Abstract

This study explored the relationship between religiosity and contextual work performance and offered empirical evidence for the mediating role of faith at work, meaning making and work engagement. Participants included 246 employees of Orthodox Christian faith, from various occupational domains. A path analysis testing both direct and indirect effects of religiosity, faith at work, meaning making and work engagement on organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) was conducted, and the proposed model demonstrated a good fit. The study advances the idea that individual religious beliefs that are upheld and manifested in work settings could generate meaning and sense to work, which further could lead to positive work-related attitudes (i.e., work engagement) and finally to higher reported levels of an aspect of contextual performance (i.e., OCB).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Religiosity in the workplace is a relatively recent topic in academic research (Benefiel, Fry, & Geigle, 2014; Hicks, 2003; Lynn, Naughton, & VanderVeen, 2011; Miller, 2007), that became increasingly prolific in the past few decades, alongside the one of spirituality at work (e.g., Ahmad & Omar, 2015; Ashmos & Duchon, 2000; Ayoun, Rowe, & Yassine, 2015; Duchon & Plowman, 2005; Hayden & Barbuto, 2011; Houghton, Neck, & Krishnakumar, 2016; Milliman, Czaplewski, & Ferguson, 2003; Mitroff & Denton, 1999; Pawar, 2016). Although the literature has outlined theoretical reasons for a positive influence of spirituality and religiosity on certain workplace behaviors (Houghton et al., 2016; Krishnakumar & Neck, 2002), mainly due to their perceived potential to render meaningful work experiences (Gotsis & Kortezi, 2008), empirical evidence to support these assertions is still sparse (Benefiel et al., 2014). There are some studies showing, in a rather empirical vein, a positive relation between religiosity and organizational citizenship behavior (Ahmad, Rahim, Chulan, Ab Wahab, & Noor, 2019; Kutcher, Bragger, Rodriguez-Srednicki, & Masco, 2010; Olowookere, 2014), however few comprehensive models regarding the mechanisms behind the impact of religiosity on job performance (or its components) have been explored in the literature (e.g., Haq, De Clercq, Azeem, & Suhail, 2018, who presented the moderating effect of perceived organizational adversity with respect to voluntarism in the relation between religiosity and change-oriented citizenship behavior). The present study offers evidence to support the hypothesis that religiosity is related to positive outcomes at work, when embraced and manifested in work contexts: religious employees are better employees due to their religion, when they uphold their beliefs at work and convey meaning to their job in the light of those beliefs.

Religion, Spirituality, and Faith at Work

The concepts of “religion” and “spirituality” are still marked by definitional wrangling (see also Fry, 2003; Hill et al., 2000; Houghton et al., 2016; Karakas, 2010; Marques, Dhiman, & King, 2005; Zinnbauer, Pargament, & Scott, 1999). Until the second half of the twentieth century (Nelson, 2009; Zinnbauer & Pargament, 2005), spirituality and religiosity were mostly seen as connected and overlapping – the term “religiosity” being preferred (see also Benefiel et al., 2014; Hill et al., 2000; Lynn, Naughton, & VanderVeen, 2009; Miller & Ewest, 2013; Zinnbauer & Pargament, 2005). The spiritual component of religiosity was considered to be “the essence of the religious life, a transcendent quality that cuts across and infuses all of core dimensions of religiosity” (Moberg, 2002, p. 48). Religion is “an organized system of beliefs, practices, rituals and symbols designed (a) to facilitate closeness to the sacred or transcendent (God, higher power, or ultimate truth/ reality), and (b) to foster an understanding of one’s relation and responsibility to others in living together in a community” (Koenig, McCullough, & Larson, 2001, p. 18), and was seen as inert when devoid of a spiritual core (Moberg, 2002).

The differentiation between the two concepts appeared only in the 1960s–70s, with the rise of secularism, when the term “spirituality” began to be favored, instead of “religiosity” (Hayden & Barbuto, 2011; Hill et al., 2000; Turner, Lukoff, Barnhouse, & Lu, 1995). “With the emergence of spirituality, a tension appears to have risen between the constructs of religiousness and spirituality. In its most extreme form, the two terms are defined in a rigidly dualistic framework. The most egregious examples are those that place a substantive, static, institutional, objective, belief-based, ‘bad’ religiousness in opposition to a functional, dynamic, personal, subjective, experience-based, ‘good’ spirituality” (Zinnbauer & Pargament, 2005, p. 24).

Thus, when viewed as qualitatively different, “spirituality” has usually a positive connotation – considered as a desirable preoccupation of modern people, a “contemporary” way of dealing with life’s profound meanings and existential questions (e.g., Giacalone & Jurkiewicz, 2003; Mitroff & Denton, 1999; Park, 2005; Zinnbauer & Pargament, 2005), whereas “religion” is more likely to have a negative connotation – seen as the “old fashion” style of relating to life, embedded in traditions and religious institutions that, to some extent, limit a person’s freedom (Hill et al., 2000; Miller & Ewest, 2013). Spirituality, today, “is often used to denote the experiential and personal side of our relationship to the transcendent or sacred (Emmons & Crumpler, 1999; Hill et al., 2000). Those who use the term in this way typically contrast it with religion, which they define narrowly as the organizational structures, practices, and beliefs of a religious group (Zinnbauer et al., 1999)” (Nelson, 2009, p. 8). Spirituality is seen as “the personal quest for understanding answers to ultimate questions about life, about meaning, and about relationship to the sacred or transcendent, which may (or may not) lead to or arise from the development of religious rituals and the formation of community” (Koenig et al., 2001, p. 18; for an extensive comparison between traditional and modern psychological approaches to religiousness and spirituality, see Zinnbauer et al., 1999).

In organizational settings, most of the research on this topic started only in the 1990s, therefore focusing rather on spirituality (e.g., Ashmos & Duchon, 2000; Ayoun et al., 2015; Brooke & Parker, 2009; Daniel, 2010; Marques et al., 2005), sometimes overlapped with religiosity (or faith – as synonymous term) (e.g., King & Crowther, 2004; Neal, 2013; Osman-Gani, Hashim, & Ismail, 2013) – depending on the scholars` preference (see also Lynn et al., 2009). These studies highlight several components of spirituality such as inner life, purpose, meaning and community at work (Ashmos & Duchon, 2000; Chawla & Guda, 2013; Duchon & Plowman, 2005; Gupta, Kumar, & Singh, 2014; Hamilton & Jackson, 1998; Hayden & Barbuto, 2011; Karakas, 2010; Milliman et al., 2003). Some researchers preferred to take an even broader perspective to the term spirituality and view it as part of organizational culture, determined or encouraged by managerial spiritual beliefs, but completely devoid of anything akin to religiosity (Giacalone & Jurkiewicz, 2003; Houghton et al., 2016).

Thus, workplace spirituality has “sidestepped” religiosity “focusing on the function of belief rather than its substance” (Lynn et al., 2011, p. 227). Yet, this approach cannot shed light on several issues such as, for example, “individual or institutional faith-work integration” (Lynn et al., 2011, p. 227).

These definitional positions are important for our study, as we take upon the classic (yet not, currently, mainstream) approach, by including religious faith in our focus. In this paper, our focus is on employee perception regarding the impact of the “Transcendent” on their own work life, in the context of a personal religious affiliation (i.e., Christian denomination religions). We therefore prefer to employ the terms religion, religiosity, faith at work instead of spirituality. We view the term “religion” in its historical, classical approach, as a multidimensional construct (that includes the spirituality dimension) defined as a system of “beliefs, practices, and rituals having to do with the ‘Transcendent’ or the ‘Divine’” (Koenig, Zaben, Khalifa, & Shohaib, 2015, p. 530). We consider that religiosity refers to the “beliefs, knowledge, attitudes, and the perceived importance of religion in the individual’s life” (Neff, 2006, p. 450).

As for the manifestation of religiosity in the workplace (i.e., faith at work), there are three main directions in the literature that approach this topic (Lynn et al., 2011): the Protestant work ethic (Benefiel et al., 2014; Furnham, 1990; Jones, 1997), workplace spirituality (Giacalone & Jurkiewicz, 2003; Marques, Satinder, & King, 2009) and workplace faith (Benefiel et al., 2014; Lynn et al., 2009; Miller, 2007). While the first two approaches focus on the impact of religious belief systems on global socio-economic development (the Protestant work ethic) respectively on the consequences of spirituality, viewed as a quest, in the workplace (this being, in fact, not strictly related to “faith at work” but to the previously discussed and larger field of workplace spirituality), the third line of research, more recently developed, incorporates cultural and personal religious influences on work (Hill, 2007; Lynn et al., 2011); this is the definitional line we adopt in our study.

Thus, integrating faith with work has been a topic of increasing interest for a number of scholars, yet theoretical advancement and empirical research has been limited (Benefiel et al., 2014; Epstein, 2002; Miller, 2007; Nash & McLennan, 2001). So far, empirical progress was made in documenting some topics such as the negative correlations between religious practice (measured on self-reported scales) and work-related stress and burnout, the tendency of religious beliefs and practices to be related positively to job satisfaction and organizational commitment or the positive relation between religious motivation and job satisfaction, organizational commitment and OCB (Kutcher et al., 2010). Another line of investigation aimed at uncovering the positive impact of religiosity on leadership practices or management processes (Benefiel et al., 2014).

One reason for this general paucity of empirical evidences on the topic is the fact that this field of research emerged “through theoretical advocacy and organizational case study rather than by data sets compiled from individual respondents” (Benefiel et al., 2014, p. 178). Another reason is generated by the lack of reliable measures targeting religiosity in the workplace (Miller & Ewest, 2013); the first questionnaire specifically targeting workplace religion appeared only in 2009 (Lynn et al., 2009). Besides this, only few studies, from the otherwise larger literature on the topic, reported adequate tests for the reliability and validity of their measures, and can be considered with confidence (for details, see Benefiel et al., 2014).

Another reason for the lack of adequate empirical research on the topic is the uncertain entanglement of faith and work (Benefiel et al., 2014; Miller & Ewest, 2013); while the relationship between faith and life in general is well researched, “faith-work integration takes on varied forms, from religion and work being conceptually disconnected, to religion serving a therapeutic or ethical role in work, to religion providing a comprehensive lens through which all work and life are seen” (Lynn et al., 2009, p. 227). As a result, there are also, as mentioned earlier, terminological and definitional variations in the literature, aimed to designate the same field of study (i.e., “faith at work”, “workplace religion”, even “workplace spirituality” for some authors), yet, “whatever name one gives the field, there is general agreement that it is driven by people desiring to live integrated lives, persons who are no longer satisfied to park their faith tradition or identity at the door when they go into work” (Miller & Ewest, 2013, p. 30).

Thus, in this matter of religion-and-work integration we argue, consonant with Pargament (2002), that religiousness in itself is necessary but not sufficient (as it doesn’t manifest intrinsically in the workplace), and that such individual-level integration of faith and work is critical in order to be able to assert that faith has an impact on work outcomes. To identify the impact that religiousness has on an individual’s work, beliefs have to be integrated with work, embraced, upheld and manifested in work settings (Miller & Ewest, 2013) and the religious employee has to be not just a “Christian on Sunday and atheist on Monday” (Glavaš, 2017, p. 29). In other words, employees would have to make sense of, and confer meaning to their work via faith. Therefore, we consider that faith at work refers to the actual manifestation of religiosity in work settings.

In order to establish this important connection, that has been to some extent shunned in the organizational literature (see also Benefiel et al., 2014), we advance our first hypothesis as follows:

-

H1: .

Religiosity (in general) is positively related with faith at work

Meaning, Engagement and Performance at Work

The literature on the meaning of work has a long tradition (for a review see Rosso, Dekas, & Wrzesniewski, 2010) and focused on uncovering its influence on outcomes such as work motivation (Roberson, 1990), work behavior (Berg, Wrzesniewski, & Dutton, 2010; Bunderson & Thompson, 2009), engagement (May, Gilson, & Harter, 2004), job satisfaction (Wrzesniewski, McCauley, Rozin, & Schwartz, 1997), career development (Dik & Duffy, 2009) or individual performance (Wrzesniewski, 2003). “Meaning” is the output of having made sense of something, allowing the employee to understand the role his/her work plays, in the context of his/her life (e.g., work is a paycheck, a higher calling, something to do, an oppression) (Pratt & Ashforth, 2003). A number of components, “primary facets” (Steger, Dik, & Duffy, 2012) define this concept: (a) psychological meaningfulness of the work (as defined by Hackman & Oldham, 1976 in their job characteristics model, i.e., the degree to which people judge their work to matter and to be valuable); (b) the construction of meaning through work (i.e., the degree to which work contributes to the construction of meaning of life as a whole; Michaelson, 2005; Steger & Dik, 2010), and (c) greater good motivations (i.e., the desire to make through one’s work a positive impact on other people’s lives and on the community; Grant, 2007; Steger et al., 2012).

Despite the vast array of angles from which the topic of meaning of work has been studied, there are two main larger topics that could delineate all the research made on this subject: the sources of the meaning of work and the mechanisms through which employees create meaning of work (Rosso et al., 2010).

The construction of meaning regarding one’s work has various sources: the self (personal values, motivations, beliefs), others (coworkers, leaders, groups and communities, family), the work context (design of job tasks, organizational mission, financial circumstances, non-work domains, national culture) and spiritual life (Rosso et al., 2010; Steger et al., 2012). Thus spirituality (not so much religiosity – for the before mentioned reasons) was studied as a source of meaningfulness and research shows that “spiritual employees perceive their work differently than non-spiritual employees, seeing their work behaviors in spiritual terms of caring, service, and transcendence (Curlin, Dugdale, Lantos, & Chin, 2007; Grant, O'Neil, & Stephens, 2004; Scott, 2002; Wuthnow, 2004)” (Rosso et al., 2010, p. 107).

However, given the fact that the literature indicates that “single sources of meaning or meaningfulness have typically been examined in isolation from other sources” and that “a variety of different, and often implicit, explanations for the processes – or mechanisms – through which work takes on meaning or is perceived as meaningful” exists (Rosso et al., 2010, p. 93), one of our purposes is to address these shortcomings and to explicitly propose and test such a mechanism that could explain how work can take on meaning and positively influence work outcomes, having personal faith as source.

Examining the literature (e.g., Batson & Stocks, 2004; Park, 2005; Silberman, 2005), Martos, Thege, and Steger (2010) conclude that “religiosity has been considered an important part of how some people construct meaning” (p. 863). The influence of faith (and even the more documented field of spirituality at work) on meaning making at work remains considerably understudied (Rosso et al., 2010) because even though many individuals turn to their faith in making sense of their life and defining their purpose in life (Lips-Wiersma, 2002; Šverko & Vizek-Vidović, 1995), they “may be reluctant to discuss it at work” (Rosso et al., 2010, p. 106). Thus, spirituality as a source of meaning (and religiosity, even more) “needs more rigorous empirical work to supplement, test, and build upon the extant theoretical perspectives” (Rosso et al., 2010, p. 107).

As individuals consider religious beliefs and experiences as a source of meaning in their life in general (Dahinden & Zittoun, 2013; Fletcher, 2004; Schnell & Becker, 2006), we are interested in uncovering whether religious employees construct meaning for their work through their faith and if this meaning further impacts their work-related attitudes (i.e., the way they subsequently engage in their work) and their work-related behaviors (i.e., performance). We, therefore, advance our second hypothesis:

-

H2: .

Faith at work is positively related to meaning of work.

Among all work attitudes, work engagement has one of the most consistent relationship with job performance (Christian, Garza, & Slaughter, 2011; Halbesleben, 2010; Kim, Kolb, & Kim, 2013) and was therefore selected as a critical variable in this paper. Engagement was defined as “a positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterized by vigor, dedication and absorption” (Schaufeli, Salanova, González-Romá, & Bakker, 2002, p. 74). Vigor is associated with high energy levels and with activation while at work. Dedication is related to “enthusiasm, feeling proud because of the work done, being inspired by one’s job, and feeling that one’s work is full of meaning and purpose” (Salanova & Schaufeli, 2008, p. 118), while absorption refers to a state of full concentration in work. The second dimension of work engagement – dedication – explicitly includes meaning, suggesting that engagement may be one important variable in the “path” from religiousness to work performance. In other words, engagement is about the purposeful involvement of “self” in the work (Rayton & Yalabik, 2014; Saks, 2011), and is influenced, as other work-related attitudes (e.g., job satisfaction, organizational commitment) by various contextual antecedents related to job characteristics (e.g., job control, feedback, variety) and by individual differences (e.g., achievement motivation, action orientation) (Salanova & Schaufeli, 2008). Aside from these theoretical arguments, empirical studies have also shown, in different contexts, that meaning of work may appear as an antecedent of work engagement, for example in its relationship with organizational commitment (Beukes & Botha, 2013; Geldenhuys, Laba, & Venter, 2014), transformational leadership (Ghadi, Fernando, & Caputi, 2013), or work-role fit (Rothmann & Hamukang’andu, 2013; Rothmann & Olivier, 2007; Van Zyl, Deacon, & Rothmann, 2010).

We are interested to uncover whether religiousness may be one of the individual differences that acts as an antecedent of work attitudes in general and of job engagement specifically, and we are interested in investigating the relation between meaning and engagement in a different variable mix, one that includes religiosity. Hence, we hypothesize that:

-

H3: .

Meaning of work is positively related to work engagement.

Performance is currently understood as being a multi-dimensional construct (Gunnesch-Luca & Moser, 2019), comprised of task performance (i.e., behaviors directly related to the attainment of individual objectives; Campbell, 1990), contextual performance (i.e., behaviors not directly related to individual objectives but that contribute to the advancement of the company as a whole; Borman & Motowidlo, 1993; Borman & Motowidlo, 1997) and adaptive performance (i.e., workplace adaptability; Sonnentag, Volmer, & Spychala, 2008). Contextual performance is in turn conceptualized as positive (organizational citizenship behaviors, OCB) and negative (counterproductive work behaviors, CWB). The literature supports the idea that employee engagement is an antecedent for OCB and has potential to drive OCB directly (Ariani, 2013; Kataria, Garg, & Rastogi, 2012), as well as indirectly, i.e., to mediate between various variables (job characteristics, leadership styles or dispositional characteristics) and OCB (Babcock-Roberson & Strickland, 2010; Bakker & Albrecht, 2018; Christian et al., 2011; Lyu, Zhu, Zhong, & Hu, 2016; Macey & Schneider, 2008). Other studies promote the idea of work engagement and OCB being same-level variables, acting either both as mediators (Meynhardt, Brieger, & Hermann, 2020) or being both consequences (Farid et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2016; Zhang, Guo, & Newman, 2017) in the interaction between different other variables in organizational settings.

Yet, the relationship between religiosity, work engagement and the performance domain (in this case, OCB) is still insufficiently documented in the literature (Ahmadi, Nami, & Barvarz, 2014; Albuquerque, Cunha, Martins, & Sá, 2014; Chawla & Guda, 2013; Garcia-Zamor, 2003; Houghton et al., 2016). Therefore, we take up this line of investigation and search for evidence for the fact that religiosity is significantly associated with an aspect of contextual performance, namely with OCB, through the mediating effect of work engagement. We hypothesize that:

-

H4: .

Work Engagement is positively related to OCB.

In summary, the current study was undertaken to address a number of limitations in the literature. First, opposed to other studies that tended to focus on religiosity in general, we focus on workplace religiosity insomuch as religiosity is embraced and present in the form of beliefs or practices (and not concealed, avoided or even denied by the employee) in the workplace. Second, we propose and test a mechanism through which religiosity generates meaning in the workplace, and thus influences important work attitudes and behaviors. We examine if religiosity directly influences OCB or if it influences OCB only indirectly via meaningful work and engagement.

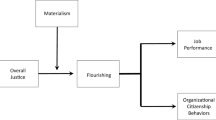

Our theoretical model (Fig. 1) hypothesized that religiousness will have a positive impact only if is embraced and manifested at work; this is first associated with construction of meaning of work and then with positive attitudes towards work and further with desirable behaviors at work. Our study therefore explored the pathways that connect religiosity to positive work outcomes (OCB) via the religious beliefs embraced by employees (faith at work), meaning making (through religious beliefs) and work engagement. Therefore, our fifth hypothesis is:

-

H5: .

Work engagement and meaningful work mediate the relationship between religiosity and OCB.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 246 Romanian speaking adults (34.6% male n = 85; 65.4% female n = 161; M age = 36.77 years, SD age = 8.11). The majority of participants were Eastern Orthodox Christians (81.7%) followed by other Christian religions (6.6%) and non-religious (11.7%). The marital status reported by participants was: married (53.3%), in a stable relationship (23.6%), single (15.4%), divorced/separated (5.7%) and other situations (2%). For those married and in a stable relationship the duration of their relation had an average of M = 9.98 (SD = 7.86) years. In terms of education, 14 of the participants (5.7%) were high school graduates, 112 had bachelor’s degree (45.5%), 111 (45.1%) had master’s degree and 9 of them (3.7%) had PhD studies. A wide range of occupations were represented in the sample, including accounting professionals, economists, banking specialists and managers, information technology specialists, administrative assistants, accounts managers and sales personnel, human resources specialists and managers, medical and pharmaceutical personnel, engineers and technical professionals, military personnel.

Procedure

Participants were recruited using the convenience sampling method; they responded to an e-mail invitation sent on a professional social network (LinkedIn) to self-administer a battery of questionnaires on a web-hosted survey page. The e-mail invitation was sent to approximately 2300 employees (all the Romanian-speaking employees from a former “generalist” head-hunter’s personal LinkedIn network – with contracts in all industries and the majority multinational and large local companies active in the Romanian market) and the 246 respondents represent a response rate of about 10%. Previously to enrolling into the study, participants received no details regarding the exact topic of the study: the invitation did not mention that the study referred to religiosity, in order to avoid self-selection bias for religiously oriented participants. All participants gave their informed consent in participating to the study and data were collected anonymously.

Measures

Religiousness

Being one of the most frequently used “general” religiosity scale, we opted for the Duke University Religion Index (DUREL, Koenig, Meador, & Parkerson, 1997) to measure religiosity. The scale comprises five items (e.g., “In my life, I experience the presence of the Divine”): the first two items measure the organizational respectively non-organizational dimension of religion, whereas the last three items are on intrinsic or subjective religiosity (Hill & Hood, 1998; Koenig & Büssing, 2010). A Romanian version of this scale was developed using the translation-back-translation procedure (Brislin, 1986) for this study. The translation was conducted by a team of professional translators (comprising fluent speakers of the Romanian and English languages, as well as psychologists). Items were scaled differently, depending on content: the first item on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (“more than once/week”) to 6 (“never”); the second item on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 (“more than once a day”) to 6 (“rarely or never”); the last three items on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (“definitely true for me”) to 5 (“definitely not true”). The Alpha Cronbach coefficient was .90 (see Table 1).

Faith at Work

The Faith at Work Scale (FWS, Lynn et al., 2009), which was used to measure faith at work, is a 15-item measure of Judeo-Christian workplace religion (e.g., “I sense that God empowers me to do good things at work”). We chose this scale because our participants were Romanians – a country where, according to the latest (2011) population census, over 90% of the population identify themselves as Christians (INS, 2013). A Romanian version of this scale was also developed using the same translation-back-translation procedure (Brislin, 1986). Items were scaled on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (“Never or Infrequently”) to 5 (“Always or Frequently”). Cronbach’s α for scores on the FWS was .95 (see Table 1).

Meaningful Work

The Work and Meaning Inventory (WAMI, Steger et al., 2012) was used to measure “meaningful work”. This is a 10-item scale (e.g., “My work helps me make sense of the world around me”) that measures three aspects: the experience of positive meaning in work, sensing that work is a “key avenue for making meaning” and the desire to make a positive impact on the greater good. For this scale also, we used a Romanian version, developed using translation-back-translation procedure (Brislin, 1986), as well. Items were scaled on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (“Absolutely Untrue”) to 5 (“Absolutely True”). Cronbach’s α for scores on the WAMI was .87 (see Table 1).

Work Engagement

Work engagement was measured using the 17-items version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES, Schaufeli & Bakker, 2003) (e.g., “At my work, I feel bursting with energy”). The Romanian version of this scale (Vîrgă, Zaborilă, Sulea, & Maricuțoiu, 2009) was used. Items were scaled on a 7-point Likert scale from 0 (“Never”) to 6 (“Always/Every day”). Cronbach’s α for the UWES total score was .95 (see Table 1).

Work Behavioral Outcomes

OCB was measured using the long form (20 items) of the Organizational Citizenship Behavior Checklist (OCB-C 20, Fox & Spector, 2009) (e.g., “Offered suggestions for improving the work environment”). Items were scaled on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (“Never”) to 5 (“Every day”). The Alpha Cronbach coefficient was .92 (see Table 1).

Analytic Strategy

First, as all the scales used in this study are well established in the literature, a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted for each variable, to test if the data fits the hypothesized (unidimensional) models underlying each of these constructs (see Table 2 and also Appendices Tables 4 and 5 – for details). These analyses computed Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Chi-Square (χ2).

Then, we examined basic correlations between our variables and then proceeded to test our path model using Mplus 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2012). Our statistical model included direct and indirect paths from the predictor variable (i.e., general religiosity) to the outcome variable (i.e., OCB) via mediator variables (i.e., faith at work, meaningful work and work engagement). We used the maximum-likelihood method of parameter estimation to examine simultaneous multiple direct and indirect predicted paths (Holmbeck, 1997) and interpreted the global indices of fit between our theoretical model and the obtained data (chi-squared value, the root-mean-square error of approximations [RMSEA], and the comparative fit index [CFI]).

Results

The results of the CFA show that all items loaded significantly on the expected constructs. The overall goodness-of-fit indices were found to be within the recommended range (for details, see Hu & Bentler, 1999): for DUREL (χ2[10] = 1520.977; RMSEA = 0.035; CFI = 0.999; TLI = 0.998; SRMR = 0.021); FWS (χ2 [105] = 4522.389; RMSEA = 0.000; CFI = 1.000; TLI = 1.000; SRMR = 0.005); WAMI (χ2 [45] = 5510.911; RMSEA = 0.141; CFI = 0.971; TLI = 0.960; SRMR = 0.058); UWES (χ2 [136] = 5620.941; RMSEA = 0.083; CFI = 0.967; TLI = 0.958; SRMR = 0.071) and for OCB-C (χ2 [190] = 2150.319; RMSEA = 0.046; CFI = 0.955; TLI = 0.949; SRMR = 0.043). We have concluded that the data collected has a very good to acceptable fit with the unidimensional structure hypothesized for each variable.

Means, standard deviations and Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the study variables are presented in Table 1.

After examining the bivariate correlation between our variables (Table 3), we found that correlations were in the direction we hypothesized. Religiosity is positively related to faith at work (r = .82, p < .01), meaning of work (r = .16, p < .05) and OCB (r = .17, p < .01). We did not find a statistically significant association between religiosity (in general) and work engagement but we found a statistically significant positive correlation between faith at work and work engagement (and all the other variables as well). We also found positive correlations between meaning of work, work engagement and OCB. This all suggests that we can proceed to a more comprehensive investigation (through path analysis) in order to verify our hypotheses: that if an individual holds religious beliefs then these must be manifested at work (e.g., faith at work) before they will impact his/her work attitudes.

Our model presents the following indices (Fig. 2): RMSEA = .00; CFI = 1.00; SRMR = .00; χ2 = 458.25, p < .001; N = 229). Although a significant chi-square result suggests a misspecification of the model (Chen, Curran, Bollen, Kirby, & Paxton, 2008), chi-square tests are susceptible to sample size, particularly when N = 200 and above (Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Schumacker & Lomax, 2010). In these cases, researchers are led to consider other fit indices: RMSEA (cutoff points of less than .06 or .05 have been proposed to indicate a good fit; Byrne, 2001; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Schumacker & Lomax, 2010) or CFI (cutoff points indicating a good fit are of .90 or .95; Byrne, 2001; Schumacker & Lomax, 2010). Thus, our model demonstrated a good fit. Figure 2 shows the unstandardized coefficient and standard errors for the statistically significant paths of interest. Religiosity (in general) predicted faith at work (b = 2.04, SE = .08, p < .01), supporting our first hypothesis that religiosity (in general) is positively related to faith at work. This was positively related to meaning of work (b = .25, SE = .05, p < .01), thus supporting our second hypothesis that stated that: faith at work is positively related to meaning of work. Subsequently meaning of work predicted work engagement (b = .08, SE = .01, p < .01) that was positively related to OCB (b = 3.85, SE = 1.08, p < .01) supporting thus our third and fourth hypothesis (that is: meaning of work is positively related to work engagement and the one that stated that: work engagement is positively related to OCB).

Although we did not find support for the direct effect of religiosity on contextual work performance (in our case OCB) we did find support for indirect effects via faith at work, meaning of work and work engagement. Thus, we found support for our fifth hypothesis that suggested the mediating effect of work engagement and meaningful work in the relationship between religiosity and OCB. Specifically, we found a significant total indirect effect of religiosity on OCB via faith at work, meaning making and work engagement (b = .81, SE = .20, p < .001).

Discussion

Previous empirical research on work-faith integration is limited and originates in conceptual controversy (Houghton et al., 2016), with scholars habitually favoring the concept of spirituality in the workplace over the one of religiosity (see also Day, 2005). Nevertheless, in the past years, the interest to explore the impact of faith in the workplace began to gain more terrain in organizational studies (Benefiel et al., 2014). In order to advance the knowledge in this field, we proposed and tested a series of mediators that help clarify relationships between these variables. Specifically, we developed a path analysis model (Fig. 1) to explore the relationship between religiousness, faith at work, meaning at work (influenced by faith), work engagement and an aspect of work performance (OCB). Results (Fig. 2) indicated that faith embraced and manifested in the workplace by religious individuals is first associated with conveying a sense of meaning at work and then is further associated to positive work-related attitudes (work engagement) and behaviors (OCB). Also, while the mediating role of work engagement on the relationship between workplace spirituality (not necessarily religiosity) and OCB was suggested previously (Ahmad & Omar, 2015), to the best of our knowledge this is the first study to offer empirical evidence for the mediating role of faith at work, meaning making and work engagement in the relationship between religiosity and OCB.

We therefore clarify some of the debates in the literature. First, confirming the perspective according to which religion is efficacious to the degree that is integrated into the lives of the religious (Pargament, 2002), our results show that the religious beliefs of employees have to be manifested in work settings (faith at work) before they will impact their working life (and ultimately their contextual performance at work). Thus, as we have already mentioned, it is not sufficient for employees to have such beliefs in their private life and to only manifest them outside of work contexts; the assumption that employees will automatically manifest their faith at work just because they are religious (Hicks, 2003; Miller, 2007) is incorrect, as shown in our path model. Not all religious employees choose to manifest their religiousness into the workplace (see, Glavaš, 2017), potential explanations for this might be the fear of prejudice or discrimination, social embarrassment or the lack of internalizing religious values, etc. (factors that, of course, should be validated by further research). Additional studies are needed on these findings, especially in order to understand how religious beliefs impact not just work but also family life or other social and/or individual activities. Holding religious beliefs is not enough for predicting positive outcomes in interacting with others in various social contexts but acting upon these beliefs and integrating them into activities and the interactions with others (irrespective of context) might be the decisive factor.

Secondly, meaning making proved to be a mediator in the relation between faith at work and work engagement suggesting that making sense of one’s own work through the lens of religion leads to greater work engagement and consequently to positive work outcomes in the form of OCBs. This fact adds additional clarification to the work engagement literature, specifically to the Job Demands-Resources Model (JD-R, Bakker & Demerouti, 2007) where we consider faith at work (viewed from the individual-centered perspective, as addressed in this study) to be one of the many personal resources (alongside resilience, self-efficacy, optimism, etc.; Schaufeli, 2017). Another conclusion of the present study, related to the JD-R model, is the fact that meaning making is a key variable mediating the relationship between antecedents (in our case, faith at work) and work engagement, leading to various organizational outcomes (in our case, OCB). Thus, meaningful work appears to facilitate the transformation of antecedents (job and personal resources) into engagement. This phenomenon could help explain some of the ambiguities in the extant literature, that sometimes suggest a partial mediation, other times a full mediation of work engagement in the relationship between various antecedents (e.g., optimism, flexibility, etc.) and organizational outcomes (e.g., performance, proactive behavior) (Beukes & Botha, 2013; Hoole & Bonnema, 2015; Korunka, Kubicek, Schaufeli, & Hoonakker, 2009; Salanova & Schaufeli, 2008). It is possible that engagement fails to fully mediate these relationships when the antecedents (resources and demands from the JD-R model) do not contribute to sense-making related to work (that could, in turn, lead to work engagement). Traditionally, meaning of work was considered at the very most a job resource in the JD-R model, but if the suggested prominent role played by meaningful work will be confirmed by other studies, this would mandate a change in the JD-R model to accommodate meaningful work as a mediator in the relationship between various resources and demands and work engagement. Further research is however needed to confirm this addition to the JD-R model.

Third, our results support, as expected (Christian et al., 2011; Macey & Schneider, 2008), the fact that engagement relates to, and is an antecedent of OCB. Engaged employees who manage to convey meaning to their work through their religious beliefs appear to be more prone towards undertaking extra-role behaviors, approaching their work constructively and involving themselves in positive interactions with others. Our findings, while agreeing with the fact that work engagement impacts proactive work behavior (Salanova & Schaufeli, 2008), bring also clarifications concerning one of the mechanisms that makes this influence possible. Faith at work is first associated with meaningful work, and then with work engagement, further being associated to positive workplace behaviors such as OCB.

As noted, there is a controversy in the literature regarding whether spirituality is an antecedent of OCB (Movassagh & Oreizi, 2014; Nasurdin, Nejati, & Mei, 2013), or rather OCB is an antecedent and not an outcome of workplace spirituality (Pawar, 2009). This controversy could be partially clarified by our results, that present the mechanism leading from religiosity to OCB, with religiosity as a possible antecedent. This suggests that spiritual manifestations (either in the form of religiosity, or workplace spirituality) are an antecedent and not an outcome of OCB.

In terms of practical implications for organizations, our findings suggest that encouraging workplaces to be more receptive to individual (including religious) personal beliefs and values may lead to employees who are better adapted to the company and its working environment, as well as more proactive in assuming extra tasks and providing help to coworkers. Far from being an undesirable aspect – as may be assumed in today’s mostly secular organizations, religiousness may lead to a more self-aware employees who have a more coherent perspective regarding their role in the company and their contribution in the workplace. Another practical implication refers to the possibility of customizing human resources policies to accommodate potential request to integrate religion in the working life (e.g., compliance with fasting periods, flexible schedule hours to accommodate the need to meditate, pray, attend religious service, etc.). On the other hand, organizations may need to be vigilant to ensure that the expression of faith at work does not have negative aspects (e.g., employees preaching to coworkers about their religious beliefs, judging others who have a different faith, etc.).

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

The current study has a number of limitations. First, the use of self-report carries with it a risk for common-method bias. Second, the correlative nature of our study limits our ability to infer causality. Third, because the study used a non-representative convenience sample, generalizability of these results is questionable. Fourth, the focus of this study was on Romanian Orthodox Christians, and there is need to reproduce these results on samples comprising other Christian traditions and other religions, as well as various other nations and cultures.

Our findings provide evidence for the importance of empirical inquiry on the topic of religiosity at work. Further research is needed on other work-related attitudes and behaviors that might be influenced by religiosity (e.g., organizational commitment, job satisfaction, job involvement, etc.). Future research could also explore other mediating factors that might impact the relation between religiosity and other performance aspects (e.g., counterproductive work behaviors).

Another line of investigation might contemplate to further examine the relation between faith at work and the Job Demands-Resources Model (JD-R, Bakker & Demerouti, 2007), following our suggestions that faith at work (viewed here from the individual-centered perspective) may be one important personal resource. Our findings showing that meaning making acts as a mediator in the relationship between antecedents (in our case, faith at work) and work engagement might be further explored in relation with other antecedents and could lead to an update in the JD-R model. Last but not least, further investigations are needed to unveil the relation between faith at work and other personal resources (such as optimism or flexibility) and their impact on task, contextual and adaptive performance at work.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Ahmad, A., & Omar, Z. (2015). Improving organizational citizenship behavior through spirituality and work engagement. American Journal of Applied Sciences, 12(3), 200–207. https://doi.org/10.3844/ajassp.2015.200.207.

Ahmad, Z., Rahim, N. A., Chulan, M., Ab Wahab, S. A., & Noor, A. N. (2019). Islamic work ethics and organizational citizenship behavior among Muslim employees in educational institutions. Proceedings of the Second International Conference on the Future of ASEAN (ICoFA) 2017. 1, pp. 455-464. Singapore: Springer.

Ahmadi, S., Nami, Y., & Barvarz, R. (2014). The relationship between spirituality in the workplace and organizational citizenship behavior. Procedia - Social Behavioral Sciences. 114, pp. 262-264. Istanbul: Elsevier ltd. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.695.

Albuquerque, I. F., Cunha, R. C., Martins, L. D., & Sá, A. B. (2014). Primary health care services: Workplace spirituality and organizational performance. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 27(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-11-2012-0186.

Ariani, D. W. (2013). The relationship between employee engagement, organizational citizenship behavior, and counterproductive work behavior. International Journal of Business Administration, 4(2), 46–56.

Ashmos, D. P., & Duchon, D. (2000). Spirituality at work: A conceptualization and measure. Journal of Management Inquiry, 9(2), 134–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/105649260092008.

Ayoun, B., Rowe, L., & Yassine, F. (2015). Is workplace spirituality associated with business ethics? International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 27(5), 938–957. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-01-2014-0018.

Babcock-Roberson, M. E., & Strickland, O. J. (2010). The relationship between charismatic leadership, work engagement, and organizational citizenship behaviors. The Journal of Psychology, 144, 313–326.

Bakker, A. B., & Albrecht, S. (2018). Work engagement: current trends. Career Development International, 23(1), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-11-2017-0207.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940710733115.

Batson, C. D., & Stocks, E. L. (2004). Religion: Its core psychological functions. In S. L. Koole & T. Pyszczynski (Eds.), Handbook of experimental existential psychology (pp. 141–155). New York: Guilford Press.

Benefiel, M., Fry, L. W., & Geigle, D. (2014). Spirituality and religion in the workplace: History, theory, and research. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 6(3), 175–187. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036597.

Berg, J. M., Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2010). Perceiving and responding to challenges in job crafting at different ranks: When proactivity requires adaptivity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31, 158–186.

Beukes, I., & Botha, E. (2013). Organisational commitment, work engagement and meaning of work of nursing staff in hospitals. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 39(2), 1–10.

Borman, W. C., & Motowidlo, S. J. (1993). Expanding the criterion domain to include elements of contextual performance. In N. Schmitt & W. C. Borman (Eds.), Personnel selection in organizations (pp. 71–98). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Borman, W. C., & Motowidlo, S. J. (1997). Task performance and contextual performance: The meaning for personnel selection research. Human Performance, 10(2), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327043hup1002_3.

Brislin, R. W. (1986). The wording and translation of research instruments. In W. J. Lonner & J. W. Berr (Eds.), Field methods in cross-cultural research (pp. 137–164). Newbury Park: Sage.

Brooke, C., & Parker, S. (2009). Researching spirituality and meaning in the workplace. The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 7(1), 1–10.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park: Sage.

Bunderson, J. S., & Thompson, J. A. (2009). The call of the wild: Zookeepers, callings, and the dual edges of deeply meaningful work. Administrative Science Quarterly, 54, 32–57.

Byrne, B. M. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (1st ed.). Mahwah: Erlbaum. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203726532.

Campbell, J. P. (1990). Modeling the performance prediction problem in industrial and organizational psychology. In M. D. Dunnette, & L. M. Hough, Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 687-732). Palo Alto: Consulting psychologists press.

Chawla, V., & Guda, S. (2013). Workplace spirituality as a precursor to relationship-oriented selling characteristics. Journal of Business Ethics, 115(1), 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1370-y.

Chen, F., Curran, P. J., Bollen, K. A., Kirby, J., & Paxton, P. (2008). An empirical evaluation of the use of fixed cutoff points in RMSEA test statistic in structural equation models. Sociological Methods & Research, 36(4), 462–494. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124108314720.

Christian, M. S., Garza, A. S., & Slaughter, J. E. (2011). Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Personnel Psychology, 64(1), 89–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2010.01203.x.

Curlin, F. A., Dugdale, L. S., Lantos, J. D., & Chin, M. H. (2007). Do religious physicians disproportionately care for the underserved? The Annals of Family Medicine, 5(4), 353–360.

Dahinden, J., & Zittoun, T. (2013). Religion in meaning making and boundary work: Theoretical explorations. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 47(2), 185–206.

Daniel, J. L. (2010). The effect of workplace spirituality on team effectiveness. Journal of Management Development, 29(5), 442–456. https://doi.org/10.1108/02621711011039213.

Day, N. E. (2005). Religion in the workplace: Correlates and consequences of individual behavior. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 2(1), 104–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766080509518568.

Dik, B. J., & Duffy, R. D. (2009). Calling and vocation at work. The Counseling Psychologist, 37(3), 424–450.

Duchon, D., & Plowman, D. A. (2005). Nurturing the spirit at work: Impact on work unit performance. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(5), 807–833. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.07.008.

Emmons, R. A., & Crumpler, C. A. (1999). Religion and spirituality? The role of sanctification and the concept of god. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 9, 17–24.

Epstein, E. M. (2002). Religion and business – The critical role of religious traditions in management education. Journal of Business Ethics, 38(1–2), 91–96. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015712827640.

Farid, T., Iqbal, S., Ma, J., Castro-González, S., Khattak, A., & Khan, M. K. (2019). Employees’ perceptions of CSR, work engagement, and organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating effects of organizational justice. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(10), 17–31.

Fletcher, S. K. (2004). Religion and life meaning: Differentiating between religious beliefs and religious community in constructing life meaning. Journal of Aging Studies, 18(2), 171–185.

Fox, S., & Spector, P. E. (2009). Organizational Citizenship Behavior Checklist (OCB-C). Retrieved from http://shell.cas.usf.edu/~pspector/scales/ocbcpage.html.

Fry, L. W. (2003). Toward a theory of spiritual leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 14, 693–727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2003.09.001.

Furnham, A. (1990). The Protestant work ethic: The psychology of work-related beliefs and behaviors. London: Routledge.

Garcia-Zamor, J.-C. (2003). Workplace spirituality and organizational performance. Public Administration Review, 63(3), 355–363. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6210.00295.

Geldenhuys, M., Laba, K., & Venter, C. M. (2014). Meaningful work, work engagement and organisational commitment. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 40(1), 01–10.

Ghadi, M. Y., Fernando, M., & Caputi, P. (2013). Transformational leadership and work engagement: The mediating effect of meaning in work. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 34(6), 532–550. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-10-2011-0110.

Giacalone, R. A., & Jurkiewicz, C. L. (2003). Toward a science of workplace spirituality. In R. A. Giacalone & C. L. Jurkiewicz (Eds.), Handbook of workplace spirituality and organizational performance (pp. 3–28). New York: M.G. Sharpe.

Glavaš, D. (2017). Christian on Sunday and atheist on Monday: Bridging the faith and work gap in Croatian culture. Kairos (English ed.), 11(1), 29-66. https://doi.org/10.32862/k.11.1.2.

Gotsis, G., & Kortezi, Z. (2008). Philosophical foundations of workplace spirituality: A critical approach. Journal of Business Ethics, 78, 575–600. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9369-5.

Grant, A. M. (2007). Relational job design and the motivation to make a prosocial difference. Academy of Management Review, 32(2), 393–417. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.24351328.

Grant, D., O'Neil, K., & Stephens, L. (2004). Spirituality in the workplace: New empirical directions in the study of the sacred. Sociology of Religion, 65(3), 265–283.

Gunnesch-Luca, G., & Moser, K. (2019). Development and validation of a German language unit-level organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) scale. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000558.

Gupta, M., Kumar, V., & Singh, M. (2014). Creating satisfied employees through workplace spirituality: A study of the private insurance sector in Punjab (India). Journal of Business Ethics, 122(1), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1756-5.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1976). Motivation through the design of work: Test of a theory. Organization Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 16, 250–279.

Halbesleben, J. R. (2010). A meta-analysis of work engagement: Relationships with burnout, demands, resources, and consequences. In A. B. Bakker & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), Work engagement: A handbook of essential theory and research (pp. 102–117). New York: Psychology Press, Taylor & Francis Group.

Hamilton, D. M., & Jackson, M. H. (1998). Spiritual development: Paths and processes. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 25(4), 262–270.

Haq, I. U., De Clercq, D., Azeem, M. U., & Suhail, A. (2018). The interactive effect of religiosity and perceived organizational adversity on change-oriented citizenship behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 1-15.

Hayden, R. W., & Barbuto, J. E. (2011). Expanding a framework for a non-ideological conceptualization of spirituality in the workplace. Institute of Behavioral and Applied Management, 12(2), 142–155.

Hicks, D. A. (2003). Religion and the workplace: Pluralism, spirituality, leadership. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hill, J. S. (2007). Religion and the shaping of east Asian management styles: A conceptual examination. Journal of Asia-Pacific Business, 8(2), 59–88.

Hill, P. C., Pargament, K. I., Hood, R. W., McCullough, M. E., Swyers, J. P., Larson, D. B., & Zinnbauer, B. J. (2000). Conceptualizing religion and spirituality: Points of commonality, points of departure. Journal for the Theory of Social Behavior, 30(1), 51–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5914.00119.

Hill, P., & Hood, R. (1998). Measures of religiosity. Birmingham: Religious Education Press.

Holmbeck, G. N. (1997). Toward terminological, conceptual, and statistical clarity in the study of mediators and moderators: Examples from the child-clinical and pediatric psychology literatures. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65(4), 599–610. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.65.4.599.

Hoole, C., & Bonnema, J. (2015). Work engagement and meaningful work across generational cohorts. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(1), 1–11.

Houghton, J. D., Neck, C. P., & Krishnakumar, S. (2016). The what, why, and how of spirituality in the workplace revisited: A 14-year update and extension. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 13(3), 177–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2016.1185292.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.

INS, (Institutul National de Statistica/ National Statistics Institute). (2013). Recensamantul populatiei si al locuintelor (the census of population and Housholds). Bucharest: Institutul National de Statistica.

Jones, H. B. (1997). The Protestant ethic: Weber’s model and the empirical literature. Human Relations, 50(7), 757–778.

Karakas, F. (2010). Spirituality and performance in organizations: A literature review. Journal of Business Ethics, 94(1), 89–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0251-5.

Kataria, A., Garg, P., & Rastogi, R. (2012). Employee engagement and organizational effectiveness: The role of organizational citizenship behavior. International Journal of Business Insights & Transformation, 6(1), 102–113.

Kim, W., Kolb, J. A., & Kim, T. (2013). The Relationship Between Work Engagement and Performance: A Review of Empirical Literature and a Proposed Research Agenda. Human Resource Development Review, 12(3), 248–276. 10.1177%2F1534484312461635.

King, J. E., & Crowther, M. R. (2004). The measurement of religiosity and spirituality. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 17(1), 83–101. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810410511314.

Koenig, H. G., & Büssing, A. (2010). The Duke University religion index (DUREL): A five-item measure for use in Epidemological studies. Religions, 1, 78–85. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel1010078.

Koenig, H. G., McCullough, M. E., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Handbook of religion and health. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Koenig, H. G., Meador, K. G., & Parkerson, G. (1997). Religion index for psychiatric research. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 154, 885–886.

Koenig, H. G., Zaben, F. A., Khalifa, D. A., & Shohaib, S. A. (2015). Measures of religiosity. In G. J. Boyle, D. H. Saklofske, & G. Matthews (Eds.), Measures of personality and social psychological constructs (pp. 530–561). London: Academic Press.

Korunka, C., Kubicek, B., Schaufeli, W. B., & Hoonakker, P. (2009). Work engagement and burnout: Testing the robustness of the job demands-resources model. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(3), 243–255.

Krishnakumar, S., & Neck, C. P. (2002). The “what”, “why” and “how” of spirituality in the workplace. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 17(3), 153–164. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940210423060.

Kutcher, E. J., Bragger, J. D., Rodriguez-Srednicki, O., & Masco, J. L. (2010). The role of religiosity in stress, job attitudes, and organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(2), 319–337.

Lips-Wiersma, M. (2002). The influence of spiritual “meaning-making” on career behavior. The Journal of Management Development, 7(8), 497–519.

Lynn, M. L., Naughton, M. J., & VanderVeen, S. (2009). Faith at work scale (FWS): Justification, development, and validation of a measure of Judaeo-Christian religion in the workplace. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(2), 227–243. https://doi.org/10.1177/105649260092008.

Lynn, M. L., Naughton, M. J., & VanderVeen, S. (2011). Connecting religion and work: Patterns and influences of work-faith integration. Human Relations, 64(5), 675–701.

Lyu, Y., Zhu, H., Zhong, H. J., & Hu, L. (2016). Abusive supervision and customer-oriented organizational citizenship behavior: The roles of hostile attribution bias and work engagement. nternational Journal of Hospitality Management, 53, 69-80.

Macey, W. H., & Schneider, B. (2008). The meaning of employee engagement. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 1(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9434.2007.0002.x.

Marques, J., Dhiman, S., & King, R. (2005). Spirituality in the workplace: Developing an integral model and a comprehensive definition. ournal of. American Academy of Business, Cambridge, 7(1), 81–91.

Marques, J., Satinder, D., & King, R. (2009). The workplace and spirituality: New perspectives on research and practice. Woodstock: Skylight Paths.

Martos, T., Thege, B. K., & Steger, M. F. (2010). It’s not only what you hold, it’s how you hold it: Dimensions of religiosity and meaning in life. Personality and Individual Differences, 49(8), 863–868. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.07.017.

May, D. R., Gilson, L., & Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77, 11–37.

Meynhardt, T., Brieger, S. A., & Hermann, C. (2020). Organizational public value and employee life satisfaction: The mediating roles of work engagement and organizational citizenship behavior. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 31(12), 1560–1159. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1416653.

Michaelson, C. (2005). “I want your shower time!”: Drowning in work and the erosion of life. Business and Professional Ethics Journal, 24(4), 7–26 Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/27801395.

Miller, D. W. (2007). God at work: The history and promise of the faith at work movement. New York: Oxford University Press.

Miller, D. W., & Ewest, T. (2013). The present state of workplace spirituality: A literature review considering context, theory, and measurement/assessment. Journal of Religious & Theological Information, 12(1–2), 29–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/10477845.2013.800776.

Milliman, J., Czaplewski, A. J., & Ferguson, J. (2003). Workplace spirituality and employee work attitudes: An exploratory empirical assessment. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 16(4), 426–447. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810310484172.

Mitroff, I. I., & Denton, E. A. (1999). A study of spirituality in the workplace. Sloan Management Review, 40(4), 83–92.

Moberg, D. O. (2002). Assessing and measuring spirituality: Confronting dilemmas of universal and particular evaluative criteria. Journal of Adult Development, 9(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1013877201375.

Movassagh, M. T., & Oreizi, H. R. (2014). Multiple relationships between perceived organizational justice and workplace spirituality with organizational citizenship behaviors. Journal of Psychology, 18(2), 176–194.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998-2012). Mplus User’s Guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

Nash, L., & McLennan, S. (2001). Church on Sunday, work on Monday: The challenge of fusing Christian values with business life. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Nasurdin, A. M., Nejati, M., & Mei, Y. K. (2013). Workplace spirituality and organizational citizenship behaviour: Exploring gender as a moderator. South African Journal of Business Management, 44, 61–74.

Neal, J. (2013). Faith and spirituality in the workplace: Emerging research and practice. In J. Neal (Ed.), Handbook of faith and spirituality in the workplace (pp. 3–18). New York: Springer.

Neff, J. A. (2006). Exploring the dimensionality of “religiosity” and “spirituality” in the Fetzer multidimensional measure. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 45(3), 449–459.

Nelson, J. M. (2009). Psychology, religion, and spirituality. New York: Springer Science & Business Media.

Olowookere, E. I. (2014). Influence of religiosity and organizational commitment on organizational citizenship Behaviours: A critical review of literature. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 1(3), 48–63.

Osman-Gani, A. M., Hashim, J., & Ismail, Y. (2013). Establishing linkages between religiosity and spirituality on employee performance. Employee Relations, 35(4), 360–376. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-04-2012-0030.

Pargament, K. I. (2002). The bitter and the sweet: An evaluation of the costs and benefits of religiousness. Ps-vchological Inquiry, 13(3), 168–181.

Park, C. L. (2005). Religion and meaning. In R. F. Paloutzian & C. L. Park (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality (pp. 295–314). New York: Guilford Press.

Pawar, B. S. (2009). Individual spirituality, workplace spirituality and work attitudes: An empirical test of direct and interaction effects. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 30(8), 759–777. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730911003911.

Pawar, B. S. (2016). Workplace spirituality and employee well-being: An empirical examination. Employee Relations, 38(6), 975–994. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-11-2015-0215.

Pratt, M. G., & Ashforth, B. E. (2003). Fostering meaningfulness in working and at work. In K. S. Cameron, K. S. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship (pp. 309–327). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc..

Rayton, B. A., & Yalabik, Z. Y. (2014). Work engagement, psychological contract breach and job satisfaction. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(17), 2382–2400. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2013.876440.

Roberson, L. (1990). Functions of work meanings in organizations: Work meanings and work motivation. In A. P. Brief & W. R. Nord (Eds.), Meanings of occupational work (pp. 107–134). Lexington: Lexington Books.

Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91–127.

Rothmann, S., & Hamukang’andu, L. (2013). Callings, work role fit, psychological meaningfulness and work engagement among teachers in Zambia. South African Journal of Education, 33(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v33n2a699.

Rothmann, S., & Olivier, A. L. (2007). Antecedents of work engagement in a multinational company. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 33(3), 49–56.

Saks, A. M. (2011). Workplace spirituality and employee engagement. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 8(4), 317–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766086.2011.630170.

Salanova, M., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2008). A cross-national study of work engagement as a mediator between job resources and proactive behaviour. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 11(1), 116–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190701763982.

Schaufeli, W. B. (2017). Applying the job demands-resources model: A ‘how to’ guide to measuring and tackling work engagement and burnout. Organizational Dynamics, 46(2), 120–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2017.04.008.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2003). Test manual for the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale. Unpublished manuscript, Utrecht University, the Netherlands. Retrieved from http://www.schaufeli.com/

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:101563093.

Schnell, T., & Becker, P. (2006). Personality and meaning in life. Personality and Individual Differences, 41(1), 117–129.

Schumacker, R. E., & Lomax, R. G. (2010). A beginners guide to structural equation. New York: Routledge.

Scott, T. L. (2002). Choices, constraints, and calling: Conservative protestant women and the meaning of work in the US. International journal of sociology and social policy, 22(1/2/3), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443330210789942.

Silberman, I. (2005). Religion as a meaning system: Implications for the new millennium. Journal of Social Issues, 61, 641–663.

Singh, S. K., Burgess, T. F., Heap, J., Zaabi, M. S., Ahmad, K. Z., & Hossan, C. (2016). Authentic leadership, work engagement and organizational citizenship behaviors in petroleum companyv. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management., 65(6), 811–830.

Sonnentag, S., Volmer, J., & Spychala, A. (2008). Job performance. In J. Barling & C. L. Cooper (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational behavior: Volume I - micro approaches (pp. 427–447). London: SAGE Publications Ltd.. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781849200448.

Steger, M. F., & Dik, B. J. (2010). Work as meaning. In P. A. Linley, S. Harrington, & N. Page (Eds.), Oxford handbook of positive psychology and work (pp. 131–142). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Steger, M. F., Dik, B. J., & Duffy, R. D. (2012). Measuring meaningful work: The work and meaning inventory (WAMI). Journal of Career Assessment, 20(3), 322–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072711436160.

Šverko, B., & Vizek-Vidović, V. (1995). Studies on the meaning of work: Approaches, models, and some of the findings. In D. E. Super, B. Šverko, & C. M. Super (Eds.), Life roles, values, and careers (pp. 3–21). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Turner, R. P., Lukoff, D., Barnhouse, R. T., & Lu, F. G. (1995). A culturally sensitive diagnostic category in the DSM-IV. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 183(7), 435–444.

Van Zyl, L. E., Deacon, E., & Rothmann, S. (2010). Towards happiness: Experiences of work-role fit, meaningfulness and work engagement of industrial/organisational psychologists in South Africa. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 36(1), 1–10.

Vîrgă, D., Zaborilă, C., Sulea, C., & Maricuțoiu, L. (2009). Adaptarea în limba română a Scalei Utrecht de măsurare a implicării în muncă: examinarea validității și a fidelității [Romanian adaptation of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale: the examination of validity and reliability]. Psihologia Resurselor Umane, 7, 58–74.

Wrzesniewski, A. (2003). Finding positive meaning in work. In K. S. Cameron, J. E. Dutton, & R. E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline (pp. 296–308). Oakland: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Wrzesniewski, A., McCauley, C., Rozin, P., & Schwartz, B. (1997). Jobs, careers, and callings: People’s relations to their work. Journal of Research in Personality, 31, 21–33.

Wuthnow, R. (2004). Saving America?: Faith-based services and the future of civil society. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Zhang, Y., Guo, Y., & Newman, A. (2017). Identity judgements, work engagement and organizational citizenship behavior: The mediating effects based on group engagement model. Tourism Management, 61, 190–197.

Zinnbauer, B. J., & Pargament, K. L. (2005). Religiousness and spirituality. In R. Paloutzian & C. Park (Eds.), Handbook of the psychology of religion and spirituality (pp. 21–42). New York: Guilford Press.

Zinnbauer, B. J., Pargament, K. I., & Scott, A. B. (1999). The emerging meanings of religiousness and spirituality: Problems and prospects. Journal of Personality, 67(6), 889–919.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The current study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Bucharest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

David, I., Iliescu, D. The influence of religiosity and meaning making on work outcomes: A path analysis. Curr Psychol 41, 6196–6209 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01119-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01119-y