Abstract

School-to-work transition is a crucial period in the life of young adults, when they begin to realise their career aspirations. Yet, only a few young Ghanaian graduates find jobs one year after completing school. Understanding job search behaviour of graduates in Ghana would require a valid and reliable measure. This study evaluated the psychometric properties of the Job Search Behaviour Index (JSBI) using Rasch analysis. Data were from 429 recent graduates. Rasch analysis showed that the JSBI-7 was unidimensional and locally independent. There was no noticeable differential item functioning across gender. JSBI-7 is a promising measure for use in Ghana.

Résumé

Propriétés psychométriques de l'indice de comportement de recherche d'emploi (JSBI) chez les jeunes diplômés universitaires : Une analyse de Rasch Le passage de l'école au travail est une période cruciale dans la vie des jeunes, où ils commencent à réaliser leurs aspirations professionnelles. Pourtant, seuls quelques jeunes diplômés ghanéens trouvent un emploi un an après avoir terminé leurs études. Pour comprendre le comportement de recherche d'emploi des diplômés au Ghana, il faudrait disposer d'une mesure valide et fiable. Cette étude a évalué les propriétés psychométriques du Job Search Behaviour Index (JSBI) en utilisant l'analyse de Rasch. Les données proviennent de 429 jeunes diplômés. L'analyse de Rasch a montré que le JSBI-7 était unidimensionnel et localement indépendant. Il n'y avait pas de différence notable dans le fonctionnement des items selon le sexe. Le JSBI-7 est une mesure prometteuse pour une utilisation au Ghana.

Zusammenfassung

Psychometrische Eigenschaften des Job Search Behaviour Index (JSBI) bei jungen Hochschulabsolventen: Eine Rasch-Analyse Der Übergang von der Schule in den Beruf ist eine entscheidende Phase im Leben junger Menschen, in der sie beginnen, ihre Berufswünsche zu verwirklichen. Dennoch finden nur wenige junge ghanaische Hochschulabsolventen ein Jahr nach ihrem Schulabschluss einen Arbeitsplatz. Um das Stellensuchverhalten von Hochschulabsolventen in Ghana zu verstehen, wäre ein valides und zuverlässiges Maß erforderlich. In dieser Studie wurden die psychometrischen Eigenschaften des Job Search Behaviour Index (JSBI) mittels Rasch-Analyse evaluiert. Die Daten stammten von 429 Hochschulabsolventen. Die Rasch-Analyse zeigte, dass der JSBI-7 eindimensional und lokal unabhängig war. Es gab keine auffälligen Unterschiede in der Funktionsweise der Items zwischen den Geschlechtern. JSBI-7 ist ein vielversprechendes Maß für den Einsatz in Ghana.

Resumen

Propiedades psicométricas del Índice de Comportamiento de Búsqueda de Empleo (JSBI) en graduados universitarios recientes: Un análisis de Rasch La transición de la escuela al trabajo es un periodo crucial en la vida de los jóvenes, cuando empiezan a hacer realidad sus aspiraciones profesionales. Sin embargo, sólo unos pocos jóvenes graduados en Ghana encuentran trabajo un año después de terminar sus estudios. Para entender el comportamiento de búsqueda de empleo de los graduados en Ghana se necesita una medida válida y fiable. Este estudio evaluó las propiedades psicométricas del Índice de Comportamiento de Búsqueda de Empleo (JSBI) utilizando el análisis de Rasch. Los datos se obtuvieron de 429 graduados recientes. El análisis de Rasch mostró que el JSBI-7 es unidimensional y localmente independiente. No se observó un funcionamiento diferencial de los ítems en función del género. El JSBI-7 es una medida prometedora para su uso en Ghana.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The transition from school to work is a crucial period in the life of young adults worldwide (Koen et al., 2012; Matsumoto & Elder, 2010; Saks, 2018). This is the period they begin to realise their career aspirations, start to make effective use of their skills, strive to earn a fair income to cater for themselves and their families, and negotiate the transition from dependence on parents to independence (United Nations Children’s Fund, 2019a). The transition from school to a first job can have long-term effects on a young adult’s career path and economic independence (Ryan, 2001). For instance, a smooth school-to-work transition can facilitate young adult’s early entry into the labour market to contribute to the evolving economy.

However, there is growing concern about the school-to-work transition (see International Labour Organisation [ILO], 2020), described as the period between graduation from compulsory schooling and finding stable employment (see Grosemans et al., 2017; OECD, 1998, 1999; United Nations Children’s Fund, 2019b), among young adults in Ghana (see Affum-Osei et al., 2019; Odame et al., 2021). This concern arises because even though Ghana’s young graduate cohorts (also known as digital natives, Generation Y, and Millennials) seem to be better educated than their older counterparts, graduate unemployment rates remain high. For example, recent reports indicated that only 10% of Ghanaian university graduates found jobs a year after completing school (see Ghana News Agency, 2017; Yeboah, 2019).

According to the Ghana Statistical Service (2016), only 38.9%Footnote 1 of all young people aged 15–24 years were employed in 2015. This number includes those in vulnerable employment, defined as employees that lack formal work contracts and other decent employment packages (see Aryeetey & Baah-Boateng, 2016). The Ghana Statistical Service’s Report further showed that using the ILO’s three stages of the school-to-work transition criteria (i.e. [a] transited, [b] in-transition, and [c] transition not yet started; [see International Labour Organisation, 2019]), only 27.9% of young Ghanaians aged 15–24 years had successfully transited in 2015. Correspondingly, the World Bank (2020a) and observed that, most young graduates in Ghana do not make the transition from school to stable employment several years after leaving school (see also Suuk, 2016). They reported that Ghana’s youth unemployment rate is twice as high as the total unemployment rate in Ghana (see Ghana Statistical Service, 2016). For instance, they found that about 50% of young Ghanaians were in vulnerable employment (i.e. underemployed) in 2015.

Moreover, Aryeetey and Baah-Boateng (2016) reported that young people with university education in Ghana tended to experience higher unemployment rate compared with their counterparts with only secondary education. Aryeetey and Baah-Boateng (2016) observed that because most young adults with primary education or no formal education take up vulnerable employment opportunities in the informal sector, the unemployment rate seemed to be lowest among them. The advent of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic worsened the unemployment problem in Ghana because the pandemic and its associated lockdowns forced Ghanaian businesses to reduce wages for over 770,000 workers, and caused about 42,000 layoffs within the first two months of the pandemic (see Aduhene & Osei-Assibey, 2021; Schotte et al., 2021; World Bank, 2020b). Consequently, as young Ghanaians get older, the opportunity to earn a decent living to care for themselves and for their families may remain a challenge. They may also experience poor mental health outcomes (see McKee-Ryan et al., 2005; Paul & Moser, 2009). A related problem is that Ghana has a fast growing youth population and Ghana’s labour market rarely offers hourly rate pay policy to enable in-school youth to combine schooling with part-time work, which could provide them with useful work experience while in school.

A variety of factors has been blamed for the high rate of graduate unemployment in Ghana, including the claim that skills acquired in higher education fall short of labour market requirements (see Baah-Boateng, 2015; Damoah et al., 2021; Nwokolo, 2019) and inadequate job opportunities for young adults (Bugri, 2020). However, little research efforts have been directed at finding out how young adults in Ghana search for jobs. For example, higher education institutions in Ghana rarely conduct reflective tracer studies on the employment experiences of their graduates (see Nudzor & Ansah, 2020). Thus, it remains unclear how university graduates in Ghana search for jobs, following completion of compulsory school. From the foregoing, it seems clear that this is a research goal whose time has come, given the rising youth unemployment rate. This research is needed to answer the question: How do Ghanaian university graduates search for jobs? Understanding the job search behaviour of university graduates transitioning to the labour market in Ghana would provide important information to guide policy, research, and skills training. Meta-analytic work has shown that active job search behaviour is positively associated with finding stable employment (see Kanfer et al., 2001).

To appropriately assess the job search behaviour of young Ghanaian job seekers, we would require a valid and reliable measurement tool. Unfortunately, to our knowledge, there are no Ghanaian measurement tools developed to assess graduate students’ job search strategies. Because the transition from school to work is not an automatic process, but one that is partly determined by the job search strategy used, it would seem necessary to have a career assessment measure to achieve such objectives. For instance, the method of job search and the effort that graduates put into job search may determine how early they make the transition from school to work.

In Ghana, career counselling for university students is mostly undertaken by professionals at Career and Placement Centres at universities. At these Centres, career counselling usually takes the form of general career fair or career seminar for a large number of students at a few time points during the academic life of students. The career seminars are not targeted at the specific need of the individual student. Also, students are rarely trained in the use of psychometric tests and personality tests as part of the career counselling process. From the foregoing, there seems to be an urgent need for a job search measure that is applicable to the context of Ghana for use among young adult job seekers. A job search measure validated for Ghana may be used by career counselling professionals at universities to assess the job search strategies of outgoing university graduates.

It might be useful to develop a new scale that is context driven to fill this lacuna in the Ghanaian job search literature. However, doing so would not only be time consuming but also require research funding (which may take time to secure). It has been shown that cross-cultural validation of existing measurement tools can enhance the reproducibility of science (Earp & Trafimow, 2015; Hawkins et al., 2018). From the foregoing, we elected to validate an existing scale (i.e. Job Search Behaviour Index [JSBI]) for use in the Ghanaian context. The JSBI is a brief measure with simple items that can be easily understood by young Ghanaians, without the need for translation. Besides, the scale items reflect most of the activities young Ghanaians who need a job would be expected to do, indicating the scale’s potential for achieving ecological validity. That is, the scale’s test scores can predict real job search behaviour of young adults in Ghana. The JSBI is a 10-item scale developed by Kopelman et al. (1992) as part of a major study. It assesses most of the specific actions a job seeker might be expected to undertake during the job search process. The specific actions are thought to translate a potential job seeker’s intentions to outcomes. These actions, when taken by young graduates in Ghana during the job search process, may facilitate their school-to-work transition. The JSBI can be used for assessing job search behaviour in diverse populations and age groups in Ghana.

Nevertheless, a major limitation of the JSBI is that the authors did not report on its factor structure, warranting further evaluation of its factor structure in the present study. In addition, we were unable to find any validity information on the JSBI in the literature. A probable reason for this is that the scale was developed as part of general study so the original authors had placed emphasis on the main findings of the study but not the development of the scale. Evaluating the factor structure of the JSBI measure is important for various reasons. First, the scale’s test scores in Ghana would provide useful validity information on its underlying putative structure. Second, knowledge of the JSBI’s factorial validity in Ghana can guide researchers to know which statistical tests to use and which items to combine into a unitary construct. Third, this knowledge may determine which new research questions to pursue in future research with the scale. In addition, the JSBI was developed using classical test theory (CTT). CTT is a psychometric technique based on the observed score decomposition (see Raykov & Marcoulides, 2015). In other words, within the CTT approach, an observed score is composed of the underlying true score and an error score. Despite widely being used, there are a few limitations associated with the CTT (see Chang et al., 2015; Embretson & Reise, 2000; Hobart et al., 2007; Raykov & Marcoulides, 2011). Some of these limitations include the assumption that, compared with shorter tests, longer tests are more reliable (Chang et al., 2015; Embretson & Reise, 2000). Since the development of the JSBI, there have been remarkable advances in psychometric theory and practice, including the development of advanced statistical software. Thus, there is the need for further validity evidence for the JSBI from modern test theory.

To build on Kopelman et al.’s (1992) work, the present study used item response theory (IRT) with Rasch analysis to assess the JSBI’s structural validity. The Rasch model can evaluate how individuals at different levels of the JSBI construct perform on the items aimed at measuring its underlying latent construct (Raykov & Marcoulides, 2011). Rasch models also have the ability to ensure that measures of objects are independent of the attributes of the agents used to estimate the measures (Aryadoust et al., 2019; Boone, 2016; Boone & Noltemeyer, 2017). Rasch models have been shown to have the capability to transform polytomous, ordinal scale data into linear, interval scale data (see Andrich & Marais, 2019; Bond & Fox, 2015). Taken together, Rasch measurement can provide sound psychometric assessment of the JSBI. Overall, the aim of the present study was to validate the JSBI for use among young Ghanaian job seekers. The following research questions guided the present study: (a) What is the factor structure of the JSBI? (b) Are the items of the JSBI valid and reliable? (c) How does the JSBI’s rating scale function? (d) Can scores on the JSBI be meaningfully compared across males and females?

Method

Participants

A cross-sectional design was used in this study. Data were provided by 429 (male = 215, female = 214) recent university graduates (Mage = 24.11, SDage = 2.80) as part of the School-to-Work Transition (SWoT) study. The SWoT study aimed at validating selected job search and career interest measures. Participants were National Service personnel. National Service (known as “military service” in some countries) is undertaken by graduates from accredited tertiary institutions in Ghana. They are required by law to perform a one-year mandatory service to the people of Ghana in various work roles in both public and private organisations, following the completion of school (see the National Service Scheme’s website at https://nss.gov.gh/about-us/). Participants were recruited at corporate, educational, and health institutions in the Greater Accra Region, Ghana through convenience sampling. Of the 480 participants invited to participate in the study, 429 provided full data indicating a response rate of 89.4%. They completed a paper-and-pencil questionnaire in English Language. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Ghana (Ref#: ECH116/19–20).

Measure

Job search behaviour was assessed with the Job Search Behaviour Index (JSBI) developed by Kopelman et al. (1992). The JSBI is a10-item self-report measure that assesses specific overt behaviours a job seeker might be logically expected to engage in during the job search process. All of the ten items are positively worded and responses are based on participants’ job search activities over the past one year. The JSBI was developed in the United States using three samples: graduate students (Cronbach’s α = 0.78), nurses (Cronbach’s α = 0.76), and college alumni (Cronbach’s α = 0.77). The JSBI was originally rated on a scale from 1 (yes) to 0 (no). However, the response scale was modified for the present study. The modification was motivated by the fact that the Likert format response scale would offer a more precise measure of the frequency of each job search activity undertaken, compared to a “yes/no” response that would elicit an exact response, which response some participants may have difficulty recalling. In this study all of the 10 items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (never [0 times]) to 5 (very frequently [10 or more times]). All of the 10 items on the JSBI are positively keyed. Participants’ job search activities over the past six months, during which time most National Service personnel should engage in preparatory job search behaviours for a permanent job, were assessed. Study participants provided demographic information on age (years) and gender. Table 1 lists the 10 items of the JSBI.

Statistical analysis

Preliminary analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed to understand the characteristics of the participants as well as distribution of scores on the JSBI. Skewness and kurtosis were determined using the cut-off index of ± 2 (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). All of the items were normally distributed. Following this, descriptive statistics were calculated. Four items had a missing data point. There were no floor or ceiling effects. Floor or ceiling effects were deemed to be present in the data if > 15% of participants obtained the lowest or highest score. Next, we used exploratory factor analysis (EFA), parallel analysis, and the Scree test to determine the factor structure of the JSBI-10. As recommended by Carpenter (2018), Maximum Likelihood and Direct Oblimin were used for factor extraction and factor rotation, respectively. Items were retained if they loaded > 0.40 (Field, 2018).

The EFA extracted two factors, using Kaiser’s eigenvalues > 1 rule. Factor one loaded positively on seven items, and factor two loaded negatively on the remaining three items. Because all of the ten items were positively keyed, we decided to reverse score the 3 items and to re-run the EFA. The reanalysis showed that all of the three items still loaded in the negative direction, reflecting an inverse correlation between the factor and the items. Given that various researchers have suggested that the eigenvalue rule rarely results in stable factors (see Carpenter, 2018; MacCallum et al, 1999; Raubenheimer, 2004; Worthington, & Whittaker, 2006), we performed parallel analysis and supplemented the results with the Scree plot. We compared the eigenvalues obtained from the EFA with those randomly produced from the parallel analysis. The results demonstrated that a single factor solution was optimal. Note that a factor is retained when its eigenvalue in the EFA is larger than the eigenvalue obtained from the random data set in Monte Carlo parallel analysis.

Based on the parallel analysis and Scree plot, we removed the problematic items from subsequent analysis. Another reason for removing the three items was that we considered them not to be measuring the intended latent construct, and that they reflected measurement error. For ease of interpretation of the latent construct, we eliminated them from the analysis. Following this, we re-ran the EFA and found that the remaining seven JSBI items (hereafter called JSBI-7) produced a single factor solutionFootnote 2 with a simple structure. The factor loadings are presented in Table 4***. Descriptive analysis and exploratory factor analysis were conducted in SPSS (IBM SPSS® Statistics v25.0, 2017) and Monte Carlo PCA for parallel analysis (Watkins, 2000).

Main analysis

The Rasch rating scale model (RSM; Andrich, 1978, 2011; Rasch, 1960) was used to evaluate the psychometric properties of the JSBI-7. Following Smith and Plackner (2009), who recommended that multiple fit statistics be used to evaluate data-model fit, this study used various fit statistics to assess the full functioning (item analysis) of the JSBI-7. First, infit and outfit mean-squared (MnSq) values > 0.6 but < 1.4 were used to assess how well the data fit the Rasch model (see Boone et al., 2014; Linacre, 2020). According to Linacre (2020) and Aryadoust et al. (2020), items with infit and outfit MnSq values outside of this range (i.e. values > 0.6 but < 1.4) are considered misfitting items.Footnote 3 Next, the Rasch person and item reliabilities and separation indices were examined. Person and item reliabilities are interpreted much like Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Person and item reliabilities > 0.7 are considered acceptable (see Boone & Noltemeyer, 2017). A person separation index > 1.50 and item separation index > 2.00 are considered satisfactory (Bond & Fox, 2015; Chang et al., 2014). Following this, the rating scale (i.e. threshold ordering) for the JSBI-7 was investigated. Rasch measurement requires that the rating scale for each item be ordered relative to their difficulty. That is, the rating category “never [0 times]” should be relatively easier to agree with than the rating category “rarely [1 to 2 times]” (see de Bruin et al., 2013). Response category functioning was evaluated using average measures, step measures, category probability curves, and infit and outfit MnSq values < 2.0 (Boone et al., 2014).

Further, construct unidimensionality of the JSBI-7 was evaluated using Rasch based principal component analysis of model residuals (PCA-R). Test unidimensionality is a key requirement in Rasch measurement (Hattie, 2015; Khine, 2020). In this study, the scale was considered unidimensional if > 50% of total variance in JSBI-7 was explained by the Rasch dimension with the eigenvalue of the first contrast/first secondary dimension being < 2.0 (see Bravini et al., 2016; Chang et al., 2016; Linacre, 1998a, 1998b; Raîche, 2005; Smith, 2002). According to Linacre (1998a, 1998b), for a secondary dimension to emerge from the residuals and be considered meaningful, it must have the strength of a minimum of three items. Therefore, an eigenvalue of less than or equal to 2.0 suggests that there are only 2-item strengths or less trying to load onto a factor/dimension. Previous work has shown that extracting factors with fewer than three items is not optimal (Carpenter, 2018; MacCallum et al., 1999; Raubenheimer, 2004; Worthington, & Whittaker, 2006).

In addition, local independence of the items (see Edwards et al., 2018) was assessed using residual correlation values between any two item pairs of (r < 0.30; Linacre, 2020; Røe, Damsgård et al., 2014; Testa et al., 2019; Zhong,et al., 2014). Locally independent items indicate that respondents’ answer to one item on the scale is independent of their answer to another item on the scale (Christensen et al., 2017; Debelak & Koller, 2020; Lambert et al., 2013).

Finally, uniform differential item functioning (DIF) analysis was conducted across gender to determine if the items functioned differently for males and females (see Hagquist & Andrich, 2017; Jones, 2019). Literature suggests that there are differences in job search behaviour of men and women and that the labour market is not gender neutral. For instance, Eriksson and Lagerström (2012) reported that women tend to look for employment near their places of abode, whereas men tend to look for jobs farther away from home. Examining whether men and women would respond to the scale items and the latent factor in the same way may provide opportunities for meaningful comparison of scale scores. The size of DIF using DIF contrast > 0.5 logits and cumulative log-odds ratio (CUMLOR) of ≤ 0.43 logits, and DIF statistical significance (p < 0.05) using Mantel statistic for polytomous data (Souza et al., 2017; Woudstra et al., 2019) were used to determine DIF. Rasch analysis was performed using WINSTEPS® (v4.4.2; Linacre, 2019).

Results

EFA model

Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy was 0.897 and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was, χ2(21) = 1214.86, p < 0.001, suggesting that the data were suitable for common factor analysis. The Determinant of the correlation matrix was 0.057, far greater than the minimum recommended value of 0.0001. Note that a Determinant value greater than the minimum threshold value of 0.0001 indicates the absence of multicollinearity and singularity in the data. All items loaded above the recommended loading criterion of (r > 0.40) on the factor (see Table 4***). The single factor model explained a total of 56.35% of the variance in the latent construct. Coefficient α = 0.869, 95% confidence interval (CI) [0.848, 0.886] and coefficient ω = 0.871, 95% CI [0.852, 0.890] for the JSBI-7.

Rasch model

Unidimensionality and local independence

Rasch principal component analysis of standardised residuals (PCA-R) provided further evidence to support the unidimensionality of the JSBI-7. The Rasch dimension accounted for 52.4% of the variance in JSBI-7, whereas the first contrast of the unexplained variance had an eigenvalue of 1.54, consistent with the acceptable cut-off criterion < 2.0. Moreover, inspection of the item residual correlations revealed that the items were locally independent of each other. The item pair correlations ranged between r = − 0.27 and r = − 0.01.

Differential item functioning

Uniform DIF analysis showed that there was no noticeable DIF across gender (men vs. women) in the data, supporting the stability of the items (see Table 2).

Rating Scale Functioning

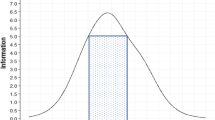

Rasch assessment of the functioning of the 5-point rating scale of the JSBI-7 (i.e. 1 (never [0 times]) to 5 (Very frequently [10 or more times]) showed that the average measures and category thresholds increased monotonically with each response category (see Table 3). Further, the category probability curves (see Figures 1, 2, and 3) confirmed that the thresholds were appropriately ordered, with each response category having a point on the trait continuum where they have the greatest likelihood of endorsement.

Test information function for the JSBI displays information along the latent trait continuum. The curve shows that the JSBI yields most information between approximately − 2.25 and + 2.25 logits (see rectangle). Approximately 90% of the person measures fell within the rectangle area, which indicates that the JSBI yields sensitive measures for most of the participants. JSBI job search behaviour index

Data-model fit

Evaluation of the fit of the JSBI-7 data to the Rasch model showed that all of the items fitted the Rasch model well. The data-model fit statistics are presented in Table 4. As can be seen in Table 4, all of the infit MnSq values ranged from 0.79 to 1.26 and the outfit MnSq values ranged from 0.77 to 1.30, consistent with the Rasch model fit criteria. In addition, the point-measure correlation coefficients indicate a good alignment of the item responses with the person abilities. They also serve as a quick check on the quality of the data and provided by the respondents. For example, negative point-measure correlations show that item responses are opposed to the construct underlying the items, whereas large, positive correlation values indicate the response scale was properly keyed, giving rise to good data quality. In this study, the point-measure correlation values ranged from (r = 0.66 to 0.78), suggesting that the data provided by the respondents were of good quality.

Person and item reliability

The Rasch person and item reliabilities for the JSBI-7 were 0.82 and 0.91, respectively, suggesting the reproducibility of the test scores. Person and item separation indices were 2.13 and 3.19, respectively.

Discussion

This study provides validity evidence for the Job Search Behaviour Index (JSBI-7) among young job seekers in Ghana. This study is the first to assess the psychometric performance of the JSBI, developed as part of a major study by Kopelman et al. (1992). Thus, this study has not only extended the work of Kopelman et al. (1992) to a new cultural context, but also it has evaluated the JSBI-7 using modern test theory. Based on the results from the parallel analysis and Scree test, a single factor model was retained and then subjected to confirmatory factor analysis and Rasch analysis. The Rasch rating scale model provided strong evidence for the unidimensionality of the JSBI-7. The Rasch dimension accounted for 54.2% of the variance in job search behaviour. The results suggest that the items underlie the latent construct. In addition, all of the items were independent of each other. In other words, the items on the JSBI-7 are not related to each other.

In addition, the JSBI-7 fitted the Rasch model very well and demonstrated good Rasch person and item reliabilities. The high reliabilities, which are interpreted like traditional Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, show that the item scores are reproducible. The person separation index of 2.13 indicated that the JSBI-7 was able to classify respondents into, at least, two distinct groups of active job seekers and passive job seekers. In other words, the JSBI-7 was sensitive enough to distinguish between high and low scorers on the trait. The item separation index of 3.19 suggested that the sample size was large enough to demonstrate the item difficulty hierarchy of the JSBI-7. This serves to establish the construct validity of the JSBI-7. Furthermore, the Rasch model demonstrated that the 5-point rating scale of the JSBI-7 was suitable. This is because the average measures increased monotonically as expected by the Rasch model. That is, the current sample was able to distinguish between the five response categories and used them well.

Moreover, no item showed uniform differential item functioning across gender. That is our DIF analysis demonstrated that scores on the latent construct can be meaningfully compared across gender. This is because the DIF results revealed that the underlying construct was equivalent across the two gender groups (male versus female). In other words, responses to the indicators of the latent construct do not depend on gender group membership, suggesting that job search was conceptualised similarly across gender in the present sample.

During preliminary data analysis, it emerged that three items on the original JSBI-10 had negative loadings on a second factor, whose eigenvalue from the actual data was far below the eigenvalue suggested by the simulated data from parallel analysis. The three misfitting items were removed and the analysis re-run. It seems those items are not salient for job search in the present sample. A possible explanation for the three misfitting items in this study is that they seem to elicit information that the current sample does not have. That is, the current sample was recent university graduates making the transition from school to work on a National Service programme. National Service in Ghana is a temporary work aimed at giving recent university graduates work experience. Therefore, misfitting items such as “Sought to transfer to a new job within your organization?” and “Talked to co-workers about getting a job in another organization?” may seem salient for individuals in permanent jobs of sorts, and who wish to explore opportunities within those work environments to get better jobs or new roles.

Further, most National Service personnel are posted to places where their services are needed with little consideration for the correspondence between their training and the core business of the organisations to which they are posted. It would seem, therefore that most National Service personnel would want to have little to do with their current workplace and its employees. Besides, most people would not tell their co-workers if they wish to quit their current job to go look for another job. The probability of such information leaking to one’s supervisors and other work colleagues can hasten one’s dismissal from the current place of work. This may be a probable reason why the following item “Talked to co-workers about getting a job in another organization?” misfitted in the present study. Moreover, in Ghana, National Service personnel are posted to organisations without going through a recruitment interview. Thus, an item such as “Gone on a job interview?” may not be salient for the present sample. In other words, the item elicits a response that the present sample does not have.

Finally, the relevance of the JSBI items to the modern world of work should be explored further. For example, an item such as “Read the classified job advertisements in the newspaper?” may not be relevant for modern job search because most newspapers have gone online; and most job advertisements are placed in specially designed job portals, managed by recruitment agencies. Successfully applying for such jobs online would require modern soft skills. The JSBI was developed in 1993 when social media, apps, smart phones, and online job portals were little known. These technological advancements have come with advantages for job search. It is clear that modern job search strategies may involve using online tools for applying for a job and writing aptitude tests (personality tests) online and/or attending interviews online via Skype or Zoom. Thus, new scale items that reflect these modern job search strategies and skills may be written to expand the content domain of the JSBI.

Implications of the results

Our results have implication for practice and research. For practice, the validated measure may be used by career counsellors and counselling psychologists working at university career and placement centres in Ghana to assess how well university graduates undertake job search. This research would provide them with useful information to help plan remedial measures to mitigate problematic job search efforts. Given the brevity of the JSBI measure, it may also be used as a quick diagnostic tool among out-of-school youths to examine their job search behaviour. For example, the youth employment agency together with ministry of employment and labour relations can use this measure to gather longitudinal data among young people making the school-to-work transition across Ghana to identify the job search challenges that confront young people. The National Service Scheme may also administer this measure as an exit programme among service personnel to gauge their preparations to enter the labour market, following the completion of mandatory national service.

For research, this measure may require further validation among various groups of young people in Ghana to adduce further validity and reliability evidence for it.

That is, future research should consider investigating the psychometric properties of the JSBI in different samples and age groups in the general population. In doing so, researchers using the JSBI should consider evaluating the three items that were removed from the present analysis. Further, it would be useful to examine how test scores from the JSBI perform in various job search domains such as job search in educational institutions versus job search in corporate organisations, or job search in public institutions versus job search in private institutions. This research may help identify new items to be included in the scale for the purposes of scale refinement.

Limitations

A limitation to note is that the results in this study are based on self-report data. It is well known that self-report data may be attended by bias. Study participants were also recruited using a non-probabilistic technique. In addition, we used confirmatory factor analysis in the present study only as an additional check on the construct unidimensionality of the JSBI-7.

Conclusion

The present study used item response theory and Rasch analysis to evaluate the construct validity and reliability of the JSBI-7. Rasch analysis showed that the JSBI-7 was unidimensional, valid, and reliable. The results demonstrate that the JSBI-7 is a promising measure for use among job seekers in Ghana.

Data availability

The data on which the article reports are available from the author on reasonable written request.

Notes

Employment status refers to the legal status and classification of a person in employment as either an employee or working on their own account (self-employed). These statistics include young people with secondary, post-secondary, and tertiary education.

As a further check on the JSBI-7’s dimensional structure we fitted the single factor model to the data in a confirmatory factor analysis, using maximum likelihood estimation in Mplus. The measurement model demonstrated good fit: χ2(14) = 45.33, p < .001, CFI = 0.974, RMSEA = 0.072; 90% CI [.049, .096]; SRMR = 0.028.

Note that the cut-off criteria for the fit statistics are general Rasch quality-control guidelines but not definite rules.

References

Aduhene, D. T., & Osei-Assibey, E. (2021). Socio-economic impact of COVID-19 on Ghana’s economy: Challenges and prospects. International Journal of Social Economics, 48(4), 543–556. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSE-08-2020-0582

Affum-Osei, E., Asante, E. A., Forkouh, S. K., Aboagye, M. O., & Antwi, C. O. (2019). Unemployment trends and labour market entry in Ghana: Job search methods perspective. Labor History, 60(6), 716–733. https://doi.org/10.1080/0023656X.2019.1640356.

Andrich, D. (1978). Scaling attitude items constructed and scored in the Likert tradition. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 38(3), 665–680. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316447803800308

Andrich, D. (2011). Rating scales and Rasch measurement. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics Outcomes Research, 11(5), 571–585. https://doi.org/10.1586/ERP.11.59

Andrich, D., & Marais, I. (2019). A Course in Rasch Measurement Theory Measuring in the Educational, Social and Health Sciences. Berlin: Springer Nature.

Aryadoust, V., Ng, L. Y., & Sayama, H. (2020). A comprehensive review of Rasch measurement in language assessment: Recommendations and guidelines for research. Language Testing. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532220927487

Aryadoust, V., Tan, H. A. H., & Ng, L. Y. (2019). A Scientometric review of Rasch measurement: The rise and progress of a specialty. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2197. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02197

Aryeetey, E., & Baah-Boateng, W. (2016). Understanding Ghana’s growth success story and job creation challenges (No. 2015/140). Helsinki, Finland: The United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER).

Baah-Boateng, W. (2015). Unemployment in Ghana: A cross sectional analysis from demand and supply perspectives. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies, 6(4), 402–415. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJEMS-11-2014-0089

Bond, T. G., & Fox, C. M. (2015). Applying the Rasch Model: Fundamental Measurement in the Human Sciences (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Boone, W. J. (2016). Rasch analysis for instrument development: Why, when, and how? Life Sciences Education, 15(4), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-04-0148

Boone, W. J., & Noltemeyer, A. (2017). Rasch analysis: A primer for school psychology researchers and practitioners. Cogent Education, 4(1), 1416898. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2017.1416898

Boone, W. J., Staver, J. R., & Yale, M. S. (2014). Rasch Analysis in the Human Sciences. Dordrecht: Springer Nature.

Boone, W. J., Staver, J. R., & Yale, M. S. (2014). The Rasch model and item response theory models: Identical, similar, or unique? In W. J. Boone, J. R. Staver, & M. S. Yale (Eds.), Rasch Analysis in the Human Sciences (Vol. 1, pp. 449–458). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6857-4_21

Bravini, E., Giordano, A., Sartorio, F., Ferriero, G., & Vercelli, S. (2016). Rasch analysis of the Italian lower extremity functional scale: Insights on dimensionality and suggestions for an improved 15-item version. Clinical Rehabilitation. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269

Bugri, M. (2020, January). Angry youth ground NPP chair's vehicle for failing to give them jobs. Retrieved from https://www.myjoyonline.com/politics/2020/January-11th/angry-youth-ground-npp-chairs-vehicle-for-failing-to-give-them-jobs.php. Accessed on July 18, 2020

Carpenter, S. (2018). Ten steps in scale development and reporting: A guide for researchers. Communication Methods and Measures, 12(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2017.1396583

Chang, C.-C., Su, J.-A., & Lin, C.-Y. (2016). Using the Affiliate Stigma Scale with caregivers of people with dementia: Psychometric evaluation. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy, 8, 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13195-016-0213-y

Chang, C.-C., Su, J.-A., Tsai, C.-S., Yen, C.-F., Liu, J.-H., & Lin, C.-Y. (2015). Rasch analysis suggested three unidimensional domains for Affiliate Stigma Scale: Additional psychometric evaluation. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 68, 674–683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.01.018

Chang, K.-C., Wang, J.-D., Tang, H.-P., Cheng, C.-M., & Lin, C.-Y. (2014). Psychometric evaluation, using Rasch analysis, of the WHOQOL-BREF in heroin-dependent people undergoing methadone maintenance treatment: Further item validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 12, 148. http://www.hqlo.com/content/12/1/148

Christensen, K. B., Makransky, G., & Horton, M. (2017). Critical values for Yen’s Q3: Identification of local dependence in the Rasch model using residual correlations. Applied Psychological Measurement, 41(3), 178–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146621616677520

Damoah, O. B. O., Peprah, A. A., & Brefo, K. O. (2021). Does higher education equip graduate students with the employability skills employers require? The perceptions of employers in Ghana. Journal of Further and Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2020.1860204.

Earp, B. D., & Trafimow, D. (2015). Replication, falsification, and the crisis of confidence in social psychology. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 621. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00621.

Edwards, M. C., Houts, C. R., & Cai, L. (2018). A diagnostic procedure to detect departures from local independence in item response theory models. Psychological Methods, 23(1), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000121.

Debelak, R., & Koller, I. (2020). Testing the local independence assumption of the Rasch model with Q3-based nonparametric model tests. Applied Psychological Measurement, 44(2), 103–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146621619835501

De Bruin, G. P., Hill, C., Henn, C. M., & Muller, K.-P. (2013). Dimensionality of the UWES-17: An item response modelling analysis. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 39(2), 1148. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v39i2.1148

Embretson, S. E., & Reise, S. P. (2000). Item Response Theory for Psychologists. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Eriksson, S., & Lagerström, J. (2012). The labor market consequences of gender differences in job search. Journal of Labor Research, 33, 303–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-012-9132-2

Field, A. (2018). Discovering Statistics Using SPSS (5th ed.). London: Sage.

Ghana News Agency. (2017). Only 10 percent of graduates find jobs after first year—ISSER Research. Retrieved from https://www.myjoyonline.com/news/2017/june-3rd/only-10-percent-of-graduates-find-jobs-after-first-year-isser-research.php. Accessed on July 18, 2020

Ghana Statistical Service. (2016). 2015 Labor force report. Retrieved from https://statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/fileUpload/Demography/LFS%20REPORT_fianl_21-3-17.pdf

Grosemans, I., Coertjens, L., & Kyndt, E. (2017). Exploring learning and fit in the transition from higher education to the labour market: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 21, 67–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2017.03.001

Hagquist, C., & Andrich, D. (2017). Recent advances in analysis of differential item functioning in health research using the Rasch model. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 15, 181. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-017-0755-0

Hattie, J. (2015). Dimensionality of tests: Methodology. In J. Hattie (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (2nd ed., pp. 437–439). New York: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.44016-X

Hawkins, R. X. D., Smith, E. N., Au, C., Arias, J. M., Catapano, R., Hermann, E., Keil, M., Lampinen, A., Raposo, S., Reynolds, J., Salehi, S., Salloum, J., Tan, J., & Frank, M. C. (2018). Improving the replicability of psychological science through pedagogy. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 1(1), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/251524591774042

Hobart, J. C., Cano, S. J., Zajicek, J. P., & Thompson, A. J. (2007). Rating scales as outcome measures for clinical trials in neurology: Problems, solutions, and recommendations. Lancet Neurology, 6, 1094–1105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70290-9

IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0 (2017). https://www.ibm.com/support/pages/node/598509

International Labour Organisation. (2019). From school to work: An analysis of youth labour market transitions. Retrieved from https://ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---stat/documents/publication/wcms_732422.pdf. Accessed May 18, 2021

International Labour Organisation. (2020). Transition from school-to-work remains a difficult process for youth. Retrieved from https://ilostat.ilo.org/transition-from-school-to-work-remains-a-difficult-process-for-youth/. Accessed May 18, 2021

Jones, R. N. (2019). Differential item functioning and its relevance to epidemiology. Current Epidemiology Reports, 6, 174–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-019-00194-5

Kanfer, R., Wanberg, C. R., & Kantrowitz, T. M. (2001). Job search and employment: A personality motivational analysis and meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 837–855. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.5.837

Khine, M. S. (Ed.). (2020). Rasch Measurement Applications in Quantitative Educational Research. Berlin: Springer Nature.

Koen, J., Klehe, U.-C., & van Vianen, A. E. M. (2012). Training career adaptability to facilitate a successful school-to-work transition. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 81, 395–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2012.10.003

Kopelman, R. E., Rovenpor, J. L., & Millsap, R. E. (1992). Rationale and construct validity evidence for the job search behavior index: Because intentions (and new year’s resolutions) often come to naught. Journal of Vocation Behaviour, 40, 269–287.

Lambert, S. D., Pallant, J. F., Boyes, A. W., King, M. T., Britton, B., & Girgis, A. (2013). A Rasch analysis of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) among cancer survivors. Psychological Assessment, 25, 379–390. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031154

Linacre, J. M. (1998). Detecting multidimensionality: Which residual data-type works best? Journal of Outcome Measurement, 2(3), 266–283.

Linacre, J. M. (1998). Structure in Rasch residuals: Why principal components analysis? Rasch Measurement Transactions, 12(2), 636.

Linacre, J. M. (2019). Winsteps® (Version 4.4.2) [Computer Software]. Winsteps.com. Retrieved May 8, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.winsteps.com/

Linacre, J. M. (2020). Winsteps® (version 4.5.2) [Computer Software]. Winsteps.com. Retrieved April 28, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.winsteps.com/

MacCallum, R. C., Widaman, K. F., Zhang, S., & Hong, S. (1999). Sample size in factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 4(1), 84–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.4.1.84

Matsumoto, M., & Elder, S. (2010). Characterizing the school-to-work transition of young men and women: Evidence from the ILO school-to-work transition surveys (ILO Employment Working Paper No. 51), Geneva. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/employment/Whatwedo/Publications/working-papers/WCMS_141016/lang--en/index.htm. Accessed May 18, 2021

McKee-Ryan, F. M., Song, Z., Wanberg, C. R., & Kinicki, A. J. (2005). Psychological and physical well-being during unemployment: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 53–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.53

Nwokolo, M.-N. (2019, December 10). Beyond business as usual: Addressing Ghana’s unemployment woes. Retrieved from https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2019-12-10-beyond-business-as-usual-addressing-ghanas-unemployment-woes/#gsc.tab=0. Accessed on July 18, 2020

Nudzor, H. P., & Ansah, F. (2020). Enhancing post-graduate programme effectiveness through tracer studies: the reflective accounts of a Ghanaian nationwide graduate tracer study research team. Quality in Higher Education, 26(2), 192–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2020.1763034.

Odame, L., Osei-Hwedie, B., Nketsia, W., Opoku, M. P., & Arthur, B. N. (2021). University preparation and the work capabilities of visually impaired graduates in Ghana: A tracer study. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 25(11), 1287–1304. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2019.1609102.

OECD. (1999). Preparing youth for the 21st century: The transition from education to the labour market, Paris: OECD. Retrieved from http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/104147

OECD. (1998). Thematic review of the transition from initial education to working life: United Kingdom: Background report. Paris: OECD. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/35/54/1908270.pdf

Paul, K. I., & Moser, K. (2009). Unemployment impairs mental health: Meta-analyses. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 74, 264–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.01.001

Raîche, G. (2005). Critical eigenvalue sizes in standardized residual principal components analysis. Rasch Measurement Transactions, 19, 1012. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012471352-9/50004-3

Raubenheimer, J. (2004). An item selection procedure to maximise scale reliability and validity. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 30(4), 59–64. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v30i4.168

Rasch, G. (1960). Probabilistic Models for Some Intelligence and Attainment Tests. Danmarks Paedogogiske Institut.

Raykov, T., & Marcoulides, G. A. (2011). Introduction to Psychometric Theory. Routelege: Taylor and Francis Group.

Raykov, T., & Marcoulides, G. A. (2015). On the relationship between classical test theory and item response theory. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 76(2), 325–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164415576958

Røe, C., Damsgård, E., Fors, T., & Anke, A. (2014). Psychometric properties of the pain stages of change questionnaire as evaluated by Rasch analysis in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 15, 95. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2474/15/95

Ryan, P. (2001). The school-to-work transition: A cross-national perspective. Journal of Economic Literature, 39(1), 34–92.

Saks, A. M. (2018). Job search and the school-to-work transition. In U. C. Klehe & E. A. J. van Hooft (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Job Loss and Job Search (pp. 1–29). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199764921.013.008

Schotte, S., Danquah, M., Osei, D. R., & Sen, K. (March, 2021). The Labour Market Impact of COVID-19 Lockdowns: Evidence from Ghana (WIDER Working Paper 27/2021). https://doi.org/10.35188/UNU-WIDER/2021/965-5

Smith, E. V., Jr. (2002). Understanding Rasch measurement: Detecting and evaluating the impact of multidimenstionality using item fit statistics and principal component analysis of residuals. Journal of Applied Measurement, 3(2), 205–231.

Smith, R. M., & Plackner, C. (2009). The family approach to assessing fit in Rasch measurement. Journal of Applied Measurement, 10, 424–437.

Souza, M. A. P., Coster, W. J., Mancini, M. C., Dutra, F. C. M. S., Kramer, J., & Sampaio, R. F. (2017). Rasch analysis of the participation scale (P-scale): Usefulness of the P-scale to a rehabilitation services network. BMC Public Health, 17, 934. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4945-9

Suuk, M. (2016, June 3). Ghana's new graduates struggle to find jobs. Retrieved from https://www.dw.com/en/ghanas-new-graduates-struggle-to-find-jobs/a-19305185. Accessed on July 18, 2020

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using Multivariate Statistics (6th ed.). London: Pearson Education.

Testa, S., Doucerain, M. M., Migliettaa, A., Jurcik, T., Ryder, A. G., & Gattino, S. (2019). The Vancouver Index of Acculturation (VIA): New evidence on dimensionality and measurement invariance across two cultural settings. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 71, 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2019.04.001

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). (2019a). Unpacking school-to-work transition: Data and evidence synthesis. Retrieved from file:///C:/Users/user/Downloads/Unpacking-School-to-Work-Transition-Scoping-Paper_2019.pdf. Accessed May 18, 2021

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). (2019b). Transitions from school to work. UNICEF technical note. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/media/60366/file/Transitions-from-school-to-work-2019.pdf, Accessed May 18, 2021

Watkins, M. W. (2000). Monte Carlo PCA for parallel analysis [Computer Software]. State College, PA: Ed & Psych Associates. Retrieved from http://edpsychassociates.com/Watkins3.html. Accessed on July 18, 2020

World Bank. (2020a). Addressing youth unemployment in Ghana needs urgent action, calls new World Bank Report. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/09/29/addressing-youth-unemployment-in-ghana-needs-urgent-action

World Bank. (2020b). COVID-19 forced businesses in Ghana to reduce wages for over 770,000 workers, and caused about 42,000 layoffs—research reveals. Retrieved from https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/08/03/covid-19-forced-businesses-in-ghana-to-reduce-wages-for-over-770000-workers-and-caused-about-42000-layoffs-research-reveals. Accessed May 18, 2021

Worthington, R. L., & Whittaker, T. A. (2006). Scale development research. A content analysis for recommendations for best practices. The Counseling Psychologist, 34(6), 806–838. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006288127

Woudstra, A. J., Meppelink, C. S., Pander Maat, H., Oosterhaven, J., Fransen, M. P., & Dima, A. L. (2019). Validation of the short assessment of health literacy (SAHL-D) and short-form development: Rasch analysis. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19, 122. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0762-4

Yeboah, O. A. (2019, March 14). How unemployment is ‘stealing’ the youths’ future. Retrieved from https://thebftonline.com/2019/economy/how-unemployment-is-stealing-the-youths-future/. Accessed on July 18, 2020

Zhong, Q., Gelaye, B., Fann, J. R., Sanchez, S. E., & Williams, M. A. (2014). Cross-cultural validity of the Spanish version of PHQ-9 among pregnant Peruvian women: A Rasch item response theory analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 158, 148–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.012

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship award from the Department of Industrial Psychology, Stellenbosch University, to the author.

Funding

There is no funding to report for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declares that he has no conflicts of interest to report.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants of the study.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Ghana (Ref#: ECH116/19–20).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Teye-Kwadjo, E. Psychometric properties of the Job Search Behaviour Index (JSBI) in recent university graduates: a Rasch analysis. Int J Educ Vocat Guidance 23, 249–270 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-021-09501-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10775-021-09501-3