Abstract

Behavioral ethics research has focused predominantly on how the attributes of individuals influence their ethicality. Relatively neglected has been how macro-level factors such as the behavior of firms influence members’ ethicality. Researchers have noted specifically that we know little about how a firm’s CSR influences members’ behaviors. We seek to better merge these literatures and gain a deeper understanding of the role macro-level influences have on manager’s ethicality. Based on agency theory and social identity theory, we hypothesize that a company’s commitment to CSR shifts managers’ focus away from self-interests toward the interests of the firm, bolstering resistance to temptation. We propose this occurs through self-categorization and collective identification processes. We conduct a 2 × 2 factorial experiment in which managers make expense decisions for a company with commitment to CSR either present or absent, and temptation either present or absent. Results indicate that under temptation, managers make decisions consistent with self-interest. More importantly, we find when commitment to CSR is present, managers are more likely to make ethical decisions in the presence of temptation. Overall, this research highlights the interactive role of two key contextual factors—temptation and firm CSR commitment—in influencing managers’ ethical decisions. While limited research has highlighted the positive effects that a firm’s CSR has on its employees’ attitudes, the current results demonstrate CSR’s effects on ethical behavior and imply that through conducting and communicating its CSR efforts internally, firms can in part limit the deleterious effects of temptation on managers’ decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

With their control or influence over firms’ resources, managers’ unethical behavior can cause serious damage to organizations and potentially undermine the credibility of the financial system. The Association for Certified Fraud Examiners estimates that organizations lose approximately 5% of their annual revenues to various types of unethical behavior (e.g., asset misappropriation, corruption) (ACFE 2016). Several ethical failures involving international corporate scandals (e.g., Enron, VW, WorldCom) have resulted in major organizational and societal harm. Numerous studies on ethical judgment and decision-making have investigated the antecedent and mitigating factors underlying such unethical behavior in organizations (see Treviño et al. 2014 for review).

Yet, consistent with the common tendency to over-ascribe the cause of behavior to individual actors (i.e., the fundamental attribution error, Jones 1990; Ross 1977), the extant canon of research has focused largely on how individual factors such as moral awareness, values, moral identity, ethical ideology, cognitive moral development, etc. influence ethical decisions and behaviors (see Jennings et al. 2015; Tenbrunsel and Smith-Crowe 2008; Treviño et al. 2014 for reviews). Indeed, there seems to be a proclivity to ascribe self-interested motives as the cause of unethical actions, such as the scandals surrounding the 2008 financial crisis (Gino et al. 2011; McLean and Nocera 2010).

However, Treviño and Youngblood (1990) have highlighted the need for the field to not only advance micro-level theory and research concerning “bad apples” but also meso- and macro-level research on “bad barrels” to better understand the conditions promoting (un)ethical behaviors in organizations. Empirical research has in response begun to assess how meso-level factors such as ethical leadership and group processes (e.g., Brown et al. 2005; Schminke and Wells 1999), and macro-factors such as ethical culture or climate (Arnaud and Schminke 2012; Schaubroeck et al. 2012) influence members’ ethicality in firms. Yet, beyond that concerning ethical culture and climate, there remains a dearth of theory and research on how firm-level macro-phenomenon, such as the behaviors of firms themselves, influence individual ethicality. This has left an incomplete understanding of the contextual forces causing deleterious unethical actions in firms, such as self-serving manager actions prompting the scandals mentioned above.

To begin to fill this gap in the macro-level behavioral ethics literature, emerging research has sought to investigate whether the behavior of firms reflected in their CSR activities positively influences the ethical attitudes and behaviors of their own members (e.g., El Akremi et al. 2015; Rupp et al. 2006; Rupp et al. 2013).Footnote 1 This emerging research asks whether, how, and under what conditions, does a firm’s “doing good” promote members to also do good and restrain from unethical acts. This nascent research sets apart from the plethora of studies that have focused on how firms’ CSR affects outcomes at the organizational level of analysis (Aguinis and Glavas 2012; Barnett and Salomon 2012; Gregory et al. 2014; Harjoto and Jo 2015). Indeed, Aguinis and Glavas (2012) note that less than 4% of CSR research has focused on its effects on employees. Thus, as noted by Rupp et al. (2013), a gap continues to exist in the literature for research aimed at examining “how employees perceive and subsequently react to acts of CSR” (p. 896) (cf Morgeson et al. 2013).

The study of the effects and experiences of CSR on individuals is referred to as “micro-CSR” (Rupp and Mallory 2015, p. 216). Most of the micro-CSR work has focused on its effects on positive workplace attitudes. For example, prior studies focus on the effect of employees’ CSR perceptions on constructs such as organizational support (El Akremi et al. 2015), job pursuit intentions (Rupp et al. 2013), organizational commitment (Erdogan et al. 2015), organizational justice (Rupp et al. 2006), and job satisfaction (Dhanesh 2014), among others. Research on the effects of CSR activities on individuals’ behavioral outcomes is very limited, however, with recent studies highlighting a positive influence of CSR on employee creativity (Spanjol et al. 2015), knowledge sharing (Farooq et al. 2014), and employee retention (Carnahan et al. 2016). We advance this line of research to investigate the effects of CSR on ethical behavior.

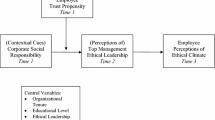

While much of the micro-CSR literature employs social identity theory, signaling theory, and social exchange theory to explain individuals’ reactions to CSR (see Gond et al. 2017 for a review), the current study seeks to advance this literature from a theoretical standpoint by employing agency theory and social identity theory (SIT) together to describe why managers would be more inclined to act as agents and conduct themselves in ways most advantageous to the firm. In this way, we respond to calls for a better understanding of how theoretical mechanisms interact to produce CSR-related outcomes (Gond et al. 2017) and to go beyond investigating self-interest as the focused driver of ethical decision-making (Kish-Gephart et al. 2014). Specifically, consistent with prior research utilizing agency theory (Cianci et al. 2014), we conceptualize temptation as incentives and opportunity to behave unethically to obtain rewards (i.e., maximize self-interest) rather than to act ethically as an agent of the principal/firm (i.e., maximize the principal or firm interest). We then rely on SIT to contend that firm CSR commitment will lead managers to make more ethical decisions when confronted with temptation by broadening managers’ focus from self-interested motives to those of the esteemed firm’s various stakeholder groups (Aguilera et al. 2007; Heal 2005). That is, according to SIT, individuals seek self-enhancement (Alicke and Govorun 2005; Sedikides et al. 2004) and thus tend to self-categorize with esteemed groups and organizations, leading them to identify and align with these groups and their norms (Hogg and Terry 2000). Applying SIT to the current setting, we suggest that a company engaged in CSR activities is likely to be perceived as socially desirable and esteemed, promoting its managers to eschew self-interest and instead act in accordance with, and experience self-enhancement from aligning with, firm interests. We thus report on our experimental examination of the moderating effect of a firm’s CSR commitment on the relationship between temptation and managers’ ethical decisions. A conceptual model is provided in Fig. 1.

Our secondary contribution is empirical. Critically needed at this early point of development in the emerging research area of the effect of CSR activities on individuals’ behavioral outcomes are true experiments that begin to evidence causal relationships between firms’ CSR and members’ ethical actions, and that identify the boundary conditions under which such effects occur. To our knowledge, our study is the first to use a scenario-based experiment to identify how CSR influences managers’ “in-role performance”—i.e., managers’ responding to an experimental formal role task similar to what they might encounter in their professional environments (Gond et al. 2017, p. 234). Additionally, Gond et al. (2017) note that previous research focuses on how CSR produces positive or attitudinal workplace outcomes, rather than the role of CSR in relation to potentially negative workplace behaviors such as the temptation-influenced expense reporting scenario faced by managers in our experimental setting. Further, we assess through a causally interpretable design whether a firm’s CSR affects individual, and in particular, managers’ ethical decisions. This is particularly important as studies of reactions to CSR have focused primarily on employees, and “relatively little is known as to whether managers and executives react distinctively to CSR” (Gond et al. 2017).

The current study thus responds to calls to examine how CSR influences individuals’ decisions (Aguinis and Glavas 2012) by providing empirical evidence that the tendency of managers to act in their self-interest is mitigated by their firm’s commitment to CSR. Specifically, while prior research has considered the influence of individual level factors (e.g., moral reasoning, moral disengagement) as possible moderators of temptation-related effects of individual behavior (e.g., Kish-Gephart et al. 2014), we demonstrate that a macro-level factor, firm commitment to CSR, serves as an important buffer of the effects of temptation on managers’ unethical behavior.

Finally, the current research should also inform practice, by shedding light on factors that influence managers’ tendencies to act for or against their self (vs. their firm’s) interests. We inform firms of the boundary condition CSR may impose on the effects of incentives on managers’ (un)ethical decisions. These findings inform whether senior management in high-CSR firms can employ incentive contracts to positively motivate managers’ performance, while tempering the negative effects of the resulting temptation (i.e., opportunity and incentive) on unethical behavior (Kish-Gephart et al. 2014; Moore and Lowenstein 2004). CSR may promote managers to seek performance outcomes without stepping over the line into unethical behavior.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. The next section discusses the background literature and develops hypotheses. This is followed by a description of the research method and a presentation of the results. The final section offers conclusions and theoretical and practical implications.

Theory and Hypotheses Development

Temptation and (Un)Ethical Decision Making (Hypotheses 1a and 1b)

Self-interest is a powerful source of human motivation (Kish-Gephart et al. 2014; Moore and Lowenstein 2004). Temptation, a key driver of self-interested behavior, has been defined as an “enticement to do wrong by promise of pleasure or gain” (Tenbrunsel 1998, p. 332) and as incentives to make unethical decisions to obtain goals or rewards (e.g., Cianci et al. 2014; Fischbach and Shah 2006; Freitas et al. 2002). In the current study, we employ agency theory (Eisenhardt 1989; Jensen and Meckling 1976) to conceptualize temptation as the presence of two conditions—i.e., incentive and opportunity to behave unethically to obtain rewards (e.g., Fischbach and Shah 2006; Freitas et al. 2002; Tenbrunsel 1998). Agency theory provides a framework to examine how the conflicting incentives arising between the principal (i.e., firm) and agent (i.e., manager) impacts whether the agent chooses to act unethically, in self-interest, or in the interest of the principal they are obliged through employment contract to serve (Eisenhardt 1989; Jensen and Meckling 1976). Consistent with prior research (Ariely 2012), we view self-interested decision making as less ethical than decisions made in the interest of the firm the manager is obliged to serve.

According to agency theory, when the goals of the principal-firm and agent-manager are aligned, the agent will tend to make decisions that maximize the goals of the firm, but when the principal and agent goals are misaligned, the agent-manager will be tempted to neglect the principal-firm’s interests in favor of his or her own (Eisenhardt 1989; Jensen and Meckling 1976). All else being equal, a manager in the presence of temptation (i.e., both incentive and opportunity to act for personal gain) is more likely to make decisions that are consistent with his/her self-interest even if counter to the profit-maximizing interests of the firm. For example, research has shown that when managers have both the incentive and opportunity to act in their self-interest, their project continuation and system implementation decisions reflect self-interest (e.g., reputation preservation and/or enhancement) at the expense of the interests of the firm (e.g., Cianci et al. 2014; Harrison and Harrell 1993). These studies find that managers under temptation—i.e., with self-interested (i.e., promotion or reward prospects) incentives and with superiors who do not have enough information to properly determine whether the manager is acting unethically or not (i.e., opportunity)—will be more likely to make less ethical decisions. Based on agency theory and this prior research, we expect, all else being equal, that managers will make less (more) ethical decisions in the presence (absence) of temptation.

H1a

When temptation is present, managers will make less ethical decisions/act in self-interest.

H1b

When temptation is absent, managers will make more ethical decisions/act in service to the firm.

Corporate CSR Commitment

CSR is defined as a company’s strategic response to inconsistencies that occur between profitability goals and social goals (Heal 2005). Being socially responsible at the organizational level involves actions such as allocating resources to the proper enforcement of laws (e.g., those that protect the environment, or the health, safety and equal treatment of workers) (Clarkson 1995; Harding 2005). However, it also involves voluntary actions that go beyond those required by law, such as involvement in community, and philanthropic initiatives (McWilliams and Siegel 2001; Special Report: Corporate Social Responsibility 2005). For example, Levi Strauss proactively ensures that working conditions and wages are reasonable throughout its supply chain rather than just meeting local country legal requirements (Heal 2005). There may also be ethical or humanitarian aspects of CSR (Clarkson 1995; Special Report: Corporate Social Responsibility 2005). For instance, when Merck did not get governmental support for the distribution of a drug that cured river blindness in tropical Africa, the company decided to incur all costs internally to supply and distribute the drug to some 30 million people (Heal 2005).

In addition to being a strategic response to the inconsistencies that arise between profits and social goals, the degree of commitment to CSR is a reflection of an organization’s values and culture and its strategic focus and purpose (Aguilera et al. 2007; Schein 2004; Treviño 1986). Thus, when a company demonstrates a commitment to CSR, it signals to internal and external parties that the firm cares about its stakeholders and means to do well on their behalf (Aguinis and Glavas 2012; Clarkson 1995). Rupp et al. (2006) suggested that once employees assess that their employer is socially responsible, their attitudes and behaviors will be positively impacted, which may lead employees’ to focus beyond self-interest to instead support stakeholder goals and the firm’s interests. Below we hypothesize the basis for this greater inclination to serve the firm, and therefore, why CSR will bolster managers’ ability to resist temptation and eschew self-interest to act with agency in the interest of the firm. As such, the moderating effects of CSR may create a boundary condition, tempering the effects of temptation on managers’ unethical behavior.

The Moderating Effect of CSR Commitment on Temptation (Hypotheses 2a and 2b)

While our theorizing employs agency theory, we also apply social identity theory (SIT)—and more specifically, self-enhancement motives and self-categorization aspects of SIT—to describe why managers would be more inclined to act as agents and conduct themselves in ways most advantageous to the firm. A person’s decision to behave unethically typically requires consideration of two opposing goals—i.e., maximizing self-interest versus maintaining a positive moral self-image and public image (Ariely 2012). People are in general highly motivated to maintain a sense of self-worth and will therefore employ significant effort to promote a positive image (i.e., self-enhancement) and prevent a negative image (i.e., self-protection) (Alicke and Govorun 2005; Sedikides et al. 2004). They do so not only to project a positive image to others, but to also maintain a private approving opinion of oneself (Greenwald and Breckler 1985; Schlenker and Weigold 1992).

According to SIT, due to their desire for self-enhancement (Alicke and Govorun 2005; Sedikides et al. 2004), individuals tend to self-categorize themselves through their membership in esteemed groups and organizations. This promotes them to assimilate their identity and behaviors to align with those of the group and its norms so that they can bask in the positive regard and esteem of the group relative to “lesser” out-groups (Hogg and Terry 2000). Thus, in this way, an organization with a positive reputation may become an important dimension of one’s identity (Ashford and Mael 1989; Dutton et al. 1994; Maignan and Ferrell 2001). According to SIT, this occurs because individuals can define themselves not only in terms of their own self-identity (the individual self), but also through interpersonal identities they form with others such as friends, coworkers, or a leader (the relational self); and/or social identity they form with groups or organizations (the collective self) (Breckler and Greenwald 1986; Brewer and Gardner 1996; Greenwald and Breckler 1985). These levels of identity are malleable (Johnson et al. 2006) and when made salient, collective identities promote decisions and behaviors in favor of the group (Hogg et al. 1995; Kreiner et al. 2006).

Importantly, while individuals may have a disposition toward one of the three levels of identity over others, a given level can be activated through contextual cues and primes (Johnson et al. 2006). Brewer and Gardner (1996) document that, by priming the collective identity, the individual defines himself/herself in terms of the broader social group and shifts focus away from self-interest (which is based on one’s individual identity) toward group-interest (which is based on social identity). Thus, when salient, collective identities focus on the shared norms and “we-ness” of the group (Albert et al. 2000; Alvesson 2002; Cerulo 1997; Wiesenfeld et al. 1999), and heighten sensitivity to group-related information, including organizational values and beliefs (Haslam et al. 2006; Turner et al. 1987). We propose that a firm’s CSR activities will be one important source of activating such collective identities and subsequent organization-supporting behavior.

Self-enhancement thus stems not only from one’s own actions and accomplishments, but through the affiliations held with esteemed others or collectives that bolster a sense of self-worth (Tesser and Campbell 1982). This phenomenon has been referred to as “basking in reflected glory,” whereby individuals feel self-enhanced through affiliated groups or organizations that achieve significant accomplishments or are highly socially esteemed (Cialdini et al. 1976). Individuals are thus drawn to and more highly identify with such esteemed groups, and they seek to support and represent those groups in a positive manner so as to not tarnish the group’s, and thereby their own, image and esteem (Cialdini and Richardson 1980; Snyder et al. 1986).

Applying SIT to the current setting, we suggest that a company engaged in CSR activities is likely to be perceived as socially desirable and esteemed, promoting managers to self-categorize with and experience self-enhancement from their affiliation. Indeed, firms that conduct high levels of CSR promote public accolades and external and internal attributions of social worthiness (Aguinis and Glavas 2012; Orlitzky et al. 2003) and therefore CSR commitment should generally enhance an organization’s reputation and perceived status (e.g., Hess et al. 2002; Morsing and Roepstorff 2015; Wang and Berens 2015). This enhanced status associated with corporate CSR commitment should stimulate managers’ self-enhancement and the self-categorization of their identity with that of the firm. As described in the logic above, this collective self-construal and “we-ness” orientation should promote managers to behave in ways that support the collective and its ideals because, through self-categorization with a group, a member “cognitively assimilates self to the in-group prototype and, thus, depersonalizes self-conception… [bringing]…self-perception and behavior in line with the contextually relevant in-group prototype” (Hogg and Terry 2000, p. 123).

We thus contend that a company’s CSR commitment will serve to broaden managers’ focus from self-interested motives to better align with those of the firm and its stakeholder groups (Aguilera et al. 2007; Heal 2005). This better alignment would lead managers to make more ethical decisions when confronted with temptation. Consistent with this notion, firms high in CSR are known to have higher levels of employee engagement, retention, and commitment, among other desirable outcomes (Aguinis and Glavas 2012).Footnote 2 Also consistent with our logic, Viswesvaran et al. (1998) document the negative link between CSR and employees’ counterproductive behaviors; and Maignan et al. (1999) show that market-oriented and humanistic cultures lead to proactive corporate citizenship, which is in turn associated with higher levels of employee commitment, customer loyalty, and business performance.

To summarize, we argue that firm CSR commitment and actions will provide social identification influences that prompt managers (agents) to align their behavior with that of the collective (principal). This would temper the otherwise negative effects of temptation on unethical behavior that we specified in Hypothesis 1, creating a boundary condition. However, when no temptation is present, agency theory suggests that managers will typically naturally align their actions in benefit of the principal, as they have little reason to risk doing otherwise (Eisenhardt 1989). Absent a potential self-interested reward, there is no reason for managers to risk acting counter to the principal’s interest and desires. Thus, when not faced with temptation, a company’s level of commitment to CSR should not significantly influence managers’ ethical decision-making. Thus, we propose the following hypotheses:

H2a

When temptation is present, managers will be more likely to make ethical decisions/act in service to the firm when firm commitment to CSR is present as opposed to absent.

H2b

When temptation is absent, a firm’s commitment to CSR (whether present or absent) will not influence managers’ ethical decisions.

Research Method

Participants

Participants were 112 managers with significant professional experience enrolled in executive MBA programs at four large urban universities in the U.S. Managers with current or prior experience at publicly traded companies and extensive familiarity with recording expenses were chosen to serve as participants because our study’s scenario involves a hypothetical firm about to execute an initial public offering (IPO) of stock and, in their corporate environments, managers are often relied upon to make judgments relating to operating activities, including the reporting of expenses.Footnote 3 Further, in addition to consulting extensively with Fortune 500 managers during the instrument development phase, we also interviewed these Fortune 500 managers, who noted that they regularly rely on operating managers to make expense estimates.

Participants had a mean 11.03 years (SD 4.97) of professional work experience (“How many years of professional work experience do you have?”), and indicated substantial familiarity with the task of recording expenses (mean 8.09, SD 1.42; “Indicate your familiarity with the concept of recording expenses for services provided to a company but not yet billed:”) and experience in budgeting (mean 7.48, SD 2.32; “Indicate how experienced you are with meeting a pre-determined expense budget or combined revenue and expense budget:”) (both items were rated on a ten-point scale in which 1 represents “not at all familiar” and 10 represents “very familiar”).

Procedure and Task

Participants were provided with a case that placed them in the role of plant manager for a manufacturing firm. Case materials contained company background information (“Appendix 1”, Panel A), a schedule of unbilled consulting and advisory projects that are in process (“Appendix 1”, Panel B), the task objective, and a post-experimental questionnaire. The background and task objective sections provided information on the company and the experimental task. Specifically, the participants were told to assume they were the plant manager for a manufacturing company and that the company planned to execute an initial public offering (IPO) of its stock within the next 3 months. Participants were told that, because of the pending IPO, the company was committed to controlling costs in order to help with the company’s attractiveness in the IPO market. Incorporating an IPO scenario into the case materials helps establish incentives for aggressive reporting other than those driven by meeting financial targets for bonus purposes. Participants were informed that they did not own any company stock, nor would they be issued any shares when the IPO was executed. This ensured that there was no alignment of interest between the operating manager and the company due to equity compensation as a result of individual bonus incentives.

Participants were asked to consider a year-end expense decision relating to consulting that is in process, but for which no billing has yet occurred. Each participant was given the same schedule of services provided by vendors, along with project status information and estimated contract amounts (see “Appendix 1”, Panel B). The project status for each vendor was described as in the “early stages,” with estimated completion dates that indicate the projects are expected to be finished within 1 year of their start dates. The uncertainty surrounding the project completion date is typical of situations in which managers utilize discretion when making expense reporting decisions. The total estimated contractual value for these services is $3.0 million. Participants then indicated their expense recommendation regarding consulting and advisory services that have not yet been billed.

Dependent and Independent Variables

Our primary dependent variable is the dollar amount of managers’ consulting and advisory services expense estimate. Specifically, participants were asked: “How much do you recommend be recorded for consulting and advisory services for which you have not yet been billed?” Participants had the option of recommending that no expenses be recorded in the current reporting period for these services (i.e., $0 recommendation) up to the total $3.0 Million. Two independent variables (temptation and corporate social responsibility) were manipulated, based on random assignment, between participants, creating a 2 × 2 complete factorial design.

The first independent variable, temptation, relates to managers’ incentive (i.e., bonus structure) and opportunity (i.e., information availability). In our setting, temptation occurs when the manager has both the incentive and the opportunity to act in his/her self-interest (increase bonus) at the expense of achieving the company’s objectives (i.e., maximizing the IPO issue price). While certain bonus structures may provide incentive for a manager to make decisions that do not maximize the company’s goals, the manager must also have the opportunity to engage in such behavior. This opportunity is dependent, in part, on whether the company’s senior executives have access to the same information as the manager when he/she makes decisions. When all information used by the manager in the decision-making process is also available to the senior executives, the company is able to accurately monitor the manager’s actions and determine whether they are eschewing agency and acting in self-interest. However, when the manager has access to information that is not available to senior executives, the manager can use this private information for personal gain.

Therefore, consistent with prior experimental research (e.g., Cianci et al. 2014), incentive and opportunity are manipulated concurrently. As shown in “Appendix 2”, Panel A, participants in the temptation-absent condition are told they receive a guaranteed bonus of 25% of a $200,000 base salary in both Year 1 and Year 2 (the current and following fiscal years, respectively) and that the CFO is aware of the current projection of Year 1 expenses prior to the manager’s recommendation (i.e., the CFO has the same information that the manager has when the manager makes his/her decision).Footnote 4 When bonus targets are guaranteed as a fixed percentage of salary and senior executives are fully aware that current year expenses are below budget, the manager has little incentive or opportunity to make decisions misaligned with the goals set by senior executives. In such a case, as proposed in agency theory, managers (agent) would tend to record lower expense amounts in line with the firm’s (principal) objectives.

In the temptation-present condition, participants’ bonuses vary based on achieving targets for minimizing plant expenses (see “Appendix 2”, Panel B). In addition, they are told that the CFO is unaware of the current projection of Year 1 expenses prior to the expense decision. Bonuses vary as a percentage of base salary ($200,000). In the scenario, projected plant expenses for Year 1 ($77.1 million) are $3.0 million below the maximum 40% bonus target for expenses (i.e., the participant currently qualifies for the largest bonus in Year 1). This $3.0 million cushion gives the manager the opportunity to book expenses for an amount up to the full value of all contract services not yet billed without jeopardizing any portion of the maximum 40% bonus for Year 1, if he or she chooses to make such a recommendation.

Bonus targets for Year 2 are structured so that projected plant expenses of $83.05 million are $50,000 above the bonus target expense threshold of $83.00 million that would qualify the manager for the minimum 20% bonus (i.e., the participant currently does not qualify for any bonus in Year 2, based on projected expenses). Thus, if the manager decides to book an expense amount in Year 1, bonus targets become easier to achieve in Year 2. For example, an expense recommendation of $3.0 million in Year 1 will not only preserve the maximum 40% bonus in Year 1 but will also help qualify the manager for a 40% bonus in Year 2 if actual Year 2 results are consistent with the current projections. Therefore, the manager knows actual expenses for the current year are favorable relative to bonus targets (i.e., below bonus targets) but senior executives (principals) do not—i.e., temptation is present. In this condition, managers would be tempted to recommend additional current year expenses, thereby making it easier to minimize expenses recorded in the subsequent year and, thus, “game the system” to maximize his/her combined 2-year bonus payout.

The second independent variable, corporate social responsibility, is operationalized by manipulating whether or not the company expresses a commitment to being socially responsible (see “Appendix 3”). In the commitment to corporate social responsibility-present condition, participants are informed that the company is well known throughout its industry and the business world as being socially responsible. It purchases its raw materials only from environmentally friendly suppliers and conducts social responsibility audits of its facilities to ensure the protection of workers’ civil rights and to oversee the ecological well-being of the organization. In the commitment to corporate social responsibility-absent condition, no specific mention of any socially responsible values or activities (whether positive or negative valence) is made.

Covariates

We asked managers to indicate their personal sensitivity to social responsibility (i.e., “How concerned are you, personally, about issues of social responsibility:” where 1 = Not At All Concerned to 10 = Very Concerned). We included this covariate in our analysis as socially oriented employees tend to be attracted to and more attentive to firms that practice CSR (Aguinis and Glavas 2012). More importantly, this covariate can account in part for individual differences, such as social consciousness, that may influence their personal sensitivity to CSR and thereby influence the pattern of results. It is important to include individuals’ CSR proclivity as a control variable, as it is ‘individual actors… who actually strategize, make decisions and execute CSR initiatives’ (Aguinis and Glavas 2012, p. 953).

We also included gender as a control variable in our analysis because research suggests that women tend to exhibit higher moral development, behave more ethically, and act less aggressively than men in business and organizational contexts (e.g., Bolino and Turnley 2003; Ritter 2006). Previous research also suggests that greater work experience can enhance manager competences in business knowledge, insightfulness, and decision making (McEnrue 1988; Dragoni et al. 2009). Therefore, we also included both professional work experience and experience in budgeting as covariates to ensure the results are not simply reflecting or are tainted by business/budget expertise, given the experimental materials. Conducting our analysis with and without these variables, as well as supplemental tests using other possible demographic variables (e.g., participant university affiliation), does not change any of the inferences drawn.

Results

Manipulation Checks

Manipulation checks for both independent variables indicate that participants generally understood the manipulations. Specifically, manipulation checks for the temptation manipulation—which concurrently manipulated incentive and opportunity—reveal that, out of 112 participants, one hundred four correctly identified their bonus structure (i.e., 93% passed the incentive portion of the temptation manipulation check) while one hundred responded correctly to a question regarding whether or not the CFO had the same information as the manager (i.e., 89% passed the opportunity portion of the temptation manipulation check). A supplemental test removing these participants from the analysis does not change any of the inferences drawn, and thus all were included in primary analyses. A manipulation check for CSR suggests that this manipulation was also successful. On a ten-point scale, participants were asked to indicate how socially responsible the company in the case was (i.e., “Based on the information provided in this case, how socially responsible is the company (HCP) in this scenario:” where 1 = “not at all socially responsible” and 10 = “very socially responsible”). Untabulated ANCOVA results indicate that means for the present and absent CSR commitment conditions were significantly different and directionally consistent with the manipulation (7.14 and 5.35, respectively; F = 25.626, p = 0.0001, two-tailed). In addition, it is important to note that the main effect of temptation (F = 0.815, p = 0.369, two-tailed) and the interaction between temptation and commitment to CSR (F = 0.907, p = 0.343, two-tailed) on the dependent variable were not significant.

Hypotheses Testing

Our hypotheses are tested using an ANCOVA with temptation (present vs. absent) and commitment to CSR (present vs. absent) as the independent variables and managers’ perceptions of their personal concern for issues related to social responsibility, experience in budgeting, gender, and years of professional work experience as covariates. The dependent variable is a rank transformation of managers’ expense recommendations.Footnote 5 As reported in Table 1, the overall model is significant (F = 3.447, p = 0.002, two-tailed).

Temptation and (Un)Ethical Decision-Making

Taken together, Hypotheses 1a and 1b predicted that when temptation is present (absent), managers will make less (more) ethical decisions. Specifically, we expect larger (smaller) expense recommendations for the temptation-present (absent) conditions, respectively. As shown in Table 1, the main effect of temptation is significant (F = 15.793, p < 0.001, two-tailed). Consistent with H1 predictions, managers in the temptation-present condition recommended significantly higher expenses than those in the temptation-absent condition ($1,559,983 vs. $695,085, respectively; Table 1). These results suggest that in our setting, managers tend to override corporate concerns in favor of their own interests (i.e., book larger expense amounts to maximize bonus potential) when there is temptation to do so, and tend to make decisions that help achieve corporate goals (i.e., book smaller expense numbers to improve the IPO stock price) when temptation is absent.

The Moderating Effect of CSR Commitment on Temptation

Taken together, Hypotheses 2a and 2b proposed that firms’ commitment to CSR should buffer managers’ unethical behavior in the face of temptation. Specifically, in the presence of temptation, when a firm’s commitment to CSR is present (absent) managers will be more (less) likely to make ethical decisions; while we expected no significant effect of CSR commitment in the absence of temptation. As expected, ANCOVA results indicate a significant interactive effect on managers’ ethical decisions (F = 3.894, p = 0.05, two-tailed; Table 1). Figure 2 graphically depicts the means for the dependent variable by condition and demonstrates that a commitment to CSR has the anticipated moderating effect on managers’ expense recommendations. Specifically, there is a greater difference in managers’ mean expense recommendations between CSR commitment conditions when temptation is present ($367,610) than when it is absent ($227,240), providing directional support for H2. Further, least significant difference pairwise comparisons show that as hypothesized, a commitment to CSR significantly buffers the effect of temptation, resulting in lower expense recommendations when temptation is present ($1,407,390 [Cell 2] vs. $1,775,000 [Cell 1], p < 0.03, one-tailed; Table 1) and no statistically significant moderating effect of CSR commitment when temptation is absent ($818,333 [Cell 4] vs. $591,094 [Cell 3], p = 0.189, one-tailed; Table 1). These results reinforce our hypothesis that a commitment to CSR significantly influences managers’ ethical choices only under conditions of temptation.

Supplemental Analysis

The logic supporting H2 is based largely on the notion that a firm’s commitment to CSR makes salient a favorable and esteemed organizational context, which provides self-enhancement and collective-focused social identity to managers, leading to actions aligned with the interest of the firm. The current experimental design did not allow for measuring participants’ views or interpretations of the organizational context after reading the scenarios, prior to measuring the dependent variable, as it would have influenced participants’ responses and contaminated the findings. After measuring the dependent variable, however, we explored the extent that the organizational context factored into participants’ decision-making. Specifically, we asked participants the following two item stems, “Given the environment at HCP, I feel that the corporate culture…” and “Given the environment at HCP, I feel that the values of the company…”, and asked them to record their responses on a ten-point scale, where 1 = “Did Not Factor Into My Decision-Making Process” and 10 = “Factored Heavily Into My Decision-Making Process.” Participants in the CSR commitment-present condition reported that both corporate culture and corporate values factored more heavily into their decision-making processes than those in the CSR commitment-absent condition (non-tabulated mean responses 4.57 versus 3.57, respectively) (p = 0.041, two-tailed). For corporate values, means are 5.19 and 4.19 (non-tabulated) for the CSR commitment-present and CSR commitment-absent groups, respectively (p = 0.038, two-tailed).

Discussion

The current study sought to advance the CSR and behavioral ethics literatures by investigating the moderating effect of a firm’s CSR commitment on the relationship between temptation and managers’ ethical decisions. We did so in a 2 × 2 experimental design in which we manipulated two independent variables between participants: a company’s commitment to CSR (present, absent) and temptation (present, absent), operationalized by the presence of both incentive and opportunity to behave unethically. In our setting, experienced managers familiar with expense recording assumed the role of a plant manager in a hypothetical company and made a year-end expense decision. This expense decision is ethically charged in that it involves a choice between a self-focused decision (i.e., maximizing the likelihood of receiving bonuses over a 2-year period) and a company-focused decision (i.e., making a decision that is in the financial interest of the firm).

Consistent with agency theory, results indicate that when temptation is present, managers tend to override corporate aims and concerns and make less ethical decisions. In contrast, when temptation is absent, managers tend to make more ethical decisions (i.e., decisions aligned with the firm/agent’s interests. Also consistent with expectations, we find that a company’s commitment to CSR moderates the effect of temptation on managers’ decisions. Specifically, when a commitment to CSR is present, managers are more likely to make ethical decisions in the presence of temptation. However, when temptation is absent, managers are equally likely to make ethical decisions, regardless of their firm’s CSR commitments. These findings have both theoretical and practical implications.

Theoretical Implications

Costs of unethical manager behavior to firms are substantial and span not just direct financial, but also reputational costs (Kish-Gephart et al. 2014), highlighting a clear need to investigate ways to get managers to act as agents for the firm and mitigate such self-interested behavior. To address this problem, behavioral ethics research has tended to focus on identifying the factors creating “bad/good apples” to the neglect of the “bad/good barrels” they operate within (see Jennings et al. 2015; Tenbrunsel and Smith-Crowe 2008; Treviño et al. 2014 for reviews). The current model responds to calls to go beyond investigating self-interest as the focused driver of individuals’ ethical decision-making (Kish-Gephart et al. 2014). The current research shows that self-interest is conditional, and that being in a “good barrel” (higher CSR firm) establishes a boundary condition such that the deleterious effects of temptation on ethical behavior are tempered. We thus respond to calls to better understand how contextual factors promote employee ethical behavior in the workplace (e.g., Kish-Gephart et al. 2010; Treviño and Youngblood 1990).

Specifically, while there has been a growing focus on the effects of meso-level constructs in organizations on individual ethicality, such as leadership, and group processes and climate, there is a dearth of theory and research on macro-level factors, such as firm behavior as we investigate here. The current research supports that CSR activity may be one firm-level factor influencing desirable agency behavior. This new knowledge coupled with existing knowledge of how micro- and meso-level factors influence individual ethical decision-making can serve to promote a more multi-level approach to behavioral ethics theory-building and research, while simultaneously better integrating the separate canons of CSR and behavioral ethics research.

This study also contributes specifically to the body of CSR research. Prior CSR research has focused largely on its effects on outcomes at the organizational level (e.g., Barnett and Salomon 2012; Gregory et al. 2014; Harjoto and Jo 2015), causing scholars to call for more research to identify how individuals think and behave based on their firm’s CSR (Aguinis and Glavas 2012). More specifically, scholars have highlighted the need for experiments concerning the individual effects of CSR to establish causal relationships (Morgeson et al. 2013; Rupp et al. 2013). Our study makes one attempt to address this need.

We assess through a causally interpretable design whether a firm’s CSR affects individual, and in particular, managers’ ethical decisions. This is particularly important because, as Gond et al. (2017) note, studies of reactions to CSR have focused primarily on employees, and little is known as to how CSR influences the decisions and actions of managers and executives. To our knowledge, our study is the first to use a scenario-based experiment to identify how CSR influences managers’ “in-role performance”—i.e., managers’ responding to an experimental formal role task similar to what they might encounter in their professional environments (Gond et al. 2017, p. 234)—and is unique in that it examines the influence of CSR on a negative workplace behavior (i.e., temptation-influenced expense reporting), a neglected area of the micro-CSR literature. In addition, we provide evidence of an interactive effect of a firm’s CSR commitment and temptation on managers’ ethical decisions. Specifically, we identify a boundary condition such that the tendency of managers to act in their self-interest is mitigated by their firm’s commitment to CSR.

The current study also contributes to the literature from a theoretical standpoint by employing agency theory and social identity theory (SIT) together to describe why managers would be more inclined to act as agents and conduct themselves in ways most advantageous to the firm. In this way, we respond to calls for a better understanding of how theoretical mechanisms interact to produce CSR-related outcomes (Gond et al. 2017). In this paper, we developed new theory proposing that the moderating effect of CSR on the temptation–ethical behavior relationship occurs through social identity processes. Specifically, we proposed that CSR signals a positive firm reputation and status that provides managers self-enhancement through their affiliation (Cialdini et al. 1976; Tesser and Campbell 1982), promoting self-categorization whereby managers activate a collective identity and orientation (Brewer and Gardner 1996; Hogg and Terry 2000). One key proposition of social identity theory is that such alignment promotes individuals to act in accordance with collective interests versus self-interest (Cialdini and Richardson 1980; Snyder et al. 1986). While the current results evidence the proposed moderating effect and are consistent with this logic, we were unable to directly test the proposed social identity processes without contaminating the internal validity of the study. Our theoretical model, however, should promote future research to directly test these processes. Specifically important would be longitudinal field research that assesses the effects of firm’s CSR activities on key aspects of managers’ social identity (i.e., self-enhancement, self-categorization, and activation of collective self) over time, assessing their subsequent ethical decisions and behaviors when faced with temptation.

Our supplemental analyses not only reinforce the CSR manipulation’s efficacy, but further indirectly support that social identity processes were important in the managers’ decisions. When the firm expressed a corporate commitment to CSR, managers reported that both corporate culture and corporate values were made more salient, factoring more heavily into their decision-making processes as compared to managers in firms lacking commitment to CSR. This result highlights that when the firm is committed to CSR, managers’ positive attributions concerning the firm context become salient, thereby buffering managers’ against the dysfunctional outcomes that often arise in the face of temptation. Future research should build from this by considering whether and how firms may maximize this effect through the ways they communicate and “internally-market” their CSR activities to their managers and employees.

Further, while supplemental tests showed that the salience of the firm’s positive context was significantly higher in the CSR-present condition (i.e., the between-group effect), variance observed across participants within-group infers that individual differences also influenced perceptions of the context. This again suggests the usefulness of extending the current research into a multi-level model. Future research should, for example, assess whether aspects of managers’ moral self (e.g., moral attentiveness, moral identity, moral ownership, ethical ideology, or self-conscious moral emotions) (for overview of the components of the moral self, see Jennings et al. 2015) influence their awareness of, interpretation of, or reactions to, firm CSR activity. It is quite possible, for example, that individuals with higher moral attentiveness, and/or who feel greater moral ownership for the ethicality of their work context would more readily perceive and apply cognitive resources toward processing and making meaning of their firm’s CSR activities.

Further, the current research informs agency theory. Agency theory-based predictions of employee ethical behavior have largely focused on transactional logic, grounded in self-interest, whereby the alignment of the agent’s goals and incentives with that of the principal are typically the focus (e.g., Cianci et al. 2014; Harrison and Harrell 1993). Our research suggests a perhaps less pessimistic view, that through the organization “doing good” social identity processes motivate managers to withstand temptation and also seek to “do good.” One might argue that such motivation is still transactional/extrinsic as it is based on seeking psychological self-enhancement. Future research on agency theory might fruitfully expand to include both financial/material and psychological forms of self-enhancement.

Finally, as CSR is often publicly observable, and rankings of firms’ CSR commitment are available (e.g., Forbes 2016), it may be useful if not important for researchers using secondary data sources to control for differences in CSR activity when investigating (un)ethical behavior in firms given our finding regarding its buffering effect on managers’ unethical behavior. Not accounting for the firm-level effect of CSR may otherwise lead to biased estimates.

Practical Implications

From a practical perspective, our results regarding manager behavior suggest that senior management should consider the unintended consequences of typical compensation contracts. As shown in Fig. 2 (when CSR commitment is absent), managers booked over 200% higher expenses when temptation was present versus absent. As a result, organizations might rethink how they structure performance-based bonuses to minimize the likelihood that employees will eschew agency and engage in such self-interested behavior.

In addition, results show that the context in which managers’ work plays a significant role in their ethical decision making. Specifically, as evident in Fig. 2, a firm’s commitment to behaving in a socially responsible manner reduces managers’ unethical behavior in our setting. Thus, corporate officers and boards may want to consider the important influence of their firm’s commitment to CSR on ethical behavior throughout the organization. Given the social identity factors involved, senior leaders should also consider the way they make those CSR activities and subsequent positive social effects salient to their internal managers, such that they be more aware of and more fully “bask in the glory” of their organization’s good deeds. Indeed, image management is extremely relevant to the ethical decision making of company managers, and thus companies engaged in CSR may benefit by effectively communicating their good corporate citizenship to their employees (Cable, Aiman-Smith, Mulvey, and Edwards 2000). Accumulating evidence underscores the powerful influence of organizational environments in promoting or discouraging the unethical intentions and behavior of individuals (e.g., ethical culture in Schaubroeck et al. 2012). The current results demonstrate that managers should consider the company’s CSR commitment as another key contextual factor.

Additionally, the current results suggest that CSR mitigates the risk of unethical behavior within a firm. The financial/investing community might thus want to consider CSR when evaluating the reliability and quality of a firm’s internal controls and governance, and its risk profile. Furthermore, gaining a better understanding of the key organizational factors—such as temptation and CSR commitment—that influence managers’ tendencies to behave unethically may help regulators better direct their policy and investigative efforts.

Limitations and Future Research

A limitation of our study is that we consider only one type of unethical decision (i.e., making an expense decision that benefits one’s self-interest and is contrary to the company’s best interest). Future studies should examine a breadth of other unethical decisions in order to improve the generalizability of our findings. We also only look at a single type of incentive (i.e., a short-term bonus incentive). Further research could examine other types of financial and non-financial incentives that can create various forms and levels of temptation. Additionally, while we found that CSR bolstered managers’ ethicality in the face of temptation (prevented them from doing bad), it is unclear whether corporate CSR provides similar impetus for managers to seek doing good. Future research should thus assess whether CSR promotes ethicality when supererogatory action is called for, such as whistle blowing or acts requiring moral courage.

We also investigated CSR as a single construct—i.e., we manipulated several components of CSR simultaneously—which prevents us from assessing the relative effects of different forms of CSR. Future research should address whether forms of CSR commitments or activities (e.g., CSR aimed at employees vs. the environment), or combination thereof, have differing effects on employees’ judgments and decisions. It may be that some forms of CSR activities provide higher levels of self-enhancement than others.

The current study provides evidence that corporate CSR commitment influences individual managers’ ethical judgments. Going forward, future research should consider other organization-level variables in conjunction, such as ethical leadership and ethical culture (e.g., Schaubroeck et al. 2012), and their unique and possibly interactive effects on individual ethical judgment. As noted above, multi-level models inclusive of multiple micro-, meso-, and macro-factors are particularly needed to advance behavioral ethics research. Manipulating as many variables in an experimental design may be difficult without introducing confounds and losing internal validity, and may not capture the ecological dynamics within actual organizations. Thus, a serial set of focused laboratory studies may be needed to establish initial causal relations between predictors and outcomes (e.g., manipulating ethical culture and CSR in one study; and manipulating CSR, group processes and individual differences in another study). These laboratory studies could be followed by testing a more complex model in a field study to isolate the relative effects of the different predictors, and their potential interactions, on ethical outcomes.

As noted above, like all scenario-based laboratory studies (e.g., Leavitt et al. 2012; Jones et al. 2014; Rupp et al. 2013), establishing the external/ecological validity and generalizability of our findings is subject to future testing. Such laboratory studies ask managers to immerse themselves in a notional scenario lacking many of the complex dynamics inherent in an actual organization. This is of course the purpose of laboratory studies, as through random assignment and manipulation of a set of variables, they provide internal validity through isolating the causal relationships between variables. While that is a critical first step in theory-testing, much additional field research within and across actual organizational contexts is needed to establish external validity for our findings.

The sample consisted of practicing managers with an ample average of almost 12 years of experience. Yet, as they were all enrolled in special MBA programs, they may represent a unique sample of highly motivated and/or developmentally oriented or achievement-oriented managers. Generalization of this model to a more diverse set of managers may yield different results. Additionally, while our findings demonstrate that corporate CSR commitment influences individual manager behavior, its effects on employees at varying levels within the organization remains unknown. It is possible that a manager’s level within an organization’s hierarchy may influence whether and how company CSR commitment is perceived and, in turn, impacts individual ethical behavior. More senior managers, for example, may feel they are a “greater part” of their firm’s activities, and thereby be more likely to receive self-enhancement in response than managers at lower levels.

Further, managers’ views on their companies’ CSR commitment may vary depending on their own economic situations. For instance, if a manager feels that s/he is underpaid, perhaps the company’s CSR engagement would be a source of resentment for the manager. Further, such a disenfranchised manager may be less likely to self-categorize with the organization and act as an agent on its behalf. This line of research could thus be an interesting avenue for future research.

In closing, temptations for self-interested behaviors are often present in organizational settings, deterring managers from acting as agents for the principals they serve. The current results suggest that firms’ CSR commitments have internal effects, promoting managers to make decisions in the interest of the firm, and thereby achieve greater principal-agent alignment. These findings open numerous described areas for future research at the intersection of CSR, behavioral ethics, and agency theories.

Notes

During the instrument development phase, we interviewed financial managers of Fortune 500 companies who noted that they regularly rely on operating managers to make expense estimates.

The managing director of an executive search firm recommended the bonus percentages used in the no temptation and temptation conditions based on their understanding of firm averages.

Prior to hypothesis testing we assessed the distribution of the dependent variable. The Shapiro–Wilk test for normality indicates that the reported expense amounts for each of the four conditions are not normally distributed (all p < 0.008). In addition, as shown in Table 1, the standard deviations of the reported expense amounts are quite high. Thus, consistent with prior research (e.g., Boylan and Sprinkle 2001; Hutton et al. 2013), we conducted our analyses using the ranks of managers’ expense recommendations as the dependent variable instead of the reported expense amounts. This is because since the reported expense amounts are not normally distributed, it would violate a key ANOVA assumption. Accordingly, an ANCOVA using a rank transformation of the reported expense amounts is likely to be more efficient, powerful, and more theoretically appropriate than an ANCOVA conducted using the non-ranked reported expense amounts (Conover and Iman 1982). Analyses conducted using the non-ranked reported expense amounts yield results that are qualitatively similar to those reported in the paper.

References

Aguilera, R. V., Rupp, D. E., Williams, C. A., & Ganapathi, J. (2007). Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 32, 836–863.

Aguinis, H., & Glavas, A. (2012). What we know and don’t know about corporate social responsibility: A review and research agenda. Journal of Management, 38, 932–968.

Albert, S., Ashforth, B. E., & Dutton, J. E. (2000). Organizational identity and identification: Charting new waters and building new bridges. Academy of Management Review, 25, 13–17.

Alicke, M. D., & Govorun, O. (2005). The better-than-average effect. In M. D. Alicke, D. A. Dunning, & J. I. Krueger (Eds.), The self in social judgment (pp. 85–106). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Alvesson, M. (2002). Understanding organizational culture. London: Sage Publications.

Arbogast, S. V. (2008). Resisting corporate corruption: Lessons in practical ethics from the Enron wreckage. Salem, MA: M & M Scrivener Press.

Ariely, D. (2012). The (honest) truth about dishonesty. New York: HarperCollins.

Arnaud, A., & Schminke, M. (2012). The ethical climate and context of organizations: A comprehensive model. Organizational Science, 23(6), 1767–1780.

Ashford, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 20–39.

Association for Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE). (2016). Staggering cost of fraud. http://www.acfe.com/rttn2016/docs/Staggering-Cost-of-Fraud-infographic.pdf

Barnett, M. L., & Salomon, R. M. (2012). Does it pay to be really good? Addressing the shape of the relationship between social and financial performance. Strategic Management Journal, 33, 1304–1320.

Bolino, M. C., & Turnley, W. H. (2003). Counternormative impression management, likeability, and performance ratings: The use of intimidation in an organizational setting. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24, 237–250.

Boylan, S., & Sprinkle, G. (2001). Experimental evidence on the relation between tax rates and compliance: The effect of earned vs. endowed income. Journal of the American Taxation Association, 23, 75–90.

Breckler, S. J., & Greenwald, A. G. (1986). Motivational facets of the self. In E. T. Higgins & R. Sorrentino (Eds.), Handbook of motivation and cognition (pp. 145–164). New York: Guilford Press.

Brewer, M. B., & Gardner, W. (1996). Who is this “we”? Levels of collective identity and self representations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 83–93.

Brown, M. E., Treviño, L. K., & Harrison, D. (2005). Ethical leadership: A social learning perspective for construct development and testing. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97, 117–134.

Cable, D. M., Aiman-Smith, L., Mulvey, P. W., & Edwards, J. R. (2000). The sources and accuracy of job applicants’ beliefs about organizational culture. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 1076–1085.

Carnahan, S., Kryscynski, D., & Olson, D. (2016). How corporate social responsibility reduces employee turnover: Evidence from attorneys before and after 9/11. Academy of Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2015.0032.

Cerulo, K. A. (1997). Reframing social concepts for a brave new (virtual) world. Sociological Inquiry, 67, 48–58.

Cialdini, R. B., Borden, R. J., Thorne, A., Walker, M. R., Freeman, S., & Sloan, L. R. (1976). Basking in reflected glory: Three (football) field studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 34, 366–375.

Cialdini, R. B., & Richardson, K. D. (1980). Two indirect tactics of image management: Basking and blasting. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 406–415.

Cianci, A. M., Hannah, S. T., Roberts, R. P., & Tsakumis, G. T. (2014). The effects of authentic leadership on followers’ ethical decision-making in the face of temptation: An experimental study. The Leadership Quarterly, 25, 581–594.

Clarkson, M. B. E. (1995). A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review, 20, 92–117.

Conover, W. L., & Iman, R. L. (1982). Analysis of covariance using the rank transformation. Biometrics, 38, 715–724.

Corporate Responsibility. (2016). CR’s 100 best corporate citizens. Available at: http://www.thecro.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/100best_1.pdf

Dhanesh, G. S. (2014). CSR as organization–employee relationship management strategy: A case study of socially responsible information technology companies in India. Management Communication Quarterly, 28, 130–149.

Dragoni, L., Tesluk, P. E., Russell, J. E. A., & Oh, I. (2009). Understanding managerial development: Integrating developmental assignments, learning orientation, and access to developmental opportunities in predicting managerial competencies. Academy of Management Journal, 52, 731–743.

Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39, 239–263.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Agency theory: An assessment and review. Academy of Management Review, 14, 57–74.

El Akremi, A., Gond, J. P., Swaen, V., De Roeck, K., & Igalens, J. (2015). How do employees perceive corporate responsibility? Development and validation of a multidimensional corporate stakeholder responsibility scale. Journal of Management. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315569311.

Erdogan, B., Bauer, T. N., & Taylor, S. (2015). Management commitment to the ecological environment and employees: Implications for employee attitudes and citizenship behaviors. Human Relations: Studies Towards the Integration of the Social Sciences, 68, 1669–1691.

Farooq, O., Payaud, M., Merunka, D., & Valette-Florence, P. (2014). The impact of corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment: Exploring multiple mediation mechanisms. Journal of Business Ethics, 125, 563–580.

Fischbach, A., & Shah, J. Y. (2006). Self-control in action: Implicit dispositions toward goals and away from temptations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(5), 820–832.

Forbes. (2016). The companies with the best CSR reputations in the World in 2016. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/karstenstrauss/2016/09/15/the-companies-with-the-best-csr-reputations-in-the-world-in-2016/#ea73c6a75060

Freitas, A. L., Liberman, N., & Higgins, E. (2002). Regulatory fit and resisting temptation during goal pursuit. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 291–298.

Gino, F., Schweitzer, M. E., Mead, N. L., & Ariely, D. (2011). Unable to resist temptation: How self-control depletion promotes unethical behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 115, 191–203.

Gond, J., El Akremi, A. E., Swaen, V., & Babu, N. (2017). The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: A person-centric systematic review. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38, 225–246.

Greenwald, A. G., & Breckler, S. J. (1985). To whom is the self presented? In B. Schlenker (Ed.), The self and social self (pp. 126–145). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Gregory, A., Tharyan, R., & Whittaker, J. (2014). Corporate social responsibility and firm value: Disaggregating the effects on cash flow, risk, and growth. Journal of Business Ethics, 124, 633–657.

Harding, T. (2005). Debunking the social myth. Business Strategy Review, 16, 58–88.

Harjoto, M., & Jo, H. (2015). Legal vs. normative CSR: Differential impact on analyst dispersion, stock return volatility, cost of capital, and firm value. Journal of Business Ethics, 128, 1–20.

Harrison, P. D., & Harrell, A. (1993). Impact of “adverse selection” on managers’ project evaluation decisions. Academy of Management Journal, 36, 635–643.

Haslam, S. A., Ryan, M. K., Postmes, T., Spears, R., Jetten, J., & Webley, P. (2006). Sticking to our guns: Social identity as a basis for the maintenance of commitment to faltering organizational projects. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27, 607–628.

Heal, G. (2005). Corporate social responsibility: An economic framework and financial framework. The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance: Issues and Practice, 30(3), 387–409.

Hess, D., Rogovsky, N., & Dunfree, T. W. (2002). The new wave of corporate community involvement: Corporate social initiatives. California Management Review, 44(2), 110–125.

Hogg, M. A., & Terry, D. I. (2000). Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts. Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 121–140.

Hogg, M. A., Terry, D. J., & White, K. M. (1995). A tale of two theories: A critical comparison of identity theory with social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 58, 255–269.

Hutton, P., Kelly, J., Lowens, I., Taylor, P. J., & Tai, S. (2013). Self-attacking and self-reassurance in persecutory delusions: A comparison of healthy, depressed and paranoid individuals. Psychiatry Research, 205(1/2), 127–136.

Jennings, P. L., Mitchell, M. S., & Hannah, S. T. (2015). The moral self: A review and integration of the literature. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36, S104–S168.

Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3, 305–360.

Johnson, R. E., Selenta, C., & Lord, R. G. (2006). When organizational justice and the self-concept meet: Consequences for the organization and its members. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 99(2), 175–201.

Jones, E. E. (1990). Interpersonal perception. New York: W. H. Freeman and Company.

Jones, D. A., Willness, C. R., & Madey, S. (2014). Why are job seekers attracted by corporate social performance? Experimental and field tests of three signal-based mechanisms. Academy of Management Journal, 57(2), 383–404.

Kish-Gephart, J., Detert, J., Treviño, L. K., Baker, V., & Martin, S. (2014). Situational moral disengagement: Can the effects of self-interest be mitigated? Journal of Business Ethics, 125, 267–285.

Kish-Gephart, J. J., Harrison, D. A., & Treviño, L. K. (2010). Bad apples, bad cases, and bad barrels: Meta-analytic evidence about sources of unethical decisions at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 1–31.

Kreiner, G. E., Hollensbe, E. C., & Sheep, M. L. (2006). Where is the “me” among the “we”? Identity work and the search for optimal balance. Academy of Management Journal, 49, 1031–1057.

Leavitt, K., Reynolds, S. J., Barnes, C. M., Schilpzand, P., & Hannah, S. T. (2012). Different hats, different obligations: Plural occupational identities and situated moral judgments. Academy of Management Journal, 55(6), 1316–1333.

Lewis, M. (2009). The man who crashed the world. Vanity Fair, 588(August), 98–103.

Maignan, I., & Ferrell, O. C. (2001). Corporate citizenship as a marketing instrument. European Journal of Marketing, 35, 457–484.

Maignan, I., Ferrell, O. C., & Hult, G. T. (1999). Corporate citizenship: Cultural antecedents and business benefits. Journal of the Academy Marketing Science, 27, 455–469.

McEnrue, M. P. (1988). Length of experience and the performance of managers in the establishment phase of their careers. Academy of Managerial Journal, 31(1), 175–185.

McLean, B., & Nocera, J. (2010). All the devils are here: The hidden history of the financial crisis. New York: Penguin Group.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. (2001). Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Academy of Management Review, 26, 117–127.

Moore, D. A., & Lowenstein, G. (2004). Self-interest, automaticity, and the psychology of conflict of interest. Social Justice Research, 17(2), 189–202.

Morgeson, F. P., Aguinis, H., Waldman, D. A., & Siegel, D. S. (2013). Extending corporate social responsibility research to the human resource management and organizational behavior domains: A look to the future. Personnel Psychology, 66, 805–824.

Morsing, M., & Roepstorff, A. (2015). CSR as corporate political activity: Observations on IKEA’s CSR identity-image dynamics. Journal of Business Ethics, 128, 395–409.

Orlitzky, M., Schmidt, F. L., & Rynes, S. L. (2003). Corporate social and financial performance: A metaanalysis. Organization Studies, 24(3), 403–441.

Ritter, B. (2006). Can business ethics be trained? A study of the ethical decision-making process in business students. Journal of Business Ethics, 68(2), 153–164.

Ross, L. (1977). The intuitive psychologist and his shortcomings: Distortions in the attribution process. In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 10, pp. 174–221). New York: Academic Press.

Rupp, D. E., Ganapathi, J., Aguilera, R. V., & Williams, C. A. (2006). Employee reactions to corporate social responsibility: An organizational justice framework. Journal of Organizational Studies, 27, 537–543.

Rupp, D. E., & Mallory, D. B. (2015). Corporate social responsibility: Psychological, person-centric, and progressing. The Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 2, 211–236.

Rupp, D. E., Shao, R., Thornton, M. A., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2013). Applicants’ and employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: The moderating effects of first-party justice perceptions and moral identity. Personnel Psychology, 66, 895–933.

Schaubroeck, J. M., Hannah, S. T., Avolio, B. J., Kozlowski, S. W. J., Lord, R. G., Treviño, L. K., et al. (2012). Embedding ethical leadership within and across organization levels. Academy of Management Journal, 55, 1053–1078.

Schein, E. H. (2004). Organizational culture and leadership. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Schlenker, B. R., & Weigold, M. F. (1992). Interpersonal processes involving impression regulation and management. Annual Review of Psychology, 43, 133–168.

Schminke, M., & Wells, D. (1999). Group processes and performance and their effects on individuals’ ethical framework. Journal of Business Ethics, 18, 367–381.

Sedikides, C., Green, J. D., & Pinter, B. T. (2004). Self-protective memory. In D. Beike, J. Lampinen, & D. Behrend (Eds.), The self and memory (pp. 161–179). Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press.

Snyder, C. R., Lassegard, M., & Ford, C. E. (1986). Distancing after group success and failure: Basking in reflected glory and cutting off reflected failure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 382–388.

Spanjol, J., Tam, L., & Tam, V. (2015). Employer–employee congruence in environmental values: An exploration of effects on job satisfaction and creativity. Journal of Business Ethics, 130, 117–130.

Special report: Corporate social responsibility. (2005). Business Strategy Review, 16, 58.

Tenbrunsel, A. E. (1998). Misrepresentation and expectations of misrepresentation in an ethical dilemma: The role of incentives and temptation. Academy of Management Journal, 41, 330–339.

Tenbrunsel, A. E., & Smith-Crowe, K. (2008). Ethical decision making: where we’ve been and where we’re going. Academy of Management Annals, 2(1), 545–607.

Tesser, A., & Campbell, J. (1982). Self-evaluation maintenance and the perception of friends and strangers. Journal of Personality, 50, 261–279.

Treviño, L. E. (1986). Ethical decision making in organizations: A person–situation interactionist model. Academy of Management Review, 11, 601–617.

Treviño, L. K., den Nieuwenboer, N. A., & Kish-Gephart, J. J. (2014). (Un)ethical behavior in organizations. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 635–660.

Treviño, L. K., & Youngblood, S. A. (1990). Bad apples in bad barrels: A causal analysis of ethical decision-making behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 378–385.

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S., & Wetherell, M. (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Viswesvaran, C., Deshpande, S. P., & Milman, C. (1998). The effect of corporate social responsibility on employee counterproductive behaviour. Cross Cultural Management, 5(4), 5–12.

Wang, Y., & Berens, G. (2015). The impact of four types of corporate social performance on reputation and financial performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 131, 337–359.

Wiesenfeld, B. M., Raghuram, S., & Garud, R. (1999). Communication patterns as determinants of organizational identification in a virtual organization. Organization Science, 19, 777–790.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

We gratefully acknowledge the research support provided by the Institute of Managment Accountants and the School of Business at Wake Forest University.

Cathy A. Beaudoin is retired.

Appendices