Abstract

A handful of meta-analytic studies of have documented the impact of couple relationship education (CRE) programs on couple outcomes. Recently, an increasing number of studies have examined whether CRE also impacts a wider set of family outcomes. Basic research demonstrates the importance of positive couple relationship quality for effective parenting and child well-being. This meta-analytic study investigates whether CRE programs have effects on coparenting, parenting, and child outcomes. We analyzed 40 control-group studies and found small, average effect sizes for coparenting (d = 0.073, p < 0.01) and child well-being/behavior (d = 0.056, p < 0.01), but not for parenting (d = 0.023, ns). (Effect sizes for 12 1-group/pre-post studies are reported in online supplemental appendix S2.) Moderator analyses of control-group studies found differences in several methodological and participant characteristics that provide potential clues for future research and improving the practice of CRE to improve children’s well-being.

Highlights

-

40 control-group studies found small but significant average effect sizes for coparenting and child well-being/behavior, but not for parenting.

-

Larger effects were found for more recent studies, studies conducted outside the purview of the ACF-OPRE, studies with treatment-on-the-treated analyses, and studies of programs that included both married and unmarried couples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Several meta-analytic studies of evaluation research on couple relationship education (CRE) programs have documented their effects on couple outcomes (Arnold & Beelman, 2019; Blanchard et al., 2009; Fawcett et al., 2010; Hawkins et al., 2008; Hawkins & Erickson, 2015; Lucier-Greer & Adler-Baeder, 2012; McAllister et al., 2012; Pinquart & Teubert, 2010). However, to date, none have systematically reviewed whether CRE programs have effects on parenting and child outcomes. This meta-analytic study focuses on a growing body of CRE evaluation studies that have measured effects on a broader set of family outcomes. Our objective is to document the effects of CRE programs on (a) coparenting, (b) parenting, (c) and child well-being and behavior outcomes and what factors moderate any effects. Our focus is on rigorous control-group studies (although we present results for 1-group/pre-post studies—analyzed separately—in an online supplemental appendix).

A relevant backdrop for this review is federal policy supporting CRE programming (Hawkins, 2019; Randles, 2017). Since 2006, the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) has invested more than $1.2 billion in couple relationship education (CRE) and individually-oriented relationship education (RE) for lower income individuals and families to strengthen relationships and increase family stability. About 2.5 million people have participated in these ACF-funded programs at a median cost of about $400 per participant (Hawkins, 2019). The policy—referred to now as the Healthy Marriages and Relationships Education (HMRE) initiative—sparked considerable debate among social scientists and policy scholars (Hawkins, 2019). Early evaluation results of no or small effects generated criticism of the policy (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2019) and calls for abandoning the initiative (Reeves, 2014). Recent results, however, have been more promising (Hawkins, 2019). Many of the studies reviewed here were associated with this federal policy initiative.

From a social policy perspective, the ultimate hope is that stronger couple relationships will improve outcomes for children. That is, an important rationale for this policy initiative is that healthy relationships between parents—regardless of their relationship status—may have spillover effects on parenting and coparenting behavior, which in turn will increase the well-being of disadvantaged children. The logic for this is based in systems theory and a large volume of research that links couple relationship quality to parenting (Carlson & McLanahan, 2006), coparenting (Christopher et al., 2015), and child (Brown, 2010) outcomes. This body of work demonstrates the importance of positive parental relationship quality for effective parenting and child well-being (Cowan & Cowan, 2014; Cummings & Davies, 2002; Knopp et al., 2017). A recent meta-analysis of 230 studies confirms that interparental conflict is concurrently and longitudinally associated with children’s maladjustment (van Eldik et al., 2020). A number of CRE programs now also include some direct instruction on cooperative coparenting and effective parenting. A few CRE evaluation studies have explicitly linked positive intervention changes in couple relationship outcomes to positive changes in parenting and coparenting behaviors, which in turn are associated with positive child outcomes (Fienberg & Jones, 2018; Pruett et al., 2019; Sterrett-Hong et al., 2018; Zemp et al., 2016).

Method

Search Procedure

Meta-analytic studies are exempted from human subjects reviews at the authors’ institution. The researchers did not receive any external funding for the study. The search for relevant studies for this meta-analysis was embedded in a search for a broader set of CRE studies (Hawkins et al., 2021), then modified in the last stages to focus on the specific outcomes of interest. This search process included the following steps. To identify potential studies, we first searched two electronic databases (PsychINFO; Family & Society Studies Worldwide) in May 2020. We experimented with a range of search terms and combinations of terms; we settled on simply “relationship education program,” which proved to be the best starting point because it captured RE evaluation studies while limiting the number of correlational studies. We also supplemented this first-stage electronic search with several other procedures. We looked at several review articles and recently published reports for citations of potential studies. Moreover, we examined references from included studies for potential studies that may have been missed, including so-called “gray literature” (e.g., technical reports, dissertations). Further, we browsed the websites of federally funded CRE programs known to be actively publishing evaluation studies for lists of research reports and published studies. During the process, we also contacted active researchers in this field for clarifications about certain studies (e.g., overlapping samples) and asked them if they had any studies (published or unpublished) not on our accepted-studies list. This yielded several more recent (in press) studies. Unfortunately, research assistants did not account for examined records/studies with each of these steps, a methodological oversight on the first author’s part.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Outcomes

To be included in the meta-analysis, a study had to be an empirical evaluation of a CRE program and measure at least one of the following constructs: (a) coparenting (e.g., coparenting conflict, competition, positivity, disagreements, hostility); (b) parenting (e.g., harshness, hostility, parental negativity/positivity, responsiveness, supportiveness, father engagement/involvement/care/play); (c) child well-being/behavior outcomes (e.g., externalizing/internalizing behaviors, anxiety/depression, adjustment, aggression, emotion dysregulation, social competence, withdrawal, self-regulation). While it may be appealing to investigate some of these measures separately (e.g., father involvement from parental harshness), doing so risks underpowered analyses.

Relationship intervention

Also, to be included in the study, programs had to give strong attention to the couple relationship. Some programs focus curriculum on more effective parenting and coparenting, with some programs referring to themselves as coparenting education. In these programs, more attention is given to parenting and working together effectively on behalf of their children, but some also include at least an equal weight on couple relationship skills (e.g., Supporting Father Involvement: Cowan et al., 2009; Family Foundations: Feinberg et al., 2010). If so, we included these studies in our meta-analysis.

Study design

We included both control-group studies and 1-group/pre-post studies. In some control-group studies, we could not find evidence that participants were rigorously randomized, but we included them and tested to see if these “quasi-experimental” studies were statistically different from RCT studies. Our primary focus is on rigorous control-group studies that are subject to fewer internal validity problems compared to 1-group/pre-post designs (Reichart, 2019). Still, there have been a significant number of 1-group/pre-post studies in this field over the last five years and they may be able to add a supplemental perspective to the research question. In this context, then, and in field circumstances where program administrators understandably resist excluding interested couples from participating in an intervention to help them strengthen their relationship, examining 1-group/pre-post studies is merited. However, we analyze these studies separately and report the results in online supplemental appendix S2 (along with the study references).

Note that we did not retain four studies that included alternative-treatment comparison groups rather than no-treatment control groups. In each of these excluded studies, we deemed that the alternative treatments were not placebos and could reasonably be expected to produce some similar effects on the outcome variables. Although these were noteworthy studies, group-difference effect sizes would be smaller for these studies and could bias the overall effect size in the meta-analysis.

Couple focus

Some studies focused on individually-oriented relationship literacy RE programs for youth and young adults. These programs do not assume that participants are in couple relationships and do not expect that they attend as couples (although some do). Our focus was on programs that targeted couples, so we excluded individually-oriented RE programs. (And the outcomes they measure are mostly different from couple-oriented programs. See Simpson et al., 2018 for a review of these kinds of programs.) However, in some couple-oriented programs some participants could be attending without their partner.

Qualitative studies

We excluded qualitative evaluations (no effect size to calculate).

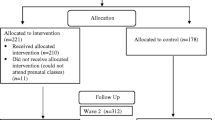

Ultimately, we reviewed 662 records and ended up fully coding 40 control-group studies, yielding 406 effect size calculations (and 12 1-group/pre-post studies with 65 effects). This final figure of 40 control-group studies includes adjustments made during the coding process. Some reports included multiple independent sites/samples or reported effects for multiple treatment groups, so they were coded separately. On the other hand, numerous reports from the same research team included samples that overlapped with other reports. Rather than employing the generalized-weights approach described by Bon and Rachinger (2017), we worked to identify overlapping samples and exclude them from our final set of studies. Or, if they added outcomes not reported in previous studies, we combined overlapping-samples studies for coding purposes. This was detail-oriented work that included careful reviews of studies and correspondence with authors. Nevertheless, this overlapping samples work assured us that units of analysis in the study were statistically independent. One study had a longer-term follow-up assessment with the treatment group that was not given to the control group, so we only coded for the immediate assessment. Finally, a few control-group studies had to be excluded because they did not provide sufficient data from which to calculate effect sizes. Fig. 1 graphically summarizes the inclusion/exclusion process and the number of studies excluded at each decision point. (Accepted studies are indicated with * in the reference list). Online supplemental appendix S1 contains a study characteristics table of included studies.

Variable Coding

We used a 31-item codebook to guide the coding process of methodological, programmatic, and effect size data. Reports were coded independently by four undergraduate research assistants, checked by four trained, advanced MS graduate students. Following independent coding, they met to discuss any coding differences. Although coding discrepancies were not frequent, when they did occur, the original study was examined further and discussed until the coders reached a consensus (sometimes with input from the first author). For instance, a common divergence was with coding sample size. While on the surface coding sample size seems straightforward, recruitment sample sizes often differ from sample sizes at the beginning of the intervention (due to drop-outs) and from the analytic sample (due to measurement non-compliance) for each coded outcome, etc., and coders could code different numbers. A joint inspection of the article focusing on analytic sample size resolves discrepancies.

Computing Effect Sizes

We computed standardized mean differences for control-group studies (and standardized mean gain effect sizes for 1-group/pre-post studies) based on the last outcome assessment available. For some studies this was the immediate post-intervention assessment, but most studies included follow-up assessments of various lengths (86% of effect sizes). We employed Biostat’s Comprehensive Meta-analysis III program to compute effect sizes, which were weighted by the inverse variance, giving greater weight to effects with smaller standard errors (larger samples). We used random effects models to estimate overall effect sizes. Random effects models allow for the possibility that variation in the distribution of effect sizes is a result not only of sampling error but also of differences in programs, research methods, and other factors (Borenstein et al., 2009). Overall effect sizes produced with random effects models are more generalizable to the large variety of CRE programs in the field. We followed up main analyses with Duval and Tweedie’s trim-and-fill analyses to examine potential missing-study bias.

Heterogeneity and Moderator Analyses

We expected significant heterogeneity in the distribution of effect sizes due to the differences in interventions, target populations, methods, and other factors. Accordingly, although we report mean effect sizes, we also give attention to heterogeneity. We report the range of effect sizes to draw attention to potential outlier studies that may indicate especially low or high effects. In addition, we report the prediction intervals (PI) for each of our outcome categories. As a measure of heterogeneity, the prediction interval specifies the two effect size values between which 95% of the true effect sizes would be expected to fall (Borenstein, 2019). When the PI and Q (test of homogeneity of effect sizes) indicated substantial heterogeneity in an outcome, we pursued moderator analyses to explore why some studies had stronger effect sizes. However, we limited moderator analyses to eight planned, substantive variables that likely could explain heterogeneity in the distribution of effect sizes and that had application for practice. (Note that we did not interpret moderator analyses when cells had fewer than five studies contributing to the effect size to diminish the risk of overinterpreting potentially unreliable group differences.) Moderator tests are observational rather than experimental; that is, moderator tests do not reflect an experimental manipulation of the independent variable. Significant moderators should be examined in primary experimental studies before drawing strong causal inferences.

The planned moderator analyses included tests for differences in study methods as well as participant and program characteristics. (a) Relationship status: some studies have found that married participants, who are generally more committed, benefit more from CRE (Hawkins & Erickson, 2015), but other studies have not found relationship status differences (Moore et al., 2018). (b) Relationship distress: many studies have found that couples in more distress at the start of the intervention benefit more from CRE (Amato, 2014; Hawkins et al., 2017), perhaps because they simply have more room to improve. (c) Economic disadvantage: many studies have found that economically disadvantaged couples benefit more from CRE (Hawkins et al., 2017), but one meta-analysis found that studies with samples of mostly near-poor participants did better than studies with samples of mostly poor participants (Hawkins & Erickson, 2015). (d) intervention dosage: some studies have found that programs with low dosage have smaller effects (Hawkins et al., 2008) but there may not be an advantage for the most intensive dosage programs (Stanley et al., 2006). (e) Curriculum content: some CRE programs include explicit coparenting and parenting content (CRE + ) that could boost effects on the targeted outcomes compared to CRE programs with a focus only on the couple romantic relationship. (f) study timing: studies of programs that came later could have learned from earlier programs and strengthened effects. (Among programs funded by ACF, there were explicit efforts to communicate lessons learned and best practices with other program administrators.) (g) Program funding: some evaluation studies were funded directly by ACF-OPRE and conducted by professional policy research organizations with very large budgets (i.e., BSF, SHM, PACT). Also, these studies employed larger samples and multiple (independent) sites. (h) Analyses: some studies employed intent-to-treat (ITT) analyses (outcome analyses on all participants regardless of their level of program participation) while others employed treatment-on-the-treated (TOT) analyses (outcome analyses only on those participants who received a strong dosage of the intervention). Both analytic approaches can yield valuable information; ITT analyses are more conservative and may better estimate the effect of treatment at a population level while ToT analyses may better estimate the effect of the treatment as intended.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

We conducted preliminary analyses to test whether randomized controlled trial (RCT) studies differed significantly from 7 control-group studies for which we could not establish that participants were randomly assigned. These studies can have biased effect sizes but can also be informative and excluding these studies from the meta-analysis could bias results, too (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). Effect sizes from RCT studies comparing treatment groups to no-treatment control groups were slightly smaller but not statistically different (dexp = 0.052, k = 33; dquasi = 0.152, k = 7; Q = 1.3, p = 0.26). Accordingly, we combined all control-group studies for analyses which provided more statistical power for our main analyses. (Note that 95% of computed effect sizes were from RCT studies).

We conducted power analyses on the set of control-group studies. One study found that five or more studies are needed for meta-analyses to achieve power that is greater than the individual studies that contributed to the overall effect size (Jackson & Turner, 2017). We anticipated small effects on outcomes for this study. For instance, one meta-analysis of couple outcomes with low-income couples assigned to a CRE treatment (compared to no-treatment controls) found a small aggregate effect size for relationship outcomes of d = 0.07 (Hawkins & Erickson, 2015). For control-group studies (k = 40), our power analyses yielded good power of 0.94 to detect a small effect size of 0.07 (with moderate heterogeneity). (For 1-group/pre-post studies (k = 10), however, statistical power was sufficient only when the 3 outcome categories were combined.) We used Tiebel’s meta-analysis power calculator for these calculations: https://www.jtiebel.com/2018/08/26/how-to-calculate-statistical-power-of-a-meta-analysis/.

Analyses for Control-Group Studies

Treatment-versus-no-treatment effect sizes for the three outcome categories and related statistics are presented in Table 1. (Supplemental appendix S3 provides all effect sizes and confidence intervals for all coded studies by outcome.) The average effect sizes for coparenting (d = 0.073, k = 32, p < 0.01) and child well-being/behavior (d = 0.056, k = 28, p < 0.01) were small but statistically non-zero. The average effect size for parenting outcomes (d = 0.023, k = 30, ns) was not significant. We conducted trim-and-fill analyses to examine potential missing-study bias. No bias was detected for coparenting and child outcomes but was detected for parenting, with the adjusted effect size further reduced to virtually zero.

The prediction intervals and Q-statistics of the outcomes revealed substantial heterogeneity only for the coparenting outcome, so we limited the set of planned moderator analyses to this outcome. These analyses are detailed in the upper panel of Table 2. Effect sizes for studies not funded by ACF-OPRE (d = 0.200, k = 14, p < 0.001) were significantly larger than those for the multisite studies funded by ACF-OPRE (d = 0.025, k = 18, p = 0.275; Q = 15.2, p < 0.001). In fact, the effect size for non–ACF-OPRE studies was the largest observed for control-group studies in this meta-analysis. The moderator analyses for study timing showed a similar pattern: program evaluation studies published before 2015, when most of the ACF-OPRE studies took place, had significantly smaller effects (d = 0.033, k = 24, p < 0.152) than those published later (d = 0.197, k = 8, p < 0.001; Q = 11.5, p < 0.001). Although studies that employed TOT analyses (d = 0.155, k = 5, ns) had somewhat larger effect sizes than studies with ITT analyses (d = 0.065, k = 27, p < 0.01), the difference was not statistically significant. Programs that treated married and unmarried couples together (d = 0.147, k = 7, p < 0.01) had larger effects than programs targeting just unmarried couples (d = −0.013, k = 9, p = 0.772; Q = 6.0, p < 0.05), but not statistically higher than programs targeting just married couples (d = 0.091, k = 16, p = 0.003; Q = 0.7, p = 0.415). Effect sizes for moderate-dosage programs (9–19 hours; d = 0.168, k = 9, p < 0.01) were larger than for high-dosage programs (20 + hours; d = 0.054, k = 21, p < 0.05), but not quite statistically different (Q = 3.3, p = 0.069). Finally, CRE + programs (relationship education that included coparenting/parenting education; d = 0.076, k = 24, p < 0.01) did not have significantly larger effect sizes than CRE programs without this added content (d = 0.066, k = 8, ns; Q = 0.4, ns).

Results of 1-group/pre-post studies are subject to significant sources of bias (Reichardt, 2019), but we identified 12 of these studies and they do address our research question. However, to avoid distracting readers from the results of the more rigorous control-group studies, we present the results separately in online supplemental appendix S2.

Discussion

An important development in the CRE field over the past 15 years is that researchers have looked systemically beyond how these programs influence couple relationship outcomes to how they subsequently influence coparenting, parenting, and child outcomes, consistent with family systems theory and a large body of research on the effects of parental discord on child development (Coln et al., 2013; Cummings & Davies, 2002; van Eldik et al., 2020). Our meta-analysis reviewed this growing body of evaluation research. Among control-group studies, we found significant but small average effects of CRE programs on coparenting and child well-being/behavior, but nonsignificant effects on parenting.

We acknowledge that the inclusion/exclusion criteria employed for this meta-analysis may bias findings. For instance, studies that include our targeted outcomes may employ different curricula than studies that do not include these outcomes, although most of the included studies used common curricula (e.g., PREP-based programs, Sound Marital House, Together We Can, Family Foundations). Also, our focus was on couple programs rather than the broader set of relationship literacy programs for youth and young adults. Readers should be careful not to overgeneralize the effects seen in this subset of CRE studies to CRE programs in general.

These treatment-to-no-treatment effect sizes for coparenting, parenting, and child well-being/behavior are smaller than the moderate-size effects on couple relationships documented by several meta-analytic studies (Blanchard et al., 2009; Fawcett et al., 2010; Hawkins et al., 2008; Lucier-Greer & Adler-Baeder, 2012; Pinquart & Teubert, 2010). And note that the coparenting effect size in our study is smaller than observed in a meta-analysis focused exclusively on coparenting programs (d = 0.21; Nunes et al., 2021) A number of factors lead us to expect small effect sizes for this set of CRE programs. First, a quarter of the programs analyzed in this meta-analysis did not include specific curriculum on coparenting or parenting. Hence, any effects on these outcomes would be indirect, through improved couple functioning; indirect effects will be weaker than direct effects. Second, most of these studies were conducted in field conditions, not in laboratories with carefully controlled conditions. Field studies of couple interventions usually yield smaller effect sizes than laboratory studies (Bradbury & Bodenmann, 2020). Similarly, program attrition rates are usually higher in field studies than in laboratory studies (e.g., Moore et al., 2012), so many participants do not receive the intended treatment dosage. Third, some couples (especially unmarried couples) who participate in these programs are unsure about the prospects of their current relationship; their participation may be focused on deciding if the relationship has future potential or is too unhealthy to continue. Positive breakups—ending unhealthy relationships with poor prospects—should be seen as a successful outcome of CRE, albeit one that registers statistically as lower scores on outcomes. Finally, most previous meta-analytic studies of CRE programs synthesized studies with middle-class, well-educated samples. In contrast, this meta-analysis was dominated by studies with diverse, lower-income samples. The stressful conditions of these participants’ lives clearly work against maintenance of learned skills (Bradbury & Bodenmann, 2020; Halpern-Meekin, 2019), especially for the most disadvantaged. This is one reason why critics of the policy have predicted that the programs will not be successful (Randles, 2017). Given these realities facing CRE program interventions, we would expect effect sizes to be smaller than in previous studies.

Still, it is helpful to place the effect sizes observed in this study in a broader context by comparing these effects to those of other kinds of family-strengthening programs that receive support from federal policy initiatives. For instance, a rigorous impact evaluation of the well-known Head Start program found that early moderate impacts on cognitive, social, and health outcomes for Head Start children mostly dissipated by the 3rd-grade follow-up (Puma et al., 2012). The few positive effects that were found were generally between d = 0.10 and 0.15, and several negative effects in the same range were observed. Similarly, a rigorous, major impact evaluation of home visiting programs to support low-income new mothers and improve child well-being found few significant impacts at the 18-month follow-up on maternal health, economic self-sufficiency, or child health and development, although there were small, positive impacts on preventing maternal experiences with intimate partner violence and on some parenting outcomes, with effects generally between d = 0.08 and 0.11 (Michalopoulos et al., 2019). Also, a meta-analysis of responsible fatherhood programs for nonresident fathers found an overall effect size of d = 0.10 (Holmes et al., 2020). Effect sizes of CRE programs on coparenting, parenting, and child well-being are similar to those for other important family strengthening programs that target these outcomes more directly.

Note, however, that we observed some important variation in effect sizes in our moderator analyses and variation is often more informative than central tendencies. For instance, there was a significant difference in program effects on coparenting outcomes between the set of ACF-OPRE studies (d = 0.025), which contributed 61% of the total effects in this meta-analysis, and studies conducted outside the purview of ACF-OPRE (d = 0.200). There are likely both methodological and programmatic differences between these two groups of studies that explain the differences but are difficult to tease out. One possibility is that two of three ACF-OPRE studies (BSF and SHM, from which 16 studies came) led out early on in offering CRE to lower income, diverse couples and had a steep learning curve. Most of the non–ACF-OPRE studies in our meta-analysis came later and may have built on the learning curve from earlier programs. (There were explicit ACF efforts to communicate lessons learned to ongoing programs.) Studies conducted earlier rather than later had significantly smaller effects (d = 0.033 vs. d = 0.197) that mirror the difference between OPRE and non-OPRE studies. Optimists could interpret this pattern of results as evidence that programs are getting better at affecting coparenting outcomes. Those earlier studies, however, may have had more disadvantaged participants, on average, and their stressed lives may have restricted their ability to benefit from the programs.

Nevertheless, if the ultimate value of CRE programs is measured by improved lives for children, then these programs will need to strengthen their effects on coparenting, parenting, and child outcomes. Our moderator analyses may provide a few clues on how program administrators might strengthen the effects of CRE programs on coparenting, parenting, and child well-being. Note that studies of programs that included both married and unmarried couples showed significantly stronger effects (d = 0.147) than studies of programs with just unmarried participants (d = −0.013). Some have speculated that mixed-status groups may help unmarried couples gain greater hope and find role models for their relationship aspirations while married couples better sense their relationship success and progress through participation with unmarried couples (Halpern-Meekin, 2019). And it may be especially helpful for unmarried fathers in these groups to see other men who are “digging in” in to strengthen their families.

Note too that higher dosage programs (d = 0.054) provide no significant advantage over moderate dosage programs (d = 0.168) (the small difference is not quite statistically significant). All ACF-OPRE programs and most of the early-stage programs had more intensive curricula, but the evidence from our study does not support the need for higher dosage, a finding consistent with a broader meta-analytic study looking at the effects of CRE on couple outcomes (Hawkins et al., 2012). Perhaps resources that go into more intensive curricula could be retasked for some brief booster sessions, which CRE scholars have encouraged (Halpern-Meekin, 2019).

The fact that the coparenting outcome was significant but the parenting outcome was not might suggest that CRE programs are better equipped to focus on couple outcomes rather than on parenting outcomes (or that participating couples are more attuned to couple issues). Moreover, effects on child well-being/behavior, small as they are, may flow through better couple relationships or improved coparenting practices rather than improved parenting practices. This is speculative, however, and primary studies that explicitly tested possible pathways between intervention effects and the outcomes targeted in this meta-analysis suggest various pathways (Feinberg & Jones, 2018; Pruett et al., 2019; Sterrett-Hong et al., 2018; Zemp et al., 2016). Feinberg and Jones (2018) found that child behavior problems were impacted by a set of changes in both coparenting and parenting outcomes. Pruett et al., 2019 found a significant pathway from reduced couple conflict to reduced harsh parenting then to reduced child behavior problems. Zemp and colleagues (2016) found significant direct paths between improved couple relationships and child behavior problems (without exploring coparenting specifically). Similarly, Sterrett-Hong and colleagues (2018) found significant direct paths between decreased couple conflict and improved child mental health (without exploring coparenting). Our moderator analyses found no difference in effects between programs that included coparenting/parenting content and those that stayed focused on the couple relationship. Again, this might suggest that effects on children can flow simply through improved couple functioning. Our findings, however, should not be taken as challenging other possible pathways through coparenting and parenting practices. Van Elkik and colleagues (2020) have documented many well-tested direct pathways between couple relationships and child well-being, including reductions in parental conflict and improved couple relationships. Going forward, CRE researchers should seek to understand specific (and multiple) pathways for how CRE and CRE + impact children’s well-being. But CRE programs without direct coparenting and parenting curriculum may still have the ability to improve children’s well-being/behavior.

Finally, the findings of our meta-analysis take on greater significance in light of federal policy to provide CRE to disadvantaged couples. While improving the economic circumstances of these couples’ lives is important to reducing daily stress, improving “soft” skills also may help them achieve their aspirations of stable, healthy families and positive child development. Halpern-Meekin (2019), who has studied in depth couples participating in these kinds of programs, found that the primary motivation for their participation was to reduce couple conflict so they can be better parents and provide a more stable and nurturing environment for their children. She points out how small shifts in microlevel interactions, such as learning to take a “time out” to deescalate potential conflict, “can fundamentally change the couple’s day-to-day experience of their relationship—whether it is primarily a source of comfort or conflict” (p. 167). Still, this meta-analytic study documents only small effects of CRE on coparenting, parenting, and child outcomes. And while the trajectory of this work appears to be headed upward, with somewhat stronger program effects apparent in more recent studies, these programs will need to improve their interventions to better achieve the important policy goal of improving children’s well-being.

References

*= Control-group studies included in meta-analysis.

*Adler‐Baeder, F., Garneau, C., Vaughn, B., McGill, J., Harcourt, K. T., Ketring, S., & Smith, T. (2018). The effects of mother participation in relationship education on coparenting, parenting, and child social competence: Modeling spillover effects for low‐income minority preschool children. Family Process, 57, 113–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12267.

*Amato, P. (2014). Does social and economic disadvantage moderate the effects of relationship education on unwed couples? An analysis of data from the 15-month Building Strong Families evaluation. Family Relations, 63, 343–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12069.

Arnold, L. S., & Beelman, A. (2019). The effects of relationship education in low-income couples: A meta-analysis of randomized-controlled evaluation studies. Family Relations, 68, 22–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12325.

Blanchard, V. L., Hawkins, A. J., Baldwin, S. A., & Fawcett, E. B. (2009). Investigating the effects of marriage and relationship education on couples’ communication skills: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Family Psychology, 23, 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015211.

Bon, P. R. D., & Rachinger, H. (2017). Estimate dependence in meta-analysis: A generalized-weights solution to sample overlap. Study retrieved June, 10, 2020 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326019523_Estimate_Dependence_in_Meta-Analysis_A_Generalized-Weights_Solution_to_Sample_Overlap.

Borenstein, M. (2019). Common mistakes in meta-analysis and how to avoid them. Englewood, NJ: Biostat.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. West Sussex, UK: Wiley.

Bradbury, T. N., & Bodenmann, G. (2020). Interventions for couples. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 16, 199–123. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-071519-020546.

Brown, S. L. (2010). Marriage and child well-being: Research and policy perspectives. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 72, 1059–1077. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00750.x.

Carlson, M. J., & McLanahan, S. S. (2006). Strengthening unmarried families: Could enhancing couple relationships also improve parenting? Social Service Review, 80, 297–321. https://doi.org/10.1086/503123.

Christopher, C., Umemura, T., Mann, T., Jacobvitz, D., & Hazen, N. (2015). Marital quality over the transition to parenthood as a predictor of co-parenting. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 3636–3651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0172-0.

Coln, K. L., Jordan, S. S., & Mercer, S. H. (2013). A unified model exploring parenting practices as mediators of marital conflict and children’s adjustment. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 44, 419–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-012-0336-8.

Cowan, P. A., & Cowan, C. P. (2014). Controversies in couple relationship education (CRE): Overlooked evidence and implications for research and policy. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 20, 361–383. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000025.

*Cowan, C. P., Cowan, P. A., & Barry, J. (2011). Couples’ groups for parents of preschoolers: Ten-year outcomes of a randomized trial. Journal of Family Psychology, 25, 240–250. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023003.

*Cowan, P. A., Cowan, C. P., Pruett, M. K., Pruett, K., & Wong, J. J. (2009). Promoting fathers’ engagement with children: Preventive interventions for low-income families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 663–679. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00625.x.

*Cox, R., & Shirer, K. (2009). Caring for my family: A pilot study of a relationship and marriage education program for low-income unmarried parents. Journal of Couple & Relationship Therapy, 8, 343–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332690903246127.

Cummings, E. M., & Davies, P. T. (2002). Effects of marital conflict on children: Recent advances and emerging themes in process-oriented research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 43, 31–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00003.

*Doss, B. D., Cicila, L. N., Hsueh, A. C., Morrison, K. R., & Carhart, K. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of brief co-parenting and relationship interventions during the transition to parenthood. Journal of Family Psychology, 28, 483–494. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037311.

*Doss, B. D., Roddy, M. K., Llabre, M. M., Salivar, E. G., & Jensen-Doss, A. (2020). Improvements in coparenting conflict and child adjustment following an online program for relationship distress. Journal of Family Psychology, 34, 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037311.

Fawcett, E. B., Hawkins, A. J., Blanchard, V. L., & Carroll, J. S. (2010). Do premarital education programs really work? A meta-analytic study. Family Relations, 59, 232–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00598.x.

*Feinberg, M. E., Boring, J., Le, Y., Hostetler, M. L., Karre, J., Irvin, J., & Jones, D. E. (2020). Supporting military family resilience at the transition to parenthood: A randomized pilot trial of an online version of Family Foundations. Family Relations, 69, 109–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12415.

*Feinberg, M. E., & Jones, D. E. (2018). Experimental support for a family systems approach to child development: Multiple mediators of intervention effects across the transition to parenthood. Couple and Family Psychology, 7, 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1037/cfp0000100.

*Feinberg, M. E., Jones, D. E., Hostetler, M. L., Roettger, M. E., Paul, I. M., & Ehrenthal, D. B. (2016). Couple-focused prevention at the transition to parenthood, a randomized trial: Effects on co-parenting, parenting, family violence, and parent and child adjustment. Prevention Science, 17, 751–764. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0674-z.

*Feinberg, M. E., Jones, D. E., & Kan, M. L. (2010). Effects of family foundations on parents and children: 3.5 years after baseline. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 532–542. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020837.

*Feinberg, M. E., Jones, D. E., Roettger, M. E., Solmeyer, A., & Hostetler, M. L. (2014). Long‐term follow‐up of a randomized trial of family foundations: Effects on children’s emotional, behavioral, and school adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology, 28, 821. https://doi-org.erl.lib.byu.edu/10.1037/fam0000037.

*Feinberg, M. E., Roettger, M., Jones, D. E., Paul, I. M., & Kan, M. L. (2015). Effects of a psychosocial couple-based prevention program on adverse birth outcomes. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 19, 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-014-1500-5.

Halpern-Meekin, S. (2019). Social poverty: Low-income parents and the struggle for family and community ties. New York University.

Hawkins, A. J. (2019, September 3). Are federally supported relationship education programs for lower income individuals and couples working? A review of evaluation research. American Enterprise Institute. Retrieved May 7, 2020, from https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/are-federally-supported-relationship-education-programs-for-lower-income-individuals-and-couples-working-a-review-of-evaluation-research/.

Hawkins, A. J., Allen, S. E., & Yang, C. (2017). How does couple and relationship education affect relationship hope? An intervention-process study with lower income couples. Family Relations, 66, 441–452. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12268.

Hawkins, A. J., Blanchard, V. L., Baldwin, S. A., & Fawcett, E. B. (2008). Does marriage and relationship education work? A meta-analytic study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 723–734. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012584.

Hawkins, A. J., & Erickson, S. E. (2015). Is couple and relationship education effective for lower income participants? A meta-analytic study. Journal of Family Psychology, 29, 59–68. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000045.

Hawkins, A. J., Hokanson, S., Loveridge, E., Milius, E., Crawford, M. D., Booth, M., & Pollard, B. (2021). How effective are ACF-funded couple relationship education programs? A meta-analytic study. Family Process. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12739.

*Hawkins, A. J., Lovejoy, K. R., Holmes, E. K., Blanchard, V. L., & Fawcett, E. (2008). Increasing fathers’ involvement in child care with a couple-focused intervention during the transition to parenthood. Family Relations, 57, 9–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2007.00482.x.

Hawkins, A. J., Stanley, S. M., Blanchard, V. L., & Albright, M. (2012). Exploring programmatic moderators of the effectiveness of marriage and relationship education programs: A meta-analytic study. Behavior Therapy, 43, 77–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2010.12.006.

Holmes, E. K., Egginton, B. M., Hawkins, A. J., Robbins, N., & Shafer, K. (2020). Do responsible fatherhood programs work? A meta-analytic study. Family Relations. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12435.

*Jones, D. E., Feinberg, M. E., Hostetler, M. L., Roettger, M. E., Paul, I. M., & Ehrenthal, D. B. (2018). Family and child outcomes 2 years after a transition to parenthood intervention. Family Relations, 67, 270–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12309.

Jackson, D., & Turner, R. (2017). Power analysis for random-effects meta-analysis. Research Synthesis Methods, 8, 290–302. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1240.

*Kirkland, C. L., Skuban, E. M., Adler-Baeder, F., Ketring, S. A., Bradford, A., Smith, T., & Lucier-Greer, M. (2011). Effects of relationship/marriage education on co-parenting and children’s social skills: Examining rural minority parents’ experiences. Early Childhood Research & Practice, 13(2), n2.

Knopp, K., Rhoades, G. K., Allen, E. S., Parsons, A., Ritchie, L. L., Markman, H. J., & Stanley, S. M. (2017). Within- and between-family associations of marital functioning and child well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 79, 451–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12373.

*Lavner, J. A., Barton, A. W., & Beach, S. R. H. (2019). Improving couples’ relationship functioning leads to improved coparenting: A randomized controlled trial with rural African American couples. Behavior Therapy, 56, 1016–1029. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2018.12.006.

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

*Lowenstein, A. E., Altman, A., Chou, P. M., Faucetta, K., Greeney, A., Gubits, D., Harris, J., Hsueh, J., Lundquist, L., Michalopoulos, C., & Nguyen, V. Q. (2014). A family-strengthening program for low-income families: Final impacts from the Supporting Healthy Marriage evaluation, technical supplement. OPRE Report 2014-09B. Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Lucier‐Greer, M., & Adler‐Baeder, F. (2012). Does couple and relationship education work for individuals in stepfamilies? A meta‐analytic study. Family Relations, 61, 756–769. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00728.x.

*Lucier‐Greer, M., Adler‐Baeder, F., Harcourt, K. T., & Gregson, K. D. (2014). Relationship education for stepcouples reporting relationship instability—evaluation of the Smart Steps: Embrace the Journey curriculum. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 40, 454–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmft.12069.

McAllister, S., Duncan, S. F., & Hawkins, A. J. (2012). Examining the early evidence for self-directed marriage and relationship education: A meta-analytic study. Family Relations, 61, 742–755. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2012.00736.x.

Michalopoulos, C., Faucetta, K., Hill, C. J., Portilla, X. A., Burrell, L., Lee, H., Duggan, A., & Knox, V. (2019). Impacts on family outcomes of evidence-based early childhood home visiting: Results from the Mother and Infant Home Visiting Program Evaluation. OPRE Report 2019-07. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

*Miller-Graff, L., Cummings, E. M., & Bergman, K. N. (2016). Effects of a brief psychoeducational intervention for family conflict: Constructive conflict, emotional insecurity and child adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44, 1399–1410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-015-0102-z.

*Moore, Q., Avellar, S., Patnaik, A., Covington, R., & Wu, A. (2018). Parents and Children Together: Effects of two healthy marriage programs for low-income couples. OPRE Report Number 2018-58. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

*Moore, Q., Wood, R. G., Clarkwest, A., Killewald, A., & Monahan, S. (2012). The long-term effects of Building Strong Families: A relationship skills education program for unmarried parents, technical supplement. OPRE Report 2012-28C. Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). A roadmap to reducing child poverty. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25246.

Nunes, C. E., de Roten, Y., El Ghaziri, N., Favez, N., & b Darwiche, J. (2021). Co-parenting programs: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Family Relations, 70, 759–776. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12438.

Pinquart, M., & Teubert, D. (2010). A meta-analytic study of couple interventions during the transition to parenthood. Family Relations, 59, 221–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2010.00597.x.

*Pruett, M. K., Cowan, P. A., Cowan, C. P., Gillette, P., & Pruett, K. D. (2019). Supporting father involvement: An intervention with community and child welfare–referred couples. Family Relations, 68, 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12352.

Puma, M., Bell, S., Cook, R., Heid, C., Broene, P., Jenkins, F., Mashburn, A., & Downer, J. (2012). Third grade follow-up to the Head Start impact study final report, executive summary. OPRE Report # 2012-45b.Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

Randles, J. M. (2017). Proposing prosperity: Marriage education policy and inequality in America. New York: Columbia University.

*Rhoades, G. K. (2015). The effectiveness of the Within Our Reach relationship education program for couples: Findings from a federal randomized trial. Family Process, 54, 672–685. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12148.

*Rienks, S. L., Wadsworth, M. E., Markman, H. J., Einhorn, L., & Etter, E. M. (2011). Father involvement in urban low‐income fathers: Baseline associations and changes resulting from preventive intervention. Family Relations, 60, 191–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741‐3729.2010.00642.x.

Reeves, R. V. (2014, February 13). How to save marriage in America. Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/how-to-save-marriage-in-america/.

Reichart, C. S. (2019). Quasi-experimentation: A guide to design and analysis. New York: Guilford.

Simpson, D. M., Leonhardt, N. D., & Hawkins, A. J. (2018). Learning about love: A meta-analytic study of individually oriented relationship education programs for adolescents and emerging adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47, 477–489. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0725-1.

*Solmeyer, A. R., Feinberg, M. E., Coffman, D. L., & Jones, D. E. (2014). The effects of the Family Foundations Prevention Program on co-parenting and child adjustment: A mediation analysis. Prevention Science, 15, 213–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-013-0366-x.

Stanley, S. M., Amato, P. R., Johnson, C. A., & Markman, H. J. (2006). Premarital education, marriage quality, and marital stability: Findings from a large, random household survey. Journal of Family Psychology, 20, 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.117.

Sterrett-Hong, E., Antle, B., Nalley, B. & Adams, M. (2018). Changes in couple relationship dynamics among low-income parents in a relationship education program are associated with decreases in their children’s mental health symptoms. Children, 5, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/children5070090.

van Eldik, W. M., de Haan, A., Parry, L. Q., Davies, P. T., Luijk, M. P. C. M., Arends, L. R., & Prinzie, P. (2020). The interparental relationship: Meta-analytic associations with children’ aladjustment ad responses to interparental conflict. Psychological Bulletin, 146, 553–594. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000223.

*Williamson, H. C., Altman, N., Hsueh, J., & Bradbury, T. N. (2016). Effects of relationship education on couple communication and satisfaction: A randomized controlled trial with low-income couples. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84, 156–166. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000056.

*Wood, R. G., Moore, Q., Clarkwest, A., & Killewald, A. (2014). The long‐term effects of building strong families: A program for unmarried parents. Journal of Marriage and Family, 76, 446–463. https://doi-org.erl.lib.byu.edu/10.1111/jomf.12094.

*Zemp, M., Milek, A., Cummings, E. M., Cina, A., & Bodenmann, G. (2016). How couple- and parenting-focused programs affect child behavioral problems: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 798–810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0260-1.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Eden Loveridge, Emily Milius, and Misha Duncan for their assistance in coding studies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hawkins, A.J., Hill, M.S., Eliason, S.A. et al. Do Couple Relationship Education Programs Affect Coparenting, Parenting, and Child Outcomes? A Meta-Analytic Study. J Child Fam Stud 31, 588–598 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02229-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02229-w