Abstract

In this study, we explore the relationship between attitudes toward both marriage and cohabitation and sexual experience during emerging adulthood. Results from 990 emerging adults indicated only moderate evidence that marital attitudes are related to sexual experience but strong evidence of a relationship between attitudes toward cohabitation and sexual experience. In particular, sexually active emerging adults were more likely to have positive attitudes toward cohabitation. Furthermore, it was found that both religiosity and dating status moderate the relationship between couple formation attitudes and sexual experience. For highly religious emerging adults, sexual activity was associated with higher endorsement of cohabitation; however, this pattern was not present for emerging adults with low religiosity. Dating status was found to have some impact on the relationship between sexual behavior and attitudes toward marriage but did not greatly impact the overall pattern of relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Changing demographic trends over the last 50 years, such as delayed marriage (Kreider 2005) and increased attendance in secondary education (McLanahan 2004), have created what some view as a new period of development in young people’s lives. Some scholars have identified this period with terms such as “arrested adulthood” (Côté 2000) and “emerging adulthood” (Arnett 2000). One of the commonly identified features of emerging adulthood is the opportunity it provides young people for exploration and experimentation. Emerging adults often experiment in a series of romantic relationships, and their relationships are likely to include sexual intercourse (Martin et al. 2001; Michael et al. 1995).

Besides changes in family formation patterns, emerging adulthood has also been associated with changing norms regarding coupling behavior such as sexual activity. Although there was some evidence of declining rates of sexual activity among emerging adults during the 1990s (Christopher and Sprecher 2000; Ku et al. 1998), more recent research seems to indicate these decreases in young people’s sexual activity are being reversed in recent cohorts, particularly for males (Netting and Burnett 2004). Due to these trends, increased attention has been given to identifying what factors, such as religiosity and dating status, predict and moderate individual differences in young people’s sexual activity (Meschke et al. 2000; White and DeBlassie 1992).

Despite this focus on studying emerging adults’ sexual behavior, we know little about how this behavior affects later relationships, relational plans, and couple formation patterns. One consistent pattern to emerge is that premarital sexual activity has been found to be a possible risk factor for later divorce in marriage (Heaton 2002; Kahn and London 1991; Larson and Holman 1994; Teachman 2003). While this descriptive pattern has been repeatedly validated in the research literature, to date researchers have made little progress in explaining why this link might exist. One possible explanation is that premarital sex alters relational attitudes that might affect later couple outcomes. This study begins to address this issue by examining how young people’s sexual behavior is related to attitudes toward marriage and cohabitation in an effort to explore how premarital sexual experience influences relational attitudes.

Literature Review

Sexual Behavior and Attitudes

The average age of sexual initiation for most adolescents is around 16 years (Meschke et al. 2000). Although most emerging adults engaged in sexual activity for the first time during adolescence, sexual activity continues throughout young adulthood. Almost 80% of all emerging adults have had sexual intercourse at least once by the age of 20 (Haffner 1997). Research has also shown that nearly a third of college students have engaged in a casual sexual experience that involved vaginal intercourse (Paul et al. 2000). When the definition of casual sex is broadened to include oral sex or fondling, Paul et al. (2000) found that nearly 80% of college students have engaged in these activities outside of a committed relationship.

With rates of sexual behavior so high, one would expect emerging adults’ attitudes about sex to mirror these trends. Indeed, over the past few decades emerging adults have also become increasingly accepting of premarital sexual activity within a committed relationship (Martin et al. 2001; Treas 2002; Wells and Twenge 2005). Taking a developmental perspective Shulman and Seiffge-Krenke (2001), argue that adolescent relationships will naturally progress to include more sexual activity as a couple develops more characteristics of a true dyadic relationship. As adolescents and emerging adults enter serious dating relationships, they will probably see sexual activity as a more acceptable practice.

Despite the increased social acceptability of premarital sex, research has suggested that sexual activity with partners other than one’s future spouse is related to an increased likelihood of marital disruption (Heaton 2002; Kahn and London 1991; Larson and Holman 1994; Teachman 2003). Teachman (2003) found that women who had sex with someone other than their future spouse increased their risk of divorce by 114%. One possible explanation for this pattern is that emerging adults who engage in premarital sexual activity have different beliefs and attitudes toward couple formation which impact their individual and relational trajectories.

Sexual Activity and Couple Formation Attitudes

Attitudes Toward Marriage

Despite the potential links between sexual behavior and marital attitudes, marriage has been an underrepresented topic of emerging adulthood research (Carroll et al. 2007). As most emerging adults now delay marriage until their late twenties (Kreider 2005) and also no longer view marriage as an important criterion for adulthood (Arnett 1997), some may argue that marriage is no longer a useful concept to study during emerging adulthood. However, there is evidence that how emerging adults view marriage will have an impact on their current and future behavior. Studies have found that emerging adults who marry early decrease their participation in risk behaviors (Arnett 1998) and that attitudes toward marriage are linked to risk-taking in areas such as sexual activity, binge drinking and marijuana use (Carroll et al. 2007; Willoughby and Dworkin 2009). However, other scholars have found no association between sexual activity and marital expectations (Manning et al. 2007), suggesting that more work is needed to fully understand the complexities of this relationship.

The sexual experience of emerging adults may alter the way they view future relationship formation. Salts and Seismore (1994) found that college freshman who self-identified as virgins were less likely to say they would miss single life once married and more likely to not anticipate adjustment problems in their future marriages. Young adults who engage in high-risk sexual behavior have also been shown to be less likely to endorse values around concern for others (Chernoff and Davison 1999). It is possible that premarital sexual activity may be related to attitudes that might make it more likely that an emerging adult may consider divorce in the future. However, to date few studies have examined whether sexual behaviors affect global attitudes toward marriage, such as the belief that marriage is good for society or how important getting married is to an individual. These attitudes in turn may have effects on subsequent marital outcomes.

Attitudes Toward Cohabitation

Research has conclusively found that cohabitation is not similar to marriage. Couples that cohabit are less stable, less committed and less satisfied than married couples (DeMaris and Rao 1992; Dush et al. 2003; Kline et al. 2004). Most marriages today are preceded by cohabitation (Martin et al. 2001), and a large proportion of young adults view cohabitation as a good way to test the relationship prior to marriage (Larson 1988; Martin et al. 2003) or as a developmental step toward marriage (Manning et al. 2007). For some, cohabitation is becoming viewed as an acceptable alternative to marriage (Bumpass et al. 1991; Thornton et al. 1995).

Although the research literature on cohabitation is extensive, less work has been done on how attitudes toward cohabitation are linked to sexual behavior. Recent research has suggested that increased sexual activity may be associated with more positive attitudes toward cohabitation (Manning et al. 2007; Cunningham and Thornton 2005). Manning et al. (2007) also found that traditional views toward sexual activity were negatively associated with expectations to cohabit. Emerging adults with more permissive attitudes toward sexual activity may be more likely to consider cohabitation as a viable option for future couple formation.

Contexts and Moderators

Researchers have noted that sexual activity within emerging adulthood takes place within a wide variety of relational settings and contexts (Christopher and Sprecher 2000; Furstenberg 2000) and that emerging adult sexual behavior is related to demographic characteristics. Religiosity, for example, is strongly associated with emerging adults’ sexual behavior (Beckwith and Morrow 2005; Lefkowitz et al. 2004; Mahoney 1980). Dating opportunities can also have a large effect on sexual behavior and may be the reason why some young adults remain virgins (Woody et al. 2000). Despite observations from scholars that much of the research on predictors and modifiers of sexual behavior during emerging adulthood lack a strong theoretical framework (Christopher and Sprecher 2000), any investigation of sexual behavior must acknowledge the role that intervening variables may play in relationships found between sexual behavior and other factors.

Research has suggested that religiosity and dating status have a particularly strong impact on sexual behavior (Beckwith and Morrow 2005; Lefkowitz et al. 2004; Mahoney 1980; Roche and Ramsbey 1993) and couple formation attitudes (Lye and Waldron 1997; Pearce and Thornton 2007). Religion can have a profound impact on the timing of couple formation (Lehrer 2004), and various religious teachings likely impact the beliefs emerging adults have regarding family life (Carroll et al. 2000). Dating status has also been linked to both sexual behavior (Dorius et al. 1993; Roche and Ramsbey 1993) and couple formation attitudes (Crissey 2005), with emerging adults in serious relationships reporting higher levels of sexual behavior and expectations to marry.

Focus of the Study

Despite evidence that attitudes and behaviors are interconnected, little research has looked directly at the possible links between couple formation attitudes and sexual behavior and no research has sought to investigate how other characteristics of emerging adults may impact those links. Attitudes toward couple formation may impact sexual behavior in a variety of ways. Likewise, sexual activity may change attitudes toward couple formation. This study represents a focused attempt to understand how sexual behavior is related to couple formation attitudes among emerging adults and also a first attempt to explain how other variables such as religiosity and dating status may moderate that relationship. In this study, we expand the literature by examining how sexual behavior, specifically looking at group differences between abstainers and sexually experienced emerging adults, is related to both attitudes toward marriage and cohabitation. In this study, we also investigate how other developmental contexts such as religiosity and dating status might alter those relationships.

Theoretical Framework

In order to frame this investigation of how sexual behavior and couple formation attitudes are related, this study draws both on marital horizon theory (Carroll et al. 2007) and on the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen 1991) to frame its research questions and interpretation of results.

Marital horizon theory suggests that emerging adulthood can be conceptualized through a family formation lens and that behaviors during emerging adulthood are impacted by the orientation an emerging adult has toward marriage (Carroll et al. 2007). A person’s marital horizon has been conceptualized by Carroll et al. (2007) as having three components, criteria for marriage readiness, the importance of marriage, and the desired timing of marriage. All three of these components are likely related to how emerging adults plan and carry out their lives. It is within this framework that attitudes and behaviors are constantly shifting as emerging adults alter their life plans based on their present experience.

Within the broader context of martial horizon theory, we use the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen 1991) to inform our interpretation of the interaction between sexual behavior and couple formation attitudes. The theory of planned behavior specifies that a reciprocal relationship exists between attitudes and behaviors and that behavior can be predicted by attitudes and intentions toward a particular behavior. Attitudes and thoughts toward a given behavior will lead to decisions on whether one will engage in that behavior. Engaging in a behavior will in turn either increase or decrease the likelihood of participating in the behavior in the future (Ajzen 1991).

The theory of planned behavior also emphasizes that it is important to look at the reciprocal effects of attitudes and behaviors. Throughout the life course, individuals are constantly monitoring and changing their attitudes and values regarding behaviors as they learn from their own personal experience with those behaviors. Attitudes are continually shaped by behavior as experience either diminishes or reinforces them.

Research Questions

This study examines whether sexual activity is related to attitudes toward marriage and cohabitation. Within this framework, this study will address two broad inquires. First, we will explore whether the group differences exist on measures of relational attitudes between sexual abstinent and sexually experienced emerging adults in order to assess whether any relationship exists. Because attitudes toward couple formation are likely to influence behavior and also be influenced by behavior, no causal direction is proposed. Secondly, we will begin to investigate the mechanisms behind any links between sexual behavior and couple formation attitudes. We use both religiosity and dating status to look at how other contextual variables might moderate the relationship between couple formation attitudes and sexual behavior. In this study, we chose to focus on religiosity and not religious affiliation. Religious activity may vary widely within each religious denomination (Lehrer 2004), suggesting that religiosity may be a more salient factor to consider when assessing religion’s impact on couple formation attitudes. Research has also found that for emerging adults, participation in religious activities is a stronger predictor of couple formation attitudes than religious affiliation (Pearce and Thornton 2007). By using these two variables recognized as important factors when looking at sexual behavior and couple formation attitudes, this study will help illustrate how the links between these two variables may be moderated and altered by many systemic factors. The study will address the following specific research questions:

-

1.

Do emerging adults who have had sexual intercourse hold different attitudes toward marriage and cohabitation than emerging adults who have not had sexual intercourse?

-

2.

For emerging adults who have had sexual intercourse, is there a relationship between greater sexual activity and attitudes toward marriage and cohabitation?

-

3.

Does religiosity and dating status influence any differences found between emerging adults who have had sexual intercourse and those who have not?

Methods

Data Collection

This study is a secondary analysis of data collected as a part of a project [Project R.E.A.D.Y. (Researching Emerging Adults Developmental Years)]. Data were collected via an Internet survey from multiple universities across the United States (a small, private liberal arts college and a medium-sized, religious university on the East coast; two large, Midwestern public universities; a large; and a large, public university on the West Coast). Instructors from these universities were asked to distribute a handout to their classes, which included a brief description of the study as well as the website the student could go to in order to complete the survey. All surveys were completed online. Once on the website, students were asked to provide their parents’ email addresses. Parents were then contacted to complete a companion parent’s survey. This study will utilize only the student data. Students were compensated through three mechanisms left to the discretion of the instructor and research team. This compensation included extra credit, name being included in a prize drawing, and monetary compensation totaling up to $40. There were no differences found on study variables or relationships across data collection sites.

The sample for this study consisted of 990 non-married, non-cohabiting individuals between the ages of 18–21 (M = 19.72, SD = 1.39). The sample was 71.9% female (n = 712) and 28.1% male (n = 278). This heavy skew toward females is likely due to the fact that recruiting was done in mostly social science departments that are predominately female. The sample was predominately white (80%).

Measures

Attitudes Toward Marriage

Attitudes toward marriage were assessed using four items from a larger general attitude survey. Participants selected how much they agreed or disagreed with the following statements on a 6-point, forced-choice scale (1 = very strongly disagree to 6 = very strongly agree): “All in all, there are more advantages to being single than to being married,” “Marriage is a lifetime relationship and should never be ended except under extreme circumstances,” “I would like to be married now,” and “Being married is a very important goal for me.” Reliability statistics were calculated to determine whether marriage attitudes would be better assessed by creating a scale. Items were only weakly to moderately correlated, with correlations ranging from r = .087 to r = .320. Alpha scores were also relatively low with the highest being α = .516. Therefore, the four items were analyzed separately.

Attitudes Toward Cohabitation

Attitudes toward cohabitation were assessed using two items, both measured on the same 6-point scale as the attitudes toward marriage. Participants indicated their agreement or disagreement with the statements: “It is alright for a couple to live together without planning to get married” and “It is alright for an unmarried couple to live together as long as they have plans to marry.” These two items were analyzed separately. Emerging adults may have differing attitudes toward cohabitation based on the future plans of the couple.

Sexual Experience

Sexual experience was measured with one yes/no item: “Have you ever had sexual intercourse?” The number of sexual partners was measured using two items: “With how many partners have you had sexual intercourse in the past 12 months?” and “With how many partners have you had sexual intercourse?”

Religiosity

Religiosity was measured by combining four items drawn from the Religious Life Inventory (Batson et al. 1993) addressing various aspects of religious practice and belief. These items included questions asking about daily praying, importance of faith to personal identity, attendance at religious services, and overall importance of faith. Three items were assessed on a 4-point, forced-choice scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). These items were “My religious faith is extremely important to me,” “I pray daily,” and “My faith is an important part of who I am as a person.” The last item, “How often have you attended religious/spiritual services in the past 12 months?” was measured on a 5-point scale with higher numbers indicating more attendance at religious or spiritual services. These items were summed to create a religiosity score. All items were moderately or highly correlated (ranging from .593 to 0.853) with the two importance items being the most highly correlated. All reliability statistics were in the acceptable ranges (α = .853).

Dating Status

Dating status was measured by asking participants “Which best describes your current dating status?” Possible responses were not dating at all, casual/occasional dating, have boyfriend/girlfriend (in an exclusive relationship), engaged, or committed to marry, and married. Responses to this item were recoded into a new variable combining emerging adults in casual and serious dating relationships into one dating category.

Data Analysis Plan

Preliminary analyses showed that age and race were significantly related to sexual behavior and several couple formation attitudes. This has been found in previous research (Day 1992; Haffner 1997). Therefore, age and race were used as controls in all analyses. Age was measured by having participants indicate their age on the survey. Race was assessed with one item asking participants to pick the racial category that best described them, which was subsequently dummy coded (0 = white, 1 = non-white).

Data analysis was completed in several steps. First, multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) techniques were used to determine whether there were mean differences on couple formation attitude items between emerging adults who have had sexual intercourse and those who have not. Second, for emerging adults who have had sexual intercourse, partial correlations were computed in order to see whether there was a relationship between the number of sexual partners and couple formation attitudes. Third, religiosity’s effect on the relationship between sexual behavior and couple formation attitudes was assessed in the following way: Using a median split, the sample was divided into low and high religiosity groups. Religiosity (high/low) group and sexual behavior (yes/no) were then used as factors in two-way MANCOVA models focusing on the interaction between religiosity and sexual behavior on attitudes toward couple formation. Finally, dating status was included in three-way MANCOVAs to see whether it altering any of the relationships found in previous analyses.

Results

Descriptive Findings

The sample showed trends in sexual activity and couple formation attitudes similar to those found in previous research. On average, emerging adults heavily endorsed marriage. A vast majority of the students sampled (82.3%) agreed that marriage is a lifetime relationship that should never be ended except under extreme conditions, with 29.7% very strongly agreeing with this statement. About 87.6% of the sample agreed that marriage was an important goal for them. Only 12.4% of the sample agreed with the statement “all in all, there are more advantages to being single than to being married.” Despite this high endorsement of marriage in general, it was not something that most emerging adults thought was in their near future. Only 17% of the students sampled agreed that they would like to be married now.

Endorsement of cohabitation was evenly split in the sample, leaning somewhat toward a more accepting attitude. There was very little difference depending on whether or not a couple planned to get married: 62.6% of the sample agreed that it was acceptable for couples to live together as long as they planned to get married and 59.6% agreed that cohabitation was acceptable even if the couple had no plans for marriage.

Sexual activity also followed trends found in recent research, with 60.7% of the sample having engaged in sexual intercourse at some point in their life. This figure is slightly lower than some previous studies but might also be indicative of the slightly younger college sample used in this study. Students on average had 2.64 lifetime sexual partners.

The sample tended to be balanced in terms of religiosity. On a scale from 1 to 4, the average score across the sample on the religiosity scale was 2.25. Most students sampled were Christian (75%), with Catholics representing the largest single denomination (40%) and 9% of the sample reported no religious affiliation.

Gender analyses revealed that women were more likely to agree that marriage was an important goal and less likely to believe there were more advantages to being single than to being married than men. Women were also less likely to agree that cohabitation was acceptable if the couple was not planning on getting married. Preliminary analyses indicated that all relationships found in this study remained stable across gender. Due to this finding, gender was not used as a control for subsequence analyses in order to retain the most parsimonious model.

Sexual Activity and Marital Attitudes

MANCOVAs and post hoc analyses controlling for age and race revealed few differences on the four marital attitude items depending on sexual experience (Table 1). Multivariate results were not significant [F(4, 858) = 1.03, p = .39]. Only one of the items, marriage being an important goal, was significant on the univariate level [F(1, 864) = 5.50, p < .05]. In this case, those emerging adults who have had sexual intercourse were more likely to agree that marriage was an important goal.

After removing sexually abstinent young adults, a similar result was obtained for correlations between sexual experience and marital attitudes. After controlling for age and race only one significant correlation was found between the marital attitude items and the number of lifetime sexual partners or the number of sexual partners in the last 12 months. More sexual partners in the last 12 months was associated with more agreement with the item, “all in all there are more advantages to being single than to being married.” (r = .083, p < .05). All other partial correlations were not significant.

Sexual Activity and Cohabitation Attitudes

MANCOVA results revealed that there were significant mean differences on cohabitation attitude items based on sexual experience with F(2, 860) = 25.92, p < .001. Univariate F tests were significant for both attitude items (see Table 2). Emerging adults who have had sexual intercourse were more likely to agree that living together before marriage was acceptable regardless of marital plans. Partial correlations between the number of sexual partners and attitudes toward cohabitation produced one significant result. A significant positive correlation was found between an individual’s total number of lifetime sexual partners and their endorsement of the item “it is alright for an unmarried couple to live together as long as they have plans to marry” (r = .133, p < .01).

Effect of Religiosity

As expected, preliminary analyses indicated that religiosity was significantly correlated (p < .01) with all couple formation attitude variables. Religiosity was positively correlated with agreement that marriage is an important goal (r = .186), marriage is a lifetime relationship (r = .207), and desire to marry now (r = .175). Religiosity was negatively correlated to belief that there are more advantages to being single than to being married (r = −.105). Religiosity was also negatively correlated with agreement on both cohabitation attitudes regardless of if there were plans for marriage (r = −.367) or not (r = −.557).

As shown in Table 3, a two-factor MANCOVA for marital attitude items indicated significant main effects for both sexual experience [F(4, 854) = 2.91, p < .05] and religiosity [F(4, 854) = 13.51, p < .001]. The interaction between religiosity and sexual experience was not significant. Post hoc analyses indicated that most of sexual experience’s main effect was from a significant relationship between sexual experience and the item “being married is a very important goal for me.” Additionally, a significant mean difference was detected based on sexual experience on the item related to marriage being a lifelong commitment [F(1, 862) = 5.60, p < .05]. Significant mean differences were detected on all marital attitude items based on religiosity group.

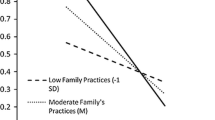

As also seen in Table 3, a two-factor MANCOVA looking at cohabitation items produced strong main effects [sexual experience, F(2, 856) = 11.98, p < .001; religiosity, F(2, 856) = 92.68, p < .001] and a significant interaction [F(2, 856) = 15.08, p < .001]. Emerging adults who had engaged in sexual intercourse and those with low religiosity were both significantly more likely to endorse cohabitation. However, sexual experience had a much higher influence on emerging adults with high religiosity. With regard to the item asking if cohabitation was alright as long as the couple planned on marrying, those in the low religiosity group were similar in their agreement with this statement regardless of if they have had sexual intercourse (M = 4.00) or not (M = 4.10), while those in the high religiosity group saw a large increase in agreement from the group that had not had sexual intercourse (M = 2.97) to the group that has had sexual intercourse (M = 3.75). For the item in which the couple did not plan on marrying, the pattern was virtually identical, with those in the low religiosity group not differing much depending on if they have had sexual intercourse (M = 4.08) or not (M = 4.06), while those in the high religiosity group became much more accepting of cohabitation from the no sexual experience group (M = 2.67) to those who have had sexual intercourse (M = 3.33).

Effect of Dating Status

A series of independent sample t-tests were first computed to see if dating status was related to differing couple formation attitudes. Emerging adults who were dating were more likely to agree that marriage was an important goal for them (p < .01) and that they would like to be married now (p < .01). Emerging adults who were currently dating were also less likely to agree that all in all there are more advantages to being single than to being married (p < .01). Emerging adults currently dating were also more likely to have had sexual intercourse (p < .001).

To assess if dating status altered the relationship between sexual behavior, religiosity and couple formation attitudes, three-way MANCOVAs were computed for both marital items and cohabitation items. For martial items, sexual experience, religiosity, and dating status each produced a significant main effect. Emerging adults who had engaged in sexual intercourse, were highly religious and were currently dating were all more likely to have more positive attitudes toward marriage. A significant interaction was also detected between sexual experience and dating status [F(4, 821) = 2.36, p < .05]. Post hoc analysis revealed that a significant interaction existed between dating status and sexual experience for the item “being married is an important goal for me.” [F(1, 833) = 6.43, p < .05]. In this case, having had sexual intercourse had a larger effect for emerging adults not currently dating. Emerging adults who were not dating were significantly more likely to agree that marriage was an important goal if they had engaged in sexual intercourse (M = 4.91) compared to those who had not (M = 4.51). Emerging adults that were currently dating had high levels of agreement regardless of if they had engaged in sexual intercourse (M = 4.95) or not (M = 5.04). The three-way interaction between religiosity, dating status, and sexual experience was not significant.

For attitudes toward cohabitation, the inclusion of dating status had little effect on the results from the previous model. While sexual experience and religiosity continued to produce significant main effects, dating status did not [F(2, 823) = 1.15, p = .316]. All interactions involving dating status were also not significant.

Discussion

This study found little evidence of a link between sexual behavior and attitudes toward marriage. Sexual intercourse in the past and the number of sexual partners did not seem to impact attitudes toward marriage with the exception of the item “being married is a very important goal for me.” Differences with previous studies may be based on measures. Salts and Seismore (1994) used items from Hill’s (1951) Favorableness of Attitudes toward Marriage Scale (FAMS), which addressed issues of readiness to marry and attitudes toward adjustment to married life, whereas the present study’s items more heavily tapped favorableness toward marriage as an institution. It is possible that emerging adults who have had sexual intercourse may feel personally less ready for marriage and more concerned about the adjustment that marriage will require, but still continuing to value marriage as an institution. Salts’ study also utilized a sample comprised of only college freshman, whereas this present sample extended over the college years. In both studies, most emerging adults viewed marriage as a goal and valued it as a lifetime relationship, yet did not see getting married as a proximal event.

In the current study, sexual experience was not related to less favorable attitudes toward marriage. The marital attitude items used in this study best capture the importance of marriage component of martial horizon theory (Carroll et al. 2007). It is possible that other areas of marital horizon, such as criteria for marriage readiness and the desired timing of marriage, are more important factors in determining sexual decisions during emerging adulthood. Willoughby and Dworkin (2009) have found that the desired timing of marriage is associated with sexual behavior in men and women.

The link between sexual behavior and attitudes toward cohabitation in the present study was strong, replicating earlier findings (Manning et al. 2007). Emerging adults who have had sexual intercourse were much more likely to endorse cohabitation, regardless of if the couple was planning on getting married. It is likely that this strong relationship is attributed to the fact that emerging adults who engage in sexual activity are more likely to have more permissive attitudes toward sexual activity and other areas of their lives. However, this logic would suggest that those emerging adults who engaged in more sexual activity would be even more endorsing of cohabitation. The results did not lend strong support to this notion as results indicated that the number of sexual partners was not related to changes in attitudes toward cohabitation with only one exception. Overall, results suggest that the important distinction was not how many sexual partners a person had but if they ever had sexual intercourse.

Why would sexual behavior be so strongly linked to attitudes toward cohabitation and not to marriage? One possible explanation is that emerging adults who are sexually active may be much more likely to be in serious long-term committed relationships and hence more likely to be considering cohabitation. Since emerging adults now typically delay marriage until after emerging adulthood, those in dating relationships during this period may consider cohabitation the next step in the relationship. Results indicated that emerging adults in dating relationships were more likely to have engaged in sexual intercourse but were not more likely to approve of cohabitation. One possible explanation of this finding is that dating status is not a simple dichotomous choice for emerging adults. A wide variety of dating and relationship types may impact the relationship between sexual behavior and cohabitation attitudes differently. A more formal exploration of dating status is needed before the exact pathways between sexual behavior and cohabitation can be established.

Another reason for this study’s results may be that as emerging adults become sexually active with their partners, they may begin to consider cohabitation as the next step in the logical progression of their relationship. This would fit results from previous work suggesting that sexual activity is strongly related to expectations to cohabitate and less associated with expectations to marry (Manning et al. 2007). Because cohabitation may feel more proximate to many emerging adults, their attitudes may be more malleable as they actively negotiate their beliefs about it. Because marriage is likely a far-off ideal for many of these young adults, attitudes toward marriage may be less influenced by current behavior. This pattern may be a possible casual pathway between sexual activity and marital instability. It is possible that emerging adults who have sexual intercourse are more likely to cohabitate, a living arrangement that research suggests leads to more negative marital outcomes (DeMaris and Rao 1992; Dush et al. 2003). The mediation of cohabitation on the relationship between sexual activity and divorce may account for some findings that suggest that when premarital sex is taken into account, cohabitation no longer becomes a significant predictor of divorce (Teachman 2003).

Although prior research has found links between religion, sexual behavior, and couple formation attitudes, this study uniquely showed that religiosity may be an important factor to consider when looking at how behavior affects couple formation attitudes. The effect of sexual experience on couple formation attitudes differed depending on the religiosity of the emerging adult. Those in the low religiosity group differed significantly on their agreement with the item, “being married is a very important goal for me,” depending on their sexual experience. Those in the high religiosity group did not significantly differ on any of the marital attitude items based on their sexual experience. Although there seems to be little evidence overall that sexual behavior is related to marital attitudes, the sexual behavior of emerging adults who have low religiosity may have an impact on how they view marriage.

Results for attitudes toward cohabitation seemed to suggest the opposite pattern. While religiosity produced a significant main effect on its own, the interaction between religiosity and sexual experience indicated that sexual experience has a larger impact on the acceptance of cohabitation for emerging adults with high religiosity. For both cohabitation items the gap between high and low religiosity groups was greatly diminished for the group that had engaged in sexual intercourse. Although the low religiosity group did not differ based on sexual experience, the emerging adults in the high religiosity group who had engaged in sexual intercourse were much more accepting of cohabitation than the group that had not had sexual intercourse. Having had sexual intercourse brought those in the high religiosity group much closer on average to those in the low religiosity group.

What this pattern suggests is that sexual activity may lead to a marked increase in positive attitudes toward marriage for less religious emerging adults and an increase in acceptance of cohabitation for highly religious emerging adults. Although sexual behavior had an effect on couple formation attitudes, which type of attitudes it affected was moderated by religiosity. Since sexual activity is not condoned by many religious emerging adults, having sexual intercourse may lead them to adopt less traditional attitudes toward other areas of their life, such as attitudes toward cohabitation. Previous studies have suggested that emerging adults with negative views toward a given behavior, such as sexual activity, may shift those views after engaging in behavior that contradicts those views in order to resolve internal cognitive contradictions between beliefs and actions (Makela 1997; Von der Gruen and Forsyth 1993). Highly religious emerging adults who engage in sexual activity may resolve this cognitive dissonance by becoming more accepting of couple formations that involved committed sexual activity outside the marital relationship.

Emerging adults with low religiosity may not have the same disproval of sexual activity. For them, links between sexual activity and couple formation attitudes may exist due to natural relationship progression. As sexual activity is more likely to occur in committed relationships, low religiosity emerging adults who have sexual intercourse may be in committed relationships and begin to think more favorably about marriage as they plan for their future.

These patterns reveal that the relationship between sexual behavior and couple formation attitudes is not a simple casual relationship. Many factors likely influence the strength and direction of the relationship. The examples of religiosity and dating status illustrate the importance of taking a contextual approach in order to understand why premarital sexual behavior is linked to marital instability. Although the focus of this study was not religiosity or dating status, the inclusion of these variables and the ensuing results show the need for future research investigating sexual behavior and couple formation attitudes to develop conceptual models that incorporate these variables.

Limitations

One clear limitation of this study is its use of a strictly college sample. The “forgotten generation” (William and Grant Foundation Commission on Work, Family, and Citizenship 1988) of non-college-bound emerging adults was not represented in this sample and generalizations should not be made to all emerging adults. Results may only be indicative of college students who live in a very unique dating and sexual environment. This study also drew heavily from social science classrooms that were largely female. This might skew the data in a certain direction and caution should be made when generalizing the results even though gender comparisons revealed relationships between sexual behavior and couple formation attitudes remains constant across gender. The cross sectional nature of this data also limits the ability to interpret the results. Sexual behavior may lead to changes in couple formation attitudes, but it is also possible that attitudes help predict which emerging adults will engage in sexual activity.

Results of this study should also be taken with caution due to the limitations of self-report instruments, particularly regarding sexual activity. Young adults may be less likely to report honestly about sensitive topics such as sexual behavior (Johnson and Richter 2004). This may lead to underreporting of sexual activity and biased results.

Future Directions

This study serves as an important step in the exploration on how attitudes toward marriage and other couple formations are related to sexual behavior during emerging adulthood. One important area of future work is the exploration of how attitudes and behaviors change over time and how these changes might be related to developmental contexts. Students in this sample are in a developmental period marked by continued identity development and value formation. It is likely that their attitudes toward couple formation, religion and risk behavior may change over the course of their college years. The impact of religion may be particularly prone to change as emerging adults seek to develop their own religious identity separate from the religious identity of their family of origin (Pearce and Thornton 2007). College in and of itself may provide a context in which attitudes and behaviors are shifting as emerging adults both interact with peers from diverse backgrounds and receive more education. As future studies explore the patterns found in this study over time, it is likely that the associations and patterns between variables will shift and change due to continued individual and relational development.

Future studies should also work to more clearly determine the magnitude and influence of the relationships found in this study. Dating and other relationship variables should also be the focus of future studies looking at behavior and couple formation attitudes to determine what, if any, effect they have. Other important factors that likely influence couple formation attitudes and behavior, such socioeconomic status, should also be the focus of future studies. Finally, religion may have a unique effect on the relationship between couple formation attitudes and behavior; future studies should explore how this effect operates and how it may change over the lifespan.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

Arnett, J. J. (1997). Young people’s conceptions of the transition to adulthood. Youth and Society, 29, 1–23.

Arnett, J. J. (1998). Risk behavior and family role transitions during the twenties. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 27(3), 301–320.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the early twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480.

Batson, C. D., Schoenrade, P., & Ventis, W. L. (1993). Religion and the individual. New York: Oxford University Press.

Beckwith, H. D., & Morrow, J. A. (2005). Sexual attitudes of college students: The impact of religiosity and spirituality. College Student Journal, 39(2), 357–367.

Bumpass, L. L., Sweet, J. A., & Cherlin, A. (1991). The role of cohabitation in declining rates of marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53, 913–927.

Carroll, J. S., Linford, S. T., Holman, T. B., & Busby, D. M. (2000). Marital and family orientations among highly religious young adults: Comparing latter-day saints with traditional Christians. Review of Religious Research, 42, 193–205.

Carroll, J. S., Willoughby, B., Badger, S., Nelson, L. J., Barry, C. M., & Madsen, S. (2007). So close, yet so far away: The impact of varying marital horizons on emerging adulthood. Journal of Adolescence Research, 22(3), 219–247.

Chernoff, R. A., & Davison, G. C. (1999). Values and their relationship to HIV/AIDS risk behavior among late-adolescent and young adult college students. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 23(5), 453–468.

Christopher, F. S., & Sprecher, S. (2000). Sexuality in marriage, dating, and other relationships: A decade review. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 999–1017.

Côté, J. (2000). Arrested adulthood: The changing nature of maturity and identity in the late modern world. New York: New York University Press.

Crissey, S. R. (2005). Race/ethnic differences in the marital expectations of adolescents: The role of romantic relationships. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 697–709.

Cunningham, M., & Thornton, A. (2005). The influence of union transitions on white adults’ attitudes toward cohabitation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 710–720.

Day, R. D. (1992). The transition to first intercourse among racially and culturally diverse youth. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 54(4), 749–762.

DeMaris, A., & Rao, V. (1992). Premarital cohabitation and subsequent marital stability in the United States: A reassessment. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 54(1), 178–190.

Dorius, G. L., Heaton, T. B., & Steffen, P. (1993). Adolescent life events and their association with the onset of sexual intercourse. Youth & Society, 25(1), 3–23.

Dush, C. M., Cohan, C. L., & Amato, P. R. (2003). The relationship between cohabitation and marital quality and stability: Change across cohorts? Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 539–549.

Furstenberg, F. F. (2000). The sociology of adolescence and youth in the 1990s: A critical commentary. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 896–910.

Haffner, D. W. (1997). What’s wrong with abstinence-only sexuality education programs? SIECUS Report, 25, 9–13.

Heaton, T. B. (2002). Factors contributing to the increasing marital stability in the United States. Journal of Family Issues, 23(3), 392–409.

Hill, R. J. (1951). Attitudes toward marriage. Unpublished Master’s Thesis. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University.

Johnson, P. B., & Richter, L. (2004). Research note: What if we’re wrong? Some possible implications of systematic distortions in adolescents’ self-reports of sensitive behaviors. Journal of Drug Issues, 34(4), 951–970.

Kahn, J. R., & London, K. A. (1991). Premarital sex and the risk of divorce. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53(4), 845–855.

Kline, G. H., Stanley, S. M., Markman, H. J., Olmos-Gallo, P. A., Peters, M. S., Whitton, S. W., et al. (2004). Timing is everything: pre-engagement cohabitation and increased risk for poor marital outcomes. Journal of Family Psychology, 18(2), 311–318.

Kreider, R.M. (2005). Number, timing, and duration of marriages and divorces: 2001. Current Population Reports, P70-97. U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC.

Ku, L., Sonenstein, F. L., Lindberg, L. D., Bradner, C. H., Boggess, S., & Pleck, J. H. (1998). Understanding changes in sexual activity among young metropolitan men: 1979–1995. Family Planning Perspectives, 30(6), 256–262.

Larson, J. H. (1988). The marriage quiz: College students’ beliefs in selected myths about marriage. Family Relations, 37, 3–11.

Larson, J. H., & Holman, T. B. (1994). Premarital predictors of marital quality and stability. Family Relations, 43, 228–237.

Lefkowitz, E. S., Gillen, M. M., Shearer, C. L., & Boone, T. L. (2004). Religiosity, sexual behaviors, and sexual attitudes during emerging adulthood. The Journal of Sex Research, 41(2), 150–159.

Lehrer, E. L. (2004). Religion as a determinant of economic and demographic behavior in the United States. Population and Development Review, 30(4), 707–726.

Lye, D. N., & Waldron, I. (1997). Attitudes toward cohabitation, family, and gender roles: Relationships to values and political ideology. Sociological Perspectives, 40(2), 199–225.

Mahoney, E. R. (1980). Religiosity and sexual behavior among heterosexual college students. The Journal of Sex Research, 16(1), 97–113.

Makela, K. (1997). Drinking, the majority fallacy, cognitive dissonance and social pressure. Addiction, 92(6), 729–736.

Manning, W. D., Longmore, M. A., & Giordano, P. C. (2007). The changing institution of marriage: Adolescents’ expectation to cohabit and to marry. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 559–575.

Martin, P. D., Martin, D., & Martin, M. (2001). Adolescent premarital sexual activity, cohabitation, and attitudes toward marriage. Adolescence, 36, 601–609.

Martin, P. D., Specter, G., Martin, D., & Martin, M. (2003). Expressed attitudes of adolescents toward marriage and family life. Adolescence, 38, 359–367.

McLanahan, S. (2004). Diverging destinies: How children are faring under the second demographic transition. Demography, 41, 607–627.

Meschke, L. L., Zweig, J. M., Barber, B. L., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Demographic, biological, psychological, and social predictors of the timing of first intercourse. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 10(3), 315–338.

Michael, R. T., Gagnon, J. H., Laumann, E. O., & Kolata, G. (1995). Sex in America: A definitive survey. New York: Warner Books.

Netting, N. S., & Burnett, M. L. (2004). Twenty years of student sexual behavior: Subcultural adaptations to a changing health environment. Adolescence, 39, 19–38.

Paul, E. L., McManus, B., & Hayes, A. (2000). “Hookups”: Characteristics and correlates of college students’ spontaneous and anonymous sexual experiences. The Journal of Sex Research, 37(1), 76–88.

Pearce, L. D., & Thornton, A. (2007). Religious identity and family ideologies in the transition to adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69, 1227–1243.

Roche, J. P., & Ramsbey, T. W. (1993). Premarital sexuality: A five-year follow-up study of attitudes and behavior by dating stage. Adolescence, 28, 67–81.

Salts, C. J., & Seismore, M. D. (1994). Attitudes toward marriage and premarital sexual activity of college freshman. Adolescence, 29, 775–780.

Shulman, S., & Seiffge-Krenke, I. (2001). Adolescent romance: Between experience and relationships. Journal of Adolescence, 24(3), 417–428.

Teachman, J. (2003). Premarital sex, premarital cohabitation, and the risk of subsequent marital dissolution among women. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 444–455.

Thornton, A., Axinn, W. G., & Teachman, J. D. (1995). The influence of school enrollment and accumulation on cohabitation and marriage in early adulthood. American Sociological Review, 60(5), 762–774.

Treas, J. (2002). How cohorts, education, and ideology shaped a new sexual revolution on American attitudes toward nonmarital sex, 1972–1998. Sociological Perspectives, 45, 267–283.

Von der Gruen, W. O., & Forsyth, D. R. (1993). Interpersonal determinants of attitude change following counterattitudinal behavior. Current Psychology, 15(2), 147–157.

Wells, B. E., & Twenge, J. M. (2005). Changes in young people’s sexual behavior and attitudes, 1943–1999: A cross-temporal meta-analysis. Review of General Psychology, 9(3), 249–261.

White, S. D., & DeBlassie, R. R. (1992). Adolescent sexual behavior. Adolescence, 27(105), 183–192.

William, T., & Grant Foundation Commission on Work, Family, and Citizenship. (1988). The forgotten half: Non-college bound youth in America. Washington, DC: William T. Grand Foundation.

Willoughby, B., & Dworkin, J. D. (2009). The relationships between emerging adults’ expressed desire to marry and frequency of participation in risk behaviors. Youth & Society, 40, 426–450.

Woody, J. D., Russel, R., D’Souza, H. J., & Woody, J. K. (2000). Adolescent non-coital sexual activity: Comparisons of virgins and non-virgins. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy, 25, 261–268.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Willoughby, B.J., Carroll, J.S. Sexual Experience and Couple Formation Attitudes Among Emerging Adults. J Adult Dev 17, 1–11 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-009-9073-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10804-009-9073-z