Abstract

Purpose

MRI-based screening in women with a ≥ 25% lifetime risk of breast cancer , but no identifiable genetic mutations may be associated with false positives. This study examined the psychological impact of abnormal screens and biopsies in non-mutation carriers participating in high-risk screening with no personal history of breast cancer.

Methods

Non-mutation carriers participating in the High-Risk Ontario Breast Screening Program at two sites were mailed demographic surveys, psychological scales, and chart review consent. Scales included the Consequences of Screening in Breast Cancer questionnaire, Lerman Breast Cancer Worry Scale, and Worry Interference Scale. Missing data were managed with multiple imputation. Multivariable regression was used to assess whether abnormal screens or biopsies were associated with adverse psychological effects.

Results

After contacting 465 participants, 169 non-mutation carriers were included. Median age was 46 years (range 30–65). Over a median 3 years of screening, 63.9% of women experienced at least one abnormal screen, and 24.9% underwent biopsies. Statements relating to cancer worry/anxiety scored highest, with 19.5% indicating they worried “a lot”. Higher scores among anxiety-related statements were strongly associated with higher dejection scores. Overall, coping and daily functioning were preserved. Women indicated some positive reactions to screening, including improved existential values and reassurance they do not have breast cancer. Abnormal screens and biopsies were not significantly associated with any psychological scale, even after adjustment for patient characteristics.

Conclusion

Non-mutation carriers undergoing MRI-based screening had considerable baseline anxiety and cancer worry, although daily functioning was not impaired. Abnormal screens and biopsies did not appear to have adverse psychological effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)-based screening protocols have been established in several countries in an attempt to improve the detection of breast cancer among women at high risk for the disease [1,2,3,4]. While initial studies focused on women with BRCA mutations, who can have up to an 85% lifetime risk of breast cancer [1, 5, 6], MRI-based screening has been expanded to include other high-risk populations [3]. These include women with strong family histories of breast cancer but no identifiable genetic mutations, and recipients of chest wall radiation.

The High-Risk Ontario Breast Screening Program (OBSP) has offered annual MRI and mammography to high-risk women since 2011, providing services at 32 sites across the province [7]. This strategy has proven to be highly sensitive, but has lower specificity compared to mammography alone, particularly among non-mutation carriers who comprise the majority of participants in the program [8]. False-positive breast cancer screens have been shown to cause psychological distress and impact attendance at future screening appointments [9,10,11,12]. Distress during the evaluation of an abnormal screen has also been acutely associated with invasive procedures, such as core-needle biopsy, which may take up to a month to normalize [13,14,15]. Previous work has shown BRCA carriers participating in an MRI-based screening program had substantial baseline anxiety that increased in response to an abnormal screen, but returned to baseline by 6 months [16]. However, there is a paucity of literature examining the psychological consequences of MRI-based screening in high-risk non-mutation carriers.

With the lower specificity of MRI in this group, they may be at particular risk for false-positives and adverse outcomes. Further, these women are at lower lifetime risk of breast cancer than mutation carriers and may not only respond differentially to abnormal screens, but may not have comparable baseline anxiety. With further extensions of MRI-based screening eligibility a possibility [17, 18], it is critical to understand the implications of such protocols among women without high-risk mutations [19].

Our aim was to study anxiety, functioning, and the psychological impact of both abnormal screens and biopsies in a sample of non-mutation carriers enrolled in the High-Risk OBSP.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional, survey-based study with supplemental chart review performed at two academic hospitals in Toronto, Canada. The Research Ethics Boards at St. Michael’s Hospital (#15–168) and Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center (#397–2016) reviewed and approved this study. This study was completed as part of a comprehensive assessment of MRI-based screening in high-risk non-mutation carriers.

Participants

Study participants were enrolled in the High-Risk OBSP. Eligibility criteria for the program are presented in Supplementary Table 4. Inclusion criteria for this study included: (1) English-speaking, (2) had undergone at least one round of MRI and mammographic screening in the program, (3) no personal history of breast carcinoma prior to enrollment, and (4) no history of a genetic mutation, or did not meet criteria for genetic testing after assessment by a genetic counselor.

Data sources

We identified High-Risk OBSP participants at two tertiary care centers in Toronto, Ontario. In June 2015, all 165 individuals enrolled in the High-Risk OBSP at St. Michael’s Hospital were sent invitations to complete demographic surveys and obtain consent for chart review. In March 2017, the study was broadened to include Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre (SHSC). The first 150 women enrolled at SHSC in 2011 and the first 150 women enrolled in 2017 were sent surveys and asked for chart review consent. In each case, three monthly requests for questionnaire completion and consent were mailed to potential participants.

The surveys consisted of questions regarding demographic data, socioeconomic status, genetic counseling use, detailed family histories, and psychological scales. Chart review was undertaken by trained chart abstractors at the two study sites for clinicopathologic data from participant enrollment to December, 2017. We defined an abnormal screen as any investigation or procedure that was ordered as a result of an abnormal finding on either screening MRI or mammogram. Screening in the program was performed at accredited sites and met standards set by the Canadian Association of Radiologists [8]. They were reported according to the 5th edition of the American College of Radiology Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) [20, 21].

Psychological scales

To investigate the psychological outcomes associated with high-risk screening, three scales were administered. The Consequences of Screening in Breast Cancer (COS-BC) questionnaire is a validated, two-part tool that was specifically designed to assess the psychological impact of false-positive breast cancer screens [22,23,24]. The COS-BC was derived from the Psychological Consequences Questionnaire, which did not include women who had experienced false-positives in its derivation [25, 26]. Part 1 of the questionnaire contains 30 statements with possible scores ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 3 (A lot). The 30 statements correspond to seven dimensions: anxiety, behavioral, dejection, sleep, breast examination, sexuality, and other. Part 2 of the COS-BC assesses perceived changes as a direct response to breast cancer screening. Items can be scored both negatively (e.g., I feel less calm after screening) and positively (e.g., I feel more calm after screening) on a 5-point scale from − 2 to + 2. Statements in Part 2 correspond to four dimensions: existential values, impact on relationships, feelings of relaxation or calm, and belief/anxiety that one has breast cancer.

The Lerman Breast Cancer Worry Scale (LBCWS) is a four-component questionnaire designed to assess anxiety and worry in response to abnormal breast cancer screening [27]. We excluded one component of the scale as it related specifically to mammography and did not include MRI. Statements are scored on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Almost all of the time/A lot).

The final scale administered was the Worry Interference Scale (WIS), a seven-component questionnaire focused on impaired daily functioning in women with a family history of breast cancer [28]. The scale was designed through a combination of interviews with women attending a hereditary breast and ovarian cancer program in the United States, and literature review. The WIS assesses functioning related to sleep, work, relationships, concentration, the ability to have fun, perceived sexual attraction, and family needs. The scale is scored in an identical fashion to the LBCWS.

Statistical analysis

Patient characteristics for the cohort were tabulated. Individual psychological scale scores were presented as boxplots with both the median and mean scores shown. Missing data were managed using multiple imputation [29]. Twenty multiply imputed datasets were created under a fully conditional specification model including all dependent and independent variables. Trace plots of mean and standard deviations were examined in each imputation model. The proportions of missing data in the original dataset are shown in Supplementary Table 5. When patient characteristics and survey results were presented in figures or tables, the first imputation model was used.

Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated in each imputed dataset and combined using Fisher’s z-transformation. Associations between patient characteristics and psychological scales were assessed. Univariate analyses were performed by regressing the total score of each scale against patient characteristics. Parameter estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were determined in each imputation model and combined using Rubin’s Rules [29]. Age was considered a continuous variable, and the remaining characteristics were categorical. Total score for the COS-BS Part 2 was defined as the absolute sum of the individual scores, which is consistent with how the scale was derived [24].

We planned a priori to explore associations between scale scores and abnormal screen status (ever experienced an abnormal screen versus not), one abnormal screen versus two or more, no abnormal screen versus having undergone a biopsy, and finally, comparing abnormal screens with a biopsy and those without. These analyses were performed in a multivariable linear regression model including age, education, and race as covariates. The analysis for this paper was generated using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and RStudio (RStudio Inc., Boston, MA, USA). All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient cohort and characteristics

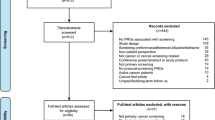

Between the two study sites, 465 individuals were identified and 441 had available contact information (Fig. 1). Of these, 225 surveys were returned (response rate 51%) with 169 high-risk non-mutation carriers included after application of the exclusion criteria. The most common reason for exclusion was having a known high-risk genetic mutation.

The median patient age was 46 years (range 30–65 years) at the time of survey completion. Most women were married (131/169; 77.5%), had children (114/169; 67.4%), were employed (148/169; 87.6%), white (136/169; 80.5%), had a household income of at least $75,000 CAD (136/169; 80.5%), and had completed university or college education (95/169; 56.2%). The median International Breast Cancer Intervention Study (IBIS) lifetime risk of breast cancer score was 28.0% (range 24.5–89.0%). The majority of women had a single first degree relative with breast cancer (122/169; 72.2%), although a small number had 3 or more (6/169; 3.6%).

Over a median 3 years of screening per individual, 475 screening MRIs (with associated mammograms) were completed. Most women experienced at least one abnormal screen (108/169; 63.9%). There were a total of 162 abnormal screens, in which the triggering investigation was MRI alone in 110 cases (65.1%), mammography alone in 31 cases (18.3%), and combined modalities in the remaining cases (21/169; 12.4%). Forty-two women (24.9%) underwent at least one biopsy for screen-detected lesions, with 11 undergoing two biopsies (6.5%) and one woman undergoing 3 biopsies. Of the 55 biopsies performed, the triggering investigation was MRI alone in 41 cases (74.5%), mammography alone in 3 cases (5.5%), and combined modalities in 11 cases (20.0%). Eight surgeries were performed among 7 women – one in situ carcinoma and 3 invasive carcinomas were found on final pathology.

Consequences of breast cancer screening questionnaire

The COS-BC Part 1 questionnaire assesses the psychological impact of a false-positive breast cancer screen with statements representing seven unique dimensions [22,23,24]. Out of a possible total score of 90, the mean score was 21.7 (SD 15.6) (Supplementary Table 6). Of the five highest scored statements, three were from the anxiety dimension (Fig. 2). Thirty-three (19.5%) women reported they were worried “a lot” (Supplementary Table 6). Otherwise, there was no clear pattern among which dimensions patients more strongly associated. Statements of subjective experiences (i.e., “I have felt scared”, “I have been uneasy”) tended to score more highly than statements relating to daily functioning or coping (i.e., “I have had difficulty doing everyday things”, “I have taken many sick days”). Higher scores in the anxiety dimension were strongly associated with higher scores in the dejection dimension (correlation coefficient 0.91, p < 0.0001; Supplementary Table 7). Individuals with higher anxiety scores also demonstrated higher scores related to adverse behaviors, such as difficulty at work or difficulty concentrating (correlation coefficient 0.77, p < 0.0001; Supplementary Table 7).

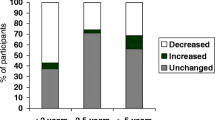

Part 2 of the COS-BC examines perceived changes from baseline in response to breast cancer screening, corresponding to four dimensions [22,23,24]. None of the statements had a mean value indicating worse functioning after breast cancer screening (Fig. 3). The existential values dimension showed the greatest positive change after screening, with the statement “My thoughts about the broader aspects of life are…” showing the largest improvement. Dimensions relating to relationships with others and feelings of relaxation showed little change from baseline. Women indicated their belief that they do not have breast cancer is improved after breast cancer screening, but their anxiety about breast cancer remained essentially unchanged.

Lerman breast cancer worry scale

The LBCWS assesses anxiety and worry in response to abnormal breast cancer screening [27]. Out of a possible total of 12, the mean score for the cohort was 3.6 (SD 1.8) (Supplementary Table 6). Patients scored worry about eventually developing breast cancer more highly, with 14 patients (8.3%) indicating they worried “almost all the time”. However, this worry affected their mood to a lesser degree, and had almost no impact on their ability to perform their daily activities (Fig. 4).

Worry interference scale

The WIS focuses on impaired daily functioning in women with a family history of breast cancer [28]. The mean score for the cohort was 4.2/28 (SD 5.2), indicating overall low impact on daily functioning (Fig. 4, Supplementary Table 6). The area most impacted was patients’ ability to sleep, although only 4 women (2.4%) indicated this was affected “a lot” (see Table 1).

Univariate and multivariable associations with patient characteristics, abnormal screens, and biopsies

Univariate linear regression was performed for the total scores of the psychological scales against patient characteristics. There were no significant associations between any scale and patient age, marital status, having children, employment, income, or number of first degree relatives with breast cancer (Table 2). For the COS-BC Part 1, patients identifying as Black had significantly higher mean scores (15.4 points, 95% CI 0.2–30.5) compared to white patients, as did those with some college or university education (15.2 points, 95% CI 1.7–28.6) or completed college/university education (12.1 points, 95% CI 0.6–23.7), compared to high school education. Similar findings were seen for the WIS—higher scores were seen among patients identifying as Asian (3.0 points, 95% CI 0.4–5.6) or Black (7.7 points, 95% CI 2.7–12.6), and those with college or university education (4.5 points, 95% CI 0.6–8.3).

Our a priori planned analysis of total scores against abnormal screen and biopsy status are presented in Table 3. There were no significant associations with any scale and having experienced an abnormal screen, or having undergone a biopsy. These findings were unchanged after multivariable adjustment for age, education level, and race.

Discussion

This cross-sectional survey study of 169 non-mutation carriers undergoing MRI-based screening in the High-Risk OBSP demonstrated that while baseline worrying and anxiety were present, they did not appear to impact daily functioning. Further, women endorsed some positive psychological reactions to undergoing screening and did not appear to have significantly worse psychological outcomes after an abnormal screen or undergoing a biopsy.

Psychological outcomes of women participating in high-risk breast cancer screening have been studied for nearly 20 years [30]. The Dutch Magnetic Resonance Imaging Screening (MRISC) study began in 1999, with one-third of participants at comparable risk of breast cancer to our population of interest (15–30% lifetime risk of breast cancer with no known BRCA mutations) [30]. Short-term outcomes in this study indicated participants did not experience increased distress due to screening, and actually had improved quality of life measures compared to a reference Dutch population [31]. Similar to our sample, women in the MRISC study were highly educated and the authors hypothesized voluntary participation in additional cancer screening may self-select for women with higher quality of life at baseline [31, 32]. Also similar to the Dutch cohort, our results demonstrated that daily functioning was preserved. Statements relating to the impact of worry on patients daily life or functioning scored low across all scales. Contrary to the MRISC study, which did not find strong evidence of baseline anxiety in high-risk women [33], statements relating to the presence of anxiety and worry were scored the highest on the COS-BC (I) and LBCWS in our study. This difference may be due to our using scales specifically designed to assess psychological outcomes in breast cancer screening patients. In a larger prospective cohort of young women with a family history of breast cancer (including non-mutation carriers) undergoing mammography screening in the United Kingdom, patients were found to have moderate levels of baseline worry when assessed with a breast cancer-specific scale [34, 35].

Contrary to our hypothesis, non-mutation carriers with a history of being called back due to an abnormal screen or undergoing a biopsy did not have worse psychological outcomes. This finding persisted even after adjustment for patient characteristics and assessing those with multiple abnormal screens. Among the general population undergoing breast cancer screening, false-positives have been clearly associated with adverse psychological outcomes, which may be detectable for up to 3 years [9,10,11,12]. An analysis of the United Kingdom high-risk cohort mentioned earlier showed psychological measures worsened in response to a false-positive mammogram, but returned to baseline by 6 months [36]. The authors raised the possibility that high-risk women may enter screening with the expectation that abnormalities will be discovered, psychologically buffering them from the long-term effects of false-positives [36]. Similar findings have been described among BRCA mutation carriers undergoing MRI-based screening [16, 37]. Portnoy et al. measured cancer worry in BRCA mutation carriers using the LBCWS after a false-positive MRI [37]. While a transient increase was seen 3 months after MRI, cancer worry returned to baseline by 1 year. O’Neill et al. similarly did not detect a clear signal toward adverse psychological outcomes after false-positive MRI in a high-risk population, including both mutation carriers and non-mutation carriers [38]. It is possible affected patients in our cohort may have had temporary increases in anxiety or worry in response to abnormal screens and biopsies, but these were not detected due to the cross-sectional nature of the study design.

Further supporting our finding that abnormal screens and biopsies did not result in sustained adverse psychological outcomes, patients endorsed some positive reactions to screening events. In Part 2 of the COS-BC, non-mutation carriers indicated their broader thoughts, value, and enjoyment of life were improved after undergoing screening. They also experienced reassurance they did not have breast cancer. This is consistent with some existing literature. In a comprehensive qualitative analysis of 9 non-mutation carriers (20 interviews) with strong family histories of breast cancer, Schroeder et al. reported women felt an “emotional release” after normal screening results [39]. While this study did not explicitly mention MRI-based screening, non-mutation carriers felt substantial reassurance while being followed at a specialized high-risk breast cancer clinic, and this overshadowed the transient anxiety associated with screening tests [39]. Positive associations with undergoing high-risk screening have also been described among BRCA carriers—faith in intensive surveillance and health care professionals are among the reasons given for declining prophylactic mastectomy [32].

A strength of this study was our focus on non-mutation carriers undergoing MRI-based screening. While other studies have reported on mixed populations in high-risk screening programs [30, 38], non-mutation carriers now represents more than 70% of participants in the High-Risk OBSP [8], and understanding the impact of MRI-based screening for these women is critical. We used validated scales designed to assess psychological outcomes after breast cancer screening rather than more general scales that may underestimate cancer worry in this otherwise high-functioning population [33]. Finally, our strong analytic approach including multiple imputation allowed us to retain power while addressing missing survey data.

This study does have limitations. The cross-sectional nature of our study precluded us from assessing whether transient psychological disturbances occur in response to abnormal screens or biopsies. A prospective, longitudinal design with repeated measures, as has been performed among BRCA carriers [16], would have provided more granular data. However, our results still allowed us to exclude long-term psychological harm, and this was internally consistent with how women scored their perceived changes in response to screening in the COS-BC Part 2 questionnaire. Further, we did not collect measures such as the time between last screen/abnormal screen and survey completion. We studied a sample of non-mutation carriers in the High-Risk OBSP at only two sites in the program. It is possible our results are not generalizable to the remaining non-mutation carriers, or to other high-risk programs. However, the two study sites are tertiary academic cancer centers in a very large urban area. If selection bias is present, we would expect these particular sites to attract higher risk women. Thus, the finding that abnormal screens and biopsies did not increase psychological distress in this sample is particularly reassuring.

The lower specificity of MRI compared to mammography screening in high-risk women is a particular concern for non-mutation carriers, who have a lower pre-test probability for breast cancer than mutation carriers [8]. Our results add to existing evidence that the surveillance benefits of MRI-based screening are not offset by adverse psychological outcomes [40]. Rather, an area of more productive intervention may be the considerable baseline anxiety and cancer-directed worry we observed. While this did not appear to impact daily functioning, anxiety was highly correlated with feelings of dejection and behavioral consequences. Screening high-risk women for baseline anxiety could be used to identify those at risk of coping difficulties and would be appropriate for intervention [34]. Peer support groups, self-help coping interventions, educational retreats, and group therapy have all been explored for mutation carriers, with mixed results [41,42,43,44,45,46]. It is unclear how these interventions would translate to non-mutation carriers. Further research is needed to clarify to what extent cancer worry experienced by non-mutation carriers is detrimental, how at-risk women can be identified, and what interventions are appropriate.

Data availability

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not explicitly agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data are not available.

Code availability

Available upon request.

References

Warner E, Messersmith H, Causer P et al (2008) Systematic review: using magnetic resonance imaging to screen women at high risk for breast cancer. Ann Intern Med 148:671–679. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-148-9-200805060-00007

Granader EJ, Dwamena B, Carlos RC (2008) MRI and mammography surveillance of women at increased risk for breast cancer: recommendations using an evidence-based approach. Acad Radiol 15:1590–1595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acra.2008.06.006

Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W et al (2007) American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin 57:75–89. https://doi.org/10.3322/canjclin.57.2.75

(2017) Breast Cancer Screening for Women at High Risk. In: Cancer Care Ontario. https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/guidelines-advice/cancer-continuum/screening/breast-cancer-high-risk-women. Accessed 20 Jan 2020

Kuhl CK, Schmutzler RK, Leutner CC et al (2000) Breast MR imaging screening in 192 women proved or suspected to be carriers of a breast cancer susceptibility gene: preliminary results. Radiology 215:267–279. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiology.215.1.r00ap01267

Warner E, Plewes DB, Shumak RS et al (2001) Comparison of breast magnetic resonance imaging, mammography, and ultrasound for surveillance of women at high risk for hereditary breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 19:3524–3531. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2001.19.15.3524

(2017) High Risk Ontario Breast Screening Program FAQs for Healthcare Providers. In: Cancer Care Ontario. https://www.cancercareontario.ca/en/guidelines-advice/cancer-continuum/screening/breast-cancer-high-risk-women/faqs-for-healthcare-providers. Accessed 10 Jun 2020

Chiarelli AM, Blackmore KM, Muradali D et al (2019) Performance measures of magnetic resonance imaging plus mammography in the High Risk Ontario Breast Screening Program. J Natl Cancer Inst. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djz079

Brett J, Bankhead C, Henderson B et al (2005) The psychological impact of mammographic screening. A Syst Rev Psycho-Oncol 14:917–938. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.904

Brewer NT, Salz T, Lillie SE (2007) Systematic review: the long-term effects of false-positive mammograms. Ann Intern Med 146:502–510. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-146-7-200704030-00006

Bond M, Pavey T, Welch K et al (2013) Systematic review of the psychological consequences of false-positive screening mammograms. Health Technol Assess 17(1–170):v–vi. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta17130

Salz T, Richman AR, Brewer NT (2010) Meta-analyses of the effect of false-positive mammograms on generic and specific psychosocial outcomes. Psychooncology 19:1026–1034. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1676

Maxwell JR, Bugbee ME, Wellisch D et al (2000) Imaging-guided core needle biopsy of the breast: study of psychological outcomes. Breast J 6:53–61. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1524-4741.2000.98079.x

Miller SJ, Sohl SJ, Schnur JB et al (2014) Pre-biopsy psychological factors predict patient biopsy experience. Int J Behav Med 21:144–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-012-9274-x

Steffens RF, Wright HR, Hester MY, Andrykowski MA (2011) Clinical, demographic, and situational factors linked to distress associated with benign breast biopsy. J Psychosoc Oncol 29:35–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347332.2011.534024

Spiegel TN, Esplen MJ, Hill KA et al (2011) Psychological impact of recall on women with BRCA mutations undergoing MRI surveillance. Breast 20:424–430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2011.04.004

Bakker MF, de Lange SV, Pijnappel RM et al (2019) Supplemental MRI screening for women with extremely dense breast tissue. N Engl J Med 381:2091–2102. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1903986

Longo DL (2019) Detecting breast cancer in women with dense breasts. N Engl J Med 381:2169–2170. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe1912943

Korenstein D (2018) Wise guidance and its challenges: the new Canadian recommendations on breast cancer screening. CMAJ 190:E1432–E1433. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.181538

Spak DA, Plaxco JS, Santiago L et al (2017) BI-RADS® fifth edition: a summary of changes. Diagn Interv Imaging 98:179–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diii.2017.01.001

Rao AA, Feneis J, Lalonde C, Ojeda-Fournier H (2016) A pictorial review of changes in the BI-RADS fifth edition. Radiographics 36:623–639. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2016150178

Brodersen J, Thorsen H (2008) Consequences of screening in breast cancer (COS-BC): development of a questionnaire. Scand J Prim Health Care 26:251–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/02813430802542508

Brodersen J, Thorsen H, Kreiner S (2007) Validation of a condition-specific measure for women having an abnormal screening mammography. Value Health 10:294–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00184.x

Brodersen J, Siersma VD (2013) Long-term psychosocial consequences of false-positive screening mammography. Ann Fam Med 11:106–115. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1466

Brodersen J, Thorsen H, Cockburn J (2004) The adequacy of measurement of short and long-term consequences of false-positive screening mammography. J Med Screen 11:39–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/096914130301100109

Cockburn J, De Luise T, Hurley S, Clover K (1992) Development and validation of the PCQ: a questionnaire to measure the psychological consequences of screening mammography. Soc Sci Med 34:1129–1134. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(92)90286-y

Lerman C, Trock B, Rimer BK et al (1991) Psychological side effects of breast cancer screening. Health Psychol 10:259

Trask PC, Paterson AG, Wang C et al (2001) Cancer-specific worry interference in women attending a breast and ovarian cancer risk evaluation program: impact on emotional distress and health functioning. Psychooncology 10:349–360. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.510

Rubin DB (2004) Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Wiley

van Dooren S, Rijnsburger AJ, Seynaeve C et al (2003) Psychological distress and breast self-examination frequency in women at increased risk for hereditary or familial breast cancer. Community Genet 6:235–241. https://doi.org/10.1159/000079385

Rijnsburger AJ, Essink-Bot ML, van Dooren S et al (2004) Impact of screening for breast cancer in high-risk women on health-related quality of life. Br J Cancer 91:69–76. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6601912

Warner E (2004) Intensive radiologic surveillance: a focus on the psychological issues. Ann Oncol 15(Suppl 1):I43–I47. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdh657

den Heijer M, Seynaeve C, Vanheusden K et al (2013) Long-term psychological distress in women at risk for hereditary breast cancer adhering to regular surveillance: a risk profile. Psychooncology 22:598–604. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3039

Brain K, Henderson BJ, Tyndel S et al (2008) Predictors of breast cancer-related distress following mammography screening in younger women on a family history breast screening programme. Psychooncology 17:1180–1188

Henderson BJ, Tyndel S, Brain K et al (2008) Factors associated with breast cancer-specific distress in younger women participating in a family history mammography screening programme. Psychooncology 17:74–82

Tyndel S, Austoker J, Henderson BJ et al (2007) What is the psychological impact of mammographic screening on younger women with a family history of breast cancer? Findings from a prospective cohort study by the PIMMS Management Group. J Clin Oncol 25:3823–3830

Portnoy DB, Loud JT, Han PK et al (2015) Effects of false-positive cancer screenings and cancer worry on risk-reducing surgery among BRCA1/2 carriers. Health Psychol 34:709

O’Neill SM, Rubinstein WS, Sener SF et al (2009) Psychological impact of recall in high-risk breast MRI screening. Breast Cancer Res Treat 115:365

Schroeder D, Duggleby W, Cameron BL (2017) Moving in and out of the what-ifs: the experiences of unaffected women living in families where a breast cancer 1 or 2 genetic mutation was not found. Cancer Nurs 40:386–393. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000438

Brédart A, Kop J-L, Fall M et al (2012) Anxiety and specific distress in women at intermediate and high risk of breast cancer before and after surveillance by magnetic resonance imaging and mammography versus standard mammography. Psychooncology 21:1185–1194

Visser A, Van Laarhoven HW, Woldringh GH et al (2016) Peer support and additional information in group medical consultations (GMCs) for BRCA1/2 mutation carriers: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Oncol 55:178–187

Bennett P, Phelps C, Brain K et al (2007) A randomized controlled trial of a brief self-help coping intervention designed to reduce distress when awaiting genetic risk information. J Psychosom Res 63:59–64

McKinnon W, Naud S, Ashikaga T et al (2007) Results of an intervention for individuals and families with BRCA mutations: a model for providing medical updates and psychosocial support following genetic testing. J Genet Couns 16:433–456

White VM, Young M-A, Farrelly A et al (2014) Randomized controlled trial of a telephone-based peer-support program for women carrying a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation: impact on psychological distress. J Clin Oncol 32:4073–4080

Esplen MJ, Hunter J, Leszcz M et al (2004) A multicenter study of supportive-expressive group therapy for women with BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations. Cancer 101:2327–2340

Prospero L, Seminsky M, Honeyford J et al (2001) Support groups for people carrying a BRCA mutation. CMAJ 165:740–742

Funding

Cancer Care Ontario, Achieving Excellence in Cancer Care Project Award (2015).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The Research Ethics Boards at St. Michael’s Hospital (#15-168) and Sunnybrook Health Sciences Center (#397-2016) reviewed and approved this study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Castelo, M., Brown, Z., D’Abbondanza, J.A. et al. Psychological consequences of MRI-based screening among women with strong family histories of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 189, 497–508 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-021-06300-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-021-06300-w