Abstract

Using a between-subject 3 × 3 design of an experimentally manipulated realistic case vignette of Black, White, and Hispanic youth in a survey mailed to 1540 experienced psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers, the authors examined if clinicians alter their judgments about treatment for antisocially behaving youth based on the symptom’s social context (e.g., life circumstances) and the youth’s race or ethnicity, even among youth who are otherwise identical in terms of behavioral symptoms. Vignettes describe behaviors meeting DSM-IV criteria for conduct disorder, but contain contextual information suggesting either internal dysfunction (ID) or a normal response to a difficult environment [i.e., environmental-reaction (ER)]. Comparison was symptom-only (SO). Judgments of effectiveness of 14 treatments for youth exhibiting antisocial behavior were examined. Frequencies and median scores of perceived effectiveness level (1–9, Likert) were compared in bivariate analyses, stratifying context and youth’s race or ethnicity. The context of the behavior was associated significantly with differences in effectiveness judgments in 13 of 14 treatments. Within ID and ER contexts, clinicians judged three different treatments as effective (median ≥ 7 of 9). In the SO condition, clinicians were less selective, judging six as effective. In the ID context, psychiatric medications, systems oriented family therapy, and residential care were judged more effective for White than for Black or Hispanic youth. Evidence-based practice research may be hampered by inattention to the social context of behavioral symptoms. Context may activate implicit racial assumptions about treatment effectiveness. Implications are for clinical training to improve service delivery, and future clinical research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Selecting an appropriate treatment strategy for clients with mental health problems is central to clinical practice. The treatment decision-making process generally involves judgments about the nature of an individual’s problems, and a judgment about what treatment may be most effective. The treatment literature generally describes best practices based on diagnostic syndromes defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; DSM-5) (American Psychiatric Association 1994, 2013). However, clinicians often engage clients with complex life circumstances, in addition to diagnostic profiles. Clinical commonsense suggests that clients’ unique life circumstances would influence clinicians’ decisions about the type of treatment that would be most useful. But the evidence base for treatment guidelines mainly is generated from specific diagnostic and symptom profiles, not the context in which individuals live. There is widespread acceptance of the importance of knowing about, and adopting, evidence-based practices, yet in day-to-day practice, under pressure from insurance companies and mental health organizations, clinicians must make rapid decisions about what treatment is likely to be most effective for a given client (Jensen-Doss et al. 2009; Raghavan et al. 2008); limited treatment research has been conducted in everyday practice settings to provide needed guidance for practitioners in the field (Weisz et al. 2013). To date, there is little understanding of how clinicians make judgments about treatment effectiveness, and whether they use information beyond diagnostic symptoms to decide on the best treatment strategies.

A growing body of literature is emerging that suggests that behavioral context influences diagnostic decision-making and other clinical judgments, especially for youth with symptoms of conduct disorder. Existing research offers evidence that experienced clinicians are sensitive to the social context surrounding adolescent antisocial behavior, and that they judge youth as less likely to have a mental disorder when context suggests the behavior might be a normal reaction to a harsh environment, rather than irrational responses resulting from internal dysfunction (Hsieh 2001; Hsieh and Kirk 2003, 2005; Pottick et al. 2003, 2007; Wakefield et al. 2002, 2006). Other research studies have found that clinicians differentially use contextual information to weigh the importance of symptoms in judging whether a youth should be considered as having a diagnosis of conduct disorder (De Los Reyes and Marsh 2011; Marsh et al. 2016), and have demonstrated that contextual information not only influences how clinicians arrive at diagnoses, but can also influence their judgments about other aspects of the clinical encounter, such as prognosis, need for professional help, and appropriateness of medication (Wakefield et al. 1999).

Bias or inconsistency in assessment or treatment effectiveness poses a substantial threat to effective clinical practice. Recent research has demonstrated the troubling possibility that clinicians may be biased in their clinical judgments about mental disorder and service need, based on the race and ethnicity of youth. In one vignette study, Pottick et al. (2007) found that experienced psychologists, psychiatrists and social workers judged White youths to have a disorder more frequently than Black or Hispanic youths. In another vignette study, mental health professionals judged youth with Latino names as more impaired than youth with Anglo names; youth with Anglo names were judged to need more services than Latino-named youth, especially when they were judged to have higher levels of severity (Chavez et al. 2010). However, both of these studies leave unanswered the question addressed in this study: namely, whether clinicians’ judgments of treatment effectiveness vary by the behavior context and youth’s race or ethnicity. A better understanding of the interplay between the contextual conditions of clients and their race and ethnicity could provide new insights into treatment decision-making that could improve service delivery processes.

Here we use a national sample survey of experienced clinicians from the fields of psychology, psychiatry, and social work who were asked to make judgments on clinically realistic case vignettes of Black, Hispanic, and White youths with DSM-IV symptoms of conduct disorder (American Psychiatric Association 1994) to examine if clinicians alter their judgments about treatment effectiveness for antisocially behaving youth based on contextual information (e.g., life circumstances) and their race or ethnicity, even among youth who are otherwise identical in terms of their DSM-IV diagnostic symptoms. The study methodology relies on vignettes of youths in community settings, where initial diagnostic and treatment decisions are usually made, and focuses on conduct disorder because it is one of the most common childhood psychiatric diagnoses in both clinic and hospital settings, and the most common reason for referral of adolescents to treatment, accounting for 33% to 50% of cases referred for outpatient treatment (Kazdin 2003).

Decades of research substantiate that children from racial and ethnic minority backgrounds are less likely to use mental health services than White children (Kataoka et al. 2002; Popescu et al. 2015; Zimmerman 2005), and that these differences cannot be explained by a lack of need (Merikangas et al. 2010a, b). The lifetime prevalence rate for behavior disorders that include ADD (attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder), ODD (oppositional defiant disorder), and CD (conduct disorder) based on DSM-IV criteria is 19.1%, according to community data from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication—Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) (Merikangas et al. 2010b). Community-based epidemiological research from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (Merikangas et al. 2010a) reveals that the prevalence rate for conduct disorder over a 12-month period based on DSM-IV criteria is 2.1%. There are no gender differences in rates of conduct disorder, but conduct disorder is more prevalent among youth 12–15 years old compared to 8–11 year-olds. Compared to youths with other mental health disorders, youths with conduct disorder have some of the highest rates of use of mental health services over a 12-month period; estimates range from 46.4% (Merikangas et al. 2010a) to 73.4% (Costello et al. 2014), with the vast majority receiving services in the specialty mental health sector (45.9%) or in school settings (44.0%) (Costello et al. 2014). Overall, Black and Hispanic youth with any psychiatric disorder are less likely than White youth to receive mental health services, and this is especially pronounced in specialty mental health settings and within pediatric services (Costello et al. 2014).

Our study experimentally manipulated the context of problem behaviors using the inclusion and exclusion criteria for mental disorder in the DSM-IV text (American Psychiatric Association 1994) to distinguish between behavior that may be merely a normal reaction to a harsh environmental context and that which may be a manifestation of some internal dysfunction (i.e., mental disorder). It also experimentally manipulated the vignette youth’s race or ethnicity.

Our aim was to answer three questions: How do clinicians judge the effectiveness of practices commonly used in the treatment for antisocially behaving youth? Do clinicians alter their judgments about treatment effectiveness based on contextual information? Given the presence of identical DSM symptom criteria, do clinicians reach the same judgments regardless of the race or ethnicity of their clients? In this article we examine the contextual characteristics associated with judgments of the effectiveness of fourteen practices for treating antisocially behaving youth, and then examine whether the race or ethnicity of the youth influences their judgments. Derived from systematic examination of the factors of context and youth race or ethnicity, the results of this study have policy, programmatic, and training implications for those concerned about the best ways to ensure consistent quality of care.

Making Clinical Treatment Judgments

The development of the knowledge base for treatment of youth with symptoms of conduct disorder is continually evolving. Clinicians use several sources of information to make decisions about appropriate treatment strategies. One source of information is the extant literature on evidence-based practice, which is distinguished by its emphasis on the process of identifying and evaluating empirical evidence regarding the effectiveness of interventions, and using other sources of information, such as clinical expertise and client values, experiences, and preferences (Sackett et al. 2000). Another source of information is gained from personal interviews with the youth, parent and others involved in the identification of the behavioral problem complex. In general, clinicians must make assessments about the possible etiology of the youth’s problem. In other words, clinicians develop a “case theory” (Bisman 2014) that assesses the risk factors implicated in the behavior. As McCart and Sheidow (2016) state:

“It makes sense for our disruptive behavior treatments, whenever possible, to focus on all known risk factors for that presenting problem. For example, if a disruptive behavior treatment simply targeted youths’ cognitive impairments while ignoring other well-established risk factors that are present (e.g., maladaptive parenting and poor family relations, deviant peer influence, and low school involvement), that treatment would not be expected to yield substantial or durable effects” (p. 557).

Practically, to decide on the best possible treatment solutions, clinicians make causal inferences about the sources of the problem. In a vignette study of the effect of social context of symptoms on experienced clinicians’ judgments of the presence of a mental disorder in youth, Hsieh (2001) found that the context effects on disorder judgments were partially mediated by causal explanations: namely, behavioral symptoms presented in different social contexts lead clinicians to perceive different causes of the symptoms, which in turn lead to different disorder judgments. Causes associated with some biological, cognitive or behavioral mechanisms within the youth (e.g. brain dysfunction, poor impulse control, tendency to perceive hostile intent in others) correlated with mental disorder judgments; causes associated with problems in living in a difficult environment (e.g., harsh or inconsistent discipline, family discord, sociocultural influence) correlated with no mental disorder judgments. In a study of experienced psychiatrists, Hsieh and Kirk (2003) found that experienced psychiatrists reached different judgments about the effectiveness of various treatment interventions when the same behavior occurred in different social contexts. It appears that clinicians may make judgments about the effectiveness of treatments based on a theory of change that links the potential targets of intervention with treatment mechanisms that can potentially change them. It is important to ascertain whether and how clinicians may be using contextual information to make treatment decisions because that knowledge can potentially inform innovations in research investigation, and provide new information for clinicians to work effectively.

A solid and robust EBP literature exists showing that several treatments are promising, but the mechanisms of their effectiveness remain uncertain, leading to practical difficulties in deciding clinically who will best gain from any particular treatment (Kazdin and De Los Reyes 2008). In addition, complex problems in replicating treatments across sites and populations interfere with the generalizability and transportability of the treatments (Eyberg et al. 2008). Clinical scholars agree that many treatments commonly used in agency-based practice may or may not be effective; there is not sufficient testing to judge (Fonagy et al. 2015; Kazdin and De Los Reyes 2008; Ollendick and Shirk 2011). Additionally, there are concerns that explicit training in treatments with promising effectiveness for youth may be unavailable in many professional educational programs (Sburlati et al. 2011).

Despite limitations, there is some consensus on the state of the evidence-base for youths with conduct disorder, for reviews, see (Brestan and Eyberg 1998; Eyberg et al. 2008; Fonagy et al. 2015; Kazdin and De Los Reyes 2008). Recently, a comprehensive review by McCart and Sheidow (2016) has updated findings from previous studies. Multicomponent treatments (e.g., Multisystemic Treatment and Treatment Foster Care Oregon) that target multiple changes in the client’s various living environments, such as home, school, and juvenile correctional facilities, are now considered the most efficacious treatments for antisocially behaving youth, especially those involved in the juvenile justice system (McCart and Sheidow 2016). The evidence is promising for interventions based on cognitive-behavioral theory and skills, including parent management training, child social skills training, and cognitive problem-solving skills or problem-solving skills training (Kazdin and De Los Reyes 2008; McCart and Sheidow 2016). Based on the research evidence, functional family therapy has also garnered significant research support (Boxer and Frick 2008; McCart and Sheidow 2016).

The evidence is relatively weak or absent for other treatments. Support for the use of psychotropic medications for youth with conduct disorder is weak, although there is emerging agreement that medications can be helpful to treat co-morbid medical conditions such as ADHD, depression, bipolar disorder and anxiety (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2016), and that medication should not be used alone, but in conjunction with psychosocial treatments (American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2015). The evidence is weak for group therapy, often used in residential care and correctional settings, and in hospitals and schools. In controlled studies, Dishion et al. (1999) demonstrated that youth outcomes often worsen when youth are placed together with peers with serious behavioral problems, as it is likely that they negatively influence one another through a process of “deviancy training” as they bond with one another. In that same study, youth outcomes were better when youths participated in more heterogeneous groups with peers with less significant behavioral and delinquent problems (Dishion et al. 1999). These mixed results in the extant research literature suggest that other treatment choices would be more assuredly effective than group therapy. Evidence for other commonly used treatments for youth is extremely limited; family systems therapy, play therapy, and psychodynamic-oriented therapy have not been tested adequately to recommend these treatments over other tested ones (Kazdin and De Los Reyes 2008; Ollendick and Shirk 2011).

Most scholars concur that the evidence base for minority youth is in development, as cultural modifications in established evidence-based practices continue to be tested. But, in the main, research on evidence-based practices, especially those using cognitive behavioral techniques, such as parent management training, parent social skills training, group assertiveness training, or MST, which have been tested to include minority youth, are probably efficacious and are recommended for use with minority youth (Ho et al. 2011; Huey and Polo 2008; Miranda et al. 2005). While new research may find that some treatments are more effective when they are culturally adapted, there is no evidence to date that current tested treatments should not be viewed as the best practices to adopt for minority youth (For a review, see Ho et al. 2011).

Despite advances in research on treating youths with conduct disorder, uncertainty in their practical application remains. As Kazdin and De Los Reyes (2008) put it: “The extent to which the identification of EBTs has altered what is delivered to the public or the outcome of patients seen in treatment has yet to be demonstrated” (p. 231). There is a dearth of research literature on the evidence-base tested among antisocially behaving youth in community and home settings—that is, youth not involved with the juvenile justice or child welfare systems (McCart and Sheidow 2016). In addition, social agencies, many of which are resource-stressed, are not likely to be able to afford training in specialized programs to assure adherence and fidelity to EBP (McCart and Sheidow 2016), and often a select number of staff within an agency are trained in certain modalities with varying degrees of adherence to the EBP in practice. This leaves a large gap in information for clinicians in agency-based practice. Clinicians must rely on their best clinical judgments to make treatment decisions based on their experience, training, any EBP adopted by the organization, as well as clinicians’ perception of the sources of the problem and potential points of intervention.

Hypotheses

There is little empirical literature to guide expectations about how clinicians’ judge the effectiveness of commonly used treatments for youth with conduct disorder, so our hypotheses are driven by professional values and clinical experience.

-

(1)

We expect that clinicians will appropriately distinguish between treatments with demonstrated effectiveness and those shown in the literature to be less effective;

-

(2)

We expect that clinicians will alter their judgments about treatment effectiveness based on a youth’s behavioral context, by making distinctions that are sensitive to likely targets of intervention (i.e., person or environment).

-

(3)

We expect that the same treatments will be judged as equally effective for Black, White and Hispanic youth exhibiting the same behavior under the same social context.

Method

Design and Sampling Frame

We used a between-subjects design with experimentally manipulated case vignettes. A national sampling frame consisted of nonstudent psychologists, psychiatrists and social workers who were most likely to have clinical experience with youth and children. From membership lists of the American Psychiatric Association, American Psychological Association, and National Association of Social Workers, we selected only psychiatrists who indicated an interest in child or adolescent psychiatry, only psychologists who were “active practitioners” (clinicians) and whose specialty or areas of interest related to children and adolescents, and only social workers who were in clinical mental health or school social work. As differential response rates by occupational group were anticipated, psychologists and psychiatrists were oversampled relative to social workers. We randomly selected 1105 psychologists, 1101 psychiatrists, and 797 social workers, resulting in a study sampling frame of 3003 clinicians.

Procedure

Each clinician in the sample received a letter requesting participation with the questionnaire and self-addressed reply envelope. Non-respondents received up to three follow-up mailings. Institutional review boards at the researchers’ universities granted the study exemption status on the grounds that specific individuals were not identifiable in the data set. Data were collected from January to April 2000.

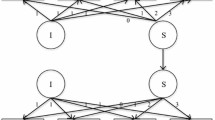

Vignette Construction

The primary independent variable in the study is the social context surrounding antisocial behaviors. To test whether a youth’s race or ethnicity affects judgments of treatment effectiveness, vignettes varied in describing either a White, Black or Hispanic youth. The White and Black youths were named “Carl” and were described as having moved to Los Angeles from Oklahoma. The Hispanic youth was named “Carlos” and was described as having moved to Los Angeles from Mexico. All other information in the vignettes was identical.

The vignettes were constructed around a core set of antisocial behaviors, which were presented with three different kinds of contexts. As a guide for developing a vignette that satisfied DSM-IV requirements for a mental disorder, we used the DSM-IV description for disordered and non-disordered variants of adolescent antisocial behavior (American Psychiatric Association 1994, p. 88). The criteria used in the vignettes are consistent with those in DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association 2013).

The DSM symptom-only (SO) context presented DSM symptoms satisfying the criteria for conduct disorder without any other information about the youths. It was the stem vignette, forming the basic information for all versions. The youth was described as exhibiting 4 of 15 behavioral criteria symptomatic of CD, 1 more than is required for diagnosis. This vignette also provided demographic information of the adolescent’s age, gender, ethnicity and family background, as one might encounter in a brief clinical case summary. The SO vignette represented a case without any contextual information that might offer an explanation of the symptoms.

The DSM-internal dysfunction (ID) context added a second paragraph of contextual information to the DSM symptoms, suggesting that the youth’s behavior was likely the result of some internal dysfunction, and thus, according to DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994, pps. Xxi-xxii, 88), a disorder. This suggestion was made by having the behaviors (a) appear “irrational,” not effectively goal directed or proportional responses to environmental circumstances; (b) directed relatively indiscriminately at those in the environment; (c) persisting even when the individual was placed in a new, relatively benign environment; and (d) implying that the youth lacked empathy or concern for consequences, a criteria that has been incorporated into DSM-5 as a specifier “with or without callous and unemotional traits” (American Psychiatric Association 2013). The ID vignette was designed to effectively rule out many possible immediate environmental correlates of the behavior.

The DSM- environmental-reaction (ER) context added a different second paragraph, suggesting that the youth’s problematic behavior served survival functions in a dangerous environment filled with gang violence, and that his behavior disappeared when he was in a different environment. Specifically, to indicate that the youth’s antisocial behaviors were a reasonable, adaptive response to social circumstances, we chose one kind of situational determinant for which antisocial behavior could be a non-disordered reaction—a threatening school environment where gangs predominated. The vignette youth was terrified by the school violence and preyed on by one of the gangs, which led to him joining a rival gang for protection. In short, while the antisocial behaviors were consistent with diagnostic criteria for conduct disorder, the social circumstances suggested rational or adaptive, not pathological behavior. This yielded a 3 × 3 design. Each clinician was randomly assigned to receive one vignette. Appendix contains the three context conditions.

Survey Response Rates

Surveys returned without forwarding addresses, for deceased respondents, or those with incomplete responses were eliminated from the sample. For psychologists, psychiatrists and social workers, the response rates were 56.7% (n = 603), 45.8% (n = 483) and 58.2% (n = 454), respectively. We achieved an overall response rate of 53% and a total sample (N = 1540); the analytic sample was comprised of 39.2% psychologists, 32.1% psychiatrists, and 29.5% social workers.

Respondents were highly experienced clinicians, with a mean average of 21.7 years working in the field of mental health, and 20.7 years of experience working with children or adolescents. Over 96% were licensed to practice. Comparisons of this sample with the known characteristics of psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers in the United States indicated that a fairly representative sample was obtained. Details are reported in Hsieh (2001) and Pottick et al. (2007).

The mean age of respondents was 54 years (standard deviation = 9). About one-tenth were minorities: Asian or Pacific Islanders (3.8%), Black or African-Americans (2.5%), Latinos or Hispanics (2.5%), and other minorities (1%), while White/Caucasians comprised 90% of the study sample. The sample’s gender distribution was divided nearly equally (male =48%; female =52%).

Measures

Judgments of Treatment Effectiveness

The dependent variables were the respondent’s judgment about the effectiveness of 14 intervention approaches that are often used to treat antisocially behaving youth: “We would like to know your views on what intervention approaches are likely to be effective in working with [Carl/Carlos]. On a scale of one to nine, please indicate how effective you think each of the following approaches is likely to be.” The 9-point Likert scale contained anchors at 1 (not at all effective), 5 (somewhat effective), and 9 (extremely effective). A no opinion or don’t know category was omitted because respondents were asked to make the best possible judgment with the available information. The Likert-scale responses to each intervention approach were examined in two ways to ensure that findings were not an artifact of the construction of the dependent variable. For each given intervention, we calculated (1) the percentage of respondents who scored 5 (somewhat effective) through 9 (extremely effective), and (2) the median score. Their different statistical underpinnings translate into different practical meanings to understand decision-making. First, the proportion of the sample population that endorses the treatment as at least somewhat effective (≥5) is analogous to the sample population’s confidence in the efficacy of the treatment. Secondly, for each given treatment, half of the sample population judged the treatment above the median score and half below it. Consequently, the median score is analogous to the expected effectiveness of the treatment. On a scale of 1 through 9, median scores ranging from 7 through 9—in the top third of the scale—represent the sample population’s judgments of the most effective treatments. Those in the bottom third of the scale (≤ 3) represent treatments perceived as least effective, and those in the middle of the scale ( 4 to 6) represent moderately effective treatments. We decided against using mean scores of effectiveness for two reasons. First, because the distances among ordinal categories are unknown, median scores allow comparisons across conditions. Second, mean scores of agreement can be statistically different but clinically insignificant. The median score has intuitive significance, as it reveals where the effectiveness needle is located for clinicians—in the low, moderate or high range. Ultimately, clinicians must decide the likelihood that a treatment will be effective for a given youth, and whether to use an intervention. The proportion and median scores are ways to understand the probability that they may do so. We examined each intervention approach separately because clinical research on evidence-based practice, and clinical practice itself, tends to be organized around specific intervention strategies.

Our study sample was drawn from the national registers of licensed psychologists, psychiatrists and social workers. Accordingly, we used language of treatments that would be familiar to a wide range of clinicians. Some of the treatments correspond with core components of those in the evidence base, and others are commonly used but have not been systematically tested. Respondents in our study were asked about the following intervention strategies: psychiatric medication, psychodynamic psychotherapy, behavior modification, cognitive approaches, systems-oriented family therapy, parent management training, special education, prosocial peer groups, social problem-solving skills training, anger management training, case management, residential treatment, juvenile correctional facility, and community mobilization and planning.

Youth Race or Ethnicity

Vignette youth race or ethnicity of Black, White, or Hispanic was imbedded in the experimental design.

Analytic Strategy

Frequency and median scores of effectiveness level (1–9, Likert) on each of the 14 intervention approaches were compared in a series of bivariate analyses, stratifying context of DSM-internal dysfunction (ID), DSM-symptom only (SO), and DSM-environmental reaction (ER) and youth’s race or ethnicity of Black, White or Hispanic. Wilcoxon-signed rank tests were used to compare the paired difference in the median scores between two treatments as judged by individual professionals. Chi-square tests of differences in percentages of agreement (percent scores of 5 or above) and Mann-Whitney U tests of difference in the median scores were performed to compare professionals’ judgment of treatment effectiveness among the subgroups. Interquartile range (IQR) was calculated to indicate dispersion of values around the median scores. Analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All statistically significant differences that reached the level of p < .05 are indicated.

Results

Professionals’ Judgment of Treatment Effectiveness

Table 1 reports the distribution of respondents’ judgment of treatment effectiveness for each of the 14 treatments, presented in descending order of perceived effectiveness. Overall, respondents viewed (1) social problem-solving skills, (2) pro-social peer groups, and (3) anger management training as effective treatments for the youth. They were in the top third of median effectiveness scores (Median ≥ 7 of 9), and 86% to 90% of all respondents judging the treatments to be at least somewhat effective. Three treatments, residential treatment, psychodynamic psychotherapy, and juvenile correctional facility, were judged least effective, with median effectiveness scores in the bottom third (Median ≤ 3), with only about 13% to 40% of all respondents judged that the treatment would be at least somewhat effective. Eight treatments -- behavior modification, cognitive approaches, parent management training, systems-oriented family therapy, community mobilization and planning, case management, psychiatric medication, and special education -- were judged in the middle range of effectiveness, with median scores falling in the middle third (Median: 4–6), and a range of 45% to 80% judging the treatment to be at least somewhat effective. The paired tests showed median scores in the top third group, bottom third group and the remaining treatment group were all significantly different across these groups (all p < .05).

Judgment of Treatment Effectiveness in Three Contexts

Table 2 shows respondents’ judgment of treatment effectiveness for each of 14 treatments in each context. Behavior context was associated significantly with differences in effectiveness judgments in 13 out of 14 treatments by both measurement strategies: percentage and median scores. Cognitive approaches were judged equally effective in all three contexts, and did not reach statistical significance.

Within each of the ID and ER contexts respectively, respondents judged three different treatments as effective (median ≥ 7 of 9). In ID, they were (1) anger management training, (2) parent management training, and (3) behavior modification, with about 87% to 91% judging the treatment to be at least somewhat effective. In ER, they were (1) social problem-solving skills, (2) pro-social peer groups, and (3) community mobilization and planning, with about 88% to 95% judging the treatment to be at least somewhat effective. In the SO condition, clinicians made a wider search for solutions, judging 5 of the original 6 as effective, with about 86% to 90% viewing the each of those treatments as at least somewhat effective. They judged systems-oriented family therapy as effective (Median ≥ 7), and eliminated community mobilization and planning (Median = 5) when symptoms were presented in isolation.

There were consistent statistically significant differences by context for the treatments judged as least effective--residential treatment, psychodynamic psychotherapy, and juvenile correctional facility (p < .001). For each of these treatments, professionals judged that they would be more effective in the ID context than in the SO or ER (ID: % range = 18.6–57.1, Median range = 2–5; DSM-SO: % range = 13.5–42.6, Median range = 2–4; ER: % range = 6.7–31.9, Median range = 1–2).

Among the treatments judged as moderately effective, there also were statistically significant differences by context. Psychiatric medication was viewed as more effective for youth in the ID context (Median: 6 of 9), with nearly 84% of respondents judging that medication would be at least somewhat effective. In the ER context, medication was judged as much less effective (Median: 2 of 9), with only about 13% of respondents judging that it would be at least somewhat effective. In the SO context, professionals judged the effectiveness in between (Median: 5 of 9), with 59% of professionals judging the treatment to be at least somewhat effective. Case management and special education were judged as most effective in the SO context compared to the other contexts, respectively (Case management: % judging effective was 72.5% in SO compared to 60.9% in ER, p < .001 or 66.2% in ID, p = .04; Special education: % judging effective was 60.1% in SO, compared to 21.1% in ER, p < .001, or 56.6% in ID, p = .05).

To verify that the results of our study were not spurious, we conducted an internal analysis to investigate whether observed patterns of treatment effectiveness remained when we restricted the sample to clinicians who judged that the youth had a mental disorder (Ns from 931 to 967). Results showed that the effect of context on judgments of treatment effectiveness remained, with very few differences. Context affected judgments of treatment effectiveness in 12 out of 14 treatments, in contrast to 13 out of 14 treatments. In the ID context, the same three treatments were viewed as highly effective (anger management, behavior modification, and parent management training skills). Likewise, in the ER context, the same three treatments were judged as highly effective (social problem-solving skills, pro-social peer groups and community mobilization and planning). One difference was found: clinicians who viewed the youth in the harsh environment to have a mental disorder also judged anger management skills as a highly effective treatments (%: 83.1; Median: 7). In the more ambiguous symptom-only context, the same six treatments were judged as highly effective (anger management training, social problem-solving skills, parent management training, behavior modification, pro-social peer groups, and systems-oriented family therapy). Judgments of other treatments were also viewed identically. (Not tabled).

Youth’s Race or Ethnicity and Judgment of Treatment Effectiveness

Table 3 shows respondents’ judgments of treatment effectiveness for each of the 14 treatments for Black, Hispanic, and White youth. Race or ethnicity was not associated significantly with any of the 14 treatments by measures of percent or median scores; all of the treatments were judged equally effective for Black, Hispanic and White youth.

The judgments of treatment effectiveness were further examined for Black, Hispanic and White youth by context. In the ER and SO contexts, all 14 treatments were judged equally effective for Black, Hispanic and White youth. However, three treatments were judged to have higher effectiveness for youth in the ID context based on youth race or ethnicity. For White youth, systems oriented family therapy, psychiatric medication, and residential treatment were judged to be of significantly higher effectiveness, compared with Black or Hispanic youth (Systems oriented family therapy: Median: W = 7 vs. B or H = 6, p = .045; Psychiatric medication: Median: W = 7 vs. B or H = 6, p = .023); Residential treatment: Median: W, B, H = 5; mean: W, B, H = 4.5, 4.5, 5.1; p = .026). There were no race or ethnicity differences in the proportion of respondents who judged each of the three treatments to be at least somewhat effective (scores ≥5 of 9). (Not tabled).

Discussion

In this vignette-based mailed survey of 1540 experienced psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers, we investigated perceived effectiveness of 14 treatment interventions with an identical set of adolescent antisocial youth behaviors, with contextual information manipulated to suggest either a disorder (internal dysfunction) or non-disorder (environmental reaction), as described in the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994), as well as modifying the youth’s race or ethnicity. We examined if clinicians alter their judgments for youth exhibiting antisocial behavior based on contextual information and youth race or ethnicity, even among youth who are otherwise identical in terms of their diagnostic symptoms. Our first hypothesis that clinicians would appropriately distinguish between treatments with demonstrated effectiveness and those with little or no research evidence was partially supported. Our second hypothesis that clinicians would alter their judgments about treatment effectiveness based on the youth’s behavioral context was supported; they made distinctions that were sensitive to likely targets of intervention (i.e., person or environment). Our third hypothesis that treatments would be judged as equally effective for Black, White, and Hispanic youth was supported. However, when the antisocial behavior was presented in a context that suggested possible internal dysfunction, clinicians tended to view psychiatric medications, systems-oriented family therapy, and residential treatment as more effective for White youth than for Black or Hispanic youth.

Using two measurements of the judgment of treatment effectiveness provides us with unique information about the likelihood that clinicians might consider using any one of the fourteen treatments for the youth portrayed in the vignette. In one measurement case, the proportion of clinicians viewing the treatment as at least somewhat effective approximates the penetration of the level of acceptance of the particular treatment by the sample population. Conceptually, it roughly describes the confidence that the population has in the treatment. In the other measurement case, the median scores represent the expected effectiveness of the treatment by the sample population. Results showed that scores in the top, middle, and low third of effectiveness were statistically different from one another, so this measure represents the sample population’s view of how likely the treatment is to work—very likely (top third), moderately likely (middle third), and not very likely (bottom third). Taken together, these two measures may reveal any given treatment’s expected value. Treatments that inspire a lot of confidence (>85%) and are perceived as likely to succeed (median ≥ 7) could be considered by this sample of clinicians as normative best practices because they are treatments that clinicians would likely consider for this type of youth case.

With one exception, it appears that clinicians do appropriately distinguish treatments that are more effective than those that are not for youth with symptoms of conduct disorder, based on the research literature. This is especially significant because the sample is heterogeneous with regard to professional occupation (psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers). The effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral interventions for youth with conduct disorder is the most consistent finding in the EBP literature, with wide dissemination through government outlets (e.g., Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s National Guideline Clearinghouse 2016), professional literature across helping professions, and in a variety of scholarly articles and books. Our findings suggest that clinicians are aware of the utility of cognitive-behavioral approaches, as they judged social problem-solving skills training and anger management training as very effective treatments. Similarly, and consistent with research evidence, clinicians have less confidence in the effectiveness of residential treatment, psychodynamic psychotherapy and juvenile correctional facilities for youth displaying antisocial behavior, judging them as the least effective treatments. However, clinicians also judge prosocial peer group treatment as very effective; this is not well supported by the EBP literature. To establish prosocial group norms when groups are composed of antisocially behaving youth is difficult; substantial concerns remain for the potential harmful effects from more homogeneously composed groups. Some research has suggested that heterogeneously composed groups have better outcomes (as reviewed in Kazdin and De Los Reyes 2008, p. 234). Group treatment in agency-based practice, especially for youth, has proliferated, and is common and widespread. This suggests that clinicians may rely on their own experiences to inform their judgments of the best practices to use. EBP dissemination efforts have focused far more on what to do, than what not to do (Kazdin and De Los Reyes 2008), so it is uncertain whether clinicians are not aware of the research evidence, or are aware and set it aside because of their successful experiences with this group treatment approach, or are simply influenced by common organizational practices to manage large caseloads. Arguably, when answering the treatment effectiveness question, clinicians may be thinking about whether prosocial peer groups may be an effective intervention for this vignette youth, rather than considering whether there might be negative effects for the other youth associating with him.

It is generally agreed that a diagnosis should convey some clinically important information about a child’s condition beyond what was known before the problem was assigned to a diagnostic category, such as the prognosis and possible etiology, as well as the potential response to various possible treatments (Quay et al. 1987). Our findings show that for the identical set of behaviors meeting DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for conduct disorder, experienced clinicians reach very different judgments about treatment effectiveness based on contextual information suggesting that the behavior may be a manifestation of some internal dysfunction or a normal reaction to a problematic environment. This context effect with adolescent antisocial behavior also is found among psychiatrists, regarding the judgment of the presence of mental disorder, perceived course of illness, etiology, and treatment effectiveness (Hsieh and Kirk 2003). This raises questions about the validity of psychiatric diagnosis and evidence-based practices based exclusively on diagnostic criteria devoid of their social contexts. For research, the lack of attention to contextual factors is likely to contribute to the heterogeneity and false positives within diagnostic categories that is found in research studies (Hsieh and Kirk 2003; Jensen and Watanabe 1999; Wakefield et al. 2002). This potentially could thwart research studies of etiology, pathogenesis, and treatment (Robins and Guze 1970). It could also lead clinicians and organizations to select and apply specific EBP treatment modalities that would otherwise be judged as ineffective by experienced clinicians in psychiatry, psychology, and social work in the United States when the contexts of the behavioral symptoms are taken into account, as Hsieh and Kirk (2003) suggest. There have been advances in understanding the “coverability” of evidence-based practices for youth of diverse socio-demographic backgrounds by Chorpita et al. (2011). They examine the extent to which reported evidence-based practices test the practices on clients of different diagnoses, age range, gender, race or ethnicity, and treatment settings, identifying how relevant the tested treatment is for a given population. Findings reveal that when diagnosis only is considered, evidence based practices cover 100% of the population, but as the other parameters are included, treatments are far less generalizable, with 86% of the population not covered by the evidence-based practice when all parameters are included. Notwithstanding, current national guidelines developed by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry for practice decision-making, and published by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality in the National Guideline Clearinghouse (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2016), are predominantly disorder-based.

This underscores the importance for researchers and clinicians to consider the social or situational context of behavioral symptoms and the causal inferences that are made in both diagnostic assessment and treatment decisions. Our findings suggest that clinicians in practice make inferences about the causes of problems, such as whether the symptoms seem to be a manifestation of some internal dysfunction or a normal response to difficult environmental circumstances, and that they are sensitive to approaches that can target the potential causes. The findings of Chorpita et al. (2011), together with ours, call attention to the validity of the evidence-base for specific client populations. To our knowledge, there are no current data that evaluate the extent to which the behavioral context of clients may affect the generalizability of reported evidence-based practices. Attention to clients’ behavioral context may help to leverage current empirical findings to further improve how organizations and clinicians select what treatments and sets of treatments to use for their local client populations.

When the context suggested the youth’s problematic behavior may be due to an internal dysfunction, three interventions—anger management training, behavior modification, and parent management training—were seen by clinicians as the best treatment practices. With median scores of 7, and more than 85% of clinicians judging these treatments as highly effective, clinicians appear to value cognitive and behavioral interventions directed at the youth and family; these cognitive and behavioral approaches are strongly supported by the EBP literature for youths with conduct disorder diagnoses.

When the social context suggested the youth’s problematic behavior may be a normal reaction to a difficult social environment, three interventions—social problem solving skills, prosocial peer groups, and community mobilization and planning—were seen by clinicians as the best treatment practices. The nearly universal endorsement of prosocial peer groups and social problem solving skills at 95% and 93% respectively, and median scores of 8 is noteworthy, as it appears that clinicians value interventions in this context that aim to alter the youth’s immediate social environment or enhance his ability to cope or problem-solve. Unfortunately, the social context depicted in the ER vignettes resembles the day-to-day reality of many inner city youth faced with prevalent gang-related community violence. Programs that reach into the community are frequently developed through statewide or national policies, or city and county initiatives. However, there is limited understanding of their effectiveness because of the lack of controlled research methods to test them. Community mobilization and planning would not likely be on any list of evidence-based practices, yet for these experienced clinicians, these environmental interventions were critical for the youth experiencing a difficult social environment.

The attraction of the multimodal treatment approach of MST, which has garnered a strong following of organizations and practitioners, may be its attention to systemic problems in the larger environment—in families, schools, and correctional and child welfare settings. It also has demonstrated well-established outcomes in the United States (Fonagy et al. 2015; McCart and Sheidow 2016). Our findings suggest that clinicians may be attuned to the need for environmental change through political and community action, in addition to clinical work with the youth or youth in groups. This is consistent with practice parameter recommendations that encourage the use of multimodal interventions that address multiple foci from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (Steiner et al. 1997), but it also suggests that clinicians and program planners may need more systematic research on the mechanisms of change in interventions that attend to the family and community contexts of youth with conduct disorder symptoms (Ollendick and Shirk 2011) to meet their needs in the practice world. In addition, recent research and scholarship has shown the value of developing service arrays that incorporate effective elements of programs and treatments (Bernstein et al. 2015), so investigating the mechanisms of, and outcomes from, combining identified practices in our study may be productive. Finally, these findings reveal that clinicians were discerning the youth-in-context, identifying treatments that could be effective based on the client’s reactions to a problematic environment, not exclusively on the diagnostic symptom profile.

When clinicians were provided with DSM behavioral symptoms only, they discriminated less well among treatments, judging six treatments --social problem solving skills, prosocial peer groups, anger management skills training, behavior modification, parent management training and systems-oriented family therapy-- as highly effective. Without context, community mobilization and planning dropped from the best practices, while systems-oriented family therapy rose as one of the best treatment practices. Without reference to context, clinicians are less selective about which treatments would be of the most expected value. In the practice world, treatment indecision could have cost implications for clinicians and organizations, as well as for youth and families.

When we restricted our analysis to clinicians who judged that a mental disorder was present, we found they differentially valued treatments that addressed the youth’s distinct behavioral context; without context, they made a wider search for possible solutions. This suggests that experienced clinicians rely on information other than diagnosis alone to select appropriate treatments. Regardless of the existence of a mental disorder, clinicians appear to be inferring causal factors in the youth’s problem behavior. The gains in research evidence on the effectiveness of multimodal treatment approaches for youth with conduct disorder align with these clinical views from the field. This strongly suggests that accelerating research on these contextually based practices would be beneficial to clinicians and the youths and families whom they treat.

Our findings demonstrate that youth’s race or ethnicity was not significantly associated with any of the 14 judgments of treatment effectiveness, and that clinicians were applying judgments similarly. This may be indicative of a trend toward cultural sensitivity among clinicians, or perhaps an awareness of the evidence-base that suggests it is justifiable to believe that established treatments could work about equally well among youth of different races or ethnicities. Certainly, there is no evidence in the extant literature to show that treatments would be less effective for one racial or ethnic group over another, and our results suggest that clinicians believe that as well.

However, when contextual information suggested the likely presence of some internal dysfunction, clinicians judged systems-oriented family therapy, psychiatric medication, and residential treatment as more effective for the White youth than for the Black and Hispanic ones. Our findings suggest that clinicians may make implicit assumptions about the family situations of minority youth when context suggests that the symptoms are a result of internal dysfunction. It is possible that they believe that many minority youth come from single-parent households, and households that are less psychologically minded, and more difficult to engage in family work, or to involve in the required monitoring and oversight of psychotropic medication for their children. In addition, they may view language as a barrier to engagement.

The possible bias in judgments about medication is intriguing because national data show that the rates of psychotropic medication use for White children and adolescents are higher than for African American and Hispanic ones (Olfson et al. 2002). This disparity may reflect the general finding that minority individuals are less likely to access mental health services at the community level (Alegria et al. 2015; Alegria and McGuire 2003), but there may be unexplored, subtle influences at the clinical judgment level as well: if psychiatric medication is perceived by clinicians as more effective for White youth compared to minority youth, they would be more likely to prescribe it as a treatment for them. It may be that clinicians view antisocial behavior in White youth as resulting from some biochemical imbalance in the brain more than in Black or Hispanic youth. This is consistent with findings in a previous study using the same data; Pottick et al. (2007) found that, controlling on context, clinicians were significantly more likely to judge a White youth as having a mental disorder than a Black or Hispanic youth. This judgment pattern also could be due to clinicians’ perceived differential base rates of adolescent antisocial behavior in White youth compared to others, or to cultural stereotypes. A recent systematic review of the literature on implicit racial and ethnic bias among health care professionals (Hall et al. 2015) showed how unconscious biases about race affected a number of different medical treatment decisions, and that stressful working conditions may exacerbate their influence. It is also noteworthy that the vast majority (90%) of the clinicians in this national survey are White, and the influence of their race or ethnicity on perceived treatment effectiveness for White youth compared to others is unclear. Taken together, these findings suggest the troubling possibility that biases in clinical decision-making based on client race or ethnicity may be occurring at both the diagnostic assessment and treatment phases.

By understanding how practicing clinicians are making judgments about the use of possible treatments for a given case, we can begin to uncover how they may be synthesizing information about best treatment practices. In the end, clinicians have to integrate information from controlled research studies, effectiveness studies in practice settings, and their own experiences in clinical work. Our results suggest that in making these determinations, they are considering the social context in which the symptomatic behaviors occur, rather than basing their judgment solely on symptom clusters of a given diagnosis or evidence-based practices aimed at behavioral symptom reduction, at least in the case of adolescent antisocial behavior. These findings are instructive because existing practice parameters from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry recommend that a flexible application of modalities should be provided, but the parameters provide little guidance for how they might be packaged in everyday practice to address targeted changes in different contextual situations (Steiner et al. 1997). Our findings also show that judgments about the effectiveness of treatment for minority youths is influenced also by context. Yet, appropriate interventions and the effective delivery of services to youths and their families of different races and ethnicities depend on bias-free formulations of effectiveness. At the same time, uncertainties still remain as to whether evidence-based treatment practices normed on the White population are equally efficacious for minority clients.

Our study provides information on the variation or consistency in clinical judgments of effectiveness, but it cannot provide good information on the use of these judgments in practice. One area of intervention research where gaps exist is in understanding the processes of uptake of evidence-based practices. Recent research has suggested that clinicians may be constrained in adopting best practices by the ecology of their organizations, and that our field has relied too heavily on assigning responsibilities to clinicians alone (Raghavan et al. 2008). Researchers conducting empirical studies of organizational-level interventions to increase the uptake of EBP approaches and improve client outcomes may help provide clinicians with needed agency support (Glisson et al. 2016; Proctor et al. 2011). Other researchers have found that organizational factors can influence the delivery of medication treatment, beyond clinical need factors of patients (Warner et al. 2005). Our findings suggest that clinicians may be influenced by tradition, and organizational norms and routine practices in addition to their awareness of the empirical literature. They may be shouldering the large burden of implementation decisions without sufficient guidance on how to weigh disparate information practiced in agencies and disseminated in the literature. We agree with Ollendick and Shirk (2011) who argue that we need to “identify important developmental, contextual and relationship variables that qualify these efficacious findings and encourage the pursuit of additional process and outcome research,” and who call for “developing principle-based interventions that draw on these specific evidence-based interventions, but move beyond and unify them” (p. 771). Much clinical research assesses the evidence base on clients with given clinical profiles without regard to their life circumstances. Clinicians in our study were sensitive to the importance of contextual information, suggesting that basic and intervention research may need to take context into account in the selection criteria that move beyond diagnostic syndromes exclusively. Deliberate consideration of behavior contexts in addition to symptom features could potentially improve both research and practice. For example, it could reduce the heterogeneity of the “syndrome” being studied, and disparate findings could emerge as a result. It might also give clinicians needed validation to use their clinical intuition to assess human behavior in context when trying to understand their youth clients, and to decide how best to intervene.

Our findings suggest another productive line of research. As family members are normally the gateway to engagement of their children in treatment, future studies might explore the influence of context on their judgments of treatment effectiveness. For judgments of the existence of mental disorder, research has demonstrated that laypersons often make similar distinctions as professionals (Wakefield et al. 2006; Garb 1998; Marsh et al. 2014), and some scholars think that the similarities may reflect general reasoning processes (Marsh et al. 2014). From these findings, we expect that parents may be equally sensitive to the importance of context for making judgments about treatment. Program planners and clinicians alike need information about how parents view treatment possibilities for their children to improve community outreach and tailor clinical practice interventions.

Our study was designed to represent the population of youth that would normally come into a community agency, and for which clinicians would have to make decisions about treatment. Some of these youth might be seen as having a mental disorder, and some not. Our previous studies showed that clinicians appropriately distinguished mental disorder from non-disorder in a manner consistent with the inclusionary and exclusionary guidelines in the DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association 1994, pp. xxi-xxii, 88). More than 90% of clinicians reported that the youth had a mental disorder when the problem appeared to be due to an internal dysfunction, while only one third reported a mental disorder when the problem seemed to be due to a harsh environment. When they were provided with behavioral symptoms only and no context, they seemed more uncertain, judging disorder in about 70% of the cases (see, for example, Kirk et al. 1999).

The treatment approaches reported in the study did not have the identical names as the evidence-based practice programs described in the literature and that have been designed for, and tested with, youth with conduct disorder, such as Functional Family Therapy (for example, Fonagy et al. 2015). This was intentional. The sample was drawn from rolls of clinicians in the fields of psychology, psychiatry, and social work, so the treatment choices in the study were ones that clinicians were likely to know and in which they had received some training, including general skills of cognitive, behavioral, family therapy, and group work. They also roughly corresponded to treatments in the evidence-base (e.g., parent management training vs. behaviorally oriented parent management training programs (see Brestan and Eyberg 1998). The treatments also included those in routine use, but without much scientific evidence to back them up (residential care, juvenile justice facilities) to examine their perceived effectiveness by clinicians.

Because of our measurement, our findings may point to common principles of treatments perceived as effective for youth with conduct disorder. In resource-constrained agencies where programs of evidence-based practices may be in short supply, program planners and clinicians may need to build systematically on these basic clinical skills to incorporate change elements that can be easily adopted into routine care. With other scholars and researchers, we lament the void in our understanding of the mechanisms of change for many of the treatments, including evidence-based ones (Kazdin and De Los Reyes 2008). Only with this knowledge can a practitioner-centered knowledge base be developed and systematically tested in the field to improve the effective delivery of treatments.

Judgments of treatment effectiveness may vary due to factors other than context. A large body of literature has shown that men and women perceive things differently, as do individuals of different ages, or those of different races or ethnicities. Clinicians trained in different occupations or with different specializations may exhibit different professional socialization processes that affect clinical judgments of treatment effectiveness. It is possible, for example, that social workers may view community organization and planning as more effective than other professionals, or that psychologists, with explicit training in cognitive approaches, may view that treatment as more effective than others. In an earlier study on this data set, researchers found that psychoanalytic or psychodynamic training increased the salience and reporting of disorders: clinicians who utilized psychoanalytic or psychodynamic approaches (in contrast to those with behavioral/cognitive or eclectic orientations) were more likely to judge that a mental disorder was present when the context suggested that the youth was normal, and responding to a harsh environment (Pottick et al. 2007). Future research that explores additional correlates of judgments of treatment effectiveness could provide further insight into treatment decision-making to improve educational training and clinical service delivery.

The results of this study need to be viewed in the context of the limitations of methodology. As mental health researchers have recognized the value of experimental control to validate and build on findings of traditional survey and ethnographic methods, the use of realistic case vignettes to study mental health problems among children has grown in both national samples (Pottick et al. 2007; Pescosolido et al. 2008) and regional and local ones (Chavez et al. 2010; Mukolo and Heflinger 2011). However, such analogue methods are only proxies for what actually occurs in clinical practice situations, though they provide powerful ways of discovering relationships that may not otherwise be readily detectable. Brief case vignettes do not replicate the complexities of a real clinical case, with clinical interviews that build on information in clinical files. Additionally, vignette methods are subject to many correlated factors that may be incorporated unknowingly into the vignettes, potentially complicating interpretation of results. We designed the vignettes to represent relatively clear cases involving one or another kind of causation. A real clinical case contains ambiguities, contradictory evidence, and multiple causal pathways that a vignette cannot capture. We achieved a response rate of 53%; although comparisons with national data were assuring, our sample of respondents could differ from non-respondents in unmeasured ways that might also be associated with judgments of treatment effectiveness, so we must remain cautious in generalizing the results until further confirmation is obtained. We only studied conduct disorders among youth; the study should be replicated with other disorders to see whether the observed effects are magnified or attenuated under different diagnostic conditions, and with different age groups of clients. However, for practice research, experimentally controlled vignette methods are promising, as they can discern mechanisms of clinical decision-making relatively efficiently to improve practice in a timely way (Converse et al. 2015). Finally, we did not include multicomponent treatment approaches in our list of treatment possibilities, relying instead on familiar terminology across multiple professional groups. Future research should examine these approaches as they are the ones that have become, more well-established in recent years for antisocially behaving youth (McCart and Sheidow 2016).

Despite these limitations, the data from this study suggest that the youth’s behavioral context may guide clinicians in distinguishing between more or less effective treatments and their potential value, even among youth with identical DSM-symptoms. Professional norms and expectations to deliver treatments and services equitably, and reduce racial and ethnic disparities, have been effective on the surface, but implicit racial and ethnic biases about treatment effectiveness may inadvertently arise as more complex information about the context of a given case is assessed. Shedding light on clinicians’ treatment decision-making processes, this study points to the remaining challenges to develop treatment evidence and training that will provide clinicians with information to equitably treat the whole person, as well as the syndrome.

References

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2016). National Guideline Clearinghouse. http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=48378&search=concuct+disorder. Accessed 20 Feb 2017.

Alegria, M., & McGuire, T. (2003). Rethinking a universal framework in the psychiatric symptom-disorder relationship. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44(3), 257–274.

Alegria, M., Green, J. G., McLaughlin, K. A., & Loder, S. (2015). Disparities in child and adolescent mental health and mental health services in the U.S. http://blog.wtgrantfoundation.org/post/114541733572/new-report-disparities-in-child-and-adolescent. Accessed 20 Feb 2017.

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (2015). Recommendations about the use of psychotropic medications for children and adolescents involved in child-serving systems. https://www.aacap.org/App_Themes/AACAP/docs/clinical_practice_center/systems_of_care/AACAP_Psychotropic_Medication_Recommendations_2015_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 20 Feb 2017.

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (2016). Frequently Asked Questions: What is the best way to treat a child with conduct disorder? https://www.aacap.org/aacap/Families_and_Youth/Resource_Centers/Conduct_Disorder_Resource_Center/FAQ.aspx#cdfaq3. Accessed 20 Feb 2017.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV (4th ed.). Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Publishing.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed.). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing.

Bernstein, A., Chorpita, B. F., Daleiden, E. L., Ebesutani, C. K., & Rosenblatt, A. (2015). Building an evidence-informed service Array: Considering evidence-based programs as well as their practice elements. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(6), 1085–1096.

Bisman, C. (2014). Value-guided practice for a global society. New York: Columbia University Press.

Boxer, P., & Frick, P. J. (2008). Treating conduct problems, aggression, and antisocial behavior in children and adolescents: an integrated view. In Handbook of evidence-based therapies for children and adolescents (pp. 241–259): Springer US.

Brestan, E. V., & Eyberg, S. M. (1998). Effective psychosocial treatments of conduct-disordered children and adolescents: 29 years, 82 studies, and 5,272 kids. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 27(2), 180–189.

Chavez, L. M., Shrout, P. E., Alegria, M., Lapatin, S., & Canino, G. (2010). Ethnic differences in perceived impairment and need for care. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(8), 1165–1177.

Chorpita, B. F., Bernstein, A., & Daleiden, E. L. (2011). Empirically guided coordination of multiple evidence-based treatments: An illustration of relevance mapping in children’s mental health services. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79, 470–480.

Converse, L., Barrett, K., Rich, E., & Reschovsky, J. (2015). Methods of observing variations in Physicians’ decisions: The opportunities of clinical vignettes. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 30, 586–594.

Costello, E. J., He, J. P., Sampson, N. A., Kessler, R. C., & Merikangas, K. R. (2014). Services for Adolescents with Psychiatric Disorders: 12-month data from the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent. Psychiatric Services, 65(3), 359–366.

De Los Reyes, A., & Marsh, J. K. (2011). Patients’ contexts and their effects on Clinicians’ impressions of conduct disorder symptoms. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 40(3), 479–485.

Dishion, T. J., McCord, J., & Poulin, F. (1999). When interventions harm - peer groups and problem behavior. American Psychologist, 54(9), 755–764.

Eyberg, S. M., Nelson, M. M., & Boggs, S. R. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37(1), 215–237.

Fonagy, P., Cottrell, D., Phillips, J., Bevington, D., D., G., & Allison, E. (2015). What works for whom?: A critical review of treatments for children and adolescents (2nd ed.). New York: The Guildford Press.

Garb, H. N. (1998). Studying the clinician: Judgment research and psychological assessment. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Glisson, C., Williams, N. J., Hemmelgarn, A., Proctor, E., & Green, P. (2016). Aligning organizational priorities with ARC to improve youth mental health service outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(8), 713–725.

Hall, W. J., Chapman, M. V., Lee, K. M., Merino, Y. M., Thomas, T. W., Payne, B. K., et al. (2015). Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: A systematic review. American Journal of Public Health, 105(12), E60–E76.

Ho, J. K., McCabe, K. M., Yeh, M., & Lau, A. S. (2011). Evidence-based treatments for conduct problems among ethnic minorities. In Clinical handbook of assessing and treating conduct problems in youth (pp. 455–488). New York: Springer.

Huey, S. J., & Polo, A. J. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for ethnic minority youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37(1), 262–301.

Jensen, P. S., & Watanabe, H. (1999). Sherlock Holmes and child psychopathology assessment approaches: The case of the false-positive. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(2), 138–146.

Hsieh, D. K. (2001). Distinguishing mental disorders from problems in living: The effect of social context in judgments of adolescent antisocial behavior, Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, Vol. 61 (12–B).

Hsieh, D. K., & Kirk, S. A. (2003). The effect of social context on psychiatrists' judgments of adolescent antisocial behavior. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 44(6), 877–887.

Hsieh, D. K., & Kirk, S. A. (2005). The limits of diagnostic criteria: The role of social context in clinicians’ judgments of mental disorder. In S. A. Kirk (Ed.), Mental disorders in the social environment: Critical perspectives. (pp. 45–61). New York: Columbia University Press.

Jensen-Doss, A., Hawley, K. M., Lopez, M., & Osterberg, L. D. (2009). Using evidence-based treatments: The experiences of youth providers working under a mandate. Professional Psychology-Research and Practice, 40(4), 417–424.

Kataoka, S. H., Zhang, L., & Wells, K. B. (2002). Unmet need for mental health care among US children: Variation by ethnicity and insurance status. American Journal of Psychiatry, 159(9), 1548–1555.

Kazdin, A. E. (2003). Problem-solving skills training for parent management training for conduct disorder. In A. E. Kazdin & J. R. Weitz (Eds.), Evidence-based psychotherapies for children and adolescents (pp. 241–262). New York: Guilford Press.

Kazdin, A. E., & De Los Reyes, A. (2008). Conduct disorder. In R. J. Morris & T. R. Kratochwill (Eds.), The practice of child therapy (4th ed., pp. 207–247). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Kirk, S. A., Wakefield, J. C., Hsieh, D. K., & Pottick, K. J. (1999). Social context and social workers' judgment of mental disorder. Social Service Review, 73(1), 82–104.

Marsh, J. K., De Los Reyes, A., & Wallerstein, A. (2014). The influence of contextual information on lay judgments of childhood mental health concerns. Psychological Assessment, 26(4), 1268–1280.

Marsh, J. K., Burke, C. T., & De Los Reyes, A. (2016). The sweet spot of clinical intuitions: Predictors of the effects of context on impressions of conduct disorder symptoms. Psychological Assessment, 28(2), 181–193.

McCart, M. R., & Sheidow, A. J. (2016). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for adolescents with disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 45(5), 529–563.

Merikangas, K. R., He, J. P., Brody, D., Fisher, P. W., Bourdon, K., & Koretz, D. S. (2010a). Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders among US children in the 2001-2004 NHANES. Pediatrics, 125(1), 75–81.

Merikangas, K. R., He, J. P., Burstein, M., Swanson, S. A., Avenevoli, S., Cui, L. H., et al. (2010b). Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 980–989.

Miranda, J., Bernal, G., Lau, A., Kohn, L., Hwang, W. C., & LaFromboise, T. (2005). State of the science on psychosocial interventions for ethnic minorities. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 1, 113–142.

Mukolo, A., & Heflinger, C. A. (2011). Factors associated with attributions about child health conditions and social distance preference. Community Mental Health Journal, 47(3), 286–299.

Olfson, M., Marcus, S. C., Weissman, M. M., & Jensen, P. S. (2002). National trends in the use of psychotropic medications by children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(5), 514–521.

Ollendick, T. H., & Shirk, S. R. (2011). Clinical interventions with children and adolescents: Current status, future directions. In D. H. Barlow (Ed.), Oxford handbook of clinical psychology (pp. 762–788). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pescosolido, B. A., Jensen, P. S., Martin, J. K., Perry, B. L., Olafsdottir, S., & Fettes, D. (2008). Public knowledge and assessment of child mental health problems: Findings from the National Stigma Study-Children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(3), 339–349.

Popescu, I., Xu, H. Y., Krivelyova, A., & Ettner, S. L. (2015). Disparities in receipt of specialty services among children with mental health need enrolled in the CMHI. Psychiatric Services, 66(3), 242–248.

Pottick, K. J., Wakefield, J. C., Kirk, S. A., & Tian, X. (2003). Influence of social workers' characteristics on the perception of mental disorder in youths. Social Service Review, 77(3), 431–454.