Abstract

Nowadays, a number of metaheuristics have been developed for efficiently solving multi-objective optimization problems. Estimation of distribution algorithms are a special class of metaheuristic that intensively apply probabilistic modeling and, as well as local search methods, are widely used to make the search more efficient. In this paper, we apply a Hybrid Multi-objective Bayesian Estimation of Distribution Algorithm (HMOBEDA) in multi and many objective scenarios by modeling the joint probability of decision variables, objectives, and the configuration parameters of an embedded local search (LS). We analyze the benefits of the online configuration of LS parameters by comparing the proposed approach with LS off-line versions using instances of the multi-objective knapsack problem with two to five and eight objectives. HMOBEDA is also compared with five advanced evolutionary methods using the same instances. Results show that HMOBEDA outperforms the other approaches including those with off-line configuration. HMOBEDA not only provides the best value for hypervolume indicator and IGD metric in most of the cases, but it also computes a very diverse solutions set close to the estimated Pareto front.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In many optimization problems, maximizing/minimizing several objective functions represents a challenge to a large number of optimizers (specially for single-objective approaches which are usually no longer applicable in these cases) (Luque 2015). This class of problems is known as Multi-objective Optimization Problems (MOPs), and multi-objective optimization has thus been established as an important field of research (Deb 2001). Recently, problems with more than three objectives are becoming usual and the area has been referred to as many objective optimization (Ishibuchi et al. 2008).

Evolutionary algorithms (EAs) and other metaheuristics have been widely used for solving multi and many objective optimization, mainly due to their ability to discover multiple solutions in parallel and to handle the complex features of such problems (Coello 1999). In most of cases, local optimizers and probabilistic modeling can also be aggregated to capture and exploit the potential regularities that arise in the promising solutions.

As a special case of these hybrid approaches, Multi-objective Evolutionary Algorithms (MOEAs) incorporating local search (LS) have been investigated, and can often achieve good performance for many problems (Lara et al. 2010; Zhou et al. 2011, 2015. However, as discussed in Martins et al. (2016), they still present challenges, like the choice of suitable LS parameters (e.g., the type, frequency and intensity of LS applied on a specific candidate solution).

Some previous works have proposed techniques for configuring and tuning the parameters, like in Freitas et al. (2014), where the authors present a method based on evolutionary strategies with local search and self-adaptation of the parameters for single-objective optimization. Another example is Corriveau et al. (2016), where an adaptive parameter setting approach solves multimodal problems using genetic algorithms and Bayesian networks. These techniques can also be extended to multi-objective optimization. In López-Ibáñez et al. (2011), the I/F-race tool integrates the hypervolume indicator into the iterated process to automatically configure multi-objective algorithms with many parameters for an optimization problem. This technique can be used with other unary quality indicators, such as epsilon or R-indicator.

Another strategy widely used in evolutionary optimization is probabilistic modelling, which is the base of Estimation of Distribution Algorithms (EDAs) (Mühlenbein and Paab 1996). The main idea of EDAs (Larrañaga and Lozano 2002) is to extract and represent, using a probabilistic graphical model (PGM), the regularities shared by a subset of high-valued problem solutions. New solutions are then sampled from the PGM biasing the search to areas where optimal solutions are more likely to be found. Normally, EDAs integrate both, the model building and sampling techniques, into evolutionary optimizers using special selection schemes (Laumanns and Ocenasek 2002).

This paper addresses a combinatorial MOP—the multi-objective version of the well known knapsack problem named Multi-objective Knapsack Problem (MOKP) which has been recently explored in other works in the literature (Ishibuchi et al. 2015; Ke et al. 2014; Tan and Jiao 2013; Tanigaki et al. 2014; Vianna and de Fátima Dianin Vianna 2013). In particular, Multi-objective Estimation of Distribution Algorithms (MOEDAs) that use different types of probabilistic models have already been applied to MOKP (Li et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2012), specially those EDAs based on Bayesian networks as reported in Laumanns and Ocenasek (2002), Martins et al. (2016) and Schwarz and Ocenasek (2001).

The approach considered in this paper is named HMOBEDA and is based on a joint probabilistic modeling of decision variables, objectives, and parameters of the local optimizer. As discussed in Martins et al. (2016), the rationale of HMOBEDA is that the embedded PGM can be structured to sample appropriate LS parameters for different configurations of decision variables and objective values during the search (which is named online configuration). However, differently from Martins et al. (2016), this work includes an additional investigation of off-line versions of LS parameter tuning: \(\text {HMOBEDA}_f\), \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{f_{inst}}\) and \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{irace}\).

In \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{irace}\) for example, an automatic configuration tool (irace) that is considered a state-of-the-art method for parameter tuning is adopted to define the LS parameters. Therefore in our framework it is possible to compare both techniques: online and off-line LS configuration approaches. Aiming to evaluate an indicator-based approach, this work presents another HMOBEDA version based on the hypervolume indicator (Bader 2009) as part of the selection procedure.

This work also compares HMOBEDA with traditional approaches for multi and many objective optimization based on the Inverted Generational Distance (IGD) quality indicator in addition to the hypervolume (HV) metric. Our work has intersections with other previous published works (Bader 2009; Karshenas et al. 2014; Li et al. 2004). It is linked to the work presented in Karshenas et al. (2014) in which a joint probabilistic model of objectives and variables is proposed, and related to Li et al. (2004) by considering a weighted sum method in the fitness computation of each neighbor produced by the LS procedure. In contrast with the research presented in Li et al. (2004), our work considers an objective alternate mode to fitness computation and a bayesian network as the PGM.

Therefore, besides providing a natural extension of previous works to investigate probabilistic modeling of variables, objectives and LS parameters all together, the main contributions on the present work are: (i) it extends the original HMOBEDA proposal providing other variants where the LS parameters are determined in different ways and fixed along the search (off-line configuration); (ii) it also presents a different HMOBEDA version that computes and uses the hypervolume indicator (Bader 2009) as part of the selection procedure; (iii) the comparison with state-of-the-art-algorithms includes the IGD metric to provide a more complete picture of HMOBEDA behavior.

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a brief introduction to EDAs and Bayesian network as PGM (Larrañaga et al. 2012). Section 3 details the proposed approach. Results from numerical experiments are shown and discussed in Sect. 4, with the conclusions and future directions presented in Sect. 5.

2 Preliminaries

EDAs are population based optimization algorithms that have been claimed as a paradigm shift in the field of EA, which employ explicit probability distributions in optimization (Larrañaga and Lozano 2002).

EDAs have achieved good performance when applied in several problems (Pham 2011) including environmental monitoring network design (Kollat et al. 2008), protein side chain placement problem (Santana et al. 2008), table ordering (Bengoetxea et al. 2011), multi-objective knapsack (Shah and Reed 2011) and MOPs in a noisy environment (Shim et al. 2013).

Based on the problem solution representation, EDAs can be classified in discrete and real-valued, considering the variables that can either be discrete ones or receive a real value that covers an infinite domain. According to the interactions between variables, EDA models can be categorized into three classes (Hauschild and Pelikan 2011): Univariate, Bivariate and Multivariate based on the level of interactions among variables.

Univariate EDAs assume no interaction among variables, and Univariate Marginal Distribution Algorithm (UMDA) (Mühlenbein and Paab 1996) is an example. For bivariate EDAs, pairwise interactions among variables in the solutions are considered, like in Bivariate Marginal Distribution Algorithm (BMDA) (Pelikan and Muehlenbein 1999). Multivariate EDAs use probabilistic models capable of capturing multivariate interactions between variables (Bengoetxea et al. 2011). Algorithms using multivariate models of probability distribution include: Extended Compact Genetic Algorithm (ECGA) (Harik 1999), Bayesian Network Algorithm (EBNA) (Etxeberria and Larrañaga 1999), Factorised Distribution Algorithm (FDA) (Mühlenbein and Mahnig 1999), Bayesian Optimisation Algorithm (BOA) (Pelikan et al. 1999), Hierarchical Bayesian Optimisation Algorithm (hBOA) (Pelikan et al. 2003), Markovianity-based Optimisation Algorithm (MOA) (Shakya and Santana 2008) and Affinity Propagation EDA (AffEDA) (Santana et al. 2010).

Another relevant classification is according to the probability model learning: algorithms that only make a parametric learning of the probabilities, like UMDA; and algorithms where structural learning of the model is also done, like the ones using Bayesian networks (Santana et al. 2008).

2.1 Bayesian network as PGM

Bayesian networks (BN) are directed acyclic graphs (DAG) whose nodes represent variables, and whose missing edges encode conditional independencies between triplets of variables. Random variables represented by nodes may be observable quantities, latent variables, unknown parameters or hypotheses. Each node is associated with a probability function that takes as input a particular set of values for the node’s parent variables and gives the probability of the variable represented by the node (Cooper and Herskovits 1992; Korb and Nicholson 2010).

Let \({\mathbf {Y}}=(Y_1,\ldots ,Y_M)\) be a set of random variables, and let \(y_m\) be a value of \(Y_m\), the m-th component of \({\mathbf {Y}}\). The representation of a bayesian model is given by two components (Larrañaga et al. 2012): a structure and a set of local parameters. The set of local parameters \(\mathbf {\theta }_B\in {{\varvec{\Theta }}}_B\) containing, for each variable, the conditional probability distribution of its values given different value settings for its parents, according to structure B.

The structure B for \({\mathbf {Y}}\) is a DAG that describes a set of conditional independencies about triplets of variables in \({\mathbf {Y}}\). \({\mathbf {Pa}}^B_m\) represents the set of parents (variables from which an arrow is coming out in B) of the variable \(Y_m\) in the PGM which structure is given by B (Bengoetxea 2002). The structure B for \({\mathbf {Y}}\) assumes that \(Y_m\) and its non descendants are conditionally independent given \({\mathbf {Pa}}^B_m\), \(m = 2,\ldots ,M\), where \(Y_1\) is the root note.

Therefore, a Bayesian network encodes a factorization for the joint probability distribution of the variables as follows:

Equation 1 states that the joint probability distribution of the variables can be computed as the product of each variables conditional probability distributions given the values of its parents. These conditional probabilities are stored as local parameters \(\mathbf {\theta }_B\), where \(\mathbf {\theta }_B = (\mathbf {\theta }_1,\ldots , \mathbf {\theta }_M)\).

In discrete domains, \(Y_m\) has \(s_m\) possible values, \(y^1_m,\ldots , y^{s_m}_m\), therefore the local distribution, \(p(y_m|{\mathbf {pa}}^{j,B}_m,\mathbf {\theta }_m)\) is a discrete distribution:

where \({\mathbf {pa}}_m^{1,B},\ldots ,{\mathbf {pa}}_m^{t_m,B}\) denotes the combination of values of \({\mathbf {Pa}}^B_m\), that is the set of parents of the variable \(Y_m\) in the structure B; \(t_m\) is the number of different possible instantiations of the parent variables of \(Y_m\). The possible number of \(t_m\) combination of values that \({\mathbf {Pa}}_m\) can assumes is \(t_m=\prod _{Y_v\in {\mathbf {Pa}}_m^B} s_v\). The parameter \(\theta _{mjk}\) represents the conditional probability that variable \(Y_m\) takes its \(k-\)th value (\(y_m^k\)), knowing that its parent variables have taken their j-th combination of values (\({\mathbf {pa}}^{j,B}_m\)).

The BN learning process can be divided into (i) structural learning, i.e., identification of the topology B of the BN and (ii) parametric learning, estimation of the numerical parameters (conditional probabilities \({{\varvec{\Theta }}}\)) for a given network B.

Most of the developed structure learning algorithms fall into the score-based approaches. Score-based learning methods evaluate the quality of BN structures using a scoring function, like Bayesian Dirichlet (BD)-metric (Heckerman et al. 1995), and search for the best one. The BD metric, defined by Eq. 3, combines the prior knowledge about the problem and the statistical data from a given data set.

where p(B) is the prior factor of quality information of the network B. If there is no prior information for B, p(B) is considered a uniform probability distribution (Luna 2004) and generally its value is set to 1 (Crocomo and Delbem 2011). The product on \(j\in \{1,\ldots ,t_m\}\) runs over all combinations of the parents of \(Y_m\) and the product on \(k\in \{1,\ldots ,s_m\}\) runs over all possible values of \(Y_m\). \(N_{mj}\) is the number of instances in Pop with the parents of \(Y_m\) instantiated to its j-th combination. By \(N_{mjk}\), we denote the number of instances in Pop that have both \(Y_m\) set to its k-th value as well as the parents of \(Y_m\) set to its j-the combination of values. \(\varGamma (x)=(x-1)!\) for \(x\in N\) is the Gamma function used in Dirichlet prior (DeGroot 2005) that satisfies \(\varGamma (x+1)=x\varGamma (x)\) and \(\varGamma (1)=1\).

Through \(\alpha _{mjk}\) and p(B), prior information about the problem is incorporated into the metric. The parameters \(\alpha _{mjk}\) stands for prior information about the number of instances that have \(Y_m\) set to its k-th value and the set of parents of \(Y_m\) is instantiated to its j-th combination. The prior network can be set to an empty network, when there is no such information.

In the so-called K2 metric (Cooper and Herskovits 1992) for instance, the parameters \(\alpha _{mjk}\) can be set to 1 as there is no prior information about the problem, and Eq. 3 becomes Eq. 4:

Since the factorials in Eq. 4 can grow to huge numbers, a computer overflow might occur. Thus the logarithm of the scoring metric \(\text {log} (p(B|Pop))\) is usually used, as shown in Eq. 5.

Various algorithms can be used for searching the networks structures to maximize the value of a scoring metric, like a simple greedy algorithm, local hill-climbing, simulated annealing, tabu search and evolutionary computation (Larrañaga et al. 2012).

The K2 algorithm is a greedy local search technique that applies K2 metric in its logarithmic form (Eq. 5). It starts by assuming that a node does not have parents, then in each step it gradually adds the edges which increase the scoring metric the most until no edge increases the metric anymore. The variables ordering are the incoming input to the algorithm, which might heavily alter the results (Larrañaga et al. 2013), as it pre-establishes a possible relation between a node and its parents (ascendent nodes).

Other greedy local search techniques also apply K2 metric, like in Pelikan (1999), where the authors implemented a modified K2 algorithm considering no variables ordering, resulting in a high DAG search space.

In this work we adopted K2 metric as score-based technique, although any other method could be used as well. We use the K2 algorithm considering the objectives as parents in the network.

Regarding to the parameter estimation and considering that BN’s are often used for modeling multinomial data with discrete variables (Pearl 1988), we applied the Bayesian estimate, which considers the expected value \(E(\theta _{mjk}|\mathbf {N}_{mj}, B)\) of \(\theta _{mjk}\) as an estimate of \(\theta _{mjk}\), as shown in Eq. 6.

where \(N_{mjk}\) fits a multinomial distribution, and \(N_{mj}=\sum _{k=1}^{s_m}N_{mjk}\).

3 The algorithm: HMOBEDA

In this section, we detail the HMOBEDA framework emphasizing its main characteristics, i.e., the probabilistic model encompassing three types of nodes: decision variables, objectives and configuration parameters of its embedded LS.

3.1 Encoding scheme

Every individual is represented by a joint vector with \(Q + R + L\) elements, \({\mathbf {y}}=({\mathbf {x}},{\mathbf {z}},{\mathbf {p}})= (X_1,\ldots ,X_Q,Z_1,\ldots , Z_R, P_1,\ldots ,P_L)\), denoting the decision variables \((X_1,\ldots ,X_Q)\), objectives \((Z_1,\ldots , Z_R)\) and LS parameters \((P_1,\ldots ,P_L)\). Subvectors \({\mathbf {x}}\), \({\mathbf {z}}\) and \({\mathbf {p}}\) can be specified as:

-

\({\mathbf {x}}\) is a binary subvector of items, with element \(X_q \in \{0,1\}\), \(q=1\ldots Q\), indicating the presence or absence of the associated item;

-

\({\mathbf {z}}\) is a subvector of objectives, with element \(Z_r\), \(r=1\ldots R\), representing the discrete value of the r th objective.

-

\({\mathbf {p}}\) is a subvector of elements, where each element \(P_l\), \(l=1\ldots L\), indicates the value associated with an LS parameter. Different parameters can be considered. For example, the maximum number of iterations performed by LS, the neighborhood type and the type of procedure used to compute the neighbor fitness.

3.2 The HMOBEDA framework

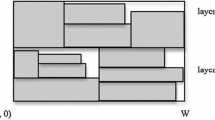

A general schema of the adopted version of HMOBEDA is presented in Fig. 1.

The Initialization process randomly generates N subvectors \({\mathbf {x}}\) and \({\mathbf {p}}\) to compose the initial population \(Pop^1\). For each subvector \({\mathbf {x}}\), the values of the corresponding objectives are calculated based on the objective functions of the addressed problem and further made discrete to form the subvector \({\mathbf {z}}\).

The Survival block sorts individuals using the non-dominated sorting procedure (Srinivas and Deb 1994). It calculates the Dominance Rank (DR) (Zitzler et al. 2000), and also a diversity criterion named Crowding Distance (CD) (Deb et al. 2002). Individuals are sorted taking at first DR and secondly (in case of ties) the CD criterion. Finally, truncation selection takes place selecting the best N solutions (at the first generation the entire population is selected). Besides the original HMOBEDA(Martins et al. 2016), in this work we have also implemented another online configuration of HMOBEDA based on the hypervolume indicator, named \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{hype}\), which substitutes the CD tie-breaker criterion by the hypervolume fitness value in the Survival block of Fig. 1.

In the sequence, the Local Search block adopts a very simple LS procedure based on Hill Climbing (HC) (Russel and Norvig 2003). For every solution in \(Pop^g\), HCLS generates a neighbor (nhb), calculates its fitness and nhb substitutes the original solution in case it has a better fitness. As previously discussed, the subvector \({\mathbf {p}}\) defines the parameters associated with HCLS. In this paper it defines how many iterations (\(N_{iter}\)) will be used, how each neighbor will be generated (\(T_{nbh}\)), and finally how to compute the neighbor fitness (\(T_{Fnbh}\)) in a single-objective way. If a neighbor is infeasible, the algorithm applies the same greedy repair method as in Zitzler and Thiele (1999). It repairs the solution by removing items in an ascending order of the relation profit/weight until all the constraints conditions are satisfied.

The EDA Selection block starts with the PGM construction phase. A binary tournament selects \(N_{PGM}\) individuals from \(Pop^g\). The procedure randomly selects two solutions and the one positioned in the best front is chosen. If they lie in the same front, it chooses that solution with the greatest CD. Then, \(Pop_{PGM}^g\) is obtained encompassing \(N_{PGM}\) good individuals.

BN structure and BN parameters are estimated based on the joint probabilistic model of Q decision variables, R objectives and L local search parameters, (i.e. \({\mathbf {Y}}=(Y_1,\ldots Y_M) = (Z_1,\ldots Z_R, X_1,\ldots X_Q, P_1,\ldots P_L))\). It encodes a factorization of the joint probability distributions \(\rho ({\mathbf {y}})=\rho (z_1,\ldots ,z_R;x_1,\ldots ,x_Q;p_1,\ldots ,p_L;)\) given by:

where \({\mathbf {Pa}}_{r}^B=\emptyset \), \({\mathbf {Pa}}_{q}^B\subseteq \{Z_1,\ldots Z_R\}\) and \({\mathbf {Pa}}_{l}^B\subseteq \{Z_1,\ldots Z_R\}\) are the parents of each objective, variable and LS parameter node respectively, and \({\mathbf {pa}}_{r}^B\), \({\mathbf {pa}}_{q}^B\) and \({\mathbf {pa}}_{l}^B\) represent one of their combination of values.

Therefore, aiming to learn the probabilistic model, the EDA Model block divides the objective values collected from vector \({\mathbf {z}}\) in \(Pop^g_{PGM}\) into \(sd_r\) discrete states.Footnote 1 Considering that the BN model is estimated using the K2-metric (Eq. 5) and the Bayesian estimate (Eq. 6) with objectives as BN nodes, \({\mathbf {z}}\) also fits a multinomial distribution. Thus, to minimize the computational efforts to model B using all the \(s_r\) states, we have applied the discretization process with a limited number of possible values for each \(z_r\in {\mathbf {z}}\) fixed as \(sd_r\). In this case we assume the same \(sd_r\) value for each \(z_r\) node. The K2 algorithm is used here by setting parent nodes as objectives in the network. The same parents relationship was considered in Karshenas et al. (2014).

As discussed in Martins et al. (2016), the advantage of HMOBEDA over traditional EDA-based approaches is that besides providing good decision variables (based on the model captured from good solutions present in \(Pop_{PGM}^g\)) it can also provide LS parameters more related to good objective values which are fixed as evidence.

In the Sampling block, the obtained PGM is used to sample the set of new individuals (\(Pop_{smp}\)). In this case, not only decision variables \({\mathbf {x}}\), but also, local search parameters \({\mathbf {p}}\) can be sampled. Although the proposed methodology accepts any Bayesian Network structure, in the experiments, all learned structures are as the one represented in Fig. 2, considering no relation between variables, between parameters and between both (variables and parameters). This naive Bayesian model, is adopted to facilitate the sampling process: fixing objective values with high values (for maximization problems) enables the estimation of their associated decision variables and LS parameters.

The union of the sampled population (\(Pop_{smp}\)) and the current population (\(Pop^g\)) in the EDA Merge block is used to create the new population for the next generation \(g+1\). Individuals (the old and the new ones) are selected to the next generation in the Survival block, and the main loop continues until the stop condition is achieved.

4 Experiments and results

The multi-objective knapsack problem addressed in this paper can be formulated as follows:

where \({\mathbf {x}}\) is a Q-dimension binary vector, such that \(x_q = 1\) means that item q is selected to be in r-th knapsack and \(a_{rq}\), \(b_{rq}\) and \(c_r\) are nonnegative coefficients. Given a total of R objective functions (knapsacks) and Q items, \(a_{rq}\) is the profit of item \(q=1,\ldots , Q\), according to knapsack \(r=1,\ldots ,R\), \(b_{rq}\) denotes the weight of item q according to knapsack r, and \(c_r\) is the constraint capacity of knapsack r.

Experiments conducted in this paper adopt the union of each set of instances considered in Ishibuchi et al. (2015), Tanigaki et al. (2014) and Zitzler and Thiele (1999). We use thus instances for 100 and 250 items, with 2 to 5 and 8 objectives. We characterize each instance as R-Q, where R is the number of objectives and Q is the number of items. The values of \(a_q^r\) and \(b_q^r\) are specified as integers in the interval [10, 100]. According to Zitzler and Thiele (1999), the capacity \(c_r\) is specified as \(50\%\) of the sum of all weights related to each knapsack r.

In this section, we compare the original HMOBEDA(Martins et al. 2016) with four modified versions: \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{f}\), \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{f-inst}\), \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{irace}\) and

\(\text {HMOBEDA}_{hype}\); and, further, with MBN-EDA (Karshenas et al. 2014), NSGA-II (Deb et al. 2002), S-MOGLS (NSGA-II with local search) (Ishibuchi et al. 2008), MOEA/D (Zhang and Li 2007), and NSGA-III (Deb and Jain 2014).

All algorithms used for comparison are the original ones found in the literature. The exception is NSGA-III that has been adapted for combinatorial optimization. MOEA/D and NSGA-III are implemented in C++, and the remaining algorithms in MatLab.

4.1 Algorithm settings

The parameters for each algorithm are shown in Table 1.

As in Ishibuchi et al. (2008), for S-MOGLS we set the probabilities \(P_{ls}\) and bit-flip operation in LS as 0.1 and 4 / 500, respectively; the number of neighbors (\(N_{ls}\)) to be examined as 20. Therefore, for NSGA-III, we adopt the same configuration used in Deb and Jain (2014), i.e., the number of reference points (H) defines the population size N. For R-objective functions, if p divisions are considered along each objective, the authors in Deb and Jain (2014) define \(H=C_{R+p-1}^p\). In MOEA/D, the number of subproblems equals the population size N and the weight vectors \(\varvec{\lambda }^1,\ldots ,\varvec{\lambda }^N\) are controlled by the configuration parameter W, calculated as proposed in Zhang and Li (2007) (this is the same procedure used to generate the reference points in NSGA-III). As in Deb and Jain (2014), the size of the neighborhood for each weight vector is \(T=10\). MOEA/D considers the weighted sum approach.Footnote 2

The fitness calculation of \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{hype}\) is based on a hypervolume approximation using Monte Carlo simulation, as presented in HypE algorithm proposed by Bader and ZitzlerFootnote 3 (Bader and Zitzler 2011) due to the very expensive and time consuming computation of the exact hypervolume fitness (Bader and Zitzler 2011). This method generates random samples in the objective space and it counts the number of samples which are dominated by \(Pop^g\). The hypervolume is approximated by the ratio between the dominated and total samples. The number of samples used for Monte-Carlo approximation is 10,000.

4.2 Testing the influence of LS online configuration

The LS online configuration adopted by HMOBEDA during the evolution considers the following elements in the vector \({\mathbf {p}}\): the number of LS iterations \(N_{iter} \in \{5,6\ldots ,20\}\); the type of neighbor fitness calculation \(T_{Fnbh} \in \{1,2\}\): with (1) representing Linear Combination and (2) Alternation of included objectives (i.e. one objective after the other in each LS iteration); the neighborhood type \(T_{nbh} \in \{1,2\}\): with (1) defining drop-add and (2) insertion.

This paper aims to answer the question “What is the influence (on the HMOBEDA performance) of including LS parameters as BN nodes? As previously discussed, this is a relevant question since the automatic and informed determination of the LS parameters can notably improve the efficiency of the search.

As an attempt to answer this question, we modified the original version of HMOBEDA providing three other versions: \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{f}\), \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{f-inst}\) and \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{irace}\). None of these versions has LS parameter encoded as nodes in the PGM structure and all of them consider the same HMOBEDAparameters of Table 1.

In the LS off-line configuration adopted by the modified algorithms, the first version, \(\text {HMOBEDA}_f\), considers \(N_{iter}=19\), \(T_{Fnbh}=0\) and \(T_{nbh}=1\). These values represent the most frequent value of each LS-parameter provided by the original HMOBEDA in the set of non-dominated solutions, considering all the instances and executions. \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{f-inst}\) considers the same rule (i.e. the most frequent value found in all HMOBEDA executions) but now separated for each instance. In this case we have \(T_{Fnbh}=0\) and \(T_{nbh}=1\) for all instances; \(N_{iter}=18\) for 3-100, 2-250 and 4-250 instances; \(N_{iter}=10\) for 3-250; \(N_{iter}=19\) for 4-100; \(N_{iter}=16\) for 2-100 and 5-100; and \(N_{iter}=20\) for 8-100, 5-250 and 8-250 instances. \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{irace}\) considers \(N_{iter}=14\), \(T_{Fnbh}=0\) and \(T_{nbh}=1\). The LS off-line configuration method used for \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{irace}\) is I/F-Race (Birattari et al. 2010), which is a state-of-the-art automatic configuration method. We use the implementation of I/F-Race provided by the irace package (López-Ibáñez et al. 2011). As in López-Ibáñez and Stützle (2012), it performs the configuration process using the hypervolume (HV\(^-\)) as the evaluation criterion.

The same instances are used for training and testing off-line versions. The results obtained by \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{f}\) \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{f-inst}\) and \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{irace}\) are, thus, quite better than would be expected if the test instances were different.

Aiming to be as fair as possible, we define a stop condition based on the maximum number of fitness evaluations (\(Max_{eval}\)), which includes repair procedures and LS-iterations. Then, all algorithms stop when the total number of fitness computations achieve the value 100, 000. A total of 20 independent executions are conducted for each algorithm and from these results the performance metrics are computed.

4.3 Performance metrics

The optimal Pareto front for each instance of the addressed problem is not known. So, we use a reference set, denoted by Ref, which is constructed by gathering all non-dominated solutions obtained by all algorithms over all executions. Two main convergence-diversity (Jiang et al. 2014) metrics, usually adopted for measuring the quality of the optimal solution set for multi and many objective optimization, are then considered: Hypervolume (HV) (Zitzler and Thiele 1999; Bader 2009) and Inverted Generational Distance (IGD) (van Veldhuizen and Lamont 1999).

The hypervolume metric considers the difference (HV\(^-\)) between the hypervolume of the solution set of an algorithm and that of the reference set. The IGD metric is the average distance from each solution in the reference set to the nearest solution in the solution set. So, smaller values of HV\(^-\) and IGD correspond to higher quality solutions in non-dominated sets indicating both better convergence and good coverage of the reference set.

4.4 Numerical results

In this section we aim to compare the results of HMOBEDA, \(\text {HMOBEDA}_f\), \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{f-inst}\), \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{irace}\), \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{hype}\), MOEA/D, MBN-EDA, NSGA-II, NSGA-III and S-MOGLS.

Table 2 shows the hypervolume difference (HV\(^-\)) and IGD metric, both averaged over 20 executions of each algorithm. The lowest values are highlighted (in bold). We use PISA framework (Bleuler et al. 2003) to compute HV\(^-\) and Matlab to compute IGD.

We note, in Table 2, that HMOBEDA always produces the lowest average values for HV\(^-\) (except in 2–500 instance, where MOEA/D has competitive values for both HV\(^-\) and IGD). Regarding IGD metric, NSGA-III achieves lower average values for instances that have 2, 3 and 4 objectives with 100 items, and \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{hype}\) has the lowest average value for 5–250. However the remaining instances stand HMOBEDA as a competitive approach.

The analysis is now expanded to include statistical tests. First we aim to analyze the use of CD versus hypervolume as tie-breaker criterion comparing HMOBEDAwith \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{hype}\). Then we proceed with the analysis by evaluating the influence of LS online configuration based on BN nodes, comparing the original HMOBEDA with its off-line configured versions. Then, we define the standard version that will be further compared with other approaches reported in the literature.

Based on the Shapiro-Wilk normality test (Conover 1999) we have concluded that HV\(^-\) and IGD results are not normally distributed. Then, the Kruskal-Wallis test has been applied for statistical analysis (Casella and Berger 2001) of the results for the LS off-line versions, and the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test for \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{hype}\). All tests have been executed with a significance level of \(\alpha =0.05\).

First we compare HMOBEDA with \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{hype}\), and then, with its off-line modified versions. The results of the test reveal that the null hypothesis that all the algorithms have HV\(^-\) values with no statistically significant difference can be rejected for all instances. The same hypothesis can be rejected in the case of IGD. In case of the comparison with the off-line modified versions, a post-hoc analysis is performed to evaluate which algorithms present statistically significant difference.

Table 3 shows the statistical analysis of pairwise comparisons between HMOBEDA and \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{hype}\) for each instance with respect to HV\(^-\) and IGD values. In Table 4 the numbers in parentheses show the results of pairwise comparisons between HMOBEDA and off-line algorithms using Dunn-Sidak’s post-hoc test with a significance level of \(\alpha = 0.05\). For both tables, the first number shows how many algorithms are better than the algorithm listed in the corresponding line, and the second number shows how many algorithms are worse. The entry related to the algorithm with the lowest (best) average metric is emphasized (bold).

HMOBEDA presents statistically significant differences in comparison with \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{hype}\) for 2–250, 5–100, 8–100 and 8–250, and regarding only IGD metric, for 2–100, 3–100, 3–250, 4–100, 4–250 and 5–250 instances.

There is no statistically significant differences between HMOBEDA and \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{hype}\) for instances 2–100, 3–100, 3–250, 4–100 and 4–250 for (HV\(^-\)) metric. Regarding IGD metric, HMOBEDA’s results present statistically significant differences for almost all instances, except in 5–250, where \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{hype}\) presents the lowest metric value.

We can now analyze the influence of including LS-parameters in the PGM structure. HMOBEDA shows statistically significant differences in comparison with its off-line modified versions for almost all instances, particularly those with high number of objectives and variables (5–100, 4–250, 8–100 and 8–250), where HMOBEDA is better than the other three algorithms. There is no statistically significant differences between HMOBEDA and \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{irace}\) for instance 4–100 for both HV\(^-\) and IGD values. For all instances with 4, 5 and 8 objectives, HMOBEDA is better than \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{f-inst}\) and \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{f}\).

These results justify, in our opinion, the relevance of adding LS parameters into the probability model, and we assume that HMOBEDA is better or at least equal to its modified versions with LS off-line configuration. We also conclude that despite using less computational resources, HMOBEDA is competitive with \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{hype}\). So, we define HMOBEDA as our standard version and it will be compared with other traditional approaches.

Table 5 shows the statistical analysis of the results considering the other approaches. The same methodology adopted in the comparison HMOBEDA versus its off-line modified versions is considered here.

The analysis of Table 5 reveals that the proposed approach shows statistically significant differences with almost all other algorithms (except for instances with 2 objectives with respect to the IGD metric, where there is no statistically significant differences between all the algorithms). It also shows that both HV\(^-\) and IGD present consistent results.

For instances 3–100 in both HV\(^-\) and IGD metrics, the performances of MBN-EDA, NSGA-II, S-MOGLS and MOEA/D do not present statistically significant differences and all of them are worse than HMOBEDA (which has similar performance to NSGA-III), indicating that HMOBEDA is better than four other approaches- (0, 4). Also, for instances 4–100, there is no statistically significant differences between the HV\(^-\) performance of HMOBEDA and NSGA-III (both are better than other four algorithms- (0, 4)). Considering the IGD performance, HMOBEDA , NSGA-III and MOEA/D are better than MBN-EDA, NSGA-II and S-MOGLS. MOEA/D is better than two (MNB-EDA and NSGA-II) and worse than one (NSGA-III)- (1, 2).

Another example can be seen for instances 3-250, both HV\(^-\) and IGD performances do not present statistically significant differences between HMOBEDA, NSGA-III and MOEA/D. Regarding IGD, MOEA/D are not better nor worse than any other approach- (0, 0). For the remaining instances we can conclude that, based on HV\(^-\) and IGD, HMOBEDA has the best performance among the compared approaches.

Therefore, we can affirm that HMOBEDA is a competitive approach for the instances considered in this work. We have observed that it is better than the compared approaches, except for instances of small size where there is no statistically significant difference between HMOBEDA, NSGA-III and MOEA/D. Also, HMOBEDA is better than its off-line modified versions, which evidences that the flexibility imposed by modeling LS parameters as nodes of the PGM model results in benefits to the hybrid model encompassing variables and objectives. Finally, results show that the use of hypervolume instead of crowding distance is not beneficial, as it does not improve the performance and still increases the computational cost of the approach.

The average run time for each algorithm is presented in Table 6.

We can observe in Table 6 that the computational efforts for each algorithm are in the same time scale, keeping the runtime at practical levels. However, increasing the number of objectives and variables severely impacts the average computational time of all approaches. We also include statistical tests in order to compare the run time for all instances considering the total number of executions. Table 7 shows the results for pairwise comparisons among HMOBEDA and all other algorithms. The entry with the lowest average run time is emphasized in bold.

We can observe that HMOBEDA and off-line variations, NSGA-III and MOEA/D do not present statistically significant differences between its execution times for almost all instances. \(\text {HMOBEDA}_{hype}\) has the highest computational time for all instances due to the intensive calculations necessary to compute hypervolumes. Note that we are mainly interested in the quality of the solution. Thus, the run time is given only for guidance.

4.5 PGM structure analysis

In order to discuss the learned PGM structures we provide an interpretation of the probabilistic model resulted at the end of evolution for 2–100 and 8–100 instances. These instances correspond to examples of easy bi-objective and difficult many objective optimization instances, respectively.

Figure 3 shows the interactions (blue circles) between each decision variable \(X_q\), \(q \in \{1,\ldots ,100\}\), and the objectives \(Z_1\) and \(Z_2\), learned by the BN for the 2–100 instance. Each circle has coordinates indicating the number of times an arc \((Z_1,X_q)\) has been captured along the evolutionary process for all executions versus a similar measure for arc \((Z_2,X_q)\). Note that the interaction is quite similar for the two objectives, since most of points are located nearby the +1 slope line. In other words, based on Fig. 3, we can conclude that variables (specially if the number of interactions for a given variable is either very low or very high) are equally affected by both objectives.

Figure 4 focuses on the analysis of BN structure concerning the relations between objectives and LS parameters for the 8–100 instance. The relations between each objective and the three LS parameters considered in this paper are illustrated by star glyphs. In such representation, each spoke represents one parameter \(P_l\) and it is proportional to the number of times the arc \((Z_r,P_l)\), \(l \in \{1,2,3\}\), \(r\in \{1,\ldots ,8\}\), has been captured along the evolutionary process for all executions. The glyphs allow us to visualize which is the relative strength of the relations. For example, it can be seen in Fig. 4 that objectives \(Z_1\) and \(Z_6\) have small influence on the way the parameters are instantiated. On the other hand, \(Z_3\) and \(Z_7\) have great influence, although \(Z_3\) is better balanced among the parameters than \(Z_7\).

In this section we have aimed to illustrate one of the main advantages of using EDAs: the possibility of scrutinizing its probabilistic model which usually encompasses useful information about the relationship among variables. We have shown with two examples that HMOBEDA model allows a step forward. First, it is possible to estimate the relevance that the variables have on the objectives, from the analysis of how frequent objective-variable interactions are. Second, it is possible to determine how sensitive are the different objectives to the setting of the distinct local search parameters from the analysis of the frequency of the objective-parameters interactions. Notice that while, for sampling purposes, objectives are set as parents of variables and of local search parameters, the quality of the solutions, i.e., the objective values are the ones sensitive to the variables and parameters assignments.

5 Conclusions and future work

In this paper we have analyzed a new MOEDA based on Bayesian Network in the context of multi and many objective optimization. The approach named HMOBEDA has a hill climbing procedure embedded in the probabilistic model as a local optimizer. We have thus incorporated a local search (LS) procedure to exploit the search space and a joint probabilistic model of objectives, variables and LS parameters to generate new individuals through the sample process. The Bayesian network is learned using the K2 method and since the LS parameters are part of the network, they are adapted as the algorithm evolves.

The main issue investigated in this paper concerns whether the auto-adaptation of LS parameters improves the search by allowing the Bayesian network to represent and set these parameters. We have thus modified the original HMOBEDA to build three other off-line versions with no LS parameter encoded as a node in the probabilistic model. The first version (\(\text {HMOBEDA}_f\)) is based on the best LS parameters found by HMOBEDA. The second version (\(\text {HMOBEDA}_{f-ins}\)) is specialized for each instance by setting the LS parameters to the best ones found by HMOBEDA for that instance. The third version (\(\text {HMOBEDA}_{irace}\)) defines the LS parameters through the irace package. We have also implemented an online configuration of HMOBEDA based on the hypervolume indicator (\(\text {HMOBEDA}_{hype}\)) as part of the selection procedure. We have analyzed the performance of the proposed approaches for ten instances of the multi-objective knapsack problem, considering two traditional metrics: Hypervolume (HV\(^-\)) and Inverted Generational Distance (IGD).

Based on the experiments with the MOKP instances addressed in this work, we can conclude that the inclusion of online configuration of the LS parameters is beneficial for HMOBEDA. In other words, the online parameter setting based on the PGM is more effective than fixing good parameters along optimization. We have shown that the better performance of the proposed approach is more related with the probabilistic model than with LS: as modified versions of HMOBEDA using different tuned LS parameters did not provide the same trade-off. Another conclusion is that using hypervolume instead of crowding distance as a tie-breaker neither improves the solution found nor presents good computational cost.

We have also concluded that the proposed hybrid EDA is competitive when compared with the other evolutionary algorithms investigated. One possible explanation points to the fact that since the LS parameters are in the same probabilistic model, HMOBEDA provides an automatic and informed decision at the time of setting these parameters. Thus a variety of non-dominated solutions can be found during different stages of the evolutionary process. This finding is relevant for the development of other adaptive hybrid MOEAs. Probabilistic modeling arises as a sensible and feasible way not only to learn and explore dependencies between variables and objectives but also to automatically control the application of local search operators.

An analysis of the resulting BN structures has also been carried to evaluate how the interactions among variables, objectives and local search parameters are captured by the BNs. As a way to illustrate the types of information that can be extracted from the models, we have shown how the frequency of arcs in the BNs indicate that the variables of the 2–100 instance have a similar influence on both objectives. For 8–100 instance, a similar analysis shows that LS parameters are more related to objectives \(Z_3\) and \(Z_7\) than to the others. This illustrative analysis can be further extended.

In the future, MOEA techniques other than Pareto-based approaches should be examined, such as scalarizing functions, for example. These new approaches should be investigated with more than eight objectives. Beyond that, we intend to relax some of the current restrictions of our model to represent reacher types of interactions (e.g., dependencies between variables). Consequently, other classes of methods to learn the BN structures, such as constraint based (Aliferis et al. 2010; Tsamardinos et al. 2003) and hybrid (Tsamardinos et al. 2006) methods could be investigated.

Finally, we intend to compare HMOBEDA with a larger set of traditional approaches, including a baseline method commonly used in hyperheuristics contexts which randomly generates LS parameters.

Notes

The discretization process converts each objective value into \(sd_r\) discrete states considering the maximum possible value for each objective (\(Max_r\)). For each objective r, its discrete value is calculated as \( zd_r = \left\lceil z_r sd_r / Max_r \right\rceil \).

This implementation is used in Bader and Zitzler (2011) for more than three objectives and can be downloaded from http://www.tik.ee.ethz.ch/sop/download/supplementary/hype/.

References

Aliferis, C.F., Statnikov, A., Tsamardinos, I., Mani, S., Koutsoukos, X.D.: Local causal and markov blanket induction for causal discovery and feature selection for classification part i: algorithms and empirical evaluation. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 11, 171–234 (2010)

Bader, J., Zitzler, E.: Hype: an algorithm for fast hypervolume-based many-objective optimization. IEEE Trans. Evolut. Comput. 19(1), 45–76 (2011)

Bader, J.M.: Hypervolume-based search for multiobjective optimization: theory and methods. Ph.D. thesis, ETH Zurich, Zurich (2009)

Bengoetxea, E.: Inexact graph matching using estimation of distribution algorithms. Ph.D. thesis, University of the Basque Country, Basque Country (2002)

Bengoetxea, E., Larrañaga, P., Bielza, C., Del Pozo, J.F.: Optimal row and column ordering to improve table interpretation using estimation of distribution algorithms. J. Heuristics 17(5), 567–588 (2011)

Birattari, M., Yuan, Z., Balaprakash, P., Stützle, T.: F-Race and Iterated F-Race: An Overview, pp. 311–336. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg (2010)

Bleuler, S., Laumanns, M., Thiele, L., Zitzler, E.: PISA—a platform and programming language independent interface for search algorithms. In: Evolutionary Multi-criterion Optimization (EMO 2003). Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pp. 494–508. Berlin (2003)

Casella, G., Berger, R.L.: Statistical Inference, 2nd edn. Duxbury, Pacific Grove, CA (2001)

Coello, C.A.C.: An updated survey of evolutionary multiobjective optimization techniques: state of the art and future trends. In: IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation, pp. 3–13 (1999)

Conover, W.: Practical Nonparametric Statistics, third edn. Wiley, Hoboken (1999)

Cooper, G., Herskovits, E.: A bayesian method for the induction of probabilistic networks from data. Mach. Learn. 9(4), 309–347 (1992)

Corriveau, G., Guilbault, R., Tahan, A., Sabourin, R.: Bayesian network as an adaptive parameter setting approach for genetic algorithms. Complex Intell. Syst. 2(1), 1–22 (2016)

Crocomo, M.K., Delbem, A.C.B.: Otimização por Decomposição. Tech. report São Carlos (2011)

Deb, K.: Multi-objective Optimization Using Evolutionary Algorithms. John Wiley and Sons, New York (2001)

Deb, K., Jain, H.: An Evolutionary many-objective optimization algorithm using reference-point-based nondominated sorting approach, part i: solving problems with box constraints. IEEE Trans. Evolut. Comput. 18(4), 577–601 (2014)

Deb, K., Agrawal, S., Pratab, A., Meyarivan, T.: A fast and elitist multi-objective genetic algorithm: NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evolut. Comput. 6, 182–197 (2002)

DeGroot, M.H.: Optimal Statistical Decisions, vol. 82. John Wiley & Sons, Complex (2005)

Etxeberria, R., Larrañaga, P.: Global optimization using Bayesian networks. In: Proceedings of the Second Symposium on Artificial Intelligence (CIMAF-99), pp. 332–339 (1999)

Freitas, ARRd, Guimarães, F.G., Silva, R.C.P., Souza, M.J.F.: Memetic self-adaptive evolution strategies applied to the maximum diversity problem. Optim. Lett. 8(2), 705–714 (2014)

Harik, G.: Linkage learning via probabilistic modeling in the eCGA. Urbana 51(61), 801 (1999)

Hauschild, M., Pelikan, M.: An introduction and survey of estimation of distribution algorithms. Swarm Evolut. Comput. 1(3), 111–128 (2011)

Heckerman, D., Geiger, D., Chickering, D.: Learning bayesian networks: the combination of knowledge and statistical data. Mach. Learn. 20(3), 197–243 (1995)

Ishibuchi, H., Akedo, N., Nojima, Y.: Behavior of multiobjective evolutionary algorithms on many-objective knapsack problems. IEEE Trans. Evolut. Comput. 19(2), 264–283 (2015)

Ishibuchi, H., Hitotsuyanagi, Y., Nojima, Y.: Scalability of multiobjective genetic local search to many-objective problems: knapsack problem case studies. In: Evolutionary Computation, 2008. CEC 2008. (IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence), pp. 3586–3593 (2008)

Ishibuchi, H., Tsukamoto, N., Nojima, Y.: Evolutionary many-objective optimization: a short review. In: 2008 IEEE Congress on Evolutionary Computation (IEEE World Congress on Computational Intelligence), pp. 2419–2426 (2008)

Jiang, S., Ong, Y.S., Zhang, J., Feng, L.: Consistencies and contradictions of performance metrics in multiobjective optimization. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 44(12), 2391–2404 (2014)

Karshenas, H., Santana, R., Bielza, C., Larrañaga, P.: Multiobjective estimation of distribution algorithm based on joint modeling of objectives and variables. IEEE Trans. Evolut. Comput. 18, 519–542 (2014)

Ke, L., Zhang, Q., Battiti, R.: A simple yet efficient multiobjective combinatorial optimization method using decomposition and Pareto local search. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 44, 1808–1820 (2014)

Kollat, J.B., Reed, P., Kasprzyk, J.: A new epsilon-dominance hierarchical Bayesian optimization algorithm for large multiobjective monitoring network design problems. Adv. Water Resour. 31(5), 828–845 (2008)

Korb, K.B., Nicholson, A.E.: Bayesian Artificial Intelligence, second edn. CRC Press, Boca Raton (2010)

Lara, A., Sanchez, G., Coello, C.A.C., Schutze, O.: HCS: a new local search strategy for memetic multiobjective evolutionary algorithms. IEEE Trans. Evolut. Comput. 14(1), 112–132 (2010)

Larrañaga, P., Karshenas, H., Bielza, C., Santana, R.: A review on probabilistic graphical models in evolutionary computation. J. Heuristics 18, 795–819 (2012)

Larrañaga, P., Karshenas, H., Bielza, C., Santana, R.: A review on evolutionary algorithms in Bayesian network learning and inference tasks. Inf. Sci. 233, 109–125 (2013)

Larrañaga, P., Lozano, J.A.: Estimation of Distribution Algorithms: A New Tool for Evolutionary Computation, vol. 2. Springer, Netherlands (2002)

Laumanns, M., Ocenasek, J.: Bayesian optimization algorithms for multi-objective optimization. In: Parallel Problem Solving from Nature-PPSN VII. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 2439, 298–307 (2002)

Li, H., Zhang, Q., Tsang, E., Ford, J.A.: Hybrid Estimation of distribution algorithm for multiobjective knapsack problem. Evolut. Comput. Combin. Optim. 3004, 145–154 (2004)

López-Ibáñez, M., Dubois-Lacoste, J., Stützle, T., Birattari, M.: The irace package: iterated racing for automatic algorithm configuration. IRIDIA Technical Report Series 2011-004, Universit? Libre de Bruxelles, Bruxelles,Belgium (2011). http://iridia.ulb.ac.be/IridiaTrSeries/IridiaTr2011-004.pdf

López-Ibáñez, M., Stützle, T.: The automatic design of multiobjective ant colony optimization algorithms. IEEE Trans. Evolut. Comput. 16(6), 861–875 (2012). doi:10.1109/TEVC.2011.2182651

Luna, J.E.O.: Algoritmos EM para Aprendizagem de Redes Bayesianas a partir de Dados Imcompletos. Master thesis, Universidade Federal do Mato Grosso do Sul, Campo Grande (2004)

Luque, M.: Modified interactive chebyshev algorithm (MICA) for non-convex multiobjective programming. Optim. Lett. 9(1), 173–187 (2015)

Martins, M.S., Delgado, M.R., Santana, R., Lüders, R., Gonçalves, R.A., Almeida, C.P.d.: HMOBEDA: Hybrid Multi-objective Bayesian estimation of distribution algorithm. In: Proceedings of the 2016 on Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference, GECCO ’16, pp. 357–364. ACM, New York, NY, USA (2016)

Mühlenbein, H., Mahnig, T.: Convergence theory and applications of the factorized distribution algorithm. J. Comput. Inf. Theory 7(1), 19–32 (1999)

Mühlenbein, H., Paab, G.: From recombination of genes to the estimation of distributions I. Binary parameters. In: Parallel Problem Solving from Nature-PPSN IV. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 1411, pp. 178–187 (1996)

Pearl, J.: Probabilistic Reasoning in Intelligent Systems: Networks of Plausible Inference. Morgan Kaufmann, San Mateo CA (1988)

Pelikan, M.: A simple implementation of the Bayesian optimization algorithm (BOA) in c++(version 1.0). Illigal Report 99011 (1999)

Pelikan, M., Goldberg, D.E., Cantú-Paz, E.: BOA: The Bayesian optimization algorithm. In: Proceedings of the Genetic and Evolutionary Computation Conference GECCO-1999, vol. I, pp. 525–532. Orlando, FL (1999)

Pelikan, M., Goldberg, D.E., Tsutsui, S.: Hierarchical Bayesian optimization algorithm: toward a new generation of evolutionary algorithms. In: SICE 2003 Annual Conference, vol. 3, pp. 2738–2743. IEEE (2003)

Pelikan, M., Muehlenbein, H.: The Bivariate Marginal Distribution Algorithm, pp. 521–535. Springer London, London (1999)

Pham, N.: Investigations of constructive approaches for examination timetabling and 3d-strip packing. Ph.D. thesis, School of Computer Science and Information Technology, University of Nottingham (2011). http://www.cs.nott.ac.uk/~pszrq/files/Thesis-Nam.pdf

Russel, S.J., Norvig, P.: Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach, 2nd edn. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey (2003)

Santana, R., Larrañaga, P., Lozano, J.A.: Learning factorizations in estimation of distribution algorithms using affinity propagation. IEEE Trans. Evolut. Comput. 18(4), 515–546 (2010)

Santana, R., Larrañaga, P., Lozano, J.A.: Combining variable neighborhood search and estimation of distribution algorithms in the protein side chain placement problem. J. Heuristics 14, 519–547 (2008)

Schwarz, J., Ocenasek, J.: Multiobjective Bayesian optimization algorithm for combinatorial problems: theory and practice. Neural Netw. World 11(5), 423–441 (2001)

Shah, R., Reed, P.: Comparative analysis of multiobjective evolutionary algorithms for random and correlated instances of multiobjective d-dimensional knapsack problems. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 211(3), 466–479 (2011)

Shakya, S., Santana, R.: An EDA based on local markov property and gibbs sampling. In: Proceedings of the 10th Annual Conference on Genetic and Evolutionary Computation, GECCO ’08, pp. 475–476. ACM, New York, NY, USA (2008). doi:10.1145/1389095.1389185

Shim, V.A., Tan, K.C., Chia, J.Y., Al Mamun, A.: Multi-objective optimization with estimation of distribution algorithm in a noisy environment. Evolut. Comput. 21(1), 149–177 (2013)

Srinivas, N., Deb, K.: Multiobjective optimization using nondominated sorting in genetic algorithms. Evolut. Comput. 2, 221–248 (1994)

Tan, Y.Y., Jiao, Y.C.: MOEA/D with Uniform design for solving multiobjective knapsack problems. J. Comput. 8, 302–307 (2013)

Tanigaki, Y., Narukawa, K., Nojima, Y., Ishibuchi, H.: Preference-based NSGA-II for many-objective knapsack problems. In: 7th International Conference on Soft Computing and Intelligent Systems (SCIS) and Advanced Intelligent Systems (ISIS), pp. 637–642 (2014)

Tsamardinos, I., Aliferis, C.F., Statnikov, A.R., Statnikov, E.: Algorithms for large scale markov blanket discovery. In: FLAIRS conference 2, 376–380 (2003)

Tsamardinos, I., Brown, L.E., Aliferis, C.F.: The max-min hill-climbing bayesian network structure learning algorithm. Mach. learn. 65(1), 31–78 (2006)

van Veldhuizen, D.A., Lamont, G.B.: Multiobjective evolutionary algorithm test suites. In: Proceedings of the 1999 ACM Symposium on Applied Computing, SAC ’99, pp. 351–357. ACM, New York, NY, USA (1999)

Vianna, D.S., de Fátima Dianin Vianna, M.: Local search-based heuristics for the multiobjective multidimensional knapsack problem. Produção 23, 478–487 (2013)

Wang, L., Wang, S., Xu, Y.: An effective hybrid EDA-based algorithm for solving multidimensional knapsack problem. Expert Syst. Appl. 39, 5593–5599 (2012)

Zhang, Q., Li, H.: MOEA/D: a multiobjective evolutionary algorithm based on decomposition. IEEE Trans. Evolut. Comput. 11(6), 712–731 (2007)

Zhou, A., Qu, B.Y., Li, H., Zhao, S.Z., Suganthanb, P.N., Zhang, Q.: Multiobjective evolutionary algorithms: a survey of the state of the art. Swarm Evolut. Comput. 1, 32–49 (2011)

Zhou, A., Sun, J., Zhang, Q.: An estimation of distribution algorithm with cheap and expensive local search methods. IEEE Trans. Evolut. Comput. 19(6), 807–822 (2015)

Zitzler, E., Thiele, L.: Multiple objective evolutionary algorithms: a comparative case study and the strength Pareto approach. IEEE Trans. Evolut. Comput. 3, 257–271 (1999)

Zitzler, E., Thiele, L., Deb, K.: Comparison of Multiobjective evolutionary algorithms: empirical results. IEEE Tran. Evolut. Comput. 8(2), 173–195 (2000)

Acknowledgements

M. Delgado acknowledges CNPq Grant 309197/2014-7. M. Martins acknowledges CAPES/Brazil. R. Santana acknowledges support by: IT-609-13 Program (Basque Government), TIN2013-41272P (Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation) and CNPq Program Science Without Borders No. 400125/2014-5 (Brazil Government).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martins, M.S.R., Delgado, M.R.B.S., Lüders, R. et al. Hybrid multi-objective Bayesian estimation of distribution algorithm: a comparative analysis for the multi-objective knapsack problem. J Heuristics 24, 25–47 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10732-017-9356-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10732-017-9356-7