Abstract

Long-term excavations at Arslantepe, Malatya (Turkey), have revealed the development, in the fourth millennium BC, of a precocious palatial system with a monumental building complex, sophisticated bureaucracy, and a strong centralization of economic and political power in a nonurban site. This paper reconsiders, in comparative terms, the main features and organization of the earliest states in Greater Mesopotamia. By looking at the social and economic foundations of the emergence of hierarchies and unequal relations, the dynamics and degrees of urbanization, and the role of ideology, I highlight the common aspects and the diversified trajectories of state formation and outcomes in three main core regions—southern Mesopotamia, northern Mesopotamia, and Upper Euphrates valley.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

State formation has been one of the most interesting subjects in anthropology and archaeology for many decades, and the differing theoretical approaches that have been considered raise fundamental anthropological questions. How we approach the rise of the state as a global sociopolitical system raises questions about how we define and classify a state society, with the associated issue of the very legitimacy of the classification itself of types of society, rigidly defining the assemblages of features that characterize them, regardless of their specific historical and cultural background and developments. A second major theme—closely bound up with the former—is the question of the “genetic” linkage between different types of society and, consequently, the question of the modes, causes, and forms of social change.

The success of evolutionary theories and the later emergence of neo-evolutionism certainly gave rise to the widespread adoption of classification procedures in the social sciences in the last century and brought about the tendency to construct models of society and to recognize clearly defined breaks in the processes of social change, which could allow one to identify evolutionary steps and “periods of transition.” A variety of theoretical and practical approaches linked to evolutionism, though with differing, sometimes divergent positions and perspectives, have marked the history of anthropology and archaeology over many decades (Childe 1950, 1951; Earle 1997; Flannery 1972; Fried 1967; Friedman 1979; Friedman and Rowlands 1977; Godelier 1977; Johnson and Earle 1987; Sahlins and Service 1960; Sanders 1974; Sanders and Price 1968; Service 1962, 1975; Steward 1955; Willey and Philips 1958). The New Archaeology in particular paved the way for an expansion of the evolutionist and processualist theories in archaeological practice, focusing increasingly on “primary” societies and their “origins” (Binford and Binford 1968; Flannery 1976; Flannery and Marcus 1983; Renfrew 1972; Wright 1977; Wright and Johnson 1975). Such concepts as chiefdom and state have become common and, whether we like it or not, have conditioned the debate on the birth and development of hierarchical societies and the so-called “social complexity”—a vague term that is of little use (Marcus 2008; Redmond and Spencer 2012; Wright 2006).

Criticism and reactions to evolutionist theories, which have become widespread in recent years, have rejected the validity of the classificatory approach, while attention—probably in relation to the prevailing contemporary thought in economics—has focused mainly on studying aspects of the “intentionality” and “rationality” of human actions, the role of agency, and symbolic behaviors (Dobres and Robb 2000; Dornan 2002; Hodder 1982, 1985; Pauketat 2001; Renfrew et al. 1993; Robb 2012; Saitta 1994).

Classifications and models, indeed, often fail to account for the complexity of human societies and the many different forms of social, economic, and political relations that are at the same time interwoven, harmonized, and colliding in the same communities. “Simple stage typology fails to account for variation among societies of similar complexity and scale,” as Blanton et al. have suggested (1996, p. 1). At the same time, I believe that, while accepting that universal evolutionary models are oversimplified and implausible, the origins and reasons for change are to be found in the historical roots of each society, in the socioeconomic and political relations that had preceded changes. “All of the future exists in the past” (Capote 1948, p. 113).

I think we should give relevance to those dominant social and economic relations that shape societies and sometimes also push for change, searching for the historical causality of the phenomena, and at the same time not underestimating the dialectical relationship between the needs of individuals and social demands. By social demands, I am not only referring to the demands of society as a whole for its survival and reproduction in systemic-functionalist terms, but also the sometimes conflicting needs of individual groups and social sectors within one and the same community (Bernbeck 2009). Societies are not monolithic and homogeneous wholes, and both cooperation and competition dialectically work in each society, dynamically pushing for conservation or change. By analyzing and understanding the nature of the dominant relations in each society, we can recognize their salient and characterizing features and ultimately build a variety of explanatory models, taking due account of the multiplicity and diversity of situations and evolutionary developments. As Braudel (1997a) has stated, “history” is not only the narration of events, which only reflect the “surface,” but it must be “profound history,” i.e., the history of man in the society. History (and I would add archaeology) is “explanation” and does not only analyze the life of individual men and communities, but, through the investigation of daily acts and minor and major events, it analyzes the collective life of all men; its main aim is not so much the narration of the past, but the “knowledge of man” (Braudel 1997b).

To overcome the idea of applying preconceived models that trace general evolutionary trends, the challenge for archaeologists today is to conduct pinpoint analyses of phenomena that occurred in specific time and space contexts on a new rigorous methodological basis, making use of the vast amount of new information that is increasingly gathered through field research, with the aim of providing evidence of specific developments and epoch-changing transformations in the history of societies, without relinquishing, however, the idea to go further and also attempt to understand dynamics of social change in a wider anthropological perspective.

Past models and concepts created in anthropology can be carefully reconsidered in this perspective (not necessarily discarded a priori), and new explanations can be derived from the observation of many different “formative” contexts. The study of specific “primary” situations that are wholly unknown to us can make it possible to reconstruct behaviors and dynamics of change that cannot or can only partly be known or predicted on the basis of what we know already from ethnographical or historical cases. If compared by maintaining the reference to their historical and environmental contexts, these different social realities can reveal mechanisms of social evolution and change in the specific historical and environmental contexts in which they occurred, giving rise to different possible pathways. By applying a “historical-ecological regional approach,” as defined by Wilkinson et al. (2014), we may be able to achieve that “rehabilitation of social evolutionary theory” on new bases, as suggested by Yoffee (2005, p. 21) when he emphasized the need for an archaeological exploration of “the many trajectories of social change that are documented in the archaeological record and so explain the evolution of the earliest cities, states, and civilizations.” If we eschew “classifying,” while not renouncing “characterizing” (i.e., recognizing and explaining the structural aspects and causes of the phenomena without rigidly creating universally valid “types” of society), archaeology can acquire an enormous cognitive potential and also help progress in the study and theories of anthropology. Following Feinman (1998, p. 132), we might say that “An understanding of societal change and preindustrial states requires much more than a single theory, evolutionary scenario, or set of prime movers…By endeavoring to offer bridges between history and process, this essay hopefully nudges us a small step along a long and complex road.”

The topic of the origin of the state in the Mesopotamian world is an issue that is waiting to be discussed in these terms, by trying to analyze and stress the crucial regional and sociopolitical variability that is well attested by recent field research in the northern regions of Greater Mesopotamia, as well as the specific dialectical relations pushing change in early societies, albeit in the framework of closely related developmental processes and intense interregional relations.

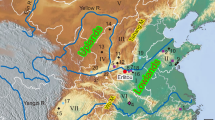

My reason for explicitly expressing these considerations is to clarify the general approach I am using to address the problems concerning the processes and the many trajectories that gave rise to politically and economically centralized societies in Greater Mesopotamia and related areas (Fig. 1), starting from the results obtained at Arslantepe-Malatya, in the Upper Euphrates Valley. I try to point out the peculiarity of the developmental trajectory and outcomes observed at Arslantepe, by comparing them with the evidence from two other important fourth millennium core regions as represented by a few major sites: Uruk-Warka in Southern Mesopotamia and Tell Brak and Hamoukar in the Khabour basin of Northern Mesopotamia.

Some Key Concepts for the Analysis of State Formation in Greater Mesopotamia

Before analyzing the historical cases, I must necessarily also make a few brief preliminary remarks regarding certain key concepts that have been widely used to discuss the rise of state societies.

Chiefdom and State

While these definitions are still among the most commonly used benchmarks and often are still the main basis of the debate on the subject matter of this paper, their inadequacy for appropriately describing complex, varied, and internally nonuniform situations has been widely perceived, so that attempts have been made to nuance these categories to better characterize the multiplicity of societies they define. Chiefdoms, for instance, have been articulated into types—e.g., simple and complex (Wright 1984) or minimal, typical, maximal (Carneiro 1981, pp. 46–48). Various terms and definitions have been adopted for analyzing the many different forms of “pristine states,” such as archaic state (Feinman and Marcus 1998) and early state as opposed to mature state, the latter subdivided by Claessen and Skalnìk (1978) into inchoate early state, typical early state, and transitional early state, which define evolutionary steps from early to mature states. This identification of different types of early states also highlights the delicate and critical problem of the distinction and relationship between chiefdom, state, and their various subcategories.

Notwithstanding the previously mentioned difficulty of reducing the complexity of historical realities to the generalizations of universal sociopolitical categories, the effort to identify distinctive features for each type of society has helped bring out crucial aspects that have become useful analytical tools, e.g., the degree of importance of kinship, community, political, or territorial ties in the governance of society; the type of economic relations; the nature and scale of social stratification; the role of administration and bureaucracy; and the role of religion and ideology.

In comparing Southern and Northern Mesopotamia and Eastern Anatolia, I look at all these factors, particularly referring to the nature of social change in connection with traditional social and economic relations, the environmental conditions influencing the economy, the organization of staple production, the dynamics of urbanization, and the ideological apparatus that supported the relations between the ruling elites and the population. I characterize and distinguish the different societies that I compare without attempting to attribute them to chiefdom, state, or other subcategory.

City and Urbanism

The extraordinary development of the power of central institutions and the organizational and production complexity of very large sites such as Uruk-Warka reveals the importance of a third conceptual category, which has been almost invariably closely related to the notion of “state”: I am referring to the category of “city,” which has been widely used and abused. The emergence of this type of settlement and human aggregation, as we know, has been considered one of the distinctive features of state formation by many scholars, ever since the first reconstruction of the development of urban society by Childe (1950). As a result, the two concepts—city and state—have often been indissolubly linked as belonging to one and the same sociological category. But these two terms define different social and political realities, which, while in some cases overlapping, do not always refer to necessarily correlated phenomena. While Adams’ (1966) use of “urban revolution” to describe a series of processes that led to the birth of the state is appropriate for Lower Mesopotamia, where the two phenomena were certainly very closely and structurally linked, there is no such correlation in other cases. Attempts to recognize different types of cities, including the proposal of “low-density urbanism” (Fletcher 2012), may certainly have helped account for the variety of situations recorded in archaeology and ethnology (Marcus and Sabloff 2008; Smith 2010; Yoffee 2014, 2015), but even in these cases the use of the term “urban” is not always fully justified. A community cannot be defined as a city purely on the basis of its population size or extension, though these are necessary requirements for characterizing it. The existence of cities entails a far-reaching transformation of the society in terms of kind of community aggregation, internal economic, social, and political relations, and its system of territorial organization.

While size is certainly one of the distinguishing features of an urban settlement (Ur 2014b), what really defines it is the association of large dimension with an internal articulation into differentiated, specialized, and interdependent parts (social and economic sectors, activities and services areas, political and religious sectors, etc.) (Fisher and Creekmore 2014, p. 4) and also a high level of internal specialization in terms of the distribution of political functions and tasks. Such a system leads to a very close involvement of the surrounding territory, based on a structural and not discontinuous relationship between the main center and neighboring sites, which can guarantee regular supplies to the specialized sectors and thereby make the territory an essential part of the whole integrated system. In this connection, Sherratt (2004, p. 101) has highlighted the fact that the “urban revolution” had a “transformative effect on the consumption habits of surrounding human population.” For Sherratt (2004, p. 101), urbanization creates “new forms of consumption and goods that cannot be described simply as ‘staples’… or ‘prestige goods’… especially in the way in which this increasingly diverse range of products broke down the previous separation between different spheres of exchange.” This emphasizes the phenomenon of the radical integration of a territory brought about by urbanization; it is not, in other words, only a matter of rural goods being transferred to the city and artisanal goods being transferred into the countryside according to a widely accepted view, but something much more profound that involves various types of interactions that combine and transform production and exchange relations. This vision also accounts for the observation made by Adams (1981), who, in his criticism of the Johnson (1975) model centered on the idea of clearly distinct functions of sites belonging to different size categories, noted the presence of craft activities and workshops even in the small sites on the Mesopotamian alluvial plain.

Such an integrated system must necessarily have presupposed institutionalized and quite sophisticated forms of central government to manage these relations, in other words, the formation of a state-type system. But it is precisely the analysis of some Near Eastern societies that were among the most ancient and primary seats of the birth of the state and the city that has shown the contrary not always to be the case. It is precisely the existence or absence of urbanization that constitutes a crucial distinctive feature of various Near Eastern centralized political systems, which determined or influenced the birth, development, and/or collapse of the pristine states within Greater Mesopotamia, as research at Arslantepe has shown.

The achievement of economic and political centralization throughout Greater Mesopotamia in the second half of the fourth millennium BC must have led the political centers to establish close relations with the territory from which they extracted staple goods and labor, thereby probably starting to define the first political borders of these territories. This integration process must have been much more marked in urbanized contexts where the very close and systematic interaction between cities and their hinterland was indispensable for the survival not only of the power centers, but of the whole system of relations between all components of the population (Emberling et al. 2015).

What Do We Mean by “State” in Early Mesopotamia?

The political and economic integration of a complex whole of differentiated and sometimes conflicting sectors is a distinguishing feature of the structure of a state and, in some cases, as in Lower Mesopotamia, links both increasing urbanization and the gradual strengthening of a central political authority, which feed on each other. Factors such as social stratification and inequality, economic privileges, a complex administrative organization, the control of a common ideology that legitimizes rulers, which have been variously used to define the characteristics of the state and to distinguish it from less-structured sociopolitical formations (Claessen and Skalnìk 1978; Service 1975), also are recognizable, in various forms and to different degrees, in some pre-state societies classified as chiefdoms (Earle 1991, 1997; Kristiansen 1991). This is particularly evident in Mesopotamian societies, where economic privileges, social inequality, and the administrative control of resources seem to have existed as early as the first half of the fourth, and even the late fifth millennium BC in the late Ubaid period. In Mesopotamia, the need for a centralized administrative system emerged with the establishment of regular “redistribution” practices, based on the centralization of primary resources in various forms (offerings, tributes) in the hands of high-ranking individuals and their reallocation in public and elite environments. This system probably ensured an effective circulation of goods from the very first occupation of the southern alluvial plain. But this kind of economic control and coordination very soon led to high-status individuals being endowed with political and religious authority. In this part of the world, then, even though economic privileges originally appear to have been camouflaged by ideology, they were probably established almost from the beginning of the occupation of the alluvium, very likely in association with a society of corporate communities characterized by hierarchical kinship relations and initial forms of centralized economic and political management in the hands of preeminent individuals (Frangipane 2007a; Ur 2014a). This is probably why Adams (2004, pp. 42–43) considered that there were no chiefdoms prior to states in southern Mesopotamia, arguing on the basis of his recognition of the existence of a codified redistribution system and “institutions” rather than simply “individuals of authoritative, chiefly status” from the fourth millennium onwards.

This shows the difficulty and the problematic character of using predetermined models and factors, or sets of factors, of the type described above to identify and distinguish the presence or absence of the “state” in widely differing and often highly complex societies. I believe it is necessary to look at the substantial changes toward the emergence of hierarchies and central power in Greater Mesopotamia as complex and varying phenomena also composed of conflicting interests in different conditions and responses to them (Bernbeck 2008, 2009).

Before we approach the analysis of socioeconomic and political formations that might be recognized as early state systems, I suggest that they should conform to a set of general criteria. They should have been highly politically integrated societies with a diversified range of components, stratified both horizontally (e.g., social groups, productive components, in some cases ethnic groups, various settlements in a territory) and vertically (e.g., hierarchically organized social categories, religious institutions, political and administrative hierarchies) (Wright 2006, p. 306; Yoffee 2005, p. 33). They also should be accompanied by a strong institutionalization of the authority, exercised by means of power delegation.

By institutionalizing the hierarchies, the centralized systems must certainly have strengthened them, hence fostering social stratification and inequality as well as the elite capacity to accumulate resources. But although the emergence of social and economic privileges must have been the necessary basis for the formation of a centralized system, this does not necessarily coincide with only one specific type of sociopolitical system, and it is not itself sufficient to be able to identify the presence of the state.

I think that one feature of the state, even in its incipient forms, is its capacity to impose authority and obtain consensus by means of intrinsic self-legitimization and a direct relationship with the people, not only channeled via ideology and religion. This is not to say that ideology did not play an extremely important role in early forms of pristine states; indeed, it was in those contexts that a system of ideas and concepts was created to support and underpin the legitimacy of the nascent authority, also using codified images and creating what has been defined as the “ideology of power.” Even though many of these concepts were often linked to a religious tradition and the supernatural world, the “king” or leader must have exercised power, albeit “delegated by the divinity,” in secular forms and places, autonomously creating his own system of rules and being represented by other delegated institutional figures vested with tasks and prerogatives. The emergence of a bureaucracy as a class of officials with delegated powers is another feature of the state.

The state also resolved conflicts, which may have increased exponentially between different competing groups and needs of a composite and stratified society, through the exercise of a recognized power and the control over an ideology that made the central institutions and the ruling class perceived not as another party in the conflict but as a regulator and benefit provider. The perception of leaders as benefit providers also was widespread in pre-state societies, but the power of early states was based on a combination of the capacity to obtain ideological consensus and the ability to impose authority and unequal social relations. The emerging state institutions ultimately were the main agents that supported the success of one of the conflicting components over the others.

Interesting hints in this respect come from the dual-processual theory elaborated by Blanton et al. (1996) for Mesoamerica. If we look at their two types of power strategy—corporate and exclusionary—as two different forms of political relations that also may have been two poles in a process of change, these concepts could potentially illustrate some aspects of the transformation of Southern Mesopotamian society from one based on large families, partly sharing power and certainly competing, to an increasingly vertical and exclusionary “political system built around the monopoly control of sources of power by a supreme authority” (Blanton et al. 1996, p. 2; see also Bernbeck 2008, pp. 540–542).

Distinctive Features of the State Formation Process in Southern Mesopotamia

Lower Mesopotamia is largely a homogeneous region in terms of its cultural and political developments, while being ecologically differentiated into micro-zones that offer different potential and resources. It is precisely the ecological differences in a restricted area, coupled with other high risk factors, such as aridity, proneness to soil salinity, and the need for irrigation and water control in agricultural practices, that probably primarily account for the early centralization of the staple economy and the emergence of systematic redistribution practices from the time those lands were first occupied (Adams 1966, 1981). The whole region also underwent early, intense urbanization and saw the emergence of religious-ceremonial institutions operating in architecturally monumental buildings already in the earliest occupation phases. There are almost no new archaeological data on Southern Mesopotamia, but the data obtained in the past on major fourth and fifth millennium sites, such as Uruk-Warka, Tello, Nippur, Abu Salabikh, Tell Uqair, Eridu, Ur, and Tell Oueili, together with the in-depth territorial surveys conducted by Adams and Wright (Adams 1981; Wright 1969, 1981), permit us to reliably speculate on the organizational, social, and economic characteristics of these societies. Substantial information in this respect also has come from studies of the pictographic tablets from the final Uruk levels at Warka (Nissen et al. 1993).

Available archaeological data on Southern Mesopotamia suggest that the alluvial plain in the sixth and fifth millennia BC was first occupied by communities whose social structure was based on extended families, judging from the dimensions and layout of the typical dwellings of the so-called Ubaid culture found at Tell Oueili (Huot 1989, 1991), as well as at Tell Abada and Tell Maddhur, in the Hamrin Valley. While these two latter sites lay outside the Mesopotamian alluvial plain, they were fully part of the Ubaid culture, which also extended as far as this region in the fifth millennium (Jasim 1989; Margueron 1987). Very large “tripartite” houses with a common central area and two lateral wings of more or less symmetrical rooms built according to highly standardized patterns suggest that they were occupied by extended and composite households who used different parts of the dwelling according to codified rules (Fig. 2a, c). In the only Ubaid village that has been fully excavated, Tell Abada (Jasim 1989), two adjacent dwellings (houses A and B) were considerably larger than the others. One of the houses had distinctive features (Fig. 2c)—buttresses on the walls, an adjacent walled area (perhaps to receive people), and a concentration of child burials underneath the floors, which might suggest that this house belonged to a preeminent family vested with the symbolic power of representing the community as a whole. All of this suggests that the Ubaid communities’ kinship system was organized along hierarchical lines of descent that must have entrenched inequalities of rank, not necessarily associated with economic privileges at first, but bringing about a sort of horizontal inequality or “vertical egalitarian system” (Frangipane 2007a, pp. 164–170, 2016, pp. 471–474). A social organization based on large families also may be inferred from the later developments of Mesopotamian society, which, according to Early Dynastic texts, appear to have been made up of hierarchically organized household corporations.

Mesopotamian buildings of the Ubaid and Uruk periods (fifth–fourth millennia BC). a: The reconstruction of a large tripartite house from Tell Oueili, Ubaid phase 0 (from Huot 1991); b: Eridu, plan of the level VII ‘temple’; c: Part of the Tell Abada village (from Jasim 1989, fig. 2). The larger tripartite houses are highlighted in gray; d: 3D perspective view of the Eanna monumental complex at Uruk-Warka (elaborated by C. Alvaro)

High-ranking figures also may have been vested with managing social, economic, religious, and political transactions. Among the special features of the main house at Tell Abada, for example, there was an assemblage of clay tokens that appear to have been very ancient accounting tools (Schmandt Besserat 1992). There is no evidence of clay sealings and administration in Southern Mesopotamia in the early Ubaid phase, to which the village of Tell Abada belonged, but the concentration of tokens in the large house may mean that preeminent individuals (the chief and his family?) who may have lived there had been endowed with certain prerogatives that included the authority to coordinate or effect transactions of some kind.

We have no evidence in this respect from the southern alluvial sites, which were excavated a long time ago and over very small areas from these earliest periods. But it was there that “temples” or ceremonial buildings had been erected at Eridu. The temples had a tripartite layout similar to that of the houses, but with distinctive features: a monumental character, a raised basement, a complex decoration with buttresses and recesses in the walls, and a different internal distribution of spaces. They were dominated by a large central room that likely was used for public gatherings and that also contained two platforms, probably “podia” for ceremonies and public banquets (Safar et al. 1981) (Fig. 2b). Whether or not these buildings were used for cultic purposes in the strict sense of the term, as Forest (1987) maintained, they were certainly ceremonial buildings designed for public gatherings and were probably used for ceremonial food distributions. Evidence of this includes, among other things, the well-known finding of plentiful fish bones in the side room of one of the late Ubaid phase buildings at Eridu (Adams 1966; Frangipane 1996). It is quite likely that these buildings were the places where high-ranking personages, perhaps community leaders, conducted ritual and other public ceremonies.

The iconography of the most recent Late Uruk seals (end of the fourth millennium) reveals the close relationship between the priest/king, the temple, and the public and ceremonial management of foodstuffs (Fig. 3a–c); these are the three key elements of the centralized power system that typified fourth millennium Mesopotamian society. Their roots probably lie in the original social and economic structure of those communities in the previous Ubaid period. Late Uruk glyptics ideologically emphasized the offerings to the temple, namely, the incoming goods used to fuel the circuit hinging around food redistribution. This circuit, which was originally ritualized and perhaps only designed for the redistribution of certain goods in the 5th millennium, must have become an entrepreneurial system under which many items entering the system were used to support an increasingly large number of individuals, investing in labor and consequently in the production of new goods.

It is no coincidence that this system, which spread throughout the whole of the so-called Greater Mesopotamia, originated in the southern alluvial plain where the environment was precarious, with serious aridity and different types of soils in terms of crop yields—some were more seriously affected by swampy marshes and a high water table that, at high temperatures, caused soil salinization. The area also was endowed with vast plains that, with a few technical strategies (irrigation, excess water management), were able to offer huge potential for expanding agricultural production, particularly of cereals. This environment must have favored the birth of social kinship systems that legitimized unequal access to lands and resources varying in quality, while at the same time guaranteeing the circulation of those resources and the coordination of critical subsistence activities managed by individuals vested with legitimate authority to perform them. Ideological and, above all, religious legitimation of the authority and its right/duty to manage “public affairs” and to intervene in substantial aspects of the staple economy must have been a crucial means of ensuring the working of the whole system and its political and social solidity (Aldenderfer 2012; Godelier 1977, ch. IV.1).

Effective social inequality, the privileged status and prestige of the chiefs, and their strong ideological legitimization would have made the redistribution circuit expansive, probably triggering a self-feeding growth and transformation process: increasing centralization of food for redistribution, growing numbers of increasingly poorer people needing to be supported by receiving that food, expanding prestige and power vested in the leaders, the offer of labor and services in exchange for food, and the leaders’ need to accumulate means of production with the resultant increasing demand for more labor. Social inequality must thereby have led very soon to developing economic inequality and the concentration of political power (Frangipane 2016).

Even at the end of the fourth millennium, when the leaders had acquired huge power and already controlled an enormous variety and quantity of goods and economic transactions, managing them in public areas with the help of a sophisticated administrative system, the context and the legitimization of that power continued to have predominantly cultic connotations. This is clear in the large city of Uruk-Warka, not only for the areas specifically set apart for cultic purposes, such as the so-called White Temple, where no economic/administrative activity was performed (Nissen 2015), but also in the very large area of Eanna; among the numerous architecturally diverse buildings of Eanna that in all likelihood were used for various economic/administrative and political activities were other large and monumental structures that possess all the typical features of Mesopotamian classical temples (Butterlin 2012; Eichmann 2007).

Another significant feature of these Mesopotamian societies is the fact that social hierarchies are not reflected in burials and funerary rituals. The Ubaid period cemeteries at Ur and Eridu show no signs of any differentiation in terms of funerary gifts or burial customs and seem to reveal a process of ideological obliteration of the differences, which were on the other hand manifested in houses and temples (Pollock and Wright 1987, pp. 324–328). Very few burials of the Uruk period have been found, and the few known examples also show very little differentiation. One might infer, as Stein (1994, p. 43) has suggested, that leaders in the Ubaid period wanted “to emphasize their group membership, while downplaying intra-group differentiation,” by removing any display of status and economic differences, thereby reinforcing the perception that they were part of the community, performing tasks to the people’s advantage and distributing benefits. That also might explain the scant importance ascribed to funerary ideology in the Uruk period, as it was not intended to display the true social order or emphasize the privileged position of the elites. This kind of ideology has been correlated with strategies chiefly based on staple finance, in which the upholding of kinship ties may have been “the most effective way to mobilize labor and surplus staples from commoners” (Stein 1994, p. 43; see also Earle 1991).

In reality, this type of relationship between the elites and commoners in a context like Mesopotamia gradually increased the economic power and privileges of the elites and widened the inequality gap. The leaders’ capacity to centralize labor, remunerating it with staples, appears also to have led to an increasing ability to centralize the means of producing those staples (land and livestock) and to control the overall production system, perhaps including some craft production, as may be inferred from the huge concentration of mass-produced bowls in public areas as well as from information gleaned from the Uruk IV-III administrative and lexical texts. This must have entailed an increasingly more intense involvement of the territory surrounding the seats of the political, religious, and administrative institutions, while at the same time attracting an increasing inflow of people toward those seats, where activities and opportunities also were concentrated.

Urbanization therefore played a key role and was one of the distinctive features of Lower Mesopotamian society. There already may have been some large and highly populated centers in the alluvium as early as the fifth millennium BC (Adams 1981), even though there are no excavations that provide accurate information on the dimensions of the sites apart from the observation of scattered surface materials. But urbanization was certainly fully accomplished by the fourth millennium, with sites covering more than 40–50 ha and the main center of Uruk-Warka occupying an area of between 70 and 100 ha in Early Uruk (first half of the fourth millennium) and reaching an unparalleled 200 ha or more in Late Uruk (second half of the fourth millennium) (Adams 1981; Algaze 2008; Nissen 2015; Pollock 2001).

Such large sites would have needed an organization comprising specialized and interdependent sectors and a very powerful political authority that was able to integrate all of the parts and to keep them firmly together. I also think that centers of such proportions could have existed and developed only in environments with an agricultural economy capable of producing sufficient food to feed so many people.

The use of administrative tools was the essential key to ensuring economic control over the circulation of goods and political control over the people who were party to those transactions. In the fourth millennium, administrative technologies had developed enormously in terms of quantity and quality, with the introduction, besides cretulae (clay sealings) for sealing containers and doors, of other administrative instruments that met many varied needs related to the substantial increase in the number of operations and stages in the accounting and recording processes: hanging ovoid cretulae, spherical bullae that often contained tokens, “complex” tokens that increased the number of signs and hence the information to be conveyed (Fiandra and Frangipane 2007a; Schmandt Besserat 1992). Increased numbers of administrative tools and the need to extend control to a larger number of players, and perhaps to the rural environment surrounding the cities, certainly entailed the rise of a bureaucracy and numerous officials—as evidenced by the large numbers of different seals—to whom the ruling class could delegate authority. Administration and bureaucracy provided the authorities with the capacity to exercise intrusive political and economic control.

By the mid-fourth millennium at the latest, in the Middle and Late Uruk phases, all of the elements that we have defined as characteristic of a pristine state system were already in place in southern Mesopotamia.

Institutionalized and centralized economic power interfered in the general production and circulation systems by accumulating staples, and possibly the means of production, by controlling the labor force, and by allocating goods through routine redistribution.

Ideological control of the social order is revealed by imagery in glyptics and art works, including the famous Uruk alabaster vessel (Schmandt Besserat 2007, pp. 41–46) and the iconography of the King-Priest in seals, as well as by the impressive monumentality of temples and ceremonial buildings that were the main seats of power. Even the depiction of prisoners in thrall to the King-Priest in the Late Uruk glyptics (Amiet 1961; Brandes 1979) (Fig. 3c, d) may not necessarily depict prisoners of war; they also could be a more general portrayal of individuals in an attitude of submission to the chief to ideologically express or reinforce his power and authority over the population, including his capacity to use violence (Bernbeck 2009, pp. 51–52; Nissen 2015, p. 120).

Political power was expressed by (1) an authority legitimized to impose obedience, by using ideological and/or physical force, as suggested by the imagery in glyptics and by the impressiveness and huge size of the places in which the leaders performed their public functions; (2) the need and ability to delegate this power to other officials—the bureaucrats—to minister “state business” on behalf of the rulers, making it possible for them to gradually expand their control in terms of organizational effectiveness and the numbers of people and territories involved. This is shown from the concentration of administrative materials in public areas and in various minor sites in the territory (Wright et al. 1980), the extraordinary large number of different seals (increased number of officials and individuals with administrative responsibilities), and the variety of sealing practices and recording tools (Amiet 1961; Boehmer 1999; Brandes 1979).

Social power appears to have been underpinned by a hierarchically organized social structure from the beginning, in which the legitimacy of the leaders must have come from the very fact that they were also high-rank individuals, as evidenced by the probable existence of high-status persons as early as the beginning of the Ubaid period (late sixth and early fifth millennia BC). Here again, social hierarchy complexity must have expanded still further in the fourth millennium with the emergence of the new class of bureaucrats who were very closely linked (ideologically and perhaps by kin ties) and dependent on those in whose name they operated.

Three major aspects linked to this new structure of political, social, and economic power characterized the new type of society in southern Mesopotamia: a high level of urbanization, which, judging from the evidence found in various surveys, seems to have begun very early (Adams 1981); the early foundation of a hierarchical social structure; and the extremely important part played by ideological/religious mediation, which still seems to have featured the exercise of power in Lower Mesopotamia at the end of the fourth millennium and beyond.

Diversified Pathways to Centralization in Northern Mesopotamia

While Northern Mesopotamia generally has better conditions for agriculture, having sufficient rainfall for dry farming, its territory is extremely varied and differs from Southern Mesopotamia in terms of the extension of the arable land, which is really large only in the Khabour region. Much recent research conducted in the northern regions of Greater Mesopotamia has produced new and important information of relevance to the earliest states, particularly investigations in the Khabour basin and eastern Jezira, at sites such as Tell Brak and Hamoukar (Gibson et al. 2002; McMahon and Oates 2007; Oates and Oates 1993, 1997; Oates 2002).

The territory of Northern Mesopotamia was by no means homogeneous, not only in terms of environmental features, but also in terms of settlement patterns, organizational features, and cultural developments (Wilkinson et al. 2014). In very general terms we can distinguish between the plains and hilly steppes of Upper Mesopotamia proper, coinciding roughly with the Syro-Iraqi Jezirah and characterized by a certain degree of cultural homogeneity in the Late Chalcolithic; the Middle Euphrates Valley, which today runs partly through Syria and partly through Turkey as far as the Taurus range, in which the communities, despite their close relations with the Jezirah sites, had a different territorial organization and also exhibited clearly visible cultural differences, depending on the periods; and the Middle Tigris Valley and the areas adjacent to the Zagros foothills, which have been less thoroughly investigated than the other two zones in recent years and therefore offer few truly reliable data (Fig. 1).

All of these areas were linked and homogenized by the spreading of the so-called Halaf culture throughout the sixth millennium BC, which was perhaps conveyed by the multiplication of small and demographically growing communities (Nieuwenhuyse et al. 2013). This phenomenon seems to have created a common, shared cultural substrate, despite regional differences that continued to live on. In the fifth millennium, the pressure from Ubaid communities to interact with these groups, perhaps also accompanied by movements of people, found a relatively homogeneous area and produced a radical change in the social, economic, and political structure of the northern communities (Frangipane 2007a, 2015). A new type of hierarchical society came into being, albeit with subregional variations, that was very different from the earlier Halaf society. New elites started centralizing and redistributing staples, apparently even in their own houses, which in some cases were large, tripartite buildings according to Southern Mesopotamian models. Emblematic examples are the settlements of level XII at Tepe Gawra, east of the Tigris, and the village of Değirmentepe on the Upper Euphrates (Esin 1994; Rothman 2002; Tobler 1950), where numerous clay sealings and seals have been found in the main houses. Administered goods and rituals in temple-like buildings also closely resembled those found in the south. The various different forms of hybridization with the local culture and adaptation to different ecological environments led, once again, to regional variations (Carter and Philip 2010), which became more marked in the early phases of Late Chalcolithic (LC 1–2, 4400–3900 BC) (Table 1). In the latter periods, clearly distinct cultural aspects and quotidian behaviors can be recognized in the Euphrates Valley and to the west, in the Balikh Valley, in central-eastern Jezirah, and along the Tigris (Marro 2012).

In the following Late Chalcolithic 3 (3900–3600 BC), a new unifying process created a more homogeneous cultural substrate throughout all of Jezirah, between the Tigris and the Euphrates, partially leaving out the regions west of the Euphrates and north of the Taurus Mountains, which retained their own characteristics. This unifying process in the Northern Mesopotamia plains accompanied the development of the first truly urban centers in the Khabour region and the consolidation and expansion there of a centralized, redistributive system based on staple resources and labor. This system had first been brought into existence in the north in the fifth millennium BC and characterized the whole Mesopotamian world in the fourth millennium. It is possible that it was precisely the political pressure of the expanding urban centers in the Khabour that drove this process of cultural unification of the whole Jezirah in LC3.

Social and Economic Structures

The differences in cultural aspects and daily habits between populations in the Euphrates Valley and those in Jezira proper must have depended on radical structural differences between them. This was perhaps partly due to their different social and household structure, which still may have retained their original features and family habits that were based on nuclear families in the Euphrates region (except for the colonial sites), as evidenced by both the dimension and shape of the houses and cooking and eating habits (Balossi Restelli 2010). Conversely, the social structure of the Jezira societies seems to have changed more radically, perhaps due to their closer interaction with the Ubaid world.

The differences between communities in the Middle and the Upper Euphrates Valley also must have been linked to their different ecological and environmental contexts, which led to a different organization of the subsistence economy and territorial arrangements. The lack of wide-ranging plains and the presence of mountains probably prevented a sufficient expansion of agriculture to support the formation of large urban centers with a high concentration of people, while the environmental diversity appears to have encouraged the economic integration of such various components as sedentary farming communities and mobile pastoralist groups. This integrated and dichotomous system with good agriculture but limited expansion potential, together with a simpler social kinship structure that was perhaps internally less competitive than Mesopotamia’s (nuclear families cooperating rather than large families often competing with one another), must have reduced the potential for developing stable and solid stratified, diversified, and closely integrated societies, as urban societies were. In these areas, mostly “tribally structured” societies seem to have prevailed again in the third millennium after the so-called collapse of the Uruk system (Cooper 2006, pp. 54–63). This was the basic traditional structure of the Euphrates communities, which had never become full-fledged state and urban societies (see also the debate in Porter 2012).

Urbanization

While centralized political structures are documented in several areas in the north, an actual urbanization phenomenon significantly occurred only in the Khabour region and in central-eastern Jezira. The largest fourth millennium site in the Middle Euphrates valley was Habuba Kabira, which was almost certainly a colonial settlement founded by southern Uruk-related groups (Strommenger 1980; Strommenger et al. 2014). Despite having an urban layout with streets and quarters, a separate temple area, and a very large amount of administrative materials, Habuba did not exceed an area of 18–19 ha. The other known and investigated fourth millennium sites, whether colonial or otherwise, were always much smaller, and the territory as a whole in no way appears to have been urbanized before the mid-third millennium BC (Algaze et al. 1994).

Conversely, large sites developed in the Khabour region, above all Tell Brak, which appears to have reached more than 40 ha as early as LC2 (4200–3900 BC), when monumental buildings in the northern excavation area (TW) have been documented; it must have exceeded 130 ha by LC3–4 (3800–3400 BC), when we have evidence of the first construction of the large Eye Temple in the site’s southern zone (Emberling and McDonald 2003; Matthews 2003; McMahon and Oates 2007; Oates and Oates 1993, 1997; Oates 2002; Oates et al. 2007; Ur 2014b). The Khabour plain was irrigated naturally by numerous watercourses and had sufficient rainfall for successful rainfed agriculture. But the archaeobotanical data at Tell Brak suggest that in the urbanization phases some forms of irrigation, or simply of water management, also must have been practiced and that the farmed areas must have expanded to include most arid lands, as suggested by the substantial increase in barley, which is more adaptable to less favorable and more arid conditions (Charles et al. 2010). This kind of response to the need for greater volumes of agricultural products, most likely linked to the urban dimension of centers such as Tell Brak, was made possible by the large extension of the central Jezirah plains and hilly lands, which could have been farmed even in arid zones with some technical devices. There were certainly no such vast areas of potentially arable land available in the Middle/Upper Euphrates valleys.

Relations must have been intense with the pastoralists moving around the mountains surrounding the Mesopotamian plains, and also in Jezirah, as Wilkinson et al. (2014, p. 45) have emphasized when speaking about the “pastoral and wealth-based economy” as one of the sectors of the economic strategies of the early states in the Fertile Crescent (see also Porter 2012). But the presence of powerful centralized structures and urban systems must have created a centrally regulated and governed economic integration, which probably also entailed the imposition of political control over the pastoralist groups. In nonurbanized and not fully state-governed areas, conversely, the presumable greater autonomy enjoyed by the pastoralist and rural groups may well have given rise to more dialectical and dynamic interactions that at the same time created more changeable relations potentially leading to instability.

Although the urbanized areas of Jezirah were similar to those in Southern Mesopotamia, and even though we have to be cautious because of the different degrees of depth and details of the information on the southern alluvium compared with the thoroughly investigated territories in Upper Mesopotamia, the urban growth dynamics in these northern areas seem to have followed different pathways than those in the south. According to the detailed surveys of Tell Brak and its environs and the Tell Hamoukar area (Al Quntar et al. 2011; Ur 2010, 2014b; Ur et al. 2011; Wilkinson 2000; Wilkinson et al. 2014), the population of both areas (though differing in size) grew and gathered progressively around the main site from the fifth and throughout the fourth millennia BC. This has been studied and documented in great detail at Tell Brak, where small satellite sites were scattered around the main mound over a radius of at least 1 km. These sites were quite distant from each other in LC2, and little by little they drew ever more closely together around the main center, whose dimensions at the same time expanded exponentially in LC 3 and 4, creating a sort of integrated settlement system with the assumed decentralization of certain activities and functions in some of these minor satellite sites (McMahon and Stone 2013). The growth of nucleated urban centers surrounded by arable land and without any settlements in the immediate vicinity—a phenomenon already visible around Uruk from the outset, in the Late Chalcolithic (Adams 1981; Adams and Nissen 1972)—is conversely attested in the north in the Early Bronze Age (Wilkinson et al. 2014, p. 48).

In Upper Mesopotamia, urban nuclearization was therefore a gradual and rather lengthy process that included a progressive increase in population density and aggregation of sites around the emerging political–administrative and possibly religious centers. This led to the establishment of wide, densely occupied areas surrounding the main nuclear centers, where specialization and the integration of activities and functions not only took place initially through their direct concentration in the main site, leading to its expansion, but probably also through the establishment of a network of relationships between the small satellite sites and the larger center, where the central political functions were concentrated, as indicated by monumental public buildings and substantial ceremonial, administrative, and redistribution areas (Emberling and McDonald 2003; McMahon and Oates 2007; Reichel 2002). At Tell Brak, the main center also expanded gradually until it took on vast proportions around the mid-fourth millennium (over 100 ha), almost to the point of joining the small surrounding sites (Ur 2014b, pp. 52–56, figs. 3.2–3.3). This increased density came about at the expense of most of the cropped lands around the sites and probably spelled the end of the self-sufficiency of these small settlements, creating what was a full-fledged urban system of interacting parts, albeit in what were still relatively low-density peripheries. Developments of this kind must have been made possible only by a considerable rise in agricultural surpluses, perhaps achieved by extending cultivation to less favorable and more remote lands (Charles et al. 2010).

Political and Economic Centralization

Even though urbanization in the north took place only in the Khabour area and its environs, where there were favorable conditions, the centralized system with a powerful administrative organization and ideological/religious backing became established throughout the northern regions, though to different levels of development. One only has to think of the huge development of the administrative and religious public area on such a small site as Tepe Gawra (levels IX-VIII) already at the beginning of the fourth millennium (Butterlin 2009; Rothman 2002). Administrative operations were greatly intensified and became increasingly more complex in the course of the fourth millennium, as attested by the sophisticated administrative materials found at Tell Brak and Hamoukar (Pittman 2003; Reichel 2002), as well as in the Middle Euphrates sites, both in the colonies (Habuba Kabira and Jebel Aruda) (Strommenger et al. 2014; Van Driel and Van Driel-Murray 1983) and in small local sites (Hacinebi B1) (Stein et al. 1996). These activities were mainly concentrated in public and elite areas, which also exhibit an increasing monumentality (see, for example, the monumental buildings in the TW 20-18 levels and the Eye Temple at Tell Brak, as well as the public buildings at Tepe Gawra X-VIII), and were associated with the massive presence of mass-produced bowls. All of these elements reveal the growth of central institutions that were able to largely control production and labor as early as the first half of the fourth millennium, between LC2 and LC3, in parallel with what was happening in Lower Mesopotamia. Here again, the central political strategies seem to have been concentrated principally around the staple economy.

North and South: A Comparison

Social Structures

There must have been important differences between the basic social structures of the northern and the southern communities, although with the data available we can only advance cautious hypotheses. One important initial consideration is that the structure of the Halaf societies, from which the Late Chalcolithic communities in the north originated, was essentially egalitarian, and this must have established the original difference between these and the Southern Mesopotamian communities of the Samarra-Ubaid cultures, which seem to have already displayed forms of internal social differentiation and the emergence of high-status persons (“horizontal” vs. “vertical egalitarian” societies) (Frangipane 2007a). Looking at the Late Chalcolithic period, we can detect signs of a lower degree of stratification in the northern communities than in the Lower Mesopotamian societies, judging from the size of the houses (and presumably of the households) and their lesser degree of internal differentiation inside the settlements, where these have been sufficiently excavated. The dimensions of the tripartite houses at Tell Brak (TW level 16) and Hamoukar in Late Chalcolithic 3–5, as well as the Tepe Gawra levels XI-X houses in LC 1–2, measured between 30 and 60 m2 (Rothman 2002; Tobler 1950). Although we have no direct comparisons with southern houses in the Late Chalcolithic, based on the colonial settlements of Habuba Kabira and Jebel Aruda, the main tripartite core of those large houses alone occupied between 120 and 170 m2 (Strommenger 1980; Van Driel and Van Driel-Murray 1983), which was almost twice the size of houses in the local northern sites. An interesting comparison can be drawn with the earliest southern houses at Tell Oueili, in the Ubaid phases, which reflect the households of the southern communities in their formation stages and which appear to have been decidedly larger, reaching almost 300 m2 (Fig. 2a).

Finally, for the internal organization of settlements, we have data from the colonial site of Jebel Aruda, where one sector in the settlement, which was the main seat of administrative activities, was also the area with the largest and most standardized houses; unfortunately, there is almost no information from other Late Chalcolithic sites in Northern Mesopotamia, due to limited extensive excavations.

Ideology

This possible different kind of social composition was accompanied by another feature that, in my opinion, distinguished the urban societies in the Khabour from those of the Southern Mesopotamian alluvial plain: the different ideology of power, as it emerged in the ways in which it was visually represented. At Uruk, the personage of the ruler, the so-called King-Priest, was regularly represented in various types of art with clear identifying features that distinguish him from other human figures: the dress, the beard, and a band around the head. This is how the ruler was depicted in statuary and in seal iconography, where he is shown in scenes on cylinder seals performing the main functions connected with his role, focusing on ritual or ritualized acts (receiving offerings near the temple) and the ostentatious exercise of authority and force (Fig. 3c, d) (Boehmer 1999; Brandes 1979). The prevalent use of cylinder seals in Southern Mesopotamian must have been largely due to the need for an appropriate support to recount the essential features of the ideology of power in complex settings. The ruler’s function also was emphasized in more complex images, such as those depicted in bas-relief on the famous Uruk alabaster vase, in which the sovereign—which is largely missing and has been hypothetically reconstructed—is related in ritual act with the figure of the divinity, probably Inanna (Schmandt Besserat 2007, pp. 42–46). The rest of the scene, in the lower levels, shows the social and universal hierarchical order according to what must have been the dominant ideology: processions of persons bearing offerings and, underneath, rows of animals (caprines) and plants (cereals and palms?) that together with water (canals?) constituted the staple products of the Mesopotamian population and must have been the main area of interest in the economic strategies of the ruling class.

Conversely, in the Upper Mesopotamian glyptic, which was characterized by specific stylistic features and the prevalence of stamp seals that formed part of an ancient tradition dating back to the Neolithic, the seals mainly depicted animals. That indicates, in my opinion, a different ideological function of the imagery on seals, which was not intended mainly to represent and recount the life of the emerging central institutions and the key personages (ruler, bureaucrats, offerings, prisoners). The most significant scene that can be linked to the symbolic image of power is a lion hunt, which, in addition to being a common motif in the southern glyptics, was found repeatedly in the Tell Brak area (Tell Majnuna), showing the human figure bearing a spear fighting the animal (McMahon 2009) (Fig. 4b). This figure does not have any particular iconographic attributes distinguishing it from any other human representations, which are generally not frequently found. On other seals, the lion is depicted captured in a net. The dominant element therefore seems to have been not so much the ruler with all his attributes, prerogatives, and functions as in the south (Fig. 4a), but rather the representation of a more generic figure—perhaps associated with the image of leader—expressing strength and power in the act of dominating an animal, which was obviously itself the symbol of the power and might of nature. The lion is frequently represented in Mesopotamian glyptics, both alone and in association with other animals, and lion hunting must have had an important symbolic meaning in these contexts. This also may have had its roots in more ancient cultural traditions in the north, as far back as the Halaf period, when a hunting scene with a lion (or some large animal) also was depicted on the painted pottery from Arpachiyah, in Eastern Jezira (Hijara 1980, fig. 10; McMahon 2009).

Urbanization

We might reasonably say that the processes leading to the rise of state and urban political entities in Northern and Southern Mesopotamia must have followed different trajectories, mainly because of the different roles played by the urban phenomenon. In the north, early state institutions were formed even in the absence of urban sites, and urbanization seems to have been a gradual result of the formation of centralized institutions only in those areas where agricultural productivity made the growth of urban centers possible. Conversely, in the south, urbanization and state formation seem to have been closely linked from the beginning as two aspects of the same development, aimed at rationalizing the production and circulation of resources in a complicated but potentially highly productive agricultural environment, and in a potentially stratified and internally competitive society.

A significant difference between Northern and Southern Mesopotamian urbanization, besides the uneven spread of the urban phenomenon in the north, also must be related to the dynamics of the formation and development of cities there, which, where the phenomenon did take place, seem to have differed from the process of urban growth in the south. The gradual aggregation of small settlements or population groups in the political centers of Jezirah may indicate a different overall configuration and social composition of cities in the north and the south. An urban society like Brak may have been founded as the result of an increasing amalgamation of different groups and population components under a new and powerful political and economic authority. This process differs from what we presume must have been the case in the south, where the growth and concentration of homogeneous communities into large settlements was based from the outset on genealogical groups with strong kinship ties that were hierarchically organized and underpinned by a solid ideological apparatus. While assumptions of this kind can be supported only by new, extensive, and specifically targeted investigations at sites such as Tell Brak (sadly impossible at the present time), there are some tenuous clues to back up this interpretation. First, the public areas lay on the outskirts of the mound (the Eye Temple to the south and the imposing buildings in TW 18–20 to the north), perhaps designed to serve different sectors and people, also from neighboring areas, in contrast to the very large unitary monumental zones built in the heart of the city at Uruk-Warka. Another clue that political authority was probably less socially rooted in the Upper Mesopotamian centers is the absence of any representation and expression of power in the form of codified images. This suggests that there may have been a different ideological basis and legitimation of the role and the figure of the ruler, whose ascendants and social position must have been far less important than its real political and coordinating functions.

A different example of a large composite city made up of different sectors and groups (even ethnic groups) is the city of Teotihuacan in central Mexico, where the governor was not viewed and represented as the highest-ranking personage on the genealogical scale, but in terms of his functions in a complex context of interactions between different groups and quarters (Feinman and Nicholas 2011, pp. 137–138; Manzanilla 2012). Despite the undisputed role of temples and ritual practices in the north as well, a society of this kind was fundamentally more secular.

Emergence and Collapse of an Early State Center in the Upper Euphrates Valley: The Precocious Development of a Palatial System at Arslantepe, Malatya

The investigations we have been carrying out for decades at Arslantepe—a stratified mound, standing over 30 m high in the broad Malatya plain, close to the west bank of the Upper Euphrates in eastern Turkey (Fig. 1)—have enabled us to reconstruct a millennia-long history of the site and the region, dating back at least to the fifth millennium BC until the destruction of the Neo-Hittite citadel by the Assyrian king Sargon II in 712 BC. Later Roman and medieval occupations, smaller and of shorter duration, ended the sequence. By thoroughly analyzing the features of the successive building levels, brought to light over wide areas, and a detailed multidisciplinary study of the plentiful in situ materials, we have been able to reconstruct phenomena and processes of remarkable historical and anthropological significance, most of all the formation and subsequent collapse of a very ancient and peculiar form of early state organization in the fourth millennium BC.

The earliest levels that have been extensively explored so far refer to the so-called Arslantepe period VII, covering a long period roughly from 3900 to 3400 BC, corresponding to Late Chalcolithic 3 and 4 in Mesopotamia (Table 1). Throughout this period, characterized by a marked continuity in its development apparently without any substantial changes, the settlement covered the whole mound and even occupied its outskirts that had previously been unoccupied, with a clear spatial distinction between a zone with residences of the elites and a temple/ceremonial area on the top of the ancient mound, and the area of common dwellings built along the slopes and down to the margins of the mound and beyond (Fig. 5a). But the built-up area never reached an “urban” dimension; while it was the largest mound in the region, it was never larger than 5 ha, making Arslantepe a small site in Mesopotamian terms.

The mound of Arslantepe-Malatya with the occupied areas in periods VII (a) and VIA (b): a: Gray zones indicate the areas where period VII remains have been brought to light; b: The area occupied by the palace complex and its presumable extension (question marks refer to hypothesized palace areas in unexcavated zones)

A radical and almost abrupt change occurred around 3400–3350 BC (period VIA), when the temples were abandoned and replaced by a huge unitary monumental complex including both public and residential areas, which may be rightly considered to have been the earliest example of a “palace” that has ever been discovered in the Near East. This enormous expansion of the public and elite area was accompanied by a shrinkage in the size of the settlement itself, transforming the site into a kind of political–administrative center in which the “government” and “official” buildings covered most of the southwestern sector of the mound (Fig. 5b) (Frangipane 2012a).

The Origins of the Process in Late Chalcolithic 3–4 (Period VII): Centralization and Redistribution in a Temple Environment

The first half of the fourth millennium at Arslantepe, like in most Mesopotamian sites, showed the development of elites who ran a system of relations with the population revolving around the ceremonial redistribution of food. Excavations have brought to light a sequence of imposing buildings on the highest part of the ancient mound, in which no evidence has been found of public, religious, or economic–administrative activities, suggesting that they were probably residences of high-rank families, perhaps with some functions as representatives of the community (Fig. 6). Red and black wall paintings and mud-brick columns covered with white plaster decorated the main room in one of the residences (“column building”) from an early period VII phase (LC3), which was later divided into several rooms, of which one was converted into a food storeroom (room A617). Other rooms in the building had an oven, benches, semisunken pithoi, and other items of domestic equipment. The buildings subsequently erected over this residence, though damaged by later constructions, seem to have had the same function.

Adjacent to this zone was a large temple/ceremonial area, consisting of two imposing, adjoining buildings (Temple C and Temple D) standing toward the western edge of the mound (Fig. 7c). The reason why the public area did not stand in the center of the settlement, as in Mesopotamian cities, was probably due to the intention to make the temples visible from the surrounding plain and by the population of the villages, rather than by the people living in the settlement itself.

The two temple buildings were very large and had a codified and tripartite floor plan, recognized with certainty in Temple C, which, though damaged, is quite preserved. The same plan also is assumable for Temple D, which is largely hidden below the subsequent construction of the period VIA Palace on it. Both buildings, together with three large long rooms probably used for craft activities belonged to the most recent phase of period VII. They were certainly contemporary in terms of their use, as is evidenced from finding clay sealings in both of them that bear the impressions of the same seals, thereby indicating that the same individuals with administrative responsibilities had operated in the two buildings. Both structures must therefore have formed an imposing “sacred area.”

The tripartite floor plan, with a large central room equipped with a platform podium, and the articulation of some of the walls in multi-recessed niches, are clearly reminiscent of Mesopotamian temple architecture. But the walls of the main hall in the two buildings were decorated with red and black paintings (in Temple C) (Fig. 7a, b) and with painted plastic geometric motifs (in Temple D), related to an Upper/Middle Euphrates cultural environment and a local tradition. The painted plastic decoration found collapsed on the floor in Temple D indeed appears to be somehow unique so far.

These buildings are the only ones at Arslantepe that were built with a tripartite layout, whereas the houses, unlike those in the Mesopotamian world, were never tripartite. According to the evidence gathered in the northeastern peripheral area of the site (Palmieri 1978), the Arslantepe houses were small, usually comprising two or three small or medium-sized rooms, following nonstandardized layouts.

The pottery from period VII also was totally different from the southern or “colonial” examples and can be distinguished from the Jezirah repertoire as well, rather it was more similar to a cultural environment typical of southeastern Anatolian regions to the west of the Euphrates, as far as the ‘Amuq plain (Braidwood and Braidwood 1960; D’Anna and Guarino 2012). The seal designs also were related to a northern, though wider, cultural tradition (sealings from period VII have very recently been brought to light and are still under study).

The use of the tripartite plan exclusively for sacred buildings, which were probably the public buildings par excellence in that period, may have represented a symbolic reference to a world that was well known to the inhabitants of Arslantepe, with which they were certainly in contact, but whose influence was not so radically present and involved in their lives to have been able to bring about any change in their basic social structure. Reference to the Mesopotamian model in the ritual and ideological sphere linked to the authority probably suggests some prior influence, perhaps manifested in the Ubaid period, which may have led to emulation and hybridization phenomena mainly restricted to the elite and to their public activities, further legitimizing their status and role.

The economic and political strategies of the Arslantepe leaders, who governed the community by exercising their prerogatives of authority and prestige precisely in these sacred buildings, appear to have been very closely correlated with the Mesopotamian model. In these buildings, in addition to presumably managing ritual and ceremonies, the leaders would have performed political/economic functions by managing the circulation of foodstuffs with the distribution of meals in ceremonial events and “feasts” (Dietler and Hayden 2001; Helwing 2003; Pollock 2003). The Arslantepe temples have yielded thousands of mass-produced bowls, made with a different manufacture technique from the typical Mesopotamian beveled rim bowls (by using the slow wheel and scraping the base), but on an equally mass-produced basis (Guarino 2008), together with several hundred clay sealings that bear the impressions of numerous seals, almost all stamp seals (Fig. 8). Since Temple C has been completely excavated, the positioning of the materials found there has made it possible to reconstruct the function of the rooms and the ways in which the activities were performed. In the central room, the bowls were found untidily scattered on the floor south of the wide platform/podium, left there after use; many hundreds of bowls were conversely found in the two eastern side rooms standing upside down and partly piled up, both on the floor and in the collapse layers (Fig. 8a, b), showing that the bowls must have been stored in these rooms to be ready for use (D’Anna and Guarino 2010; Frangipane 2012a).

All the clay sealings in Temple C were concentrated in one part of one of the side rooms (Fig. 7b) and had perhaps fallen from a shelf or a collapsed upper story, where they must have been temporarily kept after removal from the containers. In Temple D, conversely, a large number of sealings had been discarded in a series of dumps, which also contained hundreds of bowls, in what must have been originally a stairwell (Figs. 7b and 8c–d). This material is still being studied, but at first sight it was immediately clear that sealings were frequently found bearing the impressions of the same seals in the same dump layers, as if they had been grouped together by type of operation, or by the official concerned, before being discarded. Our reconstruction of the way the administrative system at Arslantepe operated in the later period of the palace, based on a thorough analysis of the sealings, their positioning in the layers, and their mutual associations (Frangipane 2007c), makes this discovery extremely important and suggests that this efficient and sophisticated system for controlling and recording transactions before writing existed as early as this prepalatial phase.