Abstract

Social processes play a major role in developing children into capable producers, consumers, and agents of financial socialization in adulthood. The latest research continues to demonstrate that parents exert more influence than educators, peers, media, and self-learning in promoting good financial behavior and experiencing financial wellbeing, although all these factors play a role in financial socialization. Research has also progressed in elucidating the mechanisms of social interaction and the psychosocial characteristics of individuals that pair with financial literacy to achieve desirable financial outcomes. Longer periods of financial interdependence are realities for many families living in fluctuating economies that require ever greater investments in education, often accompanied by student loan debt, to achieve long-term financial success. Thus, it is important that future financial socialization research considers longitudinal processes that span adolescence, early adulthood, and the midlife, while better attending to economic realities of time and place. Theoretical foundations of financial socialization have continued to take shape and can benefit from further development and use as the basis for empirical work.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

Financial socialization is a subset of general human socialization, which Grusec and Hastings (2015) define as “the way in which individuals are assisted in becoming members of one or more social groups” (p. xi). Within socialization processes, more experienced members of the group help newer members incorporate the group’s values, norms, rules, roles, and attitudes into their thinking and behavior. Recent theorizing and research among developmental scholars, however, indicates that social novices are active in their own socialization through reflection, selectivity in what they accept from socialization agents, , and their attempts to socialize older group members (Grusec & Davidov, 2010; Grusec & Hastings, 2015; Kuczynski, Parking, & Pitman, 2015). Various social groups serve as contexts for financial socialization. These may include, but are not limited to family , peer groups, workplaces, educational institutions, religious organizations, racial and ethnic groups. Developmental contexts such as life transitions, economic cycles, and social policy changes also play a role.

Recent financial socialization research has devoted some attention to studying family interactions during the developmental stages of childhood and adolescence (e.g., Kim, LaTaillade, & Kim, 2011; Kim, Lee, & Tomiuk, 2009; Romo, 2014). However, there has been a much greater focus on gathering retrospective data from young adult populations, and especially college student populations about childhood financial experiences or interactions with their parents and connecting them to outcomes such as financial knowledge, behaviors, or attitudes (e.g., Clarke, Heaton, Israelson, & Egett, 2005; Kim & Chatterjee, 2013; Shim, Barber, Card, Xiao, & Serido, 2010; Shim, Xiao, Barber, & Lyons, 2009). This line of research supports a common view of financial socialization as a process that extends from childhood into early adulthood in which children develop consumer roles with the help of parents, teachers, friends, work experiences, and the media and follow the normative pattern of gaining financial independence from parents. However, over the last several decades there has been a call to view financial socialization as a process that extends over the entire life course of individuals and families (Gudmunson & Danes, 2011; Moschis, 1987; Sherraden, 2013; Stacey, 1987).

Financial Socialization’s Relationship to Economic and Consumer Socialization

One of the earliest mentions of the term financial socialization appears in a study that evaluated the patterns of financial product acquisition by married couples. The authors found a reliably common pattern of asset acquisition across multiple age groups and concluded that one of the most important aspects of their work was providing “support for the notion that there is a financial socialization process” (Stafford, Kasulis, & Lusch, 1982, p. 414). It is not uncommon to see the terms financial, consumer, and economic socialization used interchangeably or applied to the same types of research questions. Apotential reason for this may be that much more work has been conducted with the labels of economic socialization and consumer socialization. It has been argued, though, that these types of socialization may not be interchangeable. In fact, some scholars have pictured financial socialization as encompassing consumer socialization and both of these as subsets of economic socialization (Alhabeeb, 1996, 2002; Stacey, 1987).

According to Stacey (1987), burgeoning research in economic and consumer socialization during the twentieth century adopted ideas from other areas of socialization research, such as political socialization. Stacey’s review of economic socialization includes a wide range of topics including the major theories and approaches that were being utilized and major topics of interest including children’s understanding of money, ownership, consumer socialization, and economic inequality. Additionally, Stacey points out that while economic socialization has its origins in childhood, it is likely that a “significant amount [of] economic socialization takes place during the adult years, particularly in association with life-cycle changes in occupational, marital, and family roles” (p. 27). Despite this early recommendation, research labeled under the broad umbrella of economic socialization continued to focus mostly on children (Berti & Bombi, 1988; Berti & Grivet, 1990; Furnham, 1996). Webley (1996, 2005) has contributed a great deal to research concerned with how children come to understand the economic world. One of Webley’s contributions to the economic socialization literature has been the exposition of the economic world of children which can involve relationships with adults or relationships with other children. On the one hand, many children, especially in Western economies, are dependent on adults for material and financial resources, which has implications for how children obtain income and view and practice saving money . At the same time, children participate in their own autonomous economies or playground economies wherein exchange takes place between children themselves. In some cases, according to Webley, children operating in their autonomous economy may reflect adult economic motivations and at other times may be motivated by non-economic objectives, such as friendship dynamics. From both Stacey’s and Webley’s discussions of economic socialization research, it becomes evident that children likely come to understand various dimensions of their financial and economic worlds that may or may not be an accurate representation of the “adult” economy.

Ward (1974) first conceptualized consumer socialization and outlined some of the major issues that would be examined in much of the empirical work to come. Ward defined consumer socialization as processes through which “young people acquire skills, knowledge, and attitudes relevant to their functioning as consumers in the marketplace ” (1974, p. 2), and this definition has influenced the view that consumer socialization is confined to the earlier years of life. Moschis (1987), who studied marketing under Ward, discussed how the interest in consumer socialization stemmed out of the concern that marketers could potentially take advantage of children’s susceptibility to appealing advertising that would turn into poor consumption patterns, even into adulthood. Therefore, Moschis saw a need to understand the interaction between children’s cognitive development and social environments that could have implications for consumer behavior. Moschis (1985, 1987) and Moschis and Churchill (1978) provided some foundational work on communication processes in consumer socialization as well as a widely used theoretical model of consumer socialization. John (1999) provided a comprehensive review of consumer socialization and also proposed a conceptual framework to show how Piaget’s perceptual, analytical, and reflective stages of child cognitive development function in terms of consumer awareness, decision-making, and consumption across childhood.

The reviews that specifically focus on each type of socialization demonstrate that consumer socialization stays more confined to issues relevant to marketplace activity, and most often purchasing activity (John, 1999; Moschis, 1987; Ward, 1974), while economic socialization researchers may be interested in topics such as how children come to understand supply and demand or how individuals are socialized to understand and internalize class differences (Stacey, 1987; Webley, 2005). Financial socialization research may direct some attention to the development of purchasing behavior and attitudes, but often with a broader focus on the interactional process of individuals that live in a world of constrained resources, widely available credit, changing financial regulations, and a need to manage conflicting wants and desires. Danes (1994) defined financial socialization as “the process of acquiring and developing values, attitudes, standards, norms, knowledge, and behaviors that contribute to the financial viability and individual well-being” (p. 28). In recent years, financial socialization has likely gained more research interest among scholars, policymakers, and educators as a way to situate efforts aimed toward increasing consumer financial literacy, capability, and wellbeing within individual and family social contexts and relationships. Because of the popularity and prevalence of increasingly complex financial services and products offered by businesses in a globalized economy, the move away from employer-sponsored defined benefit retirement plans to individual defined contributions plans, and the increasing cost and necessity of higher education, it is important to link any type of financial education or capability-building program to culturally and environmentally sensitive financial socialization conceptualizations.

Socialization and Capability

Socialization theorists have contended that socialization processes in numerous social contexts begin in infancy or early childhood. Grusec (2011) provides several reasons as to why parents likely serve as the primary socializers of the child’s social world. Parents are “biologically prepared” to be the caregivers of their children in order to ensure “their own reproductive success,” and it is an expectation in most societies that parents will fulfill the role of primary caregiver (Grusec, 2011, pp. 244–245). As the primary caregiver to the child, a parent determines how to allocate resources to the child, is positioned to regulate influences from the child’s social environment , and has the capacity to create a warm and affectionate relationship with the child (Grusec, 2011). It is likely that all of these factors influence financial socialization processes; however, we speculate that the role of parents as resources managers and the ways in which they interact with their children around the allocation of resources have a strong influence on family financial socialization processes. Both parents and children interpret and assign meanings to interactions with each other and observations of the other’s behavior (Grusec, 2011; Kuczynski et al., 2015).

A common assumption often tied to financial socialization is that the processes are guided by the intent to help young consumers develop financial capability to achieve financial wellbeing. Gudmunson and Danes (2011), however, suggested that most financial socialization in the family is more likely to be non-purposive and is a function of the day-to-day interaction patterns in the family. Financial socialization is a process and that is not always goal-oriented or intentional in every social setting. In other words, for good or for ill, everyone is financially socialized; however, some people’s financial socialization may lead them toward detrimental beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors in the context of larger financial and economic systems in which they live. Yet, some of these beliefs, attitudes, or behaviors could be desirable in more immediate social groups like the family or peer groups. For example, parents may establish allowance systems (Beutler & Dickson, 2008) or financial reward systems that support goals for family interaction and cohesion but that may not mirror the realities of larger economic systems. Financial capability can be considered the ability of applying appropriate financial knowledge and performing desirable financial behavior to achieve financial wellbeing in a given economic setting (Lusardi & Mitchell, 2014; Xiao, 2015; Xiao, Chen, & Chen, 2014). Research over the past decade has had an increased focus on how children develop financial values , attitudes, knowledge, and behavior that promotes financial capabilities that can bridge the gap between family and educational settings and the economic realities of independent adulthood (Drever et al., 2015).

Financial Socialization Across Time

It has been common practice in past financial socialization research to conceptualize studies as pitting the influences of socializing agents against each other to see which agents such as parents, educators, peers, media, and so forth “win out” in best predicting financial outcomes. While useful in many instances, this conceptualization is also a static view that largely ignores what is more likely to be waxing and waning influences of particular agents over time . Parental influences have been considered in virtually all studies that compare agents of financial socialization agents, but there are very few studies, that examine long-term romantic partners as agents of financial socialization (Dew, 2008, 2016). This is lamentable, as many individuals will eventually live a greater portion of their lives with a romantic partner than they have with parents. This also is likely to be a function of a lack of suitable secondary data, and the untested assumption that financial socialization does not change meaningfully once a person reaches adulthood. Yet scholarship that considers various agents of socialization in the context of the long view, including theoretical work , may help in promoting a more nuanced view of financial socialization agents across time.

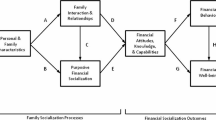

A family financial socialization conceptual model was proposed (Danes & Yang, 2014; Gudmunson & Danes, 2011). In this conceptual model, family financial socialization can be conceptualized as two major parts, family socialization processes and financial socialization outcomes. Processes involve personal and family characteristics contributing to family interaction/relationships and purposive financial socialization. These factors contribute to financial attitudes, knowledge, and capability, which in turn contribute to distal outcomes, financial behavior and financial wellbeing.

Based on this model, two different categories of financial socialization processes take primacy in different developmental periods: processes of acquisition and processes of modification. Once individuals reach adulthood, they have likely acquired a set of financial attitudes, knowledge, values, norms, and skills as well as a certain level of agency over their financial affairs. Each of these financial characteristics will in turn influence financial behavior patterns and perceptions of financial wellbeing. In adulthood, therefore, socialization processes will more likely modify the existing set of individual financial traits and characteristics rather than leading to the acquisition of new ones. Acquisition processes, however, may still occur in adulthood. Specifically, periods or events of greatly felt change may trigger new acquisition or more pronounced modification during adulthood.

Parents and the family of origin are not the only significant agents of socialization. Across the life course, both youth and adults receive messages and interact with numerous influential sources of financial information and observe financial behavior in a variety of contexts. School financial education can be an important socialization tool. Many financial literacy initiatives are geared toward embedding personal finance education in elementary through high school curriculum as well as college-level coursework (Batty, Collins, & Odders-White, 2015; Fox, Bartholomae, & Lee, 2005: Mandell, 2009; McCormick, 2009; Xiao, Ahn, Serido, & Shim, 2014). The underlying assumption of many financial literacy education programs is that increasing financial knowledge should increase positive financial outcomes and decrease negative financial outcomes, but research findings have yielded mixed findings on this point (Fernandes, Lynch, & Netemeyer, 2014; Hastings, Madrian, & Skimmyhorn, 2013; Miller, Reichelstein, Salas, & Zia, 2014). Financial education researchers have suggested that experiential or just-in-time approaches may have more long-term impacts on individual financial behaviors and economic wellbeing (Hathaway & Khatiwada, 2008; Peng, Bartholomae, Fox, & Cravener, 2007). Recent research based on a national data set suggests the exposure to high school and college financial education is positively associated with financial capability factors (Xiao & O’Neill, 2014). Furthermore, Danes and Brewton (2014) found that among high school students that participated in competency-based personal financial planning coursework, some students reported discussing financial matters with their families at greater frequencies after the completion of the curriculum. This raises interesting questions about how financial literacy education may be useful in socializing not only students but their families as well. These possibilities merit future research attention.

A common theme in the study of socialization during adolescences is that the influence of parents as agents diminishes and the importance of peers increases in numerous domains of social life (Smetana, Robinson, & Rote, 2015). This may not be the case in the area of finances because children are often still dependent on parents for material support at this stage in life, especially in Western economies. Parental influences likely outweigh the effects of peers, media, and educators well past adolescence. The effects may be greater in the financial domain than they are in other areas of life where the influences of peers seem to unseat the influence of parents more rapidly (Shim et al., 2010). However, peer groups, the workplace, and religious organizations may be influential agents of financial socialization in adulthood, although socialization researchers have not yet begun to conduct much research in this area.

Besides family and school, media can also be an important agent for youth financial socialization. A study based on a national sample of youth in South Korea showed that those who chose media as their primary financial socialization agent exhibited higher levels of financial literacy (Sohn, Joo, Grable, Lee, & Kim, 2012). However, Gudmunson and Beutler (2012) found that among a primarily middle-class, White sample of American adolescents, those that had higher media consumption expressed greater conspicuous consumption attitudes . More research on media effects on financial socialization using data from other countries and among various age, class, racial/ethnic groups is needed.

Theoretical Advances in Recent Research

A key defining difference between financial socialization and other commonly used research frameworks including financial literacy, financial capability, and behavioral economics is that financial socialization more fully considers ties to human development over time. A socialization approach proposes that intra-individual change and inter-individual differences emerge from variations in social interaction and relationships that develop over time. Financial socialization approaches that consider change over significant periods of time are, therefore, consonant with life course theories of human development. Much of the recent research has expanded to provide a fuller picture of the mechanisms and outcomes of financial socialization. To facilitate some examples of theoretical advances, we offer a generalized theoretical model with different classes of variables that are involved in financial socialization (see Fig. 5.1).

Studies that compare the relative influence of parents, peers, schools, and self-education help to emphasize the notion that social roles and relationships are the settings wherein socialization takes place. Thus, examples of the agent–novice relationship include parents-to-children, teacher-to-student, peer-to-peer, and so forth. Recent evidence has continued to find that parents are more influential as agents of financial socialization than peers and educators (Shim, Serido, Tang, & Card, 2015), suggesting that the socialization mechanisms may differ within different types of social relationships. Examples of socialization mechanisms that have been previously identified in theoretical papers on financial socialization (John, 1999; Jorgensen & Savla, 2010; Moschis, 1987; Ward, 1974; Xiao, Ford, & Kim, 2011) are included in Fig. 5.1.

Mechanisms of financial socialization produce proximal socialization outcomes, which are theoretically distinct from distal outcomes because they are “socially imbued individual characteristics adapted over time [which are carried] from context to context although they are variously expressed in each circumstance” (Gudmunson & Danes, 2011, p. 649). By contrast, financial behavior and financial wellbeing are considered distal socialization outcomes, because they can be more objectively determined, are more context dependent (i.e., especially financial behavior), and because they may be shared properties (i.e., financial wellbeing). This general model can be helpful as a classification tool for considering the expanding, and sometimes bewildering, array of variables that appear in multi-disciplinary research on financial socialization.

Recent scholarship has taken advantage of national data that tracks both family interaction and financial outcomes, and important linkages are being discovered. For example, Tang, Baker, and Peter (2015), using nationally representative data, found that parental monitoring had a positive effect on responsible financial behavior, and that female–male gaps in this outcome were eliminated when parental monitoring was consistent. Self-discipline had an even greater positive effect on financial behavior. Implications of these findings are that financial education could be more effective if it synchronously involved multiple family members (Van Campenhout, 2015; Wheeler-Brooks & Scanlon, 2009). This concept of delivering financial education to a system of family members is also a foundational principle in the nascent field of financial therapy (Kim, Gale, Goetz, & Bermudez, 2011). Recent financial socialization and financial capability research have made a major contribution in shifting concerns about the ineffectiveness of financial education (Fox et al., 2005), toward a consideration of how it may be made effective by engaging the family system for support, on the one hand (Serido & Deenanath, 2016) and for paring financial education with direct links to financial services, on the other hand (Bartholomae & Fox, 2016).

Shim et al. (2015) considered the mediating role of mental outcomes (proximal outcomes of socialization) in explaining the impacts that parents, friends, and education had in socializing college students toward healthy financial behavior. Having an attitude of support for particular financial behaviors, along with a sense of control, and confidence in one’s ability to carry through with healthy financial behaviors were important in transmitting socialization experiences. Work by Jorgensen and Savla (2010) is also another good example of the importance of socialization variables tied closely to specific behaviors. They asked participants in an online survey to rate their feelings of safety with, need to understand, and sense of importance for very specific financial behaviors. Their results with an index of these targeted attitudes in predicting an index of the same financial behaviors was very strong. Furthermore, these financial attitude measures fully mediated the relationships between perceived parental influence and financial knowledge in predicting financial behavior. In essence, research that investigates proximal and intermediate outcomes reveals that healthy financial socialization provides various types of motivation that when paired with financial knowledge (Fox et al., 2005; Gudmunson & Danes, 2011) and access to financial supports (Sherraden, 2010, 2013) results in desired financial behavior.

Another theoretical advance has come from the expansion of financial socialization beyond North American populations to consider samples of young people in different economic conditions . Chowa and Despard’s (2014) research on youth living in the regions of Ghana confirmed the importance of parental financial socialization, but also found that youth’s earned income was a critically important factor in predicting positive financial behavior. Conclusions based on older research in the USA (see Beutler & Dickson, 2008) have been ambivalent about the effects of youth work and youth earnings while in pursuit of education. Chow and Despard, however, point out that income for children in Ghana, a much poorer country than the USA and where there are fewer pathways to higher education, can serve as a greater aid to advancement in the context of place (i.e., certain African nations). Karimli, Ssewamala, Neilands, and McKay (2015) reported similar results for children in Uganda. Children in Ghana and Uganda are also more likely to share their income for necessities, whereas children’s pocket change in the USA is usually spent on children’s nonessentials (Alhabeeb, 1996). Future research should more fully consider the meaning of variables in the context of the study population, while considering the context of time and place. Thus, we applaud the internationalization of financial socialization research and urge that context-specific models take into account culture and economic realities that shape financial realities.

Sociodemographic Factors in the Financial Socialization Process

Two of the most widely studied sociodemographic factors included in studies of financial socialization are gender and socioeconomic status. Several studies have found that men and women tend to differ in their financial knowledge and behavioral outcomes (Chowa & Despard, 2014; Tang et al., 2015), but only a handful of recent studies provide insight into the possible divergent socialization paths of males and females. In a study of predominantly White, higher-income college students, Clarke et al. (2005) found that children more commonly described fathers as household financial managers and claimed that fathers modeled financial tasks more frequently. In families where mothers both modeled and taught financial tasks , however, students reported feeling more prepared to perform financial tasks and practiced tasks more frequently as young adults. Overall, male students felt more prepared than female students on a number of financial tasks when they were modeled in the home. In a study of college students from multiple universities, Garrison and Gutter (2010) found a significant gender difference in financial social learning opportunities ; females had higher exposure to financial social learning opportunities across four dimensions (discussions with parents, discussions with peers, observations of parents’ financial behaviors, and observations of peers’ financial behaviors). Tang et al. (2015) observed that parental influence improves young women’s financial behavior more than young men’s.

Income and wealth are the most widely used markers of socioeconomic status and social classin economic and financial socialization literature. It has been speculated that families that hold more wealth and earn a higher income instill greater knowledge and a more diverse financial skill set in their children (Stacey, 1987). Furthermore, Sherraden (2010, 2013) argues that children from wealthier families have more opportunities to learn about financial matters because their parents interact with financial institutions and products more regularly and are more prepared to teach their children about finances whereas low-income parents interact with fewer types of beneficial financial institutions and products and may be less able and willing to teach their children about finances because of distressing economic circumstances. However, recent research findings provide a mixed picture in the area of family socioeconomic status .

Lusardi, Mitchell, and Curto (2010) found associations between parents’ education level and stock ownership with children’s scores on a set of financial literacy measures which supports the view that higher SES families provide a more conducive environment to beneficial financial socialization. However, one study with a nationally representative sample of young people between the ages of 17 and 21 found that those with parents of higher net worth reported having fewer financial worries but also reported feeling less skilled at money management (Kim & Chatterjee, 2013). In a qualitative study of parents’ communication beliefs and practices related to disclosing and concealing various types of financial information to their children, Romo (2011, 2014) found that study participants that reported a variety of socioeconomic statuses believed that communicating with their children about money-related topics is taboo. Using data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) and Transition to Adulthood (TA), Xiao, Chatterjee, and Kim (2014) found that young adult’s perceived financial independence is negatively associated with parental income, financial assistance, and stock ownership.

The Future of Financial Socialization in Theory, Research, and Practice

Financial socialization is a life-long process that is influenced by numerous socialization agents such as family, teachers, peers, and the media. Factors such as gender, socioeconomic conditions of the family and surrounding community, race, ethnicity, types of financial products that are available, public policies, and macroeconomic trends are likely influential in the outcomes of financial socialization. Research that takes a life course perspective of the financial socialization process, although called for over the past several decades, has not yet manifested. Such a perspective should acknowledge that important changes take place in cognitive, socioemotional, and biological development during the course of childhood, adolescence, and emerging adulthood, and therefore, these life stages are important periods for the development of financial attitudes, beliefs, knowledge, standards, skills, and behaviors. However, it is important to remember that “socialization continues throughout the life span as individuals continue to change and develop the skills, behavior patterns, ideas, and values needed for competent functioning in a social context that is constantly changing” (Kuczynski et al., 2015, p. 135). The concept of changing people in a changing social context is significant in the discussion of financial socialization because of the rapid transformations that have become a hallmark of modern economies and financial systems . We contend that wherever there are resources involved in social interactions between individuals at any point in the life course, there are potential implications for financial socialization.

One of the primary functions of the family is socializing its members (Bogenschneider & Corbett, 2004), and family financial socialization is a complex process that needs future theoretical and empirical research to understand its key factors and interrelationships of these factors. It is encouraging that researchers are conducting longitudinal research (Shim et al., 2015) and gathering data from multiple members of family units (Chowa & Despard, 2014). A major limitation of past studies that include financial socialization components is an over-reliance on cross-sectional designs. In fact, one of the broad criticisms that has been leveled at various types of consumer finance research is that the body of research is overly dependent on cross-sectional data (Gudmunson & Danes, 2011). Cross-sectional research presents a formidable challenge for understanding the processes that are part of financial socialization because, by definition, socialization is a process that requires over-time data to be maximally assessed and causality cannot be determined through cross-sectional designs. Furthermore, many cross-sectional studies in the field of consumer finance often use the concept of financial socialization as a theoretical explanation for why certain direct associations are found, but these studies do not include indirect linkages that may present a clearer picture of financial socialization processes.

Finally, the picture that emerges from a synthesis of the literature on financial socialization is that agents of socialization that do make a difference, do so pervasively and with long-lasting effects. The notion that a child is impacted by parents social and financial influences only for the time that they share a roof, and that college students immediately adopt the principles taught them in financial education courses, and that adults individually and rationally make financial decisions is an oversimplified and inaccurate view. While most educators, researchers, and practitioners will admit that the realities are much more complex than this, there is much more that can be done to take emerging views of financial socialization into view in building curriculum, designing studies, and providing financial counseling and planning that are effective. Such work will require refinement and accuracy in measurement, more longitudinal investigations, greater integration of client’s social networks and access to financial institutions in the course of financial education, and a much better understanding of psychosocial motivating factors that arise from financial socialization.

About the Authors

Clinton G. Gudmunson earned his PhD in Family Social Science from the University of Minnesota and is currently an Assistant Professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the Iowa State University. He teaches courses in Retirement Planning, Family Policy, and Research Methods. His research examines financial socialization from a life course perspective and also examines the impacts of economic pressure in family life.

Sara K. Ray is a doctoral student in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the Iowa State University. Her research employs quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods and focuses on the interconnectedness of family financial life within economic, political, social, and cultural contexts. Before commencing her graduate studies, she coordinated school-based financial literacy education initiatives in South Texas. She earned a B.A. in Economics from the University of Texas-Pan American.

Jing Jian Xiao is Professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies, University of Rhode Island. He teaches courses and conduct research in the field of consumer finance. He is the editor of Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning. He is also editing International Series of Consumer Science. He has published many research articles in professional journals and several books in consumer finance. He received his B.S. and M.S., both in Economics, from the Zhongnan University of Economics and Law and Ph.D. in consumer economics from the Oregon State University.

References

Alhabeeb, M. J. (1996). Teenagers’ money, discretionary spending and saving. Financial Counseling and Planning, 7, 123–132.

Alhabeeb, M. J. (2002). On the development of consumer socialization of children. Academy of Marketing Studies Journal, 6(1), 9–14.

Bartholomae, S., & Fox, J. (2016). Chapter 4: Advancing financial literacy education using a framework for evaluation. In J. J. Xiao (Ed.), Handbook of consumer finance research (2nd ed.). New York: Springer.

Batty, M., Collins, J. M., & Odders-White, E. (2015). Experimental knowledge on the effects of financial education on elementary school students’ knowledge, behavior, and attitudes. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 49(1), 69–96. doi:10.1111/joca.12058.

Berti, A. E., & Bombi, A. S. (1988). The child’s construction of economics. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Berti, A. E., & Grivet, A. (1990). The development of economic reasoning in children from 8 to 13 years old: Price mechanism. Contributi de Psicologia, 3, 37–47.

Beutler, I. F., & Dickson, L. (2008). Consumer economic socialization. In J. J. Xiao (Ed.), Handbook of consumer finance research (pp. 83–102). New York: Springer.

Bogenschneider, K., & Corbett, T. (2004). Building enduring family policies in the 21st century: The past as prologue? In M. Coleman & L. H. Ganong (Eds.), Handbook of contemporary families: Considering the past, contemplating the future (pp. 451–468). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Chowa, G. A., & Despard, M. R. (2014). The Influence of parental financial socialization on youth’s financial behavior: Evidence from Ghana. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 35(3), 376–389. doi:10.1007/s10834-013-9377-9.

Clarke, M. C., Heaton, M. B., Israelson, C. L., & Egett, D. L. (2005). The acquisition of family financial roles and responsibilities. Family and Consumer Science Research Journal, 33(4), 321–340. doi:10.1177/1077727x04274117.

Danes, S. M. (1994). Parental perceptions of children’s financial socialization. Financial Counseling and Planning, 5, 127–149.

Danes, S. M., & Brewton, K. E. (2014). The role of learning context in high school students’ financial knowledge and behavior acquisition. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 35(1), 81–94. doi:10.1007/s10834-013-9351-6.

Danes, S. M., & Yang, Y. (2014). Assessment of the use of theories within the Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning and the contribution of the family financial socialization conceptual model. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 25(1), 53–68.

Dew, J. P. (2008). Marriage and finances. In J. J. Xiao (Ed.), Handbook of consumer finance research (pp. 337–350). New York: Springer.

Dew, J. P. (2016). Revisiting financial issues and marriage. In J. J. Xiao (Ed.), Handbook of consumer finance research (2nd ed.). New York: Springer.

Drever, A. I., Odders‐White, E., Kalish, C. W., Else‐Quest, N. M., Hoagland, E. M., & Nelms, E. N. (2015). Foundations of financial well‐being: Insights into the role of executive function, financial socialization, and experience‐based learning in childhood and youth. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 49(1), 13–38. doi:10.1111/joca.12068.

Fernandes, D., Lynch, J. G., Jr., & Netemeyer, R. G. (2014). Financial literacy, financial education, and downstream financial behaviors. Management Science, 60(8), 1861–1883. doi:10.1287/mnsc.2013.1849.

Fox, J., Bartholomae, S., & Lee, J. (2005). Building the case for financial education. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 39(1), 195–214. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6606.2005.00009.x.

Furnham, A. (1996). The economic socialization of children. In P. Lunt & A. Furnham (Eds.), Economic socialization: The economic beliefs and behaviors of young people (pp. 11–34). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Garrison, S. T., & Gutter, M. (2010). Gender differences in financial socialization and willingness to take financial risks. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 21(2), 60–72.

Grusec, J. E. (2011). Socialization processes in the family: Social and emotional development. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 243–269. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131650.

Grusec, J. E., & Davidov, M. (2010). Integrating different perspectives on socialization theory and research: A domain‐specific approach. Child Development, 81(3), 687–709. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01426.x.

Grusec, J. E., & Hastings, P. D. (2015). Preface. In J. E. Grusec & P. D. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of socialization: Theory and research (pp. 11–12). New York: Guilford Press.

Gudmunson, C. G., & Beutler, I. F. (2012). Relation of parental caring to conspicuous consumption attitudes in adolescents. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 33(4), 389–399. doi:10.1007/s10834-012-9282-7.

Gudmunson, C. G., & Danes, S. M. (2011). Family financial socialization: Theory and critical review. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(4), 644–667. doi:10.1007/s10834-011-9275-y.

Hastings, J. S., Madrian, B. C., & Skimmyhorn, W. L. (2013). Financial literacy, financial education, and economic outcomes. Annual Review of Economics, 5, 347–373. doi:10.1146/annurev-economics-082312-125807.

Hathaway, I., & Khatiwada, S. (2008). Do financial education programs work? Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Working Paper No. 08-03. Retrieved from http://www.clevelant.org/research/workingpaper/2008/wp0803.pdf

John, D. R. (1999). Consumer socialization of children: A retrospective look at twenty-five years of research. The Journal of Consumer Research, 26(3), 183–213. doi:10.1086/209559.

Jorgensen, B. L., & Savla, J. (2010). Financial literacy of young adults: The importance of parental socialization. Family Relations, 59(4), 465–478. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00616.x.

Karimli, L., Ssewamala, F. M., Neilands, T. B., & McKay, M. M. (2015). Matched child savings accounts in low-resource communities: Who saves? Global Social Welfare, 2(2), 53–64. doi:10.1007/s40609-015-0026-0.

Kim, C., Lee, H., & Tomiuk, M. A. (2009). Adolescents’ perceptions of family communication patterns and some aspects of their consumer socialization. Psychology & Marketing, 26(10), 888–907. doi:10.1002/mar.20304.

Kim, J., & Chatterjee, S. (2013). Childhood financial socialization and young adults’ financial management. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 24(1), 61–79.

Kim, J., Gale, J., Goetz, J., & Bermudez, J. M. (2011). Relational financial therapy: An innovative and collaborative treatment approach. Contemporary Family Therapy, 33, 229–241.

Kim, J., LaTaillade, J., & Kim, H. (2011). Family processes and adolescents’ financial behaviors. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(4), 668–679. doi:10.1007/s10834-011-9270-3.

Kuczynski, L., Parking, C. M., & Pitman, R. (2015). Socialization as dynamic process: A dialectical, transactional perspective. In J. E. Grusec & P. D. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of socialization: Theory and research (pp. 135–157). New York: Guilford Press.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), 5–44. doi:10.1257/jel.52.1.5.

Lusardi, A., Mitchell, O. S., & Curto, V. (2010). Financial literacy among the young. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 44(2), 358–380. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6606.2010.01173.x.

Mandell, L. (2009). Financial education in high school. In A. Lusardi (Ed.), Overcoming the saving slump: How to increase the effectiveness of financial education and savings programs (pp. 257–279). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

McCormick, M. H. (2009). The effectiveness of youth financial education: A review of the literature. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 20(1), 70–83.

Miller, M., Reichelstein, J., Salas, C., & Zia, B. (2014). Can you help someone become financially capable: A meta-analysis of the literature (Working Paper No. 6745). The World Bank.

Moschis, G. P. (1985). The role of family communication in consumer socialization of children and adolescents. The Journal of Consumer Science Research, 11(4), 80–92. doi:10.1086/209025.

Moschis, G. P., & Churchill, G. A., Jr. (1978). Consumer socialization: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Journal of Marketing Research, 15(4), 599–609. doi:10.2307/3150629.

Moschis, G. P. (1987). Consumer socialization: A life-cycle perspective. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Peng, T. M., Bartholomae, S., Fox, J. J., & Cravener, G. (2007). The impact of personal finance education delivered in high school and college courses. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 28(2), 265–284. doi:10.1007/s10834-007-9058-7.

Romo, L. K. (2011). Money talks: Revealing and concealing financial information in families. Journal of Family Communication, 11(4), 264–281. doi:10.1080/15267431.2010.544634.

Romo, L. K. (2014). Much ado about money: Parent-child perceptions of financial disclosure. Communication Reports, 27(2), 91–101. doi:10.1080/08934215.2013.859283.

Serido, J., & Deenanath, V. (2016). Chapter 24: Financial parenting: Promoting financial self-reliance of young consumers. In J. J. Xiao (Ed.), Handbook of consumer finance research (2nd ed.). New York: Springer.

Sherraden, M.S. (2010). Financial capability: What is it, and how can it be created? CSD Working Papers No. 10-17. St. Louis, MO.

Sherraden, M. S. (2013). Building blocks of financial capability. In J. Birkenmaier, M. Sherraden, & J. Curley (Eds.), Financial capability and asset development: Research, education, policy, and practice (pp. 3–43). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Shim, S., Barber, B. L., Card, N. A., Xiao, J. J., & Serido, J. (2010). Financial socialization of first-year college students: The roles of parents, work, and education. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(12), 1457–1470. doi:10.1007/s10964-009-9432-x.

Shim, S., Serido, J., Tang, C., & Card, N. (2015). Socialization processes and pathways to healthy financial development for emerging young adults. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 38, 29–38. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2015.01.002.

Shim, S., Xiao, J. J., Barber, B. L., & Lyons, A. C. (2009). Pathways to life success: A conceptual model of financial well-being for young adults. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30(6), 708–723. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2009.02.003.

Smetana, J. G., Robinson, J., & Rote, W. M. (2015). Socialization in adolescence. In J. E. Grusec & P. D. Hastings (Eds.), Handbook of socialization: Theory and research (pp. 60–84). New York: Guilford Press.

Sohn, S. H., Joo, S. H., Grable, J. E., Lee, S., & Kim, M. (2012). Adolescents’ financial literacy: The role of financial socialization agents, financial experiences, and money attitudes in shaping financial literacy among South Korean youth. Journal of Adolescence, 35(4), 969–980. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.02.002.

Stacey, B. G. (1987). Economic socialization. Annual Review of Political Science, 2, 1–33.

Stafford, E. F., Kasulis, J. J., & Lusch, R. F. (1982). Consumer behavior in accumulating household financial assets. Journal of Business Research, 10(4), 397–417. doi:10.1016/0148-2963(82)90001-7.

Tang, N., Baker, A., & Peter, P. C. (2015). Investigating the disconnect between financial knowledge and behavior: The role of parental influence and psychological characteristics in responsible financial behaviors among young adults. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 49(2), 376–406. doi:10.1111/joca.12069.

Van Campenhout, G. (2015). Revaluing the role of parents as financial socialization agents in youth financial literacy programs. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 49(1), 186–222. doi:10.1111/joca.12064.

Ward, S. (1974). Consumer socialization. The Journal of Consumer Research, 1(2), 1–14. doi:10.1086/208584.

Webley, P. (1996). Playing the market: The autonomous economic world of children. In P. Lunt & A. Furnham (Eds.), Economic socialization: The economic beliefs and behaviors of young people (pp. 149–161). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Webley, P. (2005). Children’s understanding of economics. In M. Barrett & E. Buchanan-Barrow (Eds.), Children’s understanding of society (pp. 43–67). New York: Psychology Press.

Wheeler-Brooks, J., & Scanlon, E. (2009). Perceived facilitators and barriers to saving among low-income youth. The Journal of Socioeconomics, 38(5), 757–763. doi:10.1016/j.socec.2009.03.015.

Xiao, J. J. (2015). Consumer economic wellbeing. New York: Springer.

Xiao, J. J., Ahn, S., Serido, J., & Shim, S. (2014). Earlier financial literacy and later financial behavior of college students. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 38(6), 593–601. doi:10.1111/ijcs.12122.

Xiao, J. J., Chatterjee, S., & Kim, J. (2014). Factors associated with financial independence of young adults. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 38, 394–403. doi:10.1111/ijcs.12106.

Xiao, J. J., Chen, C., & Chen, F. (2014). Consumer financial capability and financial satisfaction. Social Indicators Research, 118(1), 415–432. doi:10.1007/s11205-013-0414-8.

Xiao, J. J., Ford, M. W., & Kim, J. (2011). Consumer financial behavior: An interdisciplinary review of selected theories and research. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 39(4), 399–414. doi:10.1111/j.1552-3934.2011.02078.x.

Xiao, J. J., & O’Neill, B. (2014). Financial education and financial capability. In V. J. Mason (Ed.), Proceedings of the Association for Financial Counseling and Planning Education (pp. 58–68).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Gudmunson, C.G., Ray, S.K., Xiao, J.J. (2016). Financial Socialization. In: Xiao, J. (eds) Handbook of Consumer Finance Research. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28887-1_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28887-1_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-28885-7

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-28887-1

eBook Packages: Behavioral Science and PsychologyBehavioral Science and Psychology (R0)