Abstract

The pressure of oversight and scrutiny in the business-to-business purchasing process has the potential to cause psychological distress in purchasing professionals, giving rise to apprehensions about being ethically inappropriate. Utilizing depth interviews with public sector purchasing professionals in a phenomenological approach, the authors develop the notion of ethical purchasing dissonance to explain the psychological distress. An inductively derived conceptual framework is presented for ethical purchasing dissonance that explores its potential antecedents and consequences; illustrative propositions are presented, and managerial implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Purchasing is an economically significant boundary spanning function for both private and public sector organizations. Given that large sums of money are budgeted for purchasing in both the private and public sectors (Carter 2000; U.S. Budget Table 15.2 2016), the expectations from purchasing professionals center on effective and efficient stewardship of organizational resources (e.g., Lindskog et al. 2010). To that effect, any unethical activities by purchasing professionals (such as ordering sub-optimal goods in return for supplier favors) could be damaging to their organization’s success (Carter 2000). Purchasing professionals, thus, are expected to stay within defined ethical boundaries throughout the decision process, and this pressure of oversight is potentially anxiety inducing (Ghere 2002). Such apprehension could lead to underperformance and loss of productivity for the purchasing professional, and consequently the organization (DeTienne et al. 2012). Therefore, in this study, we attempt to explore the nature of ethics-related psychological distress in the purchasing process.

While past literature has examined general stress in the work place (i.e., Mullgn 1997; Pryor et al. 1991), and more specifically role stress (i.e., Boles et al. 1997; Jaramillo et al. 2011), and moral stress (i.e., DeTienne et al. 2012; Reynolds et al. 2012), the stress and anxiety associated with compliance of ethical expectations in purchasing have not been specifically examined; this leaves a gap in our understanding of purchasing ethics. Additionally, the literature has predominantly focused on ethical decision-making and fraudulent behavior (e.g., Lansing and Burkard 1991; McCampbell and Rood 1997), but the psychological state of purchasing professionals remains underexplored. Our purpose, therefore, is to explore the nature of psychological distress that could arise when purchasing professionals have to operate under ethical oversight; such distress, for instance, could be rooted in the uncertainty of violating some ethical boundary, or in unintentionally giving the appearance of ethical transgression while trying to do the right thing.

We chose public sector purchasing as the context for our study for multiple reasons. First, the purchasing function in the public sector is idiosyncratic in that it faces continuous pressures of federal/state regulatory controls, public transparency, and audits (Hawkins et al. 2011; IIA 2012; Larson 2009). This additional oversight and scrutiny in the public sector has the potential to create pronounced psychological distress for purchasing professionals who attempt to conduct themselves in an ethical manner (Ghere 2002). Second, it is an important context given the economic significance and the large volume of purchase orders placed by public sector purchasing professionals. In the U.S. alone, governmental expenditures for 2016 were estimated to have eclipsed $6.7 trillion, up from a reported $44 billion of U.S. spending in 1948 (the earliest year reported by the government as of July, 2017Footnote 1). Third, the high volume of business generated by the public sector often incites media interest and public suspicion in the purchasing process. Such public scrutiny puts purchasing professionals under a persistent ethical spotlight, which could have psychological ramifications for the individuals in charge.

Thus, we seek to understand ethics-related psychological discomfort that purchasing professionals may experience, in an environment characterized by high levels of scrutiny. Given that this is a new and sensitive area of inquiry, we utilize an inductive qualitative methodology to take the first step in exploring and uncovering this phenomenon. Specifically, we address the following research questions: What is the nature of psychological discomfort related to ethics in purchasing? What are the antecedents of this discomfort? And, what coping mechanisms do purchasing professionals utilize to deal with it? We examine these questions using a phenomenological approach including depth interviews with 24 public sector purchasing professionals across the U.S. As an outcome of our analysis of the qualitative data, we conceptualize the notion of ethical purchasing dissonance to capture the psychological discomfort experienced by purchasing professionals. Further, we draw on our findings to inductively derive a conceptual model of the antecedents and outcomes of ethical purchasing dissonance, and provide propositions related to the same. In the final sections, we discuss implications and future research areas.

Background

Ethics and Purchasing

Several ethically questionable practices associated with the purchasing function have been highlighted in extant literature (Cooper et al. 2000; Forker and Janson 1990; Hawkins et al. 2011; Landeros and Plank 1996; Rudelius and Buchholz 1979), including: giving preference to hand-picked suppliers, accepting gifts of any sort (trips, entertainment, etc.), providing information about competitors to suppliers, showing preference to suppliers who are also customers, allowing nepotism by upper management, accepting sales prizes and promotions, accepting incentives for large volume purchases, and allowing suppliers to circumvent the purchasing department. For the purpose of our study, we follow the Jones (1991) definition of an ethical decision, i.e., a decision that is deemed both legal and morally acceptable; we define morally or ethically acceptable purchasing practices as those that do not transgress the purchasing code of ethics of an institution.

The ethical oversight and scrutiny in the purchasing process potentially create stress for purchasing professionals (Ghere 2002). While past research has examined different facets of stress at the workplace such as role stress (Jaramillo et al. 2011) or moral stress (DeTienne et al. 2012), it hasn’t directly addressed ethics-related stress among purchasing professionals. The closest work to our line of inquiry is the research on moral stress, which has been defined in various ways, with most definitions circling around the idea that individuals seek to behave ethically but do not have the ability to take the steps necessary to do so (DeTienne et al. 2012). We submit that conceptualizations of role stress and moral stress are helpful, but ultimately inadequate for fully understanding ethics-related stress in purchasing. These stressors occur before decisions are made, and are mostly associated with the “weight of merely having to make such decisions” (Reynolds et al. 2012, p. 493); they capture the uncertainty of making a good decision. Rather, our focus is on the examination of post-decision effects felt by purchasing professionals; the apprehension caused by having taken a purchase decision, circumscribed by ethical expectations. Based on qualitative data, we conceptualize a major component of this post-decision effect to include the experience and resolution of ethics-related cognitive dissonance. Importantly, we examine this in the context of public sector purchasing, wherein we take into consideration the impact of multiple stakeholders (such as the media, government oversight committees, the publics, etc.).

Purchasing in the Public Sector

Public sector purchasing relates to aspects of the economy dealing with governmental services, such as military, police, public education, and healthcare. It includes purchasing by national, regional (i.e., state), and local governments, as well as by other publicly funded entities (IIA 2012). The process of public sector purchasing is characterized by three key aspects: (a) organizing bidding and awarding of contracts, (b) keeping transparency, and (c) maintaining oversight (e.g., Fleshman 2016; Ghere 2002; Hawkins et al. 2011; Raymond 2008). Once an institution decides on product specifications, open and fair competitive bidding is conducted, and the institution is expected to award the contract to the lowest reasonable bidder (e.g., Ghere 2002; Raymond 2008). Numerous laws and regulations govern the purchase of goods using governmental funds, which often constrain the public sector organization from utilizing the same purchasing tools that private sector organizations have at their disposal (Husted and Reinecke 2009). To show how much extra pressure from regulation and scrutiny the public sector purchasing function is subject to (compared to the private sector), we illustrate the key differences in the purchasing processes between the public and private sectors in Table 1.

Traditionally, the expectations of public sector institutions from their purchasing functions have centered on three things: (a) sourcing the best quality goods and services at the lowest possible costs (e.g., Lindskog et al. 2010; Raymond 2008), (b) keeping the process transparent (Fleshman 2016; Hawkins et al. 2011; Lindskog et al. 2010), and (c) documenting all the steps for an audit trail (e.g., Fleshman 2016). These expectations are usually couched in a code of ethics that purchasing professionals are expected to follow (e.g., Landeros and Plank 1996). These expectations often lead to ethical pressure on public sector purchasing professionals who would prefer to avoid public and media scrutiny, and maintain their reputation among their peers (Ghere 2002). The ubiquitous presence of this pressure (from regulatory controls, audits, public transparency, and media scrutiny) makes the public sector an ideal context for us to examine the apprehensions about always being ethically appropriate. To advance our theoretical understanding of this area, we utilize a phenomenological approach.

Method

A phenomenological approach is especially well suited to the topic of purchasing as it allows for researchers to understand how participants experience things and assign meaning to those experiences (Moustakas 1994). This “lived experience” (Creswell 2013) allows for a deep and thorough investigation of a phenomenon. This approach can be considered both pragmatic and pluralistic (Creswell and Clark 2007). This paper follows the systematic approach suggested by Strauss and Corbin (1998) where qualitative data are used to systematically create theory which explains actions, processes or interactions. Systematic approaches involve several steps in the data analysis process including open, axial, and selective coding (Creswell and Clark 2007). Open coding involves the researcher assessing the gathered data in an attempt to identify key categories as well as a central or “core” phenomenon. In our analysis, the core phenomenon which emerged is the concept of ethical purchasing dissonance. Following open coding, axial coding was then used to assess the types of categories surrounding the core phenomenon and the nature of their relationship to the core phenomenon. Strauss and Corbin (1998) identify the potential types of categories as causal conditions, strategies, intervening conditions and consequences. We mirror this strategy by inductively developing a conceptual framework for ethical purchasing dissonance through a visual model (Morrow and Smith 1995), utilizing both identified and emergent categories, and develop propositions about their inter-relationships (Creswell and Brown 1992; Creswell and Clark 2007).

Sampling and Interview Procedures

We collected interview data from 24 public sector purchasing professionals using theoretical sampling (Glaser and Strauss 1967). Theoretical sampling is a non-random sampling technique in which interview subjects are chosen for their expertise and ability to help generate theory about the phenomenon of interest (Creswell and Clark 2007). To facilitate our study, participants were chosen to sample a large number of both experienced and inexperienced purchasers (1.5–39 years of experience) across varied levels of responsibility (from a frontline buyer for a relatively small municipal department to a director of multi-million dollar purchasing function), varied purchasing organizations (state, city, medical centers, and universities), and varied regions (multiple states across the U.S.). Theoretical sampling as a technique has been used in multiple marketing studies (e.g., Kohli and Jaworski 1990; Malshe and Sohi 2009). Table 2 shows our participants demonstrate considerable diversity of experience in public sector purchasing.

Interviews were conducted both over the phone and in person and most lasted over an hour. All interviews were conducted as one-on-one depth interviews and were recorded with the permission of the participant for transcription purposes. All interviews followed a semi-structured format where participants were asked a series of questions about ethics, ethical dilemmas, anxiety, and public sector purchasing. As part of utilizing the emergent design, the interview process followed a flexible structure (Creswell and Poth 2017) to explore the phenomenon of interest as extensively as possible. Interviews were conducted until an adequate level of theoretical saturation was reached (Strauss and Corbin 1998).

Data Analysis

Several phases of data collection and analysis were conducted for this study. Data were collected from the field, analyzed, and then utilized to generate additional questions and interview topics for subsequent interviews (Creswell and Clark 2007). Data analysis was conducted using the Atlas.ti computer software package. In the open coding phase, we analyzed each interview transcript and created data codes and memos to identify key categories, identifying the central phenomenon of ethical purchasing dissonance. These categories were then utilized in the axial coding phase to identify the nature of each emergent category’s relationship to ethical purchasing dissonance. Since our goal was to enhance the conceptual understanding of ethics and employee purchasing behavior in the public sector, we utilized a pragmatic and pluralistic research approach (Creswell and Clark 2007) rather than pursue a completely positivistic or interpretive approach. Following axial coding, selective coding was conducted and combined with literature review to develop propositions and a conceptual model of ethical purchasing dissonance. In doing so, we (a) respond to scholarly calls for more qualitative research in business-to-business marketing (Weitz and Jap 1995), and (b) reveal antecedents and outcomes of ethical purchasing dissonance. Thus, our approach allows a synthesis of qualitative findings from the field with past research and theory (Burawoy 1991); similar methodological approaches have been used to examine purchasing issues (Ulaga and Eggert 2006) and the marketing function (Kohli and Jaworski 1990; Workman et al. 1998). To ensure data validity, we utilized both triangulation and member checking with research respondents. Triangulation includes identifying corroborating evidence from multiple sources (Creswell and Miller 2000). To ensure data triangulation, we randomly picked organizations where we collected data from purchasing professionals at different organizational levels. We also sought out purchasing professionals across a variety of public institutions including various state, municipal, healthcare, and university organizations. Major themes were compared across all the various purchasing positions to ensure robustness and validity. Member checking involved taking data and analyses back to study participants (Creswell and Miller 2000). To further inform validity, random member checking was conducted with a follow-up phone call to ensure that the themes fit what they had discussed during the interview.

In the following section, we present the findings that emerged from our analysis. We begin with a discussion of ethics in public sector purchasing and the development of ethical purchasing dissonance. Then we present antecedents to ethical purchasing dissonance, which include institutional, intrapersonal, and interpersonal factors. Finally, this section concludes with the consequences of ethical purchasing dissonance including anxiety and behavioral outcomes.

Findings

Ethics in Public Sector Purchasing

Public sector purchasing processes are unique in both the extent of regulation, and constant pressure placed on employees through regulatory controls, audits, and media scrutiny (see Table 1) (Ghere 2002; IIA 2012; Joyce 2016; Larson 2009; Smith 2017). This enhanced pressure can have a significant impact on public sector purchasing professionals, forcing them to be constantly aware of the ethical issues related to their jobs. Many of the public sector purchasing professionals in our study spoke of the need to frequently keep ethical checks as a salient part of their day-to-day decision making. They described ethics as important to maintaining fairness to the purchasing process and to their ability to do a good job:

It (ethics) needs to be something that is always on your mind, because if it’s not, you tend to make stupid mistakes, and there is no room for stupid mistakes in this business. - Senior Buyer, University N

The possibility of negative publicity for violating ethical norms was frequently cited as a major stress point by the respondents. Some purchasing professionals even viewed themselves in an expanded role as gatekeepers to the cause of maintaining ethical standards for their organizations:

Our view is that our job is to keep the (organization) out of the newspaper in a bad way, especially in the area of purchases. Any kind of negative judgment, or something uncovered that would have to do with spending the funds of the (organization) would be bad, would reflect on us. We sometimes feel we’re kind of the gatekeepers in that area. - Senior buyer, Medical Center X

Purchasing professionals also spoke of how a lack of fully understanding ethical issues impacted their jobs and consequently, stress levels, especially when starting their careers. It was often noted that a failure to properly cope with this increased stress could negatively affect their performance in the workplace, and possibly lead to being passed over for promotion. The following quotes illustrate these issues:

It’s like anybody starting a job; it is scary at first because you kind of wonder; can I handle it? Am I going to be able to handle all the bad things that go along with it? That was my big concern. I worried about bid protests, and if somebody went to the President, and the President came down to me, am I going to be able to handle all that? - Director of Purchasing, University N

If people aren’t able to handle their stress, are not able to handle their job very well, it becomes a performance issue. And so they tend to get less responsibility placed on them, and probably less chances for advancement. - Senior Buyer, University N

Thus, we found evidence of consciousness of ethical issues and the prevalence of ethics-related stress, confirming that public sector purchasing is an appropriate context to understand the mechanism responsible for ethics-related anxiety. It is critical to uncover this mechanism for two reasons. First, identifying the mechanism allows for its extent to be gauged, which would help deal with the damage it can potentially cause. Second, isolating it would help in identifying its antecedents and the nature of their impact. We uncovered a cognitive dissonance (Festinger 1957), a state of apprehension, that drew from the trepidation of appearing to be ethically questionable even when one’s intentions were ethical or legitimate; the apprehension was found to be rooted in uncertainty about violating some ethical boundary in public sector purchasing.

Ethical Purchasing Dissonance

Based on our qualitative analysis and a review of cognitive dissonance theory (Cooper and Fazio 1984; Festinger 1957), we conceptualize ethical purchasing dissonance as a psychologically uncomfortable state of arousal stemming from the presence of two factors i.e., (1) having to make effective purchasing decisions, and (2) staying true to an ethical code of conduct under regulatory and media scrutiny. Ethical purchasing dissonance (EPD)Footnote 2 is typically experienced after making purchasing decisions and can result from: (a) being unsure if some ethical boundaries were violated, and (b) concerns about unintended consequences of an ethical decision such as involuntarily giving the appearance or impression of ethical impropriety in the public-sector context.Footnote 3

Similar to an individual (consumer) making purchasing decisions, purchasing professionals may evaluate their decisions post hoc and feel dissonance. If these purchasing decisions are circumscribed by an ethical code of conduct (Maesschalck 2004; Matthews 2005), the dissonance takes an ethical dimension. Thus, our observations in the field led us to the cognitive dissonance theory, which was originally proposed by Festinger (1957) as when a person held two psychologically inconsistent “things” (p. 93) in mind resulting in a motivating, negative state of arousal and psychological discomfort. This initial explanation has been refined by Cooper and Fazio (1984) to include inconsistencies related to thoughts about unknown and potential undesirable consequences, with dissonance including arousal and discomfort; psychological discomfort occurring when attributions about the dissonance target (e.g., purchasing decision) were made internally. Cognitive dissonance is also suggested to include anticipated regret and feelings of apprehension (Oliver 1997).

In the quest for our conceptualization of EPD, our analysis indicated evidence for both sources of dissonance, i.e., being unsure of violating ethical boundaries, and imagining unintended consequences of giving impressions of ethical impropriety. First, respondents noted that sometimes the purchasing decisions they need to make are not always ethically clear cut; occasionally the threshold between right and wrong action isn’t obvious and the psychological burden of resolving the right course of action then falls on the individual’s inner resources:

Every eventuality is not in writing. And I know they try to make it that way, but still things come up sometimes that sometimes can go one way or the other. If something comes up to where you’re a little unclear about what the law is saying, you have to take from yourself, your own common sense, your own ethical and moral upbringing, and the rules and policies of your organization, and you have to put all that together to make decisions sometimes that are not just maybe black and white. - Assistant Director of Purchasing, University N

Second, dissonance can also be caused by imagining hypothetical scenarios where the purchasing decision that was taken is imagined to have an unintended consequence; this is the concept of looming vulnerability, which proposes that individuals view apprehension as an “anticipatory state” based on the perceived danger and use multiple pieces of information to appraise the severity, and the potentially increasing magnitude of a threat (Riskind et al. 2000). The act of generating a looming vulnerability perspective is seen as involving a mental simulation of both real and hypothetical events (Taylor and Pham 1996). Research on social cognition suggests that individuals continually create these mental scenarios with both simulated events and outcomes (Aspinwall and Taylor 1997; Fiske and Taylor 1991; Kahneman and Tversky 1973). In our context, looming vulnerability could stem from the pressure of oversight which may have the unintended consequence of creating psychological discomfort about appearing unethical while trying to ‘do the right thing.’ Often, just the appearance of being unethical, even when performing an ethical act, can be just as damaging as actual unethical behavior (Ghere 2002) (“You can end up on the front page of a newspaper for things where there was no wrong doing at all, it’s just a perception of wrong doing” - Director of Purchasing, University N).

Accordingly, EPD could stem from the divergence of two thought streams: (1) one’s intentions in the purchasing decision are ethical and legitimate, and (2) one’s concerns about mistakenly crossing an ethical boundary or ethical impression management are elevated. Respondents mentioned the awareness of this discord, and the preemptive steps sometimes taken to resolve it:

The appearance of impropriety is often just as damning as impropriety itself. Once you have put that appearance out, it is very difficult to prove that you were not participating in unethical behavior. So we have to take every step possible to make sure not only are we doing everything we are supposed to be doing, but that there is absolutely no appearance of impropriety as well. - Acting Administrator for Material Services Division, State A

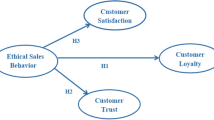

Thus, we identify EPD as a key mechanism that manifests in purchasing professionals. We inductively develop a conceptual framework to elucidate the antecedents and consequences of EPD (see Fig. 1).

Antecedents of Ethical Purchasing Dissonance

Our research questions were framed around understanding the apprehension associated with the real or perceived ethicality of purchasing actions. For instance, we probed: Can you describe how ethics and ethical considerations or concerns impact your duties as a purchasing professional? Do you feel nervousness about behaving—or appearing to behave ethically? What types of situations stress you out ethically? If you feel concerned about an ethical issue, what can you do to make yourself feel better? Our data analysis yielded three major themes on the antecedent side—institutional, intrapersonal, and interpersonal factorsFootnote 4—that impact the level of arousal and psychological discomfort in purchasing professionals. We find our emergent themes are consistent with or extend the extant literature on the purchasing function in particular (i.e., Gonzalez-Padron et al. 2008; Landeros and Plank 1996; Rudelius and Buchholz 1979), and the public sector in general (i.e., Ackroyd et al. 1989; Boyne 2002; Maxwell et al. 2004).

Institutional factors emerged as organizational conditions that impact the level of EPD experienced by purchasing professionals; these include (a) institutional ambiguity, (b) autonomy, and (c) audit pressure. Intrapersonal factors emerged as the second antecedent theme and capture different aspects of the purchasing professional’s perception of their beliefs and roles. Intrapersonal factors include: (a) perceived material risk, and (b) purchasing leadership role. Interpersonal factors emerged as aspects of the purchasing professional’s interaction with others in both their work and personal lives. Interpersonal factors include: (a) perceived social risk, and (b) perceived ethical leadership.

Institutional Antecedents of Ethical Purchasing Dissonance

Institutional factors are important predictors of behavior as they represent the structures and actions that an organization puts in place in response to social networks that require or pressure organizations to conform (Homburg et al. 1999). These factors take the form of rules, expectations, and habitual actions that organizations put into place to deal with the external pressures and provide the means by which activities and actions are pursued within an organization (Grewal and Dharwadkar 2002). Since a large part of cognitive dissonance has to do with the resolution of competing thoughts, these rules and expectations are especially important for purchasing professionals when dealing with ambiguous, high stakes decisions. Based on our phenomenological analysis, three institutional factors emerged as antecedents to EPD: institutional ambiguity, autonomy, and audit pressure.

Institutional Ambiguity

Institutional ambiguity refers to the extent of uncertainty and vagueness in (a) the purchasing process, (b) the characteristics of the purchase to be awarded, (c) purchasing roles, and (d) purchasing code of ethics of public sector institutions. Given that governmental agencies have rather broad discretion when determining the processes or procedures to apply to different purchases (Duvall et al. 2013), institutional ambiguity may differ widely among organizations. Our analysis confirms this as we unearthed considerable variance on clarity of the purchasing process across public sector organizations, and it became evident that not all organizations had clear guidelines and processes. It was also clear that institutional ambiguity has a large impact on EPD.

Ambiguity in Process

The process of public sector purchasing is characterized by three key aspects: (a) organizing bidding and awarding of contracts, (b) keeping transparency, and (c) maintaining oversight (i.e., IIA 2012; Lansing and Burkard 1991; Lennerfors 2007; NIGP 2013). Respondents in our study corroborated the basic tenets of the process that can be described as follows: A public sector institution decides on specifications of products or services that are required. This is followed by allowing vendors to bid with open and fair competition for the contract. The bids are submitted by a set date and evaluated on a pre-determined set of criteria. To a large extent, public sector institutions are expected to award the contract to the lowest reasonable bidder and the institution is allowed to negotiate the terms and conditions with the vendor (Ghere 2002; Lindskog et al. 2010; Raymond 2008). Transparency is a key requirement, since most of the information in the process is made public at some point in time. Finally, oversight or supervision of the process occurs at many levels, including vendors, with periodic peer and external audits (Fleshman 2016; IIA 2012; Smith 2017; Telgen et al. 2012).

Despite a fairly common rubric for purchasing, respondents reported variance in how different public sector institutions approach purchasing, with instances of potential ambiguity in purchasing processes. For example, the director of purchasing from state university L mentioned “judgment calls” on whether or not a vendor met bid requirements, sometimes leading to vendor clarifications which could be an acceptable action at some institutions but not at others (“… you have to make a judgment call on whether or not they met the requirements. You think they did, but can you go back for clarification? You can’t change the bid, but are you letting them change the bid because they clarified? So you have to stop and think, is this clarification, or is this adding to a bid? Can’t add to a bid. If they don’t meet the requirements, you have to go to the next vendor”).

While there is considerable emphasis and effort made towards making the process as objective as possible (“So you’re kind of always trying to make an objective assessment, and trying to make sure it’s objective and not subjective” - Director of Purchasing, University L), evaluation subjectivity was a common refrain amongst several purchasing professionals. It was well described by a respondent:

And now you’re telling someone (on the committee) here’s 10 points for this category, you will award this company anywhere from 0 to 10 points based on what you read and how well you think they did in that category. And it’s when you get into that subjectivity, that I think it introduces more of the possible ethical issues, where, is someone evaluating fairly because they’re being objective in their approach to the process, or do they have some type of connection; a friend who works for a company, do they have stock that they own in a company. Those are the things that aren’t always readily apparent. - Deputy Director, City G

The extent of ambiguity in the purchasing process was also felt to be a function of the size of the department or institution making the purchase. Larger purchasing units are likely to be more regimented and unequivocal in how each of the steps is documented and implemented (“I think there are some areas where this (unethical behavior slipping in) could happen, because a lot of departments are not as big as ours, and they don’t go through the purchasing process. It is not as regimented as we are” - Administrative Services and Budget Manager for Auxiliaries, University L). Compliance with transparency norms is seen as an antidote to ambiguity, with some respondents noting that posting the bid requests on the state website takes the abstruseness out of the process (“And they [bids] are posted on the state website, so that anybody in the world can apply. Because of that, we really are not put in the position of making decisions on who can or cannot bid” - Director of Purchasing, University L).

Ultimately ambiguity in process has the potential to increase EPD. For instance, not specifying upfront how product specifications should be evaluated increases the ambiguity in the process and likely exacerbates dissonance by increasing subjectivity; purchasing professionals are more likely to question their choices if the process was ambiguous. Additionally, any ethical loopholes in the process could get purchasing professionals worrying about giving the wrong impression. Clear cut guidelines, with objective criteria that is well defined, tends to reduce the apprehension (“But I think, in our case, since we do have such specific guidelines, it takes that stress away” - Administrative Services and Budget Manager for Auxiliaries, University L).

Ambiguity in Award Characteristics

A specific case of process ambiguity that was frequently referenced by our respondents was the lack of clarity in the specifications for a bid request. Public sector purchasing professionals are required to assess a variety of options to make purchases which best suit the goals of their organization for the best price possible. These organizational goals are often laid out in terms of the required attributes of the desired products or services, yet not all bid proposals cover every potential attribute of the product or service being purchased. As a respondent explained, the process can get complicated if you get away from the ‘sealed bid-lowest price’ objective:

I think subjectivity is in the more complicated procurement process. Because, the RFP (Request for Proposal) process itself is the more complicated process here. And that is grayer than a sealed bid, because we use sealed bids when we know what we want, and price is the only thing we’re interested in. We know what we want, we just want the cheapest one. It’s a faster track. But when you have a need, but you don’t know what the end result is, but you don’t know how to get there… so then it comes back down to … the expertise of the committee, and their background. - Senior Contracts Officer, University Q

Importantly, ambiguity in award characteristics could lead to vendor dissatisfaction which could delay the process (“…sometimes what happens then is, you don’t get anybody to bid on your product, and you have to keep going out and redoing it. You have to walk a fine line in building relationships with the community” - Administrative Services and Budget Manager for Auxiliaries, University L). Worse, it may force purchasing professionals into making a subjective choice, leading to dissatisfied vendors when the contract is awarded. This creates the potential for vendor challenges to subjective judgments, which can be problematic to defend. The following quote highlights this issue:

There is only, in some cases, just one award. Well then you have almost two dozen people who are unhappy because they didn’t get the business. And then you have to explain to them a little bit of the process, and why they didn’t get the business. For the most part it is pretty clean, because it comes back to cost, but in procurements where cost is not the driving factor it becomes more subjective. - Senior Contracts Officer, University Q

Thus lack of specificity in award characteristics creates the potential for EPD; given the subjective evaluations of the viability of a given bid, purchasing professionals could question if they made the decision that was right, fair, ethical, and non-controversial.

Ambiguity in Roles

We observed through our interviews that purchasing silos in the public sector are structured into roles, such as purchase director, purchase manager, or buyer. If the responsibilities are not clearly demarcated, it could lead to role ambiguity. Scholars have conceptualized role ambiguity as an uncertainty about job functions and responsibilities (Jaramillo et al. 2011) and a lack of information needed for an employee to adequately perform his or her role (Kahn et al. 1964; Miao and Evans 2007). Our data corroborate extant work on role ambiguity, which could arguably exacerbate tensions as employees get frustrated about not knowing how to proceed with critical tasks (Jaramillo et al. 2011; Kahn et al. 1964; Singh and Rhoads 1991). Purchasers talked about this effect in terms of overlapping roles creating ethical dilemmas: (“If you have the person who is developing the relationship, basically putting the specifications together, and then doing the contract, I mean they have total control over everything. That’s where I think you need more levels in there. So, it’s kind of like in financial auditing; so the same person isn’t doing everything” - Administrative Services and Budget Manager for Auxiliaries, University L). Consequently, any ambiguity in defining the purchasing roles could have an impact on the EPD experienced by purchasing professionals, given that ethical issues abound in boundary spanning roles (such as sales or purchasing) and it may not be possible to codify every single ethical situation that arises.

Other ways role ambiguity impacts EPD is when the functions and responsibilities of a purchasing professional are left unclear, the employee may lose confidence in the purchase decision that was taken; the apprehension could come from missing some important ethical guideline or stepping on someone’s toes with overlapping responsibilities (“Where do I go to find an answer for this? For the guidelines and the rules around it? And the anxiety becomes when you don’t know what you’re supposed to, you don’t have any clear guidelines. So what is the guideline, what am I going to-what is the closest thing, so that I could defend it?” - Director of Purchasing, University L). Certifications and training were referenced as solutions to reduce role ambiguity, as they tended to standardize functions and bring institutional legitimacy to purchasing roles (“Everybody in my operation is certified; they’re either certified public purchasing buyer, or certified public procurement manager, and in order to be certified (and that’s through the Universal Public Purchasing Certification Council), we had to go through training, education and experience criteria, and, pass some exams” - Director of Purchasing and Risk Management, City I).

Ambiguity in Code of Ethics

Codes of ethics are an important part of the purchasing process for all organizations to help ensure that purchasing professionals are behaving in transparent and ethical ways. Some institutions have created organizational codes of ethics that members can adhere to, and others follow the codes developed by professional organizations (i.e., CIPS 2007; NIGP 2013) (“We are members of the National Institute of Governmental Purchasing, and they have a code of ethics that we try to abide by, and also the Universal Public Purchasing Certification Council has a code of ethics that we try to abide by. So, I guess everything we do, we try to make sure that we are treating all vendors fairly in all of our dealings” - Director of Purchasing and Risk Management, City I). However, purchasing professionals also recognize that not all organizations have (or adhere to) a code of ethics. Some respondents reported a separation between legal compliance and maintaining ethical standards; where the former is necessary, the latter is often uncertain (“We have legal counsel, and we always want to make sure that what we do is compliant with law, whether that’s local, state or federal. But there are things that can come up that are somewhat gray. It’s not clear if there is an ethical violation or not” - Deputy Director, City G).

The presence of a well-documented and unambiguous code of ethics implies that there are clear guidelines, specific to the purchasing process, on what are considered ethically acceptable practices and what are not. Codification of ethics provides consistency and unswerving guidelines that help reduce ambiguity. Absence of a detailed code of ethics (or lack of serious communication or enforcement of the code) is likely to lead to inconsistent ethical decision making (Schwartz 2001), and subsequent dissonance. It was frequently noted that it was difficult to foresee and code all possible ethical situations. Thus, there were challenges reported in maintaining ethical standards in light of unforeseen circumstances; as were well explained by a purchasing director:

That is probably something that every purchasing person in a public sector will encounter at some point if they are in the business for more than a few years. I have had numerous situations where you’re invited to play golf, you’re invited to go to a baseball game and sit in the luxury box, and you’re invited to take a trip. And, sometimes you have to split hairs. Sometimes it is appropriate to take a trip to a factory to see how something is manufactured, so that you know the quality that you’re looking for is in fact demonstrated. Other times, a trip to the factory is simply a way of wining and dining you in another part of the country, and to influence you in ways that are not ethical. - Director of Purchasing, Public School M.

Ambiguity in the code of ethics exacerbates EPD in a very direct fashion—it creates doubts in the minds of purchasing professionals regarding the ethicality (or the visibility of ethicality) of their purchasing decisions. (“You can always debate whether that was the best decision or not. So it’s not always a cut and dry ethical matter, it’s sometimes just a decision you’ve made based on a practice, or a situation that the media may disagree with, or the community may disagree with, and then that gets of course skewed” - Deputy Director, City G). And for the purchasing professional, ethical ambiguity is a psychologically uncomfortable place to be (“Well, because, that indecision causes, is stressful, when there’s a lack of clarity. You know, and sometimes, what’s a nominal (gift value)?” - Director of Procurement, State B) that was reported to be occasionally resolved via erring on the side of caution (“and then I would err on the side of saying, it’s not worth, whatever it is. If you can’t explain it in a couple of sentences where people think it’s going to make sense, then you probably shouldn’t do it” - Director of Purchasing and Risk Management, City I).

Thus, overall, we propose that greater institutional ambiguity (comprising vagueness in purchasing process, award characteristics, roles, and code of ethics) is likely to exacerbate EPD. If process, awards, roles, and code are ambiguous and undecided, then it is likely to (a) increase the fear of unknowingly having done something that makes one appear to be unethical, (b) introduce subjective judgment, which could be challenged (“There’s not always a hard and fast rule for everything. So you do have to introduce your judgment and your analytical skills when you decide how to proceed in something. And that can be called into question.” - Deputy Director, City G), and thus create cognitive dissonance by reducing one’s confidence in the purchase, and (c) lack a clear demarcation of roles and responsibilities, making purchasing professionals less sure of their functions and powers. The relationship between institutional ambiguity and EPD could be particularly strong in the absence (or inadequacy) of a documented code of ethics; purchasing executives are likely to experience greater dissonance about ethical decisions if they are unsure of where the organization stands on an issue. Hence, we propose,

P1: Greater institutional ambiguity (in purchasing processes, award characteristics, roles, and code of ethics) will be associated with higher levels of ethical purchasing dissonance.

Autonomy

The independence and freedom of action available to a purchasing professional (i.e., autonomy) varies depending on the size and structure of the organization, as well as the origin of the funds which are used (e.g., federal, state, or municipal). Public sector organizations allow varying levels of autonomy to purchasing professionals depending on the size and type of purchases. Purchasing professionals may also operate in a centralized or decentralized purchasing organization where their abilities and actions are monitored differentially. Respondents spoke to these differences and showed variance in the level of autonomy among organizations, often viewed in terms of the level of checks and balances in place. For example, a director noted there was a high level of checks and balances in his/her organization that limit autonomy:

We also have checks and balance. For example, I sign purchase orders and I sign bid issuances. So the people that put them together were not left without checks and balances. And the same as other things, I have checks and balances that go up the chain. - Director of Purchasing, University L

However, another respondent indicated that his/her department did not have a lot of oversight given the size of the department (“we don’t really have a lot of oversight going on right now with two people. We’re trying to monitor all the departments and what they’re doing, but there’s really not enough staffing” - Buyer 2, City D).

Autonomy in public sector purchasing comes with both benefits and drawbacks for public sector purchasing professionals. Employees who are allowed to operate freely are able to make decisions and judgment calls, however, the ultimate culpability for mistakes or problems lies with them if there is no one else in the chain of command. As one respondent indicated, having checks and balances, or limits to autonomy, provide safeguards against having to make ethical choices (“we have enough checks and balances that you really are not put in a position to having to make ethical choices” - Buyer 2, City D) which can reduce that culpability. Another respondent, when asked if a purchaser wanted to behave unethically, indicated that autonomy would be key:

I think they would have to be in control of everything, from the start of deciding I need to purchase this item, this is what I need. And then they would be in charge of all aspects, from writing the specs, to doing the solicitation, to getting the contract set up, to paying the invoices. - Administrative Services and Budget Manager for Auxiliaries, University L

Thus, it is evident that autonomy can open the door to both unethical behavior, and the appearance of impropriety, as other individuals may see the level of autonomy and question the purchaser’s actions. This was corroborated by another respondent who noted that lack of checks and balances can allow temptation to enter into the decision making of purchasing professionals and “open the door” for having to make the “right or wrong” decision (“…the same person who issues the PO is the one who approves the invoices. So if they’re having fiscal problems, they may be tempted to do embezzlement kind of activities, because they’re in the same cycle of order, receive and pay, without that being in checks and balances. So basically anything that opens the door for you to make the decision of right and wrong” - Director of Purchasing, University L).

Autonomy in public sector purchasing has the potential to increase EPD given that it is may increase the fear of unknowingly giving the impression of ethical impropriety. Employees who are concerned with maintaining an ethical appearance are likely to feel uncomfortable if they are in a highly autonomous situation where they could be seen as being culpable for negative outcomes. In addition, these employees may fear that others will assume they are acting unethically simply given the high level of control they have over the process. If an employee is the sole person responsible for a purchase which is perceived as unethical, they are likely to receive all of the blame for making a poor decision. This increased risk of culpability leads to increases in EPD for purchasing professionals in highly autonomous situations. Conversely, just as reducing autonomy can increase nervousness in an employee who is behaving unethically, reducing autonomy could reduce nervousness or EPD in employees who are trying to make the right decisions. Reducing autonomy (providing checks and balances) can also make it more difficult for any single individual to be blamed for decisions and negative outcomes (“But we have the program in place where, your transactions have to be approved by another. I guess if there was a group of people, conspiring to do something, they’d be more likely to get away with it than an individual” - Purchasing Manager, City T). We therefore propose:

P2: Increases in purchasing professional autonomy will be associated with increases in ethical purchasing dissonance.

Audit Pressure

As a result of the discovery of poor accounting practices and their contribution to fiscal crises in several large U.S. cities in the 1970s (Copley 1991; Deis and Guiroux 1992), the use of periodic audits in the public sector has become a critical source of oversight (IIA 2012). Financial audits involve investigating the audit trail by examining the relevant documents, and the accuracy and reconciliation of amounts contained on financial statements (Singleton and Singleton 2007). Any deficiencies in audit quality (DeAngelo 1981; Deis and Guiroux 1992) impact the level of confidence the public has in the governance of the public sector and can trigger further investigation, media scrutiny, and public outrage.

Public sector purchasing professionals reported multiple types of audits including peer audits done by either co-workers or peer institutions, formal audits required by state or federal law, formal audits due to suspicion of wrongdoing, routine organizational audits, and impromptu organizational audits. Purchasing professionals noted:

Each procurement you do has to have the paperwork that goes with it, and it is its own unique file, and it sometimes has a really long life, and is constantly being looked at. Every place I’ve worked in the public sector there are multiple auditors that come through. Usually each from a different perspective, looking at something specifically, and they are pulling that file. And it’s the same way here. There are lots of hands that go through the files. Lots of hands. - Senior Contracts Officer, University Q

The standpoint - that basically everything we do is potentially visible to anyone, the general public, with the exception of those confidential materials. We also are audited, both internal and external. - Associate Director and Contracts Manager, University Q

Given the importance of audits and the constant scrutiny that often results, audits represent the cornerstone of ethical conduct for purchasing professionals. Audits return an explicit certification for running a transparent and ethical operation. As such, audits may lead to feelings of “audit pressure,” the feeling that someone is always watching:

We remind our folks that your behavior inside and outside of these walls is, well, we all live in a fishbowl, and that’s the reality of public procurement. We need to be mindful that people are always watching. - Deputy Director, City G

While audits are to be expected, purchasers spoke of them as being both stressful and sometimes hard to deal with—even if they felt they had made the correct purchasing decision. One manager spoke of an audit which was flagged at the federal level because the auditor didn’t accept or ignored some of the materials they had submitted.

Ultimately we got it resolved, but it created a lot of stress for the contract officer, because they felt like they couldn’t get factual information into the audit. And that was a frustration that, you know, you don’t have control over the audits. It’s just like the media. They come in and they look at information, and hopefully you have an auditor who is open to explanation or clarification, but sometimes they just purely look at the record. - Deputy Director, City G

Because audits are a consistent periodic reality for the public sector, impending audits have the potential to trigger EPD. Employees who face a large number of audits will be more vulnerable to potential mistakes and will know that their decision will be reviewed and carry potential risks. Hence we propose:

P3: Increases in audit pressure will be associated with increases in ethical purchasing dissonance.

Intrapersonal Antecedents of Ethical Purchasing Dissonance

The second antecedent theme that emerged from our analysis comprised intrapersonal factors; these include perceived material risk and purchasing leadership role. These factors represent the purchasing professional’s perception of their own self, their propensity to be alarmed by risk, and how their place in the purchasing hierarchy affects them. Given that these factors relate to an individual’s self-awareness and personal experiences, they can have a profound impact on EPD.

Perceived Material Risk

Public sector purchasing professionals who violate their organization’s code of ethics are open to a wide variety of materially relevant risks (such as legal and financial risks) because of their actions. Our respondents reported a deep awareness of such material consequences which could include employment termination (“You behave unethically, you’re going to lose your job” - Associate Director and Contracts Manager, University Q; “We have had people use procurement cards in inappropriate ways, for personal purchases and things like that. But we do audit for that, and people have been fired for doing that” - Senior Buyer, Medical Center X). The ramifications could be both professional and legal, and it was noted that the degree of punishment is usually commensurate to the severity of the violation, taking into account the employee’s experience and awareness of the violation:

Depending on the level, [the punishment] would depend on the severity of the action. I mean they could go from, don’t ever do it again, to a verbal reprimand, to a written reprimand, to a leave of absence without pay, to possibly termination, possibly legal action, you know. Depends on what it was and how innocent was it. You know how inexperienced is this person? Is it something they should’ve known? You know, it’s a topic that gets discussed a lot, and I guess I wouldn’t have a lot a sympathy for the person. - Commodity Assignments Manager, Medical Center X

Interestingly, an awareness of material consequences for unethical actions also appeared to impact the mental state of employees who behave ethically and do not transgress their organizational code of ethics. It was well understood that it isn’t enough just to do the right thing; one has to ensure, at all times, that no wrong impressions are given. Appearances of transgressions were cited as being equally risky:

Well the appearance, under the state code, makes you just as guilty as the real thing. If you’re found guilty of an ethical violation, you can certainly forfeit your employment. And I believe the code…well, I’m not an attorney, but I think, depending on the type of ethical violation, you can be convicted of some sort of a misdemeanor. - Associate Director and Contracts Manager, University Q

We argue that increases in perceived material risk are likely to aggravate EPD. Codes of ethics play a dual role in highlighting both the recommended guidelines and potential punishments for disobedience to the code. It serves as both a “shield” (providing guidelines) to help employees guard against unethical actions, and a “club” (increasing visibility) for management to ensure ethical behavior (Schwartz 2001, p. 255). Nevertheless, an unintended consequence of using the code as a “club” is highlighting and underscoring potential material risks; thereby raising the stakes for the purchasing professionals to remain in the clear. Thus, when the stakes are high (e.g., any real or construed violation could result in serious legal and employment damage), purchasing professionals are likely to experience greater psychological distress either being unsure if some ethical boundaries were violated, or fearing the worst in terms of giving the impression of ethical impropriety. Hence, we propose:

P4: Greater perceived material risk related to unethical purchasing practices will be associated with higher levels of ethical purchasing dissonance.

Purchasing Leadership Role

Purchasing leadership role refers to assuming a leadership role in administering the purchasing process, which is typically accompanied by expanded responsibilities and higher authority. Several respondents reported that a leadership role in public sector purchasing comes with the possibility of witnessing more instances of ethically charged decisions, thus creating added potential for EPD. A leadership role also requires taking responsibility for the behavior of the purchasing team and escalates the pressure to monitor and control for ethical compliance by the employees. This includes situations such as making judgment calls on individual purchases and buffering political pressure from elected officials, as was noted by a respondent:

I’d say probably the higher up you go, I’ll use our department as the example, certainly our director and then probably next to our director, myself, deal the most with the stress. Our role, because of where we are in the organization, we’re able to buffer much of the pressure that we might get from the staff. So I don’t facilitate processes directly, staff does. And for our director and myself, if there are pressures either directly from the politicians or from the organizational executives, we’re able to be that buffer. - Deputy Director, City G

Another by-product of increased leadership responsibilities in purchasing is the moral hazard situation that may arise for the employee in the role, i.e., greater concentration of purchasing responsibilities in one role could lead to reduced checks and balances in the process. It leads to an elevated probability of giving out inappropriate appearances as decisions made by subordinates will be deemed their responsibility. It was also felt that leadership brings an isolated position, with no support system to discuss critical decisions, lack of which could cause psychological distress:

I would think that if I was in public [sector] purchasing and I suddenly got put into like a city position, which notoriously does not have a lot of depth and breadth to it, that, you’re kind of on your own. And then you’ve got the city council that you’ve got to report to, and the city controller and so forth. And then you’ve got the public scrutiny. But you really don’t have a support system for making the decisions. I think that would be hard. - Buyer 2, City D

Overall, the purchasing leadership role is an exacerbating force that would heighten EPD, as it makes the purchasing professionals more watchful and self-conscious of their actions. Assuming a leadership role brings greater visibility, so appropriate appearances become ever more important. There is higher potential for political pressure from above given the proximity of the leadership role to the top management; and a concentration of responsibilities and authority might erode the necessary support system and increase suspicion. Thus,

P5: Higher responsibility levels in a purchasing leadership role will be associated with increases in ethical purchasing dissonance.

Interpersonal Antecedents of Ethical Purchasing Dissonance

The third antecedent theme that emerged from our analysis comprised interpersonal factors; these include perceived social risk and perceived ethical leadership. Interpersonal factors capture aspects of the purchasing professional’s interactions with others at work and in their personal lives. These factors may have a strong impact on EPD due to the relative support or pressure that is received through those relationships regarding ethical decision making.

Perceived Social Risk

In addition to perceived material risks, ethically questionable behaviors are accompanied by social risks that may damage a purchasing professional’s reputation professionally and communally. In the public sector, ethics investigations are often reported on by the media, and are damaging to the organization’s reputation, regardless of wrongdoing (Ghere 2002). Our respondents exhibited profound mindfulness related to social risk and noted that it remains embedded in their minds as they make ethics-related decisions (“A lot of it is just personal reputation, the risk to that is really the strongest thing that keeps people from making choices” - Director of Purchasing, University L; “Was it really worth it to go to jail? Was it really worth it for your family’s name to be dragged through the mud? Is it really worth your retirement?” - Purchasing Agent, City C).

Reputation theory proposes that people continually monitor both their own reputation and the reputation of others (Bromley 1993; Emler 1990), and this monitoring gives rise to reputation-related beliefs (Fishbein and Ajzen 1975; Nisbett and Ross 1980). Our respondents corroborated this and noted that regardless of their intention to behave ethically or not, purchasing professionals are always subject to the approval of their co-workers and vendors. Thus, reputation is seen as an asset for purchasing professionals which enables them to do their jobs effectively, while a loss of reputation can create significant problems. Respondents spoke of the criticality of reputation:

Your reputation is one of the most valuable things you possess. In a position of leadership, especially in procurement, you are asked to make decisions, and often times you are asked to make judgment calls. The laws and the rules guide you, but they don’t address every situation. And that is why having a reputation of being an ethical person, and honestly just having the character of being an ethical person, helps you. - Director of Procurement, State B

Other respondents noted the irreversibility effect of reputation loss, i.e., it is hard to come back from a tarnished reputation and how bad reputation follows you around:

If you lose your reputation, then basically everything you do is looked at - well that just went to so and so’s brother-in-law or so and so shipped it to business that way. I think when that happens, then you lose - the public thinks you are wasting money, cronyism and some other things. - Director of Purchasing and Risk Management, City I

The risk of social stigma is also used as a deterrent by purchasing professionals to resist any pressure from higher echelons for shepherding ethically questionable actions (“I actually try and collect horror stories, and put the fear into upper management and say, ‘this might not be a lot a dollars, but it looks really bad on the front page of the newspaper” - Buyer 2, City D) or to warn lower levels in the purchasing department of the negative consequences (“When I’m talking to department people that are contacting me and arguing ethical issues, of the… how is this going to look on the front page of the newspaper. How are you going to feel explaining yourself to a news camera? Do you think that you can make this sound good, or do you think that they can make it sound bad?” - Buyer 2, City D).

Social risk, such as potential reputational damage, can also be triggered by situations where the individual is perceived to behave unethically, regardless of their actual behavior. This could include accepting meal invitations by current or potential vendors (even though the purchasing professional pays his/her own way) or more extreme cases of taking trips with a vendor. The risk is directly related to the perceived appearance of impropriety that could affect the public sector purchasing professional’s status as an ethical person. Threats to an employee’s reputation have been found to be related to job stress (Doby and Caplan 1995), and threats to an individual’s reputation are also seen as threatening self-esteem (Eden 1990; Rosenthal 1985). Increases in perceived risk have been found to be positively related to a state of apprehension (Schaninger 1976). Hence, we propose a positive effect of perceived social risk on EPD, given the importance of reputation to a purchasing professional’s job performance:

P6: Greater perceived social risk related to unethical purchasing practices will be associated with higher levels of ethical purchasing dissonance.

Perceived Ethical Leadership

Perceived ethical leadership refers to the perceptions of the extent to which supervisors demonstrate “normatively appropriate conduct” through their personal actions and relationships, and then promote that conduct to purchasing professionals (Schwepker 2015, p. 300). The importance of leadership on ethics in the workplace is well established in both the management and ethics literatures (i.e., Hawkins et al. 2011; Schwepker 2015; Selart and Johansen 2011). Purchasing professionals in our study exhibited understanding of the public nature of their decisions and the potential scrutiny that may come with any given purchase, and often felt the pressure when leadership did not support them (“We try to follow the ethical guidelines of our purchasing organizations, and the most stress comes when we are not backed up by administration” - Senior Buyer, University N).

Leadership can influence the decisions made by purchasing professionals in several important ways. Leaders may behave opportunistically, supporting and promoting the use of practices that take advantage of supplier relationships (Hawkins et al. 2011). Leaders may intentionally deflect accountability for (or willfully ignore) ethical issues leading to employees who withhold information that superiors are not likely to want to hear (Hawkins et al. 2011). Leaders who feel stressed (through pressures of cost reductions or organizational restructures) may push that stress to purchasing professionals who then feel pressure to perform unethically or illegally (Selart and Johansen 2011).

Given the importance of leadership’s impact on purchasing professionals’ decision making, we believe that perceived ethical leadership plays a critical role in EPD. Respondents spoke of the need for a supportive environment that provides clear rules and expectations from the top (“…when the rules are spelled out from the top that this is how we do business, and we do business in an ethical manner. Then it’s a lot more comfortable to work for an organization where that’s spelled out and that’s the expectation, as opposed to one where it’s not” - Director of Purchasing and Risk Management, City I). However, respondents also noted that sometimes leadership follow their own set of rules or interpret the rules in their own ways:

When you’ve got good leadership, and they set a clear example and, they’re not doing one thing and then telling you to do something else. When that message becomes mixed, that’s problematic. Some people say wow, am I supposed to do what the rules say, or am I supposed to do what I see other people doing? So if the message isn’t clear, or you’ve got people that follow their own interpretations of it, that’s problematic. I think there needs to be one set of rules and everybody follows them. - Director of Purchasing and Risk Management, City I.

Other respondents felt that leadership had no interest in following the rules at all:

I consider myself very ethical, I follow the rules, and I was in charge of purchasing, and a director was hired from another state, and he just wasn’t all that interested in following the rules. And to know that I’m bound by law, and to have someone directing me to do things that I know aren’t ethical. I mean, basically I left. I mean that’s super high stress. - Senior Contracts Officer, University Q.

When leadership either does not set clear expectations or interprets the rules in a different way, this can lead to dissonance for the employees. Respondents spoke of the pressure they felt from leadership to make a certain decision. Many respondents felt they would not have a choice in making that decision and that they would have to follow their leader’s lead:

If the person who’s making the purchases reports directly to the person who’s telling them to make them, and maybe advising them to do things that they don’t really want to do. But because they are their boss, they don’t have a choice. They don’t feel as they have a choice but to do it. - Director of Purchasing, University L

If you worked for leadership that came to you and said hey, I know this isn’t right, but I want you to do this anyway, your job depends on it kind of thing, that’d be pretty stressful. - Director of Purchasing and Risk Management, City I

Another respondent noted the stress that comes from “being manipulated” by someone in leadership (“that’s where I see the stress is, your procurement officer who feels like they’re being manipulated by someone who wields a lot more authority in their organization” - Director of Procurement, State B). This pressure to bend the rules or make certain decisions can lead to an internal struggle or EPD (“…I’m doing the wrong thing but it’s not my fault because I was told to do it. So, they’re dealing with this guilt, dealing with these feelings of intimidation, worrying about getting personally in trouble, worrying about losing their jobs” - Director of Procurement, State B).

Overall, perceived ethical leadership can strongly influence a purchasing professional’s EPD. When leaders are perceived to have a high level of ethical leadership, they are seen to protect their employees from opportunistic behavior or other stressors that lead to unethical behavior. In such a climate, employees are supported and feel that the leader has their back. In addition, high perceived ethical leadership comes with clear expectations and rules that employees can follow, resulting in lower levels of EPD as the employee feels more confident in his/her decisions and less fearful of being seen as unethical. Conversely, when perceived ethical leadership is low, the purchasing professional may be afraid the leadership will push unethical behavior on them by pointing fingers or pressuring them into unethical acts; the expectations and rules could be unclear and interpreted in a variety of ways. This will lead to a higher level of EPD as purchasing professionals become unsure of decisions. Hence:

P7: Increases in perceptions of the ethicality of leadership are associated with decreases in ethical purchasing dissonance.

Consequences of Ethical Purchasing Dissonance

Our data revealed some interesting outcomes of EPD as they relate to the experience in purchasing. From our analysis it was evident that dissonance has the potential to exacerbate anxietyFootnote 5 in individuals, which corroborates the existing literature wherein cognitive dissonance was found to result in increased stress and reduced job satisfaction (Viswesvaran et al. 1998). Similarly, the degree of cognitive dissonance following a purchase decision was found to impact state anxiety in consumers (Menasco and Hawkins 1978). From a psychological perspective, anxiety often leads to some sort of adaptive behavior (Fry 1969) in an effort to reduce the anxiety towards a feared outcome (Stampfl 1991). We found similar instances of anxiety reduction behaviors in our data. Given the dire employment and reputation-related consequences, purchasing professionals often utilized the following three behaviors to keep their ethics record (and appearances) intact: (a) documentation, (b) approval seeking, and (c) external support. First, our respondents spoke of the need to document so that the logic of taking a decision in a certain way is chronicled appropriately. The following quotes illustrate this need:

So, I think we are kind of always in cover-your-behind mode basically. You always want to make sure you’ve got email to backup something that you are doing. And I think that we tend to do a whole lot of overkill as far as documenting why we’re doing what we’re doing, printing out an email to show this is why I did this, because so and so told me to. So I think we do a whole lot of overkill. - Principal Contracts Officer, City G

I’m compulsive about documentation, and I encourage my staff to be that way. I want to be able to pick up their folders and understand why they did something. If somebody comes to me and says look at this; I want to be able to understand why they did what they did, without even talking to them. - Senior Contracts Officer, University Q

Respondents also indicated that detailed documentation with logged reasoning, alleviates anxiety during audit time. For example, one respondent noted:

I don’t worry about audits, because I think my files are pretty complete, and I try to make sure I have done everything that I’m supposed to and included all the reasoning. And for the large dollar purchases, everything goes before my supervisor for approval. So, not only are my eyes looking at it, but there are other sets of eyes looking at it. - Principal Contracts Officer, City G

Second, respondents spoke of seeking approval, particularly from their supervisors, in order to reduce anxiety. When purchasing professionals feel the pressure of ethical decisions, they sometimes take steps to ensure that other people were brought in to give their approval on decisions that make them uncomfortable. They see this as a way of reducing the stress by reducing the risk of the ethical decision. This behavior ultimately leads to a reduction in both EPD and anxiety:

You know, probably each person has their own comfort level and, they may feel comfortable handling things on their own. I think you just kind of learn when something is something that you can handle yourself, versus I’d better check with my boss. - Principal Contracts Officer, City G.

Third, respondents noted that seeking help internally was important, but they could also seek external aid outside of their organization to potentially help justify a decision:

As a state agency, we’ve got the state regs, we’ve got the state rules, we’ve got other state agencies, and we’ve got a network of associations, National Association of [concealed]. So we have, a decent network to help mitigate the anxiety. - Director of Purchasing, University L.

Thus, our data corroborate the literature on the outcomes of cognitive dissonance (Menasco and Hawkins 1978), and we propose that increases in EPD will be associated with increases in anxiety; additionally, given the strong impetus to alleviate anxiety, purchasing professionals in the public sector will pursue anxiety reduction behaviors. Hence, we propose:

P8: Increases in ethical purchasing dissonance will be associated with increases in anxiety and anxiety reduction behaviors.

Discussion

We make four specific contributions with this study. First, we identify and conceptualize EPD, and thus expand our understanding of how purchasing professionals experience ethical decision-making under scrutiny. We conclude that EPD, which is typically experienced post-purchase, is a result of either uncertainty about violating ethical boundaries, or concerns about involuntarily giving the appearance of ethical impropriety. Second, we contribute an inductively derived antecedent model that identifies three categories of antecedents to EPD (institutional, intrapersonal, and interpersonal factors). Third, based on our phenomenological analysis, we outline an inventory of propositions for the antecedents and outcomes of EPD. Finally, our study examines a hitherto underexplored context of ethics in public sector purchasing, characterized by high regulatory, public, and media scrutiny, and thus adds new insights to business-to-business purchasing ethics.

Theoretically, we contribute to three streams of literature: (a) cognitive dissonance (Cooper and Fazio 1984; Festinger 1957), (b) business-to-business purchasing ethics (Cooper et al. 2000; Landeros and Plank 1996; Saini 2010), and (c) public sector purchasing (Raymond 2008; Telgen et al. 2012). First, by conceptualizing EPD, we extend the literature on cognitive dissonance beyond the realm of the individual consumer (Oliver 1997) into business-to-business purchasing. Our results underscore noteworthy outcomes of EPD; behaving ethically in purchasing roles was seen as “stressful” and anxiety inducing by our respondents, and EPD helps unpack how that anxiety and stress is generated. Cognitive dissonance theory suggests that there may be a link between cognitive dissonance and state anxiety (Menasco and Hawkins 1978), and we find similar results here in the ethics context; also in line with past research, we observe that in the presence of cognitive dissonance individuals are motivated to reduce dissonance (Elliot and Devine 1994). Employees with high levels of EPD are motivated to resolve this dissonance through a variety of anxiety reduction behaviors such as documentation, approval seeking, and external support. Past work has also suggested that individuals may have dissonance thresholds (Oliver 2014); identifying if these thresholds exist and how they influence purchasing professionals could help supervisors distinguish between high EPD and low EPD purchasing tasks.