Abstract

User adoption of mobile payment (m-payment) is low compared to the adoption of traditional forms of payments. Lack of user trust has been identified as the most significant long-term barrier for the success of mobile finances systems. Motivated by this fact, we proposed and tested an initial trust theoretical model for user adoption of m-payment systems. The model not only theorizes the role of initial trust in m-payment adoption, but also identifies the facilitators and inhibitors for a user’s initial trust formation in m-payment systems. The model is empirically validated via a sample of 851 potential m-payment adopters in Australia. Partial least squares structural equation modelling is used to assess the relationships of the research model. The results indicate that perceived information quality, perceived system quality, and perceived service quality as the initial trust facilitators are positively related to initial trust formation, while perceived uncertainty as the initial trust inhibitor exerts a significant negative effect on initial trust. Perceived asset specificity is found to have insignificant effect. In addition, the results show that initial trust positively affects perceived benefit and perceived convenience, and these three factors together predict usage intention. Perceived convenience of m-payment is also found to have a positive effect on perceived benefit. The findings of this study provide several important implications for m-payment adoption research and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The application of third generation (3G) communication technologies has triggered the rapid development of mobile commerce. Among the myriad mobile commerce applications, such as mobile advertising and mobile gaming, mobile payment (m-payment) systems, which offer the advantage of anytime, anywhere payment services through mobile phones are perhaps the most vital (Dahlberg et al. 2008). Despite the availability of the enabling technologies and the promising possibilities that m-payment systems offer, their penetration and adoption is relatively low, compared to other recent forms of cashless, noncontact payment modes such as credit cards and online payment systems (Garrett et al. 2014). For example, only 17.1 % of mobile internet users have ever used m-payment in China (Zhou 2014). In the US, this figure is 12 % (Smith et al. 2012). A similar trend of low adoption rates for m-payment systems have been observed in many European countries (Kapoor et al. 2014) such as UK and France. Spurred by the low adoption rates for m-payment services worldwide, service providers need to understand the factor affecting mobile user behavior and adopt effective measures to encourage and facilitate their adoption and usage of m-payment services.

M-payment is a form of online payment made over a mobile network where transactions between unknown entities can take place, such as checking balance, transferring money and conducting payment via mobile devices (Yang et al. 2012). Compared to online payment, a main advantage of m-payment is ubiquity (Shaw 2014). That is, with the help of mobile devices and networks, users have been freed from temporal and spatial constraints. They can conduct m-payment at anytime from anywhere. This provides convenience and value to users, which may facilitate their adoption of m-payment services. However, due to the virtuality and lack of control, m-commerce involves great uncertainty and risk (Yan and Yang 2015; Lin et al. 2014). To some extent, compared to online payment, m-payment involves greater risk (Yan and Pan 2014). For example, wireless networks are more vulnerable to hacker attacks and information interception. Mobile encryption systems are not as intact and robust as online encryption systems (Zhou 2011a). This leads to users’ concern about m-payment security. They doubt whether m-payment can effectively protect their account and payment from potential problems. Compared to wired network, mobile networks have limited bandwidth and less stable connections therefore, users may encounter slow responses and service interruptions (Gao and Bai 2014). In addition, compared to desktop computers and many laptops, mobile devices such as cell phones have some constraints such as small screens, low resolution and inconvenient input, which make it difficult for mobile users to search for and view relevant information. These problems may increase users’ concern on payment security and decrease their usage intention. Service providers need to establish user trust in order to mitigate their perceived risk and encourage their usage of m-payment.

While user trust has been found to be a significant adoption facilitator in multiple information system (IS) contexts (Wu et al. 2014a, b; Luo et al. 2014; Zhou et al. 2014), it has not been sufficiently examined in the context of m-payment systems (Chandra et al. 2010; Yan and Pan 2014). Initial trust develops when users interact with m-payment for the first time (McKnight et al. 2002; Zhou 2014). Thus, in this research, we are mainly concerned with initial trust that users develop during their first interaction with m-payment systems. Establishing users’ initial trust is critical for m-payment user adoption. On one hand, due to the lack of previous experience, users will perceive great uncertainty and risk when they adopt m-payment for the first time. They need to build initial trust to overcome perceived risk. On the other hand, the switching cost is low. Users may switch back to online payment or traditional payment methods if they cannot build initial trust in m-payment systems. Thus it is crucial for service providers to establish users’ initial trust to acquire new users and retain existing ones.

A closer look at the m-payment literature reveals that few studies have been conducted to examine initial trust in m-payment. Most previous studies have focused on using information technology adoption theories such as technology acceptance model (TAM) (Schierz et al. 2010; Kim et al. 2010; Yan and Pan 2014; Shaw 2014), innovation diffusion theory (IDT) (Lu et al. 2011; Li et al. 2014), and the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT) (Wang and Yi 2012; Slade et al. 2014) to examine m-payment user behavior. Technological perceptions, such as perceived usefulness, relative advantage and performance expectancy are found to affect m-payment adoption intention (Yan and Yang 2015; Slade et al. 2014; Shaw 2014). However, the role of initial trust on m-payment user behavior has seldom been examined (Lin et al. 2014; Yan and Pan 2014). As noted earlier, the high perceived risk and low switching cost highlight the necessity to build users’ initial trust in order to encourage and facilitate their adoption and usage of m-payment. Motivated by this, in this research we emphasize the importance of initial trust in m-payment systems and identify the factors affecting initial trust. The objective of this study is to extend the current m-payment literature by investigating the facilitators and inhibitors of initial trust in m-payment systems as well as influences of initial trust on user adoption of m-payment systems. This study will improve our understanding of initial trust in mobile payment (Yang 2015; Zhou 2014).

We use the valence framework as a broad framework to guide us in drawing a big picture of the research model. The valence framework posits that perceived benefit and perceived risk are the two fundamental drivers of consumer decision-making (Lu et al. 2011), and consequently might offer an explanation as to how potential users form their initial trust in m-payment. However, the valence framework does not articulate the dimensions of perceived benefit and risk, which researchers believe may vary from system to system (Kim et al. 2008). Thus, it is necessary to explore the specific dimensions of the perceived benefits and risks associated with using m-payment in order to gain a deeper understanding of m-payment initial trust. Therefore, we propose an extension of the benefit and risk dimensions of the valence framework to adapt it to the m-payment environment.

Specifically, we used the three quality dimensions in the Information System Success Model (ISS model) to reflect the specific benefits of using m-payment systems. ISS model provides a comprehensive understanding of IS success from a quality perspective (Delone and Mclean 2004). It posits that three quality dimensions, namely perceived system quality, perceived information quality and perceived service quality, positively affect users’ perception of benefits and IS success. Users’ perceptions of benefits of using a new system are based on their judgement of system, information and service quality (Zhou 2013). Previous studies (e.g. Lee and Chung 2009; Gao and Bai 2014) have used the quality dimensions of ISS model to represent users’ perceived benefits for online shopping and mobile services. Based on previous research, we believe that these three quality dimensions are good indicators of perceived benefits of using m-payment systems. Therefore, in this study, the three quality dimensions of ISS model are incorporated into the valence framework. They reflect the specific benefits of using m-payment and are proposed as the potential initial trust facilitators.

We adopt the two cost dimensions in the Transaction Cost Economics (TCE) model to reflect the specific risks of using m-payment systems. TCE model explains why a transaction subject chooses a particular form of transaction instead of others based on their perception of transaction costs (Williamson and Ghani 2012). The costs dimensions, including perceived uncertainty and perceived asset specificity, are the antecedents of the overall transaction costs associated with using a new system. They reflect the potential risks of using the new system. Many studies (e.g. Wang et al. 2012; Yen et al. 2013) have demonstrated that users view perceived uncertainty and asset specificity as potential risks associated with new systems, such as online shopping and online payment. Thus, the two cost dimensions of TCE are employed to describe the specific risks of using m-payment and are considered as the initial trust inhibitors. We believe that the integration of the theories is necessary and useful, which helps us better capture the characteristics of m-payment and explain the facilitators and inhibitors of initial trust development in greater details.

This study has two significant contributions to the trust and m-payment literature. First, different from previous studies focusing on technological perceptions such as perceived usefulness affecting adoption intention of m-payment services, this study takes an novel approach by examining the role of initial trust in m-payment adoption. It advances our understanding on user adoption of m-payment by incorporating the integral role of initial trust into innovative technology acceptance. Second, to our knowledge, this study is among the first to investigate the factors influencing initial trust by simultaneously exploring the facilitating factors and inhibiting factors based on the valence framework, the ISS model and the TCE model. We specifically identified three facilitators and two inhibitors of initial trust by expanding the original benefit and risk dimensions in the valence framework and incorporating the ISS model and the TCE model into the valence framework. A comprehensive study about trust facilitators and inhibitors offers the potential to derive important managerial implications regarding how m-payment services could be marketed more effectively, thus improving user trust and leading to greater user adoption. To sum up, the study introduces an initial trust theoretical model for user adoption of m-payment systems and further delineates significant initial trust facilitators and inhibitors thereby making significant contributions to the field of m-payment and trust. We expect this study to offer instrumental insights to mobile service providers and m-payment vendors with regards to user trust and adoption of m-payment services.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 M-payment user adoption

M-payment is defined as any payment in which a mobile device is utilized to initiate, authorize, and confirm a commercial transaction (Chandra et al. 2010). M-payment is a natural evolution of electronic payment, and enables feasible and convenient mobile commerce transactions (Thakur and Srivastava 2014). M-payment is typically made remotely via premium rate SMS, WAP billing, Mobile Web, Direct-to-subscribers’ bill and direct to credit cards.

As an emerging service, m-payment has not been widely adopted by users. Thus researchers have paid attention to identify the factors affecting user adoption. They often used the traditional information system models such as TAM, IDT and UTAUT as the basis of their research, investigating whether the models’ theoretical constructs are also likely to influence the consumer acceptance of a m-payment service (Slade et al. 2013; Thakur 2013; Yan and Yang 2015; Yan and Pan 2014; Shaw 2014), or examining whether consumers are ready to adopt m-payments based on the assumed factors (E. Slade et al. 2014). For example, drawing upon TAM, Kim et al. (2010) noted that individual differences and m-payment system characteristics affect Korean consumers’ m-payment usage intention through perceived usefulness and ease of use. Individual differences include innovativeness and knowledge on m-payment, whereas m-payment system characteristics include mobility, reachability, compatibility and convenience. Schierz et al. (2010) reported that perceived compatibility and attitude towards use have strong effects on the acceptance of m-payment in Germany. The attitude towards use is further determined by perceived compatibility, perceived usefulness, subjective norm, perceived security, individual mobility, perceived security and perceived ease of use. Kapoor et al.’s (2014) study sought to compare the predictive capacity of different sets of competing attributes on the diffusion of the Interbank m-payment service in India; relative advantage, compatibility, complexity and trialability are the key factors predicting behavioral intention.

In addition to technological perceptions such as perceived usefulness and relative advantage, trust also has a significant effect on m-payment user behavior. Chandra et al. (2010) extended TAM with trust to explore adoption of m-payments in Singapore and found that trust is the most significant predictor of behavioral intention. Shin (2010) explored adoption of m-payments in the US with an extended model of TAM and noted that perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, trust and perceived risk affect users’ adoption of m-payment. Yan and Yang (2015) examined users’ m-payment adoption in China from a trust perspective and demonstrated a significant positive effect of trust on usage intention. Compared to considerable research on the effects of technological perceptions on usage intention of m-payment, less research effort has been devoted to examining the effect of user trust on m-payment usage intention (Shaw 2014; Lin et al. 2014). Due to the inherently greater risks of uncertainty, a lack of prior experience and developing a sense of a loss of control when conducting transactions within the m-payment environment (Mostafa 2015), initial trust appears to be even more important in determining the intention to adopt a m-payment service (Zhou 2014; Yan and Pan 2014). Nevertheless, the previous studies tend to overlook the role of initial trust in users’ adoption of m-payment. As such, more research is required to examine the antecedents and consequences of initial trust in the m-payment context.

2.2 Initial trust

Trust has received considerable attention in the electronic commerce context due to the great uncertainty and risk involved in online transactions. Trust has been found to affect user adoption of various services, such as internet banking (Susanto et al. 2013), online social networks (Wu et al. 2014a, 2014b) and mobile shopping (Yang 2015). Mayer et al. (1995) described “trust” as the belief of the trustor that the trustee will fulfil the trustor’s expectations without taking advantage of the trustor’s vulnerabilities. In the online transaction scenario, McKnight et al. (2002) conceptualize trust as the belief which allows consumers to willingly become vulnerable to online vendors for an expected service after duly considering the vendor characteristics. Trust has long been a catalyst in buyer-seller transactions, providing buyers with high expectations of satisfying exchange relationships (Lin et al. 2014).

Some researchers examined the initial trust that consumers develop during the first interaction with online vendors and indicated that initial trust is the most important factor in new consumers making their first purchase because an online transaction is only performed after getting their initial trust (Kim 2012; Luo et al. 2014; Zhou et al. 2014). Various factors are identified to affect initial trust. These factors can be broadly grouped into three categories. The first category of factors is related to website characteristics. Users may rely on their perceptions of a website to form their initial trust. Website quality is a significant determinant of initial trust (Lin 2011). Other factors such as information quality, site appeal and usability also affect initial trust (Nicolaou and McKnight 2006; Zhou 2011b). The second category of factors is related to company. Reputation is a strong factor affecting initial trust as it reduces the uncertainty and risks associated with online transaction (Li et al. 2008). The third category of factors is related to user. Trust propensity, which reflects a natural tendency, has a significant effect on initial trust (Kim et al. 2008). The fourth category of factors is related to third parties. Users may transfer their trust in third parties to websites. These trust determinants include portal affiliation, web assurance seals, brand association, and peer endorsement (Sia et al. 2009; Hu et al. 2010). It can be noted that factors influencing initial trust are mainly derived from the benefit perspectives where users rely on those facilitating factors to build their initial trust in online vendors. Nevertheless, factors that inhibit the initial trust building, such as uncertainty and risk, have received little attention, even though they are considered important factors affecting consumer online behavior.

Compared to the abundant research on online trust, there is less research on mobile trust (Gao and Yang 2014; Lin et al. 2014). Siau and Shen (2003) divided mobile trust into initial trust and continuous trust, both of which are affected by the factors related to mobile vendor and technology. Li and Yeh (2010) noted that design aesthetics affect mobile trust through perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use and customization. The study of Luo et al.’s (2010) conjointly examined multi-dimensional trust and multi-faceted risk perceptions in the initial adoption stage of the mobile banking services. Zhou (2011b) identified the factors affecting initial trust in mobile banking. The results showed that structural assurance and information quality are the main factors affecting user trust, which in turn affects perceived usefulness and usage intention. Mostafa (2015) examined consumers’ acceptance of mobile banking in Egypt based on TAM and TRA. The study confirmed that intention to use mobile banking is based on technology and trust attitudes. Also, attitude toward technology was found to exert higher contribution to intention to use mobile banking than trust attitude. In the context of m-payment, Chandra et al. (2010) reported the effect of trust on user adoption of m-payment systems. Drawing on both perspectives of self-perception-based and transference-based factors, Zhou (2014) examined user trust in m-payment. Self-perception-based factors include ubiquitous connection and effort expectancy, whereas transference-based factors include structural assurance and trust in online payment. Yan and Yang (2015) explored user trust in m-payment and the findings indicated that perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness, structure assurance and ubiquity have a significant effect on users’ trust, which further affect user usage intention. José Liébana-Cabanillas et al. (2014) investigated the moderating effect of the consumer’s gender in the use of m-payment and demonstrated that the impact of the perceived trust in the m-payment system on the attitude towards it is significantly stronger amongst women. Zhou (2015) conducted an empirical examination of users’ switch from online payment to mobile payment and found a positive effect of trust in online payment on user perceptions of m-payment. Similarly, Yan and Pan (2014) examined users’ acceptance of m-payment in China from a trust transfer perspective and revealed that trust of online payment, structural assurance, perceived ease-of-use and perceived usefulness are positively related to initial trust in m-payment.

From these studies, we have found that the majority of previous research on mobile trust does not distinguish initial trust from ongoing trust; instead they examine the general perception of trust from users who have had experience in using m-payment. However, initial trust differs from ongoing trust in several ways. Users’ initial trust is not based on any kind of prior experiences with a service provider. It is temporary and built in a short period (Kim 2012). As a form of trust developed without prior experience, it presumes that actors do not yet have credible, meaningful information about, or affective bonds with each other (Lin et al. 2014). In contrast, users who have conducted transactions begin to build ongoing trust with the service provider if they are satisfied with the first interaction. If they are dissatisfied, they have distrust toward the service provider. Initial trust can determine the first transaction and set the tone for a future relationship (Yang 2015). Getting initial trust is more important to new vendors who do not have a well-known brand or are small in scale (Hu et al. 2010).

While there are marked differences between initial trust and ongoing trust, little attention has been paid to understanding potential adopters’ initial trust in m-payment systems (Lin et al. 2014; Zhou 2014). Furthermore, among the limited studies on initial trust, which have mainly concentrated on users’ technological perceptions, such as ease of use, perceived usefulness, structural assurance, ubiquitous connection and information quality that positively affect the development of initial trust, while factors that play a negative role in initial trust formation, such as perceived uncertainty and risk, have seldom been tested in the context of m-payment. Only focusing on the facilitating factors may limit our understanding of initial trust. Since the inhibitor of initial trust has rarely been explored, it is necessary to conduct an empirical research to identify the factors affecting initial trust in m-payment systems from a facilitator-inhibitor perspective.

2.3 Valence framework

In this study, the valence framework serves as the useful theoretical basis on which both initial trust facilitators and inhibitors are identified. This framework uses a “cognitive-rationale” customer decision-making model that examines customer behavior by considering both positive and negative attributes (Peter and Tarpey 1975). Derived primarily from the economics and psychology literature, this framework considers perceived benefit and perceived risk to be the two fundamental aspects of consumer decision-making. The perceived benefit aspect assumes that customers are motivated to maximize its positive aspects, while the perceived risk aspect characterizes customers as motivated to minimize any expected negative effect.

While the valence framework is a good candidate for our study, we believe that a specific extension of the valence framework serves our research purposes better than its original formulation. Previous studies show that the valence framework is a valid model for the e-commerce environment (Kim et al. 2008, 2009a, b, c); however, several extensions are required to adapt it to the mobile environment (Lu et al. 2011; Lin et al. 2014). In the m-payment services context, we need to capture its more innovative features when examining user trust. Meanwhile, compared to online payment, special attention needs to be devoted to the greater uncertainty and risk of m-payment systems due to the vulnerability of wireless and internet communication platforms and the technical capability of service providers. Thus, modeling m-payments’ initial trust solely on generalized constructs (i.e. perceived benefit and perceived risk) used in the valence framework is insufficient because individuals are concerned about the specific aspects of m-payment payment services, such as system quality, information quality, privacy and security protection, and specific asset investment. We believe that the unique characteristics of m-payment systems need to be taken into account, which will advance our understanding of factors influencing initial trust development.

In addition, since the adoption of m-payment can be viewed as the adoption of a new information system and the selection of a payment method, this study extends the valence framework by incorporating the ISS model and the TCE model to identify the specific facilitators and inhibitors of initial trust respectively. We propose a more comprehensive initial trust model which integrates the ISS model to describe factors facilitating initial trust building, and the TCE to understand factors inhibiting initial trust formation. To investigate facilitators in detail, three factors derived from the ISS model, system quality, information quality, and service quality, are identified. They reflect the perceived benefit aspects and conceptually consistent with the positive valences in the valence framework. Therefore, ISS model is suitable to investigate the factors that facilitate initial trust building. Along with these three factors related to trust facilitators, we also identified two trust inhibitors (i.e. perceived uncertainty and perceived asset specificity) based on the TCE model. Different from conventional payment services, m-payment users have to install additional software on their phone, acquire relevant m-payment knowledge for using the m-payment services and expose themselves to a risky wireless environment (Thakur and Srivastava 2014). This implies that transaction costs associated with using m-payment, such as asset specificity and perceived uncertainty, may be influential in users’ risk perception and initial trust building. These two factors derived from the TCE model reflect perceived risk aspects (i.e. negative valences) and fit nicely into in the valence framework. Thus, using the TCE model to explore the trust inhibitors is reasonable. The constructs used in our model are more specific than the generalized constructs used in the original valence framework.

It is worth noting that there is no study to date that attempts to understand users’ initial trust in m-payment systems from facilitators-inhibitors perspectives by integrating ISS model and TCE model and incorporating them into the valence framework. This study tries to fill this gap by synthesizing these three theories. Such synthesis will enable a better explanation of initial trust in m-payment systems. This study also represents two aspects of extensions from previous research, including context extension (i.e. from traditional offline/online payment to m-payment) and theory extension (i.e. from TAM, IDT and UTAUT to the valence framework, ISS model and TCE model).

2.4 ISS model

In this study, the ISS model is used to identify the facilitators of initial trust in m-payment systems. The ISS model purports to describe the information system success measures (DeLone and McLean 1992). It dictates that system quality and information quality affect use and user satisfaction, which further leads to individual impact and organizational impact. Later, DeLone and McLean (2004) developed an updated model and included service quality into the model.

Since its inception, the ISS model has been widely used to examine user adoption of various information systems. Song and Zahedi (2007) examined the effects of system quality and information quality on user trust in health infomediaries. Chen and Cheng (2009) adopted the ISS model to predict user intention to conduct online shopping. Teo et al. (2008) integrated trust and the ISS model to examine electronic government success. Recently, the ISS model has been used to understand mobile user behavior. Chatterjee et al. (2009) conducted a qualitative study to identify the success factors for mobile work in healthcare. Kim et al. (2009a, b, c) applied the ISS model to examine ubiquitous computing use and u-business value. Lee and Chung (2009) found that system quality, information quality and interface design quality affect user trust in and satisfaction with mobile banking. Zhou (2011c, 2013) drew on the ISS model and other theories to examine critical success factors of mobile website adoption and continuance intention of m-payment services. Gao and Bai (2014) employed ISS model to explain user continuance intention of mobile social networking services. They found system quality positively affect satisfaction and perceived usefulness while information quality is positively related to flow and perceived usefulness.

As evidenced by these studies, although the ISS model has been widely used to examine user behavior, it has seldom been tested in the context of m-payment, which represents an emerging information technology. Accordingly, research generalizing the ISS model to m-payment is needed. On the other hand, since m-payment can be regarded as something of an information system, it is appropriate to use ISS model as the theoretical foundation for the research model of this study. Moreover, the three quality attributes reflecting the usage benefits are found to positively affect user trust in mobile banking (Zhou 2011b), which provides support for our conceptual model that theorizes the three quality attributes as potential trust facilitators in the m-payment setting.

2.5 TCE model

The TCE model was originally proposed by Coase (1937), and can be used to explain why a transaction subject chooses a particular form of transaction instead of others (Williamson 1975). Rooted in economic theory, TCE theoretically explain the buyer–supplier relationship in empirical studies of both management and marketing (Rindfleisch and Heide 1997). Two assumptions underlie the choice between market and hierarchy, namely, bounded rationality and opportunism. Bounded rationality refers to the fact that people have limited memories and limited cognitive processing power. People therefore cannot fully process all the information they have, and cannot accurately work out the consequences of this information. Opportunism, on the other hand, holds that people will act to further their own self-interest. The caveat is, some people may not always be entirely honest and truthful about their intentions (Teo and Yu 2005; Williamson and Ghani 2012).

Moreover, TCE considers three situational conditions, i.e. uncertainty, asset specificity, and frequency (Williamson 1975). There is uncertainty in the transaction when one cannot be sure that the other party will not go out of business or try to renegotiate the contract at some future time during the life of the contract (Teo and Yu 2005). Specific assets are regarded to be locked into a particular exchange relationship, such that a specific asset which meets a particular customer’s needs cannot be offered by others (Williamson 1985). In addition, frequency with exchanges refers to the number of times that an economic actor has dealings (Kim and Li 2009). However, many researchers have failed to confirm empirically that frequency is related to a choice of governance structure (Rindfleisch and Heide 1997).

Compared to the field of economics related disciplines (Verbeke and Kano 2013; Schneider et al. 2013), there have been relatively few IS studies which apply TCE in the online context (Wu et al. 2014a, b). Furthermore, scant academic research is available on the investigation of TCE in the mobile environment. Several studies have found that transaction costs influence a customer’s buying intention. Kim and Li (2009) relied on TCE in examining the online travel market, and investigated customer satisfaction and loyalty with respect to the transaction costs of dealing over the internet. Yen et al. (2013) extended TCE to C2C environment and investigated the determinants of bidders’ repurchase intention in online auctions. The findings revealed that bidders’ repurchase intention were negatively related to transaction costs, which in turn were affected by asset specificity, product uncertainty and interaction frequency.

Given that users’ adoption and usage of m-payment represent a kind of transaction behavior between users and m-payment service providers (e.g., banks, online vendors, credit card companies, or telecom operators), users may take into consideration the transaction costs involved in bilateral exchanges while deciding whether or not to adopt m-payment systems. As such, TCE is appropriate for explaining why users are willing to adopt the new m-payment technology rather than continuing to use their current methods of conducting payment transactions, especially since adopters will be required to obtain a specific payment instrument and knowledge to switch to the new payment method.

Furthermore, as m-payment involves great risk due to the vulnerability of both the mobile devices and networks to hacker attack, users’ perception of uncertainty and asset specificity are likely to increase transaction costs associated with m-payment services. In this situation, users may take certain actions, such as switching to alternative payment methods, to reduce such transaction costs, which may pose difficulty in initial trust building in m-payment systems. Users may not be able to develop initial trust during the first interaction with m-payment systems when facing high transaction costs stemming from high perceived uncertainty and asset specificity. On this basis, TCE is used as the theoretical foundation for the research model of this study and the dimensions of TCE can be considered as potential inhibitors of initial trust formation. Some studies investigating the factors that affect online shopping behavior choose to omit transaction frequency from their research models (Liang and Huang 1998; Teo et al. 2004). In line with these studies, we exclude transaction frequency and only examine the effects of perceived uncertainty and perceived asset specificity on initial trust.

3 Research model and hypotheses development

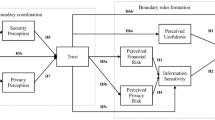

The research model used to guide the study is shown in Fig. 1. It depicts that the perceived system quality, perceived information quality and perceived service quality as positive valences are potential trust facilitators, while perceived uncertainty and perceived asset specificity acting as negative valences are the potential trust inhibitors. It also describes the consequences of initial trust. In this study, the m-payment initial trust reflects a willingness to be in vulnerability based on the positive expectation toward another party’s future behavior (Mayer et al. 1995). It includes three dimensions: perceived ability, perceived integrity and perceived benevolence (Song and Zahedi 2007; Hwang and Lee 2012). Perceived ability means that m-payment service providers have the knowledge and expertise necessary to fulfil their tasks. Perceived integrity means that m-payment service providers keep their promises and do not deceive users. Perceived benevolence means that m-payment service providers are concerned with users’ interests, not just their own benefits. The following sections elaborate on the theory base and derive the hypotheses.

3.1 Perceived system quality

As noted earlier, due to the lack of direct experience, users need to rely on their own perceptions such as system quality, information quality and service quality to form their initial trust in m-payment. The concept of system quality, first introduced by DeLone and McLean (1992), is defined as quality manifested in a system’s overall performance and measured by individuals’ perceptions (Delone and Mclean 2004). Vendors are faceless on the m-payment, so their systems’ quality becomes the “online storefront” by which first impressions are formed. In online shopping, many studies (Ahn et al. 2007; Bock et al. 2012; McKnight et al. 2002) have revealed that if a consumer perceives a vendor’s system to be of high quality, he/she will be likely to have high levels of trust in the vendor’s competence, integrity and benevolence, and will be willing to spend money with that vendor.

Perceived system quality in this study reflects the access speed, ease of use, navigation and appearance of m-payment system. Due to the constraints of mobile terminals such as small screens and inconvenient input, users may find it difficult to search for information with m-payment (Zhou 2011b). Thus an interface with powerful navigation, clear layout and prompt responses may be critical to using m-payment. If m-payment systems are difficult to use and have poor interface design, users may feel that service providers lack the ability and integrity necessary to offer quality services. Thus, system quality may affect user trust. Vance et al. (2008) report that system quality including navigational structure and visual appeal affects users’ trust in mobile commerce technologies. Lee and Chung (2009) also note that system quality affects user trust in mobile banking. They argue when users find mobile banking systems difficult to use, they may feel that service providers have not invested effort and resources to offer an easy-to-use system to them. This will affect their evaluation on the credibility and benevolence of service providers. In addition, as mobile networks have limited bandwidth and unstable connections, users may encounter slow responses and service interruptions (e.g., network breakdown in the middle of a transaction) under some circumstances. If users encounter these problems during the first interaction with m-payment systems, they may doubt whether mobile service providers have enough ability and benevolence to provide quality services. This may decrease their initial trust. Therefore, we hypothesize:

-

H1: Perceived system quality has a positive influence on initial trust.

3.2 Perceived information quality

In this study, perceived information quality reflects the relevance, sufficiency, accuracy and timeliness of the information provided by m-payment systems. Users expect to use m-payment to pay bills and acquire their payment information at anytime from anywhere. If this information is irrelevant, inaccurate or out-of-date, users may feel that service providers lack the ability to offer quality services to them (Lee et al. 2015). This may affect their initial trust. For example, if m-payment is not asynchronous with online payment, users may acquire the wrong information on account balances when they have conducted payment with online banking. This will decrease users’ trust in m-payment. Zhou (2011c) indicates that poor information quality has a negative effect on user trust in mobile website. Information quality also has been identified to affect user trust in mobile banking (Lee and Chung 2009), health infomediaries (Zahedi and Song 2008) and inter-organizational data exchange (Nicolaou and McKnight 2006). M-payment users always expect to obtain complete, precise and timely information about transactions, such as transaction record and documentation. Lack of the information is considered risky by current m-payment users as it makes follow-up on past payments more difficult (Mallat 2007). Users suspect that without proper documentation they could easily end up spending more money than they intended. Furthermore, without a receipt a payer has no proof of the payment transaction, therefore making any claims for a refund difficult (Mallat 2007). Users may also worry that once the payment has been completed, whether the return short message can come quickly. They are unsure whether the payment had taken place or not and whether or not the payment had been charged. If there is a delay in the information delivery process, it would lead to users repeating the purchase order operation, with a result that a single product is purchase twice. In this case, users may perceive lack of control in using the m-payment services (Zhou 2013; Jung et al. 2009; Gao and Bai 2014). It may further lead users to feel that service providers have not spent enough effort and investment on m-payment. The above argument leads to the following hypothesis:

H2: Perceived information quality has a positive influence on initial trust.

3.3 Perceived service quality

Perceived service quality reflects reliability, responsiveness, assurance and personalization. Providing quality services will signal service providers’ ability and benevolence. In contrast, if service providers present unreliable services and slow responses to users, users cannot build trust in them. Thus, service quality may affect user trust. Extant research has disclosed the effect of service quality on user trust in online vendors (Kassim and Abdullah 2010) and mobile service providers (Zhou 2013; Lee and Chung 2009). Mallat (2007) emphasizes that mobile network reliability is a common concern among the users who are worried that the network connection may fail in the middle of a payment transaction. If users encounter unreachable service connection and service interruption during the first interaction with m-payment systems, they may doubt service providers’ ability to offer quality services to users (Zhou 2011c, 2013; Lee and Chung 2009). This will lower their initial trust. Users expect to use m-payment to complete payment transactions within a short time and with little effort. A personalized and prompt service can reduce users’ time and effort expended on payment transactions and help them obtain enjoyable experiences, which may positively contribute to the initial trust. On the contrary, poor service quality may undermine user experience and negatively affect their perceptions of m-payment systems’ ability, integrity and benevolence as it may incur financial loss and users may need to spend much effort on information searching and scrutinizing, thereby inhibiting their initial trust formation. Users may not expect to form trust from unreliable and slow service. Thus, we suggest,

-

H3: Perceived service quality has a positive influence on initial trust.

3.4 Perceived uncertainty

All transactions are conducted under a certain level of uncertainty. Uncertainty arises from imperfect foresight and the human inability to solve complex problems associated with the transaction, which can be regarded as the cost associated with the unexpected outcome and asymmetry of information (Williamson 1985). The TCE model posits that the level of uncertainty is likely to affect whether a decision maker chooses to insource or outsource (Williamson and Ghani 2012). Wang (2002) indicates that uncertainty has a positive influence on the contractor’s post-contractual opportunism as perceived by the client, but a negative influence on the success of software outsourcing.

Perceived uncertainty in this study is defined as the extent to which the potential user believes that using m-payment includes the possibility of security and privacy threats. When a new innovative service such as m-payment is introduced, potential users may feel fearful about using it for payment transactions due to security and privacy concerns (Chandra et al. 2010). In the early stages of m-payment adoption, disappointing performance of privacy and security protection causes doubt from users on its ability to deliver consistent, reliable and secure service (Siau and Shen 2003). At the time of a transaction, the m-payment service provider collects the names, phone numbers, home addresses and credit card information of users. Some service providers pass the information on to spammers, telemarketers, and direct mailers. The illegal collection and sale of personal information could harm legitimate users in a variety of ways, ranging from simple spamming to fraudulent credit card charges and identity theft (Kim et al. 2008). Therefore, for many potential m-payment users, loss of privacy is a main concern, and the protection of transaction information is crucial. In a recent survey, 92 % of survey respondents indicated that they do not trust companies to keep their information private even when the companies promise to do so (Hong and Thong 2013). These increasing consumer concerns lower their initial trust for m-payment transactions. Thakur and Srivastava (2014) note that compromise of privacy is perceived as a risk by many m-payment users who therefore are unwilling to disclose their information to payment service providers. They are concerned that their purchases would be tracked, personal information misused or that they would begin to receive unsolicited messages and advertisements if they registered to a new payment system. Several empirical studies have revealed that security and privacy concerns are a major inhibitor of trust formation in the context of online shopping and mobile commerce (Kim et al. 2008; Liébana-Cabanillas et al. 2014). Thus, it is hypothesized that:

-

H4: Perceived uncertainty has a negative influence on initial trust.

3.5 Perceived asset specificity

According to TCE, one salient attribute among the components of transactions is the asset specificity, which refers to durable investments that are undertaken in support of particular transactions (Williamson 1985). Rindfleisch and Heide (1997) define asset specificity as investments in physical or human assets that are dedicated to a particular business partner and whose redeployment entails considerable switching costs. As such, a specific asset is significantly more valuable in a particular exchange than in an alternative exchange and results in a ‘lock-in’ effect that causes hold-up problems (Williamson and Ghani 2012; Williamson 1985). Thus, the value of assets with high specificity is greatly diminished if they must be redeployed.

Asset specificity manifests in different forms: it can be a physical asset, a monetary asset, a body of knowledge, a personal relationship, a certain skill and so on (Williamson 1975). In the financial industry, the reason that many consumers are reluctant to trust in m-payment services may rest on the specific assets they have invested in the procedural learning and payment software installing. The asset of procedural learning implies the time and effort associated with the process of initiating a relationship and acquiring the skills and know-how to use a new service effectively (Wang et al. 2012). For the first-time adopters of m-payment service, they need to spend time and effort learning the usage of m-payment. Also, using m-payment service requires the installation of specific software (e.g. payment mobile application) that is dedicated to a particular bank. Users may take into consideration the potential transaction costs resulting from investing in and/or redeploying the transaction-specific asset. The more assets a user invests in learning m-payment procedures and managing the payment software, the less trust he/she may build. Therefore, we assume that if users believe that the use of m-payment requires substantial specific asset investment, their initial trust in m-payment systems will be reduced. Therefore, the following hypothesis is tested in this study:

-

H5: Perceived asset specificity has a negative influence on initial trust.

3.6 Initial trust, revised TAM and usage intention

Trust is a subjective belief that a party will fulfil his or her obligations according to the expectations of the trusting party. It is crucial because gaining trust reduces fears and worries (Hwang and Lee 2012; Lu et al. 2011). According to the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen 1991), trust as a user belief may affect behavioral intention. Several trust researchers have shown a direct relationship between trust and willingness to buy online from internet vendors (Kim et al. 2008; Kim 2012; Bock et al. 2012). Compared to online and traditional transactions, transactions conducted in a mobile network are more vulnerable and uncertain and therefore entail greater potential risk. For example, mobile networks are vulnerable to information interception and hacker attack. Mobile terminals may be also infected by Trojan horses and viruses. These security problems will increase users’ perceived risk. Potential adopters need to build trust in order to mitigate perceived risk. Previous studies have validated the influence of customers’ trust on their behavioral intention in the mobile finances context (Xin et al. 2013). By examining innovative mobile adoption, Kim et al. (2010) demonstrate that customers’ perceptions of initial trust play a vital role in promoting their personal intention to use the services. Slade et al. (2014) and Zhou (2014) also indicate that trust in m-payment service providers is positively related to the usage intention. Thus, we suggest,

-

H6: Initial trust has a positive influence on usage intention.

In addition, we propose that initial trust will exert an indirect effect on usage intention via two influential variables: perceived benefit and perceived convenience. These two variables are derived from TAM. The TAM uses two distinct but interrelated beliefs - perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use - as the basis for predicting end-user acceptance of computer technology. Of the two TAM variables, studies have found perceived usefulness to have the stronger influence (Davis 1989). There has been a focus on these beliefs in previous studies of user acceptance and the adoption of a new IT technology (Chiou and Shen 2012; Gao et al. 2013; Liébana-Cabanillas et al. 2014). The classical definition of perceived usefulness by Davis (1989) is that the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system will enhance his or her job performance. This study highlights the aspects of perceived benefit and changes the original term to perceived benefit. This can be a significant conceptual shift from personal usefulness to a more direct benefit perception (Lee 2009).

We define perceived benefit as a user’s belief about the extent to which he or she will become better off from the m-payment service. It reflects the utility derived from using m-payment. In various settings, trust has been found to have a positive impact on perceived benefit. For instance, in a person-to-person setting, trust can increase an individual’s productivity and profitability (Liu et al. 2013). Similarly, in a person-to-organization setting, trust can reduce an organization’s overall operation costs. In particular, in the e-commerce setting, customers’ trust enhances an individual’s expected usefulness or performance of a product or service (Bock et al. 2012). Initial trust provides a guarantee that users will acquire future positive outcomes (Gefen et al. 2003). In other words, trust enables users to believe that service providers have enough ability and benevolence to provide useful services to them and they will receive the expected benefits from an exchange relationship. If a service provider cannot be trusted with regards to providing reliable m-payment service, potential adopters will be more likely to suffer a loss from using m-payment when the service provider behaves opportunistically. As a result, there is no reason for them to expect any benefits from using the m-payment services provided by that service provider. Moreover, several studies have found that perceived benefit has a positive effect on usage intention of new technology systems (Kim et al. 2008; Lin and Lu 2011; Lee 2009). We therefore hypothesized:

-

H7: Initial trust has a positive influence on perceived benefit.

-

H8: Perceived benefit has a positive influence on usage intention.

Perceived ease of use refers to the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system will be free of effort (Davis 1989). In this study, perceived ease of use is similar to the concept of convenience, which means any issues related to ease and comfort of use. Perceived convenience in m-payment can include ease handling, fast processing of the payment transaction, high number of accepting merchants, easy learnability of payment procedure, no installation of software on the mobile device, and no pre-registration necessary (Shin 2010). Following Shin’s (2010) concept, this study replaces perceived ease of use with perceived convenience. It is reasonable to assume that a potential adopter who has a high level of trust in m-payment services will perceive to a relatively high likelihood that using m-payment will provide them with a variety of convenience, such as conducting payment at anytime from anywhere, and requiring little mental effort. Prior studies have found that increasing trust improves the consumers’ perception of convenience related to e-commerce. Chiang and Dholakia (2003) also indicated that perceived convenience has a strong positive influence on usage intention. In the original TAM, perceived ease of use is found to positively affect perceived usefulness (Lee 2009). Similarly, we argue that perceived convenience of m-payment also positively influences user perceived benefits. Thus, this study tests the following hypotheses:

-

H9: Initial trust has a positive influence on perceived convenience.

-

H10: Perceived convenience has a positive influence on usage intention.

-

H11: Perceived convenience has a positive influence on perceived benefit.

4 Research methodology

4.1 Research context

The study was conducted in Australia which has one of the world’s most mature mobile phone markets, with a mobile phone penetration rate of over 135 % (Australian Communications and Media Authority 2013). Although m-payments are not a commonly accepted method, recent reports have showed that m-payments in Australia are on the rise (Chris 2014). Major Australian banks have made m-payment a priority tech initiative and are in various stages of rolling out technology that lets customers pay with their smartphones (Adam 2014). Many financial institutions, retailers and processors have provided m-payment services and expect to see m-payments become a tool to support competition (Flood et al. 2013). In addition, Australia also has a very high literacy rate of 99 % among residents aged 15 years and older (Central Intelligence Agency 2013). Due to these reasons, Australia provides an excellent context for testing our research problem.

4.2 Sampling and data collection

As the information required for this study was not available in the form of secondary data, so we collected primary data through a survey. We conducted our survey with the assistance of a professional online survey company in Australia. The online survey company electronically distributed the questionnaire to 10,500 members of the company’s panel via emails, inviting them to participate in the online survey. A brief explanation of this study was also provided in the opening instructions along with a definition of m-payment (e.g., checking balance, transferring money and conducting payment via mobile devices such as mobile phones). To encourage participation, participants were told that they had a 10 % chance of winning a prize by completing the survey. A reminder email was sent 1 week after the first one. 1155 responses were collected, which yielded a response rate of 11 %. In order to ensure the accuracy and validity of the survey results, we scrutinized all responses and dropped those from any respondent who: had too many missing values, had given the same answer for all questions; or had already had m-payment experience. As a result, we obtained 851 valid responses. Our sample size is sufficient to get reliable PLS results as it meets a generally accepted ‘10 times’ rule of thumb that defines the minimum sample size as 10 times the most complex relationships in the research model (Chin 1998). The most complex construct in the research model has eight predictors of initial trust, necessitating a minimum respondent sample size of 80.

We also conducted the non-response bias test. It did not appear to be a major concern as we found no significant differences between those participants who responded early and those who responded late with respect to key measures. Following the procedures suggested by Armstrong and Overton (1977), we found that chi-square tests show no significant differences between those participants who responded early and those who responded late with respect to key measures at the 5 % significance level. Therefore, we believe that non-response bias did not appear to be a major concern. The demographic details of the respondents are summarized in Table 1.

4.3 Measurement development

An initial pool of items was created from a review of the existing literature on technology acceptance. Most items were taken from the previous literature with modifications to fit the context of m-payment. The remaining items were developed through proposed definitions of the constructs, focus groups, and personal interviews with m-payment users and the mobile commerce researchers and managers.

Specifically, items of perceived system quality, perceived information quality and perceived service quality were adapted from Kim et al. (2010). Items of perceived system quality reflect the access speed, ease-of-use, navigation and visual appeal. Items of perceived information quality reflect information relevance, sufficiency, accuracy and timeliness. Items of perceived service quality reflect reliability, responsiveness, assurance and personalization. The items measuring perceived uncertainty were adapted from prior studies’ security risk instruments (Wang et al. 2012; Chiou and Shen 2012). Since asset specificity is context-relevant, potential measures of perceived asset specificity were developed by following the format of previous studies (Teo et al. 2004; Liang and Huang 1998) that investigated B2C transactions. The study proposes that a multi-dimension trust (i.e., ability, integrity and benevolence) is better than a single dimension of trust. Three dimensions of initial trust were adapted from previous studies and some items were designed especially for this study. The scale for perceived ability is based on items referring to whether or not potential users perceive the m-payment service providers as possessing necessary domain-specific skills and its continuous availability of the service (Bhattacherjee 2002; David Gefen 2002; Yousafzai et al. 2009). The perceived integrity scale is based on items that refer to potential users’ perception of the m-payment service providers’ adherence to fair rules of conducting transactions, consistency in m-payment’s actions and policies, and the perception that m-payment will continue its commitment to provide reliable services (McKnight et al. 2002; Kim et al. 2009a, b, c). The operationalization of perceived benevolence is based on items that refer to whether or not the m-payment demonstrates empathy and reception towards users’ concerns and its interest in the users’ well-being (Gefen 2002; McKnight et al. 2002; Yousafzai et al. 2009). The measures of perceived benefit and perceived convenience were adapted from previous studies relating to the TAM model, mainly from Lee (2009) and Kim et al. (2010). Items of usage intention were taken from Kim et al. (2010) to measure user intention to use m-payment. All item scales were measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale with anchors of strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (7).

These items were then screened by m-payment scholars who were asked to clarify them and then comment on whether the items were likely to be appropriate for evaluating the adoption behavior in the m-payment context. Five experts in m-payment businesses were asked to indicate whether any of these measurement items needed to be refined. We developed a questionnaire in English, which was then translated into Chinese by four researchers who were proficient in both the English and Chinese languages. To verify the accuracy of the translation, the questionnaire was then translated back to English by four native Australians who were proficient in both English and Chinese. The two versions were compared through mean difference test and certain discrepancies were addressed. During this process, the researchers tried to ensure consistency between the Chinese and the English versions of the survey.

A pretest was conducted by establishing two groups that each consisted of 40 respondents. Each group was composed of individuals who had experience with m-commerce and m-payment. Based on the pretest, some items were reworded, eliminated, or clarified because they were deemed inappropriate, unnecessary, or ambiguous. We eventually selected 44 items based on the results of the above procedures, and these items represented various aspects of individuals’ perception of the m-payment. The final scale is attached in the Appendix.

Several control variables were incorporated to enhance the robustness of the findings. Prior studies have shown that demographics variables such as gender and age play a significant impact on customer acceptance of technology (Venkatesh et al. 2003). Therefore, we suppose gender, age, income and education may have influence on intention to use m-payment. As studies have shown that mobile internet experience plays a major role in the internet environment in relation to usage behavior (Chandra et al. 2010), this study also controls for the role of mobile internet experience on usage intention.

5 Data analysis

Partial Least Squares (PLS), a component-based structural equation modeling (SEM) technique, was employed to examine our measurement model and test the proposed hypotheses. There are several reasons to use the PLS technique. First, PLS has less strict requirements on sample size and residual distributions than covariance-based SEM techniques such as Lisrel and AMOS (Chin et al. 2003). Second, statistical identification with formative models is difficult for covariance-based SEM techniques but is not an issue for PLS (Petter et al. 2007). In this study, initial trust is treated as a second-order formative construct instead of being a reflective construct as in the study by Lu et al. (2011). Here, formative representation is preferred over reflective because the increase in one trust dimension such as perceived ability does not necessarily cause an increase in other types of trust (e.g. perceived integrity, perceived benevolence). Third, PLS is well-suited for studies in the early stage of theory building and testing (Jöreskog and Wold 1982). Thus the PLS technique is well-suited for our research context, as the adoption of m-payment is still largely unexplored or under-explored research area. Fourth, PLS is especially capable of testing large, complex models with latent variables and is virtually without competition (Wold 1985). Our research model is fairly large and complex, including a large number of variables and both reflective and formative constructs. Therefore, PLS is considered more appropriate for this study than covariance-based SEM techniques.

The following subsections describe a two-stage approach to test our measurement model and research hypotheses. Before testing our hypotheses, we first demonstrate the soundness of our measurement by examining the second-order factor, the CFA results, and the issue of common methods variance.

5.1 Test for second-order factor

Second-order factors can be approximated using multiple approaches (Chin et al. 2003). One commonly-used approach is the repeated indicator approach, also known as the hierarchical component model (Lohmöller 1989). A second-order factor is directly measured by using items of all its lower-order factors. The repeated indicator procedure works best when the lower-order constructs have about equal numbers of indicators. The second commonly-used approach is to model the paths between lower-order and higher-order factors (Edwards 2001). In PLS, this approach is implemented by measuring a second-order factor using the scores of its first-order factors. In this study, we used the latter approach because the three dimensions of initial trust have different numbers of indicators, ranging from three to five. The measurement quality of the formative second-order factors was tested following the suggestions by Chin (1998). We first examined the correlations among the three first-order initial trust. The absolute correlations among these three first-order factors vary from 0.18 to 0.24 and the average is 0.22. This result suggests that initial trust is better represented as a formative second-order factor instead of a reflective one since a reflective second-order construct would show extremely high correlations among its first-order factors (often above 0.8) (Pavlou and Sawy 2006). We further assessed the strength of the relationship between initial trust and its three first-order trust dimensions. All first-order trust dimensions were found to have significant path coefficients (or PLS weights) (Fig. 2). The variance inflation factor (VIF) was then computed for these first-order trust factors to assess multicollinearity. VIF values above 10 would suggest the existence of excessive multicollinearity and raise doubts about the validity of the formative measurement (Chin 1998). The VIF values varied from 1.3 to 3.2 for these three first-order factors. Therefore, multicollinearity is not a concern in this study.

5.2 Measurement model

All first-order factors in our research model are reflective constructs. The measurement quality of these reflective instruments was assessed based on their internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Internal consistency reliability was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE). As shown in Table 2, the Cronbach’s alphas were all greater than 0.8; the composite reliability exceeded 0.8, and the AVE were at least 0.7. Considering the acceptable threshold values for Cronbach’s alpha, CR, and AVE, 0.7, 0.7, and 0.5, respectively, the values obtained suggest adequate internal consistency reliability and convergent validity.

To test the discriminant validity, we compared the square root of the AVE of each first-order construct and its correlation coefficients with other constructs. Table 3 shows that the square roots of the AVEs were larger than their corresponding correlation coefficients, indicating acceptable discriminant validity.

As self-reported data from a single source were used, we performed three statistical analyses to assess the possible severity of common method variance (CMV). First, a Harmon’s single-factor test (Podsakoff et al. 2003) was conducted, which reveals that no single factor accounted for the majority of the variance (the first factor accounted for 21.6 % of the 68.8 % explained variance). Second, following the procedure used by Liang et al. (2007), a new measurement model with all indicators loading on a common method factor was constructed and compared with the original measurement. The results of the statistical analyses demonstrated that the principal variable loadings were all significant at the p < 0.001 level, while the common method factor loadings were not significant. Third, the marker variable technique recommended by Lindell and Whitney (2001) was undertaken. Within this technique, a variable that has a small correlation with the endogenous construct is identified as a marker variable. This correlation is then used to partial out the effect from other correlations to examine the degree of any CMV that may be present. As suggested by Lindell and Whitney (2001), we also conducted a sensitivity analysis at 95 and 99 % levels of confidence for the correlations of the marker variable. Satisfaction with life was used as the marker variable; this measure has been suggested as a suitable marker variable for detecting CMV (O'Cass and Sok 2012, 2014). After conducting the marker test, we did not detect any statistically significant correlation between the marker variable and the other latent variables, and the correlation coefficient was so small that it could not have significantly influenced the tested hypotheses. All three tests confirm that CMV is not a major concern in our study.

5.3 Structural model and hypotheses testing

The results of hypothesis testing using PLS are summarized in Fig. 3. Most of the hypotheses were supported, except H5. Specifically, the three components of positive valence (i.e. perceived system quality, perceived information quality, and perceived service quality) all had strong positive effects on initial trust (β = 0.368, p < 0.001; β = 0.547, p < 0.001; β = 0.547, p < 0.01; respectively). Thus, H1, H2, and H3 were supported. Only one of the components of the negative valence (i.e. perceived uncertainty) had a significant negative influence on initial trust (β = −0.446, p < 0.001), meaning that H4 was supported. The result did not find significant effect of perceived asset specificity on initial trust (β = −0.023, p > 0.05), therefore rejecting H5. The three hypothesized paths on the effects of initial trust to usage intention (β = 0.469, p < 0.001), perceived benefit (β = 0.335, p < 0.001), perceived convenience (β = 0.297, p < 0.001) were all significant, supporting H6, H7 and H9. The hypothesized paths from perceived benefit (β = 0.372, p < 0.001) and perceived convenience (β = 0.101, p < 0.05) to initial trust was significant. Thus, H8 and H10 were confirmed. Perceived convenience was found to have a significant positive effect on perceived benefit (β = 0.431, p < 0.001), supporting H11.

Overall, the results show that the research model can explain 65.6 % of variance in initial trust, 13.8 % of variance in perceived convenience, 24.5 % of variance in perceived benefit, and 52.3 % of variance in usage intention. The control variables were also modeled as one-item constructs with zero error variance. The path coefficients indicated that users’ gender, age, education and mobile internet experience do not have a significant effect on usage intention.

6 Discussion and conclusion

6.1 Key findings

The current study aims to propose an initial trust theoretical model for user adoption of m-payment and further explore the initial trust facilitators and inhibitors by integrating the valence framework, ISS model and TCE model. The findings of this study provide several important implications for m-payment adoption research and practice.

The results show that information quality is positively related to initial trust. This is consistent with Zhou (2011b), which asserts that information quality positively affect initial trust in mobile banking. Similarly, in the context of mobile shopping, Yang (2015) has reported that information quality is positively associated with initial trust. Among the factors facilitating initial trust formation, information quality has the largest effect, which is a new finding in the area of online and mobile commerce research. In an online setting, many studies have indicated that information quality is positively related to consumer trust in online vendors (D. J. Kim et al. 2008). It is well recognized that information on the internet varies a great deal in quality, ranging from highly accurate and reliable, to inaccurate and unreliable, to intentionally misleading. It is also often very difficult to tell how frequently the information on websites is updated and whether the facts have been checked or not (Bock et al. 2012). Thus, consumers on the internet are likely to be particularly attentive to the quality of information on a website because the quality of information should help them make good purchasing decisions (Zheng et al. 2013; Pearson et al. 2012). Similarly, in the m-payment setting, users are concerned about the information quality. To conduct m-payment, they need to obtain accurate, relevant and up-to-date information. Acquiring and processing high quality information are critical activities for m-payment users (Zhou 2014). As users perceive that the m-payment presents quality information, they will perceive that the m-payment service provider is interested in maintaining the accuracy and currency of information, and therefore will be more inclined, and in a better position, to fulfil its obligations. To the extent that users perceive that a m-payment service provider resents quality information, they are more likely to have confidence that the service provider is reliable, and therefore will perceive the m-payment as trustworthy. On the other hand, if this information is inaccurate or out-of-date, users may feel annoyed and lack of control (Slade et al. 2014). This will undermine the service provider’s trustworthiness. For example, m-payment accounts need to be synchronized with online payment accounts. Otherwise, when users have actually made an online payment, they may get inaccurate information on account balance by inquiring with m-payment. In addition, it is relatively difficult for users to search for information on mobile internet. Thus, service providers should present the information relevant to user demand. This may help users build initial trust.

The study provides further theoretical support of the role of system quality in initial trust building. Users expect to conduct payment via m-payment at anytime from anywhere. Thus the low quality system will decrease their evaluation on the reliability and trustworthiness of m-payment (Yan and Yang 2015). For example, if m-payment has a slow access speed, users may need to wait a long time for the response. They may also encounter service unavailability or interruption because of the unreliable system. These problems will lower users’ initial trust in m-payment. Thus m-payment service providers need to enhance their back-end systems and ensure the reliable and stable systems are offered to users. Especially, as mobile devices have small screens and inconvenient input, mobile service providers need to present users with a well-designed interface, including clear layout, powerful navigation and visually appealing interface (Mostafa 2015; Kapoor et al. 2014). Otherwise, users may feel difficult and bored to use m-payment. This will trigger users to doubt the service provider’s ability and benevolence to provide a quality system, and will consequently reduce their initial trust in m-payment. In addition, users often need to download, install and configure the relevant software according to their mobile phone type before they can use m-payment for the first time. This process may be complex for initial users. M-payment service providers can provide online tutorials and help to users. This may signal service providers’ ability to understand user needs and will help build user initial trust in m-payment system. Furthermore, m-payment systems need to be better integrated with existing financial and telecommunication infrastructures. This is because proprietary systems with exclusive service providers and infrastructures are not likely to succeed in the long term.

In addition to information quality and system quality, service quality was also found to have a positive effect on initial trust although its effect is relatively small. This finding concurs with Yang (2015) in the mobile shopping setting. Due to the non-face-to-face wireless payment environment, users are concerned about the service quality of m-payment (Zhou 2015). If service providers cannot ensure service reliability, promptness and personalization, users may doubt service providers' ability and integrity to present quality m-payment services to them, which will decrease their trust. Service providers can adopt encryption and certificates to ensure m-payment security and reliability. Otherwise, users may perceive great risk and low initial trust, and may drop their usage of m-payment. In addition, they can present personalized services to users. For example, they can use location-based services to acquire user location. Then they push context-related information such as nearby banks and automated teller machines to the user. This personalized service may help increase user trust (Zhou 2011a). The study further indicates that compared to other initial trust facilitators, service quality has a relatively low effect on initial trust. This can be explained by the fact that our study focuses on the first interaction between users and m-payment. Due to the lack of previous direct experience, it would be difficult or impossible for users to evaluate the service quality offered by the m-payment for the first time, instead, they would rely on more straightforward cues such as the information presented to them and the system quality to assess the trustworthiness of m-payment as these cues are easier to perceive and act as strong signals based on which users can form their initial trust (Yan and Yang 2015). Evaluation of service quality requires more time and effort and usually takes place when users continually interact with m-payment systems and service providers. Thus, it displays the least effect on initial trust at the first interaction with m-payment.