Abstract

Purpose

Although overall there is a positive association between obesity and risk of prostate cancer (PrCa) recurrence, results of individual studies are somewhat inconsistent. We investigated whether the failure to exclude diabetics in prior studies could have increased the likelihood of conflicting results.

Methods

A total of 610 PrCa patients who underwent radical prostatectomy between 2005 and 2012 were followed for recurrence, defined as a rise in serum PSA ≥ 0.2 ng/ml following surgery. Body mass index (BMI) and history of type 2 diabetes were documented prior to PrCa surgery. The analysis was conducted using Cox proportional hazard models.

Results

Obesity (25.6 %) and diabetes (18.7 %) were common in this cohort. There were 87 (14.3 %) recurrence events during a median follow-up of 30.8 months after surgery among the 610 patients. When analyzed among all PrCa patients, no association was observed between BMI/obesity and PrCa recurrence. However, when analysis was limited to non-diabetics, obese men had a 2.27-fold increased risk (95 % CI 1.17–4.41) of PrCa recurrence relative to normal weight men, after adjusting for age and clinical/pathological tumor characteristics.

Conclusions

This study found a greater than twofold association between obesity/BMI and PrCa recurrence in non-diabetics. We anticipated these results because the relationship between BMI/obesity and the biologic factors that may underlie the PrCa recurrence–BMI/obesity association, such as insulin, may be altered by the use of anti-diabetes medication or diminished beta-cell insulin production in advanced diabetes. Studies to further assess the molecular factors that explain the BMI/obesity–PrCa recurrence relationship are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Prostate cancer (PrCa) is the most commonly diagnosed solid tumor in men and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in developed countries [1–3]. It has a complex, multi-factorial etiology where both genetic and environmental/lifestyle factors contribute to prostate carcinogenesis [4]. However, the majority of prostate tumors do not progress rapidly or cause significant clinical disease [5], and thus, research is increasingly focused on identifying risk factors that are associated with higher rates of cancer recurrence and/or mortality following treatment.

Obesity has been reported to be a risk factor for the development of incident PrCa. A meta-analysis of 56 studies, for example, reported a relative risk (RR) of 1.05 (95 % CI 1.01–1.08) for PrCa per 5 kg/m2 increase in body mass index (BMI) [6]. Interestingly, though, several cohort studies of this meta-analysis did not report such an association [6], while others have suggested that the association between BMI and PrCa may differ by tumor aggressiveness. That is, obesity was associated with a 25–30 % increased risk of advanced-grade/stage PrCa, but inversely associated with the diagnosis of low-grade/local stage tumors [6–9].

Obesity/BMI at PrCa diagnosis has also been positively associated with risk of PrCa recurrence in two recent meta-analyses [10–12]; however, results of individual studies have been somewhat inconsistent. For instance, while the summary risk estimate for PrCa recurrence was RR = 1.16 (95 % CI 1.08–1.24) per 5 kg/m2 increase in BMI in the most recent analysis [12], only 11 of 26 studies included in this meta-analysis reported statistically significant positive associations; albeit these tended to be the largest and most comprehensive studies. Although some of the inconsistency could be due to differences in ascertainment of patients’ populations, sample size, and number of events, we noted that majority of the studies did not take into account the complex role of BMI/obesity and diabetes in PrCa [12].

One of the major mechanisms through which adiposity is thought to play a role in cancer is via high levels of circulating insulin and insulin resistance in obese individuals [13, 14]. Insulin has mitogenic and anti-apoptotic activity, in addition to its better-known metabolic effects [13]. For example, studies by our group have shown strong associations of fasting insulin levels with risk of postmenopausal breast and endometrial cancer [15, 16]. Because of the potential importance of insulin resistance to the obesity–cancer relationship, several prior studies of PrCa examined the relation of type 2 diabetes with PrCa incidence [17, 18] and recurrence [19–21]. These studies have reported conflicting results, similar to those for the relationship of obesity with PrCa, with the majority of the studies reporting no association between type 2 diabetes and risk of PrCa recurrence.

However, there is a complicated relationship between diabetes and levels of insulin, as patients may use anti-diabetic medications, and insulin levels may fall in advanced diabetes due to reduced insulin secretion by pancreatic β-cells [22, 23]. Thus, studies of diabetes and its relation with risk of PrCa incidence and PrCa recurrence may be complicated by variability in insulin levels among those with frank diabetes.

If correct, then the failure to exclude diabetics from studies of obesity and its associations with PrCa incidence and recurrence could help explain variability in their findings. We recently reviewed and made similar observations regarding the relationship between obesity with breast cancer risk [24].

Therefore, in the current study, we examined association between BMI/obesity and PrCa recurrence both with and without diabetic patients included in the analysis. If as predicted a stronger association of obesity with PrCa recurrence were observed when diabetics were excluded in our study, it would suggest that prior data from other studies should be reanalyzed in a similar fashion to better understand the obesity–PrCa recurrence relationship. Moreover, it would provide strong evidence that molecular pathways related to obesity similar to those involved in other cancers, particularly insulin signaling pathway, may be an important risk factor for PrCa recurrence.

Methods

Study population and data collection

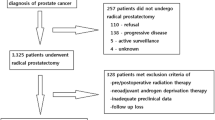

We conducted a retrospective cohort study among PrCa patients who underwent robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy (RALP) by a single surgeon (RG) at Montefiore Medical Center (MMC) in the Bronx from October 2005 through December 2012, and were followed for disease recurrence through 31 December 2012. Detailed electronic medical records (EMR) data were prospectively obtained and updated at each clinical visit. Height and weight were measured at clinic visit when PrCa diagnosis was confirmed via biopsy, and history of type II diabetes and diabetes medication(s) at the time of PrCa diagnosis were abstracted from EMR for all patients. A total of n = 640 PrCa patients underwent RALP during the 7-year period, of which 610 (95 %) men with at least one follow-up laboratory serum PSA measurement after surgery at MMC were included in this analysis. Exclusion criteria were the following: a pathologic tumor stage T0 at surgery (n = 6); missing height and weight measurement (n = 1); or missing follow-up data on serum PSA measurements after surgery (n = 23). Consistent with clinical guidelines, patients were to have PSA levels measured after surgery at intervals of every 3 to 4 months in the first year, 6 months in the second or third year, and annually thereafter. However, PSA measurements were done more frequently if the postoperative serum PSA value exceeded 0.1 ng/dl. The median number of follow-up serum PSA measurements was seven (range 1–28) from date of surgery through date of last visit or 31 December 2012 among the 610 patients. Prostate cancer (PrCa) recurrence was determined as a rise in serum PSA of ≥0.2 ng/ml after radical prostatectomy. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Albert Einstein College of Medicine and MMC.

Statistical analysis

Demographic, clinical, and tumor characteristics were compared among three groups of patients: i.e., those with normal weight (BMI < 25 kg/m2), overweight (BMI 25–29.9 kg/m2), and obese (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) at diagnosis using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous normally distributed variables and Chi-square tests for categorical variables. All tests were two-sided using a significance level of α = 0.05. Among the 610 PrCa patients included in the analysis, there were two men (0.3 %) who had a BMI < 18.5 kg/m2; and their exclusion from these analyses had no impact on the results (data not shown). Therefore, they were included in the BMI < 25 kg/m2 category.

Follow-up time (months) was determined from date of surgery until date of first PrCa recurrence (time to event), date of last visit, or end of follow-up (31 December 2012) whichever occurred first. We compared demographic, BMI, clinical, and tumor characteristics, between patients who recurred and those who did not recur during follow-up using Kaplan–Meier (KM) survival curves and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models [25, 26]. We initially fit a Cox model adjusted for age and then additionally adjusted for clinical/pathological variables that were associated with PrCa recurrence (based on a p < 0.05) including preoperative PSA, pathological Gleason score, tumor stage, and whether the surgical tumor margins were positive or negative. Additional variables that have been reported to be predictors of PrCa recurrence in prior studies, such as race/ethnicity, percent tumor volume in the prostate gland, and positive lymph nodes, were also assessed as potential confounders. However, these variables were not independently associated with PrCa recurrence in multivariate Cox proportional hazard models in our dataset, and thus, they were excluded from the final analyses. All the above analyses in the study were conducted first among all PrCa patients and then repeated by excluding men with diabetes. All statistical analyses were carried out in STATA version 13 (STATA Corporation, College Station, Texas).

Results

The majority of the 610 PrCa patients included in this study were non-Hispanic African-American (36.2 %) or Hispanic men (38.2 %). The prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) and type 2 diabetes at PrCa diagnosis were 25.6 % and 18.7 %, respectively. Table 1 presents demographic, clinical, and histo-pathological tumor characteristics of these PrCa patients stratified by BMI category. There were no significant differences in these characteristics among the three BMI groups, with the exception of ASA score, which was slightly higher in obese men in comparison with other two groups. While not statistically significant, however, it is noteworthy that obese men had lower proportion of a diagnostic PSA ≥ 20 ng/ml (3.8 %), but slightly higher Gleason scores 7 (4 + 3) or 8–10 (25 %) compared with normal weight men. We also compared demographic and clinical characteristics of diabetic PrCa patients (n = 114; supplemental Table S1) and non-diabetic PrCa patients (n = 496; supplemental Table S2) stratified by BMI category, in separate analyses. Among diabetic patients, there was a positive association between BMI and surgical margins, where obese diabetic patients had higher proportions of positive margins in comparison with the other two BMI categories (p = 0.02). However, among non-diabetic patients (n = 496), there were positive associations between BMI category and ASA score and Gleason score, in which obese men had significantly higher ASA score and higher Gleason score (i.e., 7 = 4 + 3 or 8–10 tumors) in comparison with normal weight men (supplemental Table S2).

Among 610 PrCa patients, 14.3 % (n = 87) had a cancer recurrence during a median 30.8 months (interquartile range 14.2–51.6) of follow-up after surgery. Table 2 shows our age-adjusted analyses of associations between PrCa recurrence and demographic variables age, race/ethnicity, BMI, as well as clinical and histo-pathological tumor characteristics among all men (n = 610), including those with and without diabetes. As expected, several clinical and pathological tumor characteristics were associated with PrCa recurrence. Men diagnosed with a serum PSA ≥ 10 ng/ml, or pathological Gleason score of 7 (4 + 3) or 8–10, or pathological tumor stage T3a, b or c, a positive lymph node, a higher percentage of tumor volume in the prostate gland, and those with positive surgical margins were more likely to recur (all p values <0.001). However, in the age-adjusted analysis, there were no associations between PrCa recurrence and BMI (either as continuous or categorical variable), or type 2 diabetes among all PrCa patients.

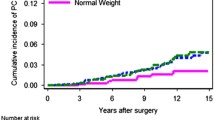

We then examined associations between the same variables and risk of PrCa recurrence after excluding men with diabetes (Table 3). A total of n = 496 non-diabetic men were included in this analysis. In contrast to the results among all subjects, the results in non-diabetic PrCa patients showed a significantly increased risk of PrCa recurrence among obese men relative to normal weight men (Table 3 and Fig. 1). In multivariate-adjusted Cox proportional hazard models (Table 4), among non-diabetic PrCa patients, an increase of 5 kg/m2 in BMI was associated with a 38 % increased risk of PrCa recurrence (95 % CI 1.05–1.82; p = 0.02). In categorical analysis, non-diabetic obese men (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) had a 2.27-fold higher risk of PrCa recurrence (95 % CI 1.17–4.41; p = 0.02) relative to normal weight men, after adjusting for age, preoperative PSA, pathological Gleason score, tumor stage, and presence of positive surgical tumor margins. Overall, there was a monotonic increase in risk of cancer recurrence with increasing BMI stratum; i.e., relative to normal weight men, there was a non-significantly higher risk in overweight men and then a statistically significantly elevated risk in obese men (p-trend = 0.03).

Discussion

We investigated the association between BMI/obesity and PrCa recurrence in a racially and ethnically diverse patient population (36 % African-American and 38 % Hispanic) and, furthermore, addressed the importance of excluding diabetics from the study of the BMI/obesity–PrCa recurrence relationship. The analysis of these data in a population with a high number of minority men is particularly relevant, given the disproportionately higher prevalence of obesity among African-American and Hispanic men [27–29], as well as higher rates of PrCa recurrence and mortality especially among African-Americans [1–3]. Prior reports regarding the relation of obesity and PrCa recurrence had inconsistent results [10, 12]. A priori hypothesis behind our analytic plan was that the inconsistency in the findings of earlier studies of obesity and PrCa recurrence could be explained, in part, by the failure of previous investigations to exclude diabetics from their analysis.

Our results showed a greater than twofold increased risk of PrCa recurrence among obese men after excluding diabetics from the analysis, but no effect when diabetics were included. These analyses were adjusted for age and other important clinical predictors of PrCa recurrence such as preoperative PSA, pathological Gleason score, tumor stage, and presence of positive surgical tumor margins. All patients were treated by the same surgeon using robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy at a single institution.

Of the 18 studies included in the most recent meta-analysis [12], which investigated the associations of BMI/obesity with risk of biochemical recurrence among PrCa patients treated with radical prostatectomy, only two studies [30, 31] reported on the prevalence of diabetes, but none of them excluded diabetic patients from their analysis to determine the impact of diabetes on the relationship between BMI/obesity and PrCa recurrence. Basset and colleagues [31] followed 2,131 PrCa patients (90 % Caucasian) who had undergone prostatectomy between 1989 and 2003 and were part of the Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor (CaPSURE) study. The prevalence of obesity and diabetes were 22 % and 8 %, respectively, in that cohort, and 251 (12 %) men had a PrCa recurrence during a median 13-month of follow-up [31]. They reported a RR = 1.31 (95 % CI 1.00–1.71) for obese versus non-obese men, and the association was stronger for very obese men (RR = 1.69; 95 % CI 1.01–2.84 for BMI ≥35 vs. <25 kg/m2). In another study, Asmar and colleagues [30] examined associations between BMI, diabetes, and risk of biochemical recurrence among 1,428 PrCa patients (81 % Caucasian; 8 % African-American) who had undergone prostatectomy at the University of Michigan between 1994 and 2007 and were followed for cancer recurrence. The prevalence of obesity and diabetes was 33 % and 13 %, respectively, in that study, and 107 (8 %) men had a recurrence during a median follow-up of 3.6 years. Interestingly, there was a suggestion for an increased risk of PrCa recurrence associated with obesity in this study, albeit not statistically significant (RR = 1.37, 95 % CI 0.92–2.09 for obese vs. non-obese men), but no association between diabetes and PrCa recurrence [30]. It is interesting to note that with the increasing prevalence of diabetes, the association between BMI/obesity and PrCa recurrence tends to go toward the null as it was the case in our study where prevalence of diabetes was 19 %. It is also important to note that none of these studies carried out a sensitivity analysis to exclude diabetics, as we did in our analysis. Our findings suggest that all prior studies of the obesity and PrCa recurrence should be reanalyzed now by excluding diabetic patients.

The current findings and literature review are consistent with a general concern we have raised in studying the effects of obesity and insulin levels with cancer risk and recurrence, without excluding diabetics, across different tumor types [15, 16, 24]. The inclusion of diabetics in such studies is problematic since serum insulin levels in individuals with type 2 diabetes may be altered by use of exogenous insulin or medications that influence insulin sensitivity and secretion [22, 23]. Furthermore, individuals with advanced diabetes may experience reduced insulin secretion by pancreatic β-cells [22, 23]. While the relation between serum insulin and risks of PrCa incidence or recurrence/mortality has not been extensively studied, we have previously shown that the attributable risk of postmenopausal breast cancer explained by insulin levels was greater than that for estradiol, and in multivariate models adjustment for insulin but not estradiol accounted for the BMI effect on breast cancer risk [16].

With regard to PrCa mortality, Ma and colleagues [32] examined the role of both pre-diagnostic BMI and plasma C-peptide (reflecting insulin secretion) on PrCa-specific mortality among 2,546 men (95 % Caucasian) with incident PrCa from the Physician’s Health Study who were followed for mortality (n = 281 PrCa deaths during a median 7 years of follow-up). Overall, there was a linear increase in risk of PrCa-specific mortality per one kg/m2 increase in BMI (RR = 1.07; 95 % CI 1.02–1.12) and the risk was highest among obese men (RR = 1.95; 95 % CI 1.17–3.23 when comparing obese vs. normal weight men) [32]. Since the prevalence of diabetes was very low in this cohort (1.5 %), the association between BMI and PrCa-specific mortality remained the same after exclusion of diabetics. To our knowledge, no other studies conducted analyses stratified by diabetes or by excluding diabetic patients. Ma and colleagues [32] also assessed association between C-peptide levels and PrCa-specific mortality among 825 PrCa patients in this study and reported a RR of 2.38 (95 % CI 1.31–4.30) for highest versus lowest quartile (p-trend = 0.03). Inclusion of BMI in this model slightly attenuated the association of C-peptides with PrCa mortality; however, inclusion of both BMI and PrCa clinical/pathological features in the same model attenuated the associations for both obesity (RR = 1.87, 95 % CI 0.80–4.37) and C-peptide (RR = 1.72, 95 % CI 0.92–3.24, for Q4 vs. Q1; p-trend = 0.11) [32]. This finding suggested that the association between BMI and PrCa-specific mortality was partly mediated through C-peptide (proxy for insulin).

Our results also provide novel but indirect evidence that as with several other common cancers (e.g., breast) insulin signaling may play a biologic role in PrCa recurrence. This is important since in addition to obesity being a readily modifiable risk factor, insulin signaling is itself potentially modifiable. Higher insulin levels have been positively associated with prostate carcinogenesis [32, 33]. Also the direct measurement of insulin signaling in the tissues such as expression of insulin receptor (IR) has been reported to be higher in prostate tumors versus benign prostate epithelial cells [34]. However, the relationships between total IR as well as activated IR expression levels, in relation to PrCa recurrence have not, to our knowledge, been studied.

Inflammatory factors may also help explain the relation of obesity with PrCa recurrence. Adipose tissue is known to secrete both adipokines and inflammatory cytokines that induce proliferation and suppress apoptosis of cancer cells and hence promote growth of primary tumors [35–37]. Inflammatory cells also produce various pro-inflammatory chemokines, which, in addition to recruiting leukocytes to infiltrate the local inflammatory site, may act as angiogenic factors or growth factors that further stimulate tumor progression [38–40]. Chronic inflammation is frequently observed in prostate tumors and correlates with higher Gleason score and higher serum PSA levels [41–43]. A recent study of 287 prostatectomy specimens showed that markers of intra-tumor inflammation were associated with a 2.1-fold increased risk of PSA recurrence (95 % CI 1.02–4.24), although this association was attenuated when accounting for tumor pathological features [44]. Furthermore, treatment for diabetes might result in reduction in systemic inflammation, leading to disconnect that we observed between obesity and PrCa recurrence.

Several limitations of the study must be considered in the interpretation of the current data. In particular, we studied only PrCa recurrence and not the development of metastases or PrCa-specific mortality. Longer follow-up will be required to conduct such analyses. Nonetheless, PrCa recurrence is a well-established endpoint, and it is an important step in PrCa progression to metastasis and cancer-related mortality. We also did not assess other measures of obesity such as waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, or weight change and their association with PrCa recurrence in the current study. Other studies have shown that weight gain in men is associated with increased risk of PrCa recurrence [45, 46]. Also some of the non-diabetic patients (i.e., those without known history of type 2 diabetes) could have had potentially undiagnosed diabetes. However, if this were the case, the strength of the association between BMI/obesity and PrCa recurrence that we observed in this study would be an underestimate of the true association. In this study, diabetic patients had similar BMI in comparison to non-diabetic men at the time of PrCa diagnosis: 27.3 ± 4.3 versus 27.6 ± 4.1 kg/m2 (p = 0.49). One potential explanation for the apparent lack of a positive association between BMI and type 2 diabetes among PrCa patients could be that men with long-term type 2 diabetes could have lost weight due to dietary changes or oral metformin medication [47, 48]. For example, in the Diabetes Prevention Program, diabetic patients who were taking metformin had significantly higher weight loss and reduced waist circumference during follow-up in comparison to patients who were taking placebo [47]. Potential mechanisms by which metformin could affect weight loss include the reduction in food intake by decreasing the orexigenic peptides, neuropeptide-Y, and agouti-related protein in the hypothalamus; by improving leptin and insulin sensitivity and by increasing glucagon-like peptide-1 levels; as well as by creating favorable changes in fat metabolism via lowering both circulating and hepatic lipid levels [48]. Finally, we could not directly study the molecular mechanisms that we hypothesize underlie the relation of PrCa recurrence with obesity given the data available in this study. Future studies with appropriate specimens to assess insulin/insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-axis signaling in PrCa recurrence are warranted.

In summary, the current study showed a strong association between obesity and PrCa recurrence among non-diabetic PrCa patients, and it also provided evidence that it is critical to exclude diabetics when studying this relationship. Prior studies of the obesity–PrCa recurrence relationship should consider reanalyzing their data by restricting analysis to non-diabetics, particularly if the prevalence of diabetes is high. Molecular studies to directly assess the biologic factors that explain the BMI/obesity–PCa recurrence relationship are now warranted.

References

American Cancer Society (ACS) (2014) Cancer facts & figures 2014. Atlanta, GA

Howlader N, Noone A, Krapcho M, Garshell J, Miller D, Altekruse S et al (2014) SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2011. National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2011/. Based on November 2013 SEER data submission, posted to the SEER web site, April 2014

Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A (2014) Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 64(1):9–29

Lichtenstein P, Holm NV, Verkasalo PK, Iliadou A, Kaprio J, Koskenvuo M et al (2000) Environmental and heritable factors in the causation of cancer—analyses of cohorts of twins from Sweden, Denmark, and Finland. N Engl J Med 343(2):78–85

Carter HB, Piantadosi S, Isaacs JT (1990) Clinical evidence for and implications of the multistep development of prostate cancer. J Urol 143(4):742–746

MacInnis RJ, English DR (2006) Body size and composition and prostate cancer risk: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Cancer Causes Control 17(8):989–1003

Gong Z, Neuhouser ML, Goodman PJ, Albanes D, Chi C, Hsing AW et al (2006) Obesity, diabetes, and risk of prostate cancer: results from the prostate cancer prevention trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 15(10):1977–1983

Hsing AW, Sakoda LC, Chua S Jr (2007) Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and prostate cancer. Am J Clin Nutr 86(3):s843–s857

Freedland SJ, Platz EA (2007) Obesity and prostate cancer: making sense out of apparently conflicting data. Epidemiol Rev 29:88–97

Cao Y, Ma J (2011) Body mass index, prostate cancer-specific mortality, and biochemical recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Prev Res 4(4):486–501

Chalfin HJ, Lee SB, Jeong BC, Freedland SJ, Feng Z, Trock BJ et al (2014) Obesity and long-term survival after radical prostatectomy. J Urol 192(4):1100–4. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2014.04.086

Hu MB, Xu H, Bai PD, Jiang HW, Ding Q (2014) Obesity has multifaceted impact on biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer: a dose–response meta-analysis of 36,927 patients. Med Oncol 31(2):829

Pollak M (2008) Insulin and insulin-like growth factor signalling in neoplasia. Nat Rev Cancer 8(12):915–928

Renehan AG, Frystyk J, Flyvbjerg A (2006) Obesity and cancer risk: the role of the insulin-IGF axis. Trends Endocrinol Metab 17(8):328–336

Gunter MJ, Hoover DR, Yu H, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Manson JE, Li J et al (2008) A prospective evaluation of insulin and insulin-like growth factor-I as risk factors for endometrial cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 17:921–929

Gunter MJ, Hoover DR, Yu H, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Rohan TE, Manson JE et al (2009) Insulin, insulin-like growth factor-I, and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst 101(1):48–60

Kasper JS, Giovannucci E (2006) A meta-analysis of diabetes mellitus and the risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev 15(11):2056–2062

Zhang F, Yang Y, Skrip L, Hu D, Wang Y, Wong C et al (2012) Diabetes mellitus and risk of prostate cancer: an updated meta-analysis based on 12 case-control and 25 cohort studies. Acta Diabetol 49(Suppl 1):S235–S246

Currie CJ, Poole CD, Jenkins-Jones S, Gale EA, Johnson JA, Morgan CL (2012) Mortality after incident cancer in people with and without type 2 diabetes: impact of metformin on survival. Diabetes Care 35(2):299–304

Oh JJ, Hong SK, Lee S, Sohn SJ, Lee SE (2013) Diabetes mellitus is associated with short prostate-specific antigen doubling time after radical prostatectomy. Int Urol Nephrol 45(1):121–127

Rieken M, Kluth LA, Xylinas E, Fajkovic H, Becker A, Karakiewicz PI et al (2014) Association of diabetes mellitus and metformin use with biochemical recurrence in patients treated with radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer. World J Urol 32(4):999–1005. doi:10.1007/s00345-013-1171-7

Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, Diamant M, Ferrannini E, Nauck M et al (2012) Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 35(6):1364–1379

American Diabetes Association (2014) Standards of medical care in diabetes—2014. Diabetes Care 37(Suppl 1):S14–S80

Ligibel JA, Strickler HD (2013) Obesity and its impact on breast cancer: tumor incidence, recurrence, survival, and possible interventions. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2013:52-9. doi:10.1200/EdBook_AM.2013.33.52

Cox DR (1972) Regression models and life tables (with discussion). J R Stat Soc B 34:187–220

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S (1999) Applied survival analysis. Wiley, New York

Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR (2010) Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA 303(3):235–241

Ogden CL, Carrol MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM (2012) Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. In: National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) Data Brief 2012, vol 82, pp 1–7

Wong RJ, Chou C, Ahmed A (2014) Long Term Trends and Racial/Ethnic Disparities in the Prevalence of Obesity. J Community Health 39(6):1150–1160

Asmar R, Beebe-Dimmer JL, Korgavkar K, Keele GR, Cooney KA (2013) Hypertension, obesity and prostate cancer biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 16(1):62–66

Bassett WW, Cooperberg MR, Sadetsky N, Silva S, DuChane J, Pasta DJ et al (2005) Impact of obesity on prostate cancer recurrence after radical prostatectomy: data from CaPSURE. Urology 66(5):1060–1065

Ma J, Li H, Giovannucci E, Mucci L, Qiu W, Nguyen PL, Gaziano JM, Pollak M, Stampfer MJ (2008) Prediagnostic body-mass index, plasma C-peptide concentration, and prostate cancer-specific mortality in men with prostate cancer: a long-term survival analysis. Lancet Oncol 9(11):1039–1047

Albanes D, Weinstein SJ, Wright ME, Mannisto S, Limburg PJ, Snyder K, Virtamo J (2009) Serum insulin, glucose, indices of insulin resistance, and risk of prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 101(18):1272–1279

Cox ME, Gleave ME, Zakikhani M, Bell RH, Piura E, Vickers E, Cunningham M, Larsson O, Fazli L, Pollak M (2009) Insulin receptor expression by human prostate cancers. Prostate 69(1):33–40

de Visser KE, Coussens LM (2006) The inflammatory tumor microenvironment and its impact on cancer development. Contrib Microbiol 13:118–137

Gerber PA, Hippe A, Buhren BA, Muller A, Homey B (2009) Chemokines in tumor-associated angiogenesis. Biol Chem 390(12):1213–1223

Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M (2010) Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell 140(6):883–899

Ben-Baruch A (2006) Inflammation-associated immune suppression in cancer: the roles played by cytokines, chemokines and additional mediators. Semin Cancer Biol 16(1):38–52

de Visser KE, Eichten A, Coussens LM (2006) Paradoxical roles of the immune system during cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer 6(1):24–37

Rosenkilde MM, Schwartz TW (2004) The chemokine system—a major regulator of angiogenesis in health and disease. Apmis 112(7–8):481–495

De Marzo AM, Platz EA, Sutcliffe S, Xu J, Gronberg H, Drake CG, Nakai Y, Isaacs WB, Nelson WG (2007) Inflammation in prostate carcinogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer 7(4):256–269

Nelson WG, De Marzo AM, DeWeese TL, Isaacs WB (2004) The role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of prostate cancer. J Urol 172(5 Pt 2):S6–S11 discussion S11–12

Schatteman PH, Hoekx L, Wyndaele JJ, Jeuris W, Van Marck E (2000) Inflammation in prostate biopsies of men without prostatic malignancy or clinical prostatitis: correlation with total serum PSA and PSA density. Eur Urol 37(4):404–412

Klink JC, Banez LL, Gerber L, Lark A, Vollmer RT, Freedland SJ (2013) Intratumoral inflammation is associated with more aggressive prostate cancer. World J Urol 31(6):1497–1503

Strom SS, Wang X, Pettaway CA, Logothetis CJ, Yamamura Y, Do KA, Babaian RJ, Troncoso P (2005) Obesity, weight gain, and risk of biochemical failure among prostate cancer patients following prostatectomy. Clin Cancer Res 11(19 Pt 1):6889–6894

Joshu CE, Mondul AM, Menke A, Meinhold C, Han M, Humphreys EB, Freedland SJ, Walsh PC, Platz EA (2011) Weight gain is associated with an increased risk of prostate cancer recurrence after prostatectomy in the PSA era. Cancer Prev Res 4(4):544–551

Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group (2012) Long-term safety, tolerability, and weight loss associated with metformin in the diabetes prevention program outcomes study. Diabetes Care 35(4):731–737

Malin SK, Kashyap SR (2014) Effects of metformin on weight loss: potential mechanisms. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 21(5):323–329

Acknowledgments

Dr. Ilir Agalliu was supported by a Mentored Research Scholar Grant (MRSG-11-112-01-CNE) from the American Cancer Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Howard D. Strickler and Reza Ghavamian have contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Agalliu, I., Williams, S., Adler, B. et al. The impact of obesity on prostate cancer recurrence observed after exclusion of diabetics. Cancer Causes Control 26, 821–830 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-015-0554-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-015-0554-z