Abstract

Political corruption imposes substantial costs on shareholders in the U.S. Yet, we understand little about the basic factors that exacerbate or mitigate the value consequences of political corruption. Using federal corruption convictions data, we find that firm-level economic rents and monitoring mechanisms moderate the negative relation between corruption and firm value. The value consequences of political corruption are exacerbated for firms operating in low-rent product markets and mitigated for firms subject to external monitoring by state governments or monitoring induced by disclosure transparency. Our results should inform managers and policymakers of the tradeoffs imposed on firms operating in politically corrupt districts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

We study the relation between political corruption and firm value in the United States (U.S.). Despite the intuitive relation between corruption and value, and substantial media coverage of corruption, bribery, and other unethical acts by public officials in the U.S., there is scant empirical evidence on the effects of domestic corruption on firm value. An exception is Dass et al. (2016), who use Department of Justice (DOJ) data on political corruption convictions in the U.S. District Court system to document that corruption destroys value for the average U.S. firm. Yet, little is understood about the basic factors that moderate the costs of political corruption for U.S. firms. Our research fills this gap by examining the role of economic rents and monitoring mechanisms on the value consequences of political corruption.

While the U.S. traditionally ranks as a low-corruption country on international corruption indices, the number of corruption convictions at the U.S. District Court level is striking and indicates wide variations in political corruption both within and across the American states. This evidence highlights that corruption is not just an emerging markets problem and that abuses of public office in developed nations are often obscured in cross-country studies based on national corruption indices (Johan and Najar 2010; Cumming et al. 2016). The volume of corruption convictions is also notable as it points to remarkably high instances of political corruption and unethical behavior despite widespread condemnation of such acts. Thus, consistent with the arguments in Collins et al. (2009), it appears that corrupt acts, even when acknowledged as unethical, can be seen as “the way things are done” and can readily become an unwritten rule of conducting business in certain areas within the U.S.

The first step in our investigation of corruption and U.S. firm value is to confirm whether the negative relation between them, as documented in Dass et al. (2016), exists in our sample. Our main purpose, however, is to investigate whether the negative effect of corruption on firm value is attenuated by two fundamental factors established in the literature that may constrain the effects of corruption: (1) the magnitude of economic rents available for expropriation and (2) monitoring mechanisms (both at the firm and state levels).

The economic effects and ethicality of political corruption are widely discussed in prior research spanning several disciplines. Consistent with these streams of literature, we define political corruption as the misuse of public office by government officials for their private gain (Leff 1964; Rose-Ackerman 1975; Shleifer and Vishny 1993; Lindgreen 2004).Footnote 1 This definition is consistent with the legal elements of public corruption offenses routinely investigated and prosecuted by the U.S. DOJ. Similar to prior studies (Glaeser and Saks 2006; Butler et al. 2009; Campante and Do 2014; Dass et al. 2016), we use annual DOJ data on the number of public corruption convictions within each U.S. District Court district to capture underlying corruption around a firm’s headquarters.Footnote 2 We then use this district-level corruption proxy to examine the effect of corruption on firm value and the moderating role of economic rents and monitoring.

We find that firm value is negatively related to the level of political corruption within a firm’s operating environment, consistent with the evidence in Dass et al. (2016). Moreover, the relation is economically significant—a one standard deviation increase in political corruption is associated with a $7.6 million reduction in firm value (about 4%) for the median firm in our sample.Footnote 3 The economic magnitude of this result suggests that political corruption is an important determinant of firm value even in developed economies such as the U.S.

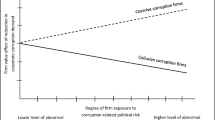

The results from our moderating tests provide novel insights into the costs of corruption for U.S. firms. Using industry competition as a proxy for economic rents available for expropriation, we find that the negative relation between firm value and corruption exists primarily in competitive product markets. So, while some theories predict that political corruption is more widespread in less competitive industries (because these firms likely earn higher rents), our evidence suggests that firms in competitive industries are less able to fend off the costs of political malfeasance. This finding is noteworthy as it suggests that U.S. shareholders bear much of the burdens of corruption in competitive markets. Thus, to the extent that firms in these markets are operating on tighter margins and with less slack, then any amount of rent-seeking is a deadweight loss to shareholders.

Our next set of analyses evaluates the role of monitoring mechanisms on the corruption–value relation. We focus on three different aspects of monitoring at the firm level: anti-takeover and entrenching provisions, auditor quality, and disclosure transparency. We find that a relatively low number of anti-takeover and entrenching provisions in the corporate charter—a common proxy for strong corporate governance—does not moderate the relation between firm value and corruption, contrary to conventional thought.Footnote 4 Auditor quality, a widely used proxy of strong external monitoring, appears to exacerbate the costs of corruption. Specifically, firms operating in corrupt environments exhibit lower values when they engage a high-quality auditor. This evidence is in line with arguments that strong audit monitoring can restrict managerial collusion and information sharing with government officials that would otherwise benefit the firm (see, e.g., Hope et al. 2008; Wang et al. 2008). The result could also reflect the paradoxical effect of information transparency when firms operate in corrupt environments (Kolstad and Wiig 2009). That is, high-quality audits could limit firms’ ability to shield their financial results from rent-seeking public officials.

Our last firm-level proxy focuses on information transparency as a potential monitoring mechanism. We use the issuance of management earnings guidance and Form 8-K voluntary releases to capture disclosure transparency. The corruption literature views transparency as central to curbing corruption-related problems, though transparency can exacerbate these problems in certain cases (Kolstad and Wiig 2009). For instance, transparency at the firm level can facilitate monitoring by external parties such as investors and the business press; however, it can make it easier for corrupt officials to identify and extort firm rents. Consistent with using opacity to shield rents, previous work finds that transparency is lower among firms operating in corrupt environments (Durnev and Fauver 2011; Dass et al. 2016).

We build on this work by examining whether shareholders benefit from shielding behaviors, or whether the increased information asymmetry between firm insiders and outside investors further reduces value. Interestingly, we find that disclosure is more valuable to firms operating in corrupt areas. This evidence follows from theory predicting that voluntary disclosures are more likely to occur when the benefits outweigh the costs (Healy and Palepu 2001). Thus, the monitoring benefits of disclosure seem to outweigh the risks of possible expropriation for certain firms in corrupt districts. These results stand in contrast to our audit monitoring results, and might suggest that while firms can maximize the value of voluntary disclosure in corrupt areas, mandatory disclosures (or those prompted by mandatory audits) can be detrimental to value.

Finally, we examine how government-level monitoring moderates the negative effects of corruption on firm value. We follow prior corruption research and use split party control within state governments as a proxy of public monitoring (Nice 1983; Meier and Holbrook 1992). We classify states in which one political party controls the state legislature as having less government monitoring relative to states with split party control. We find novel evidence that the value-destroying effects of political corruption manifest only when party power is unified within a state. Thus, it appears that some level of public monitoring occurs when state governments are divided, consistent with arguments that party competition constrains corruption.

Our study contributes to the literature on the economic effects of political corruption and unethical business practices. Using event studies, Zeume (2017) and Borisov et al. (2016) find a decline in firm value following shocks that limit corrupting influences in the U.K. and the U.S., respectively.Footnote 5 Thus, some firms seem to benefit from corrupt practices even in developed nations. More broadly, Dass et al. (2016) use corruption convictions data and find that political corruption negatively affects value for the average U.S. firm. Our results extend this burgeoning line of research by examining how the negative relation between corruption and value varies with firm-level monitoring and economic rents. We find that, while corruption is damaging to firms in low-rent markets, external monitoring is an important mitigating factor. Specifically, we demonstrate that opposing party monitoring plays an important role in abating the negative value effects of corruption. Moreover, we document that firms operating in corrupt districts extract more value from voluntarily disclosing information to external parties who are likely to act as monitors. This new result is important as it suggests that firms appropriately consider the benefits and costs of information transparency when operating in corrupt environments.

Our study has several implications for business and public policy. Our evidence on the moderating effects of firm- and government-level factors should prompt businesses to identify mechanisms that can combat corrupting influences. This evidence should also inform entrepreneurs and managers when contemplating business location decisions. That firms in less competitive industries and divided party states can weather the costs of corruption is notable for managers and policymakers as they balance expropriation risk amid competitive and political forces. Shareholders and managers of firms operating in corrupt districts should note that transparency prompted by mandatory audits may not be optimal in all cases, and that voluntary disclosure policies can be used strategically to benefit the firm.

Hypotheses Development

The Corruption–Value Relation

We first examine whether political corruption affects firm value within the U.S., on average. A long line of literature argues that corruption is inefficient and operates as a deadweight loss or tax levied on economic activity (i.e., the costs of political corruption outweigh any potential benefits). This research also suggests that a politically corrupt culture negatively affects firm value even when firms do not participate in corrupt activities. Specifically, when an inefficient firm remains in a market by engaging in corrupt practices, it creates competition for scarce resources that, in a corruption-free environment, would have flowed to more efficient firms at a lower cost. This misallocation of resources depresses market values for all firms in a corrupt area by effectively increasing the cost of operation. Buchanan and Tullock (1962) and Rose-Ackerman (1975, 1999) provide notable findings in this literature, and research by Shleifer and Vishny (1993, 1997, 1998) also indicates that firms in corrupt environments are less efficient.

Though Dass et al. (2016) find that market value is markedly lower for firms operating in politically corrupt areas of the U.S. (measured over a long time-series based on the DOJ’s convictions data), Borisov et al. (2016) find that U.S. firms involved in corrupt lobbying suffer a decline in firm value following a shock that limits illegal lobbying. This evidence indicates that some U.S. firms may indeed benefit from corruption, and therefore we test whether the broader finding in Dass et al. (2016) holds in our sample before investigating our primary hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1 (H1)

Firm value is negatively associated with political corruption.

Factors Influencing the Corruption–Value Relation

Our main hypotheses investigate factors that may mitigate or even exacerbate the relation between political corruption and firm value, i.e., those firm-specific and regional characteristics that might lessen or bolster the effects of corruption. Motivated by prior research, we investigate two important factors that may affect the corruption–value relation: (1) economic rents that are potentially subject to expropriation risks and (2) monitoring mechanisms at the firm and state government levels.

Prior cross-country studies suggest that public officials have greater incentives to engage in malfeasant behavior when firms enjoy higher rents. In other words, the perceived value of corrupt practices increases with the firm’s ability to reciprocate. Consistent with this notion, Ades and Di Tella (1999) find that corruption is more pervasive in countries where domestic firms enjoy higher rents as proxied by the level of high-rent natural resources and the extent to which domestic firms are sheltered from foreign competition. Likewise, Clarke and Xu (2004) and Emerson (2006) find higher corruption levels when rents are induced by low competition.

While the connection between corruption and firm rents is well established in the literature, the resulting effect on firm value is more ambiguous. On one hand, if firms with higher rents tend to face more corruption, then it is reasonable to expect the negative effect of corruption on firm value to strengthen as firm rents increase. On the other hand, higher firm rents could serve as a mitigating factor by insulating the firm from advances by corrupt politicians. Consistent with this latter argument, prior research suggests that high-rent firms are better able to fend off the negative effects of corruption due to stronger market and political power, and greater investment in effective monitoring mechanisms (Beck et al. 2005). High-rent firms are also less dependent on regulatory and government interaction for future growth, thereby increasing their ability to push back on political malfeasance (Desai et al. 2003; Svensson 2003).

To formally test the moderating role of firm rents, we follow the aforementioned research and use industry competition to capture the extent to which firms enjoy higher economic rents. We expect the expropriation incentives of corrupt officials to be stronger for firms operating in less competitive industries. However, we present our second hypothesis in null form since the effect of firm rents on the corruption-value relation is unclear.

Hypothesis 2 (H2)

Firm-level economic rents do not influence the negative association between political corruption and firm value.

Similarly, we expect monitoring mechanisms to affect the relation between corruption and firm value, though the direction of this influence is also unclear. Prior theoretical and empirical work by Stulz (2005) and Durnev and Fauver (2011) suggests that in corrupt areas, shareholders have less incentive to improve internal monitoring (i.e., corporate governance) for firms in corrupt areas. This incentive problem occurs because any decrease in managerial diversion of value away from shareholders will likely result in an increase in the diversion of value by corrupt officials. Stulz (2005) refers to this issue as the twin-agency problem and suggests that it plays a role in limiting financial globalization.

Monitoring by external parties reflects similar twin-agency problems. For instance, in the context of external audit monitoring, Wang et al. (2008) find that politically connected state-owned enterprises in China are more likely to opt for weak audit monitoring in an effort to facilitate collusion and information sharing with public officials. Using cross-country data of privatized firms, Guedhami et al. (2009) find that the demand for high-quality auditors decreases with the share of government ownership and the level of potential government expropriation. Likewise, Hope et al. (2008) document that firms operating in secretive cultural environments tend to hire low-quality auditors in an effort to preserve business secrecy and limit rent extraction from corrupt officials. Together, this body of evidence suggests that weak monitoring mechanisms serve as a tradeoff between managerial and political expropriation risks and, in some instances, are put in place to boost the potential benefits of political malfeasance or to minimize deadweight losses associated with corruption.

Despite these tradeoffs, a large body of academic and policy research advocates for strong internal and external monitoring as a means of restraining corruption. For instance, several cross-country studies suggest that internal monitoring is value enhancing for firms facing low-quality governments (Klapper and Love 2004; Wu 2005). This view is also trumpeted by several non-governmental organizations such as The World Bank’s International Finance Corporation (Khanna and Zyla 2012) and the United Nation’s Global Compact (United Nations 2009). Likewise, researchers have established that external monitors such as auditors can help mitigate the costs of a weak legal environment for clients (Choi and Wong 2007; Kwon et al. 2007).

Firm disclosure decisions also fit the model of external monitoring as prior literature finds that information transparency induces monitoring by outside parties such as investors, analysts, and the business press (Lang and Lundholm 1996; Miller 2006; Dyck et al. 2008). Disclosure transparency presents similar paradoxes as transparency can exacerbate corruption costs by revealing the presence of economic rents to corrupt officials (Kolstad and Wiig 2009). In line with this argument, Healy and Palepu (2001) highlight that firms often weigh the benefits of informing outside investors and other parties against the costs of revealing information that may attract explicit or implicit wealth transfers from the political sector. Watts and Zimmerman (1978) further argue that firms can reduce expropriation costs by electing disclosure policies that draw less attention to firm performance and resources.Footnote 6 Indeed, Durnev and Fauver (2011) and Dass et al. (2016) find that disclosure transparency is much lower among firms operating in corrupt areas, though it is unclear how this lack of transparency affects firm value. This unanswered question is important as firm opacity might promote managerial diversion, rather than shielding the firm from public corruption.

Based on the aforementioned arguments, we use three proxies to test whether firm-level monitoring moderates the corruption–value relation: (1) the number of anti-takeover and managerial entrenchment provisions in the firm’s corporate charter as a proxy of strong internal monitoring, (2) the use of a Big N audit firm as a proxy for strong external monitoring, and (3) whether the firm issues voluntary disclosures as a proxy for transparency-related monitoring. We test the following non-directional hypothesis given the divergent arguments on whether strong (weak) monitoring mitigates (exacerbates) the value effects of political corruption:

Hypothesis 3 (H3)

Internal and external monitoring at the firm level do not influence the negative association between political corruption and firm value.

We next investigate the role of interparty competition within state governments as a political monitoring mechanism on corrupt public officials. The political science literature argues that opposing party competition is a powerful deterrent to misconduct in public office (Nice 1983; Fackler and Lin 1995; Meier and Holbrook 1992). Specifically, when party control in governments is divided, public officials face more intense monitoring from the opposing party, which in turn restricts corruption. In the same vein, prior studies argue that corruption is more likely to flourish when a single party is dominant, because there is limited scrutiny from opposing party officials (Rose-Ackerman 1999). We therefore posit that divided party control at the state government level will mitigate the negative value effects of corruption as follows:

Hypothesis 4 (H4)

Divided party control within state governments reduces the negative association between political corruption and firm value.

Sample Construction and Empirical Measures

Sample Construction

Our sample consists of U.S.-domiciled firms that appear in the Compustat Fundamentals Annual database for at least 1 year over the 1996 to 2013 period.Footnote 7 The sample begins in 1996 to coincide with the first available year of our corporate governance data and ends in 2013 which is the last year of our U.S. District Court data on federal corruption convictions (described in detail below). Sample firms must be headquartered in the U.S. to be matched to a U.S. District Court district. Consistent with prior research (John and Kadyrzhanova 2008), we focus on the location of firms’ headquarters, rather than incorporation, since firms often have a large portion of their operations in the headquarter location.Footnote 8 We exclude firm observations with missing headquarter location information at either the state or county level.Footnote 9 We then match the Compustat sample to the corruption convictions data panel by district and year. We further restrict the sample to those firm-years with the necessary data to measure our primary variables of interest as well as our control variables. These procedures yield a final sample of 69,673 firm-years. Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for our final sample. We winsorize all continuous measures at the 1st and 99th percentiles to control for outlier observations.

Corruption Measure

Following prior studies (Glaeser and Saks 2006; Butler et al. 2009; Dass et al. 2016), we construct a data set from the DOJ’s Public Integrity Section (PIN) annual reports to Congress that chronicle the convictions of public officials on corruption charges in U.S. District Courts. These within-country data naturally rule out differences in country-level institutions commonly found in international corruption studies. Further, in using the federal district court system, we avoid the noise inherent in analyzing convictions across different states or judicial systems. The data are available by federal judicial district (94 in the U.S. and U.S. territories) and by year (panel), which allows for variation within the U.S., both across and within districts. While some studies use the convictions data to construct a state-level corruption measure, we focus on the number of convictions within each federal judicial district.Footnote 10 This approach yields substantially greater cross-sectional variation than the state-level approach, as the judicial districts in our study represent an 80% increase in sample size.

The PIN is a subsection of the criminal division of the DOJ. The subsection’s primary responsibility is to oversee the prosecution of elected and appointed local, state, and federal government officials accused of corruption. The PIN releases an annual report to Congress that details the number of corruption convictions in the U.S. District Court system (where the vast majority of such cases are tried). The conviction rates exceed 90% in the PIN cases, indicating the DOJ’s effectiveness in detecting and prosecuting corrupt activities (note that, because this is a criminal court, all pre-trial settlements occur as plea deals, which are counted as convictions in the PIN reports). About 75% of the convictions are of government officials, with the remainder consisting of private citizens convicted as part of a political corruption investigation. Thus, the PIN data allow us to capture the culture of political corruption within a given district that could directly or indirectly affect the value of firms operating within that same locality.

The annual PIN reports highlight a few of the major cases prosecuted each year. Typical examples include officials extorting or accepting bribes from firms in exchange for preferential treatment in legislative and regulatory processes. For instance, U.S. v. Johnson (Northern District of Ohio) resulted in the conviction of an Ohio State Senator on charges of extorting campaign contributions and loans (that went unpaid) from grocery stores in exchange for government contracts. U.S. v. Plowman (Southern District of Indiana) led to the conviction of an Indianapolis city councilman for accepting a bribe to support the development of strip clubs. A high-profile case, U.S. v. Siegelman and Scrushy (Middle District of Alabama), involved the conviction of a former governor for accepting $500,000 in campaign donations from a healthcare executive in exchange for a seat on a state hospital regulatory board.

The PIN data report the aggregate number of corruption convictions by year and federal judicial district. While the reports do not provide details on the cases underlying the convictions (only a few are summarized in the Congressional reports), the conviction numbers by year and district provide the most granular estimates of corruption across the U.S. There are 94 federal districts in the U.S. and its territories. Each state includes at least one district, and districts do not cross state lines. We exclude the four districts that preside over U.S. territories, resulting in a final count of 90 districts—89 districts across the 50 states and 1 district for the District of Columbia.Footnote 11 All 90 districts are represented in our sample. The last district realignment occurred in 1978, and thus the district boundaries remain constant throughout our sample period (1996–2013).

Districts vary in the size of their jurisdiction and workload. We control for this variation by standardizing the convictions in each district-year by the district’s population. We gather annual population estimates from the U.S. Census Bureau and match them to each district using the Federal Information Processing Standard (FIPS) geographic codes. The districts are divided along county lines and match perfectly to the FIPS codes. We are thus able to construct a panel of per capita corruption convictions by U.S. District Court district and year. We use this per capita corruption measure to proxy for the level of political corruption that each firm faces over time within the district of its headquarters.Footnote 12

Table 2 provides the median per capita convictions for each district ordered from most to least corrupt.Footnote 13 For ease of exposition, we denote political corruption in this table as convictions per 100,000 residents. The District of Columbia ranks as the most corrupt district in the U.S., which is not surprising given its higher proportion of public officials to residents.Footnote 14 The descriptive statistics in Table 2 clearly demonstrate the usefulness of district-level versus state-level analysis. Districts within Tennessee, for example, vary widely in terms of corruption. We note that the median annual corruption level in the District of Western Tennessee is the 5th highest in our sample, while the District of Middle Tennessee is ranked 64th. In terms of magnitude, the District of Western Tennessee has nearly four times the per capita convictions as the District of Middle Tennessee. Prior studies at the state level ignore such intrastate variation, whereas our district-level analysis exploits this variation to conduct more powerful tests.Footnote 15 For our empirical tests, we use the population-normalized number of convictions for each district-year as our corruption measure (Corruption). We standardize the Corruption variable over our sample period with zero mean and unit standard deviation. Thus, positive (negative) values of Corruption indicate district-years in which corruption is higher (lower) than the sample mean.Footnote 16 “Appendix” defines our corruption measure and all other measures outlined below.

Firm Value Measure

We rely on Tobin’s Q to proxy for firm value in our tests of Hypothesis 1 through 4 (H1–4). Following Gompers et al. (2003), we define Tobin’s Q as the ratio of market value of assets to book value of assets, where market value is the book value of assets plus the market value of common stock less the book value of common stock and deferred taxes. We remove firm observations with missing data for the computation of Tobin’s Q and several correlated factors. These factors include incorporation in Delaware and inclusion in the S&P 500 Index (Gompers et al. 2003), which we capture using indicator variables, as well as ratios of R&D expenditures to sales, advertising and sales expenses to sales, and long-term debt to assets (John and Kadyrzhanova 2008). We follow prior studies and set missing values of R&D expenses to zero.Footnote 17

Moderating Measures

We use industry competition as a proxy for economic rents to investigate how rents moderate the relation between corruption and firm value (H2). We capture industry competition using a new robust measure of the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI), based on the similarity of product descriptions as developed in Hoberg and Phillips (2016) and used in several studies.Footnote 18 For ease of interpretation, we construct an indicator variable for competitive product markets (Competitive Product Market) by setting the indicator to one for each firm-year that falls outside of the lowest decile of product market competition and zero otherwise.

Our firm-level monitoring hypothesis (H3) requires data on internal and external monitoring mechanisms. Our measure of internal monitoring focuses on corporate governance, captured using the number of anti-takeover and entrenching provisions in the firm’s corporate charter, specifically the Entrenchment Index of Bebchuk et al. (2009).Footnote 19 We create an indicator variable, Strong Governance, that equals one for firm-years with an Entrenchment Index value that is less than or equal to two, and zero otherwise. We use auditor quality as a proxy for external monitoring. Prior research suggests that Big N auditors provide better monitoring and assurance services (see Francis 2004 for a review of this literature). Consistent with this view, we capture auditor quality using a Big N indicator variable (Big N Auditor): Big 6 at the beginning of our sample and Big 4 at the end, with changes in the interim due to audit firm mergers and the failure of Arthur Andersen. We gather auditor data by year from the Audit Analytics database.

Following prior disclosure research (Bourveau et al. 2018; Cooper et al. 2018; He and Plumlee 2019), we focus on two forms of voluntary disclosure to capture transparency-related monitoring: (1) management earnings forecasts (similar to Dass et al. 2016) and (2) voluntary disclosure items on Form 8-K releases filed with the SEC (see Bourveau et al. 2018; He and Plumlee 2019 for similar constructs). We classify three 8-K disclosure items as voluntary: “Results of Operations and Financial Condition,” “Regulation Fair Disclosure,” and “Other Important Events.”Footnote 20 We use two indicator variables to denote whether a firm issues these forms of voluntary disclosure in a given year: (1) Issued Mgmt. Earnings Forecast, and (2) Issued Voluntary 8-K Release. Voluntary 8-K disclosures are perhaps a broader measure of firm transparency, since many firms do not provide earnings guidance. Prior evidence suggests, however, that 8-K filings are less responsive to changes in firm disclosure policies relative to earnings guidance (Bao et al. 2018).

To test how interparty monitoring within state governments affects the corruption–value relation (H4), we classify the government within each state as unified or “split” based on party control of the state legislature in a given year. A split or divided majority refers to cases when the upper house of the state legislature is controlled by one party and the lower house by another, and thus reflects periods when both parties are powerful within the state government. We gather annual data on state party majorities from the National Conference of State Legislatures. We then construct an indicator variable (Unified State Government) for states under a single party’s control. The omitted category is thus state-years with split legislatures.

Empirical Results

H1: The Effect of Political Corruption on Firm Value

We use OLS regressions of firm value (Tobin’s Q) to test H1 and all subsequent hypotheses. This empirical approach follows from Dass et al. (2016) and other studies focused on firm value. We estimate our regressions with robust standard errors clustered by firm and with industry and year fixed effects to control for unobserved firm and industry factors.Footnote 21 To assuage concerns about outliers influencing our results, we also report models estimated using the least median of squares (MLS) method, as introduced in Massart et al. (1986) and Rousseeuw (1984).

Table 3 presents regression results for H1. The results indicate a negative and statistically significant association between political corruption and firm value within the U.S. These results are consistent with the evidence in Dass et al. (2016) and suggest that political corruption is inefficient on average for U.S. firms. To gauge the economic significance of our results, we evaluate the marginal effects of Model 1. With all control variables set at the median, a one standard deviation increase in Corruption is associated with a decrease in Tobin’s Q that is equivalent to destroying $7.6 million in shareholder value for the median firm (a 4% decrease in Tobin’s Q). Thus, our results suggest that political corruption at the district level has an economically significant effect on the value of U.S. firms.

H2: Firm-level Economic Rents and the Corruption–Value Relation

We next investigate whether the inverse corruption–value relation confirmed in H1 is attenuated by economic rents earned by firms (proxied by industry competition). Table 4 presents the results of our analyses. In Model 1, we estimate the separate effects of the Corruption measure and the Competitive Product Market indicator to confirm our baseline result from H1 while controlling for industry competition. We then introduce the interaction of these two variables of interest in Model 2. The results from Model 1 continue to indicate that political corruption is value destroying, even after controlling for the effects of industry competition. Interestingly, the results from Model 2 suggest that the negative relation between corruption and value is driven by firms operating in competitive product markets. This evidence is consistent with the notion that firms with low economic rents tend to invest less in oversight mechanisms and government influence, which makes these firms particularly susceptible to the deleterious effects of corruption on value (Beck et al. 2005; Svensson 2003).

Economically, the results in Table 4 indicate that firms facing high product market competition (i.e., those outside of the lowest decile of market competition) suffer a 3.6% decrease in Tobin’s Q when corruption shifts upward by one standard deviation. This effect translates to a reduction in market capitalization of $7.1 million for the median firm in the final year of our sample. Conversely, low-competition firms do not experience a significant change in Tobin’s Q when corruption increases (see insignificant main effect of Corruption in Model 2). This result suggests that, while low-competition firms with higher rents are likely more appealing as targets for corrupt officials, rent-seeking is damaging only to firms in competitive industries (presumably because they have less financial slack to divert to corrupt activities).

H3: Firm-Level Monitoring Mechanisms and the Corruption–Value Relation

We now turn our attention to assessing whether firm-level monitoring mechanisms influence the corruption–value relation (H3). Models 1 to 3 of Table 5 examine whether anti-takeover and entrenchment provisions are beneficial (Klapper and Love 2004; Wu 2005) or detrimental to firm value (Stulz 2005; Durnev and Fauver 2011) when firms operate in corrupt districts. We again re-estimate the baseline effect of Corruption in Model 1 (without an interaction) while controlling for the value effects of corporate governance (Strong Governance). Note that the Big N Auditor variable is included in all the models in Table 5 since this variable is a standard covariate of firm value (Tobin’s Q) based on prior research. We also suppress the estimated coefficients on our control variables in Table 5 and the remaining tables for brevity.

The results in Model 1 indicate that the firm value effect of strong corporate governance does not subsume or reduce the negative effect of corruption on firm value. In other words, the estimated coefficient on Corruption is of the same economic magnitude and statistical significance as the reported result in Table 3 (see Model 1). We introduce the interaction between Corruption and Strong Governance in Model 2 (OLS) and Model 3 (MLS) and find that the coefficients are statistically insignificant. Thus, contrary to conventional thought, neither entrenched managers nor empowered shareholders are particularly apt at mitigating the damaging effects of political corruption on U.S. firm value.

We next examine auditor quality as an alternative monitoring mechanism. Model 4 presents baseline regression estimates, while Models 5 and 6 present regression results after interacting Corruption with the Big N Auditor indicator variable. We find that strong outside monitoring from high-quality auditors drives the negative value effects of political corruption. This result suggests that instead of serving as a stand-in for strong institutional quality in corrupt locales (Choi and Wong 2007; Kwon et al. 2007), high-quality auditors may restrict managerial collusion or information sharing with government officials to the detriment of the firm (Hope et al. 2008). Alternatively, this result could be interpreted to suggest that strong audit monitoring promotes greater information transparency that attracts expropriation from corrupt public officials. The economic significance of this audit monitoring effect is substantial. For firms not audited by a Big N Auditor, a one standard deviation shift in corruption (with other variables set at the median) does not significantly affect predicted firm value.Footnote 22 The corresponding decrease for firms audited by Big N Auditors is nearly 5.7%. For the median firm in our sample, this decrease in Tobin’s Q is associated with a striking reduction in firm value of about $11 million. This result is confirmed in Model 6, which uses a MLS regression.

Lastly, in untabulated tests, we re-estimate the models in Table 5 after including both monitoring variables and their interactions with Corruption. Our results are quantitatively similar and indicate that our governance and auditor quality variables capture different aspects of monitoring. Consistent with our results in Table 5, the interaction between Corruption and Big N Auditor is positive and significant, but the interaction with Strong Governance is insignificant.

In Table 6, we conduct tests of the relation between district-level corruption and the issuance of voluntary firm disclosures (our proxy for transparency-related monitoring). We use linear probability models for these tests so that we can continue to include industry and year fixed effects in our regressions. The regression results indicate that corruption reduces firms’ propensity to issue both earnings guidance and Voluntary 8-K Releases. These results complement those in Dass et al. (2016), who also suggest that firms in corrupt areas are less transparent (using other measures), presumably as a shielding mechanism. However, as discussed earlier, it is an open question whether lower transparency mitigates or exacerbates the value-destroying effects of corruption.

To address that question, we re-estimate our Tobin’s Q regressions after including the main and interaction effects of Corruption with our voluntary disclosure indicator variables. We report these results in Table 7. In Models 2 and 4, we observe positive and significant coefficients on the interaction variables, suggesting that voluntary disclosure (when it does occur) reduces the negative effect of corruption on firm value. Put differently, given the low levels of disclosure in corrupt areas, the marginal disclosure is more valuable. Contrasted with the auditor results, this might indicate that, while voluntary disclosures can be used strategically to abate corruption costs, transparency prompted by mandatory audits can be value destroying.

H4: Interparty Monitoring and the Corruption–Value Relation

In Table 8, we estimate the effect of state government monitoring on the corruption–value relation. Models 1 and 3 present stand-alone regression results, while Models 2 and 4 present results after interacting our Corruption measure with the Unified State Government indicator variable. We find that corruption destroys value primarily when state governments are dominated by a single party. From Models 2 and 4, the estimated coefficients on the Corruption × Unified State Government interaction terms are both significantly negative at the 10% level or better. Moreover, we observe that corruption does not affect firm value when state party control is divided (see insignificant coefficients on Corruption variable in Models 2 and 4). Thus, it appears that some level of government monitoring occurs within split party governments, which in turn restricts the value-destroying effects of corruption.

Conclusion

Using an inclusive sample of U.S. firms over the 1996 to 2013 period, we first confirm the broad evidence in Dass et al. (2016) and document a significantly negative relation between political corruption and firm value. We then extend this finding and investigate the cross section of the corruption–value relation. We observe that this relation is moderated by several firm- and government-level factors that capture economic rents available for expropriation and monitoring mechanisms. Specifically, low-rent firms (with less slack) are particularly vulnerable when operating in corrupt areas. We also find that strong monitoring mechanisms at the firm level do not mitigate and may even exacerbate the negative effect of corruption on firm value. As well, though firms in corrupt areas are more opaque, we document that voluntary disclosure (when it does occur) is more valuable to firms operating in corrupt areas than those in non-corrupt areas. Additional analyses suggest that corruption is particularly value destroying when state governments are controlled by a single party, consistent with the notion that interparty monitoring deters corruption.

Our study extends burgeoning research on the effects of corruption on firm value in the U.S. context. Our results suggest that U.S. managers, policy makers, and shareholders should consider political corruption whenever contemplating decisions that could alter firms’ choice of monitoring mechanisms and competition within product markets and across political parties. Moreover, our results have important implications for businesses and entrepreneurs when making decisions regarding the location of their headquarters or operations. Lastly, our evidence suggests that corruption and improbity are important factors that should be accounted for in research that examines the determinants of firm value in the U.S.

Notes

The definition of corruption varies greatly in the academic literature (Warren and Laufer 2009). Our definition narrowly focuses on political corruption in terms of specific transactions as well as general relationships between public officials and private agents. We also note that political corruption is distinct from bureaucratic inefficiency and weak institutional quality, and captures broader costs and benefits than those associated with political lobbying and political connectedness, which are legal ways to gain political influence (Campos and Giovannoni 2007).

The DOJ’s convictions data do not provide granular information on the types of corrupt acts committed within each district. While the lack of detailed data is a limitation of our study, we note that the DOJ’s convictions data are the most direct measure of political corruption within and across American states. Highlights of cases from the DOJ’s annual reports to Congress indicate that typical offenses include firms making bribes, unofficial payments, or campaign contributions in exchange for direct political actions as well as extortion and criminal conflicts of interest by public officials. The convictions also capture corrupt and unethical practices that indirectly affect firms such as election crimes and other crimes of a strictly political nature.

Firm value is the inflation-adjusted stock market capitalization in 2013 dollars. The economic magnitude of our corruption-value effect is similar to that reported in Dass et al. (2016). Using state-level aggregates of the convictions data, Dass et al. find a 5% decline in firm value when moving from the fifth least corrupt state (Minnesota) to the first most corrupt state (Mississippi).

Our corporate governance measure is based on the Entrenchment Index developed by Bebchuk et al. (2009). The entrenchment index is a count of six anti-takeover and entrenching provisions that exist in a given firm’s corporate charter: staggered boards, limits on amending by-laws, limits on amending charters, supermajority requirements, poison pills, and golden parachutes. As argued in Bebchuk et al. (2009), these provisions promote managerial entrenchment by (1) limiting the extent to which shareholders can impose their will on management and (2) insulating managers from hostile takeovers (see Bates et al. 2008 for evidence consistent with staggered boards as a strong entrenchment device). Consistent with this argument, we use the term “strong corporate governance” to refer to a low number of anti-takeover and entrenching provisions within the firm’s corporate charter (i.e., the inverse of the Entrenchment Index).

Consistent with our earlier arguments, firms in more corrupt districts could also disclose less to hide collusion with public officials or to preserve business secrecy.

Our sample is free of survivorship bias since we do not restrict our sample to surviving firms.

Corruption occurs when a transfer of wealth is beneficial to public officials (and, in some cases, firms), and these opportunities generally arise in situations where a firm applies or competes for a tax credit, contract, permit, license, or other action (such as a takeover) that requires government approval. A firm is more likely to engage in such activity in the district in which it focuses its operations, generally that of its headquarters. Thus, we believe it is more appropriate to focus on the district location of firms’ headquarters as opposed to the state of incorporation. In untabulated analyses, we use data from García and Norli (2012) to control for the geographic dispersion in the operations of a subset of our sample firms over the 1994 to 2008 period. The García–Norli (2012) data are based on disclosure text extracted from 10-K filings and counts how many times each state name appears in discussing the firm’s operations. We merge the data with our sample and measure geographic concentration in the headquarter state as the ratio of headquarter-state name counts scaled by the counts of all U.S. states. We then restrict the sample to those firm-years in which the headquarter-state concentration ratio is at least 0.25. We replicate our tests using this reduced sample and find evidence consistent with our main results.

We use the header information from firms’ 10-K filings to capture the location of their headquarters. This provides more precise information compared to the location information in Compustat and, thus, allows us to capture changes (though rare) in firm headquarter locations and state of incorporation over our sample period.

Prior studies use the DOJ convictions data to demonstrate that state-level corruption affects state education and income levels (Glaeser and Saks 2006) and the sale and underwriting of municipal bonds (Butler et al. 2009). Relatedly, Dass et al. (2016) use the convictions data at both the state and district levels to show that corruption dampens U.S. firm value.

These district-level data preclude any analysis of the variation in corruption within a district. For example, we are unable to detect or exploit differences in the level of political corruption between neighborhoods in the same city. Future researchers with better access to granular location data should view this as a potential area for further research.

Across our sample, the correlation between current and lagged corruption varies between 0.70 and 0.85 (depending on the measure of corruption; see Footnote 16 for alternative constructions of the corruption measure), which suggests that within a district, corruption from year to year is similar, but not unchanging.

The annual number of convictions is missing for some district-years. For these years, we use the average of the number of convictions for the year before and after. Our results are not affected when these years are excluded.

Our inferences are unchanged when we remove the District of Columbia from our sample.

To draw any inferences from our regressions with these data, we assume the ratio of convictions to underlying corruption is relatively homogeneous or proportional across districts. If per capita convictions do not accurately reflect the corrupt nature of a district, or if certain districts are more thorough in rooting out corruption than others, then our proxy may be inappropriate. Using conviction statistics based on the U.S. District Court system alleviates much of the concern about heterogeneity in the vigilance of the prosecution. Prosecutorial vigilance is mandated at the federal level; thus, federal prosecutors are likely to prosecute cases with equal vigor regardless of the district. Indeed, Meier and Holbrook (1992) find that the number of corruption convictions at the state level is largely unaffected by the number of federal prosecutors and judges within each state. Occasionally, an unusually complicated or expensive corruption case will be moved from a state court to a U.S. District Court. While such moves could introduce a bias, these cases are quite rare.

A more pressing concern is whether corruption convictions represent a reasonable proxy for the underlying corruption within a district. This concern is alleviated to a great extent by Glaeser and Saks (2006), who observe a positive correlation between the conviction data (at the state level) and the perception of state-level corruption by state house reporters (Boylan and Long 2003). Campante and Do (2014) also document a positive correlation between the conviction data and an online search volume measure of corruption at the state level. These correlations suggest that the conviction data represent underlying corruption reasonably well.

Our results are robust to using the untransformed Corruption values and to measuring Corruption based on the raw number of corruption convictions in each district-year. We report results based on the standardized Corruption measure for brevity.

These covariates are based on prior studies that rely on Tobin’s Q to measure firm value. We omit a few of the variables used in Dass et al. (2016) for reasons of data availability. However, we observe similar results in smaller samples with non-missing data for the full battery of firm-level covariates from Dass et al. (2016). Also, the treatment of missing R&D data does not affect our inferences. Our results are unchanged when we include an indicator variable to identify those firm-years with missing R&D data.

Prior research uses Tobin’s Q to capture not only firm value, but also the firm’s growth opportunities. Our inclusion of the ratio of R&D expenditures to sales—a widely used measure of growth opportunities—in our regressions should rule out this alternative interpretation of Tobin’s Q. In untabulated tests, we interact corruption with multiple permutations of the R&D-to-sales ratio and do not find significant interaction effects. This result suggests that corruption does not differentially impact the value of high- versus low-growth firms. Lastly, our regressions include industry and year fixed effects, which should subsume any between-industry and across-time differences in growth opportunities.

Hoberg and Phillips (2016) dispense with the typical industry-wide definition of product market competition (where industry concentration serves as a proxy) and develop a new firm-year specific HHI by reviewing over 50,000 product descriptions filed by firms with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). This new classification gauges the competitive environment of a firm based on the similarity of its product descriptions to those of other firms (referred to as the Text-based Network Industry Classification (TNIC). The new measure allows for more cross-sectional variation than measures based on SIC or NAICS industry codes, and has the benefit of being firm-specific and more applicable to firms in unique industries. The TNIC HHI data are available at http://hobergphillips.usc.edu/industryclass.htm.

The index is a count of six anti-takeover and entrenching provisions, where higher values represent weaker corporate governance through increased managerial entrenchment and less minority shareholder protection. The index is recalculated every 2 or 3 years, and unreported firm-years are matched to the previous measure, following Bebchuk et al. (2009). We gather the Entrenchment Index data from the Institutional Shareholder Services (ISS) database.

The SEC expanded and renumbered the list of events that would trigger a Form 8-K filing, effective August 23, 2004. The voluntary items considered in our study remained intact and largely unchanged after the SEC expansion. Prior to the expansion, the item numbers for the voluntary disclosure items are 12 (Results of Operations and Financial Conditions), 9 (Regulation Fair Disclosure), and 5 (Other Important Events). These item numbers were subsequently revised to 2.01 (Results of Operations and Financial Conditions), 7.01 (Regulation Fair Disclosure), and 8.01 (Other Important Events).

Our results (not reported) are robust to Fama–MacBeth regressions with Newey–West errors.

We caution readers to consider that Big N auditors tend to audit large firms, and that differentiating the Big N effect from a size effect is difficult. Untabulated results suggest that the Corruption × Big N Auditor term remains negative and significant in these models after including a Corruption × Size interaction term, but a dedicated analysis by future researchers may be of value.

References

Ades, A., & Di Tella, R. (1999). Rents, competition, and corruption. The American Economic Review, 89(4), 982–993.

Bao, D., Kim, Y., Mian, G., & Su, L. (2018). Do managers disclose or withhold bad news? Evidence from short interest. The Accounting Review. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3212921.

Bates, T., Becher, D., & Lemmon, M. (2008). Board classification and managerial entrenchment: Evidence from the market for corporate control. Journal of Financial Economics, 87(3), 656–677.

Bebchuk, L., Cohen, A., & Ferrell, A. (2009). What matters in corporate governance? Review of Financial Studies, 22(2), 783–827.

Beck, T., Demirgüҫ-Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, V. (2005). Financial and legal constraints to growth: Does firm size matter? Journal of Finance, 60(1), 137–177.

Borisov, A., Goldman, E., & Gupta, N. (2016). The corporate value of (corrupt) lobbying. Review of Financial Studies, 29(4), 1039–1071.

Bourveau, T., Lou, Y., & Wang, R. (2018). Shareholder litigation and corporate disclosure: Evidence from derivative lawsuits. Journal of Accounting Research, 56(3), 797–842.

Boylan, R., & Long, C. (2003). Measuring public corruption in the American States: A survey of State House reporters. State Politics and Policy Quarterly, 3(4), 420–438.

Buchanan, J., & Tullock, G. (1962). The calculus of consent. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Butler, A., Fauver, L., & Mortal, S. (2009). Corruption, political connections, and municipal finance. Review of Financial Studies, 22(7), 2873–2905.

Campante, F., & Do, Q.-A. (2014). Isolated capital cities, accountability, and corruption: Evidence from US States. American Economic Review, 104(8), 2456–2481.

Campos, N., & Giovannoni, F. (2007). Lobbying, corruption and political influence. Public Choice, 131(1), 1–21.

Choi, J.-H., & Wong, T. J. (2007). Auditors’ governance functions and legal environments: An international investigation. Contemporary Accounting Research, 24(1), 13–46.

Clarke, G., & Xu, L. (2004). Privatization, competition, and corruption: How characteristics of bribe takers and payers affect bribes to utilities. Journal of Public Economics, 88(9–10), 2067–2097.

Cooper, M. J., He, J., & Plumlee M. P. (2018). Measuring disclosure using 8K filings. Working paper, University of Utah and University of Delaware.

Collins, J., Uhlenbruck, K., & Rodriguez, P. (2009). Why firms engage in corruption: A top management perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 87, 89–108.

Cumming, D., Hou, W., & Lee, E. (2016). Business ethics and finance in Greater China: Synthesis and future directions in sustainability, CSR, and fraud. Journal of Business Ethics, 138(4), 601–626.

Dass, N., Nanda, V., & Xiao, S. (2016). Public corruption in the United States: Implications for local firms. Review of Corporate Finance Studies, 5(1), 102–138.

Desai, M., Gompers, P., & Lerner, J. (2003). Institutions, capital constraints and entrepreneurial firm dynamics: Evidence from Europe. Working Paper No. 10165. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Durnev, A., & Fauver, L. (2011). Stealing from thieves: Expropriation risk, firm governance, and performance. Unpublished Working Paper. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee.

Dyck, A., Volchkova, N., & Zingales, L. (2008). The corporate governance role of the media: Evidence from Russia. Journal of Finance, 63(3), 1093–1135.

Emerson, P. (2006). Corruption, competition and democracy. Journal of Development Economics, 81(1), 193–212.

Fackler, T., & Lin, T. (1995). Political corruption and presidential elections, 1929–1992. The Journal of Politics, 57(4), 971–993.

Francis, J. (2004). What do we know about audit quality? The British Accounting Review, 36(4), 345–368.

García, D., & Norli, Ø. (2012). Geographic dispersion and stock returns. Journal of Financial Economics, 106(3), 547–565.

Gardberg, N., Sampath, V., & Rahman, N. (2012). Corruption and corporate reputation: The paradox of buffering and suffering. In Academy of Management proceedings.

Glaeser, E., & Saks, R. (2006). Corruption in America. Journal of Public Economics, 90(6–7), 1053–1072.

Gompers, P., Ishii, J., & Metrick, A. (2003). Corporate governance and equity prices. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 107–156.

Guedhami, O., Pittman, J., & Saffar, W. (2009). Auditor choice in privatized firms: Empirical evidence on the role of state and foreign owners. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 48(2–3), 151–171.

He, J., & Plumlee, M. (2019). Measuring disclosures using 8-K filings. Unpublished Working Paper. Newark, DE: University of Delaware.

Healy, P., & Palepu, K. (2001). Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 31(1), 405–440.

Hoberg, G., & Phillips, G. (2016). Text-based network industries and endogenous product differentiation. Journal of Political Economy, 124(5), 1423–1465.

Hope, O.-K., Kang, T., Thomas, W., & Yoo, Y. K. (2008). Culture and auditor choice: A test of the secrecy hypothesis. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 27(5), 357–373.

Johan, S., & Najar, D. (2010). The role of corruption, culture, and law in investment fund manager fees. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(Supplement 2), 147–172.

John, K., & Kadyrzhanova, D. (2008). Relative governance. Unpublished Working Paper. Atlanta, GA: Georgia State University.

Khanna, V., & Zyla, R. (2012). Survey says…corporate governance matters to investors in emerging market companies. Washington, DC: International Finance Corporation.

Klapper, L., & Love, I. (2004). Corporate governance, investor protection, and performance in emerging markets. Journal of Corporate Finance, 10(5), 703–728.

Kolstad, I., & Wiig, R. (2009). Is transparency the key to reducing corruption in resource-rich countries? World Development, 37(3), 521–532.

Kwon, S., Lim, C., & Tan, P. (2007). Legal systems and earnings quality: The role of auditor industry specialization. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, 26(2), 25–55.

Lang, M. H., & Lundholm, R. J. (1996). Corporate disclosure policy and analyst behavior. The Accounting Review, 71(4), 467–492.

Leff, N. (1964). Economic development through bureaucratic corruption. American Behavioral Scientist, 8(3), 8–14.

Lindgreen, A. (2004). Corruption and unethical behavior: Report on a set of Danish guidelines. Journal of Business Ethics, 51(1), 31–39.

Massart, D. L., Kaufman, L., Rousseeuw, P. J., & Leroy, A. (1986). Least median of squares: A robust method for outlier and model error detection in regression and calibration. Analytica Chimica Acta, 187, 171–179.

Meier, K., & Holbrook, T. (1992). “I seen my opportunities and I took ‘em:” Political corruption in the American states. The Journal of Politics, 54(1), 135–155.

Miller, G. (2006). The press as a watchdog for accounting fraud. Journal of Accounting Research, 44(5), 1001–1033.

Nice, D. (1983). Political corruption in the American states. American Politics Quarterly, 11(4), 507–517.

Rose-Ackerman, S. (1975). The economics of corruption. Journal of Public Economics, 4(2), 187–203.

Rose-Ackerman, S. (1999). Corruption and government, causes, consequences and reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rousseeuw, P. J. (1984). Least median of squares regression. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 79(388), 871–880.

Sampath, V., Gardberg, N., & Rahman, N. (2016). Corporate reputation’s invisible hand: Bribery, rational choice, and market penalties. Journal of Business Ethics, 151, 1–18.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1993). Corruption. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(3), 599–617.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1997). A survey of corporate governance. Journal of Finance, 52(2), 737–783.

Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. (1998). The grabbing hand, government pathologies and their cures. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Stulz, R. (2005). The limits of financial globalization. Journal of Finance, 60(4), 1595–1638.

Svensson, J. (2003). Who must pay bribes and how much? Evidence from a cross section of firms. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 207–230.

United Nations. (2009). Corporate governance: The foundation for corporate citizenship and sustainable businesses. New York: United Nations.

Wang, Q., Wong, T. J., & Xia, L. (2008). State ownership, the institutional environment, and auditor choice: Evidence from China. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 46(1), 112–134.

Warren, D., & Laufer, W. (2009). Are corruption indices a self-fulfilling prophecy? A social-labeling perspective of corruption. Journal of Business Ethics, 88(Supplement 4), 841–849.

Watts, R., & Zimmerman, J. (1978). Towards a positive theory of the determination of accounting standards. The Accounting Review, 54(1), 112–134.

Wu, X. (2005). Corporate governance and corruption: A cross-country analysis. Governance, 18(2), 151–170.

Zeume, S. (2017). Bribes and firm value. Review of Financial Studies, 30(5), 1457–1498.

Acknowledgements

We thank Greg Shailer (Editor), three anonymous reviewers, Helen Brown-Liburd, David Denis, Diane Denis, Jing He, Andy Koch, Ahmet Kurt, Tianshu Qu (Discussant), Tom Shohfi, Scott Smart, Bryan Stikeleather, Shawn Thomas, Jack White, and seminar participants at Georgia State University, North Carolina State University, University of Florida, University of Pittsburgh, and the American Accounting Association Annual Meeting for insightful comments and suggestions. We also thank Diego García and Øyvind Norli for sharing data on firm operations and Gerald Hoberg and Gordon Phillips for sharing data on industry competition.

Funding

All authors did not receive funding from any sources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brown, N.C., Smith, J.D., White, R.M. et al. Political Corruption and Firm Value in the U.S.: Do Rents and Monitoring Matter?. J Bus Ethics 168, 335–351 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04181-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04181-0