Abstract

This study examined knowledge of and attitudes toward services among 268 17-year olds with psychiatric diagnoses preparing to exit foster care. A structured interview assessed knowledge of services with vignette scenarios and attitudes with a standardized scale. Descriptive statistics described the extent of knowledge and attitudes among this population and regression analyses examined predictors of these dimensions of literacy. Most youth suggested a help source, but responses often lacked specificity. Gender and depression were the strongest predictors of knowledge and attitudes, respectively. Knowing which aspects of literacy are low, and for whom, can inform education efforts to improve access to care in adulthood.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2006, over 26,500 older youth were “emancipated” from foster care (United States Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS] 2008). The poor behavioral health of many older youth in the process of exiting foster care, along with those who have exited care, has been well documented, including consistent reports of high rates of depression and substance use (Barth 1990; Courtney and Dworsky 2006; McMillen et al. 2005). While in the child welfare system, foster youth are heavy mental health service users (McMillen et al. 2004), however, a recent study documented a marked decrease in use of mental health services, including outpatient therapy and psychiatric medications, after youth left care (McMillen and Raghavan 2009). Mental disorders are often chronic conditions that persist into adulthood. Therefore, research suggesting that service use declines during the transition to adulthood is a pressing public health matter that needs further systematic investigation.

One factor that may be related to service continuity is behavioral health literacy, or possessing the knowledge and positive attitudes toward help-seeking necessary to transition to adult behavioral health services. Jorm has conceptualized mental health literacy as knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders which aid in their recognition, management and prevention (Jorm 2000; Jorm et al. 1997). Mental health literacy has multiple dimensions: (1) the ability to recognize a mental disorder; (2) knowledge about risk factors and causes of the disorder; (3) knowledge and beliefs about help sources; (4) attitudes toward help-seeking; and (5) knowledge of how to seek mental health information (Jorm 2000). Knowledge and positive attitudes may be increasingly necessary when an individual is attempting to resolve his/her own or a loved one’s mental health difficulties, particularly in adulthood when health care decisions and actions are made more independently, without as much guidance from caregivers (Sawyer and Aroni 2005). Older youth exiting foster care are at heightened risk for service disruption, as they leave behind providers who have often facilitated their mental health service use. As adults, former foster youth’s own levels of behavioral health literacy become paramount in facilitating continuous care for mental health needs.

The present study focuses on two dimensions included in Jorm’s conceptualization of mental health literacy, namely knowledge and attitudes toward professional psychological services. In the present study the concept is broadened to behavioral health literacy, as the vignettes include a scenario regarding substance abuse. The present study is one of only a few studies that examine behavioral health literacy among a sample with indicated objective need for services, in this case a lifetime history of a DSM-IV mental disorder. Most studies have examined mental health literacy in the general population. Information from this study can help professionals tailor interventions to those at highest risk and target specific aspects of literacy where older youth in foster care evidence little knowledge, or particularly negative attitudes.

Previous Research

Behavioral Health Literacy Among Youth Involved with Public Systems of Care

There has been almost no research conducted on any aspect of behavioral health literacy among older youth in foster care, or other groups of youth involved with public systems of care, hereafter referred to as system youth. One study examining the service experiences of older foster youth found that those reporting only negative experiences with mental health care also reported significantly less positive attitudes toward mental health services (Lee et al. 2006). Two other studies present results that implicitly address aspects of behavioral health literacy among system youth. In a longitudinal study of older foster youth, many participants stopped using services at age 19 due to a lack of perceived need for services, reporting that once the decision to seek mental health care was up to them they discontinued use (McMillen and Raghavan 2009). Another study reported barriers to services that are suggestive of low levels of behavioral health literacy among youth in detention, such as participant’s views that mental health problems will go away on their own, that they do not need help, and, a lack of knowledge of where to go for help (Abram et al. 2008). Abram et al. (2008) also found that attitudes were similar across gender and race/ethnicity. Due to the scant literature on aspects of behavioral health literacy among system youth, the present study was also informed by the larger body of literacy research on mental health literacy.

Literacy in the General Population

Knowledge

Studies have examined mental health literacy in the general population utilizing vignette methodologies. One study found that among 12–25 year-olds, females were significantly more likely to correctly identify a vignette as evidencing depression. Also, males were more likely to endorse dealing with depression through the use of alcohol, while females were more likely to endorse seeing a professional, such as a doctor or a psychologist (Cotton et al. 2006). Utilizing a telephone survey, another study found that males were less aware of depression initiatives and those that were less aware of depression initiatives were less likely to rate professional mental health services as helpful in dealing with depression (Morgan and Jorm 2007). Finally, Lauber and colleagues examined literacy among college students and found that previous service use was related to increased mental health literacy (Lauber et al. 2005).

Attitudes

Attitudes toward mental health services have been found to be an important predictor of service engagement and adherence (Scott and Pope 2002). Thus, researchers have begun to focus investigations on understanding attitudes. Studies consistently show that females report more positive attitudes toward help-seeking than males (Chandra and Minkovitz 2006; Gonzalez et al. 2005). Findings on race are more mixed. Some studies have found that African Americans are more concerned about stigma than their white counterparts (Munson et al. 2009; Roeloffs et al. 2003), while other studies indicate that African Americans in the general population endorse more positive attitudes toward mental health services (Schomerus et al. 2009). Another factor that has been found to be associated with attitudes toward mental health services is previous use of services (Lee et al. 2006; Mojtabai 2007; Schomerus et al. 2009), with the National Comorbidity Study (NCS) and its replication, the NCS-R, reporting that previous experience of mental health treatment seeking was associated with more positive attitudes toward services (Schomerus et al. 2009).

The Present Study

This study examined knowledge and attitudes in a high risk group of young people who have both heightened vulnerability for mental health problems and heightened risk of service disruption. In addition to predictors identified in the literature, the present study included indicators that may heighten youth’s future need for mental health or substance use services including maltreatment history, which has been found to be related to mental disorders in adulthood (Chapman et al. 2004) and participation in risk behaviors (e.g., substance use, arrest history) (Anda et al. 2002). In this study, geographic region was also examined, as programs and services can vary by region (McMillen et al. 2004). Knowledge and attitudes are conceptualized as potential points of intervention to assist these youth in accessing services they may need when they leave the child welfare system. There are no studies to our knowledge that have examined the relationships between maltreatment history, geographic region or risk behaviors and how these variables are related to knowledge and attitudes toward services.

Study Aims and Hypotheses

The present study utilized a sample of 268 17-year old youth aging out of foster care who had met the criteria for a DSM-IV mental disorder (including substance use disorders) in order to address the following research aims: (1) To describe the knowledge (e.g., knowledge of what to do when help is needed and the level of specificity of the knowledge of what to do) and attitudes toward professional mental health services among this vulnerable population of youth and (2) To examine the correlates of both knowledge and attitudes toward services. Based on previous literature and clinical experience the authors tested the following hypotheses: (1) females will have more positive attitudes toward services than their male counterparts; (2) previous service use will be related to higher levels of behavioral health literacy (knowledge and attitudes); (3) low knowledge and negative attitudes toward services will be related to a constellation of high risk behaviors, which both heighten the need for services and decrease the likelihood of seeking services; (4) Behavioral health literacy will be associated with where youth live in the state, race, and clinical characteristics.

Research Design and Methods

Participants and Procedures

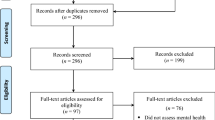

The sample for the present study included 268 youth who met the criteria for a DSM-IV substance use disorder (n = 122) or other mental disorder (n = 244) during their lifetime. Rates of co-morbidity were high with 61% of the sample meeting criteria for more than one disorder (n = 163). Lifetime disorders were chosen as an indicator of need rather than current disorders due to the cyclical nature of many mental disorders. In addition, childhood diagnoses have been associated with mental health problems in adulthood (Copeland et al. 2009) and our study was geared toward understanding dimensions of behavioral health literacy among those who may need professional services at some point in early adulthood. Participants were part of a larger study of youth transitioning out of foster care in Missouri. All youth in the foster care system turning 17 between December 2001 and May 2003 in eight counties of Missouri were considered for the study. Child welfare workers screened youth for potential inclusion, excluding youth who had IQ scores below 70, those in placements over 100 miles away, and/or those on continual runaway for 45 days past their 17th birthday. Of the 451 youth who were determined to be eligible for the study, 90% were interviewed (N = 404). Trained professional interviewers administered a structured interview to each youth at his or her place of residence. Interviews lasted 1–2 h and youth were compensated $40. Caseworkers provided informed consent and youth gave assent. The University’s Human Subjects Committee approved the study procedures.

Measurement

Demographics

Data on race and gender were collected and utilized as independent variables in this study. Participants self-identified their race. This variable was then recoded into Caucasian (n = 137) and youth of color (n = 131), which included those that self-identified as black/African American (n = 114) and the small number of youth that self-identified as non-white/Caucasian and non-black/African American, for example, Mexican (n = 1), American Indian (n = 2), Middle Eastern (n = 1), Pacific Islander (n = 1), and Bi-racial or multiracial (n = 12) in the sample. The racial distribution in our sample is typical of foster care populations in this region. Gender was recorded by the interviewer and was dummy coded as 0 = Female (n = 150), 1 = Male (n = 118).

Geographic Region

Interviewers also recorded the county in which the young person’s child welfare case originated. The counties were then grouped into regions with similar characteristics—St. Louis City, St. Louis County, suburbs around St. Louis, and Southwest Missouri. Each was dummy coded, with St. Louis City used as the reference group in multivariate analyses.

Abuse History

Physical abuse and physical neglect were measured using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (Bernstein and Fink 1998). Sexual abuse was measured using 3 items adapted from Russell (Russell 1986). Dichotomous indicators for physical abuse and physical neglect were created using cut off scores recommended by Bernstein and Fink (e.g., >10 for physical abuse and physical neglect) for severe or moderate maltreatment. If youth answered yes to any of the three items developed from the work of Russell they met criteria for sexual abuse. An example of the three sexual abuse items is, “Has anyone ever made you touch their private parts, against your wishes?”

History of Mental Disorder

Interviewers assessed for lifetime history of major depression, mania, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version IV (Robins et al. 1995). Prior studies of the reliability of the instrument have reported the instrument to have fair to excellent reliability in diagnosing substance abuse and dependence (kappa = .53–.86) and fair to good reliability in diagnosing conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, depression, mania and PTSD (kappa = .40–.67) (Dascalu et al. 2001; Horton et al. 1998). In the present study, youth who met criteria for either conduct disorder (CD) or oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) were included in the unified category of disruptive behavioral disorder (DBD). Consistent with previous research on the reliability of self-report of ADHD diagnosis among juveniles (Teplin et al. 2002), the age of onset criteria was not included in determination of eligibility for a lifetime ADHD diagnosis. Questions from the Comprehensive Addiction Severity Index for Adolescents were used to assess DSM-IV criteria for lifetime substance abuse and substance dependence (Myers 1994). Recent tests of reliability for the drug and alcohol addiction subscale of this instrument have reported a coefficient alpha of .86 and a test–retest correlation statistic of .95 (Myers et al. 2006). Youth who met the criteria for a substance abuse or substance dependence disorder in their lifetime were classified as having a substance use disorder and included in the study sample.

Service Use

Interviewers asked youth about their history of mental health services using questions from the Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (Stiffman et al. 2000). Questions were included about lifetime history of outpatient psychological services, residential treatment, inpatient hospitalization, and current use of psychotropic medications. This instrument has demonstrated good to excellent test retest reliability, between .63 to .96, for lifetime service use among children over age 10 (Horwitz et al. 2001).

Risk Behaviors

Substance Use

Alcohol and marijuana use were measured with items modified from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, Version IV (Robins et al. 1995). For this analysis, drinking was dichotomized by whether the respondent had been drunk within the past 6 months. Marijuana use was dichotomized by whether the respondent had smoked marijuana in the month prior to the interview.

History of Arrest and Sexual Activity

Two additional variables were used as indicators of youth at higher risk based on behaviors identified in research on youth problem behaviors (Donovan and Jessor 1985). Single items asked youth whether they had ever been arrested in their lifetime and whether they had ever had sex.

Behavioral Health Literacy

Knowledge

Responses to three vignettes (see Table 1) were utilized about youth in different crisis situations to assess knowledge of services. The vignettes were created by a research clinician who had experience working with adolescents and were designed to present situations in which there was a clear clinical need for service. Vignettes were pilot tested and revised prior to inclusion in the final interview. The pilot survey was administered to a small sample of youth who were still in foster care and another group of youth who were out of care, providing some variability to ensure comprehension and clarity of the vignettes. The three items presented scenarios of a seriously depressed youth with suicidal ideation, a youth posing a danger to others, and a youth with a serious substance abuse problem. Interviewers read vignettes to the youth and followed up with a general question, “What are some things you could do to get him/her some help?” The interviewer then followed up with probes designed to see if the youth could describe their actions more specifically. Investigators coded open-ended responses into six categories: (0) No help is needed; (1) I’d help/Peer help/Don’t know; (2) Enlist a responsible adult; (3) Enlist a professional helper; (4) Knows the name of an agency or service; and (5) Knows name of agency/service and has justification for service. Raters trained on a sample of responses rated cases until they reached 90% agreement. Once established, one rater rated the remaining cases. For some analyses, codes were collapsed into three levels of knowledge: (1) Little to none (0 and 1); (2) Some knowledge (2 and 3); and (3) Specific knowledge of where to get help (4 and 5). Finally, an index of behavioral health knowledge was created by summing the ratings in each of the three areas of knowledge for an overall knowledge score with a range from 0 to 15.

Attitudes

To measure attitudes, a modified version of the confidence in providers subscale of the Attitudes Toward Seeking Professional Psychological Help (Fischer and Turner 1970) was utilized. This scale asks questions such as “If I believed I was having a mental breakdown, my first thought would be to get professional attention.” Respondents rated their level of agreement with each item on a 5 point scale from strongly disagree (0) to strongly agree (4). Our modifications involved updating some of the language and adding the item “I think medication for emotional or behavioral problems can be helpful for many people.” The scale was created by summing each of the nine Likert items where 0 indicated a strongly negative response to the item and 4 indicated a strongly positive response. For analysis, the items were reverse coded where appropriate and summed into a scale from 0 to 36. The reliability alpha of the scale for our sample was .75.

Analysis

Analyses were done in a series of steps. In the present study less than 1% of the data were missing due to study protocols that called for recontacting youth if data were missing due to interviewer error. We chose to use the hot-decking method to handle the small amount of missing data that remained, as it has been shown to outperform other methods, such as mean substitution (Saunders et al. 2006). Descriptive statistics were examined with univariate analyses and then bivariate relationships were assessed utilizing chi-squares, t-tests, analysis of variance and correlations. Relationships that were significant at the bivariate level (p < .10) were entered into multivariate models, utilizing ordinary least squares regression in SAS 9.1.

Results

Describing Behavioral Health Literacy Among Older Youth in Foster Care

Overall ratings in categories of knowledge (e.g., little to none, some, and specific), along with sample responses for each category by vignette as shown in Table 1 above. When presented with the vignette on cocaine, the large majority (91%) of older youth had a sense of what to do, either with general knowledge of the type of help needed (62%) or knowledge of a specific agency/service and/or a knowledge of agency/service and a justification for the service (29%). Few responded with little to no knowledge (8%), stating, for example, “Tell him to stay with me and I’ll keep him off of it” or “I don’t know what to do.” The most common type of response to this vignette was a general statement with some knowledge to enlist help, for example, “Call a rehab center…look in telephone book.” In contrast, when responding to the vignette evidencing danger to others only 10% had specific knowledge of what to do and where to go. Twenty-eight percent reported little to no knowledge about what to do. Finally, with regard to the vignette on danger to self, which evidences symptoms common to depression, 31% of the youth had little to no knowledge of what to do, reporting the individual in the vignette should “deal with it,” “go to work,” or “take some time off”. These responses indicate a failure to recognize the symptoms of depression, the need for professional attention and the myriad of services available to help someone experiencing these symptoms. Fifty-six percent had some knowledge but only 13% (34 youth out of 268), reported specific knowledge, such as “Get help, talk to people, talk to counselors and pastors at church…we have our own counselor at church and she is cool.” Only a small minority of youth knew where to go when faced with a hypothetical scenario that involved depressive symptoms or danger to others compared to almost one-third of respondents who reported a specific named professional service to enlist for help regarding the situation evidencing substance abuse.

Examining the responses that were coded as “specific knowledge” help to shed light on the services that the most knowledgeable older youth in the process of exiting foster care considered when thinking about help-seeking. With regard to the crack cocaine vignette, most youth recommended a referral to Narcotics Anonymous or Alcoholics Anonymous. Others recommended a specific treatment center, or rehabilitation centers. Of note, some emphasized a combination of plans, such as referral to treatment and providing housing and a few made a point to report that they would stick with the person throughout the process. When examining the “specific knowledge” suggestions for the vignette evidencing depressive symptoms, the suggestions, almost uniformly recommended doctors/psychiatrist, counselors, or specific hospitals. A few youth recommended medication or talking to friends or a clergy member, but these suggestions were always secondary to the professional(s) noted above. Finally, with regard to danger to others, there was more variety in the suggestions. Some suggested referral to a hospital for immediate hospitalization. Others talked about combinations of talking with the person, and some type of therapy or counseling. Many suggested calling specific hotlines or the police and a few suggested they would take the gun away and then make one of the suggested referrals.

Correlates of Knowledge

The index of knowledge was normally distributed (skewness = −.52) with a mean score of 7.78 (SD = 2.16) on a scale from 0 “No knowledge” to 15 “Specific knowledge.” Bivariate relationships between each independent variable and knowledge were examined using t-tests and analysis of variance. Female youth reported higher levels of knowledge than males (t = 5.08, p < .0001). Caucasian youth reported higher levels of knowledge when compared to the youth of color (t = 3.43, p < .001). Further, older youth with histories of depression and PTSD had higher levels of knowledge than those who had never met the criteria for those disorders (t = −4.71, p < .0001; t = −2.95, p < .01). Those who had utilized inpatient hospital services had more knowledge than those who had not utilized this mental health service (t = −2.37, p < .05). And, compared to participants indicating no sexual and physical abuse, those who did report sexual abuse (t = −3.59, p < .001) and physical abuse (t = −1.90, p < .10) during their childhoods scored higher on the measure of knowledge. Finally, the participants engaging in high risk behaviors had less knowledge than their counterparts who had not engaged in these behaviors.

In the multivariate model (see Table 2 below), being male (β = −.19, SE = .28, p < .005) and being a youth of color (β = −.16, SE = .32, p < .05) were significantly related to lower levels of behavioral health knowledge, when compared to females and white youth, respectively. Whereas having a history of depression (β = .13, SE = .27, p < .05) was related to higher levels of knowledge, when compared to those who did not meet the criteria for depression. Finally, having been drunk in the past 6 months was related to less knowledge (β = −.13, SE = .35, p < .05). The final model was significant (F = 5.51, p < .0001) and it explained 23% of the variance in behavioral health knowledge.

Correlates of Attitudes

The attitudes scale was normally distributed (skewness = −.58) and centered around the midpoint on the scale, with a mean score of 20.75 (SD = 5.89) on a scale from 0 to 36. For individual attitude items, mean scores ranged from 1.66 to 2.49. Bivariate relationships between each independent variable and attitudes were examined using t-tests, analysis of variance, and correlations. Female youth had significantly more positive attitudes toward services than males (t = 2.20, p < .05). Youth who met the criteria for history of depression (t = −4.16, p < .0001) or posttraumatic stress disorder (t = −2.05, p < .05) had more positive attitudes when compared to older youth who had not met the criteria for those disorders. Each of the risk variables were significantly related to attitudes at the level of p < .10 or lower. In each case, youth who identified as engaging in the risk behavior had significantly lower scores, indicating less positive attitudes toward seeking professional help.

Regression results are presented in Table 2 below. The model was significant (F = 5.68, p < .0001), explaining 15% of the variance in attitude scores. Depression was the strongest predictor of attitudes (β = .17, SE = .76, p < .01), with participants who had a history of depression reporting more positive attitudes toward services. Also, risk behaviors, such as having a history of arrest (β = −.13, SE = .72, p < .05), drinking in the past 6 months (β = −.15, SE = .97, p < .05) and ever having had sexual intercourse (β = −.15, SE = .84, p < .05) were associated with lower scores on the attitude scale.

Discussion

This is the first study to systematically examine the knowledge of and attitudes toward professional psychological services among older youth nearing their exit from foster care. Research in this area is critical, as many in this vulnerable sub-population of youth will continue to need services and access to them in adulthood. In the present study, older youth reported moderate levels of knowledge and fairly positive attitudes toward mental health services. Several of the findings were noteworthy and deserve further comment. First, the number of youth able to report named providers was fairly low, with most youth reporting a need to enlist help, but with little specificity or justification for why help is needed. Participants had the most knowledge about substance use services but much less specific knowledge regarding what to do when faced with situations evidencing depression and danger to others. It is possible that youth are more willing to admit that they know about “rehab” because substance use and dependence is more socially acceptable and/or less stigmatizing than mental illnesses, such as depression. Another possible explanation is that participants have had more exposure to awareness campaigns regarding substance use in their schools and communities (e.g., DARE) compared to campaigns addressing violence toward others or depression. Depression is a common mental disorder among this group and the lack of specific knowledge about it suggests a need for behavioral health professionals to develop new strategies for educating older youth about how to recognize depression, along with where and how to access services for depressive symptoms.

Second, our hypothesis that females would possess more behavioral health literacy when compared to their male peers was supported, as females reported higher levels of both knowledge and attitudes toward services (bivariately). These differences may be due to socialization. In American society, females are more often socialized to reach out for help, while males are often advised to keep their emotions inside and face their difficulties on their own, which ultimately may result in less knowledge of help sources (Tamres et al. 2002).

Third, in the present study having a history of depression was related to more knowledge and to more positive attitudes toward services. One explanation may be that youth with depression have received services that work. Efficacious treatments for depression among adolescents exist (David-Ferdon and Kaslow 2008), whereas some other childhood disorders (e.g., DBD) have less evidence for effective treatments. It is possible that these youth, compared to those with a history of another mental disorder, may have had more positive experiences with services that are efficacious and thus, they may have more confidence in these services. Interestingly, large national studies have found that people with depression are more likely to seek services, when compared to those meeting the criteria for other mental disorders (Wang et al. 2005). This may be related to increased knowledge and more positive attitudes. More research is needed to examine the relationships between mental disorders, behavioral health literacy, and service use, particularly among young adults. Together, these data highlight the need to target literacy programs for older adolescents and young adults with mental disorders other than depression.

Finally, the exploration of risk behaviors and behavioral health literacy proved to be fruitful. Risky behaviors were significantly associated with more negative attitudes toward professional mental health services. These results are not causal, but they suggest that youth who are drinking and getting involved in criminal behavior have negative attitudes toward professional psychological help. If this finding is replicated it may be worth developing programs tailored specifically to improve the knowledge of and attitudes toward professional mental health services among youth with histories of high risk behaviors.

There are limitations to consider in this research. Generalizability is limited, as our study includes youth from one state; however, sampling from distinct regions does increase comparability to other states. Our study relied on self-report, which can lead to recall difficulties and social desirability. The study may also underestimate knowledge, as interviewers probed only once to uncover knowledge of specific services. In addition, our measure of attitude specifically measured attitude toward mental health services rather than behavioral health services more broadly. Given the variation in knowledge across services, it may be important to assess attitudes more specifically toward different types of services. Also the present study made multiple bivariate comparisons and did not utilize the Bonferroni correction to assess significance, thereby increasing the possibility of a Type I error. Given the relatively small size of our sample, we chose not to utilize this conservative approach and increase the potential of making a Type II error. Finally, the authors acknowledge that knowledge and attitudes are only two dimensions of a more complex set of factors related to service use and engagement in adulthood. Future research is needed that includes examination of knowledge and attitudes within a broader context of factors that includes previous experiences of mental health service use and youth’s actual intentions to seek services when they are able to do so on their own. In spite of these limitations, this study provides a starting point for continued research to build understanding regarding the knowledge of and attitudes toward professional services among older youth in the foster care system. This knowledge can be used to develop interventions to assure these vulnerable youth know how to get services once they are adults. Such interventions should include information on recognizing health problems, knowing specifically where youth can turn for help, and how to go about engaging help sources.

Implications

The documented difficulties of older youth in the foster care system do not disappear when they leave the formal care system. In fact, it is probable that for many of these youth their behavioral health needs, along with their need for formal and informal help, only intensify. A critical avenue to receiving such help is literacy, or knowledge and attitudes toward behavioral health services. Without knowing what kind of help is needed and where to get it, these youth may fail to reach out for help, causing their problems to escalate into crisis situations, such as homelessness and expensive psychiatric crises. Understanding behavioral health literacy in and of itself is an important step to developing programs to help older system youth transition to adulthood. Thus, providers should assess knowledge of and attitudes toward professional psychological services as part of standard practice. Assessments will inform professionals as to who needs more education. In understanding what these youth do and do not know, professionals can tailor their efforts in programs, such as independent living programs, partial hospitalization programs, intensive outpatient programs (e.g., Assertive Community Treatment) and substance use programs to educate older youth on what kind of help exists and how to go about accessing help sources. In addition, it is critical for professionals to consider ways to improve young adult’s attitudes toward professional help sources, which may ultimately prevent the need for higher levels of more costly care. Focusing on youth who report high risk behaviors, such as having an arrest history and utilizing drugs may prove to be most beneficial, as these youth have the most negative attitudes. It may be prudent to utilize peer-educators to combat the negative attitudes and beliefs that some of these youth possess. Educating through the voice of someone who the youth perceive as similar may be a more effective strategy for communicating information. In addition, formats that utilize internet based information are increasingly being utilized to promote increased behavioral health literacy, including mental health literacy, among young people in the general population (Rickwood et al. 2007). These approaches may be a cost effective and youth friendly way of providing education and improving attitudes for older foster youth. Targeted interventions delivered to these youth prior to their exit from foster care can assist in arming them with the behavioral health literacy they will need in order to negotiate adult service systems.

References

Abram, K. M., Paskar, L. D., Washburn, J. J., & Teplin, L. (2008). Perceived barriers to mental health services among youths in detention. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(3), 301–308.

Anda, R. F., Whitfield, C. L., Felitti, V. J., Chapman, D., Edwards, V. J., Dube, S. R., et al. (2002). Adverse childhood experiences, alcoholic parents, and later risk of alcoholism and depression. Psychiatric Services, 53(8), 1001–1009.

Barth, R. P. (1990). On their own: the experiences of youth after foster care. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 7(5), 419–440.

Bernstein, D. P., & Fink, L. (1998). The child trauma questionnaire manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation.

Chandra, A., & Minkovitz, C. S. (2006). Stigma starts early: Gender differences in teen willingness to use mental health services. Journal of Adolescent Health, 38, 754.e1–754.e8.

Chapman, D. P., Whitfield, C. L., Felitti, V. J., Dube, S. R., Edwards, V. J., & Anda, R. F. (2004). Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. Journal of Affective Disorders, 82(2), 217–225.

Copeland, W. E., Shanahan, L., Costello, J., & Angold, A. (2009). Childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders as predictors of young adult disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 66(7), 764–772.

Cotton, S. M., Wright, A., Harris, M. G., Jorm, A. J., & McGorry, P. D. (2006). Influence of gender on mental health literacy. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 40, 790–796.

Courtney, M. E., & Dworsky, A. (2006). Early outcomes for young adults transitioning from out-of-home care in the USA. Child and Family Social Work, 11(3), 209–219.

Dascalu, M., Compton, W. M., Horton, J. C., & Cottler, L. B. (2001). Validity of DIS-IV in diagnosing depression and other psychiatric disorders among substance users. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 63, 37, cited at http://epi.wustl.edu/dis/disPSYCHOMETRICPROPERTIES_NEW.htm. Accessed 31 Aug 2010.

David-Ferdon, C., & Kaslow, N. J. (2008). Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37(1), 62–104.

Donovan, J. E., & Jessor, R. (1985). Structure of problem behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53(6), 890–904.

Fischer, E. H., & Turner, J. L. (1970). Orientations to seeking professional help: Development and research utility of an attitude scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 35, 79–90.

Gonzalez, J. M., Alegria, M., & Prihoda, T. J. (2005). How do attitudes toward mental health treatment vary by age, gender, and ethnicity/race in young adults? Journal of Community Psychology, 33(5), 611–629.

Horton, J., Compton, W. M., & Cottler, L. B. (1998). Assessing psychiatric disorders among drug users: Reliability of the revised DIS-IV. In L. Harris (Ed.), NIDA research monograph- problems of drug dependence. Washington, DC: NIH Publication No. 99-4395, cited at http://epi.wustl.edu/dis/disPSYCHOMETRICPROPERTIES_NEW.htm. Accessed 31 Aug 2010.

Horwitz, S. M., Hoagwood, K., Stiffman, A. R., Summerfeld, T., Weisz, J. R., Costello, E. J., et al. (2001). Reliability of the services assessment for children and adolescents. Psychiatric Services, 52(8), 1088–1094.

Jorm, A. F. (2000). Mental health literacy: Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 177, 396–401.

Jorm, A. F., Kortean, A. E., Jacomb, P. A., Christensen, H., Rodgers, B., & Pollitt, P. (1997). Mental Health Literacy: A survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Medical Journal of Australia, 166, 182–186.

Lauber, C., Ajdacic-Gross, V., Fritschi, N., Stulz, N., & Rossler, W. (2005). Mental health literacy in an educational elite—an online survey among university students. BMC Public Health, 5(44), 1–9.

Lee, B. R., Munson, M. R., Ware, N. C., Ollie, M. T., Scott, L. D., & McMillen, J. C. (2006). Experiences of and attitudes toward mental health services among older youths in foster care. Psychiatric Services, 57, 487–492.

McMillen, J. C., & Raghavan, R. (2009). Pediatric to adult mental health service use of young people leaving the foster care system. Journal of Adolescent Health, 44(1), 7–13.

McMillen, J. C., Zima, B. T., Scott, L. D., Auslander, W. E., Munson, M. R., Ollie, M., et al. (2005). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders among older youths in the foster care system. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 44(1), 88–95.

McMillen, J. C., Zima, B., Scott, L. D., Ollie, M., Munson, M. R., & Spitznagel, E. (2004). The mental health service use of older youth in foster care. Psychiatric Services, 55(7), 811–817.

Mojtabai, R. (2007). Americans’ attitudes toward mental health treatment seeking: 1990–2003. Psychiatric Services, 58, 642–654.

Morgan, A., & Jorm, A. (2007). Awareness of beyondblue: The national depression initiative in Australian young people. Australasian Psychiatry, 15(4), 329–333.

Munson, M. R., Floersch, J. E., & Townsend, L. (2009). Attitudes toward mental health services and illness perceptions among adolescents with mood disorders. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 26(5), 447–466.

Myers, K. (1994). Comprehensive addiction severity index for adolescents. In T. McClellan & R. Dembo (Eds.), Screening and assessment of alcohol- and other drug-abusing adolescents. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Myers, K., Hagan, T. A., McDermott, P., Webb, A., Randall, M., & Frantz, J. (2006). Factor structure of the Comprehensive Adolescent Severity Inventory (CASI): Results of reliability, validity, and generalizability analyses. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 32, 287–310.

Rickwood, D. J., Deane, F. P., & Wilson, C. J. (2007). When & how do young people seek professional help for mental health problems. Medical Journal of Australia, 187(7), S35–S39.

Robins, L., Cottler, L., Bucholz, K., & Compton, W. (1995). Diagnostic interview schedule for DSM-IV. St. Louis: Washington University in St. Louis.

Roeloffs, C., Sherbourne, C., Unutzer, J., Fink, A., Tang, L., & Wells, K. B. (2003). Stigma and depression among primary care patients. General Hospital Psychiatry, 25, 311–315.

Russell, D. E. H. (1986). The secret trauma: Incest in the lives of girls and women. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Saunders, J. A., Morrow-Howell, N., Spitznagel, E., Dore, P., Proctor, E. K., et al. (2006). Imputing missing data: A comparison of methods for social work researchers. Social Work Research, 30(1), 19–31.

Sawyer, S. M., & Aroni, R. A. (2005). Self-management in adolescents with chronic illness. What does it mean and how can it be achieved? Medical Journal of Australia, 138(8), 405–409.

Schomerus, G., Matchinger, H., & Angermeyer, M. C. (2009). The stigma of psychiatric treatment and help-seeking intentions for depression. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 259(5), 298–306.

Scott, J., & Pope, M. (2002). Nonadherence with mood stabilizers: Prevalence and predictors. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 63(5), 384–390.

Stiffman, A. R., Horwitz, S. M., & Hoagwood, K. (2000). The Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (SACA): Adult and child reports. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39, 1032–1039.

Tamres, L. K., Janicki, D., & Helgeson, V. S. (2002). Differences in coping behavior: A meta- analytic review and an examination of relative coping. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 6(1), 2–30.

Teplin, L. A., Abram, K. M., McClelland, G. M., Dulcan, M., & Mericle, A. A. (2002). Psychiatric disorders in youth in juvenile detention. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59, 1133–1143.

United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2008). Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) Report: Preliminary FY 2006 Estimates as of January 2008 (14). Washington DC: Administration for Children and Families, Children’s Bureau.

Wang, P. S., Berglund, P. A., Olfson, M., Pincus, H., Wells, K., & Kessler, R. C. (2005). Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 603–613.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Munson, M.R., Narendorf, S.C. & McMillen, J.C. Knowledge of and Attitudes Towards Behavioral Health Services Among Older Youth in the Foster Care System. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 28, 97–112 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-010-0223-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-010-0223-8