Abstract

While many papers have focused on socially unequal admissions in higher education, this paper looks at the persistence of class differentials after enrolment. I examine the social class gap in bachelor’s programme dropout and in the transition from bachelor’s to master’s in Denmark from the formal introduction of the bachelor’s degree in 1993 up to recent cohorts. Using administrative data, I find that the class gap in bachelor’s departures has remained constant from 1993 to 2006, with disadvantaged students being around 15 percentage points more likely to leave a bachelor’s programme than advantaged students, even after adjusting for other factors such as grades from upper secondary school. Importantly, the class gap reappears at the master’s level, with privileged students being more likely to pursue a master’s degree than less privileged students. The size of the class gap is remarkable, given that this gap is found among a selected group of university enrolees. As other studies have found that educational expansion in higher education is not necessarily a remedy for narrowing the class gap in educational attainment, scholars need to pay more attention to keeping disadvantaged students from leaving higher education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Class differentials in higher education persist despite the massive expansion of higher education (Bar Haim & Shavit, 2013; Shavit et al., 2007; Thomsen et al., 2017). Although disadvantaged students have increasingly taken up the educational opportunities offered to them, their friends from privileged backgrounds have done the same and continue to be much more likely to enter higher education than students from less privileged backgrounds. However, inequality in higher education not only concerns enrolment but also attainment and graduation. Until recently, researchers have paid little attention to class differentials in attainment — that is, to processes of inequality after the students have entered the gates of higher education. Taking advantage of high-quality Danish data, this paper targets social inequality in attainment after bachelor’s administrative enrolment by investigating the social class gap in the risk of not obtaining a bachelor’s and not pursuing a master’s degree across a period of educational expansion.

As in most other industrialized nations, an ever-larger share of the youth cohort have gained access to higher education in Denmark (a tenfold increase from 1957 to 2007, according to Statbank; Statistics Denmark’s online tool). The Nordic welfare model is routinely associated with the highest educational mobility in the world, with young people being much more likely to achieve a higher education degree in Denmark than in the USA or UK, for example (Narayan et al., 2018; OECD, 2018). Nevertheless, even in Denmark — a country with low economic inequality, no tuition fees and universal government grants for all higher education students — inequality in access to higher education is substantial and has decreased only slightly over the last 20–30 years. In fact, access to higher education continues to favour privileged children disproportionately, especially at university institutions offering sought-after, prestigious programmes (Thomsen, 2015). The substantial inequality, even in a Nordic welfare state setting, has led scholars to underline the great importance of family cultural capital in educational reproduction as an explanation for the class gap in educational attainment (Jæger & Holm, 2007).

Because the challenge to inequality in higher education has largely been perceived as an enrolment issue — with a focus on increasing admission rates for first-generation students — the class gaps in higher education attainment after successful admission have received less attention (Herbaut, 2020). One reason may likely be that scholars have expected the attainment problem to diminish after each educational transition, as the student body becomes an increasingly selected one (Bourdieu et al., 1994; Mare, 1981, 1993). This is particularly true for first-generation students, with only about 1 in 20 children from homes with no post-secondary education having made the transition to university studies in Denmark, whereas 1 in 3 from academic homes have done so (Thomsen, 2012). All else being equal, we would expect the group of highly selected first-generation students to be so motivated and well-equipped for higher education studies that their progression pattern would resemble that of their privileged peers. However, recent studies dampen this expectation: Hovdhaugen (2009) concludes that having less educated parents increased the risk of dropout from bachelor’s programmes, Herbaut (2020) finds that disadvantaged students were more likely to drop out after academic failure in the first year of higher education than advantaged students, and Goldrick-Rab (2006) shows how students with lower socioeconomic status have more interrupted college pathways than their privileged peers.

In this paper, I add to our knowledge of class differentials in student departure in higher education by offering a more comprehensive look at the problem than has been previously provided. Taking advantage of rich administrative student data (where there are no issues with non-responses, attrition, etc.) I examine all who enrols in a bachelor’s programme from the introduction of the bachelor’s degree in 1993 up until recent bachelor cohorts and to include detailed information on educational pathways and social background characteristics (see ‘Data’ section). I make three contributions to the literature on social class gaps in student dropout, as I examine: (1) the social class gap in the risk of not obtaining a bachelor’s and a master’s degree for students enrolled in bachelor’s programme across a period of educational expansion, (2) how dropout is associated with field of study and university institution and (3) if there is a social gradient in the subsequent educational careers for bachelor dropouts.

Not only is it necessary to shed light on the size of the class gap among students enrolled in higher education, it is also important to gauge if and how the class gap has changed from 1993 (the year of the formal introduction of the bachelor’s degree) onwards — a period in which higher education has expanded substantially. While higher education expansion has provided more opportunities for disadvantaged students, it is less clear how this expansion has affected dropout patterns, and studies have largely overlooked trends across bachelor cohorts. In addition, it is important to examine dropout patterns across fields of study and institutions, as they may capture differences in students’ preferences, motivation or level of ‘preparedness’ as well as their academic and social integration (Tinto, 1993). Lastly, it is important to follow students long after their departure to see if students from advantaged backgrounds compensate for an early bachelor’s programme departure by eventually ending up with higher educational qualifications than bachelor programme leavers from more disadvantaged backgrounds.

Dropout in higher education — theoretical perspectives and existing knowledge

As this paper’s focus is the social class gap in student departure, I will briefly outline the two major theoretical traditions in the sociology of education: rational action theory and cultural reproduction theory. While cultural reproduction theory places weight on causes that are structural or what students are predisposed to do, relative risk theory focuses on how individuals weigh their options and make individual risk assessments. In a relative risk theory framework, working-class families will tend to avoid overly risky educational investments (Breen & Goldthorpe, 1997; Goldthorpe, 1996). This may, in some cases, translate into leaving a bachelor’s programme, because the risk of staying is perceived to be too great (unemployment trends, signals of low academic level, etc.) or because the student prefers other more applied programmes or direct entry into the labour market. Boudon (1974) has argued that differential educational outcomes stem from both the ‘primary effects’ of socialization, where the relationship between social origin and scholastic abilities sets out the educational opportunities of the child, and the ‘secondary effects’ — if and how young people realize their educational potentials, given their scholastic abilities. Secondary effects capture the non-cognitive skills (preferences, dispositions, expectations, etc.) that lead children from different social origins to vary in their risk-averse behaviour, even if they have the same scholastic abilities. As such, secondary effects may explain why working-class students, socialized into working-class reproduction patterns, are more likely to turn away from further education, or to drop out, than their middle-class counterparts.

Cultural reproduction theory (Bourdieu, 1986, 1996) emphasizes structural constraints and focuses on disparities in resources available to students and the different habitus and dispositions with which they are endowed. Cultural reproduction theory identifies cultural capital as a key mechanism for social reproduction that occurs in the educational system when cultural capital is rewarded as (or mistaken for) academic ability, privileging students from higher educated homes with high levels of cultural capital. From a cultural reproduction perspective, disadvantaged students may have troubled experiences for several reasons. In contrast to middle-class youth, who have a ‘college-going’ habitus (Grodsky & Riegle-Crumb, 2010), working-class students perceive the choice of higher education as a riskier, more uncertain choice (Archer & Hutchings, 2000; Reay, 2003; Winterton & Irwin, 2012). Working-class students report feelings of alienation and dislocation (Christie et al., 2008; Reay et al., 2009) and may find themselves estranged and unfamiliar with the workings of what goes on ‘inside the college gates’ (Stuber, 2011). In addition, the educational system may carry an ‘institutional habitus’ (Reay et al., 2001), disadvantaging first-generation students via institutional cultures that label them as ‘other’ (Reay, 2003), use particular language codes (Bernstein, 1990) or presuppose particular, ‘implied’ students (Ulriksen, 2009).

The empirical literature specifically targeting dropout in higher education has often used the seminal work by Tinto (1993) as a key reference point (for a systematic review, see Larsen et al., 2013). In examining the mechanisms of student departure, Tinto (1993) distinguishes between: (1) a student’s previous dispositions before entering higher education (commitment, preferences, intentions); (2) experiences at the higher education institution, where Tinto emphasizes academic and social integration, and (3) external causes (economic barriers, family commitments, etc.). In practice, departure may be the result of a mixture of these factors. For instance, a student may depart because the programme did not match his or her interests and preferences after all, because the student feels estranged at the programme, because the programme turns out to be too academically demanding or simply because circumstances may necessitate that the student leave higher education to work full time. As such, differences in dropout may well be proxies of pre-entrance characteristics such as preferences and motivation. Highly sought-after programmes, like medicine and architecture, requiring high Gymnasium GPAs to enter, may display low dropout rates, but this does not necessarily mean that they provide for a better academic and social environment than other studies; it may simply reflect the fact that students in these programmes are highly motivated and qualified for studying. Scholars should use caution when interpreting dropout rates as reflections of how the students are ‘treated’ in the programmes, as there is strong selection into programmes (differences in preferences, skills, motivation, cultural and academic familiarity, etc.). Consequently, the empirical stratification literature on student departure does not always pinpoint the mechanisms behind student departure exactly but infers from proxies known to be powerful predictors of leaving higher education. One powerful predictor is social origin, with several studies showing how parental resources (education, occupation, income) impact student attainment: Wilbur and Roscigno (2016) have found that first-generation students face several challenges, such as lack of family resources, absence of college-focused parental actions and lack of integration at the institution. Students with lower socioeconomic status have more interrupted higher education pathways and increased risk of departure than their privileged peers (Goldrick-Rab, 2006; Hovdhaugen, 2009), and they are more likely to drop out after academic failure in the first year of higher education than are advantaged students (Herbaut, 2020). Zarifa et al. (2018) have shown that children from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are less likely to complete their bachelor’s degrees on time than are children from higher socioeconomic backgrounds. In addition, Haveman and Wilson (2007) finds that, conditional on going to college, the gap is 33 points to earn a degree between students originating in the bottom and top quarters of the income distribution (see also Argentin & Triventi, 2011; Johnes & Mcnabb, 2004; Vignoles & Powdthavee, 2009). In general, higher educated parents hold more specific knowledge about the workings of the educational system, which may in turn help their children in planning, preparing and successfully navigating a college career (Goldrick-Rab & Pfeffer, 2009). Some studies draw on the mechanism of ‘compensatory advantage’ (Bernardi, 2014) — that is, when advantaged students are ‘compensated’ by background privileges even if they only have average or below-average qualifications; for instance, Contini et al. (2018) find that the social gap in higher education dropout is largest among low-achieving students.

The Danish context (see Troelsen & Laursen, 2014), along with existing knowledge and theories on dropout and social class gaps in education, prompts me to make the following hypotheses:

-

1.

Given the educational expansion in the period investigated, I expect dropout rates to rise. When an increasing share of a youth cohort enters higher education, we could expect a dilution of the talent pool, i.e. an increase in less qualified and motivated students, being more likely to depart.

-

2.

Given the Danish welfare state context and the selection in bachelor’s enrolment (i.e. only highly motivated and qualified disadvantaged students), I expect the class gap in dropout to be small and insignificant.

-

3.

I expect the social gradient in dropout rates to be lower at applied/professional programmes (as these are more appealing to disadvantaged students focusing on utility and a risk-free choice of bachelor programme).

-

4.

I expect less academically successful students from privileged backgrounds to be ‘compensated’ by their social origin in two ways: their dropout rates will be lower than less successful disadvantaged students, and they will be more likely to ultimately obtain a master’s despite having dropped out of their bachelor programme.

Study context, data and methods

University dropout in Denmark occurs in a society with less constrain on educational choices than in many other countries: comparatively, social security is high and labour market prospects are good for both men and women. Pre-school education (day care) is universal and affordable, there is no tracking in compulsory school (grades 0 to 9), there are no tuition fees in education, and every student in a higher education programme receives a government grant of €840 monthly (2020 figures) while studying. The educational system consists of 10 years of compulsory education (grades zero to 9) for 6- to 15-year-olds, with an optional 10th grade. After compulsory school, about two out of three students continue into the 3-year higher education preparatory academic track in upper secondary school (Gymnasium), with a general academic track (‘STX’), a track often taken by mature students (‘HF’) and two vocationally oriented academic tracks (technical and business-oriented, ‘HTX’ and ‘HHX’, respectively). A third opt for a vocational education and training (VET) programme (typically 3 to 4 years), in which students qualify for a broad range of craft occupations (e.g. carpenters, electricians, construction and service work). A diploma from the higher education preparatory-upper secondary school, ‘Gymnasium’, will formally grant access to a higher education programme, provided that the programme has the space to accept all applicants. This is the case for most programmes, but for a number of university programmes, demand exceeds supply, and in such cases, admission is determined by the applicant’s Gymnasium grade point average (GPA), with a small share of applicants admitted on the basis of alternative qualifications.

The higher educational system is public and made up of business academies, university colleges and universities. Business academies feature 2- to 3-year programmes primarily directed towards the private sector. University colleges offer 3- to 4-year semi-professional programmes that primarily educate welfare state civil servants (teachers, nurses and childcare and social workers). Universities hold a wide range of traditional liberal arts and professional programmes and enrol the majority of all higher education students. Universities offer 3-year bachelor’s programmes, 2-year master’s programmes and 3-year PhD programmes. The bachelor’s programmes at university institutions are the most selective, with demand often exceeding supply, and some highly sought-after, prestigious university programmes (medicine, political science, psychology, architecture, etc.) require a very high GPA to enter. This article focuses specifically on university programmes, the higher education programmes in which social disparities are most pronounced. All bachelor’s degree holders are entitled to continue directly into the consecutive master’s programme without having to apply, and more than four out of five students choose to continue into a master’s programme. Historically, there has not been a labour market for bachelor’s degree holders in Denmark. Danish University programmes were originally 5-year programmes, and splitting them up into a bachelor’s and master’s level (3 + 2 years) has not led to a labour market for bachelor’s degree holders.

Data

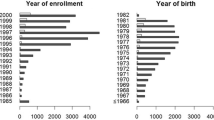

I use administrative data from Statistics Denmark and include all students enrolled for the first time in a university bachelor’s programme in each year from 1993 to 2006, totalling 185,939 individuals.Footnote 1 Danish administrative data contain information from governmental records on all citizens, including information on gender, date of birth, parents, place of residence and income, along with educational attainment (level and type of education, degrees, grades, etc.). Data are linked together by a unique anonymized personal identification number; because data come from governmental records, there are no issues with non-responses, attrition bias or other incomplete information.

As the dependent variable, I use student dropout status. Often, researchers distinguish between leaving a higher education institution (transferring to another programme) and leaving the higher educational system all together (dropping out of higher education completely). Tinto (1993) makes such a distinction — between institutional and system departure — one taken up by Hovdhaugen (2009), who distinguishes between transfer and dropout when researching higher education movements. I follow these scholars and define bachelor dropout as those who leave a bachelor’s programme all together. This means that students may have transferred from one bachelor programme to another (at the same or at another institution), but they only count as dropouts if they have not graduated from any bachelor’s programme. More specifically, I define a bachelor dropout as a person who has not graduated with a bachelor’s degree from any programme 8 years after enrolment, well after the stipulated time for a bachelor’s degree (3 years). Similarly, I define master’s degree obtainment as successful if a student has obtained a master’s degree 12 years after bachelor’s enrolment (the stipulated time for a bachelor + master’s degree is 3 + 2 years).Footnote 2 In the analysis, I also consider those who leave a bachelor’s programme to eventually obtain other educational qualifications. Here, I look at the highest obtained diploma/degree for bachelor’s students 12 years after enrolment. Applying a hierarchical logic, these students can be conceptualized as ‘dropping down’ (if they, for instance, leave a bachelor’s programme for a VET programme) or ‘dropping up’ (leaving a bachelor study for a master’s programme, which can happen if bachelor dropouts successfully apply individually for master’s enrolment despite not holding a bachelor’s degree).

In the analysis, I focus on how social background predicts dropout, and I adjust for a few key variables. For social background, I use information on parental education retrieved at the point of the child’s enrolment year. On the one hand, educational categories make it potentially problematic to compare the same groups of parents over time. For example, the general rise in educational levels in the population means that a home with no higher education may not be a proxy for the same home environment in 1993 as it is in 2006. Income can more easily be divided into same-size groups, which enable us to compare the same group of parents across time (e.g. incomes in the lowest 20% across the period). However, I choose education because it is a proxy for cultural capital, which is expected to play a key role in bachelor dropout. In addition, comparing dropout patterns by parental education (no-upper secondary education and university) and income (bottom and top quintile), respectively, show near identical trends over time (see appendix figure A1). In the analyses, I define advantaged students as coming from homes where at least one parent has a university degree and disadvantaged students as coming from homes with no-upper secondary education.

For academic ability, I use Gymnasium GPA. As a measure of academic qualifications, Gymnasium GPA determines the accessibility of university programmes, and studies have found dropout rates in higher education to be negatively correlated with upper secondary school GPA (Allensworth & Clark, 2020; Hovdhaugen, 2009). In addition, I include field of study and enrolment institution (where relevant) and gender and ethnic minority status (Western/non-Western origin) as adjustment variables.

Method

I use linear probability models to predict university departure status.Footnote 3 Compared to logistical regression, linear probability model estimates are easier to interpret, allow coefficient comparison across models and groups and produce coefficients close to identical to predicted probabilities derived from logit models (Mood, 2009; for a recent application of linear probability models predicting college attendance, see Doren & Grodsky, 2016).Footnote 4 I present figures depicting the risk of not obtaining a bachelor’s degree vis-à-vis not obtaining a master’s degree (tables with all estimates appear in the appendix). As mentioned earlier, students enrolled in a bachelor’s programme are a selected group of young people, and working-class students making the transition to university are arguably even more selected than middle-class students. It is reasonable to assume that working-class students, having made it so far in the educational system, possess a range of unobserved characteristics (being highly determined, motivated, etc.). The literature would suggest that models that do not account for selection in educational transitions (caused by selection based on unobservable factors) are likely to produce downwardly biased social origin effect sizes (‘waning coefficients’; Holm & Jæger, 2011; Mare, 1993). Some scholars try to account for selection by introducing exogenous variation in the shape of instrument variables, but credible instruments are notoriously difficult to employ in educational research. In addition, two papers have found diverging effects for selection on the mobility of college degree holders (Karlson, 2019; Zhou, 2019). In any case, as we may be selecting based on unobservable factors, the size of the class gap is, if anything, likely to be a conservative estimate.

Analysis

I start out with a brief overview of the characteristics of students enrolled in bachelor’s programmes in Table 1, and for brevity, I list characteristics for selected years only.

As noted, the expansion of higher education has led a higher and higher share of each youth cohort to enrol in a bachelor’s programme: 15% of all those born in 1975 enrolled before age 26, while 25% of all those born in 1985 did the same. When universities admit an increasing share of a youth cohort, we expect a dilution of the talent pool, but the mean Gymnasium GPA has been stable for bachelor’s students. The expansion has not translated into a higher dropout rate; on the contrary, the dropout rate has decreased substantially from 38 to 25% between 1993 and 2006. In addition, there is nothing indicating that changes in the dropout rate are affected by enrolment age, gap year and time to degree, as these are stable across the period. I will return to the decreasing dropout rate in the presentation of the model results below.Footnote 5

Dropout by field and institution

As discussed above, Tinto’s (1993) work on student departure focused on academic and social integration, and differences in dropout by field of study and institution could suggest that some programmes or institutions tackle academic and social integration better than others. The literature examining dropout by field/programme shows mixed results (Larsen et al., 2013). Differences in dropout by field or institution might well be proxies for pre-entrance characteristics, like preferences and motivation. For instance, we can expect the social gradient for dropout to be smaller in the applied or professional programmes because the programme profile and curriculum are more appealing to first-generation students focusing on utility and risk-free choices (making them less likely to leave these programmes than liberal arts programmes). I examine social gaps in dropout by field of study in Fig. 1.

Risk of bachelor dropout by field of study and social background (adjusted for enrolment year, Gymnasium GPA, gender and ethnic minority status). Note: See online appendix table 1 for model estimates

On average, dropout rates in humanities and natural science are relatively high, while rates are relatively low in journalism, engineering, architecture, agriculture and medicine (means not shown in figure). These latter programmes are applied/professional programmes that often require a high GPA to enter. Looking at the social gradient, students from disadvantaged backgrounds tend to drop out less in applied programmes, with low dropout rates in journalism, engineering, architecture, and medicine. However, this pattern is also a reflection of how selective these programmes are, with the class gap being smallest among selective programmes requiring high GPAs to enter (like arts, architecture and medicine) and highest among the less selective programmes (like humanities and natural science). Although the administrative data used in this paper do not allow for an assessment of degrees of inclusiveness in different programmes, the pattern suggests that low dropout rates among disadvantaged students are likely linked to pre-entrance characteristics, like preferences and motivation, as rates are low in fields that are selective or applied.

The picture is less clear when we turn to institutional dropout in Fig. 2. The gap in risk of dropout is evenly distributed, but somewhat higher at the oldest university in Denmark, the University of Copenhagen. This university not only has the highest share of selective programmes but also has one of the highest dropout rates, most similar to the rate of the much younger University of Southern Denmark, which has a low share of selective programmes. Another young institution, Roskilde University, displays relatively low dropout rates. This university practices a project-oriented work form, which could be linked to the low dropout rates. However, in terms of GPA, these institutions are also some of the easiest to get into, which means that enrolled students may find it unattractive to depart, as it will be difficult for them to re-enrol in more sought-after institutions.Footnote 6

Risk of bachelor dropout by institution and social background (adjusted for enrolment year, Gymnasium GPA, gender and ethnic minority status). Note: See online appendix table 2 for model estimates

The mixed institutional picture likely reflects the fact that Denmark lacks multi-faculty elite universities, like Oxford and Cambridge in the UK, which means that advantaged students seek out specific prestigious, lucrative or sought-after programmes more than they target institutions. Hence, social selectivity in admission will be more programme specific than institution specific, and looking at dropout rates at the aggregated institutional level likely covers up programme-specific variations in dropout risks. In sum, the dropout pattern seems to be correlated with how hard it is to get into the programme and with how applied-oriented the programme is. I now turn my attention to the social gap in dropout rates across programmes. I first examine bachelor dropout, then look at master’s completion before finally examining what kind of educational credentials bachelor dropouts eventually achieve.

Bachelor programme dropout

Figure 3 depicts the predicted risk of bachelor dropout from a model interacting enrolment year and social origin, and adjusting for key background variables (Gymnasium GPA, gender and minority status). First, the risk of dropout decreases substantially across the period (from 42 to 31% for disadvantaged students, and 28 to 16% for advantaged students). This decrease counters the hypothesis that an increase in enrolment would dilute the talent pool and lead to an increase in dropouts (as seen in Table 1, the Gymnasium GPA of bachelor’s students has remained stable). Another explanation could be that it was easier for dropouts to get a position in the labour market in the earlier period. However, if we look at the relative income position of students 13 years after enrolment (calculations from administrative data, not shown), nothing indicates that this is the case — the position of dropouts in the income hierarchy has remained stable from those enrolled in 1993 to those enrolled in 2003 (from 55th to 54th place in the income hierarchy). The decrease in dropouts could be linked to an increasing awareness at university institutions of the student experience and academic and social integration, and to a general discourse in society about students being more goal-oriented and determined, but this remains speculative, as the data do not allow for an investigation of such trends. Second, despite an overall decrease in bachelor dropout rates, the gap between advantaged and disadvantaged students is constant and large — students from disadvantaged backgrounds have roughly a 15 percentage point higher risk of dropping out than do advantaged students — even after adjusting for GPA, gender and ethnic status. One explanation for this gap could be that disadvantaged dropouts may be selected based on other traits, making them capable of securing good labour market positions despite bachelor departure. However, looking at bachelor students’ placement in the income hierarchy 13 years after enrolment reveals that the income of bachelor dropouts is not only lower than for degree holders, the income gap is also constant across social origin. In addition, disadvantaged dropouts earn less than advantaged dropouts (calculations from administrative data, not shown). In other words, dropouts from disadvantaged backgrounds do not secure incomes for themselves that would explain the surprisingly high dropout rate among these students.Footnote 7

Risk of bachelor dropout by enrolment year and social background (adjusted for Gymnasium GPA, gender and ethnic minority status). Note: See online appendix table 3 for model estimates

As discussed in the theory and knowledge section, sociological theory offers several explanations for the dropout patterns found in Fig. 3; how equally qualified students weigh future prospects differently (see Boudon, 1974), and how working-class students, not endowed with the same ‘college-going habitus’ (Grodsky & Riegle-Crumb, 2010), struggle more with the choice process and programme integration (e.g. Reay et al., 2003; Stuber, 2011). Nevertheless, the social class gap documented in Fig. 3 is remarkable, given that bachelor’s students from disadvantaged homes are a highly selected group of students, with a much smaller share reaching bachelor’s enrolment than privileged students.

It could be the case that the social gap in dropout rates is unevenly distributed across the GPA range — for instance, if the class gap is much greater among low-achieving students than among high-achieving students. Two studies suggest that a mechanism of compensatory advantage is at play (Contini et al., 2018; Herbaut, 2020): low-achieving students from privileged backgrounds are compensated for their low performance by their privileged parents, leading low-achieving students from advantaged backgrounds to be much less likely to dropout than low-achieving students from disadvantaged backgrounds. Figure 4 examines whether this is also the case in Denmark, by depicting dropout rates across the GPA range, based on estimates from a model interacting social background with Gymnasium GPA (adjusting for year of enrolment, gender and ethnic origin).

Risk of bachelor dropout by Gymnasium GPA (deciles, low to high) and social background (adjusted for enrolment year, gender and ethnic minority status). Note: Gymnasium GPA by deciles, with 1 being the bottom 10% and 10 the top 10%. See online appendix table 4 for model estimates

Unsurprisingly, students with low GPAs are much more likely to drop out than are students with high GPAs. However, the social class gap across most of the GPA range is the same: students from disadvantaged backgrounds are consistently more at risk of dropping out of a bachelor’s programme than advantaged students.Footnote 8 These estimates do not support the mechanism of compensatory advantage found in other studies.Footnote 9 This mechanism may work in other corners of the educational system or it may relate to different types of welfare regimes; this remains speculative however and should be properly examined through comparison of a large number of countries.

Obtaining a master’s degree

Next, I look at the risk of not obtaining a master’s degree for bachelor’s students, a particularly relevant question in the Danish setting, as bachelor’s degree holders in Denmark are entitled to continue into the consecutive master’s programme without having to apply (e.g. from a bachelor’s in sociology to a master’s in sociology).

Figure 5 shows the risk of not getting a master’s degree by social background for bachelor’s degree holders from 1993 to 2002 (year of bachelor’s enrolment, with status measured 12 years later ). Dealing with a group of students who have already successfully completed a bachelor’s degree, the social class gap in non-completion is expectedly smaller than it was for bachelor dropouts. Nevertheless, Fig. 5 displays a substantial difference in the risk of dropout by social origin. After completion of a bachelor’s degree, disadvantaged students are consistently around 10 percentage points more likely to leave a master’s programme than are advantaged students. As there historically has not been a labour market for bachelor’s degree holders in Denmark, it is unlikely that students leave assured that their bachelor’s title will secure them a labour market position. It is more probable that first-generation students face the same kind of risks and challenges as discussed in the bachelor dropout section — that is, for example, being more risk averse, experiencing dislocation and unfamiliarity or facing structural barriers.

Risk of not obtaining a master’s degree by enrolment year and social background (adjusted for Gymnasium GPA, gender and ethnic minority status). Note: See online appendix table 5 for model estimates

Finally, I examine students’ educational careers after dropout. As education is the prime transmitter of social positions in society, class differentials in failure to complete bachelor’s and master’s degrees are clearly pressing societal issues. Dropouts may compensate for their departure by ending up with other kinds of educational qualifications, and there could also be a social gradient in what kind of qualifications these dropouts eventually achieve. Figure 6 shows the likelihood of ending up with qualifications at a higher level than the bachelor’s degree 12 years after bachelor dropouts, for disadvantaged and advantaged students, respectively.

Probability of ‘dropping-up’ (upwardly mobile status) for bachelor dropouts by social background (adjusted for Gymnasium GPA, gender and ethnic minority status). Note: See online appendix table 6 for model estimates

While most bachelor dropouts eventually finish with a degree or diploma at a lower educational level (VET programme, business academy, university college), a substantial share end up with qualifications at the post-bachelor’s level, but with a clear social gradient. More bachelor dropouts from advantaged backgrounds end up with post-bachelor (master’s) qualifications (31%) than do bachelor dropouts from disadvantaged backgrounds (13%). For the privileged students, ‘dropping-up’ can be understood as a fall-back entry route to the university master’s or PhD degree needed to avoid downward mobility. In that sense, dropping up can be understood as social status correction, as a mechanism of ‘compensatory advantage’ (Bernardi, 2014) where privileged students are compensated by background privileges and maintain their social positions, despite having initially dropped out of a bachelor’s programme.

Conclusion

While the bulk of research on inequality of educational opportunity focuses on access to education, this paper has zoomed in on social inequality after enrolment in higher education by examining class differentials in student departure from bachelor’s programmes. Using high-quality administrative data, I have looked at the educational trajectories of bachelor’s students’ cohorts from the introduction of the bachelor’s degree in Denmark in 1993 up through 2006. Contrary to my two first hypotheses, dropout rates have decreased across the period, and I have found large and constant class gaps in bachelor dropout from 1993 onwards, even after adjusting for GPA from the higher education-preparatory ‘Gymnasium’. Disadvantaged students are about 15 percentage points more likely to leave a bachelor’s programme than advantaged students are. The social gradient even shows up at the master’s level, with students from disadvantaged backgrounds being roughly 10 percentage points more likely to not obtain a master’s degree than advantaged students. The size of these class gaps is remarkable given that these young people have made it past several educational transitions to reach the highest level in the educational system and given that these departures are taking place in a country with relatively low economic inequality, with no tuition fees and with generous government grants for all higher education students. Importantly, the class gap is constant across the GPA range, with no support of the fourth hypothesis that advantaged students with low GPAs would be compensated by their privileged background and have low dropout rates. However, the same hypothesis is supported in another way, as dropouts from privileged backgrounds more often end up with academic qualifications in the long run than do disadvantaged students. For these privileged students, ‘dropping-up’ can be understood as a mechanism of social status correction, as a contingency plan for securing the academic qualifications needed to maintain a middle-class social position.

The sociological literature on student trajectories and experiences highlights several possible factors contributing to increased student departure for disadvantaged students. First, disadvantaged students may face structural barriers not experienced by privileged students: for instance, financial concerns, residential challenges, family obligations and labour market prospects may lead more disadvantaged students to depart. Disadvantaged students may feel dislocated as they meet an academic environment not familiar to them, as such environments privilege social and cultural codes well-known to students having grown up in an environment with high levels of cultural capital. Such an upbringing gives students a home advantage and prepares them for university studies — exhibiting a college-going habitus (Grodsky & Riegle-Crumb, 2010). Disadvantaged students, growing up in a social environment unfamiliar with the education system and university studies, might opt out of university programmes even though they are just as qualified as their privileged peers due to ‘secondary effects’ (Boudon, 1974), the non-cognitive skills that lead children from different social origins to differ in their risk aversion behaviour, even if they have the same academic qualifications. As such, disadvantaged students may find more pros than cons in programme departure than their advantaged counterparts (viewed in the light of information on, e.g. changing labour market prospects or income levels). All of these mechanisms pertain to the social background and home environment of the students and work together to produce increased dropout risks for disadvantaged students.

It is out of the scope of this paper to examine the role of institutions and programmes in actively providing an inclusive study environment. However, and in support of the third hypothesis, the data analysed in this paper suggest that their role may be limited and that dropout rates may be more linked to pre-entry characteristics, such as motivation, determinedness, preferences or expectations (e.g. when working-class students stick with programmes because they are applied oriented and not necessarily because they are particularly inclusive). Ideally, quantitative data uncovering dropout patterns by social origin should be supplemented with ethnographic studies of student experiences by social class, examining what characteristics set leavers apart from those who stay when both groups are equally qualified. As other studies have found that educational expansion in higher education is not necessarily a remedy for narrowing the class gap in educational attainment (Breen & Jonsson, 2005), scholars and professionals should focus more on how to keep disadvantaged students from leaving higher education.

Notes

I use the newest data available, but do not include cohorts enrolled later than 2006, to be able to follow students well after their enrolment year.

As robustness checks, I also ran models of dropout status at years 6 and 10 after bachelor enrolment; these models produced the same results as those presented in this paper.

I choose to model dropout by linear probability models over event history models, because (1) my primary aim is simply to gauge the social gap in non-completion and not the timing of events (i.e. when dropout occurs), and (2) administrative data measure the exact occurrence of dropout poorly (as students may be registered as enrolled long after they have dropped out).

Average predicted probabilities from logit models yield virtually identical results as the ones presented here.

Not shown in Table 1, most of those enrolled in bachelor’s programmes have attended the general Gymnasium (73%), with a smaller share having chosen the technical/business-oriented track (13%) and a different type of the general Gymnasium (‘HF’, 12%) catered towards mature students (on average 23 years old when they obtain their diploma). These students are generally from lower educated homes than students from the general Gymnasium. HF students are on average 20% more likely to dropout than STX students are, even though their GPA is fairly similar (7.9 and 8.1, respectively).

This assumption is supported by the fact that the University of Roskilde is the institution with the highest share of bachelor’s degree holders leaving their institution to pursue their master’s degree elsewhere.

Although we cannot deduce that leavers would have enjoyed the same income as stayers, had they finished their degree, the income gap is unlikely to be attributable solely to selection; that is, dropouts would have some unobservable traits leading them to have lower economic returns, regardless of whether or not they obtained a degree.

Disadvantaged students with a GPA in the top decile have a very high dropout rate, suggesting that this small group will be heavily selected on unobservable traits, which may lead them, for example, to venture successfully into the labour market without a degree. It could also be the case that top performing disadvantaged students enrol in highly selective programmes where they are most likely to feel culturally out of place and hence dropout more (I thank an anonymous reviewer for this excellent point).

This pattern holds true even if we distinguish between different tracks in the higher education-preparatory upper secondary school (general, business, technical and higher preparatory track).

References

Allensworth, E. M., & Clark, K. (2020). High school GPAs and ACT scores as predictors of college completion: Examining assumptions about consistency across high schools. Educational Researcher, 49(3), 198–211.

Archer, L., & Hutchings, M. (2000). “Bettering yourself”? Discourses of risk, cost and benefit in ethnically diverse, young working-class non-participants’ constructions of higher education. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 21(4), 555–574.

Argentin, G., & Triventi, M. (2011). Social inequality in higher education and labour market in a period of institutional reforms: Italy, 1992-2007. Higher Education, 61, 309–323.

Bar Haim, E., & Shavit, Y. (2013). Expansion and inequality of educational opportunity: A comparative study. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 31, 22–31.

Bernardi, F. (2014). Compensatory advantage as a mechanism of educational inequality. Sociology of Education, 87(2), 74–88.

Bernstein, B. (1990). Class, codes and control: Vol. 4. The structuring of pedagogic discourse. Routledge.

Boudon, R. (1974). Education, opportunity and social inequality. Changing prospects in Western society. John Wiley & Sons.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). Distinction. A social critique of the judgement of taste. Routledge.

Bourdieu, P. (1996). The state nobility: Elite schools in the field of power. Polity Press.

Bourdieu, P., Passeron, J.-C., & Martin, M. d. S. (1994). Academic discourse: Linguistic misunderstanding and professorial power. Stanford University Press.

Breen, R., & Goldthorpe, J. H. (1997). Explaining educational differentials. Rationality and Society, 9(3), 275–305.

Breen, R., & Jonsson, J. O. (2005). Inequality of opportunity in comparative perspective: Recent research on educational attainment and social mobility. Annual Review of Sociology, 31, 223–243.

Christie, H., Tett, L., Cree, V. E., Hounsell, J., & McCune, V. (2008). “A real rollercoaster of confidence and emotions”: Learning to be a university student. Studies in Higher Education, 33(5), 567–581.

Contini, D., Cugnata, F., & Scagni, A. (2018). Social selection in higher education. Enrolment, dropout and timely degree attainment in Italy. Higher Education, 75, 785–808.

Doren, C., & Grodsky, E. (2016). What skills can buy: Transmission of advantage through cognitive and noncognitive skills. Sociology of Education, 89(4), 321–342.

Goldrick-Rab, S. (2006). Following their every move: An investigation of social-class differences in college pathways. Sociology of Education, 79(1), 61–79.

Goldrick-Rab, S., & Pfeffer, F. T. (2009). Beyond access: Explaining socioeconomic differences in college transfer. Sociology of Education, 82(2), 101–125.

Goldthorpe, J. H. (1996). Class analysis and the reorientation of class theory: The case of persisting differentials in educational attainment. British Journal of Sociology, 47(3), 481–505.

Grodsky, E., & Riegle-Crumb, C. (2010). Those who choose and those who don’t: Social background and college orientation. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 627(1), 14–35.

Haveman, R., & Wilson, K. (2007). Access, matriculation, and graduation. In S. Dickert-Conlin & R. Rubenstein (Eds.), Economic inequality and higher education (pp. 17–43) Russell Sage Foundation.

Herbaut, E. (2020). Overcoming failure in higher education: Social inequalities and compensatory advantage in dropout patterns. Acta Sociologica, online first: June 2.

Holm, A., & Jæger, M. M. (2011). Dealing with selection bias in educational transition models: The bivariate probit selection model. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 29(3), 311–322.

Hovdhaugen, E. (2009). Transfer and dropout: Different forms of student departure in Norway. Studies in Higher Education, 34(1), 1–17.

Jæger, M. M., & Holm, A. (2007). Does parents’ economic, cultural, and social capital explain the social class effect on educational attainment in the Scandinavian mobility regime? Social Science Research, 36(2), 719–744.

Johnes, G., & Mcnabb, R. (2004). Never give up on the good times: Student attrition in the UK. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 66(1), 23–47.

Karlson, K. B. (2019). College as equalizer? Testing the selectivity hypothesis. Social Science Research, 80, 216–229.

Larsen, M. S., Kornbeck, K. P., Kristensen, R., Larsen, M. R., & Sommersel, H. B. (2013). Dropout phenomena at universities: What is dropout? Why does dropout occur? What can be done by the universities to prevent or reduce it? Danish Clearinghouse for Educational Research.

Mare, R. D. (1981). Change and stability in educational stratification. American Sociological Review, 46(1), 72–87.

Mare, R. D. (1993). Educational stratification on observed and unobserved components of family background. In Y. Shavit & H.-P. Blossfeld (Eds.), Persistent inequality: Changing educational attainment in thirteen countries (pp. 351–376). Westview Press.

Mood, C. (2009). Logistic regression: Why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it. European Sociological Review, 26(1), 67–82.

Narayan, A., Van der Weide, R., Cojocaru, A., Lakner, C., Redaelli, S., Gerszon Mahler, D., Ramasubbaiah, R. G. N., & Thewissen, S. (2018). Fair progress?: Economic mobility across generations around the world. World Bank Group.

OECD. (2018). A broken social elevator? How to promote social mobility. OECD Publishing.

Reay, D. (2003). A risky business? Mature working-class women students and access to higher education. Gender and Education, 15(3), 301–317.

Reay, D., David, M., & Ball, S. (2001). Making a difference?: Institutional habituses and higher education choice. Sociological Research Online, 5(4), 14–25.

Reay, D., Crozier, G., & Clayton, J. (2009). “Strangers in paradise”? Working-class students in elite universities. Sociology-the Journal of the British Sociological Association, 43(6), 1103–1121.

Shavit, Y., Arum, R., & Gamoran, A. (2007). Stratification in higher education. A comparative study. Stanford University Press.

Stuber, J. M. (2011). Inside the college gates: How class and culture matter in higher education. Lexington Books.

Thomsen, J. P. (2012). Exploring the heterogeneity of class in higher education. Social and cultural differentiation in Danish university programmes. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 33(4), 565–585.

Thomsen, J.-P. (2015). Maintaining inequality effectively? Access to higher education programmes in a universalist welfare state in periods of educational expansion 1984-2010. European Sociological Review, 31(6), 683–696.

Thomsen, J.-P., Hedman, J., Helland, H., Bertilsson, E., & Dalberg, T. (2017). Higher education participation in the Nordic countries 1985-2010—a comparative perspective. European Sociological Review, 33(1), 98–111.

Troelsen, R., & Laursen, P. F. (2014). Is drop-out from university dependent on national culture and policy? The case of Denmark. European Journal of Education, 49(4), 484–496.

Ulriksen, L. (2009). The implied student. Studies in Higher Education, 34(5), 517–532.

Vignoles, A. F., & Powdthavee, N. (2009). The socioeconomic gap in university dropouts. B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 9(1), 1–36.

Wilbur, T. G., & Roscigno, V. J. (2016). First-generation disadvantage and college enrollment/completion. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 2, 1–11.

Winterton, M. T., & Irwin, S. (2012). Teenage expectations of going to university: The ebb and flow of influences from 14 to 18. Journal of Youth Studies, 15(7), 858–874.

Zarifa, D., Kim, J., Seward, B., & Walters, D. (2018). What’s taking you so long? Examining the effects of social class on completing a bachelor’s degree in four years. Sociology of Education, 91(4), 290–322.

Zhou, X. (2019). Equalization or selection? Reassessing the “meritocratic power” of a college degree in intergenerational income mobility. American Sociological Review, 84(3), 459–485.

Availability of data and material

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available, as only researchers employed at Danish authorized research institutions, for reasons of security, can get access to administrative data at Statistics Denmark.

Code availability

Data was analysed in Stata and coding files are available upon request from the author.

Funding

This research was supported by the Danish Council for Independent Research, grant no: 4180-00054A.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 64 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thomsen, JP. The social class gap in bachelor’s and master’s completion: university dropout in times of educational expansion. High Educ 83, 1021–1038 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00726-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00726-3