Abstract

This study empirically investigated the impact of ethical leadership on employee burnout, deviant behavior and task performance through two psychological mechanisms: (1) developing higher levels of employee trust in leaders and (2) demonstrating lower levels of surface acting toward their leaders. Our theoretical model was tested using data collected from employees of a pharmaceutical retail chain company. Analyses of multisource time-lagged data from 45 team leaders and 247 employees showed that employees’ trust in leaders and surface acting significantly mediated the relationships between ethical leadership and employee burnout, deviant behavior and task performance. We discuss the theoretical and practical implications of our findings for understanding how ethical leaders influence employees’ attitudes and behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recently, a growing body of research on harmful or even destructive employee attitudes and behavior, such as burnout and workplace deviance, has emerged (Liao et al. 2004; Neubert and Roberts 2013). These attitudes and behaviors have been shown to be most prevalent among employees who do “people work” (Mitchell and Ambrose 2007). Such employees may significantly violate the norms that are necessary for effective team performance (Mayer et al. 2009; Robinson and Bennett 1995).

In response to the increasing interest in finding ways to alleviate employee burnout and workplace deviance, researchers have explored various antecedents to such behavior at both the individual level (e.g., individual personality) and team level (e.g., transformational leadership) (Mulki et al. 2006). Recent studies have indicated that employees tend to be less stressed and have greater job satisfaction when they work under a leader who acts as a principal source of ethical guidance (Schaufeli and Bakker 2004; Sharif and Scandura 2013). As a consequence, ethical leadership that emphasizes ethics-related actions has recently been recognized as an important factor in reducing employee burnout and deviant behavior and in improving work performance (e.g., Resick et al. 2013; Taylor and Pattie 2014; Walumbwa et al. 2011). Serving as attractive, credible and legitimate role models, ethical leaders may influence employees by capturing their attention and making the message of positive ethics salient in their organizations (Trevino et al. 2000, 2003; Brown et al. 2005).

However, a critical question remains about the underlying psychological mechanisms that link ethical leadership to individual burnout, deviant behavior and work performance. Past research has focused on the positive impact of ethical leadership at the team or organizational level (Kalshoven et al. 2011). That is, ethical leadership may enhance a team-level ethical culture/climate that subsequently leads to individual employees’ ethical and unethical cognition and behavior (e.g., Mayer et al. 2010; Schaubroeck et al. 2012). However, the specific psychological mechanisms that prevent individual employees from experiencing burnout and work deviance under the supervision of an ethical leader have not yet been studied.

Drawing on the conservation of resources theory, we suggest that ethical leadership reduces employee burnout and deviant behavior by enhancing employees’ trust in leaders and reducing employees’ surface acting. As noted by Brown et al. (2005), employees generally perceive their leader as a role model and, via a broad range of leader-member interactions, develop an ethical perspective toward their leader and the organization. As such, under the supervision of an ethical leader, employees have access to more psychological resources, especially interpersonal trust, which protect them from burnout (Dirks and Ferrin 2002; Hobfoll 1989; Sharif and Scandura 2013). Moreover, in such an environment, they are more likely to feel able to express their inner feelings without creating an undesirable image in the workplace interaction (Hochschild 1983). Subsequently, employees are less likely to engage in deviant behavior that will be potentially harmful for the focal leader and are more likely to achieve better work performance in the organization. Past studies have indicated that under the supervision of an unethical leader, employees are directly enforced to do either what the leader does or what the leader expects them to do without internalizing such behavior (Brown 2007). In this study, we therefore focus on surface acting as opposed to deep acting.

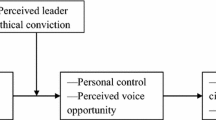

The primary focus of this research is to investigate the psychological mechanisms that link ethical leadership to employee work-related outcomes. Specifically, drawing on past research on ethical leadership (Brown et al. 2005; Brown and Trevino 2006; Brown 2007), we examine the mediating roles of both employee trust in leaders and surface acting in dealing with leaders in the relationships between ethical leadership and employee burnout, deviant behavior and task performance. By hypothesizing and testing these relationships, this study makes several contributions. First, it substantiates the value of ethical leadership in preventing employees’ negative attitudes and behavior. Past research has mainly explored the impact of ethical leadership on pro-social behavior, such as organizational citizenship behavior (Kalshoven et al. 2011; Neubert et al. 2009; Neubert and Roberts 2013); however, less attention has been paid to the effects of ethical leadership on negative work outcomes, such as deviant behavior. Second, the majority of the existing ethical leadership studies have been conducted at the group or organizational level and have been oriented less toward understanding the psychological mechanisms at the individual level (Mayer et al. 2009). The present study contributes to the ethical leadership literature by identifying two important psychological mechanisms that prevent employees from burnout and work deviance. Specifically, based on the conservation of resources theory, this study suggests that ethical leadership may significantly reduce employee burnout and deviant behavior. It also suggests that ethical leadership enhances task performance because employees are able to obtain critical psychological resources, such as trust in leaders, and express their opinions on how the ethical leader behaves, thereby reducing the necessity of surface acting (see Fig. 1).

Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

The Nature of Ethical Leadership

Defined by Brown et al. (2005), ethical leadership refers to “the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making” (p. 120). In other words, to be an ethical leader depends on how others perceive the leader across two dimensions: as a moral person and as a moral manager (Trevino et al. 2000, 2003). As a moral person, ethical leaders conform to a complex code of morals in their personal and professional lives, for example, by exercising fairness and integrity (McCann and Holt 2009). They influence the moral thinking of lower-level employees by demonstrating moral values and behavior in the workplace (Mayer et al. 2009). As a moral manager, ethical leaders create behavioral codes for others. They have good managerial skills in directing employees’ attentions to ethical considerations and infusing employees with principles that guide ethical actions (Mo et al. 2012; Trevino et al. 2000; Toor and Ofori 2009).

Generally, employees tend to emulate such credible role models as they identify them as models for appropriate behavior (Mayer et al. 2012). Ethical leaders value fairness, integrity and people orientation (Kalshoven et al. 2011). Thus, employees working with an ethical leader are more likely to go beyond the call of duty (Bolino and Turnley 2003) and develop stronger identification with both the focal leader and the organization (Walumbwa et al. 2011). In contrast, employees under the supervision of an unethical leader may be less actively involved in the organization and may engage in morally questionable or even immoral behavior (Brown and Mitchell 2010).

Ethical Leadership Enhances Employees’ Trust in Leaders

Generally, leaders have the authority to make decisions that have a significant impact on employees’ abilities to achieve their goals (Bruke et al. 2007). Accordingly, employees are more likely to develop a mutual trust relationship with leaders that are seen to care for their best interests. Trust in leaders refers to a psychological state in which an individual accepts his or her own vulnerability when they have an expectation of positive intentions or behavior of their leaders (Rousseau et al. 1998; Yang and Mossholder 2010). The level of trust in leaders is primarily affected by employees’ views on the quality of leader-member relationships (Blau 1964). Employees may develop a higher level of trust in leaders that keep promises and behave consistently. This is because such ethical leaders typically reward ethical behavior and discipline unethical behavior. They clearly inform employees of what is expected from them and how they can positively contribute to the organization (Kalshoven et al. 2011; Simons 2002). When feeling supported and fairly treated, employees are more likely to trust in the focal leader (cf., De Hoogh and Den Hartog 2008). With a sample of 294 matched leader-employee dyads, Kalshoven et al. (2011) demonstrated that employees’ perceptions of ethical leadership significantly contribute to the employees’ trust in their leaders. Further, employees usually emulate leaders that are widely recognized as being attractive and trustworthy role models (Bandura 1977, 1986; Brown et al. 2005). Accordingly, employees may have a higher level of trust in leaders that are typically deemed legitimate models for normative behavior in their organizations. Using a sample of 87 MBA students, Brown et al. (2005) found that ethical leadership was positively correlated with employees’ affective trust.

Taking these findings together, we propose that employees’ perceptions of ethical leadership may positively enhance the level of trust that employees have in the focal leader.

H1

Ethical leadership is positively related to employees’ trust in leaders.

Ethical Leadership Reduces Employees’ Surface Acting

Surface acting is a dramaturgical performance in which individuals forcefully modify their behavioral displays to create a desirable image in workplace interactions (Hochschild 1983). It shapes the outward appearance of an individual without modifying their inner feelings (Grandey 2003). Ethical leaders may saliently eliminate such surface acting behavior to encourage employees to engage in open communication and to encourage them to express their true emotions (Brown et al. 2005). Thus, under the supervision of an ethical leader, employees may have a more positive attitude and sufficient self-esteem to authentically express their inner feelings in the workplace (Dirks and Ferrin 2002). Moreover, they directly learn from such ethical role models to be open and honest. In contrast, unethical leaders often deliver negative affective signals to employees such that open communication is not welcomed and fairness and justice is not assured in the organization (Brown and Mitchell 2010). In such cases, employees usually suppress their frustration and simply “put on a mask” by displaying feigned emotions toward the focal leader without altering their genuine feelings (Grandey 2003). Moreover, they may even amplify their own negative emotions as a result of displaying false emotions to maintain a positive relationship with the focal leader (Grandey 2003; Groth et al. 2009). Past research has shown that employees are inclined to engage in surface acting from a motivation to seek greater approval from others. They achieve this by engaging in conforming behavior, thereby maintaining interpersonal acceptance in the workplace (Brockner 1988; Ozcelik 2013). Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2

Ethical leadership is negatively related to employees’ surface acting toward leaders.

Trust in Leaders as a Mediator of the Relationship Between Ethical Leadership and Work-Related Outcomes

The conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll 1989) maintains that people strive to obtain, retain, protect and foster valued resources and minimize any threat of resource loss. Employees may experience stress when emotional resources cannot be maintained (Brotheridge and Lee 2002; Halbesleben et al. 2014). Accordingly, we suggest that employees may become psychologically distressed and emotionally upset when they perceive a loss of trust toward their leader. Those negative feelings subsequently lead to long-term exhaustion, diminished interest in work and even workplace deviance (Bechtoldt et al. 2007). In contrast, individuals who receive care and support from their leaders may be at a lesser risk of burnout (Dirks and Ferrin 2002; Kannan-Narasimhan and Lawrence 2012). They are also less likely to engage in deviant activities that are potentially harmful to the organization (Khuntia and Suar 2004; Wu et al. 2011). Furthermore, employees maintaining a trust-based relationship with their leader often have a stronger sense of psychological identification with the organization. Thus, they may have a higher motivation to exert greater effort and achieve better performance in the workplace (Schaubroeck et al. 2013; Wieklund and Gollwitzer 1982). Dirks and colleagues’ (2002) meta-analytic findings indicated that trust in leaders is significantly related to employees’ attitudinal, behavioral and performance outcomes. Therefore, our hypotheses suggest that an employee’s trust in leaders is negatively related to the degree to which they experience burnout and engage in deviant behavior at work and is positively related to their task performance.

H3a

Employees’ trust in leaders is negatively related to experienced burnout.

H3b

Employees’ trust in leaders is negatively related to deviant behavior.

H3c

Employees’ trust in leaders is positively related to task performance.

Under the supervision of ethical leaders, employees are more able to obtain the psychological resources that enable them to develop enhanced trust-based leader-member relationships (Hobfoll 1989; Pearlin et al. 1981; Sharif and Scandura 2013). In such relationships, employees are more likely to feel secure in expressing their inner feelings to the focal leader (Hochschild 1983) and may develop a stronger psychological identification with, and commitment to, the organization (Neves and Story 2015; Walumbwa et al. 2011). Thus, they are less likely to experience burnout and engage in workplace deviance. Past empirical research has demonstrated the importance of the role that trust in leaders plays in achieving effective ethical leadership (e.g., Schaubroeck et al. 2011).

Given our hypotheses of the positive effect of ethical leadership on employees’ trust in leaders (hypothesis 1), the negative relationship between trust in leaders and employee behavior such as burnout and workplace-deviant behavior (hypotheses 3a and 3b) and the positive link between trust in leader and work performance (hypothesis 3c), we expect trust in leaders to mediate the impact of ethical leadership on the level of burnout experienced by employees, employees’ deviant behavior and employees’ task performance. Thus, we propose the following three hypotheses:

H4a

Employees’ trust in leaders mediates the negative relationship between ethical leadership and experienced burnout.

H4b

Employees’ trust in leaders mediates the negative relationship between ethical leadership and deviant behavior.

H4c

Employees’ trust in leaders mediates the positive relationship between ethical leadership and task performance.

Surface Acting as a Mediator of the Relationship Between Ethical Leadership and Employee Outcomes

According to the conservation of resources theory, employees engage in surface acting because they are in a psychological state characterized by a lack of emotional resources, such as self-esteem (Brotheridge and Lee 2002). In such cases, employees experience greater uncertainty about the propriety of their thoughts and feelings (Ozcelik 2013; Halbesleben et al. 2014). To maintain a positive leader-member relationship, employees regulate their emotional expressions to keep their inner feelings from erupting spontaneously or automatically. It has been suggested that employees are most likely to become emotionally burned out in work interactions when there is a large discrepancy between the emotions they express and the emotions they actually feel (Lee and Ashforth 1993; Morris and Feldman 1996). Based on data collected from 478 employees, Ozcelik (2013) demonstrated that surface acting was significantly associated with emotional exhaustion and burnout. Moreover, the loss of psychological resources that is induced by surface acting might trigger further negative emotions toward both the leader and the organization, which could precipitate deviant behavior (Grandey 2003). The results reported in Bechtoldt et al. (2007) indicated that the level of employees’ surface acting was positively associated with deviant behavior at work. Additionally, surface acting may negatively influence individuals’ work performance as they experience reduced cognitive effort and volition (Ozcelik 2013). Empirical evidence has shown that surface acting is significantly associated with undesirable work outcomes, such as increased emotional exhaustion, reduced organizational commitment and poor job performance (Grandey 2003; Groth et al. 2009; Shanock et al. 2013). Hence, we propose the following hypotheses:

H5a

Employees’ surface acting is positively related to experienced burnout.

H5b

Employees’ surface acting is positively related to deviant behavior.

H5c

Employees’ surface acting is negatively related to task performance.

To repeat, employees are more likely to express their genuine inner feelings with a leader who values open communication and people-oriented management, but may express false feelings with a leader they perceive to be unethical. Employees who engage in surface acting may become more anxious and less productive as a result of spending a large proportion of their psychological resources in shaping the image they deem to be preferred and accepted by the leader. Moreover, these employees may imitate and emulate a leader’s unethical behavior, which is harmful to organizational performance (Brown et al. 2005). Thus, we suggest that when a leader demonstrates positive moral values and actions in the workplace, employees are less likely to engage in surface acting. Subsequently, they will achieve lower levels of burnout, engage in reduced deviant behavior and achieve improved task performance.

Given our hypotheses on the effect of ethical leadership on employees’ surface acting toward the leader (Hypothesis 2), the positive relationships between surface acting and both burnout and workplace-deviant behavior (Hypotheses 5a and 5b) and the negative link between surface acting and task performance (hypothesis 5c), we expect surface acting to mediate the effect of ethical leadership on employee experienced burnout, deviant behavior and task performance. Thus, the following hypotheses are suggested:

H6a

Employees’ surface acting mediates the negative relationship between ethical leadership and experienced burnout.

H6b

Employees’ surface acting mediates the negative relationship between ethical leadership and deviant behavior.

H6c

Employees’ surface acting mediates the positive relationship between ethical leadership and task performance.

Methods

Sample and Procedures

Data were collected from employees working in a pharmaceutical retail chain company located in South China. Questionnaires were initially distributed to 255 employees across 45 teams. The employees were informed that their responses would only be used for research purposes and that they would be permitted to complete the questionnaires during work time.

The final sample size comprised 45 teams (45 leaders and 247 employees), giving a response rate of 96.9 %. The average team size was 9.11 members (SD = 9.66). Of the employees, 83 were female (33.5 %), the average age was 27.93 years (SD = 4.21), and the average length of tenure was 15.39 months (SD = 12.68). Respectively, of the leaders, 10 were female (22.2 %), the average age was 38.09 years (SD = 7.01), and the average length of tenure was 36.38 months (SD = 22.31).

Data were collected at two time points with 3 months in between. This interval was deemed sufficient to separate the measurements of the predictors and mediators from the outcome variables (Zhou et al. 2012). At Time 1, employees were asked to report their demographic information, such as age, gender and length of tenure. They were also asked about their perception of ethical leadership in their team. At Time 2, employees reported their levels of trust in leaders, surface acting in interacting with leaders and their experienced burnout, while leaders completed a questionnaire on their demographic information and evaluation of each employee’s deviant behavior and task performance. All responses were translated from English to Chinese, using Brislin’s (1980) recommended translation-back translation procedure.

Measures

Well-established scales were employed to measure the constructs in this study. The specific scales used are summarized below.

Ethical Leadership

Ethical leadership was measured using Brown et al.’s (2005) unidimensional ten-item Ethical Leadership Scale (ELS). Respondents were asked to evaluate their perceptions of ethical leadership by answering statements such as “My leader makes fair and balanced decisions” and “My leader sets an example of how to do things the right way in terms of ethics.” A five-point Likert response format (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) was used. Cronbach’s α was 0.93.

Trust in Leaders

Trust in leaders was measured using the three-item scale developed by McAllister (1995). A typical item in the scale was “I can freely share my ideas, feelings and wishes with my leader.” A five-point Likert response format (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) was adopted. Cronbach’s α was 0.90.

Surface Acting

The scale used to measure surface acting was adapted from Brotheridge and Lee (2002) and Grandey (2003). Five items were included in the scale, such as “I always exteriorly change negative emotions in order to deal with the leader in an appropriate way.” A five-point Likert response format (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) was used. Cronbach’s α was 0.87.

Experienced Burnout

We measured employees’ experienced burnout using a 14-item scale developed by Maslach and Jackson (1981). An example item was “I feel emotionally drained from my work.” We applied a seven-point Likert response format (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree). Cronbach’s α was 0.93.

Deviant Behavior

Deviant behavior was assessed using the ten-item scale developed in Mitchell and Ambrose (2007). An example item in the deviant behavior scale was “This employee made obscene comments or gestures toward me.” A seven-point Likert response format (1 = strongly disagree; 7 = strongly agree) was used. Cronbach’s α was 0.64.

Task Performance

We measured employees’ task performance with the scale used in Cole et al. (1998). Five items were included in this scale, such as “This employee accomplished most of tasks quickly and efficiently.” Leaders were asked to rate these items using a five-point Likert response format (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree). Cronbach’s α was 0.87.

Control Variables

Previous research has noted that the variables team size, employee gender, age and length of tenure might be related to the focal relationships we are examining (Pearce and Herbik 2004). On that basis, we used these four variables as control variables in our hypothesis testing.

Analytic Strategy

Mplus 6.0 software (Muthen and Muthen 2007) was used to test all of the hypotheses in a multilevel framework. In addition, the Monte Carlo method recommended by Preacher et al. (2010) was used to estimate confidence intervals for the hypothesized multilevel mediation effects to determine their significance.Footnote 1 All standard errors of model parameter estimates were computed using a sandwich estimator to correct potential sampling biases that would be caused by unequal numbers of respondents in each team.

Results

The means, standard deviations and bivariate correlations among the variables studied are shown in Table 1. At the individual (employee) level, perceived ethical leadership was positively correlated with trust in leaders (r = 0.50, p < 0.01) and negatively correlated with surface acting (r = −0.13, p < 0.05). Employees’ trust in leaders was negatively correlated with employee experienced burnout (r = −0.48, p < 0.01) and deviant behavior toward the leader (r = −0.22, p < 0.01). In addition, surface acting was positively correlated with experienced burnout (r = 0.32, p < 0.01). These findings provided preliminary support for our hypothesized relationships.

Model Estimation

To estimate the hypothesized model (Fig. 1), we included gender, age and length of tenure as control variables with fixed effects on mediating variables and dependent variables at the individual level. Moreover, we also controlled for the effect of team size on all of the endogenous variables at the team level.

To facilitate the interpretation of the research model, age, gender, length of tenure and team size were all grand mean centered. The results showed that most of the hypothesized relationships were well supported, as shown in Fig. 2 and Table 2.

Hypotheses Testing

Hypotheses Testing of the Main Effects

Perceived ethical leadership was hypothesized to be positively associated with trust in leaders and negatively related to surface acting. Figure 2 shows that ethical leadership was positively related to trust in leaders (β = 1.00, p < 0.01) and negatively related to surface acting (β = −0.21, p < 0.01). These results provide support for hypotheses 1 and 2. Moreover, trust in leaders was negatively related to experienced burnout (β = −0.31, p < 0.01) and deviant behavior (β = −0.02, p < 0.05) and positively related to task performance (β = 0.03, p < 0.05). Thus, hypotheses 3a–3c were well supported. Surface acting was positively related to experienced burnout (β = 0.22, p < 0.01), supporting hypothesis 5a. However, the impacts of surface acting on deviant behavior (β = 0.00, SE = 0.01) and task performance (β = 0.04, SE = 0.03) were not significant. Thus, hypotheses 5b and 5c were not supported.

Hypotheses Testing of the Mediating Effects

Employees’ trust in leaders was hypothesized to mediate the relationships between perceived ethical leadership and experienced burnout, deviant behavior and task performance. We used a parametric bootstrap procedure (cf. Preacher et al. 2010) to estimate the hypothesized indirect relationships between these factors. With 20,000 Monte Carlo replications, the results showed that there were negative indirect relationships between ethical leadership and experienced burnout [indirect effect = −0.31, 90 % bias-corrected bootstrap CI (−0.457, −0.175)], ethical leadership and deviant behavior [indirect effect = −0.02, 90 % bias-corrected bootstrap CI (−0.033, −0.002)] and a positive indirect relationship between ethical leadership and task performance [indirect effect = 0.03, 90 % bias-corrected bootstrap CI (0.009, 0.045)], all mediated by trust in leaders. Therefore, hypotheses 4a–4c were supported. In addition, there was a negative indirect relationship between ethical leadership and experienced burnout via surface acting [indirect effect = −0.04, 90 % bias-corrected bootstrap CI (−0.092, −0.008)], which provides support for hypothesis 6a.

Discussion

There is an increasing recognition of the value of ethical leadership in managing employees in the workplace. However, despite this recognition, the psychological mechanisms that link ethical leadership to employee work-related outcomes have seldom been examined in the existing literature (Mayer et al. 2012; Walumbwa et al. 2011). This study is a response to those calls for a better understanding of the underlying psychological mechanisms that are affected by ethical leadership at the individual level. Specifically, we found that the relationships between ethical leadership and employees’ work outcomes (i.e., burnout, deviant behavior and task performance) were significantly mediated by trust in leaders. Moreover, surface acting was found to be a mediator of the relationship between ethical leadership and experienced burnout, but its mediating effect was not found to be significant in linking ethical leadership to deviant behavior or work performance. A reason for these findings may be that surface acting primarily reflects employees’ negative attitudes of fear and conformity, which are, in turn, typically rooted in employees’ personal motives to maintain interpersonal acceptance (Grandey 2003; Ozcelik 2013). Instead, surface acting is more strongly associated with individuals’ emotional outcomes such as burnout.

Theoretical Implications

These findings have several implications for the theory of ethical leadership. First, this study offers an important contribution to the ethical leadership literature by demonstrating the value of ethical leadership in managing employees’ negative attitudes and behavior in the workplace. As it encompasses two-way communication and reinforcement of appropriate behavior, ethical leadership can promote the ethical actions of employees and prevent unethical emotions and behavior (Brown et al. 2005). The literature has emphasized the importance of ethical leadership in cultivating positive attitudes and behavior, such as organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior, and its importance in achieving higher levels of work performance (Kalshoven et al. 2011; Neubert and Roberts 2013). However, less attention has been paid to the value of ethical leadership in reducing negative attitudes and behavior, which are frequently observed in the workplace. Responding to this gap in the current research, our study enriches the existing literature by providing a greater understanding of the value of ethical leadership in reducing employee burnout and deviant behavior. The value of these findings is upheld by the fact that they were obtained through a rigorous examination of the relationships between ethical leadership and employee work performance by using a time-lagged experimental design and by collecting data from multiple sources.

Second, this study integrates the ethical leadership literature with the conservation of resources theory. Responding to previous calls in the literature for an examination of the underlying mechanisms that link ethical leadership to employee work outcomes (Kalshoven et al. 2011), this research identified two distinct but complementary employee-focused variables—trust in leaders and surface acting—which have been shown to link ethical leadership to employee work outcomes. From a conservation of resources perspective, our results show that higher levels of perceived ethical leadership may allow employees access to more psychological resources such as higher levels of trust in leaders and greater authenticity of interactions with the leader, thereby leading to less negative behavior and better work performance.

Managerial Implications

This study also makes several important practical implications. First, our findings suggest that ethical leadership has a salient impact on employees’ negative attitudes and behavior. Hence, it is important for organizations to identify, select and promote people who demonstrate desirable ethical values as leaders. Alternatively, organizations may opt to invest in ethics training programs for existing leaders to improve their moral reasoning and ethical behavior.

Second, it is important for leaders to pay attention to issues such as the extent to which they are trusted by employees and the extent to which employees feel able to express their inner feelings. Leaders are encouraged to cooperate with employees honestly and openly, and beyond the smile that is “just painted on” (Hochschild 1983). When employees do not have self-esteem and trust in their leader, or they fear to communicate openly with the leader, it can result in various negative emotions and behavior in the group or organization. Consequently, a leader can only be successful when employees genuinely trust him or her and cooperate in an open manner. Therefore, it is recommended that leaders commit to creating an ethical climate that emphasizes interpersonal trust and open communication in the workplace.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has a number of limitations. First, both mediators (trust in leaders and surface acting) and employees’ experienced burnout were measured from the same source at the same time. As it was not possible to measure these variables at different times because of logistical constraints, we examined the factor structure of the measures and confirmed the distinction between these three constructs. Nevertheless, we suggest that future research verifies our empirical results with a more rigorous research design.

Second, in the current study, ethical leadership was conceptualized and operationalized as a unidimensional concept using Brown et al.’s (2005) definition. In future research, it would be beneficial to examine the relationships between distinct dimensions of ethical leadership and individuals’ attitudes and behavior (e.g., De Hoogh and Den Hartog 2008; Kalshoven et al. 2011). For instance, leaders’ integrity and fairness are more likely to be associated with employees’ trust in leaders, while people-orientation behavior may lead to employees’ open communication and organizational citizenship behavior (Kalshoven et al. 2011). Thus, we encourage future research to adopt a multidimensional approach to investigate the extent to which ethical leadership explains variance in employees’ work attitudes and outcomes.

Notes

More information about the R program can be found at http://www.quantpsy.org.

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Bechtoldt, M. N., Welk, C., Zapf, D., & Hartig, J. (2007). Main and moderating effects of self-control, organizational justice, and emotional labour on counterproductive behaviour at work. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 16(4), 479–500.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York: Wiley.

Bolino, M. C., & Turnley, W. H. (2003). Going the extra mile: Cultivating and managing employee citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Executive, 17, 60–82.

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written material. In H. C. Triandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (pp. 398–444). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Brockner, J. (1988). The effect of work layoffs on survivors: Research theory and practice. In B. M. Staw, & L. L. Cummings (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior (Vol. 10, pp. 213–255). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

Brotheridge, C. M., & Lee, R. (2002). Testing a conservation of resources model of the dynamics of emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7, 57–67.

Brown, M. E. (2007). Misconceptions of ethical leadership: How to avoid potential pitfalls. Organizational Dynamics, 36, 140–155.

Brown, M. E., & Mitchell, M. S. (2010). Ethical and unethical leadership: Exploring new avenues for future research. Business Ethics Quarterly, 20, 583–616.

Brown, M. E., & Trevino, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17, 595–616.

Brown, M. E., Trevino, L. K., & Harrison, D. A. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97, 117–134.

Bruke, C. S., Sims, D. E., Lazzara, E. H., & Salas, E. (2007). Trust in leadership: A multi-level review and integration. The Leadership Quarterly, 18, 606–632.

Cole, M. S., Walter, F., & Bruch, H. (1998). Affective mechanisms linking dysfunctional behavior to performance in work teams: A moderated mediation study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 945–958.

De Hoogh, A. H. B., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2008). Ethical and despotic leadership, relationships with leader’s social responsibility, top management team effectiveness and subordinates’ optimism: A multi-method study. Leadership Quarterly, 19, 297–311.

Dirks, K. T., & Ferrin, D. L. (2002). Trust in leadership: Meta-Analytic findings and implications for research and practice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 611–628.

Grandey, A. A. (2003). When “the show must go on”: Surface acting and deep acting as determinants of emotional exhaustion and peer-rated service delivery. Academy of Management Journal, 46, 86–96.

Groth, M., Hennig-Thurau, T., & Walsh, G. (2009). Customer reactions to emotional labor: The roles of employee acting strategies and customer detection accuracy. Academy of Management Journal, 52, 958–974.

Halbesleben, J. R. B., Neveu, J. P., Paustian-Underdahl, S. C., & Westman, M. (2014). Getting to the “COR”: Understanding the roles of resources in conservation of resources theory. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1334–1364.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44, 513–514.

Hochschild, A. R. (1983). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kalshoven, K., Den Hartog, D. N., & De Hoogh, A. H. B. (2011). Ethical leadership at work questionnaire (ELW): Development and validation of a multidimensional measure. The Leadership Quarterly, 22, 51–69.

Kannan-Narasimhan, R., & Lawrence, B. S. (2012). Behavioral integrity: How leader referents and trust matter to workplace outcomes. Journal of Business Ethics, 111, 165–178.

Khuntia, R., & Suar, D. (2004). Leadership of Indian private and public sector managers. Journal of Business Ethics, 49, 13–26.

Lee, R., & Ashforth, B. E. (1993). A further examination of managerial burnout: Toward an integrated model: Summary. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 14(1), 3–20.

Liao, H., Joshi, A., & Chuang, A. (2004). Sticking out like a sore thumb: Employee dissimilarity and deviance at work. Personnel Psychology, 57, 969–1000.

Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. E. (1981). The measurement of experienced burnout. Journal of Occupational Behavior, 2, 99–113.

Mayer, D. M., Aquino, K., Greenbaum, R. L., & Kuenzi, M. (2012). Who displays ethical leadership, and why does it matter? An examination of antecedents and consequences of ethical leadership. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 151–171.

Mayer, D. M., Kuenzi, M., & Greenbaum, R. L. (2010). Examining the link between ethical leadership and employee misconduct: The mediating role of ethical climate. Journal of Business Ethics, 95, 7–16.

Mayer, D. M., Kuenzi, M., Greenbaum, R., Bardes, M., & Salvador, R. B. (2009). How low does ethical leadership flow? Test of a trickle-down model. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 108, 1–13.

McAllister, D. J. (1995). Affect- and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 24–59.

McCann, J., & Holt, R. (2009). Ethical leadership and organizations: An analysis of leadership in the manufacturing industry based on the perceived leadership integrity scale. Journal of Business Ethics, 87, 211–220.

Mitchell, M. S., & Ambrose, M. L. (2007). Abusive supervision and workplace deviance and the moderating effects of negative reciprocity beliefs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 1159–1168.

Mo, S. J., Wang, Z. M., Akrivou, K., & Booth, S. (2012). Look up, look around: Is there anything different about team-level OCB in China? Journal of Management & Organization, 18, 833–844.

Morris, J. A., & Feldman, D. C. (1996). The dimensions, antecedents, and consequences of emotional labor. Academy of Management Review, 21, 986–1010.

Mulki, J. P., Jaramillo, F., & Locander, W. B. (2006). Emotional exhaustion and organizational deviance: Can the right job and a leader’s style make a difference? Journal of Business Research, 59, 1222–1230.

Muthen, L. K., & Muthen, B. O. (2007). Mplus user’s guide (5th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Author.

Neubert, M. J., Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., Roberts, J. A., & Chonko, L. B. (2009). The virtuous influence of ethical leadership behavior: Evidence from the field. Journal of Business Ethics, 90, 157–170.

Neubert, M. J., & Roberts, J. A. (2013). The influence of ethical leadership and regulatory focus on employee outcomes. Business Ethics Quarterly, 23, 269–296.

Neves, P., & Story, J. (2015). Ethical leadership and reputation: Combined indirect effects on organizational deviance. Journal of Business Ethics, 127(1), 165–176.

Ozcelik, H. (2013). An empirical analysis of surface acting in intra-organizational relationships. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34, 291–309.

Pearce, C. L., & Herbik, P. A. (2004). Citizenship behavior at the team level of analysis: The effects of team leadership, team commitment, perceived team support, and team size. The Journal of Social Psychology, 144, 293–310.

Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J., & Zhang, Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15, 209–233.

Resick, C. J., Hargis, M. B., Shao, P., & Dust, S. B. (2013). Ethical leadership, moral equity judgments, and discretionary workplace behavior. Human Relations. doi:10.1007/s10551-013-1869-x.

Robinson, S. L., & Bennett, R. J. (1995). A typology of deviant workplace behaviors: A multidimensional scaling study. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 555–572.

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., & Camerer, C. (1998). Not so different after all: A cross-discipline view of trust. Academy of Management Review, 23, 393–404.

Schaubroeck, J. M., Hannah, S. T., Avolio, B. J., Kozlowski, S. J., Lord, R. G., Trevino, L. K., et al. (2012). Embedding ethical leadership within and across organizational levels. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 1053–1078.

Schaubroeck, J. M., Lam, S. S., & Peng, A. C. (2011). Cognition-based and affect-based trust as mediators of leader behavior influences on team performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96, 863–871.

Schaubroeck, J. M., Peng, A. C., & Hannah, S. T. (2013). Developing trust with peers and leaders: Impacts on organizational identification and performance during entry. Academy of Management Journal, 56, 1148–1168.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 293–315.

Shanock, L. R., Allen, J. A., Dunn, A. M., Baran, B. E., Scott, C. W., & Rogelberg, S. G. (2013). Less acting, more doing: How surface acting relates to perceived meeting effectiveness and other employee outcomes. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86, 457–476.

Sharif, M. M., & Scandura, T. A. (2013). Do perceptions of ethical conduct matter during organizational change? Ethical leadership and employee involvement. Journal of Business Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-013-1869-x.

Simons, T. (2002). Behavioral integrity: The perceived alignment between managers’ word and deeds as a research focus. Organizational Science, 13, 18–35.

Taylor, S. G., & Pattie, M. W. (2014). When does ethical leadership affect workplace incivility? The moderating role of follower personality. Business Ethics Quarterly, 24(4), 595–616.

Toor, S. R., & Ofori, G. (2009). Ethical leadership: Examining the relationships with full range leadership model, employee outcomes, and organizational culture. Journal of Business Ethics, 90, 533–547.

Trevino, L. K., Brown, M., & Hartman, L. P. (2003). A qualitative investigation of perceived executive ethical leadership: Perceptions from inside and outside the executive suite. Human Relations, 56, 5–37.

Trevino, L. K., Hartman, L. P., & Brown, M. (2000). Moral person and moral manager: How executives develop a reputation for ethical leadership. California Management Review, 42, 128–142.

Walumbwa, F. O., Mayer, D. M., Wang, P., Wang, H., Workman, K., & Christensen, A. L. (2011). Linking ethical leadership to employee performance: The roles of leader–member exchange, self-efficacy, and organizational identification. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 115, 204–213.

Wieklund, R. A., & Gollwitzer, P. M. (1982). Symbolic self-completion. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Wu, M., Huang, X., Li, C., & Liu, W. (2011). Perceived interactional justice and trust-in-supervisors as mediators for paternalistic leadership. Management and Organization Review, 8, 97–121.

Yang, J., & Mossholder, K. W. (2010). Examining the effects of trust in leaders: A bases-and-foci approach. The Leadership Quarterly, 21, 50–63.

Zhou, L., Wang, M., Chen, G., & Shi, J. (2012). Supervisors’ upward exchange relationships and subordinate outcomes: Testing the multilevel mediation role of empowerment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97, 668–680.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by Grant No. 71425004 awarded to Junqi Shi and Grant No. 71302102 awarded to Shenjiang Mo from the Natural Social Science Foundation of China, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, and grant no. NCET-13-0611 awarded to Junqi Shi from the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mo, S., Shi, J. Linking Ethical Leadership to Employee Burnout, Workplace Deviance and Performance: Testing the Mediating Roles of Trust in Leader and Surface Acting. J Bus Ethics 144, 293–303 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2821-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2821-z