Summary

Purpose Our previous phase I trial suggested feasibility of addition of leucovorin (LV) to S-1 and gemcitabine therapy in advanced pancreatic cancer. The aim of this phase II trial was to assess the efficacy and toxicity of gemcitabine, S-1 and LV (GSL) combination therapy for advanced pancreatic cancer. Methods Chemotherapy-naïve patients with histologically or cytologically proven advanced pancreatic cancer were enrolled. Gemcitabine was administered at a dose of 1000 mg/m2 by 30 min infusion on days 1, S-1 40 mg/m2 orally twice daily and LV 25 mg orally twice daily on days 1 to 7 every 2 weeks. Primary end point was progression free survival (PFS). Results A total of 49 patients with advanced pancreatic cancer (19 locally advanced and 30 metastatic) were enrolled. Overall response rate and disease control rate were 32.7% and 87.8%. The median PFS and overall survival (OS) were 10.8 (95% confidence interval [CI], 7.4–13.5) and 20.7 (95% CI 13.0-NA) months with 1-year survival rate of 73.4%. Major Grade 3–4 toxicities were neutropenia (22.4%) and stomatitis (14.3%). No toxicity related death was observed. Conclusions In this single center, phase II trial, gemcitabine, S-1 and LV combination therapy was tolerable and can potentially be a treatment option for advanced pancreatic cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer (PC) is the fourth leading cause of cancer death in Japan. Although surgical resection is the only cure, only 20% of patients are surgical candidates and the overall 5-year survival rate is less than 5%. In patients with metastatic PC, the prognosis is quite poor with median overall survival (OS) less than 12 months despite the advancement of intensive chemotherapy.

Recently, FOLFIRINOX and nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone, showed significantly prolonged survival, [1, 2] at the cost of increased toxicity. In some clinical trials, a modified regimen of FOLFIRINOX showed improved safety profile while maintaining efficacy. [3, 4] In a first prospective study of modified FOLFIRINOX for metastatic pancreatic cancer in Asia, [5] overall adverse events were reduced but the rate of grade 3–4 neutropenia was still as high as 47.6%.

We previously reported a phase I trial of gemcitabine, S-1 and LV (GSL) therapy for advanced PC, which showed a good tumor response (response rate and disease control rate of 33% and 93%) with acceptable toxicity. [6] The median OS of 16.6 months in this study appeared also promising, though the number of cases was small. Therefore, we conducted this phase II trial for unresectable PC to further evaluate safety and efficacy of GSL.

Patients and methods

Eligibility

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) histologically or cytologically proven pancreatic adenocarcinoma; (2) locally advanced or metastatic disease; (3) no prior treatment for PC; (4) ECOG performance status of 0–2; (5) age ≥ 20 years; (6) adequate organ function, as indicated by white blood cell count ≥3000/mm3, absolute neutrophil count ≥1500/mm3, hemoglobin ≥9.0 g/dl, platelet count ≥100,000/mm3, total bilirubin ≤3 times the upper limit of normal (ULN), aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels ≤5 times ULN, serum creatinine level ≤ 1.5 times ULN; (7) expected life expectancy >2 months. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) severe comorbidities such as active infection, cardiac or renal disease, marked pleural effusion, or ascites; (2) active gastrointestinal bleeding; (3) active interstitial pneumonitis; (4) severe drug hypersensitivity; (5) active concomitant malignancy; and (6) pregnant or lactating women.

Study design and endpoints

This study was an open-label, single center, single-arm phase II study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of GSL therapy for unresectable pancreatic cancer. The primary endpoint was progressive free survival (PFS). Secondary endpoints were adverse events of GSL, tumor response and OS. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Tokyo Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. This study is registered at UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN000010678).

Treatment protocol

Patients were treated with intravenous gemcitabine 1000 mg/m2 over 30 min on day 1, and S-1 40 mg/m2 and LV 25 mg administered orally twice a day from days 1–7. Each cycle was repeated every 2 weeks. If grade 3 or higher hematological toxicity, serum aspartate aminotransferase or alanine aminotransferase ≥5 ULN, serum total bilirubin ≥3 ULN, or serum creatinine ≥3 ULN was observed, dose reduction by 10 mg/m2 of S-1 or 200 mg/m2 of gemcitabine was recommended. In cases of toxicities specifically attributable to S-1 i.e., stomatitis or diarrhea, the dose of S-1 was reduced. The dose of LV was fixed.

Response and toxicity assessment

Physical examination including blood pressure, complete blood count with differential, electrolyte levels with creatinine, and liver function tests were measured before study entry, on days 1, 8 and 15 of the first cycle and on day 1 of the subsequent cycles. Carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (CA19–9) was assessed on day 1 of every 2 cycles. Tumor response was assessed by CT scan every 2 cycles, using RECIST 1.1. [7] Toxicity was evaluated using NCI-CTCAE 4.0. [8]

Statistics

The primary measure of efficacy was PFS. The threshold PFS was 3.5 months, and the expected PFS was set at 5.5 months. If the PFS was 5.5 months, a sample size of 49 patients would ensure a power of at least 80% at a one-sided significance level of 2.5% and assume a 5% dropout rate attributable to ineligibility.

PFS and OS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. PFS was defined as time from the start of treatment to the date of either disease progression or death or censored at last follow-up. OS was defined as time from the time from chemotherapy to the final follow-up or until death from any cause. All statistical analysis was performed using the JMP ®11(SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

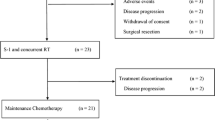

Of 49 patients enrolled between April 2013 and March 2017, all patients were eligible for the study protocol (Fig. 1). Patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. Tumor staging at diagnosis was locally advanced in 19 cases (36.7%) and metastatic in 30 cases. The sites of metastasis were liver (36.7%), lung (14.3%) and peritoneum (8.2%). The median primary tumor size was 43.0 mm and the primary tumor site was the head of pancreas in 55.1%. The median pretreatment CA19–9 was 494.0 IU/L.

Adverse events

The median number of cycles delivered was 16 (range, 1–80) cycles. Grade 3 and 4 adverse events developed in 11 cases (22.4%). Details of adverse events are shown in Table 2. The major grade 3 and 4 adverse events were neutropenia (22.4%) and stomatitis (14.3%). We introduced oral health care prior to GSL treatment in January 2014 and the rate of grade 3 and 4 stomatitis decreased from 21.7% to 7.7%. Febrile neutropenia occurred in 2 cases (4.1%). Dose reduction was necessary in 24 cases (49.0%) but adverse events were manageable after dose reduction in most cases. Treatment discontinuation of GSL therapy due to toxicity was in 4 cases (stomatitis in 2, anorexia in 1, interstitial pneumonia in 1), though. No toxicity-related death was observed.

Efficacy

Tumor response by RECIST criteria was partial response (PR) in 16 and stable disease (SD) in 27 cases. No radiological complete response (CR) was observed. As a result, the response rate was 32.7% and the disease control rate was 87.8%. The response rates in locally advanced and metastatic diseases were 26.3% and 36.7%, and disease control rates of locally advanced and metastatic diseases were 94.7% and 83.3%, respectively. During GSL therapy, the median shrinkage rate of primary tumor was 33.8% (range, −40.0-98.7%, Fig. 2a). The median shrinkage of primary tumor and metastatic site was 22.5% (range, −40.0-98.8%, Fig. 2b). Conversion surgery was performed in 2 out of 19 locally advanced cases. The reasons for treatment failure were disease progression in 31, unacceptable toxicities in 4, deteriorated general conditions in 6, consent withdrawn in 3 and others in 3.

The median PFS was 10.8 (95% confidential interval [CI], 7.4–13.5) months (Fig. 3). The median OS was 20.7 (95% CI, 13.0-NA) months (Fig. 4) with the 1-year survival rate of 73.4%. The median PFS of locally advanced and metastatic diseases was 12.7 (95% CI, 8.0–24.6) and 7.6 (95% CI, 5.6–11.0) months, and the median OS of locally advanced and metastatic diseases was 26.1 (95% CI, 18.3-NA) and 18.8 (95% CI, 10.0-NA) months, respectively.

CA19–9 and outcome

CA19–9 response at 8 weeks was evaluated in 33 cases whose CA19–9 level at baseline was beyond the upper limit of normal. Serum CA19–9 level decreased by ≥25% at 8 weeks in 21 cases (65.6%). The PFS was significantly longer in cases with CA19–9 response:11.0 (95%CI, 7.3–24.6) months vs. 7.4 (95%CI, 2.3–7.8) months in cases with and without CA19–9 response (p = 0.01). The median OS was also significantly longer in patients with CA19–9 response: 26.8 (95%CI, 12.2-NA) months vs. 12.8 (95%CI, 5.1–20.0) months in cases with and without CA19–9 response, (p = 0.03).

Second line therapy

A second line chemotherapy was administered in 28 cases. The second line regimens were as follows: nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine in 12, gemcitabine and S-1 in 6, FOLFIRINOX or modified FOLFIRINOX in 6, CPT-11 in 2, and others in 2. The median PFS of second line chemotherapy was 7.8 (95%CI, 5.4–9.9) months.

Discussion

Since addition of S-1 to gemcitabine in unresectable pancreatic cancer demonstrated a higher response rate and longer PFS, [9,10,11,12] further addition of LV can potentially enhance antitumor effects and prolong PFS and OS. The addition of LV to S-1 was first reported in colorectal cancer, [13] and was investigated in advanced pancreatic cancer and demonstrated promising efficacy for gemcitabine-refractory pancreatic cancer. [14] Our previous phase I trial of GSL confirmed a recommended dose of GSL in advanced pancreatic cancer. [6] and the present phase II trial of GSL demonstrated acceptable safety and favorable PFS (10.8 months) and OS (20.2 months) in advanced pancreatic cancer.

While intensive chemotherapy such as FOLFIRINOX and nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine are the standard chemotherapy in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer, the incidence of severe neutropenia and febrile neutropenia was higher than that in patients received gemcitabine alone. A modified regimen of FOLFIRINOX in metastatic pancreatic cancer was evaluated in a prospective multicenter study, which demonstrated a maintained efficacy and an improved safety. [5] Despite the improved safety of modified FOLFIRINOX, the incidence of grade 3–4 neutropenia was as high as 47.8%. On the other hand, the incidence of grade 3–4 neutropenia of GSL combination therapy were 22.4% and febrile neutropenia was observed in only 2 case (4.1%) in our study cohort. In addition to neutropenia, major severe toxicity of GSL was stomatitis. Stomatitis was representable toxicities of S-1 and the increased rate of stomatitis by the addition of LV to S-1 was previously reported, too. [13] It is suggested an oral health care can potentially reduce the risk of chemotherapy-induced oral stomatitis. [15] We introduced pretreatment oral health care by dentists, which effectively decreased stomatitis (21.7% to 7.7%). While peripheral neuropathy is one of the common adverse events of nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine [2] and FOLFIRINOX [1], it was not observed in our study cohort. In cases with severe peripheral neuropathy, a sequential use of nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine and FOLFIRINOX is not clinically acceptable due to the impaired quality of life. Given the different profile of adverse events, GSL can be a treatment option because it can be safely administered sequentially with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine or FOLFIRINOX. In our study cohort, those regimens were administered in 18 out of 28 cases who received second line treatment.

In Japan, gemcitabine and S-1 were two key drugs in the treatment of pancreatic cancer and had been widely used in clinical practice until the introduction of FOLFIRINOX or nab-paclitaxel. Three randomized control studies were conducted to evaluate gemcitabine and S-1 vs. gemcitabine alone including our study. [9,10,11] While PFS and OS of gemcitabine and S-1 combination were 5.4 and 13.5 months in GEMSAP study, PFS and OS of GSL therapy were 10.8 and 20.7 months, respectively, in this trial. In a pooled analysis of three randomized controlled trials, [12] gemcitabine and S-1 combination therapy was shown to prolong OS compared to gemcitabine alone in locally advanced pancreatic cancer: 16.41 vs. 11.83 months. Recently, the role of conversion surgery for locally advanced pancreatic cancer was explored [16] and neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) for borderline resectable pancreatic cancer has been increasingly utilized in clinical practice, too. [17, 18] We have conducted another phase II trial of GSL in cases with borderline resectable pancreatic cancer and reported promising results with R0 resection rate of 76.5%. [19] In this study cohort of 19 unresectable locally advanced pancreatic cancer, conversion surgery was performed in 2 cases. So far, there is no established regimen for borderline resectable or locally advanced pancreatic cancer as NAC and we believe GSL can be a treatment option.

The role of CA19–9 for predicting treatment outcomes in unresectable pancreatic cancer has been reported. [20,21,22] In our trial, the decrease of CA19–9 from baseline at 8 weeks was independently associated with PFS and OS and can be useful for early prediction of treatment efficacy.

There are some limitations in our study. First, this was a single center study without a control group. While our study results appeared comparable to or even better than those of FOLFIRINOX or nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine, the inter-study comparison is impossible. Second, a longer OS can be attributable to the effectiveness of second line chemotherapy. Both FOLFIRINOX and nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine were available as a treatment option after GSL failure and a median PFS of 7.8 months was relatively long in the settings of second line chemotherapy for advanced pancreatic cancer. Thus, our study results should be confirmed in a prospective randomized controlled trial.

In conclusion, GSL combination therapy for unresectable pancreatic cancer was feasible with acceptable toxicities. Given the long PFS of 10.8 months in our study, GSL combination therapy can be a candidate for promising cancer treatment in unresectable pancreatic cancer.

References

Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, Bouche O, Guimbaud R, Becouarn Y et al (2011) FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 364(19):1817–1825. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1011923

Von Hoff DD, Ervin T, Arena FP, Chiorean EG, Infante J, Moore M et al (2013) Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med 369(18):1691–1703. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1304369

Yoshida K, Iwashita T, Uemura S, Maruta A, Okuno M, Ando N et al (2017) A multicenter prospective phase II study of first-line modified FOLFIRINOX for unresectable advanced pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget 8(67):111346–111355. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.22795

Stein SM, James ES, Deng Y, Cong X, Kortmansky JS, Li J et al (2016) Final analysis of a phase II study of modified FOLFIRINOX in locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer 114(7):737–743. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2016.45

Ozaka M, Ishii H, Sato T, Ueno M, Ikeda M, Uesugi K et al (2018) A phase II study of modified FOLFIRINOX for chemotherapy-naive patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 81(6):1017–1023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-018-3577-9

Nakai Y, Isayama H, Saito K, Sasaki T, Takahara N, Hamada T et al (2014) A phase I trial of gemcitabine, S-1 and LV combination (GSL) therapy in advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 74(5):911–915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-014-2563-0

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R et al (2009) New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 45(2):228–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026

National Cancer Institute USDOHAHS (2009) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE), Version 4.0. https://www.eortc.be/services/doc/ctc/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_5x7.pdf. Accessed 1 Feb 2013

Nakai Y, Isayama H, Sasaki T, Sasahira N, Tsujino T, Toda N et al (2012) A multicentre randomised phase II trial of gemcitabine alone vs gemcitabine and S-1 combination therapy in advanced pancreatic cancer: GEMSAP study. Br J Cancer 106(12):1934–1939. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2012.183

Ozaka M, Matsumura Y, Ishii H, Omuro Y, Itoi T, Mouri H et al (2012) Randomized phase II study of gemcitabine and S-1 combination versus gemcitabine alone in the treatment of unresectable advanced pancreatic cancer (Japan clinical Cancer research organization PC-01 study). Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 69(5):1197–1204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00280-012-1822-1

Ueno H, Ioka T, Ikeda M, Ohkawa S, Yanagimoto H, Boku N et al (2013) Randomized phase III study of gemcitabine plus S-1, S-1 alone, or gemcitabine alone in patients with locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer in Japan and Taiwan: GEST study. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol 31(13):1640–1648. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.43.3680

Hamada C, Okusaka T, Ikari T, Isayama H, Furuse J, Ishii H et al (2017) Efficacy and safety of gemcitabine plus S-1 in pancreatic cancer: a pooled analysis of individual patient data. Br J Cancer 116(6):1544–1550. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.128

Koizumi W, Boku N, Yamaguchi K, Miyata Y, Sawaki A, Kato T et al (2010) Phase II study of S-1 plus leucovorin in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol 21(4):766–771. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdp371

Ueno M, Okusaka T, Omuro Y, Isayama H, Fukutomi A, Ikeda M et al (2015) A randomized phase II study of S-1 plus oral leucovorin versus S-1 monotherapy in patients with gemcitabine-refractory advanced pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol 27(3):502–508. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv603

Saito H, Watanabe Y, Sato K, Ikawa H, Yoshida Y, Katakura A et al (2014) Effects of professional oral health care on reducing the risk of chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis. Support Care Cancer 22(11):2935–2940. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-014-2282-4

Satoi S, Yamaue H, Kato K, Takahashi S, Hirono S, Takeda S et al (2013) Role of adjuvant surgery for patients with initially unresectable pancreatic cancer with a long-term favorable response to non-surgical anti-cancer treatments: results of a project study for pancreatic surgery by the Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 20(6):590–600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00534-013-0616-0

Katz MH, Pisters PW, Evans DB, Sun CC, Lee JE, Fleming JB et al (2008) Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: the importance of this emerging stage of disease. J Am Coll Surg 206(5):833–846; discussion 46-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.12.020

Rose JB, Rocha FG, Alseidi A, Biehl T, Moonka R, Ryan JA et al (2014) Extended neoadjuvant chemotherapy for borderline resectable pancreatic cancer demonstrates promising postoperative outcomes and survival. Ann Surg Oncol 21(5):1530–1537. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-014-3486-z

Saito K, Isayama H, Sakamoto Y, Nakai Y, Ishigaki K, Tanaka M et al (2018) A phase II trial of gemcitabine, S-1 and LV combination (GSL) neoadjuvant chemotherapy for patients with borderline resectable and locally advanced pancreatic cancer. Med Oncol 35(7):100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-018-1158-8

Chung KH, Ryu JK, Lee BS, Jang DK, Lee SH, Kim YT (2016) Early decrement of serum carbohydrate antigen 19-9 predicts favorable outcome in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 31(2):506–512. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.13075

Nakai Y, Kawabe T, Isayama H, Sasaki T, Yagioka H, Yashima Y et al (2008) CA 19-9 response as an early indicator of the effectiveness of gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Oncology 75(1–2):120–126. https://doi.org/10.1159/000155213

Chiorean EG, Von Hoff DD, Reni M, Arena FP, Infante JR, Bathini VG et al (2016) CA19-9 decrease at 8 weeks as a predictor of overall survival in a randomized phase III trial (MPACT) of weekly nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine vs gemcitabine alone in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. Ann Oncol 27(4):654–660. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw006

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Drs. Dai Akiyama, Kaoru Takagi, Takeo Watanabe, Ryouta Takahashi, Dai Mohri and Kenji Hirano for their patient management.

Funding

This research was supported by Japanese foundation for multidisciplinary treatment of cancer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Hiroyuki Isayama and Yousuke Nakai received research funding from Taiho Pharmaceutical Co. All remaining authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University of Tokyo Hospital.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Saito, K., Isayama, H., Nakai, Y. et al. A phase II trial of gemcitabine, S-1 and LV combination (GSL) therapy in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Invest New Drugs 37, 338–344 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10637-018-0691-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10637-018-0691-9