Abstract

Studies have shown that foster care alumni have disproportionally high rates of poor mental health outcomes compared to the general population. The purpose of this study was to examine differences in mental health service use for Latino, African American, and White youth while in foster care and upon exit from the foster care system. Secondary data were used to identify youth 1 year prior to exiting the foster care system (N = 934) and 1 year after exit from the foster care system (N = 433). Racial/ethnic disparities in mental health service use upon exit from the foster care system were found, with Latino youth using the least amount of services after foster care exit. Racial/ethnic service disparities in type of services used were also found. Findings suggest that a lack of support (e.g., mandatory or voluntary) may be significant in overcoming challenges in the continuation or disruption of services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Youth Aging Out of the Foster Care System

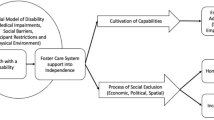

Each year, approximately 29,500 foster youth age out (i.e., they achieve the legal age of majority) of the foster care system (DHHS, 2012) with the expectation they will be self-sufficient. However, studies have shown that foster youth aging out of the foster care system are ill prepared to meet the demands of self-sufficiency and are at extreme risk for homelessness, unemployment, poverty, criminal involvement, early childbearing, and low educational attainment (Goerge et al., 2002; Dworsky, 2005; Courtney et al., 2007; Pecora et al., 2006). Consequently, foster youth alumni have been found to have experienced homelessness and be on public assistance at a higher rate than youth of the same age in the general population (Pecora et al., 2006; Brandford & English, 2004). Additionally, studies have also shown that youth aging out of foster care are less likely to have completed high school (Burley & Halpen, 2001). As a result, educational attainment has important implications for racial/ethnic minority youth as African American foster care alumni have been found to be less likely to have earned a high school diploma (Dworsky et al., 2010), and earn wages below the poverty level than their White counterparts (Naccarato et al., 2010) who have income three times above the poverty level (Harris et al., 2009). African American foster care alumni have also been found to be on public assistance and less likely to have avoided teenage parenthood (Dworsky et al., 2010).

Although it is unknown to what degree poor outcomes are associated with mental health need, studies suggest a possible link between poor outcomes in the transition to adulthood and a psychiatric diagnosis. Lenz-Rashid (2006) conducted a study of homeless transitional youth with and without a history of foster care. While results indicate that youth without mental health issues were more likely to find employment and earn higher wages than youth with a mental health problem, youth with a history of foster care and mental health problems fared worse in that they were less likely to find employment and earn far less than youth with no foster care history and mental health problems. Naccarato et al. (2010) also found in the Midwest Evaluation of the Adult Functioning of Former Foster Youth study that youth with a history of PTSD and/or certain affective disorders, earned significantly less than youth without these disorders.

Mental Health Need

Poor mental health outcomes among foster care children and youth are well documented (Auslander et al., 2002; Staudt, 2003; McMillen et al., 2005). For instance, prevalence of mental health need with children in foster care is estimated as high as 80% (dosReis et al., 2001; Halfon et al., 1995; Landsverk & Garland, 1999), and prevalence of psychiatric disorders among older youth in care is estimated to be between 25 and 37% (Auslander et al., 2002; Heflinger et al., 2000; McMillen et al., 2005). Although estimates of mental health need among older youth in care appear to be much lower than that of children, upon closer evaluation, the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in the past year and lifetime prevalence for older youth in foster care may be underestimated. For example, when examining at least one psychiatric disorder during the youth’s lifetime, McMillen et al. (2005) found that 61% of participants aged 17 year who were in the custody of the Missouri Division of Family Services fit the criteria, and 62% reported having the onset of the psychiatric disorder prior to entering the foster care system.

Studies have also shown that foster care alumni have disproportionally high rates of poor mental health outcomes compared to the general population. In a study conducted by Pecora et al. (2003) of 1087 foster care alumni and 3547 adults from the general population, researchers found that 54.4% of foster care alumni reported having a current mental health problem compared to only 22.1% of the general population. Rates of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were also significantly higher (25.2%) than the general population (4%), and major depression was also higher for foster care alumni than the general population with 20% and 10%, respectively.

Despite the fact that studies have clearly documented the need for mental health services among children and youth in the child welfare system, the extent of racial/ethnic disparities in the need for mental health services is less clear. In the general population, studies of children and youth have found that racial/ethnic minority children and youth are at an increased risk for certain mental health disorders such as suicidal behavior for Latino, Asian-American, and American Indian children when compared to their White counterparts (Joe & Marcus, 2003), and Latino youth more likely to be diagnosed with adjustment, anxiety, and psychotic disorders (Yeh et al., 2002) than White youth. However, few studies have specifically examined racial/ethnic disparities in mental health need with children and youth in the child welfare system, and the findings are mixed. In a study conducted of older youth in foster care, Garcia and Courtney (2011) found that White adolescents were more likely to be diagnosed with a mental health disorder than African American youth. Other studies with racial/ethnic minority children and youth in foster care have found no significant differences (Ayon & Marcenko, 2008; Burns et al., 2004; Shin, 2005). Similarly, findings with racial/ethnic minority foster care alumni are also mixed. For example, Harris, Jackson, O’Brien, and Pecora (2010) found that White foster care alumni had a greater degree of social phobia than African American foster care alumni, and Jackson, O’Brien, and Pecora (2011) found that White foster care alumni had a higher prevalence of ADHD when compared to African American foster care alumni. Other studies have found no significant racial/ethnic differences in mental health outcomes with foster care alumni (Villegas & Pecora, 2012). However, because studies examining mental health need with racial/ethnic minority children and youth and foster care alumni are scarce in the research literature, generalizing findings is problematic, warranting further research in the area.

Mental Health Service Use During and After Foster Care

To better understand mental health service use, seminal studies in the field of mental health services research with children and youth in the foster care system focused on predictive variables of mental health service use which generally included demographic and case characteristics. Older age, male gender, and Caucasian children were found to be more likely to receive mental health services (Burns et al., 2004; Leslie et al., 2004; James et al., 2004; Zima et al., 2000). Additionally, children who experienced sexual abuse were most notably referred for services (Burns et al., 2004), while children who experienced physical abuse were only referred when externalizing behaviors were displayed (Garland et al., 1996), and children who experienced neglect were the least likely to utilize services (Leslie et al., 2000, 2004; Garland et al., 2000). Placement instability, or number of foster care placements, were also found to be significant in the utilization of mental health services (Rubin et al., 2004).

Research studies have shown that children in the child welfare system have a higher rate of receipt of mental health services than children in the general population (Leslie et al., 2004; McMillen et al., 2004). For example, studies have found that children in the foster care system use mental health services at a rate 10–20 times higher than children in the general population (Harman et al., 2000). However, documented receipt of mental health services does not guarantee adequate service provision. In a national study conducted by Raghavan, Inoue, Ettner, Hamilton, and Landsverk (2010), researchers found that only one-third of children with clinically significant Child Behavior Check List (CBCL) scores, while in the child welfare system, received care that met one national standard (i.e., screening, assessment, and referral) of mental health care.

Racial/ethnic disparities have also been clearly documented in the receipt of mental health services as studies have shown that African American and Latino foster care children are less likely to utilize mental health services than their White counterparts (Burns et al., 2004; Leslie et al., 2004; James et al., 2004; Zima et al., 2000; Garland et al., 2000; Garland & Besinger, 1997), and that Latino foster care children are the least likely to utilize mental health services (Leslie et al., 2000; Garland et al., 2000). For example, in several studies conducted in San Diego County of children in foster care, findings indicate that Latino children had significantly lower rates of mental health service use than their White counterparts (Leslie et al., 2000; Garland et al., 2000; James et al., 2004).

When examining receipt of mental health services with older youth in care, studies have found a significant decrease (60%) in the utilization of mental health services after youth leave foster care (McMillen & Raghavan, 2009). Few studies, however, have examined racial/ethnic disparities in the receipt of mental health services among foster care alumni, and studies have only examined differences between African American and White foster care alumni (Ringeisen et al., 2009). Improved understanding of racial/ethnic disparities in mental health service use by foster care alumni is impeded by the fact that almost all research studies examining racial/ethnic disparities with foster care alumni have focused primarily on mental health outcomes and not on utilization of services (Garcia et al., 2012; Villegas & Pecora, 2012; Jackson et al., 2011; Harris et al., 2010), thus resulting in a significant research gap.

Additionally, studies examining receipt of type of mental health services used for foster care alumni are scarce. This is an important area to consider as studies in the general population have found that African America youth are less likely to utilize outpatient services, school based services, or residential/inpatient services than their White counterparts (Barksdale et al., 2010). Garland et al. (2005) also found that among high risk youth, White youth had the highest use of any mental health service, while Asian American youth had the lowest use, and African American youth had the lowest service use of informal services (i.e., self-help group, peer counseling, counseling from clergy, and alternative healer). Among foster care youth, McMillen et al. (2004) found that African American foster care youth were less likely to receive outpatient therapy, psychotherapeutic medications, and inpatient services, but were more likely to receive residential services.

Few studies have examined the receipt of mental health services after foster care exit among foster care alumni as the emphasis has generally been on mental health outcomes (Garcia et al., 2012; Villegas & Pecora, 2012; Jackson et al., 2011; Harris et al., 2010), and fewer studies have addressed the use of mental health services while in foster care and upon exit from foster care among foster care youth (Ringeisen et al., 2009). This is an important issue as studies have found that mental health disorders are chronic conditions that persist into adulthood (Munson et al., 2011). The lack of continued mental health services among foster care alumni can only exacerbate the already poor mental health outcomes experienced by this population. Moreover, studies addressing use of mental health services while in foster care and upon exit from foster care with racial/ethnic minority youth have only examined utilization of services with African American and White youth (Ringeisen et al., 2009), while neglecting to examine other racial/ethnic groups. This lack of attention is problematic considering that racial/ethnic minority youth are overrepresented in the foster care system (DHHS, 2012; Hill, 2008).

The purpose of this study, therefore, is twofold: First, the current study sought to expand on the existing knowledge on mental health services receipt among racial/ethnic minority foster youth while in the foster care system and once they exit the foster care system. Second, the current study examined the different types of mental health services used by each racial/ethnic group during foster care and after exit from foster care. More specifically, the current study sought to answer the following research questions: (1) Are there racial/ethnic differences in mental health service use while in foster care and upon exit from the foster care system?; (2) What variables predict mental health service use while in foster care and upon exit from the foster care system? and (3) What type of services are being used, and are there any racial/ethnic differences in the type of services used?

Method

Few studies have examined the utilization of mental health services among African American, Latino, and White youth while in foster care and upon exit from the foster care system or the types of mental health services being used. Therefore, the research design of this study was an exploratory retrospective research design using administrative data from a large, ethnically diverse child welfare agency in the Southwest. Since the child welfare agency does not provide direct mental health services to the youth, mental health service data were obtained from the public mental health system in that the public mental health system collects the data and makes it available to the child welfare agency for its use. However, due to confidentiality and HIPAA regulations, no mental health diagnosis is provided to the child welfare system in the data. It’s important to note, however, that each participant in the study identified as having used mental health services was a client of the mental health system, thus having met criteria for a mental health diagnosis. It is also important to note that only African American and Latino youth are included in the study as racial/ethnic minority youth due to the small sample size of other racial/ethnic groups in the sample.

Sample and Data

A cohort of 17-year-old and older youth who were in the foster care system on January 31, 2009 (N = 2645) was identified. Age was an important factor as youth 17 years or older were nearing the age of emancipation, and therefore, would be exiting the foster care system in the near future. The date selected was also important as it allowed for a period of time to allow youth to emancipate or age out and collect mental health data while in foster care and after exit from foster care. Of the youth identified, 934 youth had mental health service use documented from the public mental health system 1 year prior to exiting the foster care system. The majority of youth were African American (42.9%), followed by Latino (40.9%) and White (16.2%). Gender was slightly different with males at 45.1% and females at 54.9%. The majority of youth identified were 17-years-old (59%) followed by 18-years-old (28.7%) and the rest 19 and 20-years-old at 9.9% and 2.5%, respectively. Reasons for entering the child welfare system (i.e., allegation type) were predominantly due to general neglect (45.8%), followed by at “risk, sibling abused” (i.e., a sibling had been identified as being abused and the risk of the current child being abused was high) (20.1%), physical abuse (13.5%), sexual abuse (11.3%), and emotional abuse (5.9%).

Variables

Predictive variables of mental health service use that have previously been found in the research literature to be correlated with use of mental health services were included. These variables fall into two categories, demographic and case variables:

Demographic variables: (1) ethnicity (categorical)—African American, Latino, and White. No other racial/ethnic group was included due to the small sample size of the groups; (2) Language (binary)—English and Spanish as the majority of youth identified as speaking either English (79%) or Spanish (21%); (3) Gender (binary)—male and female; (4) Age (categorical)—17, 18, 19 and 20-years-old; (5) Allegation type (categorical) (i.e., reason for entering the child welfare system)—general neglect, physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, and “at risk, sibling abused”.

Case variables: (1) Case closure reason (categorical)—court ordered, emancipation and other; and (2) Number of placements (continuous) (see Table 1).

Mental health variables: Mental health service use was identified if youth had used any type of mental health services and included in billing claims by the public mental health system—this variable was examined two ways, as a continues variable counting number of billing claims identified and binary (either used services or did not use services): (1) Mental health service use 1 year prior to case closure (i.e., 365 days before the case was closed) while in foster care (N = 934); (2) Mental health service use 1 year after exit from the foster care system (i.e., 365 days from case closure) (N = 433); and (3) Type of mental health service used (categorical)—individual therapy, group therapy, psychotropic medication, and other therapeutic services.

Data Analysis

Mental health service use variables were categorized as binary variables (i.e., yes/no) and entered into the models as outcome variables in the analysis. Chi-squares were used to identify racial/ethnic differences in mental health service use, while in foster care and post foster care. A two-step logistic regression analysis was used to identify predictive variables of mental health service use while in foster care and post foster care. Demographic (except for race/ethnicity) and case variables were entered in the first step of the model, followed by race/ethnicity to control for predictive variables. A series of logistic regressions were also used to identify any racial/ethnic differences in type of mental health services used. Odds ratios (ORs) were computed for each of the variables in the logistic regression models.

Results

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for mental health services use while in foster care and after foster care exit. A 54% drop in service use was evidenced for youth who were identified as having used mental health services while in foster care after foster care exit. Latino youth used slightly less mental health services (33.9%) than African American (35%) and White (39.9%) youth while in foster care. Upon exit from the foster care system, Latino youth used the least amount of mental health services (41%), with no differences between African American (50%) and White youth (50%).

When examining treatment intensity, the average number of times youth were seen within 1 year prior to case closure was 31.69 (SD 51.63) and 37.26 (SD 51.06), 1 year after exiting the foster care system. In addition, there was almost no variation when comparing average number of times youth were seen while in foster care among White and Latino youth, with White youth averaging 34.06 (SD 60.54) and Latino youth 35.25 (SD 58.46). African American youth were lower with 27.43 (SD 39.47). Upon exit from the foster care system, among those who received services, the average number of times seen was similar among White youth 38.04 (SD 50.81), Latino youth 37.80 (SD 57.59) and African American youth 36.54 (SD 45.78) (Table not shown).

Bivariate analysis revealed racial/ethnic differences when examining mental health service use while in foster care, [X 2(2, N = 2645) = 6.49, p < .039], and after foster care exit, [X 2(2, N = 934) = 8.69, p < .013]. White youth (n = 151, 36%) were more likely to use mental health services, followed by African American youth (n = 402, 30%), and Latino youth (n = 382, 29%) while in foster care. After foster care exit, there were no differences between White youth (n = 76, 50%) and African American youth (n = 202, 50%), but Latino youth were the least likely to use mental health services (n = 155, 41%) (Table not shown).

A two-step logistic regression model was used to examine racial/ethnic differences in the utilization of mental health services while in the foster care system. Predictive variables (i.e., demographic and case variables) of service use were entered in the first step of the model, followed by race/ethnicity in the second step. Age was statistically significant with 18 years-old two times more likely to use mental health services (OR 2.67, p < .001) and 19 years-old more likely to use mental health services (OR 1.79, p < .042) than 17 years-old. Case closure reason was also statistically significant with youth whose case was closed due to emancipating from the foster care system the least likely to use mental health services (OR 0.020, p < .001), and youth whose case was closed due to other reasons (i.e., family stabilized, relative placement, adoption, etc.) were four times more likely to use mental health services (OR 4.95, p < .001) than youth whose case was closed by court mandate (i.e., received services through other agencies, runaway, etc.). However, no statistically significant differences were found with race/ethnicity (see Table 3).

Table 3 also presents findings for a two-step logistic regression in examining predictive variables of mental health service use upon foster care exit. Predictive variables of mental health service use were entered in the first step, followed by race/ethnicity in the second step. Only reason for entering the foster care system (i.e., allegation type) was statistically significant from the predictor variables, with youth who entered the foster care system due to allegations of sexual abuse (OR 1.95, p < .003) and physical abuse (OR 1.49, p < .049) more likely to use mental health services than youth who entered the foster care system due to allegations of general neglect. Racial/ethnic differences were also found after controlling for predictive variables, with Latino youth the least likely to use mental health services after foster care exit (OR 0.676, p < .047) when compared to their White counterparts.

Type of mental health services consisted of youth utilizing individual behavioral therapy, group therapy, psychotropic medication, and other therapeutic services (i.e., crisis intervention, residential services, and day rehabilitation). Services were reported from the various public mental health agencies providing services to youth. Anytime a youth was seen within the year prior to case closure and a year after case closure it was entered as a service provided. A total of 30,413 contact hours were reported while youth were in the foster care system, and a total of 14,922 contact hours were reported after youth exited the foster care system. Table 4 displays the various contacts made by each racial/ethnic group while in the foster care system and after exit from the foster care system.

A series of logistic regressions were conducted to determine whether there were any racial/ethnic disparities in the type of mental health services used while in foster care and upon exit from the foster care system (see Table 5). While in foster care, Latino youth were least likely to use individual and group therapy (OR 0.783, p < .001 and OR 0.868, p > .001, respectively), least likely to use psychotropic medication (OR 0.692, p < .001), and almost three times more likely to use other therapeutic services (OR 2.84, p < .001) than their White counterparts. African American youth were more likely to use group therapy (OR 1.09, p < .007), and least likely to use psychotropic medication (OR 0.737, p < .001) than White youth.

After foster care exit, Latino youth were more likely to use individual therapy (OR 1.13, p < .016), least likely to use group therapy (OR 0.637, p < .001), more likely to use psychotropic medication (OR 1.34, p < .001), and three times more likely to use other therapeutic services (OR 3.19, p < .001) than White youth. While African American youth were the least likely to use individual therapy (OR 0.837, p < .001), but three times more likely to use other therapeutic services (OR 3.08, p < .001) than their White counterparts.

Discussion and Implications

The purpose of this study was to determine whether there were racial/ethnic disparities in mental health service utilization for older youth while in foster care and upon exit from the foster care system, and in the type of mental health services used. This study adds to the literature on mental health utilization by racial/ethnic minority foster care alumni as few studies have examined mental health service use after youth leave the foster care system, and even fewer studies have examined racial/ethnic differences in the type of mental health services used among this population of youth.

Ethnicity was not a significant predictor of mental health service use while youth were in foster care. This contradicts previous research studies that have found racial/ethnic disparities in mental health service use while youth are in care (Garland et al., 2000; James et al., 2004; Leslie et al., 2000). Several reasons may account for these findings; the majority of youth in the current study were either Latino or African American. The same is true for the total population of children and youth in the child welfare agency used. Having a densely, diverse population has often been associated with a greater use of mental health services by racial/ethnic minority clients when compared to Whites (Siegel et al., 2013). Also, youth are generally court ordered into services as part of their case plan while in the foster care system, having social workers and others assist in the access to and utilization of mental health services to comply with court mandates can significantly impact the utilization of services. For example, in a qualitative study conducted by Munson et al. (2011) of foster care alumni, researchers found that some participants indicated the reason for discontinuing mental health services was due to adults or facilitators in the youth’s life no longer “forcing” or “making” them attend services.

However, age and the reason for case closure were associated with mental health service use while youth were in foster care. Age has been previously found to be associated with mental health service utilization while youth are in foster care, with older youth more likely to be either referred to services or more likely to use services than their younger counterparts (Burns et al., 2004; James et al., 2004; Leslie et al., 2004; Villagrana, 2010). A reason for this can be attributed to the fact that older youth may display more externalizing behavior problems and are more likely to be deemed in need of mental health services (Shore et al., 2002; Timmer et al., 2004; Zima et al., 2000). The fact that youth who emancipated from foster care were the least likely to use mental health services, and youth whose case was closed due to reasons such as reunification, placed with relatives, adoption, and permanency finalized were four times more likely to utilize mental health services is not surprising. Youth who are unable to reunify with their families or are unable to obtain permanency in their living situations may have no motivation to seek services as other more pressing issues may be at play. For example, it is well documented that foster youth who age out of the foster care system or emancipate from the system lack appropriate contextual support and fare worse in securing housing and employment (Courtney et al., 2007; Dworsky, 2005; Fowler et al., 2009) than young adults without a foster care history. Comparatively, youth whose case was closed due to reasons such as reunification, placed with relatives, adoption, and permanency finalized have the support system in place to seek mental health services.

Racial/ethnic disparities were found in the utilization of mental health services once youth left foster care. While it is difficult to ascertain the reasons for this finding as few studies have examined racial/ethnic disparities in service utilization among foster care alumni (Ringeisen et al., 2009), the fact that youth are no longer supervised by a social worker might play a significant role. Studies have found that when the decision to discontinue or terminate mental health services was left to the youth, the youth discontinued services due to a lack of perceived need (McMillen & Raghavan, 2009; Munson et al., 2011). Racial/ethnic differences may also exist due to cultural factors. For example, findings from this study indicate that Latino youth were the least likely to utilize services after exiting the foster care system, and studies in the general population have consistently found an association between the underutilization of mental health services and the stigma of having a mental illness among Latinos, as those persons who seek mental health services are perceived as severely disturbed (Cabassa & Zayas, 2007; Interian et al., 2007). Latinos also often rely on family and friends for emotional support and those with strong social networks are less likely to seek formal mental health services (Hansen & Aranda, 2012; Snowden, 2007; Villatoro et al., 2014). Having a successful permanency plan or reunifying with family upon exit from the foster care system may explain the study’s findings. Additionally, youth who experienced physical and sexual abuse were also more likely to use mental health services upon exit from the foster care system; a finding consistent with previous research studies (Burns et al., 2004; Garland et al., 1996), however, results need to be interpreted with caution due to the small sample size.

One intriguing finding from this study when examining the type of mental health services used while in foster care is the fact that African American and Latino youth were the least likely to have used psychotropic medication when compared to their White counterparts. This contradicts previous research studies that have found prescription and use of psychotropic medications highest among foster care youth with variations between 13 and 40% among studies (Leslie et al., 2010, 2003; McMillen et al., 2004; Raghavan et al., 2005, 2010) compared to only 6.7% of youth in the general population (Zito et al., 2008). However, when examining racial/ethnic disparities in psychotropic medication use, findings are consistent with previous research studies that found African American and Latino youth less likely to be receiving psychotropic medications when compared to White youth (Leslie et al., 2003; McMillen & Raghavan, 2009; McMillen et al., 2004; Ringeisen et al., 2009). Several explanations have been given in the literature for the discrepant rates in psychotropic medication use. In a study conducted by McMillen and Raghavan (2009), youth gave several reasons for stopping psychotropic medication while in foster care and upon foster care exit, the main reasons were that the youth felt they didn’t like being on the medication or felt they didn’t need to be on medication. Leslie et al. (2003) also postulated several reasons for racial/ethnic disparities in psychotropic medication use that ranged from genetics playing a significant role in both efficacy and side effects profiles to cultural factors in acceptance of and adherence to treatment.

Another intriguing finding is the significant increase in the use of group therapy by all racial/ethnic groups after foster care exit. The use of groups has been found to be a significant method to attract youth in discussing their emotional well-being. For example, Munson and Lox (2012) conducted a study with foster care alumni who had mental health histories and asked their preference in the types of services they would be most likely to attend in managing their mood and emotional difficulties. The majority of youth endorsed group type activities with support groups being the highest ranked, followed by peer support group and a panel discussion on living with moods. Although logistic regression results show Latino youth the least likely to have used group therapy than their White counterparts after foster care exit in the present study, these findings are impacted by the fact that Latino youths’ use of all mental health services significantly decreased after exit from the foster care system.

Further, Latino youth were also more likely to use individual therapy and psychotropic medication than White youth after exit from the foster care system. Availability and accessibility of mental health services may be a factor where there are fewer groups and other types of mental health services available to youth. A more plausible explanation, however, may lie in the cultural influences associated in the seeking of mental health services and the final case outcome. Findings suggest that the use of individual therapy and psychotropic medication may be indicative of the youth not having a permanency plan in place when exiting the foster care system as a strong support system in the Latino community has been found to have a negative impact on the use of mental health services and psychotropic medication (Cabassa et al., 2008). Similarly, the lack of a support system has been found to increase the use of mental health services as a way to enhance support (Abe-Kim et al., 2002). However, further research is needed to better understand these findings.

Consistent with previous studies (McMillen & Raghavan, 2009), there was a 54% drop in the number of youth who utilized mental health services after exit from the foster care system, however, there appears to be only a slight variation in treatment intensity (i.e., the mean number of services used) while in foster care and after foster care exit (31.69 vs. 37.26 contact hours) for those who remained in treatment. A possible reason for this may be that while less youth utilize mental health services after foster care exit, youth who do continue to use services are heavy users of services—either continue to use heavily or increase their service use once they leave care. This is an area where public mental health systems can provide additional follow-up services for clients who exit the foster care system and may be experiencing challenges in the continuation of services.

Additionally, further research is needed to better understand gaps in mental health service use among racial/ethnic minority youth. Since no racial/ethnic disparities were found while in foster care, exploring the possible challenges and barriers racial/ethnic minority youth experience in continuing to utilize services, or in the provision of services after exit from foster care, is crucial. Given the study’s findings, child welfare and mental health systems can tailor mental health service provision to meet Latino youth’s needs. For example, since individual counseling and psychotropic medication were more likely to be used by Latino youth upon exit from the foster care system, providing more individualized services for Latino youth while in foster care may assist in continued receipt of services. Also, extending group counseling or support groups to youth exiting the foster care system, may improve continued utilization of services once youth leave care. In conjunction with extended foster care, (e.g., the California Fostering Connections to Success Act in California) mental health services can be included as part of the Transitional Independent Living case plan for non-minor dependents (NMDs) to establish, or re-establish, mental health services to better assist youth in their transition to self-sufficiency.

Several limitations need to be noted when considering the findings. First, administrative data were used in the current study, limiting the availability of significant predictor variables. For example, there were no data on mental health diagnosis, which would have shed light on continued used of mental health services and possible reasons for intensity of services. However, it’s important to note that all youth identified as having used mental health services were being seen by the public mental health system, and therefore, had been diagnosed with need for mental health services. Second, because of the use of administrative data, no plausible reasons for disruption of mental health services could be made. Since youth are known to the public mental health system, data should be collected on reasons for service disruption, if the youth is seeking to continue with mental health services once they exit the child welfare system, if a disruption is noted. This can provide a better, and in-depth, understanding as to the reasons for dropping out of services and for seeking to renew services. Third, mental health data were obtained from the public mental health system and transferred to the child welfare system. Mental health service use was obtained from billing claims by the public mental health system, and therefore, may not be a reliable measure of actual mental health service provision. Using specific measures to collect data on actual mental health service provision such as type of services used and intensity of services can provide a better understanding.

References

Abe-Kim, J., Takeuchi, D., & Hwang, W. (2002). Predictors of help seeking for emotional distress among Chinese Americans: Family matters. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70, 1186–1190.

Auslander, W. F., McMillen, J. C., Elze, D., Thompson, R., Jonson-Reid, M., & Stiffman, A. (2002). Mental health problems and sexual abuse among adolescents in foster care: Relationship to HIV risk behaviors and intentions. AIDS and Behavior, 6, 351–359.

Ayon, C., & Marcenko, M. O. (2008). Depression among Latino children in the public child welfare system. Children and Youth Services Review, 30, 1366–1375.

Barksdale, C. L., Azur, M., & Leaf, P. J. (2010). Differences in mental health service sector utilization among African American and Caucasian youth entering systems of care programs. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, 37, 363–373.

Brandford, C., & English, D. (2004). Foster youth transition to independence study. Seattle, WA: Office of Children’s Administration Research, Washington Department of Social and Health Services.

Burley, M., & Halpern, M. (2001). Educational attainment of foster youth: Achievement and graduation outcomes for children in state care. Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy.

Burns, B.J., Phillips, S.D., Wagner, H.R., Barth, R.P., Kolko, D.J., Campbell, Y., et al., (2004). Mental health need and access to mental health services by youth involved with child welfare: A national survey. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43, 960–970.

Cabassa, L. J., Hansen, M. C., Palinkas, L. A., & Ell, K. (2008). Azucar y nervios: Explanatory models and treatment experiences of Hispanics with diabetes and depression. Social Science and Medicine, 66, 2413–2424.

Cabassa, L. J., & Zayas, L. H. (2007). Latino immigrants’ intentions to seek depression care. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77, 231–242.

Courtney, M. E., Dworsky, A., Cusick, G., Havlicek, J., Perez, A., & Keller, T. (2007). Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Outcomes at age 21. Chicago: Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago.

dosReis, S., Zito, J. M., Safer, D. I., & Soeken, K. L. (2001). Mental health services for youths in foster care and disabled youth. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 1094–1099.

Dworsky, A. (2005). The economic self-sufficiency of Wisconsin’s former foster youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 27, 1085–1118.

Dworsky, A., Roller White, C., O’Brien, K., Pecora, P., Courtney, M., Kessler, R., Sampson, N., & Hwang, I. (2010). Racial and ethnic differences in the outcomes of former foster youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 32, 902–912.

Fowler, P. J., Toro, P. A., & Miles, B. W. (2009). Aging out of foster care: Pathways to and from homelessness and associated psychosocial outcomes in young adulthood. American Journal of Public Health, 99, 1453–1458.

Garcia, A., & Courtney, M. (2011). Prevalence and predictors of service utilization among racially and ethnically diverse adolescents in foster care diagnosed with mental health substance abuse disorders. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 5, 521–545.

Garcia, A. R., Pecora, P. J., Harachi, T., & Aisenberg, E. (2012). Institutional predictors of developmental outcomes among racially diverse foster care alumni. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82, 573–584.

Garland, A. F., & Besinger, B. A. (1997). Racial/ethnic differences in court referred pathways to mental health services for children in foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 19, 651–666.

Garland, A. F., Landsverk, J., Hough, R., & Ellis-MacLeod, E. (1996). Type of maltreatment as a predictor of mental health service use for children in foster care. Child Abuse & Neglect, 20, 675–688.

Garland, A. F., Hough, R. L., Landsverk, J. A., McCabe, K. M., Yeh, M., & Ganger, W. C. (2000). Racial and ethnic variations in mental health care utilization among children in foster care. Children’s Services: Social Policy, Research, and Practice, 3, 133–146.

Garland, A. F., Lau, A. S., Yeh, M., McCabe, K. M., Hough, R. L., & Landsverk, J. (2005). Racial and ethinic differences in utilization of mental health services among high risk youth. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162, 1336–1343.

Goerge, R. M., Bilaver, L., Lee, B. J., Needell, B., Brookhart, A., & Jackman, W. (2002). Employment outcomes for youth aging out of foster care. Chicago, IL: Chapin Hall Center for Children.

Halfon, N., Mendoca, A., & Berkowitz, G. (1995). Health status of children in foster care: The experience of the center for the vulnerable child. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 149, 386–392.

Hansen, M. C., & Aranda, M. P. (2012). Sociocultural influences on mental health service uses by Latino older adults for emotional distress: Exploring the mediating and moderating role of informal social support. Social Science and Medicine, 75, 2134–2142.

Harman, J. S., Childs, G. E., & Kelleher, K. J. (2000). Mental health care utilization and expenditures by children in foster care. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 154, 1114–1117.

Harris, M. S., Jackson, L. J., O’Brien, K., & Pecora, P. J. (2009). Disproportionality in education and employment outcomes of adult foster care alumni. Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 1150–1159.

Harris, M. S., Jackson, L. J., O’Brien, K., & Pecora, P. (2010). Ethnic group comparisons in mental health outcomes of adult alumni of foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 32, 171–177.

Heflinger, C. A., Simpkins, C. G., & Combs-Orme, T. (2000). Using the CBCL to determine the clinical status of children in state custody. Children and Youth Services Review, 22, 55–73.

Hill, R. B. (2008). Gaps in research and public policies. Child Welfare, 87, 359–367.

Interian, A., Martinez, I. E., Guarnaccia, P. J., Vega, W. A., & Escobar, J. I. (2007). A qualitative analysis of the perpection of stigma among Latinos receiving antidepressants. Psychiatric Services, 58, 1591–1594.

Jackson, L. J., O’Brien, K., & Pecora, P. J. (2011). PTSD among foster care alumni: The role of race, gender, and foster care context. Journal of Child Welfare, 90, 71–93.

James, S., Landsverk, J., Slymen, D. J., & Leslie, L. K. (2004). Predictors of outpatient mental health service use: The role of foster care placement change. Mental Health Services Research, 6, 127–141.

Joe, S., & Marcus, S. C. (2003). Datapoints: Trends by race and gender in suicide attempts among US adolescents, 1991–2001. Psychiatric Services, 54, 454.

Landsverk, J., & Garland, A. (1999). Foster care and pathways to mental health services. In P. A. Curtis, G. Dale Jr. & J. C. Kendall (Eds.), The foster care crisis: Translating research into policy and practice (pp. 193–210). Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press.

Lenz-Rashid, S. (2006). Employment experiences of homeless young adults: Are they different for youth with a history of foster care? Children and Youth Services Review, 28, 235–259.

Leslie, L., Hurlburt, M., Landsverk, J., Barth, R., & Slymen, D. (2004). Outpatient mental health services for children in foster care: A national perspective. Child Abuse and Neglect, 28, 697–712.

Leslie, L. K., Landsverk, J., Ezzet-Lofstrom, R., Tschann, J. M., Slymen, D. J., & Garland, A. F. (2000). Children in foster care: Factors influencing outpatient mental health service use. Child Abuse and Neglect, 24, 465–476.

Leslie, L. K., Raghavan, R., Zhang, J., & Aarons, G. (2010). Rates of psychotropic medication use over time among youth in child welfare/child protective services. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 20, 135–143.

Leslie, L. K., Weckerly, J., Landsverk, J., Hough, R. L., Hurlburt, M. S., & Wood, P. (2003). Racial/ethnic differences in the use of psychotropic medication in high-risk children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42, 1433–1442.

McMillen, J. C., & Raghavan, R. (2009). Pediatric to adult mental health service use of young people leaving the foster care system. Journal of Adolescent Health, 44, 7–13.

McMillen, J. C., Zima, B., Scott, L., Auslander, W., Munson, M., Ollie, M., & Spitznagel, E. (2005). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among older youths in the foster care system. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry, 44, 88–95.

McMillen, J. C., Zima, B., Scott, L. D., Ollie, M., Munson, M. R., & Spitznagel, E. (2004). The mental health service use of older youth in foster care. Psychiatric Services, 55, 811–817.

Munson, M. R., & Lox, J. A. (2012). Clinical social work practice with former system youth with mental health needs: Perspective of those in need. Clinical Social Work Journal, 40, 255–260.

Munson, M. R., Narendorf, S. C., & McMillen, J. C. (2011). Knowledge of and attitudes towards behavioral health services among older youth in the foster care system. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 28, 97–112.

Munson, M. R., Scott, L. D., Smalling, S. E., Kim, H., & Floersch, J. E. (2011). Former system youth with mental health needs: Routes to adult mental health care, insight, emotions, and mistrust. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 2261–2266.

Naccarato, T., Brophy, M., & Courtney, M. E. (2010). Employment outcomes of foster youth: The results from the Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of foster youth. Children and Youth Services Review, 32, 551–559.

Pecora, P. J., Kessler, R. C., O’Brien, K., White, C. R., Williams, J., Hiripi, E., English, D., White, J., & Herrick, M. A. (2006). Educational and employment outcomes of adults formerly placed in foster care: Results from the Northwest Foster Care Alumni Study. Children and Youth Services Review, 28, 1459–1481.

Pecora, P. J., Williams, J., Kessler, R. C., Downs, A. C., O’Brien, K., Hiripi, E., & Morello, S. (2003). Assessing the effects of foster care: Early results from the Casey National Alumni Study. Seattle, WA: Casey Family Programs.

Raghavan, R., Inoue, M., Ettner, S. L., Hamilton, B. H., & Landsverk, J. (2010). A preliminary analysis of the receipt of mental health services consistent with national standards among children in the child welfare system. American Journal of Public Health, 100, 742–749.

Raghavan, R., Zima, B. T., Andersen, R. M., Leibowitz, A. A., Schuster, M. A., & Landsverk, J. (2005). Psychotropic medication use in a national probability sample of children in the child welfare system. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 15, 97–106.

Ringeisen, H., Casanueva, C. E., Urato, M., & Stambaugh, L. F. (2009). Mental health service use during the transition to adulthood for adolescents reported to the child welfare system. Psychiatric Services, 60, 1084–1091.

Rubin, D. M., Alessandrini, E. A., Feudtner, C., Mandell, D. S., Localio, A. R., & Hadley, T. (2004). Placement stability and mental health costs for children in foster care. Pediatrics, 113, 1336–1341.

Shin, S. (2005). Need for and actual use of mental health service by adolescents in the child welfare system. Children and Youth Services Review, 27, 1071–1083.

Shore, N., Sim, K. E., LeProhn, N. S., & Keller, T. E. (2002). Foster parent and teacher assessment of youth in kinship and non-kinship foster care placement: Are behaviors perceived differently across settings? Children and Youth Services Review, 24, 109–134.

Siegel, C. E., Wanderling, J., Haugland, G., Laska, E. M., & Case, B. G. (2013). Access to and use of non-inpatient services in New York State among racial-ethnic groups. Psychiatric Services, 64, 156–164.

Snowden, L. R. (2007). Explaining mental health treatment disparities: Ethnic and cultural differences in family involvement. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry, 31, 389–402.

Staudt, M. M. (2003). Mental health services utilization by maltreated children: Research findings and recommendations. Child Maltreatment, 8, 195–203.

Timmer, S., Sedlar, G. G., & Urquiza, A. J. (2004). Challenging children in kin versus nonkin foster care: Perceived costs and benefits to caregivers. Child Maltreatment, 9, 251–262.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau (2012). The AFCARS report no. 19: Preliminary FY 2011 estimates as of July 2012. Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/afcarsreport19.pdf.

Villagrana, M. (2010). Pathways to mental health services for children and youth in the child welfare system: A focus on social workers’ referral. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 27, 435–449.

Villatoro, A. P., Morales, E. S., & Mays, V. M. (2014). Family culture in mental health help-seeking and utilization in a nationally representative sample of Latinos in the United States: The NLASS. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84, 353–363.

Villegas, S., & Pecora, P. J. (2012). Mental health outcomes for adults in family foster care as children: An analysis by ethnicity. Children and Youth Services Review, 34, 1448–1458.

Yeh, M., McCabe, K., Hurlburt, M., Hough, R., Hazen, A., Culver, S., … Landsver, J. (2002). Referral source, diagnoses, and service type of youth in public outpatient mental health care: A focus on ethnic minorities. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, 29, 45–60.

Zima, B. T., Bussing, R., Yang, X., & Belin, T. R. (2000). Help-seeking steps and service use for children in foster care. The Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, 27, 271–285.

Zito, J. M., Safer, D. J., Sai, D., Gardner, J. F., Thomas, D., Coombes, P., Dubowski, M., & Mendez-Lewis, M. (2008). Psychotropic medication patterns among youth in foster care. Pediatrics, 121, 157–163.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Author declares no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Villagrana, M. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Mental Health Service Use for Older Foster Youth and Foster Care Alumni. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 34, 419–429 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-016-0479-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-016-0479-8