Abstract

Objective

The purpose of the current study was to evaluate the feasibility and initial efficacy of a large-group, time-limited Parent Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) adaptation for parents of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and externalizing behavior problems (EBP).

Methods

Participants included parents of 37 preschoolers (Mage = 4.80, 87% Male, 73% Hispanic/Latino) with ASD and comorbid EBP. Parents reported on their positive and negative parenting practices and parenting stress at a pre-and-post treatment assessment as well as at a 6-month follow-up assessment. Positive and negative parenting skills were observed and coded during a parent-child interaction. Additionally, parents were objectively assessed on their knowledge of principles learned in treatment at pre-and-post-treatment.

Results

The treatment was delivered with a high level of fidelity and was well received and attended by families. At post-treatment, parents reported improved parenting stress and parenting practices. Parents were also rated as engaging in more positive parenting skills and less negative parenting skills during play. Lastly, parents increased their knowledge of principles presented in treatment. Improvements in positive parenting practices were also maintained at a 6-month follow-up assessment.

Conclusions

Findings highlight the initial efficacy and transdiagnostic nature of group PCIT for improving outcomes for children with ASD and comorbid EBP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a pervasive developmental disorder marked by difficulties in social interaction, social communication, and repetitive/restricted behaviors (Ozonoff et al. 2007). In addition to impairments across a host of functional domains (Howlin 2003; Ozonoff et al. 2007; Stevens et al. 2000), children with ASD also tend to experience elevated rates of externalizing behavior problems (EBP), such as aggression, oppositionality, inattention and hyperactivity (Gadow et al. 2004; Goldstein and Schwebach 2004; Hartley et al. 2008; Lecavalier 2006; Mazurek et al. 2013). Indeed, children with ASD’s behavior problems are a strong predictor of heightened parenting stress (Lecavalier et al. 2006; Osborne and Reed 2009), decreased parental self-efficacy (Hastings and Brown 2002) and poorer family functioning (Herring et al. 2006). Thus, significant work has aimed to examine the behavioral functioning of children with ASD as it relates to parenting.

Behavioral parent training (PT) interventions represent the most well-established treatments for targeting EBP in young children (Eyberg et al. 2008; Pelham and Fabiano 2008). Despite its success for children with EBP, traditional behavioral PT has not been a common approach for children with ASD. Traditional interventions for ASD, largely based in applied behavior analysis, have focused on therapists working directly with children to improve behavior (Peters-Scheffer et al. 2011). Interventions that do incorporate parent mediated approaches often involve teaching parents techniques for improving adaptive skills with a lesser focus on parenting practices for managing disruptive behavior (Brookman-Frazee et al. 2006). In fact, the PT literatures for ASD and EBP populations have developed rather independently despite a common foundation in behavioral principles (Brookman-Frazee et al. 2006). Nonetheless, given the elevated rates of EBP in children with ASD, some work has emerged examining treatment of disruptive behavior within this population.

Currently, the approaches deemed most effective for reducing disruptive behavior in children with ASD include pharmacology and behavioral interventions (Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network 2002). Although effective, pharmacological interventions have been found to lead to significant side effects and short-term benefits. A more recent focus has emerged on traditional PT approaches, typically used with EBP samples, for children with ASD. A recent meta-analysis examined the efficacy of traditional PT approaches within samples of children with ASD (Postorino et al. 2017). Notably, this meta-analytic review identified only 8 randomized control trials with significant heterogeneity in sample sizes and effect sizes. The largest trial to date examined an individual PT program with 180 children with high functioning autism and demonstrated significant improvements in EBP (Bearss et al. 2015). Moreover, a variety of PT interventions were reviewed and it remains unclear whether any specific PT program may yield the greatest effects for children with ASD. Additionally, this meta-analysis reviewed studies examining PT across a relatively large age range (2–14 years). Thus, it remains unknown whether a PT program specifically geared towards younger children would also yield comparable effects.

Among the variety of PT programs available, Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT) has one of the largest evidence bases for reducing EBP in young children. Despite previous work supporting theory for using PCIT for this population (Masse et al. 2007), surprisingly limited work has examined PCIT with samples of children with ASD. To date, only one randomized trial has investigated components of PCIT for children with ASD and only used the child-directed portion of PCIT (Ginn et al. 2017). The initial promise of PCIT for children with ASD has been largely limited to studies with smaller samples (n = 17–19; Solomon et al. 2008; Zlomke et al. 2017) and case studies. Case studies have documented preliminary evidence for using PCIT with children with high functioning ASD (Armstrong and Kimonis 2013; Hatamzadeh et al. 2010; Masse et al. 2016), as well as children with ASD and developmental delays or intellectual disability (Agazzi et al. 2013; Armstrong et al. 2015; Lesack et al. 2014).

Although previous work supports the initial promise of PCIT for ASD, several shortcomings of PCIT should be noted. Given the often lengthy treatment course (e.g., 12–20 sessions), attrition remains a significant problem for traditional PCIT, with dropout rates over 30% (Werba et al. 2006). Traditional PCIT protocol adheres to a “mastery criteria,” where families must meet specific benchmarks for treatment skills before completing treatment, which often prolongs treatment and may contribute to dropout. Additionally, traditional PCIT is typically delivered in an individual format contributing to concerns of cost-effectiveness. Given cost-effectiveness concerns with individual PCIT, emerging work has examined the utility of PCIT within a group format (Niec et al. 2005). Specifically, in a randomized controlled trial, Niec et al. (2016), found PCIT to be effective with groups of 3–5 families. Similarly, others have documented positive outcomes for PCIT with groups of 2–5 families (Nieter et al. 2013). While previous work has established the initial promise of PCIT with relatively small groups, considerably less work has examined large group formats. One study documented the initial promise of a time-limited PCIT program delivered in a large group format for preschoolers with EBP, which seemed to overcome some of the shortcomings of traditional PCIT (Graziano et al. 2018). However, it remains unclear whether this program would also yield comparable outcomes for children with ASD.

The current study sought to examine the feasibility and initial efficacy of a large group, time-limited PCIT program for improving EBP in preschoolers with ASD. Given that traditional PCIT has demonstrated potential for improving outcomes for children with ASD, it would be beneficial to examine whether a large-group, time-limited version would be effective in improving outcomes alike for this population. Thus, the purpose of the current study was to examine the initial promise of group PCIT for a sample of children with ASD and concurrent EBP in improving parenting outcomes across (a) parenting practices, (b) parenting stress, and (c) treatment knowledge. We expected that after completing group PCIT, parents would improve across all parenting outcomes.

Method

Participants

The study was conducted at a large urban university in the Southeastern United States with a large Hispanic/Latino population. Sixty-nine interested families completed a preliminary phone screening and scheduled a screening appointment. In order to qualify for the study, participants were required to (a) qualify for an ASD diagnosis via the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R; Rutter et al. 2003) OR have a previous documented diagnosis of ASD with elevated levels of ASD symptoms on the parent or teacher Autism Spectrum Rating Scale (ASRS; Goldstein and Naglieri 2009), (b) have a t- score of 60 or above on the Hyperactivity, Inattention, or Aggression Scales of the Behavior Assessment System for Children, 2nd Edition (BASC-2; Reynolds and Kamphaus 2004) parent or teacher reports, (c) have an estimated verbal IQ of 65 or higher on the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence, 4th Edition (WPPSI-IV, Wechsler 2012), (d) be enrolled in preschool during the previous year either transitioning to kindergarten or prekindergarten in the fall, and (e) be able to attend a daily 8-week summer program. See Table 1 for further sample descriptive statistics and diagnostic information.

The final participating sample consisted of 37 preschoolers (87% male, Mage = 4.80, SD = .53) with co-occurring ASD and EBP whose parents provided consent to participate in the study. Study questionnaires were completed primarily by mothers (84%) with a median income range between $35,000 and $50,000. In terms of ethnicity and racial makeup, 73% of the children were Hispanic/Latino-White, 22% were Non-Hispanic/Latino-White, and the remaining 5% identified as multiracial or other. Fifty-eight percent of the sample were self-referred, 32% were referred by a mental health professional or physician, while the remaining 11% were referred by preschool personnel.

Procedures

This study was approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board. An open trial design was used to examine the feasibility and initial efficacy of the parenting program in improving parenting outcomes for parents of preschoolers with ASD and elevated levels of EBP. All families participated in a pre-treatment assessment and post-treatment assessment 1–2 weeks following the completion of the intervention and did not receive compensation for completing assessments. Families were also invited to participate in a follow-up assessment six months after the completion of treatment.

As part of the pre-treatment assessment, consenting caregivers brought their children to the clinic on two occasions and were videotaped during several tasks. During the first visit, clinicians administered the WPPSI-IV (Wechsler 2012) while the consenting caregiver completed various questionnaires and participated in two structured interviews, the ADI-R (Rutter et al. 2003) and the Kiddie-Disruptive Behavior Disorder Schedule (K-DBDS; Keenan et al. 2007). Eligible participants were invited to attend the second laboratory visit, where parents and children were videotaped during a parent-child interaction.

All pre-treatment assessments, with the exception of diagnostic interviews and IQ tests, were re-administered at the post-treatment assessment and parents were asked to complete post-treatment questionnaires. A subsample of families also completed a 6-month follow-up assessment (n= 27) where parent reports were re-administered. Of note, there were no significant differences in demographic (e.g., child age, sex, ethnicity) or study variables for families who completed the follow-up assessment compared to those who did not.

Intervention

All children participated in the summer treatment program for pre-kindergarteners (STP-PreK; Graziano et al. 2014; Graziano and Hart 2016). The STP-PreK is an 8-week multimodal intervention which includes a behavior modification program and academic and social-emotional curriculum delivered within a classroom summer camp setting. As part of their participation in the STP-PreK and of interest to the current study, parents attended a school readiness parenting program each week for 2 hours (SRPP; Graziano et al. 2018). The SRPP includes group PCIT along with the addition of several discussion topics on school readiness. The first half of each session focused on traditional PT aspects (e.g., improving the parent-child relationship, use of reinforcement, time-out) based on the PCIT protocol with 4 sessions focused on the child-directed interaction (CDI) and 4 sessions focused on the parent-directed interaction (PDI). The 4 CDI sessions included a teaching session, where parents were taught via large group didactic format to increase labeled praise, reflections, and behavior descriptions while decreasing questions, commands, and criticisms during play. During the 3 CDI coaching sessions, parents were divided into 2–3 subgroups to practice skills with their own child for 10–15 minutes each. While one parent in each subgroup practiced, the other parents observed and coded CDI skills. During practice, two therapists rotated coaching parents in each subgroup and then allowed observing parents to provide positive feedback. Parents in each subgroup then rotated to practice with their own child for the total 45 minute coaching period. After the coaching period, a large group discussion was facilitated to review session challenges and progress. The remaining 4 PDI sessions included a very similar structure, including a PDI teach session where parents were taught to increase direct commands and utilize a time-out system for non-compliance. PDI coaching sessions were implemented in the same format as CDI coaching sessions but typically only included 2 parents practicing at a time. (i.e., 2 subgroups). Consistent with standard PCIT, time-out procedures were included as a core component of the intervention. While parents were taught to use the time out room and swoop and go procedures for home practice, given space restrictions within session, “timeout room” involved relocating the child to outside of the classroom where the session was taking place.

Of note, mastery of “Do” and “Don’t” skills (i.e., 10 instances of each do skill, 3 or less don’t skills) was not required for progression throughout the intervention given limitations of treatment within a group/time-limited format. However, all parents were coached in CDI and PDI at least once and were able to observe every parent in the group being coached. As another measure of parenting attainment of skills, treatment knowledge quizzes were completed to assess knowledge of CDI and PDI procedures, with many questions focusing on effective commands and timeout.

To facilitate discussion within a large group format, parents contributed to the didactic discussion via a Community Parent Education Program (COPE; Cunningham et al. 1998) style. The COPE style allowed parents to lead the discussion and contribute to problem solving by providing suggestions to one another, rather than relying on the therapist to provide all information in a more strictly lecture-based manner.

During the second half of each session, school readiness topics were discussed (e.g., managing behavior during homework time, reinforcing social skills). Of note, when reviewing school readiness topics, strategies consistent with PCIT (e.g., praise, active ignoring) were discussed as they relate to the promotion of school readiness.

For the purposes of the current study, no major modifications or tailoring of the intervention was employed for use with the ASD population. Although group PCIT presents an adaptation in itself, no formal changes from the standard SRPP (as tested in Graziano et al. 2018) were made. While all children in the current sample had high functioning ASD, families were primarily seeking treatment for EBP concerns, thus the target of treatment and typical presenting problems were similar to the standard SRPP. Not surprisingly though, parents did occasionally raise behavioral issues related to ASD (e.g., temper tantrums due to changing routines). In these situations, the COPE style was used to help parents problem solve these behavioral issues, in a similar approach to the standard SRPP. Importantly, during these discussions, PCIT principles were often used to address ASD specific behavior problems (e.g., positive attending, ignoring, timeout).

Measures

Treatment fidelity

Fidelity for the parenting program was completed by a doctoral level graduate student for 2 of 8 sessions, with weekly group supervision provided by a licensed psychologist. Treatment integrity coding involved assessing for inclusion of all session content (e.g., providing overview, collecting homework, coaching parent practice). In addition coders rated therapists on a 1-to-7 point scale (1 = superior, 7 = inadequate) in terms of how effective they were in engaging parents and providing social reinforcement and support during the session.

Treatment attendance and satisfaction

Parent attendance to each session was collected. At the completion of treatment, parents completed the Therapy Attitude Inventory (TAI; Brestan et al. 1999) as a measure of treatment satisfaction. The TAI is a 10-item parent-report measure that assesses parent satisfaction with treatment and has demonstrated excellent internal consistency (α = 0.91; Brestan et al. 1999). For the purposes of the current study, the overall satisfaction item was analyzed.

Parenting stress

Parents completed the Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (PSI-SF; Abidin 1995). The PSI-SF is a 36-item self-report measure yielding scales of parental distress, child behavior, and parent-child dysfunctional interaction. Studies have documented acceptable internal consistency (α = .83) for the PSI-SF as well as concurrent validity with measures of parental psychopathology (Haskett et al. 2006). For the current study the total stress scores were used (α’s = .90–.93).

Parenting practices

Parents completed the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ; Shelton et al. 1996), which consists of 42-items measuring: positive parenting, parental involvement, inconsistent discipline, poor monitoring/supervision, and corporal punishment. Responses for items are based on a 5 point scale: “never,” “almost never,” “sometimes,” “often,” and “always.” Studies utilizing the APQ have provided evidence of criterion validity and good test-retest reliability (Essau et al. 2006). The APQ has been used with parents of children as young as three (Clerkin et al. 2007). To reduce the number of analyses, the current study examined a positive parenting practices composite (α’s = .73–.86; involvement and positive parenting scales). Additionally, given previous work documenting inadequate reliability for the poor monitoring/supervision and corporal punishment subscales (Dadds et al. 2003), the current study used the inconsistent discipline scale (α’s = .63–.70) as the negative parenting measure.

Observed parenting skills

The Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System, 4th Edition (DPICS-IV; Eyberg et al. 2013) is a behavioral coding system that measures the quality of parent-child interactions. DPICS has been found to be reliable and valid (Eyberg et al. 2013). For this study, we created two composite categories to reflect the skills parents learn in PCIT: “Do Skills,” which included behavior descriptions, reflections and praises, and “Don’t Skills,” which included questions, commands, and negative talk. At the pre-and-post-treatment assessment parents were videotaped interacting with their child during a child-led play, parent-led play, and clean-up situation, each lasting 5 minutes. For the purposes of the current study, “Do” and “Don’t” skills were assessed during the 5-minute child-led play where the parent was instructed to follow the child’s lead in play. Although parent-led play and clean up situations were coded, coding during child-led play was deemed most appropriate for measuring “Do” and “Don’t” skills. Coding during parent-led play and the clean-up task focused on child compliance, which was deemed beyond the scope of this paper (i.e., beyond parenting outcomes). Coding was completed by undergraduate coders initially trained on 15 pre-existing training videos (5 child-led play videos, 5 parent-led play videos, 5 clean-up videos) to 80% agreement. Once reliable with training videos, independent coding of study videos was assigned to coders. Twenty percent of observations were coded a second time for reliability (r’s = .80–.98 “Do”& “Don’t” skills at pre-and-post-treatment).

Treatment knowledge

Treatment knowledge attainment was measured by quiz scores on a PCIT content knowledge quiz adapted from Lee et al. (2011) with added questions on school readiness topics (40 multiple choice questions). Previous studies examining the psychometric properties of the PCIT content quiz report adequate internal consistency (Lee et al. 2011). As part of the pre-treatment assessment, parents completed the treatment knowledge quiz and were re-administered the quiz at the post-treatment assessment. The quiz score used in analyses included all questions including both PCIT specific content as well as school readiness topics. All questions were included as the school readiness topics were integral to the PT program and influential in session content. Additionally, many questions required parents to use knowledge across topics where it was hard to disentangle knowledge from PCIT versus school readiness topics (e.g., “how to use PCIT skills while reading to your child”). Pre-and-post-treatment knowledge scores were calculated for each parent based on the number of questions answered correctly out of the total 40 items.

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 23.0 (SPSS 23). For pre-and-post treatment measures there was less than 10% missing data on all parent and objective reports. According to Little’s Missing Completely at Random Test there was no evidence to suggest that the data were not missing at random, χ2 (32) = 27.14, p = .71. All available data were used for each analysis. Descriptive data were provided to establish the feasibility and acceptability of the program. To examine the preliminary efficacy and given the open trial nature of this study, we conducted multiple repeated measures ANOVAs. Although we did not have a between-subjects factor, within-subjects follow-up contrast tests, with a Bonferroni correction to minimize type 1 error, were conducted to examine any changes from pre- to post-treatment. Cohen’s d effect size estimates ([pre-treatment − post-treatment]/pooled SD) were provided for all analyses. Of note, only two families dropped out of treatment and did not complete a post-treatment assessment. These two families were excluded from analyses including post-treatment data. Additional analyses also examined follow-up data (n = 27) using repeated measures ANOVA and within subjects follow-up contrast tests to examine maintenance of changes from pre-treatment to follow-up treatment. Cohen’s d effect size estimates were also calculated for analyses containing follow-up data.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

An analysis of demographic variables revealed a significant association between child sex and observed “Do” skills during the child-led play, such that parents of girls tended to use lower levels of “Do” skills during the post-treatment child-led play (r = −.45, p < .01). Additionally, parents of children from Hispanic/Latino backgrounds tended to have higher scores on the baseline assessment of treatment knowledge (r = .35, p < .05). Lastly, parents with higher educational backgrounds also performed better on the assessment of treatment knowledge after completing treatment (r = .35, p < .05). Preliminary analyses did not yield any other significant associations between demographic variables (e.g., child age, income) and study outcomes. Thus, all subsequent analyses controlled for child sex, child ethnicity, and parental educational level.

Feasibility and Acceptability

Fidelity was completed on 25% of sessions. The two graduate-level therapists conducting the SRPP attained excellent fidelity (100%). The therapists were also rated highly in their effectiveness for engaging parents during the session (M = 1.0), and providing social reinforcement and support to parents (M = 1.0).

On average parents attended 88% of the 8 parent training sessions (M = 7.14, SD = .91). Additionally, as rated on the TAI parents reported high levels of satisfaction with the parenting program (M = 4.86 out of 5).

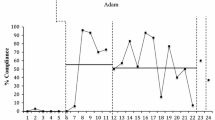

Preliminary Efficacy

As seen in Table 2, results revealed significant improvements in parent rated parenting practices and stress. Specifically, parents reported decreased levels of parenting stress on the PSI from pre-to-post-treatment, F (1, 30) = 11.14, p < .001, d = −.55. Additionally, parents reported significantly lower levels of negative parenting practices, F (1, 30) = 23.85, p < .001, d = −.63, and marginally higher levels of positive parenting practices on the APQ at post-treatment, F (1, 30) = 3.76, p = .06, d = .39. Follow-up analyses demonstrated that improvements in positive parenting practices were also maintained at follow-up as practices remained higher than pre-treatment levels (d = .54, See Fig. 1). However, improvements in parenting stress and negative parenting were not maintained at follow-up.

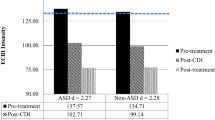

Results revealed improvements in observed parenting skills during the child-led play (see Fig. 2). Specifically, parents displayed significantly higher levels of “Do” skills at post-treatment, F (1, 28) = 78.96, p < .001, d = 1.61, as well as significantly lower levels of “Don’t” skills, F (1, 28) = 51.40, p < .001, d = −1.37. As seen in Table 3, parents also improved in their knowledge of treatment principles from pre-to-post-treatment, F (1, 30) = 108.88, p < .001, d = 1.91.

Discussion

Findings of the current study support the feasibility and initial efficacy of group PCIT for improving parenting outcomes for parents of preschoolers with ASD and EBP. The program was delivered with high fidelity and was well received by parents. Results demonstrated medium to large improvements in reported stress and parenting practices, observed parenting skills, and treatment knowledge. Study findings are discussed in further detail below.

Consistent with our hypothesis and in line with previous work on the efficacy of the SRPP (Graziano et al. 2018), the parenting intervention was successful in reducing parenting stress and improving parenting skills. Findings highlight the role of the SRPP as a transdiagnostic treatment with comparable efficacy across diagnostic groups. Consistent with previous work documenting the initial promise of PCIT for samples of children with ASD (Solomon et al. 2008; Zlomke et al. 2017), the current study went a step further by documenting initial efficacy of an adapted version of PCIT. Specifically, the SRPP program aimed to address some of the shortcomings of traditional PCIT by utilizing a time-limited, large group approach. Indeed, the dropout rate within the current study sample (<5%) was minimal and considerably lower than traditional PCIT attrition rates (Werba et al. 2006). This may be especially important for treatments targeting young children with ASD as this population typically requires a host of services (e.g., speech therapy, physical/occupational therapy), making engaging in PT for co-occurring EBP more challenging. Results highlight that perhaps briefer time-limited PT formats may aid in maximizing adherence and reducing attrition for parents of children with complex comorbid presentations. Additionally, traditional ASD treatments are often delivered in an individual format and costly (DeFilippis and Wagner 2016). Thus, using a large group approach seems to provide a potential alternative that may reduce costs and barriers to treatments for families.

Clinical implications that may be gleaned from the current study’s findings are the utility of using PCIT to address EBP in children with ASD without significant modifications. PCIT may be an especially valuable approach for young children with ASD given the coaching component inherent within the treatment. Indeed, a meta-analysis on parent training interventions found that interventions requiring parents to practice with their own child tended to have larger effect sizes (Kaminski et al. 2008). It may be the case that for children with a complex and impairing disorder, such as ASD, and comorbid EBP, it may be even more important for parents to benefit from live coaching. While, traditional PCIT encourages parents to reflect, describe, and praise behaviors, the appropriateness of target behaviors may not be as obvious for parents of children with ASD. For instance, for children with EBP inappropriate behaviors are more easily identified, whereas children with ASD may display odd and/or repetitive behaviors in addition to EBP, adding a layer of complexity for parents to manage. Thus, the use of live coaching during sessions may be additionally valuable for parents as they are mastering skills to modify behaviors with a variety of functions (e.g., attention seeking vs. self-stimulatory). Nonetheless, it should be noted that results from this study encompass results from one single trial and should provide considerations for future research in order to achieve replicable results that may inform clinical practice and policy.

Additionally, the SRPP’s large group format may be of further utility as it allowed for parents to observe other parents being coached. This may be especially helpful for parents of children with ASD as it provides a contextual support for children with chronic impairments. Indeed, social support has been linked to reductions parenting stress for mothers of young children with ASD both concurrently and longitudinally (Zaidman-Zait et al. 2017). Consistent with findings of the current study, more recent work investigating the initial promise of PCIT with children with ASD has also documented improvements in parenting stress (Agazzi et al. 2017). Future work should examine the extent to which coaching within group PT, as well as coaching more broadly, provides additional benefits for children with ASD in order to determine the most optimal PT approach for this population.

While improvements in positive parenting were maintained after a 6-month follow-up, it should be noted that improvements from pre-to-post-treatment in parenting stress and negative parenting were not maintained. Ample work has documented elevated levels of parenting stress in parents of children with ASD. Although some studies have suggested that parenting stress within this population is more strongly influenced by EBP (Lecavalier et al. 2006; Osborne and Reed 2009), others have also attributed considerable variance in parenting stress to other factors associated with ASD (e.g., socio-communicative difficulties, adaptive skills; Hall and Graff 2011; Tomanik et al. 2004). While the parenting intervention was aimed at improving disruptive behaviors, other impairments associated with ASD, which were not directly targeted within the intervention, may still contribute to ongoing parenting stress. Additionally, with regard to negative parenting, while parents were able to maintain engagement in positive parenting practices, it may be more difficult to avoid negative parenting practices over time. Given the bidirectional nature of the association between children’s EBP and parenting practices (Pardini et al. 2008; Patterson 1982), it is not surprising that, although initially reduced, children’s EBP continued to elicit negative parenting behaviors. Additionally, these results may have been influenced by the ethnic composition of our sample, as previous work has shown that parents from minority backgrounds tend to engage in heightened levels of negative parenting practices, such as corporal punishment (see Fontes 2002 for a review).

Limitations

Several limitations to the current study should be addressed. First, the open trial design and small sample size of the study limited our ability to examine the effect of the intervention in comparison to a control group. However, substantial evidence exists documenting the stability of behavioral and academic problems for children with ASD if left untreated (Roberts et al. 2003). Nonetheless, future work should examine the efficacy of group PCIT for children with ASD using a randomized design with a larger sample size to more rigorously examine its effects. Further, while follow-up data were available for most study measures, observed parenting skills (i.e., DPICS coding) was not available. Although gains in self-reported positive parenting practices seemed to maintain over time, future studies should investigate the extent to which objective improvements in parenting also maintain.

An additional limitation to consider is that all of the children in the study were also enrolled in the classroom component of the STP-PreK. Notably, a recent randomized clinical trial of the STP-PreK documented no additive effect of the classroom component on behavioral functioning outcomes (Graziano and Hart 2016). Nonetheless, it is plausible that improvements in children’s behavior, along with parental perceptions of effort in bringing their child to the day camp, may have had impacts on parent’s perceptions of their parenting skills, stress and overall engagement with PT.

In sum group PCIT demonstrated feasibility and initial efficacy in improving outcomes for children with ASD and co-occurring EBP. Given the more recent focus on co-occurrence and overlap of functional impairments across diagnostic groups, the use of transdiagnostic treatment approaches is becoming increasingly important. The SRPP provides an example of a program that not only addresses shortcomings of traditional PT approaches but also is clinically valuable across diagnostic groups. Given the initial promise of group PCIT for young children with ASD and co-occurring EBP, further work is needed to support the efficacy of this approach in improving parenting outcomes.

References

Abidin, R. R. (1995). Manual for the parenting stress index. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Agazzi, H., Tan, S. Y., Ogg, J., Armstrong, K., & Kirby, R. S. (2017). Does parent-child interaction therapy reduce maternal stress, anxiety, and depression among mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder? Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 39(4), 283–303.

Agazzi, H., Tan, R., & Tan, S. Y. (2013). A case study of parent–child interaction therapy for the treatment of autism spectrum disorder. Clinical Case Studies, 12(6), 428–442.

Armstrong, K., DeLoatche, K. J., Preece, K. K., & Agazzi, H. (2015). Combining parent–child interaction therapy and visual supports for the treatment of challenging behavior in a child with autism and intellectual disabilities and comorbid epilepsy. Clinical Case Studies, 14(1), 3–14.

Armstrong, K., & Kimonis, E. R. (2013). Parent–child interaction therapy for the treatment of asperger’s disorder in early childhood: a case study. Clinical Case Studies, 12(1), 60–72.

Bearss, K., Johnson, C., Smith, T., Lecavalier, L., Swiezy, N., Aman, M., & Sukhodolsky, D. G. (2015). Effect of parent training vs parent education on behavioral problems in children with autism spectrum disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 313(15), 1524–1533.

Brestan, E. V., Jacobs, J. R., Rayfield, A. D., & Eyberg, S. M. (1999). A consumer satisfaction measure for parent-child treatments and its relation to measures of child behavior change. Behavior Therapy, 30(1), 17–30.

Brookman-Frazee, L., Stahmer, A., Baker-Ericzen, M. J., & Tsai, K. (2006). Parenting interventions for children with autism spectrum and disruptive behavior disorders: Opportunities for cross-fertilization. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 9(3-4), 181–200.

Clerkin, S. M., Halperin, J. M., Marks, D. J., & Policaro, K. L. (2007). Psychometric properties of the Alabama parenting questionnaire–preschool revision. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 36(1), 19–28.

Cunningham, C. E., Bremner, R., & Secord-Gilbert, M. (1998). The community parent education (COPE) program: a school-based family systems oriented course for parents of children with disruptive behavior disorders. Ontario, Canadá: Hamilton Heath Sciences Corp.

Dadds, M. R., Maujean, A., & Fraser, J. A. (2003). Parenting and conduct problems in children: Australian data and psychometric properties of the Alabama parenting questionnaire. Australian Psychologist, 38(3), 238–241.

DeFilippis, M., & Wagner, K. D. (2016). Treatment of autism spectrum disorder in children and adolescents. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 46(2), 18.

Essau, C. A., Sasagawa, S., & Frick, P. J. (2006). Psychometric properties of the Alabama parenting questionnaire. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15(5), 595–614.

Eyberg, S. M., Nelson, M. M., & Boggs, S. R. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37(1), 215–237.

Eyberg, S. M., Nelson, M. M., Ginn, N. C., Bhuiyan, N., & Boggs, S. R. (2013). Dyadic Parent–Child Interaction Coding System (DPICS) comprehensive manual for research and training. Gainesville: 4th PCIT International.

Fontes, L. A. (2002). Child discipline and physical abuse in immigrant Latino families: reducing violence and misunderstandings. Journal of Counseling & Development, 80(1), 31–40.

Gadow, K. D., DeVincent, C. J., Pomeroy, J., & Azizian, A. (2004). Psychiatric symptoms in preschool children with PDD and clinic and comparison samples. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(4), 379–393.

Ginn, N. C., Clionsky, L. N., Eyberg, S. M., Warner-Metzger, C., & Abner, J. P. (2017). Child-directed interaction training for young children with autism spectrum disorders: Parent and child outcomes. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46(1), 101–109.

Goldstein, S., & Naglieri, J. A. (2009). Autism Spectrum Rating Scales (ASRS™). Tonawanda: Multi-Health Systems.

Goldstein, S., & Schwebach, A. J. (2004). The comorbidity of pervasive developmental disorder and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: results of a retrospective chart review. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 34(3), 329–339.

Graziano, P. A., & Hart, K. (2016). Beyond behavior modification: benefits of social–emotional/self-regulation training for preschoolers with behavior problems. Journal of School Psychology, 58, 91–111.

Graziano, P. A., Ros, R., Hart, K. C., & Slavec, J. (2018). Summer treatment program for preschoolers with externalizing behavior problems: a preliminary examination of parenting outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46(6), 1253–1265.

Graziano, P. A., Slavec, J., Hart, K., Garcia, A., & Pelham, W. E. (2014). Improving school readiness in preschoolers with behavior problems: results from a summer treatment program. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 36(4), 555–569.

Hall, H. R., & Graff, J. C. (2011). The relationships among adaptive behaviors of children with autism, family support, parenting stress, and coping. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 34(1), 4–25.

Hartley, S. L., Sikora, D. M., & McCoy, R. (2008). Prevalence and risk factors of maladaptive behaviour in young children with autistic disorder. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 52(10), 819–829.

Haskett, M. E., Ahern, L. S., Ward, C. S., & Allaire, J. C. (2006). Factor structure and validity of the parenting stress index-short form. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 35(2), 302–312.

Hastings, R. P., & Brown, T. (2002). Behavior problems of children with autism, parental self-efficacy, and mental health. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 107(3), 222–232.

Hatamzadeh, A., Pouretemad, H., & Hassanabadi, H. (2010). The effectiveness of parent–child interaction therapy for children with high functioning autism. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 994–997.

Herring, S., Gray, K., Taffe, J., Tonge, B., Sweeney, D., & Einfeld, S. (2006). Behaviour and emotional problems in toddlers with pervasive developmental disorders and developmental delay: associations with parental mental health and family functioning. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 50(12), 874–882.

Howlin, P. (2003). Outcome in high-functioning adults with autism with and without early language delays: implications for the differentiation between autism and Asperger syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(1), 3–13.

Kaminski, J. W., Valle, L. A., Filene, J. H., & Boyle, C. L. (2008). A meta-analytic review of components associated with parent training program effectiveness. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(4), 567–589.

Keenan, K., Wakschlag, L. S., Danis, B., Hill, C., Humphries, M., Duax, J., & Donald, R. (2007). Further evidence of the reliability and validity of DSM-IV ODD and CD in preschool children. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(4), 457–468.

Lecavalier, L. (2006). Behavioral and emotional problems in young people with pervasive developmental disorders: relative prevalence, effects of subject characteristics, and empirical classification. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(8), 1101–1114.

Lecavalier, L., Leone, S., & Wiltz, J. (2006). The impact of behaviour problems on caregiver stress in young people with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 50(3), 172–183.

Lee, E. L., Wilsie, C. C., & Brestan-Knight, E. (2011). Using Parent–Child Interaction Therapy to develop a pre-parent education module. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(7), 1254–1261.

Lesack, R., Bearss, K., Celano, M., & Sharp, W. G. (2014). Parent–Child Interaction Therapy and autism spectrum disorder: adaptations with a child with severe developmental delays. Clinical Practice in Pediatric Psychology, 2(1), 68.

Masse, J. J., McNeil, C. B., Wagner, S. M., & Chorney, D. B. (2007). Parent-child interaction therapy and high functioning autism: a conceptual overview. Journal of Early and Intensive Behavior Intervention, 4(4), 714.

Masse, J. J., McNeil, C. B., Wagner, S., & Quetsch, L. B. (2016). Examining the efficacy of parent–child interaction therapy with children on the autism spectrum. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(8), 2508–2525.

Mazurek, M. O., Kanne, S. M., & Wodka, E. L. (2013). Physical aggression in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(3), 455–465.

Niec, L. N., Barnett, M. L., Prewett, M. S., & Shanley Chatham, J. R. (2016). Group parent–child interaction therapy: a randomized control trial for the treatment of conduct problems in young children. Journal of consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(8), 682.

Niec, L. N., Hemme, J. M., Yopp, J. M., & Brestan, E. V. (2005). Parent-child interaction therapy: the rewards and challenges of a group format. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 12(1), 113–125.

Nieter, L., Thornberry, T., & Brestan-Knight, E. (2013). The effectiveness of group parent–child interaction therapy with community families. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(4), 490–501.

Osborne, L. A., & Reed, P. (2009). The relationship between parenting stress and behavior problems of children with autistic spectrum disorders. Exceptional Children, 76(1), 54–73.

Ozonoff, S., Goodlin-Jones, B., & Solomon, M. (2007). Autism Spectrum Disorders. In E. J. Mash & R. A. Barkley (eds.), Assessment of Childhood Disorders (pp. 487–525). New York: Guilford.

Patterson, G. R. (1982). Coercive family process (Vol. 3). Eugene, OR: Castalia Publishing Company.

Pardini, D. A., Fite, P. J., & Burke, J. D. (2008). Bidirectional associations between parenting practices and conduct problems in boys from childhood to adolescence: the moderating effect of age and African-American ethnicity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(5), 647–662.

Pelham, Jr, W. E., & Fabiano, G. A. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 37(1), 184–214.

Peters-Scheffer, N., Didden, R., Korzilius, H., & Sturmey, P. (2011). A meta-analytic study on the effectiveness of comprehensive ABA-based early intervention programs for children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(1), 60–69.

Postorino, V., Sharp, W. G., McCracken, C. E., Bearss, K., Burrell, T. L., Evans, A. N., & Scahill, L. (2017). A systematic review and meta-analysis of parent training for disruptive behavior in children with autism spectrum disorder. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 20(4), 391–402.

Research Units on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Autism Network. (2002). Risperidone in children with autism and serious behavioral problems. New England Journal of Medicie, 347(5), 314–321.

Reynolds, C. R., & Kamphaus, R. W. (2004). BASC-2: Behavior assessment system for children. Bloomington, MN: Pearson Assessments.

Roberts, C., Mazzucchelli, T., Taylor, K., & Reid, R. (2003). Early intervention for behaviour problems in young children with developmental disabilities. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 50(3), 275–292.

Rutter, M., Le Couteur, A., & Lord, C. (2003). Autism diagnostic interview-revised (pp. 30). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services.

Shelton, K. K., Frick, P. J., & Wootton, J. (1996). Assessment of parenting practices in families of elementary school-age children. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 25(3), 317–329.

Stevens, M. C., Fein, D. A., Dunn, M., Allen, D., Waterhouse, L. H., Feinstein, C., & Rapin, I. (2000). Subgroups of children with autism by cluster analysis: A longitudinal examination. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(3), 346–352.

Solomon, M., Ono, M., Timmer, S., & Goodlin-Jones, B. (2008). The effectiveness of parent–child interaction therapy for families of children on the autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(9), 1767–1776.

Tomanik, S., Harris, G. E., & Hawkins, J. (2004). The relationship between behaviours exhibited by children with autism and maternal stress. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 29(1), 16–26.

Wechsler, D. (2012). Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence. 4th edn. San Antonio: NCS Pearson.

Werba, B. E., Eyberg, S. M., Boggs, S. R., & Algina, J. (2006). Predicting outcome in parent-child interaction therapy: success and attrition. Behavior Modification, 30(5), 618–646.

Zaidman-Zait, A., Mirenda, P., Duku, E., Vaillancourt, T., Smith, I. M., Szatmari, P., & Zwaigenbaum, L. (2017). Impact of personal and social resources on parenting stress in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 21(2), 155–166.

Zlomke, K. R., Jeter, K., & Murphy, J. (2017). Open-trial pilot of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 39(1), 1–1.

Author Contributions

R.R. designed and executed the study, completed data analysis, and wrote the paper. P.G.: mentored the execution of the study, collaborated with the design and writing of the study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

Florida International University provided IRB approval for the current study. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ros, R., Graziano, P.A. Group PCIT for Preschoolers with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Externalizing Behavior Problems. J Child Fam Stud 28, 1294–1303 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01358-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01358-z