Abstract

Purpose

Compare medical expenditures among adults with statin-associated adverse effects (SAAE) and high statin adherence (HSA) following myocardial infarction (MI).

Methods

We analyzed expenditures in 2016 US dollars among Medicare beneficiaries with SAAE (n = 1741) and HSA (n = 55,567) who were ≥ 66 years of age and initiated moderate/high-intensity statins following an MI in 2007–2013. SAAE were identified through a claims-based algorithm, which included down-titrating statins and initiating ezetimibe, switching to ezetimibe monotherapy, having a rhabdomyolysis or antihyperlipidemic adverse event followed by statin down-titration or discontinuation, or switching between ≥ 3 statin types within 365 days following MI. HSA was defined by having a statin available to take for ≥ 80% of the days in the 365 days following MI.

Results

Expenditures among beneficiaries with SAAE and HSA were $40,776 (95% CI $38,329–$43,223) and $26,728 ($26,482–$26,974), respectively, in the 365 days following MI, and $34,238 ($31,396–$37,080) and $29,053 ($28,605–$29,500), respectively, for every year after the first 365 days. Multivariable-adjusted ratios comparing expenditures among beneficiaries with SAAE versus HSA in the first 365 days and after the first 365 days following MI were 1.51 (95% CI 1.43–1.59) and 1.23 (1.12–1.34), respectively. Inpatient and outpatient expenditures were higher among beneficiaries with SAAE versus HSA during and after the first 365 days following MI. Compared to beneficiaries with HSA, medication expenditures among those with SAAE were similar in the 365 days following MI, but higher afterwards. Other medical expenditures were higher among beneficiaries with SAAE versus HSA.

Conclusion

SAAE are associated with increased expenditures following MI compared with HSA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Statins reduce the risk for cardiovascular events by 20% to 30% following a myocardial infarction (MI) [1, 2]. While statins are generally well tolerated, some patients have statin-associated adverse effects (SAAE), including musculoskeletal and hepatobiliary disorders [3]. Having SAAE often leads to treatment discontinuation, down-titration, or low adherence [4, 5]. In a previous study of older adults discharged from the hospital following an MI, having SAAE was associated with a higher risk for a recurrent coronary heart disease hospitalization compared with high statin adherence [6].

The increased risk for coronary heart disease events and other clinical manifestations associated with SAAE may result in additional healthcare services utilization and high medical expenditures. The estimation of these expenditures could provide evidence to support interventions to reduce the risk for coronary heart disease events and associated costs among patients with SAAE.

The objective of the current analysis was to estimate medical expenditures among Medicare beneficiaries with SAAE following initiation of statin therapy after an MI. We also compared expenditures among beneficiaries with SAAE to their counterparts with high statin adherence following an MI. Low statin adherence and statin discontinuation have also been associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease events and higher medical expenditures compared to high statin adherence [7,8,9,10,11]. As a secondary analysis, we compared medical expenditures among Medicare beneficiaries with SAAE and those with low statin adherence and who discontinued statin therapy following MI.

Methods

Study Population

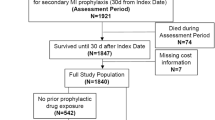

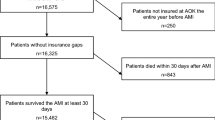

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of Medicare beneficiaries ≥ 66 years of age with an MI hospitalization between January 1, 2007, and December 31, 2013, as defined by an inpatient claim with an International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9) diagnosis code of 410.×1 or 410.×0 in any discharge diagnosis position (n = 1,049,736) [12]. We restricted the analysis to beneficiaries with continuous Medicare coverage for Parts A (inpatient), B (outpatient), and D (pharmacy) without Medicare Part C (managed healthcare) coverage for the 365 days prior to their MI (i.e., the “look-back” period), and for at least 365 days post-MI. Medicare beneficiaries with part C coverage were excluded because there is no requirement for submitting claims for most services received by these patients. We further restricted the analysis to beneficiaries whose first statin fill within 30 days following MI was for a high- or moderate-intensity dosage. Beneficiaries taking a statin prior to their MI may be less likely to have SAAE as they have demonstrated tolerance to treatment. In contrast, those taking niacin, a fibrate, a bile acid sequestrant, or ezetimibe prior to their MI may be more likely to have SAAE as this may be an indication for using these medications. Therefore, we excluded beneficiaries who filled any of these medications during the look-back period. The analysis was lastly restricted to beneficiaries living in the USA and without hospice care during the look-back period and the 365 days following MI. The final study population consisted of 105,329 Medicare beneficiaries (Supplemental Figure 1). For beneficiaries with multiple MIs meeting the criteria above, the first event (i.e., the index MI) was analyzed. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services approved the study.

Statin-Associated Adverse Effects, Statin Discontinuation, and Adherence to Statins

We identified pharmacy claims for a statin in the first 365 days following the index MI (Fig. 1) and defined the statin intensity as shown in Supplemental Table 1 [1]. We used a previously published claims-based algorithm to identify beneficiaries with SAAE in the first 365 days following the index MI [13]. This algorithm is based on a combination of diagnosis codes for adverse events associated with statin therapy and patterns of medication use consistent with recommendations for the management of patients with SAAE in clinical practice guidelines [1, 14,15,16]. Specifically, the primary definition of SAAE included any of the following components:

-

1.

Statin discontinuation and initiation of ezetimibe.

-

2.

Initiation of ezetimibe within 7 days before or any time after down-titrating statin intensity.

-

3.

An inpatient, outpatient, or carrier claim for rhabdomyolysis (defined by an ICD-9 diagnosis code 728.88 in any position) followed by statin down-titration or discontinuation.

-

4.

An inpatient, outpatient, or carrier claim for “adverse effect of an antihyperlipidemic agent” (defined by an ICD-9 diagnosis code E942.2 in any position) followed by statin down-titration or discontinuation.

-

5.

Fills for three or more statin types.

Schematic of the study design. MI, myocardial infarction; SAAE, statin-associated adverse effects. The symbol × indicates a statin fill for a moderate- or high-intensity dosage within 30 days post-discharge for the index MI hospitalization. Superscript letter “a” indicates that we used all available claims prior to the index MI to define a history of diabetes, chronic kidney disease, stroke, and heart failure (see Supplemental Table 2) and to calculate the Charlson comorbidity index

Patients with SAAE may down-titrate their statin intensity without initiating ezetimibe or having a diagnosis of rhabdomyolysis or an “adverse effect of an antihyperlipidemic agent.” Therefore, the secondary definition of SAAE included any component of the primary definition or statin down-titration (i.e., titrating from a high- to moderate- or moderate- to low-intensity statin) [13]. Niacin, fibrates, and bile acid sequestrants can be used for lowering triglycerides in addition to lowering total and low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. Therefore, initiation of niacin, fibrates, or bile acid sequestrants is not considered indication of SAAE in the claims-based algorithm used for the current analyses [13].

Among beneficiaries without SAAE by the primary or secondary definition, statin discontinuation was defined as not having a day of statin supply available to take from day 186 through day 365 following the index MI. Among beneficiaries without SAAE or statin discontinuation, we calculated statin adherence using the interval-based proportion of days covered (PDC) method [17]. PDC was calculated as the number of days for which a patient had a statin available to take divided by the number of days between the first statin fill and day 365 following the index MI. Days spent in hospital did not contribute to the calculation of the PDC. High and low statin adherence were defined by a PDC ≥ 80% and < 80%, respectively [18].

Expenditures

We analyzed the total payment to providers, including the payment made by Medicare, the patient, and/or a co-insurance, in the initial 365 days following the index MI and after the first 365 days, separately. This was done because expenditures during the initial 365 days following the index MI may include healthcare services directly related to SAAE. Also, the risk for recurrent coronary events is lower after the initial 365 days following MI [19]. Inpatient expenditures were determined from claims for hospitalizations. Outpatient expenditures were determined from outpatient and carrier claims. Medication expenditures were determined using pharmacy claims. Other expenditures were determined using skilled nursing facility, hospice, durable medical equipment, and home healthcare agency claims. Total expenditures were calculated as the sum of inpatient, outpatient, medication, and other expenditures. Inpatient and outpatient expenditures linked to an ICD-9 diagnosis code of 390–459 or 745–747 in the primary diagnosis position were defined as being cardiovascular disease (CVD)-related [20]. Expenditures were adjusted to 2016 using the healthcare component of the consumer price index.

Patient Characteristics

We used Medicare beneficiary summary files to define age on the index MI admission date, sex, and race/ethnicity. All available claims prior to the index MI were used to determine a history of diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), stroke, and heart failure (Supplemental Table 2) and to calculate the Charlson comorbidity index [21]. We used pharmacy claims during the look-back period to identify beneficiaries taking antihypertensive medication. Low adherence to antihypertensive medication has been predictive of statin discontinuation and low statin adherence among patients initiating statin therapy following MI [22]. Therefore, we calculated the PDC for antihypertensive medication during the look-back period.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated characteristics of beneficiaries with SAAE by the primary definition and high statin adherence. Among beneficiaries with SAAE by the primary definition, we calculated the number and proportion who met each component of the definition.

We calculated means and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for total, inpatient (overall and CVD-related), outpatient (overall and CVD-related), medication, and other expenditures among beneficiaries with SAAE by the primary definition and with high statin adherence. All beneficiaries in the current analysis had follow-up for 365 days following their index MI. After day 365 post-MI, beneficiaries were followed through their death, loss of Medicare coverage for Part A, B, or D, initiation of Part C coverage, or January 1, 2015, whichever occurred first. To account for different follow-up times, expenditures after the first 365 days following the index MI were annualized (i.e., divided by the follow-up time, in years).

We used two-part regression models to calculate the absolute difference and the ratio of expenditures comparing beneficiaries with SAAE by the primary definition versus those with high statin adherence. The two-part regression models included a logistic regression model, which modeled the odds for having any expenditure, and a generalized linear model with a log link, which modeled the differences in expenditures among those with any expenditures. A gamma distribution was used for the generalized linear model to account for the skewness of expenditure data [23]. Models included adjustment for age, sex, race/ethnicity, history of diabetes, CKD, stroke and heart failure, Charlson comorbidity index, and antihypertensive medication use and PDC. We calculated the ratio of total expenditures comparing beneficiaries with SAAE by the primary definition versus those with high statin adherence within sub-groups defined by characteristics in the multivariable-adjusted model. The statistical significance for the difference in the ratios of expenditures across sub-groups was calculated by including interaction terms between each characteristic and the exposure group (e.g., male sex × SAAE versus high statin adherence).

In a sensitivity analysis, we compared total, inpatient (overall and CVD-related), outpatient (overall and CVD-related), medication, and other expenditures in the first 365 days and after the first 365 days following MI among beneficiaries with SAAE by the secondary definition versus those with high statin adherence. As a secondary analysis, we compared characteristics and expenditures among beneficiaries with SAAE by the primary definition versus those with low statin adherence and who discontinued statin therapy, separately. All analyses were conducted using STATA v. 13 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) and a two-sided level of statistical significance < 0.05.

Results

A total of 1741 beneficiaries had SAAE by the primary definition and 55,567 had high statin adherence (Fig. 2). Beneficiaries with SAAE by the primary definition were less likely to be ≥ 80 years of age and male, and have a history of CKD, stroke, and heart failure, and a Charlson comorbidity index ≥ 4 compared to beneficiaries with high statin adherence (Table 1). The main reason for meeting the primary definition of SAAE was having fills for three or more statin types in the 365 days following MI.

Expenditures Associated with SAAE and High Statin Adherence

The mean total expenditures among beneficiaries with SAAE and high statin adherence were $40,776 and $26,728, respectively, in the 365 days following MI, and $34,238 and $29,053, respectively, for every year after the first 365 days (Table 2). After multivariable adjustment, beneficiaries with SAAE had higher total, overall and CVD-related inpatient, overall and CVD-related outpatient, and other expenditures versus those with high statin adherence in the first 365 days and after the first 365 days following MI. Medication expenditures were not statistically significantly different among beneficiaries with SAAE and those with high statin adherence in the first 365 days following MI. After the first 365 days following MI, medication expenditures were higher among beneficiaries with SAAE versus those with high statin adherence.

Supplemental Tables 3 and 4 show total expenditures in the first 365 days and after the first 365 days following MI, respectively, among beneficiaries with SAAE and those with high statin adherence within sub-groups defined by patient characteristics. After multivariable adjustment, expenditures in the first 365 days following MI were higher among beneficiaries with SAAE versus those with high statin adherence in all sub-groups (Fig. 3). After the first 365 days, multivariable-adjusted expenditures were higher among beneficiaries with SAAE versus those with high statin adherence in all sub-groups, but the difference was not statistically significant among beneficiaries 75–79 years of age, those with a history of diabetes, CKD, and stroke, a Charlson comorbidity index of 1, and those taking antihypertensive medication with a PDC < 50% and 50 to < 80% (Fig. 4).

Multivariable-adjusted ratios of mean total expenditures within 365 days following hospital discharge for myocardial infarction comparing beneficiaries with SAAE versus those with high statin adherence in sub-groups. CKD, chronic kidney disease; SAAE, statin-associated adverse effects. Letter “a” indicates that the difference across sub-groups is statistically significant using an alpha level < 0.05. SAAE were defined using the primary definition (see the “Methods” section for details). All analyses include multivariable adjustment for age, sex, race/ethnicity, history of diabetes, CKD, stroke and heart failure, Charlson comorbidity index, antihypertensive medication use, and adherence to antihypertensive medication

Multivariable-adjusted ratios of mean total annual expenditures after the first 365 days following hospital discharge for myocardial infarction comparing beneficiaries with SAAE versus those with high statin adherence in sub-groups. CKD, chronic kidney disease; SAAE, statin-associated adverse effects. SAAE were defined using the primary definition (see the “Methods” section for details). All analyses include multivariable adjustment for age, sex, race/ethnicity, history of diabetes, CKD, stroke and heart failure, Charlson comorbidity index, antihypertensive medication use, and adherence to antihypertensive medication. None of the sub-group comparisons was statistically significant using an alpha level < 0.05

In the sensitivity analysis, beneficiaries with SAAE by the secondary definition had higher total, overall and CVD-related inpatient, overall and CVD-related outpatient, and other expenditures in the first 365 days and after the first 365 days following MI compared with those with high statin adherence (Supplemental Table 5). Medication expenditures in the first 365 days following MI were lower among beneficiaries with SAAE by the secondary definition versus those with high statin adherence. After the first 365 days, medication expenditures were not statistically significantly different among beneficiaries with SAAE by the secondary definition versus those with high statin adherence.

Comparison of SAAE Versus Low Statin Adherence and Statin Discontinuation

Beneficiaries with SAAE by the primary definition were more likely to be White and less likely to be ≥ 80 years of age and male, and have a history of CKD, stroke, and heart failure, and a Charlson comorbidity index ≥ 4 compared to beneficiaries with low statin adherence and who discontinued statin therapy (Supplemental Table 6). In the first 365 days following MI, beneficiaries with SAAE had higher total, overall and CVD-related inpatient, overall and CVD-related outpatient, and medication expenditures compared to those with low statin adherence and who discontinued statin therapy (Supplemental Table 7, top panel). Other expenditures among beneficiaries with SAAE were lower compared to beneficiaries with low statin adherence and not statistically significantly different versus those who discontinued statin therapy. After the first 365 days, total, overall and CVD-related inpatient, and overall outpatient expenditures were not statistically significantly different for beneficiaries with SAAE versus those with low statin adherence and who discontinued statin therapy (Supplemental Table 7, bottom panel). CVD-related outpatient expenditures among beneficiaries with SAAE were not statistically significantly different versus beneficiaries with low statin adherence and higher compared to those who discontinued statin therapy. Medication expenditures were higher for beneficiaries with SAAE compared to those with low statin adherence and who discontinued statin therapy. Other expenditures among beneficiaries with SAAE were not statistically significantly different versus beneficiaries with low statin adherence and lower compared to those who discontinued statin therapy.

Discussion

In the current study, Medicare beneficiaries initiating moderate- or high-intensity statin following an MI who had SAAE had higher total medical expenditures compared to their counterparts with high adherence to statin therapy. Higher medical expenditures among beneficiaries with SAAE versus those with high statin adherence were present during and after the first 365 days following MI. Results were consistent within a large number of sub-group analyses defined by patient characteristics.

Some patients have SAAE while taking statins [3, 5, 24]. In the Effect of Statins on Skeletal Muscle Function and Performance (STOMP) study, atorvastatin 80 mg doubled the risk for muscle problems compared with placebo, from 4.6 to 9.4% [25]. Patients with SAAE are less likely to meet their LDL cholesterol goal compared with those without SAAE [26]. Also, we have previously shown that Medicare beneficiaries who experienced SAAE following MI, as defined in the current analysis, had a 51% higher risk (hazard ratio 1.51, 95% CI 1.34, 1.70) for a recurrent coronary event compared to their counterparts with high statin adherence [6].

An analysis of patients ≥ 18 years of age in the Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania found that mean expenditures over a 24-month follow-up period was $8777 among patients with SAAE compared to $7344 among matched controls taking a statin without SAAE [26]. Results from the current study expand on prior research by showing that patients with SAAE have higher expenditures in the initial 365 days and after the first 365 days following MI versus their counterparts with high statin adherence. The higher medical expenditures among beneficiaries with SAAE versus those with high statin adherence in the current analysis was explained by higher inpatient, overall and CVD-related, outpatient, overall and CVD-related, and other expenditures. Medication also contributed to the higher medical expenditures among beneficiaries with SAAE versus those with high statin adherence after the initial 365 days following MI. This later finding may be explained by the use of multiple lipid-lowering drugs among beneficiaries with SAAE.

Beneficiaries with SAAE in the current analysis had higher medical expenditures in the 365 days following MI versus those with low statin adherence and who discontinued statin therapy. Medical expenditures comparing beneficiaries with SAAE versus those with low statin adherence and who discontinued statins were not statistically significantly different after the initial 365 days following MI. Prior studies have shown that low statin adherence and statin discontinuation are associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular events and higher medical expenditures compared to high statin adherence [7,8,9,10,11]. Therefore, results from the current study should not be interpreted as indicative that patients with SAAE may benefit from discontinuing statin therapy. The higher medical expenditures in the 365 days following MI among beneficiaries with SAAE versus those with low statin adherence and who discontinued statin therapy may be explained by a higher medication use and an increased healthcare services utilization directly related to the management of statin side effects.

Patients with SAAE should continue taking a statin whenever possible. Prior studies have shown that many patients who discontinue statins due to SAAE can be successfully re-challenged and remain on statin therapy with high adherence [3, 27,28,29]. Also, alternate day dosing of statin therapy could be an effective strategy to reduce LDL cholesterol among patients with SAAE who cannot tolerate daily dosing of their statin [30]. Patients with SAAE may also benefit from taking non-statin lipid-lowering medications to reduce their risk for cardiovascular events [31,32,33]. Ezetimibe has been found to be cost-effective compared with no treatment among patients with SAAE or contraindications for statin therapy who have a history of CVD and elevated LDL cholesterol levels [34]. Proprotein convertase subtilisin–kexin type 9 inhibition has been shown to be effective to reduce the risk for major cardiovascular events among adults with a history of CVD and LDL cholesterol ≥ 70 mg/dL [35]. The economic implications of SAAE demonstrated in the current study may encourage health systems to invest resources to re-challenge patients with statin side effects and to increase the use of non-statin lipid-lowering medications in this population.

The current study has several strengths, including a large sample size. Also, Medicare provides health insurance to more than 90% of all US adults ≥ 65 years of age and approximately two-thirds of beneficiaries have traditional fee-for-service coverage (i.e., are not in a managed healthcare program) [36, 37]. Therefore, the current results have high degree of generalizability to older US adults. The current study also has potential and known limitations. SAAE were identified using claims-based algorithms based on diagnosis codes for adverse events and patterns of medication use consistent with SAAE. However, some patients with SAAE may not have a diagnosis code for adverse events or modify their pattern of statin use. Also, some patients may have patterns of medication use consistent with SAAE without having SAAE, as for example if they switch between different statin types and dosages to reduce their medication costs. Statin use and adherence to statin therapy were also defined using pharmacy claims. Pharmacy claims only indicate whether a beneficiary filled a prescription, and not whether they took the medication. Also, Medicare pharmacy claims may not include all medications filled by beneficiaries. In a prior study, 15.8% of Medicare beneficiaries who self-reported taking a lipid-lowering medication and had a statin during a medication inventory did not have a claim for a statin prescription fill in the prior 120 days [38]. In the current analysis, we were not able to differentiate whether medical expenditures were directly related to SAAE versus other reasons (e.g., regular follow-up visits). A higher healthcare services utilization directly related to the management of statin side effects may contribute to explain the higher medical expenditures in the 365 days following MI among beneficiaries with SAAE versus those with low statin adherence and who discontinued statin therapy.

In conclusion, results from the current study suggest that patients with SAAE have higher medical expenditures compared to those with high statin adherence. Patients with SAAE also have higher medical expenditures compared with their counterparts with low statin adherence or who discontinued statin therapy during the initial 365 days post-MI. These results should encourage health systems to invest resources to re-challenge patients with SAAE and consider other therapies to reduce the risk for CVD events and lower medical expenditures in this population.

References

Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129:S1–45.

Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et al. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366:1267–78.

Zhang H, Plutzky J, Skentzos S, Morrison F, Mar P, Shubina M, et al. Discontinuation of statins in routine care settings: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:526–34.

Bruckert E, Hayem G, Dejager S, Yau C, Begaud B. Mild to moderate muscular symptoms with high-dosage statin therapy in hyperlipidemic patients--the PRIMO study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2005;19:403–14.

Wei MY, Ito MK, Cohen JD, Brinton EA, Jacobson TA. Predictors of statin adherence, switching, and discontinuation in the USAGE survey: understanding the use of statins in America and gaps in patient education. J Clin Lipidol. 2013;7:472–83.

Serban MC, Colantonio LD, Manthripragada AD, Monda KL, Bittner VA, Banach M, et al. Statin intolerance and risk of coronary heart events and all-cause mortality following myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:1386–95.

Bitton A, Choudhry NK, Matlin OS, Swanton K, Shrank WH. The impact of medication adherence on coronary artery disease costs and outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2013;126:357 e7–357 e27.

Aubert RE, Yao J, Xia F, Garavaglia SB. Is there a relationship between early statin compliance and a reduction in healthcare utilization? Am J Manag Care. 2010;16:459–66.

Pittman DG, Chen W, Bowlin SJ, Foody JM. Adherence to statins, subsequent healthcare costs, and cardiovascular hospitalizations. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:1662–6.

De Vera MA, Bhole V, Burns LC, Lacaille D. Impact of statin adherence on cardiovascular disease and mortality outcomes: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78:684–98.

Penning-van Beest FJ, Termorshuizen F, Goettsch WG, Klungel OH, Kastelein JJ, Herings RM. Adherence to evidence-based statin guidelines reduces the risk of hospitalizations for acute myocardial infarction by 40%: a cohort study. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:154–9.

Colantonio LD, Levitan EB, Yun H, Kilgore ML, Rhodes JD, Howard G, et al. Use of Medicare claims data for the identification of myocardial infarction: the Reasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study. Med Care. 2018;56:1051–9.

Colantonio LD, Kent ST, Huang L, Chen L, Monda KL, Serban MC, et al. Algorithms to identify statin intolerance in Medicare administrative claim data. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2016;30:525–33.

Arca M, Pigna G. Treating statin-intolerant patients. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2011;4:155–66.

Rosenson RS, Baker SK, Jacobson TA, Kopecky SL, Parker BA, The National Lipid Association’s Muscle Safety Expert P. An assessment by the Statin Muscle Safety Task Force: 2014 update. J Clin Lipidol. 2014;8:S58–71.

Rosenson RS, Baker S, Banach M, Borow KM, Braun LT, Bruckert E, et al. Optimizing cholesterol treatment in patients with muscle complaints. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1290–301.

Choudhry NK, Shrank WH, Levin RL, et al. Measuring concurrent adherence to multiple related medications. Am J Manag Care. 2009;15:457–64.

Karve S, Cleves MA, Helm M, Hudson TJ, West DS, Martin BC. Good and poor adherence: optimal cut-point for adherence measures using administrative claims data. Curr Med Res Opin. 2009;25:2303–10.

Smolina K, Wright FL, Rayner M, Goldacre MJ. Long-term survival and recurrence after acute myocardial infarction in England, 2004 to 2010. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:532–40.

Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;133:e38–e360.

Romano PS, Roos LL, Jollis JG. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative data: differing perspectives. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1075–9 discussion 1081-90.

Muntner P, Yun H, Sharma P, Delzell E, Kent ST, Kilgore ML, et al. Ability of low antihypertensive medication adherence to predict statin discontinuation and low statin adherence in patients initiating treatment after a coronary event. Am J Cardiol. 2014;114:826–31.

Aaron KJ, Colantonio LD, Deng L, Judd SE, Locher JL, Safford MM, et al. Cardiovascular health and healthcare utilization and expenditures among Medicare beneficiaries: the REasons for Geographic And Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e005106.

Evans MA, Golomb BA. Statin-associated adverse cognitive effects: survey results from 171 patients. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29:800–11.

Parker BA, Capizzi JA, Grimaldi AS, Clarkson PM, Cole SM, Keadle J, et al. Effect of statins on skeletal muscle function. Circulation. 2013;127:96–103.

Graham JH, Sanchez RJ, Saseen JJ, Mallya UG, Panaccio MP, Evans MA. Clinical and economic consequences of statin intolerance in the United States: results from an integrated health system. J Clin Lipidol. 2017;11:70–79 e1.

Harris LJ, Thapa R, Brown M, Pabbathi S, Childress RD, Heimberg M, et al. Clinical and laboratory phenotype of patients experiencing statin intolerance attributable to myalgia. J Clin Lipidol. 2011;5:299–307.

Keating AJ, Campbell KB, Guyton JR. Intermittent nondaily dosing strategies in patients with previous statin-induced myopathy. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47:398–404.

Mampuya WM, Frid D, Rocco M, Huang J, Brennan DM, Hazen SL, et al. Treatment strategies in patients with statin intolerance: the Cleveland Clinic experience. Am Heart J. 2013;166:597–603.

Awad K, Mikhailidis DP, Toth PP, et al. Efficacy and safety of alternate-day versus daily dosing of statins: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2017;31:419–31.

Guyton JR, Bays HE, Grundy SM, Jacobson TA, The National Lipid Association Statin Intolerance Panel. An assessment by the Statin Intolerance Panel: 2014 update. J Clin Lipidol. 2014;8:S72–81.

Jacobson TA, Maki KC, Orringer CE, Jones PH, Kris-Etherton P, Sikand G, et al. National Lipid Association Recommendations for patient-centered management of dyslipidemia: part 2. J Clin Lipidol. 2015;9:S1–122 e1.

Lloyd-Jones DM, Morris PB, Ballantyne CM, et al. 2017 focused update of the 2016 ACC expert consensus decision pathway on the role of non-statin therapies for LDL-cholesterol lowering in the management of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology Task Force on expert consensus decision pathways. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70:1785–822.

Ara R, Pandor A, Tumur I, Paisley S, Duenas A, Williams R, et al. Cost effectiveness of ezetimibe in patients with cardiovascular disease and statin intolerance or contraindications: a Markov model. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2008;8:419–27.

Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, Honarpour N, Wiviott SD, Murphy SA, et al. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713–22.

Administration on Aging, Administration for Community Living, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. A profile of older Americans: 2016. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Administration on Aging; 2016. [Cited: October 10, 2017]; Available from: https://www.acl.gov/sites/default/files/Aging%20and%20Disability%20in%20America/2016-Profile.pdf

The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. An overview of Medicare. Issue brief. Menlo Park: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2017. [Cited: August 4, 2018]; Available from: http://files.kff.org/attachment/issue-brief-an-overview-of-medicare

Colantonio LD, Kent ST, Kilgore ML, Delzell E, Curtis JR, Howard G, et al. Agreement between Medicare pharmacy claims, self-report, and medication inventory for assessing lipid-lowering medication use. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2016;25:827–35.

Funding

The design and conduct of the study, interpretation of the results, and preparation of the manuscript were supported through a research grant from Amgen, Inc. (Thousand Oaks, CA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The academic authors conducted all analyses, drafted the manuscript, and maintained the rights to publish this article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

KLM, DJH, and JFM are employed by and stockholders of Amgen. PM receives research support from Amgen. MEF and MLK receive research support from Amgen. RSR receives research support from Akcea, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Medicines Company, and Regeneron; is an Advisory Board member/consultant for C5, CVS Caremark, Regeneron, and Sanofi; receives honoraria from Akcea, Amgen, Kowa, and Pfizer; is a stockholder of MediMergent; and receives royalties from UpToDate. LDC, LD, and LC have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in the current student were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services approved the study.

Informed Consent

This is a retrospective cohort study and formal consent was not required.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 83 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Colantonio, L.D., Deng, L., Chen, L. et al. Medical Expenditures Among Medicare Beneficiaries with Statin-Associated Adverse Effects Following Myocardial Infarction. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 32, 601–610 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10557-018-6840-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10557-018-6840-8