Abstract

Hybrid organisations combine different elements from the for-profit and non-profit domains, and they usually operate in a resource-scarce environment. For these reasons, they continuously face various resources constraints, yet their hybrid nature could be translated into an opportunity. The purpose of our study was to investigate how a hybrid organisation can overcome resource constraints in developing countries by exploiting their own hybrid nature. In the unique research setting offered by Kenyan social enterprises, we identified five creative approaches implemented by social enterprises. Finally, we present a grounded model that clearly explains which hybrid harvesting strategies can be implemented to overcome resource constraints, exploiting their hybrid potential. Our work contributes to knowledge about resource constraints in the social entrepreneurship literature and extends social bricolage theory. Limitations and future research approaches are also presented.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In recent years, both for-profit and non-profit organisations have been facing a blurring of boundaries between social and financial goals (Battilana and Lee 2014; Santos et al. 2015; Lashitew et al. 2018). This trend is setting the stage for the rise of so-called hybrid organisations, which combine different elements, logics, processes and forms of two or more conventional categories of organisations (private, public or non-profit organisations) (Haveman and Rao 2006; Mair and Marti 2006; Doherty et al. 2014). Among diverse hybrid organisations, social enterprises have been identified as the most representative setting for studying the hybrid organisation phenomenon (Doherty et al. 2014; Battilana and Lee 2014; Haigh et al. 2015).

The rise of social enterprises has received increasing, albeit polarised, attention from academics (Mair and Marti 2006; Servantie and Rispal 2018; Lashitew et al. 2018), who have stressed some of their unique features: specific legitimisation processes (Battilana and Dorado 2010; Jay 2013), hybrid business models (Yunus et al. 2010; Santos et al. 2015; Alberti and Varon Garrido 2017; Davies and Doherty 2018) and the risk of mission drift (Ebrahim et al. 2014; Doherty et al. 2014; Battilana and Lee 2014). Research on social enterprises has recently revealed an interest in processes of resource acquisition and the exploitation of these organisations. In fact, social enterprises usually compete in resource-scarce environments (Di Domenico et al. 2010; Linna 2013; Janssen et al. 2018) and face continually severe resource constraints (Desa and Basu 2013; Doherty et al. 2014; Hockerts 2015; Rawhouser et al. 2017).

Starting from the fact that the capacity to combine resources in a novel way is one of the main features of social enterprises (Mair and Marti 2006), some scholars have recently analysed the resource constraints of social enterprises through the lens of bricolage theory (Baker and Nelson 2005; Bacq et al. 2015; Janssen et al. 2018; Servantie and Rispal 2018). In fact, social enterprises can overcome resource constraints through bricolage by acquiring and managing resources on hand and by innovatively combining them (Desa and Basu 2013; Linna 2013; Ladstaetter et al. 2018). To better fit the nature of social enterprises, a specific social bricolage theory was developed (Di Domenico et al. 2010; Janssen et al. 2018). This theory enriches the original bricolage perspective by including three new, specific processes of social enterprises: the creation of social value, stakeholder participation and persuasion. Building on social bricolage theory, Ladstaetter et al. (2018) recently started a discussion about how social enterprises implement creative approaches to acquiring and managing resources. Even though social bricolage provides a useful perspective on social enterprises’ resource constraints, it remains unclear how social enterprises can effectively overcome their resource constraints.

Following the call by Ladstaetter et al. (2018) and other scholars (Doherty et al. 2014; Hockerts 2015; Rawhouser et al. 2017; Janssen et al. 2018; Lashitew et al. 2018) for additional research, our paper provides evidence about how social enterprises overcome their resource constraints. To address this issue, we designed a grounded model by analysing 13 case studies of social enterprises in Kenya, a fruitful venue for examining social enterprises characterised by several resource constraints (Rivera-Santos et al. 2015; OECD 2017; Drouillard 2017). Using Gioia et al.’s (2013) rigorous inductive methodology, we demonstrate how social enterprises leverage their hybrid nature under resource constraints through five types of creative implementations, which we collectively refer to as ‘hybrid harvesting strategies’. In developing our research, we contribute to the understanding of resource constraints in the social entrepreneurship field, generating additional knowledge about how social enterprises can address resource scarcity. We also contribute to social bricolage theory by detailing strategies used by social enterprises to leverage ‘persuasion’ and ‘creation of social value’, as suggested by Di Domenico et al. (2010). Our results also offer practical suggestions for entrepreneurs and managers of social enterprises and provide evidence about how, as proper of the harvest practices in agro-business, entrepreneurs and managers can leverage their hybrid nature and implement strategies to improve crops and harvests.

The paper is organised as follows. In the next section, we provide an introduction to the forefront of literature concerning social enterprises, bricolage and resource constraints. We then outline our methodology, explaining the research setting, data collection and data analysis. Further, we describe the grounded model, proceeding with an in-depth explanation of ‘hybrid harvesting strategies’ and their relationship with resource constraints. Finally, we discuss our results and highlight our conclusions, focusing on their implications for theory and practice. We also review the limitations of our analysis and suggest future research directions.

Resource Constraints in Social Enterprises: A Social Bricolage Perspective

In recent decades, social enterprises have become a relevant research field for both practitioners and academics (Bacq and Janssen 2011; Doherty et al. 2014; Battilana and Lee 2014; Janssen et al. 2018). Scholars agree on the definition of social enterprises as organisations that combine the goals and logics of profit and non-profit organisations (Mair and Marti 2006; Dacin et al. 2010; Yunus et al. 2010) and have recently documented how social enterprises face more resource constraints than traditional profit and non-profit organisations (Austin et al. 2006; Linna 2013; Battilana and Lee 2014; Costanzo et al. 2014; Lashitew et al. 2018). In fact, social enterprises typically face greater resource constraints than traditional organisations because they must manage the coexistence of two distinct missions (Battilana and Lee 2014; Davies and Doherty 2018; Lashitew et al. 2018) and primarily operate in a resource-scarce environment (Linna 2013; Doherty et al. 2014; Janssen et al. 2018). Further, scholars have documented how social enterprises face internal and external tensions that operationally affect their processes of acquisition and management of resources (Doherty et al. 2014; Battilana and Lee 2014; Tate and Bals 2018; Ladstaetter et al. 2018). These tensions derive directly from the management of a dual mission, i.e. in combining multiple organisational forms, social enterprises face clear discrepancies between social and financial goals (Austin et al. 2006). In fact, this pursuit of both types of goals requires that activities generate revenue streams while maintaining the creation of social value as a core objective (Mair and Marti 2006; Hockerts 2015; Servantie and Rispal 2018; Davies and Doherty 2018). Furthermore, their dual mission affects the extent to which social enterprises gain legitimacy from external stakeholders (resource-holders), ultimately affecting their environmental resource acquisition (Mair and Marti 2006; Desa and Basu 2013; McDermott et al. 2018; Ladstaetter et al. 2018; Lashitew et al. 2018). An example of this is evident in the domain of financial resources: Social value creation is usually perceived as being less attractive by financial institutions, such as banks and venture capital firms (Doherty et al. 2014).

The effect of resource constraints is also amplified in social enterprises because they usually operate in resource-scarce environments (Linna 2013; Doherty et al. 2014; Tate and Bals 2018; Janssen et al. 2018) in marginalised or developing countries, where social problems are massive (Zahra et al. 2008; Manning et al. 2017). In these environments, resources are simply not always available—or if they are available, their quality is generally low (Rivera-Santos et al. 2015; Zoogah et al. 2015; Mol et al. 2017) while their cost is high (Desa and Basu 2013).

However, Doherty et al. (2014) highlighted how the mix of social and financial goals and processes could also represent an opportunity to access resources. For instance, hiring people from disadvantaged communities entails a lack of skills but, at the same time, represents an opportunity to gain incentives and motivation from social orientation. Another interesting view on this is evoked by the definition of antagonistic resources, which are combinations of resources that make the commercialisation of a product or service more difficult a priori (Hockerts 2015; Alberti and Varon Garrido 2017). In these studies, the authors explained how social enterprises could turn antagonistic resources into strategic resources, thereby gaining a competitive advantage that other firms cannot possess. Such enterprises are ultimately able to leverage their processes of obtaining and managing resources in a complementary way. Thus, the hybrid nature of these organisations ultimately presents some unique opportunities from the resource acquisition and exploitation perspectives. As also reported by Lashitew et al. (2018), social enterprises tend to use peculiar approaches and creative resourcing processes, but their underlying mechanisms remain unclear (Doherty et al. 2014; Sonenshein 2014; Ladstaetter et al. 2018).

To study resource constraints, many theories have been proposed (Desa and Basu 2013; Rawhouser et al. 2017), but scholars have recently identified a more proper perspective via the lens of bricolage theory (Baker and Nelson 2005; Linna 2013; Bacq et al. 2015; Servantie and Rispal 2018). In fact, social enterprises usually overcome resource constraints by acquiring and managing resources on hand and innovatively combining them (Desa and Basu 2013; Ladstaetter et al. 2018). Bricolage theory has emerged as the leading approach to understanding the social entrepreneurial phenomenon (Di Domenico et al. 2010; Servantie and Rispal 2018; Lashitew et al. 2018) and has been described as a resource-enabler in the social entrepreneurship literature (Desa and Basu 2013; Ladstaetter et al. 2018).

Bricolage has been used to explain how enterprises in resource-poor environments recombine elements at hand for new purposes (making do with resources at hand), this reflects how bricoleurs refuse to be constrained by limitations and act via improvisation (Baker and Nelson 2005). These pillars highlight how bricolage is an action-oriented approach to solving problems by using resources in ways for which they were not originally designed, through creative reinvention (Fisher 2012; Linna 2013; Janssen et al. 2018; Lashitew et al. 2018), and by doing so, exploiting opportunities un-utilised by other firms (Baker and Nelson 2005; Ladstaetter et al. 2018).

Furthermore, Di Domenico et al. (2010) studied micro-processes of social entrepreneurship in which resources are identified, acquired and used, confirming the three original pillars of bricolage theory. Social bricolage theory explains how social enterprises, in making do, actually create social value (generating employment opportunities, work integration and skills development) and implement two other processes: stakeholder participation (involving stakeholders in governance and decision making) and the persuasion of other significant actors to leverage the acquisition of new resources and support (Di Domenico et al. 2010; Fisher 2012; Linna 2013). In fact, Di Domenico et al. (2010, p. 699) discovered how “using resources on-hand and recombining them for new purposes is fundamental to creating social value in a resource-poor environment and achieving financial sustainability”.

Social enterprises and resources have been considered from various perspectives, but several questions remain unanswered, and there is still the need for theory building research to better understand how social businesses can overcome resource constraints (Desa and Basu 2013; Doherty et al. 2014; Battilana and Lee 2014; Rawhouser et al. 2017). Other gaps have been noted in the literature, e.g. Di Domenico et al. (2010) identified the need to extend the repertoire of effective practices used by social enterprises in acquiring and building their resource portfolios. Moreover, scholars must refine social bricolage theory by exploring its implications for developing countries (Di Domenico et al. 2010). Finally, there have recently been calls to further investigate the practices of creative resourcing by social enterprises (Sonenshein 2014; Rawhouser et al. 2017; Ladstaetter et al. 2018; Lashitew et al. 2018). Our paper addresses these research gaps by demonstrating practices used to harvest resources in resource-scarce environments and how social enterprises leverage their hybrid nature to both find and harvest the resources they need.

Research Methodology

Introduction to the Methodology

Since there is little understanding of how hybrid organisations overcome their resource constraints, we adopted a grounded theory-based approach, as such a method is particularly valuable and well suited when research focuses on ‘why’ and ‘how’ questions in relatively new and undiscovered areas (Yin 1984; Suddaby 2006; Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007) as well as in uncertain international environments (Ghauri 2004).

To bring qualitative rigour to the research, we followed Gioia et al.’s (2013) methodology. This inductive approach entails multiple cycles of confrontation between data (interviews and secondary data) and theory, and it allows for the implementation of Glaser and Strauss’s (1967) suggestion to link, qualitatively and systematically, natural data with a formal approach. Each iteration added to the construction of concepts and to the relationship between resource constraints and the strategies used to overcome them. The result was a grounded model that included various intermediary steps (first-order codes, second-order themes, aggregate dimensions) from the raw case data and theory.

Empirical Setting

In the field of social enterprises, African countries are becoming increasingly interesting (Rivera-Santos et al. 2015; Littlewood and Holt 2015; Kolk and Rivera-Santos 2018; Mol et al. 2017). Africa is exceptionally diverse, home to more than 1000 ethnic groups (Nyambegera 2002; Zoogah et al. 2015; Michalopoulos and Papaioannou 2015), but African countries strongly share a social entrepreneurial orientation and therefore represent a fruitful venue for investigating the social entrepreneurship phenomenon (Zahra et al. 2008; Rivera-Santos et al. 2015; Zoogah et al. 2015). Among African countries, Kenya was an early adopter of hybrid business models (Holt and Littlewood 2015; Manning et al. 2017) due to its culture (strongly oriented to the local community) and the opportunities offered by economic growth (Nyambegera 2002; Zahra et al. 2008; Rivera-Santos et al. 2015). As a developing country, Kenya is growing at an average of 5 to 6% per year, and due to a “strengthening consumer base, expansion in electricity and agricultural production, as well as greater tourism activity, the prospects for continued growth appear to be bright” (British Council 2017, p. 13). Kenya is also home to a substantial number of social enterprises, around 44,000 according to the British Council (2017), one-half of which are female-led. In fact, there have been concerted efforts to empower women in different ways more broadly, efforts reflected in the social enterprise population. Finally, Kenya is a land characterised by a lack of financial, human, technological and supply network resources (Zahra et al. 2008; Zoogah et al. 2015; OECD 2017; Manning et al. 2017). For these reasons, Kenya represents a good setting for capturing the features of social enterprises (Littlewood and Holt 2015; Rivera-Santos et al. 2015). In our research, we proceeded with a purposive sample, meaning that additional incidents, activities and further interviews were directed by the evolving theoretical constructs. In fact, as some lines of evidence of resource constraints and related strategies began to emerge, we updated the interview protocol and pursued deeper information. Because some people in Africa are unwilling to share information, we started to focus on cases of social enterprises with a high commitment to sharing data and experiences. Then, we identified case studies in which organisations had been financially profitable for at least 2 years with the aim of understanding successful strategies for overcoming resource constraints. Some of the cases addressed the social needs of poor people in rural areas or slums, providing them with affordable products and services (e.g. sanitary pads and pants); other cases integrated disadvantaged workers, such as women with HIV, people with disabilities, street boys in slums or other marginalised groups. All our cases reinforced the definition of social enterprises, which aim to maximise social impact while being financially sustainable.

Following Gioia et al.’s (2013) methodology, our research was built in three main phases. In phase one, we familiarised ourselves with the Kenyan context through in-depth document analysis and field interviews. Then, in phase two, we proceeded with the data analysis and development of the grounded model, which was based on insiders’ interpretations from the interviews and other data (Corbin and Strauss 1990). Phase three involved the triangulation and substantiation of the emerging model, following suggestions by Glaser and Strauss (1967). An overview of the data sources is given in Table 1.

Data Collection

The data collection started in April 2017. In our desk research, we analysed reports from international and local institutions (e.g. World Bank). We contacted social enterprises by email and analysed their open data and online documents. We completed four initial interviews via conference call that served as a guide for narrowing the focus of our research and refining the interview protocol (Strauss and Corbin 1998), as was a “get in there and get your hands dirty” research (Gioia et al. 2013, p. 19). This approach enabled us to validate the information and develop a fuller understanding of the case studies, as well as to begin to sort out the main concepts and themes (Glaser and Strauss 1967). Preserving the flexibility of the protocol, in July and August, we collected other primary data in Kenya from semi-structured interviews. Table 2 reports the case study data.

We conducted a total of 18 semi-structured interviews and made follow-up conference calls, thereby increasing confidence in the reliability of the interpretations. The interviews lasted from 40 min to 1.5 h each were open-ended and followed a protocol that had evolved with the research project. They were carried out with top management team members (almost always CEOs) and were recorded and subsequently transcribed verbatim. Initially, we asked questions about business history, main events and facts; then, we asked which resource constraints the social enterprises had faced and/or were facing, and we inquired about what strategies were used to acquire scarce resources. After the initial interviews, we reviewed and updated the interview protocol following guidelines provided by Glaser and Strauss (1967). Protocol reviews were important for delving deeper into critical topics, such as specific constraints (e.g. unmotivated people or difficulties finding working capital) that were peripheral at the initial stage of research. Finally, during the interviews and headquarters visits, we gained more insight into the deployment of hybrid harvesting strategies, triangulating interviews with real-life contexts, documentation analysis and notes. The whole approach resulted in an iterative process of simultaneous data collection, data analysis and informant recruitment. This process continued until further data collection and analysis yielded no further explications of a given category or theme (Glaser and Strauss 1967; Locke 2001). This is what Glaser and Strauss (1967) referred to as theoretical saturation.

Data Analysis

In the data analysis process, we moved back and forth between the qualitative data and relevant theoretical arguments. Following Gioia et al.’s (2013) guidelines, we gradually developed our data structure based on three main steps.

Step 1: Creating Categories and First-Order Codes

We started labelling the resource shortages mentioned in the interviews, seeking to understand their underlying causes. At the same time, we focused on unconventional approaches, generating an understanding of how resource constraints were overcome. We also labelled these approaches.

Therefore, codes were derived inductively from the data and ranged in length from a few words to whole sentences. Additional data sources, such as business models, business plans, marketing plans, financial models and reports and articles, were used at this stage to validate the researchers’ interpretations.

Following the re-reading process for the interviews and other data, we gradually combined the original labels into the preliminary category of first-order codes. For instance, we coded the lack of ‘employee productivity,’ ‘customer engagement’, ‘knowledge of customer needs’, ‘raw material availability’ and ‘financing and working capital’. In parallel, we performed the same analytical process by tracking new knowledge about how each social enterprise overcame its resource constraints. We labelled these creative practices with first-order codes for what we successively defined as hybrid harvesting strategies. For instance, we discovered that one social enterprise had hired former prison detainees, and we coded this approach as ‘the employment of outcasts’.

Reliability throughout the data analysis was ensured by double coding procedures, meaning that two researchers independently coded the data before merging their analyses and searching for substantial agreement. Before merging the analyses, we controlled for intercoder reliability by following the procedure suggested by Miles and Huberman (1994). The reliability was 88% (number of agreements divided by the total number of agreements plus disagreements of the researchers), which is acceptable since the authors suggested that intercoder reliability of 70% or greater was desirable.

Step 2: Integrating First-Order Codes and Creating Second-Order Themes

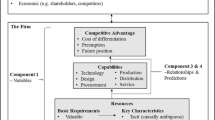

At this stage, we gathered the first-order concepts into categories that had already been identified in the literature. Using axial coding, we combined first-order codes into second-order themes, engaging in a systematic comparison of emerging constructs with existing concepts in the research to assess fit and adjust the labels accordingly (Gioia et al. 2013). Finally, we gathered second-order themes into two large aggregate dimensions: ‘resource constraints’ and ‘hybrid harvesting strategies’. Our data structure in Fig. 1 illustrates our first-order codes, second-order themes and aggregate dimensions.

Step 3: Building a Grounded Theoretical Framework

Once our second-order themes had been identified and grouped into the two aggregate dimensions, we examined the relationships and interrelations among these constructs. We attempted to understand which hybrid harvesting strategy was implemented to overcome one or more resource insufficiencies. We matched all the information into a matrix; the framework that emerged is presented in the next section.

Findings

Through our work, we identified seven main resource constraints experienced by social enterprises: customer loyalty, distribution networks, financial resources, human resources, information and market knowledge, raw materials, and technologies and reliable suppliers. At the same time, we discovered five strategies (that we further defined as hybrid harvesting strategies) that social enterprises can implement to overcome resource constraints, which we labelled as follows: social partnerships, social networking, local cluster development, customer empowerment and inclusive employment. Finally, we developed the grounded model presented in Fig. 2, which illustrates which hybrid harvesting strategy can be implemented to overcome specific resource constraints.

Next, we concentrated on each second-order theme, with a focus on our core contribution: the hybrid harvesting strategies. In the remainder of this section, we proceed with the narrative of our observations in order to comment on the theoretical model. We also provide selected quotations to support our interpretations (Table 3), following recent recommendations for qualitative research (Pratt 2009).

Resource Constraints

To explain each lack of resources, in this section we briefly present the first-order codes and second-order themes. The second-order themes were built on concepts previously discussed in the literature (Sirmon et al. 2007; Bowen et al. 2009; Zoogah et al. 2015; Rivera-Santos et al. 2015; Davies and Doherty 2018; Mirvis and Googins 2018).

From our analysis, the first identified resource constraint was related to customer loyalty. Many firms highlighted how trust and loyalty could be a key resource in an environment like that in Kenya as customers typically are informal and poor people that base their relationships on word of mouth and community ties (Atiase et al. 2018). This is consistent even with previous scholars’ results, as reported by Zoogah et al. (2015). For example, a car-care product company (Firm #6) highlighted that, in this informal environment, a company must address customer loyalty and create a customer-centric perspective:

People in Kenya want to have low prices and high quality. They want customised products and fast delivery. Everything perfect, but they don’t trust so easily. And if they don’t trust, they will not be loyal to your brand. (Firm #6)

The same line of evidence emerged from another firm that designed and produced high-quality fashion apparel and beaded accessories, integrating groups of women as workers:

Here in Kenya, one of the main problems is loyalty. People live based on trust and word of mouth. Eighty per cent of our customers are women, so when they access funds and training, their businesses grow. And if they trade more, they improve their livelihood; they can give better education to the children, save money […]. In the end, they will be loyal to us. If they need more, they know they can come to us. (Firm #11)

From our cases, it is possible to observe a lack of customer loyalty reflected by scarce customer satisfaction and low levels of customer retention, showing that in Kenya it is more difficult to generate retention and willingness to pay.

Next, our data showed a challenge related to the establishment of a distribution network. Kenya comprises a vast rural area and accessing the customer base is a struggle (Smith and Darko 2014; Rivera-Santos et al. 2015). Some enterprises also identified the creation of a network of direct sales representatives in the country as a challenge due to poor infrastructure and long distances, thereby supporting research by Sirmon et al. (2007). The case of Firm #13 (a company that produces and sells a solar home kit and provides micro-loans to customers) clearly highlights this challenge:

What we were missing was to scale our business regionally. We needed a sales agent’s network and shops where people could go, subscribe to our microfinance loan, and get the solar home kit. That was a challenge. Kenya is a land of different counties, different cultures, different tribes, and a huge rural area. (Firm #13)

The lack of a distribution network also means difficulties in foreign market penetration; for example, a certified organic tea and jam production company (Firm #5) was struggling to export products abroad, where it was difficult to establish a sales presence.

Financial resources represented a major challenge across the country (Bowen et al. 2009; Doherty et al. 2014; Zoogah et al. 2015; Atiase et al. 2018). This was immediately related to difficulties obtaining financing (from banks and/or other investors), as well as working capital (OECD 2017). The following comment represents this key problem for Firm #3, a waste management company that collects waste plastics from dump sites, then recycles and transforms them into building materials:

We didn’t have money! We required capital to purchase machinery and increase production. The demand was there: We needed to grow. […] By capital, I mean not only funding but also working capital to purchase waste plastics. (Firm #3)

Human resources represented another critical resource constraint, a finding consistent with the literature (Hitt et al. 2011; Doherty et al. 2014; Zoogah et al. 2015; Mirvis and Googins 2018). Through our analysis, we identified employees’ reliability, productivity and skills as three major challenges in this arena. For example, Firm #2 (a business service enterprise that provides affordable cleaning services to hotels, hospitals, public institutions, private households, etc.) explained how African employees are characterised by low levels of productivity and dissatisfaction. Moreover, Firm #7 (a construction company that builds social houses in Nairobi) confirmed that workers at building sites used to disappear whenever they wanted, no matter how high their salary was—a matter of productivity and loyalty to the firm. Firm #7 was also characterised by high employee turnaround, representing a challenge to financial sustainability. Another critical problem concerned highly skilled employees, as illustrated in the following quotation by Firm #4 (a solar panel manufacturing company targeting low-income households):

We needed to get more skills: We are engineers, and we had to find other skilled profiles, like finance, credit analysis, manufacturing, investor relations. It’s not easy here, where skilled people are so rare […]. (Firm #4)

One major finding was the difficulties African businesses face in obtaining information and knowledge, a finding also confirmed by the literature (Zoogah et al. 2015; Davies et al. 2018). Many social enterprises lack knowledge about customers’ needs. For instance, Firm #9 (a mobile health care information provider for rural communities) struggled to obtain knowledge about market conditions and demand: operating in many rural counties, the firm did not have access to information on relevant topics, such as the number of local hospitals, the number of patients, the number of births or the number of parents, with evident difficulties with financial planning and target quantification. Another issue was related to employees’ needs, as social enterprises face difficulties in understanding and defining the benefits and rewards to provide to the employees so that to increase their satisfaction and productivity. Rewarding mechanisms are sometimes very difficult to be leveraged. Thus, information and knowledge are critical resources in this usually unknown and unstructured market.

Kenya also presents challenges concerning the availability of raw materials and technologies (Linna 2013; Smith and Darko 2014; Drouillard 2017). In our findings, many social enterprises struggled to obtain the right raw materials in terms of quantity and quality. For instance, Firm #11 manufactures high-quality bags, which requires high-quality raw materials (leather, silk and canvas) and sometimes there are local suppliers on the markets, but the quality of the materials is very poor. At the same time, machinery and technologies were identified as rare and expensive, making them a strategic resource.

The final identified resource constraints concerned the suppliers’ reliability (Linna 2013; Davies and Doherty 2018). Usually, the organisations had low levels of manufacturing and managerial capabilities. Supplier productivity (e.g. on-time production and delivery, the right quantity delivered, etc.) is often deceptive. For instance, Firm #5 struggled to receive rare teas from farmers because they would deliver orders late, which was particularly challenging with respect to Italian market demand, which is based on on-time delivery. Consequently, the risk of losing many customers because of a deficient supply chain was high.

Above, we presented the results concerning several resource constraints. In the next section, we focus on the core topic of our work: hybrid harvesting strategies.

Hybrid Harvesting Strategies to Overcome Resource Constraints

From our research and analysis, we identified five unconventional approaches used by social enterprises in overcoming a lack of resources, which we collectively refer to as ‘hybrid harvesting strategies’. From our cases, we observed how the social enterprise behaved like a farmer with his/her hard to cultivate plantation. They refused to be constrained by difficulties collecting resources, leveraging their hybrid nature (the combination of social and financial missions) to sow seeds that, as time goes by, will ultimately bear fruit. We define Hybrid harvesting strategies as those mechanisms and processes that, taking advantage of their hybrid nature, allow a social enterprise to sow seeds in society that, over time, will give the enterprise the opportunity to harvest a resource and overcome constraints in resource acquisition.

In line with Di Domenico et al. (2010), we discovered that social enterprises leveraged their hybrid nature to access resources by using persuasion and the creation of social value. First, social enterprises leveraged their hybrid nature as a persuasive practice to stakeholders through social partnerships and social networking. Second, we observed three strategies by which social enterprises created social value and, at the same time, harvested valuable resources: local cluster development, customer empowerment and inclusive employment. Underlying these processes is the unconventional cultivation of a hybrid nature which is leveraged in order to sow and harvest resources that were originally scarce or unavailable.

We observed that hybrid harvesting strategies could be implemented independently or as a mix of different strategies. For instance, some cases approached employees, as evidenced by the ‘inclusive employment’ strategy, while simultaneously focusing on ‘customer empowerment’. We develop each strategy in detail below.

Social Partnerships

Social partnerships represent long-term strategic relationships with non-governmental organisations (NGOs), local associations, educational and research institutions, and informal groups. Social enterprises leverage the social mission, whereas social enterprises can align social goals with the mission of the partner. In this way, NGOs and non-profit organisations build strong partnerships with social enterprises to ultimately achieve their missions (Lashitew et al. 2018).

Social enterprises can develop better distribution networks and access to market information through social partnerships with local associations, informal groups or educational institutions. For instance, partnerships with local rural churches and local associations as women groups allowed Firm #8 (the pants and pads production company) to access customer information. In fact, women typically have an informal meeting in local associations and churches and Firm #8 partnered with these associations to understand the social need and distribute the washable sanitary pads reaching even Kenya’s rural areas. Another enterprise (Firm #5, the tea and jam production company) managed to penetrate the foreign market because of partnerships with fair-trade organisations. NGOs usually have roots throughout a country, especially in rural areas, which in turn allows social enterprises that partner with them to access information and market knowledge, as evidenced in the following quote by a social enterprise (Firm #1) that supplies high-quality seeds to small farmers in Kitale:

Partnership with the Pan-African Beans Research Alliance [a local research centre] allowed us to deal with two large corporations and start acting as a collector of beans from small local farmers. They have the market knowledge we were struggling to get, and without knowledge, you cannot even move. (Firm #1)

As previously documented, hybrid organisations face enormous constraints when it comes to accessing financial resources. Many NGOs around the world provide funding to enterprises that are eligible to apply to their programmes and obtain grants. Firm #1, benefiting from the social mission and implementing a hybrid harvesting strategy, established a partnership with the One Acre Fund (a Kenyan NGO). Other for-profit organisations were not eligible, but the firm was able to apply and obtained grant and support.

Social partnerships allow hybrid organisations to access free training services for employees, thereby improving the skills, loyalty and productivity of human resources. Some of the activities are improvised. Firm #3 (a social enterprise that turns waste plastics into building materials) demonstrated how, after hiring an outcast group (marginalised street boys near a dump site), the employees required training sessions to develop skills. The entrepreneurs refused to be constrained by this situation and discovered an NGO that offered training services by the mission. Immediately, the company asked the Norwegian Refugee Council to provide free technical training services to the boys because of the social mission of the hybrid organisation.

Another contribution from partnerships is related to lack of technologies. In fact, establishing partnerships with business incubators/accelerators that are socially oriented allows access to techniques, machinery and business skills. An example of this advantage is illustrated in the following, where Firm #9 (a mobile health care information provider) was struggling to acquire necessary technologies. At the same time, combining the resources of the hub, they could access networks:

Being incubated in an iHub [a Kenyan business incubator] was important to develop the device for giving us the right technology. They accelerate many social enterprises to impact the community! Otherwise, we couldn’t have […]. At the same time, through their network, we did a first market test. It was the first trial, and already a great step ahead! (Firm #9)

Social Networking

Social networking represents activities, such as social initiatives and events, attended by hybrid organisations to engage in informal and occasional relationships with external stakeholders. Social networking includes the establishment of informal relationships with academia, research centres, governments and non-governmental institutions. Similar to social partnerships, social networking allows the social enterprise to overcome specific resource constraints by leveraging its social mission, aligning it with the social goals of the external stakeholder. Because of its dual mission, the social enterprise can speak the same language as the stakeholder, and this makes the harvesting of some resources that for-profit organisations cannot reach much easier (Lashitew et al. 2018). Social networking allows the organisation to overcome insufficiencies in customer loyalty, distribution networks and information and market knowledge. Going deeper into the cases, the successful implementation of social initiatives enables social enterprises to gain customer loyalty. For instance, the main customer of Firm #2 (an affordable cleaning service company) is hospitals and public institutions. The company at a certain point started to network with them and, by improvisation, set the social goal of giving part of the net profit to local hospitals to make access to healthcare affordable to disadvantaged people. By recognising this social value creation, Firm #2 could increase customer loyalty, and the hospital’s patients would ask for its cleaning services. This was unpredictable, but after cultivating this relationship, the harvest was actually important.

Another example is as follows:

Going social allowed us to improve our financial performance. Beyond sales and the growing local demand, there is the awareness from our customer of the social need we address. Creating a social impact on the local community is the proof of this. The bigger the impact you demonstrate, the more loyal they are. We have a lot of customers coming through references and word of mouth: It becomes a network. (Firm #3)

Networking with academia, government and local associations allow social enterprises to access more structured business networks. For example, entrepreneurs from Firms #2 and #3 attended MBA programmes or entrepreneurship programmes with the aim of locating the university network, which is usually composed of different actors, such as investors, incubators and research centres. Accessing the university network and networking with the local government also increased opportunities to obtain information concerning the market need, market data and customer insights. This was something they needed to cultivate over time, but they have been able to harvest strategic resources through this strategy. Firm #13, a solar home kit and micro-loan provider, reported that networking with government is vital for understanding the policies, regulations and outlook of the energy industry, whereas other for-profit organisations engage the government only to gain higher financial returns: Firm #13 showed how the government had supported them with data and networking because of the social mission behind the venture.

Local Cluster Development

Local cluster development is the third hybrid harvesting strategy, which we define as practices that exploit the hidden potential of the local supply chain to acquiring reliable supplies. Social enterprises facing these constraints with suppliers leverage their hybrid identity to put into place activities that create social value.

By implementing a local cluster development strategy, a social enterprise can harvest resources related to both the customer and supplier sides from the ground up. The key term is ‘local’: creating a local supplier base and empowering suppliers’ skills and production capabilities allow hybrid organisations to access reliable suppliers and raw materials more easily. Trained suppliers will be loyal, and hybrid organisations will also benefit from improved quality and on-time delivery. An example is Firm #11 (a social enterprise that produces high-quality fashion apparel and beaded accessories), which offers training sessions and complementary services (e.g. table crunching or money-saving services) to its suppliers to increase organisational efficiency. By doing so, the firm harvested productivity, delivery conditions and order effectiveness (e.g. quality and quantity).

Hybrid organisations that attempt to develop a local cluster refuse to be constrained by resources limitation and cultivate their hybrid nature, creating social value and also discovering benefits in terms of access to distribution networks and customer loyalty. In fact, local purchases enlarge the customer base, because of community ties, developing loyalty and customer retention for a firm that acts locally and fulfils a social need. Firm #13 (a solar home kit manufacturing company) clearly illustrates this phenomenon, stating that although this approach was unclear at the beginning, acting locally by developing a cluster allowed it to harvest valuable resources:

The more you can do locally, the more you are helping yourself. You’re helping the community, yes, providing training and services to increase knowledge. For example, on sales capabilities. But in the end, you are trying to cultivate a customer base and reliable suppliers, based on trust and loyalty. […] We didn’t know that, but we discovered that the more you do locally, the more you can also influence local government, local cooperatives… distributors! It’s a matter of relationships! For this reason, we are purchasing all the raw materials from Naivasha, but at the beginning we did ad lib. As a sort of improvisation, because we couldn’t know the future resources we got from that approach. (Firm #13)

Customer Empowerment

Another hybrid harvesting strategy is customer empowerment. This strategy can be described as multiple strategic actions taken to improve the relationship between the hybrid organisation and customers, with the final goal of securing revenues from them. Empowering customers, however, requires the social enterprise to make economic efforts and take higher risks: the firm will achieve a strong long-term relationship with the customer only if the firm pursues a social mission, not just financial goals. Through this customer empowerment strategy, the social enterprise can leverage its hybrid nature to overcome the lack of customer loyalty and financial resources.

A useful strategy for obtaining customer loyalty is to offer training sessions or other complementary services to customers. For instance, Firm #3 helped customers open bank accounts when they were not able to do so independently. Another case, Firm #12 (a financial services company that provides loans to micro-enterprises in slums), highlighted how training sessions on money savings and cash management allowed its customers to pursue their businesses.

Our customers are micro-enterprises in slums like Kibera, South B […] Training and empowering our customers, also through direct visits to their businesses, increased their revenues. By increasing their businesses, they were borrowing more money from us, also establishing a strong, loyal business relationship. (Firm #12)

This example shows how, by cultivating activities of social value creation, allowed to get important crops, as a loyal relationship that at the beginning was struggling the company. Thereby, training and services for customers will also benefit the firm’s financial resources. The following quote reflects how Firm #10 (motorcycle taxi service) benefited in terms of an increase in revenues:

We offer training to Boda Boda, our customers, to increase their business driving and entrepreneurial skills, and increase the quality of the industry. That is part of our social mission! But doing so brought back to us a huge increase in revenues in the gear shop, taxi services, and so on. It’s a circle, a business model that feeds itself continuously. […] We were just cultivating our social value creation, our purpose, and you can imagine the benefits we got! (Firm #10)

Moreover, to increase customer loyalty, it is necessary to align the payment method with customer conditions and needs. For instance, Firm #13 (a solar home kit manufacturing company) used M-Pesa services, a local mobile payment method that it is used every day by 95% of Kenyans (Drouillard 2017), for its sales management.

The most relevant finding is that to overcome the lack of financial resources, some firms finance their customers. This practice is implemented only by social enterprises that leverage their dual mission, balancing social and financial goals. In fact, usually, customers do not have the money to pay for the products or services immediately. The hybrid organisation will not be constrained by the situation and will instead try to improvise by exploiting its hybrid nature: it could deliver the product or service to the customers and provide them with loans or solutions to create social value while also seeking to capture a monetary return in the future. Firm #1 (seed and bean production company) financed customers (small farmers), giving them the seeds for free because they did not have the working capital necessary to purchase them. The farmers agreed to grow the firm’s crops and give the final products (beans) back to it. With this approach, the social enterprise gained a strong customer relationship, with the possibility of collecting beans from small farmers, selling them to large corporations, and taking the margin from the sales. Firm #1’s financial resources increased due to this practice.

It is also necessary for hybrid organisations to create another source of revenues around relevant social needs. This approach aims to anchor the customer through the sale of a core product or service as well as the future sales of complementary products. An exhaustive example is that of Firm #5, which built accommodations for tourists coming to visit the social cooperatives and tea plantations. These accommodations not only represented another revenue stream, but they were also the first step towards customer loyalty and retention for this hybrid organisation, which has had a social impact on more than 250 farmers. This is another example of how social enterprises can leverage their social mission to overcome a lack of financial resources.

Inclusive Employment

The final hybrid harvesting strategy concerns the practices of inclusive employment. This unconventional approach is related to the employment and exploitation of outcasts and disadvantaged groups (e.g. marginalised people, youths from the street, or people with disabilities). In our study, we discovered that many social enterprises hire people from marginalised and/or poor circumstances, integrating them into the company as part of their social mission. This hybrid harvesting strategy has often been implemented in partnerships with NGOs. In fact, such social enterprises train marginalised people and offer them complementary services, usually for free. In this way, they overcome the lack of skilled and motivated people while also generating benefits in terms of employee satisfaction, loyalty and productivity. As part of its social mission, Firm #7 (a construction company) hired former detainees who could not find employment after leaving prison because of the ‘stigma’ of incarceration. Firm #7 hired them anyway, and they were trained by an international NGO (World Vision). As a result, they rediscovered their human and professional value, and they worked more proactively, thereby increasing the social enterprise’s efficiency (the entrepreneur highlighted how much employee turnaround had decreased, while employee productivity had increased). Firm #3, the waste management social enterprise, provided clear evidence of this hybrid harvesting strategy’s effectiveness:

Training and services to youths from the street brought back to us more loyalty and productivity. You need to accommodate youths! They need to feel part of the community, and this is a long process. […] We started to partner with NGOs to train them and reinforce their competencies, and we finally get outcomes, such as productivity, efficiency, skills. (Firm #3)

To conclude, inclusive employment is a strategy implemented by social enterprises to pursue their social mission while simultaneously harvesting valuable resources and capabilities that, in the beginning, were scarce or simply unavailable.

The theoretical model presented in Fig. 2 summarises the findings presented above. Overall, our cases suggest that although hybrid organisations face several resource constraints, they can explore and develop five creative strategies to overcome them. These strategies have been developed through the exploitation of the hybrid nature of social enterprises in a way that allows the company to harvest valuable resources. In the next section, we discuss the results and provide the conclusions to our research.

Discussion

The aim of our study was to investigate which strategies can be implemented by social enterprises to overcome specific resource constraints. From our analysis, we identified seven main resource constraints and five hybrid harvesting strategies which leverage the hybrid nature of social enterprises to overcome these constraints. In the discussion that follows, we detail how our research contributes to theory building on resource constraints faced by hybrid organisations and to social bricolage theory.

Contribution to Social Enterprises and Resource Constraints

Scholars have identified resource constraints as one of the key challenges for hybrid organisations (Linna 2013; Desa and Basu 2013; Doherty et al. 2014; Servantie and Rispal 2018; Lashitew et al. 2018). These organisations continuously face tensions in resource acquisition due to their dual mission and to the resource-scarce environments in which they usually operate (Dacin et al. 2010; Battilana and Lee 2014; Janssen et al. 2018).

With our results, we support earlier research by providing a clear overview of which resource constraints affect social enterprises (Battilana and Lee 2014). Following Rivera-Santos et al. (2015) and Tate and Bals (2018), we documented how social enterprises face constraints in terms of customer loyalty, which is a relevant resource in developing contexts (Hitt et al. 2011). The flow of funds and revenues is particularly challenging when businesses are trying to address multiple goals (Santos et al. 2015; Tate and Bals 2018; Atiase et al. 2018). Some social enterprises also revealed that the creation of a distribution network is a challenge, a finding supported by Sirmon et al. (2007), as well as the acquisition of market knowledge, especially in developing countries where data from rural areas are not available or unclear (Hitt et al. 2011). Finally, skilled people, raw materials and technologies are leading constraints for social enterprises, as resources are simply not always available, or their quality is low (Rivera-Santos et al. 2015; Zoogah et al. 2015) while the cost to acquire them is high (Zahra et al. 2008; Desa and Basu 2013).

In addition, scholars have recently highlighted how the dual mission in social enterprises could represent a source of hidden opportunities to acquire external resources, yet this phenomenon remains unclear (Linna 2013; Doherty et al. 2014; Rawhouser et al. 2017; Lashitew et al. 2018). With our study, we contribute to research on social entrepreneurship and answer the call to increase knowledge about how social enterprises can deal with resources constraints by implementing creative strategies (Ladstaetter et al. 2018). In fact, scholars have suggested that social enterprises can leverage their hybrid nature to overcome barriers (Davies et al. 2018) by pursuing creative resourcing (Sonenshein 2014; Ladstaetter et al. 2018; Lashitew et al. 2018). We took a step ahead by highlighting how social enterprises are exploiting their hybrid nature to harvest resources. We identified five hybrid harvesting strategies, each of which allows social enterprises to creatively exploit their hybrid nature to overcome specific resource constraints. Our main contribution is a clear explanation of the mechanisms behind these strategies and the relationship of each strategy with resource constraints. For each resource constraint, we described the corresponding hybrid harvesting strategy, a valuable correlation that emphasises how the dual mission can be a trigger to harvest resources in resource-scarce environments. Social partnerships and social networking activities are not new concepts in the literature, as we found important evidence in Doherty et al. (2014), Lashitew et al. (2018) and McDermott et al. (2018). Especially in developing countries, networking and partnering with relevant stakeholders can help the company access valuable resources, not just enable social innovation (Lashitew et al. 2018). For instance, we highlighted how social enterprises hire people from disadvantaged groups, integrating and developing them (inclusive employment). Through free training sessions offered by partnerships with NGOs and additional services provided by other social partners (social partnerships), social enterprises have been able to harvest skilled resources, stimulating motivation, loyalty and productivity. Our hybrid harvesting strategies support previous literature on how a hybrid nature can represent an opportunity, and we documented the importance of leveraging this nature via a cultivation process (through our strategies) that ultimately allows the harvesting of resources.

Moreover, in our findings, some social enterprises provided training and services to suppliers, such as bank accounts or health insurance (local cluster development): developing the local supply chain will definitely bring to reliable suppliers or access easily to good-quality raw materials. These are clear examples of how the dual mission of the hybrid nature can be leveraged by implementing hybrid harvesting strategies: a finding unprecedented in the literature. Our strategies allow social enterprises to harvest resources that are normally hidden, unavailable or expensive. Building this construct can increase knowledge about the mechanisms of resource acquisition and exploitation, which according to Ladstaetter et al. (2018), are unexplored areas.

Contribution to Social Bricolage Theory

To study the relationship between social enterprises and resource constraints, previous scholars have used bricolage and social bricolage perspectives (Di Domenico et al. 2010; Desa and Basu 2013; Bacq et al. 2015; Janssen et al. 2018). Our results contribute to the social bricolage literature by describing how social bricoleurs can overcome existing resource constraints and access resources before combining them. Our cases in developing countries confirm that social enterprises refuse to be constrained by limitations and instead seek to manage resources on hand (Baker and Nelson 2005; Janssen et al. 2018; Servantie and Rispal 2018), but more important they try to show something in the society that finally lead to a harvest of resources that were scarce or unavailable. Underlying the process, there is the leverage of the social mission, to implement hybrid harvesting strategies. Furthermore, social enterprises revealed an improvisation process, or some hidden opportunities captured along the way. Starting from this, social bricolage theory adds three bricolage processes: the creation of social value, stakeholder participation and persuasion. Following the call for further research by Di Domenico et al. (2010), we enrich social bricolage theory by providing evidence about how the creation of social value could be leveraged to overcome resource constraints. We presented local cluster development, customer empowerment and inclusive employment as three main strategies to leverage the social mission, and through a social bricolage approach, to ultimately obtain valuable resources. We provided evidence about how social enterprises generate employment opportunities for outcasts and marginalised groups and then integrate them through training and services (‘inclusive employment’). Moreover, social enterprises develop skills and offer training sessions to customers and suppliers as well, trying to assist them (‘customer empowerment’) and thereby exploiting the local supply chain (‘local cluster development’). Although these three hybrid harvesting strategies represent the creation of social value, they also allow the harvesting of resources by leveraging the hybrid nature.

Furthermore, we contribute to social bricolage theory by adding knowledge about persuasion practices and access to resources. Social partnerships and social networking are leading persuasion hybrid harvesting strategies which are based on the alignment of the social mission with the objectives of the partner/actor engaged in networking. By interacting with partners and external actors, a social enterprise demonstrates its ability to create social value and, (Doherty et al. 2014; Davies et al. 2018; Lashitew et al. 2018), leveraging the social mission, it can be supported by an external actor with access to needed resources. Towards social partnership, the social enterprise can establish long-term relationships that open the opportunity to combine resources owned by the enterprise with those owned by partners. In addition, by increasing the awareness of the created social value, social enterprises could develop a relationship with stakeholders and increase the knowledge of opportunities in the market and the access to specific stakeholder’s resources.

Finally, we did not find any reference to ‘stakeholder participation’ (one of the social bricolage theory pillars), as our cases did not involve stakeholders in governance mechanisms; however, our hybrid harvesting strategies can represent an initial form of integrating stakeholders in governance decisions when social enterprises discover the hidden potential of the hybrid nature and start to harvest resources. At that time, it will be suitable to include stakeholders and seek to harvest more required resources.

Contribution to Practitioners

Our study presents relevant insights for managers and entrepreneurs of social enterprises in resource-scarce environments. We provided more evidence about how to acquire and exploit strategic resources through hybrid harvesting strategies. This construct improves entrepreneurs’ and managers’ understandings of how to manage a social enterprise facing resource constraints. Our model offers a clear, simple tool to exploit the hybrid potential of a social enterprise and implement practices to overcome resource constraints. Entrepreneurs and managers can deploy the hybrid harvesting strategies alone or in combination.

Moreover, we also generated some insights into the entrepreneurial approaches of African businesses, elucidating the dynamics of social enterprises in this unexplored environment (Littlewood and Holt 2015; Kolk and Rivera-Santos 2018; Lashitew et al. 2018).

Conclusions: Limitations and Future Research

The path towards achieving a sustained competitive advantage for hybrid organisations is still under exploration, but we have contributed to this field by increasing understanding of how to cope with resource constraints while exploiting the potential of the hybrid nature. We have demonstrated that challenges in the form of resource constraints can be turned into opportunities via hybrid harvesting strategies.

However, there is a clear need for further theoretical work on the hybrid harvesting strategies constructs. Future studies could focus on which hybrid harvesting strategies are more effective in addressing the same resource constraints (e.g. lack of customer loyalty can be overcome by social networking, local cluster development and customer empowerment). Moreover, another interesting approach would be to elucidate the relationships among these hybrid harvesting strategies. For instance, the following questions could be addressed: What are the key combinations of strategies? Should they be implemented sequentially? Following from this, we could ask: Are there other hidden combinations strategies yet to be discovered?

Scholars can further investigate the implementation process of these strategies or extend them to other research settings. Specifically, we suggest research in countries other than Kenya, such as the United States or the United Kingdom, where social enterprises present other peculiarities that can yield knowledge on other resource constraints and the creative approaches taken to acquire them via the leveraging of the hybrid nature.

Furthermore, we extended the topics of ‘persuasion’ and ‘creation of social value’ proposed by Di Domenico et al. (2010). However, as we did not find in our data analysis any reference to stakeholder participation, further studies could explore this topic by determining whether, after hybrid harvesting, social enterprises integrate and involve stakeholders in governance structures and decision making, as was suggested by Tate and Bals (2018).

Our study had some limitations that also offer future research opportunities. First, because our research methodology was exploratory, our conclusions can only be viewed as tentative and should be better explored and validated. The matrix we developed represents relationships arising from the interception of raw data and theory, which can drive future research and analysis of the phenomenon. Our intention was to provide preliminary evidence about which hybrid harvesting strategy can be implemented to address certain types of resource constraints. However, other resource constraints and approaches could be identified and explained, providing fertile ground for future research.

A second limitation concerns the sample. The authors recognise that the small sample size could be enlarged, possibly with quantitative analysis, to better explore and validate our model. Moreover, the focus of the study (Kenya) entailed limitations because it is a country characterised by several resource insufficiencies, along with many other problems—institutional voids, corruption and poverty, to name a few. These problems should be considered in future studies. Other context specificities, including gender diversity and ethnic and cultural differences, can also affect hybrid harvesting, as developing countries strongly rely on community ties (Zoogah et al. 2015).

With our study, we hope to lay the basis for stimulating further theoretical and empirical research on the growing topic of resource constraints in hybrid organisations, showing that hybridity can offer creative ways to harvest resources. Opportunities are sometimes just around the corner, waiting to be discovered and exploited.

References

Alberti, F. G., & Varon Garrido, M. A. (2017). Can profit and sustainability goals co-exist? New business models for hybrid firms. Journal of Business Strategy, 38(1), 3–13.

Atiase, V. Y., Mahmood, S., Wang, Y., & Botchie, D. (2018). Developing entrepreneurship in Africa: Investigating critical resource challenges. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 25(4), 644–666.

Austin, J., Stevenson, H., & Wei-Skillern, J. (2006). Social and commercial entrepreneurship: Same, different, or both? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30, 1–22.

Bacq, S., & Janssen, F. (2011). The multiple faces of social entrepreneurship: A review of definitional issues based on geographical and thematic criteria. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 23(5–6), 373–403.

Bacq, S., Ofstein, L. F., Kickul, J. R., & Gundry, L. K. (2015). Bricolage in social entrepreneurship: How creative resource mobilization fosters greater social impact. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 16(4), 283–289.

Baker, T., & Nelson, R. E. (2005). Creating something from nothing: Resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(3), 329–366.

Battilana, J., & Dorado, S. (2010). Building sustainable hybrid organizations: The case of commercial microfinance organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6), 1419–1440.

Battilana, J., & Lee, M. (2014). Advancing research on hybrid organizing—Insights from the study of social enterprises. Academy of Management Annals, 8(1), 397–441.

Bowen, M., Morara, M., & Mureithi, M. (2009). Management of business challenges among small and micro enterprises in Nairobi-Kenya. KCA Journal of Business Management, 2(1), 16–31.

British Council. (2017). The state of social enterprise in Kenya. Retrieved from https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/state_of_social_enterprise_in_kenya_british_council_final.pdf. Accessed 22 Jan 2018.

Corbin, J. M., & Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: Procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Sociology, 13(1), 3–21.

Costanzo, L. A., Vurro, C., Foster, D., Servato, F., & Perrini, F. (2014). Dual-mission management in social entrepreneurship: Qualitative evidence from social firms in the United Kingdom. Journal of Small Business Management, 52(4), 655–677.

Dacin, P. A., Dacin, M. T., & Matear, M. (2010). Social entrepreneurship: Why we don’t need a new theory and how we move forward from here. Academy of Management Perspectives, 24(3), 37–57.

Davies, I. A., & Doherty, B. (2018). Balancing a hybrid business model: The search for equilibrium at Cafédirect. Journal of Business Ethics, 157, 1043.

Davies, I. A., Chambers, L., & Haugh, H. (2018). Barriers to social enterprise growth. Journal of Small Business Management. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12429.

Desa, G., & Basu, S. (2013). Optimization or bricolage? Overcoming resource constraints in global social entrepreneurship. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 7(1), 26–49.

Di Domenico, M., Haugh, H., & Tracey, P. (2010). Social bricolage: Theorizing social value creation in social enterprises. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(4), 681–703.

Doherty, B., Haugh, H., & Lyon, F. (2014). Social enterprises as hybrid organizations: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews, 16(4), 417–436.

Drouillard, M. (2017). Addressing voids: How digital start-ups in Kenya create market infrastructure. In B. Ndemo & T. Weiss (Eds.), Digital Kenya (pp. 97–131). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ebrahim, A., Battilana, J., & Mair, J. (2014). The governance of social enterprises: Mission drift and accountability challenges in hybrid organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 34, 81–100.

Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32.

Fisher, G. (2012). Effectuation, causation, and bricolage: A behavioral comparison of emerging theories in entrepreneurship research. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(5), 1019–1051.

Ghauri, P. (2004). Designing and conducting case studies in international business research. In R. Marschan-Piekkari & C. Welch (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research methods for international business (pp. 109–124). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative theory. New Brunswick: Aldine Transaction.

Haigh, N., Walker, J., Bacq, S., & Kickul, J. (2015). Hybrid organizations: Origins, strategies, impacts, and implications. California Management Review, 57(3), 5–12.

Haveman, H. A., & Rao, H. (2006). Hybrid forms and the evolution of thrifts. American Behavioral Scientist, 49(7), 974–986.

Hitt, M. A., Ireland, R. D., Sirmon, D. G., & Trahms, C. A. (2011). Strategic entrepreneurship: Creating value for individuals, organizations, and society. Academy of Management Perspectives, 25(2), 57–75.

Hockerts, K. (2015). How hybrid organizations turn antagonistic assets into complementarities. California Management Review, 57(3), 83–106.

Holt, D., & Littlewood, D. (2015). Identifying, mapping, and monitoring the impact of hybrid firms. California Management Review, 57(3), 107–125.

Janssen, F., Fayolle, A., & Wuilaume, A. (2018). Researching bricolage in social entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 30(3–4), 450–470.

Jay, J. (2013). Navigating paradox as a mechanism of change and innovation in hybrid organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 56(1), 137–159.

Kolk, A., & Rivera-Santos, M. (2018). The state of research on Africa in business and management: Insights from a systematic review of key international journals. Business & Society, 57(3), 415–436.

Ladstaetter, F., Plank, A., & Hemetsberger, A. (2018). The merits and limits of making do: Bricolage and breakdowns in a social enterprise. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 30(3–4), 283–309.

Lashitew, A. A., Bals, L., & van Tulder, R. (2018). Inclusive business at the base of the pyramid: The role of embeddedness for enabling social innovations. Journal of Business Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3995-y.

Linna, P. (2013). Bricolage as a means of innovating in a resource-scarce environment: A study of innovator-entrepreneurs at the BOP. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 18(3), 1350015.

Littlewood, D., & Holt, D. (2015). Social and environmental enterprises in Africa: Context, convergence and characteristics. In V. Bitzer, R. Hamann, M. Hall, & E. W. Griffin-EL (Eds.), The business of social and environmental innovation (pp. 27–47). Cham: Springer.

Locke, K. (2001). Grounded theory in management research. London: SAGE.

Mair, J., & Marti, I. (2006). Social entrepreneurship research: A source of explanation, prediction, and delight. Journal of world business, 41(1), 36–44.

Manning, S., Kannothra, C. G., & Wissman-Weber, N. K. (2017). The strategic potential of community-based hybrid models: The case of global business services in Africa. Global Strategy Journal, 7(1), 125–149.

McDermott, K., Kurucz, E. C., & Colbert, B. A. (2018). Social entrepreneurial opportunity and active stakeholder participation: Resource mobilization in enterprising conveners of cross-sector social partnerships. Journal of Cleaner Production, 183, 121–131.

Michalopoulos, S., & Papaioannou, E. (2015). On the ethnic origins of African development: Chiefs and precolonial political centralization. Academy of Management Perspectives, 29(1), 32–71.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mirvis, P., & Googins, B. (2018). Engaging employees as social innovators. California Management Review, 60, 25–50.

Mol, M. J., Stadler, C., & Ariño, A. (2017). Africa: The new frontier for global strategy scholars. Global Strategy Journal, 7(1), 3–9.

Nyambegera, S. M. (2002). Ethnicity and human resource management practice in sub-Saharan Africa: The relevance of the managing diversity discourse. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 13(7), 1077–1090.

OECD/EU. 2017. Boosting social enterprise development: Good practice compendium. Paris: OECD Publishing. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/publications/boosting-social-enterprise-development-9789264268500-en.htm.

Pratt, M. G. (2009). From the editors: For the lack of a boilerplate: Tips on writing up (and reviewing) qualitative research. Academy of Management Journal, 52(5), 856.

Rawhouser, H., Villanueva, J., & Newbert, S. L. (2017). Strategies and tools for entrepreneurial resource access: A cross-disciplinary review and typology. International Journal of Management Reviews, 19(4), 473–491.

Rivera-Santos, M., Holt, D., Littlewood, D., & Kolk, A. (2015). Social entrepreneurship in sub-Saharan Africa. Academy of Management Perspectives, 29(1), 72–91.

Santos, F., Pache, A. C., & Birkholz, C. (2015). Making hybrids work: Aligning business models and organizational design for social enterprises. California Management Review, 57(3), 36–58.

Servantie, V., & Rispal, M. H. (2018). Bricolage, effectuation, and causation shifts over time in the context of social entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 30(3–4), 310–335.

Sirmon, D. G., Hitt, M. A., & Ireland, R. D. (2007). Managing firm resources in dynamic environments to create value: Looking inside the black box. Academy of Management Review, 32(1), 273–292.

Smith, W., & Darko, E. (2014). Social enterprise: constraints and opportunities—Evidence from Vietnam and Kenya. ODI. Retrieved from www.odi.org/publications/8303-social-enterprise-constraintsopportunities-evidence-vietnam-kenya.

Sonenshein, S. (2014). How organizations foster the creative use of resources. Academy of Management Journal, 57(3), 814–848.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Suddaby, R. (2006). From the editors: What grounded theory is not. Academy of Management Journal, 49(4), 633–642.

Tate, W. L., & Bals, L. (2018). Achieving shared triple bottom line (TBL) value creation: Toward a social resource-based view (SRBV) of the firm. Journal of Business Ethics, 152(3), 803–826.

Yin, R. K. (1984). Case study research: Design and methods. Beverly Hills, CA: SAGE.

Yunus, M., Moingeon, B., & Lehmann-Ortega, L. (2010). Building social business models: Lessons from the Grameen experience. Long Range Planning, 43(2–3), 308–325.

Zahra, S. A., Rawhouser, H. N., Bhawe, N., Neubaum, D. O., & Hayton, J. C. (2008). Globalization of social entrepreneurship opportunities. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 2(2), 117–131.

Zoogah, D. B., Peng, M. W., & Woldu, H. (2015). Institutions, resources, and organizational effectiveness in Africa. Academy of Management Perspectives, 29(1), 7–31.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ciambotti, G., Pedrini, M. Hybrid Harvesting Strategies to Overcome Resource Constraints: Evidence from Social Enterprises in Kenya. J Bus Ethics 168, 631–650 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04256-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04256-y