Abstract

The abundance of information technology and electronic resources for academic materials has contributed to the attention given to research on plagiarism from various perspectives. Among the issues that have attracted researchers’ attention are perceptions of plagiarism and attitudes toward plagiarism. This article presents a critical review of studies that have been conducted to examine staff’s and students’ perceptions of and attitudes toward plagiarism. It also presents a review of studies that have focused on factors contributing to plagiarism. Our review of studies reveals that most of the studies on perceptions of plagiarism and attitudes toward plagiarism lack an in-depth analysis of the relationship between the perceptions of plagiarism and other contextual, sociocultural and institutional variables, or the relationship between attitudes toward plagiarism and students’ perceptions of various forms of plagiarism. Although our review shows that various factors can contribute to plagiarism, there is no taxonomy that can account for all these factors. Some suggestions for future research are provided in this review article.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The difficulty of writing in English is not only a case with non-native speakers of English, but also with native speakers of English. This view is not surprising and may not be disputed because producing coherent and well-organized texts is not an easy task. This is stressed by Hyland (2003) who stated that the requirements for mastering the writing skill include extensive and specialized instructions (Hyland 2003). Thus, for many teachers, a major focus of their work is on how to prepare learners to cope with the language requirements, particularly the writing requirements for university courses (Bruce 2008) and similarly for postgraduate studies. Taking this into account, having a good understanding of the common and disciplinary conventions of academic discourse is a significant prerequisite for students and researchers who are keen to establish their careers and to successfully navigate their learning (Hyland 2009).

Due to the vast majority of themes of studies on plagiarism and the increasing number of plagiarism cases reported by universities in several countries, this article presents a critical review of studies that have been conducted on perceptions of plagiarism and attitudes toward plagiarism. Another objective of this study is to review studies that have focused on factors contributing to plagiarism, highlighting factors that can be addressed by educational institutions to curb plagiarism. The rationale of the selection of these three themes is presented below.

Rationale for the Themes Selection

It is significant to provide an explanation for the choice of perceptions of plagiarism, attitudes toward plagiarism, and factors affecting plagiarism discussed in this review article. The selection of these three themes reviewed in this study was done for the following reasons.

First, these three themes are important issues that have remarkably attracted researchers’ attention and resulted in several published research articles. Through reviewing these studies, this review provides some recommendations for future research that can most probably focus on various interrelated themes related to plagiarism which can lead to some practical implications. Second, perception of plagiarism and attitudes toward plagiarism are critical issues because they can affect the judgment and action of individuals (postgraduate students and academics). Perception is viewed here as the process of recognizing, organizing and interpreting sensory information. Third, perceptions of plagiarism and attitudes toward plagiarism have received researchers’ attention from various geographical contexts and cultures because cultural factors can influence the conceptualization of plagiarism. Fourth, as methods of acting and interaction can vary from one culture to another, value systems may yield different perceptions of the world and its aspects (Hofstede et al. 1991). Consequently, plagiarism may be practiced differently from one culture to another (Pennycook 1996, 2001; Bloch 2012; Sowden 2005). While plagiarism may have one form as blatant plagiarism in a culture, it may have various forms in another culture. Furthermore, while plagiarism may be considered a problem in some regions, it may be acceptable in some other regions. That is to say, factors contributing to plagiarism may be different from one culture to another based on how a discourse community in a particular culture conceptualize plagiarism. However, some researchers such as Wheeler (2009) and Chien (2014) argued that lack of knowledge with respect to the meaning of plagiarism is the key factor, not a cultural issue. Fifth, faculty members’ attitude toward plagiarism is an important issue because it can affect their students’ conceptualization of plagiarism in the educational institutions where these faculty members work. Consequently, such attitudes, either positive or negative, may affect individuals’ behaviours including academic misconduct behaviour. Sixth, attitudes toward plagiarism is a critical issue because a comprehensive examination of the reasons for plagiarism that can include specific attitudes toward plagiarism can provide constructive feedback to educational institutions concerning establishing educational and training programs meant to train students and academics to curb plagiarism. Furthermore, this feedback can help educational institutions to create academic codes for academic integrity.

Seventh, recent studies have confirmed that perception is one of the most important avenues for research on plagiarism (e.g., Babaii and Nejadghanbar 2016). Eighth, most of the studies on plagiarism have shown that students in higher education in various contexts do not have a clear understanding of what constitutes plagiarism (e.g., Gullifer and Tyson 2014; Shirazi et al. 2010). Ninth, these two themes have attracted several researchers to examine students’ perceptions of plagiarism and attitudes toward plagiarism. For example, Leonard et al. (2015) have recently argued that “issues of academic integrity, specifically knowledge of, perceptions and attitudes toward plagiarism, are well documented in post-secondary settings” (p. 1587). Tenth, for institutions in higher education to construct their policies, they need to provide definitions of various forms of academic misconduct, such as plagiarism, based on students’ and staff members’ understanding and perceptions of various forms of misconduct. This is supported by Chen and Chou (2016, p. 2) when they stated,

Although students’ vague definition of plagiarism and the lack of knowledge about penalties for plagiarism sometimes cause plagiarism, faculty members should also recognize their responsibility to prevent plagiarism, for example, in setting up a clear-cut classroom policy toward plagiarism and structuring meaningful assignments to guide students to behave ethically.

Eleventh, the importance of the themes of perceptions and attitudes does not stem from the total number of studies carried out on these two issues. Rather, their importance is related to their priority in the accumulated number of research on plagiarism. Twelfth, dealing effectively with the complex issue of plagiarism should be based on staff’s and students’ definitions and interpretation of this concept. For example, supporting previous literature, Flint et al. (2006) noted that “In order to deal with issues of plagiarism effectively and equitably, it is necessary for staff, students and departments to be working from the same definitions and interpretations” (p. 146).

It is widely accepted that when the practice of academic writing started a long time ago, there was neither the technology nor detection software programs to detect plagiarism. Similarly, perceptions and attitudes toward plagiarism should precede other themes related to plagiarism, such as awareness of plagiarism and how to use some modules to curb or at least decrease the prevalence of plagiarism.

Conceptualization of Plagiarism

It has been noticed that students’ and researchers’ inability to understand what constitutes plagiarism has contributed to the existence of more cases of plagiarism and increased anxiety about unintentional plagiarism (Breen and Maassen 2005; Gullifer and Tyson 2014). Additionally, it has been pointed out that standard definitions of academic dishonesty, misconduct, plagiarism, and integrity do not exist in the literature (Gullifer and Tyson 2014). This has been confirmed by Perry (2010) who claimed that there is uncertainty regarding the interpretations of plagiarism. Furthermore, investigations of how universities define these constructs, especially plagiarism, have demonstrated some critical differences and potential problems for students (Davis 2012). Thus, it can be argued that most studies conducted on plagiarism have adopted a particular definition of plagiarism, except for studies focusing on respondents’ interpretation of plagiarism. As such, instead of giving a particular definition of plagiarism, various conceptualizations of plagiarism are presented in this section.

One of the earliest conceptualizations of plagiarism is a legal one. Adopting this conceptualization, Park (2003) has justified this by mentioning that cases of plagiarism went beyond the academic sphere and reached courts in the USA. This conceptualization of plagiarism is related to copyright abuse. In this conceptualization, plagiarism can be equal to theft which is defined in jurisdiction as the “appropriation of property of another with intent to deprive the rightful of its use” (Fishman 2009, p. 2). In addition, this conceptualization is very much associated with the etymology of the word plagiarism which was derived from the Latin word plagiarius (kidnapper) which indicates theft (refer to Howard 1995). However, Fishman (2009) rejected this conceptualization of plagiarism because taking the property of others should have been done with the intention of permanent seizure of other’s property.

Some studies considered plagiarism as a form of cheating, academic fraud, and fabrication (Ashworth et al. 1997; McCabe 2005). Focusing on university policies in Australia, Canada, the USA, England, New Zealand, and China, Sutherland-Smith (2008) found that definitions of plagiarism included graded levels of plagiarism, copying words, and/or the intentional use of the other’s words and works. Defining plagiarism as stealing, through copy-and-paste, words, texts, or someone else’s ideas and passing them off as one’s own without proper acknowledgments of the source has been embraced by some scholars such as Park (2003) and Yeo (2007). In an Australian university, Yeo (2007) examined undergraduate science and engineering students’ understanding of the concept of plagiarism and found that the students considered copying assignments and using cut-and-paste strategy as serious forms of plagiarism. However, this adopted definition has been rejected by Briggs (2009) who strongly argued that using others’ words is a stage in the development of writing skills.

To sum up, the debate of having a standard definition of plagiarism continues even with the current suggested definitions of plagiarism and policies (Perry 2010) because so far it is obvious that institutions do not agree on what constitutes plagiarism. Most of the definitions of plagiarism revolve around improper citation and cheating (Kasprzak and Nixon 2004; Amiri and Razmjoo 2016). How plagiarism is defined is thus based on the policy of a university and sometimes may be based on studies on how students and academics in that particular university or context define it. However, most of the scholars have agreed that plagiarism has something to do with taking texts and ideas from others in an unethical manner and passing them off as one’s own ideas or works (Gullifer and Tyson 2014). This general agreed-upon definition was proposed by Carroll (2002) who emphasized that passing off someone else’s work as one’s own includes intentional and unintentional cases. This has been adopted by Perry (2010) and some other researchers. Based on the aforementioned argument, one can conclude that a concrete definition of plagiarism and a straightforward classification of it is very necessary to help universities and learning institutions to establish polices to handle this problem (Wager 2014). All stakeholders in any university setting must abide by the definitions of plagiarism and other forms of academic misconduct because these definitions are considered as parameters for reporting, investigating, and penalties (Gullifer and Tyson 2014).

Writing in Higher Education and Plagiarism

With reference to the importance of having a good command of academic literacies requirements including reading and writing skills, it has been pointed out that in all institutions of higher education, undergraduate and postgraduate students are required to produce texts which belong to various academic genres, such as assignments, reports, laboratory reports, essays, and theses. For example, at the postgraduate level, students depend on reading and writing skills more than other language skills because they need these two skills to write research articles, reports, dissertations, and theses (Paltridge and Starfield 2007). However, the production of these genres in any context, especially theses and dissertations, is not an easy task as these genres involve tedious work over years (Paltridge 2002). Specifically, students who are at the beginning of their university studies may face a multiple range of difficulties and adjustments because the majority of these difficulties are related to associated difficulties as in how to use English language skills to meet the requirements of academic activities which are not familiar for the new students (Biber 2006).

Writing critical essays, theses, and dissertations has been identified as one of the most recurring writing practices for undergraduate students in many universities. In producing finished texts for each of these genres, students need to possess a specific background on how to construct texts which should be recognized by members in their academic community. Specifically, in order to construct and interpret meanings in typical academic contexts, writers should take into account that a text is a product which is affected by various sociocultural and individual factors that interact in a complex way with other institutional factors. Due to difficulties in producing these genres, undergraduates and postgraduates may be tempted to rely on plagiarism, either intentionally or unintentionally, to complete their writing assignments and requirements. Plagiarism, which is considered to be an unethical issue, including other forms of academic misconduct, has been an issue of focus in recent years.

To ensure academic integrity, plagiarism has been a concern in most institutions of education because they have to do plagiarism check when assessing students’ writing and performance to assure high standards in these institutions (Ford and Hughes 2012). In addition, plagiarism has been identified as a serious problem for universities (Ehrich et al. 2014). Academic integrity is a broad term used to identify ethical behaviour in educational settings; and for students, this term reflects honesty in the work completed in and out of the classroom (Zivcakova and Wood 2015). Another term used to refer to contexts where there is a case of violation of ethical behaviour is academic misconduct (Zivcakova and Wood 2015) which may include plagiarism, unauthorized collaboration on tests and assignments, and fabricating or falsifying data and/or a bibliography (Baetz et al. 2011; Zivcakova and Wood 2015). It is significant to mention that academic misconduct is widespread and is not specific to a particular discipline, year, or learning context. Plagiarism which has been found to occur across all levels of academia, undergraduate and postgraduate, is the most serious form of academic misconduct (Decoo 2002). In fact, plagiarism has been considered by some researchers (e.g., Lau et al. 2013) as a global problem, especially among students. This is because several researchers have noted that there are diverse definitions of plagiarism (Flint et al. 2006), and this makes understanding how plagiarism is perceived a difficult task (Divan et al. 2015).

Search Method

During the past ten years a large number of articles in various journals have reported findings of research related to plagiarism. Although the topics that have been the focus of these articles are many, the three themes that have yielded the most prominent attention from researchers are perceptions of plagiarism, attitudes toward plagiarism, and factors contributing to plagiarism. Thus, in this article, the focus is on reviewing studies that have examined these three issues. The studies that are reviewed here cover the period from 1997 to 2016. The articles identified here have covered various geographical regions with different variations of the respondents’ background and fields of study. Furthermore, the studies on plagiarism have examined several issues in various contexts.

The Scopus search machine was used to retrieve a list of articles that have focused on plagiarism. Using this strategy to retrieve articles on plagiarism, it was found that the number of studies exceeded several hundreds of studies. Table 1 (see below) demonstrates the stages of the selection process of the articles reviewed. In the selection process, two important parameters were used, period of publication and type of document. The period covered refers to the years in which the retrieved documents/research articles were published, and the type of document refers to the genre of the document (such as conference paper and research article). As shown in Table 1, in all stages of the selection, the period of publication is 1980–2016. However, in Stage Five, the Scopus search machine did not give research articles that were published before 1997 because research articles published before this year do not have perception, attitude or factors in their titles, keywords or abstracts. The second parameter for the selection of documents was document types (genres of the documents). At the beginning of the selection process, in Stage One, the types of documents that were included are research articles, conference papers, editorials, letters, notes, reviews, book chapters, short surveys, articles in press, and books. However, in the following stages of selection only research articles were retained and the other types were excluded.

It is worthy to mention that there are various definitions of a research article. In this review article, a research article is a term used to refer to “an article that includes original research and primary sources” (Michalec and Welsh 2007, p. 68). Only research articles were reviewed for some reasons. First, it has been pointed out that “for most disciplines the research article is considered the principal transmitter of disciplinary knowledge at the expert level” (Silver 2012). Second, among academicians a research article is considered as a typical genre which is a well-written piece of written text in which language is used in a conventionalized setting (Swales 1990). Third, a research article is an academic genre that is published in a peer-reviewed scholarly journal and it presents the findings of original research that contributes to the body of knowledge in a given discipline. On the other hand, conference papers and book chapters do not undergo rigorous review by experts who can provide feedback and recommendations for publication or otherwise.

In Stage One, Scopus search engine was used to retrieve all documents that have the keyword plagiarism in the title and the outcome was 1869 documents. To filter this large number of results (number of studies), only research articles were retained. In Stage Two, there were 692 research articles which included various themes published in several languages. This was followed by including only research articles published in English and the outcome was 629 research articles as given in Stage Three. In Stage Four, only research articles that have focused on perceptions of plagiarism, attitudes toward plagiarism, forms of plagiarism, detection of plagiarism, factors contributing to plagiarism, online/digital plagiarism, and a few more themes were included. In the last stage, the researchers modified the conditions of search and also used the Scopus search engine to retrieve studies that included perception/attitude/factors and the relevant word plagiarism in their titles. After retrieving the list, the abstract of each article and sometimes the entire article were examined to produce our classification. It might be artificial and difficult to classify journal articles based on a single theme because articles may have more than one central focus. However, classifying the articles in such a way could be a reasonable way of providing a synthetic overview of what was published on perceptions of plagiarism and attitudes toward plagiarism over the period specified. The three authors of this review article, met several times while working on this project to solve these hurdles and challenges they faced in terms of selection of articles and writing the review. We determined that perceptions and attitudes were the most prominent themes as justified in the Introduction section above.

This review article starts with some introductory remarks which introduced the concept of plagiarism and established the main focus of the review. The rest of this article, which comprises seven main sections, is devoted to reviewing articles published on perceptions of plagiarism, attitudes toward plagiarism, and factors contributing to plagiarism. The first section starts with a review of studies that examined issues related to perceptions of plagiarism. Then, the review deals with studies that have examined attitudes toward plagiarism. Next, a section is given to focus on studies that have investigated factors contributing to plagiarism. After that, the relationship between factors contributing to plagiarism and both perceptions of plagiarism and attitudes toward plagiarism are explained based on the findings of previous studies. After that, a section is given to present the theoretical framework of factors contributing to plagiarism. This is followed by a section on methodological aspects used in the articles reviewed. Finally, this article ends with a section that includes some concluding remarks and suggestions for future research on perceptions of plagiarism, attitudes toward plagiarism, and factors contributing to plagiarism.

Perceptions of Plagiarism

Investigating students’ and academics’ perceptions of plagiarism includes studies in various geographical areas such as Australia, UK, USA and some Asian contexts (e.g., Ashworth et al. 1997; Ryan et al. 2009). In this section, these studies are reviewed based on the context in which the study was conducted.

Studies in the UK Context

In the UK context, the first study that aimed at examining students’ perceptions of plagiarism is Ashworth et al. (1997) in which 19 interviews were carried out with Master’s Degree students. They found that the students did not clearly differentiate between cheating and plagiarism. They also revealed that even though the students viewed plagiarism as a moral issue, the students thought that plagiarism is justifiable because it is supported by ‘values and ethics’ such as friendship, interpersonal trust and peer loyalty. Although Ashworth et al. (1997) claimed in the method section in their article that the study focused on students’ perceptions of both cheating and plagiarism, they clearly stated at the end of the introduction section in their article that the aim of their study was “to attend to the meaning of cheating within the student experience as closely and fully as possible” (p. 189). This, definitely, shows that the researchers used both cheating and plagiarism interchangeably.

In another study in the UK context, Flint et al. (2006) used interviews to examine 26 university lecturers’ perceptions of plagiarism and found that there were variations in the participants’ conceptualization of plagiarism. However, we need to consider that this study is one of the earlier studies and there are several studies that have focused on the conceptualization of plagiarism. Most of the participants in their study viewed plagiarism as copying verbatim, poor paraphrasing, or copying material from published sources without appropriate acknowledgement.

Studies in the Australian Context

A good number of studies have been carried out on issues related to perceptions of plagiarism in Australia. The early study of these is Brimble and Stevenson-Clarke (2005) who conducted a survey to explore students’ and academic staff’s perceptions of the seriousness of academic misconduct and the appropriate penalties for such misconduct. They found that the students exhibited higher tolerance for various forms of academic misconduct compared to the academic staff. With regard to the focus of this review article, Brimble and Stevenson-Clarke (2005) have revealed students’ confusion regarding plagiarism and referencing. Although Brimble and Stevenson-Clarke (2005) did not exclusively focus on students’ and academic staff’s perceptions of plagiarism, their findings clearly suggested the need for studies that explore what the term plagiarism refers to from the perspective of students in higher education contexts. Using a questionnaire, in the Australian context, Song-Turner (2008) investigated postgraduate international students’ knowledge and understanding of plagiarism and their perceptions of the reasons for plagiarism. In another study in the Australian context, Ryan et al. (2009) used a questionnaire to explore 823 pharmacy undergraduate and 74 postgraduate students’ perceptions of plagiarism and other cheating practices. Although Ryan et al. (2009) found that the majority of the students showed an awareness of the existence of policy regarding plagiarism and cheating practices in their university, there were no significant differences between undergraduate students and postgraduate students in the knowledge of policy of plagiarism. The study revealed a very surprising issue that the students’ attitudes did not show that they knew about various scenarios of plagiarism. Worse than that was that the students viewed what was an unacceptable convention in academic writing as acceptable.

Recently, in a large Australian dental school, Ford and Hughes (2012) focused on both students’ and staff members’ perceptions of plagiarism and found that the policy regarding plagiarism was inadequate as perceived by the students (undergraduates and postgraduates) and staff members. However, it should be taken into account that the survey used in Ford and Hughes (2012) was a part of a project on enhancing the participants’ knowledge of plagiarism. Thus, the participants’ perceptions of plagiarism might have been affected by what they learnt and what they were exposed to in the workshops which were included in the project. Furthermore, it is clear that their study was not fully directed toward understanding students’ and staff’s perceptions because the researchers claimed in their results that “plagiarism was not identified as a major issue” (p. 183). Ford and Hughes (2012, p. 183) also claimed that there was “a lack of confidence in [the] respondents’ understanding of exactly what constitutes plagiarism and their ability to avoid or detect it”. Thus, this finding confirmed what has been concluded by previous studies (e.g., Smith et al. 2007; Song-Turner 2008; Gullifer and Tyson 2010).

Based on the university policy regarding plagiarism, Sutherland-Smith (2005) in the Australian context, focused on eleven staff members’ perceptions of English for Academic Purposes (EAP) students’ plagiarism. Sutherland-Smith used both a questionnaire and interviews to collect data. She found that the eleven teachers in one EAP program viewed various issues related to plagiarism differently. An important finding in the study is that the teachers pointed out that a distinction should be made in plagiarism policies between intentional and unintentional plagiarism. It is worthy to mention that Sutherland-Smith (2005) has not reported all the issues that she included in the questionnaire used for data collection. In addition, the results she presented depended more on excerpts from the interviews without providing sufficient information on how she did the qualitative analysis.

Instead of a mere examination of students’ perceptions of plagiarism, Curtis et al. (2013), in a recent study in a university in Perth, Australia, have made a good shift in the lines of studies on plagiarism as they examined how intervention programs that aim at helping students to understand what constitutes plagiarism can improve students’ knowledge and understanding of plagiarism. They found that the online academic-integrity mastery module was successful as it increased university students’ understanding of plagiarism and their perceptions of plagiarism as a serious issue.

Studies in the USA Context

Similar to the studies that have used university policy (Ryan et al. 2009; Sutherland-Smith 2005) to construct questionnaires or scenarios of plagiarism cases, in the City University of New York, Marcus and Beck (2011) used Queensborough Community College Academic Integrity Policy to construct 12 statements in a questionnaire which was used to obtain lecturers’ perceptions of plagiarism. Marcus and Beck found that there was inconsistency among lecturers’ perceptions of what constitutes plagiarism. They surprisingly noticed that there is a need for developing the lecturers’ knowledge regarding university policy of academic integrity and cases of misconduct. However, it should be taken into account that Marcus and Beck’s study was carried out in an L1 context in which there are well-established programs for academic integrity and misconduct including polices on plagiarism. This case cannot be applied to developing universities in which it is perhaps difficult to find programs on academic integrity.

Unlike the previous studies that have focused on perceptions of plagiarism using surveys in the Australian context, Gullifer and Tyson (2010) examined students’ perceptions of plagiarism by employing a focus group interview. They collected data through interviewing 41 students (25 women and 16 men), who were either in their first or third year of study and were divided into seven focus groups. The central themes of the focus group interviews were the conceptualization of plagiarism (how the students define plagiarism), the causes of plagiarism, students’ judgments of the seriousness of plagiarism, and the chances of being caught. The findings of Gullifer and Tyson have confirmed those of the previous studies in terms of students’ misunderstanding of the concept of plagiarism as some of the students were confused regarding what constitutes plagiarism. For example, similar to the findings of Ashworth et al. (1997), the students in Gullifer and Tyson (2010) expressed their fear of being caught for unintentional plagiarism. The student participants also pointed out the severity of sanctions and the consequences of plagiarism.

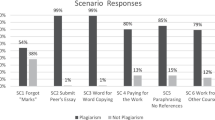

In another study in the USA context, Robinson-Zañartu et al. (2005) designed a survey that included ten case scenarios of academic misconduct. For each case, the faculty members were asked to (1) judge whether each case was a case of plagiarism, (2) select a course of action, (3) select a report action to be made, and (4) select a university sanction to be warranted. It is noteworthy to know that complexity of data analysis and the design of the study made it difficult to generalize the findings of the study. Furthermore, the researchers have not provided the readers with specific conclusions of their study. In addition to these two issues, the reliability of the case scenarios was not described because the ten cases do not include all possible cases of academic misconduct. However, they found that faculty members perceived the issue of plagiarism as a severe condition that deserves some kind of course-related actions. In another study that shifted the focus to be on the instructors, in the US context, Bennett et al. (2011) continued the tradition and investigated instructors’ perceptions of what constitutes plagiarism, their experience with plagiarism, and their expected responses to the cases they could detect. In fact, the survey used in Bennett et al. (2011) also used scenarios or cases of plagiarism to obtain the instructors’ perceptions of plagiarism and they adopted recycling as a form of plagiarism. This methodological procedure concerning the use of scenarios can be found to be almost similar to previous studies (e.g., Ryan et al. 2009) in which scenarios of plagiarism were given to students to gauge their perceptions of plagiarism. This study has gained a further step in examining plagiarism when it used regression analysis to examine the relationship between instructors’ perceptions of plagiarism and instructors’ demographic variables. Bennett et al. (2011) found that most of the instructors considered that claiming works of others as their own is a definite form of plagiarism. The study also revealed that there is no significant relationship between plagiarism and respondents’ demographic variables.

In a recent study in the US context, Leonard et al. (2015) examined postgraduate students’ perceptions of the definition and seriousness of plagiarism. They administered a questionnaire that included open-ended questions to 45,500 science, technology, engineering, and mathematics students from University of Florida. The students varied to be domestic and international. The study revealed that over half of the respondents were not certain about the level of academic dishonesty in their university.

Studies in the New Zealand Context

In New Zealand, Marshall and Garry (2006) explored how plagiarism and copyright were perceived by two groups of students, non-English speaking and English speaking students. They constructed both a questionnaire and scenarios, and asked the students to answer using yes/no options and a scale of 0 to 5 for the seriousness of the behaviour presented. While the questionnaire included 14 items, the scenarios included 15. The results of the study show that the concept of plagiarism was not clear for the students, especially non-English speaking students. Consequently, this reveals that these students might have plagiarized unintentionally. Although the study has given emphasis on the students’ perceptions of plagiarism, the fact that the researchers constructed the questionnaire and the scenarios themselves may raise questions regarding the reliability and validity of the items included in the questionnaire and the scenarios. In addition to this, the researchers did not report the reliability co-efficient of the items in the instruments used for data collection. In another study in New Zealand, Kuntz and Butler (2014) have contributed to the studies focusing on perceptions of plagiarism through examining the predictors of students’ attitudes toward the acceptability of two forms of misconduct, cheating and plagiarism. Kuntz and Butler used regression analysis and some advanced statistical tests to analyse the data and found that gender, perpetrator sensitivity, and understanding of university policy appeared to be the major positive predictors of students’ attitudes toward academic dishonesty with regard to plagiarism and cheating.

Studies in L2 Contexts

Apart from studies conducted in L1 context such as in the USA, the UK, Australia, and New Zealand, very few studies have been carried out in contexts in which English is a second language (L2). This has been pointed out in several research articles (refer to Chien 2014). For example, in Pakistan, studies were conducted by Shirazi et al. (2010) and Murtaza et al. (2013) to examine students’ perceptions of plagiarism. Both studies employed a brief questionnaire which included some items to obtain students’ knowledge of plagiarism. The study of Shirazi et al. (2010) is somehow similar to the studies that used scenarios to obtain students’ knowledge on cases of plagiarism. While Murtaza et al. (2013) found that most of the students were unaware of the Higher Education Commission (HEC) policy of plagiarism, Shirazi et al. (2010) showed that most of the respondents did not have adequate and proper knowledge on what is involved in plagiarism. The findings of these two studies may give an indication on the prevalence of plagiarism in the Pakistani context, and the dire need for giving proper explanation to the students on what plagiarism is. Although Murtaza et al. (2013) collected huge data (25,742 students from 6 academic disciplines of 35 different universities), they did not use this to perform an in-depth analysis. Furthermore, they only relied on six items to obtain students’ attitudes toward plagiarism. Even these six items were mostly related to a few forms of plagiarism, not positive and negative attitudes toward plagiarism.

The Chinese context has witnessed and received much attention from researchers working on issues related to plagiarism. For example, Mu (2010) examined students’ perceptions of plagiarism by employing a questionnaire and interviews. However, it is worthy to note that Mu (2010) did not clearly give full attention to the issue of plagiarism because as claimed by Mu the study examined writing practices of Chinese students including how they used sources in their writing and the factors affecting their writing practices. For data collection, the students were asked to submit a term paper of about 3000 words at the end of the course. Pertaining to plagiarism, the students in the study reported that they used summarizing and paraphrasing in their papers to avoid plagiarism. However, the analysis of data revealed that the students were not aware of the severity of their academic misconduct which included borrowing others’ writing without respective referencing or acknowledgement, using other writers’ ideas as their own, and downloading papers from the Internet and presenting them as their own. Similar to the results reported in previous studies, Mu (2010) has assured that the students were not aware of what constitutes plagiarism.

Taking into consideration that few studies have examined teachers’ perceptions of plagiarism, especially in L2 writing context, Chien (2014) employed in-depth, semi-structured individual interviews with each of 23 Taiwanese writing teachers to examine how they perceive plagiarism. Chien (2014) found that these Taiwanese teachers considered plagiarism to be the unauthorized or unacknowledged use of another person’s ideas, failure to document source material, or inappropriate citation. As found by some studies, the findings of Chien (2014) confirmed that, as perceived by the respondents, student plagiarism can be due to their lack of experience and knowledge on appropriate citation of sources. Accordingly, the teachers in the study revealed that the use of plagiarism detection software can help in reducing the cases of plagiarism in the Taiwanese context. We need to consider here that it is difficult to generalize the findings of the study because it depended only on a qualitative approach through carrying out interviews with 23 teachers. There are two recent studies in the Taiwanese context: Chen and Chou (2016) and Chien (2016). Chen and Chou (2016) compared students’ and faculty members’ perceptions of plagiarism. They also examined causes of plagiarism. The results revealed that there were some significant differences regarding the reasons held by faculty members and students on student plagiarism. Both faculty members and students reported that the top reason for students to plagiarize is that they were not interested in their subjects. Regarding the perceptions of plagiarism, the faculty members considered plagiarism as more serious misconduct than the students did. While the study revealed that both faculty members and students had similar understanding of plagiarism, students had different criteria regarding copying other’s texts. Chien (2016) examined Taiwanese students’ perception of plagiarism and how they viewed plagiarism in relation to culture. The methodology was slightly different than other studies because Chien (2016) complemented data collection with a writing exercise to identify students’ abilities to distinguish between acceptable and unacceptable source appropriation. The aim of the writing exercise was to help researchers to determine students’ ability to identify and recognize plagiarism. The students were asked to read an original passage several times and understand it fully. After that they were directed to check proper citation and its similarity to the original passage. The study revealed most of the students reported that they plagiarized for two major reasons: (1) to achieve high grades and (2) they were not motivated to create their own works and did not want to spend much time on the assignment. The study also revealed an important finding in that most of the students were not able to recognize plagiarism as reported in the writing exercise and interviews.

Focusing on Chinese teachers’ knowledge of plagiarism, Lei and Hu (2015) found that how Chinese teachers perceived plagiarism differed clearly based on whether a teacher has an overseas experience or not. In Hu and Lei (2015), the focus was on Chinese undergraduate students’ perceptions of plagiarism and the relationship between these perceptions and other factors which are gender, disciplinary background, and length of study in university. Hu and Lei (2015) found that Chinese students’ perception of plagiarism was shaped by gender and other disciplinary factors.

A very recent study that examined perceptions of plagiarism was cross-sectional research which was carried out by Kayaoğlu et al. (2015) to investigate the differences in tendency to conduct academic theft among three groups, 106 Turkish, 83 Georgian, and 72 German students. They found that the degree of tolerance for misconduct behaviours was low in all three groups of students. In addition, the study showed that the main reasons for plagiarism were busy schedule, easy access to academic sources, thinking of not being caught, homework load, unclear assignment, and lack of knowledge on how to cite and use textual appropriation successfully. Another important finding of the study is that while the German students were successful at identifying plagiarism in sample academic texts, their Turkish and Georgian counterparts were not.

Attitudes toward Plagiarism

A line of research on plagiarism has explored students’ and staff’s attitudes toward plagiarism. One of the early studies that examined students’ attitudes toward academic misconduct including plagiarism is Ashworth et al. (1997) who examined cheating and plagiarism from the perspective of students in higher education. To examine these issues, they conducted nineteen interviews with students. They found out that students were not certain about what should be assigned under plagiarism. Further, they reported that students showed their fear of committing plagiarism unintentionally because they did not have adequate guidelines regarding how to cite other texts and how to do referencing. The students also showed anxiety over how plagiarism is identified by academic staff. In a university in the UK, Pickard (2006) used a mixed method to examine staff’s and students’ understanding of plagiarism and their perceptions of the extent of plagiarism. Pickard also explored the strategies used by staff to minimize and tackle plagiarism. Pickard found that 24% of the staff respondents considered that plagiarism might have affected 10% of the students or less. On the other hand, 15% considered that plagiarism might have affected 41% – 50% of students. She also found that the greatest response (20%) was related to the category that estimated 21% – 30% of students may plagiarize. A very important finding of Pickard is that 72% of the staff detected plagiarism in their previous academic year. The findings of Pickard have attracted researchers’ attention to the great prevalence of plagiarism and have highlighted the need to understand more on how academic staff and students perceive plagiarism. Regarding this, there is a need for more studies that should focus on the effect of programs that should be developed and employed to minimize plagiarism.

One of the influential studies that has given particular and exclusive focus on attitudes toward plagiarism is Pupovac et al. (2010) in which the participants were 146 first year students from the Faculty of Pharmacy and Medical Biochemistry at University of Zagreb, Croatia. Pupovac et al. (2010) employed Attitudes Toward Plagiarism (ATP) questionnaire and found moderate attitude toward plagiarism among Croatian pharmacy students. Their study reported that the average scores were moderate for all three attitudinal factors: positive attitudes, negative attitudes, and subjective norms.

Claiming that student plagiarism is a growing problem within Australian universities, Ehrich et al. (2014) have used Harris’s (2001) Plagiarism Attitude Scale to contrast 131 Australian and 173 Chinese undergraduate university students’ attitudes toward plagiarism. Using correlational analysis, they also examined the relationship between pressure (pressure on a student to achieve high grades) and plagiarism attitudes. They found that Australian students had less acceptance of using others’ work compared to the Chinese group. Additionally, the study showed that the severity of attitudes toward plagiarism was higher among the Australian students than that of the Chinese students.

In L2 context, very few studies have been carried out on the issues of plagiarism. In the Malaysian context, two studies (Smith et al. 2007; Quah et al. 2012) were conducted on plagiarism. Smith et al. (2007) focused on the incidence of plagiarism among accounting undergraduates in a Malaysian university. Employing a survey which was administered to 286 students, they examined factors that have influenced undergraduate students’ plagiarism. They found that some of the variables that were significantly associated with plagiarism activity among a group of Malaysian undergraduate accounting students were pressure, institution, personal attitudes, lack of awareness, lack of competence, and the availability of Internet facilities. However, Smith et al. (2007) indicated that the hypothesis testing in their study did not support a direct link between all of these factors and the self-reported incidence of plagiarism. Quah et al. (2012) investigated the relationship between attitudes toward plagiarism and ethical idealism, ethical relativism, and Machiavellianism. They also included religious orientation as a moderator variable. The study revealed that there is a positive relationship between both ethical relativism and Machiavellianism in relation to students’ attitudes toward plagiarism. In addition, the study showed that there is no clear direct effect of religious orientation on students’ attitudes toward plagiarism.

In the Israeli context, Reingold and Baratz (2011) investigated 200 Israeli teacher education students’ attitudes toward different aspects of plagiarism. However, what was obvious was that the study examined the attitudes toward only three instances or forms of plagiarism, i.e., copying from a book, copying from a colleague, and copying from the Internet. The study revealed that most of the respondents considered various instances of copying as a violation of academic norms and copyright. In this study, the use of the terms was not clear as the researchers used the two terms cheating and plagiarism interchangeably. In addition to this, they used perceptions, opinions, and attitudes to refer to the focus of the study. Thus, it was not clear whether the study focused on perceptions or attitudes. In Iran, using a Persian version of attitudes toward plagiarism (ATP) questionnaire (Mavrinac et al. 2010), Ghajarzadeh et al. (2012) assessed 120 medical faculty members’ attitudes toward plagiarism. They found that medical faculty members answered less correctly to negative attitude toward plagiarism questions in comparison with the other two factors. Yet, these researchers did not clearly describe their results.

In another recent study in the Chinese context, Hu and Lei (2012) examined how Chinese university students detected two forms of plagiarism (unacknowledged copying and acknowledged paraphrasing) in English writing samples, and how students perceived these two forms of plagiarism. In addition, they examined how some factors were related to the students’ ability to recognize the two plagiarism forms. The findings of the study revealed that most of the students had problems in recognizing the two forms of plagiarism, and the attitudes the students revealed reflect that plagiarism should be punishable. Regarding the factors affecting successful detection of plagiarism, the study showed that discipline, self-reported competence in referencing, and knowledge of subtle plagiarism are significant predictors. Considering the objectives of the study, it can be found that the study is more on detection of plagiarism rather than understanding students’ attitudes toward plagiarism. Furthermore, by focusing on the writing practices in the second objective, the study overlooked attitudes toward plagiarism. Another issue that can be raised as a shortcoming of the study is that it used an instrument in which undergraduate Chinese students were asked to judge the quality of the passage which is questionable in an L2 context due to inadequate knowledge of the learners. Even lecturers and staff members may find it difficult to detect cases of plagiarism unless it is a case of taking the ownership.

In a recent study in India, Gomez et al. (2014) examined attitudes toward plagiarism of postgraduate students and faculty members of Bapuji Dental College and Hospital. Their study confirmed that postgraduate students and faculty members in L2 contexts may not have sufficient knowledge on what constitutes plagiarism. Although Gomez et al. (2014) used a 29-item questionnaire that focused on positive and negative attitudes, and subjective norms, they did not provide an in-depth analysis. Rather, they only reported percentages of the students’ responses.

Some other L2 contexts such as Malaysian, Taiwanese, Chinese, Pakistani, and Iranian have witnessed an increase in the number of studies that have examined students’ perceptions of plagiarism and attitudes toward plagiarism. Amiri and Razmjoo (2016) employed semi-structured interviews to examine three topics: (1) EFL undergraduate students’ perceptions of plagiarism, (2) the extent to which they are informed about it, and (3) the reasons triggering them to plagiarize. The responses revealed shallow understanding of plagiarism in its various forms. Their study revealed that the participants did not have an agreed-upon definition of plagiarism. Rather, their conceptualization of plagiarism was superficial. For example, the participants did not differentiate between various forms of plagiarism such as copying from others. Furthermore, some students attributed their unintentional plagiarism to their lack of awareness of plagiarism.

Factors Contributing to Plagiarism

In our review of studies on perceptions of and attitudes towards plagiarism, one of the themes identified is factors contributing to plagiarism. Given the apparent high levels of plagiarism, and given that it is a highly complex phenomenon, this section reviews previous studies that have identified these factors. Table 2 provides a classification and a list of factors contributing to plagiarism that have been reported in previous studies. At the end of this section, we identify factors that can be addressed by educational institutions to reduce plagiarism.

Research on plagiarism has identified a wide array of factors that contribute to the rate of plagiarism. In this section, a review of these studies focuses on the factors that can be addressed by educational institutions in order to reduce plagiarism. Factors that have been identified as contributors to plagiarism are many. They include lack of understanding of the conceptualization of plagiarism (Park 2003; Marshall and Garry 2005; Powell 2012), previous learning experiences (Powell 2012), the use of the Internet and other digital technologies (Sisti 2007), perceived seriousness (Park 2003), and lack of consequences (Barnett and Cox 2005; Remler and Pema 2009). Various empirical studies have reported factors that are associated with various types of plagiarism such as unintentional plagiarism and intentional plagiarism which is described as conscious plagiarism of others’ academic work. It has been argued in these studies that students’ use others’ texts with a denial of responsibility because they perceive the subject matter of plagiarism as secondary or not very relevant to the curriculum. Another reason the students revealed is their lecturers’ neutral behaviour towards plagiarists and their perception of plagiarism itself as a minor issue (Ashworth et al. 1997). This is also stressed by Phillips and Horton (2000) who found out that students may realise that their teachers do not regard plagiarism as a matter of academic misconduct.

Other factors that have their influence on the increase of plagiarism are conventional teaching methods, difficulty of academic tasks given to students, excessive demands for assignments, educational framework (teaching strategies and methodology), poor assessment methods, and students’ feelings that assignments are boring (Comas-Forgas and Sureda-Negre 2010; Akbulut et al. 2008; Koul et al. 2009; Devlin and Gray 2007; Alam 2004; Sterngold 2004; Phillips and Horton 2000). These are some of the several factors that have been reported as explanatory factors of plagiarism. Amiri and Razmjoo (2016) in Iran and Comas-Forgas and Sureda-Negre (2010) in Spain have provided a good review of factors that can contribute to plagiarism. Carroll (2002) believed that it is poor assessment processes that breed misconduct and plagiarism in academia.

Park (2003) pointed out that a genuine lack of understanding of plagiarism is one of the motives because this can lead individuals (students and academics) to commit unintentional plagiarism. This has been confirmed by Marshall and Garry (2005) who reported that “students have a poor understanding of the concept of plagiarism and the many different ways in which they can plagiarise” (p. 464). Marshall and Garry have not only identified lack of understanding of what plagiarism is, but they also identified students’ ways of unintentional plagiarism. Powell (2012) has attributed plagiarism to (1) different previous learning experiences which students bring along with them to higher education institutions, (2) misunderstanding of the meaning of plagiarism, and (3) unclear conceptualization of the significance of plagiarism in the specific learning institution in which it is being assessed. Other researchers have reported that the Internet has contributed to plagiarism because it is convenient and makes content that students need available, which gives students opportunities to plagiarize easily (Marshall and Garry 2005; Park 2003). Regarding perceived seriousness of plagiarism, previous research has revealed that students consider plagiarism as a minor offence and this can encourage students to plagiarize regardless of their personal values (Park 2003).

Comas-Forgas and Sureda-Negre (2010) argued that some factors contributing to plagiarism can be related to plagiarists themselves (students and academics). Students’ poor time management and their desire for better marks in assignments can motivate them to plagiarize (Franklyn-Stokes and Newstead 1995). Student plagiarism can be attributed to their laziness, poor time management and their dependence on materials that can be accessed easily through the Internet. Furthermore, Devlin and Gray (2007) and Akbulut et al. (2008) reported that factors that encourage students to plagiarize are a lack of time, poor time management, desire for good grades, laziness, and the ease of using materials from the Internet through copy-and-paste technique. Some researchers argued that students’ poor academic writing skills can be a factor that leads them to plagiarize (Pecorari and Petrić 2014). Due to their lack of academic writing skills, students may use patchwriting and appropriation as developmental strategies for academic writing, and thus inadvertently committing plagiarism.

Some studies have reported that factors associated with peers can be critical factors that may contribute to plagiarism. For example, Ashworth et al. (1997) reported that students may justify this by claiming that plagiarism is supported by values and ethics such as friendship, interpersonal trust and peer loyalty. However, this peer loyalty has been condemned by some students in Ashworth et al. (1997) as they regarded such students/classmates as cheaters and plagiarists. On the other hand, some studies have reported that peer pressure can lead students to cheat or plagiarize. In such situations, the decision to act contrary to the principles of academic integrity is evoked by the pressure from other course-mates. Students believe that their peers cheat without being caught and this may lead to peer pressure to cheat which, in turn, can lead to plagiarism (Rettinger and Kramer 2009).

Among the factors contributing to plagiarism, some factors can be addressed by educational institutions to reduce plagiarism. One of the factors that should be addressed by educational institutions to decrease and discourage plagiarism among students is the provision of clear and concise policy regarding all types of academic misconduct behaviours and the consequences of committing one of such behaviours. This policy should include a concrete definition of plagiarism so that students and academics can be aware of the meanings of misconduct behaviours such as cheating and plagiarism (intentional and unintentional). Regarding this, Marshall and Garry (2005) suggested that education programs should include formal definitions of plagiarism with the provision of specific examples that must illustrate the range of activities that are not allowed to be carried out in order to avoid academic misconduct. Furthermore, instead of placing emphasis on plagiarism as a criminal act, educational institutions should teach plagiarism properly in order to guide students and academics on how to avoid plagiarism (Roberts 2007). Furthermore, Weber-Wulff (2014) argued that students should be taught about plagiarism in secondary schools. In such a case, when students join university they would have a clear idea about what plagiarism means. Furthermore, the use of detection software programs to reduce plagiarism has been suggested. When students knew that their work would be checked using the plagiarism detection software programs such as Turnitin, the overall plagiarism rate decreased by 4.3%, thus proving that such software works as a deterrent to curb student plagiarism (Batane 2010). Similar to what has been reported concerning students’ knowledge of plagiarism, research has revealed that some academics lack proper knowledge of plagiarism, with particularly divergent opinions on self-plagiarism (Roberts 2007). Therefore, programs to train academics and students in educational institutions should consider when and how to teach different aspects of plagiarism avoidance (Roberts 2007).

To help students avoid plagiarism, it has been suggested that they can be encouraged to understand the concept of plagiarism and the practical implications in practice. Furthermore, understanding citation and referencing conventions may be useful for students to reduce plagiarism. Additionally, institutions of higher education must address students’ limited academic skills (critical analysis, writing effectively, thesis construction, and paraphrasing) and help students to improve these aspects (Gullifer and Tyson 2014). Institutions of higher education can also help students to improve their academic writing skills so that they can enhance their use of other texts in their current written pieces.

Relationship between Factors and both Perceptions and Attitudes

This section discusses two critical issues: (1) perceptions and attitudes reviewed in the literature which potentially contribute to plagiarism and (2) factors that have led to these perceptions and attitudes. Some perceptions of plagiarism and attitudes toward plagiarism can be associated with student plagiarism. One of the perceptions that have led students to plagiarize is their perception of plagiarism as a minor issue that does not deserve penalty or an action from the side of the educational institutions. Research has reported that some students’ perceived seriousness of plagiarism is one of the perceptions that may have effects on student plagiarism. Regarding this, it has been reported that students’ underestimation of plagiarism and their perception of plagiarism as a minor offence have yielded an increase in the rate of plagiarism (Maxwell et al. 2008; Ashworth et al. 1997). Furthermore, Lim and See (2001) found out that a large number of students had weak negative attitudes toward committing plagiarism and considered plagiarism a less serious activity. Thus, because there is no penalty for those who plagiarize, students take it for granted that they are free to use texts from other scholarly articles, books and websites and use such materials in their own texts without acknowledging the sources (Amiri and Razmjoo 2016). Another important perception that can contribute to the increase of plagiarism rate is students’ perception of the concept of plagiarism. Regarding this, Amiri and Razmjoo (2016) found out that there is a lack of understanding of the concept of plagiarism where the students reported that they did not know that copying is plagiarism. This type of perception can be a factor contributing to the increase in the rate of plagiarism.

One of the perceptions that may contribute to plagiarism is students’ perceptions of the free use of content obtained through the search engines through using the Internet. The factor that has led to this perception is lack of restrictions on the use of the Internet by students when doing their assignments and other oral and written activities. Consequently, students may think that content and materials from the Internet are free for them to use without restrictions (Gomez 2012; Park 2003). Therefore, students may mix between the use of materials from the Internet for academic work and the ownership of these materials (Gomez 2012). Similarly, Kutz et al. (2011) argued that the availability of free materials on the Internet, with no authors for some materials, may encourage students to use them as their own, leading to an increase in the plagiarism rate.

Policies regarding plagiarism and students’ perceptions of such policies can also be a factor that may lead students to think that plagiarism is a permissible activity. Although conflicting research results regarding plagiarism have been reported in the literature, the plagiarism rate and attitudes towards it seem to be, most probably, influenced by policies imposed by educational institutions. In respect of this, Gullifer and Tyson (2014) pointed out that “the consequences of not reading the policy may contribute to widespread ignorance of what behaviours constitute plagiarism” (p. 3). Moreover, when students perceive that legal procedures outlawing plagiarism are not given properly or are not followed, they tend to plagiarize more.

Theoretical Framework of Factors Contributing to Plagiarism

The previous four sections reviewed studies that examined (1) perceptions of plagiarism, (2) attitudes toward plagiarism, (3) factors contributing to plagiarism, and (4) the relationship between factors contributing to plagiarism and both perceptions of plagiarism and attitudes toward plagiarism. As it could be concluded from the previous sections, several factors potentially affect perceptions and attitudes and these factors can be helpful in understanding why plagiarism occurs so that learning institutions can establish strategies which are more likely to impact plagiarism behaviour. Thus, this current section presents a theoretical framework that shows how various factors contributing to plagiarism are potentially related.

There is no adequate attempt to provide a comprehensive classification of factors contributing to plagiarism. Previous studies have focused on factors explaining the causes of the occurrence of plagiarism. Regarding this issue, few journal articles have contributed to research that offers an extensive analysis of studies that have dealt with factors contributing to plagiarism. These journal articles are authored by Park (2003), Bertram-Gallant (2008), Comas-Forgas and Sureda-Negre (2010), and Amiri and Razmjoo (2016).

In these articles, the scholars attempted to make an in-depth analysis of the existing literature in the field to provide some lists of factors that can explain academic plagiarism among students. Bertram-Gallant (2008) systematized the literature around the causes of academic dishonesty and plagiarism as internal or personal, organizational, institutional and social. Comas-Forgas and Sureda-Negre (2010) presented a detailed description of the major causes of academic plagiarism among university students. Their detailed description was based on what previous studies have focused on. These studies revealed that there are no clear-cut criteria for classification of factors explaining plagiarism. Comas-Forgas and Sureda-Negre (2010) have presented a good classification of these factors as they divided factors contributing to plagiarism into three types: (1) factors related to the teaching staff and methods of teaching, (2) factors related to behaviours and beliefs of students, and (3) factors related to ease of access of information on the Internet. However, their taxonomy can account for other factors such as factors associated with parents, peers, and institutional factors. In a recent study, Amiri and Razmjoo (2016) reviewed previous studies on plagiarism and suggested that factors contributing to plagiarism can be divided into two main broad categories: major factors and minor factors. In their taxonomy, Amiri and Razmjoo (2016) argued that other factors can be grouped under these two main categories. Under major factors, they grouped individual, academic, technological, and cultural factors. Under minor factors, they grouped curriculum, parental, and personal factors. It can be recognized that factors such as peer pressure cannot be included in this taxonomy. They argued that this classification was based on the frequency of the reported factors in previous studies. Nevertheless, these taxonomies proposed by Park (2003), Bertram-Gallant (2008), Comas-Forgas and Sureda-Negre (2010), and Amiri and Razmjoo (2016) have not shown how these factors are interrelated.

Thus, taking into account the shortcomings of the aforementioned taxonomies, in this review article, we present a framework of factors contributing to plagiarism. This framework, as presented in Fig. 1 and Table 2, can most probably account for all factors contributing to plagiarism. As shown in Fig. 1, factors contributing to plagiarism can be divided into five types: institutional, academic, external, personal, and technological. Institutional factors are factors that are related to the policy of plagiarism, teaching and curriculum. Academic factors refer to students’ abilities in performing academic tasks. External factors are those that stem from external sources such as parents, relatives, friends, and peers. Personal factors refer to individual factors such as perceptions and beliefs, and they include assumptions and beliefs that students hold to be true regarding concepts, events, people, and subject-matters. Lastly, technological factors are associated with the availability of technological sources that can provide academic content. As shown in Fig. 1, all these five factors are important and critical as they interact with each other to contribute to plagiarism.

As shown in Fig. 1, although all the categories of factors are critical and they can contribute to the act of plagiarism, we argue here that external factors (such as peer behaviours and parental pressure) are associated with personal characteristics (such as students’ laziness and poor time management). Furthermore, the institutional factors (such as unclear policy regarding academic misconduct) are associated with academic factors (such as students’ poor writing skills). That is to say, personal, technological and academic factors have a very direct relationship with student plagiarism. On the other hand, external and institutional factors have an indirect effect on student plagiarism.

Methodological Aspects in Previous Studies

Most of the studies reviewed here in this article have used a survey method. This method is found to be most convenient by researchers because they can obtain sufficient information from a wide range of distributed population, and they can also obtain valid responses when dealing with sensitive subject-matters (Fowler 2013). However, very few studies have relied on either an exclusively qualitative design or a mixed-method design (e.g., Ashworth et al. 1997; Sutherland-Smith 2005; Gullifer and Tyson 2010).

Studies that have examined students’ perceptions of plagiarism have mostly relied on scenarios of plagiarism cases in which the students were requested to judge such cases (e.g. Robinson-Zañartu et al. 2005; Marshall and Garry 2006). In addition, what can be noticed in the studies reviewed in this article is that there has been a lack of studies that examine the relationship between variables or factors contributing to academic misconduct behaviours. In other words, except for Quah et al. (2012) who used regression analysis to find out how attitudes toward plagiarism are affected by some factors in the context, the studies reviewed in this article (those selected in Stage Five as shown in Table 1) have not given adequate attention to the effects of attitudes toward plagiarism on students’ perceptions of subjective norms or the effects of some variables such as gender, understanding of university policy, disciplinary background, access to Internet facilities, personal attitudes, lack of competence, lack of awareness, and pressure. In other words, it should be highlighted that research articles that have focused on perceptions of/attitudes toward plagiarism have not given proper attention to the relationship between perceptions of/attitudes toward plagiarism and other demographic and sociocultural variables. This was noticed by Scollon (1995) who stated that “the concept of plagiarism is fully embedded within a social, political, and cultural matrix that cannot be meaningfully separated from its interpretation” (p. 23). Furthermore, this review has obviously shown that studies on perceptions of and attitudes toward plagiarism have not investigated how perceptions of various forms of plagiarism may affect positive and negative attitudes toward plagiarism. For example, Ashworth et al. (1997) did not fully focus on M.A students’ perceptions of plagiarism as the results of their study reflect this. The themes that emerged from the analysis of the interviews they conducted are meanings of cheating and plagiarism as moral issues, personal reactions to cheating, and the institution’s role in the causes of cheating. Another evidence of this is that the researchers in this review have found that the meaning of plagiarism is hazy. Such a lack of full focus on the students’ perceptions of plagiarism can be contributed to the fact that when a study was carried out, there was no clear and concise definition of the concept of plagiarism. As a result of this, it was found that studies in 2000s have focused on plagiarism from the perspective of policies of universities (refer to the previous sections in this article).

Taking into account the analysis techniques used in the studies reviewed, it can be found that only a few studies have depended on inferential and advanced analytic tools to examine how various factors and variables affect and interact with the students’ perceptions of plagiarism and attitudes toward plagiarism. One of these studies is Quah et al. (2012) in which regression analysis was used. Bennett et al. (2011) also used regression analysis to examine the relationship between instructors’ perceptions of plagiarism and instructors’ demographic variables.

Concluding Remarks

Given its inherited multifaceted nature, different perspectives have been the focus of studies on plagiarism. Most of the studies reviewed here have obviously revealed that there are no consistencies regarding what constitutes plagiarism and how it should be avoided. This has been also argued by Ehrich et al. (2014) who have noticed the complexity of plagiarism and the difficulty of finding a proper explanation of individuals’ engagement in plagiarism. Furthermore, some of the studies reviewed in this article have revealed some discrepancies regarding the similarity and differences between staff’s and students’ attitudes toward plagiarism. While some studies have revealed that staff’s and students’ attitudes toward plagiarism are not similar due to various sociocultural, institutional, and personal factors, Ford and Hughes (2012) found that both students and staff perceived the policy regarding plagiarism as inadequate. Similarly, Gomez et al. (2014) found that both students and faculty members may not have sufficient knowledge of what constitutes plagiarism. These issues establish an urgent need for more studies that adopt an in-depth analysis and an advanced statistical analysis that can reveal how various contextual factors may contribute to shaping individuals’ positive and negative attitudes toward plagiarism. In relation to perceptions of and attitudes toward plagiarism, this review of previous studies has shown that there is great interest in researching plagiarism. This review has also shown that the prevalence of plagiarism is a serious issue because the prevalence of plagiarism reported in research is probably less than what is there in the academic sphere. For example, Yeo (2007) stated that “the prevalence of plagiarism is likely to be greater than what is reported” (p. 201). The early studies on the prevalence of plagiarism have not given a clear answer to the extent to which plagiarism prevailed because such studies have not separated plagiarism from academic cheating and dishonesty (Yeo 2007).

Concerning the tremendous number of studies on plagiarism, the researchers attempted in this review to focus on the issues of perception of plagiarism, attitudes toward plagiarism, and factors contributing to plagiarism. These three are deemed important central themes in the previous studies on plagiarism. Although studies that have focused on university students’ and staff’s perceptions of plagiarism and attitudes toward plagiarism are several, most of these studies have examined these issues in the Western context. In other words, the Asian, Asia-pacific and the Middle Eastern contexts have suffered a lack of studies on perceptions of plagiarism and attitudes toward plagiarism. Specifically, very few studies on students’ perceptions of plagiarism have been carried out in these contexts. Furthermore, it can be noticed that most of the studies reviewed in this article employed descriptive research designs because they merely described the variables in order to answer the research questions and did not intend to establish a cause-effect relationship among variables.

This review article has shown that very few studies (i.e., Ehrich et al. 2014; Hu and Lei 2015; Chen and Chou 2016) have analysed the relationship between the perceptions of plagiarism and other contextual, sociocultural and institutional variables, or the relationship between attitudes toward plagiarism and students’ perceptions of various forms of plagiarism. These studies have used some inferential statistical tests to analyse the data and revealed interesting findings. However, each one of the studies focused on a specific variable. While Hu and Lei (2015) dealt with the effect of discipline, year of study, and gender on knowledge of plagiarism, Ehrich et al. (2014) investigated the relationship between pressure felt at university (pressure) and severity of attitude toward plagiarism (plagiarism attitudes). Chen and Chou (2016) dealt with perception and three other background characteristics: gender, age and academic level. An important conclusion from these studies is that there is inconsistency among researchers regarding the relationship between factors in the context and other demographic variables and perceptions of plagiarism and/or attitudes toward plagiarism. For example, Ehrich et al. (2014) found that there was a significant correlation between severity of students’ attitudes toward plagiarism and the pressure they placed on themselves. Using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) (the statistical procedure used for comparing or contrasting means from samples), Hu and Lei (2015) found that there was no significant effect of gender on perceptions of plagiarism. Hu and Lei revealed a significant main effect of discipline on knowledge about blatant plagiarism and subtle plagiarism. Another factor that has been noted to be considered is culture. Regarding this, Flowerdew and Li (2007) pointed out that “there is at the same time a need to guard against essentializing culturally conditioned views of plagiarism” (p. 166). Although these studies have provided some insights on the relationship between some factors and plagiarism, it is commonly believed that “plagiarism is a highly complex phenomenon and, as such, it is likely that there is no single explanation for why individuals engage in plagiarist behaviors” (Ehrich et al. 2014, p. 2). Chen and Chou (2016) used MANOVA to analyze students’ and faculty members’ background characteristics and perception of plagiarism. They found that faculty members’ and students’ background characteristics (gender, grade levels, and academic discipline) were associated with their perception of plagiarism.