Abstract

Suicide is the leading cause of death among youth experiencing homelessness, and these youth report high rates of suicide attempts. Research suggests that the interpersonal factors of perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness are proximal causes of suicide, but little is known about factors associated with these risks. The current study examined the relationship of social network characteristics, perceived social network support, and interpersonal risks for suicide among a sample of 150 youth experiencing homelessness who reported severe suicide ideation. Findings indicate that characteristics of the social network, including engagement in crime and alcohol use, interrupted the potentially protective effects of high perceived social network support for interpersonal risk factors of suicide. Findings imply that increasing perceived social network support as a protection against suicide will not be uniformly successful, and consideration of the social network characteristics is necessary. Future work needs to continue to uncover the complexity of modifiable intervention targets to prevent future suicide attempts among this high-risk group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Suicide is the third leading cause of death among those between the ages of 10 and 24 years (Centers for Disease Control (CDC) 2013). The risk of suicide is especially high among youth experiencing homelessness and is the leading cause of death, with studies reporting that between 20 and 68% report a lifetime suicide attempt (Kidd 2006; Kidd and Carroll 2007; Rew et al. 2001; Rotheram-Borus and Milburn 2004; Yoder et al. 2010), compared to 7.8% in the general youth population (CDC 2012). Among those youth experiencing homelessness who have attempted suicide, an average of 6.2 attempts is reported. In addition, studies reporting lifetime suicidal ideation rates have ranged from 14 to 66% (Kingree et al. 2001; Merscham et al. 2009). More youth survive suicide attempts than die from those attempts, but a prior suicide attempt is one of the strongest predictors of completed suicide (Brown et al. 2000). While some research has identified factors that increase risk among youth experiencing homelessness, including childhood abuse, street victimization, substance use, and depression (Hadland et al. 2015; Yoder et al 2010), most of the extant research has focused on the psychosocial impact of suicidal ideation (Frederick et al. 2012). Little research has described characteristics of youth experiencing homelessness with current or recent suicidal ideation, including their social network connections. This information can be useful to develop a better understanding of these youth, and for targeting intervention efforts.

Social connections with family and friends have an impact on factors associated with suicidality. Perceived support from family is associated with decreased likelihood of suicide (Hirsch and Barton 2011). Nevertheless, youth from abusive families and youth experiencing homelessness are less likely to perceive support from their family members, and thus turn to friends and peers for emotional support (Bao et al. 2000). Contact with peers has been shown to have positive and negative effects on youth’s suicidal behavior. Peers on the streets may be a source of information, mentoring, and support, as well as victimization and/or coercion. Affiliation with pro-social peers predicts lower levels of psychological distress (Dang 2014) and depression (Bao et al. 2000). Relationships with deviant peers is a risk factor for depression and suicidal behavior (Rice et al. 2012; Yoder et al. 2003) as is social withdrawal (Kidd and Carroll 2007).

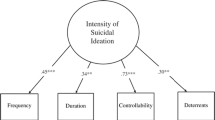

Theories of suicide have linked suicidal acts to perceptions of social relationships. For example, the Interpersonal Theory of Suicide includes two maladaptive cognitive states associated with a suicide attempt—low perceived belongingness and high perceived burdensomeness. Perceived burdensomeness is the belief that an individual “burdens family, friends, and/or society” and that the individual has more value deceased than living (Joiner et al. 2009, p. 634). Low belongingness is the perception that an individual is socially isolated from family members, friends, or other groups (Joiner et al. 2009). The current study examined how different aspects of youth’s social network interacted to influence thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness.

Compared to their non-homeless counterparts, the networks of youth experiencing homelessness are characterized with high rates of crime and substance use among family members and friends (Rice et al. 2012). This study examined how substance use and crime engagement in youths’ social networks moderated the association between their satisfaction with network support and thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness are considered proximal causes of the desire for suicide (Van Orden et al. 2010). While it was expected that higher satisfaction with social network connections would be associated with lower thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness, the role of network characteristics on this relationship is unknown among youth experiencing homelessness. By specifying the characteristics of social network connections among youth experiencing homelessness, a deeper understanding of how social relations impact factors associated with suicidal behaviors can be developed. All youth experiencing homelessness in the current study reported severe suicidal ideation within the last 90 days, and were engaged in a larger, ongoing suicide prevention study. As such, these youth were at significant risk of suicide, underscoring the importance of research clarifying risk for suicide among one of the highest-risk groups.

Method

Participants

Youth experiencing homelessness (N = 150) were recruited from the only homeless youth drop-in center in a large Midwestern city. In order to be eligible for the study, youth were currently homeless, between the ages of 18 to 24 years, did not require hospitalization, were able to provide informed consent as determined by Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 disorders (First et al. 2015) psychotic screening, and reported at least one episode of severe suicidal ideation in the past 90 days. Severe suicidal ideation was defined as scoring 16 or higher on the Scale for Suicidal ideation—Worst Point (SSI-W; Beck et al. 1999). Beck et al. (1999) reported that clients who scored 16 or higher on the SSI-W had 14 times higher chance to complete suicide. Table 1 presents a summary of demographic variables with regard to youth’s sex, race/ethnicity, childhood abuse history, homelessness, and substance use.

Measures

Demographic questionnaire was used to obtain participants’ age (Mean = 20.99, SD = 1.96), sex (coded as 0 = female, 1 = male), race/ethnicity (coded as 1 = African American, 2 = White, non-Hispanic, 3 = other race/ethnicities), and suicidal history (coded as 0 = no, 1 = yes). In the current sample, 121 youth reported a prior suicide attempt (80.7%).

Social network inventory (SNI) Youth were asked about people who are important in their life and with whom they had contact in the last 6 months. SNI has been used in several studies on homeless samples (e.g., Bates and Toro 1999; Toro et al. 1999). Specifically, SNI indices assess the total number of network members (including family and friends in the current study), frequency of contact with family and friend network members, and satisfaction with the help received from these members. Contact frequency with network supporters is measured on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (about once a year or less) to 5 (about daily). Similarly, the response scale for satisfaction with the help received from the network members ranges from 1 (feel worse) to 5 (feel very relieved). Additionally, SNI indices query alcohol/drug use and crime engagement of network members.

The interpersonal needs questionnaire (INQ; Van Orden et al. 2012) is a 25-item self-report scale designed to assess the two components of suicidal desire as conceptualized by the Interpersonal Psychological Theory of Suicide: thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness. The instrument has demonstrated high internal consistency with alpha coefficients ranging from 0.85 to 0.89 (Van Orden et al., 2008). The reliability for the scale was 0.87 in the current study.

The beck hopelessness scale (BHS; Beck and Steer, 1988) is a self-report instrument that consists of 20 true–false statements designed to assess the extent of positive and negative beliefs about the future during the past week. The BHS is one of the most widely used measures of hopelessness and has demonstrated high internal reliability across diverse clinical and nonclinical populations with Kuder-Richardson reliabilities ranging from 0.87 to 0.93 (Beck and Steer 1988). This variable is controlled. The reliability for the scale was 0.90 in the current study.

Overview of Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS24. Descriptive statistics, t-tests, correlations, and chi-square tests were used to examine characteristics of youth’s support network and the relationship between the quality of the support network and prior suicide attempts. Multiple regression analyses were performed to test our hypothesis that higher satisfaction with social network connections would be associated with lower thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness (our primary outcome variables), including the potential moderating effects of crime engagement, alcohol and drug use of youth’s support network. A post-hoc power analysis using G*Power program (version 3.1.0; Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, and Lang 2009) indicated that the models were sufficiently powered (1−β = 0.80) to detect a medium (e.g., f 2 = 0.15) to large-sized (e.g., f 2 = 0.35) interaction effect (Cohen, 1988).

Results

Characteristics of Social Network Connections

A small number of youth (17 out of 150, 11.3%) reported no contact with family members and 6 out of 150 (4%) reported no contact with friends in the last six months. On average, youth reported having contact with 2.96 family members (SD = 2.14) and 2.86 friends (SD = 2.06) in the prior 6 months. A high prevalence of alcohol/drug use were observed in both the family and friend network. Among those having contact with family members, 97 out of 133 (72.9%) reported that family members used alcohol (compared to 55.3% of general population reporting past month alcohol use (NIAAA, 2020)), and 77 out of 133 (57.9%) reported that family members used illicit drugs. Among youths’ friends, 110 out of 144 (76.4%) reported that their friends used alcohol, and 122 out of 144 (84.7%) reportedly used drugs. Additionally, a high prevalence of crime was reported among the family and friend networks; 34 out of 133 (25.6%) reported that family members had committed multiple crimes, and 40 out of 144 (27.8%) had friends who had committed multiple crimes.

Table 2 presents the prevalence of family and friend’s alcohol/drug use and crime engagement across sex and ethnicity/race. Friends’ drug use varied across sex (χ2 = 5.16 p < 0.05). Males (90.5%) were more likely to have friends using drugs compared to females (76.7%). Friends’ alcohol or family members’ alcohol/drug use did not vary across sex. As for family crime, females (34.6%) were more likely to have family members committing multiple crimes compared to males (19.8%) (χ2 = 3.68, p = 0.055). Family crime also varied across ethnic/racial groups (χ2 = 6.93, p < 0.05). Compared to African Americans (27.1%) and non-Hispanic Whites (15.1%), youth from non-White or African American backgrounds, including a combination of those self-identified as Asians, Hispanics, American Indians, and multiracial background (40.6%) were more likely to have family members engaging in crime. Moreover, family and friend’s alcohol/drug use varied across age. Those who reported that their family members used alcohol were younger (t (131) = 2.27, p < 0.05), while those who reported that their friends used illicit drugs were older (t (142) = -2.29, p < 0.05).

Contact frequency and satisfaction with the help received from the family and friend networks did not differ across sex, race/ethnicity, or age. The relationship between satisfaction with support network and family/friends alcohol/drug use was examined. The results showed that alcohol and drug use among family/friend network members was negatively associated with youth’s satisfaction with the help received from the network members. Specifically, youth with family members not using alcohol reported significantly greater satisfaction with the help received from the family compared to those with family members using alcohol (t = 3.40, p < 0.01). Similarly, youth with family members not using drugs reported significantly greater satisfaction compared to those with family members using drugs (t = 2.44, p < 0.01). As for friend networks, youth with friends not using drugs reported significantly greater satisfaction with the help received from friends compared to those with friends using drugs (t = 2.23, p < 0.05).

Chi-square analysis was performed to examine the association between family network contact in the last 6 months and prior suicide attempts. Results showed that having prior suicide attempts varied among those with family contact versus no family contact (X2 = 5.87, p < 0.05). Individuals having family contact (N = 133) were more likely to report prior suicide attempts (83.5%) compared to those without family contact (58.8%) (N = 17).

Social Network Connections, Thwarted Belongingness, and Perceived Burdensomeness

Multiple regression analyses were applied with thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness as the outcome variables. Sex, race, and hopelessness were controlled. Sex and race/ethnicity are demographic characteristics that are usually examined in association with suicidal behaviors (Van Orden et al. 2010). Hopelessness is prevalent among youth experiencing homelessness and associated with suicidal ideation (Cleverley and Kidd 2011), therefore, was controlled in the analyses too. Crime engagement, alcohol use, and drug use of support network members were included in the model as moderators. Table 3 presents the means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations of the study variables. Only significant interaction terms were retained in the model for the sake of parsimony. Table 4 presents the results of interaction effects.

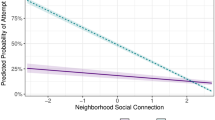

Friend Networks

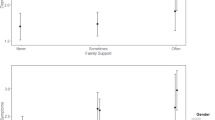

The overall model revealed a good fit (R2 = 0.310, R2adj = 0.264, F (9,134) = 6.69, p < 0.001). Friend’s crime engagement moderated the association between satisfaction with support from friends and thwarted belongingness (B = 0.41, SE = 0.20, β = 0.62, p < 0.05). Figure 1 depicts the significant moderation effects of friend’s crime engagement. Higher levels of satisfaction with friend’s support was significantly associated with lower levels of thwarted belongingness (B = − 0.36, SE = 0.13, β =− 0.28, p < 0.01) only when no crime engagement was reported among friends. The association between satisfaction and thwarted belongingness was not significant when crime engagement was reported. Friend’s alcohol and drug use did not show significant moderation effects. Similar moderation effects were not detected with perceived burdensomeness as the outcome variable.

Family Networks

The overall model revealed a good fit (R2 = 0.465, R2adj = 0.424, F (9,115) = 11.13, p < 0.001). Family alcohol use moderated the association between satisfaction with family support and perceived burdensomeness (B = 0.52, SE = 0.20, β = 0.87, p < 0.05). Figure 2 depicts the significant moderation effects of family alcohol use. Higher levels of satisfaction with family support were significantly associated with lower levels of perceived burdensomeness (B = -0.54, SE = 0.18, β =—0.55, p < 0.01) only when no alcohol use was reported among family networks. The association between satisfaction and perceived burdensomeness was not significant when alcohol use was reported. Family crime engagement and drug use did not show significant moderation effects. These moderation effects were not detected with thwarted belongingness as the outcome variable.

Discussion

In the current sample, 80% of youth reported a prior suicide attempt, indicating a very high-risk sample of youth. Most youth were able to identify family and friend social network members, with only a small number reporting no contact with family (11%) or friends (4%). These networks reported high rates of alcohol and drug use, with 73% of family members and 85% of friends. Approximately one-quarter of family and friends engaged in repeated criminal behavior. The less alcohol/drug use among social network members, the more satisfied youth were with the help received from the network member. Given that alcohol and drug use are often correlated with strained interpersonal relationships (Wilson et al. 2018), this finding is not unexpected.

Of interest is that youth reporting more family contact in the prior 6 months were also more likely to report a prior suicide attempt. As all youth in the current study were considered at risk for a future suicide attempt given high rates of current suicide ideation, it is possible that the families of these youth are a particular risk factor for suicide. Stressors associated with family members have been documented and include high rates of childhood physical and/or sexual abuse as well as parental substance use (Marshall et al. 2013). Longitudinal research is needed to confirm the temporal connection between family contact and suicide attempts. That is, future research may determine that suicidal youth with a history of suicide attempts seek more contact with family members in attempts to gain support. Continued efforts to receive psychosocial comfort from family members that results in perceived thwarted belonging and perceived burdensomeness could trigger future suicide attempts.

In understanding the relationship between satisfaction with family and friend networks and risk for suicide, as measured by perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness, alcohol use and crime engagement complicated the relationship. That is, high levels of satisfaction of family and friend support networks are often associated with low levels of thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness among “normative” populations (Jahn and Cukrowicz 2011; You et al. 2011). However, the unique characteristics of support networks of youth experiencing homelessness, including high rates of crime engagement and alcohol use, appear to interrupt this association. That is, in general, satisfaction with family and peer social networks was observed to be associated with perceived burdensomeness and thwarted belongingness with the caveat that among friend networks engaged in crime, high satisfaction was not related to increased sense of belongingness. Further, among family networks that use alcohol, high satisfaction was not related to reduced perceived burdensomeness. In other words, satisfaction with the social network did not consistently protect youth from factors known to increase risk for suicide, and characteristics of the social network moderated the relationship.

Some limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings. The primary limitation is the use of a cross-sectional design. As the larger study examined intervention effects, the relationship between satisfaction with social networks and suicide could only be examined at baseline, otherwise, the relationship would be confounded by treatment. However, we cannot conclude that satisfaction with the social networks will lead to reduced suicide attempts without tracking youth longitudinally over time. Further, the sample in this study included youth engaged only if they reported current suicidal ideation. The relationship between social network characteristics, satisfaction and perceived burdensomeness and belongingness might differ among youth who are not homeless and who do not currently report suicidal ideation. The study excluded youth with current psychotic symptoms due to concerns of youths’ ability to provide informed consent to procedures and of exacerbating risk for harm. However, these youth are also at risk for suicide and future research needs to identify intervention strategies tailored to these youths’ unique needs.

In conclusion, this study is one of the few studies to examine social network factors among a high-risk group of youth, known to increase risk for suicide attempts. By identifying modifiable factors associated with risk, interventions can be more effective at preventing future suicide attempts among those with current suicide ideation. Prior studies have recommended increasing satisfaction with social support networks as a focus of suicide prevention interventions (Conwell 2001; Katz et al. 2013; Miller et al. 2009). This study observed an interruption between the expected relationship between higher satisfaction with social networks and lower risk for suicide. This finding implies that interventions which simply focus on increasing satisfaction with social networks as a protection against suicide might not be effective for youth experiencing homelessness and with social networks involved with criminal activity and/or substance use. Rather, these characteristics of the social network need to be considered, and potentially addressed by intervention efforts. For example, identifying new social support networks might need to be a focus of intervention when seeking to reduce the potential for a suicide attempt. Alternatively, reducing family member’s alcohol use and peer’s engagement in crime could increase the protective effects of the social network supports.

References

Bao, W., Whitbeck, L. B., & Hoyt, D. R. (2000). Abuse, support, and depression among homeless and runaway adolescents. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41(4), 408–420.

Bates, D. S., & Toro, P. A. (1999). Developing measures to assess social support among homeless and poor people. Journal of Community Psychology, 27(2), 137–156.

Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1988). Beck hopelessness scale. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation.

Beck, A. T., Brown, G. K., Steer, R. A., Dahlsgaard, K. K., & Grisham, J. R. (1999). Suicide ideation at its worst point: A predictor of eventual suicide in psychiatric outpatients. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 29(1), 1–9.

Brown, G. K., Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Grisham, J. R. (2000). Risk factors for suicide in psychiatric outpatients: a 20-year prospective study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(3), 371.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2012). Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States 2011 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Surveillance Summaries, 61(4), 10–12.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2013). Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS). Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html.

Cleverley, K., & Kidd, S. A. (2011). Resilience and suicidality among homeless youth. Journal of Adolescence, 34(5), 1049–1054.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Conwell, Y. (2001). Suicide in later life: A review and recommendations for prevention. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 31(Supplement to Issue 1), 32–47.

Dang, M. T. (2014). Social connectedness and self-esteem: Predictors of resilience in mental health among maltreated homeless youth. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 35(3), 212–219.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149–1160.

First, M. B., Williams, J. B. W., Karg, R. S., & Spitzer, R. L. (2015). User’s guide for the structured clinical interview for DSM-5 disorders: Research version. Arlington, VA: American Psychological Association.

Frederick, T. J., Kirst, M., & Erickson, P. G. (2012). Suicide attempts and suicidal ideation among street-involved youth in Toronto. Advances in Mental Health, 11(1), 8–17.

Hadland, S. E., Wood, E., Dong, H., Marshall, B. D. L., Kerr, T., Montaner, J. S., et al. (2015). Suicide attempts and childhood maltreatment among street youth: A prospective cohort study. Pediatrics, 136(3), 440–449.

Hirsch, J. K., & Barton, A. L. (2011). Positive social support, negative social exchanges, and suicidal behavior in college students. Journal of American College Health, 59(5), 393–398.

Jahn, D. R., & Cukrowicz, K. C. (2011). The impact of the nature of relationships on perceived burdensomeness and suicide ideation in a community sample of older adults. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 41(6), 635–649.

Joiner, T. E., Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Selby, E. A., Ribeiro, J. D., Lewis, R., et al. (2009). Main predictions of the interpersonal–psychological theory of suicidal behavior: Empirical tests in two samples of young adults. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 118(3), 634–646.

Katz, C., Bolton, S., Katz, L. Y., Isaak, C., Tilston-Jones, T., Sareen, J., et al. (2013). A systematic review of school-based suicide prevention programs. Depression and Anxiety, 30, 1030–1045.

Kidd, S. A. (2006). Factors precipitating suicidality among homeless youth: A quantitative follow-up. Youth & Society, 37(4), 393–422.

Kidd, S. A., & Carroll, M. R. (2007). Coping and suicidality among homeless youth. Journal of Adolescence, 30(2), 283–296.

Kingree, J. B., Braithwaite, R., & Woodring, T. (2001). Psychosocial and behavioral problems in relation to recent experience as a runaway among adolescent detainees. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 28(2), 190–205.

Marshall, B. D. L., Galea, S., Wood, E., & Kerr, T. (2013). Longitudinal associations between types of childhood trauma and suicidal behavior among substance users: A cohort study. American Journal of Public Health, 103(9), e69–e75.

Merscham, C., Van Leeuwen, J. M., & McGuire, M. (2009). Mental health and substance abuse indicators among homeless youth in Denver. Colorado. Child Welfare, 88(2), 93–110.

Miller, D. N., Eckert, T. L., & Mazza, J. J. (2009). Suicide prevention programs in the schools: A review and public health perspective. School Psychology Review, 38(2), 168–188.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) (2020). Alcohol facts and statistics. Retrieved from https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/alcohol-facts-and-statistics.

Rew, L., Taylor-Seehafer, M., & Fitzgerald, M. L. (2001). Sexual abuse, alcohol and other drug use, and suicidal behaviors in homeless adolescents. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 24(4), 225–240.

Rice, E., Kurzban, S., & Ray, D. (2012). Homeless but connected: The role of heterogeneous social ties and social network technology in the mental health outcomes of street-living adolescents. Community Mental Health Journal, 48(6), 692–698.

Rotheram-Borus, J., & Milburn, N. (2004). Project I: Pathways into homelessness. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Community Health.

Toro, P. A., Goldstein, M. S., Rowland, L. L., Bellavia, C. W., Wolfe, S. M., Thomas, D. M., et al. (1999). Severe mental illness among homeless adults and its association with longitudinal outcomes. Behavior Therapy, 30, 431–452.

Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Cukrowicz, K. C., Braithwaite, S. R., Selby, E. A., & Joiner, T. E. (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological review, 117(2), 575–600.

Van Orden, K. A., Cukrowicz, K. C., Witte, T. K., & Joiner, T. E., Jr. (2012). Thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness: Construct validity and psychometric properties of the Interpersonal Needs Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 24(1), 197–215.

Wilson, S. R., Lubman, D. I., Rodda, S., Manning, V., & Yap, M. B. H. (2018). The impact of problematic substance use on partners’ interpersonal relationships: Qualitative analysis of counselling transcripts from a national online service. Drugs: Education, Prevention, and Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687637.2018.1472217.

Yoder, K. A., Whitbeck, L. B., & Hoyt, D. R. (2003). Gang involvement and membership among homeless and runaway youth. Youth & Society, 34(4), 441–467.

Yoder, K. A., Whitbeck, L. B., & Hoyt, D. R. (2010). Comparing subgroups of suicidal homeless adolescents: Multiple attempters, single attempters, and ideators. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 5(2), 151–162.

You, S., Van Orden, K. A., & Conner, K. R. (2011). Social connections and suicidal thoughts and behavior. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25(1), 180–184.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIDA Grant No. R34DA037845 to the first author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. The authors certify responsibility for the for the conduct of the study and the analysis and interpretation of the data, helped write the manuscript and agree with the decisions about it, meet the definition of an author as stated by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors, and have seen and approved the final manuscript.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Slesnick, N., Zhang, J. & Walsh, L. Youth Experiencing Homelessness with Suicidal Ideation: Understanding Risk Associated with Peer and Family Social Networks. Community Ment Health J 57, 128–135 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00622-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00622-7