Abstract

While a plethora of cognitive behavioral empirically supported treatments (ESTs) are available for treating child and adolescent anxiety and depressive disorders, research has shown that these are not as effective when implemented in routine practice settings. Research is now indicating that is partly due to ineffective EST training methods, resulting in a lack of therapist competence. However, at present, the specific competencies that are required for the effective implementation of ESTs for this population are unknown, making the development of more effective EST training difficult. This study therefore aimed to develop a model of therapist competencies for the empirically supported cognitive behavioral treatment of child and adolescent anxiety and depressive disorders using a version of the well-established Delphi technique. In doing so, the authors: (1) identified and reviewed cognitive behavioral ESTs for child and adolescent anxiety and depressive disorders, (2) extracted therapist competencies required to implement each treatment effectively, (3) validated these competency lists with EST authors, (4) consulted with a panel of relevant local experts to generate an overall model of therapist competence for the empirically supported cognitive behavioral treatment of child and adolescent anxiety and depressive disorders, and (5) validated the overall model with EST manual authors and relevant international experts. The resultant model offers an empirically derived set of competencies necessary for effectively treating children and adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders and has wide implications for the development of therapist training, competence assessment measures, and evidence-based practice guidelines for working with this population. This model thus brings us one step closer to bridging the gap between science and practice when treating child and adolescent anxiety and depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Evidence-Based Practice and Empirically Supported Treatments

The field of clinical psychology is in an age of evidence-based practice (EBP), with policy makers highlighting the use of EBP as a central tenet of health care delivery (Institute of Medicine 2001). EBP in psychology is defined as “the integration of the best available research with clinical expertise, in the context of patient characteristics, culture, and preferences” (American Psychological Association 2005, p. 1). To engage in EBP, a therapist must identify a treatment that has proven efficacy for the client’s target disorder and implement this in a manner that is sensitive to the client characteristics and his or her needs or preferences (Spring 2007). Treatments with proven efficacy include those which meet empirically supported treatment (EST) criteria set out by the American Psychological Association (APA) Division 12 Task Force on Promotion and Dissemination of Psychological Procedures (Chambless et al. 1998; Chambless and Hollon 1998; Chambless et al. 1996). In general, ESTs are those which have been found to be effective at treating a target disorder within the context of a methodologically rigorous randomized control trial (RCT) comparing the treatment manual to either an active control treatment or waitlist control condition (See Chambless and Hollon 1998).

Dissemination and Uptake of Empirically Supported Treatments

While there are a plethora of ESTs available for a large range of psychological disorders, research has confirmed that they are not often utilized by therapists offering therapy in routine clinical practice (RCP; Goisman et al. 1999), and when they are implemented, client outcomes are inferior to those seen in the RCTs in which the EST was initially evaluated (e.g., Stewart and Chambless 2009). With mounting evidence to suggest that EST training offered to therapists in RCPs is inadequate to produce the level of therapist competence necessary to effectively implement such ESTs (Herschell et al. 2010), there is an urgent call for the development of more effective EST training (Rakovshik and McManus 2010). However, to move forward with this endeavor, the field requires a clear understanding of the specific therapist competencies necessary for effectively implementing ESTs (Rector and Cassin 2010).

Therapist Competence and Competencies

Interestingly, the conceptualization of competence in professional psychology has only recently received attention, as a part of what is now termed the competencies-based movement in psychology (Kaslow et al. 2004; Roberts et al. 2005). The competencies-based movement is a paradigmatic shift occurring in professional psychology that promotes the understanding, education, and assessment of professional competence in psychological practitioners (Roberts et al. 2005). Competence in professional psychological practice is defined within this movement as “the habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values, and reflection in daily practice for the benefit of the individual and community being served” (Epstein and Hundert 2002, p. 227). Furthermore, competence is made up of elements of competence, known as competencies, which include relevant knowledge, skills and attitudes, and their integration (Kaslow 2004; Kaslow et al. 2004). In this manner, the term competence refers to an individual’s overall capability as a professional psychologist, whereas competencies are critical components of this overarching capability, such as the ability to engage a client, knowledge about common psychological disorders, and the ability to intervene appropriately (Kaslow et al. 2004).

Since this definition was coined, there have been several attempts to operationalize the specific competencies necessary for competent practice in psychology regardless of therapeutic orientation (e.g., American Psychological Association 2005; Rodolfa et al. 2005). While these offer some understanding of the general kinds of competencies necessary to implement psychotherapy of any theoretical orientation and are beginning to be used to improve psychologist training in clinical programs, they do not offer insight into the competencies necessary for implementing the procedures and techniques used in specific ESTs from particular therapeutic orientations for targeted client populations (Rector and Cassin 2010). For a conceptualization of therapist competencies to be useful for the development of effective EST training, it should include reference to both general therapeutic competencies and EST-specific competencies (Rector and Cassin 2010).

Competencies for Empirically Supported Treatments

Roth and Pilling (2008) pioneered this endeavor, with the development of a model of therapist competencies necessary for the empirically supported cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)-orientated treatment of two of the most common psychological disorders in adulthood, anxiety disorders, and depression. CBT was the therapeutic orientation chosen, as it has received the most empirical support for the target population (Roth and Pilling 2008). This model listed competencies under five competency domains, one of which dealt with general therapeutic competencies that would be used in any psychotherapy intervention, and four domains dealing specifically with competencies necessary for implementing CBT (Roth and Pilling 2008).

The general set of competencies was termed Generic Therapeutic Competencies, and the four CBT-related domains were named Basic CBT Competencies, Specific CBT Techniques, Problem-specific Competencies, and Metacompetencies (Roth and Pilling 2008). Generic Therapeutic Competencies include activities that are employed in all forms of psychotherapy, such as working ethically with clients, knowledge about mental health conditions, forming, and maintaining a good therapeutic alliance with the client, and conducting a generic assessment. Basic CBT Competencies include activities that establish the structure and context for the implementation of Specific CBT Techniques such as setting an agenda and agreeing on goals for the intervention. Specific CBT Techniques include the central techniques employed in effective CBT interventions for adult anxiety disorders and depression such as Exposure techniques and Guided Discovery. Problem-specific Competencies list the specific CBT manuals that are effective with each of the adult anxiety and depressive disorders. These approaches are divided into both low- and high-intensity treatments. Low-intensity treatments include self-help and guided self-help treatments, and high-intensity treatments are considered to denote formal psychotherapy delivered by a therapist. Metacompetencies enable therapists to adapt the implementation of processes and techniques in a manner that is responsive to the needs of an individual client and to implement therapy in a coherent and informed manner.

The method used to develop the Roth and Pilling (2008) model involved a version of the Delphi technique. The Delphi technique is a well-established and widely used procedure in health care service provision that draws together both empirical evidence and iterative expert review to achieve consensus regarding effective and ineffective treatment approaches (Norcross et al. 2010), guidelines for best practice (e.g., Garland et al. 2008; Morrison and Barratt 2010) and to determine professional competencies (e.g., Morrison and Barratt 2010). Using such a procedure ensured that the competencies in the model were closely related to the empirically supported literature and to current CBT practices (Roth and Pilling 2008). The Roth and Pilling (2008) methodology included: (1) reviewing the literature to identify the most empirically supported CBT treatments for each of the adult anxiety and depressive disorders; (2) reviewing each of these treatments and extracting the competencies necessary to implement each EST manual in an evidence-based manner; (3) sending these lists to the authors of the respective EST manuals for review and validation, and (4) generating an overall model of therapist competencies for the empirically supported CBT treatment of any adult anxiety or depressive disorder in conjunction with an Expert Reference Group (ERG). This ERG consisted of local experts in anxiety and/or depression-related research, training, and/or professional practice (Roth and Pilling 2008).

The strength the Roth and Pilling (2008) method is that it distilled the core competencies required for the effective cognitive behavioral treatment of adult anxiety and depressive disorders, and thus, the resultant model offers enormous insight into the exact competencies that need to be taught in EST dissemination training programs. A training curriculum for therapists in RCP has been developed based upon this model as part of the UK-based, nationwide dissemination program, Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT; Roth and Pilling 2008). While this program is still in its ‘roll out’ phase, preliminary data indicate that therapist competence increases following training (McManus et al., in press) and 50–60% of clients seeking treatment from IAPT-trained therapists are diagnosis free following treatment (Clark et al. 2009). Such results highlight the importance of distilling core competencies required for the use of ESTs for specified populations and using these to inform dissemination training programs.

Child and Adolescent Anxiety and Depressive Disorders EST Competencies

As in the adult literature, anxiety and depressive disorders are among the most common seen in children and adolescents (e.g., Ford et al. 2003). In the case of child and adolescent anxiety disorders, CBT is the most empirically supported treatment (Beidel et al. 1998, 2000; Cohen et al. 2004, 2006; Deblinger and Heflin 1996; Hudson et al. 2009; Kendall and Hedke 2006; Kendall et al. 2008; March and Mulle 1998; Ollendick et al. 2009; Ost and Ollendick 2001; Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) Team 2004; Pincus et al., in press; Pincus et al. 2008; Rapee et al. 2006b; Silverman et al. 2008b). In the case of youth depression, both CBT and Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) are considered to be the most empirically supported treatments for this population (e.g., Brent and Poling 1997; Brent et al. 1997; Clarke et al. 1990; Curry et al. 2005; Ferdon and Kaslow 2008; Rohde et al. 2004; TADS Team 2004).

Even though cognitive behavioral ESTs are available for all of the child and adolescent anxiety and depressive disorders, many youths suffering with such disorders are left untreated or are treated with inferior non-EST approaches in RCP (Goisman et al. 1999). If these disorders are left untreated or are not treated effectively, they can: (1) persist into adulthood (e.g., Kessler et al. 2005), (2) develop into substance abuse disorders, and/or suicidality later in life (Angold et al. 1999; Brent 1995; Rudd et al. 2004), and (3) cost the government large amounts in long-term health care provision (e.g., Weissman et al. 1999) and welfare to compensate for an inability to work or live independently due to their chronic disorder presentation (Last et al. 1997; Waghorn et al. 2005).

While the empirically supported CBT treatments for children and adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders are usually downward extensions of the adult CBT treatments for these same disorders, there is a substantial degree of difference between the effective delivery of these treatments and those developed for adults. Several differences are listed later. Firstly, when working with children and adolescents, the therapist must be aware of and be able to adapt the nature and implementation of the CBT strategies and session pacing to the level of social, cognitive, and emotional development that the child or adolescent presents with (e.g., Kingery et al. 2006; Ollendick and Hovey 2010; Sauter et al. 2009). Secondly, the therapist must consider family environment factors that may be maintaining the disorder in the child or adolescent and appropriately intervene on these (e.g., Sheeber et al. 2007; Wood et al. 2003). Finally, the therapist must also respond to ethical requirements with regard to providing psychotherapy to minors (e.g., Curry and Reinecke 2010).

As can be seen, effectively treating children and adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders requires an additional set of competencies that is not required in the empirically supported treatment of adults and as such, are not represented in the Roth and Pilling (2008) model. The Roth and Pilling (2008) model is limited in terms of its utility for developing therapist training programs for the empirically supported treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Since there is currently no model that represents these child- and adolescent-specific therapist competencies, this study aims to develop a model of therapist competencies for the empirically supported cognitive behavioral treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders using a similar Delphi technique methodology as the one employed by Roth and Pilling (2008).

Method

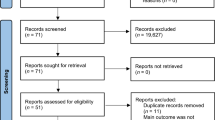

Identifying Empirically Supported CBT Treatments

In order to identify cognitive behavioral ESTs for child and adolescent anxiety disorders and depression, the authors first searched a series of EST reviews of child and adolescent anxiety disorder (Barrett et al. 2008; Silverman et al. 2008a, b) and depression (Ferdon and Kaslow 2008) treatments. These reviews ranked treatments into the four EST efficacy classes outlined by the APA Division 12 Task Force (Chambless et al. 1996, 1998; Chambless and Hollon 1998). Secondly, the authors updated this list by replicating the search strategies outlined in these review articles for the period between Jan 2006 to Jan 2010 and added those more recent treatments to the EST lists produced by the review articles.

In an attempt to limit the cognitive behavioral ESTs included to those with the strongest evidence base, the authors included only those that demonstrated at least probable efficacy at treating their target disorder (i.e., we selected those treatments ranked as either Probably Efficacious or Well Established). It is important to note that treatments that had been compared to an active, non-CBT control treatment were favored over those which had compared CBT to a waitlist control. ESTs that were included can be seen in Table 1, along with the trial in which they were evaluated, the primary diagnosis of subjects treated in the trial, and their ages. As can be seen in Table 1, ESTs targeting each of the child and adolescent anxiety and depressive disorders in the text revised, fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) were included (American Psychiatric Association 2000). It is important to note that unlike Roth and Pilling (2008) who included both high- and low-intensity treatments in the development of their model, only high-intensity treatments were included in the development of this model. While there are some low-intensity treatments available for anxiety disorders in children and adolescents (e.g., Rapee et al. 2006a; Spence et al. 2006), these treatments did not meet the aforementioned criteria and were, thus, not included.

Reviewing Treatment Manuals and Extracting and Validating Competency Lists

The authors obtained all of the EST manuals listed in Table 1 by either emailing the first author on the EST manual and requesting a copy or purchasing the EST manual from the publisher. The first author of this paper then reviewed each of the ESTs intensively, with the aim of extracting a full list of therapist competencies necessary for implementing each manual. If any problems arose in this process, the second and third authors were consulted for discussion and clarification.

After compiling a list of competencies for each EST manual, the authors of this paper sent each list to the first author of the corresponding EST, via email. In this email, the EST authors were asked to read the list of competencies that had been extracted from their manual and comment on whether this list adequately represented the full set of competencies that a therapist would need in order to implement this treatment with a child or adolescent suffering from the disorder(s) that the EST targeted. In doing so, the authors of this paper asked EST authors to add any competencies that may have been omitted, delete any competencies that were considered unnecessary, and/or modify competencies that they considered could have been better described.

Seven of the 10 EST authors responded and provided feedback with some modifications. Modifications made by the authors of the ESTs were minor and primarily altered the phrasing of competencies rather than making major additions or deletions to the competencies identified by the authors of this paper. This means that the degree of agreement between the authors of this paper and the EST authors was high. The authors of this paper then made these modifications to the competency lists and sent the modified lists back to the corresponding EST author for their approval and validation.

Model Building

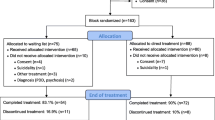

In order to develop the overall model of therapist competencies for the treatment of any of the DSM-IV-TR child or adolescent anxiety or depressive disorders, the authors of this paper: (1) compiled a list of competencies necessary for treating a child or adolescent with any of the 10 ESTs included in the review and tentatively situated these into the Roth and Pilling (2008) five-domain structure, (2) compiled an ERG of seven local experts in research, training, and/or professional practice related to CBT for child and adolescent anxiety and depression, and (3) worked in collaboration with these experts to develop the model. The topics of discussion at the ERG meeting pertained to both the content and the structure of the model, at theoretical and practical levels.

The competency content of the model was largely informed by the content of the EST manuals for child and adolescent anxiety and depressive disorders. However, in some cases, expert opinion also informed those competencies that were included in the model. For example, generally, ESTs do not emphasize the use of case formulation or treatment planning as a part of their competent implementation; however, the ERG agreed that therapists in RCP require these competencies and thus included them in the model.

The ERG discussed the Roth and Pilling (2008) five-domain structure and decided to modify this to include only three domains, which are further described in the results and discussion section of this paper. This decision was made to make the overall model easier to read and to make each specific competency more amenable to being operationalized into training modules. In addition to this, the ERG decided to group related competencies together, so as to conceptually, and visually, organize competencies by similarity in the processes or techniques involved. Finally, the ERG agreed that competencies specific to the treatment of children and adolescents should be highlighted within the model, so as to emphasize the important adaptations that are necessarily made when treating anxious and depressed children and adolescents. This led to the decision to shade competencies specific to child and adolescent treatment gray and to leave competencies shared between child and adolescent, and adult treatments white (See Fig. 1). It should be noted, however, that the distinctions between child- and adolescent-specific competencies and shared competencies are not absolute and are used primarily as indicators of the central child and adolescent adaptations that emerged during the development of the model.

After the ERG meeting, the authors met to compile the overall model of therapist competencies in accordance with discussions at the ERG meeting. In order to ensure that this model reflected decisions made in the ERG meeting, the model was emailed to the ERG asking for their feedback. One minor suggestion pertaining to the structure was made by one of the ERG members, and the authors of this paper made this modification to the model, in line with the consensus achieved at the ERG meeting.

Treatment Author Model Validation

While pooling together the competencies from different treatments into one overall model, the authors ran the risk of omitting important competencies necessary for the implementation of any one of the individual EST manuals. As such, an additional step was undertaken to ensure such an omission was not made. This step involved emailing the final model to each EST manual author who had been included in the competency list validation phase requesting comment on whether the model continued to adequately represent the full set of competencies necessary for implementing their specific EST manual. Four of seven EST authors offered feedback, and the authors of this paper met to discuss these suggestions and modified the model accordingly. Modifications pertained to the need to include psychoeducation regarding the disorder and to emphasize the importance of flexible treatment implementation within a number of the competencies.

International Expert Model Validation

In an attempt to improve the external validity of the model, the model was sent to a number of international experts in the field of research, or training related to the empirically supported, cognitive behavioral treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety or depressive disorders. Experts who were well published in and/or developed and facilitated training for the empirically supported CBT treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety or depressive disorders were contacted via email. Experts were asked to comment on whether: (1) the structure of the model was clear and useful and (2) the content was accurate, or whether they would modify, add, or delete any of the competencies.

Seven international experts offered feedback consisting of minor changes, and the authors met to discuss these suggestions and modified the model accordingly. All experts considered the structure and organization of the model to be clear and useful. Feedback relating to the content included the need to place greater emphasis on having a good understanding of relevant child and adolescent characteristics which can impact upon therapy. The characteristics referred to included factors such as important life transitions, bullying and peer victimization experiences, traumatic events, and learning disorders. It is important to note here that three of the seven international experts were also EST manual authors who had participated in previous stages of the model development.

Results and Discussion

Review of 10 ESTs for child and adolescent anxiety and depressive disorders, along with EST author, and both local and international expert review and input, resulted in the development of a model of therapist competencies for the empirically supported cognitive behavioral treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety disorders and depression. This model is represented in Fig. 1. The following section aims to describe each of these domains in further detail, with reference to the competency categories and individual competencies within each domain. The descriptions provided are not exhaustive, and the interested reader may obtain further information on any of the competencies in the model upon request from the first author. Following this description of the model, important similarities and differences that exist between this model and the treatment of anxious and depressed adults and children/adolescents will be highlighted.

Generic Therapeutic Competencies

Generic Therapeutic Competencies are those competencies needed to relate to people and are common to all psychological interventions (Roth and Pilling 2008). These competencies are therefore not specific to the implementation of CBT. The competency categories within the Generic Therapeutic Competencies and the individual competencies within this domain are described later.

Practicing Professionally

The child or adolescent therapist should possess and utilize up-to-date knowledge of professional, ethical, and legal codes of conduct relevant to working with children and adolescents and their families. While a therapist who works with adults should also work within professional, ethical, and legal codes of conduct, the child and adolescent therapist requires additional knowledge and skills relating to issues such as gaining informed consent from parents for the child or adolescent’s intervention, and the limits to the information that may be shared with parents, due to confidentiality codes.

Given that there is increasing evidence to suggest that supervision is a key component in effective training and practice in EBP (Rakovshik and McManus 2010), a therapist’s willingness and ability to participate in supervision must be emphasized here. However, it is certainly not enough for a therapist to be willing and able to seek supervision; supervision must be available to the clinician. At present, this is not reflected in current training methods for disseminating ESTs (e.g., Herschell et al. 2004) and is an area that is beginning to receive the attention it requires (e.g., Beidas and Kendall 2010; Falender and Shafranske 2010).

An open and positive attitude toward psychotherapy research and the ability to access critically evaluate and make use of this research to inform practice is necessary in clinical practice (Nelson and Steele 2007; Stedman and Schoenfeld, in press). This is an important point of discussion, as there is substantial evidence to indicate that therapists in RCP hold some negative attitudes toward psychotherapy-related research and EBP (e.g., Aarons 2004; Addis and Krasnow 2000; Barry et al. 2008; Borntrager et al. 2009) and that such attitudes partially predict the use of EBP to inform practice (Nelson and Steele 2007). Recent evidence suggests that providing accurate information about research findings increases the likelihood that a clinician will use this information to guide clinical practice (Stewart and Chambless 2007). However, given that organizational climate and culture also play a part in the adoption of EBP, changes at the organizational level are required in order to ensure that EBPs are implemented in RCP (Aarons and Sawitzky 2006; Mendel et al. 2008).

Finally, an important competency for therapists implementing EBP is the ability to self-assess current levels of competence in relevant areas and to seek further professional development based on the results of this assessment. Interestingly, while this is an important task for the therapist, and an expectation of any professional, little research has been performed in an attempt to understand or improve therapist self-assessment of competence (Bellande et al. 2010). Further, the results of the research that has been done in this area indicate that therapists are poor at undertaking such self-assessments of competence (e.g., Davis et al. 2006). In order for improvements in this state of affairs, it has been suggested that self-assessment tools be developed and that training in reflective practice and the use of such tools be required (Bellande et al. 2010; Kaslow et al. 2009). Certainly, this is an area of increasing interest around EBP in psychology and warrants mention in this competencies model.

Understanding Relevant Child and Adolescent Characteristics

When implementing any form of psychotherapy, detailed knowledge about client characteristics that can impact on therapy is important. When working with children and adolescents, the pertinent client characteristics include general patterns of cognitive, social, and emotional development across childhood and adolescence, environmental factors (e.g., family structure and relationships), life events (e.g., bullying, trauma), individual differences (e.g., learning disorders, familial culture), and comorbidity. For more information on these topics, see relevant handbooks that detail theory, research, and practice guidelines related to these topic areas (e.g., Adams and Berzonsky 2003; Besag 2006; Damon and Lerner 2008; Davies 2010; Eshun and Gurung 2009; Field 2007; Fletcher et al. 2007; Goswami 2003; Odom et al. 2007).

Building a Positive Relationship

As is the case with adults, children and adolescents are more likely to engage in therapy if the therapist shows appropriate levels of warmth, concern, confidence, and genuineness and avoids negative interpersonal behaviors such as aloofness or impatience (Chu et al. 2009; Roth and Pilling 2008). However, the engagement of children and adolescents also requires the therapist to engage in additional behaviors that accommodate both the developmental level of the child or adolescent and their typically low levels of intrinsic motivation for therapeutic change (Chu et al. 2009; Miller and Rollnick 2002; Piacentini and Bergman 2001). For children, this might mean playing interactive games, whereas for adolescents, it may mean engaging in conversational topics that interest the adolescent such as their hobbies or their peer group activities (Sauter et al. 2009) and ensuring that the adolescent’s personal goals are integrated with the goals of the therapist or program (Dawes and Larson, in press). Furthermore, the pacing of sessions would need to be adjusted on the basis of developmental level and degree of interest in and motivation for therapy.

The therapeutic alliance is defined as a combination of therapist–client emotional bond, collaboration on techniques, and agreement on goals and is associated with positive treatment outcomes for youth seeking treatment for internalizing disorders (Hawley and Weisz 2005; Shirk et al. 2008). The therapeutic alliance with a young person is enhanced by the therapist promoting collaboration with the child and avoiding behaviors such as attempting to find a common ground between themselves and the child, behaving in an overly formal manner, and pushing the young person to talk (Creed and Kendall 2005). Given that parent–therapist alliance is associated with child session attendance and retention, the youth therapist should also form an alliance with the young person’s parent in an effort to keep the young person in therapy (Hawley and Weisz 2005).

When developing and maintaining alliances with both parent and child, the therapist should be able to avoid over identifying with either party, thereby continuing to make decisions based on ethical, professional responsibilities toward the child or adolescent as their client (Curry and Reinecke 2010). The interested reader is directed to a growing body of literature regarding the therapeutic alliance in the treatment of children and adolescents (e.g., Chiu et al. 2009; Hawley and Weisz 2005; Kazdin et al. 2005; Kendall et al. 2009; Liber et al. 2010; Shelef et al. 2005; Shirk et al. 2008).

Finally, instilling hope and optimism for positive change is important in the treatment of youth. These motivators should be based upon current evidence regarding the efficacy of treatments for the particular difficulty that the child or adolescent is experiencing (March and Mulle 1998).

Conducting a Thorough Assessment

When conducting a thorough assessment of the child or adolescent, the presence of psychological disorders should be determined using an evidence-based assessment approach (e.g., Silverman and Ollendick 2008). This approach requires proficient use of multiple methods including a reliable and valid structured diagnostic interview, self-report, and behavioral observational measures, and multiple informants including the child/adolescent, parent, teacher, and/or allied health professional (e.g., Silverman and Ollendick 2008). Therefore, the child and adolescent therapist assesses both the child or adolescent and other relevant parties (generally including at least one of the parents) and subsequently amalgamates both reports, even when those reports diverge (e.g., Ollendick and Hovey 2010; Silverman and Ollendick 2008). Information from each assessment method and source is then to be analyzed in order to arrive at a clinical diagnosis with consideration of differential diagnoses (For more information on assessment see Essau and Ollendick 2009; Langley et al. 2002; Silverman and Ollendick 2008).

When conducting a thorough assessment, an appraisal of the presence of child- and family-specific characteristics which may impact upon treatment is recommended. These characteristics include the child or adolescent’s current level of functioning, engagement in and nature of peer relationships, developmental history and stage, suitability for intervention, and family functioning. At present, there is no one particular way in which such an assessment should be done; however, in response to this need, reliable and valid assessments of some of these factors which can impact on therapy, such as developmental readiness for CBT (Sauter et al. 2010), and the presence of parenting practices common in families of youth with internalizing disorders (Ehrenreich et al. 2009) are becoming available. This is certainly an exciting area of study that requires more research attention across therapeutic orientations.

Assessment of children should be developmentally sensitive, with therapists drawing upon knowledge that child’s interpretation of language related to worry or emotion can be very different to that of adults and that their ability to accurately report specific details related to cognitions or emotions may be hindered (See Schniering et al. 2000 for a review). Knowledge of these developmental issues related to child emotion–related language interpretation and reports should not only be utilized in the initial assessment process, but also throughout child/adolescent treatment.

Finally, a thorough evaluation of suicide risk should be undertaken with children and adolescents and managed in an ethical manner (Berman et al. 2006; Goldston 2003; Sarkar et al., in press) Since there is emerging evidence that suicidal phenomena in children differs to that of adolescents, the competent therapist should be aware of these differences and incorporate the knowledge of these differences into their suicide assessment and management plan (Sarkar et al., in press).

CBT Competencies

CBT Competencies are those competencies necessary to plan, implement, and flexibly adapt Specific CBT Techniques with the individual child and their parents. The competency categories and the individual competencies within this domain are described later.

Understanding Relevant CBT Theory and Research

A therapist who is competent at implementing CBT with youth should have a solid understanding of the theoretical underpinnings of CBT models (i.e., the interrelationships of cognitions, emotions, behaviors and the environment) and the ability to apply CBT practices in line with these theoretical underpinnings (e.g., Beck et al. 1979; Lewisohn 1974; Roth and Pilling 2008). When working specifically with anxiety and depressive disorders, the CBT therapist should have a good understanding of the specific cognitive, behavioral, and environmental factors that tend to contribute to the development and maintenance of anxiety and depressive disorders and be able to identify the presence and nature of these in the particular client being seen (Roth and Pilling 2008).

Anxious and depressed youth share similar cognitions (e.g., overestimation of the probability and cost of feared events, negative view of self, world, and the future) and behaviors (e.g., avoidance of feared situations, withdrawal from engagement in goal directed behaviors and pleasant activities) with anxious and depressed adults (e.g., Crowe et al. 2006; Kendall et al. 1990; Southam-Gerow and Kendall 2000; Vasey et al. 1996; Weems et al. 2001). A detailed exposition of these cognitions and behaviors will not be entered into due to a lack of space, but the interested reader is directed toward this literature to gain further understanding of the nature of these maintaining factors in children and adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. One noteworthy point, however, is that recent evidence indicates that youth with internalizing symptoms are characterized by a unique cognitive profile, which distinguishes them from their peers with externalizing symptomatology (Schniering and Rapee 2004). In addition, the strength of the relationship between these cognitions and internalizing disorders appears to increase with age across childhood and adolescence, which may alter the way a therapist uses CBT to treat younger children (Perez-Olivas et al. 2008; Watts and Weems 2006).

When working with children and youth, familial factors that tend to maintain child and adolescent anxiety and depressive disorders should also be taken into account. Broadly speaking, in the case of anxiety disorders, such family factors typically involve excessive parental intrusiveness, overprotection, and control (Greco and Morris 2002; Hudson et al. 2008; Hudson and Rapee 2001, 2005), and parental modeling of anxious behaviors (e.g., Capps and Ochs 1995; Whaley et al. 1999). In depression, such familial factors involve excessively high expectations of the child or adolescent, coupled with low levels of praise or positive reinforcement (Cole and Rehm 1986), and a poor parent–child/adolescent relationship characterized by poor family problem-solving, negative parent–adolescent affect, high parent–adolescent conflict, and mutual criticism (Asarnow et al. 1994; Ge et al. 1996; Sheeber et al. 2007).

Emerging research now suggests that parenting behaviors such as those listed above are significant moderators of child disorder onset (McLeod et al. 2007). The way in which parent behaviors moderate the onset of these disorders is currently under debate; however, evidence suggests that parents may offer disorder-related verbal information, vicarious learning, and direct conditioning, which provide pathways for the development of cognitive processes that subsequently lead to the development and maintenance of psychopathology (Muris and Field 2008).

Devising, Implementing, and Revising a CBT Case Formulation and Treatment Plan

Drawing upon the knowledge of those cognitive, behavioral, and environmental factors which tend to maintain anxiety and depression, and information obtained through the assessment process, a CBT case formulation of the causes and maintaining factors of the individual’s problem can be devised (Bieling and Kuyken 2003; Boschen and Oei 2008). Further, a treatment plan that aims to intervene on those maintaining factors can be developed. The treatment plan should include appropriately selected and sequenced Specific CBT Techniques seen in Fig. 1. When developing this treatment plan, the therapist should consider the social, emotional, and cognitive capacity of the young person to make use of Specific CBT Techniques to be included (Barrett and Ollendick 2004). When making such decisions, the chronological age of the young person should only be used as a guide, given that each individual varies with regard to the pace at which he or she meets developmental milestones within each domain of functioning (Holmbeck et al. 2006).

Developmental considerations that the therapist might take into account with regard to social maturation include whether or not the child or adolescent has reached the stage of seeking autonomy from parents (Sauter et al. 2009). This factor may be important in treatment planning, since some research has shown that the inclusion of parents in therapy is more important for positive outcomes among children who have not reached this stage of autonomy seeking than among adolescents who have reached this important stage of social maturation (Barrett et al. 1996). However, the degree of parental involvement in treatment should also be determined based upon family functioning, parent–child relationship, and the parent’s willingness and ability to assist (Curry and Reinecke 2010; Kendall and Beidas 2007).

Since a client’s ability to recognize, differentiate, and regulate emotions is imperative to the successful implementation of CBT (Bailey 2001; Kingery et al. 2006; Suveg et al. 2009), these factors should be considered when planning treatment. For example, younger children may require more time to be spent on learning to recognize and differentiate emotions before they can understand that different thoughts lead to different emotions and that thoughts can be modified. When making treatment planning decisions based upon the child or adolescent’s stage of cognitive development, the individual’s ability to engage in self-reflection and metacognitive processes ought to be considered (Sauter et al. 2009). For example, when treating children who have limited metacognitive awareness, it may be necessary to include more behaviorally orientated Specific CBT Techniques such as In vivo Exposure or Behavioral Activation rather than more cognitively demanding techniques such as cognitive restructuring.

This approach to treatment planning is akin to a modular approach and the common elements movement (e.g., Chorpita et al. 2004, 2005, 2007). This approach asks the therapist to choose Specific CBT Techniques based on the client case formulation rather than implementing a different treatment manual for each disorder in the diagnostic profile. This modular approach is more acceptable to therapists in RCP than the latter and has the potential to increase the uptake of ESTs in RCP (Borntrager et al. 2009; Garland et al. 2008).

As outlined in the model (Fig. 1), the initial sessions of treatment should include psychoeducation regarding the nature of the disorder, an individualized case formulation, and the treatment plan, which is communicated in language that is appropriate for both the parent and child. Subsequently, the treatment goals should be negotiated between the parent, child, and therapist. This can be difficult when parent and child/adolescent goals differ to one another; however, a range of strategies may assist in resolving the discrepancy, including communication and negotiation skills.

As therapy progresses, the child/adolescent CBT therapist should use questionnaire measures and self-monitoring to guide therapy, identify obstacles or areas of risk (e.g., self-harm and suicidality), make decisions about revisions of the case formulation or treatment plan, and assess client outcome (Roth and Pilling 2008). Typical obstacles that may occur in the treatment of childhood internalizing disorders include the denial of anxiety, the presence of realistic fears, non-compliance, resistance, and parent unwillingness to assist, or attempts to use sessions to discuss topics that are irrelevant to the goals of treatment (Curry et al. 2005; Kendall and Hedke 2006; Rapee et al. 2006). When obstacles to treatment are identified, these may be managed by drawing upon relevant theory and research (seen in Fig. 1, Understanding Relevant CBT Theory and Research), and supervision (see Fig. 1, Practicing Professionally).

Collaboratively Conducting CBT Sessions

Working collaboratively with the child/adolescent and family is critical to maintaining client motivation and skill acquisition and implementation (Creed and Kendall 2005). Activities that can maximize this collaboration include jointly setting and adhering to session goals or agenda, sharing the rationale for each Specific Technique with the client, eliciting and responding to client feedback and client’s current mood and life events, and jointly setting, planning, and reviewing personally meaningful homework (Roth and Pilling 2008). With regard to homework in CBT, the interested reader is directed toward theory and research pertaining to the role of homework, and therapist knowledge, skills, and attitudes relevant for the effective use of homework in CBT in general (Detweiler-Bedell and Whisman 2005; Haarhoff and Kazantzis 2007; Kazantzis and Daniel 2008; Kazantzis et al. 2005; Kazantzis et al. 2005) and when implementing CBT with children and adolescents in particular (Gaynor et al. 2006; Houlding et al. 2010; Hudson andand Kendall 2002).

It is also important to implement Specific CBT Techniques flexibly for the client’s idiosyncratic disorder presentation, needs or preferences, cultural background, and current mood. There is a large body of literature on flexibility in CBT which provides a detailed discussion on this topic (e.g., Chu et al. 2009; Grover et al. 2006; Kendall and Beidas 2007; Kendall et al. 1998; 2006). Further, appropriate use of experiential strategies such as role play, modeling, corrective feedback, and reinforcement should also be used when implementing Specific CBT Techniques in session (e.g., Beidel et al. 1998).

Therapists should draw upon the assessment information and the case formulation to deliver Specific CBT Techniques in session with developmental sensitivity, an appropriate level of in-session collaboration between child or adolescent, parent, and therapist and assist parents to take an appropriate role in homework completion between sessions. With regard to implementing sessions with developmental sensitivity, the therapist must be able to adapt the Specific CBT Techniques included in the treatment plan for the young person’s stage of social, emotional, and cognitive development. There is a substantial literature on implementing CBT sessions with developmental sensitivity, which the interested reader may access for further information (Barrett and Ollendick 2004; Bouchard et al. 2004; Cartwright-Hatton and Murray 2008; Choate-Summers et al. 2008; Kingery et al. 2006; McAdam 1986; Nelson and Nelson 2010; Ollendick et al. 2001; Piacentini and Bergman 2001; Sauter et al. 2009).

With reference to parent involvement, the therapist who has planned for parents to be extensively involved in therapy ought to be capable of the practicalities of parent inclusion in the in-session collaborative relationship and between sessions as their child’s coach. The coach is an assistant who helps the child or adolescent to complete tasks, a motivator, who provides reinforcement for involvement in treatment, effort and successes, and a facilitator, who provides opportunity for skill practice outside of therapy (Rapee et al. 2006). Coaches should also be notified about negative behaviors that they may want to engage in (e.g., criticizing the child, permitting avoidance) and ways to overcome these by facilitating the child’s own use of Specific CBT Techniques to cope in difficult situations.

Specific CBT Techniques

Specific CBT Techniques are those cognitive behavioral techniques that have proven efficacy for treating child and adolescent anxiety disorders and depression (Roth and Pilling 2008). As seen in Fig. 1, these techniques are divided into five categories, based on whether they aim to modify thoughts (Managing Negative Thoughts), behaviors (Changing Maladaptive Behaviors), mood and arousal (Managing Maladaptive Mood and Arousal), general skills (General Skills Training), or the family environment (Modifying the Family Environment) and are further described in Tables 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, respectively. It can be argued that a number (if not all) of these techniques could be placed into one or more other categories, as most techniques tend to have more than one aim and impact on multiple maintaining factors. For example, behavioral experiments have been placed into the managing negative thoughts category because its usual stated aim is to provide the individual with a chance to test out their negative thoughts and predictions. But it could as accurately be placed into the Changing Maladaptive Behaviors category, as it generally involves encouraging the child or adolescent to enter avoided situations.

Similarities with and Differences to the Adult Model

The results of this study have provided a comprehensive model of therapist competencies required for the empirically supported cognitive behavioral treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders in youth. The main similarities and differences between the competent treatment of children/adolescents as outlined by this model and the competent treatment of adults as outlined by Roth and Pilling (2008) will be summarized in the following paragraph.

Similarities and Differences in Structure

As mentioned in the method section of this paper, the ERG decided to include only three competency domains, instead of the five which were included in the Roth and Pilling (2008) model. This model shares the Generic Therapeutic Competencies and the Specific CBT Techniques domains with the Roth and Pilling (2008) model. Instead of including both the Basic CBT Competencies and the Metacompetencies from the Roth and Pilling (2008) structure, the ERG, having found that distinctions between these were hard to make, combined these two domains into what was subsequently termed CBT Competencies. Furthermore, given that the Roth and Pilling (2008) Problem-specific competencies domain simply listed the ESTs used for each anxiety and depressive disorder, this domain was excluded by the ERG since it did not provide any additional information regarding competencies. The list of ESTs was considered to be better suited to inclusion within the text of the paper (Seen in Table 1). Note that this difference between the adult and the child/adolescent model was based on ERG opinion in the development of the model, not on differences in the treatment of adults and children/adolescents.

Similarities and Differences in Content

Similarities to the Roth and Pilling (2008) adult model of therapist competencies were seen in basic knowledge, professional practice, and Specific CBT Techniques that are utilized irrespective of client age. Specifically, both models include knowledge competencies that represent a general understanding of mental health problems in the targeted population, cognitions, and behaviors that typically maintain anxiety and depressive disorders, the principles and rationale of CBT, and the ability to explain this rationale to the client. In terms of professional practice, the ability to operate within ethical guidelines, use supervision, engage and develop a therapeutic alliance with the client, develop an individualized case formulation and treatment plan, set treatment goals, structure sessions, make use of homework, monitor therapy, manage obstacles to therapy, and end therapy in a planned manner are represented in both models. Finally, common Specific CBT Techniques included exposure, activity scheduling, cognitive restructuring and relaxation, and applied tension.

The main differences appear to have fallen into four broad categories. These include: (1) the possession of knowledge related to child and adolescent development, familial environment other child-/adolescent-specific factors which can impact on therapy and ethical responsibilities of the therapist, (2) being able to take these considerations into account when developing a case formulation and treatment plan for the child/adolescent, (3) being able to implement those child-/adolescent-Specific CBT Techniques (i.e., those shaded Specific CBT Techniques from the General Skills Training or Modifying the Family Environment categories in Fig. 1), and (4) continuously adapting treatment sessions flexibly for child development and family factors.

Implications of the Model

In summary, this work provides a comprehensive set of operationalized and measureable therapist competencies for working with anxious and depressed children and adolescents and their parents. It has a number of important implications including those related to the development of therapist training, the assessment and quality assurance of therapist competence, and the development of EBP guidelines for treating this population.

For training, the core competencies model provides a framework for curriculum development in the treatment of internalizing spectrum disorders in childhood or adolescence. A training program based on this model would provide therapists with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes relevant for treating any of the internalizing disorders in children and adolescents, In addition, this model provides goals and specific measurable objectives to assess therapist outcomes post-training and is therefore relevant in the process of supervision, feedback, and evaluation. Subsequently, a core competencies approach forms the foundation for a dissemination training curriculum which incorporates innovative clinical training and implementation methods.

While a competency-based framework provides the content for the development of training materials, recent evidence suggests that in order to develop effective therapist training, trainers should not only consider the content of the training material, but also effective training delivery methods (Rakovshik and McManus 2010). This might mean including a combination of several training delivery methods or components, such as didactic instruction, problem-based learning, and supervision (Herschell et al. 2010; Rakovshik and McManus 2010). Certainly, increasing attention should be paid to models of adult learning and continuing education in this endeavor (Rakovshik and McManus 2010). Given that access to training is a significant barrier to the uptake of ESTs in RCP (Nelson and Steele 2007), competence-based training resources need to be made readily available and easy to update. A recent suggestion has been to provide therapist training online (Weingardt 2004), and initial findings from this approach have been promising (Dimeff et al. 2009; Granpeesheh et al. 2010; Sholomskas and Carroll 2006; Sholomskas et al. 2005; Weingardt et al. 2009). It is important to note here, however, that there are a number of other therapist, client, and organizational barriers to EST uptake, and these should also be taken into account when disseminating training (Beidas and Kendall 2010; Schoenwald et al. 2010).

On a broader scale, this model cannot only inform dissemination training, but could also be used as a guide to best practice to improve those clinical psychology training programs offered in educational institutions. In this manner, those in charge of curriculum development in such institutions could evaluate their training modules against a core competency model and incorporate new elements that are not represented in the existing curriculum.

Given that the competencies in this model can be represented as operationalized and measurable constructs, they would be ideal as items for an observational assessment of therapist competence in treating children and adolescents with anxiety disorders and depression, in line with instruments developed for therapists working with adults (e.g., Barber et al. 2003; Blackburn et al. 2001; Young and Beck 1980). Such a measure would be useful for assessing individual therapist competence following training, to ensure they have reached an acceptable benchmark level of competence prior to treating children and adolescents with anxiety disorders and depression (Fouad et al. 2009). Supervisors may also evaluate their supervisee in an ongoing manner on such a scale as a form of quality assurance in RCP. Such a process could potentially ensure that children and adolescents seeking treatment in RCP are receiving competently implemented psychotherapy and have the best chance at recovery. In this way, a competency-based approach facilitates critical steps in creating change and developing competent professionals.

In addition to forming the items of an observational measure, this model could also be developed into a therapist self-assessment scale. Self-assessment has value for therapists as it offers them the chance to engage in reflective practice, compare their level of competence against an expected standard, understand their strengths and weaknesses, and subsequently seek further training in relevant areas of weakness (Bellande et al. 2010). Self-assessment is also more easily and cost efficiently administered and is thus more likely to be used by therapists in RCP than an observational measure like the one described earlier (Kaslow et al. 2007). By knowing the competencies that are required of them and having a reliable and valid way of assessing these, therapists in RCP would be able to govern their own training process and develop self-efficacy related to the achievement of all of those competencies necessary for treating children and adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. As noted earlier, however, therapists tend to be poor at assessing their own competence and tend to rate themselves as more competent than objective observers (e.g., Davis et al. 2006). It is suggested that therapists receive training in how to reliably and validly perform a self-assessment based on this model before making use of such a measure (Kaslow et al. 2007).

In light of the fact that the present model offers a guideline of best practice, it holds significant implications for the development of standard EBP guidelines to be used by regulators, accreditation boards, and policy makers. With the ethical requirement that professional psychologists practice competent EBP (American Psychiatric Association 2002), such guidelines are essential as quantifiable benchmarks of professional practice. It should be noted, however, that this model presents competent practice within an empirically supported CBT approach and does not include other ESTs for this population, which at present includes IPT only. A more comprehensive model would include other EST approaches.

Further, while this model was based upon empirically supported CBT, this therapeutic approach is only effective at treating 60–70% of those who receive it (e.g., Cartwright-Hatton et al. 2004; Harrington et al. 1998). This means that while this model presents the best account of competent EBP with this population, it is far from perfect, and even the competent therapist will have clients that are unresponsive to treatment. As CBT advances and identifies ways of strengthening the depth and breadth of treatment effects for children and adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders, this model, and corresponding EBP guidelines and training programs built upon it, should be updated to reflect current knowledge. Furthermore, without adequate research into the mechanisms of change in ESTs for child and adolescent anxiety and depressive disorders (e.g., Rapee et al. 2009), there is no way to weight competencies in the model based on their relative importance. Once such research is undertaken, the active elements of these treatments should be given greater weight in this model, and the inactive ones eliminated.

While it is true that this model has important implications for informing the work of therapists in RCP, therapists in RCP hold immense value for informing the validation of this model of competencies. For instance, future studies could aim to quantify the presence and degree of these competencies in RCP therapists and relate this to client outcome. Such studies could provide important information regarding which competencies are necessary and/or sufficient for the effective treatment of child and adolescent anxiety and depressive disorders and subsequently inform EBP guidelines and training program curricula.

Finally, by providing a framework of therapist competencies for implementing CBT with children and adolescents with two common psychological disorders, this model has the potential to be expanded to include competencies for treating other common child and adolescent psychological disorders. Such a comprehensive model would have immense value for the development of overarching standard practice guidelines of EBP with children and adolescents for the development of training, assessment, and accreditation of professional psychologists.

In summary, by offering a framework for the development of dissemination and clinical training programs, therapist competence assessment measures, and EBP guidelines, this core competency model provides an innovative approach to bridging the gap between science and practice in the treatment of children and adolescents with anxiety disorders and depression. Certainly, as the field moves toward the development of dimensional models of psychopathology (e.g., Widiger 2005) and the use of transdiagnostic treatments (e.g., Weersing et al. 2008), this model with its integrative approach will continue to provide a conceptual framework for operationalizing clinical competencies needed by therapists treating children and adolescents with internalizing disorders.

References

Aarons, G. A. (2004). Mental health provider attitudes toward adoption of evidence-based practice: the evidence-based practice attitude scale (EBPAS). Mental Health Services Research, 6, 61–74.

Aarons, G. A., & Sawitzky, A. C. (2006). Organizational culture and climate and mental health provider attitudes toward evidence-based practice. Psychological Services, 3, 61–72.

Adams, G. R., & Berzonsky, M. D. (Eds.). (2003). Blackwell handbook of adolescence. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Addis, M. E., & Krasnow, A. D. (2000). A national survey of practicing psychologists’ attitudes toward psychotherapy treatment manuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 331–339.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association. (2002). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychological Association. (2005). Policy statement on evidence-based practice in psychology. Retrieved on July 27, 2010 from www2.apa.org/practice/ebpstatement.pdf.

Angold, A., Costello, J. E., & Erkanli, A. (1999). Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 40, 57–87.

Asarnow, J. R., Tompson, M., Hamilton, E. B., Goldstein, M. J., & Guthrie, D. (1994). Family expressed emotion, childhood-onset depression, and childhood onset schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 22, 129–146.

Bailey, V. (2001). Cognitive-behavioural therapies for children and adolescents. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 7, 224–232.

Barber, J. P., Liese, B. S., & Abrams, M. J. (2003). Development of the cognitive therapy adherence and competence scale. Psychotherapy Research, 13, 205–221.

Barrett, P. M., Dadds, M. R., & Rapee, R. M. (1996). Family treatment of childhood anxiety: A controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 333–342.

Barrett, P. M., Farrell, L. J., Pina, A. A., Peris, T. S., & Piacentini, J. C. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent obsessive–compulsive disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 131–155.

Barrett, P. M., & Ollendick, T. H. (2004). Handbook of interventions that work with children and adolescents: Prevention and treatment. West Sussex: Wiley.

Barry, D. T., Fulgieri, M. D., Lavery, M. E., Chawarski, M. C., Najavits, L. M., Schottenfeld, R. S., et al. (2008). Research- and community-based clinicians’ attitudes on treatment manuals. The American Journal on Addictions, 17, 145–148.

Beck, A. T., Rush, J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press.

Beidas, R. A., & Kendall, P. C. (2010). Training therapists in evidence-based practice: A critical review of studies from a systems-contextual perspective. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17, 1–30.

Beidel, D. C., Turner, S. M., & Morris, T. L. (1998). Social effectiveness therapy for children: A treatment manual. South Carolina: Unpublished Manuscript.

Beidel, D. C., Turner, S. M., & Morris, T. L. (2000). Behavioral treatment of childhood social phobia. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 1072–1080.

Bellande, B. J., Winicur, Z. M., & Cox, K. M. (2010). Urgently needed: A safe place for self-assessment on the path to maintaining competence and improving performance. Academic Medicine, 85, 16–18.

Berman, A. L., Jobes, D. A., & Silverman, M. M. (2006). Adolescent suicide assessment and intervention (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Besag, V. E. (2006). A practical approach to girls’ bullying: Understanding girls’ friendships. fights and feuds. Berkshire, England: McGraw-Hill House.

Bieling, P. J., & Kuyken, W. (2003). Is cognitive case formulation science or science fiction? Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 52–69.

Blackburn, I. M., James, I. A., Milne, D. L., & Richelt, F. K. (2001). The revised cognitive therapy scale (CTSR): Psychometric properties. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 29, 431–447.

Borntrager, C. F., Chorpita, B. F., Higa-McMillan, C., & Weisz, J. R. (2009). Provider attitudes toward evidence-based practices: Are the concerns with the evidence or with the manuals? Psychiatric Services, 60, 677–681.

Boschen, M. J., & Oei, T. P. S. (2008). A cognitive behavioral case formulation framework for treatment planning in anxiety disorders. Depression and Anxiety, 25, 811–823.

Bouchard, S., Mendlowitz, S. L., Coles, M. E., & Franklin, M. (2004). Considerations in the use of exposure with children. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 11, 56–65.

Brent, D. (1995). Risk factors for adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior: Mental and substance abuse disorders, family environmental factors, and life stress. Suicidal and Life Threatening Behavior, 25, 52–63.

Brent, D. A., Holder, D., Kolko, D., Birmaher, B., Baugher, M., Roth, C., et al. (1997). A clinical psychotherapy trial for adolescent depression comparing cognitive, family, and supportive therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54, 877–885.

Brent, D., & Poling, K. (1997). Cognitive therapy treatment manual for depressed and suicidal youth. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, Services for Teens at Risk.

Capps, L., & Ochs, E. (1995). Constructing panic: The discourse of agoraphobia. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Cartwright-Hatton, S., & Murray, J. (2008). Cognitive therapy with children and families: Treating internalizing disorders. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 36, 749–756.

Cartwright-Hatton, S., Roberts, C., Chitsabesan, P., Fothergill, C., & Harrington, R. (2004). Systematic review of the efficacy of cognitive behaviour therapies for childhood and adolescent anxiety disorders. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43, 421–436.

Chambless, D. L., Baker, M. J., Baucom, D. H., Beutler, L. E., Calhoun, K. S., Crits-Cristoph, P., et al. (1998). Update on empirically validated therapies, II. The Clinical Psychologist, 51, 3–16.

Chambless, D. L., & Hollon, S. D. (1998). Defining empirically supported therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 7–18.

Chambless, D. L., Sanderson, W. C., Shoham, V., Johnson, S. B., Pope, K. S., Crits-Cristoph, P., et al. (1996). An update on empirically validated therapies. The Clinical Psychologist, 49, 5–18.

Chiu, A. W., McLeod, B. D., Har, K., & Wood, J. J. (2009). Child–therapist alliance and clinical outcomes in cognitive behavioral therapy for child anxiety disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50, 751–758.

Choate-Summers, M. L., Freeman, J. B., Garcia, A. M., Coyne, L., Frzeworski, A., & Leonard, H. L. (2008). Clinical considerations when tailoring cognitive behavioral treatment for young children with obsessive compulsive disorder. Education and Treatment of Children, 31, 395–416.

Chorpita, B. F., Becker, K., & Daleiden, E. L. (2007). Understanding the common elements of evidence-based practice: Misconceptions and clinical examples. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46, 647–652.

Chorpita, B. F., Daleiden, E. L., & Burns, J. A. (2004). Designs for instruction, designs for change: Distributing knowledge of evidence-based practice. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11, 332–335.

Chorpita, B. F., Daleiden, E. L., & Weisz, J. R. (2005). Identifying and selecting the common elements of evidence based interventions: A distillation and matching model. Mental Health Services Research, 7, 5–20.

Chu, B. C., & Kendall, P. C. (2009). Therapist responsiveness to child engagement: Flexibility within manual-based CBT for anxious youth. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65, 736–754.

Clark, D. M., Layard, R., Smithies, R., Richards, D. A., Suckling, R., & Wright, B. (2009). Improving access to psychological therapy: Initial evaluation of two UK demonstration sites. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47, 910–920.

Clarke, G., Lewinsohn, P. M., & Hops, H. (1990). Leader’s manual for adolescent groups: Coping with depression course. Portland: Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research.

Cohen, J. A., Deblinger, E., Mannarino, A. P., & Steer, R. A. (2004). A multisite randomized controlled study of sexually abused, multiply traumatized children with PTSD: Initial treatment outcome. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43, 393–402.

Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., & Deblinger, E. (2006). Treating trauma and traumatic grief in children and adolescents. NY: The Guilford Press.

Cole, D. A., & Rehm, L. P. (1986). Family interaction patterns and childhood depression. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 14, 297–314.

Creed, T. A., & Kendall, P. C. (2005). Therapist alliance-building behavior within a cognitive-behavioral treatment for anxiety in youth. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 498–505.

Crowe, M., Ward, N., Dunnachie, B., & Roberts, M. (2006). Characteristics of adolescent depression. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 15, 10–18.

Curry, J., & Reinecke, M. (2010). Major Depression. In J. C. Thomas & M. Hersen (Eds.), Handbook of clinical psychology competencies (Vol. 3). New York: Springer.

Curry, J. F., Wells, K. C., Brent, D. A., Clarke, G. N., Rohde, P., Albano, A. M., et al. (2005). Treatment for adolescents with depression study (TADS) cognitive behavior therapy manual: Introduction, rationale, and adolescent sessions. Durham, NC: Duke University Medical Center, The TADS Team.

Damon, W., & Lerner, R. M. (2008). Child and adolescent development: An advanced course. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Davies, D. (2010). Child development: A practitioner’s guide (3rd ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.

Davis, D. A., Mazmanian, P. E., Fordis, M., Harrison, R. V., Thorpe, K. E., & Perrier, L. (2006). Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Association, 296, 1094–1102.

Dawes, N. P., & Larson, R. How youth get engaged: Grounded-theory research on motivational development in organized youth programs. Developmental Psychology (in press).

Deblinger, E., & Heflin, A. E. (1996). Treating sexually abused children and their nonoffending parents. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Detweiler-Bedell, J. B., & Whisman, M. A. (2005). A lesson in assigning homework: Therapist, client, and task characteristics in cognitive therapy for depression. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 36, 219–223.

Dimeff, L. A., Koerner, K., Woodcock, E. A., Beadnell, B., Brownd, M. Z., Skutch, J. M., et al. (2009). Which training method works best? A randomized controlled trial comparing three methods of training clinicians in dialectical behavior therapy skills. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47, 921–930.

Ehrenreich, J. T., Micco, J. A., Fisher, P. H., & Warner, C. M. (2009). Assessment of relevant parenting factors in families of clinically anxious children: The family assessment clinician-rated interview (FACI). Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 40, 331–342.

Epstein, R. M., & Hundert, E. M. (2002). Defining and assessing professional competence. Journal of the American Medical Association, 287, 226–235.

Eshun, S., & Gurung, R. A. R. (Eds.). (2009). Culture and mental health: Sociocultural influences, theory, and practice. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Essau, C. A., & Ollendick, T. H. (2009). Diagnosis and assessment of adolescent depression. In S. Nolen-Hoeksema & L. M. Hilt (Eds.), Handbook of depression in adolescents (pp. 33–52). New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Falender, C. A., & Shafranske, E. P. (2010). Psychotherapy-based supervision models in an emerging competency based-era: A commentary. Psychotherapy Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 47, 45–50.

Ferdon, C. D., & Kaslow, N. J. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 62–104.

Field, E. M. (2007). Bully blocking: Six secrets to help children deal with teasing and bullying. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Fletcher, J. M., Lyon, G. R., Fuchs, L. S., & Barnes, M. A. (2007). Learning disabilities: From identification to intervention. New York: The Guilford Press.

Ford, T., Goodman, R., & Meltzer, H. (2003). The British child and adolescent mental health survey 1999: The prevalence of DSM-IV disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 1203–1211.

Fouad, N. A., Grus, C. L., Hatcher, R. L., Kaslow, N. J., Hutchings, P. S., Madson, M. B., et al. (2009). Competency benchmarks: A model for understanding and measuring competence in professional psychology across training levels. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 3(Suppl.), 5–26.

Garland, A. F., Hawley, K. M., Brookman-Frazee, L., & Hurlburt, M. S. (2008). Identifying common elements of evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children’s disruptive behavior problems. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47, 505–514.

Gaynor, S. T., Lawrence, P. S., & Nelson-Grey, R. O. (2006). Measuring homework compliance in cognitive-behavioral therapy for adolescent depression: Review, preliminary findings, and implications for theory and practice. Behavior Modification, 30, 647–672.

Ge, X., Best, K. M., Conger, R. D., & Simons, R. L. (1996). Parenting behaviors and the occurrence and cooccurrence of adolescent depressive symptoms and conduct problems. Developmental Psychology, 32, 717–731.

Goisman, R. M., Warsaw, M. G., & Keller, M. B. (1999). Psychosocial treatment prescriptions for generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder and social phobia, 1991–1996. American Journal of Psychiatry, 156, 1819–1821.

Goldston, D. B. (2003). Measuring suicidal behavior and risk in children and adolescents. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Goswami, U. (Ed.). (2003). Blackwell handbook of childhood cognitive development. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Granpeesheh, D., Tarbox, J., Dixon, D. R., Peters, C. A., Thompson, K., & Kenzer, A. (2010). Evaluation of an eLearning tool for training behavioral therapists in academic knowledge of applied behavior analysis. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 4, 11–17.

Greco, L. A., & Morris, T. L. (2002). Paternal child-rearing style and child social anxiety: Investigation of child perceptions and actual father behavior. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 24, 259–267.

Grover, R. L., Hughes, A. A., Bergman, R. L., & Kingery, J. N. (2006). Treatment modifications based on childhood anxiety diagnosis: Demonstrating the flexibility in manualized treatment. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 20, 275–286.

Haarhoff, B., & Kazantzis, N. (2007). How to supervise the use of homework in cognitive behavior therapy: The role of trainee therapist beliefs. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 14, 325–332.

Harrington, R., Whittaker, J., Shoebridge, P., & Campbell, F. (1998). Systematic review of efficacy of cognitive behaviour therapies in childhood and adolescent depressive disorder. British Medical Journal, 316, 1559–1563.

Hawley, K. M., & Weisz, J. R. (2005). Youth versus parent working alliance in usual clinical care: Distinctive associations with retention, satisfaction, and treatment outcome. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 117–128.

Herschell, A. D., Kolko, D. J., Baumann, B. L., & Davis, A. C. (2010). The role of therapist training in the implementation of psychosocial treatments: A review and critique with recommendations. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(4), 448–466.