Abstract

Documentation of diversity and assessment of cultural importance of wild edible plants gathered and consumed in Ulleung Island, South Korea was conducted in this research by asking 83 key informants (average age 70) using semi-structured interview questionnaire, and utilizing quantitative ethnobotanical indices such as use value (UV) and fidelity level (FL). A total of 66 taxa in 36 families of wild food plants were recorded, 10 of which, endemic. Asteraceae and Rosaceae were the most represented families with 10 taxa for each. Leaves, young shoots and fruits were the most collected plant parts especially in spring. The plants which recorded high UVs were Allium ochotense (0.627), Aster pseudoglehnii (0.398) and Aruncus dioicus var. kamtschaticus (0.349), indicating that these plants are considered the most important by the informants. This study also recorded 29 wild edible plant taxa with 100 % FL values. Notable plants (and their preparation) with relatively high FL and use-mentions are Vitis coignetiae (89.47 %), Anthriscus sylvestris (86.67 %) and Lilium hansonii (86.67 %) which are consumed as fruit, prepared by parboiling the shoots and by steaming the bulbs, respectively. Category 5 “Cooked” (COO) was the most preferred mode of preparation when taken as a whole recording 49 % of the total, implying that wild edible plants play a big role in the informants’ regular diet despite growing modernization in the island brought about by government-led tourism and infrastructure development programs. Some social, cultural, nutritional and ecological aspects were also discussed in this paper.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The last few decades have seen renewed social and even scientific interests in wild edible plants as food resource in spite of the general trend of decline in the habit of gathering and consumption. The growing interests in the use of wild food plant re-sources nowadays may have stemmed from efforts to find alternatives to the industrialization and globalization of agriculture, and to provide food security in times of agricultural crisis (Turner et al. 2011).

The same interests in wild food plants published in recent ethnobotanical studies are also evident in South Korea (hereafter Korea) (Song et al. 2013; Kim and Song 2013), including their use in relation to Korean Buddhism (Kim et al. 2006). Many wild food plants that are gathered from fields and forests and sold in food markets in Korea, or are exported to the US had been reported as well (Pemberton and Lee 1996). Wild-gathered edible food plants found in the markets had also been previously documented in the past, either in the two published works dealing specifically with wild edible plants of Korea (Hayashi and Kawamoto 1942; Lee 1969) or Tanaka’s encyclopedia (1976) which contains most of the edible plants of temperate Asia.

The commonly used food plants in Korean diet are very diverse. In addition to cultivated vegetables such as radish, cabbages and pepper, wild edible greens are also regularly collected and consumed. It is reported that over 300 types of vegetables are eaten in rural areas all over the country (Lee et al. 2002). Hence, it may be worth assuming that despite its modernization, Korea has maintained its own traditional food ways, and the use of various plants is deeply rooted in its diet and culture.

Wild sources of food in Korea were especially important during times of conflict and famine (e.g. World War II and the Korean War), when normal food supply was disrupted and locally displaced populations had limited access to other food source. But even under normal conditions, wild plants have played an important role in complementing staple foods to provide a balanced diet by supplying trace elements, vitamins and minerals, and may do so again in future times of crisis (Tardio et al. 2006).

Geographically, the Korean peninsula is widely known as a mountainous region politically composed of two countries, North Korea (DPRK) and South Korea (ROK). However, only less is known that ROK alone is made up of about 3400 islands. Most of these islands are located relatively far from the peninsula, thus in comparison with regions in the mainland, are less developed territories of the country which began its industrialization in the 1960s. In 1986, the Islands Development Promotion Law was enacted by the national government to improve island residents’ income and welfare by establishing agri-production, as well as cultural and social welfare facilities. The implementation of projects started in 1988 on a 10-year cycle and first resulted in the publication of the Second Islands Integrated Development Plan in 2007. The second and current cycle started in 2008 and works towards the third development plan. The purpose of this program is to create and develop ‘‘attractive islands’’ for tourism and to solve the isolation of these islands by expanding infrastructure projects such as construction of bridges to ensure stable progress (Kim 2013).

With these continuous development and modernization in the surrounding islands of Korea, we believe that particular insular traditions such as the collection and consumption of wild edible plants are at risk of changing, or worse disappearing. Also, as the country became an aging society in 2000 (Kim 2010), there is greater possibility that traditional ecological knowledge, which is held by most elderly people may be lost if appropriate measures are not made. Hence, an ethnobotanical study of the wild edible plants is one of the feasible approaches in finding ways to document this knowledge, and increase the diversity of the plant foods Koreans consume by finding potential plant candidates for cultivation.

Objectives

This study was conducted for the purpose of preserving the traditional knowledge of collection, preparation, storage and consumption of wild edible plants by Korean islanders. The research is part of a major ethnobotanical and ethnographic project to document the wild food plants gathered from three groups of islands (west, south and east regions) surrounding South Korea, as well as in regions in the main peninsula by the Korea National Arboretum (Chung et al. 2013). Specifically, the objective of this research was (1) to document the diversity of wild food plants gathered in Ulleung Island and (2) to assess the cultural value of these plants, especially their role in local nutrition and traditional diet as taken from the socio-economic and socio-anthropological perspectives of the informants.

Materials and methods

Research site

Ulleung Island (Ulleungdo as known locally) is a small oceanic island with volcanic origin, and lies on East Sea between the Korean peninsula and Japanese archipelago. It is 137 km apart east of mainland Korea and is 73 km2 in area with a maximum elevation of 984 m. Ulleung Island is the civilian-inhabited island of around 10,000 in the eastern island group with around 44 more inhabitable islets lay around, including Dokdo. Historically, the island had no settled inhabitants from 1438 to around 1883 due to the “empty island policy” implemented by the then ruling dynasty mainly because of the island’s remoteness and difficulty to govern (Chu 2008). The first immigrants (who were farmers from the mainland) to the island depended mostly on vegetation for their survival and economy until Ulleung Island became a major fishing industry, especially for cuttlefish.

As a volcanic island far situated from the mainland with many areas of rough terrain, it is home to a wealth of unusual flora and fauna. Ulleungdo which literally means “mysterious island” is so-named because, for most of its history, its contents have remained largely unknown and open to imaginative speculation (Mills and Park 2013). Early visitors sensationally reported an abundance of strange “water beasts” (seals), and other large land mammals (Chu 2008). Botanically, the island has 487 native vascular plant taxa, among which 36 are endemics (Chung et al. 2011).

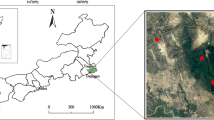

The average temperature of the warmest month (August) is 23.4 °C and that of the coldest month (January) is 1.3 °C. The average annual temperature and precipitation, however, is 12.3 °C and 1236.2 mm, respectively. In addition, the island also receives 1 m of snowfalls on average and around 3 m at the heaviest. This small island is environmentally valuable for preservation because it functions as a stopover location for a lot of migratory birds, and has unique geographical and geological features which are of great potential both in tourism and biology (Ministry of Environment 2004). Ulleung Island has also been declared as a national geo park recently (CBD Korea 2014). Figure 1 presents the research site and areas where participants were sampled.

Informants and sampling

A total of 83 key informants (male = 35, female = 48) from 22 areas representing different localities in Ulleung Island (see Fig. 1) and who have lived most of their lives in the island were interviewed from 2009–2014. The age of the informants ranges from 38 to 91 years old with an average age of 70. The participants were selected for their knowledge and experience in gathering and consumption of wild edible plants. Snowball sampling was the method used in choosing the informants, wherein one recommends another as the next resource person.

Interview

The interview was conducted and recorded in Korean language and was translated to English consequently. Romanization of Korean words followed the Revised Romanization of Korean (also called Ministry of Culture 2000), the most widely accepted system for Korean language. A clear expression of approval was obtained before each interview, oftentimes visiting senior citizens center and village leaders for consent. The informants were also given small tokens of appreciation for their time and cooperation. In addition, copies of future outputs (in Korean) were agreed to be sent to the participants in order to aid in the preservation of traditional ecological knowledge. In general, the field study followed the ethical guidelines adopted by the International Society of Ethnobiology (ISE 2006).

Data gathered from the informants were conducted by freelisting, followed by asking the informants questions about their direct experience in gathering and consumption of wild edible plants using semi-structured interview questionnaires. Each participant was interviewed in isolation when possible in order to avoid one informant’s answer influencing another’s response and to create an atmosphere conducive to memory recall. Inquiries were focused on knowledge about past and present use, mode of preparation and consumption, plant parts used, place of collection, distribution and availability, season of collection, and methods and period of storage. In some cases, detailed information about food preparations and recipes were recorded by our team of researchers composed of plant taxonomists and persons knowledgeable of the local landscape and culture.

Plant collection and identification

Voucher specimens were collected during flowering or fruiting season, and were identified and deposited at the Korea National Herbarium (KH) for documentation. The local names of plants, as well as the local terms of their uses were also documented. Scientific names were determined by identifying herbarium specimens and by referring to several Korean floras (Lee 1979, 2006, 2007). Scientific names of plants followed those used in the Korean Plant Names Index (Korea Forest Service 2010).

Wild edible plants determination

This study delimited the documentation of wild foods to higher plants that are gathered only for food consumption and not for medicinal purposes, with exception to some plants used as herbal tonic drinks. The determination of whether a plant was edible (or not) was done by referring to Lee (1969), and by cross checking against the list of cultivated plants by Hoang et al. (1997), which is a compilation of previous checklists of all types of Korean cultivated plants (Baik et al. 1986; Hammer et al. 1987; Hoang and Hammer 1988; Hammer et al. 1989, 1990). In general, however, plants which were not known to be cultivated for food were assumed wild by the authors, and plants partially cultivated or managed according to informants were all considered wild.

Wild food plants category

In order to determine the number of use-reports gathered from each informant, data were grouped into eight wild food plants use categories based on folk perceptions, previous related studies, plant parts and preparations. (1) “Fruits” (FRU) includes nuts and seeds that are eaten fresh when ripe or mature without further preparation. (2) “Beverages” (BEV) is further divided into two subcategories such as (2a) “Liquors” (BEVLi) which includes plant parts (usually fruits) fermented into alcohol or infused together with it, and (2b) “Herbal teas and juice” (BEVHe) which may also be used as digestives. (3) “Extracts” (EXT) are plant-derived extracts such as sap, oil, latex or resin which may be used as cooking ingredients or consumed directly. (4) “Fermented” (FER) comprises plants prepared using fermentation method, and is further classified into three subcategories (Steinkraus 1997) as follow: (4a) “Lactic acid fermented food” (FERLa) includes Korean-style pickled plant food (kimchi) usually by adding chili pepper and salt, (4b) “High salt fermented food” (FERSa) which includes the use of soy sauce (ganjang) in food preservation, and (4c) “Vinegar fermented food” (FERVi) which also includes plant parts fermented into vinegar. (5) “Cooked” (COO) includes plant parts such as immature fruits/seeds that are not processed or whose compositions are not altered (unlike dried and powdered plant products), and are usually prepared in a regular meal. This category is further divided into three subcategories modified from previous nutritional studies (Yoo et al. 2000; Heo and Lee 1999) and are as follow: (5a) “Non-heat” (COONo) comprises food wraps and salads, and may also be freshly prepared with sauce, condiments and other seasoning ingredients, (5b) “Heat” (COOHe) which includes soups and other dishes prepared using heating methods (e.g. parboiling, frying, steaming etc.), and (5c) “Dry” (COODr) that includes air or sun drying methods (or may be initial blanching before drying) prior to the final cooking process by applying heat. (6) “Raw” (RAW) includes plant parts (other than fruits) which are eaten without preparation and/or not usually served in a regular meal. (7) “Processed” (PRO) comprises plant parts that are made into sweet preserves or plant parts which may not be distinguishable from their original form/texture (e.g. dried and powdered), and/or are used as ingredients for preparing products such as noodles (guksu), dough flakes (ssujaebi), rice cakes (tteok), sweets (gwaja), candies/toffee (yeot) and other types. (8) “Seasonings” (SEA) includes spices, herbs and condiments (yangnyeom), and food deodorants.

Use-report determination

Every time a plant was mentioned as being used for a particular purpose, it was counted as one use-report. However, if an informant used a plant in more than one purpose/preparation under the same category, it was still considered as a single use-report (Amiguet et al. 2005; Ong and Kim 2014). A multiple use-report was considered when at least two informants mentioned the same plant for the same purpose.

Use value (UV)

Use value (UV), which is based on the number of uses and the number of people that cite a given plant (Phillips and Gentry 1993), was used to compute the relative importance of wild edible plants. UV is calculated using the following formula: \( {\text{UV}} = (\Sigma {\text{U}}_{i} )/{\text{N}} \), where Ui is the number of use-reports cited by each informant for a given species, and N is the total number of informants. UVs are high when there are many use-reports for a plant, implying that the plant is important, and low (approach to 0) when there are few use-reports. However, UV does not distinguish whether a plant is used for single or multiple purposes hence this study utilized another quantitative index below.

Fidelity level (FL)

Fidelity level (FL) is the ratio between the number of informants who mentioned the use of a plant for a particular purpose (herein termed as use-mention) and the total number of informants who mentioned the use of the plant for any purpose regardless the category (Friedman et al. 1986). FL is calculated using the following formula: \( {\text{FL}}\left( \% \right) = \left( {{\text{I}}_{\text{p}} /{\text{I}}_{\text{u}} } \right) \times 100 \), where Ip is the number of informants who independently suggested the use of a plant for a particular preparation, and Iu is the total number of informants who mentioned the plant for any purpose. High FL values (near 100 %) are obtained for a plant for which almost all use-mentions refer to the same purpose, that is the plant (and its use for a particular purpose) is most preferred, whereas low FLs are generally obtained for a plant that is used for many different purposes.

Results and discussion

Wild edible plants status and characteristics

This study was able to identify a total of 66 taxa in 36 families of wild edible plants gathered and consumed in Ulleung Island. Asteraceae and Rosaceae were the most represented families with 10 taxa for each. The preference for Asteraceae as vegetables may be due to their agreeable sensory properties, leading nowadays to the cultivation of many species of this plant family for human consumption (Guil-Guerrero et al. 1998). Rosaceae, on the other hand, have also been the most cited in studies in many temperate countries (Kalle and Sõukand 2012; Menendez-Baceta et al. 2012; Nedelcheva 2012), as it include many well known and beloved species of economic importance particularly edible temperate zone fruits (Janick 2005).

Among the total identified taxa, 35 were found to be included in the Korean wild edible plant classification by Lee (1969). Also, 10 taxa (see Table 1) were found to be endemic (Korea National Arboretum 2012a), and may become significant plant resources to the island if appropriate economic and biotechnological efforts are taken. Some plants (e.g. Anthriscus sylvestris, Sonchus oleraceus and Taraxacum platycarpum), on the other hand, had been introduced and have become naturalized (Korea National Arboretum 2012b), implying that their use as edibles in the island is somewhat recent if not indigenous. Most of the reported plants are herbs (45 %) and trees (31.8 %), followed by shrubs (12.1 %) and climbers (11 %). Table 1 presents the complete list of these plants with details about their cultural importance values (UV and FL) and modes of preparation.

Plant collection season and parts use preference

Most wild edibles and their parts are gathered and/or prepared in springtime (64 %), while other wild food plants, particularly fruits are collected in summer (23 %) and fall (12 %). Most leafy vegetables are reported to be collected in early spring, a common season for gathering wild plants in temperate regions (Leonti et al. 2006; Tardio et al. 2006; Hadjichambis et al. 2008). Many of these plants are collected in open fields while some are gathered from surrounding mountains. About 13 taxa (20 %), however, are considered weeds or invasive (Ryang et al. 2004) thriving in areas like roadsides and along walkways.

Most used plant parts are leaves (44 %) and young shoots (19 %) which may also be consumed without further preparation. Young plant parts (e.g. leaves and shoots) are preferred as vegetables for their more palatable taste and tender texture. Previous studies also showed similar results (Pieroni 1999; Ertug 2000; Bonet and Valles 2002). Fruits (16 %) are also a popular preference among the participants. Figure 2 shows the percentage of all plant parts used.

When taken for their culinary use, however, vegetables and fruits mentioned by each informant recorded an average of 4.66 and 1.0, respectively. The preference for greens is perhaps due to the more availability of these vegetative parts as compared to fruits which are usually gathered only during their maturity (when ripe) and seasonal availability. This result is relatively lower as compared to other studies conducted in East Asia, particularly China (Ghorbani et al. 2012; Kang et al. 2012, 2013) most probably due to the island’s lower plant biodiversity, smaller total land area but higher population density, as well as variations in climate and elevation.

As consumers, Koreans may possibly be recognized as “herbophilous”, the term described by Łuczaj (2008) as preference for using and consuming green parts of plants of numerous species. Our claim is based on the number of wild vegetables reported in previous related studies (Pemberton and Lee 1996; Lee et al. 2002; Song et al. 2013), and partly on the findings of this research. Although the “herbophily” and “fructophily” attitude of Korean people should be looked into in detail, general trends in food consumption (especially of cultivated produce) and nutrition transition in this industrialized country should also be examined. In the past few years, there has been a decline in the traditional habit of consuming vegetables (but increase in animal food consumption), while cultivated fruit consumption, on the contrary increased due to mass production and importation (Son 2003). According to the World Health Organization, an increase in vegetable and fruit consumption would decrease the burden of worldwide non-communicable disease (Lock et al. 2005). Such increase in consumption could decrease the cases of non-communicable illnesses such as cancer, diabetes and vascular diseases which are the primary factors that give rise to medical costs and decreased quality of life in Korea (Kim et al. 2013).

Informants

On the average, 6.01 wild edible plants were mentioned by each informant. Female informants mentioned relatively more wild food plants on average (6.46) as compared to males (5.56). This difference may be due to the women’s role as housekeepers who are almost always in charge with numerous food preparations in a patriarchal society like Korea. Women especially in rural areas have a significant role in the family, as well as in agriculture as farm managers. Around 10 % of Korean farms are managed by women according to Chung and Bang (1995). All informants also reported more frequent harvesting in the past (especially during times of crises) implying better economic status and relatively stable food security at present.

There were informants however, who mentioned that their last consumption of wild fruits and berries was when they were young. This implies that some plants were consumed for fun of eating and not as necessity especially when the informants were in their youth. Most of them, however, are old (although some are still active in farming or at least in home gardening), and belong to the Korean population who are considered elderly. Expertise of these aging repositories should be tapped in order to ensure more effective transmission of traditional knowledge to the younger generation before knowledge and their holders are lost by modernization and age.

Food categories and preparation

Category 5 “Cooked” (COO) was the most preferred method of preparation when taken as a whole (49 %), with subcategories 5b “Heat” (COOHe), 5a “Non-heat” (COONo) and 5c “Dry” (COODr) recording 25, 14 and 10 %, respectively. This implies that the use of wild edibles still plays a big role in the regular diet of the informants. Notable wild edible plant “cooking” methods are simple preparations characterized by blanching and parboiling. Korean culinary is known for its healthy way of cooking without or with little use of oil especially in preparing vegetable side dishes (banchan). Consuming fresh leafy vegetables as food wraps or as salad is also common in the regular diet. Drying to keep a supply of leafy vegetables was also commonly observed as evidenced by about 10 taxa whose leaves and/or shoots are sun or air dried for future consumption. This technique is basically practiced in preparation for winter (and for traditional festivals held in the season) when fresh vegetables are not normally available, or during times of food crisis.

One notable Korean method of food preservation and storage is by fermenting edible plants. Collectively, Category 4 “Fermented” (FER) showed 11.1 % of the total plant preparation, and comprises 4a “Lactic acid fermented” (FERLa), 4b “High salt fermented” (FERSa) and 4c “Vinegar fermented” (FERVi) foods recording 4.8, 4.8 and 1.4 %, respectively. In this study, a total of 8 taxa (see Table 1) are used in preparing Korean-style pickles called kimchi by lactic acid fermentation method. Korean-style fermentation is thought to have originated in the primitive pottery age from the natural fermentation of withered vegetables stored in seawater (Lee 2001). The fermentation process of vegetables can result in nutritious foods that may be stored for extended periods, 1 year or more, without refrigeration. Prior to fermentation, fresh fruits and vegetables may harbor a variety of microorganisms, as well as yeasts and molds (Nguyen-the and Carlin 1994). Hence in addition, fermentation to some degree assures safe consumption of food. In rural areas in Korea, especially in the past, kimchi is traditionally packed into earthen jars and buried in the soil to allow constant temperatures and to provide a supply of vegetables through the winter. In urban Korea today, however, kimchi is usually prepared commercially or by individuals using household programmable-temperature kimchi refrigerators (Breidt et al. 2007).

Category 1 “Fruits” (FRU) also showed relatively high percentage of preference (11 %). Fruit consumption in Korea increased four-folds per person from 1969 to 1998, which may be attributed to the expanded purchasing power of consumers and fruit price reduction due to importation (Son 2003). This seemingly increasing demand implies that if wild fruits growing in Ulleung Island are seen with commercial profitability, these fruits can be a potential source of income for farmers and growers.

Another noteworthy use of wild edibles is for the Korean tradition of commemorating deceased relatives and ancestors. Aster pseudoglehnii and Campanula takesimana (both island endemics), as well as Pteridium aquilinum var. latiusculum and Aruncus dioicus var. kamtschaticus were especially mentioned as plants served during Chuseok (Korean Thanks Giving) and Seollal (Lunar New Year) held in autumn and late winter, respectively. However, preparing for A. dioicus var. kamtschaticus as dish for such occasions, for example, starts from its collection in spring. The plant is locally called “samnamul” (literally ginseng vegetable) because of its similarity with the valued Korean medicinal plant. The young leaves and shoots of this native variety is dried (or initially blanched before drying) and kept for months for its use as soup ingredient or as a separate side dish in itself. To prepare as side dish, the parts are parboiled in water, and seasoned and mixed with condiments (chili, salt, pepper, sesame oil etc.) depending on taste. Regardless, its consistency and flavor is said to be that of meat, hence its inclusion as one of the significant dishes served during these two most important Korean holidays, especially in the past when economic capacity to buy meat was not favorable for Ulleung Island residents. These days, native wild vegetables are served together with an abundance of seafoods, meats and other cultivated fruits and greens.

Fidelity level

A total of 29 plant taxa (and their corresponding single preparation) recorded 100 % FL values. Most of these plants, however, were mentioned only by relatively few informants implying that these plants are probably consumed as famine food (especially in the past), and that these wild edibles may not be part of the islanders’ regular diet but are gathered only when normally consumed crops are not available. A plant with high FL and supported by a considerable number of use-mention implies that the particular plant (and its purpose/preparation) is most preferred. Notable plants with relatively high preference (FL %, use-mentions) are as follow: Vitis coignetiae (89.47 %, 17) which is eaten as fruit, A. sylvestris (86.67 %, 13) prepared by parboiling the shoots and Lilium hansonii (86.67 %, 13) by steaming the bulbs. L. hansonii, in particular, has a significant dietary role as carbohydrate substitute (famine food) or as complement especially when it is prepared together with staples such as rice, corn and barley.

Use value

The plants which recorded the highest UVs and number of use-report are A. ochotense (0.627, 52), A. pseudoglehnii (0.398, 33) and A. dioicus var. kamtschaticus (0.349, 29) indicating that these plants are considered the most culturally important by the informants. These edibles are commonly distributed in the island especially A. pseudoglehnii which is endemic to the island. A. ochotense, on the other hand, is closely related to the commonly cultivated garlic varieties and is more likely consumed for its similar properties or as substitute. Similarly, A. dioicus var. kamtschaticus plays an important cultural role as it is one of the most preferred plants used during memorial ceremonies. This plant has also been recently managed and partially cultivated in the island.

UV has also been associated with issues of conservation based on the idea that the most important species will suffer the greatest harvesting pressure (Albuquerque et al. 2006). Therefore, concerns about over collection of nine rare wild edible plants (see Table 1), especially of Cirsium nipponicum which has an endangered status, as well as Taxus cuspidata and L. hansonii both categorized as vulnerable (Lee 2009), should be taken into account.

Conservation and appreciation

In order to promote ecological conservation and gastronomic appreciation of the island’s wild edible plants and their traditional uses, Slow Food Foundation officially launched “Ulleung Island Sanchae” (Ulleung Island Mountain Vegetables) as one of its 4 presidia in Korea in early 2014 (Slow Food website 2015). This presidium specializes in quality production of spices, herbs and wild plant products that are at risk of extinction, as well as in the recovery of traditional processing methods and protection of local plant varieties of the island. Specifically, the goal is to promote dishes using wild edible herbs such as Allium senescens, L. hansonii and A. dioicus var. kamtschaticus in specialized local restaurants (also visit, http://www.slowfoodkorea.kr). Programs like this have also been launched in other areas in Korea (e.g. Jeju Island) by the foundation, and hopefully, more are to be organized by both private and local government organizations in the mainland provinces and surrounding islands.

Conclusion

This study was able to show that the tradition of gathering and consuming wild edible plants among the residents of Ulleung Island is still alive, and that the natural environment of the island can still provide considerable source of wild food plants, some which showing potentials for cultivation. It may also be concluded, however, that this once lively activity of wild food plant gathering is slowing and “aging”, and that the flavors of some of the wild edibles only exist in the informants’ collective memory. With the relative decline in the frequency of gathering, there is an urgent need to create means to revive and rediscover uses of these wild edible plants in order to preserve insular traditions and identity. These wild food plants can help promote the island as one of the top tourist and cultural destinations in Korea (e.g. when prepared in dishes by service sectors such as restaurants and hotels) as long as programs for the protection and conservation of vulnerable and threatened wild edible plant species are actively implemented. Finally, as informants who are repositories of this traditional knowledge become older and transmission of folk knowledge to the younger generations become more difficult, the more efforts to record and preserve traditional ecological knowledge should be pressed.

References

Albuquerque UP, Lucena RFP, Monteiro JM, Florentino ATN, Almeida CFCB (2006) Evaluating two quantitative ethnobotanical techniques. Ethnobot Res Appl 4:51–60

Amiguet VT, Arnason JT, Maquin P, Cal V, Vindas PS, Poveda L (2005) A consensus ethnobotany of the Q’eqchi’ Maya of southern Belize. Econ Bot 59:29–42

Baik MC, Hoang HD, Hammer K (1986) A checklist of the Korean cultivated plants. Kulturpflanze 34:69–144

Bonet MA, Valles J (2002) Use of non-crop food vascular plants in Montseny biosphere reserve (Catalonia, Iberian Peninsula). Int J Food Sci Nutr 53:225–248

Breidt F, McFeeters RF, Perez-Diaz I, Lee CH (2007) Fermented vegetables. In: Doyle MP, Buchanan RI (eds) Food microbiology: fundamentals and frontiers, 4th edn. ASM Press, Washington, pp 84–855

Chu KH (2008) A record of Dokdo observation. Woongjin Books, Seoul (in Korean)

Chung WK, Bang KH (1995) Women’s role in upland farming development in Korea. In: Van Santen CE, Bottema JWT, Stoltz DR (eds) Women in upland agriculture in Asia proceedings of a workshop (1995). CGPRT, pp 199–205. http://www.uncapsa.org/Publication/CG33.pdf

Chung JM, Kang UT, Park KW, Kim MS, Lee BC (2011) A checklist of the native vascular plants of Ulleung island. Korea, Korea National Arboretum, Gyeonggi-Do (in Korean)

Chung JM, Park KW, Jeong HR, Soo SK, Kim HJ, Choi K, Lee CH, Shin CH, Kim SS (2013) Ethnobotany in Korea—the traditional knowledge and use of indigenous plants. Korea National Arboretum, Gyeonggi-Do (in Korean)

Convention on Biological Diversity Korea (2014) The fifth national report to the Convention on Biological Diversity. Republic of Korea. http://www.cbd.int/doc/world/kr/kr-nr-05-en.pdf

Ertug F (2000) An ethnobotanical study in central Anatolia (Turkey). Econ Bot 54:155–182

Friedman J, Yaniv Z, Dafni A, Palewitch D (1986) A preliminary classification of the healing potential of medicinal plants, based on a rational analysis of an ethnopharmacological field survey among Bedouins in the Negev Desert, Israel. J Ethnopharmacol 16:275–287

Ghorbani A, Langenberger G, Sauerborn J (2012) A comparison of the wild food plant use knowledge of ethnic minorities in Naban River Watershed National Nature Reserve, Yunnan, SW China. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 8:17

Guil-Guerrero JL, Gimenez-Gimenez A, Rodrıguez-Garcia I, Torija-Isasa ME (1998) Nutritional composition of Sonchus species (S. asper L., S. oleraceus L. and S. tenerrimus L.). J Sci Food Agric 76:628–632

Hadjichambis AC, Paraskeva-Hadjichambi D, Della A, Giusti ME, De Pasquale C, Lenzarini C et al (2008) Wild and semi-domesticated food plant consumption in seven circum-Mediterranean areas. Int J Food Sci Nutr 59(5):383–414

Hammer K, Han UX, Hoang HD (1987) Additional notes to the checklist of Korean cultivated plants (1). Kulturpflanze 35:323–333

Hammer K, Ri JD, Hoang HD (1989) Additional notes to the checklist of Korean cultivated plants (3). Kulturpflanze 37:193–210

Hammer K, Ri JD, Hoang HD (1990) Additional notes to the checklist of Korean cultivated plants (4). Kulturpflanze 38:173–190

Hayashi Y, Kawamoto T (1942) Wild food plants of Choseon (Korea). Bulletin of the forest experiment station no. 33. The forest experiment station, government-general of chosen, Kiejo, Japan (present day Seoul, Republic of Korea) (in Japanese)

Heo YS, Lee BH (1999) Application of HACCP for hygiene control in university food service facility-focused on vegetable dishes (sengchae and namul). J Hyg Saf 14:293–304

Hoang HD, Hammer K (1988) Additional notes to the checklist of Korean cultivated plants (2). Kulturpflanze 36:291–313

Hoang H-D, Knüpffer H, Hammer K (1997) Additional notes to the checklist of Korean cultivated plants (5). Consolidated summary and indexes. Genet Resour Crop Evol 44:349–391

International Society of Ethnobiology (2006) ISE code of ethics (with 2008 additions). http://ethnobiology.net/code-of-ethics/

Janick J (2005) The origins of fruits, fruit growing, and fruit breeding. Plant Breed Rev 25:255–320

Kalle R, Sõukand R (2012) Historical ethnobotanical review of wild edible plants of Estonia (1770s–1960s). Acta Soc Bot Pol 81(4):271–281

Kang Y, Łuczaj Ł, Ye S, Zhang S, Kang J (2012) Wild food plants and wild edible fungi of Heihe valley (Qinling Mountains, Shaanxi, central China): herbophilia and indifference to fruits and mushrooms. Acta Soc Bot Pol 81(4):405–413

Kang Y, Łuczaj Ł, Kang J, Zhang S (2013) Wild food plants and wild edible fungi in two valleys of the Qinling Mountains (Shaanxi, central China). J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 9:26

Kim H (2010) Intergenerational transfers and old-age security in Korea. In: Ito T, Rose A (eds) The economic consequences of demographic change in east Asia, NBER-EASE (vol. 19). University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 227–278

Kim JE (2013) Land use management and cultural value of ecosystem services in Southwestern Korean islands. J Marine Isl Cult 2:49–55

Kim H, Song MJ (2013) Ethnobotanical analysis for traditional knowledge of wild edible plants in North Jeolla Province (Korea). Genet Resour Crop Evol 60(4):1571–1585

Kim H, Song MJ, Potter D (2006) Medicinal efficacy of plants utilized as temple food in traditional Korean Buddhism. J Ethnopharmacol 104:32–46

Kim EJ, Yoon SJ, Jo MW, Kim HJ (2013) Measuring the burden of chronic diseases in Korea in 2007. Public Health 127(9):806–813

Korea Forest Service (2010) Korean plant names index. http://www.nature.go.kr Accessed 06 Jan 2015

Korea National Arboretum (2012a) Ethnobotany and useful resource plants of Dokdo and Ulleung island in Korea. Korea National Arboretum, Gyeonggi-Do

Korea National Arboretum (2012b) Field guide: naturalized plants of Korea. Korea National Arboretum, Gyeonggi-Do

Lee TB (1969) Flora of edible wild plants in Korea. Forest Research Institute, Seoul (in Korean)

Lee TB (1979) Illustrated flora of Korea. Hyang Mun Sa, Seoul (in Korean)

Lee CH (2001) Fermentation technology in Korea. Korea University Press, Seoul

Lee TB (2006) Coloured flora of Korea. Hyang Mun Sa, Seoul (in Korean)

Lee YN (2007) New flora of Korea, vol I–II. Kyohak Publishing, South Korea (in Korean)

Lee BC (2009) Rare plants data book of Korea. Korea National Arboretum, Gyeonggi-Do

Lee MJ, Popkin BM, Kim S (2002) The unique aspects of the nutrition transition in South Korea: the retention of healthful elements in their traditional diet. Public Health Nutr 5:197–203

Leonti M, Nebel S, Rivera D, Heinrich M (2006) Wild gathered food plants in the European Mediterranean: a comparative analysis. Econ Bot 60:130–142

Lock K, Pomerleau J, Causer L, Altmann DR, McKee M (2005) The global burden of disease attributable to low consumption of fruit and vegetables: implications for the global strategy on diet. Bull World Health Organ 83(2):100–108

Łuczaj Ł (2008) Archival data on wild food plants used in Poland in 1948. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 4:4

Menendez-Baceta G, Aceituno-Mata L, Tardío J, Reyes-García V, Pardo-de-Santayana M (2012) Wild edible plants traditionally gathered in Gorbeialdea (Biscay, Basque Country). Genet Resour Crop Evol 59(7):1329–1347

Mills SRS, Park SH (2013) A mysterious island in the digital age: technology and musical life in Ulleungdo, South Korea. Ethnomusicol Forum 22:160–187. doi:10.1080/17411912.2012.713774

Ministry of Environment (2004) A research for designation of Ulleung marine national park. South Korea (in Korean)

Nedelcheva A (2012) An ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants in Bulgaria. EurAsian J BioSci 77:94

Nguyen-the C, Carlin F (1994) The microbiology of minimally processed fresh fruits and vegetables. Crit Rev Food Sci 34(4):371–401

Ong HG, Kim YD (2014) Quantitative ethnobotanical study of the medicinal plants used by the Ati Negrito indigenous group in Guimaras island, Philippines. J Ethnopharmacol 157:228–242. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2014.09.015i

Pemberton RW, Lee NS (1996) Wild food plants in South Korea; market presence, new crops, and exports to the United States. Econ Bot 50:57–70

Phillips O, Gentry AH (1993) The useful plants of Tambopata, Peru: I. statistical hypotheses tests with a new quantitative technique. Econ Bot 47:15–32

Pieroni A (1999) Gathered wild food plants in the upper valley of the Serchio river (Garfagnana), central Italy. Econ Bot 53:327–341

Ryang HS, Kim DS, Park SH (2004) Weeds of Korea—morphology, physiology, ecology. Rijeon Agricultural Resources Publications, South Korea (in Korean)

Slow Food website (2015) http://slowfoodfoundation.com/presidia/details/6245/ulleung-island-sanchae. Accessed 06 Jan 2015

Son SM (2003) Food consumption trends and nutrition transition in Korea. Malays J Nutr 9(1):7–17

Song M, Kim H, Brian H, Choi KH, Lee B (2013) Traditional knowledge of wild edible plants on Jeju island, Korea. Indian J Tradit Knowl 12:177–194

Steinkraus KH (1997) Classification of fermented foods: worldwide review of household fermentation techniques. Food Control 8:311–317

Tanaka T (1976) Tanaka’s cylopedia of edible plants of the world. Keigaku Publishing Company, Tokyo

Tardio J, Pardo-de-Santayana M, Morales R (2006) Ethnobotanical review of wild edible plants in Spain. Bot J Linn Soc 152:27–71

Turner NJ, Łuczaj ŁJ, Migliorini P, Pieroni A, Dreon AL, Sacchetti LE, Paoletti MG (2011) Edible and tended wild plants, traditional ecological knowledge and agroecology. Crit Rev Plant Sci 30(1–2):198–225. doi:10.1080/07352689.2011.554492

Yoo WC, Park HK, Kim KL (2000) Microbiological hazard analysis for prepared foods and raw materials of food service operations. Korean J Diet Cult 15:123–137

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the informants who shared their knowledge and personal experiences in order to complete this documentation of Ulleung Island wild edible plants. HGO wishes to thank KGSP/NIIED for the support. This research was made possible by Korea National Arboretum Research Fund (KNA1-1-11, 13-1).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ong, H.G., Chung, JM., Jeong, HR. et al. Ethnobotany of the wild edible plants gathered in Ulleung Island, South Korea. Genet Resour Crop Evol 63, 409–427 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-015-0257-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10722-015-0257-z