Abstract

Parental burnout is a specific syndrome resulting from enduring exposure to chronic parenting stress. It encompasses three dimensions: an overwhelming exhaustion related to one’s parental role, an emotional distancing with one’s children and a sense of ineffectiveness in one’s parental role. This study aims to facilitate further identification of antecedents/risk factors for parental burnout in order to inform prevention and intervention practices. In a sample of 1723 french-speaking parents, we examined the relationship between parental burnout and 38 factors belonging to five categories: sociodemographics, particularities of the child, stable traits of the parent, parenting and family-functioning. In 862 parents, we first examined how far these theoretically relevant risk factors correlate with burnout. We then examined their relative weight in predicting burnout and the amount of total explained variance. We kept only the significant factors to draw a preliminary model of risk factors for burnout and tested this model on another sample of 861 parents. The results suggested that parental burnout is a multi-determined syndrome mainly predicted by three sets of factors: parent’s stable traits, parenting and family-functioning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Parenting has been shown to be both complex and stressful (for reviews, see Abidin and Abidin 1990; Crnic and Low 2002; Deater-Deckard 2008). Parenthood-related specific stressors include daily hassles (e.g., chores, homework, home-school-extracurricular activities journeys), acute stressors (e.g., a child choking, an adolescent running away) and chronic stressors (e.g., a child with behavioral, learning or mood disorders; a child with a chronic or serious illness). Whatever its source (environmental, child and/or parental characteristics), chronic parenting stress has negative consequences, not only on the parent’s well-being (Kwok and Wong 2000) but also on parenting practices (Assel et al. 2002), parent-child interaction and child development (e.g., Crnic et al. 2005; Feldman et al. 2004). It is also significantly detrimental to marital relationships (Lavee et al. 1996).

In organizational behavior literature, it has been shown that when chronic stress lasts too long, it depletes employees’ resources, eventually leading to burnout, which corresponds to a collapse of the ability to cope with stress. This collapse is evident at the psychological level but also at the physiological level (Pruessner et al. 1999). The individual therefore lacks the necessary resources to cope with stressors, which explains that burnout is even more detrimental than chronic stress. Research conducted on job burnout shows that it has dramatic effects on employees’ mental health (increasing the risk of alcohol dependence—Ahola et al. 2006—and depression—Hakanen et al. 2008) as well as on physical health (increasing the risk of serious health conditions—Ahola et al. 2009; Melamed et al. 2006—and premature death—Ahola et al. 2010). Beyond affecting the individuals concerned, burnout also impacts the organization and its clients by increasing the frequency of errors (West et al. 2006) and augmenting neglectful behaviors (Pillemer and Bachman-Prehn 1991) and even abuse (Borteyrou and Paillard 2014).

While extensive research has been conducted on job burnout (more than 23,000 studies to date), parental burnout has only very recently become the focus of scientific interest (see Pelsma 19891989 for the only exception before 2007) with empirical evidence that parenting stress can lead to parental burnout (Lindahl Norberg et al. 2014; Lindström et al. 2011; Lindahl Norberg 2007, 2010). Like job burnout, parental burnout encompasses three dimensions. The first is overwhelming exhaustion related to one’s parental role: parents feel that being a parent requires too much involvement; they feel tired when getting up in the morning and having to face another day with their children; they feel emotionally drained by the parental role to the extent that thinking about their role as parents makes them feel they have reached the end of their tether. The second dimension is an emotional distancing with their children: exhausted parents become less and less involved in the upbringing and the relationship with their children; they do the bare minimum for the children but no more; the interactions are limited to functional/instrumental aspects at the expenses of the emotional aspects. The third dimension is a sense of ineffectiveness in the parental role: parents feel that they cannot handle problems calmly and/or effectively. As for job burnout, parental burnout can be treated as a continuous variable, but people are considered as being “in burnout” only if they reach a certain threshold (i.e., PBI score above 67 in the case of parental burnout). As shown recently by Roskam et al. (2017), parental burnout is a unique syndrome, empirically distinct from job burnout, parental stress or depression.

Research on parental burnout is still in its infancy but studies to date have shown that it can be reliably measured (Roskam et al. 2017), that it concerns both mothers and fathers (Lindström et al. 2011; Roskam et al. 2017) and that its prevalence (between 8 and 36% depending on the types of parents studied; Lindström et al. 2011; Roskam et al. 2017) warrants further investigation. Many questions need to be addressed but one of the most pressing is certainly identifying burnout antecedents/risk factors, for this is a pre-requisite to developing suitable action in terms of both prevention and intervention. Because burnout arises from a lasting and significant imbalance of demands over resources (Maslach et al. 2001; Schaufeli et al. 2009), theoretically relevant risk factors for burnout involves factors (in the microsystem, mesosystem and macrosystem) that could either increase parental demands or diminish parental resources, or both. A close analysis of the available literature on parenting stress or burnout (when available) or commonsense suggests that factors that could increase parental demands or diminish parental resources (or both) can be categorized into five different categories of factors: socio-demographics, particularities of the child, stable traits of the parent, parenting cognitions and behaviors, and family functioning.

The following sociodemographic factors could increase the risk of burnout: being a women (because women are generally more involved in children’s care and upbringing than men; see also Lindahl Norberg 2007), having several children (because each additional child increases demands on the parent; Lundberg et al. 1994), having very young children (because young children cannot take care of themselves), being a single parent (because chores and responsibilities cannot be shared), having a blended family (because stepchildren may refuse their stepparent’s authority; Baxter et al. 2004), having inadequate living space (because lack of space prevents parents from having their own area and the possibility of getting away from noisy or boisterous children), having a low household income or having financial difficulties (because these make an number of resources unaffordable: babysitting services, extra-curricular activities; etc.), being unemployed (because this prevents the parent from having another source of preoccupation or self-esteem), working part-time (because the parent spends more time taking care of the children; Zick and Bryant 1996) or working more than 9 h per day (overwork may reduce temporal and emotional resources for dealing with children’s problems). By either increasing demand (e.g., having young children) or reducing resources (e.g., having a low household income) or both (e.g., being a single parent), these factors may increase vulnerability to parent burnout.

Because some of the child’s particular characteristics may increase demands on parents, the following factors could increase the risk for burnout: having a child with behavioral, emotional or learning disorders (because of the extra-care, attention and patience they require; Blanchard et al. 2006), having a child with a disability or chronic illness (for the same reason and also because treatments are time consuming and expensive; Lindahl Norberg et al. 2014; Lindström et al. 2011; Lindahl Norberg 2007, 2010) and having an adopted child (because of the stigma of adoption and of being adoptive parents; Miall 1987; Wegar 2000) or a foster child (because the child is at higher risk of exhibiting violent and sexually precocious behavior, and because of the potentially stressful, ambiguous and conflictual relationship with social workers and biological parents; Denby et al. 1999).

As suggested by Lindström et al. 2011, stable traits of the parent is expected to influence the vulnerability to parental burnout. Particular attention should be paid to neuroticism which has been found to be a major predictor of parenting stress (Vermaes et al. 2008) and to predict less efficient parental practices (see Prinzie et al. 2009 for a meta-analysis). Research on job burnout has also shown that personality traits related to affect and stress management (trait affectivity; emotional stability/neuroticism; emotional intelligence) were the most reliable and powerful trait predictors of burnout (Alarcon et al. 2009; Mikolajczak et al. 2007). Beyond personality, anxious and avoidant attachment may increase vulnerability to parental burnout, not only because they both increase stress responses (Armour et al. 2011; Smyth et al. 2015) but also because they are associated to less efficient parenting styles (e.g., Adam et al. 2004; Pearson et al. 1994) and greater risk of internalized and externalized problems in the respective children (Cowan et al. 1996).

Because parenting factors role restriction (i.e., the perceived loss of freedom associated with one’s parental role) is considered as being an important parental stressor (Abidin and Abidin 1990) and because it has already been shown that lower leisure time for oneself or as a couple could be a risk factor for burnout (Lindström et al. 2011), higher perceived role restriction should increase the risk of burnout. Parenting practices and self-efficacy must play a role too, as they influence how the child behaves and obeys (Aunola and Nurmi 2005; Boeldt et al. 2012; Mouton and Roskam 2015; Snyder et al. 2005; Wiggins et al. 2015). Higher parenting self-efficacy, positive parenting, autonomy demands and discipline should be associated with less burnout, while inconsistent discipline should be associated with more burnout.

The family is where parenting takes place, and three family functioning factors could play a role in burnout by increasing/decreasing demands on parents or resources to do their parental job: marital satisfaction, co-parenting and disorganization in the family. As already suggested by Lindström et al. (2011), a nurturing relationship, communication and happiness with one’s partner (i.e., greater marital satisfaction) is related with less parental burnout. Having a co-parent (the co-parent of the child is often the spouse, but not always in case of divorce) who agrees with one’s educational goals and practices, who cooperates in parenting decisions and who values one as a parent (i.e., good co-parenting) should also be related to less burnout, especially as it has recently been shown to be related to lower parenting stress (Durtschi et al. 2017). By contrast, disorganization in the family (i.e., chaotic home life: absence of routines, mess, agitation, noise etc.; Dumas et al. 2005) should be related to more burnout.

The aim of this research was to examine the relative weight of these five categories of theoretically relevant risk factors for parental burnout (sociodemographic factors, particularities of the child, stable traits of the parent, parenting and family functioning)—and of each factor within these five categories—in predicting parental burnout in order to derive a parsimonious model of putative antecedents of burnout in a general, non-specific, sample of parents. Modelling the risk factors of burnout involves four steps: First, examining the extent to which a number of theoretically relevant risk factors correlate with burnout. Second, including all predictors in a single analysis and examining their relative weight in predicting burnout and the amount of total explained variance. This will rule out a number of predictors, retaining only the significant ones to create a preliminary model of burnout risk factors. The third step consists of testing this model on another sample. The fourth and final step consists of validating the model in a longitudinal design that allows to disantangle causes from consequences and identify circularities. The study reported here focused on the first three steps and aims to provide the knowledge base on which the fourth step can be built. It is noteworthy that the current study and the resulting model focus on risk factors at the micro- and meso-system levels; investigating risk factors at the macrosystem level is of utmost importance too, but it requires a large multi-cultural study, that takes time to set up.

Method

Participants

Data were collected from a sample of 1723 french-speaking parents who had at least one child living at home. The sample comprised a majority of women (87%). Participants were aged 22 to 75 (mean age = 39.50; SD = 8.26). 15% of children were aged between 0 and 2; 22% were aged between 2 and 5; 27% between 6 and 11, 12% between 12 and 15, 8% between 16 and 18; 6% between 18 and 20 and 10% were above 20 years old. 1261 parents (73.2%) came from Belgium, 422 (24.5%) from other French-speaking European countries and 40 (2.3%) from outside Europe. The mean number of siblings was 2.30 (SD = 1.08), ranging from 1 to 7. Of the children, 194 (11.3%) had suffered or were suffering from chronic or severe illness or a disability. Of the parents, 1453 (84.3%) lived with a partner, i.e., 972 were married and 481 legal cohabitants; 270 (15.7%) were single parents. Also, 165 (9.5%) of the parents were living in a step family. The educational level of the parents was calculated as the number of years of education they had completed from first grade onward. Of the participants, 262 had completed 12 years, corresponding to the end of secondary school i.e., the end of compulsory education in Belgium (15.2%); 606 had completed 3 further years (corresponding to undergraduate studies) (35.2%); 855 had a degree of 4-years or more (49.6%). Net monthly household income was less than €2500 for 388 participants (22.4%), between €2500 and €4000 for 735 participants (42.7%), between €4000 and €5500 for 421 participants (24.4%) and higher than €5500 for 179 of them (10.5%).

Procedure

Preliminary results of a pilot study conducted in another sample of 379 parents suggested that sociodemographic factors, i.e., age, gender, marital status, educational level, income, number of children and their age range, accounted for a very limited part of the variance in parental burnout. It was therefore concluded that the association between parental burnout and other sets of risk factors should be studied in subsequent research. In the current study, participants completed a survey focusing on five categories of factors: sociodemographics, particularities of the child, stable traits of the parent, parenting and family functioning factors. Participants were informed about the survey through social networks, websites, schools, pediatricians or word of mouth. In order to avoid (self-)selection bias, participants were not informed that the study was about parental burnout. The study was presented as a study about “being a parent in the 21st century”. Parents were eligible to participate in the studies only if they had (at least) one child still living at home. Participants were invited to complete an online questionnaire after giving informed consent. The informed consent they signed allowed participants to withdraw at any stage without having to justify their withdrawal. They were also assured that data would remain anonymous. Participants who completed the questionnaire had the opportunity to enter a lottery with a 1/1000 chance of winning €200. Participants who wished to participate in the lottery had to provide their email address, but the latter was disconnected from their questionnaire. The questionnaire was completed online with the forced choice option, ensuring a dataset with no missing data.

Measures

Parental burnout was assessed with the Parental Burnout Inventory (PBI) (Roskam et al. 2017), a 22-item self-report questionnaire consisting of three subscales: Emotional Exhaustion (8 items) (e.g., I feel tired when I get up in the morning and have to face another day with my children; When I think about my parental role, I feel like I’m at the end of my rope), Emotional Distancing (8 items) (e.g., I sometimes feel as though I am taking care of my children on autopilot; I can no longer show my children how much I love them), and Loss of Personal Accomplishment (6 items) (e.g., I accomplish many worthwhile things as a parent (reversed); As a parent, I handle emotional problems very calmly (reversed). As the development of the Parental Burnout Inventory (PBI) was partly inspired by the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) (see Roskam et al. 2017 for further details concerning the development of the PBI), items are rated on the same 7-point Likert scale as in the original MBI: never (0), a few times a year or less (1), once a month or less (2), a few times a month (3), once a week (4), a few times a week (5), every day (6). A global score was obtained by summing the appropriate item scores, with higher scores indicating greater burnout; the items of the personal accomplishment factor were therefore reverse-scored. The PBI shows good psychometric properties (Roskam et al. 2017). Cronbach’s alphas in the current sample were .93 for Emotional Exhaustion, .83 for Emotional Distancing and .79 for Personal Accomplishment.

Socio-demographic factors

Participants were asked about their age, gender, number of children, gender and age of each child (age was asked under the form of 7 categories for each child: 0–2, 2–5, 6–11, 12–15, 15–18, 18–20, age marital status, type of family (single parent, living with the children’s father/mother, blended family), surface area of housing, level of education, net monthly household income, working time (being unemployed, part-time, full-time), work hours per day.

Particularities of the child

Participants were asked about each of their children whether the child displays behavioral problems, has a disability or chronic illness, or if s/he was an adopted or foster child.

Stable traits of the parent

These were: attachment, trait emotional intelligence and the big five personality traits.

Attachment was assessed by means of the widely used “Experiences in Close Relationships Questionnaire-Revised” (ECR-R) (Brennan et al. 1998; Fraley et al. 2000). The ECR-R consists of two subscales (18 items each): Anxiety (e.g., I worry about being abandoned) and Avoidance (e.g., I prefer not to show a partner how I feel deep down). In order to limit the total number of items in the survey, the five most representative items were selected in each of the two subscales based on factor loadings found in validation studies (Brennan et al. 1998; Fraley et al. 2000; Sibley and Liu 2004). A five-point Likert-type scale was provided for each item ranging from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly disagree”. The ECR-R has high construct and predictive validity (Sibley et al. 2005; Sibley and Liu 2004). Both the anxiety and avoidance subscales were remarkably stable over a 6-week assessment period (86% shared variance over time), which suggests that the ECR-R provides stability estimates of trait attachment that are largely free from measurement error over short periods of time (Sibley and Liu 2004). Cronbach’s alphas were of .94 for Anxiety and .86 for Avoidance in the current study.

Trait emotional intelligence was assessed using the Trait Emotional Intelligence Questionnaire–Short Form (TEIQue-SF; Cooper and Petrides 2010; French adaptation by Mikolajczak et al. 2007). This questionnaire consists of 30 items rated on a seven-point items (from strongly agree to strongly disagree). Examples of items are “I’m usually able to find ways to control my emotions when I want to” and “Generally, I find it difficult to know exactly what emotion I’m feeling (Reversed)” The internal and predictive psychometrics of the TEIQue-SF are excellent (Cooper and Petrides 2010). In this study, the internal consistency (alpha) of the scale was .90.

The Big Five personality traits were appraised by the Ten Item Personality (TIPI) measure (Gosling et al. 2003). The TIPI is a 10-item instrument based on the Big Five model. Items are presented in the form of “I see myself as” with a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from “disagree strongly” to 7 “agree strongly”. The two-item per factor format results in low Cronbach alphas which were .68, .40, .50, .73, and .45 for the Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, Emotional Stability, and Openness to Experience scales in the initial study (Gosling et al. 2003). They were .66, .37, .45, .60 and .47 in the current study. Despite its brevity and low alphas, this questionnaire shows good convergent and predictive validity (Gosling et al. 2003; Ehrhart et al. 2009).

Parental factors

They consisted of both parental cognitions (i.e., how parents think about themselves as a parent, in particular their self-efficacy beliefs and perceived role restriction) and parental behaviors (i.e., childrearing practices).

Self-efficacy beliefs were evaluated with the parenting problems subscale of the Parental Stress Questionnaire (PSQ) (Vermulst et al. 2011) consisting of 6 items (e.g., I can calm my child down when he/she gets angry, I am good at correcting my children when necessary) rated on a four-point Likert-type scale from “not true” to “very true”. Reliability reported for the parenting problem scale of the PSQ scales ranged from .82 and .84 according to the child age group under consideration (Vermulst et al. 2011). The Cronbach alpha in the current sample was .72.

Perceived role restriction was measured with the role restriction scale of the Parental Stress Questionnaire (PSQ) (Vermulst et al. 2011) consisting of 5 items (e.g., I have less contact with friends that I used because of my child) rated on a four-point Likert-type scale from “not true” to “very true”. Reliability reported for the parenting problem scale of the PSQ scales ranged from .74 and .79 according to the child age group under consideration (Vermulst et al. 2011). The Cronbach alpha found in the current sample was .86.

Childrearing practices were assessed with the Evaluation des Pratiques Educatives Parentales (EPEP) scale (Meunier and Roskam 2007) which is a 35-item instrument yielding nine factors: positive parenting (8 items; e.g., I make time to listen to my child when he/she wants to tell me something), monitoring (4 items; e.g., I keep track of the friends my child is seeing), rules (6 items; e.g., I teach my child to obey rules), discipline (4 items; e.g., When my child does something that I don’t want him/her to do, I punish him/her), inconsistent discipline (2 items; e.g., When my child doesn’t obey a rule, it happens that I threaten him/her with a punishment, but that in the end I don’t carry it out), harsh punishment (3 items; e.g., I slap my child when he/she has done something wrong), ignoring (3 items; e.g., When my child does something that is not allowed, I give him/her an angry look and pretend he/she is not there), material rewarding (3 items; e.g., I give my child money or a small present when he/she has done something that I am happy about), and autonomy demands (2 items; e.g., I teach my child to solve his/her own problems). A five-point Likert-type scale is provided for each item ranging from “never” to “always.” The EPEP scale has good psychometric properties (Meunier and Roskam 2007). In order to limit the total number of items in the current survey, the “material rewarding” and “monitoring” scales were dropped because they were for the most part unsuitable for infants. Therefore, 28 items out of 35 were considered in the survey. Alphas ranged from .66 to .88.

Family functioning factors

They consisted of marital satisfaction, coparenting and family disorganization.

Marital satisfaction was assessed with the ENRICH (Evaluation and Nurturing Relationship Issues, Communication and Happiness) scale consisting of 15 items (e.g., My partner and I understand each other perfectly) rated on a five-point scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) (Fowers and Olson 1993). In the current study, 9 items out of 15 were used to limit the total number of items in the survey. In particular, items focusing on satisfaction with regard to religious beliefs, relations with parents in-law, leisure time and financial position, were deleted. In the initial validation study (Fowers and Olson 1993), the Cronbach’s alpha was .86. It was .88 in the current sample.

Coparenting perceptions were assessed by means of the revised Co-Parenting Scale (CPS) (Feinberg et al. 2012), which consists of six subscales: Agreement (4 items; e.g., My partner and I have the same goals for our child(ren)), Increased Closeness (5 items; e.g., I feel close to my partner when I see him (her) play with our child(ren)), Exposure to Conflict (5 items; e.g., How many times a week do you argue with your partner in front of your child(ren)?); Active Support/Cooperation (6 items; e.g., My partner supports my parenting decisions); Competition/Undermining (6 items; e.g., My partner sometimes makes jokes or sarcastic comments about the way I am as a parent;); and Endorsement of Partner’s Parenting (e.g., I think that my partner is a good parent; seven items). Items are rated on a seven-point Likert-scale from 1 (not at all true for us) to 7 (absolutely true for us). Cronbach’s alphas ranged from .69 to .85 in the current sample.

Family disorganization was assessed with the CHAOS (Confusion Hubbub And Order Scale), a 15-item measure of “environmental confusion and disorganization in the family”, i.e., high levels of noise, crowding, and home traffic, in children’s development (Matheny et al. 1995). Example of items are: “We can usually find things when we need them” or “The atmosphere in our home is calm”. Based on current usage, a single score was derived from the CHAOS questionnaire to represent the parent’s report of home characteristics, corresponding to the simple sum of responses for the 15 items. The true or false responses were scored so that a higher score represented more chaotic, disorganized, and time-pressured homes. In the initial validation study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the 15 CHAOS items was .79 and test-retest stability correlation was .74 (Matheny et al. 1995). In the current study, reliability was .79.

Data Analyses

Modelling the risk factors of burnout involved three steps: First, examining the extent to which a number of theoretically relevant risk factors correlated with burnout. Second, including all predictors in a single analysis and examining their relative weight in predicting burnout and the amount of total explained variance. This ruled out a number of predictors, and only the significant ones were retained to create a preliminary model of burnout risk factors. The third step consists of testing this model on another sample. This procedure thus involves an exploratory part (Steps 1 and 2) and a confirmarory part (Step 3). Because these two parts must be conducted in separate samples to be valid, our sample of 1723 subjects was randomly split into two subsamples of 862 and 861 participants respectively. The comparability of the two subsamples was checked and they were found to be strictly similar with regard to socio-demographic characteristics. The first and second steps were conducted with the subsample of 862 participants. The first step consisted of examining which risk factors correlate with parental burnout in order to establish how far each factor of each set (sociodemographics, particularities of the child, stable traits of the parent, parenting and family functioning factors) was associated with parental burnout. This was done using parametric (Pearson) correlations since skewness, .80 (.08) and kurtosis, .28 (.16) of the PBI total score did not display deviation from normality. The second step consisted of including all predictors from each set of risk factors and examining their relative weight in predicting burnout and the amount of explained variance for each set. This was achieved through linear regressions. Thanks to these initial two steps, we drew up a preliminary model of the risk factors for parental burnout. The model included only the risk factors which had been found to be significantly related to parental burnout at a minimum r = .20 in the first step and which remained significant predictors in linear regression models in the second step. Also, only the sets of factors explaining a significant part of the variance in parental burnout in the second step were retained. The risk factors for the parental burnout model was tested in the third step in an independent sample, i.e., the second subsample of 861 participants. The statistical analyses were carried out using SEM software AMOS 18.0 (Arbuckle 1995, 2007). Again, the data were checked for normality. Skewness, 1.03 (.08), and kurtosis, 1.16 (.16), indicated that the PBI total score did not display strong deviation from normality in this second sample either. Structural equation modeling analyses using Maximum Likelihood estimation were completed in two phases: a measurement phase and a structural phase. The measurement phase examines the relationship between the latent variables and their measures (i.e., do the measures correctly represent the expected latent construct? For instance, do neuroticism, emotional intelligence and attachment form a coherent latent construct?). As stated, the indicators for the latent variables were chosen on the basis of the two preliminary steps of data analyses. The structural phase examines the relationship between the latent variables (i.e., what are the relationships between the latent risk factors and parental burnout? For instance, do neuroticism, emotional intelligence and attachment form a coherent latent construct?). Evaluation of the fit of the model was carried out on the basis of inferential goodness-of-fit statistics (χ²) and χ²/df, the comparative fit index (CFI) (Marsh and Hau 2007) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (Cole and Maxwell 2003). The chi-square compares the observed variance-covariance matrix with the predicted variance-covariance matrix. It theoretically ranges from 0 (perfect fit) to ∞ (poor fit). It is considered satisfactory when it is non-significant (p > .05) (Byrne 2001). Note that for models with a maximum of 200 cases, the chi square test is considered as a good measure of fit. However, for models with more than 400 cases (which is the case here), the chi square is almost always statistically significant (Byrne 2001; Hu and Bentler 1999). In the current study, chi square is given for information purposes and the Hoelter index is given—this states the sample size at which chi square would not be significant (alpha = .05). Values close to or greater than .90 are desirable on the CFI, while the RMSEA should preferably be less than or equal to .06 with a confidence interval with a lower bound near zero and the higher bound less than .08 (Hu and Bentler 1999).

Results

Step 1

Bivariate correlations between parental burnout and sociodemographics, particularities of the child, parents’ stable traits, parenting and family functioning factors risk factors are presented in Table 1. Factors from the Sociodemographics and Particularities of the child sets presented correlations ranging from .00 to .10 with parental burnout. In the Parents’ stable traits set, attachment, i.e., both anxiety and avoidance, neuroticism and emotional intelligence were associated with parental burnout in the expected direction. In the Parenting factors set, both parental cognitions and childrearing behaviors, in particular autonomy demands and positive parenting were linked to parental burnout. Parents with higher self-efficacy beliefs, lower role restriction feelings, displaying higher autonomy demands and positive parenting were less likely to display parental burnout. In the Family functioning set, all factors were associated to burnout, with lower marital satisfaction, coparenting quality and higher family disorganization linking to higher burnout.

Step 2

Results of the linear regression analyses are presented in Table 2. They first showed that sociodemographic factors explained a very small part of the variance in parental burnout. Coefficients and post-hoc comparisons indicated that having a young child, i.e., less than 5-year-old, was associated to burnout as well as working part-time compared to working full-time or being unemployed. These analyses also showed that particularities of the child explained less than 1% of the variance in parental burnout. Having a child with behavioral problems, chronic illness, or disability was marginally associated to burnout. And having an adopted or foster child was not significantly associated to burnout. By contrast, Parents’ stable traits explained a total of 22% of the variance in parental burnout. In particular, avoidant attachment was marginally associated to the outcome, and both higher neuroticism and lower emotional intelligence resulted in higher burnout. A total of 45% of the variance was explained by parenting factors, especially self-efficacy beliefs, perceived role restriction and positive parenting. Parental self-confidence and positive childrearing practices were associated with lower burnout, while feeling restricted by one’s parental role was linked to higher burnout. Family functioning factors accounted for 29% of the variance, with marital satisfaction, coparental agreement, low exposure to conflict, low family disorganization and increased closeness marginally explaining lower levels of parental burnout. Finally, entering all the predictors in a regression model accounted for 57% of the variance.

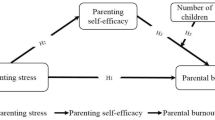

Step 3

Based on the first two steps, we constructed the risk factor model for parental burnout. We decided a priori to retain in the model the factor sets which would explain a significant part of the variance at Step 2, as well as the risk factors which would display a bivariate correlation with burnout of at least r = .20 at Step 1 and which would remain significant predictors at Step 2. This resulted in a model encompassing three sets of factors, i.e., parents’ stable traits including emotional intelligence, neuroticism, and attachment avoidance as indicators, parenting factors including positive parenting, self-efficacy beliefs and perceived role restriction as indicators, and family functioning factors including marital satisfaction, coparenting agreement, exposure to conflict and family disorganization as indicators. The measurement model including the three sets of factors as latent variables and their indicators provided a good fit to the data: χ² (23) = 109.49, p > .05, χ²/df = 4.76, Hoelter = 277, CFI = .96, RMSEA = .06 ⦋.05–.07⦌. Standardized regression weights of the indicators on the latent EB variables ranged from .38 to .72 for stable traits of the parent, from .44 to .72 for parenting factors, and from .55 to .88 for family functioning factors. All paths were significant at p < .001. Correlations within the three sets of factors were .89 between parents’ stable traits and parenting factors, .66 between parenting and family functioning factors, and .73 between stable traits and family functioning. The structural model with significant paths is presented in Fig. 1. This model provided a good fit to the data: χ² (30) = 123.40, p > .05, χ²/df = 4.11, Hoelter = 306, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .06 ⦋.04–.07⦌. Thus, results found in an independent sample strongly supported a risk model where parental burnout arises mainly from three sources, i.e., parents’ stable traits, parenting and family functioning.

Discussion

This study examined the correlates of parental burnout in a sample of all types of parents and the relative weight of five categories of factors (socio-demographics, particularities of the child, parents’ stable traits, parenting factors and family-functioning) in predicting parental burnout. In so doing, it adds to both the literature on burnout and that on parenting stress because, to the best of our knowledge, such a study has not yet been undertaken regarding the latter. Our findings show that the socio-demographic factors and particularities of the child explain much less variance than expected. This does not mean that these factors do not play a role (they do, as shown by Lindahl Norberg and collaborators) or that they cannot act as amplifiers of other risk factors. It rather means that they simply weigh less than the three other categories of factors: stable characteristics of the parents, parenting factors and family functioning. In a way, this can be considered as good news: if parental burnout was mainly caused by socio-demographic factors and particularities of the child, two types of factors that cannot be changed, our room for maneuver as psychologists would be limited. However, it would not necessarily be null, as research in other domains has shown that listening to patients’ difficulties is therapeutic, even if nothing can be done to change these (Elliott et al. 2013).

If independent longitudinal research confirms that, in general, burnout is mainly caused by parents’ stable characteristics, parenting factors and family functioning, intervention studies should examine the extent to which improving emotional competencies, improving adult attachment, improving marital satisfaction, co-parenting and parenting practices would reduce parental burnout. For each of these factors, there exist targeted, validated and efficient interventions. As far as parents’ stable traits are concerned, the literature has shown that although these traits are relatively stable, they can be changed through interventions (see Roberts et al. 2017 for review). Interventions exist to improve emotional competencies that have been shown to decrease neuroticism and burnout symptoms (e.g., Karahan and Yalcin 2009: Kotsou et al. 2011; Nelis et al. 2011). There also exist efficient interventions to improve attachment, even in patients with severe attachment disorders such as borderline patients (e.g., Levy et al. 2006); as noted by Chaffin et al. (2006), there are a lot of inefficient and even harmful attachment therapies, but Transference-focused therapy (Foelsch and Kernberg 1998; Yeomans et al. 2013) and Schema Therapy (Young et al. 2003) have received convincing empirical validation. As regards parenting, interventions exist to improve parent self-efficacy (Roskam et al. 2015) and parenting practices, and these have proven their efficacy even with the most difficult children (see Mouton et al. 2017 for a meta-analysis). Finally, there are also efficient interventions to improve co-parenting (e.g., Linares et al. 2006) and marital satisfaction (e.g., Christensen et al. 2010). Because each burnout has its own history, researchers should pay attention to the fit between the intervention and the parent: the intervention may be more efficient if it is preceded by a comprehensive analysis of the parent’s specific risk factors (There is no point in targeting emotional competence if the parent’s main problem is poor parenting practices).

As a note of caution to researchers interested in developing interventions to help burn-out parents, the targeted interventions that may stem from the model proposed in this paper should not mask the importance of active listening and the therapeutic relationship. The qualitative research that we are conducting in parallel to quantitative research shows that burned-out parents feel particularly guilty (for no longer being the parent they wanted to be; for wanting to take a break from parenting; for yelling at their children and, sometimes, neglecting or hitting them) and ashamed (because they think something is wrong with them, that people will think they are bad mothers or bad fathers). Therefore, therapeutic attitudes such as empathy and an unconditional positive regard seem particularly important when working with these parents, as they are a prerequisite to open a safe space where parents can express their emotions and difficulties.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

While the current study has the merit of providing a knowledge base on which longitudinal and experimental studies can build, it is not exempt from limitations. First, the data were collected through an open invitation and we had therefore no control over response rate and self-selection. Because the study was entitled “Being a parent in the 21st century”, it is likely that only parents interested in parenting issues responded to the survey. Therefore, it is unclear whether results can generalize to parents with no interest in their parenting role. Second, the brevity of the personality measure (i.e., two items per dimension) may make the results a little less reliable. Third, we voluntarily excluded from the study (and from the model) the stressors that people face in other domains of their life (e.g., work stress, conflicts with extended family or neighbors, conviction and other major life events): there are so many of these that it was impossible to consider them all. Fourth, the model does not take into account the wider context in which parents live (e.g., more or less advantaged community; cultural values). Yet, these two categories of factors probably explain part of the variance left unexplained by the model (it currently explains 57% of the variance in parental burnout). Finally, whereas the qualitative interviews that we have conducted so far seem to corroborate current findings, they also suggest that we failed to include in the model one stable parent characteristic that could potentially play an important role in parental burnout: high parental standards. An impressive proportion of burned-out parents that we interviewed seem to have very high parental standards (which come either from a more generally perfectionist personality or from an unhappy childhood that they do not want to reproduce). It is therefore possible that the part of variance explained by parents’ stable characteristics is greater than we have shown.

These limitations leave ample room for future research to probe and refine our findings. In addition to conducting cross-cultural research to identify macrosystemic antecedents of parental burnout and to conducting cross-lagged longitudinal and experimental intervention research to refine our understanding of causality links and processes among all types of parents, future studies should also concentrate on uncovering antecedents that play a specific role in specific categories of parents. Lindhal Norberg and colleagues have already done so among parents with chronically and/or severely ill-children. One of their studies (Lindström et al. 2011) suggested for instance that among the latter parents (whose child’s future is uncertain because of the disease), a high need for control may be a vulnerability factor for burnout. Other categories of parents (e.g., single parents, step-parents, gays and lesbian parents) may also each have specific antecedents in addition to the more general factors examined here. Refining the antecedent model for each category may help clinicians focus on the appropriate factors in each case.

References

Abidin, R. R., & Abidin, R. R. (1990). Parenting Stress Index (PSI). Charlottesville, VA: Pediatric Psychology Press.

Adam, E. K., Gunnar, M. R., & Tanaka, A. (2004). Adult attachment, parent emotion, and observed parenting behavior: Mediator and moderator models. Child Development, 75, 110–122.

Ahola, K., Honkonen, T., Pirkola, S., Isometsä, E., Kalimo, R., Nykyri, E., et al. (2006). Alcohol dependence in relation to burnout among the Finnish working population. Addiction, 101, 1438–1443.

Ahola, K., Toppinen-Tanner, S., Huuhtanen, P., Koskinen, A., & Vaananen, A. (2009). Occupational burnout and chronic work disability: An eight-year cohort study on pensioning among Finnish forest industry workers. Journal of Affective Disorders, 115, 150–159.

Ahola, K., Väänänen, A., Koskinen, A., Kouvonen, A., & Shirom, A. (2010). Burnout as a predictor of all-cause mortality among industrial employees: A 10-year prospective register-linkage study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 69, 51–57.

Alarcon, G., Eschleman, K. J., & Bowling, N. A. (2009). Relationships between personality variables and burnout: A meta-analysis. Work & stress, 23, 244–263.

Arbuckle, J. L. (1995). AMOS 18: IBM Softwares

Arbuckle, J. L. (2007). Amos 16.0 update to the Amos User’s Guide. Chicago, IL: Smallwaters Corporation.

Armour, C., Elklit, A., & Shevlin, M. (2011). Attachment typologies and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression and anxiety: A latent profile analysis approach. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 2, 6018.

Assel, M. A., Landry, S. H., Swank, P. R., Steelman, L., Miller‐Loncar, C., & Smith, K. E. (2002). How do mothers’ childrearing histories, stress and parenting affect children’s behavioural outcomes? Child: Care, Health and Development, 28, 359–368.

Aunola, K., & Nurmi, J.-E. (2005). The role of parenting styles in children’s problem behavior. Child Development, 76, 1144–1159.

Baxter, L. A., Braithwaite, D. O., Bryant, L., & Wagner, A. (2004). Stepchildren’s perceptions of the contradictions in communication with stepparents. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 21, 447–467.

Blanchard, L. T., Gurka, M. J., & Blackman, J. A. (2006). Emotional, developmental, and behavioral health of American children and their families: A report from the 2003 national survey of children’s health. Pediatrics, 117, e1202–e1212.

Borteyrou, X., & Paillard, E. (2014). Burnout et maltraitance chez le personnel soignant en gérontopsychiatrie. NPG Neurologie-Psychiatrie-Gériatrie, 14, 169–174.

Boeldt, D. L., Rhee, S. H., DiLalla, L. F., Mullineaux, P. Y., Schulz‐Heik, R. J., Corley, R. P., et al. (2012). The association between positive parenting and externalizing behaviour. Infant and Child Development, 21, 85–106.

Brennan, K. A., Clark, C. L., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Self-report measurement of adult attachment: An integrative overview. In J. A. Simpson & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 46–76). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS.. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Chaffin, M., Hanson, R., Saunders, B. E., Nichols, T., Barnett, D., Zeanah, C., et al. (2006). Report of the APSAC task force on attachment therapy, reactive attachment disorder, and attachment problems. Child Maltreatment, 11, 76–89.

Christensen, A., Atkins, D. C., Baucom, B., & Yi, J. (2010). Marital status and satisfaction five years following a randomized clinical trial comparing traditional versus integrative behavioral couple therapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78, 225–35.

Cole, D. A., & Maxwell, S. E. (2003). Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: Questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 112, 558–577.

Cooper, A., & Petrides, K. (2010). A psychometric analysis of the trait emotional intelligence questionnaire-short form (TEIQue-SF) using item response theory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 92, 449–457.

Cowan, P. A., Cohn, D. A., Cowan, C. P., & Pearson, J. L. (1996). Parents’ attachment histories and children’s externalizing and internalizing behaviors: Exploring family systems models of linkage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 53–63.

Crnic, K. A., Gaze, C., & Hoffman, C. (2005). Cumulative parenting stress across the preschool period: Relations to maternal parenting and child behavior at age 5. Infant and Child Development, 14, 117–132.

Crnic, K., & Low, C. (2002). Everyday stresses and parenting. In M. H. Bornestein (Ed.), Handbook of Parenting Volume 5 Practical Issues in Parenting (pp. 243–268). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Deater-Deckard, K. (2008). Parenting stress. New haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Denby, R., Rindfleisch, N., & Bean, G. (1999). Predictors of foster parents’ satisfaction and intent to continue to foster. Child Abuse & Neglect, 23, 287–303.

Dumas, J. E., Nissley, J., Nordstrom, A., Smith, E. P., Prinz, R. J., & Levine, D. W. (2005). Home chaos: Sociodemographic, parenting, interactional, and child correlates. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 93–104.

Durtschi, J. A., Soloski, K. L., & Kimmes, J. (2017). The dyadic effects of supportive coparenting and parental stress on relationship quality across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 43, 308–321.

Ehrhart, M. G., Ehrhart, K. H., Roesch, S. C., Chung-Herrera, B. G., Nadler, K., & Bradshaw, K. (2009). Testing the latent factor structure and construct validity of the Ten-Item Personality Inventory. Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 900–905.

Elliott, R., Watson, J., Greenberg, L. S., Timulak, L., & Freire, E. (2013). Research on humanistic-experiential psychotherapies. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin & Garfield’s Handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (6th ed.). (pp. 495–538). New York, NY: Wiley.

Feinberg, M. E., Brown, L. D., & Kan, M. L. (2012). A multi-domain self-report measure of coparenting. Parenting: Science and Practice, 12, 1–21.

Feldman, R., Eidelman, A. I., & Rotenberg, N. (2004). Parenting stress, infant emotion regulation, maternal sensitivity, and the cognitive development of triplets: A model for parent and child influences in a unique ecology. Child Development, 75, 1774–1791.

Foelsch, P. A., & Kernberg, O. F. (1998). Transference-focused psychotherapy for borderline personality disorders. Psychotherapy in Practice, 4, 67–90.

Fowers, B. J., & Olson, D. H. (1993). ENRICH Marital Satisfaction Scale: A brief research and clinical tool. Journal of Family Psychology, 7, 176–185.

Fraley, R. C., Waller, N. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78, 350–365.

Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann, Jr., W. B. (2003). A very brief measure of the big five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37, 504–528.

Hakanen, J. J., Schaufeli, W. B., & Ahola, K. (2008). The job demands-resources model: A three-year cross-lagged study of burnout, depression, commitment, and work engagement. Work & Stress, 22, 224–241.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Iacovides, A., Fountoulakis, K. N., Kaprinis, S., & Kaprinis, G. (2003). The relationship between job stress, burnout and clinical depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 75, 209–221.

Karahan, T. F., & Yalcin, B. M. (2009). The effects of an emotional intelligence skills training program on anxiety, burnout and glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Turkiye Klinikleri Journal of Medical Sciences, 29, 16–24.

Kotsou, I., Nelis, D., Grégoire, J., & Mikolajczak, M. (2011). Emotional plasticity: conditions and effects of improving emotional competence in adulthood. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 827–839.

Kwok, S., & Wong, D. (2000). Mental health of parents with young children in Hong Kong: The roles of parenting stress and parenting self-efficacy. Child and Family Social Work, 5, 57–65.

Lavee, Y., Sharlin, S., & Katz, R. (1996). The effect of parenting stress on marital quality an integrated mother-father model. Journal of Family Issues, 17, 114–135.

Levy, K. N., Clarkin, J. F., & Kernberg, O. F. (2006). Change in attachment and reflective function in the treatment of borderline personality disorder with transference focused psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 1027–1040.

Linares, L. O., Montalto, D., Li, M., & Oza, V. S. (2006). A promising parenting intervention in foster care. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 32–41.

Lindahl Norberg, A., Mellgren, K., Winiarski, J., & Forinder, U. (2014). Relationship between problems related to child late effects and parent burnout after pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Pediatric Transplantation, 18, 302–309.

Lindström, C., Aman, J., & Norberg, A. L. (2011). Parental burnout in relation to sociodemographic, psychosocial and personality factors as well as disease duration and glycaemic control in children with Type 1 diabetes mellitus. Acta Paediatrica, 100, 1011–1017.

Lundberg, U., Mårdberg, B., & Frankenhaeuser, M. (1994). The total workload of male and female white collar workers as related to age, occupational level, and number of children. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 35, 315–327.

Marsh, H. W., & Hau, K.-T. (2007). Applications of latent-variable models in educational psychology: The need for methodological-substantive synergies. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 32, 151–170.

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422.

Matheny, A. P., Wachs, T. D., Ludwig, J. L., & Philips, K. (1995). Bringing order out of chaos: Psychometric characteristics of the confusion, hubbub, and order scale. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 16, 429–444.

Melamed, S., Shirom, A., Toker, S., Berliner, S., & Shapira, I. (2006). Burnout and risk of cardiovascular disease: evidence, possible causal paths, and promising research directions. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 327–353.

Meunier, J. C., & Roskam, I. (2007). Psychometric properties of a parental childrearing behavior scale for French-speaking parents, children, and adolescents. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 23, 113–124.

Miall, C. E. (1987). The stigma of adoptive parent status: Perceptions of community attitudes toward adoption and the experience of informal social sanctioning. Family Relations, 36, 34–39.

Mikolajczak, M., Menil, C., & Luminet, O. (2007). Explaining the protective effect of trait emotional intelligence regarding occupational stress: Exploration of emotional labor processes. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 1107–1117.

Mouton, B., Loop, L., Stievenart, M., & Roskam, I. (2017). Meta-analytic review of parenting programs to reduce child externalizing behavior. Paper in press at Child and Family Behavior Therapy.

Mouton, B., & Roskam, I. (2015). Confident mothers, easier children: A Quasi-experimental manipulation of mothers’ self-efficacy. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 2485–2495.

Nelis, D., Kotsou, I., Quoidbach, J., Hansenne, M., Weytens, F., Dupuis, P., & Mikolajczak, M. (2011). Increasing emotional competence improves psychological and physical well-being, social relationships, and employability. Emotion, 11, 354–366.

Norberg, A. L. (2007). Burnout in mothers and fathers of children surviving brain tumour. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 14, 130–137.

Norberg, A. L. (2010). Parents of children surviving a brain tumor: Burnout and the perceived disease-related influence on everyday life. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology, 32, e285–e289.

Pearson, J. L., Cohn, D. A., Cowan, P. A., & Cowan, C. P. (1994). Earned-and continuous-security in adult attachment: Relation to depressive symptomatology and parenting style. Development and Psychopathology, 6, 359–373.

Pelsma, D. M. (1989). Parent Burnout: Validation of the Maslach Burnout Inventory with a Sample of Mothers. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 22, 81–87.

Pillemer, K., & Bachman-Prehn, R. (1991). Helping and hurting: Predictors of maltreatment of patients in nursing homes. Research on Aging, 13, 74–95.

Prinzie, P., Stams, G. J. J., Deković, M., Reijntjes, A. H., & Belsky, J. (2009). The relations between parents’ big five personality factors and parenting: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 351–362.

Pruessner, J. C., Hellhammer, D. H., & Kirschbaum, C. (1999). Burnout, perceived stress, and cortisol responses to awakening. Psychosomatic Medicine, 61, 197–204.

Roberts, Brent W., Luo, Jing, Briley, Daniel A., Chow, Philip I., Su, Rong, Hill, Patrick L. (2017). A systematic review of personality trait change through intervention. Article in press at Psychological Bulletin.

Roskam, I., Brassart, E., Loop, L., Mouton, B., & Schelstraete, M.-A. (2015). Stimulating parents’ self-efficacy beliefs or verbal responsiveness: which is the best way to decrease children’s externalizing behaviors? Behavior Research and Therapy, 72, 38–44.

Roskam, I., Raes, M.-E., & Mikolajczak, M. (2017). Exhausted parents: Development and preliminary validation of the parental burnout inventory. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 162.

Schaufeli, W. B., Leiter, M. P., & Maslach, C. (2009). Burnout: 35 years of research and practice. Career Development International, 14, 204–220.

Sibley, C. G., Fischer, R., & Liu, J. H. (2005). Reliability and Validity of the Revised Experiences in Close Relationships (ECR-R) Self-Report Measure of Adult Romantic Attachment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1524–1536.

Sibley, C. G., & Liu, J. H. (2004). Short-term temporal stability and factor structure of the revised experiences in close relationships (ECR-R) measure of adult attachment. Personality and Individual differences, 36, 969–975.

Smyth, N., Thorn, L., Oskis, A., Hucklebridge, F., Evans, P., & Clow, A. (2015). Anxious attachment style predicts an enhanced cortisol response to group psychosocial stress. Stress, 18, 143–148.

Snyder, J., Cramer, A., Afrank, J., & Patterson, G. (2005). The contributions of ineffective discipline and parental hostile attributions of child misbehavior to the development of conduct problems at home and school. Developmental Psychology, 41, 30–41.

Vermaes, I. P. R., Janssens, J. M. A. M., Mullaart, R. A., Vinck, A., & Gerris, J. R. M. (2008). Parents’ personality and parenting stress in families of children with spina bifida. Child: Care, Health and Development, 34, 665–674.

Vermulst, A. A., Kroes, G., De Meyer, R. E., & Veerman, J. W. (2011). Parenting Stress Questionnaire OBVL for parents of children aged 0 to 18. Nijmegen: Praktikon bv.

Wegar, K. (2000). Adoption, family ideology, and social stigma: Bias in community attitudes, adoption research, and practice. Family Relations, 49, 363–369.

West, C. P., Huschka, M. M., Novotny, P. J., Sloan, J. A., Kolars, J. C., Habermann, T. M., & Shanafelt, T. D. (2006). Association of perceived medical errors with resident distress and empathy: a prospective longitudinal study. Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), 296, 1071–1078.

Wiggins, J. L., Mitchell, C., Hyde, L. W., & Monk, C. S. (2015). Identifying early pathways of risk and resilience: The codevelopment of internalizing and externalizing symptoms and the role of harsh parenting. Development and Psychopathology, 27, 1295–1312.

Yeomans, F. E., Levy, K. N., & Caligor, E. (2013). Transference-focused psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 50, 449–453.

Young, JeffreyE., Klosko, Janet, S., & Weishaar, MarjorieE. (2003). Schema therapy: Apractitioner’s guide. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Zick, C. D., & Bryant, W. K. (1996). A new look at parents’ time spent in child care: Primary and secondary time use. Social Science Research, 25(3), 260–280.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by an FSR Research Grant from the Université catholique de Louvain. We warmly thank the following persons for their help in the data collection: France Gérard from the Mutualité Chrétienne, as well as our students Cléa Chaudet, Céline Derwael, Bérénice Grumiaux, Flore Mehauden and Virginie Piraux. We also thank Gillian Rosner for proofreading the manuscript.

Author Contributions

M.M., I.R., M.E.R., and H.A. designed the study. M.E.R. and H.A. recruited participants. I.R. performed the data analyses and wrote the Methods and Results section. M.M. wrote the Introduction and Discussion sections. All authors proofread and edited the final manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. The Ethics Committee of the Institut de Recherches en Sciences Psychologiques (IPSY) of the Université catholique de Louvain provided IRB approval for this study (Protocol Number 15-43).

Additional information

Funding

This study was funded by a FSR-2016 Grant from the Université catholique de Louvain.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mikolajczak, M., Raes, ME., Avalosse, H. et al. Exhausted Parents: Sociodemographic, Child-Related, Parent-Related, Parenting and Family-Functioning Correlates of Parental Burnout. J Child Fam Stud 27, 602–614 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0892-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0892-4