Abstract

Parental burnout is a condition resulting from chronic stress related to one’s parental role. Based on current research advances, family functioning forms a crucial part of the antecedents that influence parental burnout. However, there is a paucity of literature on the mechanisms by which family functioning affects parental burnout and how the factors in family functioning interact and influence each other. The present study aimed to explore the potential indirect association between marital satisfaction and parental burnout through the mediating role of parents’ coparenting support. Furthermore, the study examined whether grandparents’ coparenting played a moderating role in the relationship between parents’ coparenting support and parental burnout. A total of 673 parents of preschool children completed questionnaires assessing marital satisfaction, parental burnout, and the quality of both parents’ and grandparents’ coparenting relationships. The results revealed that marital satisfaction was indirectly associated with parental burnout through parents’ coparenting support. Additionally, parents’ coparenting support interacted with grandparents’ coparenting conflicts in influencing parental burnout. This study highlights the significance of high satisfaction marriage relationships in alleviating parental burnout through parents’ coparenting support. Moreover, it underscores the importance of both parents’ and grandparents’ coparenting relationships in parental adjustment. These findings emphasize the role of coparenting in understanding parental burnout and suggest the potential application of family systems theory and risks and resources theory to explain and predict the effects of family functioning on parental burnout.

Highlights

-

This study examines how marital satisfaction, coparenting between parents and grandparents, and parental burnout are interconnected.

-

High marital satisfaction alleviates parental burnout through parents’ coparenting support.

-

A higher level of grandparents’ coparenting conflict strengthens the buffering effect of strong parents’ coparenting support against parental burnout.

-

An integrated model is introduced, combining family function, family system, and risks and resources theories, to explain the occurrence of parental burnout.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Raising a child is a challenging responsibility. Despite the outward appearance of a harmonious and content family, parents must undertake the intricate task of parenting and fulfill their role as caregivers. They need to plan carefully, assess risks, and monitor constantly, and may even face accusations from grandparents about their parenting style and doubts about their parental effectiveness (Kelly & Senior, 2021). These unpaid, repetitive and consuming tasks can be very stressful for parents, and when they are faced with such high levels of chronic stress, they are likely to develop parental burnout (PB). Parental burnout has been defined as a state in which parents feel exhausted by their parental role, have a low sense of competence and accomplishment, and show a lack of emotional bonding with their children (Roskam et al., 2017). It may also increase avoidance and suicidal thoughts (Mikolajczak et al., 2021) and negatively affect parenting behaviors themselves, leading to internalizing and externalizing behavioral problems in children (Chen et al., 2022) and even affecting their mental health (Yang et al., 2021). Against this background, it is necessary to explore the factors that may influence parental burnout. Previous studies have investigated the roles of some family functioning factors (e.g., lack support from extended family and coparenting) on parental burnout (Favez et al., 2023; Lebert-Charron et al., 2021; Mikkonen et al., 2022; Mikolajczak et al., 2018). However, the underlying mechanism behind the increased risk of parental burnout and family functioning factors is not well established. More than that, whether factors of different family functioning within a family interact and collectively contribute to parental burnout deserves further investigation. Family systems theory’s focus on interdependence and multilevel influences from subsystems within the family makes it a useful theoretical tool for understanding how family functioning contributes to parental burnout.

According to family systems theory, family members are interdependent and influence each other, each as a subsystem within a larger family system (Cox & Paley, 2003). Especially it is necessary to consider the transactional effect of multiple family members (children, grandparents, and parents themselves) on parental burnout. The family systems theory provides a valuable conceptual framework for understanding how family sub-systems may influence parenting-relevant outcomes including parental burnout (Kerig, 2019). As the family system theory indicated: patterns of functioning within one family subsystem are related in systematic ways to functioning within other subsystems (Cox & Paley, 2003). The subsystems we specifically examined in the present study were marital relationships, parents’ coparenting, and grandparents’ coparenting. Within this framework of the family system theory, this study is trying to explore the mechanism by which family functioning influence parental burnout. The following sections introduces key constructs in our research, along with the proposed relationships among them.

Parental Burnout

Parental burnout is one of the indicators of parental mental health (Mikolajczak et al., 2019). Parental burnout occurs when parents are chronically exposed to an imbalance between parental stress-enhancing risk factors and stress-alleviating coping resources (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018). Several studies have used the balance between risk and resources theory to examine the various types of factors that influence parental burnout. In terms of risk factors, parental psychological characteristics such as perfectionism (Raudasoja et al., 2023), a lack of effective emotional management skills (Le Vigouroux et al., 2017; Lin & Szczygieł, 2022), and children’s special needs (Gérain & Zech, 2018) can lead to greater parental burnout. In terms of coping resources, protection factors such as positive relationships and social network support (Lebert-Charron et al., 2021; Mikolajczak et al., 2018) can play a significant role in mitigating parental burnout. For the present study, we integrated the balance between risks and resources theory with the family systems theory to explore how different family sub-system risks and resources within the family may interactively influence parental burnout in the Chinese context.

Marital Satisfaction and Parental Burnout

Marital satisfaction refers to an individual’s level of satisfaction within their marital relationship (Chen & Zhou, 2019). It is closely related to family functioning and child development, significantly impacting individual and family happiness and stability (Chen & Zhou, 2019; Carr & Springer, 2010). Also, marital satisfaction is a key psychological measure that assesses the quality of the marital relationship (Lavner et al., 2017).

The significance of marital relationship extends beyond family theory and encompasses the realm of couples’ psychological well-being. Longitudinal studies have shown that a high-quality marital relationship positively affects parental mental health (Kiecolt-Glaser & Wilson, 2017; Sejourne et al., 2018), while a low quality of marital relationship is associated with serious psychological problems later in life. (Goldfarb & Trudel, 2019).

Within the family context, the relationship between marital relationships and parenting behaviors is of particular interest. Given the substantial impact of marital relationships on parents’ psychological well-being, it is likely that they also significantly influence parenting burnout (Parkes et al., 2019). Parents experience significant stress during the parenting process, and an unhealthy marital relationship not only fails to provide a buffer for these stresses but may also result in mutual hindrance, making it challenging to address parenting challenges. This can lead to increased arguments and potentially result in parental burnout (Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018).

Therefore, exploring the potential relationship between marital satisfaction as a marital relationship indicator and parental burnout as a parenting-related indicator is a logical research direction. Several studies have examined the relationship between marital satisfaction and parental burnout, finding a negative association (Mikolajczak et al., 2018; Mousavi, 2020; Naeem et al., 2023).

However, further investigation is needed to understand the mechanisms involved and whether other variables influence this relationship. In the present study, we propose a moderated mediation model involving parents and grandparents’ coparenting. The following sections will provide specific introductions to these concepts.

The Mediating Role of Parents’ Coparenting

In recent years, family systems research has come to stress the importance of parents’ coparenting (Belsky et al., 1995; Chen, 2019; Kolak & Volling, 2013). This is a particular form of social support that emerges when couples become parents. It refers to the way parents work together in raising their children (Feinberg, 2003). One of the main conceptual differentiations between parents’ coparenting and marital relationships is that partners adopt a supportive coparenting relationship to promote the wellbeing of their child, whereas they adopt a satisfactory marital relationship to promote the welfare of themselves (Margolin et al., 2001). Parents’ coparenting, which may be considered as a potential mediator between marital satisfaction and parental burnout, has been under-researched. A few published studies have shown bivariate associations between marital satisfaction and parents’ coparenting and between parents’ coparenting and parental burnout. It has been suggested that marital satisfaction is associated with parents’ coparenting (Le et al., 2016; Pedro et al., 2012; Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2004). This means that partners have positive marital relationships with each other, which motivates them to support each other as parents and cooperate in caring for their children. Parents’ supportive coparenting, meanwhile, may alleviate parental burnout. Research has suggested that parents’ coparenting has an impact on parental role adaptation and the ability to rear children (Feinberg et al., 2007; McHale et al., 2002). Recent research has shown that parents’ supportive coparenting was negatively associated with parental burnout (Favez et al., 2023; Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018).

Although researchers have yet to examine whether parents’ coparenting might be a mediator linking marital satisfaction and parental burnout, some (Margolin et al., 2001; Pedro et al., 2012) have proposed that coparenting might mediate the relationship between marital conflict and parenting/parental adjustment. For example, Pedro et al. (2012) showed that coparenting behavior mediated the association between spousal marital satisfaction and partners’ parenting practices. The present study proposed that a positive marital relationship may provide the foundation of a supportive inter-parental alliance in child care (i.e., supportive coparenting), which may in turn promote parental adjustment (e.g., a decrease in the risk of parental burnout). Therefore, it predicted that marital satisfaction would be indirectly associated with parental burnout through the mediating role of parents’ coparenting.

The Moderating Role of Grandparents’ Coparenting

In some societies (e.g., China), grandparents are highly involved in child care (Zou et al., 2020). The role played by the grandparent-parent subsystem within a family system cannot be ignored. The coparenting-relevant theory emphasizes collaborative coparenting in which two or more other adult caregivers share parenting responsibilities (McHale et al., 2004). The cooperation (or lack thereof) of different adult caregivers in the co-parenting process can have powerful and far-reaching effects within the family system. Supportive and non-supportive coparenting relationships between grandparents and parents are commonplace in China (Goh & Kuczynski, 2010). Therefore, grandparents’ involvement in parenting may be a double-edged sword. That is, supportive coparenting by grandparents may provide parenting resources whereas non-supportive coparenting by grandparents may cause parenting stress. For example, research has shown that supportive coparenting by grandparents may enhance maternal parenting self-efficacy (Li & Liu, 2019) and reduce parental burnout (Mikolajczak et al., 2018). According to Belsky’s (1984) determinants of parenting model and the existing literature on coparenting (Chen, 2020), supportive grandparents’ coparenting, which can be seen as a beneficial social resource, may help parents cope effectively with parenting stress, whereas non-supportive grandparents’ coparenting—which may be a risk factor—can exacerbate difficulties in coping with the parenting stress. Thus, grandparents’ coparenting may act as a moderator.

The Present Study

The present study used moderated mediation analysis to explore the indirect role of marital satisfaction on parental burnout through parents’ coparenting and the potential moderator of grandparents’ coparenting in the Chinese context (Fig. 1), with a focus on the population of Chinese families. In modern Chinese families, the shared childcare responsibilities between parents and grandparents are increasingly prevalent (Settles et al., 2009), driven by socio-economic changes and policy shifts such as the growing number of dual-income households and the three-child policy. This has resulted in larger families with intensified parenting demands, positioning grandparents as key support figures. Unlike Western societies, where grandparental involvement is more common in single-parent or divorced families, in China, it is deeply rooted in Confucian principles that emphasize family unity and collaborative child-rearing, making it prevalent in intact families (Wang et al., 2022). Through this lens, the study aims to apply and observe the effects of Family Functioning Theory and Family Systems Theory in understanding the determinants of parental burnout within the rich, culturally specific backdrop of Chinese society. Although previous studies based on Chinese samples have shown that parental burnout may influence children’s adjustment (Chen et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2021), there is little empirical literature on how different family factors influence parental burnout. In addition, very little practical information is available for Chinese parents to help them reduce parental burnout. The present study was designed to remedy this situation by conducting the first study on the associations between Chinese parents’ marital satisfaction, parents’ and grandparents’ coparenting, and parental burnout within a framework integrating the family systems theory and the balance between risks and resources theory (Fig. 1). We hypothesized that marital satisfaction would be negatively associated with parental burnout and indirectly associated with parental burnout through the mediating role of parents’ coparenting, and that grandparents’ coparenting would moderate the above mediation model, thereby attenuating or exacerbating the link between parents’ coparenting and parental burnout.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Parents of preschool children in Shanghai were recruited to participate in the survey. A total of 673 parents (305 fathers [45.3%] and 368 mothers [54.7%]) took part. There were 359 boys (53.3%) and 314 girls (46.7%) amongst the families surveyed. The average education level of the parents was 15.6 years (SD = 2.62); the average parental age was 33.90 years (SD = 3.96); and the average length of marriage was 6.85 years (SD = 3.44). No missing data were observed in our study. All participants completed the measures in their entirety, and there were no instances of incomplete or missing responses. Also, there were no outliers. Therefore, there was no need for imputation or any specific handling of missing data in our analyses. The absence of missing data ensures the robustness of our findings and the reliability of the reported results.

The study was approved by the institutional ethical review committee. The data were collected using an online questionnaire. The parents were given a link to this after they had provided electronic informed consent to their participation.

Measures

Marital Satisfaction

The Chinese version (Chen & Zhou, 2019) of the Kansas Marital Satisfaction Scale (Schumm et al., 1983) was used to assess the parents’ satisfaction with their marital relationship. The scale contains three items (e.g., “How satisfied are you with your marriage?”). It is rated on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (extremely dissatisfied) to 7 (extremely satisfied), with higher scores indicating greater marital satisfaction. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.98.

Parents’ Coparenting Support

The Chinese version (Chen, 2019, 2020) of the Coparenting Relationship Scale was used to assess the parents’ coparenting support. Specifically, it assessed the parents’ perceptions of the quality of co-parenting behaviors. The scale consists of 14 items (e.g., “My partner backs me up when I discipline our child”). It was rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Items describing non-supportive behavior were reverse-scored; the average score was then used as a composite score. High scores indicated higher levels of coparenting support. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.71.

Parental Burnout

The Chinese version (Chen et al., 2022) of the Parental Burnout Assessment (Roskam et al., 2018) was used to assess parental burnout. The scale consists of 23 items (e.g., “I feel completely run down by my role as a parent”). Parents responded on a 7-point scale, ranging from 0 (never) to 6 (every day). The sum score of all 23 items ranges from 0 to 138. The item scores were averaged to form a composite score; the higher the score, the higher the level of parental burnout. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.98.

Grandparents’ Coparenting

The Coparenting Relationship Scale (Stright & Bales, 2003) was adapted to assess parents’ perceptions of the quality of grandparents’ coparenting behaviors. The scale consists of 14 items originally designed to measure coparenting between partners. However, for our study, we replaced the term “My partner” with “My child’s grandparent” to measure the coparenting relationship between parents and grandparents. Parents completed the questionnaire, considering the grandparent who was most involved in their child’s care.

To evaluate the level of grandparents’ coparenting involvement, we employed specific screening questions. Participants were asked about the grandparents’ assistance in childcare over the past year, the estimated amount of time spent caring for the child each week, and the division of caregiving responsibilities between them. These prescreening measures ensured that our sample primarily consisted of grandparents actively engaged in childcare. This is particularly important given the prevalence of grandparental involvement in childcare within Chinese culture (Hong et al., 2022), validating the representativeness of our sample selection criteria.

The items on the scale were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The scale includes two subscales, each comprising seven items. The first subscale assesses grandparents’ supportive coparenting (e.g., “My child’s grandparent backs me up when I discipline them”), while the second subscale measures grandparents’ non-supportive coparenting (e.g., “My child’s grandparent criticizes my parenting in front of them”). Composite scores were calculated by averaging the item scores for each subscale. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were calculated to assess internal consistency, yielding a value of 0.92 for the support subscale and 0.88 for the conflict subscale.

Data Analytic Plan

IBM SPSS 26 was used for both the preliminary and primary data analyses. The preliminary phase included calculating descriptive statistics such as means, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis, as well as performing correlation analyses for all variables. The detailed results are presented in Table 1. Tests for Common Method Bias and gender differences in parental burnout were also conducted. Given that the study relied on self-report questionnaires for all variables, Harman’s single-factor analysis (Podsakoff et al., 2012) was conducted to assess potential Common Method Bias. This test determines if a single factor accounts for most of the data variance. Additionally, considering the significant gender differences in burnout highlighted in previous research (Roskam & Mikolajczak, 2020), we investigated the potential impact of gender on our study variable, parental burnout, and our overall models.

Following the preliminary analysis, which included computing descriptive statistics and correlations, testing for Common Method Bias, and examining gender differences in parental burnout, we proceeded to the primary analysis using Hayes’ PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013). In the primary analysis, we first tested a simple mediation model (Model 4 within the PROCESS Macro) to explore the indirect relationship between marital satisfaction and parental burnout via the mediating effect of parents’ coparenting. Additionally, we examined a moderated mediation model (Model 14 within the PROCESS Macro) to assess the moderating effect of grandparents’ coparenting on the link between parents’ coparenting (as the mediator) and parental burnout. Initially, control variables including parents’ age, educational level, and length of marriage were included in Model 4. However, none of these variables significantly influenced parents’ coparenting (parents’ age: b = −0.01, p = 0.057; educational level: b = 0.01, p = 0.061; length of marriage: b = 0.003, p = 0.621) or parental burnout (parents’ age: b = −0.29, p = 0.197; educational level: b = −0.25, p =0.417; length of marriage: b = 0.37, p = 0.147). Consequently, these variables were excluded from the final models. In the subsequent stage of analysis, only our study variables - marital satisfaction, parents’ coparenting, grandparents’ coparenting, and parental burnout - were incorporated into the final models (Models 4 and 14). We employed a bootstrapping method with 10,000 samples to calculate point estimates of conditional indirect effects, direct effects, and the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for these effects. This approach was taken to control for Type I error and address issues related to the asymmetric and non-normal distribution of indirect effects. An effect was deemed statistically significant if the CIs did not contain zero. The moderators, namely grandparents’ coparenting support and conflict, were analyzed separately within these models.

Results

Preliminary Data Analyses

Descriptive Analyses

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations among the studied variables. Higher marital satisfaction was linked to significantly less parental burnout, showing a negative correlation. Also, it correlated positively with higher levels of parents’ coparenting support and grandparents’ coparenting support. Conversely, marital satisfaction was inversely related to grandparents’ coparenting conflict, with a higher satisfaction corresponding to less conflict. Parental burnout showed a significant negative correlation with parents’ coparenting support and grandparents’ coparenting support. In contrast, parental burnout was positively correlated with grandparents’ coparenting conflict, suggesting that higher burnout is associated with more conflict.

The Test for Common Method Bias

All the variables were assessed by self-report questionnaires, which may have caused common method bias. To determine the potential impact of this on the results, we conducted a Harman’s single-factor analysis to test whether a single factor can explain all of the variance (Podsakoff et al., 2012). It showed that there were 9 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, among which the variation explained by the first factor was only 33.54%, less than the critical standard of 50%. Thus, the common method bias does not appear to be an issue in this study (Podsakoff et al., 2012).

Gender Differences in Parental Burnout

An independent samples t test was employed to examine gender differences in parental burnout. The results, showing t(671) = −0.23, p = 0.819, revealed no significant differences based on gender, leading us to omit this factor from our final models.

Primary Data Analyses

As can be seen from the simple mediation model in Table 2, marital satisfaction was directly associated with parental burnout. The first hypothesis was supported. In addition, marital satisfaction was positively associated with parents’ coparenting support, and parents’ coparenting support was negatively associated with parental burnout. Bootstrapping with 10,000 samples showed that the mediating role of parents’ coparenting support in the relationship between marital satisfaction and parental burnout was significant. The second hypothesis was supported.

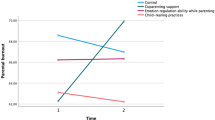

As shown in the higher portion of Table 3, the interaction of parents’ coparenting support and grandparents’ coparenting support was not significant. However, as the lower portion of Table 3 shows, the interaction of parents’ coparenting support and grandparents’ coparenting conflict was significant. This indicated that the link between parents’ coparenting support and parental burnout was moderated by grandparents’ coparenting conflict. Simple effects were estimated from separate regression equations predicting parental burnout from parents’ coparenting support at low and high levels of grandparents’ coparenting conflict. Parents’ coparenting support was negatively associated with parental burnout at low levels of grandparents’ coparenting conflict, and this association was stronger at high levels of grandparents’ coparenting conflict (Fig. 2).

Discussion

This study significantly advances our understanding of parental burnout, a condition stemming from emotional exhaustion caused by a chronic imbalance between stress-enhancing risk factors and stress-alleviating resources. Our research offers new insights into the precursors of parental burnout, especially in unraveling the complex interactions among these factors. In a field where understanding the causes and interconnections leading to parental burnout is still developing (Mikolajczak et al., 2018), our study introduces a novel approach to analyzing the cumulative effects of multiple antecedents on parental burnout. Specifically, our results reveal an indirect link between marital satisfaction and parental burnout, mediated by the support from partner coparenting. Importantly, the study shows how conflicts in grandparent-parent coparenting can moderate the impact of this support on parental burnout, indicating that both partners and grandparents are crucial in coparenting and significantly influence the reduction of parental burnout. These findings on the mediating and moderating roles of coparenting provide valuable strategies for interventions to reduce parental burnout.

Additionally, the study integrates Family Functioning Theory, Resource and Risk Theory, and Family Systems Theory, proposing a new model to explain parental burnout. This new model focuses on providing an explanatory framework for parental burnout, considering the complex influences from various factors, particularly within the family context. In this model, the Family Functioning Theory serves as a framework to identify the various factors that contribute to parental burnout, similar to how it explains the composition of specific molecules by examining their atomic components. However, the Family Functioning Theory does not provide a dynamic mechanism for understanding the interactions among these factors that collectively lead to parental burnout.

In this regard, the Resource and Risk Theory offers a comprehensive understanding of this dynamic process. It functions like a balance scale, with protective factors on one end and sources of stress on the other. As the sources of stress outweigh the protective factors, the likelihood of parental burnout increases. Thus, the Resource and Risk Theory provides a dynamic mechanism that integrates the various factors influencing parental burnout. In this analogy, it resembles the theory of chemical bonds, explaining how the atoms within the molecule of parental burnout are combined.

Expanding the perspective beyond the couple and nuclear family, the Family Systems Theory incorporates the role of grandparents, enriching the explanatory framework. The Family Systems Theory views family members as interdependent microsystems that directly and indirectly influence each other and other subsystems. It emphasizes that microsystems are embedded within larger systems and highlights the interactions occurring within and between these different levels. This perspective treats grandparents and parents as a microsystem, providing a theoretical framework for understanding the observed moderation and mediation effects. To illustrate, the Family Systems Theory goes beyond examining the relationships among individual atoms (factors within the family influencing parental burnout) and explores the relationships among molecules and molecules (how different microsystems affect, enhance, weaken, or disrupt chemical bonds).

There was a significant negative association between marital satisfaction and parental burnout. This accorded with the previous literature (Mikolajczak et al., 2018). From a family systems theory perspective, the father-mother subsystem influenced the parent-child subsystem, suggesting that there was a strong association between the quality of marital relationships and parental burnout arising from the process of caring for children. Consistent with the balance between risks and resources theory, a high quality of marital relationship provided the parents with more supportive resources to help them face the responsibilities and stresses of parenting. Because marital satisfaction reflects the quality of the marital relationship from a subjective and internal perspective, it is more likely to represent an individual’s internal state; this may have a crossover effect on psychological burnout, which is also considered to be an internal mental state.

Parents’ coparenting support mediated the associations between marital satisfaction and parental burnout. The mediating effect of parents’ coparenting support can be seen as a suppressing effect (Wen & Ye, 2014) because high marital satisfaction reduces parental burnout by increasing the level of parents’ coparenting support. The quality of the spousal relationship in both coparenting and marital relationships may play an important role in mitigating parental burnout. In particular, parents’ coparenting support has important implications for parenting and family role distinctions in childcare. Parents often play different roles and face substantial work-family conflicts (Van Bakel et al., 2018). Therefore, a cooperative division in family roles and partners’ parenting support is important. To prevent parental burnout, couples should coparent when caring for their children and support each other when they encounter parental stress.

Besides, based on the findings depicted in Fig. 2, it was observed that families characterized by high levels of grandparents’ coparenting conflict exhibited elevated levels of parental burnout compared to families with low levels of coparenting conflict. This outcome aligns with the spill-over hypothesis proposed within the framework of family systems theory, which posits that emotions and behaviors originating in one subsystem can overflow into another subsystem (Erel & Burman, 1995; Krishnakumar & Buehler, 2000). Specifically, the conflict experienced in the grandparent-parent subsystem may extend into the parent-child subsystem, ultimately contributing to a higher average level of parental burnout. Studies examining parent-grandparent coparenting dynamics have provided supportive evidence in this regard. For instance, Goh and Kuczynski (2010) found that mutual competition between mothers and grandmothers can permeate into the mother-child relationship, leading to negative parenting behaviors and disruption of the mother-child bond.

The results revealed a significant moderation effect of grandparent-parent coparenting conflict on the relationship between parents’ coparenting support and parental burnout. Specifically, with a higher level of grandparent’s coparenting conflict, the negative association between parents’ coparenting support and parental burnout becomes more pronounced. Put simply, when there is higher conflict in grandparent coparenting, a greater level of parents’ coparenting support is associated with a more significant reduction in parental burnout. Essentially, the protective effect of parental support is amplified in the presence of high conflict in grandparents’ coparenting.

This moderation effect can potentially be explained by the influence of psychological reactance. The theory of psychological reactance suggests that individuals have an innate need for autonomy and the capacity to exert control over their lives. When they perceive external attempts to restrict or interfere with their autonomy, they experience a drive to restore the threatened freedom (Brehm, 1966). In China, there is often a significant disparity between the parenting experiences of the older generation (grandparents) and the younger generation (parents), resulting in serious conflicts in parental guidance from grandparents (referred to as the high grandparents’ coparenting conflict situation in Fig. 2) (Liang et al., 2021). These conflicts pose a threat to parents’ autonomy. Consequently, parents experience psychological reactance, which motivates them to restore their sense of freedom (Steindl et al., 2015). Furthermore, the psychological motivation driven by reactance to restore freedom compels individuals to actively seek social support as a means of alleviating the constraints they encounter. Consequently, social support assumes a critical role in facilitating the reevaluation of individuals’ circumstances and enhancing their emotional well-being (Steindl et al., 2015). Among various forms of social support, coparenting support from one’s partner holds paramount importance and is highly valued within the family context, given the shared age and mutual understanding of each other’s parenting styles (Liang et al., 2021). Thus, the protective effect of parents’ coparenting support (partner support) may be amplified in environments characterized by high levels of grandparents’ coparenting conflict (as illustrated by the observed moderation effect in Fig. 2).

Grandparent-parent coparenting support did not have a moderating effect. This may have been because partners’ coparenting support appeared to be stronger in alleviating parental burnout than grandparent-parenting coparenting support. Although both partners’ and grandparents’ co-parenting support can somewhat increase parents’ resourcefulness in caring for their children, spousal support provides more proximal and direct support for parents experiencing stress than grandparental support. Grandparent support is by its nature intergenerational (Goh & Kuczynski, 2010; Zou et al., 2020); intergenerational conflicts and contradictions in childcare may make intergenerational coparenting support less effective in reducing parental burnout.

Limitations and Future Directions

The present study has some limitations. First, given its cross-sectional design, it was not possible to determine causal links between the study variables. Future researchers might use a longitudinal design to provide evidence of the temporal ordering of the variables that were considered in the study. Second, the study used questionnaires to collect data on coparenting and the quality of marital relationships. Although the questionnaires employed are commonly used instruments with high reliability and validity, self-reporting inevitably causes some bias. Future studies should use methods such as family interaction observation (e.g., Schoppe-Sullivan et al., 2004) to assess the variables. Third, the present study focused on parents with preschool children. Although previous studies have shown that children’s age did not influence parental burnout (Le Vigouroux & Scola, 2018; Mikolajczak & Roskam, 2018), future researchers might be able to confirm whether the findings of the present study are generalizable to other age groups. Lastly, our research mainly involved Chinese parents from an urban setting in Shanghai, typically with higher educational levels. This specific demographic may limit the generalizability of our results. The experiences and parenting dynamics of our sample might not represent those in diverse cultural and regional backgrounds, particularly rural areas. Future studies should aim to replicate our research in diverse settings, encompassing various regions and incorporating families with different educational backgrounds and cultural experiences. This more inclusive approach will broaden the applicability of our findings and provide deeper insights into parental burnout in various contexts.

Conclusion

The present study offers valuable insights into the connection between marital relationships and parental burnout. It introduces a comprehensive model that integrates the family function theory, family system theory, and risk and resource theory, providing a framework for understanding parental burnout in the context of coparenting and marital satisfaction. By examining the complex interplay between coparenting dynamics, marital satisfaction, and parental well-being, the study uncovers the intricate nature of parental burnout. These research findings have meaningful implications for advancing our understanding of this phenomenon. Also, the research findings have important translational implications:

Firstly, recognizing the significant spill-over impact of grandparents’ coparenting conflict on parental well-being is crucial. The observed association between higher levels of grandparents’ coparenting conflict and greater parental burnout underscores the need for interventions and support systems aimed at reducing conflict and enhancing communication within the grandparent-parent subsystem. Prioritizing a rational division of family roles in childcare responsibilities can serve as one effective approach to reduce conflicts. By actively addressing these conflicts, professionals can effectively mitigate the stress experienced by parents, leading to notable improvements in their overall well-being.

Furthermore, the role of parents’ coparenting support plays a significant role in mitigating the detrimental impacts of parental burnout, particularly in the context of high grandparents’ coparenting conflict. This support demonstrates a robust and even amplified effect on reducing parental burnout. Additionally, our study’s meditation model suggests that parents’ coparenting support serves as a more specific and critical protective factor in alleviating parental burnout compared to high marital satisfaction alone. Given these findings, it is crucial for mental health professionals to prioritize their attention to parents’ coparenting support. They should also consider incorporating targeted behavioral therapy training and interventions that focus on enhancing coparenting support as effective strategies for alleviating parental burnout.

Overall, the translational implications of this research highlight the importance of addressing grandparents’ coparenting conflicts and promoting coparenting support from partners. By incorporating these insights into interventions and support programs, professionals can contribute to fostering healthier coparenting dynamics, improving parental well-being, and ultimately promoting positive developmental outcomes for children within the family system.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55, 83–96. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129836.

Belsky, J., Crnic, K., & Gable, S. (1995). The determinants of coparenting in families with toddler boys: Spousal differences and daily hassles. Child Development, 66, 629–642. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00894.x.

Brehm, J. W. (1966). A theory of psychological reactance. Academic Press.

Carr, D., & Springer, K. W. (2010). Advances in families and health research in the 21st Century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 743–761. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00728.x.

Chen, B.-B. (2019). Chinese adolescents’ sibling conflicts: Links with maternal involvement in sibling relationships and coparenting. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 29, 752–762. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12413.

Chen, B.-B. (2020). The relationship between Chinese mothers’ parenting stress and sibling relationships: A moderated mediation model of maternal warmth and co-parenting. Early Child Development and Care, 190, 1350–1358. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2018.1536048.

Chen, B.-B., Qu, Y., Yang, B., & Chen, X. (2022). Chinese mothers’ parental burnout and adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems: The mediating role of maternal hostility. Developmental Psychology, 58, 768–777. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001311.

Chen, B.-B., & Zhou, N. (2019). The weight status of only children in China: The role of marital satisfaction and maternal warmth. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 2754–2761.

Cox, M. J., & Paley, B. (2003). Understanding families as systems. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12, 193–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.01259.

Erel, O., & Burman, B. (1995). Interrelatedness of marital relations and parent-child relations: a meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 118, 108.

Favez, N., Max, A., Bader, M., & Tissot, H. (2023). When not teaming up puts parents at risk: Coparenting and parental burnout in dual-parent heterosexual families in Switzerland. Family Process, 62, 272–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12777.

Feinberg, M. E. (2003). The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parenting, 3, 95–131. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327922PAR0302_01.

Feinberg, M. E., Kan, M. L., & Hetherington, E. M. (2007). The longitudinal influence of coparenting conflict on parental negativity and adolescent maladjustment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 687–702. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00400.x.

Gérain, P., & Zech, E. (2018). Does informal caregiving lead to parental burnout? Comparing parents having (or not) children with mental and physical issues. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 884 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00884.

Goh, E. C. L., & Kuczynski, L. (2010). Only children’ and their coalition of parents: Considering grandparents and parents as joint caregivers in urban Xiamen, China. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 13, 221–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-839X.2010.01314.x.

Goldfarb, M. R., & Trudel, G. (2019). Marital quality and depression: A review. Marriage and Family Review, 55, 737–763. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2019.1610136.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Hong, X., Zhu, W., & Luo, L. (2022). Non-parental care arrangements, parenting stress, and demand for infant-toddler care in China: Evidence from a national survey. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 822104 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.822104.

Liang, X., Lin, Y., Van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Wang, Z. (2021). Grandmothers are part of the parenting network, too! A longitudinal study on coparenting, maternal sensitivity, child attachment and behavior problems in a Chinese sample. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2021, 95–116. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20442.

Kelly, S., & Senior, A. (2021). Towards a feminist parental ethics. Gender, Work & Organization, 28, 807–825. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12566.

Kerig, P. K 2019). Parenting and family systems. Handbook of parenting: Being and becoming a parent. 3rd ed. Vol. 3. 3–35). New York, NY: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., & Wilson, S. J. (2017). Lovesick: how couples’ relationships influence health. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 13, 421–443. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045111.

Kolak, A. M., & Volling, B. L. (2013). Coparenting moderates the association between firstborn children’s temperament and problem behavior across the transition to siblinghood. Journal of Family Psychology, 27, 355–364. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032864.

Krishnakumar, A., & Buehler, C. (2000). Interparental conflict and parenting behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Family Relations, 49, 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2000.00025.x.

Lavner, J. A., Karney, B. R., Williamson, H. C., & Bradbury, T. N. (2017). Bidirectional associations between newlyweds’ marital satisfaction and marital problems over time. Family Process, 56, 869–882. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12264.

Lebert-Charron, A., Wendland, J., Vivier-Prioul, S., Boujut, E., & Dorard, G. (2021). Does perceived partner support have an impact on mothers’ mental health and parental burnout? Marriage & Family Review, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2021.1986766

Ledermann, T., Bodenmann, G., Gagliardi, S., Charvoz, L., Verardi, S., Rossier, J., & Iafrate, R. (2010). Psychometrics of the Dyadic coping inventory in three language groups. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 69, 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185/a000024.

Le Vigouroux, S., Scola, C., Raes, M.-E., Mikolajczak, M., & Roskam, I. (2017). The big five personality traits and parental burnout: Protective and risk factors. Personality and Individual Differences, 119, 216–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.07.023.

Le Vigouroux, S., & Scola, C. (2018). Differences in parental burnout: Influence of demographic factors and personality of parents and children. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 887 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00887.

Le, Y., McDaniel, B. T., Leavitt, C. E., & Feinberg, M. E. (2016). Longitudinal associations between relationship quality and coparenting across the transition to parenthood: A dyadic perspective. Journal of Family Psychology, 30, 918–926. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000217.

Lin, G.-X., & Szczygieł, D. (2022). Perfectionistic parents are burnt out by hiding emotions from their children, but this effect is attenuated by emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 184, 111187 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111187.

Li, X., & Liu, Y. (2019). Parent-grandparent coparenting relationship, maternal parenting self-efficacy, and young children’s social competence in Chinese urban families. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 1145–1153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01346-3.

Margolin, G., Gordis, E. B., & John, R. S. (2001). Coparenting: A link between marital conflict and parenting in two-parent families. Journal of Family Psychology, 15, 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.15.1.3.

McHale, J. P, Khazan, I, Erera, P, Rotman, T, DeCourcey, W. & & McConnell, M. In: In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.) 2002). Coparenting in diverse family systems. Handbook of parenting. 2nd ed. Vol. 3. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

McHale, J. P., Kuersten-Hogan, R., & Rao, N. (2004). Growing points for coparenting theory and research. Journal of Adult Development, 11, 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JADE.0000035629.29960.ed.

Mikkonen, K., Veikkola, H.-R., Sorkkila, M., & Aunola, K. (2022). Parenting styles of Finnish parents and their associations with parental burnout. Current Psychology, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03223-7

Mikolajczak, M., Gross, J. J., & Roskam, I. (2019). Parental burnout: What is it, and why does it matter? Clinical Psychological Science, 7, 1319–1329. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702619858430.

Mikolajczak, M., Gross, J. J., & Roskam, I. (2021). Beyond job burnout: Parental burnout! Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 25, 333–336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.01.012.

Mikolajczak, M., Raes, M., Avalosse, H., & Roskam, I. (2018). Exhausted parents: Sociodemographic, child-related, parent-related, parenting and family-functioning correlates of parental burnout. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27, 602–614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0892-4.

Mikolajczak, M., & Roskam, I. (2018). A theoretical and clinical framework for parental burnout: The Balance Between Risks and Resources (BR2). Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 886 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00886.

Mousavi, S. F. (2020). Psychological well-being, marital satisfaction, and parental burnout in iranian parents: The effect of home quarantine during COVID-19 outbreaks. Frontiers in psychology, 11, 553880 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.553880.

Naeem, N., Sadia, R., Khan, S., & Fatima, Z. (2023). Parental burnout and marital satisfaction of married individuals during COVID-19: Role of gender and family system. Human Nature Journal of Social Sciences, 4, 151–160. http://hnpublisher.com/ojs/index.php/HNJSS/article/view/237.

Parkes, A., Green, M., & Mitchell, K. (2019). Coparenting and parenting pathways from the couple relationship to children’s behavior problems. Journal of Family Psychology, 33, 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000492.

Pedro, M. F., Ribeiro, T., & Shelton, K. H. (2012). Marital satisfaction and partners’ parenting practices: the mediating role of coparenting behavior. Journal of Family Psychology, 26, 509–522. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029121.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100452.

Raudasoja, M., Sorkkila, M., & Aunola, K. (2023). Self-esteem, socially prescribed perfectionism, and parental burnout. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 32, 1113–1120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02324-y.

Roskam, I., Brianda, M. E., & Mikolajczak, M. (2018). A step forward in the conceptualization and measurement of parental burnout: The Parental Burnout Assessment (PBA). Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 758 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00758.

Roskam, I., Raes, M., & Mikolajczak, M. (2017). Exhausted parents: Development and preliminary validation of the parental burnout inventory. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 163 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00163.

Roskam, I., & Mikolajczak, M. (2020). Gender differences in the nature, antecedents and consequences of parental burnout. Sex Roles, 83, 485–498. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01121-5.

Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., Mangelsdorf, S. C., Frosch, C. A., & McHale, J. L. (2004). Associations between coparenting and marital behavior from infancy to the preschool years. Journal of Family Psychology, 18, 194–207. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.194.

Schumm, W. R., Milliken, G. A., Poresky, R. H., Bollman, S. R., & Jurich, A. P. (1983). Issues in measuring marital satisfaction in survey research. International Journal of Sociology of the Family, 13, 129–143.

Settles, B. H., Zhao, J., Mancini, K. D., Rich, A., Pierre, S., & Oduor, A. (2009). Grandparents caring for their grandchildren: Emerging roles and exchanges in global perspectives. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 40, 827–848. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.40.5.827.

Sejourne, N., Sanchezrodriguez, R., Leboullenger, A., & Callahan, S. (2018). Maternal burn-out: An exploratory study. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 36, 276–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2018.1437896.

Steindl, C., Jonas, E., Sittenthaler, S., Traut-Mattausch, E., & Greenberg, J. (2015). Understanding psychological reactance: New developments and findings. Zeitschrift fur Psychologie, 223, 205–214. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000222.

Stright, A. D., & Bales, S. S. (2003). Coparenting quality: Contributions of child and parent characteristics. Family Relations, 52, 232–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2003.00232.x.

Van Bakel, H. J. A., Van Engen, M. L., & Peters, P. (2018). Validity of the parental burnout inventory among dutch employees. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 697 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00697.

Wang, X., Yang, J., Zhou, J., & Zhang, S. (2022). Links between parent–grandparent coparenting, maternal parenting and young children’s executive function in urban China. Early Child Development and Care, 192, 2383–2400. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2021.2014827.

Wen, Z., & Ye, B. (2014). Analyses of mediating effects: The development of methods and models. Advances in Psychological Science, 22, 731–745. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1042.2014.00731.

Yang, B., Chen, B.-B., Qu, Y., & Zhu, Y. (2021). Impacts of parental burnout on Chinese youth’s mental health: The role of parents’ autonomy support and emotion regulation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50, 1679–1692. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-021-01450-y.

Zou, X., Lin, X., Jiang, Y., Su, J., Qin, S., & Han, Z. R. (2020). The associations between mothers’ and grandmothers’ depressive symptoms, parenting stress, and relationship with children: An actor–partner interdependence mediation model. Family Process, 59, 1755–1772. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12502.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32171068), Humanities and Social Sciences Research Project of the Ministry of Education in China (No. 21YJCZH009), and Shuguang Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission and Shanghai Education Development Foundation (No. 23SG01) as well as Fudan University’s “Double First Class” initiative key project “Sociological Theory and Method Innovation Platform for Social Transformation and Governance”, and the research fund of the School of Social Development and Public Policy at Fudan University

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, B., Sun, J., Sun, F. et al. The Association Between Marital Satisfaction and Parental Burnout: A Moderated Mediation Model of Parents’ and Grandparents’ Coparenting. J Child Fam Stud 33, 1172–1183 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-024-02804-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-024-02804-3