Abstract

Objective

This study was conducted to examine the factors associated with stigma in breast cancer women.

Methods

PubMed, Embase, the Cochrane Library, Web of Science, and two Chinese electronic databases were electronically searched to identify eligible studies that reported the correlates of stigma for patients with breast cancer from inception to July 2022. Two researchers independently performed literature screening, data extraction, and risk of bias assessment. R4.1.1 software was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Twenty articles including 4161 patients were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. Results showed that breast cancer stigma was positively correlated with working status, type of surgery, resignation coping, depression, ambivalence over emotional expression, and delayed help-seeking behavior and negatively correlated with age, education, income, quality of life, social support, confrontation coping, psychological adaptation, self-efficacy, and self-esteem. Descriptive analysis showed that breast cancer stigma was positively correlated with intrusive thoughts, body image, anxiety, and self-perceived burden but negatively correlated with a sense of coherence, personal acceptance of the disease, sleep quality, cancer screening attendance and doctor’s empathy.

Conclusion

Many demographic, disease-related, and psychosocial variables are related to breast cancer stigma. Our view can serve as a basis for health care professionals to develop health promotion and prevention strategies for patients with breast cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

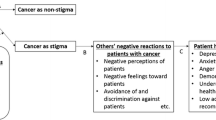

Breast cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors threatening women’s health worldwide. In the 2020 Global Cancer Report, breast cancer has replaced lung cancer as the number one cancer disease worldwide, with 2.26 million new cases [1]. A recent report from the American Cancer Society shows that the incidence of breast cancer in the USA continues to increase by 0.5% per year [2]. In addition, the incidence of breast cancer in China ranks first among cancers in females. The mortality rate of breast cancer is the sixth; about 210,000 new breast cancer cases are diagnosed per year, which is 1–2% more than that in developed countries; and breast cancer seriously affects the health and development of women [3]. The 5-year relative survival rate for patients with breast cancer is about 82% [4]. Although the prognosis has improved, the adverse effects (such as mastectomy, alopecia, and lymphedema) caused by surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy may severely disfigure patients and have a negative impact on the life of patients [5,6]. In addition, the psychological stress caused by adverse effects will cause patients to suffer from stigma because of changes in their body image and other people’s perception of their “abnormalities” and limit their social interaction [7].

Stigma, which originated from the Greek word “stizein,” refers to the fact that the patient is treated differently from ordinary people because of their disease and an individual’s internal shame experience due to discrimination and misunderstanding by others [8]. The prevalence of stigma in patients with cancer patients is between 5 and 90% [9,10,11,12]. About 76.7% of breast cancer survivors in China reported moderate levels of stigma [13]. Breasts are considered a sign of physical and sexual attraction and femininity. The psychological impact of a mastectomy on a woman can be substantial. They face pain and disfigurement due to missing or asymmetrical breasts [14]. Tripathi et al. reported higher stigma scores in patients undergoing mastectomy compared to those undergoing breast-conserving surgery [15]. Mastectomy can cause a loss of confidence and self-esteem, which can lead to a strong sense of stigma and even negatively impact on quality of life (QoL) of patients [16]. Chemotherapy can improve cancer patients’ survival, but its severe adverse reactions limit the dose and continuation of treatment. Chemotherapeutic alopecia (CIA) is a painful side effect of chemotherapy. CIA can cause physical and psychological pain to patients, which will have an impact on their daily lives [17]. Suwankhong et al. found that society despises women with breast cancer who suffer from nausea, vomiting, hair loss, fatigue, and other symptoms caused by chemotherapy [5].

Breast cancer stigma is thought to be a unique, disease-specific contributing factor to the high prevalence of depressed mood among patients with breast cancer [18]. TORRES et al. used a qualitative study to explore the status of stigma and recovery in 32 breast cancer patients. The results showed that most patients expressed concerns about the impact of body change, disability on their life with their partner, and fear of isolation [19]. In addition, previous research has found that more stigma is associated with worse QoL for breast cancer survivors [20,21].

Many literatures have explored the factors correlated to the stigma of patients with breast cancer, but the results are inconsistent among studies. In a cross-sectional study, marital status was a factor related to breast cancer stigma [22]. However, Fujisawa found that marital status has no remarkable correlation with stigma in patients with breast cancer and that age, income, and QoL are related to stigma in patients with breast cancer [9]. Hence, this study aims to explore the stigma-related factors in patients with breast cancer through a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies reporting the correlates associated with breast cancer stigma. The protocols in this study was registered with PROSPERO on August 5, 2022, number CRD42022348798. The ethical approval was not necessary and was waived.

Search strategy

PubMed, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Embase, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, and Wan Fang Database were searched from inception to July 2022 to collect studies on the correlate of stigma in breast cancer patients. The search terms were: "breast neoplasms OR breast cancer OR breast tumor OR breast tumors OR breast carcinoma OR breast carcinomas," "social stigma OR stigma OR shame OR blame OR guilty," and "correlate OR factors OR predictor OR relationship OR association OR determinant." In addition, references in this review and previous relevant systematic reviews were checked to determine additional studies. Details of the searching strategies are presented in Table 1.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria of the study followed the participants–interventions– control–outcome literature search format. The inclusion criteria for the meta-analysis were as follows: ① population: patients (age ≥ 18 years) with breast cancer; ② intervention/exposure: patients with breast cancer who reported stigma; ③ comparison: patients with breast cancer who did not report stigma; ④ outcomes: correlates associated with stigma in patients with breast cancer (e.g., demographic variables). Studies were excluded if they did not have breast cancer and stigma as the primary research question or outcome.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two researchers independently reviewed all eligible literature. According to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the titles were preliminary screened, followed by abstract screening, to exclude the literature that did not meet the inclusion criteria. The two investigators had a concentrated discussion after the initial screening. If the two sides could not reach an agreement, a third investigator was consulted to determine whether the literature would be included. The data extracted included the first author, publication time, country, sample size, study design, stigma assessment tool, and correlates.

Two investigators independently assessed the risk of bias of the included studies using the cross-sectional Study Quality Assessment Scale recommended by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) [23]. The AHRQ scale consists of 11 items, and each item is evaluated by “yes,” “no,” or “unclear.” The scoring method is 1 point for “yes,” and 0 points for “no” or “unclear.” The total score of each item is in the range of 0–11 points. The scores of 0–3, 4–7, and 8–11 indicate low quality, medium quality, and high quality, respectively. Finally, medium- and high-quality literatures were included.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

A meta-analysis was conducted using Review Manager 5.3 and Stata 16.0 software, with P < 0.05 as statistically significant. Pearson correlation coefficients (r) were used as effect sizes. Spearman’s correlation coefficient (rs), odds ratio (OR), or standardized regression coefficient (β) were converted to r according to the following formula when used instead of r [24,25,26].

I2 test was used to assess the heterogeneity among the included studies [11]. I2 > 50% and P < 0.05 indicate heterogeneity among the studies, and a random effect model was used. Otherwise, a fixed effect model was used. Sensitivity analysis was used to eliminate individual studies individually to evaluate the stability of the meta-analysis results, and subgroup analysis was conducted to explore the possible sources of heterogeneity. Egger’s test was used to assess publication bias. Trim-and-fill analysis was performed to assess the effect of publication bias.

Results

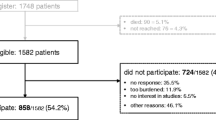

Study selection

A total of 1582 articles were obtained after the initial search, and 1251 articles remained after eliminating duplicates. Sixty records remained after title and abstract screening. In the full-text screening, 18 documents were excluded because they did not report correlates with stigma, 8 studies were excluded because necessary data were unavailable, and 6 articles were excluded because of low quality. Moreover, three documents were excluded because they were reviews, two studies were excluded because of the unavailability of their full texts, and three articles were excluded because they included other cancer types. Finally, 20 eligible articles were included in the meta-analysis. Figure 1 shows the flow diagram of the study selection.

Study characteristics

All the included studies were published between 2017 and 2022 [13,15,20,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. A total of 4161 patients with breast cancer were included in the 20 studies, with 83–448 patients in each study. Among the included studies, 13 studies were from Asian countries [13,15,22,27,28,29,30,32,33,35,40,41,42], and 7 from European and American countries [20,31,34,36,37,38,39]. All studies were cross-sectional. In addition, income was the most frequently reported correlate. The quality assessment scores ranged from 6 to 9 points.

The measure of stigma included the Cancer Stigma Scale (CASS), the Self-Stigma Scale Short Form (SSS), the Stigma scale for Chronic Illness-8 (SSCI-8), the Social Impact Scale (SIS), the Link Stigma Scale (LSS), the Body Image after Breast Cancer Questionnaire (BIBCQ), and the 13-item Intersectional Discrimination Index–Major scale (InDI-M). CASS contains 5 items, divided into 6 dimensions: embarrassment, avoidance, severity cognition, policy, self-blame, and economic discrimination. SSS covers 9 entries; SSCI-8 included 8 items and two dimensions, internal stigma, and external stigma. The SIS comprises 24 items, with four dimensions: social exclusion, economic discrimination, internal shame, and social isolation. The BIBCQ contains 6 subscales; the LSS consists of three subscales: perceived devaluation-discrimination, stigma-coping orientation, and stigma-related feeling. The InDI-M is a 13-items scale asking about various major stigma experiences.

Table 2 shows the characteristic and cumulative scores of the quality assessment of the included literature for the meta-analysis. The contents of the literature quality assessment are shown in Table 3.

Synthesis of results

Eighteen variables, including demographic data (age, education, income, full-time employment, marital status), disease-related factors (postoperative time and type of surgery), and psychological factors (QoL, social support, confrontation coping, resignation coping, self-esteem, psychosocial adaptation, depression, self-efficacy, ambivalence over emotional expression, and delay in help-seeking behavior), were quantitatively analyzed. The results on the correlates of breast cancer stigma are described below.

Demographic variable

Age

Three articles reported the association between age and breast cancer stigma [22,40,42]. Higher cancer stigma scores were associated with being younger (z = − 0.08, 95%CI: − 0.14– − 0.01; Fig. 2).

Education

Four studies analyzed the association between education and breast cancer stigma [15,22,28,30]. There was no significant heterogeneity among the included studies (I2 = 61%, P = 0.05). Breast cancer stigma was negatively correlated with higher levels of education (z = − 0.15, 95%CI: − 0.22– − 0.08; Fig. 3). Sensitivity analysis showed no change in z value after each study was omitted (Fig. 4).

Income

Five studies reported the correlation between income and breast cancer stigma [22,28,30,39,40]. Four studies had a significant heterogeneity (I2 = 61%, P = 0.04). The combined results showed that higher breast cancer stigma scores were associated with lower income (z = − 0.19, 95%CI: − 0.29– − 0.09; Fig. 5). The sensitivity analysis showed no alteration in the z-value after omitting one study at a time (z = − 0.19, 95%CI: − 0.28– − 0.09). This finding indicates the good reliability of the results (Fig. 6).

Working status (full-employment)

The correlation between working status and breast cancer stigma was reported in two studies [28,30]. The results suggested that increased breast cancer stigma was correlated with full-employment (z = 0.14, 95%CI: 0.03–0.24; Fig. 7).

Marital status (married)

Two studies explored the association between marital status and breast cancer stigma [22,30]. The combined estimates were not significantly different in the included studies (z = − 0.25, 95%CI: − 0.55–0.10; Fig. 8).

Disease-related variables

Postoperative time

The outcome measures in two studies involved postoperative time [28,40]. The fixed-effect model showed no significant differences in the estimates of study effect sizes (z = 0.06, 95%CI: − 0.03–0.14; Fig. 9).

Type of surgery (mastectomy)

Two studies reported the association between the type of surgery and breast cancer stigma [15,40]. The results showed that higher scores of breast cancer stigma are correlated with mastectomy (z = 0.39, 95%CI: 0.31–0.47; Fig. 10).

Psychosocial variables

Quality of life

Five studies reported the relationship between QoL and breast cancer stigma [20,27,29,36,37]. After using the fixed effects model, the results show that increased cancer stigma was associated with a lower QoL (z = − 0.53, 95%CI: − 0.57– − 0.48; Fig. 11).

Social support

Three studies involving 628 patients with breast cancer reported the relationship between social support and stigma [13,22,27]. The random effects model showed that breast cancer stigma was negatively correlated with social support (z = − 0.26, 95%CI: − 0.38– − 0.14; Fig. 12). The results of sensitivity analysis indicated that the pooled z-value between social support and breast cancer stigma did not change after omission (z = − 0.26, 95%CI: − 0.38– − 0.14; Fig. 13).

Confrontation coping

Three studies reported the correlation between confrontation coping and breast cancer stigma [27,35,42]. Pooled results revealed that higher breast cancer stigma score was correlated with lower confrontation coping (z = − 0.49, 95%CI: − 0.54– − 0.43; Fig. 14).

Resignation coping

Three studies explored the correlation between resignation coping and breast cancer stigma [13,35,42]. The results of the meta-analysis revealed that breast cancer stigma was positively correlated with resignation coping (z = 0.52, 95%CI: 0.46–0.58; Fig. 15).

Psychosocial adaptation

Two studies reported the correlation between psychosocial adaptation and breast cancer stigma [33,35]. Pooled results obtained using a random effects model revealed that breast cancer stigma was negatively correlated with psychological adaptation (z = − 0.62, 95%CI: − 0.75– − 0.46; Fig. 16).

Self-esteem

Two studies analyzed the correlation between self-esteem and breast cancer stigma [22,42]. A great heterogeneity was found in the studies (I2 = 91%, P < 0.01). The random effects model revealed that breast cancer stigma was negatively correlated with self-esteem (z = − 0.46, 95%CI: − 0.67– − 0.18; Fig. 17).

Depression

Two studies with 246 participants reported the association between anxiety and breast cancer stigma [15,39]. Combined results using random effects models showed that increased breast cancer stigma scores were associated with increased depressive symptoms (z = 0.41, 95%CI: 0.20–0.59; Fig. 18).

Self-efficacy

Two studies reported the relationship between self-efficacy and breast cancer stigma [12,13]. The random effect model showed that the breast cancer stigma score was negatively correlated with self-efficacy (z = − 0.54, 95%CI: − 0.68– − 0.37; Fig. 19).

Ambivalence over emotional expression

Two studies with a total of 248 patients analyzed the relationship between ambivalence over emotional expression and breast cancer stigma [34,37]. The fixed effects model showed that patients with breast cancer with higher levels of ambivalence of emotional expression had higher levels of stigma (z = 0.41, 95%CI: 0.30–0.51; Fig. 20).

Delay in help-seeking behavior

Three studies identified the association between delay in help-seeking behavior and breast cancer stigma [31,32]. Pooled results obtained using a fixed effects model showed that higher breast cancer stigma was correlated with higher frequency of delay in help-seeking behavior (z = 0.39, 95%CI: 0.32–0.46; Fig. 21).

Descriptive analysis

Results were presented descriptively as the following correlates were mentioned in only one literature. Breast cancer stigma was positively correlated with intrusive thoughts (r = 0.63, P < 0.05) [37], body image (r = 0.088, P < 0.05) [13], and self-perceived burden (r = 0.41, P < 0.05) [36] and negatively correlated with sense of coherence (r = − 0.35, P < 0.05) [27], personal acceptance of the disease (r = − 0.061, P < 0.05) [13], sleep quality (r = − 0.52, P < 0.05) [34], doctor’s empathy (r = − 0.799, P < 0.05) [41], cancer screening attendance (r = − 0.127, P < 0.05) [38], and anxiety (r = 0.166, P < 0.05) [15].

Discussion

Data from the 20 studies showed that breast cancer stigma was positively correlated with full employment, type of surgery, depression, ambivalence over emotional expression, and delay in help-seeking behavior and negatively correlated with age, education, income, QoL, social support, confrontation coping, psychological adaption, self-efficacy, and self-esteem. Breast cancer stigma had no correlations with marital status and postoperative time.

Demographic variables

The meta-analysis results of demographic data reported in the literature showed that age was negatively correlated with breast cancer stigma, which was consistent with the results reported in a previous study [43]. It may be due to is that young women with breast cancer experience constant social evaluation of their body and related problems. While older women may have experienced physical and psychological changes, which may enable them to better deal with changes in appearance [44]. However, Li et al. [45] and Hu et al. [28] found that no remarkable association between age and breast cancer stigma, which may be related to the small sample size. However, our results are based on a sample of 810 patients.

A low education level was positively associated with an increased risk of breast cancer stigma in our study, which was consistent with previous findings [46,47]. It may be due to the fact that it is more difficult for patients with poor education to find practical help in various ways, such as exercise decompression, which can regulate their psychological well [48]. In addition, the heterogeneity of this factor is high, which may be related to inconsistencies in study area. The study of Tripathi et al. was carried out in India [15], and the other three studies were conducted in China [22,28,30].

We identified that income was negatively associated with breast cancer stigma, which was consistent with the findings of a previous study in Japan [43]. Lin et al. found that families with better incomes could provide patients with better medical rehabilitation treatment [49]. However, patients with low incomes were more worried about the pressure of the disease on their lives [46]. Notably, the interstudy heterogeneity was high for this factor. The sensitivity analysis showed that the study of Xiao et al. is the source of heterogeneity [30], which may be due to patients with stage I–II breast cancer were included, and it was inconsistent with patients in other studies [22,28,39,40].

We found that full-employment was an essential correlate in reporting breast cancer-related stigma. Patients with breast cancer who had stable employment were proven to be more likely to develop stigma than those who were not employed. This finding was consistent with a previous study [50], where breast cancer patients with full-employment were associated with a higher desire to return to society and greater sensitivity to external reactions [51].

In addition, our meta-analysis did not identify that marital status was remarkably correlated with breast cancer stigma. The conclusion of the included two studies was controversial, possibly due to population variations. For example, breast cancer patients aged 18–45 years were included in the study of Kong et al. [22], while Xiao et al. did not have inclusion criteria for the age of the patients[30].

Disease-related variables

Regarding the disease-related variables, our study revealed that postoperative time was not substantially correlated with breast cancer stigma. More literature may be needed to explore the association between postoperative time and the level of breast cancer stigma.

In terms of the association of the type of surgery with stigma among patients with breast cancer in our meta-analysis, we found that patients with mastectomy were likely to develop stigma, which was consistent with several published studies [15,45]. It may be due to the fact that mastectomy can cause a noticeable change in the body image of a woman with breast cancer and create a sense of loss of femininity, increasing the level of stigma[52]. Therefore, clinical staff should pay more attention to patients with breast cancer undergoing mastectomy and reduce their stigma level.

Psychosocial variables

The present meta-analysis has demonstrated that the levels of breast cancer stigma vary with the degree of QoL. In agreement with a previously published study [53], the meta-analysis revealed that higher levels of breast cancer stigma were correlated with lower QoL. Several factors may contribute to this result. It cannot be excluded that breast cancer survivors experience social isolation and impaired sexual relationships due to stigma [5], which has a negative impact on the QoL of patients. Also, breast cancer survivors with stigma conceal the diagnosis, avoid medical treatment, decrease treatment compliance and impair QoL [54].

The study also revealed a remarkably negative correlation between breast cancer stigma and social support. The result accords with the findings of Hamdi et al., indicating that support from spouses can encourage breast cancer survivors to accept their condition and be courageous in their fight against the disease [50]. Meanwhile, support from medical staff is a reliable source to provide professional support to patients [55]. Notably, the interstudy heterogeneity of this factor is high, which may be due to the inconsistency of study subjects. According to sensitivity analysis results, the literature of Kong et al. was the main source of heterogeneity [22]. The inclusion criteria of Kong et al. were young patients with breast cancer [22], while the other two studies did not have the inclusion criteria [13,27].

In addition, confrontation coping and resignation coping were negatively and positively correlated with breast cancer stigma, respectively. Confrontation coping is primarily aimed at solving problems, including putting a positive spin on the problem to seek social support, which is a proactive adaptation process. It is a positive coping mode, which is conducive to patients’ physical and psychological health [56], whereas resignation coping is a negative coping style that ignores and downplays the existence or severity of stressful events [56]. Hence, the coping styles of breast cancer survivors should be evaluated and more active coping strategies taught in daily care.

Lower psychosocial adaptation and self-esteem are associated with high level of breast cancer stigma, which is consistent with several published studies[57,58]. Mark et al. found that good psychosocial adaptation can improve the psychological state of patients and help patients better adapt to the disease [59]. A previous literature suggests that people with low self-esteem are often disagreeable, while people with high self-esteem often face challenges with a more positive attitude [60]. In addition, substantial heterogeneity was observed in the included studies, which may be due to inconsistencies in the population. For example, Kang et al. included breast cancer patients who had undergone surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy [33], while in the study of Yin et al., only patients who had received surgery were observed [35]. In addition, Kong et al. included breast cancer patients who had undergone mastectomy, breast reconstruction, and other surgery [22], while Shi et al. only included patients who had undergone mastectomy[42].

Depression is widely mentioned as psychological problem in patients with breast cancer, and their association with stigma has also been extensively supported [61]. Cancer patients who experienced social stigma were four times more likely to develop depression [62]. In our study, we also validated this relationship. A published study has shown that one symptom’s presence may increase the risk of another and vice versa [63]. Ma et al. suggested that the occurrence and development of stigma can be affected by the synergistic effect of negative psychological such as depression and demographic factors [64]. Therefore, we proposed that psychological factors interact with each other and affect daily life, so coping with the psychological burden of breast cancer is vital.

Furthermore, the results of our meta-analysis showed that higher levels of breast cancer stigma were correlated with poorer self-efficacy, higher ambivalence over emotional expression, and the more frequent delays in help-seeking behavior. According to Elumelu, self-efficacy is an important factor in evaluating self-confidence and it plays an important role in promoting the positive psychological response of individuals [65]. Emotional expression plays a vital role in the health of cancer patients [66]. Studies have found that ambivalence over emotional expression is associated with poorer mental health in high-risk populations c[67,68], and our results support these observations. Furthermore, Harris et al. also identified that stigma of cancer patients was positively correlated with their medical-seeking behavior, which is consistent with our results [69]. In addition, stigma has been proven to be a significant reason breast cancer patients are unwilling to expose their bodies [70].

Implications

The results of this meta-analysis can be used by clinical staff to design future interventions to reduce breast cancer stigma and promote patient health. First, medical staff should give more attention to the incidence of stigma in young and poor educated patients with breast cancer, because they have a higher level of stigma. Second, policymakers should improve health insurance to help low-income patients. In addition, interventions targeting psychosocial factors, including social support, depression, self-efficacy, self-esteem, and coping styles, may be useful in reducing breast cancer stigma, potentially reducing the psychological distress and improving the physical health of patients.

Strengths and limitations

First, this study is the first systematic review and meta-analysis of correlate with breast cancer stigma. Second, an extensive article search was conducted to comprehensively screen research papers and other relevant literature to minimize the possibility of missing any research. Third, most of the included studies are of high quality with reliable results.

However, our study has some limitations. First, some related factors have only been reported in a few studies, and we were unable to clarify the relationship between these factors and breast cancer stigma through meta-analysis. Second, we found that some of the correlates showed high heterogeneity, which may be related to the geographic area of the study, study populations. Third, only articles published in English and Chinese were included in this study, which may contribute to language bias.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this meta-analysis explored the correlates of stigma in patients with breast cancer. Working status, type of surgery, resignation coping, depression, ambivalence over emotional expression, and delayed help-seeking behavior are positively correlated with the stigma of breast cancer. Age, education, income, QoL, social support, confrontation coping, psychological adaptation, self-efficacy, and self-esteem are proven to be negatively associated with breast cancer stigma. The results may help in the timely identification of high-risk patients for timely intervention and treatment, to reduce the stigma level and improve the clinical outcomes of patients with breast cancer. However, more high-quality studies with large samples are needed for further validation.

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F, Global Cancer Statistics 2020 (2021) GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: Cancer J Clin 71(3):209–249

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE (2021) Cancer Statistics, 2021. CA: Cancer J Clin 71:33–37

Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, Jemal A, Yu XQ, He J (2016) Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA: Cancer J Clin 66(2):115–132

Zeng H, Chen W, Zheng R, Zhang S, Ji JS, Zou X, Xia C, Sun K, Yang Z, Li H et al (2018) Changing cancer survival in China during 2003–15: a pooled analysis of 17 population-based cancer registries. Lancet Glob Health 6(5):e555–e567

Suwankhong D, Liamputtong P (2016) Breast cancer treatment: experiences of changes and social stigma among Thai women in Southern Thailand. Cancer Nurs 39(3):213–220

Esser P, Mehnert A, Johansen C, Hornemann B, Dietz A, Ernst J (2018) Body image mediates the effect of cancer-related stigmatization on depression: a new target for intervention. Psychooncology 27(1):193–198

Rajasooriyar CI, Kumar R, Sriskandarajah MH, Gnanathayalan SW, Kelly J, Sabesan S (2021) Exploring the psychosocial morbidity of women undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer in a post-war setting: experiences of Northern Sri Lankan women. Support Care Cancer : Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer 29(12):7403–7409

Goffman E (1963) Stigma; notes on the management of spoiled identity. In: 1963.

Fujisawa D, Umezawa S, Fujimori M, Miyashita M (2020) Prevalence and associated factors of perceived cancer-related stigma in Japanese cancer survivors. Jpn J Clin Oncol 50(11):1325–1329

Phelan SM, Griffin JM, Jackson GL, Zafar SY, Hellerstedt W, Stahre M, Nelson D, Zullig LL, Burgess DJ, van Ryn M (2013) Stigma, perceived blame, self-blame, and depressive symptoms in men with colorectal cancer. Psychooncology 22(1):65–73

Ohaeri JU, Campbell OB, Ilesanmil AO, Ohaeri BM (1998) Psychosocial concerns of Nigerian women with breast and cervical cancer. Psychooncology 7(6):494–501

Yang N, Xiao H, Wang W, Li S, Yan H, Wang Y (2018) Effects of doctors’ empathy abilities on the cellular immunity of patients with advanced prostate cancer treated by orchiectomy: the mediating role of patients’ stigma, self-efficacy, and anxiety. Patient Prefer Adherence 12:1305–1314

Ruiqi J, Tingting X, Lijuan Z, Ni G, June Z (2021) Stigma and its influencing factors among breast cancer survivors in China: A cross-sectional study. Eur J Oncol Nurs 52(prepublish).

Liang D, Jia R, Yu J, Wu Z, Chen C, Lu G (2021) The effect of remote peer support on stigma in patients after breast cancer surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic: a protocol for systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 100(24):e26332

Lopamudra T, Shankar DS, Kumar AS, Sanjoy C, Rosina A (2017) Stigma perceived by women following surgery for breast cancer. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol: Off J Indian Soc Med Paediatr Oncol 38(2).

Fang SY, Shu BC, Chang YJ (2013) The effect of breast reconstruction surgery on body image among women after mastectomy: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat 137(1):13–21

Trusson D, Pilnick A (2017) The role of hair loss in cancer identity: perceptions of chemotherapy-induced alopecia among women treated for early-stage breast cancer or ductal carcinoma in situ. Cancer Nurs 40(2):E9-e16

Amini-Tehrani M, Zamanian H, Daryaafzoon M, Andikolaei S, Mohebbi M, Imani A, Tahmasbi B, Foroozanfar S, Jalali Z (2021) Body image, internalized stigma and enacted stigma predict psychological distress in women with breast cancer: A serial mediation model. J Adv Nurs 77(8):3412–3423

Torres E, Dixon C, Richman AR (2016) Understanding the breast cancer experience of survivors: a qualitative study of African American women in rural Eastern North Carolina. J Cancer Educ : Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ 31(1):198–206

Wong CCY, Pan-Weisz BM, Pan-Weisz TM, Yeung NCY, Mak WWS, Lu Q (2019) Self-stigma predicts lower quality of life in Chinese American breast cancer survivors: exploring the mediating role of intrusive thoughts and posttraumatic growth. Qual Life Res: Int J Qual Life Asp Treat, Care Rehabil 28(10):2753–2760

Sun T, Zhang SE, Yan MY, Lian TH, Yu YQ, Yin HY, Zhao CX, Wang YP, Chang X, Ji KY et al (2022) Association between self-perceived stigma and quality of life among urban chinese older adults: the moderating role of attitude toward own aging and traditionality. Front Public Health 10:767255

Kong R, Wang Y, Ge S (2017) Stigma and influencing factors among young breast cancer patients after surgery. J Nurs Sci 32(8):84–86

Rostom A, Dubé C, Cranney A, Saloojee N, Sy R, Garritty C, Sampson M, Zhang L, Yazdi F, Mamaladze V et al (2004) Celiac disease. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 104:1–6

Peterson RA, Brown SP (2005) On the use of beta coefficients in meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol 90(1):175–181

Cohen J (1988) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences., vol. 2nd. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Li Y, Wang F, Liu J, Wen F, Yan C, Zhang J, Lu X, Cui Y (2019) The Correlation between the severity of premonitory urges and tic symptoms: a meta-analysis. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 29(9):652–658

Zamanian H, Amini-Tehrani M, Jalali Z, Daryaafzoon M, Ramezani F, Malek N, Adabimohazab M, Hozouri R, Taghanaky FR (2022) Stigma and quality of life in women with breast cancer: mediation and moderation model of social support, sense of coherence, and coping strategies. Front Psychol 13.

Hu LL, Zhou X, Wang Y, Yuan Z, Huihui R, Feng Y (2022) Influencing factors of stigma after modified radical mastectomy in patients with breast cancer. China Med Herald 19(2):100–103

Zhuang HZ, Wang L, Yu XF, Chan SWC, Gao YX, Li XQ, Gao S, Zhu JM (2022) Effects of decisional conflict, decision regret and self-stigma on quality of life for breast cancer survivors: a cross-sectional, multisite study in China. J Adv Nurs

Xiao HM, Zhou XY, Zhang XJ, Li N, L XZ (2021) Influencing factors of stigma in breast cancer patients after operation and its relationship with self-esteem, quality of life and psychosocial adaptability. Progress in Modern Biomedicine 21(23):4522–4526,4568.

Poteat TC, Adams MA, Malone J, Geffen S, Greene N, Nodzenski M, Lockhart AG, Su IH, Dean LT (2021) Delays in breast cancer care by race and sexual orientation: Results from a national survey with diverse women in the United States. Cancer 127(19):3514–3522

Pakseresht S, Tavakolinia S, Leili EK (2021) Determination of the association between perceived stigma and delay in help-seeking behavior of women with breast cancer. Maedica 16(3):458–462

Kang NE, Kim HY, Kim JY, Kim SR (2020) Relationship between cancer stigma, social support, coping strategies and psychosocial adjustment among breast cancer survivors. J Clin Nurs 29(21–22):4368–4378

C WIH, William T, H ML, Qian L (2020) The associations of self-stigma, social constraints, and sleep among Chinese American breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer : Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer 28(8).

Yin CL, Qu HL, Xia TT, Ma H, Yang FG Correlation research between stigma, coping style and psychosocial adjustment in young patients with breast cancer. Chin J Prac Nurs 2019(15):1126-1131.

Yeung NCY, Lu Q, Mak WWS (2019) Self-perceived burden mediates the relationship between self-stigma and quality of life among Chinese American breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer :Off J Multinatl Assoc Support Care Cancer 27(9):3337–3345

William T, C WIH, Qian L (2019) Acculturation and quality of life among Chinese American breast cancer survivors: the mediating role of self-stigma, ambivalence over emotion expression, and intrusive thoughts. . Psycho-oncol 28(5).

Vrinten C, Gallagher A, Waller J, Marlow LAV (2019) Cancer stigma and cancer screening attendance: a population based survey in England. Bmc Cancer 19.

Tsai W, Lu Q (2019) Ambivalence over emotional expression and intrusive thoughts as moderators of the link between self-stigma and depressive symptoms among Chinese American breast cancer survivors. J Behav Med 42(3):452–460

Zheng CR, Wang HZ (2018) Current status and influencing factors of stigma in breast cancer patients after surgery. J Nurs Res 25(2):7–9

Yang N, Cao Y, Li X, Li S, Yan H, Geng Q (2018) Mediating effects of patients’ stigma and self-efficacy on relationships between doctors’ empathy abilities and patients’ cellular immunity in male breast cancer patients. Med Sci Monit:Int Med J Exp Clin Res 24:3978–3986

Shi JQ, Ma JL, Hu FH, Ye HZ (2018) Correlation of stigma, coping style and self-esteem among patients after breast modified radical mastectomy. Chin J Mod Nurs 24(3):332–335

Fujisawa D, Umezawa S, Fujimori M, Miyashita M (2021) Prevalence and associated factors of perceived cancer-related stigma in Japanese cancer survivors. Jpn J Clin Oncol 50(11):1325–1329

Liu XH, Zhong JD, Zhang JE, Cheng Y, Bu XQ (2020) Stigma and its correlates in people living with lung cancer: A cross-sectional study from China. Psychooncology 29(2):287–293

Li Y, Li Y, Zhang J, Jiang J, Liu L (2017) A study on the status and influencing factors of stigma for breast cancer patients after operation. Anti-Tumor Pharmacy 7(5):636–640

Yılmaz M, Dissiz G, Usluoğlu AK, Iriz S, Demir F, Alacacioglu A (2020) Cancer-related stigma and depression in cancer patients in a middle-income country. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs 7(1):95–102

Else-Quest NM, LoConte NK, Schiller JH, Hyde JS (2009) Perceived stigma, self-blame, and adjustment among lung, breast and prostate cancer patients. Psychol Health 24(8):949–964

Zha M, Li J, Liu Y, Liu Y, Li A, Jie C (2020) Correlation between stigma and disability acceptance in patients with hemiplegia due to cerebral hemorrhage. Chin Nurs Manag 20(3):459–463

Xie FY, Xie FL, Yu J Quality of life and its influencing factors in patients with breast cancer. J Nurs Res 2015(17):38–42.

Hamid W, Jahangir MS, Khan TA (2021) Lived experiences of women suffering from breast cancer in Kashmir: a phenomenological study. Health Promot Int 36(3):680–692

Zhang YD, Liu RH, Han F (2020) The impact of stigma on job behavior among breast cancer survivors after return to work: a cross-sectional study. J Nurs Sci 35(3):67–70

Collins JP (2016) Mastectomy with tears: breast cancer surgery in the early nineteenth century. ANZ J Surg 86(9):720–724

Ernst J, Mehnert A, Dietz A, Hornemann B, Esser P (2017) Perceived stigmatization and its impact on quality of life - results from a large register-based study including breast, colon, prostate and lung cancer patients. BMC Cancer 17(1):741

Mak WW, Cheung RY (2010) Self-stigma among concealable minorities in Hong Kong: conceptualization and unified measurement. Am J Orthopsychiatry 80(2):267–281

Chao YH, Wang SY, Sheu SJ (2020) Integrative review of breast cancer survivors’ transition experience and transitional care: dialog with transition theory perspectives. Breast Cancer 27(5):810–818

Sun MY, Chen J (2017) Research on the coping style of infertile patients. Chin J Mod Nurs 23(1):137-139,140

Liu H, Yang Q, Narsavage GL, Yang C, Chen Y, Xu G, Wu X (2016) Coping with stigma: the experiences of Chinese patients living with lung cancer. Springerplus 5(1):1790

den Heijer M, Seynaeve C, Vanheusden K, Duivenvoorden HJ, Vos J, Bartels CC, Menke-Pluymers MB, Tibben A (2011) The contribution of self-esteem and self-concept in psychological distress in women at risk of hereditary breast cancer. Psychooncology 20(11):1170–1175

Katz MR, Irish JC, Devins GM, Rodin GM, Gullane PJ (2003) Psychosocial adjustment in head and neck cancer: the impact of disfigurement, gender and social support. Head Neck 25(2):103–112

Li J (2011) A Study of Stigma of People with Schizophrenia and Relationships with Self-Esteem and Social Support. Master. Taishan Med Coll, China

Warmoth K, Wong CCY, Chen L, Ivy S, Lu Q (2020) The role of acculturation in the relationship between self-stigma and psychological distress among Chinese American breast cancer survivors. Psychol Health Med 25(10):1278–1292

Cho J, Smith K, Choi EK, Kim IR, Chang YJ, Park HY, Guallar E, Shim YM (2013) Public attitudes toward cancer and cancer patients: a national survey in Korea. Psychooncology 22(3):605–613

Lee SA, Jeon JY, No SK, Park H, Kim OJ, Kwon JH, Jo KD (2018) Factors contributing to anxiety and depressive symptoms in adults with new-onset epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav: E&B 88:325–331

Ma JL, Huang WW, Li XQ, Wang HP (2019) Relevance of intimate relationship with perceived stress among young and middle aged patient with gynecologic malignancies. Chin J Woman Child Health Res 30(8):1032–1036

Elumelu TN, Asuzu CC, Akin-Odanye EO (2015) Impact of active coping, religion and acceptance on quality of life of patients with breast cancer in the department of radiotherapy, UCH, Ibadan. BMJ Support Palliat Care 5(2):175–180

Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S, Cameron CL, Bishop M, Collins CA, Kirk SB, Sworowski LA, Twillman R (2000) Emotionally expressive coping predicts psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer. J Consult Clin Psychol 68(5):875–882

Krause ED, Mendelson T, Lynch TR (2003) Childhood emotional invalidation and adult psychological distress: the mediating role of emotional inhibition. Child Abuse Negl 27(2):199–213

Tucker JS, Winkelman DK, Katz JN (1999) Bermas BLJJoASP: Ambivalence over emotional expression and psychological well-being among rheumatoid arthritis patients and their spouses. Soc Psychol 29:271–290

Carter-Harris L (2015) Lung cancer stigma as a barrier to medical help-seeking behavior: Practice implications. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract 27(5):240–245

Jones CE, Maben J, Jack RH, Davies EA, Forbes LJ, Lucas G, Ream E (2014) A systematic review of barriers to early presentation and diagnosis with breast cancer among black women. BMJ Open 4(2):e004076

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZT drafted the manuscript, contributed to the study analysis and data interpretation. The second to fourth authors gave comments on the articles. XM contributed to the study design and the revision of the manuscript. TW and SC participated in the literature search.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

N/A.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, Wz., Yusuf, A., Jia, K. et al. Correlates of stigma for patients with breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer 31, 55 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07506-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-022-07506-4