Abstract

The influence of severe emotional and behavioral disorders in youth on their parents is a complex, yet understudied topic. There is a dearth of literature in which the experiences of parents of youth who access intensive mental health treatment have been reported. The purpose of this study was to explore parents’ self-reported sense of competence in relation to their relationship status and in relation to the severity of their children’s symptoms. Data for this report were collected in a larger study on the psychosocial outcomes of youth accessing residential or intensive home-based treatment. In the current study, parental sense of competence was negatively associated with severity of internalizing and externalizing behaviors in children. Separated parents rated their parenting competence statistically significantly higher than divorced parents, though the practical significance of this finding is uncertain. Implications for social work research and practice are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recently, there has been a movement to offer youth and families accessing treatment for severe mental health problems care within their homes and local communities. These efforts are consistent with placing youth in a care setting with the lowest level of restrictive care possible that is clinically appropriate (Bilchik 2005; Stroul and Friedman 1996). Many youth may still require treatment in out-of-home settings such as residential treatment centers (RTC), foster care and psychiatric in-patient units due to the level of severity, and the impact of these mental health problems on functioning within the school, community, and family settings (Preyde et al. 2009). Home and community services may not suffice in meeting the therapeutic and clinical needs of these youth with severe emotional and behavioral disorders. Residential treatment centers (RTC) can serve as a valuable and important specialized treatment option for youth with moderate to severe emotional and behavioral disorders (Stroul and Friedman 1996). Similarly, RTC can be important for caregivers who feel that their youths’ behaviors have escalated such that they are no longer capable of managing such behaviors on their own (Tahhan et al. 2010). Many youth referred to RTC have not maintained long-term success after discharge from less restrictive therapeutic settings (Nickerson et al. 2007) which is usually attributed to the degree of severity and complexity of the challenges these youth experience (Dale et al. 2007). Researchers have shown that for youth accessing intensive mental health treatment these disorders are not isolated to a specific mental health disorder, but a range of problems that include a multitude of mental health disorders. Connor et al. (2004)reported that most youth (92 % in this sample of 397) had more than one diagnosis and over 50 % had three or four diagnoses. These findings highlight the significant mental health needs for this population.

Residential treatment centers offer a range of therapeutic interventions to youth with severe emotional and behavioral problems that necessitate 24-h care in an out-of-home placement (Abt Associates 2008). Much of the research on youth in RTC has been focused on outcomes for youth after discharge (e.g., Preyde et al. 2011a, b, c; Sunseri 2004; Robst et al. 2014; Thomson et al. 2011). Although this research is of considerable relevance, there are many critical issues concerning youth who are referred to RTC that have not received much attention including characteristics of the families of these vulnerable youth (Wells 1991). Equally important, few investigators have explored characteristics of the parents of these youth. Extant literature on this population has suggested that youth who are referred to RTC are likely to have experienced poverty in their family home (Preyde et al. 2012; Wells and Whittington 1993), and have parents who have experienced mental health problems (Baker et al. 2005; Dale et al. 2007; Griffith et al. 2009), engaged in alcohol abuse, experienced domestically violent relationships, or experienced incarceration (Child Welfare League of America [CWLA] 2005; Connor et al. 2004). There is a dearth of research that has been focused on the experiences and perceptions of parents who have youth accessing intensive mental health treatment (see Tahhan et al. 2010 for an exception). Therefore, the goal of the current study was to explore how parents with youth accessing intensive mental health treatment in a RTC or a home-based treatment (HBT) option rate their competence in their role as parents, and to explore the relationship between the severity of emotional and behavioral problems in youth, family functioning, quality of life with arental sense of competence.

Theory: Self-Efficacy

Bandura’s (1997) theory of self-efficacy can aid in the explanation of the development of parental competence for parents of youth experiencing severe emotional and behavioral disorders. Based on self-efficacy theory, individuals develop beliefs about their ability to successfully complete certain tasks or behaviors based on past experiences and feedback from others (Bandura 1997). These beliefs may affect choices made by the individual such as whether to engage in an activity, how much effort to expend in the activity, as well as how perseverant he or she will be in the face of adversity in the activity (Bandura 1997). In addition, efficacy plays an important role when considering how satisfied one feels in a task. A strong influence on self-efficacy is previous performance. Parents who feel successful in parenting may be more likely to feel as though they have the capacity to be competent parents. In relation to severe emotional and behavioral problems, parents who have successfully managed problems experienced by their children may feel more confidence in their ability to do so in the future and vice versa.

Role of Parental Sense of Competence

Ohan et al. (2000) suggested that parental sense of competence is comprised of two attributes: one’s perception of his or her ability to be effective as a parent and one’s satisfaction or contentment with parenting. Several factors may influence a parent’s ability to establish and maintain competence. These barriers include a lack of knowledge about parenting (Sanders et al. 2000), a lack of access to social support to get advice on parenting, and a lack of support from a partner in the process of parenting (Lawton and Sanders 1994). Furthermore, several contextual variables have been identified as potential barriers to establishing competence such as socioeconomic status as well as the community in which the family resides (Jones and Prinz 2005). Lastly, it has been suggested that severe emotional and behavioral disorders in children (e.g. attention deficit hyperactive disorder, oppositional defiant disorder) may also prevent parents from establishing positive feelings about their ability to parent successfully (Jones and Prinz 2005). The exact relationship between the bi-directional influences which result in specific perceptions, behaviors or disorders is unclear. Jones and Prinz (2005) suggested that parental competence has been viewed by scholars as a(n) “antecedent, a consequence, a mediator, and a transactional variable” (p. 342). Some progress has been made for specific family contexts. For example, it is well documented that symptoms of depression can impact parenting practices and the development of emotional and behavioral problems in youth (Cummings et al. 2005; Gordon et al. 1989; Weissman et al. 1997). Complex interactions exist between parents’ mood and child adjustment problems (Elgar et al. 2003, 2004) and what precipitates and perpetuates mental health problems (Dwyer et al. 2003). A parent with depressive symptomatology may experience challenges in the role of parent. Specifically, parents who feel helpless or worthless, symptoms commonly associated with depression, may struggle to feel effective (Weaver et al. 2008). When considering the role of efficacy and satisfaction in parents’ sense of competence, one must consider how the specific beliefs created by a parent about his or her ability to parent a child may impact these two domains.

Emotional and Behavioral Problems and Parental Competence

For youth in RTC the most common diagnoses are disruptive behavioral disorders, affective and anxiety disorders, and psychotic disorders (Connor et al. 2004; Jewell and Stark 2003). The relationship between emotional and behavioral problems of children and familial relationships in these vulnerable youth is complex. Mental health problems can affect youths’ functioning within their school, home, and community systems. The relationship between youths’ problem behaviors and parental sense of competence is unclear. Do parents who perceive themselves as competent engender positive behaviors from their children, or do positive behaviors in children enhance sense of competence in their parents? Similarly, it is unclear if parents who have less competence lack skills necessary to manage emotional and behavioral problems or disturbances in their children, or if emotional and behavioral problems lead parents to feel less competent. Although the nature of this relationship is complex, it is likely that parental competence and emotional and behavioral problems experienced by youth influence one another (Eccles et al. 1993).

Parental Sense of Competence and Family Environment in Clinical Samples of Youth

The family environment, quality of life, and family dynamics can all influence a parent’s sense of competence and satisfaction in the role of parent. Furthermore, children’s mental health problems, particularly disruptive or deviant behaviors, can affect the family environment, particularly relationships and a parent’s sense of competence (Patterson et al. 1992). Parents of youth accessing intensive mental health treatment have reported that their children’s mental health problems negatively affected family relationships and were a source of anxiety for many parents (Preyde et al. 2011a, b, c). Similarly, through a longitudinal study, Slagt et al. (2012) reported a relationship between externalizing problem behaviors of children and lower parental sense of competence when these children were adolescents. For mothers, this relationship was mediated by inept disciplinary practices. However, parental reports of perceived parental competence were not found to predict externalizing problem behaviors at a later time. Conversely, in a comparison of clinical to normative child samples, Sanders and Woolley (2005) found that mothers with children with conduct disorder felt less confident in their abilities to manage their children’s behaviors than mothers with normative children. Furthermore, Tahhan et al. (2010) indicated that mothers of youth who accessed RTC reported feeling as though they did not have the skills or knowledge to manage their children’s behaviors, and reaching a “breaking point” with their children. In addition, mothers reported that despite their best efforts to control or manage their children’s behaviors, the emotional and behavioral problems still seemed to be escalating. These mothers reported a desire to be able to understand their children’s behavior better so that they could help in times of distress as well as exhaustion which affected their relationships within their family, including spouses, but also within the community (Tahhan et al. 2010). Mothers also noted that their children were commonly violent with their siblings, and they reported that after their children were placed in RTC, they were more available to their other children (Tahhan et al. 2010). Despite the interactions of child behavioral problems and spousal relationships, Tahhan et al. (2010) found that single mothers with children with behavioral problems experienced stress that was exacerbated by feeling as though they did not “have a break.” Not only were they managing the stress from having children with emotional and behavioral problems, they may also have been experiencing social isolation (Tahhan et al. 2010). Some parents, both single and partnered, have reported that the behavioral problems of their children created barriers to having support from other family members or friends, and prevented family and friends from wanting to come to the house or plan other activities with the family (Preyde et al. 2011a, b, c; Tahhan et al. 2010). These studies offer insight into the challenges of raising children with severe emotional and behavioral problems, and the complex interactions of family variables and characteristics.

Based on findings from these studies, scholars should consider the extent of parental efficacy and satisfaction experienced by parents of youth who exhibit severe emotional and behavioral problems. If one considers his or her child a barrier to positive and intimate relationships, how does this individual find satisfaction in that role? Similarly, Coleman and Karraker (1998) suggested that the constructs of efficacy and satisfaction are highly related. They proposed attaining satisfaction may be difficult in a role in which he or she does not feel effective. The manner, in which these factors intertwine, highlights the bi-directional relationship between parental competence and behavioral problems. If parents perceive they lack necessary skills to parent their children’s problem behaviors, then what is the likelihood that they will find satisfaction in this role? Similarly, if parents feel “burnt out” and unavailable to their romantic partner, other children, relatives, or friends then how do they feel effective in this role? The purpose for the current study is not to further establish the direction of the relationship between emotional and behavioral problems and parental competence, rather the purpose is to expand the understanding of the relationship between emotional and behavioral problems in children and parental sense of competence by exploring the relationship between the severity of emotional and behavioral problems in youth and perceived parental sense of competence within the family context. Other variables that may influence the severity of child mental health problems and parental sense of competence are the relationship status (Belsky 1984; Tahhan et al. 2010) the number of children in the household (Tahhan et al. 2010), socioeconomic status (Lee et al. 2007), parental mental health (Cummings et al. 2005; Gordon et al., 1989; Weissman et al. 1997), family functioning (Kim et al. 2007) and family quality of life (Sawyer et al. 2002).

The Current Study

The purposes of this study were to explore differences between parents who are common-law, divorced, married, separated, or single with regard to parental sense of competence, and to explore the relationship between the severity of emotional and behavioral problems in youth and parental sense of competence. In relation to the first purpose, it was hypothesized that parents who were common-law or married would report a higher parental sense of competence because they may experience greater social support from a spouse. In relation to the second research question, we hypothesized that there would be a negative correlation between emotional and behavioral problems and perceived competence of parents. Specifically, it was hypothesized that a stronger correlation would exist between externalizing behaviors in children and parental sense of competence than between internalizing behaviors and parental sense of competence. This hypothesis was grounded in a study completed by Angold et al. (1998) in which it was demonstrated that externalizing or conduct problems may magnify the amount of stress experienced by a family relative to youth who suffer from anxiety or depression. In order to test the second hypothesis, family covariates were controlled in the analysis (i.e., relationship status, number of children in the household, socioeconomic status (as measured by salary), parental depression, family functioning and family quality of life) to explore the relationship between symptom severity in children and parental sense of competence.

Method

Participants

For this report we used data gathered in an observational, longitudinal study conducted between 2004 and 2007. Participants for the original study were recruited from five mental health facilities in Ontario, Canada. Three of the agencies served youth between the ages of 5 and 12 years, the additional two agencies offered services to adolescents between the ages of 12 and 16 years. Two strategies were utilized to recruit participants. In the first strategy, children, adolescents and their families who had been discharged from the five agencies within the previous 12–18 months were asked to join the study. In order to yield a larger sample, a second strategy in which all youth and their families entering the five agencies over the course of a year were recruited. This sample is comprised of youth who accessed RTC or home-based treatment (HBT). The RTC offered care and services to children, adolescents, and their families through multi-disciplinary teams who developed treatment plans that included cognitive-behavioral and brief and solution focused therapy as well as psycho-education. Treatment plans were developed to meet the individualized needs of the child or adolescent and his or her family. The youth whose families accessed HBT for treatments were experiencing similar difficulties with their children as families whose children were placed in RTC. The HBT programs offered therapeutic services very similar to the therapeutic services offered to the families with children in RTC; however, these services were offered to families within their homes. Approximately 55 % of youth accessing RTC and 3 % of youth accessing HBT were not living with their families at the time of data collection, thus measures were completed by their legal guardian (workers from Children’s Aid Society). These youth were excluded from the present analyses; only youth whose caregiver was their parent who completed the measures were included in the analyses.

Measures

Emotional and Behavioral Disorders

Adolescent mental health was measured using the Brief Child and Family Phone Interview (BCFPI-3; Cunningham et al. 2006). The BCFPI-3 is a semi-structured, standardized interview that is used to assess symptom severity. The interview is typically administered by phone with a parent or primary caregiver, but it can also be completed face-to-face. The measure includes seven subscales: regulation of attention, impulsivity, and activity level (RAIA); cooperation (CO); conduct (CD); separation from parents (SP); managing anxiety (MA); managing mood (MM); and self-harm (SH). Each of the seven subscales has acceptable reliability (α ranging from 0.75 to 0.83) with the exception of the CD subscale (α = 0.56). The 18-item externalizing behavior scale is comprised of the RAIA subscale (6 items), CO subscale (6 items), and CD subscale (6 items). The 18-item internalizing behavior scale is comprised of the SP subscale (6 items), MA subscale (6 items), and MM subscale (6 items) (Cunningham et al. 2006)). In the current study, all of the subscales had acceptable reliability (α ranges from 0.65 to 0.87). Within this sample the reliability on the conduct subscale was acceptable (α = 0.65).

The BCFPI-3 is administered by an intake worker who has formal training in children’s mental health and who has completed an approved Brief Child and Phone Interview training program. First, the interviewer asks about any general concerns. Based on the concerns presented by the caregiver, the intake worker selects the subscale which corresponds to the caregiver’s concern. The manual for the BCFPI-3 offers the intake worker suggested starting points based on the presented concerns. The intake worker asks questions from each subscale even if the caregiver does not report concerns related to the subscale. For the current study, two specific measures were used, the externalizing behavior scale and the internalizing behavior scale. The Total Composite Problem Scores (t scores) were generated for the externalizing behavior scale and the internalizing behavior scale. A t score greater than 70 on a subscale indicated a significant behavioral problem (Cunningham et al. 2006).

Parental Depression

Within the BCFPI-3 are six questions from the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D) (Radloff 1977). This six-question scale was created with permission from the CES-D. The revised version of the scale was also utilized in the OCHS-R. Within the OCHS-R sample, the revised measure had good internal consistency (α = 0.79). The questions were utilized to assess the extent to which the parent experienced a lack of appetite, trouble sleeping, and depressed moods during the past week. Sample items include “You felt depressed” and “You did not feel like eating; your appetite was poor.” This version of the CES-D utilized a four point Likert-type scale, ranging from less than 1 day last week (1), 1–2 days last week (2), 3–4 days last week (3), or 5 or more days last week (4). Higher scores indicate more severe depression. Cronbach’s alpha for the six question scale used with this sample was good (α = 0.86).

Parental Sense of Competence

Perception of parental competence was measured with the Parenting Sense of Competence (PSOC) Scale which is the most frequently used measurement to assess self-efficacy in parents (Jones and Prinz 2005). In the current study, a 12-item revised version of the Parenting Sense of Competence Scale was utilized. Parents were asked to respond to questions that assessed the extent to which they agreed with statements about being a parent on a 7 point scale (1 = strongly agree to 7 = strong disagree). For the purpose of the current study, means scores were utilized. Higher scores reflect higher sense of competence. Within this sample, the reliability on the scale was acceptable (α = 0.76).

Family Environment

Family environment was assessed with the 12-item General Functioning Scale of the Family Assessment Device (FAD; Byles et al. 1988) which is used to measure overall health/pathology. A higher score indicates higher pathological functioning. The parent version of the KINDL Quality of Life Questionnaire (Ravens-Sieberer and Bullinger 1998) was used to measure family quality of life. A higher score indicates higher health-related quality of life. Within this sample, the reliability on the scale was acceptable (α = 0.575).

Analytic Strategy

Differences in parental competence by relationship status were explored with a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The assumptions of independence of observations and homogeneity of variance and covariance were met. One parent was not included in the study because this parent was the only widow who was present at admission. The relationship between emotional and behavioral problems in youth and parental competence was explored with hierarchical linear regression (Leech et al. 2008). Hierarchical regression can be utilized to explore how independent variables, in this study externalizing behaviors, internalizing behaviors, as well as total mental health problems, are related to a dependent variable, which in this study is the parental sense of competence. This approach allowed us to control for potential covariates: socioeconomic status (as measured by salary), number of children in the household, parental depression, family functioning and family quality of life. Assumptions of linearity, normally distributed errors, and uncorrelated errors were met.

Results

The sample for the original, longitudinal study included 210 youth. Of these total participants, 150 had a parent who was present at admission (70 %). For 60 youth the intake was completed by a guardian other than their parent (e.g., CAS worker) and were thus not appropriate for these analyses. Of these youth 101 (67 %) participants accessed HBT and 49 (33 %) participants accessed RTC. Participant characteristics are presented in Tables 1 and 2. To verify if the children and adolescents accessing RTC differed from the children and adolescents accessing HBT on demographic variables, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Fisher’s Exact Test statistics were utilized. First, differences in demographic variables (salary, relationship status, gender) were assessed through ANOVA (salary) and Chi square (relationship status and source of income) Fisher’s Exact Test (gender) (see Table 2). Fisher’s Exact Test should be conducted instead of Chi square if there is a small sample size and/or if there is a relatively uneven split of participants among the levels of the nominal variables (Morgan et al. 2007). As mentioned above, a large majority of the children and adolescents were males, and the majority of parents were females, thus Fisher’s Exact Test was selected. Overall, the sample exhibited clinically significant problems (t score greater than 70) on externalizing behaviors and total mental health problems, and approaching clinical significance (t score = 69.09) for internalizing behaviors.

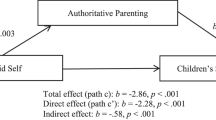

There were statistically significant differences in self-reports of parental competence by relationship status, [F(4, 144) = 2.41; p < 0.05]. Post hoc Tukey HSD Tests indicated that only parents who were separated (M = 4.78) perceived themselves as feeling more competent than parents who were divorced (M = 4.11; p < 0.05). There were no other differences in parental competence by family structure. As expected parental competence was negatively associated with severity of externalizing behaviors (higher parental sense of competence, lower externalizing behavior; r = −0.18, p = 0.05) and parental depression was associated with severity of internalizing behavior; r = 0.37, p = 0.02).

For the regression model, parental sense of competence did not significantly correlate with parental depression, and was only statistically different for parents who were separated or divorced; therefore, these variables were not included in the hierarchical regression analysis. The intercorrelations (Table 2) suggest that parental sense of competence was significantly correlated with externalizing behaviors, family functioning and quality of life, and a trend toward significance was evident for severity of internalizing behaviors. The overall model was statistically significant (F = 3.08, p = 0.007).

Discussion

Contrary to expectations, parents who indicated that they were separated rated their parental sense of competence higher than the divorced parents. One could speculate about the processes of separation and the completed divorce, and the influence on a parents’ self-reported competency in their role as parent. Further, there appears to be a relationship between parents’ self-report of competence and their report of the severity of their children`s externalizing behavior, and a trend toward significance with internalizing behaviors, when controlling for socioeconomic status and number of children in the household, family functioning and quality of life. Additionally, in the current study, parental depression was not significantly related to parental sense of competence but as expected, parental depression was associated with internalizing behavior.

Results from the current study did not confirm the hypothesis concerning family structure and parental competence. It was expected that parents who were in a partnered relationship, married or common-law, would report significantly higher sense of parental competence than parents who were single, separated, or divorced. Belsky (1984) noted that social support is positively related to a parent’s ability to engage in positive parenting behaviors. More specifically, he suggested that a positive couple relationship supports parental competence (Belsky 1981). Additionally, he proposed that positive emotional experiences that are not necessarily directly related to parenting such as feeling valued or validated by a romantic partner can have a positive impact on one’s ability to care for children. However, in the present study, these families with youth experiencing moderate to severe mental health disorders may be contending with multiple, complex challenges that affect the quality of relationships such as caregiver strain, burn out, or feelings of inadequacy. It is important to note that only relationship status, not the quality of these relationships, was examined. It may be that the quality of the relationship would mediate relationship status and parenting satisfaction. One possible explanation for parents who were married reporting among the lowest in terms of perceived competence is that despite being married, these parents did not experience satisfaction or support from their current relationships. It is also possible that some spouses had different opinions and practices about how to handle the complex problems experienced by their children which may have influenced their sense of competence. This lack of satisfaction may directly affect the emotional well-being of parents as well as their feelings of effectiveness and satisfaction in parenting.

There was support for the second hypothesis; when controlling for family environmental variables, a significant (negative) relationship was found between the severity of emotional and behavioral disorder in youth, and their parents’ sense of competence in the parenting role. It is important for mental health professionals working with this population to understand the severity of mental health problems of these youth, the bi-directional influence of these disorders and their parents’ sense of competence, and the needs and perceptions of parents as they relate to their children’s mental health problems (Tables 3, 4).

Interestingly, results from the current study do not indicate a relationship between parental sense of competence and parental depression. As described above, the measure utilized to assess for depression was a six-item modified version of the CES-D which was imbedded within the BCFPI. The BCFPI was developed to assess symptom severity in children, not parents. The six questions were utilized to assess for somatic symptoms of depression such as lack of appetite, lack of sleep, or a lack of motivation in parents. This measure was not used to assess affective or interpersonal symptoms commonly associated with depression, which are assessed in the full CES-D, such as feeling hopeless about the future, feeling disliked, or feeling lonely. More importantly, it did not assess the cognitive symptoms, especially those automatic thoughts or core beliefs associated with the parenting role. In order to understand the implications of parental depression for youth who access intensive mental health treatment, in the future investigators should measure somatic and affective or interpersonal symptoms of depression.

Findings suggest a relationship between mental health problems in youth and parental competence. Parents who reported a greater degree of severity of mental health symptoms in their youth also reported a lower sense of parental competence. The development of mental health disorder in children may be difficult for parents to detect and isolate from other dynamics within the family. Many times mental health problems are identified by school personnel (Zwaanswijk et al. 2005). Furthermore, once identified, it can be difficult for parents to access mental health services for a variety of reasons (Sayal et al. 2010) including the appointment system, stigma, embarrassment, worry about being judged a poor parent or even worry of having their child apprehended. Parents of these youth may benefit from education, intervention, training or access to other resources to learn how to manage their children’s emotional or behavioral problems. Furthermore, the strength of the evidence for the long-term effectiveness of parenting programs for improved child outcomes (Thomas and Zimmer-Gembeck 2007) and improved parents’ self-efficacy (Hautmann et al. 2009) appears weak to moderate. Offering parent education while the youth resides in a RTC may be optimal, and group settings may also provide parents with social and peer support (Harr et al. 2011). Families may benefit from mental health services for parents and transitional support when the youth returns home. Improving mental health literacy such as learning how to navigate the various systems (mental health, school, etc.) may provide tremendous support for families, and help parents become informed partners in the therapeutic support of their children.

Parents own history of adverse conditions have been shown to have an enormous impact on the family environment including their parenting behaviors and their confidence in their parenting practices (Hashima and Amato 1994; Levendosky and Graham-Bermann 2001; Repetti et al. 2002). In particular, parents may have experienced family violence, including child maltreatment during their formative years, or spousal violence, that can considerably influence their thoughts, perceptions and behaviors during family interactions. Research has shown that parenting in the context of poverty can lead some parents to use unsupportive and punitive parenting practices and can influence perceptions of behaviors (Hashima and Amato 1994). There was an attempt to control for socioeconomic status in the present study; however, a more robust indicator may yield different results. Of great importance is the notion that emotional and behavioral symptoms, and perceptions of the self and other are heavily influenced by the context in which the individual is developing (Bronfenbrenner 1977).

Limitations

The findings of the present study should be interpreted with a view to its limitations. Primarily, the sample size of youth whose parents were their legal guardian at the time of accessing intensive mental health treatment was relatively small. Although this study includes a small sample, Mordock (1994) proposed that there is not a “typical residential child,” and rather than using research to try and identify one, we should utilize research to understand the experiences of these youth. Although in the current study only 149 youth were included, the goal of the study was to better understand the experiences of these youth and their parents. It is important to note that although the study included both mothers and fathers, the majority of the sample (94 %), were mothers; thus, differences between mothers and fathers were not explored. It is unclear if mothers and fathers experience and feel influenced by their children’s emotional and behavioral problems in a similar fashion. Additionally, cross-sectional data were utilized for this study thus permitting a focus on factors that are associated with parental sense of competence of youth accessing intensive mental health treatment, and not factors that predict this construct. Lastly, the quality of the couple relationship and parents’ affective depressive cognitions were not assessed which may have had important influences on parental sense of competence. It is suggested that in the future researchers explore the quality of the spousal and/or romantic relationships as well as family relationships, specifically, parent–child relationships as well as complete a full assessment of parental depression and family history.

Conclusion

Parents’ self-report of their sense of parental competence was associated with their reports of their children’s symptom severity. When a child has a mental health disorder, it is a family affair in that the whole family is often affected. What are the potential implications of feeling ineffective or unsatisfied in one’s role as a parent? Can feeling ineffective or unsatisfied exacerbate mental health problems which deepen these feelings experienced by the parent? However, when a child has a mental health disorder, it may also be conceived of as a community responsibility, a cross sector need to collaborate and support families and youth. This study reinforces efforts to engage parents and family members in the treatment of mental illness. It also reinforces research efforts to widen the scope of investigation to include the quality of the family relationships and other factors affecting parents (e.g., clinical depression, financial stress) of children with mental health disorder.

References

Abt Associates. (2008). Characteristics of residential treatment for children and youth with serious emotional disturbances. Retrieved from: http://www.naphs.org/documents/AbtFINALReport.8.4.08_000.pdf. Accessed 20 Jan 2014.

Angold, A., Messer, S. C., Stangl, D., Farmer, E. M., Costello, E. J., & Burns, B. J. (1998). Perceived parental burden and service use for child and adolescent psychiatric disorders. American Journal of Public Health, 88, 75–80.

Baker, A. J. L., Wulczyn, F., & Dale, N. (2005). Covariates of length of stay in residential treatment. Child Welfare: Journal of Policy, Practice, and Program, 84, 363–386.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise in control. New York: Freeman.

Belsky, J. (1981). Early human experience: A family perspective. Developmental Psychology, 17, 3–23.

Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55, 83–96.

Bilchik, S. (2005). Residential treatment: Finding the appropriate level of care. Residential Group Care Quarterly, 6, 1–11.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 52, 513–531.

Byles, J., Byrne, C., Boyle, M. H., & Offord, D. R. (1988). Ontario Child Health Study: Reliability and validity of the general functioning subscale of the McMaster Family Assessment Device. Family Process, 27, 97–104.

Child Welfare League of America. (2005). The Odyssey Project: A descriptive and prospective study of children and youth in residential group care and therapeutic foster care. Washington, DC: Author.

Coleman, P. K., & Karraker, K. H. (1998). Self-efficacy and parenting quality: Findings and future applications. Developmental Review, 18, 47–85.

Connor, D. F., Doerfler, L. A., Toscano, P. F., Volungis, A. M., & Steingard, R. J. (2004). Characteristics of children and adolescents admitted to a residential treatment center. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 13, 497–510.

Cummings, E. M., Keller, P. S., & Davies, P. T. (2005). Towards a family process model of maternal and paternal depressive symptoms: Exploring multiple relations with child and family functioning. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 479–489. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00368.x.

Cunningham, C. E., Pettingill, P., Boyle, M. (2006). The brief child and family phone interview (BCFPI-3) a computerized intake and outcome assessment tool. Interviewers Manual. Hamilton, ON: Offord Centre for Child Studies.

Dale, N., Baker, A. J. L., Anastasio, E., & Purcell, J. (2007). Characteristics of children in residential treatment in New York state. Child Welfare: Journal of Policy, Practice, and Program, 86, 5–27.

Dwyer, S. B., Nicholson, J. M., & Battistutta, D. (2003). Population level assessment of the family risk factors related to the onset or persistence of children’s mental health problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 44, 699–711.

Eccles, J. S., Midgley, C., Wigfield, A., Buchanan, C. M., Reuman, D., Flanagan, C., & MacIver, D. (1993). Development during adolescence: The impact of stage-environment fit on young adolescents’ experiences in schools and in families. American Psychologist, 48, 90–101.

Elgar, F. J., Curtis, L. J., McGrath, P., Waschbusch, D. A., & Stewart, S. H. (2003). Antecedent-consequence conditions in maternal mood and child adjustment: A four-year cross-lagged study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32, 362–374.

Elgar, F. J., McGrath, P., Waschbusch, D. A., Stewart, S. H., & Curtis, L. J. (2004). Mutual influences on maternal depression and child adjustment problems. Clinical Psychology Review, 24, 441–459.

Gordon, D., Burge, D., Hammen, C., & Adrian, C. (1989). Observations of interactions of depressed women with their children. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 146, 50–55.

Griffith, A. K., Ingram, S. D., Barth, R. P., Trout, A. L., Hurley, K. D., Thompson, R. W., & Epstein, M. H. (2009). The family characteristics of youth entering a residential care program. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 26, 135–150.

Harr, C., Horn-Johnson, T., Williams, N., & DeJager, L. (2011). The impact of family stressors on the social development of adolescents admitted to a residential treatment facility. Journal of Family Strengths, 11, 1–20.

Hashima, P. Y., & Amato, P. R. (1994). Poverty, social support, and parental behavior. Child Development, 65, 394–403.

Hautmann, C., Hoijtink, H., Eichelberger, I., Hanisch, C., Plück, J., Walter, D., & Döpfner, M. (2009). One-year follow-up of a parent management training for children with externalizing behaviour problems in the real world. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 37, 379–396.

Jewell, J. D., & Stark, K. D. (2003). Comparing the family environments of adolescents with conduct disorder or depression. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 12, 77–89.

Jones, T. L., & Prinz, R. J. (2005). Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 25, 341–363.

Kim, H. H., Viner-Brown, S. I., & Garcia, J. (2007). Children’s mental health and family functioning in Rhode Island. Pediatrics, 119(Suppl 1), S22–S28.

Lawton, J. M., & Sanders, M. R. (1994). Designing effective behavioural family interventions for stepfamilies. Clinical Psychology Review, 14, 463–496.

Lee, M., Chen, Y., Wang, H., & Chen, D. (2007). Parenting stress and related factors in parents of children with tourette syndrome. The Journal of Nursing Research, 15, 165–174.

Leech, N. L., Barrett, K. C., & Morgan, G. A. (2008). SPSS for intermediate statistics: Use and interpretation (3rd ed.). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Levendosky, A. A., & Graham-Bermann, S. A. (2001). Parenting in battered women: The effects of domestic violence on women and their children. Journal of Family Violence, 16(2), 171–192.

Mordock, J. B. (1994). The search for an identity: A call for observational-inductive research methods in residential treatment. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 12, 1–23.

Morgan, G. A., Leech, N. L., Gloeckner, G. W., & Barrett, K. C. (2007). SPSS for introductory statistics: Use and interpretation (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Nickerson, A. B., Colby, S. A., Brooks, J. L., Rickert, J. M., & Salamone, F. J. (2007). Transitioning youth from residential treatment to the community: A preliminary investigation. Child & Youth Care Forum, 36, 73–86.

Ohan, J. L., Leung, D. W., & Johnston, C. (2000). The parenting sense of competence scale: Evidence of a stable factor structure and validity. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 32, 251–261.

Patterson, G. R., Reid, J. B., & Dishion, T. J. (1992). Antisocial boys. Eugene, OR: Castalia.

Preyde, M., Adams, G., Cameron, G., & Frensch, K. (2009). Outcomes of children participating in mental health residential and intensive family services: Preliminary findings. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 26, 1–20.

Preyde, M., Cameron, G., Frensch, K., & Adams, G. (2011a). Parent-child relationships and family functioning of children and youth discharged from residential mental health treatment or a home-based alternative. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 28, 55–74.

Preyde, M., Frensch, K., Cameron, G., Hazineh, L., & Riosa, P. B. (2011b). Mental health outcomes of children and youth accessing residential programs or a home-based alternative. Social Work in Mental Health, 9, 1–21.

Preyde, M., Frensch, K. M., Cameron, G., White, S., Penny, R., & Lazure, K. (2011c). Long term outcomes of children and youth accessing residential or intensive home-based treatment: Three year follow up. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 20, 660–668.

Preyde, M., Watkins, H., Carter, J., White, S., Lazure, K., Penney, R., et al. (2012). Self-harm in children and adolescents accessing residential or intensive home-based mental health services. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 21, 270–281.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401.

Ravens-Sieberer, U., & Bullinger, M. (1998). Assessing health related quality of life in chronically ill children with the German KINDL: First psychometric and content analytical results. Quality of Life Research, 7, 399–407.

Repetti, R. L., Taylor, S. E., & Seeman, T. E. (2002). Risky families: Family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychological Bulletin, 128(2), 330–366.

Robst, J., Rohrer, L., Dollard, N., & Armstrong, M. (2014). Family involvement in treatment among youth in residential facilities: Association with discharge to family-like setting and follow-up treatment. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 22, 1–7.

Sanders, M. R., Markie-Dadds, C., Tully, L., & Bor, B. (2000). The Triple P—Positive Parenting Program: A comparison of enhanced, standard and self-directed behavioural family intervention for parents of children with early onset conduct problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68, 624–640.

Sanders, M. R., & Woolley, M. L. (2005). The relationship between maternal self- efficacy and parenting practices: Implications for parent training. Child: Care Health & Development, 31, 65–73.

Sawyer, M. G., Whaites, L., Rey, J. M., Hazell, P. L., Graetz, B. W., & Baghurst, P. (2002). Health-related quality of life of children and adolescents with mental disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 530–537.

Sayal, K., Tischler, V., Coope, C., Robotham, S., Ashworth, M., Day, C., et al. (2010). Parental help-seeking in primary care for child and adolescent mental health concerns: Qualitative study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(6), 476–481.

Slagt, M., Dekovic, M., de Haan, A., van den Akker, A. L., & Prinzie, P. (2012). Longitudinal associations between mothers’ and fathers’ sense of competence and children’s externalizing problems: The mediating role of parenting. Developmental Psychology, 48, 1554–1562.

Stroul, B. A., & Friedman, R. M. (1996). The system of care concept and philosophy. In B. A. Stroul (Ed.), Children’s mental health: Creating systems of care in a changing society (pp. 3–21). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes.

Sunseri, P. A. (2004). Family functioning and residential treatment outcomes. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 22, 33–53.

Tahhan, J., St Pierre, J., Stewart, S. L., Leschied, A. W., & Cook, S. (2010). Families of children with serious emotional disorder: Maternal reports on the decision and impact of their child’s placement in residential treatment. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 27, 191–213.

Thomas, R., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2007). Behavioral outcomes of parent-child interaction therapy and Triple P-Positive Parenting Program: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35, 475–495.

Thomson, S., Hirshberg, D., & Qiao, J. (2011). Outcomes for adolescent girls after long-term residential treatment. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 28, 251–267.

Weaver, C. M., Shaw, D. S., Dishion, T. J., & Wilson, M. N. (2008). Parenting self-efficacy and problem behavior in children at high risk for early conduct problems: The mediating role of maternal depression. Infant Behavior & Development, 31, 594–605. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2008.07.006.

Weissman, M. M., Warner, V., Wickramaratne, P., Moreau, D., & Olfson, M. (1997). Offspring of depressed parents: 10 years later. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54, 932–940.

Wells, K. (1991). Placement of emotionally disturbed children in residential treatment: A review of placement criteria. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 61, 339–347.

Wells, K., & Whittington, D. (1993). Characteristics of youths referred to residential treatment: Implications for program design. Children and Youth Services Review, 25, 1–16.

Zwaanswijk, M., Van der Ende, J., Verhaak, P. F., Bensing, J. M., & Verhulst, F. C. (2005). Help-seeking for child psychopathology: Pathways to informal and professional services in the Netherlands. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 44, 1292–1300.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Preyde, M., VanDonge, C., Carter, J. et al. Parents of Youth in Intensive Mental Health Treatment: Associations Between Emotional and Behavioral Disorders and Parental Sense of Competence. Child Adolesc Soc Work J 32, 317–327 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-014-0375-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-014-0375-z