Abstract

This study investigated informant agreement on emotional and behavior problems and social skills in youth with autism spectrum disorder or intellectual disability using meta-analytic methods. Forty-nine studies were included, consisting of 107 effect sizes. The mean weighted effect size across all raters and all behaviors was .36, reflecting moderate agreement. Consistent with meta-analyses in typically developing youth, pairs of similar informants (e.g., parent–parent) demonstrated higher agreement compared to pairs of different raters (e.g., parent–teacher). With all rater pairs combined, agreement was significantly higher for externalizing problems (\( \bar{r} \) = .42) than either internalizing problems (\( \bar{r} \) = .35) or social skills (\( \bar{r} \) = .30). Several factors appear to moderate the level of agreement among informants, including the youth’s diagnosis, age, and IQ.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are pervasive neurodevelopmental disorders characterized by deficits in social communication and the presence of restricted and repetitive behaviors or interests. Intellectual disability (ID) is characterized by significant impairments in cognitive functioning, including reasoning, problem solving, and abstract thinking, as well as deficits in adaptive behavior, including conceptual, social, and practical skills (APA 2000, 2013). ASD and ID can co-occur; recent prevalence estimates suggest that approximately half of individuals with ASD have an IQ in the average or above average range (Elsabbagh et al. 2012). Individuals diagnosed with ASD or ID often experience co-occurring emotional and behavioral problems. This includes symptoms of co-occurring psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety or mood disorders and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), as well as other behavioral problems including irritability and aggression (e.g., Einfeld et al. 2006; Lecavalier 2006). Individuals with ASD or ID also often show deficits across a wide range of social skills, including difficulty interpreting or responding to social cues, avoiding eye contact, difficulty engaging in back-and-forth conversation, limited use of non-verbal behaviors including facial expression and gestures, difficulties with turn-taking or sharing, and poor conflict resolution skills (e.g., de Bildt et al. 2005).

Multi-Informant Agreement

When assessing psychological functioning, which includes emotional and behavioral problems and social skills, the use of multiple informants is critical to obtain an accurate and comprehensive picture of the individual. In fact, this is considered a “gold standard” in the assessment of psychopathology in children and adolescents (e.g., Mash and Hunsley 2005). The importance of using multiple informants lies in the fact that certain behaviors or symptoms may be absent or present depending on the environmental context, thus limiting the ability of a single informant to accurately report on these behaviors and symptoms (Achenbach et al. 1987; De Los Reyes 2011). Additionally, reports are influenced by informant biases, attributions, expectations, and standards. Finally, informants may differ in terms of how often they interact with or observe the child, and how their presence impacts the child’s behavior, all of which could contribute to discrepancies in information provided by different informants (De Los Reyes 2011; Hoyt 2000).

Agreement among informants has been widely studied in typically developing (TD) youth. Achenbach et al.’s (1987) seminal meta-analysis of 119 studies on informant agreement of behavioral and emotional problems showed that pairs of similar informants, such as two parents, demonstrated higher agreement on the Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA) rating scales (\( \bar{r} \) = .60) than pairs of different informants, such as a parent and teacher (\( \bar{r} \) = .28), or than the child him or herself with another informant (\( \bar{r} \) = .22). Across all pairs of raters, agreement was stronger for externalizing problems (\( \bar{r} \) = .41) compared to internalizing problems (\( \bar{r} \) = .32). Additionally, agreement among informants was significantly higher when assessing children aged six to eleven (\( \bar{r} \) = .51) than when assessing adolescents (\( \bar{r} \) = .41). Child gender and clinical status as well as the gender of the parent informant did not impact the level of agreement.

A more recent meta-analysis (Duhig et al. 2000) provided similar results regarding maternal and paternal ratings of internalizing and externalizing problems in TD children and adolescents. Based on the results of 60 studies, parents showed stronger agreement for externalizing problems (\( \bar{r} \) = .66) than internalizing problems (\( \bar{r} \) = .46). For both internalizing and externalizing problems, parental agreement was greater in adolescence (internalizing \( \bar{r} \) = .45; externalizing \( \bar{r} \) = .63) than in early (internalizing \( \bar{r} \) = .12; externalizing \( \bar{r} \) = .47) or middle childhood (internalizing \( \bar{r} \) = .28; externalizing \( \bar{r} \) = .55), which contrasts the findings of Achenbach et al. (1987).

Lastly, Renk and Phares’ (2004) meta-analysis of 74 studies of TD youth showed that agreement on social competence among pairs of different informants (\( \bar{r} \) ranging from .21 to .39 across rater pairs) was equivalent to that of similar informants (\( \bar{r} \) ranging from .36 to .48), which contrasts Achenbach et al.’s (1987) results showing higher agreement among similar informants. Agreement between parent- and child-report was greatest during middle childhood whereas agreement between peer- and child-report as well as between teacher- and peer-report was greatest during adolescence.

The Current Study

Rating scales are frequently used when assessing emotional and behavioral problems and social functioning in youth with ASD or ID. There is currently limited information regarding informant agreement on these scales for youth with ASD or ID. Thus, the current study focuses on informant agreement on behavioral and emotional problems and social skills in youth with ASD or ID using a meta-analytic strategy. It is the first such study in the field of developmental disabilities. As compared to TD youth, agreement among parents and teachers was hypothesized to be higher for youth with ASD or ID due to language and cognitive deficits that would lead informants to rely more on observable behaviors. However, it was hypothesized that agreement between self-report and other informants would be lower than TD youth due to these very same language and cognitive deficits which may impact the ability of individuals with ASD or ID to accurately report on their own functioning. Despite the limited published research focusing exclusively on informant agreement in ASD or ID, this information is often included in the context of other studies. Following a comprehensive literature search, meta-analytic methods were used to determine the average agreement among pairs of informants, such as parent and teacher or parent and child, as well as across similar (e.g., parent and parent) and different (e.g., parent and teacher) rater pairs. Moderators of the level of agreement, including the youth’s diagnosis (ASD vs. ID), age, and IQ, were also investigated.

Methods

Literature Search

The PsycInfo Database was searched for relevant articles. We used a total of 34 search terms. Examples of search terms included “Agreement,” “Concordance,” “Interrater,” “Informant” as well as the name of popular rating scales (e.g., Aberrant Behavior Checklist, Child Behavior Checklist) and authors known to have published in this area. Studies were considered for inclusion provided that they were: (a) Published in an academic journal between 2000 and April 2014, (b) Written in English, (c) Focused on emotional or behavioral problems or social skills, (d) Used rating scales completed by multiple informants, (e) Reported a statistic reflecting within-subjects agreement, and (f) Had samples consisting of children with ASD or ID. Any subset of ages, through age 22, was considered for inclusion. In terms of diagnosis, ASD diagnoses included Autistic Disorder, Asperger’s Disorder and Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified per DSM-IV-TR criteria. Samples that included both children with and without ASD or children with and without ID were considered for inclusion provided that demographic information and effect sizes were reported separately so that only information pertinent to the subsample of youth with ASD or ID could be included in the meta-analysis.

A total of 4,979 abstracts were generated with these searches. These abstracts were reviewed for the six inclusionary criteria listed above. The majority of abstracts excluded at this point of the literature search had samples of adults or youth with other diagnoses, did not use rating scales, or only utilized one informant. If it was not clear from an abstract whether the study met inclusionary criteria (e.g., not specifying who completed rating scales or what measures were used), the article was retrieved for further review. A total of 310 of the articles were retrieved based on appearing to meet criteria for inclusion, with 49 being eligible for inclusion in the meta-analysis. As seen in Fig. 1, the most common reasons for exclusion were lack of necessary statistical information (e.g., only reporting means and standard deviations or only reporting significant correlations), using only one informant or a different type of informant (e.g., clinicians), having a sample that was not comprised entirely of children with ASD or ID, using an assessment tool other than rating scales (e.g., interviews, observations), or not reporting on emotional or behavioral problems or social skills. Other reasons for exclusion included ratings that were collected at different time points (e.g., parent ratings collected 2 years after teacher ratings) and missing information, such as the relationship of informants to the child.

Calculation of Effect Sizes

Using the 49 selected articles, a total of 107 effect sizes were identified. The authors independently reviewed the measures used in the 49 selected articles and classified the measures’ subscales as externalizing problems, internalizing problems, or social skills based on the content of the measures and subscales. The authors only disagreed on the classification of a minority of the subscales (approximately 10 %), and discussed these disagreements to reach consensus. The majority of the disagreements were on subscales assessing peer relationships (e.g., social problems on the ASEBA scales). Given that the content of these subscales could reflect social skills, externalizing behavior, or both, the authors ultimately decided not to include these subscales in the meta-analysis. The classification of these measures and subscales can be seen in Table 1, along with the demographic information for each sample and the calculated effect sizes. Consistent with other published meta-analyses (Achenbach et al. 1987; Duhig et al. 2000; Renk and Phares 2004), effect sizes for each cross-informant pair and behavior category were treated independently. However, while some studies reported only one effect size within a behavior category for each informant pair, several studies reported multiple effect sizes within a behavior category for one informant pair (e.g., reporting parent–teacher agreement separately for ADHD and oppositional defiant disorder, both externalizing problems). Including multiple effect sizes in the same behavior category for the same rater pair from the same study would violate the independence assumption, thus possibly inflating the sample size of the statistical tests and effect sizes beyond what is actually included in the meta-analysis (Wolf 1986). Therefore, when studies reported agreement among the same pair of informants for multiple behaviors on the same rating scale that would fall within one behavior category (externalizing problems, internalizing problems, or social skills), the effect sizes were averaged. When studies included multiple effect sizes from different rating scales that would fall within one category, the effect size from the more widely used measure was selected. For example, Ozsivadjian et al. (2013) reported correlations for SCAS Total Anxiety as well as for the total score on the Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI); as the CDI was not used in any other studies included in the meta-analysis and the SCAS was used in another study (Farrugia and Hudson 2006), it was the correlation for the SCAS that was included in the meta-analysis. Lastly, three studies reported parent–child and parent–teacher correlations separately for mothers and fathers (Baker et al. 2007; Kalyva 2010; van Steensel et al. 2013). To be consistent with other studies included in the meta-analysis, the correlations using mothers were used for the meta-analysis because parent respondents in other studies were 80–90 % mothers.

The most commonly reported statistics were Pearson correlations and intra-class correlations. Paired sample t-tests were reported in two studies; these statistics were converted to Pearson correlations using the formula suggested by Rosenthal (1991). One study reported ANOVA results; this F-value was converted to a Pearson correlation using the formula suggested by Rosenthal (1991). To reduce the skew of the distribution of correlations, Pearson correlations and ICC were converted to a z score using Fisher’s z transformation (Fisher 1938), and standard errors were calculated for these effect size estimates. While some have argued that this transformation of the ICC can be biased in terms of the probability estimates, this bias is significantly reduced when the ICC represents the correlation between two groups rather than several groups (McGraw and Wong 1996). As there is currently no other identified way to convert ICC to a common effect size metric and all ICC included in the meta-analysis are of only two groups, Fisher’s z transformation was used in order to include these studies in the meta-analysis.

Planned Analyses

Similar to the meta-analyses conducted by Achenbach et al. (1987), Duhig et al. (2000), and Renk and Phares (2004), findings from the included studies were combined to determine the degree of correspondence within each cross-informant pair for the three behavior categories (externalizing problems, internalizing problems, social skills). Additionally, similar to Achenbach et al. (1987), additional average effect sizes were calculated for all behaviors, pairs of similar raters (e.g., parent–parent), pairs of different raters (e.g., parent–teacher, parent–child) and all raters. To control for sample size, effect sizes were weighted using the inverse of the squared standard error (as suggested by Rosenthal 1991), and weighted mean effect sizes were calculated in addition to un-weighted mean effect sizes. To determine the degree of heterogeneity of effect sizes contributing to a composite effect size, Hedges’ test for homogeneity (Hedges’ Q test) was used (Hedges and Olkin 1985); when this is statistically significant, this indicates that there is significant heterogeneity among the effect sizes contributing to the mean weighted effect size.

Potential moderators were considered to explain heterogeneity of the effect sizes. For both categorical moderators (diagnosis, and age and IQ ranges) and to compare effect sizes across raters, behavior categories, and children with ASD versus ID, analyses based on the principle of ANOVA were used as suggested by Hedges (1982) and Lipsey and Wilson (2001). As suggested by Card (2012), for continuous moderators (average age and IQ), regression analysis was used with the effect size (as a z score) as the outcome variable and the potential moderator as a predictor. Weighted least squares regression was used to give studies with larger sample sizes more weight in the regression model, with the inverse of the squared standard error serving as the weight for each study.

Results

Average Effect Sizes

Table 2 presents the mean unweighted and weighted correlations across the five rater pairs and three behavior categories. All mean weighted correlations were significantly >0, and most demonstrated significant heterogeneity in the contributing effect sizes. Using Hedges’ Q test for between group homogeneity, there were several significant differences among rater pairs for externalizing behavior: teacher–teacher agreement was significantly higher than parent–teacher (Q = 10.32, p < .001), parent–child (Q = 4.99, p = .03), and teacher–child agreement (Q = 6.77, p = .009); and parent–parent agreement was significantly higher than parent–teacher (Q = 35.99, p < .001), parent–child (Q = 19.16, p < .001), and teacher–child agreement (Q = 17.43, p < .001). Several significant differences across rater pairs were also found for internalizing behavior: parent–child agreement was significantly higher than parent–teacher agreement (Q = 20.83, p < .001); parent–parent agreement was significantly higher than parent–teacher (Q = 69.32, p < .001), parent–child (Q = 28.96, p < .001), and teacher–child agreement (Q = 26.69, p < .001); and teacher–teacher agreement was significantly higher than parent–teacher (Q = 7.22, p = .007) and teacher–child agreement (Q = 4.93, p < .001). Finally, for social skills, parent–parent agreement was significantly higher than parent–teacher agreement (Q = 4.89, p = .03).

Table 3 presents the mean unweighted and weighted effect sizes across similar rater pairs (parent–parent and teacher–teacher), different rater pairs (parent–teacher, parent–child, and teacher–child), and all raters across the three behavior categories and the aggregate of all behaviors. All mean weighted correlations were significantly different from zero, and most of these correlations demonstrated significant heterogeneity in the contributing effect sizes. Using Hedges’ Q test for between group homogeneity, similar rater pairs showed higher agreement than different rater pairs for the aggregate of all behaviors (Q = 104.85, p < .001) and each of the three behavior categories (externalizing Q = 41.65, p < .001; internalizing Q = 59.40, p < .001; social skills Q = 5.30, p = .02). For all raters, agreement on externalizing problems was greater than internalizing problems (Q = 10.77, p = .001) and social skills (Q = 24.11, p < .001), and agreement on internalizing problems was higher than social skills (Q = 4.07, p = .04). For similar rater pairs, agreement on social skills was lower than either externalizing problems (Q = 7.79, p = .005) or internalizing problems (Q = 6.76, p = .009). For different rater pairs, agreement on externalizing problems was greater than agreement on internalizing problems (Q = 11.40, p < .001) or social skills (Q = 15.23, p < .001).

Moderators of Informant Agreement

Given the significant heterogeneity seen for the majority of the mean weighted correlations, several moderators were considered. These analyses are quite limited by the information (and lack thereof) reported in the published studies (as seen in Table 1), which limits the number of studies that can be included in the moderator analyses. Diagnosis was considered as a categorical moderator, comparing samples of ASD youth to samples of ID youth. There were no significant differences across youth with ASD and youth with ID for externalizing behavior or social skills. However, agreement on internalizing behavior was significantly higher for youth with ASD than youth with ID for all raters (ASD \( \bar{r} \) = .35; ID \( \bar{r} \) = .34; Q = 3.91, p < .05), similar rater pairs (ASD \( \bar{r} \) = .75; ID \( \bar{r} \) = .62; Q = 3.87, p < .05), and different rater pairs (ASD \( \bar{r} \) = .32; ID \( \bar{r} \) = .29; Q = 4.31, p = .04). For the aggregate of all behaviors, agreement among different rater pairs was higher for ASD youth (ASD \( \bar{r} \) = .334; ID \( \bar{r} \) = .328; Q = 3.87, p < .05) while agreement among all raters was significantly higher for ID youth (ASD \( \bar{r} \) = .35; ID \( \bar{r} \) = .38; Q = 5.74, p = .02).

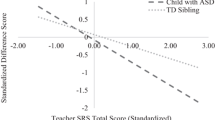

Participant age was considered as both a categorical and a continuous moderator. As a categorical moderator, the age range of the sample was classified as preschool (age 5 and under), school-aged (age 5–12), or adolescent (age 12–21). The boundaries for these categories are arbitrary and we allowed the age range of a sample to fall 2 years outside the window (e.g., if the age range was 4–9 years, it was classified as school-age and if the age range was 10–16 years, it was classified as adolescent). As seen in Table 1, many studies assessed a broad range of ages (e.g., 3–21, 6–18) or did not report the age range of the sample and therefore could not be used in this moderator analysis. A total of five studies reported on preschool-aged samples, nine on school-aged samples, and 11 on adolescent samples. Given how few studies could be used in this analysis, it was not feasible to consider this moderator separately for similar and different rater pairs. For the aggregate of all behaviors and externalizing problems, there were no significant differences between the age categories. Informants showed higher agreement for internalizing problems in adolescents (\( \bar{r} \) = .36) than school-aged children (\( \bar{r} \) = .19; Q = 6.30, p = .01). Agreement among informants was greater for social skills in school-aged children (\( \bar{r} \) = .40) than adolescents (\( \bar{r} \) = .21; Q = 6.26, p = .01). As a continuous moderator, the average age of the sample was entered into the regression analysis. As seen in Table 1, six studies did not report the average age of the sample and could not be used in these analyses. Average age emerged as a significant moderator of informant agreement for pairs of different raters assessing internalizing problems (β = .38, p < .001), for pairs of similar raters assessing internalizing problems (β = −.65, p = .02), and for pairs of similar raters assessing the aggregate of all behaviors (β = −.43, p = .02).

Participant IQ was also considered as both a categorical and a continuous moderator. As a categorical moderator, the range of IQ for each study was categorized as falling in the ID range (below 70) or the non-ID range (above 70). The cutoff of 70 represents a rough boundary that varied by as much as 10 points (e.g., a sample with IQ all <75 was categorized in the ID range while a sample with IQ ranging from 66 to 133 was categorized in the non-ID range). Several studies included participants across the full range of IQ or did not report an IQ range, and thus could not be used in this moderator analysis. A total of five studies reported on samples in the ID range and fourteen studies reported on sample in the non-ID range. Given how few studies could be used in this analysis, it was not feasible to consider this moderator separately for similar and different raters. IQ did not emerge as a significant categorical moderator for the aggregate of all behaviors or for any of the three behavior categories. As a continuous moderator, the average IQ of the sample was entered into the regression analysis. As seen in Table 1, 23 studies reported an average IQ, thus these are the only studies included in the moderator analyses. Average IQ emerged as a significant moderator for all raters assessing internalizing problems (β = −.33, p = .005) and for pairs of similar raters assessing all behaviors (β = −.83, p < .001).

Discussion

This study was the first to report on informant agreement on emotional and behavior problems and social skills in youth with ASD or ID using meta-analytic methods. The mean weighted effect size across all raters and all behaviors was .36, reflecting moderate agreement. However, consistent with meta-analyses investigating this in TD youth (Achenbach et al. 1987; Duhig et al. 2000; Renk and Phares 2004), pairs of informants demonstrated differing levels of agreement, and this also varied across externalizing problems, internalizing problems, and social skills. The mean weighted effect sizes across informant pairs ranged from .34 to .71 for externalizing problems, from .25 to .69 for internalizing problems, and from .27 to .47 for social skills. Pairs of similar raters (e.g., parent–parent) showed significantly higher agreement on externalizing problems, internalizing problems, social skills, and the aggregate of all behaviors when compared to pairs of different raters (e.g., parent–teacher, teacher–child), which is likely due to the fact that similar raters observe the child in similar contexts, thus reducing the likelihood of context-dependent differences in child behavior. With all rater pairs combined, agreement was significantly higher for externalizing problems (\( \bar{r} \) = .42) than either internalizing problems (\( \bar{r} \) = .35) or social skills (\( \bar{r} \) = .30), and agreement on internalizing problems was significantly higher than agreement on social skills.

Comparison to Informant Agreement for TD Youth

Presented in Table 4 are the mean weighted effect sizes reported by Achenbach et al. (1987), Duhig et al. (2000), and Renk and Phares (2004), as well as those found in the current study. Given that these meta-analyses of TD youth did not report confidence intervals for the mean weighted correlations, it is not possible to make direct statistical comparisons with the current meta-analysis. However, some discrepancies are noteworthy. The greatest discrepancy is seen for parent–parent agreement on internalizing problems, which showed a mean weighted correlation of .69 in this meta-analysis, representing a difference of .24 when compared to Duhig et al. (2000) and a difference of .10 when compared to Achenbach et al. (1987) results. The current meta-analysis found a mean weighted correlation for parent–child agreement on social skills that was .15 higher than that reported in the Renk and Phares’ (2004) study. Conversely, it found a mean weighted correlation for teacher–teacher agreement on externalizing problems that was .12 lower than that reported by Achenbach et al. (1987). Lastly, the current meta-analysis yielded a mean weighted correlation for parent–teacher agreement on social skills that was .11 lower and a mean weighted correlation for parent–parent agreement on social skills that was .11 higher than that reported by Renk and Phares (2004). These discrepancies may result from youth with ASD or ID relying more heavily on caregivers for social and emotional support, which may lead to greater caregiver awareness of their emotional and behavioral problems. It is also possible that agreement differs due to differences in the nature of these problems across TD and ASD or ID populations. For instance, because emotional and behavioral problems and social skills deficits are more prevalent in youth with ASD or ID, caregivers may focus more on these concerns. Additionally, youth with ASD or ID may show a greater behavioral expression of internalizing problems, particularly anxiety, making these concerns more readily observable by caregivers (Ozsivadjian et al. 2013).

While some discrepancies were observed, informant agreement in youth with ASD or ID is generally comparable that reported in TD youth. Indeed, for youth with ASD or ID as well as TD youth, agreement among pairs of similar informants is greater than that of pairs of different informants for externalizing and internalizing problems. While this same pattern was observed in this meta-analysis for social skills in youth with ASD or ID, Renk and Phares (2004) did not find greater agreement among pairs of similar raters for social skills in TD youth. While Renk and Phares (2004) hypothesized that emotional and behavioral problems are much more salient than social skills, thus leading to greater informant agreement, it may be the case that social skills are more salient for youth with ASD or ID, thus leading to higher agreement seen among similar rater pairs in the current meta-analysis.

Moderators of Informant Agreement

When considering diagnosis as a categorical moderator, few differences existed across youth with ASD and youth with ID. Agreement on internalizing behavior was significantly higher for youth with ASD across all raters as well as within similar raters and different raters. Additionally, for the aggregate of all behaviors, agreement among different raters pairs was higher for youth with ASD and agreement among all rater pairs was higher for youth with ID. However, the magnitude of these discrepancies was small, suggesting no meaningful practical difference. Additionally, the difference for the aggregate of all behaviors as assessed by all raters likely existed as 31 % of the contributing effect sizes for youth with ID were from similar raters while only 6 % were from similar raters for youth with ASD. As similar raters show higher agreement than different raters, this would lead to a higher mean weighted effect size for youth with ID. Overall, this suggests that agreement among pairs of informants is similar for youth with ASD and youth with ID, indicating that the use of multiple informants is equally important in each population in order to obtain a comprehensive description of psychological functioning.

When the age range of the sample was considered as a continuous moderator, agreement among similar raters on internalizing problems and the aggregate of all behaviors decreased as average age increased. It is possible that these behaviors may be more observable or more cross-situationally consistent for younger children. In contrast, as average age increased, agreement among different raters on internalizing problems also increased. It is possible that this increase in agreement among pairs of different raters reflects the fact that youth are able to more accurately complete self-report measures with increasing age. Slightly different patterns emerged when the average age of the sample was considered as a categorical moderator. Agreement among all pairs of informants was significantly higher for school-aged children as compared to adolescents when it came to social skills. Additionally, agreement on internalizing problems was significantly higher for adolescents as compared to school-aged children.

When the IQ range of the sample was considered as a categorical moderator, no significant differences emerged, indicating that agreement among informants was consistent for those in the ID range and those in the non-ID range. However, when the average IQ of the sample was considered as a continuous moderator, two significant relationships emerged: with increasing IQ, agreement among similar raters on the aggregate of all behaviors decreased, as did agreement among all raters on internalizing problems. For youth with borderline or below average IQ, emotional and behavioral problems may be more salient and more likely to be a topic of discussion among caregivers, which could lead to higher agreement. It is also possible that youth with lower IQ have less variability in their behavior across environments, which would lead to increased agreement among caregivers.

Moderator analyses yielded slightly different results when treating age and IQ as categorical or continuous variables. Significantly more studies were included when considering age and IQ as continuous moderators, thus increasing the power of these analyses. Additionally, analyses may be less precise when age and IQ were considered as categorical moderators because of the variability in the ranges used. Lastly, due to the limited number of studies that could be used in the categorical analyses, this relationship was only considered among all raters, rather than among similar and different raters separately.

Importance of Informant Agreement

The use of multiple informants in psychological assessment is critical in order to obtain a comprehensive picture of the individual’s functioning across environments. Parent–child and teacher–child agreement was similar across youth with ASD or ID, suggesting that youth contribute information that is different than that contributed by parents in the assessment of their own emotional, behavioral, and social functioning. Individuals with ASD or ID often recognize their difficulties in these areas of functioning and can contribute valid information (e.g., Douma et al. 2006; Emerson 2005; Knott et al. 2006; Lopata et al. 2010; van Steensel et al. 2013). In fact, given that the magnitude of informant agreement is similar to that observed in TD youth, we see no reason why the difficulties associated with the use of self-report by youth with ASD or ID would be different than their TD counterparts. The use of multiple informants may be even more important for this population, particularly youth with ASD, due to difficulties generalizing skills across contexts and settings.

Informant discrepancies in TD youth have shown to map onto variations in behavior observed in the laboratory (De Los Reyes et al. 2009). Other studies have linked informant discrepancies to meaningful differences in behavior across contexts, including increased parent–teacher agreement on aggressive behavior as similarities in the social experience across home and school environments increases (Hartley et al. 2011). Informant discrepancies are additionally predictive of long-term outcomes. In TD youth, greater discrepancies between parent and child report of psychopathology have been shown to be predictive of poorer treatment outcomes 16 weeks–4 years later (Ferdinand et al. 2006; Panichelli-Mindel et al. 2005), poorer young adult outcomes 4 years later (Ferdinand et al. 2004), and lower parental involvement in therapy over the course of 14 months (Israel et al. 2007). Across studies, informant discrepancies are the most predictive of long-term outcomes when the discrepancies are larger. Finally, the use of different informants in outcome studies can lead to different conclusions across studies. Examining these outcome patterns across studies can help to identify hypotheses regarding treatment effects (De Los Reyes 2011).

Limitations

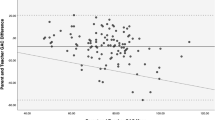

The main limitations of this study, like most meta-analyses, lies in the fact that data were taken from previously published literature. This introduces the “file drawer problem,” which suggests that there may be a publication bias in that unpublished studies not included in the meta-analysis might show different results than the published studies (Rosenthal 1991). However, in this case, funnel plots of the included studies were symmetrical, suggesting that there is limited publication bias for this meta-analysis. The possible analyses used in the meta-analysis are also limited by the published information. This impacted the calculation of mean weighted effect sizes when few studies reported on agreement between a particular pair of raters for one of the behavior categories (e.g., only one study reported on teacher–teacher agreement on social skills), thus limiting the interpretability of these results. This also affected the moderator analyses. For example, only 23 studies reported average participant IQ and thus could be included in this moderator analyses; the results may differ if all included studies had reported IQ. Due to the limitations of the published data, moderator analyses could not be considered separately for youth with ASD and youth with ID. This is especially relevant when considering the IQ analyses, which may be biased due to lower IQ in youth with ID as compared to youth with ASD. Because of this, the results of the IQ moderator analyses should be interpreted with caution. Additionally, there was variability in the magnitude of informant agreement across the various rating scales included in the meta-analysis. While we investigated this, there were not enough effect sizes for each measure to conduct separate analyses to investigate this variability in a meaningful way.

Finally, highly heterogeneous variables, such as agreement among various pairs of informants on different measures for samples with varying demographic characteristics, are combined into one mean effect size, and meaningful information may be lost in the process (Rosenthal 1991). It is possible that the included studies did not utilize samples of youth with only ASD or ID, which may increase the heterogeneity of effect sizes. For example, some youth included in ID samples may have also had ASD or other co-occurring diagnoses. Moderators were investigated to explain this heterogeneity, but it is possible that other important moderators were not considered in these analyses. For example, in TD youth, informant agreement is impacted by factors such as the child’s social desirability, parental psychopathology, parental stress, and parental acceptance of the child (for review, see De Los Reyes and Kazdin 2005). However, information about these potential moderators was not reported in studies included in this meta-analysis; thus they could not be considered in these analyses. Additionally, due to the limitations of the published data, it was not possible to consider all moderators in one model; thus the potential interaction of these moderators could not be evaluated. For example, it is possible that there are diagnostic or IQ differences for specific age groups that may not have been identified when considering these as separate moderators.

Conclusions

This meta-analysis suggests that agreement among informants on behavioral and emotional problems and social skills in youth with ASD or ID is similar to that observed in TD youth. Overall, agreement falls in the moderate range, with higher agreement seen in pairs of similar raters than different raters. Agreement on externalizing problems is greater than agreement on internalizing problems or social skills. Several factors appear to moderate the level of agreement among informants, including the youth’s diagnosis, age, and IQ. These results highlight the need to use multiple informants when assessing psychological functioning in youth with ASD or ID. Each informant provides different but important information, and this is critical to obtain a comprehensive picture of the individual.

Future research should examine the extent to which informant discrepancies map onto observed behavior variations, similarly to what has been considered in TD samples. Additionally, potential moderators of informant agreement should be investigated further. In addition to the moderators examined here, communication skills, ASD symptom severity, and adaptive behavior may be of particular importance to individuals with developmental disabilities. A further look into patterns in ratings from different informants, such as whether mothers provide higher ratings of behavior problems than teachers or vice versa might also be particularly useful. Importantly, there is a need to evaluate the utility of informant discrepancies in the developmental disabilities population, including whether considering these discrepancies leads to the development of more meaningful treatment goals or if they are predictive of treatment or other long-term outcomes, as well as the role informant discrepancies play in the assessment of other domains of psychological functioning, such as adaptive behavior.

References

* Those references were included in the meta-analysis

Achenbach, T. M., McConaughy, S. H., & Howell, C. T. (1987). Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 213–232.

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text revisions). Washington: American Psychiatric Association.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

*Baker, J. K., Fenning, R. M., Crnic, K. A., Baker, B. L., & Blacher, J. (2007). Prediction of social skills in 6-year-old children with and without developmental delays: Contributions of early regulation and maternal scaffolding. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 112(5), 375–391.

*Baker, B. L., McIntyre, L. L., Blacher, J., Crnic, K., Edelbrock, C., & Low, C. (2003). Pre-school children with and without developmental delay: Behaviour problems and parenting stress over time. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 47(4–5), 217–230.

*Barnhill, G. P., Hagiwara, T., Myles, B. S., Simpson, R. L., Brick, M. L., & Griswold, D. E. (2000). Parent, teacher, and self-report of problem and adaptive behaviors in children and adolescents with Asperger syndrome. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 25(2), 147–167.

*Blakeley-Smith, A., Reaven, J., Ridge, K., & Hepburn, S. (2012). Parent–child agreement of anxiety symptoms in youth with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(2), 707–716.

*Butterworth, T. W., Hodge, M. A. R., Sofronoff, K., Beaumont, R., Gray, K. M., Roberts, J., et al. (2013). Validation of the emotion regulation and social skills questionnaire for young people with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-2014-5.

Card, N. E. (2012). Applied meta-analysis for social science research. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

*Cohen, I. L., Schmidt-Lackner, S., Romanczyk, R., & Sudhalter, V. (2003). The PDD behavior inventory: A rating scale for assessing response to intervention in children with pervasive developmental disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33(1), 31–45.

*Constantino, J. N., Przybeck, T., Friesen, D., & Todd, R. D. (2000). Reciprocal social behavior in children with and without pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 21(1), 2–11.

de Bildt, A., Serra, M., Kraijer, D., Sytema, S., & Minderaa, R. (2005). Social skills in children with intellectual disabilities with and without autism. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49, 317–328.

De Los Reyes, A. (2011). Introduction to the special section: More than measurement error: Discovering meaning behind informant discrepancies in clinical assessments of children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 40, 1–9.

De Los Reyes, A., Henry, D. B., Tolan, P. H., & Wakschlag, L. S. (2009). Linking informant discrepancies to observed variations in young children’s disruptive behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 637–652.

De Los Reyes, A., & Kazdin, A. E. (2005). Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 483–509.

*Deb, S., Dhaliwal, A.-J., & Roy, M. (2008). The usefulness of Conners’ Rating Scales-Revised in screening for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children with intellectual disabilities and borderline intelligence. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 52(11), 950–965.

*Dekker, M. C., Nunn, R., & Koot, H. M. (2002). Psychometric properties of the Revised Developmental Behaviour Checklist scales in Dutch children with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 46(1), 61–75.

*Douma, J. C. H., Dekker, M. C., Verhulst, F. C., & Koot, H. M. (2006). Self-reports on mental health problems of youth with moderate to borderline intellectual disabilities. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 45(10), 1224–1231.

Duhig, A. M., Renk, K., Epstein, M. K., & Phares, V. (2000). Interparental agreement on internalizing, externalizing and total behavior problems: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 7, 435–453.

Einfeld, S. L., Piccinin, A. M., Mackinnon, A., Hofer, S. M., Taffe, J., Gray, K. M., et al. (2006). Psychopathology in young people with intellectual disability. Journal of the American Medical Association, 296, 1981–1989.

Elsabbagh, M., Divan, G., Koh, Y.-J., Kim, Y. S., Kauchali, S., Marcín, C., et al. (2012). Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Autism Research, 5, 160–179.

*Embregts, P. J. C. M. (2000). Reliability of the child behavior checklist for the assessment of behavioral problems of children and youth with mild mental retardation. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 21(1), 31–41.

*Emerson, E. (2005). Use of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire to assess the mental health needs of children and adolescents with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 30(1), 14–23.

*Farmer, C. A., & Aman, M. G. (2010). Psychometric properties of the Children’s Scale of hostility and aggression: Reactive/proactive (C-SHARP). Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31(1), 270–280.

*Farrugia, S., & Hudson, J. (2006). Anxiety in adolescents with Asperger syndrome: Negative thoughts, behavioral problems, and life interference. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 21(1), 25–35.

Ferdinand, R. F., van der Ende, J., & Verhulst, F. C. (2004). Parent–adolescent disagreement regarding psychopathology in adolescents from the general population as a risk factor for adverse outcome. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 113, 198–206.

Ferdinand, R. F., van der Ende, J., & Verhulst, F. C. (2006). Prognostic value of parent–adolescent disagreement in a referred sample. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 15, 156–162.

Fisher, R. A. (1938). Statistical methods for research workers (7th ed.). Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd.

*Greenaway, R., & Howlin, P. (2010). Dysfunctional attitudes and perfectionism and their relationship to anxious and depressive symptoms in boys with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40, 1179–1187.

*Hallett, V., Ronald, A., Colvert, E., Ames, C., Woodhouse, E., Lietz, S., et al. (2013). Exploring anxiety symptoms in a large-scale twin study of children with autism spectrum disorders, their co-twins and controls. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54, 1176–1185.

*Hardiman, S., Guerin, S., & Fitzsimons, E. (2009). A comparison of the social competence of children with moderate intellectual disability in inclusive versus segregated school settings. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 30(2), 397–407.

Hartley, A. G., Zakriski, A. L., & Wright, J. C. (2011). Probing the depths of informant discrepancies: Contextual influences on divergence and convergence. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 40, 54–66.

Hedges, L. V. (1982). Fitting categorical models to effect sizes from a series of experiments. Journal of Educational Statistics, 7, 119–137.

Hedges, L. V., & Olkin, I. (1985). Statistical methods for meta-analysis. Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

*Hellings, J. A., Nickel, E. J., Weckbaugh, M., McCarter, K., Mosier, M., & Schroeder, S. R. (2005). The Overt Aggression Scale for rating aggression in outpatient youth with autistic disorder: Preliminary findings. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 17(1), 29–35.

Hoyt, W. T. (2000). Rater bias in psychological research: When is it a problem and what can we do about it? Psychological Methods, 5, 64–86.

*Hurtig, T., Kuusikko, S., Mattila, M., Haapsamo, H., Ebeling, H., Jussila, K., et al. (2009). Multi-informant reports of psychiatric symptoms among high-functioning adolescents with Asperger syndrome or autism. Autism, 13(6), 583–598.

Israel, P., Thomsen, P. H., Langeveld, J. H., & Stormark, K. M. (2007). Parent–youth discrepancy in the assessment and treatment of youth in usual clinical care setting: Consequences to parent involvement. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 16, 138–148.

*Jepsen, M. I., Gray, K. M., & Taffe, J. R. (2012). Agreement in multi-informant assessment of behaviour and emotional problems and social functioning in adolescents with autistic and Asperger’s disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6(3), 1091–1098.

*Johnson, S. A., Filliter, J. H., & Murphy, R. R. (2009). Discrepancies between self- and parent-perceptions of autistic traits and empathy in high functioning children and adolescents on the autism spectrum. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(12), 1706–1714.

*Kalyva, E. (2010). Multirater congruence on the social skills assessment of children with Asperger syndrome: Self, mother, father, and teacher ratings. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(10), 1202–1208.

*Kanne, S. M., Abbacchi, A. M., & Constantino, J. N. (2009). Multi-informant ratings of psychiatric symptom severity in children with autism spectrum disorders: The importance of environmental context. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39(6), 856–864.

*Knott, F., Dunlop, A.-W., & Mackay, T. (2006). Living with ASD: How do children and their parents assess their difficulties with social interaction and understanding? Autism, 10, 609–617.

*Koning, C., & Magill-Evans, J. (2001). Social and language skills in adolescent boys with Asperger syndrome. Autism, 5(1), 23–36.

*Lane, B. R., Paynter, J., & Sharman, R. (2013). Parent and teacher ratings of adaptive and challenging behaviours in young children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7, 1196–1203.

Lecavalier, L. (2006). Behavioral and emotional problems in young people with pervasive developmental disorders: Relative prevalence, effects of subject characteristics, and empirical classification. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36, 1101–1114.

*Lecavalier, L., Gadow, K. D., Devincent, C. J., Houts, C. R., & Edwards, M. C. (2011). Validity of DSM-IV syndromes in preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 15(5), 527–543.

*Lecavalier, L., Leone, S., & Wiltz, J. (2006). The impact of behaviour problems on caregiver stress in young people with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 50(3), 172–183.

Lipsey, M. W., & Wilson, D. B. (2001). Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

*Locke, J., Kasari, C., & Wood, J. J. (2014). Assessing social skills in early elementary-aged children with autism spectrum disorders: The social skills Q-sort. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 32, 62–76.

*Lopata, C., Toomey, J. A., Fox, J. D., Volker, M. A., Chow, S. Y., Thomeer, M. L., et al. (2010). Anxiety and depression in children with HFASDs: Symptom levels and source differences. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(6), 765–776.

*Macintosh, K., & Dissanayake, C. (2006). Social skills and problem behaviours in school aged children with high-functioning autism and Asperger’s disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(8), 1065–1076.

*Magiati, I., Chan, J. Y., Tan, W.-L. J., & Poon, K. K. (2014). Do non-referred young people with autism spectrum disorders and their caregivers agree when reporting anxiety symptoms? A preliminary investigation using the Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8, 546–558.

Mash, E. J., & Hunsley, J. (2005). Evidence-based assessment of child and adolescent disorders: Issues and challenges. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 34, 362–379.

*Matson, J. L., Horovitz, M., Mahan, S., & Fodstad, J. (2013). Reliability of the Matson evaluation of social skills with youngsters (MESSY) for children with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7, 405–410.

*Mazefsky, C. A., Borue, X., Day, T. N., & Minshew, N. J. (2014). Emotion regulation patterns in adolescents with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder: Comparison to typically developing adolescents and association with psychiatric symptoms. Autism Research, 7, 344–354.

McGraw, K. O., & Wong, S. P. (1996). Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychological Methods, 1, 30–46.

*Miller, M. L., Fee, V. E., & Jones, C. J. (2004). Psychometric properties of ADHD rating scales among children with mental retardation II: Validity. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 25(5), 477–492.

*Murray, D. S., Ruble, L. A., Willis, H., & Molloy, C. A. (2009). Parent and teacher report of social skills in children with autism spectrum disorders. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 40(2), 109–115.

*Ozsivadjian, A., Hibberd, C., & Hollocks, M. J. (2013). Brief report: The use of self-report measures in young people with autism spectrum disorder to assess symptoms of anxiety, depression and negative thoughts. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-1937-1.

Panichelli-Mindel, S. M., Flannery-Schroeder, E., Kendall, P. C., & Angelosante, A. G. (2005). Disclosure of distress among anxiety-disordered youth: Differences in treatment outcome. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 19, 403–422.

*Pearson, D. A., Aman, M. G., Arnold, L. E., Lane, D. M., Loveland, K. A., Santos, C. W., et al. (2012). High concordance of parent and teacher attention—deficit/hyperactivity disorder ratings in medicated and unmedicated children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 22(4), 284–291.

*Reed, P., & Osborne, L. A. (2012). The role of parenting stress in discrepancies between parent and teacher ratings of behavior problems in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(2), 471–477.

Renk, K., & Phares, V. (2004). Cross-informant ratings of social competence in children and adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review, 24, 239–254.

*Renno, P., & Wood, J. J. (2013). Discriminant and convergent validity of the anxiety construct in children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 2135–2146.

*Reszka, S. S., Boyd, B. A., McBee, M., Hume, K. A., & Odom, S. L. (2013). Brief report: Concurrent validity of autism symptom severity measures. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-1879-7.

*Rojahn, J., Rowe, E. W., Macken, J., Gray, A., Delitta, D., Booth, A., et al. (2010). Psychometric evaluation of the behavior problems inventory-01 and the Nisonger child behavior rating form with children and adolescents. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 3(1), 28–50.

Rosenthal, R. (1991). Meta-analytic procedures for social research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

*Schanding, G. T., Nowell, K. P., & Goin-Kochel, R. (2012). Utility of the Social Communication Questionnaire—Current and Social Responsiveness Scale as teacher-report screening tools for autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42(8), 1705–1716.

*Tassé, M. J., & Lecavalier, L. (2000). Comparing parent and teacher ratings of social competence and problem behaviors. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 105(4), 252–259.

*van Steensel, F. J. A., Deutschman, A. A. C. G., & Bögels, S. M. (2013). Examining the screen for child anxiety-related emotional disorder-71 as an assessment tool for anxiety in children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 17, 681–692.

*Vickerstaff, S., Heriot, S., Wong, M., Lopes, A., & Dossetor, D. (2007). Intellectual ability, self-perceived social competence, and depressive symptomatology in children with high-functioning autistic spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(9), 1647–1664.

*White, S. W., Schry, A. R., & Maddox, B. B. (2012). Brief report: The assessment of anxiety in high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 1138–1145.

Wolf, F. M. (1986). Meta-analysis: Quantitative methods for research synthesis. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Steven Beck, Marc Tassé, and Michael Vasey for their feedback and helpful comments related to this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stratis, E.A., Lecavalier, L. Informant Agreement for Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder or Intellectual Disability: A Meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord 45, 1026–1041 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2258-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2258-8