Abstract

This study investigated the moderating effect of gender on the causal relationships between different school play activities (pretend and non-pretend play) and social competence in peer interactions among a sample of Hong Kong children. Participants were 60 Hong Kong preschoolers (mean age = 5.44, 36.67 % female). Children with matched home pretend play time period were randomly assigned to pretend or non-pretend play groups to take part in pretend or non-pretend play activities respectively in the 1-month kindergarten play training. Children’s pre- and post-training social competences were assessed by their teachers. Results revealed a trend that girls who participated in school pretend play tended to be less disruptive during peer interactions after the training than those who participated in non-pretend play, while boys were similarly benefited from the two play activities. The implications for play-related research and children’s social competence development are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Social competence is an important skill that children need to acquire in the preschool years to integrate themselves successfully into social contexts. School play activities have been regarded as a means for social development (Pyle and Bigelow 2014). Researchers have conducted various studies to investigate the relationship between school pretend play and social competence. However, the results obtained were inconsistent with respect to whether a causal inference could be made (Lillard et al. 2013b) and further research has been called for to validate the effect of play-based learning approach on preschoolers’ social development (Pyle and Bigelow 2014). Most importantly, few studies have controlled the amount of pretend play that participants engage in outside the research context such as home pretend play, which is an important confounding variable that can lead to confusing research results (Kim 2011). In view of the research gap in the literature, the present research aimed to investigate the effect of school pretend play on social competence in peer interactions using an experimental design, with participants’ home pretend play time period being matched between the pretend and non-pretend play groups.

Pretend play, which is characterized by its ‘nonliteral’ and ‘as if’ nature (Garvey 1990; Vygotsky 1967), has been associated with many critical areas of development (e.g., Fein 1981; Galyer and Evans 2001). Social competence in peer interactions, which includes the ability to interact and cooperate effectively with peers, initiate and join in peer groups, be sensitive to others’ needs, and avoid aggressive, disruptive, or withdrawn behaviors (Bierman and Welsh 2000; Howes and Matheson 1992), is one of the critical areas of development (Bretherton 1989; Dennis and Stockall 2015).

Despite the prevailing theoretical support for the positive effect of pretend play on social competence, previous research has provided inconsistent results. Several studies have reported zero or negative associations between pretend play and social competence (e.g., Rubin 1982; Swindells and Stagnitti 2006). On the contrary, other studies reported a positive relationship between the constructs (e.g., Galyer and Evans 2001). In one study, 6-year olds who participated in drama training showed greater gains in social skills than those in music training or control group (Schellenberg 2004).

The results of existing research are inconsistent. Both positive and negative associations were found between pretend play and social competence. One plausible confounding variable would be the amount of pretend play participants joined in outside the research context. Kim (2011) suggested that the home environment can make similar or even stronger contributions to preschooler’s development. However, most studies did not control for home pretend play time period.

In addition to the amount of home pretend play, gender could possibly be another factor that led to the inconsistent research findings. Research evidence generally suggests that boys tend to apply more aggressive approach in resolving social struggles, whereas girls tend to apply more prosocial approaches (e.g., Underwood et al. 1999; Walker et al. 2002). Two studies have demonstrated gender differences in the relationship between pretend play and emotional competence in which the associations were stronger in girls than in boys (Lindsey and Colwell 2003, 2013), and the authors remarked that experimental study should be employed to provide more concrete evidence regarding the causal link between the constructs.

To resolve the inconsistencies in the literature and determine if there are any causal relationships between school pretend play and social competence, we conducted an experimental study using the non-equivalent control group with matching design. To interpret the effects of school pretend play independent of pretend play at home, the amount of home pretend play time period children engaged in before the training was matched between the pretend and non-pretend play groups. The independent variables were gender (boy vs. girl) and the type of play activities (pretend play vs. non-pretend play) that participants engaged in during kindergarten play sessions during the 1-month play training. Among different forms of pretend play, sociodramatic play with occupational theme (e.g., social enactment of a restaurant or a salon), which is a common form of play that children encounter in kindergarten, was adopted as the school pretend play activity in the present research. The dependent variable was the participants’ social competence in peer interactions after the training. It was expected that there would be a significant main effect of play on social competence. Specifically, after the play training, children engaging in school pretend play will exhibit higher social competence during play than children engaging in non-pretend play. It was also expected that there would be a significant interaction effect of play and gender on social competence. Specifically, the beneficial effects of school pretend play on social competence during play relative to non-pretend play was expected to be more prominent in girls than in boys.

Methods

Participants

The participants were 60 Hong Kong preschoolers (mean age = 5.44, 38 boys and 22 girls), and their parents, from K2 and K3 classes at a local full-day kindergarten that provides daily play sessions. Participants were from middle to lower-middle class families. Procedures employed in the study were approved by the Ethics Review Board of our institution. Written consent for the preschoolers to participate in the research was obtained from both school and parents, and they were reminded of their right to withdraw from the study at any time.

Procedure

Parents who agreed to their child’s participation returned the completed consent forms and questionnaire, which reported their child’s home pretend play time period. Children within each class were sequenced according to the parent-reported home pretend play time period, and pairs with comparable home pretend play time period were formed. Children within a pair were then randomly assigned to pretend or non-pretend play groups (with 19 boys and 11 girls each) so that the effect of home pretend play time period would be balanced. During the 1-month play training, children engaged in either pretend or non-pretend play. Children’s pre- and post-training social competence in peer interactions was assessed by teachers to examine the effect of different school play activities on social competence.

Play training was implemented during the preexisting play sessions. The teachers were unaware of the research hypotheses and were requested not to disclose information regarding participants’ grouping to their colleagues who were responsible for assessing participants’ social competence. To prevent an experimenter effect, the researcher did not take part in the implementation of play training. There was one play session on every school day, and there were 20 play sessions altogether during 1-month play training. Each play session lasted for approximately 45 min. All sessions were conducted in Cantonese.

School Play Activities

Before the start of the play training, the researcher conducted two meetings with all of the play training teachers. The first meeting aimed at introducing the procedure of the study, and all play training teachers were experienced in leading the play activities. Besides, teachers’ roles in implementing the play activities were briefed with details provided in the following paragraphs describing manipulation of pretend and non-pretend play. The second meeting focused on issues regarding occupational theme selection and play material preparation. Adjustments to the play activities and materials were also made according to teachers’ feedback on children’s interests, school curricula, or other constraints and difficulties.

After the meetings, ‘salon’ and ‘restaurant’ were selected as the occupational themes in the 1-month play training. Each theme covered 2 weeks. Participants in the pretend or non-pretend play groups took part in pretend or non-pretend play activities respectively. Following is an example of the manipulation of pretend play and non-pretend play, using the salon theme for illustration.

For the pretend play group, the play corner was decorated to simulate the settings of a salon, and participants were provided with relevant play materials including plastic hairdryer/combs/scissors, hair clips, hair decorations, mirrors, plastic bottles/cans, water spray bottle, hair curler, wigs with different colors, clothes, towels, hairstyle magazine, and cash register. During the 2 weeks, children in the group took turns to act out different characters in the salon including hair-stylists, hair-washers, and customers, and they were allowed to use the provided materials in ways that they decided were appropriate. Occupational pretend play was driven by the participants. The teacher initiated the start of each play session by facilitating children’s discussion on character assignment and distributing costumes related to the characters. During the play, teacher did not take part in the role playing but stayed outside the play corner for monitoring the play. Teachers intervened only when there was disciplinary problem, serious struggle, or the need to re-direct the attention of withdrawn children, to keep the play child-centered and natural. Most importantly, the pretend play involved the children in symbolic thought, object substitution and the projection of mental representations onto reality, which are essential components of pretend play (Lillard et al. 2013a).

For the non-pretend play group, another set of activities was prepared. During the 2 weeks, children carried out a series of non-pretend arts activities related to the occupational theme on tables outside the play corner. Children drew their hairstylist, painted their salon on paper boxes, and designed their hairstyle magazine and covering clothes for hair-cut. Teacher distributed required materials and explained the steps for completing the artwork at the start of each play session, and further guided individual child if needed. Teacher also re-directed the attention of withdrawn children during the play. Presentation time was hosted by teacher to allow the children to share their own work in order to balance the amount of adult-peer interaction across the pretend and non-pretend play groups. Table 1 presents the details of the manipulation of pretend play versus non-pretend play in the two occupational themes.

Assessment of Social Competence in Peer Interactions

A briefing session for explaining the use of the Peer Interactive Play Rating Scales (PIPRS; Lin and Lin 2006) was held separately for the teachers who were responsible for the assessment of children’s social competence. Two assistant teachers in the kindergarten who did not take part in the play training performed the assessment, and they were not informed of the hypotheses and grouping of the participants in order to minimize any expectancy effect. As each assessor rated the pre-training and post-training social competence of both the pretend and non-pretend play groups, any subjective rating could be balanced between the groups.

Before the play training, there was a 1-week ‘pre-training observation period’ for the assessing teachers to observe participants’ behavior in the daily play session and evaluate their social competence with the PIPRS (Lin and Lin 2006).

After the pre-assessment, the 1-month play training started. Experimental grouping (i.e., pretend play group vs. non-pretend play group) was implemented and the children had their daily play sessions in their own classroom according to their class schedule. During the play session, the pretend play group engaged in pretend play in the play corner, while the non-pretend play group carried out a non-pretend arts activity on tables outside the play corner. Each group was led by one teacher. The researcher paid regular visits to the kindergarten during the implementation stage of the play training to keep track of the progress of the training, collect feedback from the teachers (including children’s feelings about the play activities, observed level of engagement of the children and suggestions on additional pretend play materials), and resolved any problems related to the training. Based on the play training teachers’ feedback as well as researcher’s observation during the visits, participants in both conditions were generally enthusiastic players. For particular child who was not participating in the play, the teachers could effectively engage the child by re-directing his/her attention. Besides, the teachers were attentive to disciplinary problems and intervened in serious or unresolvable struggles among the children. On average, the play training teachers only needed to intervene in children’s play once or twice in a play session.

After the 1-month play training, children in both groups joined together for the daily play session according to their original class structure. The first week after the play training was the ‘post-training observation period’ for the assessing teachers to observe participants’ behaviors in the daily play session. In the second week, they evaluated participants’ post-training social competence with the same scales used before training. After finishing the post-training social competence assessment, the play activities of the two groups were swapped so that the overall learning experience of the two groups could be balanced.

Measures

Parent-Reported Home Pretend Play Time Period

The survey employed by Galyer and Evans (2001) for collecting parent-reported home pretend play frequency of kindergarteners was adapted. The original survey measured the frequency (i.e., how many days per week a child engaged in home pretend play) instead of the actual number of hours of home pretend play per week. To achieve the purpose of matching of participants, parents in the present study were required to report their child’s weekly average home pretend play time period. The question was written in Chinese and read: ‘In the last three months, my child, on average, engaged in XX hour(s) of home pretend play per week’. Definition of home pretend play written in Chinese was provided to parents and read: ‘Pretend play is defined as a kind of play that is nonliteral in nature which involves elaborate object substitutions (e.g., using something in circle shape as coins), transformations (e.g., treating a door handle as a water tap), and pretense actions (e.g., pretend to shop in an arcade at home); and could be carried out without the presence of actual materials or environment’.

Teacher-Reported Pre-/Post-training Social Competence in Peer Interactions

In response to the suggestion by Mathieson and Banerjee (2010) that peer play is an important context for assessing young children’s social competence, an instrument for measuring children’s social competence as demonstrated within the peer play context was employed in the current study. Teachers evaluated participants’ pre- and post-training social competences during play by using the Peer Interactive Play Rating Scales (PIPRS; Lin and Lin 2006). The PIPRS contains 43 items written in Chinese that assesses preschoolers’ social competence and it includes 3 dimensions: ‘Play Interaction’ (14 items), ‘Play Disruption’ (15 items), and ‘Play Disconnection’ (14 items). ‘Play Interaction’ refers to prosocial behaviors that facilitate and maintain peer play. Sample items include: ‘Child leads or facilitates other children during play’, ‘Child comforts and helps others during play’, and ‘Child likes to talk with others during play’. ‘Play Disruption’ refers to aggressive or disruptive behaviors children exhibit during peer play. Sample items include: ‘Child shows aggressive behavior during play’, ‘Child is not willing to take turns during play’, and ‘Child destroys others’ work during play’. ‘Play Disconnection’ refers to withdrawn or avoidant behaviors children display during peer play. Sample items include: ‘Child hovers/watches in a play group’, ‘Child wanders around with no purpose during play’, and ‘Child likes to be alone during play’. Assessors responded to each item on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Seldom) to 4 (Always). Participant’s score on a particular dimension was formed by averaging all relevant items under that dimension. For ‘Play Interaction’, a higher score represents higher social competence in peer interactions, whereas for ‘Play Disruption’ and ‘Play Disconnection’, a lower score reflects higher social competence in peer interactions. The scale has been found to have adequate reliability and validity (Lin and Lin 2006). For the current study, the internal consistency reliabilities were .925 (Play Interaction), .919 (Play Disruption), .892 (Play Disconnection) for the pre-training data and .885 (Play Interaction), .911 (Play Disruption), .879 (Play Disconnection) for the post-training data.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations between home pretend play time period and various social competence dimensions. Home pretend play time period was not significantly correlated with any social competence dimension (all rs < .15, all ps > .10). ‘Play Interaction’ and ‘Play Disconnection’ were negatively correlated in both pre-training (r = −.58, p < .001) and post-training (r = −.47, p < .001), indicating a negative association between the two dimensions. Each of the three dimensions in the pre-training was correlated with its corresponding dimension in the post-training (all rs > .76, all ps < .001).

Effect of Gender and School Play Activity on Social Competence in Peer Interactions

To compare people’s scores before and after treatment together with a control group, Wainer (1991) suggested that covariance adjustment should be adopted if natural change is expected to occur in the control group. As preschoolers learn and develop their social competence every day, it is assumed that the baseline rate of their social competence would change. Thus, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was employed (Wainer 1991) to analyze the pre- and post-training social competence of boys and girls under the pretend and non-pretend play groups. A series of Gender × School Play Activity ANCOVA was conducted on each dimension of post-training social competence, with the corresponding pre-training social competence as the covariate such that individual differences before the training could be controlled.

Play Disruption

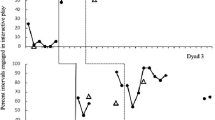

Figure 1 shows post-training ‘Play Disruption’ as a function of gender and school play activity with pre-training ‘Play Disruption’ as the covariate, with a lower score representing being less disruptive. Contrary to the first hypothesis, the main effect of school play activity was non-significant, F(1, 55) = .36, p = .55, η 2 p = .006. There was a marginally significant interaction effect between gender and school play activity, F(1, 55) = 2.80, p = .10, η 2 p = .048.

Post-hoc analysis was carried out to examine any significant difference in post-training ‘Play Disruption’ by conducting one-way ANCOVAs with pre-training ‘Play Disruption’ as the covariate. Results for girls revealed that school pretend play (M = 1.44, SD = .25, n = 11) had a marginally significant effect in reducing their peer play disruption when compared to non-pretend play (M = 1.57, SD = .32, n = 11), F (1, 19) = 2.91, p = .10, η 2 p = .133. However, boys in both pretend play (M = 1.66, SD = .53, n = 19) and non-pretend play (M = 1.63, SD = .45, n = 19) groups exhibited similar levels of peer play disruption after the training, F(1, 35) = .68, p = .41, η 2 p = .019. After controlling for the pre-training scores, the effect of school pretend play in reducing peer play disruption relative to non-pretend play was more prominent in girls than in boys, which concurs with the second hypothesis.

Play Interaction

Contrary to the two hypotheses, results from the Gender × School Play Activity ANCOVA revealed that the main effect of school play activity, F(1, 55) = .69, p = .41, η 2 p = .012, and the interaction effect between gender and school play activity, F(1, 55) = .79, p = .38, η 2 p = .014, were both non-significant. After controlling for the pre-training scores, children in the four groups showed similar level of post-training peer play interaction (boys in pretend play: M = 1.95, SD = .52, n = 19; boys in non-pretend play: M = 2.02, SD = .53, n = 19; girls in pretend play: M = 2.19, SD = .46, n = 11; and girls in non-pretend play: M = 2.42, SD = .52, n = 11).

Play Disconnection

Contrary to the two hypotheses, results from the Gender x School Play Activity ANCOVA revealed that the main effect of school play activity, F(1, 55) = .29, p = .59, η 2 p = .005, and the interaction effect between gender and school play activity, F(1, 55) = .82, p = .37, η 2 p = .015, were both non-significant. After controlling for the pre-training scores, children in the four groups showed similar levels of post-training peer play disconnection (boys in pretend play: M = 1.24, SD = .21, n = 19; boys in non-pretend play: M = 1.22, SD = .26, n = 19; girls in pretend play: M = 1.26, SD = .47, n = 11; and girls in non-pretend play: M = 1.12, SD = .13, n = 11).

Discussion

The primary purpose of this study was to examine the effect of school pretend play on preschoolers’ social competence in peer interactions using an experimental design, with participants’ home pretend play time period being matched between pretend and non-pretend play groups. The present research tentatively suggests gender as a potential moderator to the effects of pretend and non-pretend play on preschoolers’ social competence in the play context. It is important to note, however, that the Gender × School Play Activity interaction and the corresponding post hoc test on ‘Play Disruption’ were only marginally significant, probably due to the small sample size in each group and the limited variance explained by the experimental manipulation. Based on the results, there was a trend that girls who participated in school pretend play tended to be less disruptive after the training than those who participated in non-pretend play, but this pattern did not apply to boys. Boys demonstrated similar level of peer play disruption after joining either pretend or non-pretend play.

Based on our hypotheses, boys who joined in pretend play were expected to be less disruptive after the training than those who joined in non-pretend play, even though the beneficial effect of pretend play was expected to be less significant for boys than girls. However, the present results suggested that both play activities were similarly effective in reducing boys’ play disruption. By merely looking at the group means, boys in the non-pretend play group demonstrated even less play disruption (though non-significant) than those in the pretend play group after the training. Such trend resembles previous evidence suggesting that boys’ emotional competence was associated with frequency of physical play (i.e., exercise, rough-and-tumble), whereas girls’ emotional competence was associated with frequency of pretend play (Lindsey and Colwell 2003). This phenomenon might stem from the fact that boys in the pretend play group had to compete with others for the favored pretend play character or tools, or negotiate with others to guide the play direction, which could lead to increased struggle among the group; whereas boys in the non-pretend play group could carry out their arts activity and, at the same time, appreciate others’ work. Consequently, boys in the pretend play group might have gained negative experiences in resolving the additional conflicts incurred, which offset the positive effect that was brought by pretend play and resulting in the similar effects of the two play activities.

There may be other quantitative or qualitative differences in boys’ and girls’ pretend play that led to the diverging effects of the two play activities across gender. Regarding quantitative differences, various studies have shown that girls were more likely to engage in pretend play, which suggests that boys may find pretend play less attractive (e.g., Jones and Glenn 1991; Lindsey and Mize 2001). The relationship between pretend play and social competence could be bidirectional in nature. Boys’ relatively lower level of social problem-solving skills might lessen their motivation to engage in school pretend play, and thus reduce the beneficial effect of pretend play (Black 1989). Regarding qualitative differences, boys and girls may have different goals for pretense in which boys focus on asserting their play ideas, whereas girls enjoy the play interaction (Black 1989). Differences in goals for pretense might affect boys’ and girls’ play behavior and their social competence as perceived by adults. Further research is needed to uncover the reason of why boys tend to obtain similar benefits from pretend and non-pretend play activities.

The present study has several implications. Theoretically, the results contribute towards resolving the inconsistencies in the current literature (Lillard et al. 2013b) by suggesting gender as a potential moderator of the effect of different play activities. Practically, the results respond to the call for further research to examine the effect of play-based learning across different contexts such that educators could make a better balance between academic learning and play-based approaches (Pyle and Bigelow 2014). As demonstrated by the present results, different play activities are effective means to enhance children’s social competence development. In response to the plausible gender effect, teachers are suggested to pay special attention to balance the beneficial effects to boys and girls, and give necessary guidance to those who may use aggressive means in resolving social conflicts within pretend play.

A noteworthy advancement of the current study was the employment of an experimental design, which suggested the possible causal links between pretend play, non-pretend play, and social competence in peer interactions with certain confounding variables under control. The experiment was conducted in authentic kindergarten play sessions that preschoolers encountered every day, and pretend play was driven by the children without unnecessary constraints in order to achieve ecological validity. Also, the play training lasted for 1 month so that the effects of play could be built up.

Despite the above strengths of the current research, there are several limitations in this study. Firstly, the small number of participants reduced the statistical power of the analyses. Participants were recruited from a single kindergarten. Generalizability could be improved by replicating the study with several participating kindergartens. Secondly, social competence measure employed in the current study focused on participants’ behaviors during play, and thus the results obtained may not be generalized to other social contexts. Thirdly, although a clear definition of pretend play was provided in the questionnaire for the parents, differences in interpretation and memory error could be additional sources of error. Lastly, contamination may have occurred due to the close interaction between the teachers and the participants, even though the play training teachers were requested not to disclose participants’ grouping information to the assessing teachers.

In summary, social competence is an important skill that children need to acquire in the preschool years. Results from the current study suggest that the causal links of pretend and non-pretend play on preschoolers’ social competence in peer interactions might be moderated by gender. Girls tended to be less disruptive after participating in pretend play relative to non-pretend play, whereas boys similarly benefited from both play activities. Further research is needed to verify the present findings and examine the underlying mechanism which explains the moderating effect of gender.

References

Bierman, K. L., & Welsh, J. A. (2000). Assessing social dysfunction: The contributions of laboratory and performance-based measures. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 29(4), 526–539. doi:10.1207/S15374424JCCP2904_6.

Black, B. (1989). Interactive pretense: Social and symbolic skills in preschool play groups. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 35(4), 379–397.

Bretherton, I. (1989). Pretense: The form and function of make-believe play. Developmental Review, 9(4), 383–401. doi:10.1016/0273-2297(89)90036-1.

Dennis, L. R., & Stockall, N. (2015). Using play to build the social competence of young children with language delays: Practical guidelines for teachers. Early Childhood Education Journal, 43(1), 1–7. doi:10.1007/s10643-014-0638-5.

Fein, G. G. (1981). Pretend play in childhood: An integrative review. Child Development, 52, 1095–1118. doi:10.2307/1129497.

Galyer, K. T., & Evans, I. M. (2001). Pretend play and the development of emotion regulation in preschool children. Early Child Development and Care. doi:10.1080/0300443011660108.

Garvey, C. (1990). Play. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. (enlarged ed.).

Howes, C., & Matheson, C. C. (1992). Sequences in the development of competent play with peers: Social and social pretend play. Developmental Psychology, 28(5), 961–974. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.28.5.961.

Jones, A., & Glenn, S. M. (1991). Gender differences in pretend play in a primary school group. Early Child Development and Care, 72, 61–67. doi:10.1080/0300443910720105.

Kim, K. (2011). The creativity crisis: The decrease in creative thinking scores on the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking. Creativity Research Journal, 23(4), 285–295. doi:10.1080/10400419.2011.627805.

Lillard, A. S., Hopkins, E. J., Dore, R. A., Palmquist, C. M., Lerner, M. D., & Smith, E. D. (2013a). Concepts and theories, methods and reasons: Why do the children (pretend) play? Reply to Weisberg, Hirsh-Pasek, and Golinkoff (2013); Bergen (2013); and Walker and Gopnik (2013). Psychological Bulletin, 139(1), 49–52. doi:10.1037/a0030521.

Lillard, A. S., Lerner, M. D., Hopkins, E. J., Dore, R. A., Smith, E. D., & Palmquist, C. M. (2013b). The impact of pretend play on children’s development: A review of the evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 139(1), 1–34. doi:10.1037/a0029321.

Lin, S. H., & Lin, C. J. (2006). Development and validation of “Peer Interactive Play Rating Scales”. The Journal of Study in Child and Education, 2, 17-42. Retrieved February 28, 2014, from http://web.nutn.edu.tw/gac680/js/2-02.pdf.

Lindsey, E. W., & Colwell, M. J. (2003). Preschoolers’ emotional competence: Links to pretend and physical play. Child Study Journal, 33(1), 39–52.

Lindsey, E. W., & Colwell, M. J. (2013). Pretend and physical play: Links to preschoolers’ affective social competence. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 59(3), 330–360. doi:10.1353/mpq.2013.0015.

Lindsey, E. W., & Mize, J. (2001). Contextual differences in parent–child play: Implications for children’s gender role development. Sex Roles, 44(3–4), 155–176. doi:10.1023/A:1010950919451.

Mathieson, K., & Banerjee, R. (2010). Pre-school peer play: The beginnings of social competence. Educational and Child Psychology, 27(1), 9–20.

Pyle, A., & Bigelow, A. (2014). Play in kindergarten: An interview and observational study in three Canadian classrooms. Early Childhood Education Journal. doi:10.1007/s10643-014-0666-1.

Rubin, K. H. (1982). Nonsocial play in preschoolers: Necessarily evil? Child Development, 53(3), 651–657. doi:10.2307/1129376.

Schellenberg, E. (2004). Music lessons enhance IQ. Psychological Science, 15(8), 511–514. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00711.x.

Swindells, D., & Stagnitti, K. (2006). Pretend play and parents’ view of social competence: The construct validity of the Child-Initiated Pretend Play Assessment. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 53(4), 314–324. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1630.2006.00592.x.

Underwood, M. K., Hurley, J. C., Johanson, C. A., & Mosley, J. E. (1999). An experimental, observational investigation of children’s responses to peer provocation: Developmental and gender differences in middle childhood. Child Development, 70(6), 1428–1446. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00104.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1967). Play and its role in the mental development of the child. Soviet Psychology, 5, 6–18.

Wainer, H. (1991). Adjusting for differential base rates: Lord’s Paradox again. Psychological Bulletin, 109(1), 147–151. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.109.1.147.

Walker, S., Irving, K., & Berthelsen, D. (2002). Gender influences on preschool children’s social problem-solving strategies. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development, 163(2), 197–210. doi:10.1080/00221320209598677.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

The article is based on the first author’s Postgraduate Diploma in Psychology thesis, under the supervision of the second author, submitted to the Hong Kong Institute of Education.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fung, Wk., Cheng, R.Wy. Effect of School Pretend Play on Preschoolers’ Social Competence in Peer Interactions: Gender as a Potential Moderator. Early Childhood Educ J 45, 35–42 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-015-0760-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-015-0760-z