Abstract

Trait impulsivity is an established risk factor for externalizing behavior problems in adolescence, but little is understood about the cognitive mechanisms involved. Negative automatic thoughts are associated with externalizing behaviors and impulsivity is associated with less cognitive reappraisal. This study sought to adapt the bioSocial Cognitive Theory (bSCT) of impulsivity and substance use (an externalizing behavior) for externalizing behavior in general. It was predicted that only the component of impulsivity characterized by lack of forethought (rash impulsiveness; RI) would be associated with (non-substance use-related) externalizing behaviors, not reward sensitivity/drive. Further, this association would be mediated by negative automatic thoughts. Participants were 404 (226 female, 63%) adolescents from 6 high schools across South-East Queensland (age = 13–17 years, mean age = 14.97 years, SD = 0.65 years) of mostly Australian/New Zealand (76%) or European (11%) descent. Participants completed self-report measures of impulsivity, negative automatic thoughts, and externalizing behaviors. Path analysis revealed that, as predicted, only RI was uniquely associated with negative automatic thoughts and externalizing behaviors. However, only negative automatic thoughts centered around hostility mediated the positive association between RI and externalizing behaviors, with the indirect mediation effect being smaller than the direct association. In contrast to substance use, only one component of impulsivity, RI, was associated with general adolescent externalizing behavior. Hostile automatic thoughts may be an important mechanism of risk, supporting a role for cognitive-behavioral interventions. Other biopsychosocial mechanisms are clearly involved and the bSCT may provide a useful framework to guide future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Externalizing behaviors in childhood and adolescence, such as delinquency, hyperactivity, and aggression, have been linked to criminal offending in adulthood (Liu 2004), poorer educational outcomes (Moffitt et al. 2011), and the perpetration of domestic violence in later life (Makin-Byrd et al. 2013). Prominent theories describe a complex interplay of biopsychosocial determinants in producing externalizing behavior that include a role for biologically-based traits in biasing mental processes (i.e., cognition) that are more proximally linked to behavior (Dodge and Pettit 2003; Frick and Viding 2009). While impulsivity is an established biologically-based risk factor for externalizing behavior, few studies have investigated how it may bias cognition to produce externalizing behavior (Castellanos-Ryan and Conrod 2011; Thompson et al. 2014). Understanding the specific cognitive mechanisms through which impulsivity conveys risk could not only have important implications for prominent theories of externalizing problems, but also allow for more effective targeting of this biologically-based risk factor (Frick 2001). A similar line of research has aided the development of new interventions for adolescent alcohol misuse, a form of externalizing behavior related to impulsivity (O’Leary-Barrett et al. 2016).

It has been proposed that trait impulsivity comprises at least two distinct components: rash impulsiveness (RI) and reward drive (RD; Dawe et al. 2004). While RI is associated with disinhibition and reflects the tendency to act without forethought or consideration of consequences, RD is associated with increased sensitivity to rewarding stimuli, such as the positive sensations resulting from drug and alcohol consumption. Alternative models of impulsivity have been proposed and do differ in the number of included components (Whiteside and Lynam 2001; Cross et al. 2011; Hamilton et al. 2015a; Hamilton et al. 2015b). Here, we focus on the two-factor model proposed by Dawe et al. (2004) as a parsimonious account of impulsivity that has been applied to externalizing behaviors related to substance use, and has also been extended to include influences on (explicit) cognition, a major focus of the present study (Boog et al. 2014; Gullo et al. 2010; Stautz et al. 2017). While many impulsivity traits show zero-order associations with externalizing behaviours (Berg et al. 2015), only RI-related traits tend to be uniquely associated with (non-substance use-related) externalizing behaviors (Castellanos-Ryan and Conrod 2011; Castellanos-Ryan et al. 2014). A better understanding of the cognitive mechanisms underlying this association could lead to better targeted intervention (Frick 2001).

Prominent theories of (non-substance) externalizing problems tend to focus on specific domains of social cognition, such as social problem-solving deficits, hostile attribution biases, and aggression outcome expectancies (Dodge and Pettit 2003; Frick and Viding 2009). For example, Dodge’s Social Information Processing Model (Dodge and Pettit 2003) includes a pathway through which biological predisposition can affect mental processes like cognition, but does not specify a unique role for impulsivity or its cognitive targets. While these social-cognitive domains are theorized to be affected by biological predisposition, it is perhaps not by impulsivity. For example, while callous/unemotional traits are associated with positive aggression outcome expectancies and values, impulsivity-like traits are not (Pardini et al. 2003). Instead, impulsivity has been associated with more general cognitive distortions (Chabrol et al. 2011), which have been less of a focus in previous research but may also be important to the development and maintenance of externalizing problems (Zadeh et al. 2007).

Cognitive distortions are inaccurate conscious thoughts/beliefs, often related to maladaptive behavior (Bhar et al. 2012; Beck and Haigh 2014). Several researchers have highlighted their role in causing antisocial acts (e.g., moral justification cognitions) and perpetuating them (e.g., blaming others) by protecting the individual from experiencing guilt/blame (Bandura et al. 1996; Barriga and Gibbs 1996). A meta-analysis by Helmond et al. (2015) found a significant medium-to-large association between cognitive distortions and externalizing behaviour (d = .70). Furthermore, they found that interventions for externalizing problems produce a significant reduction in cognitive distortions (d = .27). It may be through these more general cognitive distortions that traits like RI contribute to externalizing behavior. This would be consistent with, and complementary to, biopsychosocial models of externalizing problems with a more specific focus on social information processing (e.g., Dodge and Pettit 2003; Frick and Viding 2009).

Examining broader cognitive domains has proven valuable in understanding the link between impulsivity and externalizing behaviors related to substance use. Previous studies testing bioSocial Cognitive Theory (bSCT) have found that distinct domains of cognition are uniquely related to, and mediate the effects of, RD and RI (see Gullo et al. 2010; Harnett et al. 2013; & Papinczak et al. 2018). Specifically, self-efficacy has been found to mediate the relationship between RI and substance use, while positive drug outcome expectancies have been found to mediate the relationship between RD and substance use (Gullo et al. 2010). In the former case, those high in RI, being predisposed to acting on impulse without inhibition or forethought, would generally not have as many experiences in which they have refused to act, which, in turn, would limit the amount of past experiences on which confidence in their ability to refuse alcohol/drugs could be based. The differential association of impulsivity traits with distinct domains of cognition reveals new, potentially valuable, avenues for targeted intervention for substance use.

Theoretically, RI should bias cognition more generally and in ways that increase other externalizing behaviors. Given that lack of forethought and reflection on consequences typifies RI, it may well be that lack of reflection on automatically-activated (distorted) cognitions mediates the RI-externalizing behaviors relationship. That is, those high in RI may be less likely to reflect on the first (“automatic”) thoughts that enter conscious processing after an event, which, when inaccurate, could lead to antisocial actions. Consistent with this, cognitive distortions have been associated with both externalizing behaviors and impulsivity (e.g., Castellanos-Ryan and Conrod 2011; Chabrol et al. 2011; Thompson et al. 2014).

Schniering and Rapee (2002) conceptualized cognitive distortions in children, which they refer to as negative automatic thoughts, as comprising four factors: physical and social threat, personal failure, and hostility. Theory and empirical evidence supports specific associations between impulsivity traits and negative automatic thoughts (reviewed below). Figure 1 depicts the hypothesized relationship between impulsivity, cognition, and externalizing behavior.

Rash Impulsiveness and Physical and Social Threat

It may be that those high in RI engage in externalizing behaviors in an effort to rid themselves of the intense negative emotions brought on by automatic thoughts centered around physical and social threat, regardless of the potential detriments (Gagnon et al. 2013; Moeller et al. 2001). Such behaviors would be negatively reinforcing in the short-term, but (intermittently) punishing in the longer-term. Thompson et al. (2014), using a measure of impulsivity closely reflecting RI, found that higher levels were associated with higher threat appraisal. Further, both impulsivity and threat appraisal were found to be associated with higher levels of externalizing behaviors. The association between RI and externalizing behaviors could be mediated, in part, by automatic thoughts of perceived physical and social threat.

Rash Impulsiveness and Personal Failure

Automatic thoughts of personal failure may also mediate the relationship between RI and externalizing behaviors. RI can lead to engaging in activities that are not planned and where no assessment has been undertaken as to the likelihood of success, making failure more likely. A series of laboratory studies conducted by Newman and colleagues found evidence consistent with this, combined with a reduced capacity to learn from mistakes (for a review, see Patterson et al. 1993). Moffitt et al. (2011) suggested those high in RI are more likely to continue to act without forethought and not reflect on why they have failed in the past, perpetuating a pattern of failure. This would increase the frequency of automatic thoughts of failure.

Castagna et al. (2017) found that, in a sample of children diagnosed with Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, higher levels of impulsivity were associated with a higher number of automatic thoughts of personal failure. Castellanos-Ryan et al. (2016) reported an association between RI and hopelessness in a large community-based sample of adolescents (r = .19, p < 0.001, N = 2144). Hopelessness, which is characterized by low mood, worthlessness, and negative beliefs about oneself (Conrod et al. 2000), has been associated with higher levels of externalizing behaviors (Castellanos-Ryan and Conrod 2011). Thus, the pattern of findings is not inconsistent with an association between RI and greater automatic thoughts of failure, which is associated with externalizing behavior.

Rash Impulsiveness and Hostile Automatic Thoughts

Theoretically, high RI should predict more hostile automatic thoughts. While previous research has found that the attribution of hostile intent to others is a significant predictor of externalising behaviors (Dodge and Somberg 1987), Schniering and Rapee’s (2002) conceptualization captures a broader range of cognitions, reflecting the hostile automatic thoughts of the subject (e.g., “I have the right to take revenge on people if they deserve it”), as much as the subject’s attribution of hostile intent to others (e.g., “Most people are against me”). Schniering and Rapee found that their hostility subscale accurately discriminated between those children with behavioral disorders and other children (non-clinical controls, anxious, and depressed children), suggesting that hostility is uniquely associated with externalizing behaviors. Further, the measure of threat appraisal used by Thompson et al. (2014), found to be associated with greater externalizing behaviors, included ‘harm to others’, which would map onto the hostility subscale. Calvete and Cardeñoso (2005) found that both justification of violence, a measure reflecting hostile thoughts, as well as RI, accounted for significant variance in the delinquent behavior of those who suffered maltreatment in childhood. These findings suggest that hostile automatic thoughts may mediate the association between RI and externalizing behaviors.

Reward Drive and Externalizing Behavior

Goodwin et al. (2016) suggested those high in RD are motivated in large part by a desire to distinguish themselves socially in a desirable way. In support of this, Knyazev (2004) found that adolescents high in RD may be more likely to engage in externalizing behaviors (in this instance, drug and alcohol use) to enhance their social status. Indeed, RD, but not RI, has been uniquely linked to this kind of positive expectancy (Gullo et al. 2010; Papinczak et al. 2018; Patton et al. 2018). Therefore, no direct (unique) association between RD and externalizing behaviors is expected, at least in the absence of controlling for the perceived desirability of the expected outcome of the externalizing behaviors. The present study tested an adaptation of the bioSocial Cognitive Theory (bSCT; Gullo et al. 2010) of substance use to (non-substance) externalizing behavior. It predicted: 1) RI, but not RD, would be directly associated with externalizing behaviors; 2) the association between RI and externalizing behaviors would be partially mediated by negative automatic thoughts of perceived physical threat, perceived social threat, personal failure, and hostility.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants in the present study were sourced from a school-based alcohol use prevention randomized control trial (RCT; see Patton et al. 2019, for further details). Participants were 404 Grade 9 and 10 students from 6 schools across metropolitan South-East Queensland, Australia (age = 13–17 years, mean age = 14.97 years, SD = 0.65 years, N female = 226 [63%]). The majority (89%) of participants were born in Australia and spoke English at home (93%). Parental background was mostly Australian or New Zealander (76%), European (11%), or Asian (7%). Participation in the RCT was voluntary with anonymized data collection. Assessment measures used in the current study were completed as part of baseline data collection in the RCT.

Measures

Rash Impulsiveness

RI was measured using the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-Brief (Steinberg et al. 2013). The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-Brief is an adaptation of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (version 11) developed by Patton et al. (1995). The self-report questionnaire consists of 8 items (e.g., “I do things without thinking”) which are scored on a 4-point Likert scale from rarely/never (1) to almost always/always (4). The total score ranges from 8 to 32, with higher scores indicating higher rash impulsivity. The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-Brief has demonstrated acceptable internal reliability and was as capable as the full Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (version 11) in distinguishing patients with impulsivity-related disorders (e.g., borderline personality disorder) from controls (Steinberg et al. 2013). It has been validated in adolescent samples (Charles et al. 2019).

Reward Drive

RD was measured using the short-form Sensitivity to Reward scale from the short-form Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire (Cooper and Gomez 2008). The short-form Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire is an adaptation of the Sensitivity to Punishment and Sensitivity to Reward Questionnaire developed by Torrubia et al. (2001). The self-report scale consists of 10 items (e.g., “Do you often do things to be praised?”) with a dichotomous “yes/no” response option. The total score ranges from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating higher reward drive. The short-form Sensitivity to Reward scale has been shown to correlate highly with the full scale (r = .91) and have acceptable internal reliability (Cooper and Gomez 2008). It has been shown to have good test-retest reliability and internal consistency in adolescents (Patton et al. 2019).

Negative Automatic Thoughts

Automatic thoughts were measured using the Children’s Automatic Thoughts Scale (Schniering and Rapee 2002). The self-report questionnaire consists of 40 items which are scored on a 5-point Likert scale from not at all (0) to all the time (4). Four subscales consisting of 10 items each assess negative automatic thoughts: physical threat (e.g., “I’m going to have an accident”), social threat (e.g., “Kids will think I’m stupid”), personal failure (e.g., “I can’t do anything right”), and hostility (e.g., “I have the right to take revenge on people if they deserve it”). Each subscale score ranges from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating a higher number of negative automatic thoughts. Each subscale has demonstrated good internal reliability in children and adolescents (Hogendoorn et al. 2010).

Externalizing Behaviors

Externalizing behaviors were measured using the ‘externalizing’ scale of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman et al. 2010). The externalizing subscale consists of 10 items: five from the ‘behavioral/conduct problems’ subscale (e.g., “I get very angry and often lose my temper“) and five from the ‘hyperactivity’ subscale (e.g., “I am restless, I find it hard to sit down for long“) of the original, five-subscale Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (Goodman 1997). Each item is scored on a 3-point Likert scale from not true (0) to certainly true (2). Thus, the total score ranges from 0 to 20, with higher scores indicating higher levels of externalizing behaviors. The externalizing subscale has demonstrated good convergent and discriminant validity in children and adolescents (Goodman et al. 2010).

Data Analysis

The hypothesized model was tested with path analysis in AMOS (version 24) using maximum likelihood estimation. The comparative fit index (CFI) and root mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA) were used to evaluate model fit (Bentler 2007). The following rules-of-thumb were employed to evaluate “good” model fit: CFI ≥ .95, RMSEA ≤ 0.06. “Adequate” fit was determined as: CFI ≥ .90, RMSEA ≤ .10.

The χ2 test was also conducted (α = 0.05), although it typically overestimates poor fit in large samples (Bentler 2007; Hu and Bentler 1999). Mediation was tested in two ways. First, the hypothesized model (partial mediation) was compared to an alternative full mediation model in which a direct effect of RI on externalizing behaviors was omitted, using the chi-square difference test (Δχ2; Holmbeck 1997). The Akaike (1987) Information Criterion (AIC) was also used in model comparison, where smaller values indicate a model is better-fitting and more parsimonious. Second, the mediation effect itself was estimated with PRODCLIN (MacKinnon et al. 2007) using the distribution-of-the-product method, which is the optimal approach to test mediation (MacKinnon et al. 2002). Lastly, while no moderation effects of sex were anticipated a priori, this was evaluated using invariance testing within a multi-group model (Holmbeck 1997). Missing data was addressed with full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML), an optimal approach for handling missing data (Graham 2009). Multicollinearity was examined through inspection of predictor covariances, Variance Information Factor (VIF), and Condition Index statistics. None exceeded recommended values (Berry et al. 1985; Chatterjee and Hadi 2015).

The hypothesized model is depicted in Fig. 2. Variables of interest were modelled as measured variables. Each of the domains of negative automatic thoughts were specified to have a direct association with externalizing behaviors. Rash impulsiveness (RI) was modelled as an exogenous variable with direct paths to all domains of negative automatic thoughts and externalizing behavior. Reward drive (RD) was not expected to significantly predict automatic thoughts or externalizing behaviors and was modelled as an exogenous variable that covaried with RI. Residual covariances between all automatic thoughts domains were specified.

Results

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations between variables of interest are presented in Table 1. A small number of participants (4%; n = 15) reported no externalizing behaviour on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. This was driven primarily by endorsement of Hyperactivity (7% reported no hyperactivity; n = 28) rather than Conduct Problems (25% reported no Conduct Problems; n = 100).

Hypothesized Model

The hypothesized model of RI, automatic thoughts, and externalizing behaviors showed a moderately good fit to the data (see Table 2, Model 1). Model fit was significantly reduced by the removal of the direct path from RI to externalizing behaviors (i.e., full mediation), Δχ2 (1) = 213.34, p < 0.001. This model was found to provide a poor fit to the data (see Table 2, Model 2). To further test the unique association of RI with externalizing behaviors, an alternative model specifying a direct effect of RD on externalizing behaviors was also estimated (see Table 2, Model 3). While this alternative model provided a moderately good fit to the data, the Δχ2 was not statistically significant and the AIC was higher, which favors the more parsimonious hypothesized model omitting the RD path. Indeed, the pathway from RD to externalizing behaviors was not statistically significant (standardized coefficient = 0.01, p = .74). In summary, the partial mediation model specifying direct and indirect associations between RI and externalizing behaviors only (Table 2, Model 1) provided the best fit to the data and was retained.

As shown in Fig. 2, RI was significantly associated with greater externalizing behaviors (unstandardized coefficient = 0.53, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001). It was also significantly associated with greater negative automatic thoughts across all domains (ps < 0.001). However, only thoughts relating to hostility (unstandardized coefficient = 0.11, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001) and social threat (unstandardized coefficient = −0.06, SE = 0.02, p = 0.007) were uniquely associated with externalizing behaviors, but in opposing directions: while increased thoughts related to hostility were associated with higher externalizing symptoms, greater thoughts related to social threat were associated with lower symptoms. The model accounted for 58.5% of the variance in externalizing behaviors.

Only thoughts concerning hostility and social threat were directly related to both RI and externalizing behaviors. Hostility intent partially mediated the positive association between RI and externalizing behaviors (unstandardized mediation effect 95% CI[0.04, 0.11]; standardized coefficient [ab] = 0.09). The association between RI and externalizing behaviors was also partially mediated by thoughts concerning social threat (unstandardized mediation effect 95% CI[−0.06, −0.01]; standardized coefficient [ab] = −0.04). This pathway may be protective, with RI associated with less externalizing behavior due to its association with greater social threat thoughts. The standardized total effect of RI on externalizing behavior was .73, comprising a standardized direct effect of .63 (86.4%) and a standardized indirect effect (through cognition) of .10 (13.6%).

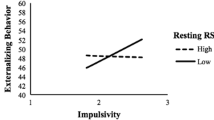

There was some overlap in item content on the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-Brief (RI measure) and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire Hyperactivity subscale, which formed part of the externalizing behavior score, e.g., “I do things without thinking” (Barratt Impulsiveness Scale-Brief) and “I think before I do things” (Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire Hyperactivity subscale). To determine whether this may have affected the results, the model was reanalyzed with the overlapping items removed from the externalizing behaviors scale and then again with only the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire Behavior/Conduct Problems subscale as the outcome. Findings were consistent with the model reported, in that, model fit was good and there were no differences in the statistical significance of model pathways. Lastly, no sex differences were hypothesized and invariance testing revealed only minor differences in effect sizes of pathways between RI and physical and social threat, with stronger RI-physical threat associations in girls (standardized coefficient = .46, compared to .29 in boys, Δχ2 (1) = 7.36, p = 0.007) and stronger RI-social threat associations in boys (standardized coefficient = .35, compared to .22 in girls, Δχ2 (1) = 15.67, p < 0.001). However, pathways were statistically significant in both boys and girls.

Discussion

This study sought to test a new bioSocial Cognitive Theory (bSCT) of impulsivity and externalizing behavior adapted from the addiction literature. It was predicted that one domain of impulsivity, RI, would be uniquely associated with non-substance use-related externalizing behaviors and that the association would be mediated by negative automatic thoughts. Findings complement predominant biopsychosocial models of externalizing problems (e.g., Dodge and Pettit 2003; Frick and Viding 2009) by providing preliminary evidence of a specific pathway linking certain impulsivity traits to more general cognitive processes related to externalizing behavior. As predicted, in the present study only RI was associated with higher levels of externalizing behaviors and negative automatic thoughts. This result not only corroborates the previous findings of Castellanos-Ryan and Conrod (2011) and Castellanos-Ryan et al. (2014), but also supports the utility of a two-factor model of trait impulsivity (Dawe et al. 2004). Taken together with previous studies (e.g., Boog et al. 2014; ; Castellanos-Ryan and Conrod 2011; Stautz et al. 2017), the results of the present study provide further evidence for the conclusion that while both RI and RD are associated with substance use, only RI is associated with other components of externalizing behavior (conduct problems and hyperactivity). Furthermore, the results of the present study suggest that this relationship is due, in part, to RI’s association with hostile automatic thoughts in particular.

Rash impulsiveness (RI), but not RD, was positively and uniquely associated with all domains of negative automatic thoughts. However, only hostile automatic thoughts were positively associated with externalizing behaviors. This provides partial support for the prediction of the mediating role of negative automatic thoughts. Social threat was also associated with externalizing behaviors but, surprisingly, may act as a protective factor rather than as a predictor of risk. This may be because those tending to perceive greater social threat are more likely to respond by withdrawing, rather than acting out externally (e.g., Cacioppo and Hawkley 2009; Lessard and Juvonen 2018).

Our findings indicate that at least some of the individual variation in the RI-externalizing behaviors relationship is accounted for by variation in cognitions centered around hostility. That is, RI tends to predict hostile cognitions which, in turn, tend to predict externalizing behaviors. Therefore, there is some basis for suggesting that interventions targeting hostile cognitions specifically may reduce externalizing behaviors in those high in RI. Previous studies have found that cognitive behavioral therapy-based interventions reduce hostility (Campo et al. 2008; Chen et al. 2014), as well as externalizing behaviors (Chen et al. 2014). A recent study by Henwood et al. (2018) found that a short-term one-to-one cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness program targeting anger reduced feelings of vengeance (that is, seeking retribution against others) in young offenders. However, while reduced hostility was an incidental outcome of more general CBT protocols, it does not appear that any hostility-specific CBT protocol has been developed for adolescents (Chen et al. 2014). There is evidence for the effectiveness of CBT targeting hostility in adults, but its superiority to more general CBT programs remains unknown (Del Vecchio and O’Leary 2004; Sloan et al. 2010; Sukhodolsky et al. 2004). Our results suggest that the development of a short CBT intervention specifically addressing distorted automatic hostile cognitions might reduce the prevalence of externalizing behaviors in those high in RI.

In predicting that greater frequency of automatic thoughts about physical threat, social threat, and personal failure would be associated with increased externalizing behaviors, we were informed by the findings of Thompson et al. (2014) with preadolescent children (8–12 years of age). Their measure of threat appraisal (which included dimensions similar to the subscales of the Children’s Automatic Thoughts Scale) was associated with higher levels of externalizing behaviors. In light of our findings we consider it more likely that the relationship found by Thompson et al. (2014) between threat appraisal and externalizing behaviors may have been driven predominantly by the ‘harm to others’ dimension of their measure (corresponding to the hostility subscale of Children’s Automatic Thoughts Scale). This is because, consistent with Schniering and Rapee (2002), we found that only the hostility subscale of Children’s Automatic Thoughts Scale was uniquely associated with greater externalizing behaviors and, further, the high levels of intercorrelation between Children’s Automatic Thoughts Scale subscales makes misattribution likely if analyses do not effectively control for shared variance among subdomains of automatic thoughts. In summary, while many classes of negative automatic thoughts may show zero-order correlations with externalizing behaviours, only hostile automatic thoughts may be uniquely related to them, as was the case in the current study.

Despite our finding that automatic cognitions reflecting hostility partially mediated the RI-externalizing behaviors association, the direct association between RI and externalizing behaviors remained both large and significant even after controlling for cognition. Clearly, there are other mechanisms accounting for the relationship between RI and externalizing behaviors. Our results provide some support for the notion that cognition is one mechanism, even if not exclusively negative automatic thoughts. Other domains of explicit cognition may be relevant, and the pathways studied here exist within a larger, complex, biopsychosocial system (Dodge and Pettit 2003; Frick and Viding 2009).

Self-efficacy to resist acting on hostile automatic thoughts may be an additional cognitive mediator of the association between impulsivity and externalizing behavior. In a series of studies, Gullo and colleagues have found that drug refusal self-efficacy mediates most of the association between RI and substance use (Gullo et al. 2010; Gullo et al. 2014; Leamy et al. 2016; Papinczak et al. 2018; Papinczak et al. 2019; Patton et al. 2018). It is possible that one’s confidence in their ability to resist an impulse to use alcohol/drugs is not too dissimilar in function to the confidence to resist acting on hostile automatic thoughts (i.e., self-efficacy). While not assessed in the current study, this form of self-efficacy might mediate the relationship between RI and externalizing behaviors in a similar way to the RI-substance use relationship. Indeed, Di Giunta et al. (2017) found that greater self-efficacy beliefs about anger regulation were associated with fewer concurrent externalizing symptoms in pre-adolescents. While this study did not measure trait impulsivity, and could therefore not test mediation, it does suggest that self-efficacy cognitions may play a significant role in the translation of hostile automatic thoughts to externalizing behaviors. This is worth exploring in future studies.

Alternatively, reappraisal of hostile automatic thoughts may also be an important mediating mechanism in the relationship between RI and externalizing behaviors. This would be consistent with meta-analytic findings that efficacious psychosocial treatments, many of which include cognitive reappraisal training, do reduce cognitive distortions (Helmond et al. 2015). Mauss et al. (2007) also found that individuals who regularly employ cognitive reframing are better able to regulate anger. It may be that reappraisal of, or reflection on, hostile automatic thoughts may distinguish those high in RI who do not engage in externalizing behaviors from those who do. The role of implicit and neurocognition would also be worth further investigation, such as response inhibition (e.g., Castellanos-Ryan et al. 2011) and working memory (Gunn and Finn 2015).

A limitation of the current study is the cross-sectional design, limiting conclusions about the direction of the associations between RI, externalizing behaviors, and hostile automatic thoughts. A longitudinal study would clarify the direction of the associations identified in the present study. It is likely that increases in externalizing behavior, and negative social responses to this, can produce further increases in hostile automatic thoughts (e.g., “Most people are against me”; Crick and Dodge 1994). However, it is perhaps less likely that changes in hostile thoughts affect personality traits like reward drive and rash impulsiveness. Further research into the existence and nature of reciprocal relationships across time is warranted. The nature of these associations may also be affected by the use of different coping strategies. How one copes with negative automatic thoughts may moderate the relationship between negative automatic thoughts and externalizing behaviors. That is, more frequent negative automatic thoughts may not translate to externalizing behaviors if one has an effective strategy for coping with those thoughts. However, the findings of Thompson et al. (2014) suggest that cognitive appraisals, rather than coping strategy, are more predictive of externalizing behaviors. It should also be noted that, being a non-clinical sample, frequency of hostile automatic thoughts and severity of externalizing behavior were relatively low, which may impact the generalizability of findings. The nature of the reported associations may differ in samples reporting more behaviour problems. The present study was interested in the association between impulsivity and specific domains of negative automatic thoughts to inform targeted intervention. Future research could explore differential associations between impulsivity traits and a higher-order negative automatic thoughts dimension (reflecting shared variance).

In conclusion, this study provides preliminary support for the application of a bioSocial Cognitive Theory (bSCT) of substance use to other externalizing behaviors. As predicted, RI was uniquely associated with externalizing behaviors and a range of negative automatic thoughts. Results highlight a potentially important role for hostile automatic thoughts as a mechanism of risk for externalizing behavior, although much of the latter’s association with impulsivity was unrelated to automatic thoughts. This study improves our understanding of the risk conveyed by biologically-based impulsivity traits and may provide a starting point for the development of new targeted interventions.

References

Akaike, H. (1987). Factor analysis and AIC. In Selected Papers of Hirotugu Akaike (pp. 371–386). Springer.

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 364–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.364.

Barriga, A. Q., & Gibbs, J. C. (1996). Measuring cognitive distortion in antisocial youth: Development and preliminary validation of the “how I think” questionnaire. Aggressive Behavior, 22(5), 333–343. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2337(1996)22:5<333::AID-AB2>3.0.CO;2-K.

Beck, A. T., & Haigh, E. A. P. (2014). Advances in cognitive theory and therapy: The generic cognitive model. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153734.

Bentler, P. M. (2007). On tests and indices for evaluating structural models. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(5), 825–829. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.09.024.

Berg, J. M., Latzman, R. D., Bliwise, N. G., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2015). Parsing the heterogeneity of impulsivity: A meta-analytic review of the behavioral implications of the UPPS for psychopathology. Psychological Assessment, 27(4), 1129–1146.

Berry, W. D., Feldman, S., & Feldman, S. (1985). Multiple regression in practice. SAGE.

Bhar, S. S., Beck, A. T., & Butler, A. C. (2012). Beliefs and personality disorders: An overview of the personality beliefs questionnaire. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(1), 88–100. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20856.

Boog, M., Goudriaan, A. E., Wetering, B. J. M. V. D., Polak, M., Deuss, H., & Franken, I. H. A. (2014). Rash impulsiveness and reward sensitivity as predictors of treatment outcome in male substance dependent patients. Addictive Behaviors, 39(11), 1670–1675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.02.020.

Cacioppo, J. T., & Hawkley, L. C. (2009). Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(10), 447–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005.

Calvete, E., & Cardeñoso, O. (2005). Gender differences in cognitive vulnerability to depression and behavior problems in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33(2), 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-005-1826-y.

Campo, A. E., Williams, V., Williams, R. B., Segundo, M. A., Lydston, D., & Weiss, S. M. (2008). Effects of LifeSkills training on medical students’ performance in dealing with complex clinical cases. Academic Psychiatry, 32(3), 188–194. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ap.32.3.188.

Castagna, P. J., Calamia, M., & Davis 3rd., T. E. (2017). Childhood ADHD and negative self-statements: Important differences associated with subtype and anxiety symptoms. Behavior Therapy, 48(6), 793–807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2017.05.002.

Castellanos-Ryan, N., & Conrod, P. J. (2011). Personality correlates of the common and unique variance across conduct disorder and substance misuse symptoms in adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(4), 563–576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9481-3.

Castellanos-Ryan, N., Rubia, K., & Conrod, P. J. (2011). Response inhibition and reward response Bias mediate the predictive relationships between impulsivity and sensation seeking and common and unique variance in conduct disorder and substance misuse. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 32(3), 188–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01331.x.

Castellanos-Ryan, N., Struve, M., Whelan, R., Banaschewski, T., Barker, G. J., Bokde, A. L. W., et al. (2014). Neural and cognitive correlates of the common and specific variance across externalizing problems in Young adolescence. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(12), 1310–1319. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13111499.

Castellanos-Ryan, N., The IMAGEN Consortium, Brière, F. N., O’Leary-Barrett, M., Banaschewski, T., Bokde, A., … Conrod, P. (2016). The structure of psychopathology in adolescence and its common personality and cognitive correlates. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 15(8), 1039–1052. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000193

Chatterjee, S., & Hadi, A. S. (2015). Regression analysis by example. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Charles, N. E., Floyd, P. N., & Barry, C. T. (2019). The structure, measurement invariance, and external validity of the Barratt impulsiveness scale–brief in a sample of at-risk adolescents. Assessment. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191119872259.

Chen, C., Li, C., Wang, H., Ou, J.-J., Zhou, J.-S., & Wang, X.-P. (2014). Cognitive behavioral therapy to reduce overt aggression behavior in Chinese young male violent offenders. Aggressive Behavior, 40(4), 329–336. doi : https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21521

Conrod, P. J., Stewart, S. H., Pihl, R. O., Côté, S., Fontaine, V., & Dongier, M. (2000). Efficacy of brief coping skills interventions that match different personality profiles of female substance abusers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 14(3), 231–242. https://doi.org/10.1037//0893-164X.14.3.231.

Cooper, A., & Gomez, R. (2008). The development of a short form of the sensitivity to punishment and sensitivity to reward questionnaire. Journal of Individual Differences, 29(2), 90–104. doi: https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001.29.2.90

Crick, N. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115(1), 74.

Cross, C. P., Copping, L. T., & Campbell, A. (2011). Sex differences in impulsivity: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 137(1), 97–130.

Dawe, S., Gullo, M. J., & Loxton, N. J. (2004). Reward drive and rash impulsiveness as dimensions of impulsivity: Implications for substance misuse. Addictive Behaviors, 29(7), 1389–1405. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.06.004

Del Vecchio, T., & O’Leary, K. D. (2004). Effectiveness of anger treatments for specific anger problems: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 24(1), 15–34.

Dodge, K. A., & Pettit, G. S. (2003). A biopsychosocial model of the development of chronic conduct problems in adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 39(2), 349–371. https://doi.org/10.1037//0012-1649.39.2.349.

Dodge, K. A., & Somberg, D. R. (1987). Hostile attributional biases among aggressive boys are exacerbated under conditions of threats to the self. Child Development, 58(1), 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1987.tb03501.x.

Frick, P. J. (2001). Effective interventions for children and adolescents with conduct disorder. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 46(7), 597–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370104600703.

Frick, P. J., & Viding, E. (2009). Antisocial behavior from a developmental psychopathology perspective. Development and Psychopathology, 21(4), 1111–1131.

Gagnon, J., Daelman, S., McDuff, P., & Kocka, A. (2013). UPPS dimensions of impulsivity. Journal of Individual Differences, 34(1), 48–55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000099

Giunta, L. D., Di Giunta, L., Iselin, A.-M. R., Eisenberg, N., Pastorelli, C., Gerbino, M., … Thartori, E. (2017). Measurement invariance and convergent validity of anger and sadness self-regulation among youth from six cultural groups. Assessment, 24(4), 484–502. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191115615214

Goodman, A., Lamping, D. L., & Ploubidis, G. B. (2010). When to use broader Internalising and Externalising subscales instead of the hypothesised five subscales on the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ): Data from British parents, teachers and children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(8), 1179–1191. doi : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-010-9434-x

Goodman, R. (1997). The strengths and difficulties questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38(5) 581–586. doi : https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x

Goodwin, B. C., Browne, M., Rockloff, M., & Loxton, N. (2016). Differential effects of reward drive and rash impulsivity on the consumption of a range of hedonic stimuli. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(2), 192–203. doi: https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.047

Graham, J. W. (2009). Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 549–576. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530.

Gullo, M. J., Dawe, S., Kambouropoulos, N., Staiger, P. K., & Jackson, C. J. (2010). Alcohol expectancies and drinking refusal self-efficacy mediate the association of impulsivity with alcohol misuse. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 34(8), 1386–1399. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01222.x

Gullo, M. J., St. John, N., Young, R. M., Saunders, J. B., Noble, E. P., & Connor, J. P. (2014). Impulsivity-related cognition in alcohol dependence: Is it moderated by DRD2/ANKK1 gene status and executive dysfunction? Addictive Behaviors, 39(11), 1663–1669. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.02.004

Gunn, R. L., & Finn, P. R. (2015). Applying a dual process model of self-regulation: The association between executive working memory capacity, negative urgency, and negative mood induction on pre-potent response inhibition. Personality and Individual Differences, 75, 210–215. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.033

Hamilton, K. R., Littlefield, A. K., Anastasio, N. C., Cunningham, K. A., Fink, L. H. L., Wing, V. C., Mathias, C. W., Lane, S. D., Schütz, C. G., Swann, A. C., Lejuez, C. W., Clark, L., Moeller, F. G., & Potenza, M. N. (2015a). Rapid-response impulsivity: Definitions, measurement issues, and clinical implications. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 6(2), 168–181.

Hamilton, K. R., Mitchell, M. R., Wing, V. C., Balodis, I. M., Bickel, W. K., Fillmore, M., Lane, S. D., Lejuez, C. W., Littlefield, A. K., Luijten, M., Mathias, C. W., Mitchell, S. H., Napier, T. C., Reynolds, B., Schütz, C. G., Setlow, B., Sher, K. J., Swann, A. C., Tedford, S. E., White, M. J., Winstanley, C. A., Yi, R., Potenza, M. N., & Moeller, F. G. (2015b). Choice impulsivity: Definitions, measurement issues, and clinical implications. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 6(2), 182–198.

Harnett, P. H., Lynch, S. J., Gullo, M. J., Dawe, S., & Loxton, N. (2013). Personality, cognition and hazardous drinking: Support for the 2-component approach to reinforcing substances model. Addictive Behaviors, 38(12), 2945–2948. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.017

Helmond, P., Overbeek, G., Brugman, D., & Gibbs, J. C. (2015). A meta-analysis on cognitive distortions and externalizing problem behavior: Associations, moderators, and treatment effectiveness. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 42(3), 245–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854814552842.

Henwood, K. S., Browne, K. D., & Chou, S. (2018). A randomized controlled trial exploring the effects of brief anger management on community-based offenders in Malta. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 62(3), 785–805. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X16666338

Hogendoorn, S. M., Wolters, L. H., Vervoort, L., Prins, P. J. M., Boer, F., Kooij, E., & de Haan, E. (2010). Measuring negative and positive thoughts in children: An adaptation of the Children’s automatic thoughts scale (CATS). Cognitive Therapy and Research, 34(5), 467–478. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-010-9306-2

Holmbeck, G. N. (1997). Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: Examples from the child-clinical and pediatric psychology literatures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65(4), 599–610. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.65.4.599.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Knyazev, G. G. (2004). Behavioural activation as predictor of substance use: Mediating and moderating role of attitudes and social relationships. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 75(3), 309–321. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.03.007

Leamy, T. E., Connor, J. P., Voisey, J., Young, R. M., & Gullo, M. J. (2016). Alcohol misuse in emerging adulthood: Association of dopamine and serotonin receptor genes with impulsivity-related cognition. Addictive Behaviors 63, 29–36. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.05.008

Lessard, L. M., & Juvonen, J. (2018). Friendless adolescents: Do perceptions of social threat account for their internalizing difficulties and continued friendlessness? Journal of Research on Adolescence, 28(2), 277–283. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12388

Liu, J. (2004). Childhood externalizing behavior: Theory and implications. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 17(3), 93–103. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6171.2004.tb00003.x.

MacKinnon, D. P., Fritz, M. S., Williams, J., & Lockwood, C. M. (2007). Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods, 39(3), 384–389. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193007.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., Hoffman, J. M., West, S. G., & Sheets, V. (2002). A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.83.

Makin-Byrd, K., Bierman, K. L., & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (2013). Individual and family predictors of the perpetration of dating violence and victimization in late adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(4), 536–550. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9810-7

Mauss, I. B., Cook, C. L., Cheng, J. Y. J., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Individual differences in cognitive reappraisal: Experiential and physiological responses to an anger provocation. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 66(2), 116–124. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2007.03.017

Moeller, F. G., Gerard Moeller, F., Barratt, E. S., Dougherty, D. M., Schmitz, J. M., & Swann, A. C. (2001). Psychiatric aspects of impulsivity. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(11), 1783–1793. doi: https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1783

Moffitt, T. E., Arseneault, L., Belsky, D., Dickson, N., Hancox, R. J., Harrington, H., Houts R., Poulton R., Roberts B.W., Ross S., Sears M.R., Thomson W.M. Caspi, A. (2011). A gradient of childhood self-control predicts health, wealth, and public safety. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(7), 2693–2698. doi: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1010076108

O’Leary-Barrett, M., Castellanos-Ryan, N., Pihl, R. O., & Conrod, P. J. (2016). Mechanisms of personality-targeted intervention effects on adolescent alcohol misuse, internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(5), 438–452. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000082.

Papinczak, Z. E., Connor, J. P., Feeney, G. F. X., Harnett, P., Young, R. M., & Gullo, M. J. (2019). Testing the biosocial cognitive model of substance use in cannabis users referred to treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 194, 216–224. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.09.032

Papinczak, Z. E., Connor, J. P., Harnett, P., & Gullo, M. J. (2018). A biosocial cognitive model of cannabis use in emerging adulthood. Addictive Behaviors, 76, 229–235. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.08.011

Patterson, C. M., Mark Patterson, C., & Newman, J. P. (1993). Reflectivity and learning from aversive events: Toward a psychological mechanism for the syndromes of disinhibition. Psychological Review, 100(4), 716–735. : https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-295x.100.4.716

Patton, J. H., Stanford, M. S., & Barratt, E. S. (1995). Factor structure of the barratt impulsiveness scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(6), 768–774. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1.

Patton, K. A., Connor, J. P., Sheffield, J., Wood, A., & Gullo, M. J. (2019). Additive effectiveness of mindfulness meditation to a school-based brief cognitive-behavioral alcohol intervention for adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87(5), 407–421. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000382

Patton, K. A., Gullo, M. J., Connor, J. P., Chan, G. C. K., Kelly, A. B., Catalano, R. F., & Toumbourou, J. W. (2018). Social cognitive mediators of the relationship between impulsivity traits and adolescent alcohol use: Identifying unique targets for prevention. Addictive Behaviors, 84, 79–85. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.03.031

Schniering, C. A., & Rapee, R. M. (2002). Development and validation of a measure of children’s automatic thoughts: The children's automatic thoughts scale. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(9), 1091–1109. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00022-0.

Sloan, R. P., Shapiro, P. A., Gorenstein, E. E., Tager, F. A., Monk, C. E., McKinley, P. S., et al. (2010). Cardiac autonomic control and treatment of hostility: A randomized controlled trial. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72(1), 1–8.

Stautz, K., Dinc, L., & Cooper, A. J. (2017). Combining trait models of impulsivity to improve explanation of substance use behaviour. European Journal of Personality, 31(1), 118–132. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2091.

Steinberg, L., Sharp, C., Stanford, M. S., & Tharp, A. T. (2013). New tricks for an old measure: The development of the Barratt impulsiveness scale-brief (BIS-brief). Psychological Assessment, 25(1), 216–226. doi: https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030550

Sukhodolsky, D. G., Kassinove, H., & Gorman, B. S. (2004). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anger in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 9(3), 247–269.

Thompson, S. F., Zalewski, M., & Lengua, L. J. (2014). Appraisal and coping styles account for the effects of temperament on preadolescent adjustment. Australian Journal of Psychology, 66(2), 122–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12048.

Torrubia, R., Ávila, C., Moltó, J., & Caseras, X. (2001). The sensitivity to punishment and sensitivity to reward questionnaire (SPSRQ) as a measure of Gray’s anxiety and impulsivity dimensions. Personality and Individual Differences, 31(6), 837–862. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0191-8869(00)00183-5.

van Goozen, S. H. M. (2015). The role of early emotion impairments in the development of persistent antisocial behavior. Child Development Perspectives, 9(4), 206–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12134.

Whiteside, S. P., & Lynam, D. R. (2001). The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 669–689.

Zadeh, Z. Y., Im-Bolter, N., & Cohen, N. J. (2007). Social cognition and externalizing psychopathology: an investigation of the mediating role of language. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35(2), 141–152.

Acknowledgements

Matthew J. Gullo was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia Early Career Fellowship (1036365) and a Medical Research Future Fund Translating Research into Practice (TRIP) Fellowship (1167986). Jason P. Connor was supported by a NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (1031909). Kiri A. Patton was supported by a Research Training Program stipend.

Funding

Matthew J. Gullo was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) of Australia Early Career Fellowship (1036365) and a Medical Research Future Fund Translating Research into Practice (TRIP) Fellowship (1167986). Jason P. Connor was supported by a NHMRC Career Development Fellowship (1031909). Kiri A. Patton was supported by a Research Training Program stipend. The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. This study was funded by X (grant number X).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Ethical clearance was granted by the University of Queensland Behavioural and Social Sciences Ethical Review Committee (No. 2015000875), the Brisbane Catholic Education (No. 196). The trial was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12616000077460). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research ethics committee (BSSERC #2015000875) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was first obtained from participants’ parents or guardians before obtaining written assent from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Revill, A.S., Patton, K.A., Connor, J.P. et al. From Impulse to Action? Cognitive Mechanisms of Impulsivity-Related Risk for Externalizing Behavior. J Abnorm Child Psychol 48, 1023–1034 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-020-00642-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-020-00642-7