Abstract

Previous research has found that family socialization influences financial giving behaviors and that financial giving predicts personal wellbeing. However, little research since the early 1980 s has explored this phenomenon, and virtually none of the research has been qualitative in nature. As part of the Whats and Hows of Family Financial Socialization project, this study employs a diverse, multi-site, multigenerational sample (N = 115) to qualitatively explore the following research question: how do children learn about financial giving from their parents? In other words, how is financial giving transmitted across generations? From interviews of emerging adults and their parents and grandparents, three core themes emerged: “Charitable Donations,” “Acts of Kindness,” and “Investments in Family.” Various topics, processes, methods, and meanings involved in this socialization are presented, along with implications and potential directions for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Financial giving (also referred to as philanthropy, sharing, generosity, donating, etc.) is a societal asset that benefits both givers and receivers. Indeed, those who routinely give tend to experience greater mental and physical wellbeing (Smith and Davidson 2014). Additionally, giving is an important but understudied facet of financial socialization. Approximately 74% of American adolescents donate to charities (Kim et al. 2011), indicating that giving may be one of the primary ways in which adolescents interact with and learn about money. Research suggests that giving occurs in a social context and is influenced by third parties such as parents (Kim et al. 2011; Lowrey et al. 2004). This is consistent with other financial socialization research which has found that parents tend to be children’s primary socialization agents (Shim et al. 2010).

Despite the importance of financial giving and the centrality of parents to the socialization of giving, we know very little about this intergenerational process. Only a handful of studies since the early 1980 s have explored the development of giving, and virtually none of the research has been qualitative in nature. In order to help parents optimize this key aspect of financial socialization, we must first understand the processes by which this socialization occurs. Using a diverse, multi-site, multigenerational sample, this qualitative study explores how children learn about financial giving from their parents.

Literature Review

Family Financial Socialization

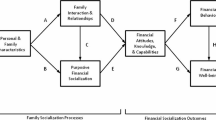

This study’s primary theoretical foundation is Gudmunson and Danes’ (2011) family financial socialization theory. The theory states that financial wellbeing is influenced by financial attitudes, knowledge, capabilities, and subsequent behaviors. These financial outcomes are acquired and developed in a social context. This theory focuses specifically on the family as the socialization agent, although other agents such as peers, school, and work also influence financial socialization outcomes as well, although typically to a lesser extent (Shim et al. 2010).

Gudmunson and Danes (2011) stated that there are six key elements of family financial socialization: (1) personal and family characteristics; (2) family interaction and relationships; (3) purposive financial socialization; (4) financial attitudes, knowledge, and capabilities; (5) financial behavior; and (6) financial well-being. Further, the theory posits that personal and family characteristics (e.g., demographics) influence family interaction and relationships, and that characteristics and family interactions both influence purposive financial socialization. Gudmunson and Danes (2011) distinguished between implicit socialization (i.e., family interaction) and explicit or purposive socialization. In the literature, two main methods identified by which children learn about money in families are parental financial modeling (implicit socialization; Rosa et al. 2018) and parental financial discussion (explicit/purposive socialization) (see Serido and Deenanath 2016 for review), though recent research suggests that other methods such as experiential learning may also play a significant role in the socialization process (LeBaron et al. 2019). These methods and processes, both implicit and explicit, predict financial socialization outcomes. Thus, perhaps the main thesis of the theory is that what children learn (and do not learn) about money from their parents predicts their financial outcomes in childhood (Webley and Nyhus 2006) and later in life (Jorgensen and Savla 2010).

The Socialization of Giving

Gudmunson and Danes (2011) mentioned giving as a facet of family financial socialization multiple times during their presentation of the theory. For example, in discussing parental transmission of financial values, Gudmunson and Danes (2011) stated that

parents [may] have … multifaceted values that they wish to teach their children. For example, while a parent may [wish] to instruct a child about how to get the “most for the money,” they may also [desire] their children to learn to share and to be generous to others (p. 647).

However, little family financial socialization research has explicitly focused on the socialization of financial giving. The small pool of research on this topic will be discussed next.

Some research suggests that children’s financial giving may be, in part, a learned behavior influenced by the giving behaviors of their parents and others. A wealth of research was conducted in the 1970 s and early 1980 s on the development of “generosity.” Many of these early studies utilized experimental designs and had similar results: parental modeling of giving predicted giving by children (e.g., Gagné and Middlebrooks 1977; Rushton 1975; White and Burnam 1975). More recently, McAuliffe et al. (2017) conducted an experimental study with four- to nine-year-old children and found that children gave more when they were told that others gave generously. Recent research has also examined the influence of parental modeling of giving on adolescents. Ottoni-Wilhelm et al. (2014) studied a large, nationally-representative sample of 12–18 year-olds and found that adolescents whose parents gave time (volunteering) and money (financial giving) were more likely to give themselves.

Compared to the literature on parental modeling of giving, little research has examined parental discussion about giving. There are two notable exceptions. First, in Ottoni-Wilhelm et al.’ previously mentioned study (2014), they found that in addition to parental modeling, parental discussion about giving was also influential. Specifically, adolescents whose parents talked with them about giving were more likely to give. Second, Kim et al. (2011), based on a large, national sample of adolescents and their parents, found that parent–child communication about financial giving positively predicted adolescents’ financial giving. In fact, the odds of giving increased nearly two-fold when giving was discussed in families.

Finally, other socialization methods besides modeling and discussion may influence the socialization of giving. For example, Kim et al.’ study (2011) suggested that experiential learning (i.e., learning through hands-on practice or experience; LeBaron et al. 2019) may be a method for instilling giving behaviors in adolescents. They found that adolescents who received an allowance from their parents were 1.4 times more likely to give than adolescents who did not receive an allowance. Gudmunson and Danes (2011) stated that among other reasons, “[M]any allowance-granting families give money to children with the purpose of … teaching children to … share” (p. 648).

Connections to Current Study

The current study draws upon several concepts and propositions from family financial socialization theory (Gudmunson and Danes 2011) in shaping the research question. First, the current study operates under the assumption that parents are the primary financial socialization agents. Second, what children do and do not learn about finances from their parents will influence their future financial wellbeing. Third, it was assumed that personal and family demographics, family relationships, family interactions, and purposive socialization would all influence the socialization of financial giving. The current study seeks to explore in depth how financial giving is transmitted across generations and the processes and methods involved in this niche of financial socialization. Thus, the current study utilizes all six key elements of the theory: personal and family characteristics (e.g., religiosity); family interaction and relationships (e.g., parental modeling of financial giving); purposive financial socialization (e.g., parent–child discussion of financial giving); financial attitudes, knowledge, and capabilities (e.g., attitudes toward financial giving); financial behavior (e.g., child financial giving); and financial well-being (e.g., reported benefits of financial giving).

Financial Giving

Predictors

Several factors have been identified as predictors of financial giving. For example, Su et al. (2011) compared rational and emotional motivations for financial giving and found that religiosity predicted giving much more than financial information did. Additionally, they found that the effects of religion on both the decision to give financially and the amount given were moderated by religious affiliation, with religion having the biggest effect for Christians. Other predictors of financial giving include peer support (Prendergast and Maggie 2013; Wu et al. 2004), being married (Einolf and Philbrick 2014), and similarity and connection between giver and receiver (Prendergast and Maggie 2013). Although financial ability has been found to predict financial giving (Prendergast and Maggie 2013), research has not yet established if and how SES might be associated with financial giving.

Some research has examined cognitive or neurological motives as predictors of financial giving. Two hypotheses about motivation for giving, often viewed as divergent, are “pure altruism” and “warm glow.” Pure altruism is being “satisfied by increases in the public good no matter the source or intent,” while warm glow is being satisfied by one’s “own voluntary donations” (Harbaugh et al. 2007, p. 1622). Proponents of psychological egoism have stated that every human decision is selfish, even the decision to give, because the “warm glow” or “fuzzy feeling” results from and is the motivation behind good deeds (see Sober and Wilson 2000 for discussion). However, Paulus and Moore (2017) proposed that “enjoying benefitting others might not be a form of ‘impure altruism,’ but may be … rather the finest form of altruistic behavior (p. 8).” Others have argued that pure selflessness is possible and that altruistic human actions sometimes come at great personal cost (e.g., Fagin-Jones 2017). Pure altruism would suggest that humans often feel internal rewards when others are benefitted, regardless of whether they themselves provided this benefit (Harbaugh et al. 2007). Support has been found for both hypotheses (e.g., Chan 2010). In their research on neural activity in the reward processing centers of the brain, Harbaugh et al. (2007) found that mandatory giving elicited neural rewards, which supports the idea of pure altruism. They also found that these neural responses were greater when giving was voluntary, supporting the idea of a warm glow.

Outcomes

Whatever the motivation, many humans seem to feel an intrinsic need to give. Financial giving has been linked with numerous positive outcomes (cf. Cowley et al. 2004). In a hallmark study of generosity, The Paradox of Generosity, Smith and Davidson (2014) drew upon data collected in a mixed-method, five-year Science of Generosity Initiative. Data included 2000 surveys and 60 interviews of Americans in 12 states. They found that generous people—including those who gave of their time (volunteering), money (financial giving), and very selves (organ donation)—were happier, healthier (both physically and mentally), and felt a greater sense of purpose. However, these effects were only found for those who were routinely generous, as opposed to “one-and-done” acts of generosity.

Research Question

In summary, research suggests that family socialization (such as parental modeling and discussion) contributes to the intergenerational transmission of financial giving behaviors. Additionally, some research has found positive associations between financial giving and personal wellbeing. However, little research since the early 1980 s has explored this phenomenon. Further, virtually none of the research has been qualitative in nature. There is a need for a qualitative exploration of the socialization of financial giving. Especially since so little research has been done on this subject, a qualitative exploration can provide findings and spark questions that can guide future quantitative studies. Additionally, qualitative studies can often give greater depth and detail about some aspects of a phenomenon than quantitative studies (Daly 2007). This study seeks to address this gap in the literature.

Specifically, this study employs a diverse, multi-site, multigenerational sample to qualitatively explore the following research question: How do children learn about financial giving from their parents? In other words, how is financial giving transmitted across generations?

In exploring this question, retrospective perceptions will be utilized. Although retrospective data are subject to limitations (Gilbert 2006), this approach may be seen as a strength in that those socialization moments and processes remembered (both positive and negative) are likely those that were most influential in shaping financial attitudes and behaviors. Additionally, the parent and grandparent participants in the study’s sample offer important and unique contributions in that they have experienced financial socialization from the perspective of both child and parent. The sample and other aspects of the study’s methodology will be presented next.

Method

This study is part of a larger project: Whats and Hows of Family Financial Socialization (LeBaron et al. 2018). This multigenerational, qualitative project explores what and how children learn about money from their parents. Beneath that umbrella, this specific study addresses how children learn about financial giving from their parents.

Sample

Our sample included participants from three generations: college student, parent, and grandparent. The convenience sample for this study (N = 115) was composed of 90 undergraduate students (ages 18–30) from three universities (a private university in the Intermountain West, a public university in the Midwest, and a state university in the Southwest). All student participants were enrolled in family finance classes. Additionally, our sample included 17 parents and eight grandparents of students. In the student interviews, all students were asked whether or not their parents and/or grandparents might be willing to be interviewed. For those willing, contact information was recorded and invitations were sent via email and phone (see Marks et al. 2019 for more information on sampling and method). Our multigenerational approach was inspired by Handel’s (1996) observation that “No [single] member of any family is a sufficient source of information for that family” (p. 346). In terms of gender, 66% (76 of 115) of participants were female and 34% (39 of 115) were male. In terms of race, 62% (71 of 115) of participants were White and 38% (44 of 115) were ethnic and/or racial minority (including Black, Latino/a, Asian, and Pacific Islander).

Procedure

Trained team members conducted semi-structured interviews either face-to-face or over-the-phone. Student interviews ran approximately 15–30 min, while parent and grandparent interviews typically ran approximately 30–60 min. All interviews began with variations of two open-ended questions: (1) “What did your parents teach you about money?” and (2) “How did they teach you those things?” Two additional questions were also central to parent and grandparent interviews: (3) “What did you teach your children about money?” and (4) “How did you teach them those things?” Follow-up questions were used to elicit further information based on participant responses. As described in Marks et al. (2019), “The semi-structured nature of our interviews was challenging because no two interviews were identical, but this was also a strength in that the interviewer could adapt to the interview participant by asking clarifying follow-up questions that were individually tailored” (p. 8). Although exploratory, the interviews were influenced by family financial socialization theory (Gudmunson and Danes 2011), so follow-up questions often sought to identify whether socialization methods used were implicit or purposive, etc. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Coding and Analysis

The transcriptions were coded and analyzed using a team-based methodology (see Marks 2015), as described below. This methodology was designed for qualitative data collection, coding, and analysis in order to produce “more valid, reliable, and rigorous qualitative research” than solo approaches tend to offer (Marks 2015, p. 494). Strategies for greater reliability included 1) keeping a detailed audit trail for sampling and coding that provided a “replicable method of inquiry” (Marks 2015, p. 499), 2) building a diverse research team, 3) coding in pairs, and 4) tracking inter-rater reliability. The second and third strategies mentioned “temper[ed] the idiosyncrasies [and biases] of any single member” (p. 502).

To identify consensus themes, team members independently read through the transcriptions of 5–10 initial interviews and then presented themes to the rest of the team that were most apparent to them. Upon deliberation, the collective team identified eight core themes. Only emergent themes documented by all team members were “designated with the carefully reserved appellation of core theme” (Marks 2015, p. 503, emphasis in original). After further analyses and deliberation, the team moved from an eight theme model to a seven theme model.

From there, 10 research team members split into five coding pairs. The data were further analyzed and cataloged using NVivo 11 software. First, an interview was assigned to a coding pair. Next, each member of the coding pair independently open coded the interview. Then, coding partners met to review their open codes line-by-line in a check and balance system, resolving discrepancies as they arose. Composite inter-rater reliability for the themes and subthemes presented in this paper was very high (.90), with discrepancies as incidents in which coding partners had varying independent coding and could not agree on a resolution.

Of the 115 participants, 95 (82.6%) mentioned financial giving (also referred to as “sharing”) as a financial topic they taught their children and/or were taught by their parents (LeBaron et al. 2018). Under the core theme of “Sharing,” three subthemes emerged. They will be presented in the following section.

Findings

Some participants reported that they were not adequately taught (or did not adequately teach) about finances. For example, a White mother (interview #106) said, “I don’t remember my parents ever really specifically teaching anything [about money].” Similarly, a White, female emerging adult (#22) exclaimed,

… in this [family finance] class, I’m like, “What the heck! Why didn’t I even know about this?” … I know this is stupid, but some of it I had no idea [about]. I was like, “I’ve never heard about this!”

However, the vast majority of participants seemed to have received quality financial socialization—including socialization regarding giving—from their parents. According to participant reports, three central ways financial giving was taught and learned included (a) charitable donations, (b) acts of kindness, and (c) investments in family. A numeric content analysis (see Marks 2015) of these themes can be found in Table 1.

Theme 1—Charitable Donations: “We’ll Give What We Can Give”

Many participants reportedly learned to give by way of charitable donations. For many religious participants, these donations were given to their respective churches. One White grandfather (#116) remembered, “They passed the plate around and you put the money in. We didn’t have a lot of money, but we put in some. Our parents taught us to be generous [even though] my dad [was] only making nine dollars a week.” A Black mother (#146) explained her beliefs regarding the importance of teaching children to give charitable donations: “The way I was raised, you work a job, God’s the one that allows you to work that job, who gives you the energy and the strength, [and] it’s your responsibility to pay your tithes and your offerings.”

Many religious participants believed that if they made faith-based contributions, their financial situation would work out, not just despite their financial sacrifice but because of it. One White mother (#107) put it this way: “If you pay your tithing first, then you’ll always have enough money.” Similarly, one Latino emerging adult (#76) said, “[My parents told me that] ‘If you trust and you pay your tithing and you work hard, then it will all work out.’ … So I was never fearful. … The Lord takes care of you. He really does.” Often, participants would describe personal experiences in which they reportedly experienced this phenomenon firsthand. A Pacific Islander, female emerging adult (#57) shared the following story from her childhood:

We reached a point in our life when we had nothing to live off but because [my parents always paid tithing] we received blessings. … A family member [showed up with] a car full of groceries. That was just a testimony to me that the Lord does provide for those who give Him what is His, first and foremost. Personal experiences [like that are why I] continu[e] to pay my tithing now.

This consistency in donating, even when finances were tight, seemed critical to several participants. The word “always” was used often. A White grandmother (#114) said, “[We] always, always taught [our kids] to pay their tithing.” A White, male emerging adult (#5) made a remarkably similar statement, this time from the child’s point of view: “They always taught us to always pay our tithing.”

For several participants, religious donations seemed to be the primary topic of their financial learning or teaching. A White mother (#105) said, “The first thing we taught [our kids] about money [was] tithing. That was first.” Another White mother (#113) stated, “I think that [tithing] is the most important financial principle that they could learn—to be generous … and giv[e] to others.” When asked what and how she taught her children about money, a White mother (#107) admitted, “I didn’t do a very good job—most of them just kind of picked it up on their own. But, we’ve always talked about tithing.” Again, the non-negotiable word “always” was employed by a participant.

Although much of the charitable donating mentioned by participants was religious in nature, many participants spoke of other types of donations. For example, a White, male emerging adult (#130) said, “I’m involved in Special Olympics, so [my parents] will give to that and I’ll give to that. … Cancer runs in our family, so they give to [those organizations].” A White grandmother (#114) said, “[Our kids were] always involved in … collections [for] food drives. … They would go from door to door.”

According to the interviews, children were taught to make charitable donations through a variety of methods including modeling, discussion, and experiential learning. One White, female emerging adult (#30) recalled her father’s modeling of consistent payment of religious donations: “My dad would pay his tithing no matter what.” A White mother (#104) described her efforts to set a similar example: “[My husband and I] always paid our tithing … So they knew that we did that, and we always encouraged them to do the same.” A White grandmother (#114) described the impression her father’s charitable efforts left on her:

My dad was on the town board and on the fair board … [and] on the hospital board. There was a room down at the new hospital carrying his name for the donations he made. So the example was always there, [to] always [give], whatever the need was. That’s what we did.

One White, female emerging adult (#121) shared how her parents’ modeling of charitable giving reportedly rubbed off on her:

You know when you’re at a grocery store checking out and they’ll be like, “Do you want to donate to St. Jude’s Children’s Hospital or The Cancer Society?” … My parents … always donate. So [I] hav[e] them as role models. I [recently] went to the dollar store … and they’re like, “Do you want to donate?” and I donated. So I guess [I’m] following in their footsteps.

Sometimes charitable donation was taught through parent–child discussion. One White, female emerging adult (#30) remembered a sit-down family discussion: “There was a Family Home Evening lesson [see LeBaron 2005] where my dad had 10 dimes [and] said, ‘This is a dollar,’ took one, and said, ‘That’s your tithing. One-tenth.’ He taught us how to move the decimal.” Other participants such as this White grandmother (#112) reported more informal, in-the-moment discussions: “When [our kids earned] money we would say, ‘Remember, you need to pay your tithing, you need to take that out.’ So they would do that. It was more of a reminder than anything else. We never forced them, [but] they always did it.”

Participants also reportedly learned to donate to charity through firsthand experience. For this White, female emerging adult (#23), setting aside money for faith-based contributions was her first financial memory. She described,

My parents got [my siblings and me] jars, … and then they explained the whole concept of tithing—how we could set aside 10% in our … jar. So, [I] got to put [my] name on the jar and decorate it. And then [I] set aside money.

Several participants said that giving children the opportunity to donate their own money was important for developing the practice as a habit. One White, female emerging adult (#4) stated, “[Paying] tithing [as a child is] important because that gets that in your mind when you’re little so when you’re older it’s not even a question.” A White, male emerging adult (#60) explained, “[My parents] gave [my siblings and me an] allowance from when we were five or six, so that we could learn early about paying tithing….” Participants often described experiential learning that was guided, especially when children were young. One White mother (#104) said, “It’s probably good for [kids] to have money so that they learn how to handle it and how to deal with it. Whatever money [my kids had], I would help them set aside for tithing.” As children learned to “handle” and “deal with” money, “helping them” seemed to be a key component of the early experiential learning process for some parents.

For many participants on both the teaching (parent) and the learning (child) side of financial socialization, a combination of teaching methods seemed to be effective. This conversation with two White, married grandparents (#115) illustrated this combination approach:

Interviewer: How did [your parents] teach you [about tithing]?

Grandfather: They paid

Grandmother: Mostly by example. They would be [open] about tithing [even when we were] at a young age. We always paid tithing on our little nickels and dimes we got

…

Grandfather: They would often ask, ‘Did you pay your tithing?’ That’s how they teach, by doing and asking and living it

Interviewer: Would you say you taught your children in the same way or is there anything you did differently with that?

Grandmother: Well … they [knew] that we paid tithing … We also taught them about the blessings of tithing.…

Grandfather: We got the little banks that have spending, saving, and tithing divisions in them. When they got their allowance that is where they put it.

This couple learned as children to make religious contributions through modeling, discussion, and experiential learning. They then taught their children to donate using those three methods.

This intergenerational nature of the socialization of financial giving was evident in the interview of a married, White, female emerging adult (#132). She said, “My husband and I try to tithe 10% of our weekly earnings to [our] church. We also fund a child in Indonesia, and we donate a lot of our income to charity. We try to give when we can …” When asked if her parents had given of their money, she responded, “Oh yeah. All the time. Whenever anyone needed anything—food, clothing, anything—they were always there to give [to] them.” However, not all financial giving habits reported were transmitted across generations. Some participants seemed to be transitional characters in that they taught their children to give even though they were not taught that themselves. After first explaining that her parents did not give charitable donations, a Latina grandmother (#156) said,

[I] started teaching [my daughter] the value of sharing. … There are a lot of people in the world that really need things, and we have it all, thank God, and we need to learn how to share. So when she came along, … that’s when I started to get involved [in] sharing …

This focus on others seemed central to many participants’ experiences with (and attitudes towards) charitable donations. One White father (#110) shared,

[It] wasn’t always easy [to give] but … now our attention has turned outward … being as generous as we can be. … That’s just who we are. We’ll give what we can give. And the kids have really responded to that.

One Black, female emerging adult (#120) explained how although she learned to donate via religious contributions, the principle behind charitable donations—the importance of helping others—remained even after her faith waned:

I think [my parents] were trying to teach [me that] it’s not all about us. Money is great … but … we have that money to give. … It is our responsibility to give to the church, give to [God]. … Even if I don’t believe that or am not so much into going to church now, I still believe in giving [and that] it all comes back around. You should give as much as you possibly can, [whether to] a homeless person or an organization or whatever.

Like this emerging adult, for many of the participants in this study, giving charitable donations was an important practice not only to them personally but also to pass on to future generations.

Theme 2—Acts of Kindness: “We Tried to Surprise Somebody Each Christmas”

Though not as commonly referenced (Table 1), several participants spoke of experiences with giving more informally—acts of kindness to neighbors or even strangers. Some parents, such as this White father (#110), reportedly taught this principle using discussion: “I remind the kids all the time, ‘If you see somebody at school who looks hungry at lunch, offer to buy them lunch [or] offer them part of your lunch.’”

Other times acts of kindness seemed to be taught through modeling. One Latina emerging adult (#126) said of her mom: “Any way she could help, she would. … She would tell us that ‘So-and-so needs money, and that’s okay because I have a little bit saved up, so I am going to help them.’” Similarly, a Black, female emerging adult (#140) shared, “I have seen [my mom] give money to someone in need, although she may not have really wanted to or wasn’t in the best financial situation, she still moved her money around and was able to give it.” Reportedly, sometimes this modeling was done very quietly and was barely perceptible by the children. One White, female emerging adult (#22) remembered, “[My dad] was always very willing to help people out … [sometimes] without any of us ever knowing. He was very generous, that was something that was very important.” For some parents, however, it was knowing that their children were watching their example that reportedly made them act generously. A White father (#110) recalled,

Our [local religious leader] came [to my wife and me and] said, “We need folks to help this person financially to serve their mission.” And we were not in the best position financially to say “Okay.” But [because] our kids [were] sitting there looking at us we said, “What do you need of us?” He said the amount, and I looked at [my wife] and thought, “Whoa. How will we do that?” But we said, “Okay, we’re going to do it. We’ll figure it out.”

For some participants, their parents’ example of acts of kindness seemed to influence their own generous behavior. A Latina emerging adult (#133) said,

When I was younger I would always feel so bad for people that were on street corners. So I would take a little cash [or] food … and [my parents] would stop the car so I could give some to them. And both of my parents are the same way. They’re very generous.

This emerging adult’s experiential learning was reflected by other participants’ accounts as well. A White mother (#105) explained, “There are a lot of beggars on buses, on trains, on street corners … When [our kids] felt they wanted to give somebody money in those situations I would give them some money to give them…”

Indeed, several parents reported purposefully involving their children in acts of kindness to facilitate experiential learning. A Latina mother (#102) told of multiple times throughout the years when she and her husband used this method:

Every Christmas we did 12 days of Christmas for someone. … We [went] out and [bought] the things all together, and deliver[ed] all together. … Two kids went to the [neighbors’] door to [drop off and] run, and we’d have the [car] door open, “Hurry!” and then we’d drive off. They probably remember every single one of those that were done over many years. We had friends who lost a job … and need[ed] help buying their basics [like] food. … We had a [neighbor] who had a baby and really did not have money. … We bought all the diapers, baby wipes, and formula for the entire year. And the kids came with us, the kids were part of it. … It would’ve been a lot easier for [my husband and me] to go out, buy, and deliver. But we always thought, “This is a teaching moment. And the kids need to know that you always have to look out for the needs of others.” So yes, they were always part of it. Always.

One White mother (#104) reportedly involved her child in acts of kindness in order to facilitate gratitude in them:

We tried to surprise somebody each Christmas by … [delivering] food and Christmas stuff to somebody. I wanted my child to go with me and see [that] not everybody lives in a really nice house, not everybody lives in a really nice neighborhood, not everybody has all of the advantages that I have, and, Wow! I should be grateful.

Child reports of firsthand giving suggested that these lessons were often internalized. One White, male emerging adult (#60) said,

We used to make Christmas boxes and give them to [neighbors] who were struggling … [That taught me that] if you have enough money for what you need, then you should help people. And even if you may not feel like you have enough, you should always be willing to serve others, even if it’s not in a financial way.

Another White, male emerging adult (#61) described lessons he learned from similar experiences:

We always did … the 12 days of Christmas [for] a family in the [neighborhood] … We’d always try to choose a family with little kids so that they get excited that every night there’s going to be another package on the door. And we’d try to be super sneaky about it. … [I learned to] enjoy serving people, [and I loved] getting to see the smiles on the kids’ faces. … Sometimes little stuff matters more than big things.

Several participants stated that they participated in acts of kindness because they had been the recipient of acts of kindness themselves. For example, one White mother (#104) shared, “We did [acts of kindness] because we were on the receiving end of other people’s generosity [when] we were in graduate school and [struggling] to survive.” When reflecting on why his parents helped others, a White grandfather (#116) remembered a time when his family was helped:

[One day] there was just smoke where our house used to be; our whole house burned down. [And] we didn’t have any insurance. So we were poorer than we were already, and we were poor to start with. All we had was the clothes on our back … The church people around there helped us out with a lot … and one fellow let us live in his house…

A White, male emerging adult (#74) seemed to suggest that with acts of kindness, what goes around comes around:

[My parents] were very generous … Now that they’ve fallen on harder times, it’s cool to see that coming back the other way around, to see people trying to take care of them too. It teaches me that you should be generous when possible and try to get back on your feet so you can do that for other people.

A White father (#110) put it this way: “Do things that help others first and you will always find that you have enough for what you need.”

The next theme specifically addresses financial giving within the family. However, for some participants the line between acts of kindness and investments in family seemed a little blurred. For example, one Pacific Islander, male emerging adult (#54) explained, “My mom was so willing to help out [anyone]. … Our culture [Fijian] is structured in such a way, it’s sort of like [the] family boundary just extends to everyone.” Intrafamilial giving is discussed next.

Theme 3—Investments in Family: “They Use Their Money for the Happiness of Their Kids”

The aspect of financial giving most frequently mentioned by participants was giving within the family (Table 1). Indeed, for this White, female emerging adult (#145), giving “within your close circles” was reportedly the primary way in which she was socialized to give:

My family is really good about if someone needs to borrow money, we don’t think about it, we’ll let them borrow it. … As far as like donations or … charities, not so much, but definitely within your close circles like friends and families, if they need help and need to borrow money, then you do that. … [My mom never had] to think about it, [and she] would [never] complain about it, she just did it. I think over time growing up around that, that’s something I picked up as a value as well.

Unique to the other financial giving themes, the vast majority of participants seemed to describe modeling as the method by which investment in family was taught.

One way that parents seemed to model this principle was through a lived emphasis on the value of shared family experiences, as opposed to the value of money or possessions. For example, a Latina emerging adult (#87) shared,

Although [my parents] are still frugal with their money … my dad always says, “Money is not meant to be sitting in the bank.” … Especially when it comes to experiences like trips, they value experiences more than the value of the actual money. For Christmas we never got presents, but we went [on family trips].

Similarly, another Latina emerging adult (#83) said, “We would go on family trips, and [my parents] always made sure that every summer we’d go somewhere … They never skimped out on family experiences.” A White, male emerging adult (#60) also remembered his parents’ emphasis on and monetary investment in family experiences: “We spent time with each other, whether it cost a lot of money to go somewhere or not.” A White grandmother (#111) fondly recalled her and her husband’s emphasis on family travel:

We traveled as a family quite a bit. We had a trailer … [and] spontaneous[ly] [we’d] say, “Come on let’s go” … and all the kids would hop in … [One time my husband] said he wanted to go to Mexico for Christmas and we didn’t want to. … Christmas morning he said, “I’m going to Mexico tomorrow. If anyone wants to go with me, put your stuff in the trailer and be ready to go by 6am!” And we went and had such a good time.

The importance many participants had reportedly learned to place on family experiences was summed up by this Latina grandmother (#155): “Money was never the goal. That happiness [that comes from] family time, that was the goal. It wasn’t material things.”

In addition to family experiences, many participants may have also been taught to invest in family through monetary aid. One Asian, male emerging adult (#86) said of his parents, “If it’s for the family, especially if it’s for the kids, they rarely hesitate [to spend money].” A White mother (#104) described her and her husband’s willingness to help their emerging adult children even as they encouraged them to be financially independent:

At that point they needed to get a job and start figuring out how they were going to make it work to pay for everything… [But] we had this conversation outright, too: “Don’t starve to death. We are here for you if you need us. We will help you, but we want you to work towards being independent.”

A White, female emerging adult (#14) described a similar system from the child’s perspective: “If my dad notices my bank account is getting low, he usually adds 100 dollars or so. So they’re still helping…”

According to participant reports, some parents were willing to give despite not having the means. One White, female emerging adult (#138) shared,

[My parents] don’t have money to pay for my college, so it’s all on me. … [But my dad] sits me down and says, “How are you doing financially? Do you need more spending money? Do you need me to help you out?”

A Latina emerging adult (#80) explained a similar, potentially risky willingness to give family financial aid: “[My parents] are very open with money. … They never den[y] money to my sister or me. … Even if [they do not] have it, [they] will always figure it out.” In contrast, other participants reported parents who withdrew family financial aid in order to teach self-sufficiency. For example, this Black, female emerging adult (#140) related,

Recently I was having financial problems, and I’m always used to calling my mom and dad like, “Mom and Dad, I need this, I need that.” But the last time I called, [my mom] was like, “Figure it out, I can’t keep helping you.” … That has definitely taught me to budget my money better. Of course in a desperate situation they would be there, but you can’t always depend on your parents. You have to declare some kind of independence, and that last time I [called] … gave me a wake up call because she told me she can’t help me no more. It was like, “Wow. Okay.”

Despite their varied approaches, these parents of emerging adults seemed to have given financially (or not given) out of love and as an investment in their children.

Indeed, many participants described sacrifices made by parents for their children. Sometimes these sacrifices were great. For example, a Latina emerging adult (#119) shared, “I come from immigrant parents [who] didn’t go to college, and they weren’t given the opportunities that I have. So they came here to not see me struggle.” A Black mother (#146) remembered,

I [had] my first child out of wedlock. … I was 21, I was away at school, and I ended up going back home. [My mom] told me, “I’m here to help you.” … I watched her work two jobs, and … I saw her take all-nighters. I saw her get up at 3 o’clock in the morning to go to work…

Some reports of parental sacrifice were for children’s education. One White father (#110) stated, “If our primary income is insufficient … we will take on extra work … for the educational need of our kids or something [else that is] important [to] the family.” Other sacrifices were for children’s work experience. A White, male emerging adult (#20) recalled, “I had a newspaper route from ages 10 to 13. My dad would drive me and wake me up. [Laughs] It was probably more his job than mine!” Another White, male emerging adult (#34) said,

The first time that I went and got a job outside the home was mowing my neighbor’s lawn when I was 10. That was the springboard that helped me have a lawn company in high school. My parents invested in me [and bought] the nice mower and trailer and stuff.

Sacrifices were reportedly also made for children’s personal development, such as for extra-curricular activities. One White, male emerging adult (#74) said of his parents,

They were very much focused on giving us … what was going to be good for us as kids. My sister’s very musically inclined, my brother likes computers a lot, and I like sports. … So they used the money that way. Now looking back, I realize how much they actually spent on us to do those kind of things because it’s not cheap. But money was never really an issue, even in the hard times. They never focused on it. Let’s get everyone healthy. Let’s get everyone going well. And that’s what matters the most.

A Black mother (#146) shared,

I have my younger daughter taking piano lessons, and that’s a sacrifice … I want to make sure that she always has something [to remind her of] the sacrifice that was made, how it will help her later in life, and [that] I made a difference.

According to reports, many participants recognized and appreciated the sacrifices and investments their parents had made for them. A Black, female emerging adult (#120) realized, “[My parents] probably sacrificed their own needs … [so that my brother and I] were always able to do sports … They always found a way.”

Several participants seemed to have observed and experienced intergenerational financial giving not only from parent to child but also from child to parent. One Latina emerging adult (#139) said, “To this day [my mom] gives some money to her father. My grandfather is in his 70 s … he’s really sick and still works. My mom tries to give him money so he doesn’t have to work that much.” Another Latina emerging adult (#119) shared the following account of her father and uncles helping her grandparents:

My grandparents still lived in Mexico, and then two years ago they had all kinds of health issues. … All of the uncles contribute, even though they’re … not making a lot of money. But they still manage to put all their money together to make ends meet to pay for the duplex that my grandma and grandpa are staying in … and they’re putting their money together to pay for the hospital bills…

Whether through facilitating family experiences, sacrificing for children, or giving financial aid to family members, parents reportedly taught their children to give through investments in family. One Latina emerging adult (#125) put it this way: “[My parents] use their money for the happiness of their kids. … Families are important, and I was taught that. I don’t really care about materialistic things.” Similarly, a White, male emerging adult (#74) said, “[My parents] used money as a tool … [to] build relationships….”

Discussion

In this study, 90 undergraduate students (ages 18–30) from three diverse universities were interviewed, along with 17 of their parents and eight of their grandparents regarding what and how their parents taught them about money, and (for parents and grandparents) what and how they taught their children about money. Of the 115 interviews, 95 mentioned financial giving as a topic that they learned and/or taught. This paper stemmed from the Whats and Hows of Family Financial Socialization project (LeBaron et al. 2018), which was not specifically about financial giving but about financial socialization generally. In the majority of interviews, the interviewer did not specifically ask questions about giving—the participants themselves identified it as a central element of financial socialization. It seems that perhaps giving emerged because it is one of the primary principles that many children are learning about money.

In this paper, we explored the research question “How do children learn about financial giving from their parents? In other words, how is financial giving transmitted across generations?” Three core themes were presented and analyzed related to financial giving: “Charitable Donations,” “Acts of Kindness,” and “Investments in Family.” In our sample, charitable donations were often (but not always) related to religiosity, such as through faith-based contributions. Many participants believed that making religious donations, especially consistently, gave them spiritual and financial blessings. The importance of consistency for reaping benefits from giving is reflective of the findings of Smith and Davidson (2014). Acts of kindness involved more informal financial giving to those in need, such as to neighbors or even strangers. Investments in family included family experiences (e.g., family vacations), monetary aid given to family members, and sacrifices made for children (but also sacrifices adult children sometimes made for their parents).

In regards to the participant-reported blessings, participants seemed to find happiness and other personal rewards from all three types of financial giving, consistent with the warm glow hypothesis (Paulus and Moore 2017). However, participant giving seemed to sometimes be a true sacrifice at personal cost (Fagin-Jones 2017). Additionally, participants seemed to feel happiness and other rewards as a result of observing their parents’ giving, when the participants themselves were not otherwise benefitted (Harbaugh et al. 2007). These two observations lend support for the pure altruism hypothesis. Therefore, consistent with the findings of Harbaugh et al. (2007), there seems to be evidence for both the pure altruism and warm glow hypotheses. Regardless of motive, as Marks et al. observed in their qualitative study on family finance (2010), participants who invested in others “seemed to feel that [they] received even more in return” (p. 448).

For all three types of giving, participants seemed to care deeply about passing on habits of giving and the principles or meanings behind those habits. Data suggested that in many cases these habits and meanings were indeed internalized and valued. For all themes but especially for charitable donations, a sense of religious duty seemed to be a driving force behind some participants’ giving behaviors. For the latter two themes, one of the reasons behind participants’ giving seemed to be a desire to reciprocate—they had been recipients of others’ generosity and wanted to pass it on. For all three themes, as will be discussed further in the conclusion, the primary reason behind giving seemed to be a selfless desire to help others.

The findings both provide support for and build on family financial socialization theory (Gudmunson and Danes 2011). As mentioned earlier in the paper, the current study was built on several assumptions from the theory, including (a) parents are the primary financial socialization agents, (b) what children do and do not learn about finances from their parents will influence their future financial wellbeing, and (c) personal and family demographics, family relationships, family interactions, and purposive socialization all influence the socialization of financial giving. The findings support these assumptions in the context of financial giving specifically in that (a) parents seemed to have a major influence in their children’s socialization of financial giving, (b) participants who had been socialized to give reportedly received benefits from their giving, and (c) various personal and relational considerations as well as socialization processes and methods seemed to influence the socialization of financial giving (as explored throughout the Discussion). Although Gudmunson and Danes (2011) identified giving as a component of financial socialization, the theory did not go into depth on the topic. The current study built on the theory in several ways, including identifying three topics or types of financial giving, and exploring how various socialization methods (discussion, modeling, and experiential learning) may be employed in teaching the various types of giving.

The findings also support the limited previous research concerning methods of intergenerational socialization of financial giving: evidence was found of parents utilizing modeling (McAuliffe et al. 2017; Ottoni-Wilhelm et al. 2014), discussion (Kim et al. 2011; Ottoni-Wilhelm et al. 2014), and experiential learning (Kim et al. 2011; Tasimi and Young 2016) in their teaching. While the first two themes were taught/learned through all three methods, investments in family seemed to be taught/learned primarily through modeling. That is, there seem to be many successful ways for charitable donations and acts of kindness to be passed on to the next generation. For some participants, a combination of methods seemed most effective. On the other hand, intrafamilial giving seems to be most potently learned by observing parents’ investments in and sacrifices for other family members. In all three themes, while children seemed to be more giving due to their parents’ example, parents’ own financial giving seemed to in turn be motivated by an awareness that their children were watching their behavior. In this way, intergenerational cultivation of financial giving behaviors seemed to be facilitated both from parent to child as well as from child to parent. This concept is reflected in the literature: just as parents influence children’s development, so do children influence their parents’ adult development (Palkovitz et al. 2003).

Although a full intergenerational analysis is beyond the scope of this paper, there is some evidence of intergenerational interaction regarding the socialization of financial giving. For example, #47 is the daughter of #113, who is in turn the daughter of married grandparents #115 (all White). Mother #113 said, “I think that [tithing] is the most important financial principle that [my children] could learn—to be generous … and giv[e] to others.” Indeed, her daughter (#47), stated the following: “[My siblings and I] were taught to always pay tithing.” The following excerpt from the interview of #113’s parents (#115) seems to give insight into how #113 learned to value financial giving:

Grandmother: Well … [our children knew] that we paid tithing … We also taught them about the blessings of tithing…

Grandmother: We got the little banks that have spending, saving, and tithing divisions in them. When they got their allowance that is where they put it

Another generation of financial socialization was also discussed in Interview #115:

Interviewer: How did [your parents] teach you [about tithing]?

Grandfather: They paid.

Grandmother: Mostly by example. They would be [open] about tithing [even when we were] at a young age. We always paid tithing on our little nickels and dimes we got.

…

Grandfather: They would often ask, ‘Did you pay your tithing?’ That’s how they teach, by doing and asking and living it.

Thus, in this family the socialization of financial giving seems to have taken place across at least four generations: #47 (emerging adult), #113 (mother), #115 (grandparents), and the great-grandparents.

To give one more example of intergenerational interaction, #156 is the grandmother of female emerging adult #126 (both Latina). They both referenced #134 (Latina mother) as they spoke of financial giving. Of her mother’s habit of giving, #126 said, “Any way she could help, she would. … She would tell us that ‘So-and-so needs money, and that’s okay because I have a little bit saved up, so I am going to help them.’” Interview #156 lends some insight into how #134 (daughter of #156) may have learned to be generous: “[I] started teaching [my daughter] the value of sharing. … There are a lot of people in the world that really need things, and we have it all, thank God, and we need to learn how to share.” Based on these quotes, perhaps the socialization efforts of #156 influenced the financial giving of both her daughter (#134) and, indirectly, her granddaughter (#126).

Implications

First and foremost, this study has implications for parents. The findings suggest that giving may be an important financial principle for parents to teach their children—this teaching, or lack thereof, may shape not only children’s financial behaviors but also their financial attitudes and values. The data suggest that consistency is key to receiving benefits from giving. Perhaps optimal socialization of financial giving would include consistency in modeling, discussion, and experiential learning. In regards to modeling, parents should make their giving visible to their children so that their children have the opportunity to observe and learn from their parents’ example. Parents could use both their own and others’ giving as catalysts for discussion about the importance of and reasons for giving. They could also highlight the generosity they themselves have received. According to participant reports, children’s experiential learning can occur both by giving their own money and also by actively participating in parents’ giving. Parents can facilitate both types of experiential learning and should consider the developmental suitability of activities and amounts of money. Data suggest that as parents teach their children to give, other family members such as grandparents may be helpful models; discussants; and facilitators of experiential learning.

These findings also have implications for another group of financial socialization agents: educators (e.g., family life educators of both parents and couples, financial educators, etc.). They should include giving as a unit in their financial curricula right alongside budgeting and saving. Educators can also play an important role in optimizing family financial socialization. They can help parents identify ways in which they can model giving for their children. They can also help parents prepare for and engage in discussions with their children; for example, they could help parents identify their own beliefs about giving—including how important it is and why, in what ways they would like to give, and how they plan to pass these values and habits on to the next generation. Educators can also assist parents in facilitating developmentally-appropriate giving experiences for their children.

Finally, charities and other non-profit organizations may want to invest in the optimization of the intergenerational socialization of financial giving—it could yield consistent donations that live on with future generations. Convincing adults to teach their children may be just as (or even more) important for the success of these organizations than convincing adults to give. One way they could do this would be to facilitate whole-family involvement in donating (e.g., family walk-a-thons).

Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations. The emerging adults (n = 90) in the sample were all undergraduate students enrolled in family finance classes; therefore, these participants’ financial socialization experiences may be different from those of other emerging adults (e.g., higher SES) and even other college students (e.g., greater sensitivity to financial principles). A higher SES sample may be especially limiting to a study on financial giving because theoretically giving may be more possible for those with expendable resources. However, sometimes those with the least seem to give the most (Marks et al. 2006), so while the mechanisms may look different, perhaps some of the same principles apply across SES. Future research should investigate potential differences in giving processes by SES, race, family structure, cohort/generation, and other demographic and relational characteristics. Future research could also explore whether a family member’s illness may influence giving to related causes or organizations. The number of parents (n = 17) and grandparents (n = 8) sampled was relatively small, and a wider range of these generations’ perspectives would be valuable. The interviews were retrospective, and while that can be a strength in that the most potent and influential experiences are likely to be the ones remembered, it is true that some experiences may have been misremembered or forgotten. Future studies could qualitatively explore the intergenerational socialization of financial giving with a sample that includes children. Additionally, while Smith and Davidson’s (2014) landmark study identified personal benefits of financial giving, there is evidence in the current study of potential relational benefits; future research should further explore this possibility. Finally, it is hoped that the topics, methods, processes, and meanings related to financial giving identified in this paper will be further explored in and enrichen future quantitative research on this topic.

Conclusion

Former US Vice President Joe Biden said, “Don’t tell me what you value. Show me your budget, and I’ll tell you what you value” (VP44 2016). According to participant reports of how they spent their money, one of the financial principles they highly valued was giving. It may seem ironic, but perhaps the most important thing we can teach children about money is to (appropriately) give it away. For all three types of giving presented in this study, a focus on helping others seemed key. As a Black, female emerging adult (#120) said, “I think [my parents] were trying to teach [me that] it’s not all about us. Money is great … but … we have that money to give.” While we did not quantitatively measure outcomes of giving, some participants seemed to describe both personal and relational benefits. This reflects the findings of Smith and Davidson (2014): those who routinely give tend to be happier, healthier (both physically and mentally), and feel a greater sense of purpose. Indeed, several participants, such as this White grandmother (#111), learned and hoped to pass on the idea that “when giving you receive.”

References

Chan, K. (2010). Father, son, wife, husband: Philanthropy as exchange and balance. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 31(3), 387–395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-010-9205-4.

Cowley, E. T., Paterson, J., & Williams, M. (2004). Traditional gift giving among Pacific families in New Zealand. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 25(3), 431–444.

Daly, K. J. (2007). Qualitative methods for family studies and human development. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Einolf, C. J., & Philbrick, D. (2014). Generous or greedy marriage? A longitudinal study of volunteering and charitable giving. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(3), 573–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12115.

Fagin-Jones, S. (2017). Holocaust heroes: Heroic altruism of non-Jewish moral exemplars in Nazi Europe. In S. T. Allison, G. R. Goethals, R. M. Kramer, S. T. Allison, G. R. Goethals, & R. M. Kramer (Eds.), Handbook of heroism and heroic leadership (pp. 203–228). New York: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Gagné, E. D., & Middlebrooks, M. S. (1977). Encouraging generosity: A perspective from social learning theory and research. The Elementary School Journal, 77(4), 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1086/461059.

Gilbert, D. (2006). Stumbling on happiness. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

Gudmunson, C. G., & Danes, S. M. (2011). Family financial socialization: Theory and critical review. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(4), 644–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-011-9275-y.

Handel, G. (1996). Family worlds and qualitative family research. Marriage and Family Review, 24, 335–348.

Harbaugh, W. T., Mayr, U., & Burghart, D. R. (2007). Neural responses to taxation and voluntary giving reveal motives for charitable donations. Science, 316(5831), 1622–1625. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1140738.

Jorgensen, B. L., & Savla, J. (2010). Financial literacy of young adults: The importance of parental socialization. Family Relations, 59(4), 465–478. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00616.x.

Kim, J., LaTaillade, J., & Kim, H. (2011). Family process and adolescents’ financial behaviors. Journal of Family Economic Issues, 32, 668–679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-011-9270-3.

LeBaron, C. (2005). Cultural identity among Mormons: A microethnographic study of Family Home Evening. In W. Leeds-Hurwitz (Ed.), From generation to generation: Maintaining cultural identity over time. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

LeBaron, A. B., Hill, E. J., Rosa, C. M., & Marks, L. D. (2018). Whats and Hows of Family Financial Socialization: Retrospective Reports of Emerging Adults, Parents, and Grandparents. Family Relations, 67(4), 497–509. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12335.

LeBaron, A. B., Runyan, S., Jorgensen, B. L., Marks, L. D., Li, X., & Hill, E. J. (2019). Practice makes perfect: Experiential learning as a method for financial socialization. Journal of Family Issues, 40(4), 435–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X18812917.

Lowrey, T. M., Otnes, C. C., & Ruth, J. A. (2004). Social influences on dyadic giving over time: A taxonomy from the giver’s perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 30(4), 547–558. https://doi.org/10.1086/380288.

Marks, L. (2015). A pragmatic, step-by-step guide for qualitative methods: Capturing the disaster and long-term recovery stories of Katrina and Rita. Current Psychology, 34, 494–505.

Marks, L. D., Dollahite, D. C., & Baumgartner, J. (2010). God we trust. Family Relations, 59(4), 439–452. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00614.x.

Marks, L. D., Rosa, C. M., LeBaron, A. B., & Hill, E. J. (2019). “It takes a village to raise a rigorous qualitative project”: Studying family financial socialization using team-based qualitative methods. SAGE Research Methods Cases. London: SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526474773.

Marks, L. D., Swanson, M., Nesteruk, O., & Hopkins-Williams, K. (2006). Stressors in African American marriages and families: A qualitative study. Stress, Trauma, and Crisis: An International Journal, 9, 203–225.

McAuliffe, K., Raihani, N. J., & Dunham, Y. (2017). Children are sensitive to norms of giving. Cognition, 167, 151–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2017.01.006.

Ottoni-Wilhelm, M., Estell, D. B., & Perdue, N. H. (2014). Role-modeling and conversations about giving in the socialization of adolescent charitable giving and volunteering. Journal of Adolescence, 37(1), 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.10.010.

Palkovitz, R., Marks, L. D., Appleby, D. W., & Holmes, E. K. (2003). Parenting and adult development: Contexts, processes and products of intergenerational relationships. In L. Kucynski (Ed.), The handbook of dynamics in parent–child relations (pp. 307–323). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Paulus, M., & Moore, C. (2017). Preschoolers’ generosity increases with understanding of the affective benefits of sharing. Developmental Science, 20(3), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12417.

Prendergast, G. P., & Maggie, C. W. (2013). Donors’ experience of sustained charitable giving: A phenomenological study. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 30(2), 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363761311304942.

Rosa, C. M., Marks, L. D., LeBaron, A. B., & Hill, E. J. (2018). Multigenerational modeling of money management. Journal of Financial Therapy, 9(2), 54–74. https://doi.org/10.4148/1944-9771.1164.

Rushton, J. P. (1975). Generosity in children: Immediate and long-term effects of modeling, preaching, and moral judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 31(3), 459–466. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076466.

Serido, J., & Deenanath, V. (2016). Financial parenting: Promoting financial self-reliance of young consumers. Handbook of consumer finance research (2nd ed., pp. 291–300). New York: Springer.

Shim, S., Barber, B. L., Card, N. A., Xiao, J. J., & Serido, J. (2010). Financial socialization of first-year college students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 1457–1470.

Smith, C., & Davidson, H. (2014). The paradox of generosity: Giving we receive, grasping we lose. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199394906.001.0001.

Sober, E., & Wilson, D. S. (2000). Summary of: ‘Unto others: The evolution and psychology of unselfish behavior’. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 7(1–2), 185–206.

Su, H., Chou, T., & Osborne, P. G. (2011). When financial information meets religion: Charitable-giving behavior in Taiwan. Social Behavior and Personality, 39(8), 1009–1020. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2011.39.8.1009.

Tasimi, A., & Young, L. (2016). Memories of good deeds past: The reinforcing power of prosocial behavior in children. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 147, 159–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2016.03.001.

VP44. (2016, February 9). I often say: Don’t tell me what you value. Show me your budget & I’ll tell you what you value. #POTUSBudget makes our values crystal clear [Twitter Post]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/vp44/status/697132255752261632?lang=en.

Webley, P., & Nyhus, E. K. (2006). Parents’ influence on children’s future orientation and saving. Journal of Economic Psychology, 27, 140–164.

White, G. M., & Burnam, M. A. (1975). Socially cued altruism: Effects of modeling, instructions, and age on public and private donations. Child Development, 46(2), 559–563. https://doi.org/10.2307/1128159.

Wu, S., Huang, J., & Kao, A. (2004). An analysis of the peer effects in charitable giving: The case of Taiwan. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 25(4), 483–505.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Jeff Hill, Loren Marks, and Jeff Dew for their helpful reviews of earlier drafts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Ashley LeBaron declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

IRB approval for the research project was secured in February 2015.

Informed Consent

All participants signed a consent form prior to participation.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

LeBaron, A.B. The Socialization of Financial Giving: A Multigenerational Exploration. J Fam Econ Iss 40, 633–646 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-019-09629-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-019-09629-z