Abstract

The present study utilized a sample of 962 individuals in dating, cohabiting, and marital relationships to examine how beliefs about marriage salience and permanence were associated with individual relationship functioning. While previous studies have suggested that marital beliefs are associated with individual decision making, few studies have examined how such beliefs might be associated with differing individual relational behavior and perceptions. The present study explored how marital beliefs may be associated with perceptions of relationship satisfaction and stability through the indirect pathways of individual commitment and relational effort. Results suggested that marital beliefs were significantly associated with perceptions of relational well-being in which more positive beliefs about marriage were indirectly associated with perceptions of more satisfaction and more stability. Multi-group comparisons suggested that these associations held for those in all types of relationships. Results also suggested that marital permanence may be particularly important to perceptions of well-being in marital relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Scholarship has highlighted the importance of marital beliefs on several components of individual and relational development. Recent scholarly efforts have suggested that how an individual conceptualizes the marital institution and their own marriage, regardless of whether that marriage is in the future, present, or past, has an impact on a diverse range of outcomes (Carroll et al. 2007; Masarik et al. 2012; Willoughby et al. 2013). Such studies have suggested that marital beliefs are associated with such outcomes as individual risk taking (Carroll et al. 2007, 2009), sexual decision making (Willoughby and Dworkin 2009; Willoughby and Carroll 2010), mental health (Carlson 2012), and union formation behavior (Clarkberg et al. 1995; Willoughby 2014; Willoughby et al. 2013).

While this body of scholarship has given strong support to the notion that marital beliefs have an association with individual decision making, many gaps remain in attempting to understand how or why such associations exist. The majority of this research has utilized basic regression models to test bivariate relationships between marital beliefs and outcomes with little attention currently being given to the mechanisms behind such associations. While this evidence may suggest that marital beliefs are in some ways altering the probability of engaging in certain actions, researchers have noted that we know little about why such increases occur (Carroll et al. 2007, 2009). Furthermore, this area of scholarship has been conducted almost exclusively on individual outcomes such as risk taking or union formation decisions with little focus on how marital beliefs may associate with individual behaviors within an existing relational context.

The goal of the present study was twofold and sought to address both of these current limitations in our understanding of marital beliefs. First, utilizing a national sample of individuals in romantic relationships, I sought to explore how marital beliefs, specifically beliefs regarding marital salience and permanence, might directly and indirectly relate to individual perceptions of relational outcomes. I focus on how marital beliefs may be related to the perception of both relationship satisfaction and stability. Second, I sought to examine the mechanisms behind such associations by exploring possible mediating factors that lie between marital beliefs and relational outcomes. To accomplish this, I explored how both individual commitment to the relationship and individual relational effort may mediate any relationship between marital beliefs and relational outcomes.

Marital Paradigms

While marital belief research is not new to the social sciences, the work in this area has until recently been largely atheoretical and devoid of consistency in both measurement and conceptualization. Recent scholars have attempted to change this trend by offering several studies aimed at explaining the nature, causes, and consequences of marital beliefs. However, these studies have often been limited in their theoretical scope and only recently have scholars attempted to create a holistic model for conceptualizing how one thinks about marriage and the marital institution. Willoughby et al. (2013) proposed a Marital Paradigm Theory of marital beliefs and argued that each individual holds a distinct and unique paradigm about marital relationships. One’s marital paradigm was proposed to be constructed across six dimensions: marital salience, marital timing, marital context, marital process, marital permanence, and marital centrality. Central to the present study, Willoughby and colleagues also argued that such paradigms will drive behavior by changing individual intentions. Intentions were defined as “a specific inclination to engage in a behavior” (Willoughby et al. 2013, p. 24). Extending ideas from earlier theories of attitudes and behavior, particularly Azjen’s (1991) theory of planned behavior, Marital Paradigm Theory argued that one’s general beliefs about marriage will lead to specific intentions to engage in behavior, thus leading to an increased likelihood of engaging in a given behavior.

Applied to previous research linking marital beliefs to premarital risk behavior (Clark et al. 2009; Carroll et al. 2007; Willoughby and Dworkin 2009), Marital Paradigm Theory argues that certain marital paradigms may alter individual intentions to engage in risk taking. For example, a desire to postpone marriage or a devaluing of marriage as an institution would be theorized to lead to a greater intention of viewing an extended period of risk taking during young adulthood as acceptable. This will in turn lead to a greater propensity to actually engage in risk-taking behavior. This process would account for the elevated binge-drinking rates seen among young adults who desire to postpone marriage (Carroll et al. 2007).

Applied to the current study, one would assume that one’s marital beliefs would also lead to changes in one’s intentions regarding specific relational behavior and that these intentions would lead to varying actions within one’s relationship. Unlike work linking marital beliefs and individual risk taking, less recent research has explored how general marital beliefs may change or be associated with specific relational behaviors or outcomes, although some studies have found that specific marital intentions or expectations may alter relational trajectories (Barr and Simons 2012). Carlson et al. (2004) also found that positive views of marriage were linked to a greater likelihood of marrying compared with breaking-up at a 1-year follow-up among a sample of non-married parents. Other evidence has suggested that marital beliefs may change the likelihood of both the type and frequency of premarital dating (Crissey 2005; Goldscheider et al. 2009).

Extending these findings, Marital Paradigm Theory would suggest that marital beliefs should not just influence trajectories in or out of specific relationships, but the internal working dynamics of each specific romantic relationship one is engaged in. Recently, some studies have begun to suggest more specific links between marital beliefs and specific relationship dynamics, providing initial evidence of such an association. Barr and Simons (2012) found that positive views of marriage among men were correlated with men’s marital satisfaction. Masarik et al. (2012) also found that among a sample of young adults, beliefs that marriage will be fulfilling or an investment were linked to young adult relationship quality and that such beliefs mediated relationships between family background and relational quality. Specifically, beliefs that marriage would be fulfilling were associated with higher reports of premarital dating quality and more positive relationship interactions. Riggio and Weiser (2008) likewise found links between positive marital beliefs and outcomes such as conflict, satisfaction, and commitment among a sample of college students. Again, positive attitudes toward marriage were linked to less conflict, higher satisfaction, and more commitment.

Although this research provides early evidence to Marital Paradigm Theory’s claim that positive beliefs about marriage may impact specific relationship dynamics and outcomes, previous research has largely focused on young adult samples and no study has explored possible indirect pathways between marital beliefs and specific relational outcomes, such a satisfaction and stability. Such information would not only provide additional insight for scholars seeking to understand why martial beliefs influence individual and relational functioning but would also help provide clinicians and relationship educators with important information regarding how their clients’ perceptions about marriage and relationships may impact the actual behavioral dynamics within their current and future relationships.

Relational Functioning and Well-Being

Before exploring such links, it is important to outline the elements of relational well-being in order to determine the most likely mechanisms between marital beliefs and relational outcomes. While there are many proposed models of relational functioning linking individual relational processes to the perception of relational outcomes, I chose here to focus on two factors deemed central to the perception of outcomes based on recent scholarship and likely linked to marital beliefs. Both individual commitment (Owen et al. 2011; Stanley and Markman 1992) and individual relational effort (Wilson et al. 2005) have been found to be critical components of healthy relationship development and functioning. Additionally, as marital beliefs are hypothesized to change individual intentions within a given relationship, intentions to commit to one’s partner and intentions to engage in proactive efforts to strengthen one’s relationship seem likely candidates to explore.

Commitment has long been a focus of relationship scholarship, dating back to early work focused on interdependence theory (Kelley and Thibaut 1978). Recent scholarship has specifically focused on how the intrinsic desire to be with a partner, often labeled dedication commitment (Stanley and Markman 1992), creates a sense of shared relationship identity that is essential for long-term relationship success and happiness (Fincham et al. 2007). Such commitment is thought to increase one’s desire to engage in positive relationship behavior and contributes to the minimalizing of potential conflict areas within a relationship. As such, dedication commitment has been linked to greater perceptions of relational quality such as higher relationship satisfaction (Owen et al. 2011) and stability (Le and Agnew 2003; Rhoades et al. 2010).

Relational effort is another component of relational quality deemed important by recent scholarship. Some scholars have noted that marital and relationship research has recently moved away from focusing on negative components of relationship functioning (such as conflict) and has relied more heavily on understanding positive elements of relational well-being. Fincham et al. (2007) recently argued that such “transformative processes” and positive behaviors have begun to be a stronger focus of the empirical research on relationships. One such positive behavior scholars have examined is the desire to exert effort in one’s relationships. Deriving from psychological research on self-regulation (Halford et al. 1994), the concept of relational effort focuses on the internal desire one has to put forth effort and energy into one’s relationship. Relational effort can also be conceptualized as the perceived ability or desire to change one’s actions to improve one’s relationship. Created by the inherent assumption that healthy relationships will in fact take work and effort, Wilson et al. (2005) argued that relational effort is a fundamental element of healthy relationship functioning. Multiple studies have suggested that relationship effort and self-regulatory behaviors are linked to higher reports of relationship satisfaction (Braithwaite et al. 2011; Pepping and Halford 2012; Wilson et al. 2005), again providing evidence that such effort is fundamental to relationship success.

In the present study, individual assessments of relationship outcomes (as measured by both the perception of satisfaction and stability) were theorized to be directly associated with both individual commitment and relational effort based on this previous research. Figure 1 outlines the theoretical model for the present study. It was hypothesized (see right hand side of Fig. 1) that increased individual commitment and more relationship effort would be associated with higher perceptions of both relationship satisfaction and stability. It was also hypothesized that higher individual commitment would be associated with similar elevated levels of relational effort. Some research has suggested that commitment may increase an individual’s desire or motivation to put energy into a relationship (Finkel et al. 2002), thus linking commitment and perceived relational effort.

Present Study

As mentioned previously, the present study was designed to address two important gaps in the scholarship currently available on marital beliefs. First, I sought to examine how marital beliefs might be associated with the relational outcomes of both relationship stability and satisfaction through elevated commitment and relational effort utilizing a sample of individuals across the life course and USA. While previous studies have found general links between these variables during young adulthood (see Masarik et al. 2012), no study has examined these indirect relationships or attempted to replicate such results across a broader sample. It was assumed that when individuals place a higher importance and priority on long-term relationships (in this case marriage), such beliefs would be associated with more investment in and commit to their current romantic relationships. This investment will in turn be associated with an increased likelihood of perceiving positive relational outcomes. To test these possible mediating factors between marital beliefs and relationship outcomes, I hypothesized that marital beliefs may have a direct association with both individual commitment and relationship effort and an indirect association on relationship outcomes (satisfaction and stability). I drew on two factors of Marital Paradigm Theory, marital salience and marital permanence, to assess marital beliefs. Specifically, I tested the following hypothesis:

H1: A stronger belief in the salience and permanence of marriage will have a direct and positive association with individual commitment and level of relationship effort and an indirect and positive association with the perception of relationship satisfaction and stability.

Beyond this primary hypothesis, I also explored how associations with marital beliefs may alter based on the type of relationship one is currently in. Currently no research has explored how relational status may alter the associations between marital beliefs and individual relational behavior. However, Willoughby et al. (2013) argued that the act of being married likely influences both the marital beliefs one holds and their impact on daily decisions. Those in more stable and committed relationships (such as cohabiting and especially marital relationships) may be more influenced by their perceptions regarding marriage as they draw on beliefs about long-term relationships to help shape their behavior. Those in dating relationships, which may be less serious, less stable, and more fluid, may be less influenced by global perceptions about marriage. One might also expect that beliefs about marriage would be more salient and influential for those currently in a marital relationship and possibly less so among those in unmarried relationships. To test this, I conducted group comparisons to test the following additional hypothesis:

H2: The tested direct and indirect associations of marital beliefs will be stronger for those in marital relationships.

Methods

Sample and Participants

The sample for the present study was comprised of individuals who took the RELATE instrument online (Busby et al. 2001) and consisted of 962 individuals in committed relationships. All participants completed an appropriate consent form prior to the completion of the RELATE instrument and all data collection procedures were approved by the institutional review board at the author’s university. Individuals completed RELATE online after being exposed to the instrument through a variety of settings. The RELATE assessment is an assessment designed to assess and provide feedback to those in romantic relationships and is a common intervention and educational tool used throughout the USA. After taking the RELATE, individuals are provided with feedback on their relationship strengths and weaknesses that they can utilize either on their own or in conjunction with a third party (i.e., religious leader and clinician). Some participants were referred to the online site by their instructor in a university class, others by a relationship educator or therapist, and some participants found the instrument by searching for it on the web. We refer the reader specifically to Busby et al.'s (2001) discussion of the RELATE for detailed information regarding the theory underlying the instrument and its psychometric properties.

While the sample drawn from RELATE includes individuals from across the USA, the sample itself cannot be considered nationally representative. Based on reports from other studies utilizing RELATE data, those who complete the RELATE assessment tend to be more educated, have higher incomes, and lack racial diversity (Willoughby et al. 2012), biases that were also present in the current sample. To provide a more representative sample and slightly reduce some of this bias, a quota sample of individuals was drawn from the total population of RELATE participants to bring the sample closer to the general demographics of the US population according to the US Census. Such a technique has been suggested as a way to deal with large convenience national samples that are not organically representative of a given population (Cozby 2007) and has been used previously with the RELATE dataset (Busby et al. 2005; Busby et al. 2009). This quota sampling was focused on two demographics within the RELATE sample most divergent with national proportions: race and religious affiliation. Random quota sample was done by first selecting out all the members of the smallest underrepresented racial group, in this case, the African American group, and then selecting out random subsamples of the other groups so that the percentages of all the racial groups are closer to national norms. This same technique was then used to match national frequency distributions for religious affiliation. While this reduced the total number of participants used, preliminary power analyses suggested the sample size was still more than adequate to detect differences in models explored.

After the quota sample was created, the largest racial group was White (52.7 %) followed by Black (19.9 %), Latino (18.4 %), and Asian (5.4 %) participants. Sixty-four percent of the sample was female. The largest religious denomination within the sample was Protestant (41.5 %). Sixteen percent of the married sample had been married for 2 years or less, while 8.9 % had been together for more than 20 years. Most (64.9 %) couples had been together between 1 and 5 years. The average age of the sample was 31.48 years (SD = 9.53) with a range from 18 to 79. Most of the sample (66 %) had some type of college degree suggesting that the sample was still more educated than a truly nationally representative sample. More detailed information on the sample is shown in Table 1.

Measures

Marital Beliefs

The belief placed on marriage as an institution was assessed with two items tapping the marital salience and marital permanence dimensions of Marital Paradigm Theory (Willoughby et al. 2013). Previous research has suggested that such beliefs (often labeled marital importance in previous literature) may be particularly important in predicting individual behavior (Carroll et al. 2007; Willoughby and Carroll 2010). Participants were asked how much they agreed with the following items on a five-point scale (1 = strong disagree; 5 = strongly agree): “Being married is among the one or two most important things in life,” and “If I had an unhappy marriage and neither counseling nor other actions helped, my spouse and I would be better off if we divorced (reverse coded).” These items were significantly but modestly correlated (r = .204, p < .001) suggesting that the two items likely tapped different constructs. Initial factor analysis results (not reported here) confirmed this assumption based on factor loadings and overall model fit. Due to these findings, these two single items were utilized as single-item indicators of marital salience and permanence. While not ideal, scholars have noted that single-item indicators of marital beliefs tend to be robust predictors of individual behavior and have been widely used in this area of scholarship (Willoughby et al. 2012).

Commitment

Commitment was assessed by three items adapted from the Commitment Inventory (CI; Stanley and Markman 1992). Participants were asked how much they agreed with each item on a five-point scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). Higher scores indicated more commitment. Specific items included: “My relationship with my partner is more important to me than almost anything else in my life,” “I may not want to be with my partner a few years from now (reverse coded),” and “I want this relationship to stay strong no matter what rough times we may encounter.” Reliability for this scale was in the acceptable range (α = .72). Previous research has suggested that these items show good internal consistency across samples and strong criteria-related validity with other relational adjustment and communication measures (Owen et al. 2011).

Relational Effort

Relational effort was also assessed by three items adopted from the Behavioral Self-Regulation for Effective Relationships Scale (BSRERS; Wilson et al. 2005) and assessed individuals’ perception that they can put effort into their relationships that will have a positive association with well-being. These items were assessed on a five-point scale where participants rated how true each statement was of themselves (1 = never true; 5 = always true). The specific items were as follows: “If things go wrong in the relationship I tend to feel powerless (reverse coded),” “Even when I know what I could do differently to improve things in the relationship, I cannot seem to change my behavior (reverse coded),” and “If my partner doesn’t appreciate the change efforts I am making, I tend to give up (reverse coded).” Higher scores indicated a greater perception that one’s efforts would positively impact the relationship. Previous research has suggested these items have strong test–retest reliability and demonstrate concurrent validity with relationship satisfaction (Wilson et al. 2005). Reliability for this scale was slightly low (α = .65), but all factor loadings in final structural models suggested adequate loadings (Brown 2006).

Relationship Outcomes

Two assessments of overall relational well-being were assessed. Relationship satisfaction was assessed with seven items asking participants how satisfied they were with various aspects of their relationship (for example, in their sexual relationship and with the overall relationship). Items were rated on a 5-point scale (1 = very dissatisfied to 5 = very satisfied). The RELATE satisfaction measures employed in this study have shown high test–retest reliability (between .76 and .78), and validity data have consistently shown that this scale is highly correlated with an existing relationship satisfaction and quality scale (Revised Dyadic Adjustment Scale) in both cross-sectional research and longitudinal research (Busby et al. 2001, 2009). Reliability for this scale was in the acceptable range (α = .89).

Relationship stability was assessed by three items which asked participants how often the following three things had happened in their relationship: “How often have you thought your relationship (or marriage) might be in trouble?”, “How often have you and your partner discussed ending your relationship (or marriage)?”, and “How often have you broken up or separated and then gotten back together?” Responses ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). These items were reverse coded so that higher scores indicated more stability. These items were adapted from earlier work by Booth et al. (1983). Previous studies have shown this scale to have test–retest reliability values between .78 and .86, to be appropriately correlated with other relationship quality measures, and to be valid for use in cross-sectional research and longitudinal research (Busby et al. 2001, 2009). Reliability for this scale was in the acceptable range (α = .80).

Controls

Age, gender (coded male = 0; female = 1), and religious attendance were all used as controls for analyses. Religious attendance was assessed by one item asking each participant how often they attended religious service (0 = never; 4 = weekly). Relational status was also coded by asking each participant what type of relationship they were currently in. Those in dating, cohabiting, and marital relationships were coded as such.

Data Analysis

All measurement items were first run in an initial exploratory factor analyses to examine whether the proposed scales held. This initial factor analysis suggested that all items loaded on four independent factors with each item loading on its expected factor and none of the items cross-loading on additional scales. A CFA of the proposed measurement model with each individual item being a single indicator for one latent variable was then run in MPlus. Results from the CFA model provided evidence of good fit [χ2 (92) = 372.82, p < .001; RMSEA = .06; CFI = .96; TLI = .95; and SRMR = .04.] suggesting the proposed measurement model adequately fit the data. Table 2 summarizes all factor loadings for individual items. Measurement invariance was tested across groups (dating, cohabiting, and married). All measurement structures were found to be invariant across groups.

To examine relationships between marital beliefs and other relational constructs, structural equation modeling (SEM) was utilized. All SEM models were run using MPlus version 7 software (Muthén and Muthén 1998). Full-information maximum likelihood estimators for missing data were utilized unless otherwise noted. Overall goodness of fit for each model was assessed by examining Chi-square, RMSEA, CFI, TLI, and SRMR values. Although all fit indices were examined, Chi-square scores are sensitive to large sample sizes (Wang and Wang 2012) and thus, more emphasis was given to the other indicators of model fit. If model fit was adequate, specific path coefficients were examined for significance. Indirect effects utilizing the Sobel method within Mplus between marital beliefs and relational outcomes were also tested. This method provides a conservative estimate of indirect effects and should provide accurate estimates given the normality of the data used and large sample size. To examine whether relationship status moderated associations across constructs, multi-group SEM models were examined with specific direct and indirect effects tested for equivalence across groups. All models controlled for gender, age, and religious attendance. All mediating and dependent variables were regressed on all control variables in the model.

Results

Basic Associations

The average score on the marital salience item was 3.69 (SD = 1.11) and the average score on the marital permanence item was 2.83 (SD = 1.16), suggesting that the sample had generally positive beliefs about marriage and the marital institution. Sample means for commitment (M = 4.37; SD = .64), relational effort (M = 3.31, SD = .68), stability (M = 4.02, SD = .84), and satisfaction (M = 3.80, SD = .81) suggested that those in the sample had on average, positive and well-functioning relationships. Simple bivariate relationships between marital beliefs and perceptions of relationship outcomes suggested weak but significant positive associations with both satisfaction (marital salience: r = .115, p < .001; marital permanence: r = .166, p < .001) and stability (marital salience: r = .088, p < .001; marital permanence: r = .156, p < .001). All inter-correlations among latent variables are presented in Table 2. As expected, relationship dynamics and outcome variables were modestly correlated with the largest association being between stability and satisfaction (r = .586). While modest, simulation studies have suggested that associations of such magnitude are unlikely to cause multicollinearity problems, especially in light of the large sample size of the present study and fairly large R 2 values of our two outcome variables (Grewal et al. 2004).

Initial Model Fit and Results

Before examining specific indirect effects, an initial structural model was examined for adequate model fit. When examining model fit, several indicators are typically appropriate to examine. A good fitting model is generally defined as one where RMSEA is <.05; CFI is at least .95; TLI is at least .90; and SRMR is <.08 (Hu and Bentler 1999; Wang and Wang 2012). These results suggested that the proposed structural model was a good fit for the data after controlling for gender, age, and religious attendance [χ2 (155) = 488.87, p < .001; RMSEA = .05; CFI = .96; TLI = .94; SRMR = .04.]. Figure 2 shows the standardized loadings between structural factors controlling for age, religious attendance, and gender. Of the nine theorized effects, seven (78 %) were found to be significant. As expected (hypothesis 1), marital beliefs did have a significant and positive relationship with reported commitment with significant associations found for both marital salience (β = .21, p < .001) and permanence (β = .23, p < .001). The more importance and permanence one placed on marriage, the more those same individuals reported being committed to their partner. Contrary to hypothesis one, both marital salience (β = −.06, p = .14) and permanence (β = −.01, p = .87) did not have a significant association with relational effort. All other relational process associations were significant and in the expected directions. More reported commitment was associated with more relational effort and higher reports of satisfaction and stability. Higher reports of relational effort were also linked to higher satisfaction and stability. Examination of R 2 values suggested that the proposed model explained 61 % (p < .001) of the variance in relationship satisfaction and 51 % (p < .001) of the variance in relationship stability.

Indirect Effect of Marital Beliefs

Having established a direct effect between marital beliefs and relational commitment, indirect effects from marital beliefs to relational outcomes through both commitment and relational effort were next examined. Specific and total indirect effects are summarized in Table 3. For both outcomes, three indirect effects were examined. Indirect effects from marital beliefs through commitment, one from marital beliefs through relational effort and one from marital beliefs, through commitment to relational effort and then to outcomes were tested. Marital salience (β = .11, p < .001) and permanence (β = .14, p < .001) both had significant total standardized indirect effects on relationship satisfaction. Of the three indirect effects tested, two were significant for each marital belief. A significant indirect effect was found from marital beliefs through commitment which comprised the majority of the indirect effect. A significant indirect effect was also found through commitment and relational effort. No indirect effect was found for either marital beliefs predicting relational satisfaction through relational effort.

For relationship stability, the total indirect effect of marital salience was .10 (p < .001) and .13 (p < .001) for marital permanence. Again, two of the three tested specific indirect effects were significant for both marital beliefs. A significant indirect effect for both beliefs was found from marital beliefs to stability through commitment as well as one from marital beliefs to stability through commitment and relational effort. Like satisfaction, the indirect effect from beliefs to stability through relational effort for both beliefs was not significant.

In the case of both outcomes and both marital beliefs, the nature of the indirect effect was similar. Marital beliefs were strongly and indirectly associated with relational outcomes in that more positive beliefs about marriage and the marital institution were associated with higher reports of commitment to one’s partner, which in turn were associated with more positive relational outcomes. There was also a weaker indirect effect found in that positive beliefs about marriage were associated with more reported commitment. This higher level of commitment was in turn associated with more reported relational effort and then more positive relational outcomes. Preliminary analyses (not fully reported here) suggested that no gender differences were found across structural parameters. Additionally, fully saturated models where marital beliefs were allowed to directly predict perceptions of relationship satisfaction and stability suggested that when pathways through commitment were included, no significant direct effects were found further supporting the finding that commitment fully mediates the relationship between marital beliefs and perceptions of relational outcomes.

Multi-group Analysis

In order to test hypothesis two and examine whether the proposed structural model held across the three relational groups (dating, cohabiting, and married), a multi-group analysis was conducted. Due to non-normality on some scales across these smaller samples, MLMV, a more robust estimator was utilized in these analyses.

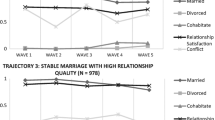

Following procedures suggested by Wang and Wang (2012), independent structural models were first fit for each relational status group separately to visually examine possible differences in structural pathways. These separate group models can be seen in Fig. 3. In all three cases, adequate model fit was achieved. While relational process coefficients between commitment, relational effort, satisfaction, and stability were identical across groups, the path between marital salience and individual relational effort was only significant among married (β = −.18, p < .05) participants with greater marital salience being associated with less relational effort. Among cohabiting and dating participants, this path coefficient was not significant.

Standardized path coefficients for those in dating/cohabiting/married relationships. Model controlled for gender, age, and religious attendance. Specific factor loadings and error terms are omitted. *p < .05, **p < .01 Dating: [χ2 (158) = 291.08, p < .001; RMSEA = .05; CFI = .94; TLI = .93; SRMR = .05]; Cohabiting: [χ2 (158) = 304.25, p < .001; RMSEA = .05; CFI = .95; TLI = .94; SRMR = .04.]; Married: [χ2 (158) = 263.20, p < .001; RMSEA = .06; CFI = .95; TLI = .93; SRMR = .05.]

To test whether this coefficient did indeed significantly vary across groups, a configural model was fitted which allowed all parameters to freely vary across groups. Next, invariance in structural path coefficients was tested by defining additional models where specific structural parameters were restricted as equal across groups. Specifically, the parameter regressing relational effort on marital salience was constrained to be equal across relational groups and tested for invariance. Chi-square difference tests were then conducted to see whether the restricted or unrestricted model fit the data better. The difference test between those in dating and those in marital relationships was not significant (χ2(1) = 2.65; p = .10) nor was the difference test between those in cohabiting and married relationships (χ2(1) = 2.28; p = .13). Thus, even though individual structural models suggested that marital salience was significantly associated with individual relational effort for those in married relationships, tests of invariance in structural pathways suggested that significant differences were not detected between those in married relationships and those in other types of relationships.

The paths between marital beliefs and commitment were next examined for invariance as visual inspection of these pathways across groups suggested that the effect varied in magnitude. The Chi-square difference test between the restricted and unrestricted model for that path between marital salience and individual commitment among those in married and cohabiting relationships was not significant (χ2(1) = 1.03; p = .31). However, the path between marital permanence and individual commitment was significant (χ2(1) = 8.94; p = .002) suggesting that this effect was not invariant between groups. Similarly, the pathways between marital permanence and individual commitment were also found to be not invariant between those in marital and those in dating relationships (χ2(1) = 10.01; p = .002). An examination of standardized coefficients suggested that a stronger belief in marital permanence had a stronger association with individual commitment for those in marital relationships compared with those in both cohabiting and dating relationships. All pathways between marital beliefs and relational dynamics among those in dating and cohabiting relationships were found to be invariant.

Invariance in indirect pathways from marital beliefs to the perception of relational outcomes through individual commitment was examined next. Wald tests suggested that the indirect effect of marital permanence on satisfaction through commitment was not invariant between those in married (indirect effect = .23, p < .001) and dating (indirect effect = .12, p = .01) relationships (χ2(1) = 10.14; p = .002) as was the indirect effect for stability (married: indirect effect = .20, p = .001; dating: indirect effect = .09, p = .02; χ2(1) = 7.42; p = .007). In all of the above analyses, the indirect effect of marital permanence on the perception of relational outcomes was stronger for those in marital relationships. The indirect effect from marital permanence to satisfaction (χ2(1) = 2.46; p = .12) and stability (χ2(1) = 1.03; p = .31) between those in cohabiting and dating relationships was found to be invariant. Indirect pathways from marital salience through individual commitment to outcomes were all found to be invariant across groups.

In summary, multi-group analyses suggested that stronger beliefs in marital salience and permanence were generally related to more individual commitment and a higher perception of relational outcomes for those in dating, cohabiting, and marital relationships. However, significant group differences in direct and indirect structural parameters suggested that marital permanence had a stronger direct association with individual commitment and indirect associations with the perception of relational outcomes among those in marital relationships. This suggests that while the effect of marital salience is relatively stable across relational types, the effect of marital permanence is significantly larger among those in married relationships, partially supporting hypothesis two.

Discussion

Results from the present study provide several important developments for the scholarship related to marital beliefs and their potential association with the perception of relational well-being. First, results clearly suggest that cognitions and beliefs about the institution of marriage generally have an influence on specific individual relational processes. Specifically, although no direct association was found with individual relational effort, greater beliefs that marriage is an important and permanent institution appear to be associated with stronger levels of commitment to one’s partner which in turn was related to more relational effort and higher perceptions of relational satisfaction and stability. While previous studies have documented that marital beliefs are associated with individual decisions prior to marriage (Carroll et al. 2007; Willoughby and Dworkin 2009), results here provide additional evidence that such an association is also relational. In line with marital paradigm theory (Willoughby et al. 2013), how individuals conceptualize long-term relational unions such as marriage may alter the relational processes and individual perceptions they have about specific relationships. While previous studies have found that marital beliefs are generally associated with relational outcomes among young adults (Masarik et al. 2012), the results here help suggest that such a result generalizes across a broader sample and suggests that one of the primary mechanisms through which marital beliefs are associated with relational outcomes is individual commitment to specific relationships. Indeed, results here suggest that generalized positive beliefs about marriage are associated with greater individual commitment to one’s partner and that this commitment is linked to more positive appraisals of one’s relationship.

Such associations fall in line with assumptions derived from marital paradigm theory and commitment theory. Marital paradigm theory has suggested that how one thinks about marriage will influence intentions to engage in specific behavior, both relationally and individually. With commitment acting as a proxy for intention in the current study based on previous research (Finkel et al. 2002), results from the present study appear to provide some confirmation for this theoretical assumption. Individuals who placed a stronger value on marriage (and perhaps by extension, long-term-committed relationships) appear to also be more committed to their specific romantic partner. This commitment may provide motivation to put effort and resources into the relationship, thus increasing relational effort and one’s belief that a relationship is satisfying and stable. As found in previous studies (Wilson et al. 2005) increased effort stemming from commitment is often associated with more favorable relational outcomes. Although previous studies have linked commitment to relational effort and relational outcomes, results here provide initial support for the assumption that marital and relational beliefs may serve as important contextual factors driving differing levels of commitment within one’s relationships. Such findings may suggest that developmental scholars may wish to track how both marital beliefs and commitment levels may vary across time to understand how the development of adult relationships may be influenced by reciprocal relationships across both variables.

Multi-group results suggested some interesting caveats to these findings. Specifically, it was found that the association between both types of marital beliefs and commitment was found for those in all types of relationships. While it might be assumed that marital beliefs would associate with the relationship behaviors of those already in marital relationships, that this association was stable across relationship types suggests that marital beliefs are not just important to those already in marital relationships and an important developmental variable at several ages. A growing body of the literature (Carroll et al. 2007; Willoughby et al. 2012, 2013) is suggesting that marital beliefs for individuals at all ages and relational statuses are important factors to consider when attempting to understand behavior across a wide range of outcomes. For this reason, developmental scholars interested is relational development at various time points in the life course should consider how beliefs about marriage may be important correlates of developmental outcomes. Further, scholars should continue to explore whether results found here may be replicated in additional developmental periods not tested such as during adolescence or later life stages.

Implications for Scholars, Practice, and Policy

Results also suggest important developmental implications, particularly perhaps for the current and future emerging adult population. As emerging adults continue to delay committed relationships such as marriage (Copen et al. 2012) and shift how they think and perceive the institution of marriage (Wilcox and Marquardt 2011), such shifts may have implications for the relational processes within such relationships based on current results. Shulman and Connolly (2013) recently noted that emerging adulthood is a critical and unique time for emerging adults to get experience with relationships, and results from the present study may suggest that as emerging adults place less priority, importance, and permanence on marriage, commitment levels in such relationships may drop. Such shifting commitment levels may impact the prevalence of casual sexual partnerships, the number of emerging adults who transition to cohabiting relationships, and decisions to transition to marriage during emerging adulthood. Of course, such causal links can only be suggested based on the cross-sectional data presented here, and more research is needed before the impact of such finding on emerging adulthood can be truly understood.

Such findings are also important for educators, clinicians, and policy makers as they suggest that marital beliefs and relational paradigms may be a currently ignored aspect of individual well-being as most programs and interventions focus exclusively on behavior. Findings of the current study suggest that while designing educational programs and interventions, scholars may want to consider exploring how individuals and couples conceptualize long-term relationships and current or future marriages.

In addition, multi-group analyses also suggested that although marital beliefs were associated with relational functioning for those in all types of relationships, associations with marital permanence were strongest and the most robust among those in marriages. While one would certainly expect those in marriages to express more positive marital beliefs on average than those in dating and cohabiting relationships, these results underscore the possible importance that holding strong views regarding the permanence of marriage may have on the stability and well-being of marital unions, a fact that may be important for scholars updating and creating new relational interventions or educational materials. With divorce rates remaining high (Bramlett and Mosher 2002) and an increasing proportion of marriages being reported as unhappy (Wilcox and Marquardt 2011), scholars have long sought to understand the correlates of successful and satisfying long-term marriages. These results suggest that marital paradigms and specifically beliefs in marital permanence may be a critical but often ignored aspect of marital function, a thought recently suggested by other research (Dew and Wilcox 2010). While previous research has suggested that commitment and relational effort (Owen et al. 2011; Wilson et al. 2005) are keys to marital outcomes, results here suggested that marital permanence may be one underlying mechanisms contributing to varying levels of commitment among married couples. Further study should continue to explore how other types of marital beliefs may be important elements of long-term marital success.

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite the important contributions of the present study, several limitations should be considered that limit the generalizability of the results. First, results here are cross-sectional and as such, determining casual pathways between marital beliefs and individual relational behavior is not possible. While it may be assumed that marital beliefs, commitment, and relational effort combine to influence perceptions of relational outcomes, it is also possible that higher perceptions of satisfaction and stability in relationships will reciprocally increase commitment and change one’s perception of marriage, something suggested by marital paradigm theory (Willoughby et al. 2013). Longitudinal studies are needed to truly understand these likely bidirectional pathways. The dataset utilized in the present study also only included data from one partner making it impossible to explore more complex actor–partner interactions between marital beliefs and individual behavior. Future studies should attempt to gather data from both partners in order to test both actor and partner effects to see whether such effects alter the relationships found.

Additionally, as noted in previous studies of marital beliefs (Willoughby 2010), no standardized measurement of marital paradigms current exists and so measurement of marital paradigms and beliefs in this study were limited. The data available in the current dataset necessitated the use of two single-item measures of marital beliefs. Marital paradigm theory suggests that marital beliefs are comprised of six related, yet distinct dimensions (Willoughby et al. 2013). While the results of the study suggest general relationships between marital beliefs and individual relational behavior, more specific measures tapping multiple elements of marital paradigm theory simultaneously would provide for a more robust assessment of the types of marital beliefs that have the strongest association with behavior. Additionally, the measure of relational effort within RELATE assessed lack of effort and not the presence of effort. Differing measures of relational effort may produce varying results than those reported here.

Finally, although quota sampling within the RELATE database allowed for a fairly diverse national sample in terms of race and religious affiliation, as noted previously, the data used for this project cannot be considered nationally representative and thus caution should be taken before generalizing these results to all couples. Participants tended to be more educated than the general population, and it is unknown whether the results found here would generalize to low-income populations and couples where relational processes and dynamics may be different.

Despite these limitations, results again provide important new information for scholars and clinicians interested in the influence of marital beliefs and cognitions on individual and couple well-being. Results documented that marital beliefs are associated with not only individual behavioral variation in relationships, but differing perceptions of relational outcomes across a diverse range of couples. Marital beliefs appear to be a component of how individuals operate and think about their romantic relationships, both during and prior to marriage, and seem to have a strong association with individual commitment to one’s partner. Particularly in a marriage, holding positive beliefs about the permanence of marriage appear to be associated with positive relational function and commitment. Given that most adults still value marriage (Wilcox and Marquardt 2011) but perceptions regarding marriage are also changing (Cherlin 2004), results also shed light on the implications of both cultural changes regarding the institution of marriage as well as the possible impact of public policies that may alter individuals’ general perception of the marital institution.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

Barr, A. B., & Simons, R. L. (2012). Marriage expectations among African American couples in early adulthood: A dyadic analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 726–742.

Booth, A., Johnson, D. R., & Edwards, J. N. (1983). Measuring marital instability. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45, 387–394.

Braithwaite, S. R., Selby, E. A., & Fincham, F. D. (2011). Forgiveness and relationship satisfaction: Mediating mechanisms. Journal of Family Psychology, 25, 551–559.

Bramlett, M. D., & Mosher, W. D. (2002). Cohabitation, marriage, divorce, and remarriage in the United States. Vital and Health Statistics (23). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. New York, NY: The Guildford Press.

Busby, D. M., Gardner, B. C., & Taniguchi, N. (2005). The family of origin parachute model: Landing safely in adult romantic relationships. Family Relations, 54, 254–264.

Busby, D. M., Holman, T. B., & Niehuis, S. (2009). The association between partner- and self enhancement and relationship quality outcomes. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 449–464.

Busby, D. M., Holman, T. B., & Taniguchi, N. (2001). RELATE: Relationship evaluation of the individual, family, cultural, and couple contexts. Family Relations, 50, 308–316.

Carlson, D. L. (2012). Deviations from desired age at marriage: Mental health differences across marital status. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 743–758.

Carlson, M., McLanahan, S., & England, P. (2004). Union formation in fragile families. Demography, 41, 237–261.

Carroll, J. S., Badger, S., Willoughby, B., Nelson, L. J., Madsen, S., & Barry, C. M. (2009). Ready or not? Criteria for marriage readiness among emerging adults. Journal of Adolescent Research, 24, 349–375.

Carroll, J. S., Willoughby, B., Badger, S., Nelson, L. J., Barry, C. M., & Madsen, S. D. (2007). So close, yet so far away: The impact of varying marital horizons on emerging adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Research, 22, 219–247.

Cherlin, A. J. (2004). The deinstitutionalization of American marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 848–861.

Clark, S., Poulin, M., & Kohler, H. (2009). Marital aspirations, sexual behaviors, and HIV/AIDS in rural Malawi. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 396–416.

Clarkberg, M., Stolzenberg, R. M., & Waite, L. J. (1995). Attitudes, values and entrance into cohabitation versus marital unions. Social Forces, 74, 609–634.

Copen, C. E., Daniels, K., Vespa, J., & Mosher, W. (2012). First marriages in the United States: Data from the 2006–2010 National Survey of Family Growth. National health statistics reports (49). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Cozby, P. C. (2007). Methods in behavioral research (9th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Crissey, S. R. (2005). Race/ethnic differences in the marital expectations of adolescents: The role of romantic relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 697–709.

Dew, J., & Wilcox, W. B. (2010). Is love a flimsy foundation? Soulmate versus institutional models of marriage. Social Science Research, 39, 687–699.

Fincham, F. D., Stanley, S. M., & Beach, S. R. (2007). Transformative process in marriage: An analysis of emerging trends. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 275–292.

Finkel, E. J., Rusbult, C. E., Kumashiro, M., & Hannon, P. A. (2002). Dealing with betrayal in close relationships: Does commitment promote forgiveness? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 956–974.

Goldscheider, F., Kaufman, G., & Sassler, S. (2009). Navigating the “new” marriage market: How attitudes toward partner characteristics shape union formation. Journal of Family Issues, 30, 719–737.

Grewal, R., Cote, J. A., & Baumgartner, H. (2004). Multicollinearity and measurement error in structural equation models: Implications for theory testing. Marketing Science, 23, 519–529.

Halford, W. K., Sanders, M. R., & Behrens, B. C. (1994). Self-regulation in behavioral couples therapy. Behavior Therapy, 25, 431–452.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

Kelley, H. H., & Thibaut, J. W. (1978). Interpersonal relations: A theory of interdependence. New York: Wiley.

Le, B., & Agnew, C. R. (2003). Commitment and its theorized determinants: A meta-analysis of the investment model. Personal Relationships, 10, 37–57.

Masarik, A. S., Conger, R. D., Martin, M. J., Donnellan, M. B., Masyn, K. E., & Lorenz, F. O. (2012). Romantic relationships in early adulthood: Influences of family, personality, and relationship cognitions. Personal Relationships. Advanced online publication. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2012.01416.x/abstract

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2011). Mplus User’s Guide. Sixth Edition. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Owen, J., Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., & Markman, H. J. (2011). The revised commitment inventory: Psychometrics and use with unmarried couples. Journal of Family Issues, 32, 820–841.

Pepping, C. A., & Halford, W. K. (2012). Attachment and relationship satisfaction in expectant first-time parents: The mediating role of relationship enhancing behaviors. Journal of Research on Personality, 46, 770–774.

Rhoades, G. K., Stanley, S. M., & Markman, H. J. (2010). Should I stay or should I go? Predicting dating relationship stability from four aspects of commitment. Journal of Family Psychology, 24, 543–550.

Riggio, H. R., & Weiser, D. A. (2008). Attitudes toward marriage: Embeddedness and outcomes in personal relationships. Personal Relationships, 15, 123–140.

Shulman, S., & Connolly, J. (2013). The challenge of romantic relationships in emerging adulthood reconceptualization of the field. Emerging Adulthood, 1(1), 27–39.

Stanley, S. M., & Markman, H. J. (1992). Assessing commitment in personal relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family, 54, 595–608.

Wang, J., & Wang, X. (2012). Structural equation modeling: Applications using Mplus. United Kingdom: Wiley.

Wilcox, W. B., & Marquardt, E. (Eds.). (2011). The State of our Unions, 2011. Charlottesville, Virginia: The National Marriage Project.

Willoughby, B. J. (2010). Marital attitude trajectories across adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 1305–1317.

Willoughby, B. J. (2014). Using marital attitudes in late adolescence to predict later union transitions. Youth and Society, 46, 425–440.

Willoughby, B. J., & Carroll, J. S. (2010). Sexual experience and couple formation attitudes among emerging adults. Journal of Adult Development, 17, 1–11.

Willoughby, B. J., Carroll, J. S., & Busby, D. M. (2012). The effects of “living together”: Determining and comparing types of cohabiting couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 29, 397–419.

Willoughby, B. J., & Dworkin, J. D. (2009). The relationships between emerging adults’ expressed desire to marry and frequency of participation in risk behaviors. Youth and Society, 40, 426–450.

Willoughby, B. J., Hall, S., & Luczak, H. (2013). Marital paradigms: A conceptual framework for marital attitudes, values and beliefs. Journal of Family Issues. Advanced online publication.

Wilson, K. L., Charker, J., Lizzio, A., Halford, K., & Kimlin, S. (2005). Assessing how much couples work at their relationship: The behavior self-regulation for effective relationship scale. Journal of Family Psychology, 19, 385–393.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Willoughby, B.J. The Role of Marital Beliefs as a Component of Positive Relationship Functioning. J Adult Dev 22, 76–89 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-014-9202-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-014-9202-1