Abstract

As studies continue to accumulate on leader humility, it has become clear that humility (one of the moral virtues) in a leader is largely beneficial to his or her followers. While the majority of the empirical research on this topic has demonstrated the positive effects of leader humility, this study challenges that consensus by arguing that a leader’s humble behavior can have contradictory outcomes in followers’ voice behavior. Drawing on attachment theory, we develop a model which takes into account the ways in which leader humility influences the seemingly contradictory voice behavior of followers, i.e., inducing challenging voice (promoting the flexibility toward changes), and defensive voice (showing the persistence toward changes) depending on the followers’ sense of security as reflected by feeling trusted (sensing the leaders’ confidence in them) and self-efficacy for voice (sense of self-confidence). The results of this empirical study confirm that leader humility influences followers’ voice in a contradictory way through their sense of security.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Humility—one of the moral virtues—has been shown to be more essential than previously thought for those who lead and have authority in organizations. Humility is useful for leaders seeking to solve complex business problems in tandem with their followers and can be a key determinant in motivating followers to engage in exploratory behaviors (e.g., voice) (Owens and Hekman 2012; Solomon 1992). Unlike many heroic and dominant leadership styles, in addition to other-oriented behaviors (e.g., appreciating and recognizing others) humble leaders also show vulnerability, such as accepting his/her limitations and mistakes, enabling leader–follower role reversals, displaying teachability, and accepting and encouraging critical feedback, which may affect followers’ behavior in positive and/or negative ways (Morris et al. 2005; Owens and Hekman 2012). Regardless of humble leaders’ vulnerability, thus far, there has been every indication that leader humility predicts clear-cut, positive follower behavior (Argandona 2015; Owens et al. 2013; Rego et al. 2017; Rego and Simpson 2018). In this research, we explore whether these non-heroic humble behaviors impact followers’ behavior in other than uniform, positive ways.

Moreover, to respond to the pace of change in our current hyper-competitive and diverse business environment, employees need a number of mutually contradictory skills (Lewis 2000; Owens et al. 2015). Related to this, research suggests there is a seemingly contradictory effect: that while change is inherent to an organizations’ efficiency, too much change tends to be detrimental (Amason 1996; Lewis 2000). This shows the importance of striking a balance between change and stability. For example, there may be times when employees’ voices, defined as “the expression of challenging but constructive concerns, opinions, or suggestions about work-related issues” (Janssen and Gao 2015, p. 1854), express desire for changes in the organization’s operations (promoting/seeking flexibility toward changes), although at the same time they may protest changes in operations (showing persistence toward changes) to maintain the stability of the organization or self (Amason 1996). This shows that individuals can exhibit seemingly contradictory behaviors, demonstrating that contradictory behaviors need not be on different ends of the spectrum, but can co-exist (Owens et al. 2015). In further investigations along this line, research in leader humility has revealed that leaders can be both narcissistic and humble, and these two qualities may work together to increase positive outcomes (Owens et al. 2015). Despite leaders’ dual characteristics (humility–narcissism) working together to benefit leadership effectiveness, scant research in this realm has questioned or even examined whether more humble leadership that includes leaders’ vulnerability may be associated with more contradictory outcomes in followers’ behaviors. Given the importance of followers’ upward communication in the success of contemporary organizations (Detert and Edmondson 2011), we conceptualize such contradictory voice outcomes as challenging voice—advocating for change—and defensive voice—stubbornness regarding the change. With this in mind, we examine whether engaging in humble leader behaviors can cause followers to engage in contradictory voice behaviors and, if so, what the mechanisms are.

Toward this end, we adopt attachment theory (Bowlby 1969/1982), as it can explain how the individuals’ (e.g., children’s or followers’) perception of support from their caregivers (e.g., parents or leaders) influences their exploratory tendencies, such as novelty seeking and challenging their environment, in ways which parallel their voice behaviors (Van Dyne and LePine 1998a). Studies have also suggested that the leader–follower relationship is analogous to parent–child dynamics in terms of the parent/leader showing the correct path and providing nurturing (Popper and Mayseless 2003; Wu and Parker 2014). As leadership plays a vital role in providing a secure base support for followers, humble leaders shape how their followers view themselves, others, and their willingness to embrace new ideas/information that promotes cooperative relationships, safety, and the formation of a proactive workplace environment (Owens et al. 2013). Even though it is known that humble leaders provide a secure base support, it is less clear how followers perceive that support. Does a humble leader’s secure base support impact the follower’s sense of security, subsequently leading to increase in voice behavior? To understand this connection, we operationalise followers’ sense of security through self-efficacy for voice (followers’ sense of self-confidence) and their feeling of being trusted (followers’ sense that their leaders have confidence in them), “the perception that another party is willing to accept vulnerability by engaging in risk-taking” (Baer et al. 2015, p. 1640). Self-efficacy for voice and feelings of being trusted map onto the “can do” and “safe to” motivational states, respectively. These are identified as key motivations that drive voice behavior (Brower et al. 2009; Detert and Edmondson 2011; Parker et al. 2010).

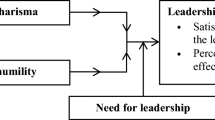

Although previous research has provided valuable insights into particular antecedents and associated psychological mechanisms underlying employee voice, a topic that has largely been overlooked is an evaluation of how employees’ feelings of being trusted by their leader and self-efficacy can influence their voice behavior. The relevant question is, then: What exact roles do these two mediators play in contradictory voice behavior? On the one hand, followers who are confident of their abilities are motivated to engage in voice input that can make a difference, i.e., challenging voice (advocating change). On the other hand, a higher level of self-efficacy may motivate people to think they do better than others, and, consequently, underestimate others’ opinions (Gist and Mitchell 1992; Grant and Schwartz 2011; Vancouver and Kendall 2006), which encourages followers to engage in defensive voice (protest the changes proposed by others). Similarly, when followers’ awareness of their leaders’ trust in them increases, so does their sense of responsibility and competence, which motivates them to engage in challenging voice (Bowling et al. 2010). On the flip side, however, followers’ sense of felt trust increases their pride (Baer et al. 2015) and “trustees are often willing to accept such positive information and exert effort to maintain the status quo”(Lau et al. 2014, p. 114), which motivates followers to engage in protesting against change (defensive voice) because change may lead to uncertainty regarding the status quo (Vancouver et al. 2002). In line with the previous studies in which two seemingly contradictory behaviors co-exist (Owens et al. 2015; Zhang et al. 2015), we simultaneously predict both challenging and defensive voice behaviors in followers, which explains why feeling trusted and having self-efficacy for voice is a unique psychological process that can transmit the effect of leader humility to followers’ contradictory voice behavior, as shown in Fig. 1.

This research makes five major contributions to the literature. First, although leader humility is generally considered to be a positive trait that leads only to positive outcomes in followers, the current study uses an attachment lens to challenge this consensus and further the theory on leader humility. We are confident this research can contribute to an emerging body of literature that explores the nature of contradictions in individuals’ behavior, as well as its cognitive frames and processes. Second, we interconnect leader humility and voice literature by showing how two seemingly contradictory voice behaviors can co-exist in individuals under humble leaders. Third, by challenging the consensus that feeling trusted is uniformly beneficial to employee productivity, we advance the trust literature and provide ideas which may lead to more effective managerial practices. Fourth, our outcomes in regard to leader humility and its theoretical pathways contribute to the business ethics literature, which up until now has almost always promoted the position that humility negates followers’ sense of moral self-sufficiency (Argandona 2015; Frostenson 2016).

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

Humble Leaders as Guardians/Parents

The essence of attachment theory is the role of support from others in fostering an individuals’ exploration behavior (Bowlby 1969/1982). In particular, this theory suggests that when individuals receive sensitive and responsive support from caregivers, they tend to explore and become competent in interactions with novel environments. Initially, attachment research focused on infants and their relationships with caregivers, but later research has explored its implications for leaders (Davidovitz et al. 2007; Keller 2003; Popper 2002; Popper and Amit 2009; Popper and Mayseless 2003), supervisor–subordinate relationships (Simmons et al. 2009), and co-workers (Nelson 1991). Specifically, these studies suggest that leader–follower relationships are analogous to parent–child dynamics in terms of instruction, guidance, and care (Popper and Mayseless 2003; Wu and Parker 2014).

Leader humility consists of a set of interpersonal characteristics which includes (a) an accurate view of the self, (b) openness to new ideas and feedback, and (c) a willingness to showcase followers’ strengths and contributions (Owens 2009). Thus, we expect there to be a close correspondence between good parents and humble leaders in the outcomes of their “protégés.” First, similar to good parents, humble leaders are willing to accept their vulnerabilities and promote mutual trust. Second, both good parents and humble leaders are non-judgmental, supportive, and appreciative, which in turn fosters self-confidence and self-esteem. Third, as a willingness to view themselves accurately is a core principle of humble leaders, they promote self-realization in their followers similar to what good parents do. Finally, both are positive role models. As may be seen in these similarities, the resemblance between humble leaders and parents is quite clear. Therefore, in an organizational context, we position humble leaders in a caregiver position where they provide a necessary secure base support, which predicts followers’ voice behavior through influencing their sense of security (mediating path). Moreover, recent interest in humility may therefore be attributed in part to a desire to incorporate sound moral reasoning into business decision-making environments that are increasingly complex and often perceived to be dominated by avarice.

Leader Humility and Followers’ Feeling Trusted

Research on leader humility suggests that humility may be an important factor for the kind of strong interpersonal relations, which spur cooperative relationships in the workplace (Morris et al. 2005; Rowatt et al. 2006). This line of research also suggests that leader humility increases followers’ trust in their leader, leading to a sense of safety and a supportive leader–follower relationship (Morris et al. 2005; Nielsen et al. 2010). However, “the ultimate motivation to do something or not, or to do it in a certain way is the result of a whole process in which all kinds of factors play a role” (Andriessen 1978, p. 367). Humble leaders openly show their vulnerability with their followers, which is one of the key motivations for followers’ sense of felt trust (Baer et al. 2015; Owens et al. 2011). Following this line of reasoning, we propose that leader humility influences followers’ sense of feeling trusted by fostering “safe to” voice motivation.

In the trust literature, trust and feeling trusted are often related, but not necessarily equivalent (Korsgaard et al. 2014). The key difference between these two constructs is their referents: “the referent for trusting is the truster, and the referent for felt trust is the trustee” (Lau et al. 2014, p. 114). Related to this, previous studies have shown that perceived supervisory trust enhances employees’ job performance and organization-based self-esteem (Lau et al. 2014; Pierce and Gardner 2004). Previous studies also indicate that self-disclosure is an integral component in a relationship, and often leads to increased trust and reciprocal disclosure (Collins and Miller 1994; Ehrlich and Graeven 1971).

Accordingly, as stated earlier, one of the core elements of leader humility is self-disclosure (accepting his/her personal limitations), which signals to followers that the leader considers them as trustable, and organizationally important (Morris et al. 2005). Having a humble leader who shares sensitive information and accepts critical feedbacks signals a level of trust, and followers may feel empowered by such admissions and even feel such risk-taking is reasonable and become more secure about taking risks themselves (Detert and Burris 2007; Walumbwa and Schaubroeck 2009). The incorporation of such positive messages enhances the followers’ perceptions of feeling trusted (Baer et al. 2015). Specifically, leader humility provides an opportunity for followers to realize that accepting mistakes is helpful for identifying potential areas for growth rather than serving as a source of accusations, a tendency which leads to bickering and feelings of being undervalued (Owens and Hekman 2015). Continuing along this line of reasoning, leaders’ self-disclosure also has the potential to foster transparent interactions between leaders and followers, enhancing mutual trust (Lau et al. 2014). We anticipate that this component of leader humility also fosters followers’ sense of felt trust because such leaders are willing to show vulnerability.

Furthermore, leaders’ feedback seeking behavior enhances the followers’ perceptions of trust due to the leaders’ expression of vulnerability (Ashford and Tsui 1991; Wu et al. 2014). For instance, humble leaders who show teachability by listening to others have been shown to foster greater trust and an increased sense of justice in followers because followers feel that their leaders are not egocentric (Collins and Miller 1994). When a leader is approachable, a flexible and safe work environment is fostered, and this is a key factor for followers felt trust (Baer et al. 2015; Edmondson 1999; Gao et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2014). In particular, a humble leader’s essential willingness to display vulnerability enhances the followers’ perceptions of being in a safe, nurturing environment. We, therefore, predict:

Hypothesis 1

Leader humility is positively related to followers’ feeling trusted.

Leader Humility and Followers’ Self-efficacy for Voice

Humble leaders tend to value the strengths and appreciate the good performance of their followers, which fosters the “can do” motivation level of the followers (Owens et al. 2013). Similarly, a humble leader who has self-understanding will seek help or feedback from followers when it is needed (Owens et al. 2013), which boosts the intellectual value and the importance of followers. Means, Wilson, Sturm, Biron, and Bach (1990, p. 214) suggest that “humility is an increase in the valuation of others and not a decrease in the valuation of self.” This implies that humble leaders are other-enhancing and this other-enhancing quality of humble leaders is less likely to lead to a dualistic evaluation (competent versus incompetent) of others (Owens et al. 2013). Moreover, philosophical writings on humility have shifted away from humility as self-abasement toward defining humility as a virtue that reduces the focus on self-oriented outcomes in favor of a higher focus on other-oriented outcomes (Nadelhoffer et al. 2016). This non-judgmental stance of humble leaders, coupled with a willingness to identify and value the unique abilities of followers, sends a positive signal to followers and promotes “can do” motivation (Argandona 2015; Frostenson 2016; Morris et al. 2005). Specifically, the virtue of humility has been established as both supportive of rational ethical theory and foundational to a moral point of view that guides reasoning to sound conclusions (Green 1973).

Humble leaders increase followers’ sense of psychological safety and competence by acknowledging that a certain amount of uncertainty may be unavoidable, thus encouraging followers to listen to others and both seek and propose new ideas (Owens 2009). Humility is part of the social nature of moral reflection since it involves openness (Argandona 2015; Kupfer 2003). Accordingly, business ethicist Solomon (2003) recommends demonstrating humility by not taking too much credit for positive outcomes, but instead thanking others for their part in the success. Through such actions, humble leaders showcase their followers’ strengths and push them into the limelight, causing followers to feel that their leaders are truly their guardians, a feeling that increases their competency level (Liu et al. 2017; Rego and Simpson 2018). As a result, followers of humble leaders experience a sense of self-confidence (i.e., self-efficacy), as they are able to influence their leader’s decisions without risking their careers. Humble leaders also allow followers to occasionally lead them, rather than constantly telling followers how to do things. Such a role reversal heightens the followers’ self-efficacy (Owens and Hekman 2012). In other words, “humble leaders were described as students of their followers’ strengths, and thus they were experts on the human capital around them” (Owens and Hekman 2012, p. 797).

In a deep sense, these humble behaviors can unlock the followers’ intrinsic motivation, often inspiring increased job engagement and productivity (Owens and Hekman 2012). More importantly, humble leaders encourage followers to speak out regarding their doubts, uncertainties, and respond favorably to feedback, even if it is critical, which positively affect followers’ sense of security. This is also reflected in an increasing tendency of workers to adopt a “can do” attitude toward challenges and obstacles in the workplace. Thus, we predict:

Hypothesis 2

Leader humility is positively related to followers’ self-efficacy for voice.

Mediating Mechanism Between Leader Humility and Followers’ Voice Behaviors

To complete our theoretical model, we adopt an attachment theory to explain how a humble leader’s behavior fosters a feeling that it is “safe to” speak out or try a new approach to a problem, and a “can do” attitude toward challenges. Taking this perspective leads us to predict voice behaviors in followers. In other words, when humble leaders provide support in the form of a safe environment for experimental new ideas, encourage critical thoughts, foster “other-oriented” approaches, and demonstrate a willingness to accept vulnerability by engaging in risk-taking, it leads to the establishment of a secure base which promotes followers’ contradictory voice via the effects of feeling trusted (sense of leaders’ confidence in them) and self-efficacy (sense of self-confidence).

Mediating Influence of Followers’ Feeling Trusted

Leaders’ trust can be shown through salient and concrete signals including compliments and honoring the efforts of followers (Baer et al. 2015). When followers are aware of being respected and trusted, they feel they have earned a positive boost to their reputation related to their task completion and achievements in the workplace (Morrison 1993). Leader humility reflects an “other-oriented” approach in which leaders appreciate and acknowledge contributions from followers rather than finding faults and criticizing their weaknesses; also, such leaders are open to all sorts of feedback (even if critical) and accept their own limitations and mistakes (Owens and Hekman 2012). In such cases, followers perceive the appreciation and acknowledgment related to job performance accurately, and are likely to respond positively to it by trying to increase their work performance even more, so as to receive more praise and encouragement (Ilgen et al. 1979). A relationship in which both leaders and followers trust each other influences the exploration and affiliation behavioral systems that lead to the followers’ increasing willingness to take on extra roles (Pierce and Gardner 2004). For instance, leaders are more willing to take risks with followers whom they trust (Mayer et al. 1995). Conversely, when followers believe their leaders have ability, integrity, and are benevolent, they are more likely to engage in behavior that puts them at risk (Mayer et al. 1995). Given its nature of entailing risk, a challenging voice shares some common ground with a moral voice because both involve personal risk and demonstrate care for organizations (Lee et al. 2017). Consequently, we also claim that this outcome is a negation of moral self-sufficiency as a result of the humble leaders’ influence on their followers’ sense of security. Past research has also suggested that leader humility is a less self-interested leadership style, and so can foster followers’ safety perception while building a supportive leader–follower relationship, which, in turn, motivates followers to engage in extra-role behaviors (Burris 2012; Nielsen et al. 2010). Based on these arguments, we expect followers to be more willing to take risks with leaders with whom they feel secure and trusted.

Hypothesis 3

Followers’ feeling trusted mediates the relationship between leader humility and challenging voice.

In the following section, we explore another aspect of followers feeling trusted and its outcome. In accordance with attachment theory, humble leaders’ selfless and ethics-oriented behaviors positively influence the followers’ feelings of being trusted. In particular, leader self-disclosure causes followers to sense that their leader trusts them, and they are motivated to maintain the status quo (i.e., their sense of being trusted by their leaders) (Gao et al. 2011; Morris et al. 2005). In turn, the subsequent cognitive conclusion is that the sense of “feeling trusted” should capture the heightened levels of self-image, which motivates followers to engage in defensive voice behavior.

As stated earlier, the referent for feeling trusted is the trustee. With the support of the proposition of the obligation to return, trustees develop responsibility norms in reference to job performance (Salamon and Robinson 2008). Being trusted represents a positive complement that triggers followers’ pride (Baer et al. 2015), and eventually leads followers to want to maintain this status quo to protect their self-image (Lau et al. 2014). This line of reasoning can be equated to the followers’ defensive voice motive as it is characterized by a preference for safe, secure decisions, and shielding the status quo (Maynes and Podsakoff 2014) at the expenses of humble leaders’ willingness to assume risk with their followers. Past studies have also suggested that the outcomes of followers’ feeling trusted should not only be constrained to positive aspects, as it also increases perceived workload and reputation maintenance concerns which are positively correlated to emotional exhaustion (Maynes and Podsakoff 2014). In other words, feeling trusted not only increases pro-social motives but also self-protective motives. Thus, feeling trusted should be associated with defensive voice for a number of reasons. Defensive voice behavior reflects self-protective motives as a result of the fear of losing self-image (Dyne et al. 2003; Maurer 1996; Schlenker and Weigold 1989). To protect the self, individuals employ a variety of intentional techniques, including diversionary response, exaggeration, and distortion (Turner et al. 1975). This could include assertive responses such as vocally opposing how things are done through defensive voice (Maynes and Podsakoff 2014). This is because, “the bigger that trust is, the harder one’s reputation could fall if trust were to be violated” (Bromley 1993, p. 193). As a result, changes in operating procedures may need more expertise to handle and if the results are poor, followers may feel a decrease in their self-image and, accordingly, their self-esteem (Jones and Pittman 1982; Ryan and Oestreich 1991).

Furthermore, humble leaders provide a safe space to openly share critical feedback, openly admitting his/her limitations, and recognizing and showing open appreciation of followers’ contributions. This increases the followers’ social status among their peers and satisfies the initial step of attachment theory (Bowlby 1969/1982) by encouraging a “safe to” motivational state for voice. In turn, when followers conclude that their leaders trust them, it carries an implicit responsibility to demonstrate competence that followers are expected to maintain by not engaging in changes (i.e., defensive voice), because changes may lead to uncertainty in regard to their positive self-image. Based on these and the preceding arguments, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 4

Followers’ feeling trusted mediates the relationship between leader humility and defensive voice.

Mediating Influence of Followers’ Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy refers to “a person’s estimate of his or her capacity to orchestrate performance on a specific task” (Gist and Mitchell 1992, p. 183). Secure base support from humble leaders can raise followers’ self-efficacy by persuading them to believe that they have the competence and skills to achieve their goals (Bandura 1999). Secure base support also fosters followers’ motivation to engage in actions without worrying about uncertainty as well as legitimizing uncertainty in the developmental journey (Morris et al. 2005; Owens and Hekman 2012). Moreover, encouragement from humble leaders fosters a feeling of self-determination because the leader provides a safe and secure environment (Morris et al. 2005). Consequently, enhanced self-determination elevates followers’ positive affect and sense of self-efficacy (Jones 1986; Rego and Simpson 2018; Vancouver et al. 2002). Followers’ self-efficacy, in turn, can enhance “can do” motivation for voice behavior toward leaders because individuals high in self-efficacy see chances for agency within the environment (Detert and Burris 2007; Detert and Treviño 2010; Parker et al. 2010). Although the challenging voice seeks fundamental changes in policies or practices as likely being contrary to the leaders’ fundamental beliefs (Burris 2012), humble leaders afford others a sense of voice because they are teachable, which has been shown to foster motivation and heighten a sense of justice in followers (Cropanzana et al. 2007; Owens et al. 2013). Past studies have also linked self-efficacy to many forms of voice and proactive behavior (e.g., Gist 1987; Gist and Mitchell 1992; Janssen and Gao 2015; Parker et al. 2006). Thus, we expect that humble leaders’ other-orientation and unselfish behavior will be positively related to challenging voice via its positive association with self-efficacy.

Hypothesis 5

Followers’ self-efficacy mediates the relationship between leader humility and challenging voice.

The following section explains the other side of self-efficacy and how it predicts followers’ defensive voice behaviors. Phobics with a high sense of their own capacity can overcome their fears and perform better than those with a low sense of their capacity (Bandura and McClelland 1977). Past studies have argued that the explanation of these effects is motivational and increases either levels of persistence “or” effort, and enhances self-efficacy, confidence, and trust. This leads not only to beneficial behavior but also to harmful behavior (Grant and Schwartz 2011; Lau et al. 2014; Vancouver et al. 2002). For instance, people may set unrealistically high goals because of enhanced self-efficacy, but fail to meet them, stubbornly sticking with failing strategies and spending less time and energy learning new things due to their confidence they are already adequately equipped to handle the work (Vancouver and Kendall 2006; Whyte 1998; Whyte and Saks 2007). Furthermore, Bandura and Jourden (1991) find that high self-efficacy does not increase performance, but rather contributes to decrements in performance; they conclude that “complacent self- assurance creates little incentive to expend the increased effort needed to attain high levels of performance” (Bandura and Jourden 1991, p. 949). In a similar vein, Stone (1994) finds that high self-efficacy leads to overconfidence in individuals, who then contribute less toward tasks and are less attentive compared to their low self-efficacy counterparts.

A meta-analysis of self-efficacy has also shown that negative effects might be expected under certain conditions (Boyer et al. 2000). As highlighted by Owens and Hekman (2012), humble leaders appreciate and acknowledge followers’ contributions and openly allow critical feedback. In addition, they are willing to display vulnerability by accepting their limitations, even to the point of allowing followers to lead them. With this evidence, we anticipate that these humble behaviors can provide the necessary conditions (i.e., secure base via increasing sense of self-confidence) for followers to reach a belief that they are highly competent individuals, which can ultimately lead to a defensive voice (protesting changes) in the workplace. When highly competent individuals believe that they are more competent than others, it can result in persistence with the procedures that they prefer as opposed to the procedures proposed by others (Vancouver et al. 2002). This resistance may be purely motivated by their overconfidence (Grant and Schwartz 2011; Vancouver and Kendall 2006; Vancouver et al. 2002). When looked at through an ethical lens, defensive voice behavior is based on self-defense and can be equated to moral self-sufficiency (Lee et al. 2017). It implies that one fails to acknowledge the standards, values, and viewpoints of others while identifying, judging, and adopting those outlooks which are in accordance with his/her personal interest (Gardner and Pierce 2011). One can also argue that high self-efficacy individuals may protest changes in the workplace based on the belief that they are detrimental to the organization. However, in an organizational context, past research has found that when individuals are given power, they tend to devalue the worth and input of others (Kipnis 1972). To gain more support for our argument, in addition to attachment theory, we also borrow a logic from perceptual control theory (Powers 1973) that suggests high self-efficacy direction would be negative under some circumstances. It is worth mentioning that defensive voice can be perceived either positively or negatively, based on the raters’ (leaders’) perception (Maynes and Podsakoff 2014). Given that humble leader provide the circumstances in which followers can feel highly competent and powerful, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 6

Followers’ self-efficacy mediates the relationship between leader humility and defensive voice.

Method

Sample and Procedure

We conducted a multi-source and multi-wave survey study to test the proposed hypotheses. Given the focus on leader–follower interdependence and the need for non-western sample studies in humility research, we chose an information technology (IT) company in India where rapid changes in technology have led to leader–follower interdependence in regard to knowledge exchange. The participants were professional employees, including software developers, product designer and developers, and their respective leaders. We collected data from two different sources (i.e., both followers and leaders) and two different times to avoid common method bias (Podsakoff et al. 2003). Specifically, in the survey, we asked the leaders to rate the dependent variables (i.e., two types of followers’ voice), and asked the followers to rate the independent variable, mediators, and control variables. In Time 1, the leader questionnaires were distributed to 65 leaders, and each leader was asked to rate the voice behavior of six of his/ her immediate followers, who were randomly selected. Two weeks later (i.e., Time 2), 390 immediate followers of the above leaders were asked to rate the other variables. We informed the respondents about the voluntary nature of participation, the objective of the survey, the procedures for completing the questionnaires, and the confidentiality of their responses. We used a coding scheme to ensure matched leader–follower data. The participants returned the survey to a box in the human resource department designated for the current study. Out of 65 team leaders and 390 followers, we received 57 (87.69%) of the leaders’ and 290 (74.35%) followers’ questionnaires. After eliminating missing data and unmatched responses, our final sample consisted of 257 followers matched with 57 leaders for a final overall response rate of 65.89%. Among those samples, 66.9% is male, and 33.1% is female. The majority of participants were Bachelor degree holders (53.7%), with the rest having a Masters (46.3%). Age groups were 20–30 (26.5%), 31–40 (42.8%), 41–50 (27.6%), others (3.1%), and followers’ tenure ranges from less than 1 year (16.3%) to 6–10 years (17.9%).

Measures

The surveys are in English, and unless otherwise indicated, response options ranged from 1, “strongly disagree,” to 7, “strongly agree.”

Leader Humility

The nine-item measure developed by Owens et al. (2013) was used to assess leader humility. The sample items include “This leader actively seeks feedback, even if it is critical” and “This leader admits it when he or she does not know how to do something.” Cronbach’s α was 0.87.

Feeling Trusted

We used an eight-item scale to measure feeling trusted from Baer et al. (2015). The original scales were developed by Mayer and Gavin (2005). All items were adapted to reflect employees’ beliefs that their supervisors had accepted vulnerability to them. Sample items include “If I ask why a problem occurred, my leader speaks freely even if he/she is partly to blame.” Cronbach’s α was 0.81.

Self-efficacy for Voice

We used three items from Janssen and Gao (2015) to measure self-efficacy for voice. The sample items include “I am self-assured about my capabilities to voice my opinion about work activities,” and “I have enough skills and experience to voice my opinion.” Cronbach’s α was 0.70.

Defensive Voice

As we needed scales that reflect persistence behavior, we used a six-item scale developed by Maynes and Podsakoff (2014) to measure defensive voice. The sample items are: This employee [] “Stubbornly argues against changing work methods, even when the proposed changes have merit,” and “Speaks out against changing work policies, even when making changes would be for the best.” The response scale ranges from 1 = almost never, to 7 = almost always. Since leader reported the voice behaviors of the individual followers, we calculated intraclass correlation or ICC 1 for defensive voice, and its value is 0.43. Cronbach’s α was 0.83.

Challenging Voice

We used a three-item scale adopted by Burris (2012) from the original measures developed by Van Dyne and LePine (1998b). This scale reflects our notion of “flexibility” because it advocates for changes (i.e., challenging tone). A sample item is: This employee [] “challenges me to deal with problems around here.” The response scale ranges from 1 = almost never, to 7 = almost always. Similar to defensive voice, challenging voice of the individual followers were reported by leaders. Thus, we calculated intraclass correlation or ICC 1 for challenging voice, and its value is 0.39. Cronbach’s α is 0.72.

Control Variables

We included four demographic variables, i.e., sex (0 = female, 1 = male, 2 = others), age (in years), follower’s tenure with supervisor (1 = less than a year, 2 = 1 to 2 years, 3 = 3 to 5 years, 4 = 6 to 10 years, 5 = over 10 years), and education (1 = bachelor’s degree, 2 = master’s degree, 3 = doctoral degree, and 4 = others) as control variables. We also controlled for follower ratings (the response scale ranged from 1, “strongly disagree,” to 7, “strongly agree”) of leader authentic leadership (Walumbwa et al. 2008) to observe the impact of leader humility. Authentic leadership was assessed with sixteen items and sample items include “my leader asks for ideas that challenge his/her core beliefs” and “my leader solicits feedback for improving his/her dealing with others.” The alpha reliability for this scale was 0.90.

Results

Descriptive statistics and inter-correlations among focal variables are shown in Table 1. The results of reliability test show satisfactory values of Cronbach’s alpha, ranging from 0.70 to 0.90 above the recommended level of 0.70 (Nunnally 1978).

Measurement Models

To measure the goodness of fit for the measurement model, we conducted a series of confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) with AMOS 18.0. Hu and Bentler (1999) suggest modification indices in which the fit of the proposed five-factor model (i.e., leader humility, self-efficacy for voice, feeling trusted, defensive voice, and challenging voice) has acceptable fit [Chi square (degree of freedom) [χ2 (343)] = 620.24; comparative fit index (CFI) = 0.91; incremental fit index (IFI) = 0.92; root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = 0.05]. We have compared the fit of this model with five alternative models. First, the fit (χ2 (368) = 948.47; CFI = 0.82; IFI = 0.82; RMSEA = 0.07) of a four-factor model-1 (feeling trusted and self-efficacy for voice were combined) was not better than the five-factor model. Second, the fit (χ2 (368) = 886.94; CFI = 0.84; IFI = 0.84; RMSEA = 0.07) of four-factor model-2 (challenging voice and defensive voice were combined) was slightly better than a four-factor-1 model, but it is not better than a five-factor model. Third, we tried a three-factor model in which we combined feeling trusted and self-efficacy for voice, as well as challenging and defensive voice and the fit result [χ2 (371) = 977.94; CFI = 0.81; IFI = 0.81; RMSEA = 0.08] was inferior to the alternatives. Fourth, we examined a two-factor model (which combined leader humility, feeling trusted, self-efficacy for voice, and voice behaviors) and the fit result was [χ2 (373) = 1310.03; CFI = 0.71; IFI = 0.71; RMSEA = 0.09] still below the cutoff values. Finally, we tried a one-factor model result [χ2 (374) = 1630.18; CFI = 0.61; IFI = 0.61; RMSEA = 0.11], but it was also inferior to the proposed model and below the cutoff values. The results of this analysis provide support for the construct validity of our set of focal variables.

Results of Hypotheses Testing

Although we measured the study variables at the individual level, after taking into consideration the rater effect results on followers’ voice behaviors and past research (Duan et al. 2017; Janssen and Gao 2015; Lin et al. 2017), we opted to use multilevel analysis in SPSS to test the proposed hypotheses.

In Table 2, we predicted that feeling trusted and leader humility would have a positive relationship (β = 0.39, SE = 0.04, p < 0.001; Model 1). In Model 2, we also predicted a positive relationship between self-efficacy for voice and leader humility (β = 0.22, SE = 0.07, p < 0.01). Hence, both hypothesis 1 and 2 are supported. We next made predictions regarding challenging voice and defensive voice. In Model 3, leader humility has no significant effect on challenging voice behavior (β = 0.19, SE = 0.10, ns). In model 4, when feeling trusted and having self-efficacy for voice were included, both self-efficacy for voice (β = 0.27, SE = 0.09, p < 0.01) and feeling trusted (β = 0.51, SE = 0.13, p < 0.001) positively predict challenging voice. Furthermore, in Model 5, the result shows that leader humility positively predicts defensive voice (β = 0.20, SE = 0.06, p < 0.01). Finally, in Model 6, both self-efficacy for voice (β = 0.16, SE = 0.05, p < 0.01) and feeling trusted (β = 0.38, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001) predict defensive voice behavior. These results provide support for hypotheses 3–6.

Following a procedure recommended by Hayes (2013), we tested the indirect effect of leader humility through two mediators (i.e., followers’ self-efficacy for voice and feeling trusted). The results are shown in Table 3. The indirect effects of followers’ feeling trusted [β = 0.22, SE = 0.06, 95% CI (0.12 0.36)] and self-efficacy for voice [β = 0.07, SE = 0.03, 95% CI (0.02, 0.16)] on challenging voice are significant. Likewise, the two mediators, feeling trusted [β = 0.16, SE = 0.03, 95% CI (0.08, 0.28)], and self-efficacy for voice [β = 0.04, SE = 0.01, 95% CI (0.01, 0.08)] prove to be significantly correlated to defensive voice. Collectively, these results are consistent with the proposed hypotheses.

Discussion

Summary

While the positive outcomes of leader humility for organizations are clear and well explained in the literature, the other outcomes and implications of leader humility tend to be murky or elided altogether. Previous empirical research on leader humility has demonstrated that followers’ behavioral outcomes when encountering leader humility are positive. On the contrary, the purpose of this research is to examine the leader humility potential for contradictory outcomes through followers feeling trusted and self-efficacy for voice.

Integration of Study Results

In the present study, the results regarding feeling trusted and self-efficacy for voice are relatively straightforward. As hypothesized, leader humility may be influenced directly, regardless of any attribution of behavior. Followers may simply interpret leader humility as a positive cue about the leader and perceive them accordingly. This suggests the importance of a context that is supported by leader humility. In particular, leaders’ vulnerability and openness can enhance followers’ feeling trusted and self-efficacy for voice because it may make followers feel more confident about sharing their thoughts and taking risks. Furthermore, followers’ sense of security (feeling trusted and having self-efficacy for voice) is related to each of the voice outcomes and mediates the influence of leader humility on voice outcomes. This result supports our suggestion that leader humility outcomes are not uniform and consistent. Overall, these findings are important because they show that leader humility can lead to seemingly contradictory outcomes via followers’ sense of security, i.e., feeling trusted and having self-efficacy for voice. Therefore, our study opens a new avenue of research in leader humility and its influence on followers’ multiple voice behavior.

Theoretical Implications

This study makes several contributions to the research on leader humility, trust, and voice studies. First, this research expands the nomological net by examining seemingly contradictory voice behavior (challenging voice and defensive voice) as a result of leader humility. This finding is particularly relevant to the dual voice inquiry, which may offer new and more enabling understandings of seemingly contradictory voice behavior. While recent research has shown that humility is generally a positive leadership trait which can enhance followers’ personal sense of power, and is a strong predictor of employee voice (Lin et al. 2017), the current study is among the first attempts to show that humility can also lead to contradictory voice behavior in followers. In doing so, we provide some initial evidence that humble leaders can foster these competing behaviors in followers; this approach challenges contingency theorists, who tend to favor an either/or approach (Knight and Harvey 2015; Lüscher and Lewis 2008). However, whether these two opposing behaviors can increase organizational performance is beyond the scope of this study.

Second, our study’s findings provide some hard data on the predictability of certain outcomes resulting from leader humility, which have received little empirical study. Although attachment theory has been employed to understand the leader–follower process (Davidovitz et al. 2007; Mayseless 2010; Wu and Parker 2012), our study is among one of the first to explore the relationship between leader humility and followers’ seemingly contradictory voice behavior through an attachment lens.

Third, we also address the scarcity of studies dealing with the topic of the effects of followers’ feeling trusted by management (Baer et al. 2015). We are confident the present work can enrich the understanding of multiple effects that feeling trusted can catalyze. A substantial body of research has emphasized that feeling trusted is beneficial to both workplace relationships and followers’ organizational citizenship behavior (Lau et al. 2014; Mayer and Gavin 2005; Salamon and Robinson 2008). However, our study demonstrates how feeling trusted can make followers engage in both challenging and defensive voice at the same time, which helps to round out our understanding of the phenomenon by complexifying what has hitherto been seen as having no down-side. In addition, our findings are also grounded in a theoretical basis that is new to the trust literature—attachment theory.

Furthermore, our study contributes to the self-efficacy literature by showing how self-efficacy for voice has an influential role and can help predict contradictory voice behavior through the use of an attachment theory lens. Although we find that self-efficacy is positively correlated to defensive voice, we do not want to imply that high self-efficacy is harmful. Our motivation has not been to disparage self-efficacy but to provide the theoretical lens and the path to tease out some ramifications, which previous theorists have failed to consider. Taken together, we have integrated leader humility literature with voice literature to create a richer model with which to examine how followers’ sense of security (sense of self-confidence and sense of leaders’ confidence in them) can serve as a potential mediating mechanism to shed lights on followers’ voice behavior.

Finally, although humility is an important virtue and contributes to leaders’ moral and professional development, in neither the business world nor in ethics literature has humility been recognized and ranked as a key virtue (Argandona 2015). Apart from the potential beneficial outcomes of discouraging hubris in a business context, to highlight the importance of humility and its contradictory outcomes in followers’ behavior, in this study we show that promoting humility itself may not only lead to beneficial outcomes, but also contradictory outcomes in a dynamic business context. Following this line of reasoning, the findings of the current study also contribute to the business ethics literature by showing various potential contradictory outcomes in followers’ behavior under humble leaders (i.e., ethical-oriented leaders) through a theoretical lens. First of all, our study contributes to the business ethics literature by examining followers’ voice outcomes (challenging voice and defensive voice). For instance, challenging voice may include suggestions that improve organizations’ efficiency or inhibit unethical work behaviors. Secondly, contrary to the claims made in the business ethics literature, that humility can negate individuals’ self-sufficiency (Argandona 2015; Frostenson 2016), we show the mediating mechanism to explain why and how leader humility leads to followers’ defensive voice behavior, which might be viewed as self-sufficiency, i.e., a failure to acknowledge the viewpoints of others (Frostenson 2016; Vera and Rodriguez-Lopez 2004). Similar to Maynes and Podsakoff (2014), we do not argue that being defensive is desirable or undesirable, but merely show the psychological mechanism connecting leader humility and followers’ defensive voice behavior. In doing so, this study sheds light and provides a theoretical explanation, backed by empirical evidence, for why and how the potentially contradictory voice behavior may be elicited by humble leaders among followers within the organization. This serves as the initial evidence in the business ethics literature related to humility and its influence on individuals’ self-reliance (Argandona 2015; Frostenson 2016).

Managerial Implications

As one of the first studies to empirically examine the seemingly contradictory outcomes of leader humility on voice, the present research should provide practical implications for leaders and human resource managers. In the past, leaders have been known for the personality characteristics of dominance, narcissism, and aggression. On the contrary, our research has found that humble leaders inspire voice behavior through influencing followers’ sense of security. Therefore, organizations should encourage leaders to have more humility and less hubris. Our study’s findings also demonstrate that leader humility can have a contradictory outcome on followers’ behavior. In regard to actual business practices, the findings from our study suggest that in a creative context where followers’ exploration is important, leaders should actively support non-uniform behaviors. However, excessive stubbornness in followers may harm group cohesion and organizational effectiveness. As self-sufficiency plays a primary role in reducing the quality of ethics in business (Frostenson 2016), we recommend that leaders practice a more nuanced view of humility. Although humility can be seen as a midpoint (i.e., between deficiency and excess) of temperance virtue (Crossan et al. 2013), when an other-oriented humble leader seeks the best for all concerned, he or she must both manage the non-uniformity which may arise and seek an optimal point along the continuum rather than defaulting to what feels balanced simply because it is a midpoint (Rego et al. 2012; Tsoukas 2017).

Our approach—using attachment theory—provides insights into feeling trusted and self-efficacy. These may help humble leaders to reduce certain harmful effects that may result from over-empowered followers. Although we do not claim the defensive voice outcome is detrimental, we warn that anything excessive does have that potential. How, then, should leaders handle these feeling trusted and self-efficacy dynamics? One crucial factor is remaining aware that the acceptance of vulnerability brings a variety of consequences. In this way, humble leaders should understand that their behavior influences their follower’s cognition, and such influence might be balanced by celebrating a team’s successes and failures equally. By doing so, followers may perceive social status is not at stake even at failure that may reduce losing of self-image. More importantly, teams’ success is often attributed to leadership effectiveness; thus, humble leader’s other-oriented behavior may neutralize or negate the followers’ self-sufficiency. Therefore, organizations should often celebrate teams’ successes and recognize the leaders’ humble behaviors as well.

Limitations and Future Studies

As with any study, this study has several limitations. First, as our study design is cross-sectional, there might be bi-directional relationships owing to the possibility that followers might seek to enhance their self-efficacy and felt trust by engaging in voice behavior. As a result, followers with higher self-confidence who speak out may be more likely to receive fair or unfair treatment from their leaders than low-confidence followers. A valid argument against this potential for reversed causality can be found in attachment theory, which suggests that a leaders’ secure base of support enhances followers’ sense of security, and enhanced levels of such self-confidence and sense of leaders’ confidence in them increase followers’ motivation to engage in voice behaviors (Exline and Geyer 2004; Owens et al. 2011). However, we encourage longitudinal and qualitative studies to provide firm evidence of causation. Although theoretical reasoning supports both voice outcomes (challenging voice and defensive voice), such outcomes may also be influenced by the leaders’ counterbalancing traits, such as confidence and competence. With this in mind, future studies may adopt suitable moderators to examine the influences of counterbalancing traits, which can be justified through implicit theories of leadership.

Second, leader humility fosters two-way learning processes (Owens and Hekman 2012); hence, leader–follower behavior and the quality of their relationship may influence the learning process. However, we did not include the impact of followers’ attachment styles on the relationship between the leaders’ behavior and followers’ sense of security constructs and LMX (leader-member exchange) in our study to measure the influence. Future studies may want to consider this either as a moderator or control variable. Furthermore, the individual’s motivational type can also serve as a crucial factor of voice (Aryee et al. 2014; Tangirala and Ramanujam 2008). For instance, an individual who has an approach motivation (promotion focus) could engage in more improvement-oriented tasks, whereas avoidance motivation (prevention focus) prevents individuals from engaging in riskier behaviors. Thus, future research can explore these motivations by using regulatory focus theory as it suggests that individuals pursue goals in ways that maintain the individuals’ regulatory orientations (promotion and prevention) (Higgins 1997). The examination of individuals’ motivation type may lead to a better understanding of the relationship between having a sense of a secure base and voice behaviors under humble leaders. As our study examines contradictory outcomes, it would be useful if future studies could examine the interplay between approach and avoidance motivation on followers’ voice behavior.

Third, in this study, we categorize and examine both challenging and defensive voice in a creative context (an IT firm) and, therefore, it is limited with respect to generalizability to other sectors. One further avenue for future research is to explore various types of contradictory voice outcomes across contexts and look at which type of contradictory voice is most likely to emerge from followers’ sense of security. In this study, we do not claim that contradictory voice behavior can lead to organizational effectiveness, as it is not the focus of the current study. Moreover, we are aware of no prior research that has empirically examined how two seemingly contradictory voice behaviors interact and how they are related to organizational effectiveness. Prior research has suggested that the organizational learning process is inherently paradoxical (i.e., the complementary and interrelated relationship between radical and incremental learning process). As a result, “although choosing among competing tensions might aid short-term performance, a paradox perspective argues that long-term sustainability requires continuous efforts to meet multiple, divergent demands” (Smith and Lewis 2011, p. 381). If this problem is to be explored using a paradoxical lens, future research should examine whether the interaction of two seemingly contradictory voice behaviors contributes to organizational effectiveness.

Fourth, in this study, in line with attachment theory, we hypothesize that followers perceive leader humility in a positive way that affects their sense of security. Moreover, leadership is a perception (Eden and Leviatan 1975); thus, it might be possible for some followers to perceive leader humility as a socially desirable behavior, not as genuine humility. As this possibility goes beyond our study, we suggest a mechanism by which such evaluation could occur. Future research could operationalize such speculations to determine their effects.

Finally, given the fact that the proposed model has five variables and our sample source (an IT firm) and the subjects (engineers) are time sensitive, in order to maintain the high response rate and data quality we were unable to include more control variables in addition to authentic leadership. Previous studies have investigated the influence of psychological safety and attachment styles on proactive behavior or voice context (Edmondson 1999; Liu et al. 2015; Walumbwa and Schaubroeck 2009). Thus, future research in this line of study may need to control for such variables. We also recommend that future research try to replicate our findings using samples from Western contexts.

Conclusion

It is generally accepted that leader humility has a positive impact on employee outcomes. However, in this research, by applying attachment theory, our results demonstrate that leader humility fosters followers’ sense of security (feeling trusted, self-efficacy for voice), which leads to seemingly contradictory voice behaviors in followers. We neither suggest that leader humility is simply a source of seemingly contradictory voice behavior, nor that leader humility is merely bad. While we believe that leader humility is vital and that leaders ought to exhibit such behavior, it is still important to call attention to the use of an attachment theory lens to disrupt the existing frames—frames that contain perceptions within current belief systems regarding humility, self-efficacy, felt trust, and voice behaviors. Although additional research is clearly needed to establish the generalizability of our results, our findings can be seen as a modest beginning that provides evidence regarding leader humility and voice behaviors, further supporting the fruitfulness of this direction for research and showing that leader humility outcomes are not always obvious.

References

Amason, A. C. (1996). Distinguishing the effects of functional and dysfunctional conflict on strategic decision making: Resolving a paradox for top management teams. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 123–148.

Andriessen, J. (1978). Safe behaviour and safety motivation. Journal of Occupational Accidents, 1, 363–376.

Argandona, A. (2015). Humility in management. Journal of Business Ethics, 132, 63–71.

Aryee, S., Walumbwa, F. O., Mondejar, R., & Chu, C. W. (2014). Core self-evaluations and employee voice behavior test of a dual-motivational pathway. Journal of Management, 43, 946–966.

Ashford, S. J., & Tsui, A. S. (1991). Self-regulation for managerial effectiveness: The role of active feedback seeking. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 251–280.

Baer, M. D., Dhensa-Kahlon, R. K., Colquitt, J. A., Rodell, J. B., Outlaw, R., & Long, D. M. (2015). Uneasy lies the head that bears the trust: The effects of feeling trusted on emotional exhaustion. Academy of Management Journal, 58, 1637–1657.

Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory of personality. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research (pp. 154–196). New York: The Guilford Press.

Bandura, A., & Jourden, F. J. (1991). Self-regulatory mechanisms governing the impact of social comparison on complex decision making. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 941–951.

Bandura, A., & McClelland, D. C. (1977). Social learning theory. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

Bowlby, J. (1969/1982). Attachment and Loss: Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

Bowling, N. A., Eschleman, K. J., & Wang, Q. (2010). A meta-analytic examination of the relationship between job satisfaction and subjective well-being. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 83, 915–934.

Boyer, D., Zollo, J., Thompson, C., Vancouver, J., Shewring, K., & Sims, E. (2000). A quantitative review of the effects of manipulated self-efficacy on performance. Paper presented at the Poster session presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Society Miami, FL.

Bromley, D. B. (1993). Reputation, Image and Impression Management. New York, NY: Wiley.

Brower, H. H., Lester, S. W., Korsgaard, M. A., & Dineen, B. R. (2009). A closer look at trust between managers and subordinates: Understanding the effects of both trusting and being trusted on subordinate outcomes. Journal of Management, 35, 327–347.

Burris, E. R. (2012). The risks and rewards of speaking up: Managerial responses to employee voice. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 851–875.

Collins, N. L., & Miller, L. C. (1994). Self-disclosure and liking: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 116, 457–475.

Cropanzana, R., Bowen, D. E., & Gilliland, S. W. (2007). The management of organizational justice. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 21, 34–48.

Crossan, M., Mazutis, D., & Seijts, G. (2013). In search of virtue: The role of virtues, values and character strengths in ethical decision making. Journal of Business Ethics, 113, 567–581.

Davidovitz, R., Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P. R., Izsak, R., & Popper, M. (2007). Leaders as attachment figures: Leaders’ attachment orientations predict leadership-related mental representations and followers’ performance and mental health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 632–650.

Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal, 50, 869–884.

Detert, J. R., & Edmondson, A. C. (2011). Implicit voice theories: Taken-for-granted rules of self-censorship at work. Academy of Management Journal, 54, 461–488.

Detert, J. R., & Treviño, L. K. (2010). Speaking up to higher-ups: How supervisors and skip-level leaders influence employee voice. Organization Science, 21, 249–270.

Duan, J., Li, C., Xu, Y., & Wu, C. h. (2017). Transformational leadership and employee voice behavior: A Pygmalion mechanism. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38, 650–670.

Dyne, L. V., Ang, S., & Botero, I. C. (2003). Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 1359–1392.

Eden, D., & Leviatan, U. (1975). Implicit leadership theory as a determinant of the factor structure underlying supervisory behavior scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60, 736–741.

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 350–383.

Ehrlich, H. J., & Graeven, D. B. (1971). Reciprocal self-disclosure in a dyad. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 7, 389–400.

Exline, J. J., & Geyer, A. L. (2004). Perceptions of humility: A preliminary study. Self and Identity, 3, 95–114.

Frostenson, M. (2016). Humility in business: A contextual approach. Journal of Business Ethics, 138, 91–102.

Gao, L., Janssen, O., & Shi, K. (2011). Leader trust and employee voice: The moderating role of empowering leader behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 22, 787–798.

Gardner, D. G., & Pierce, J. L. (2011). A question of false self-esteem: Organization-based self-esteem and narcissism in organizational contexts. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 26, 682–699.

Gist, M. E. (1987). Self-efficacy: Implications for organizational behavior and human resource management. Academy of Management Review, 12, 472–485.

Gist, M. E., & Mitchell, T. R. (1992). Self-efficacy: A theoretical analysis of its determinants and malleability. Academy of Management Review, 17, 183–211.

Grant, A. M., & Schwartz, B. (2011). Too much of a good thing the challenge and opportunity of the inverted U. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 61–76.

Green, R. (1973). Jewish ethics and the virtue of humility. The Journal of Religious Ethics, 1, 53–63.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Higgins, E. T. (1997). Beyond pleasure and pain. American Psychologist, 52, 1280–1300.

Hu, L. t., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55.

Ilgen, D. R., Fisher, C. D., & Taylor, M. S. (1979). Consequences of individual feedback on behavior in organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 64, 349–371.

Janssen, O., & Gao, L. (2015). Supervisory responsiveness and employee self-perceived status and voice behavior. Journal of Management, 41, 1854–1872.

Jones, E. E., & Pittman, T. S. (1982). Toward a general theory of strategic self-presentation. Psychological Perspectives on the Self, 1, 231–262.

Jones, G. R. (1986). Socialization tactics, self-efficacy, and newcomers’ adjustments to organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 29, 262–279.

Keller, T. (2003). Parental images as a guide to leadership sensemaking: An attachment perspective on implicit leadership theories. The Leadership Quarterly, 14, 141–160.

Kipnis, D. (1972). Does power corrupt? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 24, 33–41.

Knight, E., & Harvey, W. (2015). Managing exploration and exploitation paradoxes in creative organisations. Management Decision, 53, 809–827.

Korsgaard, M. A., Brower, H. H., & Lester, S. W. (2014). It isn’t always mutual a critical review of dyadic trust. Journal of Management, 41, 47–70.

Kupfer, J. (2003). The moral perspective of humility. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 84, 249–269.

Lau, D. C., Lam, L. W., & Wen, S. S. (2014). Examining the effects of feeling trusted by supervisors in the workplace: A self-evaluative perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35, 112–127.

Lee, D., Choi, Y., Youn, S., & Chun, J. U. (2017). Ethical leadership and employee moral voice: The mediating role of moral efficacy and the moderating role of leader–follower value congruence. Journal of Business Ethics, 141, 47–57.

Lewis, M. W. (2000). Exploring paradox: Toward a more comprehensive guide. Academy of Management Review, 25, 760–776.

Lin, X., Chen, Z. X., Herman, H., Wei, W., & Ma, C. (2017). Why and when employees like to speak up more under humble leaders? The roles of personal sense of power and power distance. Journal of Business Ethics, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3704-2.

Liu, S., Liao, J., & Wei, H. (2015). Authentic leadership and whistleblowing: Mediating roles of psychological safety and personal identification. Journal of Business Ethics, 131, 107–119.

Liu, W., Mao, J., & Chen, X. (2017). Leader humility and team innovation: investigating the substituting role of task interdependence and the mediating role of team voice climate. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1115–1127.

Lüscher, L. S., & Lewis, M. W. (2008). Organizational change and managerial sensemaking: Working through paradox. Academy of Management Journal, 51, 221–240.

Maurer, R. (1996). Beyond the wall of resistance: Unconventional strategies that build support for change. Austin: TX Bard Austin.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20, 709–734.

Mayer, R. C., & Gavin, M. B. (2005). Trust in management and performance: Who minds the shop while the employees watch the boss? Academy of Management Journal, 48, 874–888.

Maynes, T. D., & Podsakoff, P. M. (2014). Speaking more broadly: An examination of the nature, antecedents, and consequences of an expanded set of employee voice behaviors. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99, 87–112.

Mayseless, O. (2010). Attachment and the leader—follower relationship. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 27, 271–280.

Means, J. R., Wilson, G. L., Sturm, C., Biron, J. E., & Bach, P. J. (1990). Humility as a psychotherapeutic formulation. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 3, 211–215.

Morris, J. A., Brotheridge, C. M., & Urbanski, J. C. (2005). Bringing humility to leadership: Antecedents and consequences of leader humility. Human Relations, 58, 1323–1350.

Morrison, E. W. (1993). Newcomer information seeking: Exploring types, modes, sources, and outcomes. Academy of management Journal, 36, 557–589.

Nadelhoffer, T., Wright, J. C., Echols, M., Perini, T., & Venezia, K. (2016). Some varieties of humility worth wanting. Journal of Moral Philosophy, 14, 168–200.

Nelson, D. L. (1991). Psychological contracting and newcomer socialization: An attachment theory foundation. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 6, 55–72.

Nielsen, R., Marrone, J. A., & Slay, H. S. (2010). A new look at humility: Exploring the humility concept and its role in socialized charismatic leadership. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 17, 33–43.

Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric methods. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Owens, B. P. (2009). Humility in organizational leadership. (PhD Dissertation), University of Washington, USA. (3370531).

Owens, B. P., & Hekman, D. R. (2012). Modeling how to grow: An inductive examination of humble leader behaviors, contingencies, and outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 787–818.

Owens, B. P., & Hekman, D. R. (2015). How does leader humility influence team performance? Exploring the mechanisms of contagion and collective promotion focus. Academy of Management Journal, 59, 1088–1111.

Owens, B. P., Johnson, M. D., & Mitchell, T. R. (2013). Expressed humility in organizations: Implications for performance, teams, and leadership. Organization Science, 24, 1517–1538.

Owens, B. P., Rowatt, W. C., & Wilkins, A. L. (2011). Exploring the relevance and implications of humility in organizations. In K. Cameron & G. Spreitzer (Eds.), Handbook of positive organizational scholarship (pp. 260–272). New York: Oxford University Press.

Owens, B. P., Wallace, A. S., & Waldman, D. A. (2015). Leader narcissism and follower outcomes: The counterbalancing effect of leader humility. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100, 1203–1213.

Parker, S. K., Bindl, U. K., & Strauss, K. (2010). Making things happen: A model of proactive motivation. Journal of Management, 36, 827–856.

Parker, S. K., Williams, H. M., & Turner, N. (2006). Modeling the antecedents of proactive behavior at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 636–652.

Pierce, J. L., & Gardner, D. G. (2004). Self-esteem within the work and organizational context: A review of the organization-based self-esteem literature. Journal of Management, 30, 591–622.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903.

Popper, M. (2002). Narcissism and attachment patterns of personalized and socialized charismatic leaders. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 19, 797–809.

Popper, M., & Amit, K. (2009). Attachment and leader’s development via experiences. The Leadership Quarterly, 20, 749–763.

Popper, M., & Mayseless, O. (2003). Back to basics: Applying a parenting perspective to transformational leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 14, 41–65.

Powers, W. T. (1973). Behavior: The control of perception. Chicago: Aldine.

Rego, A., Cunha, M. P., & Clegg, S. R. (2012). The virtues of leadership: Contemporary challenges for global managers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rego, A., Owens, B., Yam, K. C., Bluhm, D., Cunha, M. P. e., Silard, A.,…Liu, W. (2017). Leader humility and team performance: exploring the mediating mechanisms of team psycap and task allocation effectiveness. Journal of Management. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316688941.

Rego, A., & Simpson, A. V. (2018). The perceived impact of leaders’ humility on team effectiveness: An empirical study. Journal of Business Ethics, 148, 205–218.

Rowatt, W. C., Powers, C., Targhetta, V., Comer, J., Kennedy, S., & Labouff, J. (2006). Development and initial validation of an implicit measure of humility relative to arrogance. Journal of Positive Psychology, 1, 198–211.

Ryan, K. D., & Oestreich, D. K. (1991). Driving fear out of the workplace: How to overcome the invisible barriers to quality, productivity, and innovation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Salamon, S. D., & Robinson, S. L. (2008). Trust that binds: The impact of collective felt trust on organizational performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 593–601.

Schlenker, B. R., & Weigold, M. F. (1989). Self-identification and accountability. In R. A. Giacalone & P. Rosenfeld (Eds.), Impression management in the organization (pp. 21–43). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Simmons, B. L., Gooty, J., Nelson, D. L., & Little, L. M. (2009). Secure attachment: Implications for hope, trust, burnout, and performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30, 233–247.

Smith, W. K., & Lewis, M. W. (2011). Toward a theory of paradox: A dynamic equilibrium model of organizing. Academy of Management Review, 36, 381–403.

Solomon, R. C. (1992). Ethics and excellence: Cooperation and integrity in business. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Solomon, R. C. (2003). A better way to think about business: How personal integrity leads to corporate success. New York: Oxford University Press.

Stone, D. N. (1994). Overconfidence in initial self-efficacy judgements: Effects on decision processes and performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 59, 452–474.

Tangirala, S., & Ramanujam, R. (2008). Exploring nonlinearity in employee voice: The effects of personal control and organizational identification. Academy of Management Journal, 51, 1189–1203.

Tsoukas, H. (2017). Strategy and virtue: Developing strategy-as-practice through virtue ethics. Strategic Organization, 1476127017733142.

Turner, R. E., Edgley, C., & Olmstead, G. (1975). Information control in conversations: Honesty is not always the best policy. The Kansas Journal of Sociology, 11, 69–89.

Van Dyne, L., & LePine, J. A. (1998a). Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Academy of Management Journal, 41, 108–119.

Van Dyne, L., & LePine, J. A. (1998b). Predicting voice behavior in work groups. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 853–858.

Vancouver, J. B., & Kendall, L. N. (2006). When self-efficacy negatively relates to motivation and performance in a learning context. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1146–1153.

Vancouver, J. B., Thompson, C. M., Tischner, E. C., & Putka, D. J. (2002). Two studies examining the negative effect of self-efficacy on performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 506–516.

Vera, D., & Rodriguez-Lopez, A. (2004). Strategic virtues: Humility as a source of competitive advantage. Organizational Dynamics, 33, 393–408.

Walumbwa, F. O., Avolio, B. J., Gardner, W. L., Wernsing, T. S., & Peterson, S. J. (2008). Authentic leadership: Development and validation of a theory-based measure. Journal of Management, 34, 89–126.

Walumbwa, F. O., & Schaubroeck, J. (2009). Leader personality traits and employee voice behavior: Mediating roles of ethical leadership and work group psychological safety. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 1275–1286.

Whyte, G. (1998). Recasting Janis’s groupthink model: The key role of collective efficacy in decision fiascoes. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 73, 185–209.

Whyte, G., & Saks, A. M. (2007). The effects of self-efficacy on behavior in escalation situations. Human Performance, 20, 23–42.

Wu, C.-H., & Parker, S. K. (2012). The role of attachment styles in shaping proactive behaviour: An intra-individual analysis. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 85, 523–530.

Wu, C.-H., & Parker, S. K. (2014). The role of leader support in facilitating proactive work behavior a perspective from attachment theory. Journal of Management, 43, 1025–1049.

Wu, C.-H., Parker, S. K., & De Jong, J. P. (2014). Feedback seeking from peers: A positive strategy for insecurely attached team-workers. Human Relations, 67, 441–464.

Zhang, Y., Waldman, D. A., Han, Y.-L., & Li, X.-B. (2015). Paradoxical leader behaviors in people management: Antecedents and consequences. Academy of Management Journal, 58, 538–566.

Funding

This study is not funded.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

In this study, we collected data from employees (human) in an IT organization. Before collecting data, we have got an ethical approval from the Australian National University’s (ANU) human ethics committee. Therefore, all procedures performed in study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the ANU’s human ethics committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the research.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bharanitharan, K., Chen, Z.X., Bahmannia, S. et al. Is Leader Humility a Friend or Foe, or Both? An Attachment Theory Lens on Leader Humility and Its Contradictory Outcomes. J Bus Ethics 160, 729–743 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3925-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-018-3925-z