Abstract

Monetary intelligence theory asserts that individuals apply their money attitude to frame critical concerns in the context and strategically select certain options to achieve financial goals and ultimate happiness. This study explores the dark side of monetary Intelligence and behavioral economics—dishonesty (corruption). Dishonesty, a risky prospect, involves cost–benefit analysis of self-interest. We frame good or bad barrels in the environmental context as a proxy of high or low probability of getting caught for dishonesty, respectively. We theorize: The magnitude and intensity of the relationship between love of money and dishonest prospect (dishonesty) may reveal how individuals frame dishonesty in the context of two levels of subjective norm—perceived corporate ethical values at the micro-level (CEV, Level 1) and Corruption Perceptions Index at the macro-level (CPI, Level 2), collected from multiple sources. Based on 6382 managers in 31 geopolitical entities across six continents, our cross-level three-way interaction effect illustrates: As expected, managers in good barrels (high CEV/high CPI), mixed barrels (low CEV/high CPI or high CEV/low CPI), and bad barrels (low CEV/low CPI) display low, medium, and high magnitude of dishonesty, respectively. With high CEV, the intensity is the same across cultures. With low CEV, the intensity of dishonesty is the highest in high CPI entities (risk seeking of high probability)—the Enron Effect, but the lowest in low CPI entities (risk aversion of low probability). CPI has a strong impact on the magnitude of dishonesty, whereas CEV has a strong impact on the intensity of dishonesty. We demonstrate dishonesty in light of monetary values and two frames of social norm, revealing critical implications to the field of behavioral economics and business ethics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Prospect theory provides a value function that is concave for gains, convex for losses, and steeper for losses than for gains. According to Kahneman (2011), a 2002 Nobel Laureate in economic sciences, the fourfold pattern of risk attitudes is one of the core achievements of prospect theory: risk aversion for gains and risk seeking for losses of high probability; risk seeking for gains and risk aversion for losses of low probability. Interestingly, little or no research has incorporated “cultural differences in attitude toward money” (Kahneman 2011, p. 298) in testing prospect theory nor extended Kahneman’s prospect theory (Kahneman and Tversky 1979) from a choice of options at the individual level to managers’ ultimate choice of dishonesty across cultures.

Kish-Gephart et al. (2010) examined behavioral ethics from three perspectives: bad apples (individual), bad cases (moral issue), and bad barrels (environment). Corruption is both a state and a process. It reflects not only the corrupt behavior of an individual—defined as the illicit use of one’s position or power for perceived personal or collective gain—but also the dangerous, viruslike infection of a group, organization, industry, nation/country, or geopolitical entityFootnote 1 (Ashforth et al. 2008; Tepper et al. 2009). In this study, we investigate not only managers’ money attitude—love of money—an individual difference variable (bad apples) that excites dishonesty but also the corrupt culture—corporate ethical values (CEV) and Transparency International’s (TI) Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) (bad barrels). Dishonesty is not only a multilevel real-world phenomenon, but also a culturally defined psychological construct. Most researchers use a single level of analysis (applying a micro or macro lens alone) which yields incomplete understanding at either level (Hitt et al. 2007).

Theory of planned behavior (TPB) posits that attitude toward the behavior, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control lead to behavioral intention which, in turn, predicts behavior (Ajzen 1991). Researchers have applied TPB across numerous disciplines (Armitage and Conner 2001; Cordano and Frieze 2000; Manning 2009). Very few, however, have applied TPB in investigating behavioral ethics (dishonesty) and conducted research in countries outside the US and in entities at the bottom of the global economic pyramid (Prahalad and Hammond 2002). The contribution of TPB is not as ubiquitous as most researchers once thought, particularly in under-researched areas of the world (Kirkman and Law 2005).

People around the world have unique histories, cultures, beliefs, and values as well as economic, legal, political, and social infrastructures, yet they all speak one common language that everyone understands: money. We focus on dishonest propensity (hereafter dishonesty) which is, directly or indirectly, related to self-centered personal and collective financial gains and money. Money is an instrument of commerce and a measure of value (Smith 1776/1937). Although money is universally recognized across culture, the meaning of money (Colquitt et al. 2011; Tang 1992, 1993) is in the eye of beholder (McClelland 1967).

Following the attitude-to-behavioral-intention aspect of the TPB, we incorporate money attitude (love of money, LOM) in understanding dishonesty. In fact, limited research has empirically tested the proposition—the love of money is the root of all evils.Footnote 2 Following Kish-Gephart et al.’s (2010) perspective, we consider love of money as an individual difference variable (bad apples) and dishonesty as a small component of evil (unethical intention). Since the relationship between love of money and dishonesty may vary across cultures, we must investigate this issue in a large cross-cultural study, using a multilevel theoretical model.

Recent researchers stress the importance of including contextual variables in studying behavioral ethics (Bamberger 2008; Cohn et al. 2014; Martin et al. 2007; Pascual-Ezama et al. 2015; Rousseau and Fried 2001; Treviño 1986) because most people look to the social context to determine what is ethically right and wrong, obey authority figures, and do what is rewarded in organizations (Bandura 1986; Bandura et al. 1996). Recalling the Ten Commandments or signing an honor code, for example, eliminates cheating completely, while offering poker chips doubles the level of cheating (Ariely 2008a; Mazar et al. 2008). The legal enforcement and corrupt cultures at the local and entity levels have significant impacts on corruption—parking violations among United Nations diplomats living in New York City (Fisman and Miguel 2007). In our investigation of a multilevel theoretical model of dishonesty, we include two different levels of ethical values or cultures (bad barrels) (Kish-Gephart et al. 2010): perception of corporate ethical values (CEV) (Hunt et al. 1989)—a proxy for good/bad barrels at the organization (micro) level and Corruption Perceptions IndexFootnote 3 (CPI)—a proxy for good/bad barrels at the entity (macro) level (Martin and Cullen 2006; Victor and Cullen 1988). We make the following unique contributions.

We bridge the gap between prospect theory and behavioral ethics and explore the relationship between individuals’ love of money (bad apples) and dishonesty. We assert: people frame two levels of social norm (bad barrels): corporate ethical values (CEV, Level 1) and corruption perceptions index (CPI, Level 2), differently, and strategically select options to engage in dishonesty. Based on data collected from 6382 managers in 31 entities across six continents, results of our multilevel theoretical model provide innovative theoretical, empirical, and practical implications to the field of business ethics, corruption, and dishonesty.

Theory and Hypotheses

Money and Money Attitude

Money and its meaning. Among numerous predispositions related to corruption or dishonesty (integrity, moral identity, self-control, empathy, cognitive moral development, and psychopathology) (Ashforth et al. 2008; Dineen et al. 2006; Kish-Gephart et al. 2010), researchers studied effects of money and its meaning (Ariely 2008b; Gino and Pierce 2009a, b) on cheating and corruption. For example, children from poor economic backgrounds overestimate the size of a coin (Bruner and Goodman 1947). In dual-career families, college students’ money anxiety is influenced by both paternal and maternal money anxiety (Lim and Sng 2006).

Money, as a tool, is instrumental in satisfying biological and psychological needs (Lea and Webley 2006). To some, money is metaphorically a powerful, addictive, insatiable drug because drug addicts require larger dosages to maintain the same level of “high” (state of euphoria) or utility of money (hedonic treadmill). Thinking about money activates feelings of self-sufficiency leading to the desire to be independent, reduce requests for help, donate less money to charity, and keep a large physical distance between themselves and others (Vohs et al. 2006). Counting 80 $100 bills (compared to 80 pieces of paper) reduces people’s physical pain (Zhou et al. 2009). Anticipation of pain heightens the desire for money (Zhou and Gao 2008).

The visible presence of abundant wealth ($7000 in $1 bills piled on two tables) provokes a feeling of “envy toward wealthy others” that, in turn, causes a significantly higher percentage of participants to engage in and a much larger magnitude of cheating for personal gains than those without exposure to such abundance of money (Gino and Pierce 2009b, p. 142). We conclude that people’s intentions and behaviors are subject to many subtle cues at several levels of the environment (Ariely 2008a; Özbek et al. 2015). Financial resources, experiences, and culture at the individual, organization, and entity levels shape our deeply rooted monetary beliefs and values which provoke or curb self-interest and incite unethical or ethical behaviors, respectively. All these studies suggest that exposure to money causes people to engage in dishonesty (Welsh and Ordóñez 2014). However, we argue that researchers have overlooked important individual differences: When people react to the exposure of money, their deeply rooted monetary values play a role here.

The love of money (LOM). Attitudes predict behavior effectively only when there is a high correspondence between the attitude object and the behavioral option (Ajzen 1991; Grant 2008; Tang and Baumeister 1984). For the past several decades, researchers have examined numerous money-related attitudes and measures in the literature (Furnham and Argyle 1998; Mitchell and Mickel 1999; Srivastava et al. 2001; Tang 1992; Wernimont and Fitzpatrick 1972; Yamauchi and Templer 1982). Most lay people are familiar with the love-of-money construct due to one of the most well-known propositions—“the love of money is the root of all evils” (Tang and Chiu 2003). Tang and his associates (2006a, b) and Tang (1992, 2010) examined different meanings of money and defined love-of-money construct conceptually as subjective and positive attitudes toward money with affective, behavioral, and cognitive components (or aspirations of money, Easterlin 2001).

It is empirically defined as a multidimensional individual difference variable with several subconstructs. This LOM construct captures people’s desire to be rich (Rich), behavioral intention energized by money (Motivator), and cognitions that money is important and power (Importance, Power) (Malhotra and Gino 2011; Sardžoska and Tang 2012). We include Factor Power in this study because power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely (Lord Acton’s letter to Bishop Mandell Creighton in 1887; see also Tang et al. 2015). The love of money construct is one of the most well-developed and systematically used constructs of money attitude (Colquitt et al. 2011; Mitchell and Mickel 1999), mildly related to materialism (Belk 1985; Kasser 2002; Lemrová et al. 2014; Tang et al. 2014), and differs from greed (Cozzolino et al. 2009). A high LOM score is related to a winner-take-all mentality—the Matthew EffectFootnote 4 (Merton 1968; Tang 1996). It predicts unethical behavior intention in panel studies (Tang 2014; Tang and Chen 2008; Tang et al. 2013) and actual cheating behaviors (Chen et al. 2014). Specifically, Factor Rich predicts the amount of cheating, whereas Factor Motivator predicts the percentage of cheating (cheating/total performance) (Chen et al. 2014). This construct has been substantiated in empirical studies across more than three dozen entities around the world (e.g., Erdener and Garkavenko 2012; Gbadamosi and Joubert 2005; Lim and Teo 1997; Nkundabanyanga et al. 2011; Tang et al. 2006a, b, 2008a, b, 2011, 2013; Wong 2008), in a different religion—Buddhist five percepts (Ariyabuddhiphongs and Hongladarom 2011), and cited in influential reviews (Kish-Gephart et al. 2010; Mickel and Barron 2008; Mitchell and Mickel 1999; Zhang 2009) and in numerous textbooks (Colquitt et al. 2011; Furnham 2014; McShane and Von Glinow 2008; Milkovich et al. 2014; Newman et al. 2017; Rynes and Gerhart 2000; Scandura 2016).

Dishonesty

Fraud causes a loss of $3.7 trillion a year globally. The perpetrator’s level of authority is related to fraud losses (Report to the Nations 2014). Corruption implies “a willful perversion of order, ideals, and, perhaps most important, trust—a moral deterioration” (Ashforth et al. 2008, p. 671; Gilbert and Tang 1998; Gorodnichenko and Peter 2007). It is impossible to directly measure actual corruption in the public or private sectors because most behaviors are performed in private, except in formal criminal investigations of corruption cases, police records (Fisman and Miguel 2007), and laboratory experiments (Ariely 2008a; Chen et al. 2014). However, researchers usually receive what they ask for and people are willing to provide accurate information for specific questions in an anonymous survey (Richman et al. 1999; Schoorman and Mayer 2008). De Jonge and Peeters (2009) and Fox et al. (2007) showed the convergence of the incumbent’s self-report and the coworker’s peer-report on counterproductive work behavior. Self-reported dishonesty (intention) is a reasonable surrogate measure of corruption (behavior) (Martin et al. 2007). The corruption construct varies across cultures.

Among constructs of workplace deviance (Bennett and Robinson 2000; Skarlicki and Folger 1997; Tepper et al. 2009), counterproductive behavior (Cohen-Charash and Spector 2001; Spector and Fox 2010), corruption, CPI (Anand et al. 2004; Ashforth et al. 2008; Martin et al. 2007), and misbehavior (Ivancevich et al. 2005), we select dishonesty (Sardžoska and Tang 2012, 2015; Tang and Chiu 2003) that is a subset of organizational deviances. It includes misuse of position, power, or authority for personal or collective gain (receiving gifts, money, bribery, and kickbacks); acts committed against the company (sabotage and theft); and acts conducted on behalf of the organization (laying off employees for personal gain) (Ashforth et al. 2008; Robinson and Bennett 1995) that reflects recent scandals and corruption. It has been tested empirically in Hong Kong (Tang and Chiu 2003), Macedonia (Sardžoska and Tang 2009), and in a field study in the US (Piff et al. 2012) and cited in textbooks (e.g., Bateman and Snell 2011).

The Love of Money and Dishonesty

High love-of-money people have a large discrepancy between their desires and possessions (Lawler 1971; Michalos 1985). Many unmet needs become motivators (Kahneman and Deaton 2010; Maslow 1954). These people are vulnerable to foolish and harmful desires, likely to fall into temptations (Baumeister 2002), reduce their moral and ethical standards, and exhibit high dishonesty. We illustrate our rational below.

Factor Rich (the affective component) is the most important subconstruct of LOM because most people want to be rich and have an abundance of money (Gino and Pierce 2009b). To some, money is an insatiable drug: The more they have, the more they want. Monetary experience is relative, but consumption is absolute (Hsee et al. 2009). When the rich envy the superrich (Nickerson and Zenger 2008), feelings of inequity (Gino and Pierce 2009b) lead them to steal “in the name of justice” (Cohen-Charash and Spector 2001; Greenberg 1993, 2002; Simons and Roberson 2003). American adult consumers who desire to be “rich” condone questionable consumer activities (Vitell et al. 2006). Similarly, public employees’ high love of money leads to compromised ethical standards in Swaziland (Gbadamosi and Joubert 2005).

As a motivator (the behavioral component) (Maslow 1954), money leads to movements (Herzberg 1987). Whatever gets measured (paid) gets done (Ariely 2010; Jenkins et al. 1998). According to Locke et al. (1980), nothing comes even close to money. When people were rewarded for finding insect parts in a food processing plant, innovative employees brought insect parts from home to add to the food just before they removed them and collected the bonus (Milkovich et al. 2014). High turnover helps people get paid at the current market rate (Tang et al. 2000). When money is a motivator, Malaysian Christians are less critical of unethical practices (Wong 2008).

Cognitively, money is important (Tang 1992) and represents power (Lemrová et al. 2014). To some, money is how we compare, a score card (Adams 1963). Many cannot resist the power of money and want to keep receiving money, power, success, and maintain their life style that come with the job (Badaracco 2006) which leads to the illicit use of their position or power for personal or collective gain (Ashforth et al. 2008). Love of money predicts unethical intention and cheating (Chen et al. 2014; Tang and Chiu 2003). In the present study, we focus on two potential moderators. We assert: Individuals frame their dishonesty (corruption), consciously and unconsciously, in the context of CEV and CPI, respectively.

Corporate Ethical Values (CEV, Level 1)

Most people in organizations look to the social context to determine what is ethically right and wrong (Bandura 1986; Bandura et al. 1996), obey authority figures (Litzky et al. 2006; Milgram 1974) and laws, and do what is rewarded (Gentina et al. 2015; Skinner 1972; Treviño and Brown 2004). Social norms, ethical cultures, and reward/punishment policies strongly shape people’s ethical intentions (Aquino et al. 2009; Fisman and Miguel 2007). Perceptions of corporate ethical values (CEV) are considered as the formal/informal policies on ethics in organizations (Hunt et al. 1989) that help establish the standards and promote ethical behaviors (Treviño et al. 2000). Practically, managers have more control over the work environment than employees’ values in organizations (Anand et al. 2004). Following suggestions in the literature (Ajzen 1991; Treviño, 1986), strong corporate ethical values (CEV) deter unethical behavior (Baker et al. 2006), organizational misbehavior (Vardi and Weitz 2004), counterproductive behavior (Wimbush et al. 1997), and dishonesty (Vitell and Hidalgo 2006). To a large extent, unethical cultures, informally created by CEOs and top executives at the organization level, had caused ethical lapses and corporate scandals at Enron, WorldCom, and Tyco. We argue that perceptions of ethical values at the organization level moderate the relationship between managers’ love of money and dishonesty.

High love-of-money individuals have higher Machiavellianism (Christie and Geis 1970; Tang and Chen 2008) and are more likely to use manipulative strategies, take high risks (Tang et al. 2008a, b), and engage in unethical behavior than their low love-of-money counterparts (Kish-Gephart et al. 2010). With low corporate ethical values, unauthentic executives consciously or unconsciously encourage high love-of-money managers to adopt aggressive and devious means to achieve goals (Tang and Liu 2012; Wilson et al. 1996), fall into unethical temptations (Tang et al. 2013), and escalate their corruption and dishonesty significantly. We assert: High (low) corporate ethical values at the organization level curb (boost) managers’ dishonesty, i.e., CEV is a moderator.

Corruption Perceptions Index, CPI (Level 2)

High CPI entities. Transparency International defines corruption as the abuse of entrusted power for private gain in the public sector. However, when the public sector is corrupt, it may spillover to the private sector because corruption occurs between the government in the public sector and business organizations in the private sector. Entities with high CPI scores have high levels of economic development (Gross Domestic Product, GDP per capita), long-established liberal democracy, free press, power sharing, information transparency, sociopolitical stability, strong ethical culture of law abidance, and low corruption (Sorensen 2002; Treisman 2007). Economic, legal, political, and social infrastructures promote ethically responsible practices (Campbell 2007) and stewardship behaviors; supplant opportunism; inculcate social norms, values, and expectations (Davis et al. 1997); and deter dishonesty (Victor and Cullen 1988).

In high CPI entities, the cost of corruption outweighs the benefit (Tepper et al. 2007). Executives’ corruption and scandals have been publicized in the media, textbooks, and case studies. To them, the financial gains do not justify the loss of freedom, dignity, integrity, and reputation in their lives (Gomez-Mejia et al. 2005). In high CPI entities, managers also pay attention to their corporate ethical values at the organization level. Since high (low) corporate ethical values curb (boost) dishonesty, we expect that managers in good barrels (high CEV/high CPI) have the lowest magnitude of dishonesty. The abundance effect (Gino and Pierce 2009b) suggests that with visible money, managers develop strong feelings of envy that trigger them to engage in corruption and dishonesty. We posit that the intensity of dishonesty is the strongest for high love-of-money managers exposed to low corporate ethical values in high CPI entities. Following prospect theory, this may reflect one of the fourfold pattern of risk attitudes: risk seeking for losses of high probability (Kahneman 2011).

Low CPI entities. Corruption is a way of life in low CPI entities. People take corruption for granted. Scarce resources make it difficult for them to earn money legally. Further, they have nothing to lose (freedom, dignity, integrity, and reputation), but much temptation to covet a thing (Drori et al. 2006; Vynoslavaska et al. 2005). Visible inequality breeds more inequality (Gachter 2015). Political or public office has become a viable means of extending personal wealth and political power of the ruling class (kleptocracy—rule by thieves, Grossman 1999), or obtaining the license to corrupt (Klotz and Bolino 2013). High love-of-money managers climb to the top and get rich first. All, but the richest, feel underpaid—the rich envy the superrich. Bad apples crowd out good apples (Frey and Jegen 2001; Liu and Tang 2011) and become corrupt with a winner-take-all mentality.

In bad barrels, disingenuous executives with low personal integrity and character encourage high love-of-money individuals to apply deeply rooted expediency, manipulation, exploitation, and deviousness characters that are devoid of the traditional virtues of trust, honor, and decency, and adopt aggressive methods to achieve goals (Wilson et al. 1996) leading to the highest magnitude of dishonesty (Tang and Liu 2012). Thus, managers in bad barrels (low CEV/low CPI) have the highest magnitude of dishonesty. Further, managers with mixed ethical social norm, i.e., mixed barrels (high CEV/low CPI or low CEV/high CPI), have a moderate magnitude of dishonesty that falls between the good and bad barrels. We test our three-way interaction effect (love of money, corporate ethical values, and CPI) on dishonesty, on an exploratory basis:

Hypothesis 1

There is a significant cross-level, three-way interaction effect.

Hypothesis 1a

Managers in good (bad) barrels have the lowest (highest) magnitude of dishonesty.

Hypothesis 1b

The intensity (slope) between love of money and dishonesty is the strongest for managers with low corporate ethical values (CEV) in high CPI entities.

Methods

Sample and Procedure

In our study, researchers adopted the English survey or translated it to their native language using the multistage translation/back-translation procedure (Brislin 1980), and collected data using random sampling, convenience samples, or a systematic snowball approach (asking full-time managers in various graduate (MBA/PhD) programs to collect data from their colleagues in various organizations) in a single or multiple cities in both public and private sectors. Participants completed the surveys voluntarily, anonymously, and without financial reward and forwarded them directly to the researchers. The return rate varied between 45 % and 100 %. The research team collected data from 6586 managers (Level 1) in 32 geopolitical entities (Level 2) across six continents. For the present study, we deleted missing data (Italy) and obtained usable data from 6382 managers (Level 1) in 31 entities (Level 2). Most participants had job titles such as executive, senior manager, logistics coordinator, accountant, financial director, product manager, sales manager, director of communication, engineer, R&D supervisor, HR manager, purchasing officer, assistant marketing manager, designer, etc. In general, managers were 34.66 years old (SD = 9.87), 50.6 % male, with 15.35 years of education (SD = 2.65) and an average income of US$14,199.15 (SD = $18,035.51). The average sample size was 205.9 per entity.

Measures

LOM. We selected the 12-item, 4-factor Love of Money Scale (Sardžoska and Tang 2012; Tang and Chiu 2003; Tang et al. 2015) with Factors Rich, Motivator, Importance, and Power (sample items: I want to be rich; I am motivated to work hard for money; money is an important factor in everyone’s life; money gives one considerable power). We used a 5-point Likert scale with the following scale anchors: strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), neutral (3), agree (4), and strongly agree (5).

CEV. We adopted corporate ethical values (CEV) (Hunt et al. 1989) and used the following scale anchors: disagree strongly (1), disagree (2), neutral (3), agree (4), and agree strongly (5). We applied the following items: In order to succeed in my company, it is often necessary to compromise one’s ethics (reversed scored). Top management in my company has let it be known in no uncertain terms that unethical behaviors will not be tolerated. If a manager in my company is discovered to have engaged in unethical behaviors that result primarily in personal gain (rather than corporate gain), he or she will be promptly reprimanded. If a manager in my company is discovered to have engaged in unethical behaviors that result primarily in corporate gain (rather than personal gain), he or she will be promptly reprimanded.

Dishonesty. We measured dishonesty by using the following scale anchors: very low probability (1), low probability (2), average (3), high probability (4), and very high probability (5) and asking the following seven question (Tang and Chiu 2003; Tang and Tang 2010; Sardžoska and Tang 2015): If you were in a given situation, what is the probability that you would engage in this activity? Reveal company secrets for several million dollars; accept money, gifts, and kickbacks from others; sabotage the company to get even due to unfair treatment; lay off employees to save the company money and increase my personal bonus; abuse the company expense accounts and falsify accounting records; overcharge customers to increase sales and to earn higher bonus; and take merchandise and/or cash home. We used different anchors to deliberately avoid common method bias (Podsakoff et al. 2003). A short version, with the first four items, was correlated with the four-item corruption measure from the World Values Survey (claiming government benefits to which you are not entitled, avoiding a fare on public transportation, cheating on taxes if you have a choice, accepting a bribe in the course of their duties) among 151 Chinese MBA students (r = .74, p < .01), providing construct validity.

CPI. We searched Transparency International’s (TI) Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), the Bribe Payers’ Index (BPI), the Global Corruption Barometer (GCB), and Global Corruption Report (Global Index of Bribery, GIB) as well as the World Values Survey. In this study, from two additional sources, we adopted World Bank’s GDP per capita and TI’s CPI because only these two indices have key data for all of our 31 entities. Further, most participants completed all attitudinal measures without knowingly aware of CPI and GDP at the entity level because our survey questionnaire did not mentioned these constructs.

Analysis. We used (SPSS/Amos, Version 18) and the following criteria for configural invariance (passing 5 out of 6 criteria): (1) Chi-square and degrees of freedom (χ 2 /df), (2) incremental fit index (IFI > .90), (3) Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI > .90), (4) comparative fit index (CFI > .90), (5) standardized root mean square residual (SRMSR < .10), and (6) root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA < .10) (Vandenberg and Lance 2000). Metric invariance is achieved when the differences between unconstrained and constrained multigroup confirmatory factor analyses (MGCFAs) are not significant (ΔCFI/ΔRMSEA ≤ .01, Cheung and Rensvold 2002). We employed mixed analysis (SPSS) for our cross-level analysis.

Results

Researchers achieve higher levels of power (1 − β) and contributions by employing larger samples at the group level (Level 2) rather than individual level (Level 1) (Scherbaum and Ferreter 2009). Our data analysis revealed that the current sample represented the population reasonably well because there was no difference (t = .447, p = .658) between average self-reported income at the entity level ($12,189.48) and GDP per capita ($12,736.23) and the correlation between the two was significant (r = .68, p < .001). Average income (r = .66, p < .001) and GDP per capita were correlated with CPI (M = 4.89) (r = .86, p < .001). Table 1 shows the mean, standard deviation, and correlations of major variables. Dishonesty was related to high love of money and low corporate ethical values and people who were young, male, highly educated, and in the public sector.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) Results

Table 2 (Model 1) showed a good fit between our measurement model of love of money (LOM) and data for the whole sample (χ 2 = 436.291, df = 50, p < .01, IFI = .99, TLI = .98, CFI = .98, SRMSR = .03, RMSEA = .03). Factor Rich (.84) had the highest factor loading followed by Motivator (.67), Importance (.67), and Power (.51), supporting findings in the literature. We used SPSS to analyze our cross-level model and combined all items into an overall index (α = .83). For the corporate ethical values, we also combined all items of CEV into an overall index (α = .64). There was a good fit for the 7-item dishonesty scale (Model 3) (α = .87).

Measurement invariance. We examined measurement invariance across three CPI groups using a three-way split: (A) high CPI: CPI > 5.0, n = 2761, 13 entities—Australia, Belgium, France, Hong Kong, Malta, Malaysia, Oman, Portugal, Singapore, Slovenia, Spain, Taiwan, and the USA; (B) medium CPI: 5.0 = CPI ≥ 3.5, n = 1269, 8 entities—Brazil, Bulgaria, Hungary, Mexico, South Africa, South Korean, Thailand, and Turkey; and (C) low CPI: CPI ≤ 3.4, n = 2352, 10 entities—Croatia, China, Democratic Republic of Congo, Egypt, Macedonia, Nigeria, Peru, the Philippines, Romania, and Russia. Table 2 shows configural invariance of love of money, corporate ethical values, and dishonesty for the three CPI groups in nine analyses (Models 4–12). For metric invariance, we used multiple group confirmatory factor analysis (MGCFA) and compared unconstrained and constrained models across three CPI groups simultaneously in six analyses (Models 13–18). All results provided good support for our measurement models. For corporate ethical values (CEV), results showed excellent fit between our measurement model and our data for the whole sample (Model 2) and the high and medium CPI groups for configural invariance, but weak results in the low CPI group (Model 9). This was probably due to smaller sample size and huge cultural differences in the reward and punishment of unethical behavior (corporate ethical cultures) across entities in the low CPI group where the most corruption exists. The root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) tends to over-reject a true model due to small sample size and model complexity (Tang et al. 2006a). We achieved metric invariance for all three measures due to nonsignificant differences between unconstrained and constrained models using MGCFA.

Common method variance bias (CMV). Following Podsakoff et al.’s (2003) suggestions, we examined the issue of CMV in two steps. First, Harman’s single-factor test examines the unrotated factor solution involving all items of interest in an exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Results showed six factors with eigenvalues greater than one. We listed the scale/factor and the amount of variance explained (total = 62.78 %) as follows: LOM—Importance/Power (cognition 21.16 %), dishonesty (16.33 %), CEV (8.39 %), LOM—Rich (affect 6.14 %), LOM—Motivator (behavior 6.00 %), and items with cross loading (4.77 %). Our predictors and criterion were in separate factors of our EFA. Thus, CMV was not a concern.

Second, we compared the measurement model of all measures with and without the addition of an unmeasured latent common method variance (CMV) and the former (with the latent CMV factor) should not significantly improve the goodness of fit than the latter. Table 2 (Models 19 and 20) suggested that minor common method bias may suspiciously exist. We argue that the common method variance (CMV) bias should not be a concern for this cross-level interaction effect examined in this study because we obtained data from managers (Level 1) in 31 different geopolitical entities (Level 2) (Spector 2006). We also used scales with different anchors for predictors and a criterion to reduce the CMV bias. It was not a source of spurious interactions.

Cross-Level Analysis

In our data analysis, we had 6382 managers at Level 1 and 31 entities at Level 2. For our within-level analysis, we used love of money (LOM), corporate ethical values (CEV) (two main effects), and the interaction effect (LOM * CEV, both group mean centered at the entity level before the creation of the interaction effect) to predict dishonesty. The second-level variable was Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). For our cross-level analysis, we investigated the two additional two-way interaction effects (LOM * CPI and CEV * CPI) and one three-way interaction effect (LOM * CEV * CPI) on dishonesty (see Table 3).

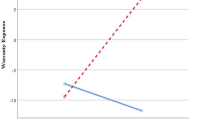

Cross-level, three-way interaction effect. Our cross-level, three-way interaction effect on dishonesty was significant (t = −2.54, p < .01) (Table 3). Following Aiken and West (1991) and Dawson and Richter’s (2006) suggestions, we plotted the three-way interaction effect and compared six pairs of slopes using t tests. The slope reveals the intensity of the relationship between love of money and dishonesty; whereas the intercept suggests the magnitude of its impact on the dishonesty. A steep (gentle) slope implies high (low) intensity; whereas a high (low) intercept suggests high (low) magnitude of dishonesty. Further, we label the combination of high CEV and high CPI as “good barrels,” low CEV and low CPI as “bad barrels,” and either high CEV and low CPI or low CEV and high CPI as “mixed barrels.”

Magnitude. Overall, managers in bad barrels (low CEV/low CPI) had the highest magnitude (intercept) of dishonesty (Line 4, top of Fig. 1). Those in good barrels (high CEV/high CPI) had the lowest magnitude of dishonesty (see Line 1, bottom of Fig. 1), as expected. Further, managers in mixed barrels (Line 2—high CEV/low CPI and Line 3—low CEV/high CPI) had medium magnitude of dishonesty which fell between Lines 4 and 1.

Intensity. Managers with low CEV in high CPI entities had the strongest intensity (slope) between love of money and dishonesty—Slope 3. Managers in the bad barrels (Slope 4) had the weakest intensity. The difference between the two was significant (t = 4.75, p < .001). For those with high CEV, the intensity of dishonesty was identical regardless whether they were in the high or low CPI entities (Slope 1 vs. Slope 2: t = .00, p = 1.00). However, the former (Slope 1) had lower magnitude of dishonesty than the latter (Slope 2). The intensity was higher for managers with high CEV in both high and low CPI entities than those in bad barrels (low CEV/low CPI) (Slope 1 vs. Slope 4: t = 2.95, p < .01; Slope 2 vs. Slope 4: t = 2.21, p < .05; respectively). These results supported our Hypotheses.

Discussion

We craft a multilevel theoretical model and identify a significant three-way interaction effect: The moderating effect of corporate ethical values on the positive relationship between love of money and dishonesty varies across levels of corrupt culture (CPI). Our new and value-added theoretical, empirical, and practical implications are presented below.

Theoretical implications. We provide the following theoretical contributions. First, our significant three-way interaction effect shows that the relationship between love of money and dishonesty is moderated by corporate ethical values at Level 1 and CPI at Level 2, supporting and expanding the interactionist theory of ethical decision making (Kish-Gephart et al. 2010). Second, love of money is positively related to dishonesty, supporting the “attitude-to-behavioral intention” aspect of theory of planned behavior (Ajzen 1991; Grant 2008; Tang and Baumeister 1984) and the proposition that the love of money is the root of all evils, given the fact that dishonesty is a small part of evil examined in this study (Tang and Chiu 2003).

Third, we explore the magnitude (intercept) of dishonesty. In good barrels (high CEV/High CPI), managers maintain the lowest magnitude of dishonesty (Slope 1), exhibiting risk aversion of high probability. In bad barrels (low CEV/low CPI), managers display the highest magnitude of dishonesty (Slope 4), showing risk seeking of low probability. Since good and bad barrels create the highest and the lowest magnitudes of dishonesty, respectively, it is clear that managers do frame CEV at the micro-level and CPI at the macro-level, simultaneously.

Fourth, interestingly enough, managers in mixed barrels have medium levels of dishonesty which fall between the good and bad barrels. If one of the two (CEV and CPI) ethical cultures is low, it creates almost identical results. Intuitively, it appears that CEV and CPI are two separate, independent, and interchangeable variables that may have similar impacts on managers’ dishonesty. Incorporating two levels of the subjective social norm (CEV at the organization level and CPI at the entity level) enhances our theoretical understanding of people’s dishonesty across cultures. An important implication is that since executives may have much stronger control over CEV at the organization level than CPI at the entity level, it is imperative that they curb dishonesty by instilling strong corporate ethical cultures in organizations. More empirical research regarding these two variables is warranted.

Fifth, the intensity (slope) between love of money and dishonesty offers additional interesting and counterintuitive theoretical contributions. We provide the following new paradox: With high CEV, the intensity for dishonesty is identical for managers in either high or low CPI entities. With low CEV, the intensity for dishonesty was the highest for managers in high CPI entities (risk seeking of high probability) and the lowest for those in low CPI entities (risk aversion of low probability). Advancing our fourth argument, mentioned above, regarding interchangeable constructs, we argue high or low corporate ethical values create different patterns of results on dishonesty in high or low CPI entities. We offer our plausible explanations for the highest and the lowest slopes below:

Sixth, in high CPI entities, abundant money, wealth, resources, and opportunities exist. Due to the abundance effect, people develop a high sense of envy toward the rich. When ethical cultures are missing at the organization level, many high love-of-money managers cannot resist the temptations, take advantages of the situation, and have the strongest intention to take risks. For people in the high CPI entities, low corporate ethical values may fuel the fire of corruption and dishonesty (Grant 2008; Liu and Tang 2011) causing them to have the highest intensity of dishonesty. Our interpretation of these findings supports the notion of “risk seeking for losses of high probability.” The slope of the function is steeper in the negative domain because the response to a loss is stronger (Kahneman and Tversky 1979). Many not only turn a blind eye to others' corruption but also spread the viruslike infection to surrounding people in the corrupted local environment. Following behavioral economics, visible inequality breeds more inequality (Gachter 2015). This notion helps us explain the Enron effect (discussed later).

On the other hand, due to scarce resources and opportunities in low CPI entities, corruption is a way of life. Since almost all people in the society are corrupted, to some extent; they go with the flow and become corrupt. However, they do not do it for the love of money. The probability of getting caught for dishonesty is relatively low in low CPI (highly corrupted) entities, creating the feelings of low probability and/or low risks. Interestingly enough, managers in the bad barrels (low CEV/low CPI) have the lowest intensity of dishonesty due to love of money, but the highest magnitude of dishonesty overall.

People in low CPI entities have low GDP and are poor. In fact, our Table 1 shows that CPI and GDP are significantly and positively correlated (r = .88, p < .01). Following prospect theory, being poor is living below one’s reference point. The poor are “always in the losses” (Kahneman 2011, p. 298). In low CPI entities, the low intensity of dishonesty may represent managers’ “risk aversion for losses of low probability.” Taken together, we conclude: For intensity of dishonesty, love of money plays a major role in mixed barrels (low CEV/High CPI), but only a minor role in bad barrels (low CEV/low CPI). We reveal love of money as a double-edged sword with multiple consequences and expand several motivation theories (Herzberg 1987; Maslow 1954) and prospect theory (Kahneman and Tversky 1979).

These managers may have the strongest winner-take-all mentality (the Matthew Effect; Merton 1968)—treating corruption as a game and a sense of entitlement, winning the most in a corrupt environment, considering money as an addictive, insatiable drug (the more they have, the more they want), requiring larger dosages to maintain the same level of “high” or utility of money (Lea and Webley 2006), and becoming members of the ruling class/kleptocracy (Grossman 1999). Bad apples appear by the bushel in bad barrels (Pinto et al. 2008) (Slope 4). They probably do not mind taking the risks (Gomez-Mejia et al. 2005). Even incarcerated, some may live comfortably with all the luxuries. Money talks everywhere, even in prisons.

Seventh, in good barrels (high CEV/high CPI), strong ethical cultures at the organization and entity levels and reward and punishment in the social environment discourage dishonesty (Fisman and Miguel 2007). They do not want to take the risks and lose their freedom, dignity, integrity, and reputation in their lives. The cost of corruption outweighs the benefit (Tepper et al. 2007).

Finally, we summarize our contributions below. Our findings help researchers (1) recognize the importance of testing the three-way interaction effect on dishonesty; (2) expand the theory of planned behavior (TPB) and prospect theory from an individual-level theory to a multilevel theory; (3) integrate TPB with the person–situation interactionist theory by incorporating corporate ethical values and CPI at the micro and macro-levels, respectively (Kish-Gephart et al. 2010); (4) tease out good and bad apples’ unseen behavioral patterns in good or bad barrels and make them clearly visible in a new perspective; (5) understand that CEV and CPI have a strong impact on the intensity and magnitude of dishonesty, respectively; (6) identify not only contributions but also boundaries of several theories (e.g., Ajzen 1991; Herzberg 1987; Maslow 1954); and (7) incorporate contextualization, help develop robust theories, capture the complexity of organizational phenomena, and offer real-world relevance to the management field (Bamberger 2008).

Empirical contributions. Our CEV and CPI help practitioners understand love of money to dishonesty relationship based on a large sample of 6382 managers in 31 geopolitical entities across six continents. Results regarding measurement models for the whole sample and measurement invariance across CPI groups enhance the generalizability of our findings and offer confidence to future researchers in using these scales in under-researched areas of the world (Kirkman and Law 2005). Our counterintuitive discoveries (Bartunek et al. 2006) are impossible to achieve without a large sample size at both levels—Level l and Level 2.

Practical implications. Our results provide partial support for the proposition that the love of money is the root of all evils, considering dishonesty as a small part of evil. It is difficult to manage managers’ love of money because people bring dispositional values to organizations (Staw et al. 1986; Tang 2014). Although executives cannot manipulate or change directly managers’ love of money—a deeply rooted value or attitude—they can still properly manage it in organizations. People need money (a hygiene factor) continuously to maintain their lives (Herzberg 1987). Research suggests that the relationship between income and love of money is negative among highly paid professionals in Hong Kong (Tang and Chiu 2003), non significant among adequately paid males and Caucasians (Tang et al. 2005), but positive among underpaid females and African-Americans in the US (Tang et al. 2006). Females and African-Americans have lower pay than their male and Caucasian counterparts, respectively. Underpaid people lack feelings of self-sufficiency and love money much more than those who are not. “People do work for money—but they work even more for meaning in their lives” (Pfeffer 1998, p. 112). Objective income, financial experiences, and ethical cultural values may shape or modify one’s love of money and behavior.

Many multinational corporations (MNCs) have become increasingly interested in improving productivity and profits, reducing labor costs, and managing human resource effectively across borders. Due to economic down turn, downsizing, and pay cuts, fewer employees shoulder more responsibility with lower pay. Consequently, organizational trust decreases and dishonesty is on the rise (Gilbert and Tang 1998). These contextual variables may trigger desperate and disgruntled people to retaliate (Skarlicki and Folger 1997; Tepper et al. 2009), get even, or become corrupt. In order to eradicate corruption or dishonesty, boost business ethics globally, and maintain sustainable development in the competitive market, executives must be aware of this trap (love of money, CEV, and CPI are three critical ingredients of corruption and dishonesty), avoid the most commonly recognized and deeply rooted temptations (i.e., ignore the importance of corporate ethical values (CEV) and pay less attention to CEV than they deserve), and manage all stakeholders (stockholders, managers, employees, suppliers, and customers) fairly and well to reduce dishonesty and increase profits. It pays to enhance the ethical cultures at the organization level and curb corruption.

Executives need to control their malleable compensation systems, pay managers fairly and well, conduct annual surveys in order to monitor love of money, CEV, firm-level pressures (Martin et al. 2007), different forms of temptations across cultures, valorize corporate ethical values, and inspire personal integrity (Simons 2002). Also, they need to implement organizational corruption control elements—bureaucratic control, punishment, incentive alignments, legal/regulatory sanctioning, social sanctioning, vigilance controls, self-control, and concertive controls (Lange 2008)—to curb corruption. Doubling the civil servants’ wage may improve two points on the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) (Rijekeghem and Weder 1997). Regardless of CPI, increasing corporate ethical values in organizations may also greatly reduce corruption because most people do want to receive reward and avoid punishment in the social context (Fisman and Miguel 2007). Executives, in fact, have more control over corporate ethical values at the organization level than CPI at the entity level. Future research may test this proposition empirically and investigate the changes in love of money, CEV, and CPI on corruption empirically over time.

The Enron Effect. With low CEV, the intensity for dishonesty was the highest for managers in high CPI entities (risk seeking of high probability). We label this as the Enron effect. Executives have a lot of financial data in organizations. When people are primed with different forms/notions of money (the abundance effect; Ariely 2008a; Gino and Pierce 2009b; Vohs et al. 2006), rich executives compare their pay with that of others, develop strong feelings of envy toward the superrich. Since the average tenure for CEOs is about 7 years, many try to get the most out of their short tenure (i.e., strike while the iron is hot). People may pay more attention to the immediate ethical cultures at the organization level (CEV) than at the entity level (CPI). When authentic leaders with character and integrity (ASPIRE, Tang and Liu 2012), corporate ethical values (Baker et al. 2006), and strong enforcement of laws, policies (Fisman and Miguel 2007) do not exist, people ignore the ethical culture at the entity level, fall into temptation (Baumeister 2002; Martin et al. 2007; Tang and Liu 2012), and display the highest intensity and also high magnitude of dishonesty. They see trees but not the forest.

Due to their high level of authority and power, executives in high CPI entities with low CEV may not only have the highest intensity but also the highest magnitude of corruption similar to those in the bad barrels (kleptocracy). Some thought they were doing good deeds for the corporation and society (Levine 2005), yet boosted their appetite further, engaged in riskier behavior, and developed an over-and-above normal “dependency” on a constant “high” from wealth because they cannot resist the flow of money, power, and life style in corrupt and infectious organizations (Badaracco 2006). It is not a lack of intelligence, but a lack of wisdom or virtue that causes one to become corrupt (Feiner 2004; Tang and Chen 2008). “When cheating is one step removed from cash,” people tend to rationalize and justify their dishonesty easily. “Such latitude is the force behind the Enrons of the world” (Ariely 2008a, p. 24).

All the world’s entities are on the same boat of economic growth and prosperity. Corruption damages economic efficiency and sustainability. The President of the US signed the Sarbanes–Oxley Act into law on July 30, 2002. In low CPI entities, such laws may not exist. Without stable infrastructures, the uncertainty associated with economic transactions imposes a heavy risk premium that discourages foreign direct investment (FDI). Executives must be careful when they do business in corrupt entities and not spurn the poor at the bottom of the global economic pyramid because they may become new sources of growth in the earliest stage of rapid economic development.

Limitations. We measured managers’ propensity to engage in dishonesty, not the actual behavior that can be verified in laboratory and field studies (Ariely 2008a). However, research shows that love of money predicts dishonesty and actual cheating behaviors in experiments (Chen et al. 2014), experimental subjects are not different from regular people or managers (Exadaktylos et al. 2013), the incumbent’s self-report and the coworker’s peer-report converge on counterproductive behavior (De Jonge and Peeters 2009; Fox et al. 2007), self-reported dishonesty is a reasonable surrogate of dishonest behaviors. We did not select 31 geopolitical entities from the global economic pyramid or the sample from each entity randomly. Our samples represent the populations reasonably well. Our cross-sectional data did not prove a cause-and-effect relationship. The economy, unemployment rate, moral development, public/private sector, and religion of each entity have an impact on corruption and dishonesty. Love of money and dishonesty may be best addressed by mono-method self reports. Future researchers may incorporate corruption-control and longitudinal data from multiple sources.

Conclusion. In this research, we test a multilevel theory of dishonesty using 6382 managers in 31 geopolitical entities across six continents. The positive relationship between love of money and dishonesty is moderated by two separate levels of subjective norm—corporate ethical values (CEV) at the micro-level and Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) at the macro-level. As expected, in good barrels (high CEV and high CPI), mixed barrels (high CEV/low CPI or low CEV/high CPI), and bad barrels (low CEV and low CPI), managers display low, median, and high magnitude of dishonesty, respectively. With high CEV, the intensity of the relationship between love of money and dishonesty is the same across cultures. With low CEV, the intensity is the highest in high CPI entities (risk seeking of high probability)—the Enron Effect; but the lowest in low CPI entities (risk aversion of low probability). Love of money exerts a major impact on dishonesty in the specific mixed barrels (low CEV/high CPI), but a minor one in bad barrels. Managers frame the social contexts differently—CPI has a strong impact on the magnitude of dishonesty, whereas CEV has a strong impact on the intensity of dishonesty. We offer a compelling application of prospect theory using a multilevel theory and demonstrate innovative and practical implications to the field of behavioral economics and business ethics (Colquitt and Zapata-Phelan 2007).

Notes

Most “geopolitical entities” are countries or nation-states. We have data from People’s Republic of China (China), Hong Kong, and Taiwan; treat China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan as separate geopolitical entities; and use the terms geopolitical entities or entities, thereafter, in this paper.

1 Timothy 6: 10.

A high CPI score indicates a clean and ethical culture at the geopolitical entity level.

The Matthew Effect: To anyone who has, more will be given, and he will grow rich; from anyone who has not, even what he has will be taken away (Matthew 13: 12).

References

Adams, J. S. (1963). Toward an understanding of inequity. Journal of Abnormal Social Psychology, 67, 422–436.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50, 179–211.

Anand, V., Ashforth, B. E., & Joshi, M. (2004). Business as usual: The acceptance and perpetuation of corruption in organizations. Academy of Management Executive, 18, 39–53.

Aquino, K., Freeman, D., Reed, A., Lim, V. K. G., & Felps, W. (2009). Testing a social-cognitive model of moral behavior: The interactive influence of situations and moral identity centrality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 123–141.

Ariely, D. (2008a). How honest people cheat. Harvard Business Review, 86(2), 24.

Ariely, D. (2008b). Predictably irrational: The hidden forces that shape our decisions. New York: Harper/Perennial.

Ariely, D. (2010). You are what you measure. Harvard Business Review, 88(6), 38.

Ariyabuddhiphongs, V., & Hongladarom, C. (2011). Violation of Buddhist five percepts, money consciousness, and the tendency to pay bribes among organizational employees in Bangkok, Thailand. Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 33, 325–344.

Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 471–499.

Ashforth, B. E., Gioia, D. A., Robinson, S. L., & Treviño, L. K. (2008). Introduction to special topic forum: Re-viewing organizational corruption. Academy of Management Review, 33, 670–684.

Badaracco, J. L. (2006). Leadership in literature: A conversation with business ethicist Joseph L. Badaracco, Jr. Harvard Business Review, 84(3), 47–55.

Baker, T. L., Hunt, T. G., & Andrews, M. C. (2006). Promoting ethical behavior and organizational citizenship behaviors: The influence of corporate ethical values. Journal of Business Research, 59(7), 849–857.

Bamberger, P. (2008). Beyond contextualization: Using context theories to narrow the micro-macro gap in management research. Academy of Management Journal, 51, 839–846.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 364–373.

Bartunek, J. M., Rynes, S. L., & Ireland, R. D. (2006). What makes management research interesting, and why does it matter? Academy of Management Journal, 49, 9–15.

Bateman, T. S., & Snell, S. A. (2011). Management: Leading & collaborating in the competitive world (9th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Baumeister, R. F. (2002). Yielding to temptation: Self-control failure, impulsive purchasing, and consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 28, 670–676.

Belk, R. W. (1985). Materialism: Trait aspects of living in the material world. Journal of Consumer Research, 12, 265–280.

Bennett, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. (2000). Development of a measure of workplace deviance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 349–360.

Brislin, R. W. (1980). Translation and content analysis of oral and written materials. In H. C. Triandis & J. W. Berry (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (Vol. 2: Methodology, pp. 349-444). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Bruner, J. S., & Goodman, C. C. (1947). Value and needs as organizing factors in perception. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 42, 33–44.

Campbell, J. L. (2007). Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 32, 946–967.

Chen, J. Q., Tang, T. L. P., & Tang, N. Y. (2014). Temptation, monetary intelligence (love of money), and environmental context on unethical intentions and cheating. Journal of Business Ethics, 123(2), 197–219.

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 233–255.

Christie, R., & Geis, F. L. (1970). Studies in Machiavellianism. New York: Academic Press.

Cohen-Charash, Y., & Spector, P. E. (2001). The role of justice in organizations: A meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86, 278–321.

Cohn, A., Fehr, E., & Marechal, M. A. (2014). Business culture and dishonesty in the banking industry. Nature, 516, 86–89.

Colquitt, J. A., LePine, J. A., & Wesson, M. J. (2011). Organizational behavior: Improving performance and commitment in the workplace. New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Colquitt, J. A., & Zapata-Phelan, C. P. (2007). Trends in theory building and theory testing: A five-decade study of the Academy of Management Journal. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 1281–1303.

Cordano, M., & Frieze, I. H. (2000). Pollution reduction preferences of US environmental managers: Applying Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 43, 627–641.

Cozzolino, P. J., Sheldon, K. M., Schachtman, T. R., & Meyers, L. S. (2009). Limited time perspective, values, and greed: Imagining a limited future reduces avarice in extrinsic people. Journal of Research in Personality, 43, 399–408.

Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. D., & Donaldson, L. (1997). Toward a stewardship theory of management. Academy of Management Review, 22, 20–47.

Dawson, J. F., & Richter, A. W. (2006). Probing three-way interactions in moderated multiple regression: Development and application of a slope difference test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(4), 917–926.

De Jonge, J., & Peeters, M. C. W. (2009). Convergence of self-reports and coworker reports of counterproductive work behavior: A cross-sectional multi-source survey among health care workers. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46, 699–707.

Dineen, B. R., Lewicki, R. J., & Tomlinson, E. C. (2006). Supervisory guidance and behavioral integrity: Relationships with employee citizenship and deviant behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 622–635.

Drori, G. S., Jang, Y. S., & Meyer, J. W. (2006). Sources of rationalized governance: Cross-national longitudinal analyses 1985–2002. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51, 205–229.

Easterlin, R. A. (2001). Income and happiness: Towards a unified theory. The Economic Journal, 111, 465–484.

Erdener, C., & Garkavenko, V. (2012). Money attitudes in Kazakhstan. Journal of International Business and Economics, 12(3), 87–94.

Exadaktylos, F., Espin, A. M., & Branas-Garza, P. (2013). Experimental subjects are not different. Scientific Reports, 3, 1213. doi:10.1038/srep01213.

Feiner, M. (2004). The Feiner points of leadership. New York: Warner Business Books.

Fisman, R., & Miguel, E. (2007). Corruption, norms, and legal enforcement: Evidence from diplomatic parking tickets. Journal of Political Economy, 115(6), 1020–1048.

Fox, S., Spector, P. E., Goh, A., & Bruursema, K. (2007). Does your coworker know what you’re doing? Convergence of self- and peer-reports of counterproductive work behavior. International Journal of Stress Management, 14, 41–60.

Frey, B. S., & Jegen, R. (2001). Motivation crowding theory. Journal of Economic Surveys, 15, 589–611.

Furnham, A. (2014). The new psychology of money. London: Routledge.

Furnham, A., & Argyle, M. (1998). The psychology of money. London: Routledge.

Gachter, S. (2015). Behavioral economics: Visible inequality breeds more inequality. Nature, 526(7573), 333–334.

Gbadamosi, G., & Joubert, P. (2005). Money ethic, moral conduct and work related attitudes: Field study from the public sector in Swaziland. Journal of Management Development, 24, 754–763.

Gentina, E., Tang, T. L. P., & Gu, Q. X. (2015). Does bad company corrupt good morals? Social bonding and academic cheating among French and Chinese teens. Journal of Business Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2939-z.

Gilbert, J. A., & Tang, T. L. P. (1998). An examination of organizational trust antecedents. Public Personnel Management, 27, 321–338.

Gino, F., & Pierce, L. (2009a). Dishonesty in the name of equity. Psychological Science, 20(9), 1153–1160.

Gino, F., & Pierce, L. (2009b). The abundance effect: Unethical behavior in the presence of wealth. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 109, 142–155.

Gomez-Mejia, L., Wiseman, R. M., & Dykes, B. J. (2005). Agency problems in diverse contexts: A global perspective. Journal of Management Studies, 42, 1507–1517.

Gorodnichenko, Y., & Peter, K. S. (2007). Public sector pay and corruption: Measuring bribery from micro data. Journal of Public Economics, 91, 963–991.

Grant, A. M. (2008). Does intrinsic motivation fuel the prosocial fire? Motivational synergy in predicting persistence, performance, and productivity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 48.

Greenberg, J. (1993). Stealing in the name of justice: Informational and interpersonal moderators of theft reactions to underpayment inequity. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 54, 81–103.

Greenberg, J. (2002). Who stole the money, and when? Individual and situational determinants of manager theft. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 89, 985–1003.

Grossman, H. I. (1999). Kleptocracy and revolutions. Oxford Economic Papers, 51, 267–283.

Herzberg, F. (1987). One more time: How do you motivate employees? Harvard Business Review, 65(5), 109–120.

Hitt, M. A., Beamish, P. W., Jackson, S. E., & Mathieu, J. E. (2007). Building theoretical and empirical bridges across levels: Multilevel research in management. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 1385–1399.

Hsee, C. K., Yang, Y., Li, N., & Shen, L. X. (2009). Wealth, warmth, and well-being: Whether happiness is relative or absolute depends on whether it is about money, acquisition, or consumption. Journal of Marketing Research, 46, 396–409.

Hunt, S. D., Wood, V. R., & Chonko, L. B. (1989). Corporate ethical values and Organizational Commitment in Marketing. Journal of Marketing, 53, 79–90.

Ivancevich, J. M., Konopaske, R., & Matteson, M. T. (2005). Organizational behavior and management (7th ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Jenkins, G. D., Mitra, A., Gupta, N., & Shaw, D. (1998). Are financial incentives related to performance? A meta-analytic review of empirical research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 777–787.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Strass and Giroux.

Kahneman, D., & Deaton, A. (2010). High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(38), 16489–16493.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263–291.

Kasser, T. (2002). The high price of materialism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kirkman, B., & Law, K. (2005). International management research in AMJ: Our past, present, and future. Academy of Management Journal, 48, 377–386.

Kish-Gephart, J. J., Harrison, D. A., & Treviño, L. K. (2010). Bad apples, bad cases, and bad barrels: Meta-analytic evidence about sources of unethical decisions at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 1–31.

Klotz, A. C., & Bolino, M. C. (2013). Citizenship and counterproductive work behavior: A moral licensing view. Academy of Management Review, 38, 292–306.

Lange, D. (2008). A multidimensional conceptualization of organizational corruption control. Academy of Management Review, 33, 710–729.

Lawler, E. E. (1971). Pay and organizational effectiveness: A psychological view. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Lea, S. E. G., & Webley, P. (2006). Money as tool, money as drug: The biological psychology of a strong incentive. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 29, 161–209.

Lemrová, S., Reiterová, E., Fatěnová, R., Lemr, K., & Tang, T. L. P. (2014). Money is power: Monetary intelligence—love of money and temptation of materialism among Czech university students. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(2), 329–348.

Levine, D. P. (2005). The corrupt organization. Human Relations, 58, 723–740.

Lim, V. K. G., & Sng, Q. S. (2006). Does parental job insecurity matter? Money anxiety, money motives, and work motivation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1078–1087.

Lim, V. K. G., & Teo, T. S. H. (1997). Sex, money and financial hardship: An empirical study of attitudes towards money among undergraduates in Singapore. Journal of Economic Psychology, 18, 369–386.

Litzky, B. E., Eddleston, K. A., & Kidder, D. L. (2006). The good, the bad, and the misguided: How managers inadvertently encourage deviant behaviors. Academy of Management Perspectives, 20, 91–103.

Liu, B. C., & Tang, T. L. P. (2011). Does the love of money moderate the relationship between public service motivation and job satisfaction? The case of Chinese professionals in the public sector. Public Administration Review, 71(5), 718–727.

Locke, E. A., Feren, D. B., McCaleb, V. M., Shaw, K. N., & Denny, A. T. (1980). The relative effectiveness of four methods of motivating manager performance. In K. D. Duncan, M. M. Gruneberg, & D. Wallis (Eds.), Changes in working life (pp. 363–388). New York: Wiley.

Malhotra, D., & Gino, F. (2011). The pursuit of power corrupts: How investing in outside options motivates opportunism in relationship. Administrative Science Quarterly, 56(SI), 559–592.

Manning, M. (2009). The effects of subjective norms on behaviour in the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analysis. British Journal of Social Psychology, 48, 649–705.

Martin, K. D., & Cullen, J. B. (2006). Continuities and extensions of ethical climate theory: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Business Ethics, 69, 175–194.

Martin, K. D., Cullen, J. B., Johnson, J. L., & Parboteeah, K. P. (2007). Decide to bribe: A cross-level analysis of firm and home country influences on bribery activity. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 1401–1422.

Maslow, A. H. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper.

Mazar, N., Amir, O., & Ariely, D. (2008). The dishonesty of honest people: A theory of self-concept maintenance. Journal of Marketing Research, 45(6), 633–644.

McClelland, D. C. (1967). Money as a motivator: Some research insights. The McKinsey Quarterly, 4, 10–21.

McShane, S. L., & Von Glinow, M. A. (2008). Organizational behavior (4th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Merton, R. K. (1968). The Matthew effect in science. Science, 159, 56–63.

Michalos, A. (1985). Multiple discrepancy theory. Social Indicators Research, 16, 347–413.

Mickel, A. E., & Barron, L. A. (2008). Getting “More Bang for the Buck”: Symbolic value of monetary rewards in organizations. Journal of Management Inquiry, 17, 329–338.

Milgram, S. (1974). Obedience to authority: An experimental view. New York: Harper and Row.

Milkovich, G. T., Newman, J. M., & Gerhart, B. (2014). Compensation (11th ed.). Boston, MA: Irwin/McGraw-Hill.

Mitchell, T. R., & Mickel, A. E. (1999). The meaning of money: An individual difference perspective. Academy of Management Review, 24, 568–578.

Newman, J. M., Gerhart, B., & Milkovich, G. T. (2017). Compensation (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Nickerson, J. A., & Zenger, T. R. (2008). Envy, comparison costs, and economic theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 29(13), 1429–1449.

Nkundabanyanga, S. K., Omagor, C., Mpamizo, B., & Ntayi, J. M. (2011). The love of money, pressure to perform and unethical marketing behavior in the cosmetic industry in Uganda. International Journal of Marketing Studies, 3(4), 40–49.

Özbek, M. F., Yoldash, M. A., & Tang, T. L. P. (2015). Theory of justice, OCB, and individualism: Kyrgyz citizens. Journal of Business Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2553-0.

Pascual-Ezama, D., Fosgaard, T. R., Cardenas, J. C., Kujal, P., Veszteg, R., Gil-Gomez de Liano, B., & Branas-Garza, P. (2015). Context-dependent cheating: Experimental evidence from 16 countries. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 116, 379–386.

Pfeffer, J. (1998, May/June). Six dangerous myths about pay. Harvard Business Review, 108–119.

Piff, P. K., Stancato, D. M., Cote, S., & Mendoza-Denton, R. (2012). Higher social class predicts increased unethical behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109, 4086–4091.

Pinto, J., Leana, C. R., & Pil, F. K. (2008). Corrupt organizations or organizations of corrupt individuals? Two types of organization-level corruption. Academy of Management Review, 33, 685–709.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903.

Prahalad, C. K., & Hammond, A. (2002). Serving the world’s poor profitably. Harvard Business Review, 80, 48–57.

Report to the Nations (2014). Retrieved October 25, 2015 from http://www.acfe.com/rttn-summary.aspx.

Richman, W. L., Kiesler, S., Weisband, S., & Drasgow, F. (1999). A meta-analytic study of social desirability distortion in computer-administered questionnaires, traditional questionnaires, and interviews. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 754–775.

Rijekeghem, C. V., & Weder, B. (1997). Corruption and the rate of temptation: Do low wages in the civil service cause corruption? International Monetary Fund Working Paper, 97/73.

Robinson, S. L., & Bennett, R. J. (1995). A typology of deviant workplace behaviors: A multidimensional scaling study. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 555–572.

Rousseau, D. M., & Fried, Y. (2001). Location, location, location: Contextualizing organizational research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22, 1–13.

Rynes, S. L., & Gerhart, B. (2000). Compensation in organizations: Current research and practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Sardžoska, E., & Tang, T. L. P. (2009). Testing a model of behavioral intentions in the Republic of Macedonia: Differences between the private and the public sectors. Journal of Business Ethics, 87, 495–517.

Sardžoska, E. G., & Tang, T. L. P. (2012). Work-related behavioral intentions in Macedonia: Coping strategies, work environment, love of money, job satisfaction, and demographic variables. Journal of Business Ethics, 108(3), 373–391.

Sardžoska, E. G., & Tang, T. L. P. (2015). Monetary intelligence: Money attitudes—unethical intentions, intrinsic and extrinsic job satisfaction, and coping strategies across public and private sectors in Macedonia. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(1), 93–115.

Scandura, T. A. (2016). Essentials of organizational behavior: An evidence-based approach. Los Angeles: Sage.

Scherbaum, C. A., & Ferreter, J. M. (2009). Estimating statistical power and required sample sizes for organizational research using multilevel modeling. Organizational Research Methods, 12, 347–367.

Schoorman, F. D., & Mayer, R. C. (2008). The value of common perspectives in self-reported appraisals: You get what you ask for. Organizational Research Methods, 11, 148–159.

Simons, T. (2002). Behavioral integrity: The perceived alignment between managers’ words and deeds as a research focus. Organization Science, 13, 18–35.

Simons, T., & Roberson, Q. (2003). Why managers should care about fairness: The effects of aggregate justice perceptions on organizational outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 432–443.

Skarlicki, D. P., & Folger, R. (1997). Retaliation in the workplace: The roles of distributive, procedural, and interactional justice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 434–443.

Skinner, B. F. (1972). Beyond freedom and dignity. New York: Bantam Books.

Smith, A. (1937). An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. New York: Modern Library. (Original work published 1776).

Sorensen, J. B. (2002). The strength of corporate culture and the reliability of firm performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47, 70–91.

Spector, P. E. (2006). Method variance in organizational research: Truth or urban legend? Organizational Research Methods, 9, 221–232.

Spector, P. E., & Fox, S. (2010). Counterproductive work behavior and organizational citizenship behavior: Are they opposite forms of active behavior? Applied Psychology: An International Review, 59(1), 21–39.

Srivastava, A., Locke, E. A., & Bartol, K. M. (2001). Money and subjective well-being: It’s not the money, it’s the motives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 959–971.

Staw, B. M., Bell, N. E., & Clausen, J. A. (1986). The dispositional approach to job attitudes: A lifetime longitudinal test. Administrative Science Quarterly, 31, 56–77.

Tang, T. L. P. (1992). The meaning of money revisited. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 197–202.

Tang, T. L. P. (1993). The meaning of money: Extension and exploration of the money ethic scale in a sample of university students in Taiwan. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 14, 93–99.

Tang, T. L. P. (1996). Pay differentials as a function of rater’s sex, money ethic, and job incumbent’s sex: A test of the Matthew Effect. Journal of Economic Psychology, 17, 127–144.

Tang, T. L. P. (2010). Money, the meaning of money, management, spirituality, and religion. Journal of Management, Spirituality and Religion, 7, 173–189.

Tang, T. L. P. (2014). Theory of monetary intelligence: Money attitudes—religious values, making money, making ethical decisions, and making the grade. Journal of Business Ethics. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2411-5.

Tang, T. L. P., & Baumeister, R. F. (1984). Effects of personal values, perceived surveillance, and task labels on task preference: The ideology of turning play into work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69, 99–105.

Tang, T. L. P., & Chen, Y. J. (2008). Intelligence vs. wisdom: The love of money, Machiavellianism, and unethical behavior across college major and gender. Journal of Business Ethics, 82, 1–26.

Tang, T. L. P., Chen, Y. J., & Sutarso, T. (2008a). Bad apples in bad (business) barrels: The love of money, Machiavellianism, risk tolerance, and unethical behavior. Management Decision, 46(2), 243–263.

Tang, T. L. P., & Chiu, R. K. (2003). Income, Money Ethic, pay satisfaction, commitment, and unethical behavior: Is the love of money the root of evil for Hong Kong managers? Journal of Business Ethics, 46, 13–30.

Tang, T. L. P., Kim, J. K., & Tang, D. S. H. (2000). Does attitude toward money moderate the relationship between intrinsic job satisfaction and voluntary turnover? Human Relations, 53, 213–245.

Tang, T. L. P., & Liu, H. (2012). Love of money and unethical behavior intention: Does an authentic supervisor’s personal integrity and character (ASPIRE) make a difference? Journal of Business Ethics, 107(3), 295–312.

Tang, T. L. P., Luna-Arocas, R., Quintanilla Pardo, I., & Tang, T. L. N. (2014). Materialism and the bright and dark sides of the financial dream in Spain: The positive role of money attitudes—The Matthew Effect. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 63(3), 480–508.