Abstract

While parent training often focuses on teaching parents of children with Autism Sepctrum Disorders (ASD) specific skills to address their child’s problem behavior, it has often overlooked factors related to parents’ own mental health and well-being, such as how they think and feel about their child’s behavior and their parenting. The purpose of this study was to examine the impact of positive family intervention (PFI), a parent training program which combines cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) with family based positive behavior support (PBS), on parents’ cognitions and children’s problem behavior for families of children with ASD. A nonconcurrent multiple baseline design across three mothers was used to examine the impact of PFI on parent-reported stress, self-efficacy, attributions, rational and irrational beliefs, pessimism, and ratings of child behavior problems. Each mother received eight weekly 90-minute PFI sessions without the child present. Findings demonstrated significant decreases in parent ratings of problem behavior as well as observed child problem behavior for all three families, though visual analysis showed only modest change in parent-reported problem behavior for one of those three mothers, and direct observation data was only collected pre- and post-intervention. Two of the three mothers reported significant decreases in dysfunctional child- and parent-causal attributions, irrational beliefs, and pessimistic thoughts. In addition, one of those two mothers reported improvements in parental stress and self-efficacy. This study suggests that there may be benefits to incorporating CBT with PBS in terms of affecting parents’ perceptions of their children and themselves. Factors potentially contributing to or limiting the effectiveness of PFI for each participant are discussed.

Highlights

-

Child behavioral problems significantly decreased as a result of Positive Family Intervention (PFI).

-

PFI resulted in improved cognitions or attitudes for two of the three mothers of children with ASD.

-

Future research should identify which parents may benefit from adding parent–child coaching at home to parent-only sessions.

-

Integrating cognitive-behavioral therapy with positive behavior support may help parents to implement behavioral interventions and cope with difficult situations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Children with developmental disabilities (DD) such as autism spectrum disorders (ASD) often exhibit a variety of problem behaviors including aggression, self-injury, tantrums, property destruction, and repetitive behaviors (e.g., Horner et al. 2002), which are a major detriment to quality of life for children with ASD and their families (Carr 2007). A significant body of research demonstrates that problem behaviors exhibited by individuals with ASD have been effectively treated using family-based positive behavior support (PBS) (e.g., Clarke et al. 1999; Lucyshyn et al. 2007, 2015), which involves the development of multi-component interventions, based on the results of a comprehensive functional assessment, to improve quality of life and reduce problem behaviors across multiple, naturalistic contexts. Family-based PBS extends beyond traditional behavioral parent training (BPT) by considering multiple theoretical perspectives, emphasizing interventions that are practical and ecologically valid, focusing on family goals and values, encouraging lifestyle enhancement, and incorporating multiple intervention components that emphasize prevention and skill development (Carr et al. 2002; Lucyshyn et al. 2002a, 2002b).

While previous research has demonstrated the efficacy of BPT (e.g., Bearss et al. 2015) and family-based PBS in reducing problem behaviors among youth with ASD, little attention has been devoted to those parents and families who do not successfully complete parent training programs or who are unable to implement behavioral interventions with fidelity (or at all) (Allen and Warzak 2000). Although 40–60% of parents of children with a variety of behavioral disorders drop out of treatment (e.g., Kazdin 1996), Durand and Rost (2005) found that only 3% of published studies on PBS included information on attrition, which may lead to underreporting potential barriers to successful parent training, thus impacting subsequent conclusions drawn from research on behavioral interventions. Further, since early research on parent training for children with ASD strongly emphasized addressing the child’s behaviors without much concern for other issues in the family, parental functioning continues to be an area that is neglected today in the parent training literature for youth with ASD and DD (Brookman-Frazee et al. 2006). Indeed, relatively few PBS or parent training studies have reported on parents’ thoughts (e.g., self-efficacy, attributions) and affect (e.g., parental stress) (Iadarola et al. 2018; Lucyshyn et al. 2018), and even fewer parent training studies have directly targeted parents’ thoughts and feelings. This is a glaring omission, given that Falk et al. (2014) concluded that, although child problem behaviors might relate to maternal stress, anxiety, and depression in mothers of children with ASD, “the core predictor [of child problem behaviors], and the main focus of any successful intervention, is maternal cognitions.” Therefore, there is a need for treatments that directly target parents’ attitudes/thoughts and feelings in the context of parent training. To date, only a few studies have explored parental attitudinal variables that can contribute to the success or failure of parent training, including parental attributions, parental pessimism, parental self-efficacy, and parental stress, each of which involves parents’ thoughts about themselves, their child, and/or the world.

Parental attributions for problem behavior include “child-causal” or child-responsible attributions (i.e., parents’ beliefs about their child’s own accountability for causing their problem behavior) and “parent-causal” attributions (i.e., parents’ beliefs about their own causal role in problem behavior). Both dysfunctional child- and parent-causal attributions have been shown to be significantly related to parent–child aggression, over-reactive discipline, and lax parenting in a normative sample (Snarr et al. 2009). In terms of child-causal attributions, parents of children without disabilities who attribute problem behavior to factors outside of their child’s control are less likely to use negative parenting practices than those who attribute problem behaviors to factors that are intentional, intrinsic and stable to the child (e.g., Snarr et al. 2009). However, a recent study found that parents of children with ASD were more likely than parents of neurotypical children to believe their children could not control their problem behavior, which predicted their use of more lax parenting than the parents in the control group, which in turn, was associated with higher levels of child problem behavior for the children with ASD (Berliner et al. 2020). Similarly, Hartley et al. (2013) found that parents whose children with ASD were more severely impaired were more likely to believe that their child could not control his/her behavior problems and attribute the child’s behavior problems to internal and stable characteristics. This suggests that some parents of children with ASD who exhibit challenging behavior may view their child’s behavior as incapable of changing which, in turn, may impact the parent’s motivation to implement or follow through with behavioral interventions. However, parent training may be capable of changing these attributions (Whittingham et al. 2009). In terms of parent-causal attributions, when mothers of children with ASD perceived themselves as having caused their child’s problem behaviors and their parent-related causes persisted over time, they reported lower levels of treatment acceptability (Choi and Kovshoff 2013). Therefore, it may be important for child- and parent-causal attributions to be addressed during the early phases of parent training (Choi and Kovshoff 2013).

Self-efficacy refers to the degree to which parents see themselves as competent and effective in their parenting role (Van den Hoffdakker et al. 2010). Parental self-efficacy is associated with parents’ adherence to behavioral interventions to address problem behavior, greater effectiveness of BPT in reducing children’s problem behavior, and parents’ ability to cope with problem behaviors and persist in implementing positive parenting practices in difficult situations (Jones and Prinz 2005; Solish and Perry 2008; Van den Hoffdakker et al. 2010). Parental self-efficacy has also been shown to mediate the relation between problem behaviors and anxiety and depression in mothers of children with ASD and moderate the effect of problem behaviors on anxiety in fathers of children with ASD (Hastings and Brown 2002). In fact, high parental self-efficacy may be considered a protective factor for parents of children with ASD, as it is related to lower levels of anxiety (Hastings and Brown 2002) and lower levels of parental stress (Coleman and Karraker 1998; Eisen et al. 2008). Further, Coleman and Karraker (1998) posited that parents with low self-efficacy may feel a lack of control over situations in which challenging behaviors are displayed, which may inhibit their ability to implement positive parenting strategies. Given that low parental self-efficacy has been related to low parental involvement and adherence, negative parenting practices, high parental anxiety, depression, and stress, it may be important to directly target parents’ self-efficacy in the context of parent training.

Parents of children with ASD experience significantly higher stress than parents of children without disabilities as well as parents of children with other disabilities, with child problem behavior accounting for a large proportion of the variance in parenting stress in parents of children with ASD (Dabrowska and Pisula 2010; Brei et al. 2015). Those parents who experience higher stress are more likely to drop out of interventions (Andra and Thomas 1998) and, for those who do not drop out, they still may struggle to implement or follow through with behavioral strategies and positive parenting practices more than parents with lower stress (Osborne et al. 2008; Schreibman 2000). Moreover, parental stress has been found to mediate the relation between problem behaviors in children with ASD and decreased parental self-efficacy (Rezendes and Scarpa 2011), suggesting that challenging behaviors may increase parental stress, which then reduces parental self-efficacy.

Pessimism, which refers to a negative expectation or perception of the future (Scheier and Carver 1993), is a broad construct that may include low self-efficacy, dysfunctional attributions, and parents’ other negative cognitions about themselves, their child, other people, the future, or their lives in general (e.g., things will never get better, other people are judging me). Parents of children with ASD and DD report lower levels of positive beliefs (Paczkowski and Baker 2008) as well as more negative or unhelpful beliefs that may influence their coping and adjustment to having a child with a disability (Tiba et al. 2012). These negative beliefs can be an obstacle to parent training, given that parental pessimism was found to be the strongest predictor of later child behavior problems in parents of children with DD (Durand 2001) and is a better predictor of parental stress, anxiety, and depression than child behavior problems in parents of children with ASD (Falk et al. 2014) and ID. Conversely, parental positive beliefs or optimism may serve as a protective factor for parents of children with DD who are faced with problem behavior (Durand 2001; Paczkowski and Baker 2008). Further, positive beliefs potentially helped parents in reducing their children’s challenging behaviors over time, which in turn reduced parental stress (Paczkowski and Baker 2008). Thus, it may be important for parent training to teach parents how to substitute pessimistic or negative/unhelpful beliefs with more optimistic or positive/helpful beliefs.

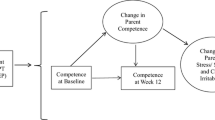

Taken together, the results of the aforementioned studies suggest that, in addition to teaching parents the skills to change their children’s behavior, it may also be necessary to teach them the skills to change their own thoughts or perceptions. In fact, a recent qualitative study conducted with parents of children with ASD that explored the variables that facilitate or serve as barriers to parental engagement in BPT found that parents may benefit from BPT that includes emotional support, such as evidence-based strategies to cope with the stress associated with parenting a child with ASD and challenging behavior (Raulston et al. 2019). As such, it may be beneficial to incorporate aspects of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) into parent training for the purpose of increasing parents’ positive/helpful beliefs and decreasing their negative/unhelpful beliefs. One such intervention was implemented by Durand et al. (2013), who explored the effectiveness of Positive Family Intervention (PFI), a parent training program that teaches parents to identify and address patterns in their child’s behavior (i.e., PBS) as well as identify and change their own thoughts and feelings through cognitive restructuring (i.e., CBT). Durand et al. (2013) compared the effectiveness of PFI to PBS alone. Although reductions in parental pessimism as well as observed and reported child problem behaviors were found in both groups, there was a significantly greater reduction in parent-reported problem behavior in parents who received PFI, which may reflect parents making more positive interpretations of their child’s behavior.

The results of that study hold promise for combining PBS with CBT to affect child behavior. However, as Durand et al. (2013) noted, their study did not identify the change(s) in parental cognitions that may account for the change in the children’s problem behavior. This may be due, in part, to the measures used; although no significant difference in parental pessimism was found between the PFI and PBS groups following intervention, this may be due to the use of the Questionnaire on Resources and Stress—Short Form (QRS-SF), which only reflects how a parent views his or her child’s future in general rather than how parents perceive their ability to change their children’s behaviors in specific situations (Durand et al. 2013). The researchers did not directly measure other constructs that may comprise pessimism, affect pessimism, or be related to pessimism, such as parental stress, self-efficacy, dysfunctional attributions, or more general negative and unhelpful beliefs. Therefore, it may be beneficial to study the effects of PFI on these specific parental attitudinal factors, which is the focus of the present study. Specifically, we hypothesized that PFI would result in: (1) a decrease in parental stress, (2) a decrease in dysfunctional child- and parent-causal attributions, (3) an increase in parental self-efficacy, (4) an increase in parent rational beliefs and decrease in parent irrational/unhelpful beliefs, (5) a decrease in parents’ pessimistic thoughts, and (6) a decrease in children’s reported and observed problem behavior.

Method

Participants

Three mothers who had a child diagnosed with ASD between the ages of 3 and 6 were recruited from schools and agencies that serve children with ASD, from a listserv and Facebook group for parents of children with ASD in suburbs of XX City, and from local assessment clinics and testing centers. Mothers were included in the present study if: (a) their child met DSM-IV criteria for Autistic Disorder or Pervasive Developmental Disorder—Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS) or DSM-V criteria for Autism Spectrum Disorder as documented by a licensed psychologist or psychiatrist; (b) their child displayed severe problem behavior as measured by a score of ≤20 on the General Maladaptive Index (GMI) of the Scales of Independent Behavior—Revised (SIB-R) (Bruininks et al. 1996); (c) the mothers obtained a score that was above the 85th percentile on the Difficult Child subscale of the Parenting Stress Index (PSI-4-SF); (d) the mothers obtained a score that was at least one standard deviation above the mean on either the Child-Responsible or Parent-Causal subscale of the Parent Cognition Scale (PCS), as reported by Snarr et al. (2009); (e) the mothers obtained a score that was in the “high” or “very high” ranges on the irrational beliefs subscale of the Parent Rational and Irrational Beliefs Scale (P-RIBS), as reported by Gavita et al. (2011); and (f) their child resided at home with his or her family. Mothers were excluded from the study if they were presently enrolled in a parent training program or had received BPT in the past six months, or if their child was on an unstable dose of medication. Screening of potential participants lasted almost three months. Among the 14 mothers screened for eligibility, 10 were excluded for failing to meet inclusion criteria. One participant improved during baseline and was therefore excluded from the study. Mothers who participated in and completed the present study received PFI free-of-charge and, after the study ended, were entered into a raffle to win an $150 Visa gift card. The three mothers accepted into the study completed all eight sessions without any attrition. These mothers were: (1) Jen, a 37-year-old Caucasian mother whose 4-year-old son, Noah, was diagnosed with PDD-NOS, (2) Marisa, a 26-year-old Ecuadorian-American mother whose 5-year-old son, Andrew, was diagnosed with ASD, and (3) Sarah, a 43-year-old Caucasian mother whose 6-year-old son, Jacob, was diagnosed with ASD. All three mothers were married. Noah and Andrew attended a special program for children with ASD and received special education services through an IEP. Jacob attended a general education classroom and received related services (speech) through an IEP.

Procedure

Once all participants were screened and identified, pre-intervention behavioral observations were conducted in each child’s home. Subsequently, during the baseline phase, all six questionnaires were administered to each of the three participants once per week prior to the start of intervention. These measures were administered only to the primary caregiver of each family (in each instance, the mother). Data collection on each of these six measures continued to occur once weekly throughout the PFI condition. The six questionnaires were administered in the order that the measures are listed below (the SIB-R, PSOC, PCS, PSI-4-SF, Thoughts Quiz, and P-RIBS).

The PFI condition in the present study replicated the intervention condition outlined in Durand et al. (2013) and followed the treatment manual Helping Parents with Challenging Children: Positive Family Intervention Facilitator Guide (Durand and Hieneman 2008). PFI involved eight individually administered weekly sessions, each lasting 90 min. An additional 30 min was provided prior to each session to allow participants to complete the six outcome measures. All PFI sessions were conducted by the first author, who was a doctoral candidate and a NYS certified school psychologist with a master’s degree and background in PBS and CBT. The sessions occurred individually with the mothers in the absence of children. All sessions were video-recorded for purposes of supervision and to assess fidelity.

In addition to teaching the principles and procedures of PBS (i.e., how to conduct a functional behavior assessment [FBA] and develop intervention strategies based on the results of the FBA), PFI also focused on teaching parents the basic principles and procedures of CBT (i.e., how to identify patterns in their own thoughts and feelings and then cognitively restructure those thoughts). As part of CBT, parents practiced identifying their thoughts related to their child’s behavior (e.g., “I have little or no control over this situation,” “This will never get better”) as well as strategies for perceiving these situations in a more helpful or productive way. Sessions occurred in the specific sequence outlined by Durand et al. (2013). Specifically, Session 1 focused on providing an introduction and setting goals as well as identifying situations and associated “self-talk” (i.e., parents’ thoughts). Session 2 focused on gathering FBA data on antecedents to and consequences of children’s challenging behavior as well as determining the consequences of the mothers’ beliefs. Session 3 focused on analyzing the FBA data regarding children’s challenging behavior to identify patterns, brainstorming intervention strategies based on that data, and disputing/challenging parents’ negative self-talk. Session 4 focused on selecting Prevention Strategies to address children’s challenging behavior and using distraction to interrupt parents’ negative thinking. Session 5 focused on selecting Management Strategies (consequence-based interventions) to manage children’s challenging behavior and substituting parents’ pessimistic thoughts with more positive, productive thoughts. Session 6 focused on selecting Replacement Strategies (teaching skills) to replace children’s challenging behaviors with appropriate alternatives as well as practicing how to recognize and modify parents’ negative self-talk. Session 7 focused on parents implementing the Prevention, Replacement, and Management strategies with their children as well as continued practice of skills to recognize and modify parents’ self-talk. Finally, Session 8 focused on monitoring the results and maintaining positive changes in self-talk.

All of the sessions followed the same format in which the therapist (a) reviewed homework that was assigned in the previous section, (b) introduced each new PBS and CBT concept by presenting a rationale and description of the features or steps (e.g., why it is important to analyze patterns related to what happens before and after the child’s problem behavior, and how to do so), (c) provided examples (e.g., a standard case example of “Ben’s” patterns, along with additional individualized examples provided by the therapist as needed), (d) offered an opportunity for the parent to apply the concept with her child’s problem behavior, and (e) assigned homework so that the parent could practice the concept and strategies with her child between sessions (Durand et al. 2013). Although there were sample scripts for how to introduce the concept/skill and rationale and a standard ongoing case example (“Ben”), the PFI process was individualized to each parent in that most of the strategies are relatively general or broad and have a variety of ways that they can be applied. For example, there are many different ways that a parent could “reward a child’s positive behaviors” and/or “consider her own-self talk” in the situations that come up in between session and in the sessions themselves. Further, the therapist made adjustments to how skills were explained and/or applied and provided additional case examples, questions, explanations, and suggestions based on how the parent responded to the intervention. After all eight PFI sessions had been conducted at XX University, a post-intervention behavioral observation was conducted in the home for each child.

Experimental design

A nonconcurrent multiple baseline design (Hersen and Barlow 1976) across the three participants was used to examine the impact of PFI on the five parent variables and child behavior problems. Data were collected on each of the following dependent variables at the start of each session, and observed child behavior during pre- and post-intervention observations.

Measures

Scales of Independent Behavior—Revised (SIB-R)

The SIB-R (Bruininks et al. 1996) is a norm-referenced measure of adaptive functioning, independence, and problem behavior (Bruininks et al. 1996). Only the section of the SIB-R which measures problem behaviors was used in the present study and was administered in the self-report format. This section yields a General Maladaptive Behavior Index (GMI), which is a composite of eight items in three domains: (1) internalized maladaptive behavior, (2) asocial maladaptive behavior, and (3) externalized maladaptive behavior. Ratings of the child’s behavior are classified on the GMI as: very serious (≤–41), serious (–40 to –31), moderately serious (–30 to –21), marginally serious (–20 to –11) and normal (≥–10). The SIB-R demonstrates adequate test-retest reliability, interrater reliability, construct validity, and criterion validity (Bruininks et al. 1996).

Parenting Sense of Competence Scale (PSOC)

The PSOC (Johnston and Mash 1989) is a 17-item self-report scale that measures: (1) satisfaction in the parenting role, (2) parental self-efficacy, and (3) an interest in parenting. Parents are required to rate each item using a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (6), with higher scores indicating higher parenting satisfaction. The PSOC demonstrates strong psychometric properties (Johnston and Mash 1989; Ohan et al. 2000).

Parent Cognition Scale (PCS)

The PCS (Snarr et al. 2009) is a 30-item self-report instrument that measures the extent to which parents endorse dysfunctional child-responsible attributions and parent-causal attributions with regard to their children’s problem behaviors. Parents are required to rate potential causes of their child’s problem behaviors using a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from always true (1) to never true (6). Items are reverse-scored so that higher scores reflect greater endorsement of dysfunctional cognitions. Snarr et al. (2009) report adequate internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and convergent and discriminant validity.

Parenting Stress Index, 4th Edition—Short Form (PSI-4-SF)

The PSI-4-SF (Abidin 2012) is a 36-item self-report instrument used to measure the level of stress associated with the parenting role in three domains: (1) Parental Distress, (2) Parent–Child Dysfunctional Interaction, and (3) Difficult Child. These three subscales are combined to yield a Total Stress index. Parents are required to rate each item using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Higher scores indicate higher levels of stress. The PFI has good internal consistency and test-retest reliabilities (Abidin 2012) and good predictive, convergent, and discriminant validity (Haskett et al. 2006).

Thoughts Quiz

The Thoughts Quiz (Durand and Hieneman 2008) is a parent self-report measure containing 13 pessimistic or unhelpful beliefs (e.g., “In this situation, others are judging my child negatively”). Parents are required to rate each statement using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Higher scores indicate a higher degree of parental pessimism. Psychometric properties have not yet been examined for this measure.

Parent Rational and Irrational Beliefs Scale (P-RIBS)

The P-RIBS (Gavita et al. 2011), a 24-item self-report instrument designed to identify parents’ cognitions that are responsible for dysregulated affect and behavior, reflects evaluative cognitive processes regarding child behavior and parent-role. The P-RIBS is divided into two subscales supported by factor analysis: Rational Beliefs (RBs) and Irrational Beliefs (IBs), as well as a third subscale, Global Evaluation (GE), which emerged separately from factor analysis. Each item is rated by the parent using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Higher total scores indicate higher levels of irrational beliefs. The authors reported acceptable test-retest reliability, internal consistency, and concurrent validity with several other measures (Gavita et al. 2011). We replaced the term “disobey” with “challenging behavior” in an attempt to make the items more applicable for parents of children with ASD. The classification ranges (e.g., “very low”, “low”, “medium”, “high” and “very high”) reported by Gavita et al. (2011) were used to assess change among participants.

Behavioral observations

One pre-intervention and one post-intervention behavioral observation was conducted in the home for each of the three participants. Each target child was videotaped by the first author during observations, which lasted ~30 min. These observations were individualized for each child, scheduled for contexts when problem behavior was most likely to occur (homework, play time, not winning a game with a sibling). The problematic context remained the same during the pre- and post-intervention observation and was conducted at the same time of day. At no time did the observer provide feedback to the parents. Videotapes were scored using a 10-s partial-interval time sampling procedure. Each video was scored for problem behaviors, which included aggression, tantrum, property destruction, stereotyped behavior, non-compliance and opposition, and inappropriate vocalizations. Interobserver agreement (IOA) was conducted for three of the six videotaped observations by a trained graduate research assistant and was found to be 96.3% (number of agreements divided by number of agreements + disagreements, multiplied by 100).

Data Analyses

Parental reported stress, child-responsible and parent-causal attributions, self-efficacy, rational and irrational beliefs, pessimism, and ratings of child problem behavior were analyzed using visual analysis as the primary analysis and mean baseline reduction (MBLR) and hierarchical linear regression (HLR) as supplemental analyses. MBLR was calculated by subtracting the mean of the last three intervention data point values from the mean of the last three baseline data point values; the difference between these means was then multiplied by 100 (Lundervold and Bourland 1988). Although MBLR as a nonparametric technique seemed most appropriate for our study, and the use of p-values in single-subject designs is currently an unresolved and emerging area (Travers et al. 2017), we decided to supplement our analysis with HLR to provide some estimate of effect size. HLR was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software which was then converted into a Cohen’s d using the equation in Campbell (2004). This allowed us to examine the statistical significance of each effect.

Treatment integrity and interobserver agreement

To ensure that the therapist (the first author) implemented PFI with quality and integrity, his doctoral dissertation mentor (the second author, who has expertise in both PBS and CBT) provided him with initial training in the protocol by role-playing and rehearsing several sessions prior to implementation with an actual participant. In addition, the actual PFI sessions were video-recorded and a portion of them were reviewed by the author’s doctoral dissertation mentor (the second author); feedback on these sessions was provided in supervision. Further, a procedural fidelity assessment created by Durand et al. (2013), consisting of a checklist of 10–13 objectives to be covered in each session, was completed by graduate research assistants via videotape to ensure that the first author adhered to the PFI protocol. Intervention fidelity was calculated across all 24 sessions and was found to be 100% (number of objectives completed divided by total number of objectives listed, multiplied by 100). IOA was assessed for 79.2% of treatment sessions by having the fidelity checklist completed separately by two graduate R.A.’s for each of the three participants (a total of six R.A.’s). Their scores were then compared on an item-by-item basis. IOA was calculated to be 100% (number of agreements divided by number of agreements + disagreements, multiplied by 100).

Results

Each dependent variable, excluding the pre- and post-intervention behavioral observations, was assessed using visual analysis, MBLR, and HLR. Figures 1–9 present the graphs for each of the variables across each of the three participants. In addition, Fig. 10 presents data from pre- and post-intervention behavioral observations. Table 1 shows the means of the last three data points during baseline and intervention, the percentage of change, and the Cohen’s d effect size calculated from HLR, across each of the dependent variables.

Parent reported ratings of stress. Measured during baseline and intervention for each participant using the Parenting Stress Index, 4th Edition—Short Form (PSI-4-SF; Abidin 2012)

Parent reported child-responsible attributions. Measured during baseline and intervention for each participant using the Parent Cognition Scale (Snarr et al. 2009)

Parent reported parent-causal attributions. Measured during baseline and intervention for each participant using the Parent Cognition Scale (Snarr et al. 2009)

Parent reported self-efficacy. Measuring during baseline and intervention for each participant using the Parent Sense of Competence Scale (PSOC; Johnston and Mash 1989)

Parent reported total rational and irrational beliefs. Measured during baseline and intervention for each participant using the Parent Rational and Irrational Beliefs Scale (P-RIBS; Gavita et al. 2011)

Parent reported irrational beliefs. Measured during baseline and intervention for each participant using the Irrational Beliefs (IBs) subscale of the Parent Rational and Irrational Beliefs Scale (P-RIBS; Gavita et al. 2011)

Parent reported rational beliefs. Measured during baseline and intervention for each participant using the Rational Beliefs (RBs) subscale of the Parent Rational and Irrational Beliefs Scale (P-RIBS; Gavita et al. 2011)

Parent reported pessimism and unhelpful beliefs. Measured during baseline and intervention for each participant using the Thoughts Quiz (Durand and Hieneman 2008)

Parent-reported problem behavior. Measured during baseline and intervention for each participant using the General Maladaptive Index (GMI) of the Scales of Independent Behavior—Revised (SIB-R; Bruininks et al. 1996)

Parental Stress

Visual inspection showed a decrease in parental stress for Jen, a slight decrease for Sarah, and little or no decrease for Marisa (see Fig. 1). Mean scores indicated an 11.4 and 5.5% decrease in stress for Jen and Sarah, respectively (see Table 1). For Jen, this change in level occurred immediately after the intervention was introduced, with no overlap between the baseline and intervention phases. Although Sarah reported a decrease in stress, her scores during intervention remained in the clinically elevated range. The HLR supported this finding, as the improvement was only statistically significant for Jen (see Table 1).

Parental Attributions

Visual inspection showed decreases in child-responsible attributions for Jen and Sarah, while a slight increase was found for Marisa (see Fig. 2). Mean scores (shown in Table 1) indicated a 14.7 and 15.9% decrease in dysfunctional child-responsible attributions for Jen and Sarah, respectively, both of which were found to be statistically significant through HLR (see Table 1). Sarah reported higher levels of child-responsible dysfunctional attributions during baseline, suggesting her improvements were more clinically relevant than Jen’s, whose baseline levels were within one standard deviation from the mean. Additionally, during the intervention phase, there was a decreasing trend over the course of intervention for Jen and Sarah. Although there was an initial increase in child-responsible attributions for Marisa in the first intervention session, the last three intervention sessions showed a decreasing trend.

Visual inspection showed decreases in parent-causal attributions for Jen and Sarah, with increases for Marisa (see Fig. 3). Mean scores (shown in Table 1) indicated a 37.5 and 13% decrease for Jen and Sarah, respectively, both of which were found to be statistically significant through HLR (see Table 1). Further, the last three sessions showed a sharp decreasing trend for Sarah. In contrast, Marisa experienced a 20.4% increase in dysfunctional attributions.

Self-Efficacy

Visual inspection showed an increase in self-efficacy for Jen and a slight increase for Sarah, with little or no change observed for Marisa (see Fig. 4). Mean scores (shown in Table 1) indicated an 11.5% increase for Jen, a 4.3% increase for Sarah, and a 3.7% decrease for Marisa, neither of which were found to be statistically significant through HLR (see Table 1).

Rational and Irrational Beliefs

Visual inspection of parent-reported total rational and irrational beliefs as measured by the P-RIBS showed a large decrease in level and a decreasing trend for Jen, with baseline scores decreasing from the “very high” range to the “medium” range following intervention and little overlap between the baseline and intervention phase (see Fig. 5). A slight decrease was observed for Sarah in the last two intervention sessions, although her scores remained in the “very high” range. Little or no change was observed for Marisa, as her scores remained stable in the “high” range across the baseline and intervention phases. Mean scores (shown in Table 1) indicated a 20.6% decrease for Jen, a 7.69% decrease for Sarah, and a very slight decrease of 2.3% for Marisa. Despite only a small change for Marisa, HLR indicated that the decreases for all three mothers were significant (see Table 1).

Visual inspection showed a large decrease in irrational beliefs for Jen, in terms of both level and trend, with baseline scores decreasing from the “high” to the “low” range following intervention (see Fig. 6). A slight decrease was evident in Sarah’s scores, which decreased from the “very high” to “high” range. Lastly, an increase in irrational beliefs was observed for Marisa. Mean scores (shown in Table 1) indicated a 23.2 and 6.4% decrease for Jen and Sarah, respectively, both of which were both found to be statistically significant through HLR (see Table 1). In contrast, Marisa experienced a 6% increase in irrational beliefs.

Visual inspection showed increases in rational beliefs, with an increasing trend over the course of intervention for Jen and an increasing trend in the last three sessions for all three participants (see Fig. 7). Mean scores (shown in Table 1) indicated a 30.6% increase for Jen, which reflected an improvement from the “very low” to “medium” range. Similarly, Marisa’s scores increased 15.7%, an improvement from the “very low” to “medium” range. Lastly, Sarah’s scores increased 10.5%, an improvement from the “very low” to “low” range. HLR indicated that all three participants reported statistically significant improvements (see Table 1).

Thoughts Quiz

Visual inspection showed decreases in parental pessimism for all three mothers, with the strongest reduction for Jen, who showed a decrease in level and a decreasing trend (see Fig. 8). Means scores (shown in Table 1) indicated a 32.1 and 16.5% decrease for Jen and Sarah, respectively, both of which were found to be statistically significant through HLR (see Table 1). Only a slight decrease of 3.4% was observed for Marisa, which was not visually evident and not statistically significant.

Parent Ratings of Child Problem Behavior

Visual inspection of the SIB-R showed decreases in child problem behaviors for Jen and Sarah (with Sarah showing the clearest decreasing trend in the intervention phase), though less so for Marisa (who showed a slight decreasing trend) (see Fig. 9). Means scores (shown in Table 1) indicated a 28.2% decrease in ratings of child problem behavior for Jen, a 22.1% decrease for Sarah, and an 8.5% decrease for Marisa. HLR indicated that the improvements in problem behavior reported by all three mothers were statistically significant (Table 1).

Direct Observation Measure of Child Problem Behavior

As shown in Fig. 10 and further supported using a paired samples t-test, the percentage of child problem behavior during the post-intervention observations (M = 3.88, SD = 2.21) was significantly less (t (2) = 4.35, p = 0.049) than the percentage of child problem behavior during the pre-intervention observations (M = 29.89, SD = 8.37) for all three families, demonstrating that observed problem behavior significantly decreased following completion of the PFI.

Discussion

The present study investigated the effect of PFI on problem behavior as well as on several parental attitudinal variables that could potentially serve as barriers to parent training including parents’ stress, self-efficacy, dysfunctional attributions, pessimism and unhelpful/irrational beliefs. As we hypothesized, and consistent with findings from Durand et al. (2013), all three children with ASD demonstrated statistically significant improvements in problem behavior as measured by parent-report, although visual analysis of the multiple baseline data did not show as pronounced change in Marisa’s perception of her child’s problem behavior as the statistical analysis revealed. While all three children also showed significant improvement in problem behavior as measured by direct behavioral observations, it is not possible to draw firm conclusions from the direct observation data, given that it was only collected once pre- and post-intervention. Although the effects of PFI on parent-reported problem behavior were not immediate in the multiple baseline data, as we would not expect them to be when intervention components were introduced sequentially/progressively over the course of an eight-session treatment, parent-reported ratings of child problem behavior appeared to improve gradually throughout the course of treatment for all three participants and did not appear to coincide with any specific treatment session. Noah showed the greatest improvements in child problem behavior as indicated by both Jen’s ratings on the SIB-R and direct behavioral observations. In contrast, Marisa reported the least improvement in child problem behavior on the SIB-R, although the pre- and post-intervention home observations indicated a significant decrease in Andrew’s problem behavior. This suggests that Marisa’s perception of her son’s problem behavior changed very little, despite his problem behavior appearing to improve in direct observations. It is possible that the limited decrease in parent-reported problem behavior may be a reflection of Marisa’s beliefs about her son and his behavior, although it is important to keep in mind that the comparatively large decrease in problem behavior via direct observation should be interpreted with caution, given that direct observation data was collected only pre- and post-intervention (which represents an AB design).

Improvements in parent rational and irrational beliefs followed a similar pattern. As hypothesized, all three participants showed decreases in unhelpful beliefs on the P-RIBS total scale and Thoughts Quiz, with Jen’s the largest and Marisa’s the smallest. This provides further support that, despite the improvements in problem behavior that Marisa’s son exhibited during the limited behavioral observations, she continued to have a pessimistic view. In contrast, Jen and Sarah reported greater decreases in irrational beliefs (P-RIBS) and pessimistic statements (Thoughts Quiz). This difference may have been the product of Marisa’s difficulty identifying her self-talk, disputing pessimistic beliefs, and substituting her negative beliefs with positive affirmations throughout the treatment sessions. Marisa required frequent prompting to understand and use the cognitive-behavioral strategies taught throughout the sessions, while Jen and Sarah demonstrated a greater understanding and independence in using the CBT strategies. This difference may be because Marisa appeared to be limited in her ability to be aware of and understand her own cognitions or self-talk. For example, when Marisa was asked to identify thoughts, she often described her general emotional state (e.g., “I was mad”) instead of a thought. Also, Marisa’s acquisition of skills to identify and dispute self-talk may have been hindered by her lack of homework completion between sessions, which is in line with previous studies that indicate that poor follow-through on homework/implementation outside of treatment is a predictor of caregivers’ nonresponse to behavioral intervention (Nehrig et al., 2019). It is also important to note that Marisa was the only non-Caucasian parent; it is possible there may have been cultural differences that made it harder for Marisa to benefit from the PFI intervention package as it is currently structured, which is an important direction for future research. Perhaps Marisa would have benefited more from a traditional family-based PBS approach that includes in vivo coaching (e.g., Lucyshyn et al. 2007) or from a PBS treatment that focuses more on acceptance than changing thoughts, such as Mindfulness-Based Positive Behavior Support (MBPBS; Singh et al. 2018).

Consistent with the improvements in irrational beliefs and pessimism for Jen and Sarah, both mothers showed decreases in dysfunctional child- and parent-causal attributions, thereby supporting both hypotheses. This suggests that Jen and Sarah appeared to blame their children and themselves less and less over the course of PFI, which may have resulted from their newly acquired skills in identifying and changing their self-talk. They learned to identify and dispute dysfunctional attributions with evidence that their child’s problem behaviors served a function and were influenced by antecedents and consequences, in contrast to the belief that their child was misbehaving on purpose “to be a bully,” for example.

Although we hypothesized that self-efficacy would improve for all three mothers, this was only true for Jen. While we would not expect Marisa’s self-efficacy to improve in light of her difficulty learning to identify and change her self-talk, a null hypothesis for Sarah appeared surprising given the aforementioned findings. This lack of improvement in self-efficacy for Sarah may be the result of a more broad view of self-efficacy assessed by the PSOC (e.g., “Being a parent is manageable, and any problems are easily solved”), rather than assessing self-efficacy that was specific to interventions or situations that trigger problem behavior (e.g., “I know what to do when my child has a tantrum at the grocery store”). The improvements in parental self-efficacy demonstrated by Jen may have resulted from her ability to generalize the newly taught cognitive strategies beyond the specific beliefs associated with difficult situations targeted during PFI to broader optimistic or helpful beliefs that reflect parenting in general, such as, “I honestly believe I have all the skills necessary to be a good mother to my child.”

Finally, we hypothesized that all participants would demonstrate significant decreases in parental stress. However, this was only true for Jen. Despite some improvement, Sarah’s and Marisa’s scores on the PSI-4-SF remained clinically elevated during intervention. Given Marisa’s difficulty understanding the cognitive strategies, as well as her scores on several other measures, her lack of improvement in stress was not surprising. However, Sarah’s lack of improvement is somewhat surprising in light of her improvements on the other measures. Potential explanations for this will be discussed below.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

There are several limitations to the present study. First, although parent-reported child problem behavior and the five parental cognitive/affective measures were examined using a multiple baseline design (an experimental single-subject design), direct observations of child problem behavior by the researchers were only conducted once for a 30-min session prior to PFI and once again after the PFI intervention was completed, which represents an AB design. Given that an AB design is considered a pre-experimental or quasi-experimental type of single-subject design, the reduction in observed problem behavior from pre- to post-intervention cannot be conclusively attributed to PFI, as opposed to just the passage of time, history, maturation, or other threats to internal validity. Of note, even though we only collected direct observation data on problem behavior pre- and post-intervention, given that Durand et al. (2013) already found that there were reliable changes in observed child problem behavior for 56% of the children in their study, our primary focus was to examine whether there was a change in parents’ cognitions or perceptions rather than examine whether there was a change in observed children’s behaviors. As such, we viewed the parent-report measures (assessed using a multiple baseline design) as our primary measures of change, with the pre-post change in child behavior via direct observation as our secondary or supplemental measure. Second, in addition to the aforementioned threats to internal validity, in terms of external validity, the present study was limited to three families of children with ASD and, as such, these findings cannot be generalized to all families of youth with ASD. Future research is needed to explore the effectiveness of PFI, or other programs that incorporate PBS with CBT, with larger samples of families of children with ASD using the same variables and other measures of parents’ cognitions, affect, and behavior.

Third, we recognize that the use of HLR or any statistical technique to evaluate a limited set of data with a very small number of participants is controversial and is an unresolved issue in single-case design (SCD). A novel aspect of our study was to use a multiple baseline design to examine changes in parents’ cognitions rather than examine changes in children’s behaviors (as is typically done in most SCD studies). With the exception of a few measures for some participants (such as the PSI and P-RIBS for Jen), visual inspection of mothers’ cognitive measures did not show the traditional kind of drastic or immediate change in level that is typically seen in published multiple baseline graphs of behavioral data. This makes sense, given that changes in cognitions occur more slowly than changes in behavior (e.g., Vernon and Berenbaum 2004) and we would expect that changes in cognitions are more subtle or nuanced, and therefore smaller, than changes in behavior. As such, relying solely on visual inspection and/or single-subject effect sizes that measure the amount of data overlap between phases (e.g., PND, NAP, Tau-U) might not have adequately captured or reflected any subtle changes in parents’ cognitions. For instance, Marisa’s data, in particular, may represent an example of smaller changes in cognitions over time that are supported by HRL results; even though little change was observed using visual analysis, HLR indicated statistically significant decreases in parent-reported child problem behavior on the SIB-R and improvement in total rational/irrational beliefs for Marisa. Given that some researchers argue that visual analysis detects only the strongest treatment effects, whereas more subtle but still important effects may not be identified (Davis et al. 2013), we decided to supplement our visual analysis with HLR in order to detect changes that may not be observed when using only visual analysis.

Fourth, the use of repeated measurements across several different scales may have had a negative impact on the results. Related to this, some of the measures we analyzed might be correlated and, as such, it is possible that the results of multiple statistical analyses could be inflated as a result of intercorrelations. Additionally, several of the measures used in this study (e.g., PCS, PSOC, P-RIBS) have not yet been normed on this population. For example, the PCS may reflect attributions more commonly made by parents of neurotypical children (e.g., “My child likes to see how far he/she can push me”) and may not tap attributions that could be specific to parents of children with ASD (e.g., “He behaves this way because of his autism; he can’t help it”). Further, it is unclear whether any of the measures we used are appropriate to be administered as repeated measures and are sensitive to weekly changes in parents’ cognitions. The measures used to assess parental stress and self-efficacy, in particular, may reflect too broad of a construct to be sensitive to change. For example, the broad constructs of parental stress assessed by the PSI-4-SF may be influenced not only by a child’s problem behavior or a parent’s unhelpful beliefs, but may also reflect a parent’s perception of the child’s deficits in social skills, difficulties in learning, or lack of social support. Likewise, the broad construct of parental self-efficacy assessed by the PSOC may be influenced by a parent’s overall satisfaction and interest in parenting beyond situations that evoke problem behavior. Therefore, it may be more beneficial for future studies to include individualized measures of parental stress and self-efficacy that are more specific to the situations and strategies that are targeted during PFI (e.g., withholding reinforcement for the child’s tantrum during homework) as well as measures of attributions that may be more common among parents of children with ASD.

A fifth limitation of the present study is that it did not include any assessment of maintenance, generalization, or social validity, which are important directions for future research. Rather than changing quickly or immediately, the cognitions of the parents in the present study appeared to change slowly with rehearsal and practice. Therefore, their cognitions may have continued to change following the last session of PFI, as they continue to practice disputation and develop positive affirmations to substitute for unhelpful thoughts. After all, Whittingham et al. (2009) found that their parenting program for parents of children with ASD did not have a significant effect on parental self-efficacy at post-treatment (and that parental efficacy actually decreased from pre- to post-treatment), but the within-subjects comparison for the treatment group showed a significant increase in parental efficacy between pre-treatment and six-month follow-up. Given that we only collected data from our parents immediately post-treatment, it is possible that, like Whittingham et al. (2009), we would have found some significant improvement in parental self-efficacy (or other variables) if we had collected data at a follow-up assessment, although that hypothesis of course remains untested. Alternatively, it is possible that parents may not continue to practice the strategies they learned in PFI without regular coaching or periodic booster sessions. Thus, future studies should include follow-up assessments of the dependent variables to gain insight into the long-term durability PFI. Additionally, although we examined the therapist’s procedural fidelity in implementing PFI, given the previously cited research that parents who experience higher stress may have difficulty implementing behavioral strategies more than parents with lower stress, future research should examine parents’ intervention fidelity or integrity in implementing their chosen strategies. As parents develop more helpful or optimistic beliefs about their children and their own parenting skills and abilities, they may be more likely to adhere to or follow through with specific behavioral strategies or interventions. Although the measures we used captured potential changes in parents’ attitudes/beliefs/thoughts/perceptions, they did not capture the extent to which the parents actually adhered to or followed through with the strategies they learned in PFI. Measuring the parents’ actual use of PFI strategies (in addition to applying the multiple baseline design to observed problem behavior instead of only to parent-reported problem behavior) would strengthen the evidence for the effects of PFI on observed child behavior.

Sixth, future research should seek to include both mothers and fathers in intervention. While PFI encourages parents to actively involve family members and other stakeholders as part of their support team, it may be critical for some families that all caretakers are directly taught to use the same strategies to ensure consistency and fidelity. For Marisa, this was likely a factor that limited her progress; despite her attempts to collaborate, she was unsuccessful in obtaining her husband’s support in working toward specific goals. Also, Marisa and her husband were unable to consistently implement the same strategies for difficult situations, which may have increased her vulnerability to unhelpful beliefs, dysfunctional attributions, low self-efficacy, and stress. However, it is important to keep in mind that, although we suggested some possible reasons for why Marisa experienced less benefit than the other two parents, our study did not include any design features or controls that addressed potential mitigating/moderating factors directly.

Further, future research should examine the effectiveness of PFI which includes an in-home component where strategies and interventions are modeled for parents in the natural environment (e.g., Lucyshyn et al. 2007, 2015) and parents are coached to identify and change their behaviors and self-talk in-vivo. As Durand et al. (2013) noted, in contrast to traditional family-based PBS, which involves direct coaching of parents’ interactions with their children in the natural environment, an advantage of PFI is that it involves parent training without requiring in-vivo coaching of parents on the implementation of the procedures at home with the child. Although reported and observed problem behavior improved for all three children in our study, there were not improvements in negative cognitions (e.g., attributions, self-efficacy, pessimism) for all three mothers, just as not every family in Durand et al. (2013) improved as a result of PFI. Therefore, since PFI seems to be effective for most parents, but not all parents, it becomes important to determine which families may benefit from the extra support of in-vivo coaching (e.g., modeling, performance feedback) at home and/or in the community with their children, in addition to parent-only sessions in the clinic. Future research should examine the family characteristics (e.g., divorce, marital distress, sibling relationships, SES), parent characteristics (e.g., parents’ depression, anxiety, stress, distress tolerance, treatment fidelity, attributions, discipline, social support) and child characteristics (e.g., severity of problem behavior pre-treatment, ASD symptom severity, comorbidity) that influence whether parents respond to parent-only treatment such as PFI or need additional coaching with their child present (as in traditional family-based PBS). Additionally, it is also important to identify the characteristics that determine which parents may benefit from adding CBT to PBS versus the parents for whom PBS alone is sufficient to produce significant positive changes. Future research should use sequential multiple assignment randomized trials (SMART) designs to examine which parents benefit from parent-only PBS, which parents need the addition of CBT, and which parents need the addition of in vivo coaching. Finally, future studies involving PFI should incorporate other strategies derived from CBT as well as intervention approaches that focus more on accepting than changing cognitions, such as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT). Indeed, some recent studies have infused mindfulness (Raulston et al. 2019; Singh et al. 2018) and ACT (Pennefather et al. 2018) with behavioral parent training or PBS for parents of children with ASD. These strategies may help parents to be cognizant of their own thoughts and emotions during difficult situations and enhance parents’ motivation to carry out behavioral interventions with fidelity.

Implications for Practice

The present study suggests that there may be benefits to incorporating aspects of CBT with PBS including decreasing parents’ pessimism, unhelpful beliefs, and dysfunctional attributions, as well as improving their rational beliefs and perceptions of the severity and frequency of problem behavior. These benefits extend beyond those already shown by Durand et al. (2013). Teaching cognitive strategies in the context of behavioral parent training or PBS may help improve parents’ ability to implement behavioral interventions with fidelity, cope with problematic situations, and generate more optimistic views about their children and their future.

In addition, this study also suggests that the integration of cognitive strategies with traditional behavioral interventions may aid practitioners in applying a more contextualized and comprehensive approach to assessment and intervention for challenging behaviors when working with parents and families of youth with ASD. While many of the practitioners who serve children with ASD and their families (e.g., behavior analysts, special educators, psychologists) are trained in applied behavior analysis (ABA) and/or PBS, they may not necessarily be trained in the principles or procedures of CBT. However, it may be beneficial for them to receive some training in this area, which would enable them to incorporate cognitive-behavioral strategies into parent training and/or teacher training when working with caretakers whose unhelpful thoughts and feelings make it difficult for them to implement behavioral interventions consistently (or at all). Although behavioral parent training might teach parents the strategies that are most effective to use with their children with ASD, it may be challenging for many parents to actually use those strategies if their thoughts and feelings get in the way. Thus, it may be important for providers to recognize that some parents of children with ASD do not only need to learn how to change their child’s problem behavior, but also how to change the way they are thinking about their children’s behaviors and thinking about themselves.

References

Abidin, R. R. (2012). The parenting stress index, 4th Edition professional manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Allen, K. D., & Warzak, W. J. (2000). The problem of parental nonadherence in clinical behavior analysis: effective treatment is not enough. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 33, 373–391.

Andra, M. L., & Thomas, A. M. (1998). The influence of parenting stress and socioeconomic disadvantage on therapy attendance among parents and their behaviour disordered preschool children. Education and Treatment of Children, 27, 195–208.

Bearss, K., Johnson, C., Smith, T., Lecavalier, L., Swiezy, N., Aman, M., & Scahill, L. (2015). Effect of parent training vs parent education on behavioral problems in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of the American Medical Association, 313(15), 1524–1533.

Berliner, S., Moskowitz, L. J., Braconnier, M., & Chaplin, W. F. (2020). The role of parental attributions and discipline in predicting child problem behavior in preschoolers with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 32, 695–717.

Brei, N. G., Schwarz, G. N., & Klein-Tasman, B. P. (2015). Predictors of parenting stress in children referred for an autism spectrum disorder diagnostic evaluation. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 27(5), 617–635.

Brookman-Frazee, L., Stahmer, A., Baker-Ericzen, M. J., & Tsai, K. (2006). Parenting interventions for children with autism spectrum and disruptive behavior disorder: opportunities for cross-fertilization. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 9, 181–200.

Bruininks, R. H., Woodcock, R. W., Weatherman, R. F., & Hill, B. K. (1996). Scales of independent behavior—Revised. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing.

Campbell, J. M. (2004). Statistical comparison of four effect sizes for single-subject designs. Behavior Modification, 28(2), 234–246.

Carr, E. G. (2007). The expanding vision of positive behavior support: research perspectives on happiness, helpfulness, hopefulness. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 9, 3–14.

Carr, E. G., Dunlap, G., Horner, R. H., Koegel, R. L., Turnbull, A. P., Sailor, W., & Fox, L. (2002). Positive behavior support: evolution of an applied science. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 4, 4–16.

Choi, K., & Kovshoff, H. (2013). Do maternal attributions play a role in the acceptability of behavioural interventions for problem behaviour in children with autism spectrum disorders? Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7, 984–996.

Clarke, S., Dunlap, G., & Vaughn, B. (1999). Family-centered, assessment-based intervention to improve behavior during an early morning routine. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 1(4), 235–241.

Coleman, P. K., & Karraker, K. H. (1998). Self-efficacy and parenting quality: Findings and future applications. Developmental Review, 18, 47–85.

Dabrowska, A., & Pisula, E. (2010). Parenting stress and coping styles in mothers and fathers of pre-school children with autism and Down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54, 266–280.

Davis, D. H., Gagné, P., Frederick, L. D., Alberto, P. A., Waugh, R. E., & Haarddorfer, R. (2013). Augmenting visual analysis in single-case research with hierarchical linear modeling. Behavior Modification, 37, 62–89.

Durand, V. M. (2001). Future directions for children and adolescents with mental retardation. Behavior Therapy, 32, 633–650.

Durand, V. M., & Hieneman, M. (2008). Helping parents with challenging children: positive family intervention facilitator guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc.

Durand, V. M., Hieneman, M., Clarke, S., Wang, M., & Rinaldi, M. L. (2013). Positive family intervention for severe challenging behavior I: a multisite randomized clinical trial. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 15(3), 133–143.

Durand, V. M., & Rost, N. (2005). Does it matter who participates in our studies? A caution when interpreting research on positive behavioral support. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 7(3), 186–188.

Eisen, A. R., Raleigh, H., & Neuhoff, C. C. (2008). The unique impact of parent training for separation anxiety disorder in children. Behavior Therapy, 39, 195–206.

Falk, N., Norris, K., & Quinn, M. (2014). The factors predicting stress, anxiety and depression in parents of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44, 3185–3203.

Gavita, O. A., David, D., DiGiuseppe, R., & DelVecchio, T. (2011). The development and validation of the Parent Rational and Irrational Beliefs Scale. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 2305–2311.

Hartley, S. L., Schaidle, E. M., & Burnson, C. F. (2013). Parental attributions for the behavior problems of children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 34(9), 651–660.

Haskett, M. E., Ahern, L. S., Ward, C. S., & Allaire, J. C. (2006). Factor structure and validity of the Parenting Stress Index-Short Form. Journal of Clinical and Adolescent Psychology, 35(2), 302–312.

Hastings, R. P., & Brown, T. (2002). Behavior problems of children with autism, parental self-efficacy, and mental health. American Journal of Mental Retardation, 107(3), 222–232.

Hersen, M., & Barlow, D. H. (1976). Single-case experimental designs: Strategies for studying behavior change. Oxford: Pergamon.

Horner, R. H., Carr, E. G., Strain, P. S., Todd, A. W., & Reed, H. K. (2002). Problem behavior interventions for young children with autism: a research synthesis. Journal of Autism & Developmental Disorder, 32(5), 423–446.

Iadarola, S., Levato, L., Harrison, B., Smith, T., Lecavalier, L., Johnson, C., & Scahill, L. (2018). Teaching parents behavioral strategies for autism spectrum disorder (ASD): effects on stress, strain, and competence. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 48(4), 1031–1040.

Johnston, C., & Mash, E. J. (1989). A measure of parenting satisfaction and efficacy. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 18, 167–175.

Jones, T. L., & Prinz, R. J. (2005). Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: a review. Clinical Psychology Review, 25, 341–363.

Kazdin, A. E. (1996). Dropping out of child therapy: issues for research and implication for practice. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 1, 133–156.

Lucyshyn, J. M., Albin, R. W., Horner, R. H., Mann, J. C., Mann, J. A., & Wadsworth, G. (2007). Family implementation of positive behavior support in a child with autism: longitudinal, single-case, experimental, and descriptive replication and extension. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 9(3), 131–150.

Lucyshyn, J. M., Dunlap, G., Albin, R. W. (Eds) (2002a). Families and positive behavior support: addressing problem behavior in family contexts. Baltimore: Brookes Publishing..

Lucyshyn, J. M., Dunlap, G. & Albin, R. W. (Eds) (2002b). Families and positive behavior support: addressing problem behavior in family contexts. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes.

Lucyshyn, J. M., Fossett, B., Bakeman, R., Cheremshynski, C., Miller, L., Lohrmann, S., & Irvin, L. K. (2015). Transforming parent-child interactions in family routines: longitudinal analysis with families of children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 3526–3541.

Lucyshyn, J. M., Miller, L. D., Cheremshynski, C., Lohrmann, S., & Zumbo, B. (2018). Transforming coercive processes in family routines: family functioning outcomes for families of children with developmental disabilities. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27, 2844–2861.

Lundervold, D., & Bourland, G. (1988). Quantitative analysis of treatment of aggression, self-injury, and property destruction. Behavior Modification, 12, 590–617.

Nehrig, N., Gillooly, S., Abraham, K., Shifrin, M., & Chen, C. K. (2019). What is a nonresponder? A qualitative analysis of nonresponse to a behavioralintervention. Cognitive & Behavioral Practice, 26, 411–420.

Ohan, J. L., Leung, D. W., & Johnston, C. (2000). The Parenting Sense of Competence scale: evidence of a stable factor structure and validity. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 32(4), 251–261.

Osborne, L. A., McHugh, L., Saunders, J., & Reed, P. (2008). The effect of parenting behaviors on subsequent child behavior problems in autistic spectrumconditions. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 2, 249–263.

Paczkowski, E., & Baker, B. L. (2008). Parenting children with developmental delays: the role of positive beliefs. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 1(3), 156–176.

Pennefather, J., Hieneman, M., Raulston, T. J., & Caraway, N. (2018). Evaluation of an online training program to improve family routines, parental wellbeing, and the behavior of children with autism. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 54, 21–26.

Raulston, T. J., Hieneman, M., Caraway, N., Pennefather, J., & Bhana, N. (2019). Enablers of behavioral parent training for families of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 693–703.

Raulston, T. J., Zemantic, P. K., Machalicek, W., Hieneman, M., Kurtz-Nelson, E., Barton, H., Hansen, S. G., & Frantz, R. J. (2019). Effects of a brief mindfulness-infused behavioral parent training for mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 13, 42–51.

Rezendes, D. L., & Scarpa, A. (2011). Associations between parental anxiety/depression and child behavior problems related to autism spectrum disorders: the roles of parenting stress and parenting self-efficacy. Autism Research and Treatment, 2011, 1–10.

Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1993). On the power of positive thinking: the benefits of being optimistic. Psychological Science, 2, 26–31.

Schreibman, L. (2000). Intensive behavioural/educational treatments for autism: Research needs and future directions. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, 373–378.

Singh, N. N., Lancioni, G. E., Medvedev, O. N., Myers, R. E., Chan, J., McPherson, C. L., Jackman, M., & Kim, E. (2020). Comparative effectiveness of caregiver training in Mindfulness-Based Positive Behavior Support (MBPBS) and Positive Behavior Support (PBS) in a randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness, 11, 99–111.

Snarr, J. D., Slep, A. M. S., & Grande, V. P. (2009). Validation of a new self-report measure of parental attributions. Psychological Assessment, 21(3), 390–401.

Solish, A., & Perry, A. (2008). Parents’ involvement in their children’s behavioral intervention programs: parent and therapist perspectives. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 2, 728–738.

Tiba, A., Johnson, C., & Vadineanu, A. (2012). Cognitive vulnerability and adjustment to having a child with a disability in parents of children with autistic spectrum disorder. Journal of Cognitive and Behavioral Psychotherapies, 12(2), 209–218.

Travers, J. C., Cook, B. G., & Cook, L. (2017). Null hypothesis significance testing and p values. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 32, 208–215.

Van den Hoffdakker, B. J., Nauta, M. H., Van der Veen-Mulders, L., Sytema, S., Emmelkamp, P., Minderaa, R. B., & Hoekstra, P. J. (2010). Behavioral parent training as an adjunct to routine care in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: moderators of treatment response. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 35(3), 317–326.

Vernon, L. L., & Berenbaum, H. (2004). A naturalistic examination of positive expectations, time course, and disgust in the origins and reduction of spider and insect distress. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 18, 707–718.

Whittingham, K., Sofronoff, K., Sheffield, J., & Sanders, M. R. (2009). Do parental attributions affect treatment outcome in a parenting program? An exploration of the effects of parental attributions in an RCT of Stepping Stones Triple P for the ASD population. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3, 129–144.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.M.: Co-designed the study, implemented the intervention in the study, conducted data analyses, and wrote first draft of manuscript. L.J.M.: Co-designed the study, supervised the first author’s implementation of intervention, collaborated in the writing and editing of the final manuscript, undertook all revisions in response to reviewers.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mueller, R., Moskowitz, L.J. Positive Family Intervention for Children with ASD: Impact on Parents’ Cognitions and Stress. J Child Fam Stud 29, 3536–3551 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01830-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01830-1