Abstract

We provide evidence on the effects of criminal/corrupt politicians on firm performance and investments in their constituencies. Using a regression discontinuity approach, we focus on close parliamentary elections in India to establish a causal link between election of criminal-politicians and firms’ stock-market performance and investment decisions. Election of criminal-politicians leads to lower election-period and project-announcement stock-market returns for private-sector firms with economic ties to the district. There is a significant decline in total investment and employment by private-sector firms in criminal-politician districts. Interestingly, decline in private-sector investment is largely offset by a roughly equivalent increase in investment by state-owned firms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Anecdotal and survey evidence suggest that emerging economies are rife with corruption – far more so than more developed economies (e.g., Svensson, 2005). Contributing to the pervasive corruption are a plethora of factors that are associated with developing countries such as weak institutions, bureaucratic red-tape and cultural norms that are accepting of (or resigned to) corruption. Reducing corruption has proven to be difficult—which may not be surprising since it is in the interest of beneficiaries of a corrupt system to maintain weak institutions and complex, arbitrary rules that facilitate corruption.Footnote 1

We focus on the economic implications of rampant corruption in India, a large developing country long plagued by corruption/criminality among its politicians and bureaucrats. In recent years, corruption has emerged as a potent political issue and likely affected the outcome of the 2014 general election.Footnote 2 The effort to clean elections has led to wider dissemination of information about the background of the candidates for public office, including criminal charges and convictions. This, combined with novel and fairly comprehensive data on project investments by Indian corporations, allows us to investigate questions about the interplay between corruption and electoral outcomes on the one hand, and corporate stock market performance and investment decisions on the other.

While there are several studies of corruption in emerging economies including India, there are relatively few reliable estimates of the actual magnitude and broader economic consequences of corruption In particular, empirical evidence linking the presence of corrupt politicians to firms' real activity and shareholder value is scarce. It is difficult to know, therefore, whether the election of corrupt politicians has significant implications for economic growth. This is since it is hard to discern whether corruption has a negative causal effect on economic growth or whether the corruption is largely a manifestation of poor economic and social conditions and does not per se, have a meaningful effect on economic growth.

We study the effect of Indian politicians with criminal backgrounds on the value and performance of firms and investments in their electoral districts. Since 2003, Supreme Court of India has mandated that the candidates contesting elections for federal and state legislatures file an affidavit declaring pending criminal cases, past convictions, assets, liabilities, educational qualifications etc. For our study, we use a database that collects the criminal background and other variables from the affidavits filed by candidates with the Election Commission of India before the 2004 and 2009 General Elections for the Lok Sabha (lower house of Indian Parliament). We refer to these politicians as “criminal” though, in most cases, they have been charged, rather than convicted of criminal activity. Actual conviction rates tend to be low, possibly indicating the difficulty of convicting politicians. The use of this data is validated by other studies that suggest that being charged with criminal activity correlates well with other measures of corruption.Footnote 3 For instance, charges of criminal behavior are strongly related to indicators of corruption such as growth in personal assets (Fisman et al., 2014) and survey data (Banerjee & Pande, 2007). In the paper we will, therefore, refer interchangeably to criminal and corrupt politicians.

Our data allows us to explore key questions, such as the impact of corrupt/criminal politicians on economic activity. To establish a causal link between the election of criminal politicians and firm stock-market value, we use a regression discontinuity approach that has been used in the literature on the causal effects of elections (e.g., Chemin, 2012; Lee, 2008). Specifically, we compare the effects on firm and project values in districts where a criminal politician narrowly wins the election to the districts in which they narrowly lose against a non-criminal candidate. Further, we examine the response of corporations in terms of whether new investment projects are initiated, and existing ones are completed or stalled. Our overall finding is that the election of corrupt politicians has a negative effect on firms with significant investments in the politician’s district. Corporations are less likely to initiate or to complete projects in districts in which a criminal politician wins. In addition, the announcements of new projects in these districts tend to be received less favorably by investors. Districts in which a criminal candidate narrowly wins, experience a sharp average reduction in private firm capital expenditures of about $664.4 million in the five years following the election. On the other hand, there is an average increase of $488.1 million in investment in districts where a criminal candidate narrowly loses to a noncriminal candidate. The difference of $1.15 billion is both economically and statistically significant.

The finding that the election of corrupt politicians discourages new investment projects and hurts the stock market value of firms in their districts raises the question of how these politicians are, nevertheless, able to attract support from voters and get elected?Footnote 4 A possibility is that certain communities are willing to support politicians from their own communities (or castes) as long as the criminal activities work in their favor or, at least, are not directed against the community. It is also possible that corrupt politicians support local enterprises—while disfavoring competition from outside firms. We, therefore, examine the impact of election outcomes on firms with economic ties to the politician’s district in terms of past investments, classifying firms as local or non-local in terms of their headquarter location. We also distinguish between privately owned and state-majority-owned enterprises (SOEs).Footnote 5

Our results indicate that both local and non-local private corporations suffer when a corrupt politician is in power. When a criminal politician wins an election (in close elections), both types of firms experience significantly lower stock returns. There is also a decrease in aggregate investment by firms in the corrupt politician’s district, though effects are smaller for local firms. An intriguing finding, however, is that while there is a reduction in investment by private corporations—this is offset to a degree by an increase in investment by state-majority-owned enterprises. This suggests that, to an extent, corrupt politicians could keep their supporters satisfied, by providing them business opportunities in connection with investments by state-owned firms over which they may exercise some control. On employment, however, the overall effect appears to be negative, at least for the limited district-level data available to us for the fiscal years around the 2004 election. There is a significantly lower growth rate in private firm employment following the electoral victory of criminal politicians. The growth in SOE employment in districts where the criminal politician won is weakly higher or the same compared to the growth of SOE employment in districts where the criminal politician lost.

Our findings on state-owned enterprises is consistent with the evidence that corrupt politicians favor state-owned enterprises over non-state-controlled firms. Nguyen and Dijk (2012), for instance, finds that corruption hampers the growth of Vietnam’s private sector but is not detrimental for growth in the state sector. We find as well that corrupt politicians appear to discourage the growth of private firms but facilitate the growth of SOEs—possibly as a way to extract personal benefits and to keep their supporters satisfied by providing them with business and employment opportunities. An implication is that reducing political players’ access to favors from state-owned enterprises, such as through privatization, could help reduce corruption in countries with state-owned corporations.

Hypotheses and Related Literature

Hypotheses

Corruption is endemic to many developing countries and is generally associated with weaker institutions and poorer economic conditions. While there is a literature that suggests that welfare implications of corruption might be small or even improve outcomes (e.g., Leff, 1964), there appears to be growing academic and policy consensus that corruption is often high in low-income countries and that it is costly (see e.g., Olken & Pande, 2012).

In the paper we examine the economic consequences of the election of corrupt politicians on the profitability, investment and employment of firms in their electoral districts. In general, we might expect corrupt politicians to use their positions to extract rents from firms in their districts and to negatively affect the value and profitability of these firms. As noted earlier, to establish a causal link between the election of criminal politicians and the firm’s stock market performance, we use a regression discontinuity approach, Specifically, we compare the impact on firms in districts in which a criminal politician narrowly wins to those in which there is a narrow loss to a non-criminal candidate. This leads to our first formal hypothesis:

Hypothesis- 1A

A close election win by a corrupt politician will have a significantly negative effect on the stock market performance and valuation of private sector firms in the politician’s district.

The negative costs imposed by corrupt elected politicians are likely to be affected by factors such as the incumbency of politicians and the level of corruption at the state level – both of which are likely to exacerbate the negative effects of a corrupt politician being returned to power. Incumbent politicians might, for instance, have existing relationships with local government officials responsible for issuing various permits, which facilitates the extraction of rents; while high levels of state corruption could imply that there were few legal repercussions for corrupt activities. This leads to the hypothesis below:

Hypothesis- 1B

A close election win by a corrupt politician will have a greater negative effect on the stock market value of private sector firms if the district is in a state with worse corruption and the corrupt politician is an incumbent.

Corrupt politicians might also be more likely to extract rents from private sector firms rather than SOEs which are often rigidly bound by government rules and reporting requirements.Footnote 6 We state the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis- 1C

A close election win by a corrupt politician will result in a more moderate negative effect on the stock market value of SOEs, relative to private-sector firms.

The election of a corrupt politician might also have different consequences for local firms with headquarters in the district versus those that are non-local. It is plausible, for instance, that criminal politicians may favor local firms, particularly ones with which they have had a past relationship, at the expense of non-local firms. This could be done by increasing barriers to entry for non-local firms by, for instance, making it difficult to obtain permits for construction or utility connections. For our initial tests we follow some of the literature on the economic consequences of corruption, papers such as Fisman (2001) and Faccio (2006) and examine the firm’s stock market performance in reaction to the win or loss of corrupt politicians in the district. Our next hypothesis, about firms’ stock market performance on announcements of new projects draws on the notion that projects will be perceived to be less valuable when a corrupt politician is likely to extract rents. We can state:

Hypothesis-2

The announcement of new projects in districts in which the elected representative is corrupt (non-corrupt) will be less (more) positively received by stock market investors.

The above hypotheses focus on the effect of corrupt politicians on firms’ stock market reaction to election outcomes and project announcements. We next turn to the investment and performance of district firms in the aftermath of a corrupt politician being elected in the district. We expect that private sector firms, given the possible rent extraction by corrupt politicians, will be less likely to initiate or to complete projects in districts in which a criminal politician wins. Along with the drop in investments, we would expect there to be decrease in firm performance as indicated by accounting measures such as ROA and stock market value indicators such as the Q-ratio:

Hypothesis-3A

Following the election of a corrupt politician, there will be a significant decline in investments and performance of private-sector firms in the politician’s district.

We expect that these performance and value effects might differ by whether a firm is based locally. For instance, it is possible that corrupt politicians support local enterprises—while disfavoring competition from outside firms, even while they extract rents from both types of firms. In our analysis, we examine the impact of election outcomes on firms with economic ties to the politician’s district in terms of past investments, classifying firms as local or non-local in terms of their headquarter location. We also distinguish between privately owned and state-majority-owned enterprises (SOEs). This leads to our next hypothesis:

Hypothesis-3B

Following the election of a corrupt politician, there will be a more moderate decline in investments and stock market performance of SOEs in the politician’s district, relative to private-sector firms.

From above, we expect that the election of corrupt politicians will discourage new investment projects and hurt the stock market value of firms in their districts. As a result, it is reasonable to expect that private sector firms would experience a significant decline in their employment. We state the hypothesis below:

Hypothesis-4A

Following the election of a corrupt politician, private-sector firms will significantly reduce employment in the politician’s district.

For state-majority-owned enterprises, however, if there is little change in investments and performance, we might expect that their employment may increase or at least not decline. It is plausible that corrupt politicians might be effective at influencing SOEs to hire their supporters. However, even if SOEs increase investments, employment growth might be limited since SOEs, at least prior to their partial privatization, tended to be heavily staffed to serve social or political objectives. Hence, if some of the overstaffing issues have persisted, this could lower the need to hire more employees despite higher investment. We state the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis-4B

Following the election of a corrupt politician, there will be little or no decline in SOE employment in the politician’s district.

Related Literature

Our paper is related to several strands of the finance and economics literature. First is the literature on the relation between corruption and economic growth. Some of this literature, such as Leff (1964) and Huntington (1968), suggests that corruption might promote efficiency and growth by “greasing the wheels of bureaucracy”. The efficiency argument is essentially that the most efficient firms will be assigned projects since they can afford to pay the largest bribes.Footnote 7 A sharply divergent view is the “grabbing hand” view of corruption (Frye & Shleifer, 1997; Shleifer & Vishny, 1993, 1998). According to this view, corruption affects economic growth. It can lead to the propping up of inefficient enterprises and a misallocation of human and financial capital. In these environments, entrepreneurs will seek ways to minimize their exposure to public corruption, even if this results in the adoption of inefficient technologies.Footnote 8 Olken and Pande (2012) provides a survey of the corruption literature and argues that there appears to be growing academic and policy consensus that corruption is often high in low-income countries and that it is costly.

Our paper is also related to a relatively new and growing literature that examines the effect of political connections on firm performance and stock market value. Among these, Fisman (2001) estimates the value of political connections by examining the stock price reaction of Indonesian firms connected to Suharto to news releases about his health. Faccio (2006) examines the value of political connections in several countries and finds positive benefits channeled to relatively poor performing firms. Similar results are reported in Goldman et al. (2009) and Do et al. (2013).

There are several papers that examine the welfare effects of criminal politicians. For example, using a regression discontinuity design (RDD) approach around elections, Chemin (2012) shows that criminal politicians have a negative effect on their constituents. Using a similar RDD, Lehne et al. (2018) shows that political interference in India raises the cost of road construction, while Asher and Novosad (2017) finds that the local economy benefits from being represented by a politician from the ruling party. Fisman et al. (2014) study the wealth accumulation of Indian politicians and show that annual asset growth of election winners is 3–5% higher than losers. Prakash et al. (2019) show that aggregate economic growth in constituencies in India that elect criminally accused politicians is lower.

Fisman and Svensson (2007) studies the impact of corruption on firm growth and finds that a 1 percentage point increase in bribes reduces annual firm growth by 3 percentage points. Khwaja and Mian (2005) show that politically connected firms, defined as those with a politician on their board, receive larger loans from government banks despite a higher default rates on these loans. This suggests that one reason for politicians to start or join existing firms, is that it enables them to capture public resources through corruption. Sequeira and Djankov (2014) examines a different type of distortion and finds that firms in South Africa are willing to pay much higher trucking costs to avoid having to pay bribes in Mozambique. Among recent studies in the context of US firms, Brown et al. (2021) finds that firm-level economic rents and monitoring mechanisms moderate the negative relation between corruption and firm stock market value, while Dass et al. (2016) reports that firms have significantly lower value (Tobin’s q) and informational transparency in more corrupt areas.

Finally, our paper examines the impact of election outcomes on firms with economic ties to a corrupt politician’s district and distinguishes between firms that are local or non-local in terms of headquarter location. This is related to several papers that study the diffusion of information about local economic events on firms with connections to various geographic areas. Among these, Smajlbegovic (2019) studies the diffusion of news from economically relevant regions into firms’ stock prices. Different aspects of geographic distribution and diffusion of information on stock prices and investor decisions are studied in Bernile et al. (2015) and Jannati (2020). Also related is a theoretical model in Acemoglu et al. (2015) that examines the role of network interactions in propagation and amplification of microeconomic shocks.

Data and Method

We use data from multiple sources. Since 2003, Supreme Court of India has required candidates contesting elections for federal and state legislatures to file an affidavit that declares pending criminal cases and past convictions and provides information such as assets, liabilities and educational qualifications. The specific database we use is compiled by the Association of Democratic Reform (available at http://www.myneta.info) that collects the criminal background and other variables from the affidavits filed by candidates with the Election Commission of India before the 2004 and 2009 General Elections for the Lok Sabha, the lower house of Indian Parliament.Footnote 9 We get the election results data i.e., the number of votes polled for each candidate and the total number of votes polled in each constituency from the Election Commission of India website (www.eci.nic.in) and merge it with the database of candidate background variables. We match the parliamentary constituencies with administrative districts using the information available on the Election Commission of India website.Footnote 10 We also account for the change in constituencies or their boundaries caused due to delimitation of constituencies before the 2009 elections.

The summary statistics for the elections database is presented in Table 1. Our sample includes 1023 constituencies out of the 1086 constituencies for which voting was held during two general elections (2004 and 2009). These constituencies cover 569 districts during the 2004 elections and 574 districts during the 2009 elections.Footnote 11 Our main variable of interest from the candidate affidavits is the criminal background of the winner and runner-up candidates in each of the Lok Sabha constituencies. 24.4% of the elected MPs in 2004 and 30.4% of winners in 2009 had at least one criminal case pending against them. The number and seriousness of the criminal cases vary across candidates. The maximum number of pending criminal cases in our sample was 46 against the elected MP (Member of Parliament) in 2009 from Palamu constituency in Jharkhand state. The majority of the elected MPs with criminal backgrounds have less than three criminal cases pending against them. The severity of the cases varies from being very serious criminal cases (Murder, Kidnapping etc.) to relatively minor ones. Given that very few Indian politicians are ever convicted by the courts, we use the presence of a pending case as a noisy proxy for the criminal or corrupt background of the politician. For expositional ease, we will refer to these politicians as ‘criminal’ or ‘corrupt’. We show that our results generally hold when we use an alternative measure of corruption, the asset growth (self-reported) that the politician experiences following an election victory. This asset-growth measure has been regarded as an indicator of corruption (Fisman et al., 2014). In our sample, 315 elections (30.8% of all elections) are contested between a criminal and a non-criminal out of which 114 are close elections with a win margin less than or equal to 5% of all votes polled.

In Panel C of Table 1, we categorize the charges against criminally-charged candidates into six broad categories based on the classification methodology used by the National Crime Records Bureau. We list the percentage of criminally-charged candidates that have been charged with at least one crime in the corresponding crime category. As indicated, 64% of the candidates with criminal backgrounds are charged with at least one crime against public order; 55% have at least one criminal charge in the crimes against body category (that includes crimes such as murder and kidnapping), while 15% are charged with an economic crime. We also categorize crimes by whether they are violent (Crimes against Body and Crimes against Women and Children) or non-violent. As indicated, 56% of the criminal candidates have been charged with at least one violent crime. As shown in Fig. 1, the presence of members of parliament with criminal backgrounds is not limited to certain regions or states in the country. Overall, about one third of the districts in India have at least one elected Member of Parliament with a criminal background.

Criminal Politicians Index: 2009 General Election. (Note: White shaded area indicates that the district has zero elected MPs with criminal background. Light Gray indicates less than or equal to half of the elected MPs with a criminal background whereas dark gray indicates districts with more than half of the MPs with criminal charges

To examine the correlation of a candidate’s criminal status with other observable characteristics, we next estimate regression models with either the winner or runner up candidate’s criminal status or the number of criminal cases against a winner or runner up candidate as the dependent variable and other candidate characteristics as explanatory variables. The results are presented in Table 1 Panel D. In columns 1 and 2 we estimate a regression model with criminal status as a dependent variable where the dummy variable, CRIMINAL is equal to one if a candidate has at least one pending criminal charge and is zero otherwise. The independent variables include dummy variables for college education, gender, minister rank, general category candidate (some constituencies are reserved for candidates from disadvantaged groups identified as Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribes), highly corrupt state (CORRUPT_STATE)Footnote 12 and for the 2009 election year. We also include logarithm of the candidate’s net assets as an additional explanatory variable. Across both specifications, we find that having a college education, being a woman, belonging to a national party, contesting from a reserved category seat or having a minister rank are negatively correlated with the likelihood of being a criminal candidate. Logarithm of net assets and belonging to a corrupt state are not significantly correlated with the likelihood of being a criminal candidate. In column 2, the coefficient for the dummy variable corresponding to election year 2009 is positive and significant which indicates that the proportion of criminal candidates went up between the election years 2004 and 2009. In column 3, we find similar results if we include the number of criminal cases as a dependent variable.

We get firm-level data from two databases managed by the Center for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE). The first database, CMIE Prowess, which is equivalent to Compustat and CRSP for Indian Firms, provides firm-level accounting variables, stock returns data and ownership structure for both private and publicly traded Indian firms. We obtain the capital expenditure data for the Indian firms from CMIE CapEx database. It includes the firm name/identifier, project date of announcement, cost, completion date and status of the project. CapEx database includes projects with cost of Indian Rupees 10 million or more announced by Indian firms or government since 1996. CapEx collects this information from publicly available sources, regulatory filings and by directly contacting firms. We also obtain the total district-level employment data for private-sector and state-owned firms from the Annual Survey of Industries (ASI) micro dataset. In particular, we use the web-based data analytic tool available on Indian Council of Social Sciences Research (ICSSR) website to obtain two snapshots of the ASI dataset: 2003–04 fiscal year and 2008–09 fiscal year. In Table 2, we report summary statistics of the firm-level and project variables for the close election sample corresponding to districts where a criminal politician wins or loses against a non-criminal candidate with a margin less than or equal to 5%. The number of observations (N) in Table 2 is the same as in the sample used for empirical tests in later sections. We report summary statistics for the private-sector firms and state-owned firms separately in Panel A and Panel B respectively.

As shown in Table 2, our close-election sample of private sector firms consists of 7,446 firm year observations from fiscal years 2004 to 2013 and the corresponding sample of state-owned firms consists of 163 firm-year observations. The private sector firms are on average smaller in size with median total assets of 1,105.8 million Indian Rupees (roughly USD 22 million at an exchange rate of 50 Indian Rupees/1 USD) compared to 27,663 million Indian rupees for the state-owned firms. The average change in firm stock market value around the election result announcement date as measured by the 3-day market-adjusted cumulative abnormal return is positive for the private sector firms (0.80%) and negative for the state-owned enterprises (-0.85%). For the project announcement analysis, we include projects with minimum cost or capital expenditure of 100 million Rupees (roughly USD 2 million). Our close-election sample includes 1022 capital expenditure projects announced by publicly-traded private-sector firms and 201 projects announced by the government majority-owned publicly traded firms during the 2004–2014 time period for which the election data is available. The mean cost of the private sector projects is 4,342 million Rupees compared to 25,293 million Rupees for the government owned firms. Around 10% of all private-sector projects in our sample are stalled or abandoned compared to around 6% for the government owned firms. We aggregate the total investment in a district in 5-year periods between the general elections (2004–2009 and 2009–2014) to examine the changes in aggregate district-level capital expenditure. The average total capital expenditure in a 5-year period across all districts in the country where a candidate with criminal background won or lost against a non-criminal candidate in a close election with win margin less than or equal to 5% is 79,065 million Indian Rupees (USD 1.6 billion) for private-sector firms and 44,369 million Indian Rupees (USD 887 million) for government-controlled firms. Much of the capital expenditure in a district (90% for investor-controlled firms and 95% for government-controlled firms) is undertaken by non-local firms, headquartered outside the district. In our analysis we examine the effect of election outcomes on non-local firms with strong economic ties to a district compared to those with weaker economic links. The mean of the total number of employees of private-sector firms in a district across fiscal years 2003–04 and 2008–09 is 32,109 whereas the corresponding number for state-owned firms is 3,244. Therefore, the mean of the number of employees in a district for private-sector firms is approximately ten times greater than the total employment in state owned firms whereas the total investment in a district by private sector firms is approximately only twice as much as the investment by state owned firms.

Empirical Results

Our empirical analysis focuses on the impact that the election of a criminal politician has on firm’s stock market performance, employment and investment decisions. We use several approaches to address the issue. We begin our empirical analysis by examining whether the criminal background of a locally elected politician affects firms’ stock market performance as measured by abnormal stock returns around the date that election results are announced. Next, we examine the effect of a criminal politician’s win on measures of firm stock market valuation (Tobin’s Q) and profitability (Return on Assets: ROA). Finally, we examine the stock price reaction to capital expenditure announcements, possibly indicative of the stock market’s perception regarding the marginal value of capital expenditure. There are potential endogeneity concerns about measuring the effect of a criminal politician’s win on firm stock market valuation and investment decisions. We address these concerns by focusing on close elections between a criminal and a non-criminal candidate where the election outcome can plausibly be treated as random or exogenous.

Evidence from Close Elections: Regression Discontinuity Design

In all our empirical tests, we use a regression discontinuity design (RDD) approach and focus on elections in which one of the two highest vote recipients is a criminal and the other is a non-criminal candidate – and the victory margin between the winner and runner-up is relatively small. We compare the stock market performance and investment decisions of firms in districts where a criminal politician defeats a non-criminal politician in a close election (CRIMINALWIN = 1) to firm’s stock market performance and investment where a non-criminal politician just defeats a criminal politician (CRIMINALWIN = 0). We define close elections as elections where the win margin between the winner and runner up is less than or equal to 3%, 5% or 10% of the overall vote following extant literature (Fisman et al., 2014).

We note that the application of RDD requires certain conditions to be satisfied (Imbens & Lemieux, 2008). A primary assumption behind the use of RDD is that in close elections, as in a randomized trial, criminal candidates are randomly assigned to the winner and runner-up groups. Election outcomes would not be random if, for instance, candidates could perfectly manipulate the outcome in close elections. To test for the validity of the random assignment assumption, we follow standard methodology to determine whether there is discontinuity or manipulation indicated around the cutoff point of zero vote share difference between criminal and non-criminal candidates.

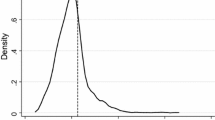

Figure 2, Panel A presents the distribution of vote share difference between criminal and non-criminal candidates for the 331 elections contested between a criminal and a non-criminal candidate: a positive vote share difference denotes a criminal win and negative vote difference corresponds to a non-criminal candidate victory. The distribution of vote share appears symmetric around the cutoff point of zero difference. To formally test for the presence of a jump in density of vote share difference at the cutoff point, we use the methodology from McCrary (2008). Figure 2 Panel B presents the smoothed density function of the vote share difference between the criminal and non-criminal candidates. We find that the magnitude of the jump in vote share at the cutoff point is insignificant with a p-value of 0.42, which validates the random assignment assumption behind the regression discontinuity design.

We next test the other two crucial assumptions to validate the application of Regression Discontinuity design. One assumption is that other covariates don’t change around the cutoff point. We test this assumption by examining the characteristics of criminals that won in a close election to those that lost narrowly. We also examine the characteristics of firms, districts and states associated with the electoral constituencies where the criminal candidate narrowly won compared to constituencies where the criminal candidate narrowly lost. To reliably estimate the effect of a criminal win, the two groups should be similar in every other observable aspect, save for the treatment effect i.e., winning or losing the election. The results are presented in Table 3. In Panel A, we compare criminal candidate characteristics for the sample of criminal candidates that either won or lost in a close election against a non-criminal candidate with a win margin less than or equal to 5%. We find the coefficient on CRIMINALWIN to be insignificant for all specifications. In Panel B, we compare the district, state and firm characteristics around the cutoff of zero vote difference between the criminal and non-criminal candidates. We find that the districts, states and firms associated with criminal candidates that narrowly won are similar to those in which criminal candidates narrowly lost along the following dimensions: district crime growth, state crime growth, state GDP growth, state literacy, state sex ratio, state corruption index, logarithm of assets, FII ownership and insider ownership. The coefficient corresponding to CRIMINALWIN is insignificant in all the specifications.

Finally, we test for the absence of discontinuity in outcome variables such as election return announcement returns and firm investment at cutoffs other than vote difference of 0%, we consider + 5% and -5% as alternative cutoff points, the outcome variable should be similar around these cutoffs since the criminal status of the winning candidate doesn’t change around these cutoffs. In Appendix Table 11, we find that, as expected, the outcome variables don’t exhibit a significant change around the cutoffs of + 5% and.

-5%. These three tests, taken together, validate the use of regression discontinuity design in our analysis and allow us to interpret the effects of a criminal candidate victory in causal terms.

Election Result Announcement Returns: Evidence from Close Elections

We begin our empirical analysis by examining whether the criminal background of local elected politicians affects the firm’s stock market performance as measured by the market-model adjusted cumulative abnormal return for a ± 1 day window around the election result announcement date. To calculate the market-model adjusted abnormal returns, we estimate the CAPM model by using S&P CNX 500 index as a proxy for Indian stock market returns. We use daily stock returns over last four quarters excluding the current quarter to estimate the market beta for each firm at the end of each quarter. The most recent beta estimate and raw stock returns during the election result announcement window are then used to estimate the cumulative abnormal returns around the election result announcement date.

We note that the use of a short-term window to measure the stock market reaction can raise legitimate concerns such as whether the average investor is likely to possess information about the election outcomes and their potential impact on a firm’s future value and performance. However, for stock prices to reflect investor information it is sufficient that some investors are informed and can trade in the market (e.g., Grossman & Stiglitz, 1980). For our setting, there will be shareholders such as the firm’s employees, managers and members of the founding family, large suppliers and customers among others that have a stake in the firm and will tend to pay close attention to the outcome of an election that can substantially impact the firm’s performance and value. We validate our findings in later sections of the paper by analyzing longer-term effects such as investment drop-off (Table 5), employment (Table 6) and firm performance and value (Table 7).

Our next step is to use the regression discontinuity approach to examine the causal effect of election of candidates with criminal background on the firm’s stock market performance. This methodology is similar to other papers in the literature that examine the causal effect of elections on economic outcomes (e.g., Chemin, 2012; Lee, 2008).Footnote 13 The results are presented in Table 4. In Panel A, the dependent variable is the market-model adjusted cumulative abnormal return for a 3-day window around the election result announcement date (CAR(−1, + 1)), which captures the change in the firm’s stock market value around the election result announcement. Our sample-period consists of days around election result announcement dates for the general elections in India held in 2004 and 2009 (May 13, 2004 and May 16, 2009). To determine the firms likely to be economically linked to a district, we estimate a variable PCTPROJECT which is calculated as a firm’s capital expenditures in the district as a percentage of its total capital expenditures in the 5 years prior to a general election. PCTPROJECT is zero for a firm and district pair if a firm has not announced any capital project in that district in past 5 years. Further, we classify a firm as LOCAL or NON-LOCAL based on whether the firm is headquartered in a given district or not. We focus on three sets of firms: Local Firms with PCTPROJECT = 0, Local Firms with PCTPROJECT > 0 and non-local firms with PCTPROJECT > 0. We would expect local firms with PCTPROJECT > 0 to be most closely connected to the district.

In column 1, the coefficient corresponding to CRIMINALWIN is insignificant for local firms with no capital projects in their district in last 5 years. These firms are unaffected by a criminal win. In column 2, we focus on local firms with non-zero investment in last 5 years. The coefficient corresponding to CRIMINALWIN is negative and highly significant. For these firms, the three-day election result announcement returns indicate that a narrow criminal victory (compared to a narrow loss) results in a loss of 8.00% of total stock market capitalization. In column 3, the sample includes non-local firms that had invested in the last 5 years in a district where a criminal candidate contested against a non-criminal candidate in a close election. For these firms, the win by a criminal politician leads to a loss of 3.50% of total market capitalization. The lower impact on non-local firms is consistent with a lower investment stake in the district, compared to local firms that are headquartered in the district. In column 4, we examine the combined effect on both local and non-local firms with non-zero past investment in that districts. The average effect of the criminal winning in a close election is -3.70% of the stock market value of the firms. In columns 1–4, we include district fixed effects to control for unobserved, time-invariant heterogeneity across districts. In column 5, we replicate the regression in column 4 using state fixed effects instead of district fixed effects and obtain similar results.

In Columns 6 and 7 we consider the election announcement effect on state-owned firms. Unlike privately owned companies, a criminal politician win has no significant effect on the stock market performance of state-owned firms that are economically connected to the district with positive past investments. This suggests either that criminal politicians are unable to directly extract resources from state-owned firms or, more likely, that extraction of benefits is offset by actions favorable to SOEs. As we discuss later, these politicians seem adept at getting SOEs to invest in their districts.

In Fig. 3 Panel A, we present a regression-discontinuity plot to illustrate the discontinuity or jump in election announcement returns conditional on a criminal candidate win. Our sample includes the local and non-local firms with non-zero past investment in the districts where a criminal candidate contested against a non-criminal candidate in a close election. We plot the average election result announcements CAR(−1, + 1) in each of the win margin bins, after controlling for the covariates as in column 4 of Table 4, Panel A, where positive (negative) values of win margin denote a criminal win (loss). As shown in the figure, election announcement returns are lower if a criminal candidate wins: a clear discontinuity can be seen at win margin equal to 0.

In Table 4 Panel B, to rule out the possibility that CRIMINALWIN might be capturing other observable state or district characteristics, we show that our results are robust to including additional state and district level control variables. These variables are state GDP growth, state crime growth, state literacy, state sex ratio and district crime growth.

For regression models in columns 1–4 (columns 5–6) the sample is that of private-sector (state-owned) firms with non-zero investment in past 5 years in the district. We report regression results for samples with win margin less than or equal to 3%, 5% and 10%, in addition to ones with the full sample of firms (i.e., all). In column 1, for the sample including all election outcomes, we find that the coefficient on CRIMINALWIN is negative but not statistically significant after controlling for state and district-level controls. In columns 2–4, the coefficient on CRIMINALWIN is negative and highly significant for the close-election samples with different win margin bandwidths. For example, in column 3, for the sample with win margin less than or equal to 5%, the difference in the election result announcement returns where a criminal candidate won compared to districts where a criminal candidate lost is -1.80% with a p-value of 0.03. In columns 5 and 6, our sample consists of state-owned firms with non-zero investment in the given district. In line with Panel A results, the coefficients corresponding to CRIMINALWIN are insignificant, indicating that the value of state-owned firms is unaffected by the election of a criminal candidate.

In Table 4 Panel C, we examine the effect of candidate incumbency and state-level corruption on election result announcement returns for firms with past investments in the district. We include district fixed effects in all specifications. In the first column, we find that the effect of criminal win on election announcement returns is more negative in districts located in more corrupt states as proxied by an above median score on the Transparency International corruption index. The coefficient corresponding to the interaction term between the indicator variable for states with above median score on the corruption index and CRIMINALWIN is negative (-0.053) and highly significant (p-value < 0.00001). Therefore, the coefficient on CRIMINALWIN is lower for firms based in states with above average level of corruption. Alternatively, in columns 2–3, we divide the sample into two groups based on the median score on the corruption index. The results show that the coefficient on CRIMINALWIN is negative and significant for elections in states with above median state corruption index. The difference in the magnitude of coefficients on CRIMINALWIN between the two groups is also negative and significant (p-value < 0.00001). This is consistent with criminal politicians having greater ability to extract rents in states with a poor law and order situation and widespread corruption.

In column 4, we find that the coefficient on the interaction between CRIMINALWIN and CRIMINAL_INCUMBENT (indicator variable which is equal to 1 if the criminal candidate is an incumbent and 0 otherwise) is negative and highly significant. This indicates that the coefficient on CRIMINALWIN is lower when the criminal candidate is also an incumbent. To provide further evidence, in columns 5–6 we estimate the CRIMINALWIN coefficient separately for the incumbent and non-incumbent sub-samples. The coefficient for CRIMINALWIN is negative and significant only for the incumbent sample (p-value < 0.0001) and is insignificant for the non-incumbent sample (p-value = 0.36). The difference is also negative and significant with a p-value < 0.0001. These results are consistent with the notion that incumbent criminal candidates are likely to be senior and more influential in their districts and, hence, could affect economic outcomes to a greater extent than non-incumbent candidates.

Criminal Politicians: Effect on Investment and Employment

We next turn to the question of whether the election of criminal politicians affects the pattern of corporate investment and employment in the district.

Aggregate Private Sector Investment in Districts: Evidence from Close Elections

We compare the total dollar investment in the five years before and after the election in districts in which a criminal candidate narrowly won to those in which the criminal candidate narrowly lost. Univariate results for aggregate investment in districts by private-sector firms are presented in Panel A of Table 5. As indicated, if the criminal candidate wins in a close election with a win margin less than or equal to 5%, this leads to a reduction in the 5-year investment level in the district by 33,219.0 million Indian Rupees (roughly 664.4 million USD at an exchange rate of 1 USD = 50 Indian Rupees), compared to 5 years before the election. On the other hand, if the criminal candidate loses in a close election, this leads to an increase in total investment in the district by 24,405.1 million Indian Rupees. The difference in investment growth between the districts in which a criminal narrowly lost versus won is 57,624.1 million Indian rupees (USD 1.15 billion), an economically large effect. Therefore, the election win (loss) of criminal politicians leads to a sharp reduction (increase) in investment by private sector firms.

As shown in the second and third columns of Table 5 Panel A, the reduction in investment when the criminal candidate wins is much larger for non-local firms compared to local firms. This could indicate that local firms, in particular smaller firms that are not geographically diversified may be forced to locate a substantial proportion of their new investment locally, regardless of the political environment in their local district. On the other hand, the non-local investment tends to be by larger firms that have greater ability to locate their investment away from a district with a criminal member of parliament. The results are similar in Columns 4–6 for the alternative 10% win margin definition for a close election.

In Table 5 Panel B, we examine the changes in investment using pooled regressions with state fixed effects or state and district controls. The dependent variable is one of the following: Change in total project cost for all, local, non-local firms investing in the district, standardized within sample to mean 0 and standard deviation of 1. We focus on private sector firms and include the districts where a criminal candidate contested against a non-criminal candidate and the outcome was determined in a close election with win margin of either less than or equal to 5% or 10% of all votes polled. The main independent variable is CRIMINALWIN. The results are similar to the univariate results: criminal politicians’ win leads to a sharp decrease in investment. The coefficient on CRIMINALWIN remains similar and significant in column 2 if instead of state fixed effects, we include the following state and district level controls: state GDP growth, state crime growth, state literacy, state sex ratio and district crime growth. In Fig. 3 Panel B, we present a regression-discontinuity plot to illustrate the discontinuity or jump in private-sector investment following a criminal candidate win. As shown in the figure, the private sector investment in a district drops if a criminal candidate wins (denoted by positive win margin) in that district.

In Table 5 Panel C, we examine whether the effect of a criminal candidate win is more negative on district-level investments if the criminal candidate is also an incumbent or if the state in which the district is located is regarded as more corrupt in general. In column 1, the interaction term between CRIMINALWIN and CORRUPT_STATE (dummy variable equal to 1 if the state is ranked above median by the 2005 Corruption Study by Transparency International India and 0 otherwise) is negative and significant (p-value = 0.002). In columns 2–3, we divide the sample into two groups based on the median score on the corruption index. The results show that the coefficient on CRIMINALWIN is negative and significant for elections in states with above median state corruption index. The difference in the magnitude of coefficients on CRIMINALWIN between the two groups is also negative and significant (p-value = 0.026). Therefore, consistent with our earlier results, private-sector firms are also more likely to reduce capital expenditure following a criminal candidate win if the project is located in a corrupt state. In column 4, we include the interaction between dummy variables corresponding to a criminal win and to whether the candidate is also an incumbent: CRIMINAL_INCUMBENT (equals 1 if the criminal candidate is also an incumbent and 0 otherwise). For private sector firms, we find that the coefficient corresponding to an interaction between CRIMINALWIN and CRIMINAL_INCUMBENT is negative and significant with a p-value of 0.025. Further, in columns 5–6 we estimate the CRIMINALWIN coefficient separately for the incumbent and non-incumbent sub-samples. The coefficient for CRIMINALWIN is negative and significant only for the incumbent sample (p-value = 0.004) and is insignificant for the non-incumbent sample (p-value = 0.70). The difference is also negative and significant with a p-value of 0.006. Hence, the negative effect of a criminal candidate win is largely driven by incumbent criminal candidates, consistent with the notion that they are likely to be more powerful and have greater influence on the outcome of investment projects located in their districts.

Aggregate Investment by State-Owned Firms in Districts: Evidence from Close Elections

In Panel D Table 5, we examine the effect of a criminal politician win on investment by state-owned firms.Footnote 14 If the criminal candidate wins in a close election, this leads to an increase in total investment in the district of 17,191.2 million Indian Rupees (roughly 343.8 million USD) in the next 5 years compared to the 5 years prior to the election. If the criminal candidate loses in a close election, this leads to a decrease in total investment in the district by 17,722.6 million Indian Rupees. The difference of change in investment between the districts where a criminal narrowly won or lost is 34,913.8 million Indian rupees (USD 698.3 million). Therefore, in sharp contrast to private sector firms, the election of criminal politicians leads to a substantial increase in investment by state-owned firms. Hence, corrupt politicians appear to be able to substantially offset the loss in investment by private-sector firms with investment by state-owned enterprises. This is an intriguing result since it sheds some light on why criminal politicians may be able to win, despite causing private sector firms to drastically reduce their investment. It appears that by inducing investment by state-owned firms, the criminal politicians may be able to provide employment and other favors to their supporters and retain their loyalty.

In columns 3 and 4, we examine the effect of a criminal win on changes in total capital expenditure in the district including both private and state-owned enterprises. The average change in capital expenditure if the criminal narrowly wins is negative but insignificant (p-value = 0.46) and change in capital expenditure if the criminal narrowly loses is positive but again insignificant (p-value = 0.88). The difference is also insignificant with a p-value of 0.56. Therefore, there does not appear to be a significant decrease in the overall investment level, though there is substitution between private and state-sector investment.

Effects on Employment: Evidence from Close Elections

As discussed above, private sector firms sharply cut investment in districts where the criminal politicians are elected, though this reduction in investment is largely balanced by the increase in investment by state-owned firms. In this section, we examine the effect of a criminal politician win on the employment by state owned and private sector firms. We obtain total district-level employment data for private-sector and state-owned firms from the Annual Survey of Industries (ASI) micro dataset. In particular, we obtain the data for two snapshots: 2003–04 fiscal year and 2008–09 fiscal year. This allows us to analyze employment effects for the first half of our sample (2004 election).Footnote 15

The results are presented in Table 6. The dependent variable is the change in log of total number of employees in a district for private sector (columns 1–3), for state owned (columns 4–6) and for all firms (columns 7–9). The main independent variable is CRIMINALWIN, which is equal to 1 if the criminal candidate won and 0 otherwise. In column 1, we present results for all win margins and in columns 2 and 3 our focus is on close elections with win margins of 10%, and 5%. In columns 1–3, the coefficient corresponding to CRIMINALWIN for private sector firms is negative and significant, which suggests that the employment growth for private sector firms headquartered in a district where a criminal politician won against a non-criminal politician is lower in the post-election five-year period compared to districts where the criminal politician lost. These results are consistent with the decrease in investment by private sector firms after a criminal politician win as documented in Table 5.

The coefficient corresponding to CRIMINALWIN is positive or insignificant for the state-owned firms as documented in columns 4–6 of Table 6. The results for close elections indicate that the election of criminal politicians does not significantly affect the employment growth for state-owned firms in their districts. In columns 7–9, we present results for employment for all firms. The coefficient corresponding to CRIMINALWIN is negative, though not always significant. Overall, criminal politicians appear to have a negative effect on aggregate employment growth in their district. Hence, while the investment in state-owned-firms and private sector firms is roughly offsetting, the employment is not. Despite the drop in overall employment, it is possible that criminal politicians can provide favors other than employment to their supporters, such as favorable business opportunities related to the increase in investment by state-owned firms.

Q and ROA Regressions

In this section, we use Tobin’s Q and Return on Assets (ROA) as measures of firm performance. In Table 7 Panel A, we focus on close elections and follow a difference-in-difference approach to provide evidence on the effect of criminal politicians on the following measures of firm performance: firm valuation (Tobin’s Q) and profitability (ROA). We estimate panel regressions with either Tobin’s Q or ROA as the dependent variable. We control for industry by including industry fixed effects (industry is defined by 2-digit National Industry Classification (NIC) codes). We also include district, industry and year fixed effects to control for unobserved heterogeneity. In columns 1, 2, 5, and 6, we include district and state-level control variables instead of district fixed effects. Our sample includes firm-year observations of firms headquartered in districts where a criminal candidate contests a non-criminal candidate in a close election. CRIMINALWIN = 1 if the criminal candidate won and is 0 otherwise. We define, POST = 1 for four fiscal years after the election and POST = 0 for four fiscal years before the election. For example, for close elections in year 2009, we include firm years from fiscal year 2006–2013: POST = 0 for observations in year 2006–2009 and POST = 1 for observations from 2010 to 2013. We follow the same procedure to label firm years as pre or post for close elections in 2004. Therefore, the coefficient on the POST variable captures the change in Q or ROA in the four years after the election compared to the four years before the close election. Our main variable of interest is the interaction term between POST and CRIMINALWIN that captures the impact on Q or ROA conditional on a criminal candidate winning or losing.

In columns 1–4, our sample is that of close elections with win margin less than or equal to 3%. Tobin’s Q is the dependent variable in column 1. As indicated, the coefficient corresponding to the interaction between POST and CRIMINALWIN is negative and significant, indicating that a criminal win leads to a drop in firm valuation as measured by the Q-ratio. In column 2, using ROA as the dependent variable we obtain similar results. The average difference in industry adjusted ROA in the four-year period before and after a criminal wins against a non-criminal is an economically significant -1.7%. In columns 3 and 4, instead of the district and state-level controls, we include district fixed effects. The coefficient on CRIMINALWIN*POST remains similar in magnitude and significance. Results are similar in magnitude but weaker in significance in columns 5–8 for close elections with win margin less than or equal to 5%.Footnote 16

In Table 7 Panel B, we examine the effect of criminal win on valuation and profitability of state-owned firms. In columns 1–4, we find that the effect of a criminal win on the valuation and profitability of state-owned firms is insignificant. This is consistent with the results in Table 4 where we find no effect of a criminal win on the valuation of state-owned firms measured using their cumulative abnormal returns around the election result announcement dates.

Finally, in Table 7 Panel C, we examine the effect of CRIMINALWIN on firm performance based on whether the corruption index of the state is above or below median and whether the criminal politician is an incumbent or non-incumbent. We follow the same methodology as in Table 7 Panel A and the dependent variable is either Tobin’s Q as a measure of firm’s stock market value or Return on Assets (ROA) to measure firm profitability. We also include industry, year and district fixed effects. In columns 1–4, we divide the sample into two groups based on the dummy variable CORRUPT_STATE. The CORRUPT_STATE variable is 1 for firms headquartered in states with an above median score on the 2005 Transparency International India state-level corruption study and 0 otherwise. We find that both for Q and ROA regressions, the coefficient on the interaction term POST and CRIMINALWIN is negative and highly significant only for the high CORRUPT_STATE sample. This shows that the effect of CRIMINALWIN on stock market value and profitability is evident mainly for firms headquartered in states with an above average overall corruption score. This is consistent with earlier results that the negative effect of criminal politicians on private sector economic activity is far worse in the more corrupt states. In columns 5–8, we divide the sample into two groups conditional on the dummy variable CRIMINAL_INCUMBENT, which is equal to 1 if the criminal candidate is also an incumbent and 0 otherwise. In columns 5–6, for the Q regressions, we find that the interaction term between POST, CRIMINALWIN is negative and significant only for the CRIMINAL_INCUMBENT = 1 group, which indicates that the effect of a criminal politician win on firm’s stock market value is stronger for incumbent criminal candidates. For the ROA regressions in columns 7–8, we don’t find any significant difference between incumbent and non-incumbent criminal candidates. This could suggest, for instance, that incumbent corrupt politicians may be expected to have a longer-term value effect on firm growth, rather than on short-term firm profitability.

Criminal Politicians and Project Announcement Returns

Next, we examine whether the criminal background of locally elected politicians affects project or capital expenditure announcement returns. Project announcement returns capture the marginal effect of a new capital expenditure decision on the firm’s stock market performance. We use the market model adjusted cumulative abnormal return (CAR) for a ± 1 day window around the project announcement date to measure the project announcement abnormal returns. As described earlier, we use S&P CNX 500 index as a proxy for Indian stock market returns and estimate the CAPM market beta for each firm at the end of each quarter. We then use the most recent beta estimate and raw stock returns during the project announcement window to estimate the cumulative abnormal returns around each project announcement.

For the sample of private sector firms, we first illustrate the discontinuity or jump in project announcement returns conditional on a criminal win using a regression-discontinuity plot in Fig. 3 Panel C. As before, win margin is the difference in vote share between the criminal and non-criminal candidates. Positive win margins indicate a criminal win and negative win margins indicate a non-criminal win. We plot the average 3-day market-model adjusted cumulative adjusted returns in each of the 10 win-margin bins for projects announced by all private-sector firms. We plot the returns after controlling for industry, district and year fixed effects, similar to specification 5 in Table 8 Panel A.Footnote 17

In Table 8, we focus on samples of private-sector and state-owned firms and use pooled regressions to examine project announcement returns for close elections. The dependent variable is the three-day cumulative market-model adjusted abnormal return (CAR(−1, + 1)) around the project announcement date. In multivariate regressions, we control for Industry, District and Year fixed effects. We report the t-statistic obtained from standard errors clustered by district and election year. In columns 1–4 of Table 8 Panel A, close elections are defined to have a win margin less than or equal to 5% of all votes polled. In columns 5–8, the cutoff for close elections is 10%. Column 9 includes all observations. In the first column of Table 8 Panel A, the coefficient corresponding to CRIMINALWIN is negative and significant (p-value = 0.05). The difference in returns between projects announced in districts where the criminal candidate narrowly won (margin \(\le \) 5%), compared to the districts where the criminal candidate narrowly lost is -0.90%. We estimate the regressions separately for projects announced by local and non-local firms. The coefficient of CRIMINALWIN for local firms is statistically insignificant (column 2). For NON-LOCAL firms, however, the coefficient indicates that the announcement return is 1.20% lower (significant with p-value = 0.05) in districts where a criminal candidate narrowly won (column 3). The coefficients corresponding to CRIMINALWIN are similar in sign and significance for specifications including district fixed effects in larger samples corresponding to a win margin of 10% (column 5–7) or all win margins (column 9).

In columns 4 and 8, our sample includes projects announced by state-owned firms. In column 4 (column 8), we include projects where elections between candidates with criminal and non-criminal backgrounds are decided by a win margin of less than or equal to 5% (10%). The coefficients corresponding to CRIMINALWIN are insignificant in both column 4 and 8. Consistent with earlier findings on election announcement returns, the value of the projects announced by state-owned firms seems to be unaffected by the election of a criminal candidate.

In Table 8 Panel B, we examine the effect of the overall corruption in the state and incumbent status of the criminal candidate on project announcement returns. Our sample includes all projects located in districts where the criminal-noncriminal win margin is less than or equal to 5%. To measure the effect of overall corruption in the state, we include a dummy variable, CORRUPT_STATE which is equal to 1 if the state is ranked above median by the 2005 Corruption Study by Transparency International India and 0 otherwise. In column 1, the interaction between CORRUPT_STATE and CRIMINALWIN is negative and highly significant with a p-value of < 0.0001. Consistent with the previous findings, the result indicates that criminal politicians have a more negative impact on private-sector firms in more corrupt states. In column 4, we find that the variables corresponding to the interaction between dummy variables for whether the candidate is also an incumbent is insignificant. In columns 2–3 and 5–6, we report results for separate subsamples divided by above or below median state corruption or by the incumbent status of the criminal candidate.

Additional Results and Robustness

Evidence from Asset Increases: An Alternative Measure of Corruption

As a robustness check, we examine the effect of corrupt politicians on economic activity based upon an alternative measure of corruption calculated from the increase in the disclosed net assets (assets-liabilities) of the re-contesting incumbent candidates during their previous term in office (Fisman et al. (2014)). According to this alternative definition, we define a candidate to be corrupt if the increase in their net assets is greater than 200% during the 5-year period when they were in office and non-corrupt if the increase is less than 200%. We use 200% as a cutoff because it gives us a similar proportion of corrupt candidates (around one-third of all candidates) as our previous definition based on pending criminal cases. All our results are robust to using alternative cutoffs e.g., 150% and 250%.

For our tests, we first compare the asset disclosures of the candidates in 2004 and 2009 to determine if a re-contesting candidate is likely to be corrupt or not. We then use this definition of corruption to examine the effect of the election outcome on the firm’s stock market performance and on total investments between 2009 and 2014. Since, by construction, the asset-growth based definition of corruption is available only for the second half of the sample and for incumbent candidates, this reduces the sample considerably. In Table 9 Panel A, we examine the relation between the percentage net asset increase of politicians while they are in office with a dummy variable (CRIMINAL) which is equal to 1 if the politicians also have a pending criminal case against them and 0 otherwise. The dependent variable is percentage net asset increase during the five years when the politician was in office. In column 1, we find that the coefficient corresponding to CRIMINAL is positive but insignificant which suggests that overall the correlation between the presence of criminal background and net asset increase while in office is low. In column 2, 3 we also include the interaction term between CRIMINAL and a proxy for corrupt state. In column 2, we find that coefficient for the interaction term between CRIMINAL and corrupt state dummy variable (states with above median corruption index) is positive and significant which indicates that in the most corrupt states, the percentage asset increase is positively correlated with having a criminal background. The results are similar if we use an indicator variable for the most corrupt BIMAROU (Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Orissa and Uttar Pradesh) states as an alternative proxy for a corrupt state. These results validate our use of the existence of a criminal case to identify corrupt politicians particularly in the most corrupt states.

Next, using this alternative asset-based definition of corrupt politicians we examine the effect of the election of corrupt politicians on economic outcomes. Results are presented in Table 9 Panel B and Panel C. In columns 1–3 of Table 9 Panel B, we examine the effect of election of corrupt candidates on the election announcement returns for the firms economically tied to the district. For firms economically linked to a district, we find that the 3-day cumulative abnormal return around the announcement of election results is -4.60% lower (p-value = 0.0005) when the corrupt candidate wins in a close election compared to districts where the corrupt candidate loses a close election. In columns 4–6, we examine the effect of a corrupt candidate win on the abnormal returns around future project announcements. In column 4, we find that the 3-day cumulative abnormal return around future project announcement dates in the 5-year period leading to the next election is -3.60% lower (p-value = 0.0006) when the corrupt candidate wins in a close election compared to districts where the corrupt candidate loses a close election. In Panel C, we report the effect of the. election of corrupt candidates on total investments in a district. In column 2, for close elections with win margin of 10% or less, we find that the election of corrupt politicians leads to a decrease in investment by 94.66 bn Indian Rupees ($1.89 bn), which is highly significant with a p-value of 0.003. The difference between average investments in districts where a corrupt politician won compared to where a corrupt politician lost is -$1.66 bn, which is also significant with a p-value of 0.04. In columns 3 and 4, we find a decrease in investment by state-owned firms in districts where a criminal candidate just lost, but the change is not statistically significant. Given the similarity in economic magnitude to our earlier findings, the statistical insignificance is likely due to the much smaller sample size when the asset-growth corruption measure used.

Therefore, for the asset-increase based measure of corrupt politicians, we find that the effects are similar in magnitude and sign to the findings based on the criminal background of candidates. However, given the considerably smaller sample, the results are noisier and statistically insignificant in some cases.

Additional Results

We examine the possibility that the criminal charges against politicians may be politically timed to influence the election. Results (Internet Appendix Table 4) suggest that criminal charges are not politically timed. In fact, we find economic effects are stronger when the politicians are charged for crimes that have been more recently committed.

Further, we examine the implications of the nature of the crime (violent or non-violent) that the politicians are charged with having committed, for our results. While violent crimes such as murder are more serious in nature, they may have a weaker correlation with economic corruption. The results are presented in Internet Appendix Table 5. Based on close elections, our results indicate that for new investments, stock market reaction to new projects and election outcomes, the economic impact of non-violent criminal politicians is much greater than that of politicians charged with violent crimes. We also find (untabulated) that a criminal win has a negative, but statistically insignificant, effect on project announcement returns, election announcement returns and investments of neighboring district firms.

In addition, we analyze whether the effect of elections in which the winning candidate represents a switch from a criminal to non-criminal (or vice versa) member of parliament is explained by changes in political affiliation of winning candidates. We present results corresponding to the 150 firm observations from the 2009 election year in which there is a change (from the 2004 election year) in the criminal status of the winning candidate, with no change in political affiliation. The results are provided in Internet Appendix 6. Overall, the results are similar in magnitude to those reported in the paper, though statistical significance is somewhat weaker given the smaller sample size. These results indicate that our findings are unlikely to be fully explained by changes in political affiliation of the winning candidate.Footnote 18

To examine a possible mechanism for our results, we test the effect of a criminal politician win on the growth rate of crime in their district. The results are in Appendix Table 12. The observations with PRE = 0 include the average annual crime growth in a district in the election year and the two years in the post-election period, while the observations with PRE = 1 include the annual crime growth in a district in the two years prior to the election. In columns 1–3, the dependent variable is the average growth in all categories of crimes over the pre- and post-election periods. In column 1 for all elections, we find that the coefficient on the interaction between CRIMINALWIN and PRE is negative and significant, while the unconditional coefficient on CRIMINALWIN is positive and significant. As indicated, the coefficient on CRIMINALWIN is positive and significant only for the post-election period (PRE = 0) and is close to zero for the pre-election (PRE = 1) period. In column 2, we find similar results for elections with win margin less than 10%, though the co-efficient on the post-election period is not significant at conventional levels. The results are noisy and insignificant for the elections in districts with win margin less than 5%. In columns 4–11, we focus separately on the following categories of crimes: crimes against body, crimes against public order and property (we combine the crime against public order and crime against property in the same category), economic crimes and crimes against women and children. The coefficients on CRIMINALWIN and on the interaction between CRIMINALWIN and PRE are significant only for crimes against public order and property (columns 6 and 7). These crime categories include crimes such as riots and arson that can disrupt economic activity in the district and hence could partly explain the reduction in investments and lower firm valuations that we find in our results.

Discussion and Concluding Remarks

In the paper we find that the election of criminal/corrupt politicians has a negative impact on the stock market values and investments of private-sector corporations. This is likely to negatively impact economic growth and employment opportunities in the districts of corrupt politicians. A question that arises is how corrupt politicians manage to get elected – if they have large negative economic effects on their districts? Our findings suggest that corrupt politicians may be especially adept at bringing in investments by state-controlled corporations. The magnitude of investments by state owned enterprises appears to largely offset the decrease in investment by private-sector firms. This shift from private investment to state-sector investment is often associated with corruption in other countries as well (e.g., Nguyen et al. (2012)). At the same time corrupt politicians do not appear to offset employment losses in private sector firms with greater employment in state owned firms.

Private-sector firms with headquarters and investment projects in the district are especially vulnerable to the election of corrupt politicians. Rather than supporting local firms, corrupt politicians appear to extract more value from local firms. Further, negative consequences for private-sector firms are more severe in districts narrowly won by corrupt politicians that are incumbents and, hence, are likely to be senior and more influential in their districts. The economic consequences of narrow wins by corrupt politicians are also more adverse for private-sector firms when their districts are in states with higher levels of corruption.