Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to determine the current percentage of United States (U.S.) assisted reproductive technology (ART) clinics offering sex selection via pre-implantation genetic screening (PGS) for non-medical purposes.

Methods

The authors conducted website review and telephone interview survey of 493 U.S. ART clinics performing in vitro fertilization (IVF) in 2017. Main outcome measures were pre-implantation genetic screening (PGS)/pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) practices and non-medical sex selection practices including family balancing.

Results

Of the 493 ART clinics in the USA, 482 clinics (97.8%) responded to our telephone interview survey. Among all U.S. ART clinics, 91.9% (n = 449) reported offering PGS and/or PGD. Furthermore, 476 clinics responded to survey questions about sex selection practices. Of those ART clinics, 72.7% (n = 346) reported offering sex selection. More specifically among those clinics offering sex selection, 93.6% (n = 324) reported performing sex selection for family balancing, and 81.2% (n = 281) reported performing for elective purposes (patient preference, regardless of rationale for the request). For couples without infertility, 83.5% (n = 289) of clinics offer sex selection for family balancing and 74.6% (n = 258) for non-specific elective reasons.

Conclusions

The majority of U.S. ART clinics offer non-medical sex selection, a percentage that has increased substantially since last reported in 2006.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The use of pre-implantation genetic screening (PGS) to select the sex of a future child during reproductive treatment is a topic of increasing public debate. This likely reflects increased utilization and public understanding of assisted reproductive technology (ART) and growing media coverage. Genetic screening technology has been used since the early 1990s when its purpose was primarily to identify embryos carrying genetic diseases prior to transfer in in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycles [1]. This procedure involving embryo biopsy and genetic analysis can be used to detect single gene disorders, such as cystic fibrosis or sickle cell disease, and also to ascertain chromosome type (X or Y) and quantity [2, 3]. The technology has evolved over the last decade; both the accuracy and precision have improved significantly. The testing can now relay detailed genetic information rather than just global chromosome presence or absence.

While determination of sex was not the original intent of this technology, many centers in the USA offer sex selection as part of IVF with PGS. This is termed non-medical sex selection, as these couples do not have genetic diseases they wish to avoid passing to their offspring. Indications for non-medical sex selection include “family balancing” (to have a child of the opposite sex of previous offspring) and personal preference (opting to have either a male or female child for the unique experience of raising a child of one sex or another). Couples with infertility who already require IVF or couples without infertility who are purely interested in sex selection may approach fertility clinics requesting IVF with PGS and sex selection. As with any intervention, undergoing IVF and performing PGS are associated with additional financial and potential medical risks. Sex selection for non-medical purposes also introduces significant ethical considerations that are not the focus of this manuscript [4, 5].

Given the evolution of technology for PGS and the increasing use of PGS in recent years, an update on current practices is warranted. The most recent survey identifying the percentage of U.S. ART clinics offering non-medical sex selection via PGS was completed in 2006 and published in 2008. It reported that, of the 186 respondent clinics, 42% allowed for non-medical sex selection. Around half of those clinics offered the practice electively and the other half only for family balancing [1]. The purpose of this study was to identify the percentage of U.S. ART clinics offering non-medical sex selection in 2017, as well as to characterize the clinics in comparison to those not offering sex selection.

Materials and methods

Compiling the list of U.S. ART clinics

The initial list of clinics was obtained from the Center for Disease Control (CDC) 2015 Fertility Clinic Success Rates Report clinic tables [6]. Clinic addresses, telephone numbers, and CDC reporting status were then obtained from the CDC’s 2014 ART Fertility Clinic Success Rates Report (464 clinics total) [7]. To find additional clinics that do not report to the CDC, this list was supplemented by searching through fertility clinic resources at FertilityAuthority.com and Infertility Resources [8, 9]. This added an additional 28 clinics. Once this initial list of 492 clinics was created, an online search of each clinic was done to obtain the clinic website URL and to verify the clinics were still operational in 2017. The list was then cross-referenced with the Preliminary Clinic Summary Report for 2015 of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology (SART) member clinics [10]. Five additional clinics were added to this list that reported to SART but not to the CDC in 2015. The final list contained 497 ART clinics in the USA and Puerto Rico.

Each clinic’s location was defined by one of the four geographic regions (West, South, Northeast, Midwest) of the U.S. Census Bureau [11]. Puerto Rico is part of the territories in this classification and thus not a part of the above regions. Each clinic’s city was then characterized by population, with urbanized being > 50,000 inhabitants, urban cluster 2500–50,000 inhabitants, and rural < 2500 inhabitants, as based on 2010 U.S. Census data or 2000 U.S. Census data if the former was unavailable [12, 13]. This was obtained using online records available via CensusViewer [14].

Data on PGS cycles performed and live birth rates were obtained from both the CDC’s 2015 Fertility Clinic Success Rates Report clinic tables as well as the preliminary 2015 data from SART member clinics [6, 10]. Variables abstracted from the CDC report were total number of IVF cycles reported by each clinic and fresh non-donor egg live births per 100 transfers in women less than 35 years of age. Live birth rates (LBRs) are reported to give perspective on likelihood of treatment success per transfer among patients under age 35 at each clinic.

Online web search

Once the clinic list was compiled, each clinic’s website was searched for information regarding sex selection. If the website had information on sex selection it was categorized as either: (1) information only (educational information for patients that did not state directly if the service was offered at their clinic), (2) family balancing only, or (3) elective (non-medical sex selection for patient preference, regardless of the rationale for desiring the procedure). An additional task of the online web search was to determine the designation of each clinic as part of an academic, private, or government/military center.

Telephone interview survey

Clinic telephone numbers were gathered from the CDC 2014 National ART Fertility Clinic Success Rate Report [7]. Answers to the three interview survey questions (below) were obtained from a representative from each clinic. Throughout the telephone interview process, no identifying data of the interviewee answering the survey were recorded. Representative interviewees from each clinic were typically schedulers, receptionists, or new patient coordinators. Although they had specific knowledge of the answers to these questions the majority of the time, if they did not know this information, they would often ask another team member, such as a nurse, embryologist, or lab director. If no representative was available to speak at the time or the interviewer was sent to a voice messaging system, the clinic was called again at a later date.

The average telephone conversation time was 1–6 min depending on if the interviewee had personal knowledge of the answers to the survey questions. The questions were framed as asking about the services offered at the clinic in the third person. The interviewer did not state that they were a prospective patient at any time. If the interviewee asked what the purpose of the call was, the interviewer stated she was a medical student performing a national survey of fertility clinic practices. The telephone interview survey was conducted by two fourth-year medical students from the Emory University School of Medicine. The interview question script was followed as closely as possible for each telephone call, with changes being made to ask additional questions or change the wording of questions on a case by case basis. These further questions made all attempts to decrease the use of medical jargon for further clarity. The interview would be truncated early if the clinic reported they did not offer PGD/PGS or did not offer sex selection.

If in the event the clinic was unable to be reached after three attempts at calling, or if the answer on the first attempt was either “I don’t know that answer” or “one would need to discuss this in a consultation with the doctor,” an e-mail was sent to the clinic as the last measure to receive answers to the survey. This e-mail address was obtained directly from the clinic website. The e-mail contained similar questions to the telephone interview survey. If no answer or response was obtained, the clinic was classified as “unable to be reached.”

Interview questions

-

1.

“Do you offer PGD or PGS?”

-

a.

If answer no, this concluded the interview

-

b.

If interviewee unclear, interviewer asked instead: “Do you offer genetic testing of embryos?”

-

a.

-

2.

“Do you offer sex or gender selection?”

-

a.

If answer no, this concluded the interview

-

b.

Is answer yes, follow-up question asked: “Is that in all cases electively or only specific ones such as family balancing?”

-

i.

If interviewee unclear as to what is meant by family balancing, interviewer stated: “When you have children of one sex already and you want to have one of the opposite sex.”

-

i.

-

a.

-

3.

“Lastly, if someone did not have difficulty getting pregnant, in other words they didn’t have an infertility diagnosis, but they were interested in sex selection or family balancing with IVF, could that be done at your clinic?”

IRB status

This project was submitted for IRB review at Emory University and determined to be exempt, as it did not meet the criteria for research on human subjects as determined by Emory University’s Institutional Review Board policies and procedures.

Statistical analysis

Regression analyses were completed using the Wald chi-square test and the LOGISTIC procedure probability model to generate odds ratios, 95% CIs, and P values. This included a univariate regression model to analyze for significant associations. Analysis was used to determine correlation between the following variables: sex selection (yes/no) and geographic region, clinic designation (academic/private), CDC/SART reporting status, average city population, total number IVF cycles, and LBR in women < 35.

Results

Characterizing U.S. ART clinics

In total, a list of 497 fertility clinics in the USA and Puerto Rico was compiled at the beginning of the study. Only 493 clinics were included in the final analysis as 4 clinics were no longer operational. The 493 clinics were characterized as described in the “Materials and methods” (Table 1). The response rate of the survey was 97.8%, as 11 (2.3%) clinics were not able to be reached. A small portion of clinics that were reached (10.1%, n = 50) were unable to definitively answer the survey questions, responding either that they “did not know the answer” or that “one would need to set up an appointment to discuss this with the doctor” to one or multiple of the survey questions. Within that portion of clinics, six of them were unable to answer the questions related to sex selection. Given this, the final number of clinics that were able to be surveyed about sex selection was 476 clinics.

The majority of the 493 U.S. ART clinics (91.1%, n = 449) offer PGD and/or PGS services. The majority also report to both CDC and SART (75.7%, n = 373), while only 5.7% (n = 28) of clinics report to neither entity. U.S. ART clinics are widely spread between the four geographic regions of the USA, with the most (n = 162) located in the South and the least (n = 92) in the Midwest. Across geographic regions, the South was least likely to offer PGD/PGS services (87.0%). The large majority of clinics (75.5%, n = 372) are based in urban areas, with a mean city population of 702,036 inhabitants among all cities where fertility clinics are located. Among the different clinic designations, 80.1% (n = 399) were private centers, 17.9% (n = 88) academic, and 1.2% (n = 6) government or military facilities. The mean number of IVF cycles performed across these clinics, according to the 2015 CDC data, was 503 cycles. Based on CDC data, the average LBR in women age < 35 with fresh non-donor eggs was 41.95%.

Online web search results

The online website search found that 31.6% (n = 156) of the 493 clinics had information on their website regarding sex selection (Table 1). Of the 156 clinics, 27 websites (17.3%) presented information on the method and procedure of sex selection without stating whether or not the clinic would provide that service. In contrast, 51.9% (n = 81) presented information specifically on family balancing and stated they would provide this service to patients. Lastly, 30.1% (n = 47) presented information on both elective non-medical sex selection and on family balancing, stating they would provide this service to patients regardless of their specific circumstances or reasons for wanting to pursue sex selection.

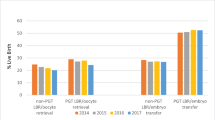

Telephone interview survey results

In the analysis of which clinics offered non-medical sex selection, only those answering survey questions on sex selection (n = 476) were included and characterized (Table 2). Among these clinics, 95.1% of private and 87.2% of academic clinics offered PGD and/or PGS. In terms of IVF cycle volume, 100% of those clinics with > 499 IVF cycles/year offered PGS. Overall, 72.7% (n = 346) of these clinics responded yes when asked “Do you offer sex or gender selection.” Among clinics that offer PGD/PGS (n = 449), 77.3% offer non-medical sex selection. Of the clinics that offered non-medical sex selection, 93.6% (n = 324) reported offering sex selection for family balancing. Among the remaining 6.4% that reported offering sex selection but not family balancing, the majority (5.8%, n = 20) responded either that they did not know the specifics of sex selection at their clinic or that were unwilling to divulge the specifics outside of a physician consult. The remaining two clinics (0.8%) reported that they did not offer family balancing specifically but rather offered non-medical sex selection at the patient’s discretion on a case by case basis. Among clinics that offered non-medical sex selection, 81.0% (n = 281) did so without restrictions; in other words, the service would be offered to any couple wishing to pursue the procedure electively regardless of their rationale. If couples did not have infertility, 83.5% (n = 289) of clinics offering sex selection stated they would offer sex selection for family balancing, while 74.6% (n = 258) stated they would offer it for elective purposes. As evidenced by these results, less clinics offer elective sex selection than offer family balancing, and less clinics offer sex selection in general for fertile couples.

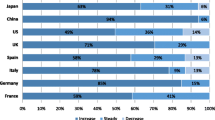

In comparing clinic practices, there was also a difference among which centers were more likely to offer sex selection (Table 3). Of the four government/military surveyed, none offered sex selection. The practice of sex selection was significantly lower in academic practices (n = 84) than among private centers (n = 388) (p < 0.01, 95% CI 0.14–0.37). Clinic practices of sex selection also varied across the geographic regions of the USA (Fig. 1). The West and Northeast had the highest percentage of clinics offering sex selection, 89.0 and 78.6%, respectively. Rates were lower in clinics in the South and Midwest, with 63.5 and 60.9% offering sex selection, respectively. There was a significant correlation between geographic region and offering of sex selection, with the West more likely than each other geographic area to offer sex selection (p = 0.03). Clinics offering sex selection were located in cities with a larger average population (around 830,000), whereas clinics that did not offer sex selection were in cities with a smaller average population (around 380,000); however, this difference was not found to be statistically significant (p = 0.77).

Clinic offerings of sex selection by geographic region. This image shows the clinic offerings of sex selection in the four U.S. Census geographic regions (Northeast, Midwest, West, and South). Underneath each geographic region labeled on the map, the overall percentage of clinics in each region offering sex selection in general is presented. Adjacent to the map, further information is presented on the percentage of clinics in each region offering sex selection in four different scenarios as specified by the figure legend. This image is adapted from Census.gov. Geography atlas: regions. Washington (D.C.): United States Census Bureau. Available at: https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/webatlas/regions.html. Accessed June 25, 2017 [15]

Although only 25 clinics did not report to the CDC or SART, 80.0% (n = 20) of those clinics stated they would offer sex selection in general (Table 3). Of the 84 clinics reporting to the CDC alone (and not SART), 66.7% (n = 56) stated they would offer sex selection. Of the clinics that report to both CDC and SART (n = 363), a lower percentage (73.3%, n = 266) stated they would offer sex selection in general. The correlation between clinic reporting status and the offering of sex selection was not statistically significant (p = 0.51).

Looking at abstracted CDC data among clinics surveyed, there was no statistically significant difference in the IVF cycle volume performed between clinics that did or did not offer sex selection (p = 0.26). There was also no statistically significant difference in average LBRs among clinics that do or do not offer the practice (p = 0.49), using CDC data. When clinics with low IVF cycle volume were excluded (< 20 transfers per year of fresh non-donor eggs to women < 35, there was an association between clinics performing sex selection and LBR such that for every 1% increase in LBR, the likelihood of offering sex selection decreases by 2.4% (p = 0.03). Both clinics offering and not offering sex selection had average live births ranging from 44 to 46%.

Discussion

Of the 476 functional ART clinics in 2017 in the USA who were reached by our survey, 72.7% offer sex selection. Clinics offering sex selection were more likely to be private centers and/or located in the West or Northeast. Clinics less likely to offer sex selection were more likely to be academic centers and/or located in the South or Midwest. While only geographic region in the West and private clinic designation were significantly associated with increased likelihood of offering sex selection, it is important to note that sex selection is offered in nearly half of all academic centers, and over half of all private centers and of each geographic region of the USA. There was no statistically significant difference between clinics offering sex selection and those not offering in terms of IVF cycle volume or average LBR based on CDC data.

The data from this survey shows an increase in the practices of both PGD and sex selection among U.S. ART clinics when compared to the previous survey of PGD practices published in 2008 by Baruch et al. [1]. This previous study was an online survey sent in 2006 to 415 U.S. ART clinics, with a response rate of 45% (n = 186). Respondents were medical, IVF, or laboratory directors at their respective clinics. Of the responding clinics, 74% (n = 137) offered PGD services, and, among those, 42% (n = 57) offered non-medical sex selection and 58% offered medical sex selection to prevent transmission of X-linked diseases. They found that PGD was more commonly offered in SART member clinics (74 vs. 67% in non-members), private clinics (80 vs. 64% in academic), and large IVF volume clinics (100% in clinics with > 499 IVF cycles/year in 2005). These same findings were replicated in our study, with an increase in the percent of clinics offering PGD in each category. In the intervening years, there has also been an increase in PGD offerings from clinics with a lower IVF cycle volume. From 2006 to 2017, the percent of clinics with 0–99 IVF cycles/year that offer PGD increased from 52 to 75.3% and among clinics with 100–499 cycles/year from 77 to 97.0%. The previous study only compared clinic characteristics with offerings of PGD, not with offerings of non-medical sex selection.

Among the 42% of clinics offering non-medical sex selection in the previous study, Baruch et al. further characterized that 47% performed it electively for parental preference, while the other half did so either exclusively for family balancing (41%) or if an infertile couple had a medical indication necessitating the use of PGD (7%). Given that this study directly surveyed medical or laboratory directors, they were also able to elaborate on the specifics of individual clinic’s sex selection practices. They reported that 10% of clinics would never reveal the sex of the embryos to be transferred, 30% would only reveal if the couple asked to transfer a specific sex, and 35% would inform the couple of the sex and then transfer based on parental preferences. Our study shows that both the practices of PGS/PGD and of sex selection have greatly increased since 2006. Overall, the percentage of clinics offering PGS/PGD technology has increased by 17.9%, and the percentage of clinics offering non-medical sex selection has increased by 30.7%. The current study shows an increase of 31% in the practice of sex selection for family balancing, as 72% of all U.S. ART clinics offering PGD/PGS will provide sex selection for family balancing in comparison to the previously reported 41%. The current study also shows an increase of 17% in the practice of elective sex selection, as now 62% of all U.S. ART clinics offering PGD/PGS will provide sex selection electively in comparison to the previously reported 47%. It is clear from this comparison that the practice of sex selection among U.S. fertility clinics has grown considerably in the last decade.

This study is strengthened by the very high ART clinic response rate. By using a short survey and contacting those clinic representatives who were most accessible by telephone, the majority of clinics across the country were contacted. We also contacted each clinic multiple times (up to four) to reach the response rate of 97.8% of U.S. ART clinics. Only 2.3% (n = 11) of clinics were not able to be reached. Of the 493 clinics surveyed, only 50 clinics (10.1%) responded with the answer that they “did not know” or that “one would need to set up an appointment to discuss this with the doctor” to one or multiple of the survey questions. The response rate allows a comprehensive and current analysis of the practice of sex selection in the USA in 2017.

The brevity of the survey prevented a more detailed analysis of the criteria considered for sex selection. The study results would have been strengthened by a more in-depth survey defining specifics of sex selection practices. For example, the survey could have delved into information such as the relative percentage of PGS cycles where sex selection was performed and how many children of one sex were necessary to consider a cycle as family balancing. A survey of this nature would have been difficult to conduct over the phone and would have been more conducive to an online questionnaire with a medical or IVF lab director. The choice of interviewees in this survey, namely schedulers, secretaries, and new patient coordinators, was not clinical and thus not always able to answer the questions asked. Additionally, the study does not report pregnancy outcome data for cycles involving non-medical sex selection, as this is not currently reported at the national level.

Overall, this survey shows that a large percentage of ART clinics in the USA offer non-medical sex selection to their patients. It is possible that the increase in this offering reflects the general increase in PGS and PGD use; as more clinics offer PGS for medical purposes, clinics and patients may feel more comfortable using this technology for non-medical purposes, given that data regarding embryo sex prior to transfer has become more readily available in clinical practice. The main implication of this study is likely to be a re-evaluation by individual clinics and providers regarding their specific PGS and sex selection guidelines. Additionally, the results of this study offer an opportunity as a society to review the national data available on sex selection. It will also be helpful to have updated use information for future iterations of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine and American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ ethical guidelines regarding sex selection [4, 5].

Conclusions

Performance of sex selection for non-medical purposes remains ethically contentious. As 72.7% of clinics nationwide offer non-medical sex selection, reproductive endocrinologists must take steps toward addressing the ethical, medical, and practice pattern considerations related to its performance.

References

Baruch S, Kaufman D, Hudson KL. Genetic testing of embryos: practices and perspectives of US in vitro fertilization clinics. Fertil Steril. 2008;89:1053–8.

Hens K, Dondorp WJ, Geraedts JP, de Wert GM. Comprehensive embryo testing: experts' opinions regarding future directions: an expert panel study on comprehensive embryo testing. Hum Reprod. 2013;28:1418–25.

Mastenbroek S, Twisk M, van Echten-Arends J, Sikkema-Raddatz B, Korevaar JC, Verhoeve HR, et al. In vitro fertilization with preimplantation genetic screening. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:9–17.

Ethics Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Use of reproductive technology for sex selection for nonmedical reasons. Fertil Steril. 2015;103:1418–22.

Committee on Ethics American College of Obstetricians, Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 360: sex selection. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:475–8.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. 2015 fertility clinic success rates report: data clinic tables and data dictionary. Atlanta: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2017.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. 2014 assisted reproductive technology fertility clinic success rates report. Atlanta: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 2016. Report No.: GS-23F-8144H.

Fertility Authority. Fertility Clinics by State. New York: Progyny Inc.; 2017. Available at: https://www.fertilityauthority.com/clinics/bystate. Accessed 15 June 2017.

Infertility Resources. Lafayette: Internet Health Resources Company; 1996–2017. Available at: http://www.ihr.com/infertility/provider/fertility-ivf-clinics.html. Accessed 17 June 2017.

Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology. Preliminary Clinic Summary Report. 2015. Available at: https://www.sartcorsonline.com/rptCSR_PublicMultYear.aspx?reportingYear=2015. Accessed 25 June 2017.

U.S. Census Bureau. Geographic areas reference manual. 1994. Available at: https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/garm.html. Accessed 15 June 2017.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2010 Census Urban and Rural Classification and Urban Area Criteria. Available at: https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/ua/urban-rural-2010.html. Accessed 15 June 2017.

U.S. Census Bureau. Census 2000 Urban and Rural Classification. Available at: https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/ua/urban-rural-2000.html. Accessed 15 June 2017.

Census Viewer. Census 2010 and 2000 Interactive Maps, Demographics, Statistics, Quick Facts. Eugene: Moonshadow Mobile Inc.; 2016. Available at: http://censusviewer.com/free-maps-and-data-links/. Accessed 2 Aug 2017.

Census.gov. Geography atlas: regions. Washington: United States Census Bureau. Available at: https://www.census.gov/geo/reference/webatlas/regions.html. Accessed 25 June 2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Capelouto, S.M., Archer, S.R., Morris, J.R. et al. Sex selection for non-medical indications: a survey of current pre-implantation genetic screening practices among U.S. ART clinics. J Assist Reprod Genet 35, 409–416 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-017-1076-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10815-017-1076-2