Abstract

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among adolescents, and impulsivity has emerged as a promising marker of risk. The present study tested whether distinct domains of impulsivity are differentially associated with suicide ideation, plans, and attempts. Adolescents (n = 381; boys = 106, girls = 275) aged 13–19 years (M = 15.62, SD = 1.41) were recruited from an acute, residential treatment program. Within 48 h of admission to the hospital, participants were administered structured clinical interviews assessing mental health disorders and suicidality. Following these interviews, participants completed self-report questionnaires assessing symptom severity and impulsivity. Consistent with past research, an exploratory factor analysis of our 90-item impulsivity instrument resulted in a three-factor solution: Pervasive Influence of Feelings, Feelings Trigger Action, and Lack of Follow-Through. Concurrent analysis of these factors confirmed hypotheses of unique associations with suicide ideation and attempts in the past month. Specifically, whereas Pervasive Influence of Feelings (i.e., tendency for emotions to shape thoughts about the self and the future) is uniquely associated with greater suicidal ideation, Feelings Trigger Action (i.e., impulsive behavioral reactivity to emotions) is uniquely associated with the occurrence of suicide attempts, even after controlling for current psychiatric diagnoses and symptoms. Exploratory gender analyses revealed that these effects were significant in female but not male adolescents. These findings provide new insight about how specific domains of impulsivity differentially increase risk for suicide ideation and attempts. Implications for early identification and prevention of youth suicide are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Suicide rates have increased dramatically over recent decades, and presently, suicide is among the leading causes of death worldwide (Nock et al. 2008). Mental disorders are one of the strongest risk factors for attempted and completed suicide (Nock et al. 2010), and approximately 90 % of individuals who die by suicide have a diagnosable psychiatric disorder (Harris and Barraclough 1997; Pokorny 1983). Nonetheless, the majority of psychiatric patients do not suicide, and thus, there are likely other proximal factors that increase suicide risk (Mann et al. 1999).

Among adolescents, suicide is the second leading cause of death (CDC 2013), and the psychobiological processes that underlie suicidality are not well understood. Indeed, suicide ideation is relatively common, but very few adolescents make attempts (Nock et al. 2013). Recent cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have linked suicide attempts with both self-reported (Brezo et al. 2006) and performance-based (Jollant et al. 2005; Swann et al. 2005) impulsivity, and these associations have been confirmed in adolescent samples (e.g., (Dougherty et al. 2009; McKeown et al. 1998; Stewart et al. 2015). Although impulsivity has emerged as a core construct across theories of suicidality (Anestis et al. 2014; Gvion and Apter 2011; Joiner et al. 2005; Mann et al. 1999), the precise relationship between impulsivity and suicidal behaviors remains unclear. In part, impulsivity is a broad construct comprised of separable dimensions (Dick et al. 2010; Sharma et al. 2014), but studies often test single, unitary domains of impulsivity. Consequently, it is not known which domain of impulsivity is specifically linked to suicidality. Further, it may be that dimensions of impulsivity are differentially related to suicide-related outcomes (e.g., suicide ideation vs. plans, vs. attempts). A better understanding of these specific relationships may help guide clinicians in providing more targeted clinical care for at-risk youth (e.g., continuing outpatient treatment versus hospitalizing). To address this empirical and theoretical gap, the present study tests whether distinct domains of impulsivity are associated with specific types of adolescent suicidality.

Developmental Perspective

Adolescence is a period marked by significant psychosocial and neurobiological changes. From a psychosocial perspective, youth become more autonomous from parents and socially reliant on peers, and this transition often gives rise to greater interpersonal stress and emotional reactivity (Casey et al. 2008; Rudolph 2008). With respect to neurodevelopmental processes, several theories of adolescent behavior suggest that discordant development of prefrontal and limbic circuitry contribute to adolescent risk-taking and impulsivity (see Ernst et al. 2006; Forbes and Dahl 2005). Specifically, the largely intact limbic system is believed to drive reward-seeking and goal-directed behavior, and unfortunately, the under-developed prefrontal systems may not be equipped to inhibit and control impulses (Casey et al. 2008). Moreover, researchers posit that this discordant neural development contributes, in part, to a range of negative, impulsive outcomes in adolescents, including motor vehicle crashes, unintentional injuries, homicide, and suicide (Casey et al. 2008; Eaton et al. 2006).

Emotion-Relevant Impulsivity and Suicidality

Impulsivity has been extensively studied, particularly as it relates to risky behavior engagement (Auerbach and Gardiner 2012; Lejuez et al. 2010), personality dimensions (Berg et al. 2015), psychopathology (Cyders and Coskunpinar 2011), and suicide (Stewart et al. 2015; Swann et al. 2005). Recent developments suggest that emotion-relevant impulsivity, particularly negative urgency (i.e., a strong and immediate need to avoid undesirable emotions or physical sensations) is distinct from other forms of impulsivity and may be associated with suicide attempts (see Lynam et al. 2011). Emotion-relevant impulsivity – poor control over reactions following emotions – is a strong predictor of problem behaviors generally and suicidality specifically. Across 115 studies (n = 40,432), compared to other forms of impulsivity, emotion-relevant impulsivity is related to a wide array of psychological and behavioral processes, including violence, vandalism, risky sexual behaviors, compulsive spending, gambling, and substance use (see meta-analysis Berg et al. 2015). In addition, it correlates with syndromes (and associated symptoms) directly related to suicide risk. These include, but are not limited to, depressive symptoms (d’Acremont and Van der Linden 2007), borderline personality disorder symptoms and diagnosis (Glenn and Klonsky 2010; Whiteside and Lynam 2001; Whiteside et al. 2005), impulse-control disorders (Nock et al. 2009), and nonsuicidal self-injury (Black and Mildred 2014; Glenn and Klonsky 2010; Peterson et al. 2014; Rawlings et al. 2015). Further, in a multi-year follow-up study of patients with depression or personality disorders, impulsive responses to emotions predicted a faster time to suicide attempts (Yen et al. 2009). As a whole, these results indicate that emotion-relevant impulsivity is implicated in a range of outcomes related to suicidality.

Although emotion-relevant impulsivity includes several related domains, negative urgency is a particularly significant risk factor for suicidal behaviors (Berg et al. 2015). In a recent meta-analysis, negative urgency was significantly related to a composite of suicidality and nonsuicidal self-injury; the effect size for negative urgency was larger than those reported for other forms of impulsivity (Berg et al. 2015). In specific studies, urgency also is directly correlated with a general measure of suicidality (Dvorak et al. 2013) and is cross-sectionally related to suicide attempts among inpatients with substance use disorders (Lynam et al. 2011).

Research also has compared the effects of emotion- and non-emotion relevant impulsivity on suicidality among adults. Interestingly, negative urgency, but not lack of premeditation or perseverance (i.e., non-emotion relevant impulsivity domains, which reflect planning and follow through, respectively), is significantly related to past suicide attempts (Anestis et al. 2014), and both negative urgency and lack of perseverance were positively correlated with suicidal ideation and future suicidality (i.e., endorsing the likelihood of dying in a future suicide attempt) (Lynam et al. 2011). Conversely, when researchers controlled for the presence of suicidal ideation, somewhat different findings emerge (Klonsky and May 2010). In a large sample of military recruits (n = 2011), college students (n = 1296), and high school students (n = 399), negative urgency distinguishes suicide ideators from those with no history of suicidality while non-emotion-relevant impulsivity (i.e., lack of premeditation) was related to suicide attempts. Taken together, research to date suggests that the relationship between emotion-relevant impulsivity and suicidality warrants clarification, particularly as it may inform specific forms of suicidality (suicide ideation vs. plans vs. attempts).

Although this literature highlights the importance of emotion-relevant impulsivity to suicidality, recent work has expanded its conceptualization and measurement. Carver and colleagues (Carver, Johnson, Joormann, Kim, and Nam 2011) created a questionnaire to capture impulsive responses to both positive and negative emotions as well as impulsivity outside the context of emotion. Factor analyses yielded three distinct dimensions: Pervasive Influence of Feelings, Feelings Trigger Action, and Lack of Follow-Through (Carver et al. 2011; Johnson et al. 2013). Pervasive Influence of Feelings captures a tendency for (mostly negative) emotions to shape thoughts about the self and the future. Feelings Trigger Action refers to the tendency to say and do things that are later regretted during a heightened emotional state. In contrast to these two dimensions of emotion-relevant impulsivity, Lack of Follow-Through (i.e., a non-emotion relevant domain) reflects a tendency to have difficulty concentrating and following through with goals. Research has shown that emotion-related impulsivity does not merely reflect a tendency toward greater emotionality (Cyders and Smith 2008), and also shows divergent validity with constructs such as distress tolerance (Anestis et al. 2007). In a sample of 136 undergraduates, Pervasive Influence of Feelings and Feelings Trigger Action were both associated with greater severity of suicidality (ranging from suicidal ideation with no plan or intent to hospitalization for suicidal behavior). Further, Pervasive Influence of Feelings was associated with suicidality while controlling for the other two impulsivity dimensions (Johnson et al. 2013). However, in light of low base-rates of suicidal behaviors (i.e., 17 participants endorsed suicidal thoughts, 1 endorsed suicide attempts), the study was unable to test whether different impulsivity factors were related to specific suicidal processes.

Goals of the Current Study

In the current study, we draw on recent developments in the understanding of emotion-relevant impulsivity to test whether distinct domains are differentially associated with adolescent suicide ideation, plans, and attempts. Extending previous research (Carver et al. 2011; Johnson et al. 2013), we tested our model in a sample of adolescent psychiatric inpatients assessed within 48 h of admission to an acute psychiatric treatment facility. Importantly, psychiatric adolescent inpatients are at greatest risk for suicide (Auerbach et al. 2015; Stewart et al. 2015), and they represent a vastly understudied population (van Alphen et al. 2016). Before testing hypotheses, we conducted an exploratory factor analysis of the emotion- and non-emotion-relevant impulsivity subscales to determine whether the structure was consistent with past research in young adults (see Carver et al. 2011; Johnson et al. 2013). Importantly, when examining a priori hypotheses, we used a conservative approach. All models concurrently tested each impulsivity domain while controlling for current symptom severity as well as clinical diagnoses that were associated with the outcome. Such an approach allowed us to detect unique associations of each facet of impulsivity with different types of suicidality. First, we hypothesized that Pervasive Influence of Feelings, which largely captures tendencies for emotion states to shape thinking, would have a unique association with suicidal ideation. In part, this domain has strong links with negative affectivity and related cognitive factors (e.g., hopelessness) and past research has shown a robust association with suicidal ideation (Stewart et al. 2005). Second, we hypothesized that Feelings Trigger Action – impulsive behavioral reactivity to emotions – would be the only factor associated with the occurrence and frequency of suicide attempts, after controlling for current symptoms, suicidal ideation, and suicide plans. In previous research, negative urgency, one of the subscales that comprise Feelings Trigger Action, has been shown to predict suicide attempts among inpatients (Lynam et al. 2011). Third, there are mixed findings regarding the relationship between non-emotion relevant impulsivity and suicidality (Klonsky and May 2010; Lynam et al. 2011). Consequently, we conducted exploratory analyses to examine the relationship between Lack of Follow Through and each suicidality domain (i.e., ideation, plans, and attempts). Last, exploratory gender analyses tested gender differences. Presently, adolescent boys are more likely to die by suicide, but girls report higher rates of suicidal ideation and attempts (Beautrais 2003; Lewinsohn et al. 2001; Witte et al. 2008). It is unclear whether different impulsivity domains differentially influence suicidal behaviors among boys and girls. Thus, exploratory gender differences were tested with each impulsivity domain and suicide outcome.

Method

Participants

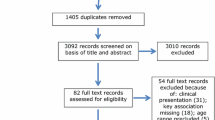

Participants were 381 adolescents (106 male, 275 female) recruited from an acute adolescent residential treatment program. Ages ranged from 13 to 19 years old (M = 15.62, SD = 1.41) and their racial/ethnic distribution included: 81.6 % White, 10.5 % multicultural (i.e., more than one race endorsed) 3.7 % Asian, 1.6 % Black, and 1.0 % Native American. All participants completed the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for children and adolescents (MINI-KID; Sheehan et al. 2010) to assess current and past psychopathology. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in this sample is summarized in Table 2. The most common class of diagnosis was unipolar mood disorders (i.e., major depression or dysthymia; n = 314, 82.4 %), followed by anxiety disorders (i.e., panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder [GAD], social anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder [PTSD], specific phobia, and separation anxiety disorder; n = 255, 66.9 %). Rates of substance use, alcohol use, and behavioral (i.e., conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder) disorders were relatively low, and high rates of diagnostic comorbidity typified many participants. Twenty-five (6.6 %) adolescents did not receive a diagnosis, 89 (23.4 %) had a single diagnosis, 92 (24.1 %) had 2 diagnoses, and nearly half (45.9 %) met criteria for at least 3 diagnoses.

Our initial sample included 415 adolescents. Twenty-three participants (5.5 %) were excluded due to missing data on our measure of facets of impulsiveness. An additional 11 adolescents (2.7 %) failed more than 50 % of the catch items embedded in our impulsiveness questionnaire, indicating invalid responding on this measure. These participants were removed, leaving a total of 381 participants included in primary analyses.

Procedure

The Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures, which were embedded within a quality assurance program wherein all adolescent patients admitted to the child and adolescent program receive clinical assessments. Prior to participation, legal guardians and adolescents 18 years old and older provided written consent and youth aged 18 years or younger provided assent. Graduate students and BA-level research assistants not affiliated with clinical care administered all assessments. Initially, adolescents were administered clinical interviews assessing current and past psychopathology as well as history of suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Then, adolescents filled out a series of self-report instruments measuring impulsivity and symptoms of suicidal ideation, depression, and anxiety.

Instruments

Assessment of Psychopathology and Suicidality

Diagnosticians received approximately 25 h of training including didactics, role-play, mock interviews, and supervised interviews, and additionally, there were regular recalibration meetings to confirm clinical designations. Trained bachelor’s-level research assistants or graduate students completed all interviews. The MINI-KID (Sheehan et al. 2010) is a structured diagnostic interview designed to assess current and past psychopathology for children and adolescents using DSM-IV criteria. The MINI-KID possesses strong psychometric properties for diagnosing psychopathology among inpatient youth (Auerbach et al. 2014; Auerbach et al. 2015). The Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview (SITBI; Nock et al. 2007) is a structured clinical interview assessing the presence, frequency, and severity of suicidal thoughts and behaviors that has been validated for use with adolescent inpatients (Venta and Sharp 2014). Outcomes were operationalized as the number of days in the past month in which participants experienced suicidal ideation (i.e., “had thoughts of killing yourself”) and made a suicide plan (i.e., “made a plan to kill yourself”). In addition, the interview probed the presence or absence of a suicide attempt in the past month (i.e., “Have you ever made an actual attempt to kill yourself in which you had at least some intent to die?”) as well as the frequency of suicide attempts in the same time frame. For suicide attempts in the past month, the interview probed both method and lethality. Finally, the interview also assessed lifetime suicide ideation, plans, and attempts.

Depression Symptoms

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff 1977) is a 20-item self-report instrument designed to assess depression symptom severity in the previous week. Items are rated on a scale from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time), and scores range from 0 to 60, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms. Exemplar items include, “I had trouble keeping my mind on what I was doing” and “I felt I could not shake off the blues even with the help from my friends and family,” The internal consistency was excellent (Cronbach’s α = 0.94).

Anxiety Symptoms

The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (March et al. 1997) is a 39-item self-report inventory designed to measure anxiety symptoms across four domains: physical symptoms, harm avoidance, social anxiety, and separation anxiety/panic. Possible responses range from 0 (Never true about me) to 3 (Often true about me) with total scores ranging from 0 to 117, and higher scores indicate more severe anxiety. Internal consistency was excellent (Cronbach’s α = 0.92).

Impulsivity

Impulsivity was assessed using an established 90-item self-report instrument probing ten domains: (1) negative generalization (4 items; α = 0.86), (2) urgency (12 items; α = 0.90), (3) lack of perseverance (9 items; α = 0.85), lack of self-control (14 items; α = 0.83), (5) laziness (19 items; α = 0.90), (6) sadness paralysis (2 items; α = 0.85), (7) inability to overcome lethargy (7 items; α = 0.91), (8) emotions color worldview (3 items; α = 0.73), distractibility (9 items; α = 0.92), and reflexive reactions to feelings (7 items; α = 0.87). In our sample, the 10 domains of impulsivity were all significantly inter-correlated (rs = 0.16–0.70, all ps < 0.003). Previous research using this instrument indicates that these subscales load onto three primary factors: (a) Pervasive Influence of Feelings, (b) Lack of Follow-Through, (c) Feelings Trigger ActionFootnote 1 (Carver et al. 2011; Johnson et al. 2013). The subscales have been validated against measures of genetic risk and early adversity and have been found to relate to a broad range of psychopathology, including major depressive disorder and suicidality (Carver et al. 2011; Johnson et al. 2013). Responses ranged from 1 (I agree a lot/never) to 5 (I disagree a lot/very often), and higher scores indicated greater impulsivity.

Catch Items

Four catch items were embedded within the questionnaire (e.g., “Choose 4 as your response to this item”) as a way to capture random responding. Participants who answered three or more of these items incorrectly were excluded from analyses.

Data Analytic Overview

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.0. First, we conducted an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) to determine the factor structure of the 10 scales measuring impulsive reactivity versus self-control. An EFA approach was used as no previous research had tested an adolescent sample, which has important developmental differences relative to older populations (i.e., college students, adults). Further, no research had explored the factor structure in an acute clinical population. Consistent with previous research in older samples (Carver et al. 2011; Johnson et al. 2013), each scale was treated as a single item in these analyses. We adopted an exploratory approach because the factor structure of these scales had not been examined in a clinical sample of adolescents. Following the approach suggested by Fabrigar et al. (1999), we conducted a series of factor runs using Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) with a Direct Oblimin rotation (delta = 0) to determine the number and nature of factors, assuming moderate inter-correlation among factors. To choose the appropriate structure, we inspected the scree plot, conducted a Horn’s parallel analysis, considered the relative fit of factor solutions using Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA) values, evaluated the pattern of loadings, and considered the interpretability of each solution and its fit with existing theory. Next, we used the Bartlett approach to compute factor scores derived from the pattern of loadings in the final factor solution. We chose this method because we wanted unbiased and valid (i.e., scores highly correlated with the estimated factor) estimates of the latent factors while allowing them to be correlated (DiStefano et al. 2009).

In preliminary model building, we ran a series of univariate Poisson regression models to identify demographic and clinical variables significantly associated with suicidality outcomes (i.e., past month ideation, plans, and attempts). Specifically, we tested the effects of age, gender, and ethnicity, as well as the presence/absence of particular psychiatric diagnoses, the number of diagnoses endorsed, and internalizing symptom severity (i.e., depression, anxiety). For all Poisson models, we obtained robust standard errors for the parameter estimates to control for over-dispersion (i.e., variance > mean) in our data, consistent with current recommendations (e.g., Cameron and Trivedi 2009).

In our primary analyses, we specified 3 multivariate Poisson regression models (Dependent Variable [DV]: past month suicide ideation, plans and attempts) and one multivariate hierarchical logistic regression model (DV: presence/absence of at least one past month attempt). These models included any demographic or clinical variable that was significantly associated with the outcome variable in our univariate analyses, as well as the factor score variables corresponding to each impulsivity domain. Since we conducted 4 primary models, we used a Bonferroni correction to adjust for the inflated family-wise error rate, and our critical alpha was set to p < 0.013.

When we found an effect of one or more impulsivity domains on adolescent suicidality, we conducted two follow-up analyses. First, for the suicide plans and attempts models, we re-ran our analysis controlling for suicide ideation and suicide ideation and planning, respectively. We did this to more stringently test whether our variables were significantly associated with suicide plans and attempts, over and above their relations with other types of suicidality. Second, we re-ran analyses stratifying the sample by gender to test whether our effects were different among girls versus boys.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

In our sample, 209 (55.9 %) and 162 (43.1 %) adolescents reported at least some past month suicide ideation and planning, respectively. On average, adolescents reported ideating 5.19 days (SD = 12.95) and making suicide plans on 2.45 days (SD = 5.32) in the month prior to the assessment. A total of 76 (20.3 %) adolescents reported a suicide attempt in the past month; among these adolescents 11 (14.5 %) reported more than one attempt. All three indices of suicidality were significantly associated: (a) suicide ideation and plans, b = 0.10, SE = 0.01, χ 2(1, N = 372) = 169.91, p = <0.001, OR = 1.10, CI95 (1.09, 1.12); (b) suicide ideation and attempts, b = 0.03, SE = 0.01, χ 2(1, N = 370) = 5.43, p = 0.020, OR = 1.03, CI95 (1.01, 1.06); (c) plans and attempts, b = 0.06, SE = 0.01, χ 2(1, N = 370) = 20.84, p = <0.001, OR = 1.06, CI95 (1.04, 1.09). The majority of adolescents reported lifetime suicidal ideation (n = 330, 86.6 %), and more than half (n = 222, 58.4 %) reported making at least one lifetime suicide plan. Further, just over one-third of the sample (n = 142, 37.8 %) reported at least one lifetime suicide attempt.

Among adolescents who reported at least one suicide attempt in the past month (n = 76), the following methods were reported: overdose (using prescription medications, over-the-counter medications, or illegal drugs) (n = 66; 86.8 %), sharp object (n = 11; 14.5 %), hanging (n = 7; 9.2 %), suffocation (n = 4; 5.3 %), jumping in front of a vehicle (n = 4, 5.3 %), ingesting poison (n = 4, 5.3 %), jumping from a height (n = 1, 1.3 %) and inhaling poisonous gas (n = 1, 1.3 %).Footnote 2 Among adolescents who had made an attempt in the past month (n = 76), 58 (76.3 %) reported that their most recent attempt was their most lethal.

Exploratory Factor Analysis

In our initial run, the factor identification rule was set to Eigenvalues greater than 1. Three factors were extracted in this run and these accounted for 65.83 % of the variance in the items. A visual inspection of the scree plot suggested that 4 factors was an appropriate possible upper limit, but that the best solution might be 2 or 3 factors. The parallel analysis indicated that Eigenvalues computed from the reduced correlation matrix from the actual data were equivalent to Eigenvalues generated from completely random data (n = 100) beginning at the 4-factor solution. Thus, we next specified 1-, 2-, 3-, and 4-factor solutions in a series of runs to compute RMSEA from chi-square values using FITMOD (Browne 1991) to assess the relative fit of these solutions. Ultimately, the final 3-factor solution was deemed to be the best combination of parsimony, relative fit, RMSEA = 0.06, CI95(0.03, 0.09) and ease of interpretation and is similar to the structure reported by Carver et al. (2011). Both the 1-factor, RMSEA = 0.208, CI95(0.19, 0.23) and 2-factor, RMSEA = 0.17, CI95(0.15, 0.19) solutions had unacceptable fits with our data. Further, although the 4-factor solution was a closer fit than the 3-factor, RMSEA = 0.000, CI95(0.00, 0.05) results, this solution had one factor with only a single high loading, and thus, did not represent a major common factor.

Once we had determined that the 3-factor solution was most appropriate, we computed our final structure using Principal Axis Factoring with a Direct Oblimin rotation (delta = 0). This was done to enhance the interpretability of the factor scores we compute below. This final 3-factor solution accounted for 65.88 % of the variance in the items and the pattern matrix of factor loadings is presented in Table 1. The three factors were labeled consistent with previous studies (Carver et al. 2011). Factor 1, Lack of Follow-Through, reflects a tendency to leave tasks incomplete. Factor 2, Feelings Trigger Action, is characterized by items measuring individuals’ degree of impulsive behavioral reactivity to their emotions. Factor 3, Pervasive Influence of Feelings, captures an individual’s tendency to allow emotions to impact their perception and orientation to the world (e.g., worldview affected temporarily be feelings; generalizing negative events to define self-worth). Factor scores were computed for each participant and as hypothesized, our factor scores were moderately and significantly associated (rs = 0.27–0.45, all ps < 0.001). There were no gender differences for Lack of Follow-Though, t(379) = −0.42, p = 0.68, d = 0.04, or Pervasive Influence of Feelings, t(379) = −1.23, p = 0.22, d = 0.13 . However, compared to boys, girls reported higher scores on Feelings Trigger Actions, t(379) = −2.60, p = 0.01, d = 0.27.

Demographic Correlates of Adolescent Suicidality

We conducted preliminary analyses to examine the effects of gender, age, and ethnicity on suicidality (ideation, plans, and attempts) in the past month. Female (versus male) gender was not significantly associated with the frequency of suicide ideation, b = 0.56, SE = 0.43, χ 2(1, N = 374) = 1.73, p = 0.19, OR = 1.75, CI95 (0.76, 4.05), suicide plans, b = 0.05, SE = 0.28, χ 2(1, N = 376) = 0.04, p = 0.85, OR = 1.05, CI95 (0.61, 1.81), or suicide attempts, b = 0.24, SE = 0.42, χ 2(1, N = 374) = 0.33, p = 0.57, OR = 1.27, CI95 (0.56, 2.91), in the month before the assessment. Younger age was associated with a greater frequency of suicide plans, b = −0.22, SE = 0.07, χ 2(1, N = 376) = 10.61, p = 0.001, OR = 0.81, CI95 (0.71, 0.92), and attempts, b = −0.17, SE = 0.08, χ 2(1, N = 374) = 4.27, p = 0.04, OR = 0.85, CI95 (0.73, 0.99), but not suicidal ideation, b = −0.02, SE = 0.04, χ 2(1, N = 377) = 0.34, p = 0.56, OR = 0.98, CI95 (0.92, 1.05). Finally, there was no effect of ethnicity in predicting ideation, χ 2(4, N = 367) = 2.34, p = 0.67, plans, χ 2(3, N = 365) = 3.04, p = 0.39, or attempts, χ 2(3, N = 364) = 1.09, p = 0.78. Therefore, we included age in analyses predicting past month suicide plans and attempts.

Clinical Correlates of Adolescent Suicidality

Associations among psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses and our measures of suicidality in the past month are summarized in Table 2. Significant diagnostic predictors were included as covariates when testing models regarding the relation between impulsivity and suicidality. Significant univariate predictors of past month suicide ideation frequency included higher internalizing symptoms (depression and anxiety), the presence of a unipolar mood disorder, GAD, Social Phobia, any eating disorder, and any psychotic disorder, and a greater overall number of diagnoses. The pattern of results was nearly identical for suicide plans, although the effect of GAD and psychotic disorders were non-significant. In contrast, univariate predictors of suicide attempts included unipolar mood disorders, PTSD, alcohol use disorders (dependence or abuse), substance use disorders (dependence or abuse), eating disorders and a higher number of diagnoses. The symptom factors demonstrated some specificity in their associations with different forms of suicidality (ideation, plans, and attempts). Whereas Lack of Follow-Through was significantly association with suicidal ideation, but not plans or attempts, Feelings Trigger Action was uniquely associated with attempts, not plans or ideation. Pervasive Influence of Feelings was associated with both ideation and plans, but not attempts.

Suicide Ideation

The results of our Poisson regression model predicting past month suicidal ideation from diagnostic and symptom covariates, as well as our three impulsivity factor scores, are presented in Table 3. Both greater depressive symptom severity and the presence of a unipolar mood disorder were significantly associated with more frequent ideation. Additionally, higher scores on Pervasive Influence of Feelings were associated with greater past month ideation.

In follow-up Poisson regression models stratified by participant gender, the effect of Pervasive Influence of Feelings on suicidal ideation was significant among girls, b = 0.32, SE = 0.08, χ 2(1, N = 272) = 15.83, p < 0.001, OR = 1.38, CI95 (1.18, 1.61), but not boys, b = 0.12, SE = 0.13, χ 2(1, N = 105) = 0.81, p = 0.37, OR = 1.13, CI95 (0.87, 1.45).

Suicide Plans

In our Poisson regression model predicting suicide plans, younger age, the presence of a unipolar mood disorder, and greater depressive symptom severity were all significant predictors of more frequent suicide plans. Additionally, lower scores on Lack of Follow-Through were uniquely associated with more frequent suicide plans (see Table 3). The effect of Lack of Follow-Through on plans was somewhat robust to controlling for the frequency of suicide ideation, but did not meet our conservative critical alpha value, b = −0.22, SE = 0.10, χ 2(1, N = 371) = 4.72, p = 0.03, OR = 0.80, CI95 (0.69, 0.93). Our follow-up gender analyses revealed that the effect of Lack of Follow-Through was non-significant among both girls, b = −0.17, SE = 0.11, χ 2(1, N = 271) = 2.22, p = 0.14, OR = 0.84, CI95 (0.67, 1.06), and boys, b = −0.41, SE = 0.23, χ 2(1, N = 105) = 3.30, p = 0.07, OR = 0.67, CI95 (0.43, 1.03).

Suicide Attempts

In the Poisson regression model predicting suicide attempt frequency, younger age, the presence of PTSD, the presence of any alcohol use disorder and the presence of any substance use disorder were all significantly associated with past month attempts. However, none of the impulsivity factor scores were significant predictors in this model (see Table 3).

In the logistic regression model predicting the presence versus absence of at least one past month attempt, Step 1 including age and the clinical covariates (the presence/absence of psychopathology; number of disorders) was significant (see Table 4). However, there were no significant unique predictors of past month attempts on this step using our corrected alpha value. The addition of the 3 factor score variables was significant in Step 2, and Feelings Trigger Action, but not the other factor score variables, was significantly associated with greater odds of having made a suicide attempt in the past month. No other predictor was significantly associated with suicide attempts on Step 2. When we re-ran our model adding past month ideation and plans as additional covariates, the unique effect of Feelings Trigger Action remained statistically significant, b = 0.46, SE = 0.15, χ 2(1, N = 366) = 9.04, p = 0.003, OR = 1.58, CI95 (1.17, 2.12).

Our follow-up gender analyses revealed that Feelings Trigger Action scores were associated with greater odds of a past month attempt among girls, b = 0.56, SE = 0.17, χ 2(1, N = 270) = 10.27, p = 0.001, OR = 1.75, CI95 (1.24, 2.46), but not among boys, b = 0.07, SE = 0.31, χ 2(1, N = 104) = 0.05, p = 0.83, OR = 1.07, CI95 (0.58, 1.97).

Discussion

Suicide rates are increasing among adolescents (Nock et al. 2013), and presently, there are no definitive predictors of suicidality. Given this pressing public health concern, research is needed to identify factors that confer suicide risk. The present study involved a comprehensive assessment of impulsivity and related constructs, used empirical data reduction techniques to identify theoretically-meaningful domains, tested differential relationships among these domains of impulsivity and specific types of suicidality, and explored potential gender differences. Results indicated that Pervasive Influence of Feelings was associated with suicidal ideation, and only Feelings Trigger Action was related to the occurrence of suicide attempts in the past month (OR = 1.60). These effects, however, only were significant in girls but not boys. As a whole, these findings offer new insights about how impulsivity may be associated with specific types of suicidality.

An Empirical Approach to Impulsivity

To our knowledge, this is the first study to empirically derive separable dimensions of impulsivity and then, examine differential associations with suicide outcomes (i.e., suicide ideation vs. plans vs. attempts) in a psychiatric adolescent sample. Results from our exploratory factor analysis were in line with the factor structure for the impulsivity scale found in young adults (Carver et al. 2011; Johnson et al. 2013). Consistent with previous research, we found that 10 distinct impulsivity subscales clustered into emotion-relevant (Pervasive Influence of Feelings, Feelings Trigger Action) and non-emotion-relevant (Lack of Follow Through) domains, which provides evidence for the stability of these separable dimensions across age and psychiatric characteristics (i.e., college students vs. adolescent psychiatric patients).

Impulsivity and Suicidality

A central aim of the current study was to test whether domains of impulsivity were uniquely associated with different suicide outcomes. The conservative data analytic approach tested models that included all domains of impulsivity and current psychiatric diagnoses and symptoms. Only Pervasive Influence of Feelings was uniquely associated with suicidal ideation whereas Feelings Trigger Action was exclusively linked to the occurrence of suicide attempts in the past month (but did not predict the frequency of suicide attempts in the past month). Although the effect sizes for these results were small, they highlight the importance of developing a more precise operational definition of constructs when examining differential relationships among impulsivity domains and suicide-specific processes. That is, tendencies toward impulsive thoughts were related to ideation, whereas tendencies toward impulsive actions were related to suicidal action.

Among the most challenging decisions a clinicians need to make is whether adolescent patients are an imminent threat to hurt themselves. Although impulsivity has emerged as a predictor of suicidal ideation (Hull-Blanks et al. 2004) and attempts (Dougherty et al. 2004, 2009), research has not consistently demonstrated that suicide attempters are more impulsive than non-attempters (Anestis et al. 2014). This may reflect the failure to consider emotion-relevant impulsivity domains; the current research suggests that Feelings Trigger Action may help predict suicidal action. A natural next step would be to conduct prospective research to assess whether Feelings Trigger Action prospectively predicts suicide attempts, and with longitudinal data, test whether different thresholds (i.e., greater severity) are inversely associated with time to attempt. These important questions cannot be resolved by the current findings, but they do put in motion a chain of important follow-up research that may provide insights into specific processes that contribute to suicide ideation versus attempts. Another critical research question is whether the current findings extend to adult populations. As noted earlier, there are key developmental differences in adolescents relative to adults, including a greater frequency of interpersonal stressors (Rudolph 2008), discordant frontolimbic development (Casey et al. 2008), and an increased occurrence of impulsive outcomes (e.g., vehicular crashes, unintentional injury) (Eaton et al. 2006). Given the stability of impulsivity over time (e.g., Niv et al. 2012), there is reason to believe that the current findings are invariant across ages. At the same time, this should be tested in future research.

Research to date has not identified impulsivity as a strong correlate of suicide planning (Anestis et al. 2014). Exploratory analyses revealed that reduced Lack of Follow Through, a non-emotion-relevant form of impulsivity, was associated with higher suicide plan frequency. However, after controlling for suicidal ideation, this effect was no longer significant. On the whole, Lack of Follow Through did not appear to relate to suicidality after controlling for symptoms and other forms of impulsivity.

Examining Gender Differences in Impulsivity and Suicidal Behaviors

Although boys are more likely to die by suicide, adolescent girls report higher rates of suicidal ideation and attempts (Beautrais 2003; Lewinsohn et al. 2001; Witte et al. 2008). In the current sample, there were no gender differences with respect to suicide ideation, plans, and attempts, however, interestingly, our exploratory results suggest that for girls, but not boys, Pervasive Influence of Feelings is associated with suicidal ideation and Feelings Trigger Actions is associated with suicide attempts. Notably, there are no gender differences in Pervasive Influence of Feeling, which suggests that given comparable impulsivity (within this domain), adolescent girls may be particularly susceptible to experiencing suicidal ideation. By contrast, girls report higher scores on Feelings Trigger Action. At first blush this may be surprising, but research has not consistently demonstrated gender differences in impulsivity (e.g., Cyders 2013; Reynolds et al. 2006; Stoltenberg et al. 2008). Among girls in our sample, Feelings Trigger Action was associated with a greater likelihood of making a suicide attempt in the month prior to hospitalization. From a clinical perspective, this may be an especially promising clinical target for high-risk adolescent girls.

Limitations

There are several limitations in the current study, which may be addressed in future research. First, the study relied on a self-report measure of impulsivity. Given past limitations in impulsivity research (see Berg et al. 2015), this approach is critical to identify the core factor structure of this multifaceted construct. At the same time, self-report measures are prone to response bias and shared method variance, and therefore, future research would benefit from using objective measures of impulsivity (e.g., performance-based experimental tasks). Additionally, it is important to note that the time frame of certain measures does not overlap. For example, the assessment of depressive symptoms reflects the past 2 weeks whereas suicidality indexes the past month. These discrepancies may impact findings. Second, the study is cross-sectional, and prospective research is warranted to identify whether impulsivity domains predict suicidal thoughts and behaviors. Third, a strength of the study was testing unique associations with impulsivity domains and suicidality, however, future research also would benefit from examining whether interactions among specific impulsivity domains confers prospective vulnerability to suicidality. Moreover, recent research has begun to compare differences (e.g., anhedonia, reward processing) among adolescent suicide ideators and suicide attempters (e.g., Auerbach et al. 2015). Future research would benefit from determining whether domains of impulsivity differentiate ideators and attempters, particularly among groups with comparable levels of symptom severity and suicide ideation to ensure that any differences that arise can be attributed to impulsivity specifically. Fourth, although the study provides insight into processes that occur within the past month, our current approach cannot delineate the time-lagged relationship among suicide ideation, plans, and attempts. This is an important empirical question, as it may provide key insight into the mechanisms that facilitate the transition from thinking about suicide to attempting suicide. One way to address this question would be to use timeline follow-back methodology, which has been used to gather retrospective information during a specified period prior to a suicide attempt (Bagge et al. 2013). Fifth, the study did not assess whether emotion regulation or distress tolerance deficits contributed to adolescent suicidality. Future research would benefit from clarifying whether these factors interact with impulsivity to increase prospective risk. Last, the study assessed psychiatric adolescent inpatients, which was critical for providing a thorough test of our hypotheses given the higher rates of suicidal ideation, plans, and attempts in this population. Future research is needed to determine the generalizability of findings to community samples.

Clinical Implications

Suicide in adolescents is a major public health concern, and identifying risk factors is essential. Our findings suggest that different domains (i.e., Pervasive Influence of Feelings vs. Feelings Trigger Action) of impulsivity may, ultimately, lead to different types of suicide outcomes (i.e., ideation vs. attempts). Clinical interventions may benefit from better operationalizing patients’ impulsivity, as this may inform the clinical strategies targeted during treatment of at-risk patients. Ultimately, this more personalized approach to treatment may optimize outcomes and help maintain the safety of high-risk youth.

Notes

The impulsivity measure includes both a negative and a positive urgency subscale (i.e., tendency to act recklessly or inappropriately during positive mood states). The 7-item positive urgency subscale was inadvertently omitted from the assessment. Nonetheless, the factor structure and interrelationships among the factors remained consistent with past research (see Carver et al. 2011; Johnson et al. 2013).

When reporting the method of suicide attempts, some participants reported using multiple methods in their most recent attempt.

References

Anestis, M. D., Selby, E. A., Fink, E. L., & Joiner, T. E. (2007). The multifaceted role of distress tolerance in dysregulated eating behaviors. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40, 718–726.

Anestis, M. D., Soberay, K. A., Gutierrez, P. M., Hernandez, T. D., & Joiner, T. E. (2014). Reconsidering the link between impulsivity and suicidal behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18, 366–386.

Auerbach, R. P., & Gardiner, C. K. (2012). Moving beyond the trait conceptualization of self-esteem: the prospective effect of impulsiveness, coping, and risky behavior engagement. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50, 596–603.

Auerbach, R. P., Kim, J. C., Chango, J. M., Spiro, W. J., Cha, C., Gold, J., & Nock, M. K. (2014). Adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: examining the role of child abuse, comorbidity, and disinhibition. Psychiatry Research, 220, 579–584.

Auerbach, R. P., Millner, A. J., Stewart, J. G., & Esposito, E. C. (2015). Identifying differences between depressed adolescent suicide ideators and attempters. Journal of Affective Disorders, 186, 127–133.

Bagge, C. L., Glenn, C. R., & Lee, H. J. (2013). Quantifying the impact of recent negative life events on suicide attempts. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122, 359–368.

Beautrais, A. L. (2003). Suicide and serious suicide attempts in youth: a multiple-group comparison study. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 1093–1099.

Berg, J. M., Latzman, R. D., Bliwise, N. G., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2015). Parsing the heterogeneity of impulsivity: a meta-analytic review of the behavioral implications of the UPPS for psychopathology. Psychological Assessment, 27, 1129.

Black, E. B., & Mildred, H. (2014). A cross-sectional examination of non-suicidal self-injury, disordered eating, impulsivity, and compulsivity in a sample of adult women. Eating Behaviors, 15, 578–581.

Brezo, J., Paris, J., & Turecki, G. (2006). Personality traits as correlates of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide completions: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 113, 180–206.

Browne, M. W. (1991). FITMOD: A computer program for calculating point and interval estimates of fit measures. Unpublished manuscript.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2013). Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html. Accessed August 2015.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2009). Microeconometrics Using Stata. College Station: Stata Press.

Carver, C. S., Johnson, S. L., Joormann, J., Kim, Y., & Nam, J. Y. (2011). Serotonin transporter polymorphism interacts with childhood adversity to predict aspects of impulsivity. Psychological Science, 22, 589–595.

Casey, B. J., Jones, R. M., & Hare, T. A. (2008). The adolescent brain. Annals of the New York Academy of Science, 1124, 111–126.

Cyders, M. A. (2013). Impulsivity and the sexes measurement and structural invariance of the UPPS-P impulsive behavior scale. Assessment, 20, 86–97.

Cyders, M. A., & Coskunpinar, A. (2011). Depression, impulsivity and health-related disability: a moderated mediation analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 45, 679–682.

Cyders, M. A., & Smith, G. T. (2008). Emotion-based dispositions to rash action: positive and negative urgency. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 807–828.

d’Acremont, M., & Van der Linden, M. (2007). How is impulsivity related to depression in adolescence? Evidence from a French validation of the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire. Journal of Adolescence, 30, 271–282.

Dick, D. M., Smith, G., Olausson, P., Mitchell, S. H., Leeman, R. F., O’Malley, S. S., & Sher, K. (2010). Understanding the construct of impulsivity and its relationship to alcohol use disorders. Addiction Biology, 15, 217–226.

DiStefano, C., Zhu, M., & Mindrila, D. (2009). Understanding and using factors scores: considerations for the applied researcher. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 14, 1–11.

Dougherty, D. M., Mathias, C. W., Marsh, D. M., Papageorgiou, T. D., Swann, A. C., & Moeller, F. G. (2004). Laboratory measured behavioral impulsivity relates to suicide attempt history. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 34, 374–385.

Dougherty, D. M., Mathias, C. W., Marsh-Richard, D. M., Prevette, K. N., Dawes, M. A., Hatzis, E. S., & Nouvion, S. O. (2009). Impulsivity and clinical symptoms among adolescents with non-suicidal self-injury with or without attempted suicide. Psychiatry Research, 169, 22–27.

Dvorak, R. D., Lamis, D. A., & Malone, P. S. (2013). Alcohol use, depressive symptoms, and impulsivity as risk factors for suicide proneness among college students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 149, 326–334.

Eaton, D. K., Kann, L., Kinchen, S., Ross, J., Hawkins, J., Harris, W. A., & Wechsler, H. (2006). Youth risk behavior surveillance--United States, 2005. Morbidity and Mortality Surveillance Summaries, 55, 1–108.

Ernst, M., Pine, D. S., & Hardin, M. (2006). Triadic model of the neurobiology of motivated behavior in adolescence. Psychological Medicine, 36, 299–312.

Fabrigar, L. R., Wegener, D. T., MacCallum, R. C., & Strahan, E. J. (1999). Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychological Methods, 4, 272–299.

Forbes, E. E., & Dahl, R. E. (2005). Neural systems of positive affect: relevance to understanding child and adolescent depression? Development and Psychopathology, 17, 827–850.

Glenn, C. R., & Klonsky, E. D. (2010). A multimethod analysis of impulsivity in nonsuicidal self-injury. Personality Disorders, 1, 67–75.

Gvion, Y., & Apter, A. (2011). Aggression, impulsivity, and suicide behavior: a review of the literature. Archives of Suicide Research, 15, 93–112.

Harris, E. C., & Barraclough, B. (1997). Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders: a meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 170, 205–228.

Hull-Blanks, E. E., Kerr, B. A., & Robinson Kurpius, S. E. (2004). Risk factors of suicidal ideations and attempts in talented, at-risk girls. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 34, 267–276.

Johnson, S. L., Carver, C. S., & Joormann, J. (2013). Impulsive responses to emotion as a transdiagnostic vulnerability to internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150, 872–878.

Joiner, T. E., Jr., Brown, J. S., & Wingate, L. R. (2005). The psychology and neurobiology of suicidal behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 287–314.

Jollant, F., Bellivier, F., Leboyer, M., Astruc, B., Torres, S., Verdier, R., & Courtet, P. (2005). Impaired decision making in suicide attempters. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 304–310.

Klonsky, E. D., & May, A. (2010). Rethinking impulsivity in suicide. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 40, 612–619.

Lejuez, C. W., Magidson, J. F., Mitchell, S. H., Sinha, R., Stevens, M. C., & de Wit, H. (2010). Behavioral and biological indicators of impulsivity in the development of alcohol use, problems, and disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 34, 1334–1345.

Lewinsohn, P. M., Rohde, P., Seeley, J. R., & Baldwin, C. L. (2001). Gender differences in suicide attempts from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 40, 427–434.

Lynam, D. R., Miller, J. D., Miller, D. J., Bornovalova, M. A., & Lejuez, C. W. (2011). Testing the relations between impulsivity-related traits, suicidality, and nonsuicidal self-injury: a test of the incremental validity of the UPPS model. Personality Disorders, 2, 151–160.

Mann, J. J., Waternaux, C., Haas, G. L., & Malone, K. M. (1999). Toward a clinical model of suicidal behavior in psychiatric patients. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 156, 181–189.

March, J. S., Parker, J. D., Sullivan, K., Stallings, P., & Conners, C. K. (1997). The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 36, 554–565.

McKeown, R. E., Garrison, C. Z., Cuffe, S. P., Waller, J. L., Jackson, K. L., & Addy, C. L. (1998). Incidence and predictors of suicidal behaviors in a longitudinal sample of young adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 37, 612–619.

Niv, S., Tuvblad, C., Raine, A., Wang, P., & Baker, L. A. (2012). Heritability and longitudinal stability of impulsivity in adolescence. Behavior Genetics, 42, 378–392.

Nock, M. K., Holmberg, E. B., Photos, V. I., & Michel, B. D. (2007). Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors interview: development, reliability, and validity in an adolescent sample. Psychological Assessment, 19, 309–317.

Nock, M. K., Borges, G., Bromet, E. J., Alonso, J., Angermeyer, M., Beautrais, A., & Williams, D. (2008). Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 192, 98–105.

Nock, M. K., Hwang, I., Sampson, N., Kessler, R. C., Angermeyer, M., Beautrais, A., & Williams, D. R. (2009). Cross-national analysis of the associations among mental disorders and suicidal behavior: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Medicine, 6, e1000123.

Nock, M. K., Hwang, I., Sampson, N. A., & Kessler, R. C. (2010). Mental disorders, comorbidity and suicidal behavior: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Molecular Psychiatry, 15, 868–876.

Nock, M. K., Green, J. G., Hwang, I., McLaughlin, K. A., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Kessler, R. C. (2013). Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry, 70, 300–310.

Peterson, C. M., Davis-Becker, K., & Fischer, S. (2014). Interactive role of depression, distress tolerance and negative urgency on non-suicidal self-injury. Personal Mental Health, 8, 151–160.

Pokorny, A. D. (1983). Prediction of suicide in psychiatric patients. Report of a prospective study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 40, 249–257.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401.

Rawlings, J., Shevlin, M., Corcoran, R., Morriss, R., & Taylor, P. J. (2015). Out of the blue: untangling the association between impulsivity and planning in self-harm. Journal of Affective Disorders, 184, 29–35.

Reynolds, B., Ortengren, A., Richards, J. B., & de Wit, H. (2006). Dimensions of impulsive behavior: personality and behavioral measures. Personality and Individual Differences, 40, 305–315.

Rudolph, K. D. (2008). Developmental influences on interpersonal stress generation in depressed youth. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 117, 673–679.

Sharma, L., Markon, K. E., & Clark, L. A. (2014). Toward a theory of distinct types of “impulsive” behaviors: a meta-analysis of self-report and behavioral measures. Psychological Bulletin, 140, 374–408.

Sheehan, D. V., Sheehan, K. H., Shytle, R. D., Janavs, J., Bannon, Y., Rogers, J. E., & Wilkinson, B. (2010). Reliability and validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71, 313–326.

Stewart, S. M., Kennard, B. D., Lee, P. W., Mayes, T., Hughes, C., & Emslie, G. (2005). Hopelessness and suicidal ideation among adolescents in two cultures. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 46, 364–372.

Stewart, J., Kim, J., Esposito, E. C., Gold, J., Nock, M. K., & Auerbach, R. P. (2015). Predicting suicide attempts in depressed adolescents: clarifying the role of disinhibition and child sexual abuse. Journal of Affective Disorders, 187, 27–34.

Stoltenberg, S. F., Batien, B. D., & Birgenheir, D. G. (2008). Does gender moderate associations among impulsivity and health-risk behaviors? Addictive Behaviors, 33, 252–265.

Swann, A. C., Dougherty, D. M., Pazzaglia, P. J., Pham, M., Steinberg, J. L., & Moeller, F. G. (2005). Increased impulsivity associated with severity of suicide attempt history in patients with bipolar disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 1680–1687.

van Alphen, N., Stewart, J. G., Esposito, E. C., Pridgen, B., Gold, J., & Auerbach, R. P. (2016). Predictors of rehospitalization for depressed adolescents admitted to acute psychiatric treamtent. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Venta, A., & Sharp, C. (2014). Extending the concurrent validity of the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview to inpatient adolescents. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 36, 675–682.

Whiteside, S. P., & Lynam, D. R. (2001). The five factor model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 669–689.

Whiteside, S. P., Lynam, D. R., Miller, J. D., & Reynolds, S. K. (2005). Validation of the UPPS impulsive behaviour scale: a four-factor model of impulsivity. European Journal of Personality, 19, 559–574.

Witte, T. K., Merrill, K. A., Stellrecht, N. E., Bernert, R. A., Hollar, D. L., Schatschneider, C., & Joiner, T. E., Jr. (2008). “Impulsive” youth suicide attempters are not necessarily all that impulsive. Journal of Affective Disorders, 107, 107–116.

Yen, S., Shea, M. T., Sanislow, C. A., Skodol, A. E., Grilo, C. M., Edelen, M. O., & Gunderson, J. G. (2009). Personality traits as prospective predictors of suicide attempts. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 120, 222–229.

Acknowledgments

Randy P. Auerbach was partially supported through funding from: National Institute of Mental Health K23MH097786, the Klingenstein Third Generation Foundation Adolescent Depression Fellowship, the Tommy Fuss Fund, and the Simches Fund. Jeremy G. Stewart was supportedthrough the Skip Pope Award for Young Investigators awarded by McLean Hospital.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study with human subjects was in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Auerbach, R.P., Stewart, J.G. & Johnson, S.L. Impulsivity and Suicidality in Adolescent Inpatients. J Abnorm Child Psychol 45, 91–103 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0146-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0146-8