 2010). Work engagement as an important behavioural predictor of job performance, and more importantly, organisational productivity only received limited attention (Caligiuri et al., 2013; Esmaeelinezhad et al., 2015; Glavas, 2016). Gallup (2013) estimated that only 13% of employees are engaged worldwide and the economic loss due to the decreased productivity of disengaged employees is about USD 450 to 550 billion annually in USA alone. As a result, it is meaningful to explore the effect of CSR on employees’ work engagement. We extend the studies concerning about the influences of perceived CSR by exploring its effect on employees’ work engagement in the largest transition economy, China.

Second, through identifying collective self-esteem as an important underlying mechanism linking perceived CSR to work engagement, we respond to a recent call in the organisational literature to investigate the underlying mechanisms linking CSR to individual-level outcomes (Aguinis & Glavas, 2012; Jones et al., 2014). Previous studies have generally suggested that employees support CSR, and CSR benefits employees and their organisations. However, the underlying reasons why organisations’ actions in the external community can motivate their internal stakeholders-employees are still to be identified. Some scholars have suggested that CSR may enhance employees’ self-esteem because it helps the firm to build a favourable image and reputation, and enhanced self-esteem further motivates employees to reciprocate (Riordan, Gatewood, & Bill, 1997; Tyler & Blader, 2000). Nonetheless, to date, there is no empirical evidence to support this argument. Meanwhile, although the literature on work engagement has noted that as one form of personal resources, personal self-esteem can affect work engagement (Albrecht, 2010; Xanthopoulou et al., 2009); it is not clear whether or not collective self-esteem has a similar effect. This study contributes to the self-esteem literature by identifying collective self-esteem as one of the mechanisms linking CSR to work engagement.

Finally, this study found that employees’ concern for face moderates the relationship between CSR and collective self-esteem and additionally moderates the indirect effect of CSR on work engagement through collective self-esteem. The effect of perceived CSR on individual employees’ attitudes and behaviours may not be universal for all employees within the same organisation. Previous studies have not investigated what kind of employees is more likely to favour and respond to CSR than others. As a result, firms do not know the limiting conditions when they use CSR to motivate employees. Our study found that employees who concern more for face are more likely to value CSR than those who concern less for face. These employees’ collective self-esteem is therefore more likely to be enhanced by CSR, and they are more likely to be motivated by CSR to become engaged in their jobs. These findings have significant implications for future studies examining the different responses among employees towards CSR.

Practical implications

This study also has important practical implications. First, we found CSR has a positive effect on employees, motivating them to engage more deeply in their work tasks (work engagement). Combining this finding with the well-acknowledged positive effect of work engagement on organisational productivity, we can claim that engaging in CSR activities eventually benefits the firms. More important, CSR might contribute to employees’ well-being by making their job more meaningful, increasing their job satisfaction, offering them a sense of accomplishment and cultivating their positive attitude towards others and the society. As employees’ well-being becoming a main purpose of business activities and an important instrument for sustainable business performance, CSR’s role should not be undervalued.

In addition, we find that employees support CSR because CSR can increase their self-esteem. Firms can use CSR to increase their social status or reputation which further helps their employees build collective self-esteem. If employees feel proud of working for a firm (Brown & Dacin, 1997; Turban & Greening, 1997), they will invest their energy in work tasks. Our findings suggest that firms should conduct CSR activities that are highly visible to their employees or that have high possibility for the firms to increase their social status and reputation.

Finally, firms with employees who have higher level of concern for face should be in a better position to use CSR to enhance employees’ collective self-esteem and ultimately their work engagement. However, our post hoc analysis revealed that CSR-customer and CSR-legal tend to be basic social responsibilities of firms. They are preconditions and act as hygiene factors, but they are less likely to motivate employees who concern for face than other four dimensions of CSR (i.e. CSR-employees, CSR-community, CSR-environment and CSR-ethic) that are more likely to be motivation factors.

Limitations and future study directions

This study has also limitations. One of the major limitations is the possibility of common method bias (CMB). We used self-reported data from the same respondents to measure all variables (perceived CSR, concern for face, collective self-esteem and work engagement), believing these variables in our study could be consistently rated by employees themselves (Zhang et al., 2014). Although we have taken several measures to reduce the potential CMB and at the same time, our moderated mediation model is less likely to be affected by it (Podsakoff et al., 2012), we cannot rule out CMB completely. In addition, given the self-reported nature of work engagement, social desirability response bias may contaminate the validity of our findings. Future studies could develop a new scale and measure work engagement from the supervisors’ perspective (asking supervisors to assess the work engagement of their subordinates). In addition, future studies could consider using supervisor-rated or customer-rated data on job performance to explore the influence of CSR.

A final potential limitation in the current research is that we only considered the moderating role of individual employees’ concern for face and the mediating role of their collective self-esteem in the relationship between employees’ perceived CSR and work engagement. Future research might consider the influence of peers and supervisor in delineating this process. The reactions of supervisor and peers towards CSR may influence the effect of the focal employees’ perceived CSR on their collective self-esteem, which may further influence employees’ work behaviour. In addition, scholars have suggested that CSR may lead employees to find greater meaningfulness at work and thus motivates them to be more engaged in work (e.g. Glavas, 2012; Rosso, Dekas, & Wrzesniewski, 2010). Future studies could empirically test the mediating role of work meaningfulness in the relationship between CSR and work engagement.

Conclusion

As CSR has become a dominant concept in macro organisational behaviour and has aroused quite an interest in the literature (Bondy & Starkey, 2014; Muthuri, Matten, & Moon, 2009), the effect of CSR on employees’ work behaviour needs more exploration and clarification. From the social identity perspective, we found that employees’ perceived CSR enhances their collective self-esteem, which further improves their work engagement. Meanwhile, employees’ concern for face makes the effect of CSR more salient. We expect our effort to evoke more studies on this important topic.

Notes

We conducted a post hoc validation to the constructs of collective self-esteem and organisation-based self-esteem and found they are distinct. Using additionally collected data (sample = 128), we found these two constructs are significantly correlated (r = 0.332, p < 0.01). CFA suggests that a two-factor model fits the data better (χ 2 = 104.576, df = 64, p < .01, CFI = .958, GFI = .894, NFI = .900, RMSEA = .071; RMR = .024) than a one-factor model (χ 2 = 386.735, df = 65, p < .01, CFI = .666, GFI = .708, NFI = .629, RMSEA = .197; RMR = .096).

Although our data comes from three industries, there is no reason to suspect that employees within different industries will have different responses towards their perceived CSR. We did a post hoc analysis by introducing three industry dummies (put 2 into the regression model) and found they were not significant. We also selected only IT industry (N = 145) to repeat our analysis; the results were consistent with our original results.

Our post hoc analysis suggests that including the CSR-owner dimension in measuring overall CSR produced similar results. In addition, we used the 9-item Zhang et al. (2014) scale of CSP to measure perceived CSR and conducted a robustness check. The results are also consistent with our original results.

References

Abdullah, M. H., & Rashid, N. R. N. A. (2012). The implementation of corporate social responsibility (CSR) programs and its impact on employee organizational citizenship behavior. International Journal of Business and Commerce, 2(1), 67–75.

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. (2012). Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. New York: Crown Business.

Adler, N. E., & Snibbe, A. C. (2003). The role of psychosocial processes in explaining the gradient between socioeconomic status and health. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(4), 119–123.

Aguilera, R., Rupp, D. E., Ganapathi, J., & Williams, C. A. (2006). Justice and social responsibility: A social exchange model. Berlin: Paper presented at the Society for Industrial/Organizational Psychology Annual Meeting.

Aguilera, R. V., Rupp, D., Williams, C. A., & Ganapathi, J. (2007). Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multi-level theory of social change in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32, 836–863.

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 38, 932–968.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage.

Akremi, A. E., Gond, J. P., Swaen, V., De Roeck, K., & Igalens, J. (2016). How do employees perceive corporate responsibility? Development and validation of a multidimensional corporate stakeholder responsibility scale. Journal of Management, 35(7), 1141–1168.

Albrecht, S. L. (Ed.). (2010). Handbook of employee engagement: Perspectives, issues, research and practice. Glos: Edward Elgar.

Ali, I., Rehman, K. U., Ali, S. I., Yousaf, J., & Zia, M. (2010). Corporate social responsibility influences employees commitment and organizational performance. African Journal of Business Management, 4(12), 2796–2801.

Bakker, A. B. (2011). An evidence-based model of work engagement. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(4), 265–269.

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Verbeke, W. (2004). Using the job demands-resources model to predict burnout and performance. Human Resource Management, 43(1), 83–104.

Balducci, C., Fraccaroli, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2010). Psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES-9). European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26(2), 143–149.

Bao, Y., Zhou, K. Z., & Su, C. (2003). Face consciousness and risk aversion: Do they affect consumer decision-making? Psychology & Marketing, 20(8), 733–755.

Barnett, M. L., & Salomon, R. M. (2006). Beyond dichotomy: The curvilinear relationship between social responsibility and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 27, 1101–1122.

Bartel, C. A. (2001). Social comparisons in boundary-spanning work: Effects of community outreach on members’ organizational identity and identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46(3), 379–414.

Bondy, K., & Starkey, K. (2014). The dilemmas of internationalization: Corporate social responsibility in the multinational corporation. British Journal of Management, 25, 4–22.

Brammer, S., Millington, A., & Pavelin, S. (2006). Is philanthropy strategic? An analysis of the management of charitable giving in large UK companies. Business Ethics: A European Review, 15(3), 234–245.

Brammer, S., Millington, A., & Rayton, B. (2007). The contribution of corporate social responsibility to organizational commitment. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(10), 1701–1719.

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. Handbook of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 2(2), 349–444.

Brown, P., & Levinson, S. C. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, T. J., & Dacin, P. A. (1997). The company and the product: Corporate association and consumer product responses. Journal of Marketing, 61, 68–84.

Caligiuri, P., Mencin, A., & Jiang, K. (2013). Win-win-win: The influence of company-sponsored volunteerism programs on employees, NGOs, and business units. Personnel Psychology, 66, 825–860.

Carroll, A. (1999). Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Business and Society, 38(3), 268–295.

Carroll, A. B. (1979). A three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance. Academy of Management Review, 4(4), 497–505.

Chan, H., Wan, L. C., & Sin, L. Y. M. (2009). The contrasting effects of culture on consumer tolerance: Interpersonal face and impersonal fate. Journal of Consumer Research, 36, 292–304.

Cocroft, B. K., & Ting-Toomey, S. (1994). Facework in Japan and the United States. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 18(4), 469–506.

Davis, K. (1973). The case for and against business assumptions of social responsibilities. Academy of Management Journal, 16, 312–322.

Decker, O. S. (2004). Corporate social responsibility and structural change in financial services. Managerial Auditing Journal, 19(6), 712–728.

Dutton, J. E., & Dukerich, J. M. (1991). Keeping an eye on the mirror: Image and identity in organizational adaptation. Academy of Management Journal, 34(3), 517–554.

Edwards, J. R., & Lambert, L. S. (2007). Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychological Methods, 12(1), 1–22.

Eells, R., & Walton, C. (1974). Conceptual Foundations of Business (3rd ed.). Burr Ridge: Irwin.

Esmaeelinezhad, O., Boerhannoeddin, A. B., & Singaravelloo, K. (2015). The effects of corporate social responsibility dimensions on employee engagement in Iran. International Journal of Academic Research in Business & Social Sciences, 5(3), 15–22.

Fombrun, C. (1996). Reputation: Realizing value for the corporate image. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Fombrun, C., & Shanley, M. (1990). What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal, 33(2), 233–258.

Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Boston: Pitman.

Gallup Consulting. 2013. State of the Global Workplace: Employee Engagement Insights for Business Leaders Worldwide. Washington, DC: Gallup.

Gao, J. H. (2014). Relating corporate social responsibility to employee engagement. International Journal of Asian Business & Information Management, 5(2), 12–22.

Gardberg, N. A., & Fombrun, C. J. (2006). Corporate citizenship: Creating intangible assets across institutional environments. Academy of Management Review, 34, 329–346.

Glavas, A. (2012). Employee engagement and sustainability: A model for implementing meaningfulness at and in work. Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 46, 13–29.

Glavas, A. (2016). Corporate social responsibility and employee engagement: Enabling employees to employ more of their whole selves at work. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1–10.

Glavas, A., & Kelley, K. (2014). The effects of perceived corporate social responsibility on employee attitudes. Business Ethics Quarterly, 24, 165–202.

Godfrey, P. C. (2005). The relationship between corporate philanthropy and shareholder wealth: A risk management perspective. Academy of Management Review, 30, 777–798.

Goffman, E. (1967). Interaction ritual: Essays on face-to-face interaction. New York: Pantheon Books.

Goodman, E., Adler, N. E., Kawachi, I., Frazier, A. L., Huang, B., & Colditz, G. A. (2001). Adolescents’ perceptions of social status: Development and evaluation of a new indicator. Pediatrics, 108(2), e31.

Griffin, J. J., & Mahon, J. F. (1997). The corporate social performance and corporate financial performance debate: Twenty-five years of incomparable research. Business and Society, 36(1), 5–31.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. New York: The Guilford Press.

Hobfoll, S. E., Johnson, R. J., Ennis, N., & Jackson, A. P. (2003). Resource loss, resource gain, and emotional outcomes among inner city women. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(3), 632–643.

Hogg, M., & Turner, J. (1987). Intergroup behaviour, selfstereotyping and the salience of social categories. British Journal of Social Psychology, 26, 325–340.

Hogg, M. A., & Abrams, D. (1988). Social identifications: A social psychology of intergroup relations and group processes. Abingdon: Taylor & Frances/Routledge.

Husted, B. W. (2000). The impact of national culture on software piracy. Journal of Business Ethics, 26(3), 197–211.

Hwang, A., Francesco, A. M., & Kessler, E. (2003). The relationship between individualism-collectivism, face, and feedback and learning processes in Hong Kong, Singapore, and the United States. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 34(1), 72–91.

Hwang, K. (2006). Moral face and social face: Contingent self-esteem in Confucian society. International Journal of Psychology, 41(4), 276–281.

Jones, D. A. (2010). Does serving the community also serve the company? Using organizational identification and social exchange theories to understand employee responses to a volunteerism programme. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83, 857–878.

Jones, D. A., Willness, C. R., & Madey, S. (2014). Why are job seekers attracted by corporate social performance? Experimental and field tests of three signal-based mechanisms. Academy of Management Journal, 57, 383–404.

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), 692–724.

Kim, H. R., Lee, M., Lee, H. T., & Kim, N. M. (2010). Corporate social responsibility and employee–company identification. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(4), 557–569.

Lin, C. P. (2010). Modeling corporate citizenship, organizational trust, and work engagement based on attachment theory. Journal of Business Ethics, 94(4), 517–531.

Lin, C. P., Lyau, N. M., Tsai, Y. H., Chen, W. Y., & Chiu, C. K. (2010). Modeling corporate citizenship and its relationship with organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(3), 357–372.

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 151–173.

Little, T. D., Rhemtulla, M., Gibson, K., & Schoemann, A. M. (2013). Why the items versus parcels controversy needn’t be one. Psychological Methods, 18(3), 285–300.

Luhtanen, R., & Crocker, J. (1991). Self-esteem and intergroup comparisons: Toward a theory of collective self-esteem. In J. Suls & T. A. Wills (Eds.), Social comparison: Contemporary theory and research (pp. 211–234). Hillsdale: Erlbaurn.

Luhtanen, R., & Crocker, J. (1992). A collective self-esteem scale: Self-evaluation of one’s social identity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 18(3), 302–318.

Macey, W., Schneider, B., Barbera, K., & Young, S. A. (2009). Employee engagement: Tools for analysis, practice, and competitive advantage. London: Blackwell.

Maignan, I., & Ferrell, O. C. (2000). Measuring corporate citizenship in two countries: The case of the United States and France. Journal of Business Ethics, 23(3), 283–297.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2001). Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Academy of Management Review, 26(1), 117–127.

Muthuri, J. N., Matten, D., & Moon, J. (2009). Employee volunteering and social capital: Contributions to corporate social responsibility. British Journal of Management, 20, 75–89.

Ng, A. K. (2001). Why Asians are less creative than Westerners. Singapore: Prentice-Hall.

North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Olsen, J. M., Breckler, S. J., & Wiggins, E. C. (2008). Social psychology alive (1st ed.). Ontario: Nelson.

Peloza, J. (2009). The challenge of measuring financial impacts from investments in corporate social performance. Journal of Management, 35(6), 1518–1541.

Pierce, J., Gardner, D., Cummings, L., & Dunham, R. (1989). Organisation-based self-esteem: Construct of definition, measurement and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 32(3), 633–648.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569.

Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2002). The competitive advantage of corporate philanthropy. Harvard Business Review, 80(12), 56–68.

Rego, A., Leal, S., & e Cunha, M. P. (2011). Rethinking the employees’ perceptions of corporate citizenship dimensionalization. Journal of Business Ethics, 104(2), 207–218.

Riordan, C. M., Gatewood, R. D., & Bill, J. B. (1997). Corporate image: Employee reactions and implications for managing corporate social performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 16, 401–412.

Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91–127.

Rupp, D. E., Shao, R., Thornton, M. A., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2013). Applicants’ and employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: The moderating effects of first-party justice perceptions and moral identity. Personnel Psychology, 66, 895–933.

Salanova, M., Agut, S., & Peiró, J. M. (2005). Linking organizational resources and work engagement to employee performance and customer loyalty: The mediating role of service climate. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 1217–1227.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2003). Test manual for the Utrecht work engagement scale. Unpublished manuscript. the Netherlands: Utrecht University Retrieved from http://www.schaufeli.com.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 293–315.

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire a cross-national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701–716.

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71–92.

Siemsen, E., Roth, A., & Oliveira, P. (2010). Common method bias in regression models with linear, quadratic, and interaction effects. Organizational Research Methods, 13(3), 456–476.

Story, J., & Neves, P. (2015). When corporate social responsibility (CSR) increases performance: Exploring the role of intrinsic and extrinsic CSR attribution. Business Ethics: A European Review, 24(2), 111–124.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations (pp. 33–47). Monterey: Brooks-Cole.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1985). The social identity theory of intergroup behaviour. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of Intergroup Relations (pp. 6–24). Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

Turban, D. B., & Greening, D. W. (1997). Corporate social performance and organizational attractiveness to prospective employees. Academy of Management Journal, 40(3), 658–673.

Turker, D. (2006). The impact of employee perception of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: A scale development study. Unpublished Master’s Dissertation, Dokuz Eylul University. (Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü İngilizce İşletme Anabilim Dalı Yüksek Lisans Tezi).

Turker, D. (2009). Measuring corporate social responsibility: A scale development study. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(4), 411–427.

Turner, J., & Oakes, P. (1986). The significance of the social identity concept for social psychology with reference to individualism, interactionism and social influence. British Journal of Social Psychology, 25(3), 237–252.

Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2002). Self-esteem and socioeconomic status: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6(1), 59–71.

Tyler, T. R., & Blader, S. (2000). Cooperation in groups: Procedural justice, social identity and behavioural engagement. New York: Psychology Press.

Valentine, S., & Fleischman, G. (2008). Ethics programs, perceived corporate social responsibility and job satisfaction. Journal of Business Ethics, 77, 159–172.

Waddock, S. (2004). Paeallel universes: Companies, academics and the progress of corporate citizenship. Business and Society Review, 109(1), 5–42.

White, J. B., Tynan, R., Galinsky, A. D., & Thompson, L. (2004). Face threat sensitivity in negotiation: Roadblock to agreement and joint gain. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 94(2), 102–124.

Wong, N. Y., & Ahuvia, A. C. (1998). Personal taste and family face: Luxury consumption in Confucian and Western societies. Psychology and Marketing, 15(5), 423–441.

Wood, D. J. (1991). Corporate social performance revisited. Academy of Management Review, 16(4), 691–718.

Xanthopoulou, D., Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2009). Work engagement and financial returns: A diary study on the role of job and personal resources. Journal of Organizational and Occupational Psychology, 82, 183–200.

Zhang, M., Fan, D., & Zhu, C. J. (2014). High-performance work systems, corporate social performance and employee outcomes: Exploring the missing links. Journal of Business Ethics, 120(3), 423–435.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the financial support of the ‘National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC)’ (No. 71372131).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, Y., Zhang, D. & Huo, Y. Corporate social responsibility and work engagement: testing a moderated mediation model. J Bus Psychol 33, 661–673 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-017-9517-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-017-9517-6