Abstract

In this paper, we provide a comprehensive picture of social selectivity in higher education in Italy by focusing on enrolment and two alternative indicators of success: retention and timely completion. The existing literature has shown that young individuals of disadvantaged backgrounds have lower enrolment probabilities and higher chances of withdrawal. This paper analyses the size and features of this cumulative disadvantage, shaping the chances of high-school leavers of eventually attaining the university degree. We analyse whether social background inequalities are stronger at enrolment or at later outcomes, and how these inequalities vary with previous schooling experience. We confirm previous evidence that disadvantaged groups with respect to enrolment are also disadvantaged on persistence, add new findings on timely completion and show that cumulative inequalities are very strong. Inequalities are strongest among students holding technical and vocational high-school qualifications and weakest among well-performing students from lyceums. In addition, we examine the role of labour market conditions and whether they explain geographical differences. Enrolment, retention and timely completion probabilities appear negatively related to local youth unemployment rates, suggesting that with poor labour market prospects, individuals lose motivation and reduce their engagement in education.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Despite the large expansion of the educational systems and the rising participation to higher education occurred in the past decades, strong social background inequalities in educational attainment are persisting in most Western countries. The relation between family background and schooling choices is particularly strong in Italy, even in comparison to other highly tracked educational arrangements like Germany and Netherlands (Contini and Scagni 2013; Jackson 2013). This occurs in spite of the openness of the schooling system that liberalises university access to all students with any upper secondary school degree and does not impose ability barriers neither at the transition to upper secondary nor tertiary education.

The reduction of inequalities in access and completion of higher education and the increase in the number of young people with higher education degrees are strategic targets of the EU. However, despite the rising participation that took place in the last decades, the share of young individuals with a higher education qualification in Italy is still around 24%, substantially less than in most EU countries (Eurostat 2015). This critical outcome is not due to low participation rates.Footnote 1 Instead, the low share of university graduates in Italy seems to be the result of high non-completion probabilities (ANVUR 2016). In addition, the average time to degree attainment is much longer than the institutional length of the courses (Almalaurea 2015).

Against this background, the general aim of this paper is to study social selectivity in the Italian university system operating from university enrolment thereon, on top of inequalities already established in previous stages of schooling. By exploiting the national Survey on High-School Graduates held in 2011 on students who attained the upper secondary school degree in 2007, at the onset of the economic crisis, we analyse higher education enrolment, together with two alternative dimensions of success: retention (vs. dropout) and timely completion. While the first two were the object of previous contributions, some of which were exploiting earlier waves of this survey, to our knowledge this is the first attempt to study timely completion in Italy with national-level data.

We already know from the existing literature that both the probability of university enrolment and retention differ substantially across social backgrounds. We also acknowledge that disadvantaged groups in one dimension are also disadvantaged in the other. Yet, the size and features of this cumulative disadvantage—that shapes the probability of high school leavers of eventually attaining the university degree—has never been analysed explicitly. Moreover, from the existing literature, it is unclear whether social background inequalities are stronger at enrolment or at later outcomes, nor if these inequalities and their size vary with the previous schooling experience.

Our paper aims at filling this gap, by addressing questions like ‘when considering (for example) well performing diplomats in the vocational upper secondary track, how do individuals from different social backgrounds differ in the actual probabilities of entering university and not dropping out? Are lower status young individuals more disadvantaged at entry, or is the disadvantage stronger on retention? Are these results similar to those applying to (for example) well performing diplomats in the academic track?’ The policy relevance of these questions is evident, as better knowledge of the stage students with different schooling and family backgrounds suffer most could help targeting interventions for the reduction of inequalities in higher education. We will show that, on a whole, inequalities tend to be stronger between young individuals with weak prior schooling profiles. Moreover, while differentials in enrolment probabilities are substantial for most schooling backgrounds (with the exception of the best students from the academic track), differences in dropout probabilities are far more important among weak students.

The second question we address is whether social background inequalities in two different success indicators—retention and timely completion—are similar. This need not to be the case because in Italy, students not making substantial progress in their degree course are not pushed out of the system. Some students take a long time to attain the degree. These individuals will contribute to the retention figures, but will not enter the timely completion ones. Other students remain in the university system for many years, but eventually withdraw before attaining the degree. Hence, those not dropping out within a few years after enrolment will not necessarily graduate. In this perspective, retention is merely a signal of the wish to attain the qualification, while timely completion indicates that the goal has been achieved—and in a satisfactory time span. Our analyses show very clearly that social inequalities in retention and timely completion do not follow the same pattern.

Third, given the long-standing North–South societal divide existing in Italy, we focus on geographical differences in enrolment, dropout and timely completion probabilities. We analyse the relation between labour market conditions and higher education outcomes and investigate whether labour market conditions play a role in explaining geographical inequalities. Our results indicate that enrolment, retention and timely completion probabilities are lower in areas with high youth unemployment rates, suggesting that when labour market prospects are poor, attitudes of discouragement prevail. However, labour market conditions explain the geographical variability in the outcomes only to a limited extent.

The paper is structured as follows. In the Background section we review the theoretical and empirical background on higher education choices and outcomes and the findings on Italy. We then describe the Italian educational system, data, methods and variables. We then present our results: firstly, we analyse separately the enrolment, retention and timely completion probabilities; secondly, we relate enrolment and retention probabilities; thirdly, we relate retention and timely completion probabilities; fourthly, we analyse the role of labour market conditions. Conclusions follow.

Background

A common interpretation of socioeconomic differences in educational choices in the sociological literature refers to the theory of cultural reproduction (Bourdieu and Passeron 1990), according to which children in the highest classes are advantaged in gaining educational credentials due to the possession of cultural capital. Rational action (Breen and Golthorpe 1997) is a competing explanation. In this view, individuals choose among educational options by evaluating costs and benefits and the perceived probabilities of successful outcomes. Individuals aim at reducing the risk of downward intergenerational mobility, so given performance, higher-class children make more ambitious educational investments. These mechanisms provide a rational choice account of the evidence that social class differentials operate via performance and net of performance (Boudon 1974). Clearly, performance differentials at the transition to higher education are originated also by social selection occurring at earlier stages of schooling. Hence, research on socioeconomic inequalities in higher education should acknowledge the different selection processes to which students of different backgrounds are exposed.

The economists’ explanations of educational inequalities, originated by Becker’s human capital theory, also refer to rational choices: individuals take decisions by comparing direct and indirect costs of education, in particular, tuition fees and foregone earnings, with benefits in terms of future wages. Lower income individuals make less prestigious choices because they are more risk averse (for evidence on Italy, see Checchi et al. 2014) or because of credit constraints. The role of credit constraints and financial hardship on enrolment decisions was addressed in particular in the USA, with mixed results. Carneiro and Heckman (2002) find that what matters is not current income, but the long-run factors associated with higher income families, providing better quality education and better environments that foster cognitive and non-cognitive skills.

There is widespread evidence of socioeconomic differentials also in retention and completion probabilities. In the first place, students from high social background are advantaged because they have better prior academic preparation. Tinto (1975) identifies students’ academic and social integration as major determinants of completion in higher education. Robin and Naylor (2001) focus on academic preparedness, and Arulampalam et al. (2005) highlight the role of individual’s prior performance relative to that of the other students. Stinebrickner and Stinebrickner (2014) show that students update their beliefs on their own ability over time, and this process plays a role in dropout decisions. However, inequalities may exist also when comparing individuals with similar schooling history and prior performance. Vignoles and Powdthavee (2009) find that, even after controlling for personal characteristics, prior achievement and university features, dropout probabilities in the UK are larger for the low social strata. Similar results are reported for the USA (Bowen et al. 2009). Other potential explanations are related to information asymmetries on the higher education system or to credit constraints (Stinebrickner and Stinebrickner 2008), tuition fees and financial aid (Dynarski 2003). Supply side factors may also matter since the choice of the institution depends on family background and dropout and timely completion probabilities vary with institutions’ characteristics (Bound et al. 2010; Kurlaender et al. 2014).

According to theoretical predictions, bad economic conditions should increase education participation rates by reducing the opportunity costs of studying. For this reason, high unemployment rates may also contribute to decreasing dropout rates. However, the lack of income may cause financial difficulties and foster dropout. Yet, poor labour market prospects may affect motivation and produce discouragement, contributing to reduce both enrolment and retention rates. Hence, theoretical predictions are ambiguous. In analysing the effects of the recent economic downturn in USA, Hillman and Orians (2013) find counter-cyclical effects on university and community college enrolment. By exploiting territorial variability of unemployment in the UK, Smith and Naylor (2001) found an increasing dropout risk with higher unemployment. The existing evidence on Italy is also inconclusive.

Empirical evidence on Italy

Given the absence of longitudinal administrative data archives on schooling careers embracing upper secondary and tertiary education, the literature on social inequalities in higher education enrolment has relied extensively on survey data. Moreover, administrative data do not provide information on family background. A widely used data source is the Survey of High-School Graduates (SHSG), carried out periodically on students completing secondary school in a given year and collecting retrospective data on educational and labour market experiences within a 3-year time span. Argentin and Triventi (2011) examine intergenerational transmission of educational attainment over time and report slightly decreasing but persisting inequalities. There is evidence that good students from disadvantaged families are subject to constraints in their educational decisions on university enrolment (Cappellari and Lucifora 2009); in particular, the enrolment probability of weaker students (from non-academic tracks and of low social background) seems to be more sensitive to changes in university costs and quality (Pigini and Staffolani 2016).

Research on university dropout also relies heavily on SHSG. Using older waves of this survey, the existing literature reports substantial differentials related to family background and prior schooling (Di Pietro 2004; Di Pietro and Cutillo 2008; Cingano and Cipollone 2007; Argentin and Triventi 2011). Similar results are obtained by Aina (2013), analysing the timing of dropout with ECHP data with survival modelling. Using administrative data from large universities, other studies analyse dropout and change of programs with competing risks (Clerici et al. 2014) or latent class modelling (Belloc et al. 2010). These studies highlight the importance of prior schooling and the role played by household income, and report different patterns by field of study and degree programs. Carrieri et al. (2015) analyse the influence of admission policies on retention and find that a stronger selection at entrance considerably reduces dropout risks, while Mealli and Rampichini (2012) and Agasisti and Murtinu (2016) show that grants contribute preventing dropout.

Research on degree completion is limited. The SHSG has provided little ground to study completion because in the previous waves, respondents were interviewed 3 years after the diploma; since only few students attain their university degree perfectly on time, it was not possible to study completion (this is no longer the case, as in the 2011 wave individuals were interviewed after 4 years). Using administrative data, Aina et al. (2011) highlight the role of individual and family factors, showing that weak labour market prospects contribute to lengthening time to degree. Focusing on single institutions, Garibaldi et al. (2012) observe a negative relation between tuition costs and timely completion probability, while Agasisti and Murtinu (2016) find that grants tend to reduce time to degree.

The few papers on the role of labour market conditions on enrolment and dropout in Italy reach inconclusive evidence. Focusing on the territorial variability of labour market indicators, Di Pietro (2006) finds a negative effect of unemployment on dropout rates. Instead, Di Pietro (2004) reports a negative effect on enrolment and no effect on dropout, whereas in Di Pietro and Cutillo (2008), the effect is insignificant on dropout but positive on enrolment. Ghignoni (2017) examines the effect of the recent economic crisis on dropout concluding that the observed slight reduction of the aggregate dropout probability is not due to changes in individual behaviour but to differences in the composition of university students.

The Italian educational system

Formal education starts at age 6 and is compulsory until age 16. Children attend eight years of comprehensive schooling, five of primary education and three of lower secondary education. Lower secondary school ends at age 14 with a national examination, after which children choose between a number of upper secondary school programs, broadly classified into academic, technical and vocational tracks. The different educational programs differ substantially in curricular content and academic standards. Lyceums (academic track), widely considered the natural path to university, are generally the most demanding. Technical institutes provide intermediate level education, with substantial academic content, but are more labour market oriented. Vocational institutes, alongside general education, offer school-level training for low-level technical jobs. The high school diploma (maturità) is attained after 5 years and gives access to university.Footnote 2 The Italian schooling system is mainly public: only a small share of the student body attend private schools. Private institutions at the upper secondary level often have a remedial character, hosting affluent children who experienced school-year failures and offering lower quality instruction than public schools (Bertola et al. 2008).

In the Italian educational system, there are no ability-related admission restrictions, neither at the transition between lower and upper secondary school nor at the transition to tertiary education. All students possessing a 5-year high school diploma have unconditional access to university (although for some fields enrolment is limited and regulated by admission tests). Despite this formal openness, educational inequalities in the choice of the high-school track and in university access are extremely large in Italy, even compared to other highly tracked educational systems such as Germany and Netherlands (Contini and Scagni 2013; Jackson 2013). This result might be actually fostered by the absence of access barriers because choices are entirely on part of students and families, and aspirations differ across social backgrounds (Checchi and Flabbi 2007; Contini and Scagni 2011).

In the Italian higher educational system, there is no formal divide between university programs and polytechnic higher education.Footnote 3 The university system is mainly public, but there are also a few prestigious private institutions. Whatever the institution delivering the degree, the qualification has the same ‘legal value’. Hence, although different studies (Agasisti 2009; Cattaneo et al. 2017) show that reputation is relevant in attracting students, its role is less important in Italy than in other countries with more differentiated university systems. Excluding the law and medical schools and few other degree programs still lasting 5–6 years, since the implementation of the EU ‘Bologna process’ in 2001, students attend a 3-year bachelor program followed by a 2-year master program.

Students choose a field of study (for example economics, physics or philosophy) and have limited leeway on the curriculum. Students may retry examinations if they fail or get a poor grade. There are no standard, nationwide limits to time-to-degree (although some institutions have set some mild restrictions), so students often take much longer than the official study length.Footnote 4

Tuition costs in public universities have limited variation across institutions and fields of study, although there are significant geographical differences (Cattaneo et al. 2017).Footnote 5 University fees are relatively low and depend on per-capita household income; therefore, it is unlikely that low-income students will not enrol because of direct costs of education. Financial aid in the form of grants is limited.Footnote 6 Subject to budget constraints, some scholarships are provided to low-income students obtaining a given amount of credits and a given minimum grade point average.

Data, methods and variables

We employ the Survey on High-School Graduates 2011, interviewing graduates in 2007. This survey provides information on educational and labour market histories up to 4 years from school completion, prior schooling and family background. Our interest rests on the behaviour of young individuals following a relatively regular schooling career, so we analyse individuals aged 21 or less at high school completion. Given the long time span and the retrospective character of the data collection, the questionnaire focuses on first and current spells in education and work, not enabling to fully reconstruct the timing of the events and unambiguously relate educational and working careers. Moreover, the question wording does not allow identifying precisely the moment of dropout or degree completion. In this light, we analyse the occurrence of the events of interest within the observed time span, rather than the timing of the events.

We analyse university enrolment together with two distinct educational outcomes: retention (vs. dropout) within 4 years from enrolment and, limited to those enrolled in 3-year programs, timely completion, defined as degree attainment within 4 years.Footnote 7 Let E be the binary variable indicating university enrolment, D the binary variable indicating dropout from the university system and C the binary variable indicating timely degree completion for those enrolled in a 3-year program. As a first step, we model P(E = 1), P(D = 1|E = 1) and P(C = 1|E = 1) with separate logistic regression, with the aim to characterise the determinants of each event of interest, and the direct and indirect roles—via prior schooling and university features—played by social origin. In this perspective, our models will include progressively four sets of explanatory variables describing sociodemographic characteristics, prior schooling, university features and contextual factors (see below).

The question we address is: How do enrolled students from different family backgrounds with the same prior schooling history behave? Differently from many scholars from the economics of education, we do not estimate the dropout probability accounting for individual-specific unobserved factors (Montmarquette et al. 2001, Di Pietro 2004 and Di Pietro and Cutillo 2008 use bivariate-probit models while Cingano and Cipollone 2007 and Ghignoni 2017 use sample selection models). We do not use these models because we are not interested in estimating the effect of social origin net of all other observable and unobservable individual characteristics. In our view, the comparison between individuals of different family backgrounds with identical prior schooling history and identical unobserved personal traits is not particularly salient because it is very unlikely that individuals of different family backgrounds with identical innate ability or motivation will experience identical (prior) educational careers. The rationale is simple: to compensate for the lower family endowments, students of low social origin must be more motivated or brighter. If they have exactly the same unobserved traits of students of more advantaged backgrounds, it is very unlikely that they will reach the same results in terms of prior schooling, unless they are very lucky (in formal terms, they get by chance a large value of the independent component in the error term). Hence, it would be unusual to find individuals with the same prior schooling but different social origin if they had the same motivation or innate ability (see Online Appendix 1 for a detailed discussion).

In a second step, we examine the evidence on enrolment and dropout jointly. To the extent that not all students entering higher education ultimately attain the degree, this approach seems more salient than focusing on enrolment per se. We compute the joint probabilities of enrolling and not withdrawing, and then plot the estimates of the retention probability P(D = 0|E = 1) against the enrolment probability P(E = 1) for subgroups of young individuals defined by sociodemographic characteristics and prior schooling. This simple strategy allows visualising how these probabilities are related and the degree to which disadvantaged groups with respect to university enrolment are also disadvantaged with respect to persistence. We analyse at what stage—enrolment or retention—the effects of social background are stronger, as well as their heterogeneity across student profiles with different previous schooling histories.

Further, focusing on students first enrolled in 3-year programs (for whom we may observe completion), we examine the relation between the two higher education indicators of progress—retention and timely completion—by plotting the estimates of P(D = 0|E = 1) and P(C = 1|E = 1). This approach allows making a qualitative assessment of whether social origin affects retention and timely completion in a similar way, or if these indicators behave in substantially different ways in terms of social selectivity.

To investigate territorial inequalities, we perform all the analyses by macro-area. In addition, we exploit the territorial variation of youth unemployment rates and re-estimate the models to investigate the relation between labour market conditions and higher education outcomes and analyse whether labour market conditions play a role in explaining the observed geographical differences across the country.

Variables

Family background

Family background is operationalised by parental education and class. We define parental education as the highest educational level of mother and father. Parental class is defined similarly, according to the level of occupation. We use the restricted EGP (Erikson, Goldthorpe and Portocarero) classification that distinguishes between service class (managers and professionals), intermediate and working class (manual and unskilled workers).Footnote 8

Demographic variables

Gender is included because it is an important determinant of educational decision-making (e.g. Beattie 2002; Cattaneo et al. 2016). To account for the well-known territorial divide, we also include the macro-area of residence during secondary school (North, Centre and South).

Prior schooling characteristics

We consider the upper secondary school track (academic, technical, vocational), whether the institution was public or private, and marks obtained at the lower (A–D) and upper secondary school final examinations (60–100). We also consider whether the student has failed some subjects or repeated a school year and whether she has changed institution during upper secondary school (usually students change school if they do not meet performance standards; Contini and Triventi 2016).

University-related variables

We consider characteristics of the university and educational programs: field of study, degree length, macro-area of the university, whether respondents have migrated out-region to attend university and whether they were working during the first academic year.

Contextual variables

On the demand side, we include the youth unemployment rate at provincial level in 2007 to analyse the effect of labour market conditions on the tertiary educational outcomes. On the supply side, and limited to the enrolment model, we include a measure of diversity of the degree programs in the area of residence, the number of different fields of study and the index of provincial attractiveness (PA) proposed by Dotti et al. (2013) based on university enrolment inflows and outflows.Footnote 9

First results

The share of high school graduates who enrolled at university within 4 years after graduation in our sample is 65.2%, the majority of which enrolled immediately after high school (87.6%). Among students enrolling immediately after graduation, those reporting withdrawal before degree completion are 12.3%.This share does not include transfers to other degree programs (10.5%) (Table 1).

The bivariate relation between university outcomes and individual characteristics is shown in Table 2. The first two columns describe the distributions of variables among high school graduates and university entrants. The last three columns report the proportion of enrolled, dropouts and timely degree completions. These findings are consistent with the results in the literature on the role of social background, gender and prior schooling careers. Young individuals with low educated parents or in the working class experience a cumulative disadvantage: they have much lower enrolment probabilities, and even if they do enrol, they have higher chances of dropping out and lower chances of attaining the degree within the institutional time.

Relevant geographical differences exist only in the timely completion share of students, which is much smaller among southerner’s students. Students enrolled in southerner’s institutions display higher dropout rates and lower timely completion rates. Moreover, movers (defined as those enrolled in an out-region institution) display better outcomes than stayers.

We now move to multivariate modelling. We begin by estimating models including only sociodemographic characteristics (model IA). Since for the enrolment and dropout models we find a significant interaction effect between gender and geographical area, we also report separate effects for gender given area and area given gender (model IB). To evaluate family background effects operating at the transition to tertiary education, we add prior schooling variable, in themselves the result of a previous strong socially selective process (model II). Finally, in the dropout and timely completion models, we also include mediator variables describing university and contextual factors (model III). We express results in terms of Average Marginal Effects (AME), summarised in Tables 3, 4 and 5 because, differently from logit regression coefficients, they are comparable across nested models allowing to assess direct and indirect effects (Wooldridge 2002).Footnote 10

Gender

Females have higher enrolment and lower dropout probabilities. On average, their advantage over males is 12.9 percentage points (p.p.) in the enrolment probability (Table 3, model IA) and 5 p.p. in the dropout probability (Table 4, model IA). When introducing an interaction term between gender and area, we acknowledge that these gender differences vary across macro-area (Tables 3 and 4, model IB). Females are more likely to enter university everywhere, but this advantage is particularly marked in Southern Italy, where their advantage over males is 16 p.p. as compared to 9 p.p. in the North. The gender gap is entirely explained by the more proficient schooling career of girls in the North, whereas in the rest of the country girls remain substantially more likely to enrol, even after controlling for prior schooling (Table 3, model II). Females have lower dropout chances than males, but this gap is larger in the North (almost 7 p.p.) than in the South (3–4 p.p.). Moreover, the gender differential in dropout is fully explained by prior schooling and university variables in the Centre-South, but not in the North. Girls are more likely to attain the degree within 4 years than males (by 9 p.p.), but this gap is fully explained by prior schooling and the characteristics of universities and degree programs (Table 5, models IA, II and III).

Geographical area

Geographical differences in enrolment rates given prior schooling are small for females and substantial for males (Table 3, model II): in the Centre and South, males have lower enrolment probabilities than their Northern peers (4–5 p.p.). Dropout probabilities are larger in the Centre-South, especially for females when controlling only for prior schooling; however, given university variables, dropout chances increase substantially for students from the Centre while we find no substantial differences between North and South (Table 4, models II–III). Timely completion is much more likely in the North: given prior schooling and university variables, the average probability difference between North and South is 18 p.p. (Table 5, model III).

Social background

Social background inequalities are large on all outcomes. Parental education and class play similar roles on enrolment: on average, the advantage of the highest strata over the lowest one is 25 p.p. for each dimension (Table 3, model IA). Hence, when comparing a youngster of highly educated parents in the service class and one with lowly educated parents in the working class, the gap reaches 50 p.p. Social background inequalities exist and remain substantial even conditional on prior schooling (before higher education): the advantage of the highest over the lowest stratum is nearly 8 p.p. on parental education and 12 p.p. on social class (Table 3, model II). Family background also strongly affects the dropout probability, but parental education plays a stronger role than class. This pattern does not change qualitatively when adding university variables (Table 4). Parental education has also an effect on the timely completion probability (+4.5 p.p. between the lower secondary and tertiary level), while the effects of parental class is not statistically significant (Table 5).

Prior schooling

Prior schooling characteristics are the strongest predictors of all educational outcomes. Students from lyceums have considerably higher enrolment, retention and timely completion probabilities than those with a technical diploma, and the differential with vocational schools graduates is even larger. On average, the enrolment probability of a lyceum graduate is 55 p.p. higher than that of a student from the vocational track and 29 points higher than that of a student from the technical track (Table 3, model II). Corresponding differences in the dropout probability are approximately 25 and 10 p.p., in the timely completion probability 20 and 12 (Tables 4 and 5). The final examination marks in high school and middle school are also highly relevant. Students previously attending private schools or having experienced school failures (repetition or debts) do not differ much from other students in terms of enrolment behaviour, but have much higher chances of withdrawing and lower chances of timely degree attainment.

University variables

University variables are included as controls, so we do not comment the results in detail. We only highlight that, on top of the effect of the area of origin, students attending universities in the South have much lower timely completion probabilities than students in Centre-North institutions, and that movers have higher completion probabilities than stayers. Further, we notice that the supply side variates involved in the enrolment model are non-significant.

An overall picture of social selectivity

In the previous section, we have shown that higher education enrolment decisions and outcomes depend heavily on family background, also when comparing students with similar schooling careers, confirming that social origin exerts an effect on educational histories even after the end of upper secondary school in spite of the strong previous social selectivity. However, the analyses described above—typical in the existing literature—have two important limitations. First, by focusing on average marginal effects (AME), they miss to acknowledge the variability of the social background differential in the enrolment and retention probabilities across student profiles. Second, they overlook that in order to get a university degree, students need to enrol and complete their studies. How does the joint probability of enrolment and completion vary across student backgrounds? In this perspective, are these inequalities mainly due to the different propensities to enter higher education or to withdraw from it?

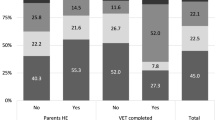

To address these points, we compute the probabilities of interest for different student profiles. As highlighted in the data section, due to right censoring, we have limited information on degree completion, so we will focus on 4-year retention instead. Firstly, we compute the joint probabilities of enrolling and not dropping out P(E = 1, D = 0) = P(E = 1)P(D = 0| E = 1) for different student profiles. As shown in Fig. 1, these probabilities vary between nearly 0 for individuals from the vocational track with low marks and the lowest social background and nearly 1 for individuals from the academic track with high marks and the highest social background. Social background differentials are small among well-performing students from the academic track, substantially higher for those with “medium” profiles (low-performing students from the academic track and well-performing students in the technical and vocational tracks) and highest (at least in relative terms) among students with the weakest schooling backgrounds.

Secondly, we plot the estimated probabilities in a scatter diagram (Fig. 2). In the left panels, we plot the estimates of the retention (no dropout) probability P(D = 0|E = 1) against the enrolment probability P(E = 1) by macro-area, for subgroups of children defined by parental education, class, upper secondary school track and final mark.Footnote 11 The position of the clouds in the plane corresponding to different student types allows an immediate understanding of the subgroups’ relative behaviour on the two outcomes. In the right panels, for each prior schooling profile defined by track and mark, we highlight the differences in the enrolment and retention probabilities between students from the lowest (parents with lower secondary degree and working class) and highest social backgrounds (parents with tertiary degree and in the service class).

These pictures show that:

-

(a)

Subgroups of students more likely to enter university are also more likely not to withdraw and the relation between these probabilities is very tight.

-

(b)

Differences according to prior schooling are very large on both dimensions (Fig. 2, left panel): students with a vocational diploma have the worst outcomes and those from lyceums the most favourable ones. Given the track, students with high marks do substantially better.

-

(c)

Social background inequalities given prior schooling characteristics are marked at both enrolment and retention (Fig. 2, right panel). On a whole, differentials appear largest among students from the vocational track and among low-performing students from the technical track. Smaller inequalities are observed for children with an academic upper secondary degree (very small if with high marks).

-

(d)

Social background inequalities in the retention dimension (Fig. 2, right panel) are particularly large for the students with the weakest prior schooling profiles (vocational track and low marks) and decrease when moving towards the more advantaged ones. The enrolment gap is largest within ‘medium’ schooling profiles (although in relative terms it seems critical also within weak profiles).

Retention versus timely completion

Retention within a given time span after enrolment is one measurable outcome of the students’ educational choices. An alternative outcome of interest is timely completion. Focusing on students enrolled in 3-year programs, for whom we observe degree attainment within 4 years, we now examine the relation between these two outcomes: the retention probability P(D = 0|E = 1) and the timely completion probability P(C = 1|E = 1). As shown in Fig. 3, the relation is positive, but highly curvilinear. There are well-defined clusters by school type and grades. Indeed, subgroups performing better in one dimension tend to do better also in the other one. However, for those with poor marks (in particular in the vocational and technical tracks), we find much larger social background differences along the retention–probability axis than along the timely completion one. For those with high marks, we find the opposite pattern, as dropout probabilities are generally low while timely completion differs markedly by academic content of the high school.

Our speculative explanation of this body of evidence is that timely completion is a much more stringent outcome than retention. While the first implies that students passed the examinations and earned credits, the second only states that students are formally enrolled. Yet, retention may coexist with very little progress in credit earning. In this light, the low probability of timely completion and its limited variability observed for poor-performing students from vocational and technical schools point to an actual difficulty experienced by youngsters with poor academic past credentials. Instead, we find a large variability in the retention probability across social backgrounds because, due to different aspirations, dropout is a more critical outcome for high-socioeconomic-level households.

It is worth noticing that territorial differences in timely completion are huge. Timely completion rates are particularly low (below 10%) for all Southern students with poor marks, whatever the school type, and barely reach 50% for the most advantaged student groups. Instead, in the North they vary much more substantially.

Role of labour market conditions

Previous analyses show that higher education outcomes markedly differ along the North–South divide, even when controlling for sociodemographic, prior schooling and university characteristics. Therefore, context factors matter. Labour market conditions across the country are very heterogeneous, the South being highly disadvantaged with respect to unemployment rates, female labour market participation and poverty rates (ISTAT 2016). In an exploratory perspective, we now analyse how labour market conditions relate to enrolment, dropout and timely completion, and whether they contribute to explaining statistically the observed territorial differentials. To measure labour market conditions, we use youth unemployment rates at the provincial level in 2007Footnote 12 , Footnote 13 This variable is added to models in Tables 3, 4 and 5. We include unemployment rates in quadratic term to capture possible non-linear effects. Our main results can be summarised as follows (see Table 6):

-

(a)

Unemployment rates follow an inversely U-shaped relation with enrolment, a negative relation with timely completion and a positive relation with dropout probabilities (panel I).

While at low unemployment rates individuals increase participation as unemployment rates increase, we observe the opposite pattern when unemployment rates become larger (the quadratic term is negative and significant).Footnote 14 Hence, with poor labour market conditions, discouragement seems to prevail. Similarly, individuals are more likely to withdraw from university in high unemployment areas. This result highlights that even before the economic downturn, university dropout in Italy was not largely driven by labour market acting as a pull out factor. Instead, the timely completion likelihood tends to decrease with higher unemployment; contrary to our results on enrolment and dropout, this result is consistent with the rational behaviour view that if the labour market prospects are poor, the opportunity costs of being in education decline and individuals should take longer to attain their degrees.

-

(b)

Unemployment rates partially explain the territorial differences in the timely completion probability, fully explain the male enrolment gap between North and South, but do not contribute explaining territorial differences in dropout rates (panel II).

In panel II, we report the geographical AMEs in models with and without unemployment rates. Labour market conditions partially explain the large territorial divide in timely completion as AMEs decrease by 25–45% when introducing unemployment rates. Instead, unemployment rates fully explain the enrolment North–South differential for males and partially explain the enrolment North–Centre differential for both genders, but do not reduce the large dropout North–Centre gap. According to our estimates, if exposed to similar unemployment rates, the enrolment probability of Southern females would exceed that of Northern females and the dropout probability of Northern males would exceed that of Southern males.

Conclusions

Despite the strong social selectivity operating at earlier stages of schooling, parental education and class keep exerting an influence even after high school completion and net of prior performance and schooling characteristics. The existing literature has documented the effect of family background on enrolment and dropout probabilities, but there has been no attempt to look at these outcomes jointly. Yet, a comprehensive outlook on all higher education outcomes is important, as the probability of eventually attaining a university degree is determined by both enrolment and continuation decisions. Moreover, by focusing on average marginal effects, the existing literature does not highlight the heterogeneity of social inequalities across students with different prior schooling histories.

Depicting the estimated enrolment and retention probabilities for recent cohorts of young individuals with different profiles in terms of prior schooling and area of the country, we see very clearly that disadvantaged groups with respect to enrolment are also disadvantaged on persistence, and that cumulative differentials are huge. On a whole, inequalities across social backgrounds appear to be strongest between vocational track students and weakest between academic track students with high marks. This provides evidence of “compensatory effects” (Bernardi and Cebolla Boado 2014), according to which educational choices differ more strongly among children with poor school results because socioeconomically advantaged backgrounds have higher incentives to compensate their offspring’s poor performance in order to avoid the risk of downward mobility (Breen and Golthorpe 1997). Our results also highlight that among students with poor academic credentials, social background inequalities are large on both enrolment and dropout; however, differences in dropout probabilities decline among students with “better” schooling careers, whereas (if we exclude the best students from the lyceums) differences in enrolment remain important.

The relation between two indicators of success—retention and timely completion—is highly non-linear. Students with low marks have very small chances of attaining the degree in time, regardless of social background, while differences in retention probabilities are sizable. Our speculative explanation is that in the Italian system, timely completion is a much more stringent outcome than retention. Thus, the low chances of timely completion of poor-performing students from the vocational or technical tracks and its limited variability across backgrounds point to an actual difficulty experienced by students with weak academic past credentials.

The low chances of enrolment and successful completion of the students following educational programs with little academic content or poor school records are clearly detrimental to equity (since these students come disproportionately from disadvantaged backgrounds), but could be considered beneficial to efficiency. Yet, endowed students from disadvantaged backgrounds—in particular those who attended technical and vocational high school programs—should be the target of specific interventions aimed at promoting higher education enrolment and completion. This would have two beneficial consequences: to raise equity while increasing the share of individuals with higher education—without lowering learning standards.

Focusing on territorial disparities, enrolment, retention and especially timely completion probabilities are lower in provinces with high youth unemployment rates, suggesting that with poor labour market prospects, individuals lose motivation and reduce their engagement in education. However, unemployment rates only contribute explaining geographical differentials in timely completion.

What can we say about the main drivers of university dropout in Italy at the onset of the economic crisis? This is clearly a complex question, difficult to address with cross-sectional data. However, our analyses give some insights on the role of alternative factors potentially at play (Jordan et al. 1996; Watt and Roessingh 1994). Push factors clearly prevail: indeed, poor prior academic preparation stems out as the major determinant of withdrawal. Low motivation also seems to matter, as we find indirect evidence that high unemployment fosters discouragement. Instead, our results do not support the importance of pull factors diverting students from completing their educational programs, as with better employment prospects we observe less dropout.Footnote 15 There is no evidence, either, of the importance of alternative pull factors like family care duties (in Italy still largely in charge of women) as the dropout probability is much larger for males than for females.

Due to the lack of data, a limitation of our work is that we cannot study higher education completion altogether. As mentioned above, previous waves of the survey did not even allow studying timely completion, as they were held only 3 years after the end of high school. Due to the lengthened retrospective observation window (4 years), we are now able to study timely completion. Yet, we cannot move further and study degree attainment. We envisage this as a major shortcoming because, as we have seen, inequalities in different indicators of success follow substantially different patterns. Universities’ administrative records, enriched with information on the student family background (currently not available), seem to be the only potential source of information enabling to address the hot topic of degree completion in Italy.

Notes

Participation rates of individuals aged 22 are close to the EU average, around 30% for males and over 40% for females in 2009 (Eurydice 2012).

As an alternative to state-level education, students may also enter regional-based vocational training, lasting 2–3 years and not allowing access to higher education.

For this reason, we refer to higher education and university system as synonymous.

In 2014, the average completion time for 3-year programs was 4.6 years (Almalaurea 2015).

In 2012, average tuition fees in Northern public universities were more than twice in the South (Cattaneo et al. 2017).

19% of the students benefitted from public financial aid in 2010–2011 (OECD 2013).

We analyse students entering university immediately after high school. We disregard those delaying entry because for them completion is rarely observed.

Age is not included because it is nearly collinear to school year repetitions. Due to the limited number of immigrant background students in the data, we also ignore the migrant status.

The index is defined as the difference between the volumes of the province inflows and outflows, divided by their sum.

The AME corresponding to a continuous independent variable is the average over all sample units of the first derivative of the estimated probability of the outcome with respect to that variable. If the explanatory variable is categorical, AME measures the discrete change in this probability relative to a comparison with the reference category.

Youth provincial unemployment rate (age15–29). In 2007, this rate varied across provinces between 3 and 46%. The average provincial rate was 12.2% in the North, 16.0% in the Centre and 31.3% in the South.

We also estimated models for dropout and timely completion including the unemployment rate of the university province instead of the province of origin. Results are very similar so they are not reported here.

Given the large territorial differences in unemployment rates (cf. note 14), when estimating separate models by macro-area we find a positive effect of unemployment rates in the North and a negative effect in the Centre and South.

Additional support to this interpretation is delivered by direct information on individuals’ labour market experiences recorded in the survey: among dropouts who were not employed at time of enrolment, less than 20% started working within 6 months from withdrawal.

References

Agasisti, T. (2009). Market forces and competition in university systems: theoretical reflections and empirical evidence from Italy. International Review of Applied Economics, 23, 463–483.

Agasisti, T., S. Murtinu (2016) Grants in Italian University: A Look at the Heterogeneity of their Impact on Students’ Performances. Studies in Higher Education, 41(6) 1106-1132

Aina, C., Baici, E., & Casalone, G. (2011). Time to degree: students’ abilities, university characteristics or something else? Evidence from Italy. Education Economics, 19(3), 311–325.

Aina, C. (2013). Parental background and university dropout in Italy. Higher Education, 65(4), 437–456.

Almalaurea. (2015). XVII indagine Profilo dei Laureati 2014. Bologna: Consorzio AlmaLaurea http://www.almalaurea.it/universita/profilo.

ANVUR. (2016). Rapporto sullo stato del sistema universitario e della ricerca 2016. Roma: Agenzia Nazionale di Valutazione del Sistema Universitario e della Ricerca.

Argentin, G., & Triventi, M. (2011). Social inequality in higher education and labour market in a period of institutional reforms: Italy, 1992–2007. Higher Education, 61, 309–323.

Arulampalam, W., Naylor, R. A., & Smith, J. P. (2005). Effects of in-class variation and student rank on the probability of withdrawal: cross-section and time-series analysis for UK university students. Economics of Education Review, 24, 251–262.

Beattie, I. R. (2002). Are all “adolescent econometricians” created equal? Racial, lass, and gender differences in college enrollment. Sociology of Education, 75(1), 19–43.

Belloc, F., Maruotti, A., & Petrella, L. (2010). University dropout: an Italian experience. Higher Education, 60, 127–138.

Bernardi, F., & Cebolla Boado, H. (2014). Previous school results and social background: compensation and imperfect information in educational transitions. European Sociological Review, 30(2), 207–217.

Bertola, G., Checchi, D., & Oppedisano, V. (2008). Private school quality in Italy. Giornale degli Economisti e Annali di Economia, 66-3, 375–400.

Bourdieu P., J.C. Passeron (1990) Reproduction in education, society, and culture, Vol 4, Sage.

Boudon R. (1974) Education, opportunity, and social inequality: changing prospects in western society. New York, John Wiley & Sons.

Bound, J., Lovenheim, M., & Turner, S. (2010). Why have college completion rates declined? An analysis of changing student preparation and collegiate resources. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(3), 129–157.

Bowen, W., Chingos, M., & McPherson, M. (2009). Crossing the finish line: completing college at America’s public universities. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Breen, R., & Golthorpe, J. (1997). Explaining educational differentials: towards a formal rational action theory. Rationality and Society, 9, 275–305.

Cappellari, L., & Lucifora, C. (2009). The “Bologna process” and college enrollment decisions. Labour Economics, 16, 638–647.

Carneiro, P., & Heckman, J. (2002). The evidence on credit constraints in postsecondary schooling. Economic Journal, 112, 705–734.

Carrieri V., M. D'Amato, R. Zotti (2015) On the causal effects of selective admission policies on students’ performances: evidence from a quasi-experiment in a large Italian university. Oxford Economic Papers. 67(4), 1034–1056.

Cattaneo M., H. Horta, P. Malighetti, M. Meoli, S. Paleari (2016) Effects of the financial crisis on university choice by gender, Higher Education.

Cattaneo M., P. Malighetti, M. Meoli, S. Paleari (2017) University spatial competition for students: the Italian case, Regional Studies.

Checchi D., C. V. Fiorio, M. Leonardi (2014) Parent’s risk aversion and children’s educational attainment, Labour Economics. 30, 164–175.

Checchi D., L. Flabbi. (2007). Intergenerational mobility and schooling decisions in Germany and Italy: the impact of secondary school tracks. IZA Discussion Paper n.2876.

Cingano F., P. Cipollone (2007). University drop-out: the case of Italy, Temi di discussione Servizio Studi della Banca d’Italia, 626.

Clerici R., A. Giraldo, S. Meggiolaro (2014) The determinants of academic outcomes in a competing risks approach: evidence from Italy, Studies in Higher Education. 40(9), 1535–1549.

Contini, D., & Scagni, A. (2011). Inequality of opportunity in secondary school enrolment in Italy, Germany and the Netherlands. Quality and Quantity, 45, n.2.

Contini D., A. Scagni (2013) Social origin inequalities in educational careers in Italy. Performance or decision effects? In Jackson Michelle (Ed.), Determined to fail? Performance, choice and education, Stanford, Stanford University Press.

Contini, D., & Triventi, M. (2016). Between formal openness and stratification in secondary education: implications for social inequalities in Italy. In H. P. Blossfeld, S. Buchholz, J. Skopek, & M. Triventi (Eds.), Models of secondary education and social inequality—an international comparison (pp. 305–322). Cheltenham and Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Di Pietro, G. (2004). The determinants of university dropout in Italy: a bivariate probability model with sample selection. Applied Economics Letters, 11(3), 187–191.

Di Pietro, G. (2006). Regional labour market conditions and university dropout rates: evidence from Italy. Regional Studies, 40(6), 617–630.

Di Pietro, G., & Cutillo, A. (2008). Degree flexibility and university dropout: the Italian experience. Economics of Education Review, 27, 546–555.

Dotti, N. F., Fratesi, U., Lenzi, C., & Percoco, M. (2013). Local labour markets and the interregional mobility of Italian university students. Spatial Economic Analysis, 8(4), 443–468.

Dynarski, S. (2003). Does aid matter? Measuring the effect of student aid on college attendance and completion. American Economic Review, 93(1), 279–288.

Eurostat (2015). Education and training in the EU-facts and figures http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Education_and_training_in_the_EUfacts_and_figures.

Eurydice (2012). Key Data on Education in Europe 2012, European Commission.

Garibaldi, P., Giavazzi, F., Ichino, A., & Rettore, E. (2012). College cost and time to complete a degree: evidence from tuition discontinuities. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 94(3), 699–711.

Ghignoni, E. (2017). Family background and university dropouts during the crisis: the case of Italy. Higher Education, 73(1), 127–151.

Hillman, N. W., & Orians, E. L. (2013). Financial Aid’s role in meeting state college completion goals. Education Finance and Policy, 8(3), 349–363.

ISTAT (2016) Italia in cifre 2016, Istituto Nazional di Statistica, http://www.istat.it/it/files/2016/12/ItaliaCifre2016.pdf.

Jackson M. eds.(2013), Determined to succeed? Performance, choice and education, Stanford, Stanford University Press.

Jordan, W. J., Lara, J., & Mc Partland, J. M. (1996). Exploring the causes of early dropout among race-ethnic and gender groups. Youth and Society, 28(1), 62–94.

Kurlaender, M., Jackson, J., Howell, J. S., & Grodsky, E. (2014). College course scarcity and time to degree. Economics of Education Review, 41, 24–39.

Mealli, F., & Rampichini, C. (2012). Evaluating the effects of university grants by using regression discontinuity designs. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society A, 175(3), 775–798.

Montmarquette, C., Mahseredjian, S., & Houle, R. (2001). The determinants of university dropouts: a bivariate probability model with sample selection. Economics of Education Review, 20(2001), 475–484.

OECD (2013), Education at a glance 2013: OECD indicators, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/eag-2013-en

Pigini, C., & Staffolani, S. (2016). Beyond participation: do the cost and quality of higher education shape the enrollment composition? The case of Italy. Higher Education. 71(1), 119–142.

Watt, D., & Roessingh, H. (1994). Some you win, most you lose: tracking ESL dropout in high-school (1988–1993). English Quarterly, 26, 5–7.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2002). Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. The MIT Press. Cambridge, Massachusetts. London, England.

Smith, J. P., & Naylor, R. A. (2001). Dropping out of university: a statistical analysis of the probability of withdrawal for UK university students. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society A, 164(2), 389–405.

Stinebrickner, R., & Stinebrickner, T. (2008). The effect of credit constraints on the college drop-out decision: a direct approach using a new panel study. American Economic Review, 98(5), 2163–2184.

Stinebrickner R., T. Stinebrickner (2014) Academic performance and college dropout: using longitudinal expectations data to estimate a learning model, NBER Working Paper 1894.

Tinto, V. (1975). Dropout from higher education: a theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of Educational Research, 45(1), 89–125.

Vignoles A. F., N. Powdthavee (2009) The socioeconomic gap in university dropouts, The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy. 9(1), 1–36.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 280 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Contini, D., Cugnata, F. & Scagni, A. Social selection in higher education. Enrolment, dropout and timely degree attainment in Italy. High Educ 75, 785–808 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0170-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0170-9