Abstract

The protective effects of social support for caregiver mental health are well documented, however the differential impact of support providers (partner, child, family, siblings, friends, professionals) and types (perceived, received) remain unclear. Observational data from 21 independent studies, involving a pooled sample of 2273 parents, stepparents and grandparents of children (aged ≤ 19) with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) were examined. Pearson’s r, publication bias and heterogeneity were calculated using random effects modelling. Significant associations were noted between lowered depressive symptoms and positive sources of support, regardless of support type. Parental mental health can be enhanced by strengthening close personal relationships alongside connections with formal support services. Longitudinal research is needed to explore support need and perceived helpfulness over time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Parenting a child with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) can differentially impact on mental health. Whilst caregiving can be rewarding, families living with ASD are susceptible to experiencing mental health problems, particularly depression (Bitsika et al. 2013; Zablotsky et al. 2013). Concerningly, parental depression can adversely impact on a child’s core ASD symptoms (Zhou et al. 2019). From an ecological systems perspective, the social support—including emotional, psychological and physical comfort—provided by others plays a key role in facilitating mental health (Bronfenbrenner 1977, 1986). Social support and assistance is particularly critical for those parents who are still navigating the service delivery system following their child’s diagnosis (McIntyre and Brown 2018). The relationship between social support and mental health appears to be reciprocal: depression among adults, in general, can erode one’s social support network—whereas social support offers relationships that can help to reduce feelings of helplessness, isolation, and depression (Gariépy and Honkaniemi 2016). Moreover, with better mental health, comes richer social networks (Gariépy and Honkaniemi 2016).

Social support is, however, a complex construct characterised by different sources and actions. For parents of children with ASD, close partner or spousal relationships can buffer against depression (Benson and Kersh 2011; Timmons et al. 2016). Strong parent–child attachment, sibling adjustment, and flexibility in family rules, roles and leadership can also optimise parental mental health (Boyd 2002; Karst and Van Hecke 2012). That said, considerable variation in the quality of these individual family relationships has been noted (Meyer et al. 2011; McHale et al. 2016; Tudor et al. 2018).

The utilisation, and usefulness, of informal and formal sources of support should also be considered. Informal support provided by one’s family, along with non-family members (i.e., friends, other parents, social groups/clubs), can help reduce depression experienced by mothers of adolescents with autism—provided that this support is considered to be positive or helpful (Smith et al. 2012). Formal support provided through an agency or organisation, such as counselling and respite care, can also fulfil specific needs—although service access barriers (e.g., availability, affordability) have been identified (Taylor and Warren 2012; Whitaker 2002).

Notably, ASD research has primarily focused on perceived support—or one’s perception of the availability and quality of available supports. Less clear is the degree to which received (or enacted) assistance, often used as an indicator of the degree to which a person is integrated in a social network (Wills and Shinar 2000), impacts on caregiver wellbeing. Indeed parents have reported similar levels of wellbeing regardless of the frequency or intensity of the supports that they access (Benson 2012; Timmons et al. 2016).

In sum, the importance of social support for caregiver mental health is well established, however the literature is mixed regarding the most effective sources and types of support. The current systematic review consolidates existing knowledge on social support and protection from depression in families living with ASD. The specific aims of this review are to:

-

1.

Examine the associations between caregiver depression and social support, clustered according to support source (i.e., informal support from a partner, child with ASD, siblings, family, friends vs. formal support).

-

2.

Explore the potential moderating role of support type (i.e., perceived vs. received) on depression.

Method

Literature Search

Three electronic databases (Embase, PsycINFO, PubMed) were searched for the period between January 1980 [when autism was first recognised as a developmental disorder; American Psychiatric Association (APA 1980)] and April 13, 2020. Search terms were tailored to each database and compiled with assistance from an expert research librarian (see Table S1, Online Supplementary Material for example logic grid). Two additional studies were identified by hand-searching the reference lists of included studies and relevant reviews (reviews by: Cridland et al. 2014; Factor et al. 2019; Karst and Van Hecke 2012; Marshall et al. 2018; Meadan et al. 2010; Serrata 2012; Sim et al. 2016; Singer 2006; Smith and Elder 2010; Tint and Weiss 2016).

Study Eligibility

A protocol for this review was submitted to the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews on 25 November 2019 (ID 159853; https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/), as per the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Moher et al. 2009). Study screening was independently undertaken by the first author using Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation). A random subset of 847 (32%) full-text records was then re-checked by the second and third authors, with excellent inter-rater reliability (k = 0.99 [CI 0.96–1.00]). The single discrepant paper was discussed and consensus reached.

In addition to being published in journals, in English, eligible studies had to meet each of the following criteria:

Population

Family caregivers (e.g., parents, stepparents) of one or more children or adolescents (aged ≤ 19 years; where age ranges were not provided, the mean age plus 2 SD had to be ≤ 19 years) diagnosed with autism/autism spectrum disorders were surveyed. Autism was defined in accordance with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM; APA 1980, 1987, 1994, 2000) or the International Classification of Diseases (World Health Organisation 2004, 2018). Studies which included professional caregivers (i.e., paid support workers) or children with a diagnosis of Rett syndrome (a disorder removed from the autism category in the DSM-5; APA 2013), were ineligible.

Exposure

Studies had to include a measure of social support, broadly defined as supportive behaviours or interaction (perceived or received) from people in one’s social network. Studies that combined support sources (i.e., ‘general’ support) or which did not differentiate support type were excluded.

Outcome

Caregivers’ current-state depressive affect (as measured by self-report) or depression (as per professional evaluation) was measured. Mood or psychological distress scales not specifically designed to screen for depression (e.g., Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, General Health Questionnaire) were excluded.

Design

Eligible studies included cohort, cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. Intervention studies that provided baseline data were also eligible. Studies which only reported multivariate analyses or cross-lagged correlations were excluded, due to problems with the use of different covariates or covariates that change over time (Gibbons et al. 1993; Hamaker et al. 2015).

Data Extraction, Preparation and Organisation

Key study and sample characteristics (e.g., sample size, operationalisation of depression and social support, mean caregiver and child age) were extracted by the first author, and double-checked by the second, using a purposely designed Excel spreadsheet (see Table S2, Online Supplementary Material). Social support measures were grouped according to one of two support sources: informal supports or people in the caregiver's immediate personal social network (i.e., spouse/partner, child with ASD, siblings, family unit, friends) and formal supports or individuals from organizations or agencies that provide assistance or a service to the family (e.g., health professionals). Support measures were further categorised according to type: perceived support or subjective sense of social connectedness and/or satisfaction with support offered, and received support or actual receipt of supportive behaviour (e.g., frequency of interactions with formal support agencies). Some social support scales were rescaled so that all effect estimates described the association between the presence of (positive) social support and depressive symptoms (e.g., marital conflict reverse-coded to reflect greater harmony/reduced conflict; Timmons et al. 2016).

Risk of Bias Assessment

The methodological reporting quality of each study was assessed by the first and second authors using the QualSyst tool (Kmet et al. 2004; see Table S3 Online Supplementary Material). Each study was rated against 11 pre-specified criteria (criterion met = 2, criterion partially met = 1, criterion not met = 0, not applicable) and a summary score (ranging from 0 to 1; total score ÷ total possible score) calculated. Three items specific to interventional studies (i.e. randomisation, blinding of participants/personnel) were deemed ‘not applicable’ for the observational data in this review. Additionally, the percentage of included studies that met each criterion was determined.

Effect Size Calculations

Bi-variate correlations were entered into Comprehensive Meta-analysis software (CMA Version 3; Borenstein et al. 2013) and forest plots generated using Microsoft Excel. Random-effects modelling was used for all meta-analyses, allowing for variation in the ‘true’ effect sizes due to sampling error and methodological differences between studies (Cumming 2012). Prior to being pooled, individual r’s were transformed into Fisher’s Z scores, averaged and back-transformed into r and then weighted by each study’s inverse variance (rw). Where a study provided multiple assessments (e.g., data for mothers vs. fathers, different social support or depression measures), these data were averaged so that each study contributed a single effect estimate to any given meta-analysis (Lipsey and Wilson 2001). Confidence intervals (CIs) determined the precision of both r and rw, while p values represented statistical significance. The direction of r was standardised so that a negative value indicated that higher levels/positive aspects of support were associated with lowered depression, with correlations of 0.10, 0.20, and 0.50 representing small, medium, and large associations, respectively (Cohen 1992).

Effect size variability was examined with three statistics: Q, which analyses the ratio of observed variation to within-study error, tau (τ)—analogous to a SD of the true effect sizes, and I2 which is expressed as a percentage and represents the ratio of true effect variance to total variance in the observed effects (Borenstein et al. 2009; Higgins and Altman 2008; Higgins et al. 2003).

Various tests of publication bias were used. First, a funnel plot analysis was conducted across all included studies, followed by Egger’s regression test, Begg’s rank test and the trim-and-fill method. Orwin’s (1983) fail-safe N (Nfs) was then calculated for each subsequent meta-analysis. This statistic represents the number of hypothetical non-significant studies that would be required to reduce the individual and pooled r’s to small, non-significant effects (i.e., rw = ± 0.10). A result was considered robust to publication bias if the Nfs for a given effect exceeded the number of studies contributing data to that effect (i.e., Nfs > Nstudies).

Sensitivity and Subgroup Analyses

A sensitivity analysis was conducted to identify outlier effects in meta-analyses involving more than three studies. Here, the meta-analysis was re-run, removing one study at a time (Borenstein et al. 2009). Results were considered meaningful if the magnitude of an effect size (Cohen 1992) or its associated p value (Borenstein et al. 2009) changed. The potential moderating effect of support type (i.e., perceived vs. received) was also statistically tested, with pooled rw’s for each subgroup compared using Cochran’s Q-test and a random effects model (Borenstein et al. 2009).

Results

Study Selection

Of 5667 results initially identified, 3739 non-duplicate citations were screened by title and abstract. The full-text of 2627 potentially eligible citations were subsequently retrieved and re-screened (see Fig. 1). Lead authors of 32 studies were emailed for additional data, with 13 responding. During the screening process, 13 studies involving four overlapping samples were identified (see Table S4, Online Supplementary Material). The study that provided the most recent data, or (in cases where data from the same time period were reported), the study with the largest sample size was deemed the lead study—although all available raw data (i.e., different social support or depression measures from overlapping studies) were retained for moderator analyses. The final sample comprised of 21 independent studies.

PRISMA flowchart for study selection process (Moher et al. 2009)

Study Characteristics

Studies were typically cross-sectional in design and conducted in Western countries (Nstudies = 18), with single studies from Korea, Thailand and India (Table S5 Online Supplementary Material). Participants were recruited from local autism groups, clinics, and research registries.

Depression symptom severity was typically measured with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Nstudies = 13). A single study administered the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) for rapid assessment of both Major Depressive Disorder and Dysthymic Disorder (Charnsil and Bathia 2010). Conversely, various multi-component measures of support were used. This included 37 measures of support function (e.g., emotional, instrumental), satisfaction, and structure (e.g., network composition, frequency of contacts/interactions with others), of which half were validated. Support was rated retrospectively (e.g., support provided in the last six months; Family Support Scale) or prospectively (e.g., daily diary; Timmons et al. 2016). Two studies supplemented their self-reported data with observational codings of parent–child and play interaction (Hickey et al. 2020; Wachtel and Carter 2008). Fifteen studies included at least one measure of perceived support (e.g., relationship satisfaction), five studies used objective measures of received support (e.g., network size, geographic proximity of support) and two combined both forms.

Caregiver and Child Characteristics

The pooled sample of 2273 caregivers included parents, stepparents, adopted parents, and grandparents of a child with ASD (Mean child age 7.3; Median = 7.9; SD = 3.38; Table S6 Online Supplementary Material). Caregivers reported severe to extremely severe depressive symptoms, with 33% meeting the clinical criteria for probable depression—although few studies provided these data (Nstudies = 9; Table S5 Online Supplementary Material).

Risk of Bias Assessment

The average QualSyst score was 0.88 (Median = 0.90, SD = 0.06, range = 0.75–0.95; see Fig. 2 and Table S7 Online Supplementary Material), with all studies meeting the minimum criteria set by Kmet et al. (2004) for inclusion in this review (score ≥ 0.75). In particular, study objective(s) were stated (Criterion 1: 100% fulfilled), although many were not explicit in their design and/or method of sample selection (Criteria 2 and 3: 38% and 10% fulfilled, respectively). Caregiver characteristics (e.g., age, gender) were generally reported and outcomes clearly defined (Criteria 4 and 5: > 85% fulfilled). Most studies were also sufficiently powered to detect significant associations (i.e., minimum N required = 26, α = 0.05, power = 0.80, r = 0.50; Cohen 1992; Criterion 6: 90% fulfilled). Statistical analyses (Criterion 7: 95% fulfilled), and estimates of variance (e.g., confidence intervals, SDs; Criterion 8: 80% fulfilled) were provided for depression and/or social support, and statistical results sufficiently explained to allow replication (Criterion 9: 100% fulfilled). Finally, discussion sections were tempered in light of study limitations (Criterion 10: 100% fulfilled). In sum, studies provided adequate information regarding potential sources of methodological bias.

Proportion of included studies meeting each criterion on the QualSyst tool (Kmet et al. 2004)

Across all 21 studies, the weighted r was medium and significant: enhanced social support was related to positive mental health (rw = − 0.26 [CI − 0.35, − 0.18], p < 0.01). However, pooled rs varied greatly across the studies (range = − 0.51 to − 0.01; Q (21) = 86.63, p < 0.01, I2 = 76.92, T = 0.18). Statistical tests suggested no apparent bias in the overall effect (Egger’s p = 0.25; Begg-Mazumdar’s p = 0.29). This was confirmed by the relatively unchanged, combined effect calculated by the Trim-and-Fill method (see Fig. 3).

Social Support Source

Pooled effect estimates, grouped by support source and type, are presented in Table 1 (see Table S8, Online Supplementary Material, for individual study and outcome data).

Spouse/Partner

The association between relationship quality and caregiver depression was robust, with six of seven studies reporting significant findings: those who endorsed depressive symptoms experienced lower relationship satisfaction (N = 947 caregivers). A single, small-scale study reported a non-significant association: depressed mood, as experienced by 70 mothers of children with ASD, was not directly related to daily partner support—although relationship happiness was (Timmons et al. 2016).

Child with ASD

Of the nine studies that contributed data to this meta-analysis, five reported significant findings. The overall weighted r, based on a pooled sample of 900 parents, was small but precise (i.e., small CI) and unlikely to be characterised by publication bias (Nfs > Nstudies). Those who reported higher quality relationships and more positive interactions with their child also had lowered depression (Davis and Carter 2008; Hastings et al. 2005; Hickey et al. 2020; Neff and Faso 2015; Schwartz et al. 2018). However, four studies found no significant links between parental depression and parent–child relationship quality (García-López et al. 2016; Pruitt et al. 2016; Teague et al. 2018; Wachtel and Carter 2008).

Siblings

Only two studies examined adjustment difficulties in neurotypical siblings of children with ASD and their impact on maternal functioning, with varied results. Meyer et al. (2011) reported inverse associations between functional peer relationships, siblings’ social behaviour and parent depression (N = 70). However, Tudor et al. (2018) did not identify sibling behaviour as a significant correlate of maternal depression (N = 239). The low Nfs statistic indicates that these findings should be treated cautiously.

Family Unit

Eight studies examined different aspects of family unit functioning, as reported by 1032 caregivers, contributing to a statistically significant, small-to-medium effect. Some dispersion was evident, as indicated by the high I2 value. Greater family harmony (e.g., level of adaptability) and support were associated with lower depression in mothers and fathers of children with ASD (Ekas et al. 2010; Jellett et al. 2015; Kim et al. 2016; Pruitt et al. 2018; Singh et al. 2017). However, there was also evidence that family characteristics—including the strength of family connections and family size—were not significantly related to mothers’ psychological well-being (Benson 2012; Hickey et al. 2020; Kuhn et al. 2018; Pruitt et al. 2016).

Friends

All three studies identified support from close friends (N = 287) as a critical factor in maternal depression. Mothers who identified having friends that they could ‘talk to’ about their problems and ‘count on’ if things go wrong, scored in the lower spectrum of depression (Ekas et al. 2010; Pruitt et al. 2018; Singh et al. 2017). These findings were, however, based on limited data.

Formal Support

Of the four studies that examined the contribution of formal supports only one reported significant, small to medium effects (Taylor and Warren 2012): mothers who rated available targeted services as affordable and/or useful reported lowered depression symptoms (N = 75). Interestingly, this same study found that service accessibility was not a significant factor (Taylor and Warren 2012). Access to child care was also not directly related to caregiver depression (N = 27; Charnsil and Bathia 2010). Further research is needed to confirm these findings (Nfs < Nstudies).

Sensitivity and Subgroup Analyses

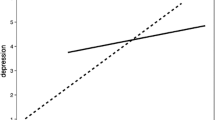

The removal of any one study did not significantly change the weighted r or p values for any of the meta-analyses. Moderator analyses revealed a significant link between perceived quality of support and reduced caregiver depression (r = − 0.30 [CI − 0.40, − 0.18], p < 0.01; I2 = 67.98, Nstudies = 15). This association was not observed for received support (r = − 0.19 [CI − 0.40, 0.04], p = 0.11; I2 = 92.80, Nstudies = 4). Both of these findings were, however, characterised by significant between-study variability. Differences between the two support constructs were not statistically significant (QB (1) = 0.71, p = 0.40).Footnote 1

Discussion

The current review, based on a pooled sample of 2273 family caregivers of children or adolescents with ASD, highlights the important role that positive social support plays in maintaining caregiver mental health. A combination of close and stable relationships, including interactions with partners, the child with ASD, and direct family were considered critical. Less clear is the impact of siblings, friends and health professionals, with little empirical research devoted to these relationships.

The couple relationship, the strongest correlate in the current review, deserves specific attention. Ecological systems theory highlights the fundamental role of the microsystem, including close and intimate relationships, in buffering the stress of parenting (Bronfenbrenner 1977, 1986). Couple resources such as relationship satisfaction, partner attitude and behaviour, are critical when parenting a child with ASD (Hartley et al. 2012; Kelly et al. 2008; Tint and Weiss 2016). Indeed, estimates of probable depression as high as 77% have been noted among single mothers of children and adults with ASD (age range: 2–26 years; Dyches et al. 2016). Previous research has found that this particular group access less social support than those living with a partner (Bromley et al. 2004). In addition to the absence of partner support, the associated lack of support from a partner’s family and friends as well as time and financial constraints may prevent lone caregivers from accessing support (McIntyre and Brown 2018). Investigating which social connections are important for those with limited family supports is a clear target for future research.

The parent–child bond also serves as an instrumental source of support. Depressed parents, in general, have reported greater irritability and hostility toward their child, thus causing strain in the parent–child relationship (Maletic et al. 2007). A combination of internal psychological processes and external factors appear to have ripple effects on caregivers’ mental health outcomes, including parents’ perceptions of the relationship (e.g., belief that the child with ASD is a source of happiness; Hastings et al. 2005) as well as observed interactions (e.g., warmth; Hickey et al. 2020).

Although the presence of other children was identified as a critical source of support for some parents (Meyer et al. 2011), this relationship is reciprocal. Maternal mental health can impact on the quality of parent–child interactions and time spent with children (Cheung and Theule 2019). However neurotypical siblings can struggle with depression and social difficulties, adding to parenting stress (Shivers et al. 2019). Longitudinal research will help to delineate the direct effects of siblings on family wellbeing, including developmental changes in parent–child interactions as children age (Green 2013).

Although small, and mostly non-significant correlations were noted between formal sources of support and caregiver depression, different patterns of results emerged depending on the support measure used. In particular, when financial need was considered (i.e., service affordability), a relationship with depression emerged (Taylor and Warren 2012). However, when examining the quantity or frequency of support accessed, there was a small and negligible relationship (Charnsil and Bathia 2010). These findings highlight the importance of service accessiblity and quality: respite care has a positive effect when it is responsive to caregivers’ needs but also provides parents a break from the demands of parenting—as opposed to extra time to work or run errands (Dyches et al. 2016).

The stronger relationship noted between perceived, rather than received support and mental health is consistent with the broader caregiver and social support literature (e.g., Del-Pino-Casado et al. 2018; Haber et al. 2007). Perhaps the subjective experience of support, moreso than the objective provision of support, is most important for caregiver mental health. Future research is needed to identify whether—and how—each source contributes to parental wellbeing, by supplementing caregiver ratings as support recipients (e.g., Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support; Zimet et al. 1988), with well-validated measures of received support (e.g., Inventory of Socially Supportive Behaviors; Barrera et al. 1981).

The findings highlight the need to address the entire family system when targeting caregiver depression. This might include multi-component interventions which involve a combination of child (e.g., behavioural training) and caregiver-focused (e.g., individual counselling) services (Karst and Van Hecke 2012; Schreiber 2011; Singer et al. 2007; Smith and Elder 2010). Mindfulness-based therapies have also demonstrated effectiveness in promoting positive parent–child interactions, addressing caregiver beliefs about the child’s role within the family, and maximising relationship satisfaction (Hartley et al. 2019). Even an improvement in the relationship skills of one member of the couple dyad, with mindfulness training, may influence the perceived quality of the relationship for both (Bluth et al. 2013). These family-level interventions could be combined with social networking opportunities and additional community or classroom-based supports to engage high-risk parents (e.g. single parents) and their children.

Limitations

Several methodological limitations were encountered in the present review. First, despite our broad inclusion of screening tests for depression and depressive disorder, a single study used a clinician-administered tool (Charnsil and Bathia 2010). There is a tendency for self-ratings of depression severity to exceed observer-ratings (Möller 2000). That said, subthreshold symptoms of depression are deemed important indicators of caregiver mental health (England and Sim 2009). Second, although we were able to minimise between-study heterogeneity by categorising studies according to support source, this resulted in some meta-analyses having a small number of studies and, potentially, limited power. Nonetheless, the findings highlight the importance of measuring multiple social support constructs to better understand caregiver functioning, including the functions that networks appear to serve (e.g., availability of someone to ‘talk to’ about personal problems) as well as the structure of these networks (e.g., number of friends).

Third, studies in this review did not capture more distal supports within the ecological system that may be important to caregiver outcomes (Tint and Weiss 2016). In particular, a strong culture of parent-school engagement (e.g., provision of a modified curriculum, teachers who are appropriately trained in behaviour support strategies) has been shown to maximise learning among youth with ASD, as well as contribute to parental wellbeing (Preece and Howley 2018). Finally, included studies focused narrowly on the parent’s perspective—particularly maternal influences. Given the significant changes in family formation and household structure seen over the last thirty years, research on the relationships among cohabiting biological versus stepparent families, single parent families as well as the health of legal guardians (e.g., custodial grandparents) is warranted (Manning et al. 2014; OECD 2011; Whitley et al. 2015). Indeed, these subgroups were represented by only three studies in the current review (Hickey et al. 2020; Schwartz et al. 2018; Tudor et al. 2018).

Conclusions

The current meta-analysis provides an overview of how different support systems regulate the mental health of caregivers of children living with ASD. Clinicians should be mindful of the informal social supports available to parents, with those living alone or those who perceive low social support being at greater mental health risk. The findings support an ecological-based approach to caregiver counselling, namely a need to target different family members and include additional community and school-based services for those with limited resources.

References

References marked with an asterisk indicate studies included in the meta-analysis.

American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychiatric Association. (1987). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

Barrera, M., Sandler, I. N., & Ramsay, T. B. (1981). Preliminary development of a scale of social support: Studies on college students. American Journal of Community Psychology, 9(4), 435–447. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00918174.

*Benson, P. R. (2006). The impact of child symptom severity on depressed mood among parents of children with ASD: The mediating role of stress proliferation. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(5), 685–695.

*Benson, P. R. (2012). Network characteristics, perceived social support, and psychological adjustment in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(12), 2597–2610.

*Benson, P. R., & Karlof, K. L. (2009). Anger, stress proliferation, and depressed mood among parents of children with ASD: A longitudinal replication. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(2), 350–362. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-008-0632-0.

*Benson, P. R., & Kersh, J. (2011). Marital quality and psychological adjustment among mothers of children with ASD: Cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(12), 1675–1685. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1198-9.

Bitsika, V., Sharpley, C. F., & Bell, R. (2013). The buffering effect of resilience upon stress, anxiety and depression in parents of a child with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 25(5), 533–543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-013-9333-5.

Bluth, K., Roberson, P. N., Billen, R. M., & Sams, J. M. (2013). A stress model for couples parenting children with autism spectrum disorders and the introduction of a mindfulness intervention. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 5(3), 194–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12015.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis. Hoboken: Wiley.

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., Higgins, J., & Rothstein, H. (2013). Comprehensive meta-analysis (Version 3) [Computer software]. Englewood, NJ: Biostat.

Boyd, B. A. (2002). Examining the relationship between stress and lack of social support in mothers of children with autism. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 17, 208–215.

Bromley, J., Hare, D. J., Davison, K., & Emerson, E. (2004). Mothers supporting children with autistic spectrum disorders: Social support, mental health status and satisfaction with services. Autism, 8, 409–423.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32, 513–531.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22, 723–742.

*Charnsil, C., & Bathia, N. (2010). Prevalence of depressive disorders among caregivers of children with autism in Thailand. ASEAN Journal of Psychiatry, 11(1), 87–95.

Cheung, K., & Theule, J. (2019). Paternal depressive symptoms and parenting behaviors: An updated meta-analysis. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(3), 613–626.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155.

Covidence systematic review software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Retrieved from https://www.covidence.org

Cridland, E. K., Jones, S. C., Magee, C. A., & Caputi, P. (2014). Family-focused autism spectrum disorder research: A review of the utility of family systems approaches. Autism, 18(3), 213–222.

Cumming, G. (2012). Understanding the new statistics: Effect sizes, confidence intervals, and meta-analysis. New York: Routledge.

*Da Paz, N. S., Siegel, B., Coccia, M. A., & Epel, E. S. (2018). Acceptance or despair? Maternal adjustment to having a child diagnosed with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(6), 1971–1981.

*Davis, N. O., & Carter, A. S. (2008). Parenting stress in mothers and fathers of toddlers with autism spectrum disorders: Associations with child characteristics. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(7), 1278–1291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0512-z.

Del-Pino-Casado, R., Frías-Osuna, A., Palomino-Moral, P. A., Ruzafa-Martínez, M., & Ramos-Morcillo, A. J. (2018). Social support and subjective burden in caregivers of adults and older adults: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 13(1), e0189874. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189874.

Dyches, T. T., Christensen, R., Harper, J. M., Mandleco, B., & Roper, S. O. (2016). Respite care for single mothers of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(3), 812–824. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2618-z.

*Ekas, N. V., Lickenbrock, D. M., & Whitman, T. L. (2010). Optimism, social support, and well-being in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 1274–1284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-0986-y.

*Ekas, N. V., Pruitt, M. M., & McKay, E. (2016). Hope, social relations, and depressive symptoms in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 29–30, 8–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2016.05.006.

*Ekas, N. V., Ghilain, C., Pruitt, M., Celimli, S., Gutierrez, A., & Alessandri, M. (2016). The role of family cohesion in the psychological adjustment of non-hispanic white and hispanic mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 21, 10–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2015.09.002.

England, M. J. E., & Sim, L. J. (2009). Depression in parents, parenting, and children: Opportunities to improve identification, treatment, and prevention. Washington DC: National Academies Press.

Factor, R. S., Ollendick, T. H., Cooper, L. D., Dunsmore, J. C., Rea, H. M., & Scarpa, A. (2019). All in the family: A systematic review of the effect of caregiver-administered autism spectrum disorder interventions on family functioning and relationships. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 22, 1–25.

*García-López, C., Sarriá, E., & Pozo, P. (2016). Parental self-efficacy and positive contributions regarding autism spectrum condition: An actor–partner interdependence model. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(7), 2385–2398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2771-z.

Gariépy, G., & Honkaniemi, H. (2016). Social support and protection from depression: Systematic review of current findings in Western countries. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 209(4), 284–293.

Gibbons, R. D., Hedeker, D., Elkin, I., Waternaux, C., Kraemer, H. C., Greenhouse, J. B., The Application to the NIMH Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program Dataset. (1993). Some conceptual and statistical issues in analysis of longitudinal psychiatric data. Application to the NIMH treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program dataset. Archives of General Psychiatry, 50, 739–750. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820210073009.

Green, L. (2013). The well-being of siblings of individuals with autism. ISRN Neurology. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/417194.

Haber, M. G., Cohen, J. L., Lucas, T., & Baltes, B. B. (2007). The relationship between self-reported received and perceived social support: A meta-analytic review. American Journal of Community Psychology, 39, 133–144.

Hamaker, E. L., Kuiper, R. M., & Grasman, R. P. (2015). A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychological Methods, 20, 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038889.

Hartley, M., Dorstyn, D., & Due, C. (2019). Mindfulness for children and adults with autism spectrum disorder and their caregivers: A meta-analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 49(10), 4306–4319. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04145-3.

Hartley, S. L., Barker, E. T., Seltzer, M. M., & Greenberg, J. S. (2012). Marital satisfaction and life circumstances of grown children with autism across 7 years. Journal of Family Psychology, 26(5), 688.

*Hastings, R. P., Kovshoff, H., Ward, N. J., Degli Espinosa, F., Brown, T., & Remington, B. (2005). Systems analysis of stress and positive perceptions in mothers and fathers of pre-school children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35(5), 635–644. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-005-0007-8.

*Hickey, E. J., Hartley, S. L., & Papp, L. (2020). Psychological well-being and parent-child relationship quality in relation to child autism: An actor-partner modeling approach. Family Process., 59(2), 636–650. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12432.

Higgins, J. P., & Altman, D. G. (2008). Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In J. P. Higgins & S. Green (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Hoboken: Wiley.

Higgins, J., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. British Medical Journal, 327, 557–560.

*Ingersoll, B., & Hambrick, D. Z. (2011). The relationship between the broader autism phenotype, child severity, and stress and depression in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(1), 337–344. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2010.04.017.

*Jellett, R., Wood, C. E., Giallo, R., & Seymour, M. (2015). Family functioning and behaviour problems in children with autism spectrum disorders: The mediating role of parent mental health. Clinical Psychologist, 19(1), 39–48.

Karst, J. S., & Van Hecke, A. V. (2012). Parent and family impact of autism spectrum disorders: A review and proposed model for intervention evaluation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 15(3), 247–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-012-0119-6.

Kelly, A. B., Garnett, M. S., Attwood, T., & Peterson, C. (2008). Autism spectrum symptomatology in children: The impact of family and peer relationships. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(7), 1069–1081.

*Kim, E. S., & Kim, B. S. (2009). The structural relationships of social support, mother's psychological status, and maternal sensitivity to attachment security in children with disabilities. Asia Pacific Education Review, 10(4), 561–573.

*Kim, I., Ekas, N. V., & Hock, R. (2016). Associations between child behavior problems, family management, and depressive symptoms for mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 26, 80–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2016.03.009.

Kmet, L. M., Lee, R. C., & Cook, L. S. (2004). Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Edmonton, AB: Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research (AHFMR). HTA Initiative #13.

*Kuhn, J., Ford, K., & Dawalt, L. S. (2018). Brief report: Mapping systems of support and psychological well-being of mothers of adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(3), 940–946.

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis. California: California Sage Publications.

Maletic, V., Robinson, M., Oakes, T., Iyengar, S., Ball, S. G., & Russell, J. (2007). Neurobiology of depression: An integrated view of key findings. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 61, 2030–2040.

Manning, W. D., Brown, S. L., & Stykes, J. B. (2014). Family complexity among children in the United States. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 654(1), 48–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716214524515.

Marshall, B., Kollia, B., Wagner, V., & Yablonsky, D. (2018). Identifying depression in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: Recommendations for professional practice. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 56(4), 23–27. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20171128-02.

McIntyre, L. L., & Brown, M. (2018). Examining the utilization and usefulness of social support for mothers with young children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 43(1), 93–101. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2016.1262534.

McHale, S. M., Updegraff, K. A., & Feinberg, M. E. (2016). Siblings of youth with autism spectrum disorders: Theoretical Perspectives on sibling relationships and individual adjustment. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(2), 589–602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2611-6.

Meadan, H., Halle, J. W., & Ebata, A. T. (2010). Families with children who have autism spectrum disorders: Stress and support. Exceptional Children, 77(1), 7–36.

*Meyer, K. A., Ingersoll, B., & Hambrick, D. Z. (2011). Factors influencing adjustment in siblings of children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(4), 1413–1420. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2011.01.027.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Möller, H. J. (2000). Rating depressed patients: Observer- vs self-assessment. European Psychiatry, 15(3), 160–172.

*Neff, K. D., & Faso, D. J. (2015). Self-compassion and well-being in parents of children with Autism. Mindfulness, 6(4), 938–947.

OECD (2011). Doing better for families. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/47701118.pdf.

Orwin, R. G. (1983). A fail-safe N for effect size in meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Statistics, 8, 157–159.

Preece, D., & Howley, M. (2018). An approach to supporting young people with autism spectrum disorder and high anxiety to re-engage with formal education—the impact on young people and their families. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 23(4), 468–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2018.1433695.

*Pruitt, M. M., Rhoden, M., & Ekas, N. V. (2018). Relationship between the broad autism phenotype, social relationships and mental health for mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 22(2), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316669621.

*Pruitt, M. M., Willis, K., Timmons, L., & Ekas, N. V. (2016). The impact of maternal, child, and family characteristics on the daily well-being and parenting experiences of mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 20(8), 973–985. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315620409.

Schreiber, C. (2011). Social skills interventions for children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 13(1), 49–62.

*Schwartz, J., Huntington, N., Toomey, M., Laverdiere, M., Bevans, K., Blum, N., et al. (2018). Measuring the involvement in family life of children with autism spectrum disorder: A DBPNet study. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 83, 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2018.07.012.

Serrata, C. A. (2012). Psychosocial aspects of parenting a child with autism. Journal of Applied Rehabilitation Counseling, 43(4), 29–36.

Shivers, C. M., Jackson, J. B., & McGregor, C. M. (2019). Functioning among typically developing siblings of individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 22(2), 172–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-018-0269-2.

Sim, A., Cordier, R., Vaz, S., & Falkmer, T. (2016). Relationship satisfaction in couples raising a child with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review of the literature. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 31, 30–52.

Singer, G. H. S. (2006). Meta-analysis of comparative studies of depression in mothers of children with and without developmental disabilities. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 111(3), 155–169.

Singer, G., Ethridge, B., & Aldana, S. (2007). Primary and secondary effects of parenting and stress management interventions for parents or children with developmental disabilities: A meta-analysis. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 13(4), 357–369.

*Singh, P., Ghosh, S., & Nandi, S. (2017). Subjective burden and depression in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder in India: Moderating effect of social support. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(10), 3097–3111.

Smith, L. E., Greenberg, J. S., & Seltzer, M. M. (2012). Social support and well-being at mid-life among mothers of adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(9), 1818–1826. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1420-9.

Smith, M. S., & Elder, J. H. (2010). Siblings and family environments of persons with autism spectrum disorder: A review of the literature. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 23(3), 189–195.

*Taylor, J. L., & Warren, Z. E. (2012). Maternal depressive symptoms following autism spectrum diagnosis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(7), 1411–1418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1375-x.

*Teague, S. J., Newman, L. K., Tonge, B. J., & Gray, K. M. (2018). Caregiver mental health, parenting practices, and perceptions of child attachment in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(8), 2642–2652.

*Timmons, L., Willis, K. D., Pruitt, M. M., & Ekas, N. V. (2016). Predictors of daily relationship quality in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(8), 2573–2586.

Tint, A., & Weiss, J. A. (2016). Family wellbeing of individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A scoping review. Autism, 20(3), 262–275.

*Tudor, M. E., Rankin, J., & Lerner, M. D. (2018). A model of family and child functioning in siblings of youth with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(4), 1210–1227.

*Wachtel, K., & Carter, A. S. (2008). Reaction to diagnosis and parenting styles among mothers of young children with ASDs. Autism, 12(5), 575–594. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361308094505.

*Weitlauf, A. S., Vehorn, A. C., Taylor, J. L., & Warren, Z. E. (2014). Relationship satisfaction, parenting stress, and depression in mothers of children with autism. Autism, 18(2), 194–198. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361312458039.

Whitaker, P. (2002). Supporting families of preschool children with autism: What parents want and what helps. Autism, 6, 411–426.

Whitley, D. M., Fuller-Thomson, E., & Brennenstuhl, S. (2015). Health characteristics of solo grandparent caregivers and single parents: A comparative profile using the behavior risk factor surveillance survey. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research, 2015, 630717. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/630717.

Wills, T. A., & Shinar, O. (2000). Measuring perceived and received social support. In S. Cohen, L. G. Underwood, & B. H. Gottlieb (Eds.), Social support measurement and intervention (pp. 86–135). New York: Oxford University Press.

World Health Organization. (2004). ICD-10 : International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (Tenth revision, 2nd ed.). Retrieved February 9, 2020, from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42980.

World Health Organization. (2018). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems (11th Revision). Retrieved February 9, 2020, from https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en.

Zablotsky, B., Bradshaw, C. P., & Stuart, E. A. (2013). The association between mental health, stress, and coping supports in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(6), 1380–1393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1693-7.

Zhou, W., Liu, D., Xiong, X., & Xu, H. (2019). Emotional problems in mothers of autistic children and their correlation with socioeconomic status and the children's core symptoms. Medicine, 98(32), e16794. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000016794.

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., et al. (1988). The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30–41.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was adapted from a dissertation submitted by the first author in partial fulfilment of an Honours degree of Bachelor of Psychological Science at the University of Adelaide. The authors are grateful to the individual researchers who kindly responded to requests for additional data or enquiries regarding their papers. Special thanks are also extended to Vikki Langton, Research Librarian at the University of Adelaide, for her assistance in developing and reviewing the database search terms.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VS was responsible for study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, and manuscript drafts; DD assisted with data analysis, study screening, interpretation and manuscript revisions; and AT assisted with study screening, manuscript writing and editing.

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schiller, V.F., Dorstyn, D.S. & Taylor, A.M. The Protective Role of Social Support Sources and Types Against Depression in Caregivers: A Meta-Analysis. J Autism Dev Disord 51, 1304–1315 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04601-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04601-5