Abstract

An alternative conceptualization for job satisfaction, the most commonly measured variable in organizational, vocational, and work psychology literatures, is explored in 3 differing samples totaling 811 working adults. Eudaimonic, meaning-based job-related well-being (MJW) predicts job and life outcomes just as well as the more commonly measured hedonic, pleasure-based job satisfaction (JS), and MJW relates to outcomes above and beyond JS. MJW locates a new origin of job satisfaction in the person, in a life situation, in a community and social relations, rather than in the work organization. Our findings demonstrate that MJW is distinct from but related to JS and other job attitudes, and that facets of MJW exist that have been excluded from job satisfaction research, including satisfaction with the impacts of the job on family, life, and standard of living, how the job facilitates expression and development of the self, and sense of transcendent purpose through job role. These facets are important to individuals, the practice of management, organizational design, and society. MJW derives from the impact of jobs on workers’ larger worlds and on the fulfillment of their basic human needs from work. Thus, the causes of job satisfaction broaden from enjoyment of work in isolation, to its contextualized meaning and impact in workers’ lives. This is the first study in many decades, of which we are aware, to broaden the conceptualization of the origins of work attitudes beyond the confines of the workplace.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

I rise in the morning torn between a desire to improve (or save) the world and a desire to enjoy (or savor) the world. This makes it hard to plan the day.

(E.B. White, quoted in Shenker, 1969: 43)

This quote succinctly captures two primary meanings of being well: a “right” or meaningful life and a pleasure-filled or enjoyable life. In ancient philosophy, the former is called eudaimonic and the latter hedonic well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2001; Ryff, 1989; Waterman, 1993). In terms of jobs, eudaimonic, or meaning-based, job-related well-being could be characterized as satisfaction with the “why” or purposes of work in the context of a human life in social community, whereas hedonic, or pleasure-based, job-related well-being could be characterized as satisfaction with the “what” and “how” of doing the work in the work organization.

Job satisfaction is the most common conceptualization of job-related well-being in organizational, vocational, and work psychology research. As conceptualized and measured, it is widely acknowledged to capture hedonic job-related aspects—whether a job is “enjoyable in the present” (George & Jones, 1996, p. 320), and not explicitly eudaimonic aspects—the “sense of contribution and purpose that comes from working” (Dik, Duffy, & Eldridge, 2009, p. 629).

In 3 differing samples, totaling 811 working adults, we explore a eudaimonic conceptualization of job-related well-being. Our findings suggest that eudaimonic, meaning-based job-related well-being (MJW) predicts outcomes as well as hedonic, pleasure-based job satisfaction (JS), and that MJW relates to outcomes above and beyond JS. Our findings demonstrate that MJW is distinct from but related to JS and other job attitudes, and that facets of MJW exist that have been excluded from job satisfaction research to date, including satisfaction with the impacts of the job on family, life, and standard of living; how the job facilitates expression and development of the self; and sense of transcendent purpose through work role. These facets are important to the practice of management and organizational design, as well as to individuals and society.

How workers’ job-related well-being is conceptualized impacts the actions taken to improve it. If we see job-related well-being as deriving solely or primarily within the workplace, our attention for improving satisfaction will be narrowly focused on conditions at work or on fit in an individual’s job “choice.” Exploring whether jobs meet broader human needs for work in the context of holistic lives focuses attention on additional, eudaimonic factors that impact job satisfaction. These factors are especially important for an economy that serves humanity broadly. Broadening our focus on causes of job satisfaction shifts our attention to job design that facilitates workers’ family and civic lives and promotes equity and human dignity, as well as achieving organizational outcomes. Our exploratory research question is whether an alternative conceptualization—MJW—predicts outcomes as well as, or better than, JS as it is generally conceptualized and measured.

Meaning Matters

Models that explain JS suggest it is caused by characteristics of the person, the job, the fit between the two, or all three: person, environment, and fit (Dawis & Lofquist, 1984; Schleicher, Hansen, & Fox, 2011). However, “person” is generally conceptualized in a way that primarily reflects jobs, isolating elements or “pieces” of people thought to fit into jobs, such as abilities with tasks, or personal values with the organization’s values, rather than exploring whether jobs “fit into” or meet core needs of people (Budd, 2011; Weiss & Rupp, 2011).

If researchers continue to measure the same set of workplace-oriented, empirically derived facets, we will continue to find that only these elements are important, potentially causing misleading conclusions. For example, Cascio (2003) reports on a study by the National Research Council done in 1973 and repeated in 1996 asking respondents to rank five classic JS facets in order of importance. Because rank orderings were similar, it was concluded that Americans sought the same characteristics in jobs over two decades. However, each of these facets may have become less (or more) important over time while the rank ordering stayed the same. In addition, there could be facets of higher importance that relate to the meaning of work, such as the MJW facets we explore below, had respondents had the opportunity to rank them.

Job-Related Well-being

Job satisfaction is the most frequently used construct in organizational, vocational, and work psychology research, and often the only variable used to capture job-related well-being (Judge, Parker, Colbert, Heller, & Ilies, 2002). We have learned much from JS research, which is extensively reviewed elsewhere (e.g., Judge et al., 2002; Kinicki, McKee-Ryan, Schriesheim, & Carson, 2002; Schleicher et al., 2011); however, significant unexplored aspects still exist (Warr, 2007). These aspects may help, for example, to solve a long-standing research puzzle—that relationships between JS and organizational outcomes are “not as strong as originally thought” (Schleicher et al., 2011, p. 148). In addition to looking for moderators of the satisfaction-performance relationship, such as situational strength (see Bowling, Khazon, Meyer, & Burrus, 2015), solving this puzzle includes exploring what has been systematically left out of JS conceptualizations. As researchers have asked about JS in the titles of their articles, “Are all the parts there?” (see Rothausen, Gonzalez, & Griffin, 2009 and Scarpello & Campbell, 1983).

Critiques call for ongoing development of JS “in order to better understand a construct that has so far been examined in too narrow a manner” (Warr, 2007, p. 8). Lack of ongoing development of JS has been cited as a significant problem for research in organizational, vocational, and work psychology (Guion, 1992; Kinicki et al., 2002), where stagnation of fundamental research and increasing use of ad hoc scales were noted as long as 15 years ago (Judge et al., 2002). Since then, some additional exploration of basic issues in JS has been conducted (e.g., Fila, Paik, Griffeth, & Allen, 2014) though recent interest seems to be more in the direction of constructs such as engagement (Harter, Schmidt, & Hayes, 2002; Rich, LePine, & Crawford, 2010) and presenteeism (Prochaska, Evers, Johnson, Castle, Prochaska, Sears, Rula, & Pope, 2011). This may be in part because of extensive practitioner use of these constructs, in turn due to frustration with the limits of extant conceptualizations of JS (Frese, 2008). Academic development suggests that engagement and presenteeism are, at least in part, attempts to capture energy (or lack thereof) created by what jobs mean (or do not mean) to workers in the context of their larger lives (Prochaska et al., 2011; Rich et al., 2010).

Warr (2007, p. 6) notes that a job is “a … reflection, and … cause and effect, of a person’s place in society.” This claim of far-reaching and mutually interactive meanings for jobs and the whole lives of those who perform them echoes early thinking about JS, before solidification in organizational, vocational, and work psychology literatures of currently dominant hedonic conceptualizations and measures. For example, in his ground-breaking book on JS, Hoppock (1935, p. 5) recognized that understanding JS,

…is complicated by the…nature of satisfaction. Indeed there may be no such thing as job satisfaction independent of the other satisfactions in one’s life. Family relationships, health, relative social status in the community, and a multitude of other factors may be just as important as the job itself in determining…job satisfaction.

Jobs can fulfill (or not fulfill) basic human needs (some would say rights) for dignity in work, meaningful work, and some level of economic justice. Jobs also affect workers’ lives, and thus their worlds, fundamentally, as Hoppock implied. Therefore, key meanings of work spring from basic human needs from work, and from workers’ larger worlds, and these elements likely impact workers’ satisfaction related to their jobs. Several theoretical perspectives and empirical research streams suggest this. We briefly review three such research literatures below.

First, well-being and stress theories, such as the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory (Hobfoll, 1989) and Self-Determination Theory (SDT; Ryan & Deci, 2000), posit that individuals aim to build primary resources throughout life that make their lives meaningful and enjoyable (Griffin & Clarke, 2011). When people experience a surplus of these primary resources, they experience positive well-being; when they experience an inability to gain them, they experience stress or a lack of well-being (Hobfoll, 1989, p. 517). COR theory posits that human behavior is explained by attempts to build, protect, gain, or prevent the loss of primary resources, and SDT emphasizes the importance of individual customization of this endeavor.

Resources can be categorized as primary or secondary, where the latter are valued in and of themselves and because they contribute to the building, or prevention of loss, of primary resources (Griffin & Clarke, 2011). Several categorizations of primary resources exist (e.g., Hobfoll, 1989; Ryan & Deci, 2000; Ryff, 1989) but have in common a positive, meaningful self-concept, in meaningful connection to significant others, in communities. Secondary resources can include objects, relationships, conditions, or personal characteristics that serve as a means for attaining ultimate goals (Hobfoll, 1989). Viewed from these person-centered theories, a job is a secondary resource that serves the attainment of one or more primary resources.

Second, career and lifespan literatures generally put work into a set of domains within a life context, whereas organizational and management literatures tend to take a more transactional, economic exchange view of work (Budd, 2011; Dik et al., 2009; Lefkowitz, 2016). Life course literatures establish that individuals construct lives comprised of fundamental domains. Super (1990) described these domains, and similar domains are reflected in well-being research (e.g., Deci & Ryan, 2008), including job or work; social or family; financial or standard of living; leisure or recreation; physical, mental, and spiritual health; housing or community; and education. Most theories of the self and identity suggest that a person makes sense of self through participation in different roles across life domains such as work, family, spirituality, health, community, and recreation (e.g., Deci & Ryan, 2008).

However, even career literatures tend to explore domains as separate from each other; rarer is exploration of how life domains integrally affect each other (cf. Georgellis, Lange, & Tabvuma, 2012; Ladge, Clair, & Greenberg, 2012). We argue that in order to more fully capture job-related well-being, we should explore the sense of satisfaction with the job’s fulfillment of multiple meanings that fit with or facilitate meaning, health, family, leisure, religion, and community across the life course.

Third, in vocational and general psychology, there is emerging interest in eudaimonic, meaning-based well-being and its origins and consequences (e.g., Dik, Byrne, & Steger, 2013; Markman, Proulx, & Lindberg, 2013). Two aspects of context-free well-being, explicated in Table 1, resurrect notions from ancient philosophy and theology (Ryan & Deci, 2001; Waterman, 1993). Eudaimonic, psychological, meaning-based well-being (Ryff, 1989) is less researched than hedonic, subjective, pleasure-based well-being (Diener, 2009). This suggests that there could be important eudaimonic origins of job-related well-being as well. As noted earlier and in the penultimate row of Table 1, hedonic conceptualizations of JS are also well established. However, we are not aware of any measures of eudaimonic job satisfaction.

As applied to jobs, hedonia and eudaimonia reflect distinct assumptions about what drives efforts toward jobs: pleasure and enjoyment of jobs, job experiences, or job outcomes—hedonic reasons; or meaning and purposes of jobs, job experiences, or job outcomes—eudaimonic reasons. As Table 1 implies, the hedonic emphasizes the job itself or its facets and outcomes as enjoyable to have or do, whereas the eudaimonic emphasizes the job, facets, or outcomes as fitting, appropriate, or right to have or do in pursuit of meaningful purposes. Therefore, as reflected in the last row of Table 1, we define JS as a positive psychological state resulting from an evaluation of one’s job, or job-related experiences or outcomes, where positive evaluations result in states of felt pleasure and enjoyment. This definition follows Locke’s (1976, p. 1300): “a pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one’s job or job experiences.” Based on the above review, we define MJW as a positive psychological state resulting from an evaluation of whether one’s job, or job-related experiences or outcomes fulfill purposes one considers worthwhile, where positive evaluations result in states of felt rightness and meaningfulness.

Facets of Job-Related Well-being

Locke’s (1969, p, 330) notion that “…overall job satisfaction is the sum of the evaluations of the discriminable elements of which the job is composed…” explains JS as a composite measure, comprised of satisfactions with facets of jobs (also see Law, Wong, & Mobley, 1998). That is, a worker may be satisfied with some facets, say tasks and co-workers, but not with others, say supervision and compensation. Similar dynamics likely exist for satisfaction with meaning of jobs; that is, there is not one global meaning of jobs, rather there are a number of facets of meaning, and a worker may be satisfied with some facets, say a sense of contributing to the greater good and facilitation of civic life, but not others, say facilitation of family life or personal growth.

Warr (2007, p. 11) notes two sources for meaning-based facets, and both tap appropriateness or rightness: standards external to individuals, such as religious or ethical doctrines, and standards arising from “a person’s own view of what is fitting for him or her, for example, in terms of a personal ideology, core values, or a vague awareness of ‘how I should be.’” Similar to the latter notion, the meaning of a job has been conceptualized as its personal relevance to the individual doing it (Guion, 1992). These two sources are interrelated, because individuals often internalize external standards that may originate from their religions, families, or cultures (Warr, 2007). Thus, communal standards may account for commonalities in facets of meaning across individuals. Meanings generally considered worthwhile for taking a job or doing it well can be identified that individuals share (Budd, 2011).

To identify common meanings, we reviewed meaning of work literatures across disciplines, including reviews of the meanings of work or jobs in management and organizational psychology (e.g., Brief & Nord, 1990; Dik et al., 2013; Markman et al., 2013), philosophy and labor economics (e.g., Budd, 2011; Muirhead, 2004), and theology and the humanities (e.g., Meilaender, 2000; Placher, 2005). Themes existed along a spectrum nested on one end in a positive self-image or identity and on the other end in community, life, and relationship interdependencies, as illustrated in the leftmost column of Table 2. This spectrum reinforces our conceptualization of jobs as instrumental to larger purposes for the self in relationship to others, in community, across life domains.

Although a variety of terms are used across literatures, as reflected in the rightmost column of Table 2, six discriminable elements of meaning for jobs were identified, as in the middle column of Table 2. Themes related to the individual include expression and development of self or identity. Themes related to interdependencies include impact on family as self-defined and impact on life in community. Themes that bridge self and interdependencies include having a purpose that transcends self or contributes to the greater good, and having an acceptable or preferred standard of living, whether subsistence and thriving, both of which benefit self, but also family or significant others and the larger community or society.

According to reviews (e.g., Judge et al., 2002), the most often used measures of JS are the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ; Weiss, Dawis, England, & Lofquist, 1967) and Job Descriptive Index (JDI; Smith, Kendall, & Hulin, 1969). The widespread adoption of the specific sets of facets in the MSQ and JDI has occurred despite cautions from their developers that any set of facets is not applicable to all jobs or workers (Dawis, Pinto, Weitzel, & Nezzer, 1974; and see Highhouse & Becker, 1993). The 20 MSQ facets were culled from 55 facets empirically derived across different populations (Dawis, personal communication).

Job satisfaction research during the era when the MSQ and JDI were developed revealed four primary facets: work tasks, work relationships, organization, and rewards (Friedlander, 1963). We use these categories, because different patterns of narrower facet satisfactions (e.g., in the MSQ, work relationships comprise satisfaction with co-workers, supervision-technical, and supervision-human relations) are found across different groups, or profiles, of workers (Dawis et al., 1974). There is potential overlap between satisfaction with rewards and all eudaimonic facets. That is, rewards could be broadly conceptualized as fulfillment of the purposes for taking and doing the job. However, the MSQ and JDI measure satisfaction with pay and compensation, respectively, and promotions or advancement. We explore the impact of jobs on standard of living separately from other meaning- or pleasure-based facets.

Although JS is a composite construct (Law et al., 1998), researchers often use three different types of measures as if they were interchangeable: facets, composite (a sum or average of all facets), or global JS. Using these as if they were equivalent has led to misinterpretation of research findings (Highhouse & Becker, 1993; Kinicki et al., 2002). Adding to confusion, both composite and global measures are sometimes referred to as “overall” JS. We explore all three types of measures, and their relationships to each other and outcomes, in these studies.

Overview of Empirical Exploration of MJW

The primary purpose of this research is to explore an alternative, meaning-based conceptualization to JS, and secondarily to provide one specific conceptualization of MJW and a set of instruments for further research. Reviews of the relationships between individual employees’ attitudes and performance, and to organizational performance, indicate that there is some doubt about whether individual performance translates directly into organizational performance (DeNisi & Sonesh, 2011). These reviews highlight attitudes that are important, some more for individuals, some more for teams, and some only for organizations, which may contribute independently to organizational performance (Wildman, Bedwell, Salas, & Smith-Jentsch, 2011). Thus, different individual attitudes affect different elements organizational performance directly and indirectly (Harter et al., 2002). Different individual worker attitudes and behaviors relate to each other, and contribute uniquely to overall worker well-being and organizational well-being and performance.

Some individual employee attitudes may contribute more directly to performance (e.g., engagement), and others more through turnover (e.g., work-family conflict, inclusion). Engagement is a “unique and important motivational concept” that measures the harnessing of an employee’s full energies into work (Rich et al., 2010, p. 617); it may moderate the relationship between satisfaction and performance (Harter et al., 2002). Other individual employee attitudes may be more important in some populations of workers. For example inclusion, defined as “the degree to which an employee perceives that he or she is an esteemed member of the work group through experiencing treatment that satisfies his or her needs for belongingness and uniqueness” (Shore, Randel, Chung, Dean, Holcombe Ehrhart, & Singh, 2011, p. 1265), is becoming more important as diversity increases (Avery, 2011; Wildman et al., 2011). The ability to effectively manage family responsibilities and work may also affect diverse workers differently (Avery, 2011; Rothausen, 1994).

Whether for all employees, or more for some than others, all these different attitudes also contribute to life satisfaction, and life satisfaction and satisfactions with the job are iteratively related (Tait, Padgett, & Baldwin, 1989); that is, job satisfaction is a big part of life satisfaction, but high life satisfaction can also positively affect one’s assessment of one’s job. Hoppock (1935) pointed this out over 80 years ago and Warr (2007) emphasizes this now. Thus, for example, if a worker moved to a community for a job, or was a native of the community in which she or he wanted to stay, having high satisfaction with family and community relationships contributes to job satisfaction. This, in turn, also contributes to community or society well-being (Oishi, 2012). Because engagement, inclusion, work-family conflict, retention or intention to quit, and life satisfaction contribute in different ways to individual, organizational, and societal well-being, we explored the impact of MJW and JS on these five outcomes in three studies, through three hypothesis sets.

Hypotheses 1: a, b, and c explore the distinctiveness of MJW from JS and other job attitudes. Hypothesis 2 explores the value of adding MJW for predicting outcomes, and whether MJW and JS relate differently to outcomes. Hypotheses 3: a, b, and c explore facet-to-global relationships for the facet set developed. Table 3 presents all hypotheses, each of which is developed below, and indicates which hypotheses are tested in each study. In addition, this table summarizes our results, noting whether each hypothesis was supported. Rather than repeatedly stating these hypotheses throughout our discussion of the studies below, we refer to this table.

As with general hedonic and eudaimonic well-being, MJW and JS may be related but distinct (Warr, 2007; Waterman, 1993). Individuals may feel their jobs are unpleasant but have worthwhile meaning, or are enjoyable but relatively void of meaning. The two may even be in opposition, as when an altruistic motive leads to taking an unpleasant job. Overall, however, we expect JS and MJW to be distinct though related (hypothesis 1a). Work involvement assesses identification with work and the centrality of work in life (Kanungo, 1982). Organizational commitment is an attitude toward an organization comprising assessments of identification with the organization, internalization of its goals, norms, and values, and readiness to serve and enhance its interests (Sollinger, van Olffen, & Roe, 2008). An employee may be involved in work or committed to an organization because work in the organization is enjoyable or meaningful to the worker. Therefore we expect these attitudes to be distinct from but related to both JS and MJW (hypothesis 1b and 1c).

If extant conceptualizations of JS are hedonic, adding MJW is analogous to adding puzzle pieces that have been missing, and MJW and JS together should relate more strongly to outcomes than does JS alone. Therefore, we expect that after controlling for levels of JS, MJW relates to the work, life, and work-life outcomes of engagement, inclusion, intention to quit, work-family conflict, and life satisfaction (hypothesis 2).

If the facets of JS identified above (i.e., work itself, work relationships, organization) comprise JS, they will be more related to global JS than to global MJW (hypothesis 3a). Similarly, if facets proposed in Table 2 comprise MJW, they will be more related to global MJW than to global JS (hypothesis 3b), except that jobs’ impact on standard of living will likely be more equally related to both MJW and JS (hypothesis 3c), for reasons explicated above.

Study 1: Primary Exploration

All hypotheses were tested in the primary exploration.

Method

Samples and Procedures

Data were collected via electronic survey, from working adults who were asked to consider completing the survey questionnaire by students in two cohorts of a full-time MBA program. The data were collected for purposes of this research as well as for a cross-course project in the MBA program for each cohort. Students were asked to invite a variety of working people from their professional networks to participate. For the first cohort, links to the survey were sent to 346 people and 157 completed it for an effective response rate of 45%. For the second cohort, an incentive to complete the survey was added, which was a $10 coffee house gift card. Links to the survey were sent to a total of 525 people, and 268 completed it for an effective response rate of 53%. These two primary collections were combined for hypothesis testing, which resulted in a total sample of 425 respondents. The average age of respondents in this combined sample is 32 (SD = 10). The majority of respondents (88%) have bachelor’s degrees and 32% have graduate degrees. The average tenure with their organizations is 5 years (SD = 6), 79% are white, and 57% are female. When compared to national worker databases, this sample is younger, more educated, and more female, but similar in terms of race (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016).

Measurement

A seven-point Likert scale ranging from strongly dissatisfied or disagree (1) to strongly satisfied or agree (7) was used for all items. Job satisfactions, work involvement, organizational commitment, engagement, inclusion, intention to quit, work-family conflict, and life satisfaction were assessed. Demographic information was also collected. Alpha coefficients are reported in Table 4 on the diagonal, and are .70 or higher for all scales.

Facet satisfactions were measured with three items each, including satisfaction with tasks, work relationships, organization, expression, development, a purpose that transcends self through the job role, impact on standard of living, impact on family as defined, and impact on life. Facet satisfactions were measured with items modeled on MSQ items (Weiss et al., 1967) adapted to reflect the hedonic and eudaimonic facets identified above. MSQ items were modeled due to their strong internal consistency (Kinicki et al., 2002). Composite MJW and JS were created by averaging responses to the facets work tasks, work relationships, and organization for composite JS and averaging responses to the facets expression, development, purpose, family, and life for composite MJW.

Global JS and global MJW were each measured with four items adopted or adapted from the review of job satisfaction in Judge et al. (2002), and replacing key language with that from eudaimonic well-being conceptualizations, customized to jobs as appropriate. For example, Judge et al. (2002) reviews scales with the items, “I find real enjoyment in my work” and “I consider my job to be rather unpleasant,” which we adapted to “I experience enjoyment in my job” and “My job is pleasant.” As we note in Table 1, the work on meaning-based, eudaimonic well-being is not as developed as that on enjoyment-based, hedonic well-being. Noting that in these literatures, meaning is often used interchangeably with purpose or contribution, we adapted the form of the item “My job is pleasant” to incorporate the sense of contribution or making a difference, including items such as “My job makes a contribution” and “My job helps others.” All items measuring global and facet JS and MJW are reported in the appendix. The 20-item, short-form MSQ was also included (Weiss et al., 1967), adapted to update language and for the 7-point Likert scale.

Work involvement was measured with three items adapted from Kanungo (1982); these items are “I consider my job central to my life,” “A major satisfaction in my life comes from my job,” and “I am very much involved personally in my job.” Organizational commitment was measured with three items adapted from Sollinger et al. (2008); these items are “I am committed to the success of the organization in which I work,” “I am loyal to this organization,” and “I will work hard so the goals of the organization can be met.” Engagement was measured with nine items from Rich et al.’s (2010, p. 634) measure, using three items from each subscale as follows: physical engagement (items 2, 3, and 4 from their subscale used verbatim), emotional engagement (items 2, 5, and 6 from their subscale used verbatim), and cognitive (items 2, 3, and 4 from their subscale, adapted slightly to fit other items in our scale). Inclusion was measured with eight items based on Shore et al.’s (2011) conceptualization of inclusion; four items for each subscale: uniqueness and belonging. Uniqueness items are “I can be fully who I am in this organization,” “What’s different about me is valued in this organization,” “My uniqueness is valued at work,” and “I am encouraged to use my unique perspective at work.” Belonging items are, “I am a welcomed member of this organization,” “My contributions are valued in decision making at work,” “I belong in this organization,” and “I feel like an insider at work.” Intention to quit was measured with four items adapted from the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire (Camman, Fichman, Jenkins, & Klesh, 1979). Work-family conflict was measured with three items adapted from Kopelman, Greenhaus, and Connolly (1983). Life satisfaction was measured with four items from the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener, 2009). In these scales, items from established measures were used; however, the full measures were not always used due to space constraints.

Data analysis

Hypotheses were tested using correlational, confirmatory factor analytic, and hierarchical regression techniques. Correlations were compared using Steiger’s Z test. Confirmatory factor analysis was run for facet satisfactions; two sets of five hierarchical regressions were run, two each on the outcomes engagement, inclusion, intention to quit, work-family conflict, and life satisfaction. Two hierarchical regressions were run of facets on each global JS and on global MJW. Details of hypothesis testing analyses are included in the next section.

Results

Means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations for all variables are reported in Table 4 (composite JS and composite MJW are not reported because they are an additive function of facets). This table reveals that global and facet measures of job-related well-being are related to each other, as expected, but not highly enough to suggest interchangeability. The MSQ correlates highly (i.e., over .8) with five of the nine facets and with global job satisfaction. A high correlation is also noted between two of the facet satisfactions, impact on family and impact on life; it may be that jobs’ impact on family comprises a large part of satisfaction with impact on life, at least in this sample. Table 4 also reveals that correlations among the outcome variables of interest are low to moderate. Finally, the demographic variable of age is related to many satisfactions as well as to outcomes, and is thus controlled for in hypothesis testing.

To test hypothesis 1a (see Table 3), we examined correlations among global and facet JS and MJW, and performed confirmatory factor analyses. Table 4 reveals that global JS and global MJW are correlated .63 (p < .01), which indicates a strong relationship, but is not high enough to suggest interchangeability. Facets intercorrelate from .25 to .82, averaging .60. A confirmatory factor analysis of all hedonic and eudaimonic facets indicated relatively good fit (as per guidelines in Hu & Bentler, 1999) for the nine-factor facet job satisfaction model (X2 = 984.91, df = 288, CFI = .98, SRMR = .05, and RMSEA = .08) with all factor loadings greater than .64 (p < .001), suggesting that a nine facet model fits the data well. We also examined three alternative models including a one-factor model, a two-factor model with all facet MJW items loaded on one factor and all facet JS items on a second factor, and a three-factor model where facet MJW items were split between self-oriented and interconnectedness-oriented; the nine-factor model fit the data better with respect to all fit indices. To test hypotheses 1b and 1c, we examined correlations in Table 4 between all facets with work involvement and organizational commitment and performed a factor analysis using global JS and MJW. Examination of Table 4 shows all facets significantly related with both work involvement and organizational commitment, ranging from .25 to .69, some higher with work involvement and some higher with commitment. Global and composite MJW and JS were also significantly correlated to both work involvement and organizational commitment, with correlations ranging from .56 to .73. A confirmatory factor analysis of global JS, global MJW, work involvement, and organizational commitment indicated relatively good fit (as per guidelines in Hu & Bentler, 1999) for the four-factor model (X2 = 292.67, df = 71, CFI = .99, SRMR = .04, and RMSEA = .09), and this model fit the data better than all possible three-, two-, and one-factor models. These results support hypotheses 1a, 1b, and 1c.

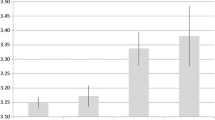

Hypothesis 2 (see Table 3) was tested with five hierarchical regressions of outcomes on age in step 1, facet JS in step 2, standard of living in step 3, and facets of MJW in step 4; this ordering is the most conservative test of MJW facets’ value. The results are reported in Table 5, with the change in R2 for each step reported, but only the significance levels of coefficients and only for the final, step 4 model, for pattern identification. We also ran similar hierarchical regressions twice more, replacing facets with composite measures, leaving out satisfaction with the job’s impact on standard of living, once entering JS first and again entering MJW first. Results are reported in Table 6.

Table 5 reveals that adding facet MJW after controlling for facet JS and satisfaction with impact on standard of living explained additional variance in all outcome variables measured; for one outcome, work-family conflict (WFC), adding facet MJW caused the overall results to be significant. Table 5 also reveals that patterns of final equation coefficients include significant coefficients for at least one eudaimonic facet for all outcomes. These results were statistically significant, but more importantly, adding MJW explained an additional 4–11% of the variance in these five outcomes, beyond JS facets, equaling 7 to 85% of the total variance in each outcome explained by facets (see Table 5). Table 6 reveals that whichever composite—MJW or JS—is entered first explains comparable amounts of the variances in outcomes, with the one entered second adding significant additional explanation of variance, with the two exceptions that composite JS did not explain significant variance in WFC when entered first and did not explain significant additional variance in life satisfaction when entered second. Overall, these results support hypothesis 2.

Hypothesis 3a through 3c (see Table 3) were tested by running two hierarchical regressions, of global JS and global MJW, on age in step 1, facet JS in step 2, satisfaction with standard of living in step 3, and facet MJW in step 4. Results are presented in Table 7. Table 7 reveals that facet JS explained 73% of variance in global JS, but only 37% in global MJW. Satisfaction with impact on standard of living explained little to no additional variance in either global JS or global MJW. Facet MJW explained an additional 6% of variance in global JS, and an additional 26% of variance in global MJW.

The coefficients of the final global JS equation show that all three hedonic facets are significant as expected; however, those for two of the five eudaimonic facets (expression and life impact) are also significant in the expected direction, and a third (family impact) is significant in the opposite direction. Correlational analysis shows impact on standard of living related to both global JS and global MJW, but is the least related of the facets. After consideration of the three primary JS facets, this facet added little additional explanation to either global satisfaction. The coefficients of the final global MJW equation show that three of the five eudaimonic facets are significant as expected (development, purpose, and family impact); however, one hedonic facet (organization) was also significant but in the direction opposite that expected (possibly suggesting trade-offs in this sample between working for “a good organization” and having more meaningful work). Overall, these findings support hypotheses 3a and 3b, and do not support hypothesis 3c. However, the overall support of hypotheses 3a and 3b is qualified in that two facets we expected to be meaning-based or eudaimonic—expression of self and impact of the job on life—related more with global JS, one meaning-based facet (family) related positively to global MJW as expected but also negatively to global JS, and one pleasure-based facet (organization) related positively to global JS as expected but also negatively to global MJW.

Discussion of Study 1

Study 1 findings suggest that MJW and JS are equally compelling conceptualizations of job-related well-being, and that they are related but distinct concepts. JS and MJW were distinct not only from each other but also from other job attitudes. MJW added explanation of variance in each outcome, beyond that explained by JS. Each MJW facet was significant in the final equations for at least one of the five outcomes after consideration of the more commonly studied JS facets. In order to explore the generalizability of these findings, beyond this one sample, we pursued replication in two other types of samples.

Study 2: Organization-Based Study

In a study designed primarily for organizational purposes, we had the opportunity to further explore the relationship of our facet conceptualizations of MJW on an organizationally relevant outcome, over and above JS facets, in a very different type of sample. Due to organizational interests, we were only able to include facet items and an intention to quit scale. Therefore, we were able to test hypothesis 2 (see Table 3) for this outcome.

Method

Samples and Procedures

Data were collected via electronic survey of employees of two small, privately held business: a home health-care provider and a resort. An email containing the link to the survey was sent to all 429 employees of these 2 organizations. Ninety-two employees filled out the survey and complete, useable data was available for 89 workers for a 21% effective response rate. Compared to the sample from study 1, described above, respondents were on average less educated (59 v. 88% bachelor degrees), older (40 v. 32), more female (75 v. 57%), more white (87 v 79%), and with longer tenure in their jobs (11 v. 5 years). When compared to national worker databases, this sample is more educated (but less educated than the sample from study 1), female, and white, but similar in terms of age (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016).

Measures

The same facet and global MJW and JS items were measured as in study 1, as reported in the appendix. All Cronbach’s alphas were above .80. Intention to quit was also measured with four items adapted from the Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire (Camman et al., 1979).

Data analysis

We tested hypothesis 2, but only for intention to quit, as that was the only outcome measured with this sample. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a hierarchical regression of intention to quit on the control variable in step 1, facet JS in step 2, satisfaction with impact on standard of living in step 3, and facet MJW in step 4.

Results

Results indicate that the final overall equation is significant (F = 3.67; p < .001), and that changes in R2 were significant for the second step (change in R2 = .20; p < .001) and the fourth step (change in R2 = .11; p < .05). In the final equation, βs for satisfaction with work tasks (p < .05) and job impact on family (p < .01) were significant in the expected direction. This supplementary analysis lends additional support for hypothesis 2 (see Table 3), though for intention to quit only.

Discussion of Study 2

In an older, less-educated, organization-based sample, facet MJW explained additional variance in intention to quit that was not only statistically significant, but was substantively significant, adding an additional 11% of explained variance in an equation that explained a total of 39% of the variance in intention to quit. Given the significant results in studies 1 and 2, we were eager to explore MJW in yet another different type of sample.

Study 3: Limited Replication in Third Type of Sample

In a study designed for another purpose (Henderson, Welsh, & O’Leary-Kelly, 2018), we had the opportunity to further explore the core idea that MJW is separate from JS and other job attitudes. Due to space limitations in the survey, we only included global JS and MJW measures, and the survey also measured organizational commitment. Therefore, we were able to test hypotheses 1a and 1c (see Table 3), but using only global measures.

Method

Sample

Respondents were recruited using Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk). Participants had to fit several MTurk and study-specific criteria, which have been shown to improve the quality of responses (Cheung, Burns, Sinclai & Sliter, 2017). Only MTurk masters with approval ratings above 95% for previous tasks, who were also located in Canada or the United States, could view the survey, and were paid a $2.00 honorarium. Masters status has been found to improve the quality of responses (Peer, Vosgerau, & Acquisiti, 2014), and cultural variability was limited for the study. Eligibility was further limited by requiring that respondents were working at least 20 h per week at one organization and were 18 years of age or older. When compared to national worker databases, this sample is younger, but similar with respect to gender, education, and race (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016).

Three hundred ninety-eight working adults participated in this study; 82% are white and 51% are male. Three of the participants answered the survey twice and only their first response was included (Cheung et al., 2017). Average age is 35 years (SD = 10) and average organizational tenure is 5 years (SD = 4). The majority of respondents (85%) have at least some college and 45% have bachelor’s degrees. Participants worked in a variety of industries, with the most common industries being retail/travel (16%), technology (14%), health care (9%), and education (8%).

Measures and Analysis

A seven-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7) was used for all items. Global JS (α = .95) and global MJW (α = .94) were measured with the same items used in study 1 (included in the appendix). The six-item Organizational Commitment scale from Meyer, Allen, and Smith (1993) was used to assess organizational commitment (α = .91). Hypotheses 1a and 1c (see Table 3) were tested using correlational techniques and confirmatory factor analysis. We also conducted a hierarchical regression of organizational commitment on the control variables (age, tenure, education, gender) in step 1, global JS in step 2, and global MJW in step 3 in order to examine if global MJW relates to organizational commitment beyond global JS.

Results

Means, standard deviations, reliabilities, and intercorrelations for age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, tenure, and the three job attitudes were examined. Several demographic variables were correlated with the job attitudes, including global JS with tenure (r = .11, p < .05); global MJW with age (r = .11, p < .05), tenure (r = .11, p < .05), and education (r = .15, p < .01); and organizational commitment with tenure (r = .20, p < .001). Global MJW and JS were correlated .66 (p < .001), not enough to suggest interchangeability, replicating results in study 1. Organizational commitment was correlated .77 with global JS and .65 with global MJW, also replicating the pattern found in study 1.

The two-factor global MJW-global JS model had better fit (X2 = 48.84, df = 19, CFI = .99, SRMR = .02, and RMSEA = .06) than a one-factor model (X2 = 1240.59, df = 20, CFI = .83, SRMR = .13, and RMSEA = .39). In addition, a three factor model with global MJW, global JS, and commitment had better fit (X2 = 295.34, df = 74, CFI = .98, SRMR = .04, and RMSEA = .09) than all potential two-factor models and a one-factor model, supporting that JS, MJW, and commitment are separate constructs. The regression results indicate that the final overall equation is significant (F = 119.32, p < .001) and the change in R2 was significant for the third step. More specifically, global MJW explained an additional 4% of variance (p < .001) in organizational commitment beyond global JS. Hypotheses 1a and 1c were supported.

Discussion of Study 3

Study 3 provided additional support for the idea that MJW and JS are related but distinct, and that they relate differently to another job attitude, in a type of sample that is different from those in study 1 and study 2, and using a different measure of organizational commitment. Together with studies 1 and 2, these results suggest generalizability for the idea that MJW is a distinct alternative conceptualization of worker well-being to JS.

General Discussion

The primary contribution of this research is demonstrating that a theory-based concept of meaning-based job-related well-being (MJW), which “points to” different, and potentially important, sources of satisfaction related to jobs than those usually considered, predicted outcomes equally as well as, or better than, the traditionally used conceptualization of JS. Based on our findings, at a minimum MJW relates to outcomes equally with JS; whichever type of satisfaction was entered into equations first explained much of the variance attributable to job-related well-being for most outcomes. When added after JS facets, MJW facets explained an average of 25% more variance as a proportion of total variance explained in the five outcomes in study 1 (11% excluding the outlier value for work-family conflict), as shown in Table 5.

This in itself may not be enough to encourage development of MJW; however, in combination with evidence from other literatures of the substantive importance of eudaimonic well-being in addition to hedonic well-being, and the recent emphasis in public policy arenas of correcting a previous tendency to measure well-being too narrowly (Lefkowitz, 2016; Oishi, 2012; Warr, 2007), it is inviting of additional research. If we conceptualize job-related well-being as deriving only from the workplace in isolation, our focus will be relatively narrow; however, if we acknowledge that job-related well-being derives from the fulfillment of human needs toward work that arise from and impact workers’ lives and communities, our focus broadens from enjoyment of work in isolation from its meaning, to meaningful and whole-life-affirming work. Consideration of meaningfulness is a vital element for healthy societies.

Contributions to Research

Although these studies are exploratory, they make at least four primary contributions to research. First, our findings suggest that MJW is distinct from but related to JS; that each is distinct from, but related, to work involvement and organizational commitment; and that in a conservative test, MJW facets add significant explanation of variances in engagement, inclusion, intention to quit, work-family conflict, and life satisfaction, beyond that explained by JS facets. Evidence for the distinctiveness of global MJW and global JS was found in both studies in which we explored it—studies 1 and 3. Evidence that facet MJW adds significant explanation of variances in the outcomes we explored, beyond that explained by facet JS, was found in all six tests across five outcomes in studies 1 and 2. MJW facets added an average of 7% to explained variance across five outcomes in study 1 (step 4 change reported in Table 5; specifically 5% for engagement, 5% for inclusion, 4% for intention to quit, 11% for work-family conflict, and 8% for life satisfaction), and 11% for intention to quit for study 2. Together with other research (e.g., Highhouse & Becker, 1993), this suggests that the most relevant measure to use to capture job-related well-being depends on the type of outcome of interest, and that researchers should not assume job satisfaction is unitary. If our findings are replicated, we can conclude that although JS and MJW share some variance, they also contribute independently and differentially to outcomes, related to our third contribution, discussed below. These outcomes, in turn, each contribute to organizational and societal well-being (Harter et al., 2002; Oishi, 2012).

Second, each MJW facet showed strong relationships with one or more of the outcomes, even after considering the JS facets. This suggests that these specific meaning-based facets, which are not included in extant conceptualizations, are important to consider. Our research here is exploratory, however, supporting our conclusions are the results of two research papers that developed in parallel to our early developmental work for these studies, after we created the instrument used in study 1. One is a comprehensive review of the meaning of work literature in organizational research (Rosso, Dekas, & Wrzesniewski, 2010) and the second is a qualitative study of why people leave jobs (Rothausen, Henderson, Arnold, & Malshe, 2017). The results of these two studies generally both confirm our findings, but also highlight key differences that will be important to address in future research. Together with our findings, these two studies provide a compelling confirmation for MJW. Table 8 summarizes our findings alongside the findings from these other two research papers.

Given that each study uses different methodologies, the conceptual overlap shown in Table 8 is striking. In Table 2, we show meaning-based facets along a continuum from individual self and identity on one end, to community, life, and relationship interdependencies, or interconnectedness, on the other. Examination of Table 8 shows that the individual end of this continuum may be more finely developed than the interconnectedness end. The facet we explored and termed “expression of self” may in fact comprise at least three sub-facets: self-esteem/acceptance, self-efficacy (or agency), and authenticity/differentiation, as well as a sense of the growth or development of the self as a fourth sub-facet or a separate facet. On the interconnected end of this continuum, there are three primary themes. First, these research papers all identify elements related to “building a life” or “constructing a self” with some sense of coherence or purpose. Second, these papers identify an element of transcendence or sense of contributing to something beyond self. Different terms are used across these two themes, including purpose, life construction, and transcendence. Together, these reflect two dimensions, one that is self- or individual life-oriented and the other that is oriented beyond the self. A third element on the interconnected end of the continuum, identified across all these research papers in different forms, is relationship or relatedness; in the other two papers, this aspect is more general than the family-specific facet we used. Finally, it is notable that neither of these other two papers identified standard of living for self or others as a facet of the meaning of work. This is likely because we reviewed labor economics and theology literatures in developing our model of facet MJW, both of which contain this concern as one meaning of work.

A third contribution of our studies is confirming that MJW facets were related differently to different outcomes, just as with JS facets, as prior research has shown (Highhouse & Becker, 1993; Kinicki et al., 2002). Specifically, in study 1, the facets of satisfaction with expression of self, development of self, and a role with transcendent purpose were significant for the outcome of engagement; expression and development of self for inclusion; expression of self and impact on life for intention to quit (though in study 2 only impact on family was significant for intention to quit); and impact on family and impact on life for both work-family conflict and life satisfaction.

Some evidence from our studies suggests that facet relationships may vary by type of sample. In study 2, where the only outcome measured was intention to quit, satisfaction with tasks (a JS facet) and impact on family (a MJW facet) are most related to intention to quit, whereas in study 1, satisfaction with organization (JS), expression of self (MJW), and impact on life (MJW) are most related. The majority of the study 2 sample was home health care workers, who often work independently, directly with clients, and with flexible hours. Thus, though they work for the organization, they do not work literally in it, and this may help them manage family responsibilities, which could explain this pattern of results. Also, in contrast to study 2, the study 1 sample is younger and more highly educated. These findings suggest that, although JS has been conceptualized as a composite of facets, it may be better conceptualized as a profile measure (see Law et al., 1998), which we discuss further below.

Based on our exploratory results, MJW could deepen understanding of job-related well-being and job satisfaction, and our fourth contribution is one model and set of measures to further explore this. Together with the research presented in Table 8, this provides a solid foundation for developing this construct further. Of course, replication is needed in different types of samples, and limitations of our work should be addressed, as discussed below. Extant conceptualizations point to facets of jobs as the key to worker satisfaction, downplaying the potential of fulfillment of core human needs in work, apart from their impact while at work, for workers’ lives in the larger world, and for society. We believe that exploring broader origins of job satisfaction, framing a job as an aspect of a life in social and societal context with broad implications outside work organizations, will lead to enriching discoveries about job satisfaction.

Contributions to Practice

When primary elements of jobs are enjoyable and meaningful, employees may be more likely to be engaged, feel included, stay in their organizations, and have higher levels of life satisfaction or overall well-being in life. Our empirical results suggest that each meaning-based (eudaimonic) facet relates to one or more important outcome, and we know from other research that in turn engagement, inclusion, and retention likely each contribute something to organizational performance (Harter et al., 2002). Thus, although the three studies in this research are only an initial exploration of MJW, it is possible that the nine general JS and MJW facets identified here and as summarized with other findings in Table 8, together, will prove to provide an expanded set of considerations for building an ecosystem of engaged retention in organizations.

Based on our findings, then, in addition to improving the quality of tasks, work relationships, and the organization, managers and leaders may also want to improve the extent to which jobs allow for individual expression and development, and pay attention to the sense of the meaningful or transcendent purpose of each work role, as well as the overall impact of jobs on workers’ families and lives. Some authors have suggested that workers currently coming into the workforce and younger generations may seek meaning in their work earlier in life than did previous generations of workers (e.g., Dik et al., 2013), which suggests that MJW may become increasingly salient. Organizations that pay attention to the range of primary desires, wants, expectations, and needs employees bring to the organization may be able to develop a competitive advantage relative to those that do not (Harter et al., 2002). The model of facet job-related well-being here provides an initial exploration of one specific conceptualization for this type of organizational development.

Important implications of this study for career and vocational practices, should findings be replicated, include consideration of more focus on how work facilitates family life, whole lives in general, the expression and development of self, a sense of transcendence through a meaningful purpose, and overall (not only economic) standard of living, in addition to fit with abilities, personality, interests, and values. Those in work transitions could be encouraged to more intentionally consider their whole lives and the larger meaning of work within it. Adjustment to work may depend not only on a match of individual traits to the job (see Dawis & Lofquist, 1984) but also perhaps on the overall ways that a job facilitates a life and impacts the world.

At the societal level, there is increasing discussion of the need to focus on measures of happiness and meaning in balance with economic and financial measures such as GDP, quarterly profits, and performance, when considering a society’s health (Budd, 2011; Oishi, 2012). Business organizations are a key part of society, and sound and holistic conceptualizations and measures are needed in order to show how jobs they provide contribute to or detract from well-being. Business organizations have been criticized for treating the employment relationship as an economic exchange relationship, while downplaying the widespread impact of jobs on workers, families, and communities, and for contributing to promoting self-interest in how they frame incentives (e.g., Lefkowitz, 2016; Oishi, 2012). MJW, when added to JS, may provide a more complete way to measure the impact of organizations and jobs on worker well-being, for businesses trying to respond to such criticisms, and for public policy makers interested in understanding well-being in the employment setting.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

We encourage additional foundational research to replicate our exploratory work and address its limitations. One core limitation of this series of studies is the overrepresentation of younger, more highly educated workers. The samples for studies 1 and 3 are relatively young (average age 32 and 35 respectively). This may provide a conservative test for MJW, because meaning generally becomes more important as people move into middle age and older years (Kray, Hershfield, George, & Galinsky, 2013). Comparisons of results between studies 1 and 2 provide some support of this idea, in that facet MJW was related more to intention to quit in this older sample than in the younger sample. Also, we noted high correlations between the MJW facets impact on family and life in study 1, suggesting there may be just one family/life facet. However, again this was a younger, highly educated sample, and findings may be different in older samples, especially during ages children tend to be in the home (see Rothausen, 1994). Finally, the standard of living facet may be more important in samples with lower education, as income levels are generally correlated with education. Our primary samples are generally more female, substantially younger, and a lot more highly educated than the workforce in general, though our sample is proportional for white people and people of color (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016). These are areas for future research, and for replication in different samples.

Another key limitation of this research may be our measure of global MJW. Original items were developed using hedonic items and adapting them to include a key concept from some interpretations of eudaimonia in context-free eudaimonic well-being research—that of making a meaningful contribution—and we retained this measure for consistency across samples. However, as we note above and in Table 1, meaning-based, eudaimonic well-being is not as well developed as is enjoyment-based, hedonic well-being, and multiple models currently exist. Based on Ryan and Deci’s (2001, pp. 145–146) review, other options for measuring global MJW could instead focus on jobs that allow expression of virtues, do things that are “worth doing,” are in accordance with human growth or human nature, produce outcomes that are “good for people,” that are in “accordance with …true self,” or that “promote wellness.” In addition, there may be different foci for these outcomes across life domains (Rothausen et al., 2017), such that items could be split as “My job makes a contribution to improving my self,” “My job makes a positive contribution to my family,” “… to customers,” or “… to society.” Differences in these levels of contribution may be important to outcomes such as long-term motivation and retention.

Our exploration suggests that complex interrelationships between JS and MJW likely exist, including a possible temporal interrelationship. To paraphrase Warr (2007, p. 13), high MJW seems more likely to be followed by high JS, as experiences of MJW lead to pleasure or enjoyment because individuals feel pleased that they have met the standard of fulfilling worthwhile meaning through their jobs. MJW could be a cause of JS. Longitudinal studies exploring this would be very valuable in more deeply understanding the origins, depth, and breadth of job-related satisfaction and well-being.

Additional research could also explore processes through which facet satisfactions combine to impact different outcomes, and their differences with global satisfactions. Some of our findings suggest that, although JS has been conceptualized as a composite of facets, it may be better conceptualized as a profile measure (see Law et al., 1998). For example, for those with high levels of family responsibility, the family facet may highly impact intention to quit, as was true in study 2 data, but a different profile may be important for those with little to no responsibility for family as other research has suggested (e.g., Rothausen, 1994).

Conclusion

Like E.B. White, workers want to have both meaningful impact and pleasure through jobs. Locke’s (1976) notion was that JS is an affect toward the job based on an evaluation of experiences with facets of the job; however, a job is not taken up merely to enjoy experiencing its facets and outcomes, or only for pay, but for much broader purposes that relate directly to workers’ worlds and transcendent purposes. Fulfillment through the meaning for which workers do jobs, and the impact of jobs on workers’ worlds, may be vital to job-related well-being, and in turn to engagement, inclusion, and retention, as well as to overall well-being in life. We argue that to fully understand job-related well-being, the roles jobs play in workers’ worlds should be central, and in three studies totaling 811 working adults, we explore one such conceptualization, MJW. This exploration is offered in the spirit of stimulating further development of meaning-based JS, and we hope our conceptualization and operationalization provide tools for those interested in researching good jobs, happy work lives, healthy human functioning, optimal human performance, and thriving societies.

References

Avery, D. R. (2011). Why the playing field remains uneven: Impediments to promotions in organizations. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, volume 3 (pp. 577–613). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Bowling, N. A., Khazon, S., Meyer, R. D., & Burrus, C. J. (2015). Situational strength as a moderator of the relationship between job satisfaction and performance: A meta-analytic examination. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30, 89–104.

Brief, A. P., & Nord, W. R. (1990). Meanings of occupational work: A collection of essays. Lexington: Lexington Books.

Budd, J. W. (2011). The thought of work. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (2016). Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/cps/demographics.htm. Accessed on November 15, 2017.

Camman, C., Fichman, M., Jenkins, D., & Klesh, J. (1979). The Michigan Organizational Assessment Questionnaire. Unpublished manuscript. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

Cascio, W. F. (2003). Changes in workers, work, and organizations. In W. C. Borman, D. R. Ilgen, & R. J. Klimoski (Eds.), Handbook of psychology, volume 12: industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 401–422). Hoboken: Wiley.

Cheung, J. H., Burns, D. K., Sinclair, R. R., & Sliter, M. (2017). Amazon mechanical Turk in organizational psychology: An evaluation and practical recommendations. Journal of Business and Psychology, 32, 347–361.

Dawis, R. V., & Lofquist, L. H. (1984). A psychological theory of work adjustment. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Dawis, R. V., Pinto, P. P., Weitzel, W., & Nezzer, M. (1974). Describing organizations as reinforcer systems: A new use for job satisfaction and employee attitude surveys. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 4, 55–66.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across life’s domains. Canadian Psychology, 49, 14–23.

DeNisi, A. S., & Sonesh, S. (2011). The appraisal and management of performance at work. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, volume 2 (pp. 255–279). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Diener, E. (Ed.). (2009). Assessing well-being: The collected works of Ed Diener. New York: Springer.

Dik, B. J., Byrne, Z. S., & Steger, M. F. (Eds.). (2013). Purpose and meaning in the workplace. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Dik, B. J., Duffy, R. D., & Eldridge, B. M. (2009). Calling and vocation in career counseling: Recommendations for promoting meaningful work. Professional Psychology Research and Practice, 40, 625–632.

Fila, M. J., Paik, L. S., Griffeth, R. W., & Allen, D. (2014). Disaggregating job satisfaction: Effects of perceived demands, control, and support. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29, 639–649.

Frese, M. (2008). The word is out: We need an active performance concept for modern workplaces. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1, 67–69.

Friedlander, F. (1963). Underlying sources of job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 47, 246–250.

George, J. M., & Jones, G. R. (1996). The experience of work and turnover intentions: Interactive effects of value attainment, job satisfaction, and positive mood. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81, 318–325.

Georgellis, Y., Lange, T., & Tabvuma, V. (2012). The impact of life events on job satisfaction. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80, 464–473.

Griffin, M. A., & Clark, S. (2011). Stress and well-being at work. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, volume 3 (pp. 359–398). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Guion, R. M. (1992). Agenda for research and action. In C. J. Cranny, P. C. Smith, & E. F. Stone (Eds.), Job satisfaction: How people feel about their jobs and how it affects their performance (pp. 257–281). New York: Lexington Books.

Harter, J. K., Schmidt, F. L., & Hayes, T. L. (2002). Business-unit-level relationship between employee satisfaction, employee engagement, and business outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 268–279.

Henderson, K.E., Welsh, E., & O’Leary-Kelly, A.M. (2018). “Oops, I did it” or “it wasn’t me:” An examination of psychological contract breach repair tactics. Working paper, University of St. Thomas-Minnesota.

Highhouse, S., & Becker, A. S. (1993). Facet measures and global job satisfaction. Journal of Business and Psychology, 8, 117–127.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44, 513–528.

Hoppock, R. (1935). Job satisfaction. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55.

Judge, T. A., Parker, S., Colbert, A. E., Heller, D., & Ilies, R. (2002). Job satisfaction: A cross-cultural review. In N. Anderson, D. S. Ones, H. K. Sinangil, & C. Viswesvaran (Eds.), Handbook of industrial, work, and organizational psychology, volume II (pp. 25–52). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Kanungo, R. N. (1982). Measurement of job and work involvement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67, 341–349.

Kinicki, A. J., McKee-Ryan, F. M., Schriesheim, C. A., & Carson, K. P. (2002). Assessing the construct validity of the job descriptive index: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 14–32.

Kopelman, R. E., Greenhaus, J. H., & Connolly, T. F. (1983). A model of work, family, and interrole conflict: A construct validation study. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 32, 198–215.

Kray, L. J., Hershfield, H. E., George, L. G., & Galinsky, A. (2013). Twists of fate: Moments in time and what might have been in the emergence of meaning. In K. D. Markman, T. Proulx, & M. J. Lindberg (Eds.), The psychology of meaning (pp. 317–337). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Ladge, J. J., Clair, J. A., & Greenberg, D. (2012). Cross-domain identity transition during liminal periods: Constructing multiple selves as professional and mother during pregnancy. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 1449–1471.

Law, K. S., Wong, C., & Mobley, W. H. (1998). Toward a taxonomy of multidimensional constructs. Academy of Management Review, 23, 741–755.

Lefkowitz, J. (2016). News flash! Work psychology discovers workers! Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice, 9, 137–144.

Locke, E. A. (1969). What is job satisfaction? Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 4, 309–336.

Locke, E. A. (1976). The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In M. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of organizational and industrial psychology (pp. 1297–1349). Chicago: Rand-McNally.

Markman, K. D., Proulx, T., & Lindberg, M. G. (Eds.). (2013). The psychology of meaning. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Meilaender, G. C. (Ed.). (2000). Working: Its meaning and limits. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

Meyer, J. P., Allen, N. J., & Smith, C. A. (1993). Commitment to organizations and occupations: Extension and test of a three-component conceptualization. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 538–551.

Muirhead, R. (2004). Just work. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Oishi, S. (2012). The psychological wealth of nations: Do happy people make a happy society? Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Peer, E., Vosgerau, J., & Acquisiti, A. (2014). Reputation as a sufficient condition for data quality on Amazon mechanical Turk. Behavior Research Methods, 46, 1023–1031.

Placher, W. C. (2005). Callings: Twenty centuries of Christian wisdom on vocation. Cambridge: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co..

Prochaska, J. O., Evers, K. E., Johnson, J. L., Castle, P. H., Prochaska, J. M., Sears, L. E., Rula, E. Y., & Pope, J. E. (2011). The well-being assessment for productivity: A well-being approach to presenteeism. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 53, 735–742.

Rich, B. L., LePine, J. A., & Crawford, E. R. (2010). Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 53, 617–635.

Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91–127.

Rothausen, T. J. (1994). Job satisfaction and the parent worker: The role of flexibility and rewards. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 44, 317–336.

Rothausen, T. J., Gonzalez, J. A., & Griffin, A. E. C. (2009). Are all the parts there everywhere? Facet job satisfaction in the United States and the Philippines. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 26, 681–700.

Rothausen, T. J., Henderson, K. E., Arnold, J. K., & Malshe, A. (2017). Should I stay or should I go? Identity and well-being in sensemaking about retention and turnover. Journal of Management, 43, 2357–2385.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68–78.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069–1081.

Scarpello, V., & Campbell, J. P. (1983). Job satisfaction: Are all the parts there? Personnel Psychology, 36, 577–600.

Schleicher, D. J., Hansen, S. D., & Fox, K. E. (2011). Job attitudes and work values. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, volume 3 (pp. 137–189). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Shenker, I. (1969). E.B. White: Notes and comment by author. New York Times, 37 & 43.

Shore, L. M., Randel, A. E., Chung, B. G., Dean, M. A., Holcombe Ehrhart, K., & Singh, G. (2011). Inclusion and diversity in work groups: A review and model for future research. Journal of Management, 37, 1262–1289.

Smith, P. C., Kendall, L. M., & Hulin, C. L. (1969). The measurement of job satisfaction in work and retirement. Chicago: Rand-McNally.

Sollinger, O. N., van Olffen, W., & Roe, R. A. (2008). Beyond the three-component model of organizational commitment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 70–83.

Super, D. E. (1990). A life-span, life-space approach to career development. In D. Brown & L. Brooks (Eds.), Career choice and development (2nd ed., pp. 197–261). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Tait, M., Padgett, M. Y., & Baldwin, T. T. (1989). Job and life satisfaction: A reevaluation of the strength of the relationship and gender effects as a function of the date of study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 502–507.

Warr, P. (2007). Work, happiness, and unhappiness. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Waterman, A. S. (1993). Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 678–691.

Weiss, D. J., Dawis, R. V., England, G. W., & Lofquist, L. H. (1967). Manual for the Minnesota satisfaction questionnaire. Minneapolis: Work Adjustment Project, Industrial Relations Center, University of Minnesota.

Weiss, H. M., & Rupp, D. E. (2011). Experiencing work: An essay on a person-centric work psychology. Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice, 4(1), 83–97.

Wildman, J. L., Bedwell, W. L., Salas, E., & Smith-Jentsch, K. A. (2011). Performance measurement at work: A multi-level perspective. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, volume 1 (pp. 303–341). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to colleagues who were helpful as the ideas in this research developed, and would especially like to thank John Budd, René Dawis, Angelo DeNisi, and Paul Sackett. We are also grateful to Chad Brinsfield, Sara Christenson, Jennifer George, Theresa Glomb, Annelise Larson, Christopher Michaelson, Anne O’Leary-Kelly, Ramona Paetzold, Caleb Williams, and members of the research workshop series at the Carlson School, University of Minnesota and Opus College of Business, University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, for helpful comments on earlier versions of this work. Separate elements of this paper were presented in August 2012 at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association and in April 2013 at the annual meeting of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Global and Facet Job Satisfaction (JS) and Meaning-Based Job-Related Well-Being (MJW) Measures

These items were used to measure global and facet JS and MJW in this research.

Global Measures

Please indicate how you have felt over the last few months to a year about these aspects of your job.

1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = slightly disagree; 4 = neither agree nor disagree; 5 = slightly agree; 6 = agree; 7 = strongly agree.

Global JS.

I am happy in my job