Abstract

Considered one of the world’s earliest examples of a pristine state, the ancient Egyptian state arose by ca. 3000 BC. State formation in Egypt became a focus of much research in the 1970s and 1980s, as investigations of the Predynastic period in Egypt, when complex society arose there, began to uncover new evidence of the indigenous roots of this phenomenon. More recently, archaeological investigations in the Delta as well as continued work in southern Egypt have provided new evidence for the changes that took place in the fourth millennium BC. But the specific events and processes involved in this major sociopolitical and economic transformation and the resultant state still remain incompletely understood. To better understand the problem in Egypt, this study looks at the contrasting polities in fourth millennium BC Egypt and Nubia from the perspective of the political economy and the strategies to power proposed by the dual-processual theory, which also helps elucidate processes of state formation and the type of early state that developed there. The territorial expansionist model helps explain where and when this state first emerged.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In Egypt, the early state emerged by ca. 3000 BC, and state formation has been the focus of much archaeological scholarship there since the 1970s (e.g., Hoffman 1979). As more archaeological evidence has accumulated about Predynastic cultures in Egypt, which date to the fourth millennium BC when sociopolitical complexity evolved and an early state emerged, more theories about this phenomenon, as well as critiques of earlier theories, have developed based on increasing information (e.g., Anđelković 2004, 2011; Endesfelder 2011; Fattovich 2006, 2013; Jiménez Serrano 2008; Köhler 2010, 2011; Wenke 2009).

State formation in Egypt is a topic that I first researched and wrote about in the late 1980s and early 1990s, following my Ph.D. dissertation, An Analysis of the Predynastic Cemeteries of Naqada and Armant in Terms of Social Differentiation: The Origin of the State in Predynastic Egypt (Bard 1987). After working on archaeological problems in other parts of Egypt and Africa, I return here—25 years later—to my earlier investigations on state formation in Egypt because of advances in theory and the accumulation of more recent archaeological evidence related to state formation in Egypt. Much of the more recently excavated material was the focus of an exhibition at the Oriental Institute Museum, University of Chicago, and has been published in the companion volume, Before the Pyramids: The Origins of Egyptian Civilization (Teeter 2011a). The book Deep History: The Architecture of Past and Present (Shryock and Smail 2011) also was the inspiration for my looking at the problem of state formation in Egypt and the development of the early state from a longer range perspective, i.e., how the processes of state formation transformed into institutions of the pharaonic state. Twenty-five years of teaching a graduate seminar on the archaeology of complex society and comparative early civilizations at Boston University also have helped me rethink the rise of the early state in Egypt from a broader comparative perspective.

The ancient Egyptian state is one of the world’s earliest examples of a (primary/first generation) state, which had formed by the late fourth millennium BC. I focus on a comparative analysis of the political economies of complex societies with quite different power bases that arose in Upper and Lower Egypt and Lower Nubia in the fourth millennium BC, culminating in the emergence of an early state, and explanations for this phenomenon. From a long-term perspective, some of the successful strategies in the political economy of Predynastic polities in Upper Egypt can be seen to have evolved with greater elaboration as the early state developed in the third millennium BC.

Rank Society and the Rise of the Early State

The early state in Egypt evolved from less complex forms of sociopolitical organization that probably eventually competed with each other. What preceded the early state has frequently been termed the “chiefdom,” but this term has often been misused in the literature on social complexity. According to Marcus (2008, p. 258), “chiefdom” refers to a territorial unit—and not a type of society. Thus, “chiefdom” is not the best term to use for the unquestionably inegalitarian rank society that emerged in parts of Egypt in the fourth millennium BC and elsewhere, although many scholars have used it (and continue to use it) to refer to rank society with a number of general cross-cultural characteristics.

In 1974, Renfrew published an important article (first presented at a colloquium of the American Schools of Oriental Research), “Beyond a subsistence economy: The evolution of social organization in prehistoric Europe.” In this article, Renfrew (1974) lists 20 features frequently seen in chiefdoms in prehistoric Europe (p. 53) and then discusses two different kinds of chiefdoms (pp. 74–82)—“group oriented” and “individualizing”—as well as specific archaeological evidence in Europe for these two different types of chiefdoms. Renfrew refers to a number of chiefdoms described by Sahlins (1958) in Social Stratification in Polynesia as group-oriented, with relatively low levels of technology and periodic redistribution of foodstuffs and gifts, such as for feasts or major public gatherings (Renfrew 1974, p. 74). Public works, such as temples, were created through “group participation towards a single, communal end” (Renfrew 1974, p. 78). Individualizing chiefdoms, however, have evidence that distinguishes the “individual leader,” “either by the number, richness, and symbolic value of his possessions, or by the scale and prominence of his residence,” which frequently show a high level of technology, especially metallurgy (in the Old World) (Renfrew 1974, p. 79).

More than 20 years later, Blanton, Feinman, Kowalewski, and Peregrine published their dual-processual theory—for the evolution of civilization in Mesoamerica (Blanton et al. 1996, p. 1). The dual-processual theory is important because it is “a preliminary behavioral theory grounded in the political economy,” and does not simply offer a contrasting list of traits for two different types of rank societies/chiefdoms as Renfrew has done. Blanton et al. (1996, p. 1) argue that this theory “elucidates the interactions and contradictions of two main patterns of political action, one exclusionary and individual-centered and the other more group-oriented.” For them, political economy is “an analytical approach that elucidates the interactions of types and sources of power” (Blanton et al. 1996, p. 3). As Stiner et al. (2011, p. 259) have written in their chapter in Deep History, “To understand the emergence of chiefdoms is to understand the invention of political economy: that is the mobilization and central channeling of resources to develop sources of power.” It is this concept of the political economy that I use here to discuss the development of chiefdoms in Egypt—and their sources of power—and eventually the rise of an early state.

The dual-processual theory focuses on two types of strategies in the political economy of the complex societies: “network strategy” and “corporate strategy.” Network strategy is one in which “preeminence is an outcome of the development and maintenance of individual-centered exchange relations established primarily outside one’s local group,” especially where a prestige-goods system “manipulating the production, exchange, and consumption of valuable goods is central to strategies aimed at gaining control over politically potent exchange relations” (Blanton et al. 1996, pp. 4–5). In contrast, corporate strategy operates in Renfrew’s group-oriented chiefdom, without an elaborate prestige-goods system (Blanton et al. 1996, p. 5).

The corporate and exclusionary modes or strategies are seen as two ends of organizational strategies that can widely vary, in both spatial scale and hierarchical complexity (Feinman 2010, p. 255). But Feinman (2000, pp. 220–221) cautions that the corporate/network strategy is not simply a new typology. Its goal is to elucidate a behavioral theory rooted in political economy (Feinman 2010, p. 279).

The transition from small agrarian societies to larger political entities was a process in which increasingly more people cooperated, either voluntarily or otherwise (Stanish 2013, p. 85). Human groups or networks of cooperation vary in the way they are interconnected (Feinman 2013, p. 47), and a theory of collective action, for the role of cooperation in social evolution, has major explanatory value. Both corporate and exclusionary groups were interconnected by mechanisms that promoted cooperation (Carballo 2013, pp. 11–13). Domination and collectivity are expressed to varying degrees in all complex societies, and variation will occur: a major goal of collective action theory is to explain such variation through time and space (Blanton and Fargher 2008, p. 15). Thus the comparative degree of collectivity can be compared in premodern states.

It was certainly not inevitable that prehistoric rank societies/chiefdoms would evolve into the earliest states, and Carneiro (1981), Spencer (1998), and others have discussed the cyclical nature of chiefdoms (for the cyclical nature of early states, see Marcus 1992, 1998). Chiefdoms are prone to repeated cycles of political growth, with an increase in power and resources controlled by the chief, followed by a period of decline (Spencer 2010, p. 7120).

Spencer (2010) has proposed in a territorial-expansion model how such cycles of chiefly growth and decline were avoided, and how primary states first evolved in antiquity, in Mesoamerica, Peru, Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, and China. These cases also offer an opportunity to investigate the conditions and processes responsible for the pristine transformation of a society with no experience of state institutions into a functioning state (Spencer and Redmond 2004, p. 174). To avoid a decline resulting from chiefly political growth reaching it limits, a new strategy for resource mobilization had to be devised (Spencer 2010, p. 7120), and “the emergence of each primary state was concurrent with the expansion of its political-economic control to areas that lay well beyond the home region” (Spencer 2010, p. 7125).

How first-generation states are different from rank societies/chiefdoms has been proposed by Wright (1977). The chiefdom is a society with central decision making, but it is not internally specialized (Wright 1977, p. 381). The state, however, is something different, with a centralized decision-making process that is both externally specialized in terms of local regulation and internally specialized so that its central process can be divided into separate activities performed in different places at different times (Wright 1977, p. 383). Thus the state is a society with a centralized and also internally specialized administrative organization, whereas the chiefdom is a society with a centralized but not internally specialized administration (Spencer and Redmond 2004, p. 173).

In the case of early Egypt, rank societies arose in the fourth millennium BC, and a study of their political economies and variation of collective action may be useful in elucidating the development of power—or the lack of such development—in these societies, as well as how some successful strategies in the political economy evolved into those of the early state. As the primary state emerged in late fourth millennium BC Egypt, evidence at this time for centralization and specialized administrative organization may point to where and when this occurred.

Predynastic Cultures in Egypt

It is not my intent here to look at how rank social groupings (sometimes called “chiefdoms”) evolved from the probably more egalitarian early farming villages in the Egyptian Nile Valley. The evidence I discuss here focuses on later stages of sociopolitical evolution of complex societies and the emergence of the early territorial state.

I discuss two types of strategies in the political economy of the complex societies that developed in Egypt in the fourth millennium BC: “network strategy” and “corporate strategy.” For how these two different strategies to complexity apply to Predynastic Egypt in the fourth millennium BC, we need to turn to the archaeological evidence. Excavations of a number of Predynastic sites began long before the advent of radiocarbon dating, and a relative sequence for the Naqada culture was first published in 1901 by Petrie, in which he placed artifacts excavated in burials in three sequential groups (Amratian, Gerzean, and Semainian). Subsequent revisions to Petrie’s sequence dating system, beginning with that of Kaiser (1956, 1957), now divide the sequence into Naqada I, II, and III periods, which span the fourth millennium BC, with subdivisions based on ceramic seriation (see Hendrickx 2006). Both relative and absolute dates are used in this study.

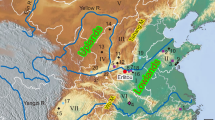

Farming villages (with some external exchange) emerged in both northern and southern Egypt before the fourth millennium BC (e.g., the Badarian culture in Middle/Upper Egypt, see Brunton and Caton Thompson 1928; Merimde Beni-Salama in Lower Egypt, see Baumgartel 1965). By the mid-fourth millennium BC, and earlier in some places (e.g., at Hierakonpolis, see Friedman 2011), elites of rank social groups were practicing a network strategy in emerging centers of the Naqada culture in Upper Egypt. Legitimation of socioeconomic inequalities was symbolized in the mortuary cult in cemeteries in Upper Egypt (especially in cemeteries at Hierakonpolis, Naqada, and Abydos) (Fig. 1). At sites of the Lower Egyptian culture, however, such mortuary—or other forms—of symbolism of marked differentiation are not found.

The Predynastic Lower Egyptian Culture

Sites of Lower Egyptian culture (formerly called the Buto-Maadi culture) are found in northern Egypt (with some local variation) and are distinctly different in their material remains from the Naqada culture of Upper Egypt. While long-distance trade with the southern Levant was conducted through Lower Egyptian centers, there is no evidence of sociopolitical inequality or chiefdoms with a political economy practicing a network strategy in a prestige-goods system, nor is there evidence to suggest that these Lower Egyptian centers were polities that were structured as chiefdoms. The Maadi settlement, located to the south of modern Cairo, consisted of small houses with no evidence of a large structure (Rizkana and Seeher 1989) and two cemeteries with individual graves (Rizkana and Seeher 1990). More than half of the Lower Egyptian culture burials from these two cemeteries as well as those from Heliopolis were without grave goods; grave goods in other graves consisted of one to four pots (Rizkana and Seeher 1990, p. 98) and certainly no prestige-type goods. Thus at Maadi there is no evidence of an “individualizing” rank society, either in the form of large houses or elaborate burials containing prestige goods.

What is distinct about the Maadi settlement, however, are the four semisubterranean houses found in the eastern sector of the site (Rizkana and Seeher 1989, pp. 49–56). Two more subterranean houses were subsequently excavated in the western sector of the site (Badawi 2003; Hartung 2003, 2004; Hartung et al. 2003). These subterranean houses are unknown elsewhere in Egypt, but they are similar to the structures in Chalcolithic settlements in the Negev region (Gilead 1987; Levy 1986, pp. 88–89; Perrot 1955, 1984). A number of complete vessels and numerous fragments of imported Ware V/Palestinian Ware (globular jars with ledge- or lug-handles) were found in the Maadi settlement (Rizkana and Seeher 1987, pp. 31–32). Other imports at Maadi from the southern Levant (Early Bronze IA) include tabular flint scrapers and blades (Rizkana and Seeher 1985). There also is evidence of small copper artifacts and imported copper, including three ingots and ore, which may have been used for pigments and not copper production (Rizkana and Seeher 1989, pp. 17–18). Recent research indicates that the Maadi copper originated at Timna in the southern Levant and may have been cast into ingots at the site of Tell Hujayrat al-Ghuzlan, near modern Aqaba (Klimscha et al. 2014, p. 169).

These imports may have been controlled not by local Maadi elites, for which there is no evidence of their existence, but by outsiders from the southern Levant/Beersheva Valley who were embedded in the community and used the subterranean houses (Hartung 2014, p. 111; Levy 1992, p. 353; Rizkana and Seeher 1989, p. 80). For such exchange Harrison (1993) has posited a “middleman” intermediary, after Renfrew’s (1975) “freelance middleman trading” model.

Occupation at Maadi continued until ca. 3400 BC (by the end of Naqada IIC), based on the sequence for the Predynastic Naqada culture in Upper Egypt) (Rizkana and Seeher 1987, p. 78). This may very well have been the result of the northward expansion of the Naqada culture.

Not until the later cemetery of Minshat Abu Omar, in the northeastern Delta, is there evidence of more burial differentiation in northern Egypt. These graves range in date from late Predynastic (“spät prädynastisch,” MAO I), to Dynasty 0 (MAO III), to the First Dynasty (MAO IV) (Kroeper and Wildung 1994, 2000). MAO IV burials exhibit the most complexity; some contain high numbers of pots as well as prestige goods, such as stone vessels, but by this time the Egyptian Dynastic state was in control in both Lower and Upper Egypt.

Another site in northern Egypt, Tell el-Farkha in the eastern Nile Delta, is also lacking in evidence for elites until later in its Predynastic sequence. Built over an earlier complex of breweries (12 large vats) on the Western Kom at Tell el-Farkha was a monumental mud-brick structure (with walls at least 2 m thick) dating to ca. 3300–3200 BC (Ciałowicz 2012b, c), by which time Naqadans from the south “had gained the clear advantage over the local inhabitants” through either assimilation or acculturation, with no evidence of warfare or conquest (Ciałowicz 2011, pp. 55–56). This monumental building (the “Naqada residence”) consisted of numerous rooms arranged around a courtyard; imported pottery from the southern Levant, storage jars, and sealings provide evidence that it was used for trading activities (Ciałowicz 2011, pp. 56–57, 2012c, pp. 163–171). Slightly later in date than the Naqada residence, a 300-sq m tomb superstructure was built (ca. 3200–3100 BC) in the necropolis area on the Eastern Kom (Ciałowicz 2011, p. 62). This type of elite tomb is called a “mastaba” (a low rectangular structure, often with a niche or interior room for offerings, which covered the subterranean tomb), and the Tell el-Farkha mastaba is the largest known mortuary structure from this period in Egypt.

The Naqada residence on the Western Kom at Tell el-Farkha was eventually destroyed by fire (of unknown causes) and then covered by a layer of Nile silt. Above this another huge mud-brick complex was built, an “administrative-cultic” center with two chapels/shrines containing votive deposits (Ciałowicz 2012c, pp. 171–180), dating to Dynasty 0 and the early First Dynasty (Ciałowicz 2011, p. 57).

Throughout the course of its Predynastic occupation, the political economy of Tell el-Farkha clearly changed. In its earlier occupation by peoples of Lower Egyptian culture, there is evidence of large-scale beer production and trade/exchange with the Near East and Upper Egypt (Ciałowicz 2011, p. 55). Ciałowicz (2012c, p. 163) has suggested that the mass production of beer was not only for local consumption but also was connected to the exchange of goods. The brewing facilities also may have been related to community feasting events, which suggests a degree of collective action of the community—and a corporate strategy in the political economy and a group-oriented polity.

Hartung (2014, p. 112) states that with the arrival of Naqada culture in the north in Naqada IIC/D times, as represented by the monumental building at Tell el-Farkha and also burials at Minshat Abu Omar, Upper Egyptian power was established there or at least there were “Naqada-linked” mayors or chiefs who organized and controlled the economic activities. Thus it was not until Tell el-Farkha was dominated by peoples of Naqadan/southern culture that evidence of an individualizing polity with a network strategy in the political economy appears in the form of monumental architecture (both mortuary and in settlements). As excavations and analyses at Tell el-Farkha are ongoing, it will be useful to study the archaeological data to better elucidate the changing political economy.

Political organization and power structures in the Naqada II period in Lower Egypt are unknown, which is also the case for Buto in the northern Delta, where there is evidence in Stratum Ia of “Canaanite immigrants” who produced their own household ceramics thrown on a turning device, a technology that was later abandoned (Faltings 2002, pp. 165–169). There is nothing to suggest, however, that the political economy, which mobilized resources for such exchanges, developed into elite/individual sources of power in these Lower Egyptian centers until the arrival of the Naqada culture there in later Predynastic times.

The Predynastic Naqada Culture of Upper Egypt

For earlier evidence in Egypt of what can probably be considered as individualizing chiefdoms/rank societies practicing a network strategy in the political economy, we must turn to the Naqada culture of Upper Egypt and the three largest sites there (from north to south): Abydos, Naqada, and Hierakonpolis (see Fig. 1). Of these three sites, Hierakonpolis (ancient Nekhen) has the best preserved archaeological evidence, from both settlements and cemeteries.

Settlement studies at Hierakonpolis have demonstrated that through time (the fourth millennium BC), as summer rains decreased in the low desert and Nile inundations declined, settlement areas shifted closer to the Nile Valley, with a nucleated town developing at the edge and within the floodplain, and outlying cemeteries (Hoffman et al. 1986). While there is no settlement evidence of elite residences, evidence in the elite cemetery at HK6, to the southwest of the HK11 wadi settlement, suggests the emergence of rulers who “exhibited their power and status in the outstanding size and wealth of their burials” in the early Naqada II period, ca. 3650 BC (Friedman 2011, pp. 36, 38). Grave goods in the Tomb 16 burial pit in this cemetery included over 115 pots, two ceramic funerary masks, and other artifacts in exotic materials (Friedman 2011, p. 39). Subsidiary graves associated with this burial and connected by wooden walls were for 36 individuals, including young men, women, and children. Burials of animals, both domesticated (cattle, dogs, cats, goats) and wild (an aurochs, hartebeest, elephant, hippopotamus, and three baboons), also were associated with Tomb 16 (Friedman 2011, pp. 39–40). Other elite tombs in HK6 include ones with “pillared halls” that are concentrated in the center of this cemetery and interpreted as early evidence of mortuary temples and the rituals associated with them (Friedman 2011, p. 41).

Hierakonpolis is also where the oldest and only known Predynastic elite tomb with wall paintings—Tomb 100, the “Decorated Tomb”—(and pottery of the Naqada II period) was excavated in the late 1890s (Quibell and Green 1902, pp. 20–21). Painted on one of the mud-brick lined walls to this tomb are images of six boats and motifs of hunting and human conflict.

There is also evidence at Hierakonpolis of Predynastic temple structures. Within the Predynastic town, at Locality HK29A, Hoffman (1987, pp. 48–67) excavated the remains of a Predynastic “temple,” which consisted of a large, walled oval courtyard, begun in early Naqada II times. Reinvestigation of HK29A by Friedman has revealed three phases of use, the last of which has pottery dating to the First Dynasty. Analysis of the refuse from HK29A (ceramic, botanical, and faunal remains) provides evidence of ritual and not domestic behavior related to feasting that took place there (Friedman 2009); large-scale production areas for beer and pottery (beer jars) also have been excavated in the northern part of the town along with silos in which the grain for making beer was stored. HK29A also was part of a much larger ceremonial complex that extended north to a palisade structure almost 50 m long at HK29B and a columned hall farther north at HK25 (Hikade 2011). Workshops for stone tools, vessels, and beads also were excavated in the ancient town (Hikade 2004). Possibly the large-scale beer production and temple suggest a degree of collective action in the Hierakonpolis polity, but with a hierarchical sociopolitical organization, as evidenced by the burials of high-status chiefs(?).

In her 2011 article, Friedman states that by ca. 3600 BC Hierakonpolis was more than a local center of power, although the extent of its territorial control, from southern Upper Egypt and into Nubia, is unknown. Friedman suggests that by the beginning of Naqada II times at Hierakonpolis there was a multitiered stratified society, with craft specialization and strong leaders able to marshal labor and exotic imported materials to express their authority. She concludes that “the idea of kingship in its dynastic form may well have originated at Hierakonpolis…” (Friedman 2011, p. 44).

With known temple structures dating to the Predynastic period at Hierakonpolis, it is not surprising that there is evidence from a temple, most likely dating to Dynasty 0, at the beginning of the Dynastic period when a unified kingdom had formed. In what Quibell termed the “Main Deposit” (Quibell and Green 1902, pp. 40–41) were carved, decorated maceheads of kings Scorpion and Narmer that had been ritually buried in this deposit when the temple to which they were royal donations had probably been dismantled to build another (later) temple. Also found in this area was the Narmer Palette, famously symbolic of Egyptian kingship (Fig. 2).

North of Hierakonpolis, Naqada was the first Predynastic site to be excavated, by Petrie in 1894–1895. Petrie excavated three Predynastic cemeteries there (Great New Race, B, T), as well as two settlements, “North Town” and “South Town.” In the northern part of South Town Petrie found the remains of a thick mud-brick wall that appeared to be “a fortification with divisions within it” (Petrie and Quibell 1896, p. 54). With nothing remaining of this structure when South Town was reinvestigated by American and Italian archaeologists in the 1970s and early 1980s, one can only guess at its original function, possibly a palace structure, though a temple also may be likely. The Italian archaeologists found clay sealings in South Town that had probably been used to secure doors where materials or craft goods (relating to trade and exchange?) may have been stored (Barocas et al. 1989, p. 301).

As at Hierakonpolis, at Naqada there is evidence of 69 very high-status burials in Cemetery T, a cemetery for only a small elite group that was set apart in space from the other Naqada cemeteries. Mostly dating to the Naqada II period, these graves were large and three had elaborate structures that were lined with mud bricks. The undisturbed grave T5 contained many artifacts such as carved stone vessels and jewelry made from exotic imported materials (Bard 1994a, pp. 272–273; Baumgartel 1970, p. 67). The Cemetery T burials are very different from those in other Naqada cemeteries, symbolizing a special status in the Naqadan society, and they have been considered the burial place of Predynastic chieftains (Case and Payne 1962, p. 15) or kings (Kemp 1973, p. 42).

Also at Naqada was the largest known Predynastic cemetery, Petrie’s “Great New Race” cemetery, with over 2,000 burials. Almost 1 km south of the Great New Race cemetery was Cemetery B, with 144 graves (Bard 1994b, p. 79). Not only are the Predynastic burials at Naqada greatly differentiated, but from Dynasty 0 there also were two “royal” tombs in another necropolis with tombs containing Early Dynastic grave goods (de Morgan 1897, p. 159). The excavator of these tombs found clay sealings of King Aha in the one well-preserved “royal” tomb (de Morgan 1897, pp. 164–168). The name of Aha’s mother, Neithhotep, also was found in this tomb, which had an elaborately niched mud-brick superstructure, as is found in the high-status, First Dynasty cemetery at North Saqqara (west of the newly founded capital of the kingdom at Memphis). Unquestionably, burials at Naqada became symbolic of socioeconomic and possibly political status, and the sumptuary grave goods in burials such as T5, which contained 42 pots and artifacts in gold foil, lapis lazuli (from eastern Afghanistan), carnelian, garnet, and glazed steatite (Baumgartel 1970, p. 67), represent long-distance exchange of exotic imported materials that may originally have been stored in facilities in South Town where door sealings have been found.

Predynastic sites in the Abydos region do not have well-preserved evidence until quite late, but at el-Mahasna, ca. 10 km to the north, recent excavations have revealed a post-structure (“Block 3”) with a mud-plastered floor on which 22 figurines of cattle and seven of seated women had been placed. This was a large ritual building of Naqada IC-IIAB date, and faunal offerings were associated with it (Anderson 2007).

Tombs excavated at Abydos by the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo, in Cemeteries U and B may be those of some of the rulers who preceded the First Dynasty. Excavations in Cemetery U revealed Naqada II and III graves and larger graves northwest and southeast of the earlier ones (Dreyer 1992b, pp. 294–295, fig. 1). Although robbed, one large tomb (U-j) in this cemetery, with radiocarbon dates of ca. 3200–3150 BC, still had much of its subterranean mud-brick structure, as well as wooden beams, matting, and mud bricks from its roof. The tomb pit was divided into 12 chambers, including a burial chamber with evidence of a wooden shrine and an ivory scepter. About 2,000 ceramic jars were excavated in this tomb, including over 500 vessels with residue of wine. Almost 200 small labels in Tomb U-j, originally attached to goods, were inscribed with the earliest known evidence of writing in Egypt (Dreyer 2011).

The burials of kings of Dynasty 0 as well as that of Aha, the first king of the First Dynasty, have been identified by Kaiser (1964, pp. 96–102) in the adjacent Cemetery B. In the First Dynasty, all of the kings (and one queen) were buried at Abydos in the Royal Cemetery, excavated by Petrie at the turn of the last century (Petrie 1900–1901; see Bestock 2011, pp. 137–142). The kings of the First Dynasty also constructed monumental “funerary palaces” that seem to have been intentionally disassembled after the king’s death (O’Connor 2009, p. 176).

Although many Predynastic burials at Upper Egyptian sites were robbed in antiquity, recorded grave goods in excavated burials, as well as some production sites, demonstrate increasing craft specialization through time (Takamiya 2004a, p. 1033). Regarding the evidence of carved stone vessels, Hendrickx (2011, p. 95) writes that by Naqada IIIC2–IIID times these artifacts “make up about 20 percent of funerary goods.” Grave goods in exotic imported materials also are seen, which by Naqada III times are found in very rich burials, such as Tomb U-j at Abydos and Tomb 11 in the elite HK6 cemetery at Hierakonpolis. Traded goods and materials can move across distances by different mechanisms, but the volumes of prestige goods in some late Naqada culture elite tombs, such as the hundreds of wine jars in Tomb U-j, represent a highly organized trade system operating in the political economy, with the ability to control and transport large volumes of goods and commodities.

Thus, by the mid-fourth millennium BC, elites in rank societies/chiefdoms were emerging at major sites such as Abydos, Naqada, and Hierakonpolis in Upper Egypt. The highest-status elite burials in these Naqada culture cemeteries are probably evidence of individualizing chiefdoms, to use Renfrew’s term. These societies were practicing a network strategy involved in expanding long-distance trade and exchange, with the political economy (trade, trade goods, trade networks, craftsmen) probably increasingly controlled by elites in whose burials these craft goods, as well as imported items, are found.

Control of craft production and the trade it involved also meant conversion of some of the agricultural surplus. The chief’s supporters were probably rewarded for their support by gifts of prestige goods, the products, or imports of this political economy. This was a type of prestige-goods economy (Takamiya 2004b, p. 61), and the acquisition of luxury goods would have been valuable for maintaining sociopolitical hierarchies, while extending clientage to others who desired such goods (Moorey 1987, pp. 42–43). The production, exchange, and consumption of these prestige goods, increasingly found in high-status Naqada culture burials, were obtained through a network strategy in the political economy of different emerging Naqada centers.

Elite burials in Upper Egypt also probably helped legitimate socioeconomic inequalities, which were symbolized in the mortuary cult, a belief system that became increasingly important to all members of the society, with leaders who could claim lineal descent from high-status ancestors with (hereditary political?) authority (Bard 1992, pp. 16–17). What developed in the Naqada culture was not an ideology of a corporate strategy, as Perry (2011, p. 1277) has suggested, but one with “ancestral ritual that legitimates control of society by a limited number of high-ranking individuals or households” (Blanton et al. 1996, p. 6). Fattovich (2006, pp. 637–638) suggests that manipulation of ideology was a crucial factor in legitimating the role and power of chiefs or “petty kings” in Upper Egypt in Naqada II times, with the emergence in the Naqada III period of a paramount/sacral king, who guaranteed the social and natural order. Supernatural explanations of the universe and humans’ place in it were probably inherent in this ideology, which legitimized power relations and at the same time provided explanations for the basic questions of human existence and humans’ role in the natural world. This ideology presented a “code of social order” (Earle 1997, p. 8) that legitimized social hierarchies.

A-Group Culture in Lower Nubia

The A-Group culture in Lower Nubia, south of Egypt (between the First and Second Cataracts), was contemporaneous with the Naqada culture of Upper Egypt. Although there is evidence of the A-Group in the First Cataract/Aswan region, where Gatto’s (2009, 2014) work demonstrates “cultural entanglement” of the two groups, this region remained part (of a southern variant) of the Naqada culture.

Unlike the agricultural economies of Predynastic cultures in Egypt, the A-Group economy was mainly based on herding (Gatto 2006, p. 71). There was limited agricultural potential to produce surplus in Lower Nubia, since the Nile floodplain narrows significantly there.

The A-Group is known mainly from its cemeteries, and Naqada culture craft goods, obtained through trade, were found in a number of A-Group burials. A-Group burials also contained craft goods manufactured there, but evidence of craft production in Lower Nubia (and control of this) is lacking. According to Gatto (2014, p. 115), the interaction sphere model helps in interpreting Naqada and A-Group relationships and the possible spread of an ideological system based on a shared set of beliefs and practices.

Economic factors were probably a major factor for the Naqada group to include Nubia in its sphere of interaction, and a super-regional Naqada identity definitely facilitated trade (Gatto 2014, p. 116). A-Group trade with the Naqada culture is attested at the special purpose site of Khor Daud, which consisted of almost 600 storage pits with much pottery, two-thirds of which was Egyptian (Naqada II), and no evidence of houses (Nordström 1972, p. 26).

Naqada Hard Orange Ware (HOW) also was an important trade good in Nubia, both the pottery itself and its contents, commodities such as beer, oil, cereals, and wine (Takamiya 2004b, pp. 36, 55, 60). This ware was made of Nile silt tempered with crushed calcium carbonate (Hamroush et al. 1992, p. 49), the latter of which occurs within the Naqada area where such geologic deposits are found, but not in Nubia. Takamiya’s study suggests large-scale distribution of HOW by (Naqadan) traders to A-Group sites, where this ware can be clearly identified in burials, from a distribution center at Aswan by the middle of Naqada II (Takamiya 2004b, p. 50). By the beginning of the Naqada III period, with the export of many large “wine jars,” there was direct exchange with the Second Cataract area, probably with trade “emissaries” and “colonial enclaves,” and a connection, either direct or indirect, with Lower Egypt (Takamiya 2004b, pp. 59–61). Thus the patterns of consumption of HOW suggest the expanding political economy of the Naqada culture, which included Lower Egypt and Nubia.

In the Terminal A-Group, dating from the Naqada III period to the early First Dynasty, some very high-status tombs are known from several A-Group cemeteries (see Williams 2011). At Sayala in Cemetery 137, two gold-handled maces (symbolic of a ruler?), as well as copper axes, ingots, and chisels, were found in Grave 1 (Firth 1927, pp. 206–207). At Qustul in Cemetery L, a number of large graves contained Egyptian imports, including two long rows of large Egyptian storage/“wine” jars in tomb 23 (Williams 1986, pl. 109). The incense burner from tomb 24 in this cemetery, of Naqada IIIA2 date, is carved with a scene of two river processions and motifs associated with Egyptian kingship: the White Crown of Upper Egypt and the serekh, the earliest format in which the king’s name was written, possibly the design of a palace gateway, surmounted by the Horus falcon (see Williams 1986, pp. 138–146, 2011, pp. 87–88). Twelve even larger tombs, with subordinate burials, sacrifices, and deposits, were found in Cemetery S adjacent to Cemetery L (Williams 2011, p. 87). According to Williams (2011, p. 88), “the different tiers of tombs by size and wealth show that there were social classes.” Although Hodder (1982) and others have demonstrated that there is no one-to-one correlation between burials and levels of social organization, the Qustul burials may be symbolic of increasingly differentiated statuses of some sort within the living society.

While Williams (1986, p. 163) has suggested that pharaonic rulers were buried in Cemetery L at Qustul, the existence of a kingdom/state there has been questioned (see Adams 1985). Although burials in this cemetery are certainly rich ones that contained prestige goods, it is more probable that these rulers (chiefs?) only had local power, as a result of providing Naqadan groups with exotic raw materials (probably from the south, as later in Dynastic times) in a trading system controlled mainly by Egyptians and not Nubians (Takamiya 2004b, pp. 58–59; Trigger 1976, pp. 42–43).

The emergence of high-status elites in Lower Nubia (and the provisioning of their tombs with such wealth) in a prestige–goods system was economically dependent on trade with Egypt. Rank societies, as evidenced by elaborately furnished tombs (of chiefs?), are found in Lower Nubia later than those in Upper Egypt (at Naqada Cemetery T and the Hierakonpolis HK6 cemetery), but this Nubian political economy was soon terminated in development by the penetration of the Egyptian military into Lower Nubia in the early First Dynasty, when the A-Group disappears archaeologically.

The Expanding Naqada Culture and State Formation

Although I have selectively discussed archaeological evidence for the Lower Egyptian culture, as well as for the Naqada culture of Upper Egypt, the evidence for the political economies that developed in Upper Egypt and Lower Egypt in the fourth millennium BC is distinctly different. Renfrew’s (1974) model helps explain these different polities, with individualizing chiefdoms in Upper Egypt and more group-oriented centers in Lower Egypt. Blanton, Feinman, Kowalewski, and Peregrine’s (1996) dual-processual theory of the political economy in these societies, practicing a network or corporate strategy, also helps explain two different types of political–economic organization in the absence of definite evidence for political roles. But how did an early state(s) evolve from these rank societies in Upper Egypt in the fourth millennium BC, and how did this polity differ from chiefdoms?

The reason for expansion of the Predynastic polities in Upper Egypt (and not Lower Egypt) may have been because the political economies of these polities became expansionary as they increasingly engaged in long-distance trade and exchange, both to the north and south.

In the far south of Egypt, Hierakonpolis was located near sources of elephant ivory, as well as exotic raw materials that flowed through Nubia, including gold found in mines east of the Nile there. Although Friedman (2011, p. 44; see above) states that the region it controlled ca. 3600 BC “probably spanned the southern part of Upper Egypt and into Nubia,” it is unlikely that Hierakonpolis’s political control extended into Lower Nubia, due to the rise of Terminal A-Group rank societies there, with increasing wealth of late A-Group elites based on trade with the Naqada culture. The A-Group expanded south to the Second Cataract region in Terminal A-Group times, but this was a cultural expansion, and it is unlikely that the evidence represents a territorial/dynastic state, as Williams (2011, p. 91) has suggested.

Sandwiched between the Abydos polity to the north and the Hierakonpolis polity to the south, the Naqada polity could only expand its control into desert regions to the west and especially to the east, where gold and valuable hard stones for prestige goods were obtained. But such desert regions were for resource exploitation and would not have increased the inhabited area of the Naqadan polity or the cultivated floodplain.

While there is good archaeological evidence at Hierakonpolis of the expanding political economy (specialized craft production, long-distance trade, and possibly increasing control of this economy by elites buried in HK6), an expanding political economy at Abydos can only be hypothesized. But inscriptions on Naqada IID pottery from three tombs in Cemetery U at Abydos may indicate the provenance of their contents and, according to Engel (2013, p. 24), are the earliest evidence for the existence of [bureaucratic] institutions.

The hypothetical expansion of the Abydos political economy through trade to the north, however, was unimpeded and possibly these regions came increasingly under the control of the Abydos polity. Although ancient settlements in Egypt have not been well preserved from any period, there is a lack of evidence of any large Predynastic centers/polities in Middle Egypt (see Kaiser 1957, pl. 26; Stevenson 2009, pp. 45–46), and, according to Moreno García (2014, pp. 236–237), Middle Egypt was a region that was “scarcely populated” during most of the following third millennium BC. Abydos’s expansion to the north may have occurred through different mechanisms: first Naqadan traders/middlemen (from the Abydos polity?) may have gone northward to obtain trade goods/materials from southwest Asia (or materials that came through southwest Asia, such as lapis lazuli) (Bard 1994b, p. 117). A study of Naqada pottery found in northern Egypt similar to that of Takamiya’s (2004b) study of Naqada ceramics found in Nubia would be useful to better understand this trade and the movement of Naqada goods northward. Traders/middlemen may have been followed by Naqadan/Abydene(?) colonization in the north (see Bard 1994b, p. 117; Trigger 1987, p. 61), and the Gerza cemetery in the north (Faiyum region) may represent a Naqada colony in Lower Egypt. According to Stevenson (2008, p. 545), material in the funerary rites of the Gerza cemetery shows “a clear affiliation with the culture of Upper Egypt,” and “a movement of people is a strong possibility.”

The final phase of Naqadan (the Abydos polity’s?) expansion northward was in the transformation/disappearance of Lower Egyptian culture by acculturation or assimilation in Naqada III times. Preliminary studies by Lorenz (2012) of ceramic style frequencies from late Predynastic levels at Sais and Buto in the Delta have suggested the transformational processes in Lower Egypt as the Naqada culture spread northward, and continued analysis of other relevant data at these sites may further elucidate this major change in late Predynastic culture.

Although warfare has been cited as an important factor in state formation (e.g., Carneiro 1970), there is no archaeological evidence of it as the Naqada culture spread into the Delta (contra Savage 2001, p. 131). Wildung (1984, p. 269), who excavated the late Predynastic/Dynasty 0/Early Dynastic site at Minshat Abu Omar in the Delta, states that there is no indication of conflict in this region of the Delta during the period of the site’s occupation, ca. 3300–2900 BC. According to van den Brink (1989, p. 90), there is no evidence of destruction layers at other recently excavated sites in the northeast Delta.

But motifs and scenes of conflict are depicted in Predynastic art, beginning with the wall painting in Tomb 100 at Hierakonpolis, and more frequently on late Predynastic/Dynasty 0 artifacts, most famously the Narmer Palette (Figs. 2 and 3). These motifs and scenes may have had symbolic meaning, such as the ruler as victor over all forces. Even though conflict between Predynastic polities cannot be specified, it may very well have been a factor as these polities expanded into each other’s territory (see Campagno 2004).

Relating to the role of warfare in the expansion of Naqadan polities, a specific interpretation of the Gebel Tjauti rock inscription (Fig. 4) has been suggested by Hendrickx and Friedman (2003), that this image depicts the victory of a late Predynastic king from Abydos, possibly the ruler buried in Tomb U-j, returning from the conquered Naqada region. Kahl (2003) has offered an alternative interpretation that the motifs in this image represent the victory over the polity at Hu, another Naqadan center in Upper Egypt, by a ruler returning to Hierakonpolis. Given that writing does not appear in the Gebel Tjauti image to specify what event was commemorated, as well as the possibility that the meaning of this image could be purely symbolic—the display of power—there does not seem to be a compelling reason for accepting more specific interpretations of this image.

Where and when internal specialization emerged in a centralized polity may point to the emergence of the early state. If the state is internally specialized in terms of separate activities that can be performed in different places at different times, as Wright suggests (1977, p. 383), the use of cylinder seals in economic activities may provide evidence of such specialization. In Egypt in Early Dynastic times, the use of cylinder seals unquestionably demonstrates internal specialization by officials of the state. But cylinder seals are rare in the archaeological record in Predynastic Egypt, unlike in Mesopotamia (where this artifact type was invented), and mud/clay sealing impressions made from cylinder seals are more common (MacArthur 2010, pp. 117–118).

Discussing the use of seals, Nissen (1988, p. 76) states that they “were instruments of economic control that could be used effectively to guarantee the supervision of proceedings.” In Egypt, Predynastic seals and their sealings were notational devices containing a limited amount of information, symbols, and iconographic motifs (and not the signs of royal names until Dynasty 0/First Dynasty). They were used beginning in Naqada II times, when there was intensive contact with the southern Levant. Vessels were imported into Egypt for their contents, but the seal impressions were made on alluvial Nile clay—evidence that there were authorities in Egypt who administered the transport of these vessels there (Regulski 2008, p. 993). Along with the sealing system there also was a system of potmarks; these two systems “are embedded in a context of exchange of goods” (Regulski 2008, p. 995). Sealings also have been found in some A-Group graves, but according to Gatto (2006, pp. 71–72), these do not attest to “the presence of a real administrative organization in Nubia.”

Although the Predynastic sealings represent increasingly sophisticated devices used in economic activities, especially in exchanges and trade, they do not necessarily signify specialized administration. What these sealings may indicate is “an increased use of visible controls on materials and an aesthetic investment in those controls that drew on motifs from the wider cultural context” (Baines 2010, p. 138).

But control of distant areas by an expanding polity (and not only exchanges with distant areas) required the development of internal administrative specialization and the delegation of authority to officials in those outposts; thus the polity had to “bureaucratize” (Spencer 2010, p. 7125). At this point in sociopolitical development in Egypt, writing would have been very useful. And by the beginning of the Naqada III period, when state formation was well underway in Upper Egypt, the invention of writing was linked to this (Jiménez Serrano 2008, p. 1133).

To date, the earliest known writing has been found only at Abydos. The evidence of writing in Tomb U-j at Abydos has sometimes been interpreted as an administrative/economic use (Dreyer 1998, p. 89), but this interpretation also has been questioned (see Stauder 2010, pp. 143–144). The different types of signs, uses, and media, however, suggest some kind of specialized administrative organization, especially of persons (officials?) who were trained to “read” the meanings of specific signs of different types, used on different materials, which were mutually intelligible over long distances.

The inscriptional evidence from Tomb U-j is a very limited system of writing, and it is “unclear” as to whether the signs have phonetic values (Stauder 2010, pp. 140–141). Three types of inscribed material have been found in Tomb U-j (see Dreyer 1998): almost 200 bone and ivory tags, with numerals, or signs/hieroglyphs; wavy-handled jars for oils/fats(?) with large painted signs of the same system; and clay sealings of pictorial motifs but not writing per se.

The “signs” on the tags represent the earliest known writing (Fig. 5). They also represent two forms of writing known later: hieroglyphs and cursive/hieratic (Baines 2004, pp. 154, 158, 2010, p. 140). The tags have small holes in one corner and were originally attached to goods, possibly bundles of cloth (Stauder 2010, p. 138). Most of the tags have two signs, which are probably (place) names and names of “prestigious beings (divine entities, ruler[s])” (Stauder 2010, p. 139).

Regulski (2010, p. 17), however, argues that while signs engraved on the tags can be read as toponyms, in a developed system of writing, this cannot be attested for the painted signs on jars from this tomb, and an understanding of these painted signs is more complicated. It has been suggested by the excavator that these tags were probably made and attached to the tomb goods near the Abydos cemetery (Dreyer 1998, p. 137). Thus, while the jar inscriptions and sealings were part of a complex (inter)national exchange network, the signs on the tags found in Tomb U-j are the earliest representatives of a writing system that emerged in relation to craft units in the Abydos region (Regulski 2008, p. 999).

According to Engel (2013, p. 24), some of the inscriptions from Tomb U-j are references to locations, probably provenances. This category of inscriptions indicates “at least one unit responsible for equipping the tomb,” which collected, controlled, repacked, and labeled commodities coming from as far away as the Delta and First Cataract (Engel 2013, pp. 24–25). Other “units” also may be suggested by imported grave goods and sealings in the tomb (Engel 2013, p. 25). Thus inscriptions on artifacts in Tomb U-j are not only the earliest evidence of writing; the amassing of the entire group of tomb goods also suggests the existence of specialized units/institutions of administration.

Regulski (2008, pp. 1001–1002) states “the creation of a writing system was a conscious court initiative in a time when many clusters of alternative systems of communication existed.” These alternative systems of communication included signs and symbols on seals/sealings, but the codification of the writing system involved a long process in which some signs of earlier traditions were adopted into the formal writing system, and others were ignored (Regulski 2008, p. 1001). This codification of writing took place at Abydos. It correlates with increasing interactions between different regional polities and, according to Regulski (2008, p. 1002), the establishment of a central “court” there at end of the Naqada II period. The Naqada IID period is also when Josephson and Dreyer (2015) place the “birth of an empire,” when evidence of kingship, writing, and organized religion co-occur. The intentional invention of writing was not only associated with the probable northward expansion of the Abydos polity—which would evolve into a highly centralized state—and the usefulness of writing for administration of this state, but it also was associated with the newly evolving institution of kingship there.

If the earliest Egyptian state emerged at Abydos by 3200–3150 BC (as seen in the burial of a ruler in Tomb U-j, which also contained the earliest evidence of writing), what was happening in the rest of Upper Egypt? In the Naqada cemeteries there is evidence of the impoverishment of the Naqada III grave goods (Bard 1994b, p. 108), which Trigger suggested may reflect the absorption of the Naqada “statelet” into a larger political system nearer the beginning of the First Dynasty (Bruce Trigger, personal communication 1987). By Early Dynastic times, Naqada had become an insignificant center.

At Hierakonpolis, the Naqada IID period is “a blank,” according to Friedman (2011, p. 43). When there are more data in Naqada III (Dynasty 0), power had shifted north to Abydos, but how this occurred is a mystery (Friedman 2011, p. 43). The emergence of an uber-polity at Abydos is especially problematic since evidence from Naqada II times comparable to what has been found at Hierakonpolis has not been preserved or found at Abydos.

Kemp (2006, p. 76) has proposed a hypothetical map of the most important “protostates” of Upper Egypt centered at Hierakonpolis, Naqada, and Abydos/This (unknown archaeologically). Kemp (2006, p. 74) suggests that the growth of the early state may be analogous to game playing: “from essentially leaderless aggregations of farmers, communities arose in which a few were leaders, and the majority were led.” But how leaders arose in prehistoric times and some polities emerged as larger more powerful aggregates than others cannot be specified. Ethnographic analogies concerning the evolution of leadership can certainly be suggestive of this process (e.g., Dallos 2013; Flannery 1999; Flannery and Marcus 2012; Vaughn et al. 2009), but the specific trajectory of the emergence of leaders and polities in fourth millennium BC Egypt remains hypothetical. There must have been individual agents who seized opportunities for control and extension of the political economy, especially if incipient bureaucracies were in place that helped reinforce their control (and other agents who tried and were not successful), but such agents remain unknown in prehistory.

Andelkovic (2011, pp. 28–31) has proposed a six-stage unilinear model for the evolution of political organization in Upper Egypt, with an “Upper Egyptian protostate” emerging in Naqada IIC-IID1. This Upper Egyptian polity was “ideologically, economically and militarily ‘glued’ to the most powerful polity, probably Hierakonpolis or Abydos” (Anđelković 2011, p. 29). But the processes of competition, conflict, coercion, and allegiance building cannot be specified, and how this polity was organized and how independent or dependent were its constituent groups cannot be determined.

By Naqada III times Naqadan control and material culture extended to the Delta, but how “unified” the entire country was politically at that point remains speculative. Within that time frame, a large territorial state emerged that was ruled by kings who were buried at Abydos (Cemetery U) in Upper Egypt but whose capital was eventually located at Memphis in Lower Egypt.

But Hierakonpolis was not completely out of the picture in Naqada III times. Earlier excavations at HK6 by Hoffman uncovered four large Naqada III tombs lined with mud bricks. The earliest of these tombs, Tomb 11, contained the remains of a wooden bed with carved bull’s feet and beads and amulets of costly imported materials: gold, silver, carnelian, garnet, copper, turquoise, and lapis lazuli (Hoffman 1987, pp. 221–233). Unfortunately, who as well as what political role those buried in these tombs had cannot be determined. Unlike Tomb U-j at Abydos, there is no evidence of the use of the earliest writing in these high-status Naqada III burials at Hierakonpolis. If the invention of writing is one criterion for the earliest state in Egypt, it was used only at Abydos and not at Hierakonpolis.

Although royal burials were located at Abydos in the Naqada III period, Hierakonpolis was where the earliest, large high-status burials (of Naqada culture rulers/chiefs?) were found. Some ideas that were later associated with Egyptian kingship may have originated at Hierakonpolis, such as the association of the Egyptian king’s name in the format of the serekh with the falcon, the earliest known image of which (in malachite) comes from Structure 7 in the “Pillared Hall” precinct of HK6 (Friedman 2011, p. 42). This structure and others like it in the HK6 cemetery are also the earliest evidence of “mortuary temples,” and rituals associated with the highest-status burials in this cemetery (Friedman 2011, p. 41) are later associated with the royal burials at Abydos.

The Predynastic evidence at Hierakonpolis (both settlement and mortuary) for all Naqada periods has been exceptionally well preserved for excavation in the later 20th and 21st centuries, unlike what is known at the other two major Predynastic centers in Upper Egypt, Naqada, and Abydos. One can only hypothesize that similar evidence has been destroyed at these sites. The Hierakonpolis evidence also includes a ceremonial center at HK29A, which consists of a large-walled oval courtyard, possibly where the cult and rituals relating to rulership first emerged in Egypt; this ideology became very important in Dynastic times. The importance of such a ceremonial center for the development of the later Egyptian state is suggested by Perry (2011, p. 1271): ritual activities at Hierakonpolis provided opportunities for the elite and rulers to act as “sacred mediators.” Sacred space and monuments were created at Hierakonpolis, which required the mobilization of labor, perhaps initially through collective action. Festival activities required the mobilization of commodities and the control of craft production for ritual artifacts. Thus, at Hierakonpolis, it was an elite that eventually “crafted a new synthesis of ideological, political and economic power” (Perry 2011, p. 1271).

The spread of southern/Naqadan beliefs to the north probably helped legitimize the control and then the rule of the Naqadans there. As Naqadans expanded northward, they took their mortuary cult, the evidence of which first appeared at Gerza and then later in the Delta. They probably also took their cults of deities, which have not been preserved in northern Egypt until quite late in the Predynastic sequence, when votive figurines are found at Tell el-Farkha on the Western Kom in the administrative-cultic center dating to Dynasty 0 and the early First Dynasty (Ciałowicz 2009, 2012a, pp. 206–231). Similar votive figurines of the Early Dynastic period also have been found at Tell Ibrahim Awad in the northeastern Delta and at Abydos, Hierakonpolis, and Elephantine in the south. Most likely, these deposits of votive figurines were associated with temples where they had been left as offerings (Teeter 2011a, p. 208). When these temples were later dismantled and rebuilt, the offerings had been collected and intentionally buried. Thus by Dynasty 0, certain offering rituals were being performed in both northern and southern Egypt, in a cultic belief system that was pan-Egyptian.

But even earlier, on the Eastern Kom at Tell el-Farkha in the Delta, was a settlement area in which fragments of two gold-covered male statuettes (30 cm and 57 cm long) were found, along with two elaborate flaked stone knives of Naqada IID and early Naqada III date, and a necklace of carnelian and ostrich eggshell beads (Ciałowicz 2011, p. 61, 2012a, pp. 201–206). The gold figurines were originally held together by gold rivets and had inlaid eyes of lapis lazuli (Chłodnicki and Ciałowicz 2007). The gold for these statuettes most likely came from Upper Egypt (and the lapis lazuli from eastern Afghanistan). Although Cialowicz (2011, p. 61, 2012a, p. 206) suggests that the figurines are those of a ruler and his son, it is also possible that these figurines were cult statues (of deities?), brought from the south along with the beads and flaked knives of southern origin found in this hidden cache.

Somewhat later in date at Tell el-Farkha (ca. 3200–3100 BC) is the largest known (mortuary) structure in Egypt from the period—a large mastaba in the necropolis area (Ciałowicz 2011, p. 62). The symbolism of power in the mortuary cult (see Bard 1992) was now found in the far north of Egypt; slightly later, another large mastaba tomb is known at Naqada, the “Royal Tomb” of Neithhotep, whose son was Aha, first king of the First Dynasty, who was buried at Abydos. Possibly Neithhotep was from Naqada, hence her burial there, but the union that resulted in the issue of Aha may have been a political one between a ruler at Abydos and the ruling family at Naqada—another form of alliance making. As the Dynastic state emerged, centralized power shifted from its origins in polities of the southern Naqada culture to the north.

Postscript to State Formation: The Early Dynastic State and the Development of the Pharaonic State

The linear—and circumscribed—geography of the Nile Valley, cut off by deserts to the east and west, greatly facilitated transportation and communication by boat within the Dynastic kingdom, from the First Cataract at Aswan to the northern Delta. The great potential of floodplain agriculture in this environment ensured the accumulation of agricultural surplus in most years. All of the basic resources that sustained life in this kingdom were available locally: fresh water, cultivated cereals and animal protein, materials for building and clothing, and chert for tools. Stones and minerals from quarries and mines outside the Nile Valley, as well as long-distance trade in exotic imported materials, were managed by the state through state/military expeditions. Thus the geography of the Nile and its resources greatly facilitated the formation of the authoritarian pharaonic state, but it did not determine its formation. The authoritarian ruler-controlled state became the most effective (and exploitative) sociopolitical organization for Egypt for the next 5,000 years, whether the authoritarian ruler was Egyptian or foreign.

Blanton and Fargher (2008, p. 93) state that ancient Egypt conforms to the “main expectations” of neoevolutionist theory, with “the permanent tendency of a highly centralized government to remain in the hands of a small wealthy elite.” With the emergence of the First Dynasty, a new capital was founded at Memphis in the north, where power became centralized, as evidenced in the cemeteries on both sides of the Nile in the vicinity of Memphis (see Mortensen 1991, p. 23). The highest-status officials of the state were buried in elaborate tombs at North Saqqara, just west of Memphis. Archaeological evidence relating to the founding of the capital city would be very useful, but unfortunately the earliest levels there, east of the Early Dynastic cemetery, are now well below the water table (Jeffreys 1997, p. 10). In the south, Abydos remained symbolically important because kingship of this unified state continued to be associated with (the earlier polity of) Abydos, and all the kings of the First Dynasty were buried there. Political authority became institutionalized in the position of the king, who ruled from the capital of Memphis but was buried at Abydos.

In Predynastic Upper Egypt, there is no evidence of strong urban competitors as the state formed; leadership was supralocal and political groups were based on territories, not cities. As the Early Dynastic state formed, a capital city was located at Memphis, and regional units developed that aided state control over this large, linear, territory. Lehner (2010, p. 86) has discussed a process of “internal colonization” in the Old Kingdom, especially in hinterland regions of Middle Egypt, perhaps in part to “feed” the pyramid projects. Thus urbanism developed gradually, as towns and cities became the nexus of state control as well as ritual/temple centers.

The early state of the First and Second Dynasties (ca. 3000–2686 BC) was when institutions of state control developed into those that are seen in the long-term state of the Old Kingdom (Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Dynasties, ca. 2886–2125 BC). At the base of the Egyptian state economy was agricultural surplus, which was controlled through taxation as well as direct control/ownership of agricultural estates/land by the Crown and pious foundations (mortuary and temple cults).

State tax collection may have begun as early as Dynasty 0, according to the interpretation of a rock drawing in the Aswan region at Nag el-Hamdulab. This scene and its hieroglyphic text (“Nautical Following of [Horus]”) may depict the biennial traveling of the king and court not only in a display of power but also for the purpose of tax collection (Hendrickx et al. 2012, p. 1081). Darnell dates the rock art to the reign of Narmer and states that the early text describes the “Following of Horus” ritual that involved the confirmation of royal ritual power and physical taxation, and the incorporation of a marginal area [Egypt’s southern boundary] and its inhabitants (Darnell 2015, p. 19). According to Gatto (2014, p. 117), the location of this scene suggests a strong need by the newly established Egyptian elite of ideological and political control at its southern border.

Also from Dynasty 0 and the early First Dynasty are the so-called “tax annotations”—painted inscriptions on vessels about the delivery of commodities along with the serekh of the king (Dreyer 1992a, pp. 259–263; Engel 2013, p. 25). At this early point, administration evolved around the royal household (Engel 2013, p. 37).

In the third millennium BC, agricultural units of the Crown as well as administrative units were established throughout the country (Moreno García 2013, p. 93). Initially, these administrative units, conventionally called “nomes,” may have built on a distribution of existing centers, but during the course of the third millennium BC “they started shaping the administrative and social map of Egypt” (Bussmann 2014, p. 84).

Kings spread their authority over the large state territory, and elites were successfully integrated into the state structure by diverse solutions (Moreno García 2013, pp. 86–87). This integration was so successful that there were no internal threats to royal power until the end of the Old Kingdom (ca. 2125 BC). Although the material evidence is informative on kingship, early writing, and administration, Bussmann (2014, p. 79) points out that it remains obscure how the core of the early pharaonic state was embedded in the territory it claimed to administer, and several organizational principles were operative as the early state developed throughout the third millennium BC. Not until the late third millennium BC did the important role of local cult temples emerge, with the blending of central and local concerns (Bussmann 2014, p. 88).

Human resources (for state projects and expeditions, as well as the military) were recruited and/or conscripted. Foreign captives became slaves in Egypt, but there was no large underclass of Egyptian slaves. Even in the mid-third millennium BC when the Giza pyramids were built, the work force consisted of different groups. Lehner (2015, p. 500), the excavator of the pyramid workers’ towns at Giza, suggests that, based on Old Kingdom texts and scenes that correlate with archaeological evidence at the Heit el-Ghurab site, the pyramid work force consisted of a wide variety of workers: young recruits (nfrw) in gangs and crews; specialized quarrymen and craftsmen; scribes and administrators; bakers and brewers; shipwrights, carpenters, and stevedores, either foreign (Asiatic) or Egyptian; dependents (mrw.t) of households, estates, and villages; and captives from Nubia, Libya, or the Levant. Graffiti of builders found in pyramid complexes of the Old and Middle Kingdoms indicate that workers were conscripted for labor away from their home districts in Middle Egypt and the Delta (Lehner 2015, pp. 493–494).

Wealth finance, the procurement of status goods through long-distance exchange or craft production, given to supporters (D’Altroy and Earle 1985, p. 188), was transformed in Dynastic times as much long-distance trade and exchange came under state control. The production of high-status, prestige goods, some of which were made of costly imported materials, provided artifacts that were given to officials in a rewards system, a mechanism encouraging cooperation (Carballo 2013, p. 13). Some of the prestige goods of Egyptian officials later went into their tombs.

External revenues for the Crown would have included much foreign trade (and long-distance networks) to secure valuable raw materials and most mining and quarrying operations. But how the political economy of earlier rank societies/chiefdoms, which controlled networks, trade, trade goods, and specialized production, became transformed into the state economy is not clear. Specific evidence that may be especially useful in elucidating changing organization of the political economy and trade networks as the early state emerged would be a study of sealings in Egypt, Nubia, and the southern Levant from Naqada II times into the Early Dynastic period in terms of their content, context, and uses.

Harrison (1993, p. 81) describes the changing trade relations of Egypt with the southern Levant: trade in EB I/later Predynastic times was conducted by “middleman” exchange, which disappeared with political unification in Egypt and “a more centralized network of economic trading activity.” Likewise Levy and van den Brink (2002, p. 28) state that the presence of royal serekh-signs all over the northern Negev during the late EB I/Dynasty 0 “is a clear indication of state sponsored interaction under one king—(Horus) Nar(mer).” In late EB IB, the first royal Egyptian enterprise was established in the southern Levant, which included a fortified center at Tell es-Sakan and a network of Egyptian trading posts (Hartung 2014, p. 114).

With the beginning of the First Dynasty and EB II, Egyptian trade interests shifted to the northern Levant where oils, resins, and wood could be found (Hartung 2014, p. 114; Sowada 2014, pp. 293–294). Stager (1992, pp. 40–41) proposes that Mediterranean shipping (the “Byblos run”), which only the state could support, replaced overland transport, and the economic focus shifted to sea-based exchange (Marfoe 1987, pp. 26–27; Sowada 2014, p. 299; see also Marcus 2002, pp. 407–410). In Nubia, Takamiya (2004b, pp. 59–60) proposes that, based on the presence of cylinder seals (and sealings), exchange was organized by the Egyptian state at the beginning of the First Dynasty, but this trade ended early in the dynasty, most likely as a result of Egyptian military penetration there.

The ancient Egyptian ruler also controlled state ideology. In the third millennium BC, temples and ceremonial centers were constructed and marked, along with royal administrative and agricultural units, the domain and power of the king (Moreno García 2013, p. 93). The king’s powers were not only temporal but also extended into the afterlife, symbolized in royal tombs in which the king was buried quite differently from everyone else, in large, richly furnished monuments with attached cults. This was an ideological development that began in Predynastic Upper Egypt, where “the motor of those processes that led to the formation of the pharaonic state” developed in central places there—increasing social stratification, the elaboration of funerary culture, and the creation of a visual language for kingship (Bussmann 2014, p. 82).

The Egyptian king was depicted in art, such as on the Narmer Palette, with the symbols of kingship, such as the Red and White Crowns of Lower and Upper Egypt, in scenes in which he was larger in scale than any other figures, symbolizing his position (see Figs. 2 and 3). His depiction of “subjugating the enemy” on the Narmer Palette, in which he raises the long-handled mace to strike his enemy, which is also found on later temple walls, was first portrayed in an incipient form on the wall of the Predynastic (Naqada II) Decorated Tomb at Hierakonpolis (see Köhler 2002, pp. 500–503).

Central to ancient Egyptian kingship was the concept of ma’at, requiring the king to maintain internal order and dispel chaos/isfat (see Richards 2010, p. 56). Depicted on the Narmer Palette is this concept of the king maintaining cosmic order by subduing Egypt’s external enemies, in which the subjugation motif became integrated in early Egyptian state ideology (Köhler 2002, p. 511). Ma’at also legitimized the king’s role, one in which moral authority became an integral part of political centralization.

In Dynastic times, the king (or usually a priest who served as his surrogate) performed rituals in temples. In the daily temple ritual, the chief priest would be specially purified, and he was transformed into a surrogate for the king (Teeter 2011b, p. 47). On the walls of later better-preserved temples (mainly from the New Kingdom, beginning ca. 1550 BC, and later), he was depicted performing rituals that also demonstrated his kinship with the gods and his exclusive access to them. But not much is known about early temples, which have not been well preserved, and Wendrich (2010, p. 276) has cautioned about the danger of interpreting early evidence from more explicit later sources.

While there were separate cults of different local deities throughout Egypt, these cults were syncretized into a state religion, which legitimized kingship, instead of producing divided and competing local loyalties of different centers. Constructed genealogies of gods provided specific relationships of this synthesis (see Lesko 1991), and the king’s kinship and special relationship with the gods were the foundation of state religion in which the king supported local cults in a state system of religion.

Although there may have been regional and cultural differences in Egypt in Predynastic times, when the country was unified a concept of “Egyptian” identity seems to have developed within this linear territorial state. The creation of the Egyptian identity helped justify political power and consequently created the concept of a duality of “Egypt in opposition to the others,” especially in boundary regions such as the First Cataract (Gatto 2014, p. 115).

As the early state was created, an ideology and identity were forged that underpinned its unity (Baines 1996, p. 361). This ideology held a rigid distinction between Egypt and the outside world, and between Egyptians and non-Egyptian inhabitants of a chaotic world beyond its boundaries (Schneider 2010, p. 147; Wilkinson 2002, p. 518), including Libyans, Nubians, and Asiatics. Although the evidence for Egyptian identity comes from elite culture, which was certainly biased, there seems to have been no strong ethnic competitors within this large kingdom during periods of the strongly centralized state (Old, Middle, and New Kingdoms). This concept of “Egyptians” versus all outsiders may have helped give a sense of social unity to the kingdom.

Writing developed in full in Egypt in Dynastic times, in both hieroglyphic and hieratic (cursive) forms. Writing not only helped in the management of the complex organization of the state, but it also expressed the role of the king, his officials, and other Egyptians, as well as their beliefs, in both cult and mortuary contexts. Although there may have been dialects in the spoken language, the written language was mutually comprehensible to those who could read and write (admittedly elites) throughout the kingdom. Shared language also may be a factor in shared ethnic identity (Levy and van den Brink 2002, p. 5).

Conclusion

Recent analysis of radiocarbon data provides a new absolute chronology for early Egypt, demonstrating a shorter span of time from the early Predynastic period, when people began to live in settled agricultural villages in Upper Egypt, to when the Early Dynastic state emerged. This chronology is considerably shorter than previously thought, only between 600 and 700 years (Dee et al. 2013, p. 8). Thus, this chronology lays a new foundation for the study of state formation in Egypt, a process that now seems all the more remarkable given the shorter time span.