Abstract

Inclusive businesses that combine profit making with social impact are claimed to hold the potential for poverty alleviation while also creating new entrepreneurial and innovation opportunities. Current research, however, offers little insight on the processes through which for-profit business organizations introduce social innovations that can profitably create social impact. To understand how social innovations emerge and become sustained in business organizations, we studied a telecom firm in Kenya that successfully extended financial services across the country through a number of mobile banking innovations. Our qualitative analysis revealed the strong role of being embedded in local networks and structures for initiating and implementing social innovations. Strong embeddedness enhanced the pragmatic and ethical imperative for internalizing social issues, but also provided access to diverse resources for implementing and legitimizing social innovations. However, hybridization processes that emphasized social issues introduced organizational tensions by increasing goal diversity and requiring adapting organizational processes and structures. The case shows how developing a mission-driven identity enabled the sustenance of social innovations by providing a meta-narrative that bridged goal diversities and rationalized organizational change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Business scholars and practitioners are increasingly exploring the potential of business to create value for shareholders in a manner that also addresses social issues (Porter and Kramer 2011; Wilburn and Wilburn 2014). In Base of the Pyramid (BoP—i.e. developing) economies, the strong interlinkage between social and environmental systems on the one hand and organizational performance on the other, forces organizations to adopt broader perspectives of value creation (George et al. 2016; Sulkowski et al. 2017). Further, businesses perceive an opportunity to regain their legitimacy by addressing major contemporary societal problems such as rising inequalities and climate change, which are often considered to be driven by ‘unfettered capitalism’ (Hart 2005; Wilburn and Wilburn 2014; George et al. 2016).

Consequently, there are calls for advancing our knowledge on ‘inclusive business’ approaches that create ‘shared value’ (Porter and Kramer 2011), by simultaneously pursuing social and environmental bottom-lines along with commercial profit (Elkington 1997; Dembek et al. 2016; Tate and Bals 2016). Studies have explored how businesses can contribute to poverty alleviation in the BoP by introducing ‘social innovations’—commercially viable innovations that address the pressing needs of low-income customersFootnote 1 (Prahalad 2004; Van Tulder et al. 2014; Kolk et al. 2014). Likewise, the literature on sustainable business models analyses the organizational and institutional mechanisms that enable businesses to effectively integrate sustainability practices with their core business models (Sulkowski et al. 2017; Gao and Bansal 2013; Hahn et al. 2015).

Research on hybrid organizations and social enterprises suggests that businesses that combine profit making with social and/or environmental goals are encumbered by organizational tensions that limit their performance and even threaten their survival (Fosfuri et al. 2016; Battilana and Lee 2014; Ramus and Vacarro 2017; Battilana and Dorado 2010). Real or perceived goal incompatibilities could lead to internal frictions among adherents of different goals, while accountability to a large number of stakeholders could induce governance and legitimacy challenges (Ebrahim et al. 2014; Battilana and Lee 2014). For mainstream business organizations, repositioning towards inclusive business approaches involves significant challenges since it includes reframing the organization’s goal and mission as well as adapting its capabilities and internal processes (Haigh and Hoffman 2012). Given the complexity and riskiness of the required changes, strategic shifts can only happen when the incentives become sufficiently large to outweigh the associated risks (Ramus and Vacarro 2017; Battilana and Dorado 2010). Attesting to these insurmountable institutional and organizational barriers, there are currently very few businesses that have successfully integrated inclusive business approaches into their core activities (Kolk et al. 2014; Slawinski et al. 2017; Werhane et al. 2010). The questions of how organizations can break away from the established dominant economic logic of profit making (Montabon et al. 2016), and adopt mission-based or inclusive business models, is hence an important but barely explored research topic (Halme et al. 2012). The goal of this study is to enhance current understanding of the mechanisms that enable commercial businesses to adopt inclusive (mission-driven) business approaches by integrating social causes into their core operations. This requires clearer articulation of the internal change processes, and the way these change processes relate to the socioeconomic context of the firm.

Extant research recognizes that embeddedness in social networks can enhance general business success, especially in developing and emerging economies where informal networks complement under-developed formal institutions (Granovetter 1985; Uzzi 1996; Mair et al. 2012). The emerging ‘Social Resource Based View’ (SRBV) of the firm emphasizes the significance of embeddedness, or the structural and relational qualities of the organization’s social ties, for implementing inclusive business approaches (Tate and Bals 2016; Valente 2012; Simanis and Hart 2009). However, there is scant evidence on how organizations can successfully build and leverage social ties to implement inclusive business approaches (Maak 2007). Consequently, our study will address the following research question: How does embeddedness contribute to the emergence and development of mission-driven or inclusive business approaches? Within this question lies the deeper managerial question of what ignites organizational change, and how the (social) context can mediate the process of change.

The analysis is based on an in-depth investigation of a telecom firm in Kenya that has launched mobile money innovations that have enabled tens of millions of users to get access to financial services. By carefully analysing qualitative data from diverse sources, we seek to glean analytically generalizable results with broader theoretical relevance (Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007). Our goal, therefore, is elaborating theory to generate a more nuanced understanding of how embeddedness enables organizational change towards inclusive business approaches and how it can help successfully address the tensions that result from hybridization.

The results of this study offer three new contributions to the current literature on inclusive and sustainable business models. Firstly, the results provide insights on the question of why organizations could have incentives for changing towards inclusive business approaches. Our analysis shows that embeddedness creates impetus for internalizing social externalities by enhancing the ethical and pragmatic significance of social innovations. Secondly, the results shed light on the enabling role of embeddedness for implementing and legitimizing novel social innovations. These results point to the unique features of social innovations that require diverse resources through collaborative endeavors but also substantial legitimization efforts.

Finally, our research shows how organizations navigate the challenges of hybridization related to goal diversity and the incongruence between existing processes and structures, and emerging practices. To mediate the process of organizational change, managers actively developed a mission-driven organizational identity that formally institutionalized inclusiveness throughout the organizations. We show how such an identity enabled successful hybridization by providing a discursive means for legitimizing organizational changes that were required aligning organizational processes and goals. Compared to previous research that tended to treat inclusive business approaches as outcomes of deliberate managerial responses (e.g. Battilana and Dorado 2010), the paper presents more nuanced understanding that highlights the interaction between managerial action and contextual factors. The results point to the importance of conceptualizing the firm as an embedded social agent that is reciprocally affected by its societal engagements to understand its impact on society and vice versa.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The following section lays out a conceptual background by reviewing the diverse research streams on inclusive business models and embeddedness. Subsequently, we introduce the case study by describing our process of data collection and analysis. The subsequent results section presents our findings on the emergence and implementation of social innovations and the development of a mission-driven organizational identity. The “Discussion” section provides our model for organizational change and lays out the paper’s contributions to the literature and its managerial implications. The conclusion section wraps up the paper by summarizing its main messages and suggesting future research directions.

Conceptual Background

The Challenges of Shifting to Inclusive Business Models

At least four challenges limit the ability of commercial businesses to integrate social and environmental issues into their core business models: (1) lack of motivation for change; (2) the need for new capabilities; (3) goal and identity conflict and (4) the difficulty to acquire legitimacy.

Motivation for Change Towards Inclusive and Hybrid Business Approaches

Social issues can offer a significant market potential, especially in BoP economies, but tapping into them requires novel business models that align social causes with commercial profit (Werhane et al. 2010; Prahalad et al. 2004). In spite of increasing interest on inclusive and sustainable business models, the contribution of business towards addressing social and sustainability issues remains at best marginal (Slawinski et al. 2017). This partly steams from the fact that standard managerial practices tend to be short-term oriented, which is reinforced by institutional structures that advance immediate shareholder returns (Slawinski et al. 2017; Halme et al. 2012). Even when the social cost of current business practices is recognized, inertia and uncertainty avoidance at managerial, organizational and institutional levels constrain change (Halme et al. 2012). Breaking away from the established dominant logic that prioritizes short-term value creation for a narrow domain of stakeholders requires both internal drive through transformational and responsible leadership as well as favourable external conditions (Maak 2007; Tideman et al. 2013). Previous research on motives for changing towards sustainable business models thereby documented the relevance of both intrinsic and extrinsic motives. Desired change is more likely when it can help businesses improve their (future) financial performance, gain legitimacy and acquire strategic resources (Brønn and Vidaver-Cohen 2009; Muller and Kolk 2010).

Reactive organizational responses remain predominant, with most businesses relying on separate CSR divisions or foundations to address social and environmental issues. ‘Decoupling’ social issues thereby allows organizations to make partial commitment for public concern without having to integrate them with their core commercial operations (Besharov and Smith 2014; Battilana and Lee 2014). However, there is now growing appreciation for integrative approaches that combine multiple bottom-lines as goal functions of corporations (Hahn et al. 2015; Gao and Bansal 2013). With the ascendance of social entrepreneurship, impact investing and inclusive business models, corporations are increasingly viewing social and environmental issues as potential sources for new forms of innovation and entrepreneurial opportunities (Halme et al. 2012). Especially in developing and emerging economies, firms adopt proactive strategies since social and environmental issues are strongly related to firm performance (Sulkowski et al. 2017).

The Need for New Capabilities

The juxtaposition of social and sustainability concerns with commercial bottom-lines in inclusive and sustainable businesses increases organizational complexity. The unique challenge of designing and executing inclusive business approaches thus requires configuring a new set of distinct capabilities (Seelos and Mair 2007; Porter and Kramer 2011). Goal complexity in value creation for a wider set of stakeholders demands greater organizational flexibility within, and strong relationships with outside actors to coordinate action to achieve systemic change. The literature on inclusive and sustainable business models identifies three sets of relevant capabilities: (a) organizational ambidexterity; (b) partnerships and co-creation and (c) native capabilities and bricolage.

-

(a)

Organizational ambidexterity is the ability to combine business processes underpinned by different end goals, logics and time horizons (Raisch and Birkinshaw 2008; O’Reilly and Tushman 2013). The concept is highly relevant for understanding processes of creating shared value, which constitute significant elements of organizational learning, adaptation and change (Battilana and Lee 2014). Inclusive businesses, for example, face the delicate challenge of balancing between commercial ventures that have a clear business case and relatively short time horizons, and potentially risky ventures that are oriented towards addressing complex social and environmental issues (Slawinski and Bansal 2015). Inclusive businesses could face trade-offs among competing goals with various time horizons, divergent values and courses of action and conflicting stakeholder interests (Van der Byl and Slawinski 2015; Hahn et al. 2015). Ambidextrous organizations that are able to create balance between divergent and complex business approaches, therefore, will have better chance of creating successful inclusive business models (Maak 2007; Slawinski and Bansal 2012).

-

(b)

Partnerships and co-creation Creating and implementing successful social innovations requires novel ideas, diverse resources and unique capabilities, which calls for collaborative business approaches (Austin and Seitanidi 2012) that integrate the firm’s capabilities with that of the ecosystem to create new entrepreneurial and innovation opportunities (Calton et al. 2013; Rivera-Santos et al. 2012; Sanchez and Ricart 2010). For multinational corporations, co-creation with local actors offers synergetic inputs such as local knowledge, contacts, legitimacy and brokerage services (Hahn and Gold 2014; Webb et al. 2010). Moreover, collaborative approaches have the advantage of mobilizing a broad spectrum of resources and coordinating action among diverse actors to achieve systemic social impact (Le Ber and Branzei 2010). Co-creation thus represents an intensive form of collaboration that leverages ideas and resources from internal and external sources to devise business solutions that address social and environmental issues (Calton et al. 2013; Nahi 2016). Research shows that co-creating value in collaboration with civil society, government and business partners can improve business responsiveness to customer needs, reflecting the market conditions and institutional demands of BoP contexts (Calton et al. 2013; Rivera-Santos et al. 2012).

-

(c)

Native capabilities and bricolage BoP markets are known for their challenging institutional and market environments (Hoskisson et al. 2000). A range of capabilities have been suggested to successfully navigate ‘institutional voids’ in these economies, emphasizing the need to draw on locally available knowledge, resources and networks. Building contextualized ‘native capabilities’ through effective combination of local and global knowledge is considered essential for developing solutions that are aligned with local contexts (Hart and London 2005). This requires the ability to create a web of trusted connections with a diversity of organizations and institutions to generate bottom-up development that builds on the existing social infrastructure to create competitive advantage (London and Hart 2004). Bricolage, or the ability of ‘make do’ with existing resources under highly constrained environments, is another characteristic of inclusive business approaches in the BoP (Mair and Marti 2009; Halme et al. 2012). This suggests a distinct approach for innovation and entrepreneurship that starts from the pool of resources and expertise within the firm’s network, rather than the standard organization-centric innovation processes.

Goal Hybridity and Identity Conflict

Hybrid organizations that combine social mission with commercial profit face the challenge of developing a new organizational identity that is commensurate with this hybrid mission (Battilana and Lee 2014). Goal integration is particularly challenging when multiple goals are perceived to be central to the organization but not compatible with each other (Besharov and Smith 2014). In social enterprises, for example, gradual shift of emphasis towards commercial goals induces mission drift, away from social goals (Ramus and Vaccaro 2017). To overcome such tensions, social enterprises are forced to selectively and gradually couple their social and commercial issues (Pache and Santos 2013) through a process of selective synthesis between social and commercial goals (Ebarhim et al. 2014).

Inclusive businesses could face frictions among adherents of different organizational goals that threaten their existence (Besharov and Smith 2014; Pache and Santos 2013). Organizational identity is a form of coherent organization-level narratives that consistently guides actions, and defines the nature of the organization’s relationships with its stakeholders (Pratt and Foreman 2000; Brickson 2007). Failure to develop a (hybrid) identity can lead to paralysis when employees fail to converge on a course of action, or to instability when different goals guide action at different times (Pratt and Foreman 2000). Organizations can also create new identities by synthesizing a novel, coherent identity that integrates elements of multiple old identities (Pratt and Foreman 2000). This can be done at the strategic level by changing organizational mission and vision, or operationally by inculcating employees with new values that are in line with a hybrid identity (Battilana and Dorado 2010). Identities that are deliberately constructed thus can provide organizational distinctiveness and competence (Kraatz and Block 2008). Far from constraining change, novel and distinct identities can be used consciously as instruments for change, including forming new types of engagement with its stakeholders (Brickson 2007).

Legitimacy and Governance Challenges

Legitimacy refers to the perception of a certain action or behaviour being desirable, appropriate or proper in a given social system (Suddaby et al. 2017; Suchman 1995). Novel inclusive business approaches, such as Benefit Corporations (‘B Corps’) and other hybrids, can struggle to acquire regulative legitimacy, which is often granted to organizations that fit institutionalized expectations (Kraatz and Block 2008; Pache and Santos 2013). Failing to fall neatly into pre-established mental templates, they could also struggle to achieve cognitive legitimacy among market and non-market actors (Aldrich and Fiol 1994; Mair and Marti 2009). Since legitimacy is the mechanism through which value is recognized and resources are allocated, this could expose them to problems for market and resource access. To establish cognitive legitimacy, concerted efforts might be needed to rationalize actions and prove their compatibility with goals (Ebrahim et al. 2014), an exercise that could be costly and difficult to coordinate (Pratt and Foreman 2000).

Radically innovative inclusive businesses challenge existing institutional arrangements and therefore invite resistance from more established actors (Mair and Marti 2009). Previous research has documented the importance of symbolic communications such as rhetorical strategies and persuasive language to acquire buy-in and reduce resistance to change (Aldrich and Fiol 1994; Suddaby and Greenwood 2005). Rhetoric strategies can be used to build an over-arching and integrative narrative, a ‘mythology’ or a shared vision that would effectively bind together diverse constituents and allow for the joint realization of incommensurable values (Kraatz and Block 2008). An ‘identity conserving’ narrative that endorses new identities without rejecting current ones can help actors accept change more readily by enabling them to conserve their current identity (Kraatz and Block 2008). Recent research has also underlined the importance of these mechanisms for avoiding mission drift in social and inclusive businesses (Tate and Bals 2016; Ramus and Vacarro 2017). Legitimacy acquisition, however, could also entail more aggressive strategies of challenging institutional norms and expectations or renegotiating existing value systems (O’Neil and Ucbasaran 2016).

Embeddedness

Economic action takes place in a context of social relations and structures (Granovetter 1985; Uzzi 1996; Tsai and Ghoshal 1998) and entrepreneurial action, therefore, should not be studied in isolation from its sociocultural context (Jack and Anderson 2002; De Carolis and Saparito 2006). Studies have explored how organizations develop and leverage structural embeddedness, which refers to the material quality, configuration or structure of ties among actors (Uzzi 1996; Tiwana 2008). Others have examined the importance of relational embeddedness, which indicates the nature and quality of the contents that are embedded with those social ties (Simsek et al. 2003; Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998). Relational embeddedness is comparable with the concept of social capital and includes relational attributes such as trust, reciprocity, status and norms (Adler and Kwon 2002). Both aspects of embeddedness are likely to be crucial for inclusive businesses that implement social innovations, which often require deep understanding of complex social issues (Anderson and Billou 2007; London and Hart 2004).

The structure and quality of social ties can have an effect on organizational performance by creating new opportunities or access to existing ones (Tsai and Ghoshal 1998). Researchers identify two broad categories of outcomes associated with embeddedness: resource access and governance. For social entrepreneurs, embeddedness can facilitate the exchange of resources through interpersonal ties, which are difficult to acquire through market exchanges (Uzzi 1996; Mair and Marti 2009). Bridging ties that expand the heterogeneity of the firm’s network can create external linkages that can be used to acquire new material and informational resources (McEvily and Zaheer 1999; Tiwana 2008). In BoP contexts, social ties have also been found to create access to intangible resources such as market-specific information and knowhow (Rivera-Santos et al. 2012), financial support (Bals and Tate 2018) as well as social support (Jack and Anderson 2002; Tate and Bals 2016).

Being embedded within organizational networks also provides a means of governance by facilitating resource pooling, cooperation and coordinated adaptation (Uzzi 1996). Embeddedness can shape the behaviour of actors by inhibiting opportunism and fostering the development of trust and reciprocity (Uzzi 1996; Hoang and Antoncic 2003). The incentive to adhere to norms and to build reputation can reduce uncertainty, thus enhancing cooperation among network members (Rivera-Santos et al. 2012). Social standing and affiliation with social groups can also send signals of status and reliability (Jack and Anderson 2002), which can provide a mechanism of legitimation in BoP economies that are characterized by institutional voids (London and Hart 2004; Khanna and Palepu 2000; Mair et al. 2012). Network-based relationships in these contexts can provide the means for navigating through the blurred boundaries between the firm, its market and government offices (Rivera-Santos et al. 2012; Hoskisson et al. 2000).

However, an extremely high level of embeddedness can also derail performance by sealing off the flow of new information and opportunities that exist outside the network. Kistruck and Beamish (2010) document that non-profit organizations that ventured into social entrepreneurship were constrained by high levels of cognitive, cultural and network embeddedness. Moreover, relational aspects of embeddedness such as trust, status, norms and reciprocity come with obligations that are associated with membership to specific social systems (Granovetter 1985). Organizations could face tensions between the diversity of informational and resource flows that arise from weak ties, and the quantity of flows that arise from strong ties (Hoang and Antoncic 2003). Simsek et al (2003) suggest that strong relational and cognitive embeddedness could be positively associated with incremental entrepreneurship, but negatively associated with radical entrepreneurship.

In conclusion, inclusive businesses need distinct resources, and often involve collaborative approaches to achieve systemic change, which suggests that embeddedness could play an enabling role in Base of the Pyramid (BoP) contexts. Current research highlights the importance of social resources for inclusive business approaches (Tate and Bals 2016; London and Hart 2004; Maak 2007), but fails to show how organizations build social networks and leverage them to advance organizational change. The following empirical sections use case study data to provide evidence on the role of embeddedness for facilitating transitioning towards inclusive business approaches. While drawing on the concepts introduced in this section, the goal is to formulate new theoretical propositions that shed light on the specific challenges that inclusive businesses face and how embeddedness can help alleviate them.

Method

The Safaricom Case

Safaricom is the largest telecom operator in Kenya with a market share of 71%, and a workforce of 5,434 employees in 2016 (Table A2, in Supplementary Material). It was incorporated in its current form in 2000 as a joint venture between the Government of Kenya (60%) and Vodafone Group of UK (40%). The government sold off 25% of its stake through a public offering in the Nairobi Securities Exchange (NSE) in 2008, which was bought by more than 600,000 individual investors. With total valuation exceeding 6 billion USD, Safaricom is the largest company listed in the NSE. The company is head of the local chapter of the UN Global Compact, a club of organizations that spearhead sustainable business practices. Safaricom has also integrated its operations and growth strategy with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and participates in the Business and Sustainable Development Commission (BSDC) to promote similar sustainable business approaches.

Safaricom is widely recognized for its mobile banking service called M-Pesa, which is credited for expanding financial inclusion among large segments of unbanked populations in Kenya. As of 2017, the service has enabled more than 27 million Kenyans (70% of the adult population) to open ‘mobile accounts’ that support services such as (international) money transfer, bill payments and microcredit using simple mobile phone devices (see Table 1). In the financial year ending March 2016, the value of financial transactions conducted through M-Pesa was Shs 5.29 trillion (equivalent to 85% of the country’s GDP), which shows that M-Pesa has effectively become the second currency of the country. In addition to peer-to-peer and customer-to-business payment services, M-Pesa supports short-term micro loans for millions of small businesses and individuals. Vodafone has also introduced M-Pesa in nine other countries globally, providing financial services by a network of more than 261,000 agents.Footnote 2

M-Pesa is a social innovation that was developed from the outset to address a pressing social need – lack of financial access—through a commercially profitable operation. In addition to extending financial services among tens of millions of users, M-Pesa has also become an important income source for more than 130,000 small-scale businesses that serve as its agents. The service was initially viewed as a side project (Vaughan et al. 2013), but eventually became of strategic value, contributing to more than 25% of revenues (see Fig. 1). Its radical success also paved the way for additional social innovations that built on the same platform to address social issues in sectors as diverse as water provision, education, energy, agriculture and health services (Table 1).

The revenue growth of M-Pesa and its contribution in total revenue. Notes: Revenue growth (right axis) has stabilized but remained high at 27% in 2016. The share of M-Pesa in total revenues (left axis) is consistently rising (21% in 2016), reflecting the relatively lower growth rate in other revenue streams.

Research Design and Data Collection

We adopt a case study research design that is suited to our need for in-depth analysis on questions of why and how inclusive business approaches emerge (Yin 2013). The use of a single case study design is motivated by the uniqueness of Safaricom (Eisenhardt 1989), which has been exceptionally successful in implementing social innovations. Safaricom has received global recognition for providing accessible and affordable financial and payment services to the financially excluded segments of society. Especially, M-Pesa has received several high-profile prizes, leading to the listing of Vodafone and Safaricom as number one in Fortune’s ‘Change The World’ List in 2015. As an endorsement for Safaricom’s success in creating social impact, its CEO was invited into the UN Global Compact by the UN’s Secretary in 2012 (for more details, please see Table A1 in the supplementary material).

We collected interview data in two rounds of fieldwork (in 2016) as well as on secondary data from multiple, diverse sources. Prior to data collection, we prepared a detailed case study protocol that included semi-structured interviews for guiding our data collection. This was informed by preliminary discussions with two middle level managers of Safaricom, who served as our major contact persons throughout the fieldwork. Preliminary analysis indicated that Safaricom had to partner with diverse actors to implement M-Pesa, and had to gain the trust of customers to deposit their money in a virtual account, a mechanism that was hitherto unknown. This suggested the presence of significant relational capital that enabled Safaricom to implement radical social innovations. Our semi-structured interviews were thus designed to find out how Safaricom earned the trust of its customers, and why it was able to get the consent of significant market and non-market actors to implement M-Pesa. This focused approach was chosen to make data collection manageable, avoiding the risk of being overwhelmed by the volume of data (Eisenhardt 1989).

The first round of fieldwork resulted in 32 interviews, out of which about half were conducted with middle level and senior managers of Safaricom, and the remaining 17 were with external partners (including M-Pesa agents and other organizations that collaborated with Safaricom). We used theoretical sampling procedures (Yin 2013) in close consultation with our contact persons to choose interviewees that were best-positioned to address our questions in terms of work placement and experience. In a few instances when it was not possible to get access to the selected interviewees, we modified our list by choosing among available potential interviewees. All but two interviews were tape-recorded, and transcribed for analysis in a qualitative data analysis software, NVivo 11. In the two cases where transcription was not possible, shorthand notes were taken and verified with the respondents. The duration of the interviews ranged between half an hour and two hours. Preliminary analysis of our data using open coding techniques confirmed the importance of social capital, and indicated the specific ways in which Safaricom’s reputation and embeddedness underpinned its social innovations. The analysis also revealed that social innovation in Safaricom was an ongoing activity and went much beyond M-Pesa, and had antecedents dating back to the early days of its establishment.

Subsequently, our attention turned to why Safaricom kept on developing social innovations and what organizational mechanisms lead to sustained interest in these innovations. To answer these questions, a second round of data collection was conducted in September 2016. Two of the co-authors travelled to Nairobi, and conducted seven semi-structured interviews in a period of 1 week. Moreover, an arrangement was made for a senior manager of Safaricom to visit the co-authors’ university and speak about the organization’s philosophy for social innovations, which took place 3 months later. The senior manager has been the chairman of the Safaricom Foundation for more than 10 years, was a member of the Board of Directors and was also head of the Strategy and Innovation Division of Safaricom. Three more in-depth interviews with the senior manager provided us with deeper understanding of the organizational philosophies of social innovation and the development of a mission-driven business identity within Safaricom.

In addition to the fieldwork, data were collected from media interviews, speeches and lectures by the current and former CEOs of Safaricom. The dramatic success of M-Pesa had attracted significant media attention, which resulted in a rich archive of interviews and other materials from publicly accessible online sources. Transcripts of these speeches, lectures and interviews were used to supplement our interview data, and were useful to get a more objective historical account from the perspective of top managers who were personally involved with introducing social innovations at Safaricom.

To build a longitudinal narrative of social innovations in Safaricom, we further used archival data from annual reports and other official statements by Safaricom, Vodafone, the telecom and financial regulators of Kenya (Central Bank of Kenya, CBK and Communication Authority of Kenya, CAK) and various partner organizations. Publicly available transcripts of speeches made by the Governor of the Central Bank, press releases by Safaricom and blogs by the CEO of Safaricom were used as additional data sources. We also used a few in-depth retrospective first person accounts that were written by individuals who played key roles during the initiation of the project including the former CEO of Safaricom (Vaughan et al. 2013; Hughes and Lonie 2007). Triangulation of evidence from diverse data sources was useful for identifying key episodes and activities, which were cross-checked with the retrospective accounts from interviews.

Data Analysis

The purpose of our research is to develop a model of organizational change towards inclusive business approaches. Given our focus on understanding an empirical phenomenon, we started off with a relatively broad focus to make sure that theoretical insights that emerge from the data can be easily accommodated (Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007). Our data analysis was iterative and overlapped with data collection, since we analysed our data after each round of fieldwork in order to inform subsequent interviews (Van Maanen et al. 2007). Generally, however, the following steps were followed in our analysis.

We started by constructing a detailed narrative account of Safaricom’s social innovations, focussing on the development and implementation of M-Pesa. We used archival data and retrospective accounts from our interviews to develop a provisional timeline of social innovations in Safaricom, which informed the content and structure of our subsequent interviews (Tables 1, A1). After each step of data collection, we used qualitative data analysis software (NVivo 11) to systematically organize and code our data. We started open coding with the broad aim of identifying organizational factors (such as relational capital) that were associated with the emergence of inclusive business approaches in Safaricom. As the themes of our coding expanded fast, standard text analysis techniques were used to identify major themes that address our research question (Braun and Clarke 2006,) from which we developed higher-order aggregate themes (Gioia et al. 2013).

As we progressed in our coding and sought to answer why social innovations arose and how they were implemented in Safaricom, we started to consult various studies to inform and direct our analysis. In the beginning, we focussed on the literature on social capital, but we soon realized that internal processes associated with organizational change were prevalent in Safaricom. We therefore used the literature on hybrid enterprises, and inclusive and sustainable business models to identify relevant themes. Finally, we built on the broader literature on embeddedness to frame our contribution on the emergence of social innovations. Our subsequent step was developing a model to explain the emergence and institutionalization of inclusive business approaches, which pointed to the importance of developing a mission-driven identity for mitigating hybridization challenges. To enhance the analytical generalizability of the results, we generate theoretical propositions that can provide a roadmap for empirical testing (Gioia et al. 2013). Testable propositions can provide firmer grounding in theory, and advance future research by enabling the development of sharply defined research constructs (Eisenhardt 1989). To check the validity of the results, preliminary results from the analysis were presented at a research workshop attended by senior management staff of Safaricom who had been involved in the development of M-Pesa from its inception. The feedback from this meeting and other consultations with Safaricom staff were used to refine the analysis. Table 2 summarizes the various steps we followed to ensure the reliability and validity of our results.

The Emergence and Implementation of Social Innovations in Safaricom

Our analysis suggests that Safaricom has developed strong structural and relational embeddedness with a large number of important actors in Kenya. As a dominant firm with more than 70% of market share, Safaricom sits at the centre of an extensive telecom network that encompasses individuals, communities and organizations across the entire country—a position that can provide access to people, resources and information. As a company jointly owned by the government and Vodafone, Safaricom also occupies a bridging network position that straddles private and public sectors, and domestic and foreign economies. These bridging ties potentially provide access to unique tangible and intangible resources that would otherwise be out of reach because of structural holes related to institutional or geographic distance (McEvily and Zaheer 1999; Tiwana 2008). Moreover, a quarter of the company’s shares that are traded in Nairobi Stock Exchange are owned by more than 600,000 individual shareholders (as of 2016), creating a broad sense of ownership among a large number of Kenyans.

Safaricom also has strong relational embeddedness as a trusted local company, which has been consciously built over the years. Although managed and partly owned by Vodafone, Safaricom has successfully branded itself as a genuinely Kenyan company, which is apparent from its motto of ‘Transforming Kenyan’s Lives’. This was an outcome of a deliberate branding strategy crafted during the company’s formative years to create better emotional connection with Kenyans (Tuwei and Tully 2017). The company exploited its first-mover advantage in Kenya to develop an image of a flagbearer operator that represented the whole nation. Safaricom’s marketing and promotional campaigns often profile the company as “Proudly Kenyan”, which blended collective sentiments with a message of service quality and reliability to create a positive corporate image (Tuwei and Tully 2017). The remainder of this section will show how embeddedness inspired the initiation, implementation and sustenance of mission-driven business activities in Safaricom.

The Imperative for Social Innovation

We identify two aggregate concepts that can explain why Safaricom started to engage in social innovations: pragmatic and ethical imperatives. These imperatives are strongly related to Safaricom’s structural and relational embeddedness.

Ethical Imperative

The emphasis on Safaricom’s Kenyanness was initiated as a branding strategy but led to the gradual development of a genuine sense of community that inspired strong social engagement through philanthropic interventions and commercial social innovations. Just 3 years after its formation, the company established the Safaricom Foundation, which remains one of the largest foundations in East Africa. The foundation invested in hundreds of social projects on water provision, health services, education and agriculture, and has been involved in addressing nearly all major social issues facing Kenya, from the fight against HIV/AIDS, to state capacity building, curbing corruption and improving agricultural productivity. Safaricom started to introduce product adaptations that sought to empower disadvantaged customers right after its establishment, including per-second-billing (2000), small-denomination scratch cards (2002), free ‘call me back’ SMS services (2005) and an emergency credit airtime (‘Okoa Jahazi’, since 2009). ‘Okoa Jahazi’, for example, provides airtime credit with deferred payment for people who are unable to pay, and is currently used by 13 million users about 2.5 times a week. These and other similar initiatives by Safaricom (for an overview, please see Table A1 in the supplementary material) fostered the development of a credible reputation as a company committed for the collective wellbeing of Kenyans.

The reputational capital of Safaricom in its community also came with implicit obligations for reciprocity that gave impetus to social innovations. The need to fulfil Safaricom’s societal obligations as a notable player in the Kenyan economy was an important motivation for its engagement in social innovation. This was evident from the formative years of Safaricom when it inspired the formation of the Foundation, as recounted by a senior manager of Safaricom:

If you live in Kenya, poverty is very common … there is no medical insurance or other social security. At some point, our CEO said, let’s start a foundation to deal with these issues. And let’s start thinking how we can grow even as we grow other people and our customers.

The empowerment of disadvantaged communities such as women, farmers and generally low-income people is a common theme in Safaricom’s narrative of social innovation. Especially, products related to M-Pesa are presented as means of empowering disadvantaged groups or expanding financial inclusion for ‘unbanked’ people. When asked why Safaricom’s staff refer to M-Pesa micro loans as ‘dignity loans’, the account manager of M-Shwari explained as follows:

I can sit in my house and access loans... I don’t need to go and embarrass myself. Sometimes people say borrowing is embarrassing. I can get it right on my phone, based on things I deserve... It is my [credit history], it is my relationship with telco that’s earned me that loan.

The notion of empowering disadvantaged customers and communities goes back to the early years of Safaricom, but gained increasing prominence in underpinning social innovations (for an overview, please see Table A1 in the supplementary material). A senior manager highlighted their partnership with the World Food Program to support refugees’ access as follows:

Typically, in the World Food Program would import food from wherever that food is available and distribute to the refugee camps, which causes a logistical problem. Now we work with [them] to create a mobile wallet through M-Pesa. The money is sent to each person’s mobile through that wallet, and it is specifically used to buy food in the neighborhood. What this has done is that … the refugees do not suffer the indignity of having to queue for food. They … can buy the food in their neighborhood, which has also just created a local economy around the refugee camps.

These quotes illustrate how ethical considerations that emanate from Safaricom’s relational embeddedness and its collective image as a ‘good Kenyan company’ have compelled the company to adopt a normative approach for doing business.

Proposition 1

Strong social embeddedness creates a moral pressure on the organization to internalize social issues, thus creating an incentive to engage in social innovations.

Pragmatic Imperative

Another key motivation for Safaricom to take up social innovation appears to be appreciation of the complementarity between social impact and financial profit. The emphasis on the synergy between the organization and its community is in part due to the strong collective image described above, which created an overlap between Safaricom’s customers and its ‘communities’ (the Kenyan nation). This has resulted in greater alignment between social and commercial goals, which increased the appeal of social innovations that are both profitable and beneficial to communities. Social innovations, therefore, were driven by the pragmatic view that they were both necessary and compatible with core commercial operations.

An example of this is Safaricom’s apparent confidence in the market potential of the poor, and its keenness to find a way to meet their needs. This motivated the introduction of per-second-billing in 2000, which made Safaricom particularly popular among low-income workers in Kenya’s large informal sector. This appreciation of the price sensitivity of the poor gave Safaricom an edge over its competitor, Kencell, which had the advantage of starting a few months ahead of Safaricom but kept on charging its subscribers per-minute. Another example is the introduction of free ‘call-me-back’ SMS service that was introduced to eliminate the common practice of ‘flashing’ (i.e. calling a mobile and hanging up before the call is answered). Safaricom clients used flashing as a cost-free way of letting their family or friends know that they would like to be called back. Low-income users throughout Africa use it when they are low on pre-paid credit, or when they think the other person has a better reason to pay for the conversation. But flashing was an irritant to Safaricom as it congested the network without generating call revenues. The company’s solution to this dilemma was allowing customers to send a free, standardized text message that reads: “Please call me. Thank you”.

The CEO explains Safaricom’s attitude towards low-income customers as follows in an interview:

“We believe that if we have 19 million people [i.e. users of M-Pesa] transacting small amounts, making small amounts, it will add up. For each transaction, there is a small fee… That way we were able to make a quarter of a billion dollars of revenues”.

The above quote illustrates the pragmatic way in which Safaricom approached social issues such as poverty, which brought strong understanding of local needs. When the pilot for M-Pesa was initiated by Vodafone in 2003, it was intended for a very different purpose of facilitating repayment of microfinance loans using mobile devices. However, it turned out that M-Pesa was not conducive for supporting microcredit payments since the virtual nature of mobile-based loan transactions weakened interpersonal ties that were crucial for enforcing loan repayments. Yet, the pilot revealed that mobile phones could have a considerable potential for enabling domestic and international remittances.

Like most developing countries, Kenya exhibits a ‘dual economy’ that includes relatively well-off urban centres that attracted job-seeking migrants from significantly poorer rural areas. As a result, there was notable flow of domestic remittance by family members working in urban areas to their families in rural areas. Since rural areas had very low bank penetration due to their sparse population density, remittance senders had to rely on informal means that were risky and inconvenient. Once Safaricom noted this latent demand in the pilot stage, it altered M-Pesa into a money transfer service with a simple interface that works on basic phones, supports SMS in the local language (Swahili) and is accessible to semi-literate users. The service was launched in 2007 with a simple but clear marketing message of ‘Send Money Home’. Only after customers became used to this money transfer service were other functionalities introduced, including utility bill payments (since 2009) and microcredit services (since 2010).

Embeddedness was thus crucial for strengthening the alignment between social and commercial issues, as it increased greater awareness of local needs. Extensive ties with broad segments of society also made social innovations commercially feasible by creating a large potential market for them. Further, a history of social engagements and product modifications increased awareness of the potential commercial value of social issues, strengthening the motive for social innovations.

Proposition 2

Strong embeddedness enhances the compatibility between commercial and social causes, thus creating an incentive to engage in social innovations.

Implementation Processes

Resource Access

Social innovations that aspire to achieve widespread social impact are unlikely to be conceived and implemented by a single organization that has a narrow domain of capabilities (Calton et al. 2013; Austin and Seitanidi 2012). Business organizations that seek to advance social causes, therefore, tend to engage in strategic partnerships and collaborative ventures that mobilize resources and competences from different partners (Webb et al. 2010). Safaricom’s social innovations cater for important societal needs in education, health, agriculture and water services that are poorly provided in developing countries. These ventures require specialized knowhow and expertise in diverse fields that could not be readily sourced from a telecom company such as Safaricom. Many social innovations were also initiated by NGOs, businesses or individual actors who wanted to partner with Safaricom to leverage its Information and Communications Technology (ICT) expertise. Given the difficulty to assess the market risk involved in such divergent fields, these partnerships had also the advantage of shielding Safaricom from the financial and market risks associated with operating in new markets. A manager summarized Safaricom’s approach for partnerships as follows:

“As a mobile phone company, once upon a time we were able to do everything – we would build our own base stations, etc. Now, in order to deliver some of our solutions, we have to work in partnership … with development partners, with NGOs, with governments, and we are finding some interesting experiences. We’re getting some really good and useful solutions, but we are also learning a lot”.

The development and implementation of M-Pesa illustrates how partnerships are leveraged to access diverse resources from multiple actors. The pilot was made possible with the help of a seed money of 1 million British Pounds from the British Department for International Development (DFID) that was matched by an equal contribution from Vodafone. The service today is offered through a collaboration of three major firms—Safaricom, Vodafone and Commercial Bank of Africa—that contribute their unique competences. Vodafone is responsible for developing and maintaining the technological platform of M-Pesa, including continued software adaptations to address technical issues and add new functionalities. Safaricom is in charge of marketing and brand management considering its positive brand image, solid marketing expertise and wide reach across the country. Commercial Bank of Africa (CBA) hosts the trust account in which the money that flows through the M-Pesa system is saved, while also being responsible for microfinance and other services that involve banking permit and expertise. The involvement of diverse partners in the ecosystem not only contributed to a speedy early adoption of M-Pesa, but also enabled the service to be embedded into various payment and financial platforms that led to more intensive use.

Safaricom maintains internal and external innovation portals that seek out “innovation ideas for services or products that bring change to people’s everyday lives” (interview with Director of Strategy and Innovation). Proposals are routinely evaluated with winning projects gaining financial and organizational support to develop into full ventures. An annual competition program called Appwiz Challenge seeks out software developers and provides winners with small grants, training and mentorship to help them launch their businesses. Safaricom has also initiated a venture capital fund that has successfully financed a number of mobile tech start-up ventures, which received business development support and technical assistance from Safaricom.

Proposition 3

Embeddedness in extensive social networks gives access to diverse resources for implementing social innovations through collaborations with external partners.

Legitimacy Acquisition

Social innovations such as M-Pesa rely on new forms of institutional arrangements and organizational forms, requiring significant efforts of external legitimation (Suddaby and Greenwood 2005). For example, new users had to deposit cash with agents whom they did not know in order to open an M-Pesa account, which required trust when the service was still new. Knowing this, Safaricom systematically linked M-Pesa with its brand name by demanding that M-Pesa agents do not serve any other mobile money service providers, and visibly display the Safaricom logo in their shops, including uniform wall paintings in the recognizable ‘Safaricom green’ colour. Safaricom, therefore, sought to strengthen cognitive legitimacy (Aldrich and Fiol 1994) by associating its social innovations with its well-known and trusted brand image to promote favourable judgement among new users.

An interviewee in an organization working in partnership with Safaricom summarized the company’s active marketing approach to change minds as follows:

Remember - there is a need for mind-set change. [Some] people still don’t believe that you can save money and send it in a phone. So you need many consumer activation and education programs. In Safaricom…. they would go to factories and talk about M-Pesa to the workers. They would tell them these are the benefits of M-Pesa and during that time, there is also an agent. Therefore, anyone who wants to register can do so. And they give them incentives to make sure they are registering and [using it for] sending money.

Our data revealed three aspects of legitimation acquisition. The first is acquiring buy-in from important stakeholders, especially the Central Bank and from competing commercial banks that could have derailed the product. Regulatory provisions that govern mobile-based financial services were not available in Kenya when M-Pesa was introduced, which required efforts to create regulative legitimacy. Safaricom approached the Central Bank (which was not its regulator as it was a telecom firm) during the pilot to request critiques and suggestions, and the engagement continued as the product was being developed (Vaughan et al. 2013). Lacking in similar precedents, the Central Bank worked closely with Safaricom to address regulatory aspects of the service, which created an opportunity for co-designing an entirely new regulatory mechanism for the product (Hughes and Lonie 2007). In the process, Safaricom adopted the Central Bank’s policy narrative of extending financial inclusion for ‘unbanked’ populations in Kenya. Since promoting financial inclusion fell within the jurisdiction of the Central Bank, this enabled Safaricom to emphasize the innovation’s potential to catalyze financial inclusion, and consequently the need for a more benign regulatory framework. This alliance was crucial since the Central Bank’s approval was required every time a new functionality was added to M-Pesa.

The second type of legitimation activity is defending achievements by countering resistance from powerful commercial banks that felt threatened by the innovation. Social innovations that affect existing power structures can initiate contestations from established organizations or ‘institutional defenders’ whose interests are adversely affected by institutional and technological change (Battilana et al. 2009; Suddaby and Greenwood 2005). Following the rapid adoption of M-Pesa, the service faced a resistance from Kenya Bankers’ Association, which complained against the regulatory framework of M-Pesa. This resulted in a formal probe by the National Treasury and the Central Bank of Kenya which eventually vindicated M-Pesa. Table 3 summarizes this and other incidents in which Safaricom had to defend its social innovations against incumbents. The company still faces accusations for being a dominant player and engaging in anti-competitive practices, with competitors sometimes calling for regulators to force M-Pesa be split apart from the rest of Safaricom. The CEO of a competing telecom firm complains in a news interview against Safaricom’s restrictions on its own subscribers from using double SIM Cards as follows:

“Anyone who wants an M-Pesa account must have a Safaricom SIM card – and since M- Pesa is essentially the country’s second currency, most people do. So instead of making [Safaricom] the only SIM, we are pushing for double SIM phones, the goal being to provide voice and data services alongside M- Pesa. But in the long term it is very difficult to compete against [such] a dominant operator”.

Safaricom complained that the use of double SIM cards on a single phone could compromise data stored within the M-Pesa system and expose confidential financial communication for interception. A dispute on this issue between Safaricom and a competing service called Equitel (offered through a partnership between Equity Bank and Airtel telecom) ended with the temporary setback for Safaricom as the regulator allowed Equitel to proceed with a one-year trial period (see Table 3). These struggles to acquire legitimacy highlight the political nature of entrepreneurship, which require diverse legitimation efforts to counter the resistance from incumbents (Suddaby and Greenwood 2005; Scott 2014).

The third form of external legitimation strategy is acquiring and exploiting endorsements to achieve greater service adoption, which involved active engagement to demonstrate the social impact of M-Pesa through various channels of communication. Consequently, Safaricom started to partner with commercial banks to integrate them into the value chain of the service. This started in 2008 with the integration of M-Pesa with the Pesa-Point ATM network, which allowed users to withdraw money from ATMs. By allowing their clients to manage their bank accounts through M-Pesa, banks were able to achieve significant cost savings in reduced operational costs. A number of banks also initiated strategic partnerships with Safaricom to launch innovative financial products that supported saving accounts, interest payments, microcredit and insurance (see Table 1). Through co-creation, therefore, Safaricom was able to placate opposition from incumbent banks, and be able to integrate the service with existing service platforms.

Proposition 4

Being embedded in extensive networks facilitates legitimizing radically new social innovations by creating opportunities for interaction and collaboration.

A Mission-Driven Identity

Safaricom’s social innovations, especially M-Pesa, have achieved significant recognition for their social impact. Activities related to M-Pesa contribute to 25% of Safaricom’s total revenues, which is growing twice as fast as other revenue sources (Fig. 1). Moreover, M-Pesa and other social innovations have indirect effects, such as attracting and keeping customers. Since M-Pesa has become an integral part of Kenya’s economy, it compelled new subscribers to opt for Safaricom SIM cards instead of its competitors’, thus locked-in existing customers while attracting new ones. The expanding set of functionalities in M-Pesa became additional mechanisms for keeping customers engaged and remain loyal to Safaricom.

The success of social innovations in Safaricom led to the gradual adoption of social issues across the board within Safaricom, which is illustrated by the rise of keywords related to social mission in Safaricom’s annual reports (Fig. 2). Consequently, a new mission-driven identity emerged in Safaricom which was crystalized with the adoption of a new motto in 2012: ‘Transforming Lives’. In the same year, Safaricom started to report its sustainability performance through a separate sustainability report following GRI guidelines. This indicates the diffusion of social causes from the M-Pesa to the rest of the organization, making social impact an organization-wide phenomenon that defines the entire organization.

Frequency of word incidence related to social mission in Safaricom’s annual reports. Note The graph indicates the frequency with which words indicating social mission appeared in Safaricom’s annual reports. Seven words were used for capturing social mission, namely ‘social’, ‘society’, ‘transform’, ‘lives’ ,‘community’ ,‘impact’ and ‘local’

The success of M-Pesa both on social and financial fronts contributed to the development of a mission-driven identity as it proved the compatibility between social mission and commercial profit. This, however, was not a sufficient precondition for the development of a full-fledged mission-driven identity. Such a change was an outcome of the need to align increasing goal diversity and process incongruence that started to emerge following the rapid growth of M-Pesa and related social innovations. A separate Financial Services business unit dealing with M-Pesa matters was established in 2011, and a year later a division of Strategy and Innovation was established to steer the proliferating innovation activities that grew around M-Pesa. The growing importance of financial services and related innovations invited questions of whether Safaricom was a bank or a telecom firm. Although Safaricom’s managers consistently downplayed the importance of such a distinction, the question often cropped up in media interviews, pointing to poor cognitive legitimacy among the public. It also became a point of accusation against Safaricom’s dominant market position by critiques and competitors (see Table 3). Increasingly, therefore, the success of social innovations introduced diversity in organizational goals and activities, which appeared to undermine the company’s legitimacy. This became more noticeable as the company engaged in more partnership-based social ventures in sectors as diverse as health, education and agriculture (see Table 1).

Before ‘transforming lives’ became a ‘strategic priority’ of Safaricom in 2012, it used to be a defining feature of its Financial Services business unit, that was from the outset driven by the socially inspired goal of financial inclusion. In contrast, the remaining departments remained focused on their original, commercially oriented business model. This introduced diversity of goal and purpose within the organization, inviting confusion among stakeholders, necessitating greater emphasis on social mission as a bridging mechanism. The following quote from Safaricom’s 2011 communication report to the UN’s Global Compact illustrates this point:

Safaricom 2.0 embodies a more inclusive, outward-looking organization that is customer-centric and operates in a sustainable ecosystem that seeks constructive advantage over competitive advantage. This will be achieved by listening more to our stakeholders … in order to build a culture of honesty and trust.

Safaricom’s annual report on the same year (Safaricom 2011) also emphasized the importance of organizational change, stating that “Safaricom 2.0 demands a change in our structure, our culture and our mind-sets towards the stakeholders who make up our business ecosystem” (emphasis added). The development of a mission-driven identity, therefore, was strongly intertwined with organizational restructuring and change. A year later, Safaricom’s report to the UN’s Global Compact introduced the company’s new motto stating that: “At Safaricom Limited, we have developed a long term strategy focused on ‘transforming lives’. ... We recognize that the way in which we run our business, the value that we add to Kenyans, and our conduct and business practices must be designed to create and shape a sustainable tomorrow”.

Safaricom’s new mission-driven identity was thus a response to the increasing diversity of goals across business units, and the resulting sense of dissonance, which created the need for a more coherent ‘meta-narrative’. ‘Transforming lives’ emerged as a dialogic means to bestow a consistent (re)interpretation of existing and emergent activities in a manner that placates a broad range of stakeholders. However, this narrative was not merely dialogic as it also informed strategic decisions, with material consequences on organizational goals, structures and processes as it enabled Safaricom managers to develop tailored strategies for implementing social innovations.

The absence of organizational structures and processes to implement social innovations prior to 2012 forced managers to operate in an ad hoc manner, replacing personal commitment for strategic support that was lacking. For example, social innovations consumed significant amount of resources and took long time horizons to be profitable compared to purely commercial innovations. The willingness to invest significant amounts of resources, and to operate at loss for extended time periods were both critical for the success of M-Pesa. In an interview, Michael Joseph, CEO of Safaricom at the time M-Pesa was launched, emphasized the importance of sufficient resource allocation:

“The number one thing you need to have is 100 percent support from the top management from the CEO and down. Determination to be successful. This is a product you need to be passionate about. It is not a product that you do with your head”.

This quote highlights that bringing social innovations to success is a strenuous challenge that can be futile without proper organizational structures and processes to support it. After the new mission was adopted, Safaricom created a dedicated social innovation unit, which recognized the fact that the gestation period and process of implementing for social innovations could be different from decidedly commercial innovations. Safaricom also adopted a portfolio approach by combining various projects with varying degrees of social mission and thus financial risk, while also including social impact as one criterion for evaluating all innovations.

Adopting a mission-driven identity enabled Safaricom to adapt its organizational processes and structures towards meeting increasingly important hybrid goals. The endorsement of social mission also meant that ‘transforming lives’ was not a side job, but rather a strategic commitment, providing a justification for pursuing a broad spectrum of social innovations. Interviewees emphasized a normative approach of doing business, for example, quoting their CEO that “if you do the right things, the right numbers will follow”. The company’s mission-driven identity thus offered a ‘meta-narrative’ that reconciled potentially conflicting goals, while also rationalizing impending organizational change for relevant stakeholders.

Proposition 5

A mission-driven identity enables hybridization in business organizations by providing a meta-narrative that bridges goal diversities and rationalizes structural and process changes.

Discussion

A Model of Organizational Change

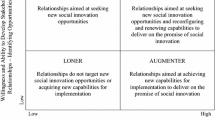

Figure 3 depicts our model of organizational change that culminates with the emergence of a new mission-driven organizational identity. High level of social embeddedness with a broad set of stakeholders heightens the imperative for implementing social innovations that have explicit focus in social mission. Strong embeddedness and the associated development of a collective image not only made it a moral obligation for Safaricom to internalize social issues, but also provided strong complementarity between social and economic outcomes that enhanced the pragmatic feasibility of social innovations.

Social embeddedness also provided strategic benefits in the form of resource access and legitimacy acquisition, both of which were crucial for implementing social innovations. Finally, successful social innovations create a positive feedback loop that sustains social innovations by enabling the emergence of a new mission-driven organizational identity. The feedback loop highlights the iterative development of inclusive business approaches, which could start with isolated, experimental innovations before expanding organically to the rest of the organization. Social mission in Safaricom was at first limited within a decoupled foundation, then it became a core element in an expanding Financial Services division (M-Pesa), before eventually becoming an organization-wide phenomenon with the development of a mission-driven identity. These results tally with the process of gradual, step-wise integration of social and commercial goals that has been documented in the literature on social enterprise (Pache and Santos 2013; Ebarhim et al. 2014). However, the impact loop could also have been negative if social innovations had become unsuccessful and discouraged further commitment towards social innovations.

The results indicate how new hybrid identities can be consciously developed to give meaning to apparently conflicting goals and processes. Hybrid business practices such as social innovations lack taken-for-grantedness (Suchman 1995), requiring efforts to build cognitive legitimacy (Kistruck and Beamish 2010) by drawing on recognizable and comprehensible ‘meta-narratives’ (Ruebottom 2013). Safaricom’s mission-driven identity offered a ‘meta-narrative’ or ‘master frame’ that legitimized change for a broad spectrum of internal and external stakeholders. The narrative was targeted at bridging cognitive gaps (dissonance) associated with organizational goal diversity that emerged in the process of hybridization, and at rationalizing organizational changes. Moreover, it enhanced pragmatic legitimacy (Suchman 1995) as it strongly emphasized the compatibility of social and commercial goals, and the alignment of the interests’ diverse stakeholders in order to achieve greater public endorsement. A mission-driven identity thus provided a formal mechanism of sustaining the company’s societal engagement while also providing a narrative that legitimizes this for its stakeholders.

Contributions

Our results provide nuanced answers to the questions of why and how business organizations adopt inclusive business models. By invoking the concept of social embeddedness, we provide strong empirical evidence on the motives, implementation processes and sustenance of inclusive business approaches in for-profit business organizations.

Motives for Inclusive Business Approaches

Organizational change towards inclusive and sustainable business approaches is constrained by significant organizational and institutional barriers. Research highlights that misalignment of interests and motivations inhibits businesses from meeting their maximum potential in terms of addressing social and environmental issues. Table 4 summarizes how resistance to change and lack of motivation can inhibit organizational change, and how embeddedness can alleviate these barriers. Social embeddedness in the form of reputation can enable organizational change by reducing the uncertainties of introducing sustainable and inclusive business approaches (Rindova et al. 2005). Especially in BoP contexts, values of trust and reciprocity provide alternative governance mechanisms that reduce information asymmetries and the associated uncertainties of entrepreneurial initiatives (Rindova et al. 2005; London and Hart 2004). Embeddedness and a strong sense of communal belonging can hence encourage experimentation with social innovations by reducing the risk of failure associated with business model change. Our results reveal how embeddedness can help break inertia and enable organizational change towards inclusive business approaches, and how social innovations provide opportunities for co-creation that involve deep engagement among diverse societal stakeholders (Roloff 2008; Werhane et al. 2010).

Implementing Social Innovations

Social innovations are different from other forms of innovation in that they entail dealing with complex social issues (Anderson and Billou 2007). Our analysis suggests that substantial amounts of diverse resources are needed to implement social innovations, which are difficult to source within a single organization. Embeddedness makes it easier to form cross-sectional partnerships to mobilize sufficient resources and expertise for implementing social innovations, while greater social engagement can also help build ambidextrous capabilities. Since social capital is a fungible resource (Adler and Kwon 2002), reputational benefits that come from social innovations that do not succeed financially can still be advantageous.

Embeddedness particularly comes handy when novel social innovations have elements of institutional entrepreneurship because of the need to modify institutional arrangements and creating novel organizing principles (Suddaby and Greenwood 2005; Battilana et al. 2009; Maguire et al. 2004). Embeddedness can be used for countering resistance for change, or for acquiring buy-in from important stakeholders such as customers, potential business partners and regulators. The results reveal how institutional entrepreneurs combine aggressive strategies with more adaptive and conciliatory approaches for acquiring legitimacy (Mair et al. 2012).

This study also shows how social innovations can offer a context for studying issue-focused stakeholder engagement to better understand the dynamic relationship between the firm and its social environment (Roloff 2008; Payne and Calton 2002). Although embeddedness appears to be crucial for the performance of social innovations, successful innovations further strengthen embeddedness. Our analysis, therefore, confirms the dynamic, bi-directional relationship between organizational action and performance and its social context (Maguire et al. 2004; Battilana et al. 2009). As an embedded social agent, the firm is reciprocally affected by its interactions with its environment (Werhane et al. 2010; Calton et al. 2013), rather than being a passive network member, or a purposeful instrumental actor (Calton and Payne 2003; Claasen and Roloff 2012). Compared to most of the existing literature that takes a relatively simplistic view of social resources as amenable to be wilful manipulation for organizational end use (Adler and Kwon 2002; Ramus and Vaccaro 2017), our model provides a more nuanced depiction that emphasizes the interdependence between the organization and its social context.

Sustaining Inclusive Business Approaches

Our analysis confirms that experimentation with social innovations can hasten organizational change by allowing the fusion of values, practices and norms (Battilana et al. 2009; Greenwood and Suddaby 2006). Through experimental social innovations, Safaricom discovered ‘hidden (resource) complementarities’ (Hockerts 2015) that enabled it to systematically integrate its social and commercial goals. Experimentation can thus purposively used to trigger surprises, to elicit learning by doing and even provide a turning point for forming new identities through learning “who we are” as an organization (Dentoni et al. 2017).

Our analysis implies the malleability of organizational identity, which can be adapted in response to strategic reorientations (Greenwood and Suddaby 2006). We find that identity formation is informed by doing, as identities are imprinted through iterative and interactive processes that involve communication and rhetoric (Dentoni et al. 2017). Identity formation has thus a sensemaking element of discovering what we are good at (‘epiphanies’), and eventually recasting preferred attributes as defining identities (Grimes 2010). The results show how adaptive organizations can escape the constraints imposed by their institutional identities and can even “reinterpret those identities in order to serve their own changing needs and purposes” (Kraatz and Block 2008). A mission-driven identity offers such a reinterpretation of existing practices by manipulating the audience’s cognitive schemes to legitimize change and bring about a shared understanding of the organization’s purpose, goals, structures and processes, facilitating hybridization processes and overcoming the related organizational tensions.

Managerial Implications

Our results have a number of managerial implications. Firstly, they reveal the importance of drawing on embeddedness for creating social impact in BoP contexts. Rather than relying on arms-length market strategies (London and Hart 2004), firms that draw on social resources could have better chances of breaking into new markets and developing novel social innovations. While building and nurturing social ties can take significant time and resources, our results indicate that they can yield long-term strategic benefits by enhancing the organization’s ability to create systemic social impact in a profitable manner.