Abstract

Disgust-driven stigma may be motivated by an assumption that a stigmatized target presents a disease threat, even in the absence of objective proof. Accordingly, even non-contagious diseases, such as cancer, can become stigmatized by eliciting disgust. This study had two parts: a survey (n = 272), assessing the association between disgust traits and cancer stigma; and an experiment, in which participants were exposed to a cancer surgery (n = 73) or neutral video (n = 68), in order to test a causal mechanism for the abovementioned association. Having a higher proneness to disgust was associated with an increased tendency to stigmatize people with cancer. Further, a significant causal pathway was observed between disgust propensity and awkwardness- and avoidance-based cancer stigma via elevated disgust following cancer surgery exposure. In contrast, those exposed to cancer surgery not experiencing elevated disgust reported less stigma than controls. Exposure-based interventions, which do not elicit disgust, may be profitable in reducing cancer stigma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Health- or illness-related stigma can be conceptualised as a complex process involving exclusion, rejection, blame, or devaluation towards an individual or group perceived as “different” as a function of their health status (Marlow & Wardle, 2014). Stigma in chronic diseases, such as cancer, can have powerful detrimental effects on an individual’s psychological health through, for example, a heightened vulnerability to negative self-identification (e.g., Rosman, 2004), loss of emotional support (e.g., Bloom & Kessler, 1994), and increased psychological distress (e.g., Quinn & Chaudoir, 2009). Stigma also may have direct adverse consequences on patients’ physical health, and is associated with an increased risk of poor physical health outcomes (e.g., Cho et al., 2013). Stigma may discourage individuals from being tested or treated for the stigmatised disease or condition (e.g., Courtwright, 2009), cause diagnostic delay (e.g., Tod et al., 2008), and/or treatment discontinuation (e.g., Sirey et al., 2001).

The effects of health-related stigma can be particularly difficult for those with chronic diseases (Link & Phelan, 2006), such as cancer. Stigma has been shown to be one of the difficulties and challenges that cancer patients confront more often than some other illness groups (e.g., including diabetes, heart disease, and stroke; Albrecht et al., 1982; Berman & Wandersman, 1990). The strong and pervasive stigmatization of cancer patients may be due to the visible differences produced by cancer symptoms and the side-effects of treatment (e.g., hair loss and disfigurement; Costa et al., 2014; Powell et al., 2016; Rosman, 2004). Other contributory factors include cancer’s association with death and mortality (Knapp et al., 2014), and the belief that cancer is associated with, or caused by, patients’ behaviour (e.g., via a risky lifestyle; Threader & McCormack, 2016). The serious impacts of stigma underpin the aim of this paper, which is to explore the role of disgust, a health-related emotion, in stigma towards people with cancer.

Disgust: the disease avoidance emotion

Disgust is a universal human emotion (Ekman, 1992) that appears to have evolved primarily to motivate humans to avoid disease and maintain good health (Consedine & Moskowitz, 2007; Oaten et al., 2009). It is an extended form of the sensation of distaste, which guards against the consumption of potentially harmful substances (Rozin & Fallon, 1987), and evolved into an emotion that protects the body border against broader (i.e., non-oral) pathogenic threats (Curtis et al., 2004). The disgust emotion has since been co-apted to promote the condemnation, avoidance, and rejection of certain sociomoral transgressions (e.g., violations of purity norms; Chapman & Anderson, 2012).

Known as the “disease-avoidance emotion” (Curtis et al., 2011), disgust has been argued to be the affective component of humans’ “behavioural immune system” (Stevenson et al., 2009), which motivates avoidance of stimuli that might result in illness or contamination (Neuberg et al., 2011; Schaller & Park, 2011). People report much greater disgust to stimuli linked to disease transmission, for example (Curtis et al., 2004). As a protector of health, however, the disgust response is to some extent imprecise and causes false alarms, where the perceptions of a threat to health can occur (or persist) in the absence of an objective threat (e.g., Nemeroff & Rozin, 1994; Reynolds et al., 2013). Stimuli that either have been in contact with, or imitate features of, stimuli that could make us unwell can elicit disgust (i.e., the “law of contagion” and “law of similarity”; Rozin et al., 1999). Thus, while many people with infectious diseases are more prone to being stigmatized (Schaller, 2011), this effect extends to non-contagious diseases, including cancer (Fife & Wright, 2000), that mimic the signs of infectious disease (e.g., via distinguishing features such as hair loss, handicap, etc.; Goffman, 1963; Rosman, 2004).

Disgust and disease stigma

Research has revealed that disgust reactions may be predictive of stigma. Disgust propensity (DP), an individual’s underlying proneness to be disgusted (van Overveld et al., 2006), has been found to have a significant link with negative attitudes toward obese people (e.g., Vartanian, 2010), and is associated with greater prejudice and stigma towards homosexuality (e.g., Inbar et al., 2009; Olatunji, 2008). Disgust propensity has also been found to demonstrate positive correlations with negative outgroup evaluations (e.g., Hodson et al., 2013; Navarrete & Fessler, 2006) and opposition to immigration (e.g., Aarøe et al., 2017). Previous work has also linked DP to wanting less contact with non-cancer specific colostomy patients and with self-perceived stigma (e.g., Smith et al., 2007). Moreover, a complementary body of experimental research has demonstrated causal effects of disgust on avoidance (a behavioural component of stigma) in relevant health contexts. These include avoidance and delay of help-seeking for colorectal cancer (Reynolds et al., 2014) and sexual health (McCambridge & Consedine, 2014) symptoms, and a disgust-induced social avoidance of people with bowel problems (Reynolds et al., 2015).

Only minimal research, however, has explored disgust as a predictor of stigma towards chronic diseases, such as cancer, directly, and much of this is cross-sectional survey work, making it difficult to determine the causal relationship between disgust and stigma. Perhaps the closest prior work is by Pryor et al. (2004). As part of a wider investigation, Pryor et al. (2004) showed that DP was associated with avoidance reactions to a composite of stigmatized health conditions, including HIV, AIDS, obesity, and cancer, in a computerised behavioural task. However, individual effects on cancer were not explored in this study. Furthermore, the study did not include an experimental manipulation, control for bidirectional effects of existing stigma responses on disgust, or test a causal mechanism for the findings. Accordingly, the causal role that disgust traits may have in predicting the stigmatization of people with cancer (i.e., via heightened state disgust reactions) remains to be empirically demonstrated. Given that stigma is complex and has multiple correlates, there is a need for more experimental studies to illuminate causality here (e.g., Reynolds et al., 2014, 2015). In this paper, we are interested in modelling a causal pathway, from trait disgust to state disgust reactions to cancer stigma, using complementary survey and experimental exposure methods.

A final oversight in prior work is a focus on DP at the expense of other sorts of systematic individual differences in responses to disgust stimuli. In particular, as well as DP, individuals show variation in disgust sensitivity (DS; how unpleasant the experience of disgust is to the individual, Curtis et al., 2011). To the authors’ knowledge, DS has not yet been assessed in relation to stigma. Therefore, assessing disgust sensitivity alongside DP in the current research is of importance for at least two reasons. First, DP and DS are correlated traits (van Overveld et al., 2006), and previous studies that have estimated the effects of DP in the absence of DS may have overestimated the unique contribution of the former in its relationship with stigma. Second, while possessing high levels of either of the disgust traits may have a causal role in increasing cancer stigma by influencing the frequency and/or intensity of state disgust reactions (e.g., Deacon & Olatunji, 2007), it is possible that DP and DS may have differential effects on cancer stigma, with one being more important than the other (see e.g., Azlan et al., 2017). This issue is thus worthy of investigation.

The current report

Despite the compelling rationale outlined above, there has been relatively little research into the role of disgust traits and stigma in cancer. Furthermore, the direction and nature of causality in the relationship is unclear, that is, if disgust traits cause increased stigma or if the reverse is true, promoting a need for experimental work. In the present paper, we tested the link between disgust traits and multifaceted cancer stigma in a two-phase study, with a survey and experimental component. Phase 1 was an exploratory study designed to establish the links between dispositional disgust traits (DP and DS) and several dimensions of stigma towards people with cancer. Phase 2 was designed to examine a potential causal mechanism (state disgust) between disgust traits and awkwardness- and avoidance-based cancer stigma, through an experimental study. In particular, following prior work that has demonstrated a moderating role for trait disgust on people’s disgust-related responding (e.g., Fleischman et al., 2015; Reynolds et al., 2014), we wanted to test whether people more prone (or sensitive) to disgust would respond with greater disgust in response to cancer-relevant disgust-eliciting stimuli and whether this would lead to greater stigma. Four main predictions were tested:

Predictions for phase 1 (survey)

-

1.

Based on past research (e.g., Inbar et al., 2009; Olatunji, 2008; Vartanian, 2010), we hypothesized that individuals with a higher DP would report greater stigma towards people with cancer. No prior work has investigated the effect of DS on stigma; however, given its association with DP, we hypothesised that this would be associated with greater cancer stigma.

-

2.

We also explored the non-directional hypothesis that the size of the associations between DP and stigma and DS and stigma would differ significantly.

Predictions for phase 2 (experimental)

-

3.

We hypothesised that exposure to disgust-eliciting cancer-relevant stimuli (i.e., watching a cancer surgery video) would invoke greater disgust than neutral (control) stimuli, which would lead to increased avoidance- (e.g., Curtis et al., 2011) and awkwardness- (e.g., Reynolds et al., 2015) based cancer stigma responses.

-

4.

Combining (1) and (3), we predicted that DP and DS would have a causal effect on avoidance- and awkwardness-based stigma by moderating (increasing) the effect of the cancer video on state disgust.

Phase 1: Survey study

Methods

Participants

Two hundred and seventy-two participants were opportunity sampled online. Most participants were women (n = 196), with ages ranging from 18 to 67 years (M = 26.72, SD = 10.71). No participants reported having had a diagnosis of cancer. The participants were recruited from the host university’s volunteers list and adverts on several online recruitment pages, including “Call for Participants” (https://callforparticipants.com) and “Psychology Research on the Net” (https://psych.hanover.edu/research/exponnet.html). As many participants as possible were recruited within the study recruitment window. Using G*Power 3.1.9.4 (Faul et al., 2007), a post hoc power analysis showed that a sample of 272 participants had 75% power to detect a significant regression coefficient (α = .05) with a small effect size (f2 = .02) and over 99.9% power to detect a medium effect (f2 = .15).

Measures

Disgust propensity and sensitivity

Participants’ overall DP and DS were measured using the 16-item Disgust Propensity and Sensitivity Scale-Revised (DPSS-R; van Overveld et al., 2006). The measure uses a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = always). Example items include: “I avoid disgusting things” (DP) and “When I notice I feel nauseous, I worry about vomiting” (DS). Based on psychometric evaluations of the DPSS-R (Goetz et al., 2013; Olatunji et al., 2007b), a recommended revised 10-item solution (four items for DS and six items for DP) was used for analyses. The Cronbach’s alphas were α = .77 for DS and α = .81 for DP.

We also measured participants’ DP to three different types of disgust elicitors (“core”, “animal-reminder”, and “contamination-based” disgust) using the 25-item Disgust Sensitivity Scale-Revised (DS-R; Haidt et al., 1994; modified by Olatunji et al., 2007a). Results using these sub-domain scores, rather than the overall DP measure, are presented in the Supplementary Materials (Appendix A) for interested readers.

Cancer stigma

Participants completed the 25-item Cancer Stigma Scale (CASS; Marlow & Wardle, 2014), which assesses multiple aspects of cancer stigma including: awkwardness (5-items, e.g. “I would find it hard to talk to someone with cancer”); severity (5-items, e.g. “Getting cancer means having to mentally prepare oneself for death”); avoidance (5-items, e.g. “If a colleague had cancer I would try to avoid them”); policy opposition (4-items, e.g. “The needs of people with cancer should be given top priority”); personal responsibility (4-items, e.g. “If a person has cancer it’s probably their fault”); and financial discrimination (3-items, e.g. “It is acceptable for insurance companies to reconsider a policy if someone has cancer”). Responses for each item were made on a 6-point Likert scale (1 = disagree strongly, 6 = agree strongly). Cronbach’s alpha scores were: severity: α = .66; personal responsibility: α = .88; awkwardness: α = .82; avoidance: α = .81; financial discrimination: α = .73; and policy opposition: α = .74.

Demographic questions

Participants were asked about their age, gender (0 = female, 1 = male), ethnicity (recoded as 0 = not White British, 1 = White British), and education (highest level completed: 1 = Secondary Education or equivalent, 2 = Undergraduate Degree or equivalent, 3 = Masters Degree or equivalent, 4 = PhD or equivalent).

Procedure

Ethical approval was granted by the host institution prior to data collection. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. In the first instance, the link to the URL and the corresponding password were e-mailed to participants. To minimize response bias, participants were informed that the aim of the study was to investigate their attitudes towards health, and the full objectives of the study were only disclosed in the debriefing. Participants were informed at the consent stage in the survey that they may be contacted after 3 days to take part in a related study (Phase 2) and were required to leave their email addresses if they consented to this. A prize draw of £100 was offered for those who completed both study phases. In Phase 1, participants completed the demographics questions and the measures outlined above in a counterbalanced order.

Data analysis

Following descriptive and correlational analyses in SPSS v. 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, US), multiple regression analyses were conducted on AMOS v. 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, US) to examine the predictive association of DP and DS with cancer stigma, and the difference between the DP and DS coefficients. Bootstrapping was used to account for data with a non-normal distribution. Bootstrapping provides a non-parametric robust alternative to parametric estimates when the assumptions of those methods may be violated (e.g., Fox, 2008). The significance of all regression path coefficients was assessed by computing bias-corrected and accelerated bootstrap estimates with 95% confidence intervals (BCa 95% CIs). This technique was utilised because it performs optimally with regard to statistical power and type I error rates compared to other methods (Efron, 1987). Ten thousand resamples were used for the bootstrapped estimates (Mallinckrodt et al., 2006). Age, gender, education, and ethnicity were included as potential observed confounds in all regression models.

Results

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among the disgust and stigma variables are presented in Table 1. Central to the interests of this paper was whether disgust had a significant link with cancer stigma. Initial correlational analyses showed that there were significant associations between DP with most of the study variables. In particular, DP had significant positive associations with most of the CASS subscales: severity, r = .27, p < .001, awkwardness, r = .30, p < .001, and avoidance, r = .15, p = .013. However, there was no significant correlation of DP with responsibility, discrimination, or policy opposition stigma. DS was found to significantly correlate only with severity-based stigma, r = .13, p = .033.

In the multiple regression models (Table 2), DP was found to be independently positively associated with severity, β = .26, p < .001, awkwardness, β = .33, p < .001, and avoidance, β = .16, p = .009. However, there were no significant associations of DP with responsibility, discrimination, and policy opposition stigma. Disgust sensitivity was not independently associated with any of the outcomes. Disgust propensity had a significantly larger association than DS with awkwardness-based stigma, Δβ = .39, p = .002, and a borderline significant greater association with severity-based stigma, Δβ = .25, p = .052.

Discussion

Phase 1 of the study established that disgust traits have significant links with particular dimensions of stigma towards people with cancer, including awkwardness and avoidance. These findings support part of prediction (1), that individuals with a higher DP would report increased stigma towards people with cancer, and confirm previous findings (e.g., from Pryor et al., 2004). These findings are also consistent with prior research demonstrating positive links between DP and negative attitudes towards marginalised outgroups, including obese people (e.g., Vartanian, 2010), homosexuals (e.g., Inbar et al., 2009; Olatunji, 2008), and immigrants (e.g., Aarøe et al., 2017). The present findings also show for the first time that DS (a trait related to, but independent from, DP) is not as important as DP in understanding individuals’ propensity to cancer stigma. In particular, even after controlling for DS, DP had a significant independent association with three dimensions of stigma, while DS did not. Furthermore, in partial support of prediction (2), DP had a significantly stronger effect than DS in one of these dimensions (awkwardness) and a borderline significantly larger effect in another (severity).

These findings suggest that how easily people are disgusted may be more important for understanding cancer stigma than the extent to which people find the experience of disgust aversive (see e.g., van Overveld et al., 2006). While further work may be necessary to elucidate these results, one interpretation is that individual differences in the threshold required for cancer to elicit disgust matters for understanding disgust-driven cancer stigma. In particular, not everyone will find cancer (and the stimuli they associate with it) disgusting, and those that do not will not be impacted by the extent of their sensitivity to the disgust experience. Disgust sensitivity appears to play a stronger role in situations where disgust is universally experienced, such as avoiding vomit within emetophobia (or a fear of vomiting; van Overveld et al., 2008). Further, people who have higher disgust propensity may exhibit stigma by wanting to avoid interactions with people with cancer that they find potentially disgust-provoking. Previous research has shown that disgust propensity is a better overall predictor of behavioural avoidance than disgust sensitivity (van Overveld et al., 2010).

Disgust responses (in the form of DP) were associated with certain types of stigma and not others. This pattern of associations makes sense, as DP was most strongly associated with dimensions of stigma that have been theoretically and empirically linked to disgust, including the associated behavioural response of avoidance (e.g., Reynolds et al., 2015); awkwardness around others with disease, including reduced approach and interactive behaviour (Hodson et al., 2013); and severity, which includes themes of death (i.e., “Getting cancer means having to mentally prepare oneself for death”) and irreversible contamination (i.e., “Once you’ve had cancer you can never be ‘normal’ again”). These effects did not extend to other, less-related, and arguably more cognitive, forms of stigma, including perceived responsibility, financial discrimination, and policy opposition.

These findings support the idea that stigma may be associated with a conservative defence against disease (via disgust responding), and individuals or situations that might result in contamination (e.g., Neuberg et al., 2011; Oaten et al., 2011; Schaller & Park, 2011). However, a significant limitation of Phase 1 is that it only demonstrates associational relationships between DP and cancer stigma. In addition to the hypothesised pathway, there are a number of possible reasons why covariation between these negative constructs could exist, including, for example, heightened trait affectivity. Therefore, in the next phase of the work we sought to examine a potential causal mechanism between the two constructs through an experimental paradigm. This experimental study aimed to explore the effect of being exposed to disgust-related cancer stimuli on reported avoidance- and awkwardness-based stigma, through the level of reported state disgust experienced, as a function of participants’ underlying disgust traits. Avoidance—(Curtis et al., 2011; Pryor et al., 2004) and awkwardness—(Hodson et al., 2013) based reactions are commonly theoretically and empirically linked to disgust and thus were deemed relevant to focus on as an experimental outcome variable. They also have clear implications for behaviour, and were found to be significantly related to DP in Phase 1 (along with severity).

Mediation and moderated-mediation path analyses were used to test the central interests in Phase 2 of the study. These were: (a) to test experimentally a causal effect of exposure (i.e., exposure to disgust-related cancer stimuli) on stigma towards people with cancer, through reported state disgust responses; and (b) provide insight into the psychological mechanism explaining how individuals’ DP may lead to greater avoidance and awkwardness-based stigma via state disgust.

Phase 2: Experimental study

Methods

Participants

One hundred and forty-one participants were recruited from the sample in Phase 1. To ensure that a balanced number of subjects from various subgroups were selected, participants were stratified based on their age, gender, and DP scores, and then randomized to the experimental (cancer surgery video; n = 73) or control (neutral video, n = 68) condition. Most participants were women (n = 103), and participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 65 years (M = 27.45 SD = 10.15). The study had greater than 80% power (as recommended by Cohen, 1992) to detect a significant regression coefficient (α = .05) of a small-to-medium size (f2 = .05).

Measures

Avoidance- and awkwardness-based stigma

In order to index experimentally-induced variation in stigma we designed a brief, 4-item Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) measure to use as the dependent variable (see Appendix B in the Supplementary Materials) adapted from the Cancer Stigma Scale (CASS; Marlow & Wardle, 2014). To make a brief VAS measure, suitable for use in an experimental paradigm, 4 items from 10 were randomly selected from the awkwardness and avoidance behaviour subscales. The four items included were: “Responding honestly, I would try to avoid a person with cancer”, “I would find it difficult being around someone with cancer”, “I would find it hard to talk to someone with cancer”, and “I would distance myself physically from someone with cancer”. Participants responded to each stem on a 100-point VAS (e.g., 0 = not at all, 100 = extremely so), and a mean score was calculated. Factor analysis on these items revealed that they best loaded together as one factor (see Appendix C in the Supplementary Materials). The Cronbach’s alpha score for this measure was .85. This 4-item measure was designed to minimise participant burden, while maximising variance through the use of a 100-point VAS.

State emotion

In order to measure state disgust, a VAS (adapted from Powell et al., 2015) was used to record how much disgust participants felt after watching the videos. As a manipulation check, participants also completed VASs for four other basic emotions (anger, sadness, fear, and happiness) after watching the videos (see Appendix D in the Supplementary Materials). For each emotion, participants responded to the stem: “Responding honestly, how disgusted/angry/sad/afraid/happy did the video make you feel” on a 100-point VAS (e.g., 0 = not at all, 100 = extremely).

Control variables

In order to better test the causal effect of exposure on state-reported stigma, participants’ pre-existing level of stigma towards people with cancer (the combined scores of the 4-items on the CASS in Phase 1 that were used as the VAS stigma scale) was included as a covariate in the model.

Experimental stimuli

We intended to select cancer-relevant disgust stimuli to reflect the proposed causal mechanism by which proneness to disgust might predict cancer stigma (i.e., via the disgust-induced by cancer stimuli). A pilot study, with an independent sample (n = 10), was conducted to select suitable videos for the experimental study. The link to the URL and the corresponding password were e-mailed to ten postgraduate students in psychology. Participants were asked to watch three freely-available videos thought a priori to be cancer-relevant and disgust eliciting (ovarian cancer surgery, https://youtu.be/SGV70h5ZFTM; liver cancer surgery, https://youtu.be/1J4kdRuHVeg; and ostomy care, https://youtu.be/LxkFTbQMvGo), and another three neutral videos (static traffic cone, https://youtu.be/pEll1YpSunc; crawling snail, https://youtu.be/VaLGV-SBTmc; and dripping tap, https://youtu.be/33NOQV0Soz8). All videos were approximately three minutes long.

The videos were administered in a counter-balanced order using Qualtrics. Emotion VASs were recorded (as described above). One additional scale assessing the distress level of each of the videos was also included. Based on the results of this study (see Appendix E in the Supplementary Materials), the video which had been rated with the highest disgust rating was chosen for the experimental condition (ovarian cancer surgery), and the least disgusting video was chosen for the control condition (static traffic cone).

Procedure

All Phase 1 participants who had left their contact details for further participation were invited to take part. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Participants were exposed to a cancer surgery video or a neutral video through a Qualtrics link, which was sent by email three days after their survey study. In order to ensure their attention and engagement with the videos, the participants were told that they would be asked a few memory questions related to the videos after watching them (e.g., “what was the human organ involved in the surgery?”), on which they did not receive feedback. Participants then completed the VAS emotion measures and VAS stigma scale after they watched the video. Finally, a positive video was offered to participants in the experimental condition to help counterbalance the inherent negativity of the video (happy baby, https://youtu.be/bMME3wyB1zQ). Participants were then debriefed.

Data analysis

Following manipulation checks, path analysis with AMOS v. 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, US) was used to model the hypothesised causal relationships between the variables (i.e., mediation and moderated mediation models). Path analysis has several advantages over standard multiple regressions, including the estimation of direct and indirect effects (through mediating variables) simultaneously.

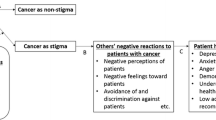

An initial mediation model tested prediction (3), that exposure to disgust-related cancer stimuli (i.e., cancer surgery) would invoke state disgust responses, which would lead to increased stigma. Variables included were experimental condition, DP, DS, and T1 Stigma as exogenous predictors, disgust response as a hypothesized mediator, and VAS stigma as an outcome (see Fig. 1). In this model, parameter weights on condition*DP and condition*DS interaction terms were constrained to zero.

Moderated mediation model between Condition and VAS Stigma via VAS disgust. Propensity to disgust significantly moderated the effect of condition on VAS disgust, β = .26, p < .01, and thus the strength of the causal mediational pathway of condition on VAS stigma via VAS disgust. Correlations between exogenous predictors and error terms omitted for clarity. The estimates in the brackets represent the estimates in the mediation model (with interaction terms constrained to 0). All estimates are standardised betas (β). Significance levels were determined based on bootstrapped CIs (10,000 resamples). DP = disgust propensity; DS = disgust sensitivity; T1 stigma = trait stigma composite in Phase 1. Asterisked coefficients are significant at †p < .10; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001

A moderated mediation model tested prediction (4), that DP or DS would have a causal effect on stigma by heightening (moderating) the level of disgust participants experienced as a consequence of exposure to disgust-related cancer stimuli. In this model the parameter constraints on the condition*DP and condition*DS interaction terms were removed. We included baseline (T1) stigma in the models to provide a stronger test of the experimental hypothesis (that cancer-relevant disgust exposure causes changes in stigma). Similar, stronger effects were observed if T1 Stigma was omitted from the models (for model estimates see Appendix F in the Supplementary Materials).

As in Phase 1, bootstrapping was used to estimate CIs and corresponding probability estimates, and to test the significance of indirect effects (Hayes & Scharkow, 2013). To allow for inter-variable comparisons, prior to the analysis, continuous scores were standardised based on Gelman (2008), where each numeric variable was centred and divided by two times its standard deviation, (comparable to an equally distributed binary variable). This also facilitated the use of an interaction term without any problematic multicollinearity.

Results

Randomisation and manipulation checks

Experimental and neutral condition participants did not significantly differ on gender, χ2 (1) = 0.02, p = .901, Φ = .01; and age, t(139) = 0.52, p = .604, d = 0.09. Moreover, there were no significant group differences in DP, t(139) = − 1.02, p = .309, d = 0.17, or DS, t(139) = -− .93, p = .356, d = 0.16. Thus, the randomisation of these characteristics between the two conditions was successful. Those in the experimental condition reported significantly more disgust (M = 42.52, SD = 30.72) than those in the control condition (M = 2.04, SD = 3.70), t(74.24) = 11.17, p < .001, d = 1.85. However, there were also, smaller, significant differences in the other emotions, potentially due to shared variance in the affective states. Accordingly, to calculate which emotion VASs were independently affected by the induction, a binary logistic regression was conducted, with all five emotion VASs regressed on group membership. The model was significant, χ2(5) = 146.13, p < .001, explaining 86.1% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in group membership, correctly classifying 94.3% of cases. Group membership was independently explained by levels of disgust, b = 0.42, p < .001, anger, b = -0.48, p < .001, sadness, b = 0.15, p = .026, and happiness, b = 0.04, p = .024, but not fear, b = -0.06, p = .173. Contrary to predictions, those in the experimental condition (M = 11.79, SD = 14.85) reported significantly lower stigma, on average, than those in the control condition (M = 17.59, SD = 17.69), t(131.235) = − 2.10, p = .038, d = 0.36.

Path model

The model fit for the mediation model was χ2(6) = 25.68, p < .001, CFI = .958, RMSEA = .15, BCa 95% CI [.10, .22], p = .003. The model explained 52.4% of the variance in VAS disgust and 48.2% in VAS stigma. Being in the experimental condition had a direct negative effect on reported stigma, β = − .22, p = .002, and a direct positive effect on experienced disgust, β = .71, p < .001. State disgust had a significant direct effect on reported stigma, β = .20, p = .011. Accordingly, a significant positive indirect effect of condition on stigma was observed via experienced disgust, βab = .14, p = .011.

The model fit for the moderated mediation model was χ2(4) = 6.47, p = .167, CFI = .995, RMSEA = .07, BCa 95% CI [.00, .16], p = .312, fitting significantly better than the mediation model, Δχ2 (2) = − 19.21, p < .001. The interaction between experimental condition and DP significantly predicted VAS disgust, β = .26, p = .001, and had a significant indirect effect on VAS stigma via experienced disgust, β = .05, p = .008. Key path estimates and bootstrap SEs/CIs are presented in Table 3.

To clarify further the nature of the moderating effect, the effect of experimental condition on stigma via experienced disgust was estimated at three levels of DP, at two standard deviations below the mean (low), at the mean (moderate), and two standard deviations above the mean (high). Simple slopes analysis revealed that experimental assignment had a stronger indirect effect on VAS stigma, through experienced disgust, at higher levels of DP, with significant indirect effects at high, β = .22, p = .012, moderate, β = .14, p < .001, and low, β = .07, p = .008, levels of DP.

Discussion

The primary findings from this experiment were that participants in the experimental condition who were exposed to the cancer surgery video were more likely to experience greater disgust. Those experiencing greater disgust were also more likely to report greater avoidance- and awkwardness-based cancer stigma. Furthermore, this mediation effect was moderated by trait DP: those with greater DP experienced greater disgust in response to the cancer surgery video, which led to a greater tendency for stigma towards people with cancer, even while controlling for prior levels of stigma reported in the Phase 1 survey. Interestingly, exposure to the cancer surgery video per se otherwise appeared beneficial, having a significant negative direct effect on reported VAS stigma.

These results establish a potential causal role for DP in heightening cancer stigma by moderating the extent of disgust reactions to disgust-relevant cancer-related stimuli. They extend previous work on disgust and negative attitudes (e.g., Inbar et al., 2009; Olatunji, 2008), specifically towards people with chronic diseases (Pryor et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2007; Vartanian, 2010). We found support for prediction (4), that DP moderated state disgust in response to cancer stimuli, which lead to increased avoidance- and awkwardness-based cancer stigma responses. However, the positive effect of experimental exposure on stigma (in the absence of a heightened disgust pathway) goes contrary to our initial prediction (3), as we discuss in the General Discussion below.

General discussion

The present research examined the role of disgust in the stigmatization of people with cancer. Findings of Phase 1 provided support for the idea that trait disgust (in the form of disgust propensity [DP]) had significant cross-sectional links with particular dimensions of stigma towards people with cancer, including avoidance- and awkwardness-based stigma. Phase 2 demonstrated the validity of a potential causal pathway for DP to act on cancer stigma via moderation of the experiential state disgust reactions following exposure to disgust-associated cancer stimuli.

This study addressed significant gaps in the literature and has at least three valuable implications to assist with the development of effective interventions for reducing stigma towards people with cancer. First, the findings suggest that trait disgust matters in understanding cancer stigma. While relatively stable over time, trait DP is malleable, and may be altered via habituation with repeated (positive) exposure over time, particularly within specific domains (e.g., Athey et al., 2015; Rozin, 2008). Further, in attempting to reduce cancer stigma, potentially reducing available triggers for disgust in communications about cancer may be beneficial. In supplementary domain specific analyses (see Appendix A in the Supplementary Materials), the moderating effect of DP was driven via “animal-reminder” disgust. This suggests that one possible way in reducing stigma might be to reduce the exposure to reminders of mortality through an increased awareness that cancer is a survivable disease (e.g., Greene & Adelman, 2003; Scheel et al., 2017). Other counter-disgust messages are possible, including emphasising that cancer is not contagious (as perceived transmissible disease is a trigger of disgust; Curtis et al., 2004). Such content could be incorporated within broader public awareness campaigns or messages designed to reduce cancer stigma.

Second, given the key role of state disgust in explaining the link between DP and reported stigma, methods of reducing state disgust after exposure to disgust-relevant cancer stimuli may be important. It has been suggested that activated compassion (Gilbert, 2010) may promote acceptance and reduce disgust and threat systems in humans, and so inducing compassion in individuals also may be a solution to reduce stigma, by inducing incompatible or contrasting positive emotional reactions, as has been applied in relaxation therapy for anxiety (e.g., Pagnini et al., 2013). Indeed, a recent experimental study showed that induced compassion may offset the disengagement in health care providers otherwise produced by patients with disgusting symptoms (Reynolds et al., 2019). Promoting positive emotions and minimising stigma is also a relevant concern for public awareness campaigns that, for example, seek to use disgust-based content to discourage health behaviour linked to cancer. An example of this is the disgust content that features in anti-smoking campaigns, which may inadvertently heighten disgust-based stigma for people with cancer types linked to smoking (Lupton, 2015).

As a complementary approach, efforts to reduce stigma may centre on processing negative emotions directly, such as by adapting in interventions the procedures used in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), which has proven effective in previous studies (e.g., Luoma & Platt, 2015; Masuda et al., 2007; Skinta et al., 2015). For example, Masuda et al. (2007) showed that an ACT workshop was more effective than education alone, in reducing mental health stigma in students. The ACT workshop involved a number of complementary stages, including exercises for participants to notice how judgemental processes are automatic, prevalent and related to mental health stigma; the use of data (evidence) to normalise psychological struggles; exercises focusing on empathy and parallel reactions to others versus the self; training in acceptance and non-judgemental skills; and a behavioural commitment to the area of interpersonal relationships. Similar techniques could be adapted for use in addressing disgust-induced cancer stigma. Further, considering the intense negative affective experience, training in distress tolerance or emotion regulation (Gayner et al., 2012), which has proven effective in reducing self-stigma, may be potentially useful for individuals with pronounced disgust, in combating external stigma.

Third, an interesting finding from this study is that, in the absence of disgust, exposure to a disgust-relevant cancer surgery video induced less reported stigma relative to those exposed to a neutral video, when controlling for prior levels of stigma. Therefore, exposure to cancer-relevant stimuli without an accompanying disgust reaction may be effective for reducing stigma. A number of explanatory possibilities are relevant here, including that participants experienced empathetic and prosocial reactions, including compassion and sympathy, in response to the cancer surgery video. Alternatively, the video may have conferred some educational benefits for participants on a cancer patient’s experience. The result also validates previous work and psychological therapies that incorporate exposure in reducing stigma (e.g., positive interpersonal contact with transgender individuals is associated with lower sexual stigma and prejudice, Walch et al., 2012). This also may suggest that exposure could be beneficial in reducing stigma towards people with cancer, in the absence of disgust or related negative emotions (e.g., through the implementation of graded exposure or incompatible positive emotions, such as compassion or relaxation). The gradual exposure-based interventions (which are based on the systematic exposure to the feared stimulus, either in the imagination or real contact), for instance, may help individuals down-regulate negative emotion while learning to tolerate provocative unpleasant emotion-inducing stimuli, until the negative feeling decreases and eventually extinguishes (e.g., Grecucci et al., 2015).

Limitations and ideas for future research

One limitation of this present study is that it is based on self-reported levels of disgust and stigma, rather than observed behaviour. Accordingly, there is the possibility of bias between what participants’ self-report and what would be observed behaviourally (i.e., in behavioural tests of stigmatization). Alternative methods may be considered that involve behavioural assessments of avoidance-based stigma, such as a Behavioural Avoidance Task (e.g., Reynolds et al., 2014). Nevertheless, self-report measures are often well-correlated with actual behaviour, and so should be considered indicative of what may be expected in behavioural studies (e.g., Wash et al., 2017). Second, the stimuli used to elicit disgust in Phase 2 (i.e., cancer surgery) may have more relevance to the animal-reminder disgust domain than other domains of disgust. Therefore, future research could potentially include broader stimuli that may elicit other domains of disgust (e.g., contamination threats via a dirtied stoma bag) to test for the versatility of effects. This may include tests of whether similar effects are observed using non-cancer-relevant disgust stimuli and experience states.

A third limitation arises from the lack of attention towards the underlying complex variation of stigma towards different cancer types. Certain cancer types may elicit different dimensions of stigma (e.g., lung cancer has been identified to be highly associated with responsibility stigma as its established link with smoking mean that it is perceived to be personally controllable; Marlow et al., 2015). Therefore, in future work, the causal path model could be expanded to examine stigma specific to cancer types. A further limitation in this study is, in the experimental phase, the work only focused on awkwardness- and avoidance-based stigma, which have been theoretically and empirically related to disgust. Future studies may involve extensions to more holistic or broader dimensions of stigma. A fifth limitation is the absence of a negative affect experimental control group in Phase 2 (e.g., an anxiety or embarrassment induction), which would allow an examination of whether the observed effects on stigma are specific to a disgust induction paradigm. Additional affective control groups could be incorporated in future work. Finally, the sample was predominantly female and so it is unclear whether similar effects would be seen in men, although the effects of gender on stigma in this study were small.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this is the first study to demonstrate a potential causal mechanism for underlying disgust traits to produce cancer stigma, through heightened state disgust reactions via cancer-relevant exposure (when controlling for prior levels of stigma). Disgust propensity but not DS seems uniquely relevant in understanding propensity to cancer stigma. These results help to understand the mechanisms and natural consequences of disgust as an overly-conservative behavioural immune system, which may lead to stigma towards people with chronic illnesses, such as cancer, via exposure to disgust-eliciting cancer stimuli. It is therefore suggested that efforts to reduce cancer stigma should put more emphasis on underlying DP as a predictor, and should focus on reducing state disgust following the exposure to cancer-relevant stimuli, to create more positive exposure experiences.

References

Aarøe, L., Petersen, M. B., & Arceneaux, K. (2017). The behavioral immune system shapes political intuitions: Why and how individual differences in disgust sensitivity underlie opposition to immigration. American Political Science Review,111, 277–294. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055416000770

Albrecht, G. L., Walker, V. G., & Levy, J. A. (1982). Social distance from the stigmatized: A test of two theories. Social Science and Medicine,16, 1319–1327. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(82)90027-2

Athey, A. J., Elias, J. A., Crosby, J. M., Jenike, M. A., Pope, H. G., Hudson, J. I., et al. (2015). Reduced disgust propensity is associated with improvement in contamination/washing symptoms in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders,4, 20–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocrd.2014.11.001

Azlan, H. A., Overton, P. G., Simpson, J., & Powell, P. A. (2017). Differential disgust responding in people with cancer and implications for psychological wellbeing. Psychology and Health,32, 19–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2016.1235165

Berman, S. H., & Wandersman, A. (1990). Fear of cancer and knowledge of cancer: A review and proposed relevance to hazardous waste sites. Social Science and Medicine,31, 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(90)90013-I

Bloom, J. R., & Kessler, L. (1994). Emotional support following cancer: A test of the stigma and social activity hypotheses. Journal of Health and Social Behavior,35, 118–133.

Chapman, H. A., & Anderson, A. K. (2012). Understanding disgust. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences,1251, 62–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06369.x

Cho, J., Smith, K., Choi, E. K., Kim, I. R., Chang, Y. J., Park, H. Y., et al. (2013). Public attitudes toward cancer and cancer patients: A national survey in Korea. Psycho-Oncology,22, 605–613. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3041

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin,122, 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

Consedine, N. S., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2007). The role of discrete emotions in health outcomes: A critical review. Applied and Preventive Psychology,12, 59–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appsy.2007.09.001

Costa, E. F., Nogueira, T. E., de Souza Lima, N. C., Mendonça, E. F., & Leles, C. R. (2014). A qualitative study of the dimensions of patients’ perceptions of facial disfigurement after head and neck cancer surgery. Special Care in Dentistry,34, 114–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/scd.12039

Courtwright, A. M. (2009). Justice, stigma, and the new epidemiology of health disparities. Bioethics,23, 90–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00717.x

Curtis, V., Aunger, R., & Rabie, T. (2004). Evidence that disgust evolved to protect from risk of disease. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences,271, 131–133. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2003.0144

Curtis, V., de Barra, M., & Aunger, R. (2011). Disgust as an adaptive system for disease avoidance behaviour. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences,366, 389–401. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0117

Deacon, B., & Olatunji, B. O. (2007). Specificity of disgust sensitivity in the prediction of behavioral avoidance in contamination fear. Behaviour Research and Therapy,45, 2110–2120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2007.03.008

Efron, B. (1987). Better bootstrap confidence intervals. Journal of the American Statistical Association,82, 171–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1987.10478410

Ekman, P. (1992). An argument for basic emotions. Cognition and Emotion,6, 169–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699939208411068

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods,39, 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Fife, B. L., & Wright, E. R. (2000). The dimensionality of stigma: A comparison of its impact on the self of persons with HIV/AIDS and cancer. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. https://doi.org/10.2307/2676360

Fleischman, D. S., Hamilton, L. D., Fessler, D. M. T., & Meston, C. M. (2015). Disgust versus lust: Exploring the interactions of disgust and fear with sexual arousal in women. PLoS ONE,10, e0118151. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0118151

Fox, J. (2008). Applied regression analysis and generalized linear models (2nd ed.). London: Sage.

Gayner, B., Esplen, M. J., DeRoche, P., Wong, J., Bishop, S., Kavanagh, L., et al. (2012). A randomized controlled trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction to manage affective symptoms and improve quality of life in gay men living with HIV. Journal of Behavioral Medicine,35, 272–285. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-011-9350-8

Gelman, A. (2008). Scaling regression inputs by dividing by two standard deviations. Statistics in Medicine,27, 2865–2873. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.3107

Gilbert, P. (2010). An introduction to compassion focused therapy in cognitive behavior therapy. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy,3, 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1521/ijct.2010.3.2.97

Goetz, A. R., Cougle, J. R., & Lee, H. J. (2013). Revisiting the factor structure of the 12-item Disgust Propensity and Sensitivity Scale–Revised: Evidence for a third component. Personality and Individual Differences,55, 579–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.04.029

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of a spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Grecucci, A., Theuninck, A., Frederickson, J., & Job, R. (2015). Mechanisms of social emotion regulation: From neuroscience to psychotherapy. In M. L. Bryant (Ed.), Handbook on emotion regulation: Processes, cognitive effects and social consequences (pp. 57–84). New York, NY: Nova Publishing.

Greene, M. G., & Adelman, R. D. (2003). Physician–older patient communication about cancer. Patient Education and Counseling,50, 55–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00081-8

Haidt, J., McCauley, C., & Rozin, P. (1994). Individual differences in sensitivity to disgust: A scale sampling seven domains of disgust elicitors. Personality and Individual Differences,16, 701–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(94)90212-7

Hayes, A. F., & Scharkow, M. (2013). The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychological Science,24, 1918–1927. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613480187

Hodson, G., Choma, B. L., Boisvert, J., Hafer, C. L., MacInnis, C. C., & Costello, K. (2013). The role of intergroup disgust in predicting negative outgroup evaluations. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology,49, 195–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2012.11.002

Inbar, Y., Pizarro, D. A., Knobe, J., & Bloom, P. (2009). Disgust sensitivity predicts intuitive disapproval of gays. Emotion,9, 435–439. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015960

Knapp, S., Marziliano, A., & Moyer, A. (2014). Identity threat and stigma in cancer patients. Health Psychology Open. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055102914552281

Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. C. (2006). Stigma and its public health implications. The Lancet,367, 528–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68184-1

Luoma, J. B., & Platt, M. G. (2015). Shame, self-criticism, self-stigma, and compassion in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Current Opinion in Psychology,2, 97–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2014.12.016

Lupton, D. (2015). The pedagogy of disgust: The ethical, moral and political implications of using disgust in public health campaigns. Critical Public Health,25, 4–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2014.885115

Mallinckrodt, B., Abraham, W. T., Wei, M., & Russell, D. W. (2006). Advances in testing the statistical significance of mediation effects. Journal of Counseling Psychology,53, 372–378. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.3.372

Marlow, L. A., Waller, J., & Wardle, J. (2015). Does lung cancer attract greater stigma than other cancer types? Lung Cancer,88, 104–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.01.024

Marlow, L. A., & Wardle, J. (2014). Development of a scale to assess cancer stigma in the non-patient population. BMC Cancer,14, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-14-285

Masuda, A., Hayes, S. C., Fletcher, L. B., Seignourel, P. J., Bunting, K., Herbst, S. A., et al. (2007). Impact of acceptance and commitment therapy versus education on stigma toward people with psychological disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy,45, 2764–2772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2007.05.008

McCambridge, S. A., & Consedine, N. S. (2014). For whom the bell tolls: Experimentally-manipulated disgust and embarrassment may cause anticipated sexual healthcare avoidance among some people. Emotion,14, 407–415. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035209

Navarrete, C. D., & Fessler, D. M. (2006). Disease avoidance and ethnocentrism: The effects of disease vulnerability and disgust sensitivity on intergroup attitudes. Evolution and Human Behavior,27, 270–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2005.12.001

Nemeroff, C., & Rozin, P. (1994). The contagion concept in adult thinking in the United States: Transmission of germs and of interpersonal influence. Ethos,22, 158–186. https://doi.org/10.1525/eth.1994.22.2.02a00020/full

Neuberg, S. L., Kenrick, D. T., & Schaller, M. (2011). Human threat management systems: Self-protection and disease avoidance. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews,35, 1042–1051. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.08.011

Oaten, M., Stevenson, R. J., & Case, T. I. (2009). Disgust as a disease-avoidance mechanism. Psychological Bulletin,135, 303–321. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014823

Oaten, M., Stevenson, R. J., & Case, T. I. (2011). Disease avoidance as a functional basis for stigmatization. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences,366, 3433–3452. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2011.0095

Olatunji, B. O. (2008). Disgust, scrupulosity and conservative attitudes about sex: Evidence for a mediational model of homophobia. Journal of Research in Personality,42, 1364–1369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2008.04.001

Olatunji, B. O., Cisler, J. M., Deacon, B. J., Connolly, K., & Lohr, J. M. (2007a). The disgust propensity and sensitivity scale-revised: Psychometric properties and specificity in relation to anxiety disorder symptoms. Journal of Anxiety Disorders,21, 918–930. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anxdis.2006.12.005

Olatunji, B. O., Williams, N. L., Tolin, D. F., Abramowitz, J. S., Sawchuk, C. N., Lohr, J. M., et al. (2007b). The Disgust Scale: Item analysis, factor structure, and suggestions for refinement. Psychological Assessment,19, 281–297. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.281

Pagnini, F., Manzoni, G. M., Castelnuovo, G., & Molinari, E. (2013). A brief literature review about relaxation therapy and anxiety. Body, Movement and Dance in Psychotherapy,8, 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/17432979.2012.750248

Powell, P. A., Azlan, H. A., Simpson, J., & Overton, P. G. (2016). The effect of disgust-related side-effects on symptoms of depression and anxiety in people treated for cancer: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Behavioral Medicine,39, 560–573. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-016-9731-0

Powell, P. A., Simpson, J., & Overton, P. G. (2015). Self-affirming trait kindness regulates disgust toward one’s physical appearance. Body Image,12, 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.-bodyim.2014.10.006

Pryor, J. B., Reeder, G. D., Yeadon, C., & Hesson-McInnis, M. (2004). A dual-process model of reactions to perceived stigma. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,87, 436–452. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.87.4.436

Quinn, D. M., & Chaudoir, S. R. (2009). Living with a concealable stigmatized identity: The impact of anticipated stigma, centrality, salience, and cultural stigma on psychological distress and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,97, 634–651. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015815

Reynolds, L. M., Consedine, N. S., & McCambridge, S. A. (2014a). Mindfulness and disgust in colorectal cancer scenarios: Non-judging and non-reacting components predict avoidance when it makes sense. Mindfulness,5, 442–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0200-3

Reynolds, L. M., Consedine, N. S., Pizarro, D. A., & Bissett, I. P. (2013). Disgust and behavioral avoidance in colorectal cancer screening and treatment: A systematic review and research agenda. Cancer Nursing,36, 122–130. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e31826a4b1b

Reynolds, L. M., Lin, Y. S., Zhou, E., & Consedine, N. S. (2015a). Does a brief state mindfulness induction moderate disgust-driven social avoidance and decision-making? An experimental investigation. Journal of Behavioral Medicine,38, 98–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-014-9582-5

Reynolds, L. M., McCambridge, S. A., Bissett, I. P., & Consedine, N. S. (2014b). Trait and state disgust: an experimental investigation of disgust and avoidance in colorectal cancer decision scenarios. Health Psychology,33, 1495–1506. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000023

Reynolds, L. M., McCambridge, S. A., & Consedine, N. S. (2015b). Self-disgust and adaptation to chronic physical health conditions: Implications for avoidance and withdrawal. In P. A. Powell, P. G. Overton, & J. Simpson (Eds.), The revolting self: Perspectives on the psychological, social, and clinical implications of self-directed disgust (pp. 75–88). London: Karnac.

Reynolds, L. M., Powell, P., Lin, Y. S., Ravi, K., Chung, C.-Y. K., & Consedine, N. S. (2019). Fighting the flinch: Experimentally induced compassion makes a difference in health care providers. British Journal of Health Psychology,24, 982–998. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12390

Rosman, S. (2004). Cancer and stigma: Experience of patients with chemotherapy-induced alopecia. Patient Education and Counseling,52, 333–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00040-5

Rozin, P. (2008). Hedonic ‘adaptation’: Specific habituation to disgust/death elicitors as a result of dissecting a cadaver. Judgment and Decision Making,3, 191–194.

Rozin, P., & Fallon, A. E. (1987). A perspective on disgust. Psychological Review,94, 23–41. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.94.1.23

Rozin, P., Haidt, J., McCauley, C., Dunlop, L., & Ashmore, M. (1999). Individual differences in disgust sensitivity: Comparisons and evaluations of paper-and-pencil versus behavioral measures. Journal of Research in Personality,33, 330–351. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1999.2251

Schaller, M. (2011). The behavioural immune system and the psychology of human sociality. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences,366, 3418–3426. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2011.0029

Schaller, M., & Park, J. H. (2011). The behavioral immune system (and why it matters). Current Directions in Psychological Science,20, 99–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721411402596

Scheel, J. R., Molina, Y., Anderson, B. O., Patrick, D. L., Nakigudde, G., Gralow, J. R., et al. (2017). Breast cancer beliefs as potential targets for breast cancer awareness efforts to decrease late-stage presentation in Uganda. Journal of Global Oncology,4, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JGO.2016.008748

Sirey, J. A., Bruce, M. L., Alexopoulos, G. S., Perlick, D. A., Raue, P., Friedman, S. J., et al. (2001). Perceived stigma as a predictor of treatment discontinuation in young and older outpatients with depression. American Journal of Psychiatry,158, 479–481. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.479

Skinta, M. D., Lezama, M., Wells, G., & Dilley, J. W. (2015). Acceptance and compassion-based group therapy to reduce HIV stigma. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice,22, 481–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2014.05.006

Smith, D. M., Loewenstein, G., Rozin, P., Sherriff, R. L., & Ubel, P. A. (2007). Sensitivity to disgust, stigma, and adjustment to life with a colostomy. Journal of Research in Personality,41, 787–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.09.006

Stevenson, R. J., Case, T. I., & Oaten, M. J. (2009). Frequency and recency of infection and their relationship with disgust and contamination sensitivity. Evolution and Human Behavior,30, 363–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2009.02.005

Threader, J., & McCormack, L. (2016). Cancer-related trauma, stigma and growth: the ‘lived’experience of head and neck cancer. European Journal of Cancer Care,25, 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12320

Tod, A. M., Craven, J., & Allmark, P. (2008). Diagnostic delay in lung cancer: a qualitative study. Journal of Advanced Nursing,61, 336–343. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04542.x

van Overveld, M., de Jong, P. J., & Peters, M. L. (2010). The disgust propensity and sensitivity scale–revised: Its predictive value for avoidance behavior. Personality and Individual Differences,49, 706–711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.06.008

van Overveld, M., de Jong, P. J., Peters, M. L., Cavanagh, K., & Davey, G. C. L. (2006). Disgust propensity and disgust sensitivity: Separate constructs that are differentially related to specific fears. Personality and Individual Differences,41, 1241–1252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.04.021

van Overveld, M., de Jong, P. J., Peters, M. L., van Hout, W. J. P. J., & Bouman, T. K. (2008). An internet-based study on the relation between disgust sensitivity and emetophobia. Journal of Anxiety Disorders,22, 524–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2007.04.001

Vartanian, L. R. (2010). Disgust and perceived control in attitudes toward obese people. International Journal of Obesity,34, 1302–1307. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2010.45

Walch, S. E., Sinkkanen, K. A., Swain, E. M., Francisco, J., Breaux, C. A., & Sjoberg, M. D. (2012). Using intergroup contact theory to reduce stigma against transgender individuals: Impact of a transgender speaker panel presentation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology,42, 2583–2605. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.15591816.2012.00955.x

Wash, R., Rader, E., & Fennell, C. (2017). Can people self-report security accurately?: Agreement between self-report and behavioral measures. In Proceedings of the 2017 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 2228–2232). ACM.

Funding

This research was supported by a postgraduate studentship grant to Haffiezhah Azlan from MARA Education Sponsorship Division, Malay for Indigenous People’s Trust Council (MARA), MARA Head Office 21, Jalan Raja Laut 50609 Kuala Lumpur: 330408224812.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Haffiezhah A. Azlan, Paul G. Overton, Jane Simpson, and Philip A. Powell declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee (Department of Psychology Ethics Committee, University of Sheffield) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Human and animal rights and Informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Azlan, H.A., Overton, P.G., Simpson, J. et al. Disgust propensity has a causal link to the stigmatization of people with cancer. J Behav Med 43, 377–390 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-019-00130-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-019-00130-4